Abstract

This study assessed feasibility and psychometric properties of the Hebrew parent version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17), aiming to improve treatment access for children and adolescents with behavioral and mental needs through early screening. The PSC-17 and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) were filled in the waiting room, at three ambulatory clinics in a tertiary pediatric center, by 274 parents using a tablet or their cellphone. Demographic and clinical data were retrieved from patients' files. PSC results were compared to SDQ results and assessed vis-a-vis a psychiatric diagnosis, determined previously and independently by trained pediatric psychiatrists for 78 pediatric patients who attended these clinics. Construct and discriminant validity of the PSC-17 Hebrew version were good. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values are presented. The PSC-17 (Hebrew version) was found to be a feasible tool for mental health screening at pediatric ambulatory care clinics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early detection of mental health concerns among children and adolescents improves lifelong health and development (Costello, 2016), whereas a lack of appropriate treatment could worsen and compound the child's difficulties at home, school, and in community settings (Campion et al., 2012; Dodge & Pettit, 2003).

Pediatricians are well-positioned to identify children under their care who are at risk of developing a mental health problem (Mansbach-Kleinfeld et al., 2011). The long-standing relationship between a pediatrician and the family allows for early identification of emotional issues while considering familial and environmental factors (Parkhurst & Friedland, 2020). Additionally, the pediatrician is usually embedded within the community, understanding its characteristics and challenges. Lastly, pediatricians are less affected by the stigmas associated with mental health professionals; therefore, they may be more accessible. Thus, pediatricians and pediatric services are uniquely positioned to actively assess emotional and behavioral problems presented by their patients.

During the past decade, health care organizations have become increasingly aware of the need for primary care doctors to utilize a well-established and proven screening instrument for identifying possible emotional problems. Initiatives such as the MassHealth Children's Behavioral Health Initiative (Hacker et al., 2017) and D.C. Collaborative for Mental Health in Pediatric Primary Care (Godoy et al., 2017) are two examples. The guiding hand behind these programs has been the American Association of Pediatrics Task Force—Mental Health Recommendations of 2010 (Foy & Perrin, 2010). Recommendations include pre-visit questionnaires, either paper or electronic, filled out at the patient's home or in a waiting room. These questionnaires may incorporate validated instruments to screen for mental health problems, assess psychosocial functioning, and be scored or interpreted before the visit. Such an approach enables the clinician to focus on building a rapport and exploring the findings, rather than only collecting data when systematically obtaining information.

As mentioned above, many programs world-wide address the integration of behavioral health services as part of medical care (Godoy et al., 2017; Hacker et al., 2017). These programs set forth the implementation of a periodic, mandatory screening tool as the first step in achieving the aforementioned integration, to be later followed by in-depth assessment if needed, short-term intervention, or referral, all guided by the screening tool results. It has been argued that screening during childhood and adolescence has unique importance for several reasons. Firstly, several mental health issues present themselves in uncharacteristic ways (such as defiant behavior in depression) and may go undetected or misdiagnosed (Jellinek et al., 2021). Second, early detection of mental health issues during childhood and adolescence may be crucial in preventing further deterioration while addressing important developmental time windows (Glascoe, 2000).

The usefulness and challenges of integrating such a screening system have been the focus of studies in a wide array of medical settings. These include primary care in different communities (Glasner et al., 2021), general hospital care (Rayner et al., 2014), and specialized care such as in gastroenterology clinics (Reed-Knight et al., 2011). Fully understanding the medical setting enables adjustments for screening goals, scope, and constraints. For instance, the patients' general as well as medical background, frequency of visits, and availability of mental health resources are only a few of the vital considerations when designing an appropriate screening system.

One of the most common tools used in children’s medical settings to detect behavioral problems is the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) (Jellinek et al., 1991, 1999; Little et al., 1994), a 35-item questionnaire with both a parent and child self-report version. The questionnaire is also available in a briefer 17-item version (PSC-17), which has suggested to be comparable to the full version (Murphy et al., 2016). The PSC-17 retains the same subscales as the full version: externalizing, internalizing, and attention and concentration (Gardner et al., 2007). While the PSC-35 is a clinically useful screener, the PSC-17 has been widely recommended for pediatric medical settings;it is less time consuming, considering busy healthcare visits, and has been found to show moderate to high sensitivity and specificity, and perform as well as other established measures (Gardner et al., 2007).

In specialist pediatric care, a few studies have demonstrated this questionnaire's usefulness. For instance, high internal consistency for the total score (α = 0.91) and principal component analysis that indicated three distinct factors for the PSC, provided initial support for the utility of the questionnaire in a pediatric gastroenterology clinic (Reed-Knight et al., 2011) The PSC-35 was also employed in a pediatric cardiology clinic. (Struemph et al., 2016). Using the original cutoff points of 28, the authors found similar rates of emotional distress as in healthy populations and questioned whether the PSC was sensitive to the specific difficulties of a pediatric population with cardiological problems. Also, the PSC-17 was employed in a pediatric epilepsy clinic where confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit with the three-factor model and a good total score internal consistency (α = 0.86). 19% of the sample exceeded the cut-off score of 15, more than the sample presented in primary care. Therefore, the authors noted that lower cutoff score should be considered in future studies (Gutiérrez-Colina et al., 2017).

When versions of the PSC were assessed for different languages and in diverse populations different cutoff points than those established for the U.S. general population, 28 for the PSC-35 and 15 for the PSC-17, were recommended (See Table 5). For a example, the Korean version suggested a PSC-35 cutoff point of 14 (Han et al., 2015) and the Dutch version a cutoff point of 22 (Reijneveld et al., 2006). In Austria, the PSC-35 was examined for younger children, age 5 years, and a cutoff point of 20 was recommended (Thun-Hohenstein & Herzog, 2008). In Botswana, the PSC was employed to assess HIV-positive children. For those cases, a PSC-35 cutoff point of 20 and PSC-17 cutoff point of 10, were recommended (Lowenthal et al., 2011). A Turkish version, examining the PSC-17,offered a cutoff point of 12 (Erdogan & Ozturk, 2011). tIn the United States, when the PSC-17 was assessed among a diverse group of chronically ill and non-ill African American and Caucasian children in a pediatric population, it was recommended to lower the cutoff point to 12 (Wagner et al., 2015). A cutoff of 12 was also recommended among low-income Mexican American youth (Jutte et al., 2003). For a detailed overview of previous studies on PSC and suggested cut-off points please see Table 1.

To the best of our knowledge, the PSC has not been studied in the context of a general pediatric hospital, comprised different medical outpatient units. Such a setting will be the focus of our study of the PSC as a screening tool. The translation of both versions of the PSC to different languages, and the administration in different cultures and populations, requires re-calibrating the cutoff point to achieve optimal sensitivity and specificity. Our study sought to explore the administration of the PSC-17, considering two main factors: (1) Medical setting: outpatient clinic in a general pediatric hospital, and (2) Assessing the psychometric properties of the PSC in its Hebrew version. We aimed to establish a uniformed mental health screening tool for the hospital, serving a broad array of children with varied medical problems.

Reaching these goals will allow us to describe and analyze the challenges and obstacles that need to be addressed when implementing a similar assessment system. Our hypotheses were: (a) PSC-17 will be found suitable; (b) PSC-17 will perform well as a screening tool as compared to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and an independently determined psychiatric diagnosis.

Methods

Study Population

Data were collected through a systematic sampling method between November 2019 and December 2020 in the waiting room at three ambulatory clinics in a tertiary pediatric center in Israel: The Diabetes Clinic, Daycare Hospitalization Clinic, and Psychological Medicine Clinic. Parents of children and adolescents who came to these clinics during all working hours Sunday through Thursday were asked to fill in two short questionnaires. This setting was chosen as it resembles conditions under which parents attending a primary care clinic would be asked to fill in the PSC-17.

Parents of children aged 4–17 years were included in the study, while family members other than parents or legal guardians accompanying the child were excluded.

Procedure

A Hebrew version of the questionnaire is available on the PSC official website (Massachusetts General Hospital., 2002), which offers copies of the PSC and its translations. The Hebrew translation has not been systematically validated to the best of our knowledge. Screening for emotional problems was carried out using two screening questionnaires: the PSC-17 and the SDQ. Parents filled in the questionnaires in the waiting room at each clinic. Upon arrival, parents were invited to participate and received a short explanation about the study from a research representative. After signing an informed consent form, they were provided with an electronic device (Tablet, Galaxy, Model Tab A [Samsung, Petach Tikvah, Israel]) and asked to follow instructions provided. A research representative was available to assist with technical issues and other problems. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Schneider Children's Medical Center (0484–19-RMC).

The participants filled out the questionnaires by means of an online platform (REDCap – Research Electronic Data Capture (REDcap, Nashville, U.S.), approved under America's Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) data security protocols, and authorized for use by Clalit Health Services in Israel.

Response Rate

Throughout the study, we rigorously documented all the attendees at each clinic, i.e., the potential participants on a specific day, and reasons for refusal or only partial completion of any questionnaire.

In all, 310 parents of children agreed to participate and filled out at least one questionnaire. Figure 1 presents the characteristics of the participants and reasons for exclusion among non-respondents. The overall refusal rate was 38% (N = 191). The most common reason (n = 102) was being called for a medical procedure before the explanation and consent process was completed and unwillingness to continue afterwards (referred to as 'couldn't reach'). Another frequent reason (n = 68) was an unwillingness to sign the consent form (referred to as 'not interested'). Several participants indicated their reluctance to sign anything or read the lengthy form. Other reasons included participation in another research study in the hospital (and therefore were unwilling to answer more questionnaires) or a language barrier. It should be noted that the non-response rates were higher among those visiting the Daycare Hospitalization Clinic (47%) and the Diabetes Clinic (42%), and lower among those visiting the Mental Health Clinic (9%).

Choosing a Benchmark

As a benchmark or point of reference, we used the (SDQ), a screening instrument validated in Israel in a large community study, that examined 611 adolescents in urban settings. In this study, the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) questionnaire was used as a gold standard to test convergent and discriminant validity. Alpha Cronbach for the total difficulties score was 0.77 (Mansbach-Kleinfeld et al., 2010). Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to estimate the goodness of fit between the SDQ structure and the sample data and results showed reasonable fit to the data (χ2 = 612.413, df = 269, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.047, 90% CI 0.042–0.052). Concurrent validity was assessed against independent psychiatrist’s diagnoses and the total difficulties score showed significantly higher scored when mental disorder was present. Area under the curve for the total difficulties score was found 0.75.

Although the optimal gold standard for a mental health screening tool may be a psychiatric diagnosis, the scope and design of our study, its objectives, and the setting in which the data were collected did not allow for a psychiatric assessment that would provide such a diagnosis. The SDQ was the best choice for a benchmark in our study for several reasons; in general, its Hebrew version has shown acceptable to good internal consistency, and construct, concurrent and discriminant validity. its presentation is very similar to the PSC, and it can be answered in a very short time.

We used the SDQ as a benchmark with caution, since its psychometric validation was carried out in a population of 14- to 17-year-old adolescents, and therefore the norms it presents may not be accurate for younger children. Thus, additionally, along the SDQ score, in this study medical record diagnosis was considered.

Both the SDQ and PSC have corresponding parent and self-reporting versions. This study will only address the psychometric properties of the parent versions.

Measurements

Demographic information included the child's age and gender and parents' marital status. In addition, information was collected regarding the child’s previous diagnoses of physical ailments or mental disorders, and treatment by a mental health professional.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997) This questionnaire assesses behavioral and emotional problems in five areas, four of which indicate levels of difficulties and a fifth that assesses strengths. The five scales are (1) emotional symptoms, (2) behavioral problems, (3) hyperactivity/inattention, (4) peer problems, and (5) pro-social behavior. The questionnaire comprises 25 items, each measured on a 3-point Likert scale (1-not true, 2- somewhat true, 3-certainly true). The internal consistency of the English version of the questionnaire is high (range: 0.80–0.87) (Muris et al., 2003). The Hebrew version was found to be valid and reliable in a representative community sample (Mansbach-Kleinfeld et al., 2010). In our study, the reliability of the SDQ was high (alpha Cronbach 0.82).

The Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 (PSC-17) (Stoppelbein et al., 2012) The PSC questionnaire is designed to assess cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems. The items are rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from "never" (0), "sometimes" (1), to "often" (2). The total score was calculated by adding the scores for each of the 17 items. In the parent version, for children and adolescents aged 6 through 17 years, a cutoff score of 15 or higher indicates psychological impairment, according to norms established for U.S. children and adolescents. For children aged 4 to 5 years in the USA, the PSC cutoff score is 24 or higher (Little et al., 1994). The questionnaire's reliability has been found to be high (0.79-0.92) (Jellinek et al., 1986, 1988; Murphy et al., 2016). The PSC has been translated into Hebrew in 2012 by Carmit Frisch and Professor Sara Rosenblum. Hebrew version is available on the PSC official website (Massachusetts General Hospital., 2002). To the best of our knowledge there hasn’t been psychometric validation of the Hebrew version of the PSC. Therefore, the questionnaire hasn’t been widely used in Israel and we haven’t found studies citing it, to the exclusion of a study examining psychologically treated adolescents during the pandemic, that found the questionnaire to have good reliability (Cronbach alpha = 0.88) (mekori-demochevsky et al.). In our study, Cronbach alpha was found to be 0.92.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Study Population

The study sample included 310 parents; however, 36 did not fully complete both measures (SDQ and PSC-17). Their responses were found to be missing at random (MCAR; Little's MCAR p > 0.05). To address the issue of missing data, the analyses were conducted using two methods, listwise deletion and maximum-likelihood expectation–maximization. The results were mostly identical, and so we report only the results based on listwise deletion (i.e., without missing values). Therefore, the final analysis included 274 parents who completed both the SDQ and the PSC-17. The Mental Health Clinic sample was somewhat smaller (n = 78) than the Diabetes Clinic (n = 96) and Daycare Hospitalization Clinic (n = 100) samples. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of each sample, by clinic. The mean age of children who underwent mental health screening was 11.9 ± 3.7 years. Participants did not differ significantly by type of clinic. The sample included a similar number of boys and girls across the different clinics, parents of most children were married, and mostly (~ 70%) mothers filled the questionnaires in all three clinics.

Psychometric Traits

Structure Validity and Reliability

The first set of analyses was conducted to validate the factor structure of the PSC-17. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit with the 3-factor model (χ2(116) = 261.49, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06; NFI = 0.89; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.92). The factor loadings are presented in Table 3. All loadings were statistically significant, ranging from 0.58 to 0.83 on the principal factor. The measurement model of the study variables was therefore established. The correlations among the disattenuated (free of measurement error) latent variables were positive and significant (internalizing and externalizing: r = 0.64, p < 0.001; internalizing and attention: r = 0.68, p < 0.001; externalizing and attention: r = 0.70, p < 0.001). The internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha indicated high reliability for the total PSC score (0.92) as well as for the internalizing (0.87), externalizing (0.86), and attention problems (0.84) sub-scales. The PSC-17 total scores ranged between 0 to34 and had a mean of 8.06 (SD = 7.23). The sub-scales means were: 2.62 (SD = 2.72) for internalizing, 2.54 (SD = 3.00) for externalizing, and 2.90 (SD = 2.74) for attention problems.

External Validity

Table 4 presents the associations between the PSC and the SDQ. A significant and high correlation was found between the total PSC score and the total SDQ (r = 0.87, p < 0.001). Additionally, PSC-attention had the highest correlation with SDQ-hyperactive (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), PSC-introversion had the highest correlation with SDQ-introversion (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), and PSC-extroversion had the highest correlation with SDQ-extroversion (r = 0.74, p < 0.001). These finding support the external validity of the PSC-17.

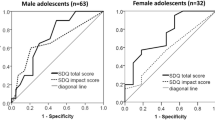

Using SDQ cutoff scores as a criterion, the ROC curve was calculated and is presented in Fig. 1. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.94 and significant (p < 0.001). The recommended cut-off score of the PSC-17 was 9. Considering the diagnosis made by the SDQ as the gold standard, the sensitivity and specificity of the PSC-17 version with a cut-off score of 9 were 89% and 85%, respectively.

When using the score 9 as the cut-off point of the PSC-17, 42% of all participants were identified as in the at-risk group with psychosocial problems; nearly 72% of children attending the Psychological Medicine Clinic were identified, 35% of children attending the Daycare Hospitalization clinic and 25% attending the Diabetes Clinic.

Ecological Validity

To assess the ecological validity of the PSC-17, we calculated the congruence of the score 9 cut-off of the PSC-17 with medical records diagnosis. As shown in Table 5, a significant congruence (χ2 (1) = 42.11, p < 0.001) of 70.1% congruence between the PSC-17 and medical diagnosis was achieved.

Discussion

This study aimed to establish the utility of the Hebrew version of the PSC-17 in an ambulatory setting at a tertiary pediatric hospital. It was performed as an important step in facilitating early detection of mental health problems. The PSC-17 has been previously acknowledged in primary care setting, and in specialized units. To our knowledge, this study was a first attempt of establishing its use as a screening tool in Israel. It was this study's goal to establish the PSC's feasibility and validity with two novel characteristics, in a hospital ambulatory setting, and using a PSC-17 adapted for the Hebrew speaking population.

In our study, the PSC-17 was delivered in three ambulatory clinics in a children's hospital: Diabetes Clinic, Day-Care Clinic, and the Mental Health Clinic, each with its specific population characteristics and needs. Looking at each clinic separately was the focus of previous studies (Reed-Knight et al., 2011; Struemph et al., 2016), yet we sought to establish the PSC-17 as a general screening tool for the hospital to utilize in its ambulatory clinics. Such an attempt was found to be useful in an adult population, using other well-known questionnaires (Rayner et al., 2014). In the aforementioned study, the authors highlighted the importance of mental health screening in a general hospital, as a means to improve medical care.

In our study, the PSC-17 was found to be easy to use and accepted by patients and medical team. It is our view that using a unified screening tool throughout the hospital may serve to improve care and allow for better communication among clinics in the realm of mental health. It may also serve as an outcome measure when assessing the patient over time and as the medical treatment progresses.

The study found that the Hebrew version of the PSC-17, parents' report, has a high reliability, with good to excellent validity. As mentioned earlier, to our knowledge, this is the first study to present the psychometric properties of the PSC-17 in the Hebrew version.

Using confirmatory factor analyses and the SDQ as a benchmark, the PSC-17 and its subscales were found to be valid with very good convergent and discriminant validity.

Sensitivity and specificity are essential measures to consider when exploring a screening questionnaire, especially in a new language and culture. If a screening tool is often erroneous, it may create excess work due to 'false positives' or, conversely, miss important information due to 'false negatives'.

Our study found that the PSC discriminated between 'positive ' and 'negative' cases according to the SDQ and an independent psychiatric diagnosis. A cutoff point of 9 provides better sensitivity and specificity results for our Hebrew-speaking population than the cutoff point of 15 proposed by the American version. Lower cutoff points for the PSC have been previously suggested for different languages such as Turkish (Erdogan & Ozturk, 2011) and Korean (Han et al., 2015), and even different cultures within the same country, such as Mexican-Americans (Jutte et al., 2003), Caucasians, and African American. When comparing Israeli and American population groups, studies have found lower reports of mental health problems among Israeli adolescents than among American adolescents (i.e., 12% vs. 20% of psychiatric disorders, respectively) (Borg et al., 2014). Several studies have described that stigma over mental health problems still loom large in the Israeli society (Farbstein et al., 2010; Tal et al., 2007), and impacts self-reports and help-seeking behaviors. These issues may result in the need to lower the threshold for 'caseness', as was needed in our study.

A cutoff point of 9 identified as true positive cases nearly 72% of children attending the Psychological Medicine Clinic and 35% and 25% attending the Daycare Hospitalizations Clinic and Diabetes Clinic, respectively. The high number of positive cases in the Psychological Medicine Clinic was expected and strengthened the tool's validity. The rates of positive cases in the non-psychological clinics are higher than expected in a community-based clinic (Borg et al., 2014). Yet, this study assessed parents’ responses regarding children who were either chronically ill or facing multiple medical examinations due to undiagnosed symptoms. It has been previously illustrated that children facing chronic medical conditions suffer from more mental health issues than their healthy counterparts (Elroy et al., 2017; Northam et al., 2005). Therefore, the rates found in our study are better understood when considering that this is not a community-based sample but rather a hospital clinic population.

In addition, we would argue that choosing a cutoff score is not merely a statistical decision but depends on the specific setting's needs, goals, and resources. Policymakers may prefer to 'risk' false-positive cases requiring further emotional and behavioral assessment by the pediatrician to reduce the probability of false negatives. The latter may overlook patients, resulting in compounding emotional problems while developmental windows are missed. Despite this argument, further research using other measures as the gold standard are recommended, before making final conclusions about cut-off scores.

A few considerations arose from our study, regarding the implementation and feasibility of the PSC-17 as a screening tool, which may serve as a guideline for future use. These issues include response rate, time constraints, accessibility, and privacy, as described below.

When examining the response rate, the common reason for non-completion was being called upon by the medical staff. This could be avoided in future implementations of pre-visit screening if the medical personal and the administrative team include the psychological screening as one of the forms parents must fill during their visit. We also found higher response rates at the Mental Health Clinic. This may be explained by the congruency between the content of the questionnaire items and purpose of their visit. An important conclusion we derive from this part of the study is the importance of implementing the screening tool as a standard, mandatory component of the clinic visit, supported and encouraged by the medical team. The medical teams' training in addressing the screening results will be essential in the subsequent phases of implementing a screening system.

Duration of the procedure. The measured time for parents to complete the questionnaire ranged between 10 and 15 min for both the SDQ and the PSC-17. When considering the application of the PSC solely, it appears that completion time may be reduced to five minutes. In our study, parents filled out the questionnaire on Tablets while waiting to be called to the doctor, which shows that implementing appropriate technology could enable the medical personnel to review results before the patients' appointment.

Accessibility. We did not encounter parents who required assistance in reading or understanding the questionnaires (concerning language) during the study. The use of digital technology (Tablets) was found to be acceptable, even though paper questionnaires were available upon request. After the COVID-19 virus spread in Israel, the research team addressed hygiene issues by sanitizing the tablets between participants. Most importantly, participants were allowed to complete the questionnaires directly from their personal phones by scanning a Q.R. code with no need for personal details. The latter option was acceptable and comfortable by the participants and might be a time and money-saving opportunity for implementing a pre-visit screening tool.

The short completion time and use of digital technology may help secure patients' cooperation. In addition, it can provide physicians with information that may be explored and elaborated on during the appointment.

Privacy. Completing a questionnaire regarding mental health in an often busy waiting room may not offer the desired level of privacy. Moreover, when a child and parent are asked to complete the screening tool, the research team reported attempts to fill out the scales together. We addressed this issue by asking them to fill out the questionnaires separately. When implementing a pre-visit questionnaire, one needs to consider privacy problems in the specific clinic’s context. As mentioned earlier, using a personal phone may address this issue by providing greater privacy.

A limitation of this study is that it only involved children in an ambulatory setting at a tertiary hospital. Further studies are needed to evaluate the PSC-17 properties among children attending ambulatory primary care and hospitalized. We hope that future studies in outpatient clinics in Israel will allow for a broader and more varied sample, also allowing for additional local languages to be assessed.

As the pandemics' mental health ramifications unfold, the importance of detecting and assisting children and adolescents in need is heightened. Now more than ever, pediatricians need to be aware of, and aid, children with emotional and behavioral concerns, who may require further intervention. Using the PSC-17 as a screening system applicable online and cost-effective, within a medical context is an excellent step in this direction.

Conclusion

These days, considering the implications of the pandemic, the importance of a useful screening tool to detect behavioral and mental health needs is critical. This study assessed the feasibility and psychometric properties of the Hebrew parent-version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17), in three ambulatory clinics at a children’s hospital in Israel. It was performed as an essential step in facilitating pediatricians' early evaluation of children’s behavioral and mental health problems as fundamental components of overall health and wellness. Two hundred seventy-four parents filled questionnaires regarding their children, and demographic and clinical data were retrieved from patients' medical files. The PSC-17 results were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and a psychiatric diagnosis. The study demonstrated that the PSC-17 Hebrew parent version has good psychometric properties. The cutoff point of 9 was lower than the cutoff point in the U.S. version. Variations in cutoff points of other translations and different settings are discussed. This study demonstrated the importance of examining a screening tool in a specific translation, culture and setting (i.e., ambulatory clinics in a hospital). This study is an important step towards increasing awareness and delivering better care for children and adolescents with mental needs in Israel.

Availability of Data and Material

Data will be available for the corresponding author upon demand.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Aitken, M., Martinussen, R., & Tannock, R. (2017). Incremental validity of teacher and parent symptom and impairment ratings when screening for mental health difficulties. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 827–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0188-y

Borg, A. M., Salmelin, R., Kaukonen, P., Joukamaa, M., & Tamminen, T. (2014). Feasibility of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in assessing children’s mental health in primary care: Finnish parents’, teachers’ and public health nurses’ experiences with the SDQ. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 26, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2014.923432

Campion, J., Bhui, K., & Bhugra, D. (2012). European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders. European Psychiatry, 27, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.10.004

Costello, E. J. (2016). Early detection and prevention of mental health problems: Developmental epidemiology and systems of support. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45, 710–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1236728

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.349

Elroy, I., Rosen, B., Samuel, H., & Elmakias, I. (2017). Mental health services in Israel: needs, patterns of utilization and barriers—Survey of the general adult population. Jerusalem, Israel: Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute.

Erdogan, S., & Ozturk, M. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the Turkish version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 for detecting psychosocial problems in low-income children. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 2591–2599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03537.x

Farbstein, I., Mansbach-Kleinfeld, I., Levinson, D., et al. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in Israeli adolescents: Results from a national mental health survey. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip, 51, 630–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02188.x

Foy, J. M., & Perrin, J. (2010). Enhancing pediatric mental health care: Strategies for preparing a community. Pediatrics, 125, S75-86. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0788D

Gardner, W., Lucas, A., Kolko, D. J., & Campo, J. V. (2007). Comparison of the PSC-17 and alternative mental health screens in a[n at-risk primary care sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318032384b

Gardner, W., Murphy, M., Childs, G., et al. (1999). The PSC-17: A brief pediatric symptom checklist with psychosocial problem subscales. A Report from PROS and ASPN, Ambulatory Child Health, 5, 225–236.

Glascoe, F. P. (2000). Early detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatrics in Review, 21, 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.21-8-272

Glasner, J., Baltag, V., & Ambresin, A. E. (2021). Previsit multidomain psychosocial screening tools for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.003

Godoy, L., Long, M., Marschall, D., et al. (2017). Behavioral health integration in health care settings: Lessons learned from a pediatric hospital primary care system. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 24, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9509-8

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip, 38, 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Gutiérrez-Colina, A. M., Lee, J. L., Reed-Knight, B., Hayutin, L., Lewis, J. D., & Blount, R. L. (2017). The Pediatric symptom checklist: Comparison of symptom profiles using three factor structures between pediatric gastroenterology and general pediatric patients. Child Heal Care., 46, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2016.1163493

Hacker, K., Penfold, R., Arsenault, L. N., Zhang, F., Soumerai, S. B., & Wissow, L. S. (2017). The impact of the Massachusetts behavioral health child screening policy on service utilization. Psychiatric Services (washington, d. c.), 68, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500543

Han, D. H., Woo, J., Jeong, J. H., Hwang, S., & Chung, U. S. (2015). The Korean version of the pediatric symptom checklist: Psychometric properties in Korean school-aged children. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 30, 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1167

Jellinek, M., Bergmann, P., Holcomb, J. M., et al. (2021). Recognizing adolescent depression with parent- and youth-report screens in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatrics, 233, 220-226.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.069

Jellinek, M. S., Bishop, S. J., Murphy, J. M., Biederman, J., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (1991). Screening for dysfunction in the children of outpatients at a psychopharmacology clinic. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1031–1036. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.8.1031

Jellinek, M., Murphy, J. M., & Burns, J. (1986). Brief psychosocial screening in outpatient pediatric practice. Journal of Pediatrics, 109, 371–378.

Jellinek, M., Murphy, J. M., Little, M., Pagano, M. E., Comer, D. M., & Kelleher, K. J. (1999). Use of the pediatric symptom checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric care. Arch Pediatr Adole Med, 153, 254–260.

Jellinek, M. S., Murphy, J. M., Robinson, J., Feins, A., Lamb, S., & Fenton, T. (1988). Pediatric symptom checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. Journal of Pediatrics, 112, 201–209.

Jutte, D. P., Burgos, A., Mendoza, F., Ford, C. B., & Huffman, L. C. (2003). Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist in a Low-Income, Mexican American Population. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 157, 1169–1176. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1169

Little, M., Murphy, J. M., Jellinek, M. S., Bishop, S. J., & Arnett, H. L. (1994). Screening 4- and 5-year-old children for psychosocial dysfunction: A preliminary study with the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 15, 191–197.

Lowenthal, E., Lawler, K., Harari, N., et al. (2011). Validation of the pediatric symptom checklist in HIV-infected Batswana. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 23, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2011.594245

Mansbach-Kleinfeld, I., Apter, A., Farbstein, I., Levine, S. Z., & Ponizovsky, A. M. (2010). A population-based psychometric validation study of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire—Hebrew version. Front Psychiatry, 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2010.00151

Mansbach-Kleinfeld, I., Palti, H., Ifrah, A., Levinson, D., & Farbstein, I. (2011). Missed chances: Primary care practitioners’ opportunity to identify, treat and refer adolescents with mental disorders. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 48, 150–156.

Massachusetts General Hospital (2002) Pediatric Symptom Checklist. MGH website. https://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/treatments-and-services/pediatric-symptom-checklist. Accessed 7 Nov 2021.

Mekori-Domachevsky, E., Matalon, N., Mayer, Y., Shiffman, N., Lurie, I., Gothelf, D., & Dekel, I. (2021). Internalizing symptoms impede adolescents’ ability to transition from in-person to online mental health services during the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1357633X211021293.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Van den Berg, F. (2003). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2

Murphy, J. M., Bergmann, P., Chiang, C., et al. (2016). The PSC-17: Subscale scores, reliability, and factor structure in a New National Sample. Pediatrics, 138, e20160038–e20160038. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0038

Northam, E. A., Matthews, L. K., Anderson, P. J., Cameron, F. J., & Werther, G. A. (2005). Psychiatric morbidity and health outcome in Type 1 diabetes—Perspectives from a prospective longitudinal study. Diabetic Medicine, 22, 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01370.x

Parkhurst, J. T., & Friedland, S. (2020). Screening for mental health problems in pediatric primary care. Pediatric Annals, 49, e421–e425. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20200921-01

Rayner, L., Matcham, F., Hutton, J., et al. (2014). Embedding integrated mental health assessment and management in general hospital settings: Feasibility, acceptability and the prevalence of common mental disorder. General Hospital Psychiatry, 36, 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.12.004

Reed-Knight, B., Hayutin, L. G., Lewis, J. D., & Blount, R. L. (2011). Factor structure of the pediatric symptom checklist with a pediatric gastroenterology sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-011-9242-7

Reijneveld, S. A., Vogels, A. G. C., Hoekstra, F., & Crone, M. R. (2006). Use of the pediatric symptom checklist for the detection of psychosocial problems in preventive child healthcare. BMC Public Health, 6, 197. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-197

Stoppelbein, L., Greening, L., Moll, G., Jordan, S., & Suozzi, A. (2012). Factor analyses of the pediatric symptom checklist-17 with African-American and Caucasian pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37, 348–357.

Struemph, K. L., Barhight, L. R., Thacker, D., & Sood, E. (2016). Systematic psychosocial screening in a paediatric cardiology clinic: Clinical utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist 17. Cardiology in the Young, 26, 1130–1136. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951115001900

Tal, A., Roe, D., & Corrigan, P. W. (2007). Mental illness stigma in the Israeli context: Deliberations and suggestions. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 53, 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007082346

Thun-Hohenstein, L., & Herzog, S. (2008). The predictive value of the pediatric symptom checklist in 5-year-old Austrian children. European Journal of Pediatrics, 167(3), 323-329.24.

Wagner, J. L., Guilfoyle, S. M., Rausch, J., & Modi, A. C. (2015). Psychometric validation of the pediatric symptom Checklist-17 in a pediatric population with epilepsy: A methods study. Epilepsy & Behavior, 51, 112–116.

Wood, P. (2008). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The American Statistician, 62, 91–92. https://doi.org/10.1198/tas.2008.s98

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a project geared at promoting children's mental health in Israel, supported by CHAI (Children's Health Alliance for Israel), a non-profit organization aimed at benefiting and contributing to Schneider Children's Medical Center.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors agree with the content and gave explicit consent to submit this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Shachar-Lavie Iris, Mansbach-Kleinfeld Ivonne, Ashkenazi-Hoffnung Liat, Benaroya-Milshtein Noa, Liberman Alon, Segal Hila, Brik Shira and Fennig Silvana declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Approval

The study received ethical approval from Schneider Children's Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Approval nu. 0484–19.

Consent to Participate

All participants signed informed consent as part of the research.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Iris, SL., Ivonne, MK., Liat, AH. et al. Screening for Emotional Problems in Pediatric Hospital Outpatient Clinics: Psychometric Traits of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (Hebrew Version). J Clin Psychol Med Settings 31, 432–443 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-023-09982-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-023-09982-0