Abstract

We put forward a validation of the first instrument to measure the big four health risk behaviours (World Health Organization, Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014, WHO, 2014) in a single assessment, the Health Risk Behaviour Inventory (HRBI) that assesses physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking and alcohol in Italian- and English-speaking samples. Further, we investigate the instrument’s association with self-regulatory dispositions, exploring culture and gender differences in Italian and US subgroup samples. Overall, 304 English- and 939 Italian-speaking participants completed the HRBI and the self-regulatory questionnaire. We explored the factorial structure, convergent validity, invariance and association with self-regulatory dispositions using structural equation modelling.The HRBI has a robust factorial structure; it usefully converges with widely used healthy lifestyle measures, and it is invariant across the categories of age, gender and languages. Regarding self-regulatory dispositions, the promotion focus emerges as the most protective factor over physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking and alcohol, whereas the prevention focus is associated mainly with smoking and alcohol reduction. Results are consistent across genders and US subgroup-Italian samples. The HRBI is a valid instrument for assessing the big four health risk behaviours in clinic and research contexts, and among self-regulatory measures, the promotion and prevention foci have the greatest efficacy in eliciting positive health behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has indicated that physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption are the big four health risk behaviours that are alone responsible for more than two-thirds of chronic diseases (WHO, 2014) and compromise either physical (Forouzanfar et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2020) or mental health (Hiles et al., 2015; Jao et al., 2019). Assessing health risk behaviours is a major paradigm of enquiry in the research and clinical fields, but the majority of instruments usually measure only one health risk behaviour at a time. The response options, metrics and time frames to explore these behaviours differ substantially across various questionnaires, often within the same questionnaire. Furthermore, some instruments have been designed to assess heavy risk behaviours but are inappropriate to measure non-problematic behaviours over a comprehensive range (e.g. AUDIT, Babor & Grant, 1989; Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), Heatherton et al., 1991).

Thus far, very few instruments have explored multiple health risk behaviours through a single standardised assessment (Babor et al., 2004), and to our knowledge, only four are available and salient for the adult population. The Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile (Walker et al., 1987) measures only exercise, nutrition, sleep/stress management and health-promoting perceptions (self-actualisation, personal responsibility and interpersonal support) and excludes alcohol and smoking assessment; the Healthy Lifestyle Screening Tool (Kim & Kang, 2019) assesses sunlight exposure, water consumption, air or ventilation, rest, exercise, nutrition, temperance, trust and physical condition but explores alcohol and smoking with only one question ‘I do not drink alcohol or smoke’. Instead of these self-reporting instruments, some researchers developed an extensive telephone survey, the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (Pierannunzi et al., 2013), which explores a wide variety of risk behaviours but is problematic to use. Finally, Glasgow et al. (2005) developed an instrument derived from a combination of 22 questions extracted from six validated instruments assessing the big four risk behaviours (physical activity using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), Craig et al., 2003; eating patterns using the Starting the Conversation, Paxton et al., 2007; cigarette smoking using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) paradigm, 2003, Hughes et al., 2003; Ory et al., 2002; and alcohol use using the BRFSS, Pierannunzi et al., 2013; CDC, 2003); nonetheless, this instrument is inconsistent with respect to time frame and response options, making it difficult for researchers to compare the different subscales and for respondents to answer the questions, since the response format changes from item to item.

To the best of our knowledge, the only attempt to provide a measure of the big four health behaviours refers to the Health Risk Behaviour Inventory (HRBI) developed in a doctoral dissertation (Irish, 2011). The first version of the HRBI is a self-reporting questionnaire that assesses, through 68 items in a 5-point Likert scale, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, illicit drug use, sleep and risky sexual behaviours in the current month. After having developed the first pilot version, the author then revised the questionnaire format moving away from the Likert scale to multiple-choice responses and validated the latter version in the resultant doctoral thesis, but later has not finalised the validation process in a published peer-reviewed journal. We believe that this instrument has the potential of providing a measure of multiple health risk behaviours in a single assessment, which is otherwise missing in the current literature. To fulfil this aim, the version of the instrument based on a Likert scale is preferable due to the opportunity to rate each statement through a consistent metric. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to refine and implement the HRBI validation.

Some authors underline the importance of having culture-neutral instruments in assessing health risk behaviours (Kim & Kang, 2019), and researchers encourage future studies to explore the cultural framework in lifestyle risk behaviours (King et al., 2015; Singer et al., 2016). Moreover, many studies evidenced gender differences in health risk behaviours (Olfert et al., 2019; Patró-Hernández et al., 2019; Ryu et al., 2020; Westmaas et al., 2002) and argued that gender shapes the adoption of health behaviours and should be considered a determinant of health (Hwang et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2003). Finally, an epidemiological study, including participants from Western and non-Western countries, evidenced different patterns with respect to age in health-risk-taking (Duell et al., 2018); thus, the assessment of health risk behaviour should take culture, age and gender into account.

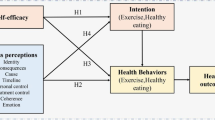

Self-regulatory Dispositions and Health Behaviours

A critical need in health psychology is to identify the psychological determinants of health behaviours (Jeffery et al., 2000). Friese et al., have included two self-regulatory dispositions as salient variables with respect to a risky lifestyle; these are the tendency to push towards positive stimuli and the tendency to run away from potential threats (Friese et al., 2011). However, studies that systematically investigate the association between the big four health behaviours and self-regulatory dispositions, through the various constructs employed in the literature to operationalise them, are missing from the extant literature (Monni et al., 2020). For the present investigation, we consider Elliot’s approach–avoidance temperaments model and Higgins’s promotion and prevention foci model. In particular, Elliot’s approach temperament measures the individual’s predisposition to be extroverted, emotionally positive and more sensitive to rewarding stimuli, whereas the avoidance temperament measures the individual’s predisposition to be neurotic, emotionally negative and more acutely sensitive to punishment stimuli (Elliot & Thrash, 2010). Higgins’s promotion focus measures the tendency to be proactive and liable to attempt to obtain the maximum goal, whereas the prevention focus measures the tendency to be somewhat cautious, guided by a sense of duty and the avoidance of negative consequences (Higgins, 1997). Regarding Elliot’s temperaments theory, we found only one study exploring approach–avoidance temperaments and health risk behaviours; in this study, Dalley (2016) found that the avoidance temperament is associated with a weight loss diet. Several studies examined the relationship between Higgins’s promotion and prevention foci theory (Higgins, 1997) and attendant health risk behaviours. A high prevention focus is associated with more physical activity in individuals with stress burnout (Liang et al., 2013) and a lower probability of relapsing with respect to either smoking (Fuglestad et al., 2008, 2013) or weight loss (Fuglestad et al., 2008), but it is also associated with increased calorie consumption and giving up a diet (Testa & Brown, 2015). The high promotion focus is associated with more physical activity (Joireman et al., 2012; Milfont et al., 2017) and a healthy diet (Joireman et al., 2012) and predicts success in quitting smoking and achieving weight loss (Fuglestad et al., 2008), successfully recovering to again quit smoking after a relapse (Fuglestad et al., 2013) and long-term maintenance of weight loss (Fuglestad et al., 2015). To our knowledge, no current study has investigated the association between self-regulatory dispositions and alcohol consumption. Furthermore, the big four risk behaviours have never been systematically analysed regarding different self-regulatory dispositions within a single investigation, given that most studies only analysed one or two risk behaviours at a time. Due to these inconsistent and incomplete results, further research would appear to be needed.

To fill this gap, we aimed to study possible differences across culture, age and gender in the association between different self-regulatory dispositions and the big four risk behaviours. Only one study found that gender did not differentiate in the association between the high approach trait and more physical activity (Gallagher et al., 2012). However, the authors assessed self-regulatory dispositions through a single question and analysed physical activity only. Although a healthy lifestyle is impacted by different motivations across cultures (Hawks et al., 2003), to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has explored these differences in the association between self-regulatory dispositions and health behaviours. In addition, none analysed age difference effects. Thus, a deeper analysis of self-regulatory dispositions and a wider range of health behaviours are needed to better understand this topic.

The Present Study

To achieve these purposes, our first aim is to contribute to the validation of the HRBI, focussing on the big four problematic lifestyles according to the WHO, refining the questionnaire and analysing the factorial structure in Italian- and English-speaking samples. We also explore HRBI’s convergent validity with well-validated health measures and address the invariance of the factorial structure across age, gender and Italian–English versions.

Our second aim is to explore the association between self-regulatory dispositions and health risk behaviours and investigate the cross-cultural, age and gender differences in this association by comparing the Italian and US subgroup samples.

Method

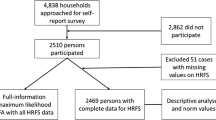

Participants and Procedures

The HRBI questionnaire was administered in different samples and was part of a battery of instruments as described in Table 1. Only Sample 1 completed the HRBI in the classroom at the end of a lesson. The other samples were recruited through internet ads on Facebook groups: university departments groups, workers groups, hobby groups and survey exchange groups. Interested participants completed the questionnaires protocol through a Google Forms worksheet online from August 2019 to February 2020. They provided informed consent before completing the actual questionnaire, and anonymity was guaranteed. We excluded five participants who did not answer the questions on demographic data (ethnicity, city and state where you live, occupation). The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of La Sapienza University of Rome and University of Cagliari.

Measures

The HRBI (HRBI pilot version; Irish, 2011), as mentioned above, investigates seven risky behaviours. In our work, we selected the big four risk behaviours producing a 40-item questionnaire, and then we shortened and refined the instrument through structural equation modelling (SEM). Details of the procedure are described in the Results section. The refined version is composed of 21 items, 5 items for physical activity, four items for an unhealthy diet, six items for alcohol consumption and six items for smoking. Responders are requested to indicate the extent to which the statements are true of their behaviour over the past month using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = Never true to 5 = Always true). For the Italian version, the HRBI questionnaire was translated into Italian by three independent translators, and the final version was back-translated into English by an expert. We calculated the internal reliability of the HRBI through McDonald’s ω index (McDonald, 1970). The omegas for the English version are HRBI physical activity = 0.86, HRBI unhealthy diet = 0.72, HRBI smoking = 0.93 and HRBI alcohol = 0.94. The omegas for the Italian version are HRBI physical activity = 0.88, HRBI unhealthy diet = 0.71, HRBI smoking = 0.95 and HRBI alcohol = 0.91.

The IPAQ short form (Booth, 2000) is composed of seven open questions on moderate–intense physical activity, walking and sedentary time expended in the last week, where higher scores indicate more physical activity. The reliability and validity of the IPAQ short form have been confirmed in 12 countries and for different languages (http://www.ipaq.ki.se/ipaq.htm), and it has been validated in Italian (Mannocci et al., 2012). Cronbach’s alpha for the English version is.66. Cronbach’s alpha for the Italian version is .62 (in line with the Italian validation paper = 0.67, Mannocci et al., 2012).

The Food Habits Questionnaire (Turconi et al., 2003) is composed of 14 items; 8 items’ responses were designed in a 4-point Likert scale (always, often, sometimes, never); the other six items were structured in four response categories that were different for each question. This instrument investigates the number of meals, daily consumption of vegetables and fruits, breakfast content and consumption of alcoholic and soft beverages. Higher scores indicate healthier food habits. Cronbach’s alpha is .62 for the English version, and it is .67 for the Italian version.

The FTND (Fagerström & Schneider, 1989; Italian validation by Lugoboni et al., 2007) is a valid and reliable instrument and is largely used in the literature to measure nicotine dependence. The FTND is composed of six questions on the level of nicotine dependence. To include non-smoker participants, before administering the FTND, we added a preliminary question on smoking: ‘You are’ smoker, occasionally smoker (maximum of three cigarettes per month) and non-smoker. Only ‘smoker’ participants were requested to complete the FTND. Cronbach’s alpha is.70 for the English version, and it is.98 for the Italian version.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test is a self-reporting questionnaire on drinking problems and has been developed by the WHO as a Collaborative Project on the early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption (Saunders et al., 1993). It is composed of 10 items that explore the amount and frequency of drinking, alcohol dependence and the problems associated with alcohol dependence, where a higher score indicates alcohol dependence. The instrument has been validated in Italian (Piccinelli et al., 1997). Cronbach’s alpha for the English version is.89, and the Cronbach’s alpha for the Italian version is .83.

The approach–avoidance temperament questionnaire (Elliot & Thrash, 2010; Italian version Monni & Scalas, 2020a) is a valid and reliable questionnaire composed of 12 items with a 7-point Likert scale and investigates the approach (e.g. ‘I am always on the lookout for positive opportunities and experiences’) and the avoidance temperament (e.g. ‘When it looks as if something bad could happen, I have a strong urge to escape’). The omegas for the English version are approach temperament = 0.84 and avoidance temperament = 0.87. The omegas for the Italian version are approach temperament = 0.84 and avoidance temperament = 0.86.

The Regulatory focus questionnaire (Higgins et al., 2001; Italian version Monni & Scalas, 2020b) is a valid and reliable questionnaire that is composed of 11 items with a 5-point Likert scale and measures the prevention focus (e.g. ‘How often did you obey rule and regulations that were established by your parents’?) and the promotion focus (e.g. ‘Do you often do well at different things that you try’?). The omegas for the English version are promotion focus = 0.72 and prevention focus = 0.85. The omegas for the Italian version are promotion focus = 0.77 and prevention focus = 0.76.

Data Analysis

We employed SEM using Mplus software (version 8.1, Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Since some of the variables associated with risk behaviours such as smoking and drinking alcohol were non-normally distributed, we treated all the variables as non-normally ordered categorical data, and we used Weighted Least Squares Means and Variance as our estimation method (Brown, 2015). That is, instead of calculating the standard score (Z points) of item responses, we used raw ordinal values resulting from the Likert scale data. Researchers are recommended to employ this method given that values of the comparative fit index (CFI) might be underestimated when using standardised scores for non-normally distributed data (Finney & DiStefano, 2006; Urbán et al., 2014).

To assess the model’s adequacy, we referred to the chi-square value (χ2), CFI and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) above 0.90 or. 95 as sufficient or satisfactory fit values and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08 or 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We explored the invariance across languages and genders, and to support the factorial invariance, the difference of CFI and RMSEA between the more and the less restrictive model were compared and they should not exceed a ΔCFI of 0.01 and a ΔRMSEA of 0.015 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Results

First, we calculated means, standard deviations, ranges, skewness and kurtosis for each subscale score. We found appropriate normality for physical inactivity and unhealthy diet, whereas smoking and alcohol consumption were positively skewed and had the lowest mean compared with other subscales for both Italian- and English-speaking respondents (Table 2). These results suggest reduced tobacco and alcohol use among our participants.

HRBI Pre-test

We performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the student sample. The four factors’ structure EFA showed a good fit to the data, χ2(626) = 756.684, p < .05 CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.048, and four factors have been identified (Table 3). Only items with factor loadings higher than.500 were included in the HRBI. Furthermore, we excluded an item with a double statement (HRBI3).

After this procedure, from the original set of 40 items, we selected a set of 21 items divided into four factors: sedentary life (4 items), unhealthy diet (5 items),Footnote 1 smoking (6 items) and alcohol consumption (6 items). The selected items are indicated in bold in Table 3. The refined version of the HRBI was initially tested in Sample 1, a small Italian sample composed of university students (N = 91). We found very good fit indices (χ2(183) = 202.602, p < .05, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.034) and satisfactory factor loadings for all items ranging from 0.400 to 0.967. We reported a significant correlation only between smoking, an unhealthy diet (r = .292, p > .05) and alcohol (r = .509, p < .001) (Table 4).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Invariance over the Italian- and English-Language Versions and over Age and Gender

The factor structure of the HRBI was then tested with the Italian-speaking (Sample 2) and the English-speaking Samples (Sample 3) using confirmatory procedures (confirmatory factor analysis). We registered solid fit indices for both the Italian and the English version of the HRBI (English version χ2(183) = 465.512, p < .05, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.043; Italian version χ2(183) = 465.512, p < .05, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.050) and high factor loadings (Sample 2 range 0.506–0.997; Sample 3 range .400–0.966) (see Table 4). For both samples, we found a positive correlation between an unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, an unhealthy diet and smoking and smoking and alcohol consumption. Notably, enhanced alcohol consumption was correlated with unhealthy diet only in the Italian respondents’ sample and with less physical inactivity in the English respondents’ sample (Table 4).

We explored the invariance of the factorial structure across age, gender and the Italian- and English-language versions of the HRBI. Previous studies revealed group-level changes in identity status at the age of 25 (Eriksson et al., 2020); thus, we transferred the 25-year-old participants to separate early and middle adulthood groups.

Given the uneven number of participants across the samples, using the ‘Select cases’ function in SPSS, we randomly selected an Italian sub-sample composed of an equal number of participants to the English-speaking sample (see Table 1 for the demographic composition of sub-sample 2). We observed that the factorial structure was invariant across age, gender and within the English- and Italian-speaking samples (Table 5).

Convergent Validity with Well-Validated risk Behaviour Questionnaires

We explored the convergent validity between HRBI and the health behaviour questionnaires described above. We tested a latent model with eight correlated latent factors: four factors of the HRBI (HRBIpi, HRBIud, HRBIs, HRBIa) and the four questionnaires’ total scores (the IPAQ, the food habit questionnaire, the Fagerström test and the AUDIT). The models showed a good fit to the data for both the Italian- (χ2(251) = 596.642, p < .05, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.047) and the English-speaking samples (χ2(251) = 422.658, p < .05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.047) and satisfactory factor loadings (> 0.400). The correlation matrix between HRBI and other health behaviour measures can be seen in Table 6. For the Italian-speaking sample (Sample 2) and the English-speaking sample (Sample 3), we reported that high scores on Fagerström (nicotine use) and AUDIT (alcohol consumption) questionnaires strongly correlated with the attendant high HRBI smoking and alcohol scores; high scores on the HRBI for unhealthy diet were negatively associated with healthy food habits measured with FHAB, and the HRBI physical inactivity was negatively related with IPAQT physical activity, especially for the English-speaking sample (Sample 3).

The Association Between Health Risk Behaviours and Self-regulatory Dispositions Considering the Effects of Age, Gender and Culture

As an initial step, we calculated the invariance over age, gender and culture of the general measurement model, and the results are as reported in Table 7. This step is mandatory when researchers are interested in analysing the SEM in different groups. For cultural differences, we selected a subgroup composed only by US participants, and we compared this sample with the Italian Sample 6a (Sample 7). The factorial structure was invariant across the US subgroup vs Italian samples for configural and metric invariance (ΔCFI < 0.01; ΔRMSEA < 0.015), whereas we did not observe scalar invariance (ΔCFI = 0.016). Two items appear to account for this difference: HRB17 ‘I ate breakfast every day’ and ATQ9 ‘When it looks as if something bad could happen, I have a strong urge to escape’. Calculating partial scalar invariance and subsequent levels of invariance, we reported no difference between the US subgroup and Italian samples (Table 7). Regarding gender, we only evidenced a difference of means level invariance (ΔCFI = 0.02 with Variance–Covariance level) (Table 7); thus, males and females showed different factor means; in particular, females reported enhanced HRBI physical inactivity and avoidance temperament and reduced HRBI alcohol consumption compared to the male group. We did not register any difference between the early (< 25) and middle (> 25) adulthood groups. According to Vandenberg & Lance (2000) when the groups are found to be invariant at the Variance–Covariance level of invariance (i.e. ΔCFI < 0.01 and ΔRMSEA < 0.015 between the Variance–Covariance level and residual Variance level), it can be concluded that the betas in an SEM model are invariant across groups. In light of this, we could state that the US subgroup and Italian samples, early–middle adulthood participants and male–female would show the same association between self-regulatory dispositions and health risk behaviours.

Therefore, we calculated an SEM model on the aggregated US subgroup and Italian samples (Sample 7) in which self-regulatory dispositions would predict health risk behaviours. The model showed an acceptable fit to the data χ2(874) = 1809.220, p < .05, CFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.046. Results showed that individuals with a high promotion focus are less prone to have a sedentary life, follow an unhealthy diet or smoke or drink alcohol, whereas individuals with a high prevention focus are less prone only to smoke or drink alcohol but more prone to physical inactivity. In line with results for the prevention focus, an avoidance temperament protects from smoking, whereas an approach temperament does not appear to influence any risk behaviour (Table 7).

Discussion

Assessing health risk behaviours has important relevance in clinical and research contexts. The aim of the current study was twofold: first, to provide the first validation of the HRBI in a sample of Italian- and English-speaking respondents, analysing the factorial structure, the convergent validity and the invariance across age, gender and the English–Italian versions; second, to investigate the association between self-regulatory dispositions and health risk behaviours exploring cross-cultural, age and gender differences in the Italian subgroup and the US subgroup samples.

We observed that the HRBI has a robust factorial structure and is invariant across age, gender and the Italian–English-speaking samples. We highlighted the convergent validity of the specific HRBI scales with commonly used healthy lifestyle assessments, particularly with Fagerström (nicotine use), AUDIT (alcohol consumption) and FHAB (healthy food habits) tests that showed high correlations, whereas only a medium correlation was found with IPAQT (physical activity).

From the SEM analysis, it emerged that individuals with a high promotion focus are less prone to have a sedentary life, follow an unhealthy diet or smoke or drink alcohol. Individuals with high prevention focus or avoidance temperament showed less smoking or alcohol use, but a high prevention focus also induces a sedentary life. Our results confirmed the evidence of a positive association between a promotion focus and physical activity (Joireman et al., 2012; Milfont et al., 2017) and a healthy diet (Joireman et al., 2012). Moreover, the effect of a promotion focus on smoking and a healthy diet is in line with Fuglestad et al.’ results in which promotion focus has a positive effect on weight loss and quitting smoking (Fuglestad et al., 2013, 2015, 2008) and a prevention focus has a positive effect on refraining from smoking (Fuglestad et al., 2008, 2013). Conversely, we did not replicate the results of Testa & Brown (2015) showing an association between an unhealthy diet and a prevention focus, which in our sample appear to be unrelated. In addition, whereas Liang et al. recorded an association between a prevention focus and more physical activity (Liang et al., 2003), we found the opposite effect. However, they found this association among ‘stressed’ participants, whereas in our study, we did not control for the effect of stress. In addition, we did not replicate Dalley’s findings (2016) in which an avoidance temperament was associated with a weight loss diet. For the first time, we reported results on promotion and prevention focus and alcohol.

Regarding our second aim, we explored age, gender and cultural differences. Confirming Gallagher et al.’ results (2012), we found an association between an approach motivation and enhanced physical activity that was similar across gender, and we specified that the enhanced physical activity is associated with a promotion focus and not an approach temperament. In addition, for the first time, we showed that the association between health behaviours and self-regulatory dispositions is similar for both the US subgroup and Italian samples and early and middle adulthood participants. With these results, we provided additional confirmatory empirical evidence for Friese and colleagues’ model (Friese et al., 2011) in which the approach–avoidance traits are considered psychological determinants that favour health behaviours. We further showed that this association is consistent across age, gender and US subgroup and Italian subgroup samples.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, the HRBI is the first questionnaire that analyses the big four health behaviours (as identified by the WHO) using a unique multidimensional instrument. We proposed an initial validation of the HRBI measure testing its construct validity and invariance across age, culture and gender. In addition, we systematically addressed the relationships between self-regulatory dispositions and risk behaviour comparing age, culture and gender effects.

Although promising, our study is not without limitations. First, we did not explore the test–retest reliability, and we did not recruit a sample that also included frequent alcohol and smoker users; therefore, it would be useful for future studies to analyse test–retest reliability and to explore this questionnaire by engaging with a more representative sample for drinking and smoking habits. Second, it is important to emphasise that the male group of the English-speaking sample was composed of a limited number of individuals (N = 85); therefore, our results should be considered a preliminary test of invariance over gender in an English-speaking respondent sample. Finally, it would be interesting also to analyse the self-regulatory dispositions and health habits association through a longitudinal study involving a large sample of participants to explore the longitudinal effect of self-regulatory dispositions on the engagement in health behaviour over the lifetime, including adolescents and elderly participants. Future research is called for to fill these gaps and, hopefully, to explore this field of research even further.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

This procedure has led to measuring eating behaviour only through healthy items (selecting low-fat foods or consuming fruit and vegetables) and excludes items that are considered as unhealthy diet behaviour (e.g. consumption of salt and sugar). This technique could raise doubts regarding the content validity of this scale, given that we could not measure the entirety of the construct. However, also in the original version of the instrument, several concerns arose regarding these items measuring unhealthy behaviours (Irish, 2011). In particular, Irish (2011) argued that participants disagreed about the meaning of ‘fast food’, with definitions ranging from ‘anywhere with a drive-thru’ to ‘any restaurant’. Additionally, when she explored what participants considered to be ‘packaged/convenience foods’, responses varied widely, including foods such as frozen dinners, condensed soup and frozen vegetables or crackers. In response to the question about ‘fried food’, one US participant accurately observed that fried foods could refer to foods cooked in a frying pan as well as foods cooked by deep-frying, which represent different health risks.

In our Italian sample, restaurant and fast foods have different meanings, and Italian participants are less prone to visit fast food outlets (M = 1.14, SD = .504, kurtosis = 37.53). Packaged foods are consumed less in Italy than in the US, and Italians consider frozen dinners as examples of packaged food. Some Italian participants pointed out that a cup of espresso could be considered a sugar-sweetened beverage, and many Italians drink more than two espressos per day, which does not have the same caloric intake as a coke. Finally, some items were poorly phrased (‘I added extra salt to my food’—extra with respect to what?), and others could be influenced by different cultural habits (‘I ate sweets more than once per day’). In Italy, it is common to have a sweet breakfast with cookies, cakes and other sweets; conversely, other nations prefer a savoury breakfast. The difference in these definitions makes the items that we decided to drop inconsistent between participants, as they represent different levels of health risk. Thus, we preferred to exclude those items from the reduced version to have a group of items with a more unequivocal meaning across cultures to allow comparability across nations.

References

Babor, T. F., & Grant, M. (1989). From clinical research to secondary prevention: International collaboration in the development of the alcohol disorders identification test (AUDIT). Alcohol Health and Research World, 13, 371–374.

Babor, T. F., Sciamanna, C. N., & Pronk, N. P. (2004). Assessing multiple risk behaviors in primary care: Screening issues and related concepts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(2), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.018

Booth, M. L. (2000). Assessment of physical activity: An international perspective. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(2), S114–S212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.200.11082794

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSSQuest/index.asp

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjöström, M., Bauman, A. E., Booth, M. L., Ainsworth, B. E., Pratt, M., Ekelund, U. L., Yngve, A., Sallis, J. F., & Oja, P. (2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35, 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Dalley, S. E. (2016). Does the salience of possible selves mediate the impact of approach and avoidance temperaments on women’s weight-loss dieting? Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 267–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.010

Duell, N., Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Chein, J., Chaudhary, N., Di Giunta, L., Kenneth, A. D., Kostas, A. F., Jennifer, E. L., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Tapanya, S., Tirado, L. M. U., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S. M., Takash, H. M. S., Bacchini, D., & Chang, L. (2018). Age patterns in risk taking across the world. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1052–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0752-y

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2010). Approach and avoidance temperament as basic dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality, 78(3), 865–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.201.00636.x

Eriksson, P. L., Wängqvist, M., Carlsson, J., & Frisén, A. (2020). Identity development in early adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 56(10), 1968–1983. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001093

Fagerstrom, K. O., & Schneider, N. G. (1989). Measuring nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12, 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00846549

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 10, 269–314.

Forouzanfar, M. H., Afshin, A., Alexander, L. T., Anderson, H. R., Bhutta, Z. A., Biryukov, S., Brauer, M., Burnett, R., Casey, D., Coates, M. M., Cohen, A., Delwiche, K., Estep, K., Frostad, J. J., Astha, K. C., Kyu, H. H., Morad-Lakeh, M., Marie, N. G., Slepak, E. L., … Carrero, J. J. (2016). Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet, 388, 1659–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2

Friese, M., Hofmann, W., & Wiers, R. W. (2011). On taming horses and strengthening riders: Recent developments in research on interventions to improve self-control in health behaviors. Self and Identity, 10, 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.201.536417

Fuglestad, P. T., Rothman, A. J., & Jeffery, R. W. (2008). Getting there and hanging on: The effect of regulatory focus on performance in smoking and weight loss interventions. Health Psychology, 27, 260–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.3(Suppl.).S260

Fuglestad, P. T., Rothman, A. J., & Jeffery, R. W. (2013). The effects of regulatory focus on responding to and avoiding slips in a longitudinal study of smoking cessation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35, 426–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.823619

Fuglestad, P. T., Rothman, A. J., Jeffery, R. W., & Sherwood, N. E. (2015). Regulatory focus, proximity to goal weight, and weight loss maintenance. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39, 709–772. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.5.12

Gallagher, P., Yancy, W. S., Jr., Swartout, K., Denissen, J. J., Kühnel, A., & Voils, C. I. (2012). Age and sex differences in prospective effects of health goals and motivations on daily leisure-time physical activity. Preventive Medicine, 55, 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.017

Glasgow, R. E., Ory, M. G., Klesges, L. M., Cifuentes, M., Fernald, D. H., & Green, L. A. (2005). Practical and relevant self-report measures of patient health behaviors for primary care research. The Annals of Family Medicine, 3, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.261

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., & Fagerstrom, K. O. (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86, 1119–1127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N., & Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.27

Hiles, S. A., Baker, A. L., de Malmanche, T., McEvoy, M., Boyle, M., & Attia, J. (2015). Unhealthy lifestyle may increase later depression via inflammation in older women but not men. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 63, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.010

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hughes, J. R., Keely, J. P., Niaura, R. S., Ossip-Klein, D. J., Richmond, R. L., & Swan, G. E. (2003). Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 5, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/5.1.13

Hwang, M., Zhang, H. S., & Park, B. (2019). Association between health behaviors and family history of cancer according to sex in the general population. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.1.017

Jao, N. C., Robinson, L. D., Kelly, P. J., Ciecierski, C. C., & Hitsman, B. (2019). Unhealthy behavior clustering and mental health status in United States college students. Journal of American College Health, 67, 790–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1515744

Jeffery, R. W., Epstein, L. H., Wilson, G. T., Drewnowski, A., Stunkard, A. J., & Wing, R. R. (2000). Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychology, 19, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.Suppl1.5

Joireman, J., Shaffer, M. J., Balliet, D., & Strathman, A. (2012). Promotion orientation explains why future-oriented people exercise and eat healthy: Evidence from the two-factor consideration of future consequences-14 scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1272–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212449362

Kim, C. H., & Kang, K. A. (2019). The validity and reliability of the healthy lifestyle screening tool. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science, 8, 99–11. https://doi.org/10.14474/ptrs.2019.8.2.99

King, K., Meader, N., Wright, K., Graham, H., Power, C., Petticrew, M., & Sowden, A. J. (2015). Characteristics of interventions targeting multiple lifestyle risk behaviours in adult populations: A systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE, 10, e0117015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117015

Liang, J., Bennett, J. M., Sugisawa, H., Kobayashi, E., & Fukaya, T. (2003). Gender differences in old age mortality: Roles of health behavior and baseline health status. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56, 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00060-X

Liang, H. L., Kao, Y. T., & Lin, C. C. (2013). Moderating effect of regulatory focus on burnout and exercise behavior. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 117, 696–708. https://doi.org/10.2466/06.29.PMS.117x29z0

Lugoboni, F., Quaglio, G., Pajusco, B., Mezzelani, P., & Lechi, A. (2007). Association between depressive mood and cigarette smoking in a large Italian sample of smokers intending to quit: Implications for treatment. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 2, 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-007-0057-3

Mannocci, A., Di Thiene, D., Del Cimmuto, A., Masala, D., Boccia, A., De Vito, E., & La Torre, G. (2012). International physical activity questionnaire: Validation and assessment in an Italian sample. Italian Journal of Public Health, 7, 369–376.

McDonald, R. P. (1970). The theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 23, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.197.tb00432.x

Milfont, T. L., Vilar, R., Araujo, R. C., & Stanley, R. (2017). Does promotion orientation help explain why future-orientated people exercise and eat healthy? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01202

Monni, A., & Scalas, L. F. (2020a). Italian validation of the approach-avoidance temperament questionnaire. BPA-Applied Psychology Bulletin (bollettino Di Psicologia Applicata), 67(284), 20–23.

Monni, A., & Scalas, L. F. (2020b). Contributo alla validazione della versione italiana del Regulatory Focus Questionnaire di Higgins: A contribution to the Italian validation of the Higgins’ regulatory focus questionnaire. Ricerche Di Psicologia, 2, 469–499. https://doi.org/10.3280/RIP2020-002003

Monni, A., Olivier, E., Morin, A. J. S., Belardinelli, M. O., Mulvihill, K., & Scalas, L. F. (2020). Approach and avoidance in Gray’s, Higgins’, and Elliot’s perspectives: A theoretical comparison and integration of approach-avoidance in motivated behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.202.110163

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2017). Mplus (pp. 507-518). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Ng, R., Sutradhar, R., Yao, Z., Wodchis, W. P., & Rosella, L. C. (2020). Smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity—modifiable lifestyle risk factors and their associations with age to first chronic disease. International Journal of Epidemiology, 49, 113–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz078

Olfert, M. D., Barr, M. L., Charlier, C. C., Greene, G. W., Zhou, W., & Colby, S. E. (2019). Sex differences in lifestyle behaviors among US college freshmen. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030482

Ory, M. G., Jordan, P. J., & Bazzarre, T. (2002). The behavior change consortium: Setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Education Research, 17, 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.5.500

Patró-Hernández, R. M., Nieto Robles, Y., & Limiñana-Gras, R. M. (2019). The relationship between gender norms and alcohol consumption: A systematic review. Adicciones. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1195

Paxton, A. E., Ammerman, A. S., Gizlice, Z., Johnston, L. F., & Keyserling, T. C. (2007). Validation of a very brief diet assessment tool designed to guide counseling for chronic disease prevention. Presented at the International Society of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.

Piccinelli, M., Tessari, E., Bortolomasi, M., Piasere, O., Semenzin, M., Garzotto, N., & Tansella, M. (1997). Efficacy of the alcohol use disorders identification test as a screening tool for hazardous alcohol intake and related disorders in primary care: A validity study. BMJ, 314, 42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7078.420

Pierannunzi, C., Hu, S. S., & Balluz, L. (2013). A systematic review of publications assessing reliability and validity of the behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-49

Ryu, H., Moon, J., & Jung, J. (2020). Sex differences in cardiovascular disease risk by socioeconomic status (SES) of workers using national health information database. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062047

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Singer, M. K., Dressler, W., George, S., NIH Expert Panel. (2016). Culture: The missing link in health research. Social Science & Medicine, 170, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.015

Testa, R. J., & Brown, R. T. (2015). Self-regulatory theory and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 22, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-015-9421-z

Turconi, G., Celsa, M., Rezzani, C., Biino, G., Sartirana, M. A., & Roggi, C. (2003). Reliability of a dietary questionnaire on food habits, eating behaviour and nutritional knowledge of adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57, 753–763. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601607

Urbán, R., Kun, B., Farkas, J., Paksi, B., Kökönyei, G., Unoka, Z., Felvinczi, K., Oláh, A., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Bifactor structural model of symptom checklists: SCL-90-R and brief symptom inventory (BSI) in a non-clinical community sample. Psychiatry Research, 216, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.027

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002

Walker, S. N., Sechrist, K. R., & Pender, N. J. (1987). The health-promoting lifestyle profile: Development and psychometric characteristics. Nursing Research. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198703000-00002

Westmaas, J. L., Wild, T. C., & Ferrence, R. (2002). Effects of gender in social control of smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 21, 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.4.368

World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. WHO.

Irish, L. A. (2011). Development, reliability and validity of the health risk behaviors inventory: a self-report measure of 7 current health risk behaviors (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University).

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM Conceptualisation, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; LFS project administration, supervision, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Alessandra Monni, and L. Francesca Scalas have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of La Sapienza University of Rome and University of Cagliari.

Informed Consent

All participants completed informed consent before participation.

Human and animal rights

This study have been approved by the Ethics Committees of La Sapienza University of Rome and University of Cagliari and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monni, A., Scalas, L.F. Health Risk Behaviour Inventory Validation and its Association with Self-regulatory Dispositions. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 29, 861–874 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09854-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09854-z