Abstract

Picture Exchange Communication Systems (PECS) is a form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) frequently used by individuals with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability when speech development is delayed or does not develop (Bondy and Frost 1994 in Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 9, 1–19; Sunberg and Partington 1998). Researchers have previously evaluated variations of PECS as a means for vocalization development (Ganz and Simpson 2004 in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 395–409; Tincani et al. 2006 in Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 41, 177–184). The current study investigated delay to reinforcement and an increase in response effort when utilizing PECS on the development of intelligible word vocalizations with four elementary aged students. Three participants transitioned from primarily requesting using PECS at Phase IIIb to using independent vocalizations (i.e., spoken words). This research provides further evidence for the use of PECS not only as a tool for functional communication, but also as a resource for assisting individuals in the development of vocalizations with slight variations in the parameters of reinforcement including response effort and delay of reinforcement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Speech is the most common and portable form of communication and therefore is the most ideal (Sunberg and Partington 1998). Seventy percent of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and a history of severe language delay develop speech by 8 years; however, a significant number of individuals with ASD fail to develop spoken language (Wodka et al. 2013). The National Longitudinal Study 2 (Newman et al. 2011) found that 31.1% of youth with ASD are described by their parents as having either “a lot of trouble speaking” or as “unable to speak at all.” The impact of language delay goes beyond communication difficulties. Sigafoos (2000) found that communication ability was inversely related to the severity of problem behavior displayed by individuals with developmental disabilities. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) provides a range of alternatives to spoken communication, including sign language, picture exchange, and speech generating devices. These strategies are often used for individuals who do not typically develop speech, including children with ASD (Mirenda 2003). AAC addresses communication, but might also benefit individuals by assisting them with social interaction, the elimination of problem behavior, and improvements in academic skills (Ganz et al. 2012).

Picture Exchange Communication Systems (PECS) is a low-tech, aided system for communication taught to individuals with ASD and other developmental disabilities as a form of functional communication when speech does not develop typically (Bondy and Frost 1994). Based on the results of the National Longitudinal Transition Study (NLTS-2; Newman et al. 2011) parent survey, 33.6% of youth with ASD and difficulty speaking utilize a communication board. PECS is similar to a communication board in that it incorporates pictures and is used for communication that does not incorporate technology.

While the use of AAC strategies has been well established in research and practice (Ganz et al. 2012), some families of children with ASD may initially hesitate to implement systems such as PECS and American Sign Language (ASL) fearing that these or other AAC strategies will hinder the eventual development of speech (Blischak et al. 2003; Schlosser 2003). In a review of the literature, Blischak et al. (2003) found that implementing AAC as a mode of communication for children with ASD or pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) did not result in a decline in speech production; rather, most of the studies reviewed reported an increase in vocalizations for most participants. These authors suggested that the increased use of vocalizations observed to accompany the use of AAC could be linked to response effort. Specifically, because use of PECS requires more effort, preference of mand topography may change from PECS to vocalizations, as PECS requires more effort. Given the wide use of PECS and the concerns related to the implementation of PECS, one area of investigation has been looking at vocal development when individuals utilize PECS.

Ganz and Simpson (2004) evaluated the impact of PECS training on intelligible word vocalizations and word approximation vocalizations exhibited by three individuals receiving services related to ASD. The researchers did not alter the PECS protocol outlined by Bondy and Frost (1994), but measured PECS proficiency, intelligible word vocalizations, and word approximation vocalizations. Each participant produced no more than 10 intelligible word vocalizations prior to the onset of PECS training. In regards to PECS proficiency, each of the participants mastered the first four phases of PECS. The participants did not produce intelligible word vocalizations during Phases I and II. A therapeutic trend for intelligible word vocalizations occurred during Phase III for two participants and during Phase IV for the other participant. All of the participants produced at least 2.5 intelligible word vocalizations during the last three trials of Phase IV. These results indicated that PECS can be used as a strategy for not only teaching functional communication, but also as a mechanism for developing vocalizations.

Tincani (2004) reported similar findings demonstrating the development of intelligible word vocalizations with the use of PECS. The procedures differed from the previous study in that a delay in the delivery of the preferred item was implemented for one participant during Phase IIIb of PECS. After the participant delivered the picture to the communication partner, the communication partner waited no more than 4 s. If an intelligible word vocalization occurred during the 4 s, the participant received the requested item immediately. If the participant did not produce an intelligible word vocalization during the delay, the participant received access to the item after the delay. The alteration was only included for three of the sessions in the study, but presented an abrupt change in level for intelligible word vocalizations compared to previous sessions of PECS. The authors recommended additional evaluation on the use of delays in conjunction with PECS.

Tincani et al. (2006) replicated and extended the findings described in Tincani (2004) through a series of studies. During the first study, PECS was implemented with two participants while incorporating a delay during Phase IV. The delay procedures were identical to Tincani (2004), but the delay was described as being 3 to 5 s. Intelligible word vocalization and word approximation vocalizations were not reinforced during Phase I through Phase III. One participant reached Phase IV and displayed an increased percentage of word approximation vocalizations. A second study was implemented to verify the functional relation between the delay to reinforcement and the increase in vocalizations. For the second study, a third participant received training on Phases I, II, and III. The researchers utilized an ABAB design to compare two sets of procedures. The baseline condition did not involve a delay before delivery, and intervention mirrored the procedures utilized for Phase IV in the original study. The results demonstrated a functional relation between the use of a delay to reinforcement and the increase in word approximation vocalizations. However, the participant did not emit intelligible word vocalizations throughout the second study. These results indicate that a delay to reinforcement during PECS Phase IV may lead to an increase in vocalizations.

Incorporating a delay to reinforcement during AAC-based communication training can lead to individuals engaging in two different modalities of communication, AAC and vocalizations. Practitioners may determine that utilizing multiple modalities is too cumbersome or unnecessary for the individual. After increasing vocalizations, practitioners may consider ways to alter responding completely. This type of intervention has been previously researched with functional communication training (FCT) literature when extinction is not a feasible option. For instance, Buckley and Newchok (2005) altered responding from aggression to picture exchange. The author’s found that when the picture was within arm’s reach the participant altered responding. However, when the response effort was greater, requiring the participant to travel to communicate, the participant reverted back to aggression. These results suggest that increasing the response effort for the less desired mand can result in a change in response allocation.

The aforementioned studies each incorporated concurrent schedules of reinforcement in that two different contingencies were operating independently and simultaneously for two different communicative behaviors (Cooper et al. 2007). Concurrent schedules of reinforcement have been altered previously in an effort to change manding behavior (Bernstein et al. 2009; Bernstein and Sturmey 2008). Altering delay to reinforcement and response effort for two behaviors in a concurrent arrangement may impact response allocation.

PECS provides individuals with a functional form of communication, and alterations to the PECS protocol may increase intelligible word vocalizations (Ganz and Simpson 2004; Tincani 2004; Tincani et al. 2006). A study conducted by Ganz and Simpson (2004) was not explicitly designed to increase vocalizations, but the authors measured vocalizations as a correlate to the main dependent variable (appropriate use of PECS) and observed changes. Tincani et al. (2006) attempted to systematically increase vocalizations with the use of a delay to reinforcement, but the vocalizations were approximations and the delay was only implemented during Phase IV of PECS. Published data on the systematic manipulation of PECS including delay to reinforcement and increased response effort in the early phases to increase intelligible word vocalizations does not exist. Given reports that some parents are hesitant to begin PECS training with their children who have language delays for fear that doing so would further delay vocal development (Schlosser 2003), experimental studies evaluating the impact of AAC strategies on speech production may motivate families to consider options for AAC sooner resulting in early intervention for children (Blischak et al. 2003). The purpose of the current study was to answer the following questions: a) What effect does a delay to reinforcement during PECS exchanging have on the number of target word vocalizations produced to mand for preferred items? b) What effect does increased response effort have on the number of target word vocalizations produced to mand for preferred items?

Method

Participants

Four students between the ages of 5 and 7 years old participated in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participant’s legal guardians included in the study. All students were recruited from the same special education classroom setting designed to serve kindergarten through second grade students with significant developmental delay or ASD. Participants were recruited based on their demonstrated mastery of PECS through Phase II and corresponding Individualized Education Plan objectives focused on increasing communication and communicating their wants and needs. University faculty who attended a PECS workshop through Pyramid Educational Consultants previously trained all of the participants in PECS and supervised other trainers. Prior to the start of PECS training university faculty and graduate students interviewed lead teachers to determine participant preferences or items they would likely request. The lead teachers determined preferred stimuli by asking parents and familiar staff to describe the students preferred food items and leisure activities. All students were administered the Developmental Profile 3 (DP-3; Alpern 2007). The DP-3 is a standardized measure of child development. The assessment requires parents and caregivers to complete interviews or checklists to determine the student’s cognitive functioning as it pertains to perception, concept development, number relations, reasoning, memory, classification, time concepts, and related mental acuity tasks.

Wilburn was a 5-year old, African-American male who had been using PECS for approximately two weeks prior to the start of the study. His special education eligibilities were ASD and speech or language impairment. Wilburn was able to remain in a seat when provided with frequent opportunities to play in a designated play area. Wilburn often engaged in dropping and property destruction. Wilburn inconsistently echoed vocalizations emited by teachers. On the cognitive domain of the DP-3, Wilburn received a standard score of less than 50 (more than 3 standard deviations below the mean). This score was considered to be indicative of cognitive delay, which means that Wilburn’s performance on cognitive tasks was below the expected level of functioning for his age. Wilburn requested for items including Kit Kats, goldfish, and gummies.

Manny was a 5-year old Latino male who had been using PECS for approximately four months prior to the start of the study. His special education eligibilities were significant developmental delay and speech or language impairment. Manny lived at home with both of his parents where Spanish was the primary spoken language. His parents reported that Manny did not speak either language at home. In the classroom he independently made unintelligible sounds and echoed words and phrases modeled by classroom teachers. On the DP-3, Manny also received a standard score of less than 50 (more than 3 standard deviations below the mean). Manny requested for items including grapes, goldfish, gummies, pretzel, Kit Kat, chips and cookies.

Nelson was a 7-year old, African-American male who had been using PECS for approximately four months. His special education eligibilities were significant developmental delay and speech or language impairment. On the DP-3, Nelson scores on the DP-3 were similar to Manny and Wilburn on the cognitive domain indicating a delay in cognitive functioning. Nelson communicated with some sign language as well as by pointing and gesturing. He inconsistently used signs to ask for help, swing, water, and bathroom. Nelson could echo vocalizations with approximations of initial word sounds. Nelson requested for items such as grapes, gummies, goldfish, and Kit Kats.

Arman was a 6-year old male Persian student who had been using PECS for approximately eight months prior to the beginning of the study. He received initial PECS instruction in a university clinic setting supplemented with additional training in his classroom. His parents had a PECS book at home and had also received training on implementation. His special education eligibilities were significant developmental delay and speech or language impairment. On the DP-3, Arman performed two standard deviations below the mean indicating a cognitive delay. Arman lived with both of his parents who spoke English but primarily spoke Farsi in the home. Arman’s parents reported that he did not speak either language at home. Arman requested for items such as cereal, a beaded necklace, water, goldfish, balls, and a book.

Materials and Setting

Materials

Each participant had their own two-ring, 5.08 cm × 10.16 cm PECS binder purchased directly from the PECS-USA.com website. The images used for exchange were 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm laminated, color photographs of each of the preferred items the students were likely to request. New pictures were created as preferences evolved and other choices became available throughout the study. Despite best practice suggesting the continuous availability of the PECS communication book, participants did not have access to the PECS book throughout the day in order to control for history threats.

Setting

The study took place in a self-contained special education classroom at a public elementary school in the Southeastern United States. The classroom was staffed and operated by a university behavior analysis clinic. The classroom was led by doctoral students who were certified teachers. Masters-level graduate students and bachelor-level interns assisted in delivering instruction. Classroom staff (university students) served as primary and secondary data collectors. The physical classroom measured approximately 7.3 m by 5.4 m. Sessions took place at a rectangle-shaped table situated in a partitioned off portion of the room. This setting generally served as an instructional area for small group and individual instruction.

Dependent Variables, Response Definitions, and Measurement

The primary dependent variable was the percentage of trials with independent intelligible word vocalizations which were categorized as “correct” and “incorrect.” An independent intelligible word vocalization was an audible oral response that matched with at least one of the available snack items (e.g. if pretzels and crackers were available, a vocal statement of “pretzels” could be scored as correct but “cookies” or “tah” would be incorrect). For two of the participants, Nelson and Arman, word approximation vocalizations of the snack items were accepted after communication partners and data collectors agreed upon a target vocalization. Data were also collected on the percentage of trials with independent picture exchanges (as opposed to vocal responses). An independent picture exchange required the participant to grab, reach, and release the picture and select the corresponding item when given an array. No latency parameters for independent vocal responses were used for two reasons. First, in the delay trials, the occurrence of the vocal mand model by the teacher would automatically make any subsequent response a prompted vocal (an echoic: i.e. not independent). A vocal mand model occurred when the teacher provided the target vocalization after the picture was exchanged and before providing the target reinforcer. Second, individual trials did not have specific start points. Rather, available reinforcers were visible at the table, and a student could spontaneously initiate a response (picture exchange or vocal) at any point. A session could in theory have an infinite number of mands until the student was satiated with the reinforcer.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Fidelity

For at least 30% of all sessions across conditions a second, independent observer collected participant response data and procedural fidelity data. The data collector was a masters or doctoral student in special education who had previously received specific training and demonstrated 100% reliability in scoring participant and teacher responses.

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated using trial-by-trial IOA (dividing the number of agreed upon trials by the total number of trials and multiplying that number by 100) (Cooper et al. 2007). The mean IOA for Wilburn was 98.81% (range, 91 to 100%). For Manny, the mean was 97.46% (range, 87.14 to 100%). Interobserver agreement for Nelson was 97.82% (range, 82 to 100%). Finally, for Arman the mean IOA was 100%. Procedural fidelity overall was 100%.

Procedures

Sessions lasted between 10 and 30 min and took place during the students’ regular snack time. The teacher sat across from the student with the containers of reinforcers (food or toys) and vocally labeled each item. Then the teacher told the student “If you want something, you can ask.” This direction was part of a classroom routine, but not directly in line with the PECS procedures. The teacher then waited while looking at the student. Another teacher provided prompting to complete the picture exchange if the child reached for the item rather than the picture. Regardless of phase, any vocal mand resulted in immediate access to the corresponding item. If the student manded for a piece of food, the teacher provided a small, bite-size portion. If the student manded for a toy, the teacher provided 30 s of access to the toy, and then retrieved the toy to begin the next trial. The difference between the baseline and reinforcer delay conditions was the teacher’s response to picture exchanges.

Vocalization Screening

Because participants did not all exhibit echoic responding that perfectly matched models, a screening for intelligible vocalizations and vocal approximations was used to help define correct responding. This took place in natural contexts prior to baseline and was repeated periodically if new reinforcers were incorporated into the training. The screening involved a teacher prompting the child to echo the target vocalizations no more than 10 times. The screening took place in the absence of the actual reinforcers and was recorded on an iPhone recording application. After the vocalization occurred the teachers and data collectors agreed on the target vocalization. The target vocalization was also written phonetically for data collectors to refer to during sessions. The target vocalizations for two participants, Manny and Wilburn were the actual word while the vocalizations for Nelson and Arman were approximations of the actual word. The target approximations for Nelson and Arman included at least two beginning phonemes of the requested word. For example, if the individual was requesting a “gummy” an accepted vocalization approximation was “guh” for Arman and “guhbe” for Nelson.

Baseline

Prior to baseline, participants were trained to mastery to PECS Phase IIIb. During baseline, any mand (vocal or picture exchange) resulted in immediate access to reinforcement. A check for correspondence based on the procedures outlined by Bondy and Frost (2001) took place during baseline for all participants. After either mand, the teacher vocally modeled the label for the item and provided the item to the student. The teacher then provided vocal praise for engaging in the mand for the item. For example, the teacher said “cookie, great job asking for the cookie.”

Reinforcer Delay

During the reinforcer delay condition, intelligible word vocalizations or word approximation vocalizations accessed immediate reinforcement identical to the reinforcement provided for correct picture exchanges in the form of the corresponding edible food item or opportunity to play with a toy, as in the baseline condition. Additionally, the student received verbal praise following the delivery and labeling of the reinforcer (“Chip, great job asking for a chip”). A parametric manipulation (Schroeder 1972) was used by gradually increasing the delay to reinforcement until the participant’s responding allocated to a different response. On the first session of intervention, the communication partner waited 1 s after receiving the picture before delivering the reinforcer. If the participant engaged in a vocalization, the communication partner immediately provided the item and verbal praise; thus, students escaped or avoided the delay by vocalizing. If 1 s passed and the participant did not engage in the target vocalization, the communication partner provided the reinforcer and modeled the target vocalization. The delay between the participant delivering the picture and the communication partner delivering the item increased by 1 s each day of intervention until the individual vocalized at least 80% of the session for two sessions. For Arman, the decision was made to terminate the increasing delay since Arman did not increase vocalizations over time.

Response Effort

Once the student vocalized before the model for at least 80% of the trials for at least one session, the response effort to communicate with PECS was increased and then gradually decreased. The increased response effort procedure began by first moving the book 0.91 m away from the participant. This procedure mirrors Phase II of PECS during which individuals are taught to move to their book and communication partner. Once the participant vocalized for at least 80% of the trials for at least one session without engaging in picture exchange with the book 0.91 m, the book was then moved to the same table as the participant, but across the table, 0.76 m. Finally, if the participant vocalized for at least 80% of the trials for at least one session without engaging in picture exchange with the book across the table the book was moved to directly in front of the participant on the table, 0 m. Similar to the delay to reinforcement phase, if the child vocalized using the target vocalization at any time during the trials, they were immediately provided with the reinforcer. If picture exchange occurred during the response effort procedure, the delay used at the onset of the response effort condition remained constant throughout the remainder of the study. The communication book was gradually moved closer to the individual to determine whether or not the individual would continue vocalizing or if they would switch back to picture exchange when the response effort was again decreased. These procedures were similar to that of Buckley and Newchok (2005) where response effort was altered for a FCT response.

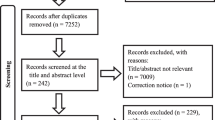

Research Design

A concurrent multiple probe design across participants (Gast and Ledford 2014) was used to evaluate the effects of implementing a delay to reinforcement during PECS to increase target vocalizations as mands for preferred items. Wilburn began intervention first due to his consistent but infrequent incorporation of vocalizations during the PECS exchange. Baseline conditions included at least five PECS sessions. The first participant moved to intervention once the baseline data were stable. Intervention began for the second participant once the first participant vocalized for 80% of the trials across at least two sessions. Intervention began for the third and fourth participants simultaneously once the second participant vocalized for 80% of the trials across at least two sessions.

Results

Figure 1 shows the percent of trials with correct picture exchange and the percent of trials in which independent intelligible word vocalizations occurred. Delay to reinforcement in conjunction with PECS resulted in an increase in independent intelligible word vocalizations when implemented with three of the participants. Results also indicate that by moving the location of the PECS notebook participants decreased picture exchanges, but continued to produce independent intelligible word vocalizations consistent with the vocalizations that began during intervention.

Wilburn’s independent intelligible word vocalizations remained relatively the same compared to baseline during the 1-s, 2-s, and 3-s delay. During the 4-s delay his independent intelligible word vocalizations increased from 20% of trials to 100% of trials, and remained high during the 5-s delay. During the 5-s delay, Wilburn continued to engage in picture exchange before vocalizing. Wilburn stopped exchanging pictures to request items when the book was moved 0.91 m away within eyesight. He continued to use independent intelligible word vocalizations without picture exchange to request when the book was moved back within reach at 0.76 m away and when the book was moved within arm’s reach. Wilburn continued to vocalize for 100% of the trials and did not exchange pictures throughout maintenance.

Manny’s independent intelligible word vocalizations increased similar to Wilburn’s, once he reached the 3-s delay. Manny engaged in independent intelligible word vocalizations for 80% of the trials during the 5-s delay. Once the book was 0.91 m away, Manny stopped exchanging pictures to mand for preferred items and engaged in independent intelligible word vocalizations to mand for items for 100% of the trials across two sessions. The book was then moved .76 m away. During this phase, Manny continued to vocalize for 100% of the trials and stopped engaging in picture exchange. Next, the book was moved within arm’s reach. During this phase, Manny began exchanging pictures again and his independent intelligible word vocalizations decreased compared to previous conditions. After four trials with the book within arm’s reach, the book was moved back across the table, .76 m for one session and on the same day the book was moved back within arms reach. For both of these sessions, Manny vocalized 100% of the trials and stopped exchanging pictures. However, Manny did often point to pictures and look at pictures while vocalizing and before vocalizing. Manny continued to vocalize for 100% of the trials and did not exchange pictures throughout maintenance.

Nelson’s independent intelligible word vocalizations increased by 50% during the first implementation of the 1-s delay, and continued to exchange pictures for 100% of trials for three sessions. Once the delay was gradually increased to 6 s, Nelson engaged in independent intelligible word vocalizations for at least 80% of the trials. During this phase, Nelson continued to engage in picture exchange. Nelson used independent intelligible word vocalizations without picture exchange to request only when the book was originally moved 0.91 m away and eventually moved closer at .76 m away. However, when the book was moved within arm’s reach, the final move, Nelson began exchanging pictures again while simultaneously vocalizing. Due to Nelson’s use of word approximation vocalizations, researchers decided not to move the book similarly to Manny.

Arman began intervention at the same time as Nelson. He did not produce independent intelligible word vocalizations during the 1-s delay session, but did produce independent unintelligible word vocalizations during the delay period. Arman’s vocalizations during PECS were indistinguishable from other vocalizations to be considered a mand for the preferred item. Arman produced independent intelligible word vocalizations for 20% of the trials during the seventh session of intervention, which included a 7-s delay. The delay was not increased passed 8-s due to the lack of therapeutic trend in the data.

Discussion

The study demonstrated the effects of delay to reinforcement on the increase in target vocalizations (intelligible word vocalizations or word approximation vocalizations) when using PECS. The study also demonstrated the effects of increasing response effort in the form of requiring travel to and from the communication book on the decrease of picture exchange when individuals had the ability to vocalize. A functional relation was demonstrated through a concurrent multiple probe design in which the delay to reinforcement was staggered across participants. Three of the four participants (Wilburn, Manny, and Nelson) began using independent intelligible word vocalizations in conjunction with picture exchange to mand for specific items. Three participants (Wilburn, Manny, and Nelson) used vocalizations solely to communicate when their picture book was moved 0.91 m away. Additionally, two (Wilburn and Manny) of the four participants used only independent intelligible word vocalizations to communicate when their picture book was returned within arm’s reach.

This study was an important extension of the work conducted by Ganz and Simpson (2004) because it provided a systematic procedure to incorporate with typical PECS training to increase vocalizations. Additionally, the study was an extension to Tincani et al. (2006) because it provided further evidence to support the use of a delay to reinforcement to increase vocalizations when implementing PECS. The findings support the use of a delay during Phase III while previous research focused on the use of a delay during Phase IV (Tincani et al. 2006). The study went beyond increasing vocalizations by transferring modalities of communication from picture exchange to vocalizations for three participants using a concurrent schedule arrangement. The variation in responding may have been influenced by the response class hierarchy (Baer 1982). The immediacy of reinforcement, the rate of reinforcement, the response effort required, and the likelihood of punishment often influence the response hierarchy.

When participants begin vocalizing independently to communicate, they increase access to their community and reduce the number of individuals who have difficulty understanding their wants and needs. These results extend and corroborate the findings of Schlosser and Wendt (2008) and Sulzer-Azaroff et al. (2009) that AAC in the form of PECS can assist in the development of vocalizations in addition to providing individuals with communication deficits a functional way to communicate their wants and needs. PECS is a low cost tool and evidence-based practice (Wong et al. 2014) that can be easily implemented in classrooms and homes with limited resources. The use of a delay to reinforcement has been used in conjunction with other AAC devices (Carbone et al. 2010; Gevarter et al. 2016) but this research provides evidence to support that it can also be used with PECS to increase vocalizations. Additionally, this research provides hope for families and practitioners that PECS does not have to be an end point for communication, but can be can be modified in order to aide in the development of vocalizations. From a practical standpoint, therapists may consider using delays to increase responding across modalities in an effort to mitigate issues when one response is less effective.

One critical finding in the study relates to response effort. Response effort was increased once picture exchange was combined with vocalizations for 80% of the time. At this point the book was moved away from the participant then gradually closer to the participant. The participant had the ability to stay in their chair and vocalize to communicate or to get out of their chair and use picture exchange. Wilburn, Manny, and Nelson did not get out of their chair to engage in picture exchange, but used vocalizations when the book was moved away. Manny and Nelson began engaging in picture exchange once the book was moved back within arms reach. This information suggests that manipulating response effort can result in a transfer of communication modality. The history of reinforcement with PECS is likely responsible for Manny and Nelson returning to picture exchange once the communication book was moved back within arm’s reach.

There are several limitations to the study that necessitate discussion. First, a measurement system was not used to track change outside of the experimental session. This type of evaluation would have helped to determine if the behaviors generalized outside of the snack setting. Additionally, documenting the changes in word production that occurred for Nelson would have provided more insight on the changes that occurred throughout the course of the study. Future research should consider collecting these data to determine the implications of PECS on the topographical development of vocalizations. As mentioned in the method section, participants did not have access to their PECS book outside of the research setting. While this was important for experimental control, this may have lead to a potential limitation. For example, restricted access of the PECS book may have increased the reinforcing value of the available consequences. Therefore, these data may not be representative of a more natural setting where individuals have unrestricted access to their PECS materials. Another limitation includes the fact that requests were often limited to food items due to restricted preferences of the students and the time of day of implementation, which was snack. Sessions also occurred at a table separate from the rest of the class. The class often had the opportunity to watch videos during snack on the projector. This may have served as a distractor to participants, because on some days the video was more preferred than the available items. Another limitation includes the staffing ratios and personnel. The classroom was operated through the local university and was staffed by a team of doctoral and masters level students. The ratio of students to staff was at least one staff member to two students at all times. All of the teachers and data collectors were familiar with PECS, and had experience implementing PECS in multiple settings. A specific limitation to Nelson was that he was also receiving training through the speech and language pathologist on Language Acquisition and Motor Planning (LAMP) while the study was taking place. Due to the limited research on LAMP the classroom staff agreed to continue working on PECS. Finally, maintenance probes were not conducted for Nelson and Arman. This information would have been particularly useful for Nelson to determine if he altered responding after the course of the study. Further research should be conducted to consider the limitations and to replicate the findings.

Despite the limitations, the results suggest that a delay to reinforcement in conjunction with PECS has the potential to increase target vocalizations. Additional research is needed to further investigate response effort as it relates to PECS and vocalization development when a child is engaging in unintelligible approximations. The fourth participant engaged in approximations of the target vocalizations occasionally, but there were no plans to shape the approximations. Further research could examine means for shaping approximations of vocalizations within the delay to reinforcement framework (Carbone et al. 2010). When the book was moved within 15.24 cm for Manny and Nelson, the presence of the book may have served as a discriminative stimulus for picture exchange considering both participants switched from using vocalizations exclusively to reinstating the use of picture exchange. Another area worthy of exploration includes the variables and performance patterns that would help predict when interventionist should begin to emphasize a transition from PECS to vocalizations. Frost and McGowan (2011) outlined five questions that should be answered prior to terminating access to pictures. The questions revolved around the number of spoken words in comparison to the pictures being exchanged, the rate of initiation with pictures compared to speech, sentence structure with pictures compared to that of spoken words, the ability for others to understand the speaker without training, and the rate of responding when compared to the that of PECS (Frost and McGowan 2011).

The findings described are preliminary and additional replications and generalizations are necessary. While three of the four students successfully altered their responding from one response (AAC) to another (vocalizations), further research should be conducted to determine for whom this type of intervention is best. The participant characteristics should be carefully considered when attempting replication to ensure individuals have the pre-requisite skills needed to engage in multiple responses.

References

Alpern, G. D. (2007). Developmental profile 3 (DP-3). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Baer, D. M. (1982). The imposition of structure on behavior and the demolition of behavioral structures. In H. E. Howe (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (vol. 29, pp. 217–254). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bernstein, H., & Sturmey, P. (2008). Effects of fixed-ratio schedule values on concurrent mands in children with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 362–370.

Bernstein, H., Brown, B., & Sturmey, P. (2009). The effects of fixed ratio values on concurrent mand and play responses. Behavior Modification, 33, 199–206.

Blischak, D. M., Lombardino, L. J., & Dyson, A. T. (2003). Use of speech-generating devices: In support of natural speech. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19, 29–35.

Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (1994). The picture exchange communication system. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 9, 1–19.

Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (2001). The picture exchange communication system. Behavior Modification, 25, 725–744.

Buckley, S., & Newchok, D. (2005). Differential impact of response effort within a response chain on use of mands in a student with ASD. Research In Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26, 77–85.

Carbone, V. J., Sweeney-Kerwin, E. J., Attanasio, V., & Kasper, T. (2010). Increasing the vocal responses of children with autism and developmental disabilities using manual sign mand training and prompt delay. Journal of Applied Behavior Analyis, 43, 705–709.

Cooper, J., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Columbus: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Frost, L., & McGowan, J. (2011). Strategies for transitioning from PECS to SGD: Part I. Overview and device selection. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20, 114–118.

Ganz, J. B., & Simpson, R. L. (2004). Effects on communicative requesting and speech development of the picture exchange communication system in children with characteristics of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 395–409.

Ganz, J., Earles-Vollrath, T., Heath, A., Parker, R., Rispoli, M., & Duran, J. (2012). A meta analysis of single case research studies on aided augmentative and alternative communication systems with individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 60–74.

Gast, D. L., & Ledford, J. R. (2014). Single case research methodology: Comparison designs. New York: Routledge.

Gevarter, C., O’Reilly, M. F., Kuhn, M., Mills, K., Ferguson, R., Watkins, L., Sigafoos, J., Lang, R., Rojeski, L., & Lancioni, G. (2016). Increasing the vocalizations of individuals with autism during intervention with a speech-generating device. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49, 17–33.

Mirenda, P. (2003). Towards functional augmentative and alternative communication for students with autism: Manual signs, graphic symbols, and voice output communication aids. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 203–216.

Newman, L., Wagner, M., Knokey, A.M., Marder, C., Nagle, K., Shaver, D., Wei, X., with Cameto, R., Contreras, E., Ferguson, K., Greene, S., & Schwarting, M. (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). (NCSER 2011–3005). Menlo Park: SRI International.

Schlosser, R. W. (2003). Effects of AAC on natural speech development. In R. W. Schlosser (Ed.), The efficacy of augmentative and alternative communication: Towards evidence based practice (pp. 404–425). San Diego: Academic Press.

Schlosser, R. W., & Wendt, O. (2008). The effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: A systematic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 212–230.

Schroeder, S. (1972). Parametric effects of reinforcement frequency, amount of reinforcement, and required response force on sheltered workshop behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 431–441.

Sigafoos, J. (2000). Communication development and aberrant behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 35, 168–176.

Sulzer-Azaroff, B., Hoffman, A. O., Horton, C. B., Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (2009). The picture exchange communication system (PECS): What do the data say? Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 89–103.

Sunberg, M. L., & Partington, J. W. (1998). Teaching language to children with autism and other developmental disabilities: Augmentative communication. Concord: AVB Press.

Tincani, M. (2004). Comparing the picture exchange communication system and sign language training for children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19, 152–163.

Tincani, M., Crozier, S., & Alazetta, L. (2006). The picture exchange communication system: Effects on manding and speech development for school-aged children with ASD. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 41, 177–184.

Wodka, E. L., Mathy, P., & Kalb, L. (2013). Predictors of phrase and fluent speech in children with ASD and severe language delays. American Academy of Pediatrics, 131, 1128–1134.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., et al. (2014). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism Spectrum disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was not funded.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cagliani, R.R., Ayres, K.M., Whiteside, E. et al. Picture Exchange Communication System and Delay to Reinforcement. J Dev Phys Disabil 29, 925–939 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9564-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9564-y