Abstract

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) report significantly higher stress than parents of children with other developmental disorders. Symptoms that overlap with the autism spectrum are often present in other developmental disorders, which could significantly increase parenting stress. Additionally, the severity of ASD symptoms within a group of children with ASD can greatly vary. In the present study, problem behaviors, cognitive and adaptive functioning, and parenting stress were examined in a group of 40 children aged 2–5 years who were referred for an autism evaluation. The children presented with varying levels of symptoms often associated with ASD, and some met criteria for an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. This approach allowed for both categorical and dimensional consideration of ASD-associated symptoms and the relation to parenting stress in children with and without autism. When examined based on ultimate clinical diagnosis of ASD or non-ASD, child behavior problems and parenting stress were similar across groups. Clinician-based autism severity ratings (based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) did not significantly predict parenting stress; however, parental report of the severity of ASD-associated symptoms (from the Social Responsiveness Scale) showed a significant relation to stress. Cognitive ability did not uniquely contribute to stress. Problem behaviors as assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist accounted for the largest proportion of the variance in parenting stress; adaptive behaviors and severity of parent- or clinician-rated autism-associated symptoms did not uniquely contribute above and beyond problem behaviors. Parents who reported more behavior problems or more autism-associated symptoms reported higher parenting stress. Clinical applications and the need for more research on parenting stress and problem behaviors in children displaying autism symptomatology are highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well known that elevated parenting stress predicts negative outcomes on functioning, including parental depression and anxiety, marriage problems, family functioning difficulties, and lower parental physical health (Gallagher et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2011; Johnston et al. 2003; Maxted et al. 2005; Singer 2006; Taylor and Warren 2012). To date, several studies have suggested that parents of children with developmental disabilities are at a high risk for experiencing parenting stress (Eisenhower et al. 2005; Estes et al. 2009; Miodrag and Hodapp 2010; Tervo 2012) related to child traits such as poor social skills, behavior (Neece and Baker 2008) or attention problems (Tervo 2010), withdrawal, or emotional dysregulation (Tervo 2012). In particular, some research suggests higher stress in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in mothers of children with developmental delay (Dąbrowska and Pisula 2010; Rodrigue et al. 1990; Schieve et al. 2007). ASD affects about 1 in 68 children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014) and is defined by deficits in socio-communicative behaviors, the presence of odd or stereotypical behaviors, a restricted range of interests, and, sometimes, intellectual or language deficits. However, children with other developmental disabilities frequently display symptoms that overlap with those of children with ASD (Hepburn et al. 2008; Klein-Tasman et al. 2009), including significantly more behavioral and emotional problems than typically-developing peers (Baker et al. 2003; Eisenhower et al. 2005). Because symptoms associated with ASD vary in severity along a broad continuum, it is potentially helpful to study relations between the severity of these ASD-associated symptoms and parenting stress, as well as contributors to that stress, regardless of diagnostic classification.

Research about ASD suggests a fourfold increase in parenting stress compared to unaffected groups (Silva and Schalock 2012), with stress above the 90th percentile in some samples (Mori et al. 2009). Some of the elevated stress experienced by parents of children with ASD may be related to the hallmark characteristics of autism, such as deficits in language, communication, or social skills (Neece and Baker 2008) and odd, repetitive, or stereotypical behaviors, which are present at higher rates in children with ASD. However, some of the symptoms required for a diagnosis of ASD (e.g., restricted and repetitive behaviors) are also present at lower rates in other disorders. Other symptoms commonly associated with ASD but often presenting in other child groups have also been theorized as strong predictors of parenting stress. These include, most prominently, problem behaviors (Baker et al. 2003; Hastings 2002; Mori et al. 2009; Weiss et al. 2003, 2012) and difficulty with adaptive behavior (Hall and Graff 2011), such as self-regulation difficulties (Davis and Carter 2008) and trouble fulfilling basic self-care needs, which can worsen behavior problems (Dyches et al. 2004).

Parenting a child who displays symptoms that overlap with the autism spectrum – whether or not the child has an ASD diagnosis – may expose parents to clinically significant stress and related negative outcomes, including less effective implementation of interventions (Osborne et al. 2008). Given what we know about stress and its effects on both parent and child, it is to the advantage of all involved – caregivers, clinicians, and children – to understand factors that contribute to elevated stress and to behave proactively in managing these factors in addition to treating the stress itself. Parents and clinicians armed with knowledge of contributors to stress and the available supports and resources may be able to boost the effectiveness of interventions targeting the child’s difficulties. For example, research indicates that clinicians, such as primary care physicians, are attuned to the potential for parenting stress to affect many areas of family functioning in families with a child who has an ASD (Hutton and Caron 2005). Given that parents of children with a diagnosis of ASD are highlighted in current literature as experiencing the highest stress levels, clinicians may expect to see and address clinical-range stress moreso in parents of children with ASD than in parents of other child groups. Therefore, it is necessary to consider relations between parenting stress and symptoms that overlap with the autism spectrum, even in children without ASD.

The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al. 1999) is a gold-standard instrument that aids in the diagnosis of ASD. Until recently, this instrument did not differentiate between children who marginally met for an ‘autism’ diagnosis and those who largely exceeded the cutoff. However, a “severity index” has been developed (Lord et al. 2012). An ADOS comparison score (ADOS-CS) allows clinicians to consider the severity of the autism-related symptomatology, evaluate change over time, and gain important information about symptoms above and beyond mere diagnostic classification (see Bishop et al. 2007). By using the ADOS-CS we extend the current literature by examining parenting stress related to autism symptomatology even in parents of children who did not meet criteria for an ‘autism spectrum’ diagnosis.

The current study represents an extension of prior research by two particular studies which present somewhat conflicting outcomes. Estes et al. (2009) examined the influence of child diagnosis, adaptive functioning, and problem behaviors on parenting stress and psychological distress in parents of children with either ASD or non-ASD developmental delay (DD). Mothers in the ASD group reported significantly more parenting stress, depression, and anxiety than did mothers in the DD group. The ASD group showed more problem behaviors and weaker daily living skills than did children with DD. Child problem behaviors, measured by the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC; Aman and Singh 1986), accounted for variability in parenting stress over and above diagnosis or adaptive skills. These findings lend support to the idea that the amount of problem behaviors present, rather than diagnosis, has the greatest impact on stress. In contrast, Eisenhower et al. (2005) examined stress in mothers of children with various intellectual disability syndromes and the contribution of problem behaviors within these syndromes. Maternal stress was higher in mothers of children with ASD. Variance in maternal stress was still present after cognitive level and behavior problems, as measured by a different parental report measure, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001), were accounted for. (This study did not include assessment using standard diagnostic tools or confirmation of autism classification.) Eisenhower and colleagues indicate that maternal stress patterns parallel child behavior problems but that autism diagnosis contributes to stress additionally, after behavior problems are accounted for. They suggest that other characteristics of a child’s syndrome may be related to parenting stress (Eisenhower et al. 2005). Based on these findings, we propose that the severity of autism-associated symptoms uniquely contributes to parent-reported stress.

The discrepancy between the two referenced studies in both findings and the different measures of problem behavior contributes to the rationale for the current investigation. To this point, no study has included both the ABC and the CBCL as measures of problem behavior within the same sample. Furthermore, levels of parenting stress have not been related to the severity of autism-related symptoms based on either clinician or parent perspective. Prior research has taken a categorical approach to syndrome-stress relations, but a dimensional approach to autism-associated symptom severity regardless of diagnosis may provide helpful insight into parenting stress. We suggest that predicting stress based on diagnosis or symptom domain alone is helpful but insufficient; the particular role of the severity of autism-associated symptoms (separate from diagnosis per se) has not been investigated.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

In the current study we aim to extend prior research by delving into the complexities of relations between parenting stress and features that overlap with the autism spectrum in children who were all referred for an autism evaluation. Of chief interest is whether an estimation of autism-related symptomatology contributes to understanding parenting stress levels – regardless of the ultimate diagnosis - or whether problem behaviors, cognitive ability, and adaptive skill level sufficiently predict parenting stress. We will explore this research question using two different measures of autism severity (one clinician and one parent) and two different measures of child problem behaviors (ABC and CBCL). Inclusion of both problem behavior measures in a single study may help clarify previous findings (i.e., Estes et al. 2009; Eisenhower et al. 2005). Finally, given that all children were referred for an autism evaluation but only half of the children were ultimately diagnosed with an ASD, the sample will be also grouped by ASD vs. non-ASD diagnosis to examine if there are indeed differences in problem behaviors and differences in parenting stress between groups.

Most centrally, it is hypothesized that the clinician-reported severity as measured by the ADOS-CS, as well as the parent-reported severity of autism-associated symptoms, will be significantly related to parenting stress; higher observed or reported severity is expected to predict higher parenting stress. Further, based on prior research findings, we hypothesize that problem behaviors will account for most of the variance in stress when using either measure of problem behavior (ABC or CBCL). It is also hypothesized that cognitive and adaptive skills will not make statistically significant additional contributions to the prediction of stress beyond problem behaviors using either measure. Based on mixed findings regarding the amount of variance accounted for by problem behaviors and relations between the ABC and autism-related symptoms (see Measures section), we expect that the severity of autism-associated symptomatology (parent- and clinician-rated) will uniquely predict variance in parenting stress after accounting for problem behaviors as measured by the CBCL but not by the ABC. Lastly, when the sample is separated based on ASD vs. non-ASD diagnosis, it is hypothesized that the ASD group will show higher levels of child problem behaviors and parenting stress than the non-ASD group.

Materials and Methods

All study procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board and were performed according to ethical standards.

Participants

Forty children ages 2 through 5 years were referred based on parent, teacher, or physician concerns about a possible autism spectrum disorder. Non-English-speaking children and children with a pre-existing mixed etiology diagnosis (e.g., Down syndrome) or a serious medical condition (i.e., brain tumor) were excluded. Data from 35 of these children were collected during a study of relations between growth and ASD; 5 additional children were referred for autism assessment at a later time. Study staff obtained informed consent before conducting procedures. All participants were then diagnosed by a Licensed Psychologist abiding by DSM-IV (APA 2000) criteria, based on administration of the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994; Rutter et al. 2003) and the ADOS, structured observation, and a clinical interview. 19 children were diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD; either Autistic Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified) by the clinician, and 21 children were considered non-ASD. A small number of children (n = 3) just met threshold for an autism spectrum on the ADOS but were not diagnosed based on differential diagnosis and clinical judgment. Most children in the non-ASD gcroup were diagnosed with a different DSM-IV primary disorder (including Developmental Disorder, Receptive or Expressive Language Disorder, ADHD, Social Anxiety. Phonological Disorder, or Disruptive Behavior Disorder-NOS, or a combination); one child was given no diagnosis. See Table 1 for demographic data.

Measures

The measures and materials used are widely accepted in research and clinical settings with young children and are all considered reliable and valid for children with developmental disabilities. The measures were chosen to provide a picture of the child’s cognitive ability, autism symptoms, behavior problems, adaptive abilities, and social abilities, as well as the parents’ perceived stress.

Cognitive ability: The Early Learning Composite Score from the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen 1997) was used as a reflection of each child’s cognitive functioning. The Mullen is a standardized measure used to approximate a child’s level of development in regards to both cognitive and motor skills. It is standardized for children ages 0 to 68 months.

Adaptive functioning and problem behavior: The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Interview Edition (VABS, Sparrow et al. 1984), is a standardized, commonly-used interview administered to caregivers. It measures adaptive behavior across the domains of communication skills, daily living, motor skills, and socialization. The Daily Living Skills domain score was used as a measure of the child’s adaptive abilities in the areas of personal, domestic, and community living skills.

To measure problem behaviors, the total scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and Child Behavior Checklist, Ages 1 ½ - 5 (CBCL) were used in this study. The ABC is a checklist designed to assess symptoms of problem behavior in children and adults with intellectual disabilities. The ABC consists of five subscales measuring problem behaviors, including (I) Irritability, Agitation, Crying; (II) Lethargy, Social Withdrawal; (III) Stereotypic Behavior; (IV) Hyperactivity, Noncompliance; and (V) Inappropriate Speech. Notably, relations between ratings on the ABC and parental report of autism-associated symptoms, as assessed by the ADI-R, have been found in past research (Lecavalier et al. 2006). More recent direct examination of relations between the ABC and autism severity as indicated by the ADOS-CS found that ratings on some subscales of the ABC (Lethargy/Social Withdrawal; Stereotypic Behavior) seem to be related to the ADOS-CS for less verbal children (Kaat et al. 2014). (It should be noted that while the ABC Total score was used in prior research about relations between problem behavior and stress (Estes et al. 2009), the developers of the ABC (Aman and Singh 1986) caution against its use due to concerns about the construct validity of this overall score.)

The CBCL was used as a measure of overall child problem behaviors. The CBCL is an empirically-based, standardized, 100-question parent-report measure used widely to asses internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors in young children. Each behavior is rated on a 0–2 Likert scale. The CBCL includes a syndrome profile and problem scales assessing emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, somatic complaints, withdrawal, sleep, attention, and aggression. DSM-oriented scales include affective problems, anxiety problems, pervasive developmental problems, attention deficit/hyperactivity problems, and oppositional defiant problems. Summary scores include internalizing, externalizing, and total problems, and summary T-scores at or above 64 are clinically significant.

Parenting stress: The Parenting Stress Index, Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin 1995) is a questionnaire consisting of 36 items designed to create a comprehensive picture of stress in parents of children with developmental disabilities. This questionnaire is comprised of three scales (Parental Distress, Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult Child), which yield a Total Stress score. Scores at the 85th percentile or above are interpreted as high. The Parental Distress scale measures the extent to which an individual feels stress associated with the parental role, including parenting competence, restrictions on life due to parenting, parental conflict, depression, and social support. The Parent–child Dysfunctional Interaction scale measures the extent to which a parent finds interactions with his/her child unrewarding and below expectations. The Difficult Child scale measures how easy or difficult a parent rates his/her child. The Total Stress score measures how much stress related to parenting that the parent experiences. The PSI is broadly accepted as a reliable measure of parenting stress for parents of children with and without disabilities and in children with autism (Zaidman-Zait et al. 2010). The maternal Parental Distress raw score was used in order to consider stress apart from the influence of child problem behaviors.

Autism severity: The ADOS (and its revision, the ADOS-2) is a standardized semi-structured measure based on play interactions with the administrator. It assesses ASD symptomatology, including abnormal communication (e.g., eye contact), social interaction, and restrictive/repetitive behaviors. Four modules are available for administration based on expressive language ability. A total score is then compared to cutoff scores for classification of autism or the broader range of autism spectrum disorder. Gotham et al. (2007) published new algorithms and severity scores for autism symptoms based on the ADOS. These new algorithms are now reflected in the ADOS-2. Calculation of a Comparison score (ADOS-CS) that reflects severity is now possible in addition to the ADOS classification (nonspectrum, autism spectrum, autism). Comparison scores range from 1 to 10, allowing for a direct comparison of severity estimation across modules (see Gotham et al. 2007, 2009). The ADOS-CS is a reliable and valid indicator of severity of autism symptomatology and was used as one measure of severity in this study.

The total score from the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino and Gruber 2005) was also used to measure parent-reported social responsiveness as another estimate of autism symptom severity. The SRS is a 65-item parent or teacher questionnaire which measures the degree of social deficits typically associated with ASD in both children and adolescents. It assesses domains of social awareness, social information processing, reciprocal social interaction, social anxiety/avoidance, and stereotypic/repetitive behaviors.

Procedure

A diagnostic evaluation and interview was carried out at the Child Neurodevelopment Research Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for each participant. Parent-reported data obtained prior to the in-person portion of the evaluation included a written demographic questionnaire and a series of questionnaires about the child’s behavior and socio/communicative abilities, as well as self-report of parental stress levels. Trained examiners administered the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and the language-appropriate module of the ADOS. A Licensed Psychologist diagnosed all children based on DSM-IV TR (American Psychiatric Association 2012) criteria using the ADOS, ADI-R, and clinical judgment (Lord et al. 1999). All examiners were reliable on administration of the ADOS and ADI-R.

Statistical analysis, testing for normality and outliers: IBM SPSS for Windows version 22 and R version 3.1.1 were used for these analyses. Potentially influential bivariate outliers in Pearson correlations were identified using the outlier test of the Car package in R that tests for significant deviations in the studentized residuals of the correlation (Stevens 1984). Potential outliers for variables included in single and independent t-tests were identified as values with extreme z scores (+ − 3.29) as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Normality of Pearson correlations and single variables was assessed by testing for statistically significant deviations for skew or kurtosis of the distribution of residuals of each relation (p < 0.01; Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). Similarly, for the multiple regression models, potential outliers were identified by the outlier test (deviations of studentized residuals) and normality was examined by testing for significant deviations in skew and kurtosis of the residuals. A p-value of 0.05 was used in interpreting statistical significance.

Based on previous research (i.e., Estes et al. 2009) examining contributions of problem behaviors, daily living skills, and diagnosis to parenting stress in parents of children with ASD or developmental delay, we expected to find an overall effect size of about R 2 = 0.30 for regression analyses. Based on our sample size of 40 and this effect size, all multiple regression models had adequate power (over 0.80) to find a nonzero overall effect size. For hierarchical multiple regressions, we first entered measures of parent-rated problem behavior followed sequentially by adaptive skills in line with methodology from prior research (Eisenhower et al. 2005; Estes et al. 2009). Parent ratings of autism-associated symptoms were entered prior to clinician autism symptomatology ratings to examine whether clinician ratings provided additional insight to the variance in parenting stress after considering all parent-report measures.

Results

Assumptions of normality were fulfilled and no statistically significant outliers were identified. Some relations were interpreted with regard to effect size. Effect sizes are noted for correlations according to Cohen (1988) as follows: 0.1 = small effect; 0.3 = medium effect; 0.5 = large effect. Accordingly, for R 2 values, effect sizes were interpreted as follows: 0.01 = small effect; 0.09 = medium effect; 0.25 = large effect.

Mean scores on the PSI-SF Parental Distress scale fell at the 70th percentile (high normal range; “normal” ranges from the 15th-85th percentiles). In the typical population, 20 % of parents would be expected to report scores in the clinical range (above the 85th percentile). In our parent sample, 32.5 % (n = 13) reported clinical-range scores on this scale. Mean Total Stress was at the 90th percentile, indicating elevated stress levels on average. While 15 % of parents in the typical population would be expected to report clinical-range total stress, 60 % (n = 24) of our sample reported clinical-range total stress. Age and gender did not significantly contribute to the model. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics.

Relations of Severity of Autism-Associated Features to Parenting Stress

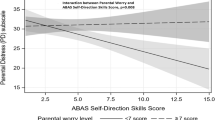

Partial Pearson correlations (controlling for cognitive ability, though cognitive ability did not affect stress) were examined between clinician ratings (ADOS-CS) or parent ratings (SRS total score) and parenting stress to determine whether severity of the features overlapping with the autism spectrum, alone, predict stress. Partial correlations between ADOS-CS and parenting stress as measured by the raw Parental Distress score on the PSI-SF were not significant (r = 0.05; p = 0.81); a small effect size was noted. However, partial correlations between the SRS and the Parental Distress score were significant (r = 0.42 p = 0.016), with a medium effect size. Partial correlations between clinician ratings on the ADOS-CS and parent ratings on the SRS were not significant. (r = 0.19; p = 0.28), with a small effect size.

Contributions of Problem Behavior, Adaptive Functioning, and Autism-Associated Symptoms to Parenting Stress

Using a multiple regression model predicting parenting stress, age (p = 0.78), gender (p = 0.63), and cognitive ability (p = 0.20) did not make significant unique contributions to mother-reported parenting stress as measured by the raw score on the Parental Distress scale of the PSI-SF. Therefore, age, gender, and cognitive ability were not included in any further regression analyses.

We next investigated the contributions of problem behavior (using separate analyses for the ABC or CBCL), adaptive skills (specifically the Daily Living score), and severity of associated features of ASD (clinician-rated and parent report) to the prediction of parenting stress. Hierarchical multiple regressions were used to examine relations of the independent variables described above to the dependent variable, parenting stress (Parental Distress scale of the PSI-SF). Variables were entered sequentially as follows: ABC (or CBCL) raw total in Block 1, Daily Living Skills in Block 2, SRS raw total in Block 3, and ADOS-CS in Block 4.

In the analysis using ABC Total raw score as an index of problem behavior, the ABC initially trended toward significantly predicting stress (p = 0.077) in Block 1, but in the final model this trend no longer existed. In the final model, problem behaviors on the ABC accounted for 6.5 % variance in stress, which was not significant (p = 0.13), daily living skills explained 3.6 % additional variance in stress, and the SRS explained 6.3 % variance in addition to problem behaviors and adaptive skills, while the ADOS-CS only explained 0.14 % additional variance in stress; none of these added variables contributed significantly above and beyond problem behaviors. In the final model, all four predictors accounted for 26.2 % of the variance in parenting stress, but none of the predictors made statistically significant unique contributions to the prediction of parenting stress. See Table 3 for results of this analysis.

In the analysis using CBCL total raw score as an index of problem behavior, the CBCL initially statistically significantly predicted 33.2 % of the variance in parenting stress (p < 0.001). In the final model, problem behaviors on the CBCL accounted for 15.4 % (p = 0.012) variance in stress, daily living skills explained 1.4 % additional variance in stress, and the SRS explained 1.5 % variance in addition to problem behaviors and adaptive skills, while the ADOS-CS only explained 0.06 % additional variance in stress. In the final model, all four predictors accounted for 37.2 % of the variance in parenting stress, but only the CBCL made a statistically significant unique contribution to the prediction of parenting stress. See Table 3 for results of analyses using the CBCL. Additionally, the CBCL was a statistically significantly better predictor of parenting stress than the ABC, improving prediction above and beyond the final model using the ABC, with a medium effect size noted (R 2 = 0.19, p = 0.0059).

Group Comparisons

The sample was split based on ASD vs. non-ASD diagnosis. Children in the non-ASD group demonstrated a higher level of intellectual functioning than did children in the ASD group.

Using independent samples t-tests, group differences were examined separately for the total raw score on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and the raw Total Problem Behaviors score from Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). No significant differences were found between groups for behavior problems as measured by the ABC or CBCL (see Table 4).

Independent samples t-tests comparing stress between mothers of the ASD and DD groups (using the raw Parental Distress and Total Stress scaled scores) also showed no significant differences. Mean scores on the Parental Distress scale fell at the 63rd and 60th percentiles (“normal” range) for ASD and DD groups, respectively. Total Stress was at the 78th and 76th percentiles for ASD and DD groups, respectively, showing somewhat elevated stress levels but no significant differences between groups. See Table 4 for results of all group comparisons.

Discussion

In the current study, a dimensional approach was used to examine relations between autism-associated symptomatology and parenting stress. Consistent with prior research, the rate of high parenting stress was elevated in this sample. Parent-reported, but not clinician-reported, autism-associated symptom severity was significantly predictive of parenting stress when examined separately. When child characteristics were examined together in relation to parenting stress, child behavior problems accounted for most of the variance in stress, with other child characteristics contributing little above and beyond. Furthermore, parents who reported high levels of child behavior problems also reported high levels of parenting stress at the time of the ASD evaluation, and there were no differences in child problem behaviors or parenting stress between groups of children who were ultimately diagnosed ASD vs. non-ASD. Findings support that there exists the potential for high stress in parents of children referred for an autism evaluation and in particular for parents who report high levels of child symptoms. This knowledge could assist clinicians in attuning to a family’s needs and helping parents prepare for and cope with parenting stress by offering services or referrals that bolster parental competence, emphasize support, and target child behavior problems or autism-associated symptoms.

Relations of Severity of Autism-Associated Symptoms to Parenting Stress

Clinician-reported severity of autism symptomatology did not significantly predict parenting stress, which could be in part due to low variability in this sample’s ADOS-CS scores. However, alone, parent report of the severity of autism-related symptoms significantly predicted parent report of stress. One explanation for the stronger relations between the parental report measures is that parents’ perception of ASD-associated symptoms is related to their perception of their own parenting stress: if they report more child symptoms, they also report higher stress, at least in the context of the current study where these variables were measured during the process of a diagnostic evaluation. This study included families in which parents or another caregiver noticed symptoms that were suspected signs of autism. Consequently, parents may have been highly attuned to any sign that their child was exhibiting symptoms related to autism around the time of the evaluation. Another possibility is that parents seeking help may endorse symptoms (their own and their child’s) at a higher rate. Furthermore, simply knowing that the child was getting an evaluation for a possible autism diagnosis could increase parenting stress, regardless of whether the clinician saw fit to diagnose the child with an autism spectrum disorder and regardless of the ADOS-CS. Because the literature suggests higher stress in parents of children with an ASD, it is plausible that parents who perceive autism-associated symptoms may experience higher levels of stress. It is notable, however, that parents with high parenting stress are not necessarily the parents of children with higher clinician-observed autism severity ratings. If clinicians are attuned to this knowledge and do not assume that a low ADOS-CS rating indicates low stress, they can effectively assess for stress and direct parents to treatment options that have recently been shown to reduce parenting stress (see Singer et al. 2007) and improve psychological functioning, such mindfulness practice or positive psychology practice (Dykens et al. 2014).

Contributions to Variance in Stress

Our findings indicate that in a group of children referred for an ASD diagnostic evaluation, use of the parent report of autism-associated symptoms (i.e., SRS) may be helpful in the prediction of parenting stress, but clinician-reported severity of ASD symptomatology does not appear to significantly predict stress. The reason for this difference may be that the SRS is also strongly related to non-ASD problem behaviors. Recent research indicates that while the ABC has been labeled and used as a parent-reported index of autism severity in the literature, it may heavily overlap with non-ASD problem behaviors and may not be an indication of the severity of core features of ASD; thus, problem behaviors should be considered when interpreting results from the SRS as an index of autism severity (see Hus et al. 2013).

Problem behavior has consistently been the variable most strongly related to parenting stress in the literature. Our results support that broad assessment of problem behavior as assessed using the CBCL is the single best predictor of parenting stress, accounting for about one-third of the variance in stress. When estimating parenting stress during an ASD evaluation, measures of adaptive skills and parent- and clinician-reported severity of autism-associated symptomatology used in addition to the CBCL do not appear to aid in the prediction of parenting stress. As indicated, there were somewhat discrepant patterns of findings depending on the specific problem behavior measure used. The ABC, which did not significantly predict parenting stress, does not appear to pick up on behaviors relevant for parenting stress as broadly as the CBCL. Furthermore, assessments of daily living skills (consistent with research by Estes et al. 2009) and severity of ASD-associated symptoms did not significantly contribute beyond what could be found using the ABC. The CBCL has been proposed as a useful behavioral measure in screening for children with ASD (Sikora et al. 2008). Thus, based on prior findings and our own results, it seems that the CBCL offers a broad assessment of functioning, and ratings on the CBCL may also be related to rates of parenting stress.

Group Comparisons

In contrast with prior research indicating more problem behaviors in children with ASD compared to other developmental disabilities (Estes et al. 2009) and significantly higher stress in mothers of children with ASD (i.e., Estes et al. 2009; Rodrigue et al. 1990; Schieve et al. 2007; Silva and Schalock 2012), there were no differences in problem behaviors, parenting stress, or total stress between ASD and non-ASD diagnosis groups. However, because all of the children in this study were evaluated due to concerns about an ASD, these results do not necessarily contradict the literature. Differences in our findings regarding problem behavior compared to prior studies may exist partly because all children in our sample were referred specifically for an ASD diagnostic evaluation and may have been exhibiting similar types of problem behaviors in order to warrant a referral. Furthermore, perhaps parental stress when going through an ASD evaluation was relatively stable across the groups in our sample regardless of ultimate ADOS classification. Additionally, prior research and our findings suggest that problem behaviors and parenting stress are highly correlated. Because our groups had similar levels of problem behaviors, it would follow that differences in parenting stress between groups would not be present. Though the non-ASD group exhibited significantly higher cognitive functioning than the ASD group, still, problem behaviors and parenting stress scores were not significantly different.

Clinical Applications

Because child behavior problems appear to account for much of the variance in parenting stress, resources that can help reduce child problem behaviors may help to reduce stress. Clinicians aware of factors influencing parenting stress can equip parents with knowledge about the resources available in the school or community that the child may be able to access based on his or her needs. Education about productive coping strategies can be helpful in decreasing stress and increasing quality of life (Podolski and Nigg 2001). A family-centered approach has been shown (in unpublished work) to help reduce parenting stress for families with a child who has ASD (Everett 2001) and can be suggested for families of children who have had an ASD evaluation. The availability of social support and services is also important in helping parents of children with ASD manage mood (Pottie et al. 2009). Parental coping can be bolstered by training and involvement in interventions designed for children with ASD (McConachie and Diggle 2007). For optimal outcome, it may be important to discuss these strategies and resources with all families regardless of diagnosis, but particularly if the parent reported high stress, and to tailor services to the needs of each child and parent. Parents reporting high levels of child problem behaviors and autism-associated symptoms would likely benefit from a discussion about “next steps” following diagnosis to promote confidence in obtaining services. Parents of children with an ASD diagnosis may find support more readily available in the community and academic setting, while parents of children receiving a non-ASD diagnosis may feel unsure about accommodations and services available for their child as well as support groups for themselves as parents. Clinicians can work with parents to identify supports and barriers, community resources for all family members, and options for therapy in order to act preventatively against stress.

Improvements

Most centrally, in the current study a dimensional approach to addressing ASD-associated symptoms was used through examination of the severity of ASD-associated symptoms in relation to stress. This study extended Estes et al. (2009)’s use of the VABS Daily Living score and ABC, but our study used a different measure of parenting stress (Parenting Stress Index-Short Form). Estes and colleagues measured parenting stress using the Questionnaire on Resources and Stress (QRS: Konstantareas et al. 1992), which demonstrates good concurrent validity with the PSI (Sexton et al. 1992). Standardized tools for the diagnosis of ASD were used, in contrast to the vast majority of prior research (Estes et al. 2009, as a notable exception). In this study two measures of problem behavior were contrasted in the prediction of parenting stress, helping to indicate which measure appears to be most useful in a sample referred for an autism evaluation. These improvements help to detail the degree to which ASD-associated symptom severity and problem behaviors predict parenting stress levels regardless of ASD status.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Conclusion

Limitations included, firstly, the small sample size and the cross-sectional nature of the research. The small sample precluded investigation of interactions between, for example, problem behaviors and ASD-associated symptomatology in the prediction of stress. As expected based on prior literature, parents in this sample reported elevated parenting stress on average, but this results in limited variability in parenting stress for our sample compared to other non-ASD samples (e.g., Estes et al. (2009) Developmental Disorder group). Because participants were referred due to suspicion of a possible ASD, high stress levels across the participants may be due to anticipation of a possible diagnosis of ASD, but stress was not measured after diagnosis to detail changes in stress after the evaluation. Additionally, this study did not include exploration of the wider scope of maternal traits, particularly mental health traits. Underlying maternal characteristics may interact with child traits – behavioral, mental, or emotional – and uniquely affect a parent’s perception of parenting stress. Another limitation, given the low mean ADOS-CS score for this sample, is that limited variability in clinician-rated severity scores may have restricted the ability to fully understand relations between the ADOS-CS score and parenting stress. With regard to diagnosis of ASD, this study was conducted prior to the adoption of DSM-5, so diagnoses were made based on DSM-IV criteria. When comparing groups, the discrepancy in cognitive ability between the ASD and non-ASD groups was a limitation; the sample included families actively seeking an autism evaluation, which restricts clinician control over some characteristics but also offers a study strength in that it resembles what a real-world clinician would likely encounter. Notably, while the SRS and ADOS-CS are both used as severity measures, they are not equivalent in their scope. The SRS has been used in prior research to pick up on severity of social responsiveness deficits typically associated with autism, including social motivation, awareness, and cognition as observed by parents in everyday contexts, while the ADOS focuses more heavily on deficits in social communication within the lab context. Relations between parent-reported symptom severity and parenting stress may in part be due to shared method variance. Finally, it is important to note that the current analyses focused on the Parental Distress scale of the PSI-SF in an attempt to view stress apart from child problem behaviors. Estes et al. (2009) used a summary score for stress, employing a slightly different measure than the current study. Exploratory results using the Total Stress score on the PSI-SF were very similar to results using the Parental Distress scale, but differences from Estes and colleagues’ findings could nevertheless be explained to some extent by the different methods of assessing stress.

Future research should include measures of problem behavior that are not parent-reported (e.g., teacher report) to remove the method variance introduced by using two parent-report measures. Furthermore, consideration of the stress that an autism evaluation places on parents is warranted, as well as tracking of parenting stress over time by following up with the family periodically after the child receives a diagnosis to maintain clinicians’ sensitivity to the possible need for intervention tailored to the child and parent. A diagnosis of ASD could increase stress or, alternatively, it might provide relief with an “answer” and a plan for services in home and academic settings. Similarly, a non-ASD diagnosis may result in relief, but it may increase stress further if a parent is unable to receive services that would have accompanied an ASD diagnosis. Access to and use of resources and services could be monitored to examine whether families are satisfied with the resources available and whether stress is related to access of services. Furthermore, future research may involve interclinical trials targeting behavior problems to investigate effects on parenting stress. Such research may assist in directing parents to both coping resources and accommodations that will suit their child’s individual needs.

From these results we may conclude that parental reports of child problem behaviors and parenting stress are highly related in a sample of children referred because of concerns about a possible ASD. This sample is highly relevant to the referral population a clinician might encounter. With one in 68 children currently meeting criteria for an ASD diagnosis, the population referred for an evaluation because of concerns about a possible ASD includes many more individuals, which emphasizes the relevance of clinician knowledge about potential parenting stress in this parent population. Most centrally, if a parent perceives high levels of problem behaviors or many symptoms that overlap with the autism spectrum, he or she may be at a high risk for parenting stress regardless of whether the child receives a diagnosis of ASD. This knowledge may help clinicians in providing services and recommendations for parents.

References

Abidin, R. A. (1995). Parenting stress index: Short form (PSI-SF) (3rd ed.). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Aman, M. G., & Singh, N. N. (1986). Aberrant behavior checklist (ABC). East Aurora: Slosson.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved 12/17, 2012, from http://www.dsm5.org/about/Pages/faq.aspx#3.

Baker, B. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., Edelbrock, C., & Low, C. (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(4), 217–230. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00484.x.

Bishop, S., Gahagan, S., & Lord, C. (2007). Re-examining the core features of autism: a comparison of autism spectrum disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(11), 1111–1121.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (secondth ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2005). The social responsiveness scale (SRS) manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Dąbrowska, A., & Pisula, E. (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(3), 266–280. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01258.x.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z.

Dyches, T. T., Wilder, L. K., Sudweeks, R. R., Obiakor, F. E., & Algozzine, B. (2004). Multicultural issues in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 211–222.

Dykens, E. M., Fisher, M. H., Taylor, J. L., Lambert, W., & Miodrag, N. (2014). Reducing distress in mothers of children with autism and other disabilities: a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 134(2), 454–463. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3164.

Eisenhower, A. S., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2005). Preschool children with intellectual disability: syndrome specificity, behaviour problems, and maternal well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(9), 657–671. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00699.x.

Estes, A., Munson, J., Dawson, G., Koehler, E., Zhou, X.-H., & Abbott, R. (2009). Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism: The International Journal of Research & Practice, 13(4), 375–387. doi:10.1177/1362361309105658.

Everett, J. R. (2001). The role of child, family and intervention characteristics in predicting stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 62(6-B), 2972.

Gallagher, S., Phillips, A., Drayson, M., & Carroll, D. (2009). Parental caregivers of children with developmental disabilities mount a poor antibody response to pneumococcal vaccination. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(3), 338–346.

Gotham, K., Risi, S., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2007). The autism diagnostic observation schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(4), 613–627. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1.

Gotham, K., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2009). Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 693–705. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3.

Hall, H. R., & Graff, J. C. (2011). The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34(1), 4–25. doi:10.3109/01460862.2011.555270.

Hastings, R. P. (2002). Parental stress and behaviour problems of children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 27(3), 149–160. doi:10.1080/1366825021000008657.

Hepburn, S., Philofsky, A., Fidler, D. J., & Rogers, S. (2008). Autism symptoms in toddlers with Down syndrome: a descriptive study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(1), 48–57. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00368.x.

Hus, V., Bishop, S., Gotham, K., Huerta, M., & Lord, C. (2013). Factors influencing scores on the Social Responsiveness Scale. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(2), 216–224.

Hutton, A., & Caron, S. (2005). Experiences of families with children with autism in rural New England. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(3), 180–189. doi:10.1177/10883576050200030601. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/.

Johnson, N., Frenn, M., Feetham, S., & Simpson, P. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder: parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 29(3), 232–252. doi:10.1037/a0025341.

Johnston, C., Hessl, D., Blasey, C., Eliez, S., Erba, H., Dyer-Friedman, J., & Reiss, A. L. (2003). Factors associated with parenting stress in mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 24(4), 267–275. doi:10.1097/00004703-200308000-00008.

Kaat, A. J., Lecavalier, L., & Aman, M. G. (2014). Validity of the aberrant behavior checklist in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1103–1116.

Klein-Tasman, B., Phillips, K. D., Lord, C., Mervis, C. B., & Gallo, F. J. (2009). Overlap with the autism spectrum in young children with Williams syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(4), 289–299. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ad1f9a.

Konstantareas, M., Homatidis, S., & Plowright, C. (1992). Assessing resources and stress in parents of severely dysfunctional children through the Clarke modification of Holroyd’s Questionnaire on Resources and Stress. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(2), 217–234.

Lecavalier, L., Aman, M. G., Scahill, L., McDougle, C., McCracken, J. T., Vitiello, B., et al. (2006). Validity of the autism diagnostic interview-revised. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111, 199–215.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview-revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., & Risi, S. (1999). Autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS) manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Somer, B. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule manual (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Maxted, A. E., Dickstein, S., Miller-Loncar, C., High, P., Spritz, B., Liu, J., & Lester, B. M. (2005). Infant colic and maternal depression. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(1), 56–68. doi:10.1002/imhj.20035.

McConachie, H., & Diggle, T. (2007). Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13(1), 120–129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00674.x. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/.

Miodrag, N., & Hodapp, R. M. (2010). Chronic stress and health among parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23(5), 407–411.

Mori, K., Ujiie, T., Smith, A., & Howlin, P. (2009). Parental stress associated with caring for children with Asperger’s syndrome or autism. Pediatrics International, 51(3), 364–370. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02728.x.

Mullen, E. M. (1997). Mullen scales of early learning. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Neece, C., & Baker, B. (2008). Predicting maternal parenting stress in middle childhood: the roles of child intellectual status, behaviour problems and social skills. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(12), 1114–1128. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01071.x.

Osborne, L. A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J., & Reed, P. (2008). Parenting stress reduces the effectiveness of early teaching interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 1092–1103.

Podolski, C., & Nigg, J. (2001). Parent stress and coping in relation to child ADHD severity and associated child disruptive behavior problems. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 503–513. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_07. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/.

Pottie, C., Cohen, J., & Ingram, K. (2009). Parenting a child with autism: contextual factors associated with enhanced parental mood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(4), 419–429. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn094. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/.

Rodrigue, J. R., Morgan, S. B., & Geffken, G. (1990). Families of autistic children: psychological functioning of mothers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19(4), 371.

Rutter, M., LeCouteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview revised (WPS Edition Manual ed.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Schieve, L. A., Blumberg, S. J., Rice, C., Visser, S. N., & Boyle, C. (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119, S114–S121. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2089Q.

Sexton, D., Burrell, B., Thompson, B., & Sharpton, W. (1992). Measuring stress in families of children with disabilities. Early Education and Development, 3(1), 60.

Sikora, D. M., Hall, T., Hartley, S., Gerrard-Morris, A., & Cagle, S. (2008). Does parent report of behavior differ across ADOS-G classifications: analysis of scores form the CBCL and GARS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 440–448.

Silva, L. M. T., & Schalock, M. (2012). Autism parenting stress index: initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(4), 566–574. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1274-1.

Singer, G. H. S. (2006). Meta-analysis of comparative studies of depression in mothers of children with and without developmental disabilities. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 111(3), 155–169.

Singer, G. H. S., Ethridge, B. L., & Aldana, S. L. (2007). Primary and secondary effects of parenting stress and stress management interventions for parents of children with developmental disabilities: a meta-analysis. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Review, 13, 357–369.

Sparrow, S., Balla, D., & Cicchetti, D. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales (Interviewth ed.). Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Stevens, J. (1984). Outliers and influential data points in regression analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 95(2), 334–344.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Cleaning up your act: Screening data prior to analysis. Using multivariate statistics (Fifth Edition ed., 72–88). Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

Taylor, J. L., & Warren, Z. E. (2012). Maternal depressive symptoms following autism spectrum diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1411–1418.

Tervo, R. C. (2010). Attention problems and parent-rated behavior and stress in young children at risk for developmental delay. Journal of Child Neurology, 25(11), 1325–1330. doi:10.1177/0883073810362760.

Tervo, R. C. (2012). Developmental and behavior problems predict parenting stress in young children with global delay. Journal of Child Neurology, 27(3), 291–296. doi:10.1177/0883073811418230.

Weiss, J. A., Sullivan, A., & Diamond, T. (2003). Parent stress and adaptive functioning of individuals with developmental disabilities. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 10(1), 129–135.

Weiss, J. A., Cappadocia, M. C., MacMullin, J. A., Viecili, M., & Lunsky, Y. (2012). The impact of child problem behaviors of children with ASD on parent mental health: the mediating role of acceptance and empowerment. Autism: The International Journal of Research & Practice, 16(3), 261–274. doi:10.1177/1362361311422708.

Zaidman-Zait, A., Mirenda, P., Zumbo, B., Wellington, S., Dua, V., & Kalynchuk, K., (2010). An item response theory analysis of the parenting stress index-short form with parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(11), 1269–1277.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from Sigma Xi and a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Graduate School Research Committee Award. The authors would like to thank the participants and their families for their valuable contribution to the research. The authors would also like to thank all research personnel at the Child Neurodevelopment Research Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for their help with data collection, especially Michael Gaffrey, Ph.D.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brei, N.G., Schwarz, G.N. & Klein-Tasman, B.P. Predictors of Parenting Stress in Children Referred for an Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnostic Evaluation. J Dev Phys Disabil 27, 617–635 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-015-9439-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-015-9439-z