Abstract

Anxiety is one of the most common co-occurring diagnoses in youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based treatment that has been tailored for youth with ASD and anxiety and has shown good efficacy in reducing youth anxiety immediately after treatment. One area that has not been widely studied is acceptability of CBT for anxiety in this population. Acceptability includes beliefs about the potential helpfulness and satisfaction with a given treatment and may be important in understanding treatment outcomes. This study focuses on parent, youth, and clinician acceptability of a well-researched CBT program, Facing Your Fears, for youth with ASD and anxiety. Data was collected as part of a larger multi-site study that compared three different instructional conditions for clinicians learning the intervention. Results indicated that parents rated acceptability as higher for the overall treatment compared to youth. Further, youth and parents rated exposure related sessions as more acceptable than psychoeducation, and higher exposure acceptability ratings were predictive of lower youth anxiety levels post-treatment. Clinicians who received ongoing consultation rated treatment acceptability lower than clinicians in the other training conditions. While some clinicians may be hesitant to implement exposure techniques with this population, findings suggest that it is the technique that parents and youth rated as the most acceptable. Results are discussed in terms of treatment and research implications for youth with ASD and their families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a pervasive developmental disorder that persists throughout the lifespan and is often accompanied by other challenges such as behavior difficulties, medical issues, and additional mental health diagnoses (de Bruin et al. 2007). In particular, anxiety disorders are the most common co-morbid mental health condition in this population with about 40% of youth with ASD meeting criteria for an anxiety disorder (e.g., specific phobia, social anxiety) at some point in time (van Steensel et al. 2011).

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is considered the gold standard of treatment for youth with anxiety disorders (Walkup et al. 2008) and more recently, CBT has been modified for youth with ASD and has shown similar successes in reductions of anxiety symptoms (Reaven et al. 2012). The majority of these treatments include the core components of CBT for anxiety (e.g., psychoeducation including attention to negative thoughts and management of physical symptoms of anxiety, as well as graded exposure—or facing fears in a step-by-step manner) (see Kendall 1994; Reaven et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2009).

To date, researchers have focused on tailoring CBT treatments for youth with ASD and anxiety, and while there is now a better understanding of treatment effectiveness, little is known about the acceptability of this approach for anxiety in this population. Research has also not yet examined the associations between participant and clinician ratings of acceptability and treatment outcomes. The concept of treatment acceptability was pioneered by Kazdin (1980) and his definition specified that acceptability referred to “the degree to which a treatment is viewed as fair, reasonable, appropriate, and/or un-intrusive” (O’Brien and Karsh 1991). Researchers have since expanded the definition to include beliefs about the potential effectiveness of the treatment, suitability and likeability of the treatment, satisfaction with the treatment, and importance or relevance of the treatment (Calvert and Johnston 1990; Miltenberger 1990; Reimers et al. 1992). Treatment acceptability is typically measured through a questionnaire format where participants rate items on a Likert-type scale (Finn and Sladeczek 2001). Researchers can then tally overall acceptability mean scores. The present study focused on measuring parents’, youth, and clinician ratings of acceptability using the broader definition as noted above.

Overall, parent and youth ratings of treatment acceptability have been associated with increased treatment effectiveness (Kazdin 2000) and decreased program drop out (Wergeland et al. 2015). In the CBT literature, treatment acceptability has also been shown to be related to therapeutic change in youth (Kazdin 2000). In one study examining youth with ADHD, participants were asked to rate the extent to which the treatment procedures were appropriate, reasonable, and enjoyable (Kazdin et al. 1989). Items asked how much parents and youth looked forward to coming to sessions and how much they found the sessions to be interesting and fun. Results indicated that youth with ADHD who rated behavioral treatment as more acceptable were more likely to show improvements post treatment. Failure to complete treatment may also occur when families rate an intervention as low in acceptability (Taylor et al. 2012). In a study exploring predictors of dropout from CBT for youth with anxiety, results indicated that both parents and youth who perceived CBT as less credible or relevant (components of acceptability) were more likely to drop-out of treatment (Wergeland et al. 2015).

Gaining a better understanding of how parents, youth, and clinicians view the acceptability of a CBT treatment for youth with ASD and anxiety is important. Eliciting feedback from participants about acceptability can inform new treatments, which, may in turn, improve the use and delivery of intervention programs. Further, treatments that are considered to be highly acceptable are more likely to be sought after and clients may be less likely to drop out of such treatments. Quality of treatment delivery as well as treatment integrity may also improve when clinicians find a treatment acceptable (Allinder and Oats 1997).

Furthermore, one particular component of CBT for anxiety has been discussed in the literature as a potential predictor of drop-out from treatment. Specifically, exposure practice (facing fears), which is a well-established key ingredient in CBT intervention (Kaczkurkin and Foa 2015), may trigger avoidance or resistance from treatment participants (Kendall et al. 2009). In fact, exposures may be the “least acceptable” part of treatment for many clients, potentially contributing to treatment refusal and drop-out rates (Abramowitz et al. 2002). Thus, it is important to expand on the relation between acceptability and treatment completion, by exploring the relationship between treatment acceptability and treatment outcome. Specifically, treatment acceptability (particularly low ratings) may help explain why some individuals do not respond positively to intervention.

While researchers have previously examined parent and youth ratings of acceptability, clinicians’ beliefs about acceptability of anxiety treatment have not been documented. Clinicians’ beliefs about a treatment may impact the quality of treatment delivery as well as the likelihood that clinicians will continue to deliver the intervention in the future. Therefore, it is also important to understand clinicians’ beliefs about the acceptability of an evidenced based treatment for youth with anxiety and ASD.

Current Study

The present study is part of a larger, multi-site study designed to determine the optimal training model necessary for clinicians new to a group CBT intervention (Facing Your Fears: Group Therapy for Managing Anxiety in Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders; FYF; Reaven et al. 2011). Clinicians were assigned to one of three instructional conditions: (1) manual only (Manual); (2) manual plus two-day workshop (Workshop); and (3) manual plus 2-day workshop, plus bi-weekly supervised consultation (Workshop-Plus) (Reaven et al., in press) and then delivered the intervention to youth with ASD and anxiety. The overall goal of the larger project included comparing instructional conditions on measures of intervention fidelity and youth treatment outcome.

The current study has several primary aims. The initial aim was to examine acceptability ratings for parents and youth completing the Facing Your Fears (FYF) intervention (Reaven et al. 2011) and determine whether there were differences between parent and youth acceptability. A sub-aim included examining parent and youth acceptability rating differences across two treatment blocks: psychoeducation and exposure. A second aim was to examine clinician ratings of acceptability and whether there were differences in ratings across instructional conditions (i.e., Manual, Workshop, Workshop-Plus). A final aim was to examine the association between participants’ treatment acceptability and youth anxiety post treatment.

In previous studies on FYF, parent and youth acceptability ratings have been high; however, these studies have not examined differences in ratings by informant or between the different blocks of treatment (i.e., psychoeducation and exposure) (Reaven et al. 2014). Based on our previous work examining acceptability of FYF, it was hypothesized that overall acceptability of the FYF treatment will be high for both parents and youth; however, parents will rate the overall treatment as more acceptable than youth. Additionally, it was hypothesized that parents and youth will rate psychoeducation sessions as more acceptable than exposure, given the challenges participants experience when facing fears. It was also anticipated that acceptability will be higher for clinicians in the Workshop-Plus condition, since these clinicians received more in depth training and supervision over time, and would likely feel most comfortable with the intervention. Finally, because previous research has suggested that treatment acceptability may be related to improved youth outcomes, it was hypothesized that higher ratings of acceptability for participants will be associated with greater improvements in youth treatment outcome.

Methods

Participants

As noted above, this study was part of a larger, multi-site study comparing instructional methods for delivery of FYF in outpatient clinics. Participants in the present study included youth and their parents as well as clinicians new to FYF. Children were between the ages of 8–14 years old and had diagnoses of ASD and anxiety. All youth who participated in the study did so with at least one parent. Participants were recruited from four settings. All sites were University-affiliated outpatient clinics and were considered regional leaders in the assessment and treatment of ASD.

Each site recruited participants with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved announcements, practitioner referrals, and via word of mouth. Informed consent and assent was obtained for all participants at each study site, prior to collecting data. For extensive detail on the methods used for the broader multi-site study, please refer to Reaven et al. (in press). Methods relevant to the current research questions, including sample and procedures, are specifically described here.

Clinicians (n = 34)

Graduate students or professionals in mental health related disciplines (e.g., clinical psychology, counseling psychology, social work) participated in the study across the four sites. The majority of the clinicians were female (94%) and Caucasian (88%). 41% held a doctorate degree in psychology (n = 14), while 53% had a terminal master’s degree (n = 18), and 6% held a Bachelor’s degree with some graduate training (n = 2; e.g., Master’s or doctoral degree graduate students, interns). On average, the clinicians had 3.4 years (range 0–12 years) experience using CBT strategies, but were more experienced in working with youth with ASD (M = 7.6 years of experience; range 0–34 years). Clinicians were designated as “parent clinicians” if they had a primary role in the parent portion of the treatment sessions, and “youth clinicians” if they had a primary role in the youth portion of the sessions.

Youth and Family Participants (n = 80 parent/youth Dyads)

This was a sample of treatment completers of youth between the ages of 8 and 14 years with a participating parent. 91 participants began the treatment, but seven participants dropped out of treatment before completion and therefore were not included in the present sample. The remaining four participants did not complete follow-up data and were not included in the current sample. As only 11 participants were excluded, potential differences between completers and non-completers could not be analyzed. There were no pre-treatment differences across training conditions (Manual, Workshop, Workshop Plus) on variables such as youth and caregiver age, gender, pre-treatment anxiety symptoms, or ethnicity.

All youth in the present study qualified for participation in the large multi-site study (see Reaven et al., in press). They all had a diagnosis of ASD [confirmed by a score above the spectrum cutoff on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012) and the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Berument et al. 1999)], had an estimated Verbal IQ of 80 or above, were able to read at a second-grade reading level (or above), and had clinically significant symptoms of anxiety (confirmed by scores above the clinical cutoff on the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED—parent version, Birmaher et al. 1999) and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Parent (ADIS-P; Silverman and Albano 1996)). Exclusion criteria included: (a) families who were non-English speaking; (b) families were not able to commit to at least 11 of 14 sessions; (c) youth presenting with psychosis, severe aggressive behavior, or other severe psychiatric symptoms that potentially required more intensive treatment; (d) families intending to pursue additional psychological intervention targeting anxiety symptoms during the 4 month study period; and (e) youth who were not able to separate from parents for at least 30 min. Psychosocial information was also collected from parents. There were 80 parents that participated across sites. See Table 1 for youth, parent, and family characteristics.

Procedure

This study was completed in compliance with the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus) and the IRB of each of the study sites. Following recruitment and screening for eligibility, parents and youth consented/assented to the study and entered the next available treatment group. The study consisted of a 3-group parallel design where nine teams (cohorts) of three clinicians were randomized via a Latin-square procedure to receive one of three instructional conditions: (1) Manual, (2) Workshop, (3) Workshop-Plus (see descriptions below). Each site was assigned to an instructional condition for a full year and the same clinician team was required to deliver treatment for the duration of the year.

Instructional Conditions

The three instructional conditions were: (1) Manual—Clinicians provided with the FYF manual only; (2) Workshop—Clinicians receive the FYF manual, and attend a 2-day intensive workshop; (3) Workshop-Plus—Clinicians receive the FYF manual, attend a 2-day intensive workshop, and attend bi-weekly phone conferencing on the treatment program (following review of videoed sessions). A comparison of these three conditions was selected because the conditions tend to parallel real-world efforts when learning a new treatment protocol (see Reaven et al., in press for complete details).

FYF Intervention

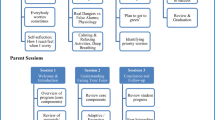

The FYF program is a 14 week, family focused cognitive behavioral therapy program delivered in multifamily groups, with each session lasting 1.5 h. Three FYF treatment manuals were used in this study: a parent workbook, a youth workbook, and a facilitator manual (Reaven et al. 2011). Traditional treatment sessions and activities utilized in CBT are modified for use with youth with ASD in the FYF program. This includes the use of video modeling, visual schedules, written worksheets, and multiple choice lists. There is also an emphasis on creative expression of social emotional content using multi-sensory activities.

Sessions consist of large group activities, simultaneous but separate parent and youth group meetings, and parent–youth dyad activities. Group sessions are interactive and activity-based and divided into two seven-session intervention blocks (i.e., psychoeducation and exposure). Weeks 1–7 focus on psychoeducation of anxiety and introduction to common CBT approaches and weeks 8–14 focus on hierarchical exposure in addition to using specific tools and strategies (i.e. deep breathing, positive coping statements, emotion regulation strategies) to reduce anxiety. In the second part of treatment (beginning in session 8), youth also work on creating their own “Facing Your Fears Movies,” to provide directed practice in exposure hierarchies, and consolidation of coping strategies. Participants choose movie topics (e.g., fear of spiders) and a role (e.g., fear facer, coach, narrator). The movies are meant to demonstrate all aspects of practicing facing fears including exposure steps, using coping strategies (e.g., helpful thoughts, deep breathing), and earning rewards for facing fears. Parents attend every session and encourage and cue their youth to engage in positive coping strategies and to face fears during sessions and as homework.

Measures

Acceptability Measures

Acceptability ratings were collected independently from parents, youth, and clinicians at the end of each of the 14 sessions using a 1-page survey comprised of questions rated on a scale of 1–5 with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. Forms contained ID numbers rather than names in order to be able to match acceptability ratings to outcome measures (e.g., SCARED ratings). Two of the four sites collected acceptability ratings anonymously which prevented comparisons to other measures. This decision was site specific and only pertained to acceptability data.

Written feedback was also collected about the relevance and helpfulness of each activity in a session. While there are several well-developed acceptability measures in the literature, the researchers chose to create a measure unique to the FYF treatment. Specifically, the researchers were interested in feedback from parents, youth, and clinicians about the particular FYF treatment. Youth used a 5-point pictorial scale to rate the helpfulness of each activity. A rating of “1” was paired with a sad face and a rating of “5” was paired with a happy face. Participants were asked to rate the acceptability of the main activities in each session. For example, an activity that was rated in session 4 (included in the psychoeducation block) was “Video on Relaxation” (i.e., participants view a brief video clip on deep breathing). An activity that was rated in session 8 (included in the exposure block) was “Exposure practice” (i.e., youth practiced steps created on their fear hierarchy). Parents, youth, and clinicians were also asked the following open-ended questions: (1) What was most helpful about today’s session? (2) What was the least helpful about today’s session? (3) Additional suggestions/comments?

Outcome Measure: Youth Anxiety Symptoms

The SCARED—Parent and Youth versions (Birmaher et al. 1999) were completed within 6 weeks of starting and ending treatment. Both versions consist of 41-items comprising five anxiety subscales (Panic, Generalized Anxiety, Separation Anxiety, Social Anxiety, and School Anxiety) and a total score. At both time points, parents and youth were asked to report on symptoms over the past month. The SCARED demonstrates excellent psychometric properties in typically developing youth populations (Birmaher et al. 1999; Hale et al. 2011). Results from a recent study confirm the 41-item measures five-factor structure and suggest good sensitivity (.71) and specificity (.67) among parents of youth with ASD (Stern et al. 2014). For the present study, the difference between pre and post-SCARED ratings (i.e., SCARED change) were used in the analyses.

Analysis Plan

To examine the degree of acceptability of the FYF program, we first ran descriptive statistics for acceptability ratings overall for parents, youth, and clinicians. Sessions were then divided into blocks (i.e., psychoeducation: sessions 1–7 and exposure: sessions 8–14). Session 14 is technically a graduation session; however, a portion of the group activities is devoted to tracking fear ratings and discussing future exposure practices, which is why it was included in the exposure sessions. For all analyses, an alpha of .05 was used. Paired sample t tests were used to compare parents and youth acceptability ratings. One-way analysis of variance was used to assess differences in clinician acceptability ratings across instructional conditions. Ordinary least squares multiple regression analyses were used to assess how parent and youth acceptability ratings relate to youth anxiety outcomes.

Results

Parent and Youth Acceptability Ratings

Means and standard deviations for each variable are reported in Table 2. In general, parent and youth acceptability ratings were high across all instructional conditions (Manual, Workshop, Workshop-Plus). There were no differences in parent or youth acceptability ratings across any of the clinician training conditions (p’s range from .40 to .10). Paired sample t tests revealed a significant difference between parent and youth acceptability ratings of the overall treatment, t(79) = − 4.34, p = .0001, psychoeducation sessions, t(79) = 4.98, p = .0001, and exposure sessions, t(79) = 2.78, p = .007. In all cases, parents rated treatment acceptability higher than youth. See Table 2 for session-by-session acceptability ratings for parents and youth. Qualitatively, youth rated sessions 5–7 lower than other sessions. Paired sample t tests also showed a significant difference in parent ratings of psychoeducation versus exposure sessions, t(79) = − 2.10, p = .039, and youth ratings of psychoeducation versus exposure sessions, t(79) = − 4.24, p = .0001. In both cases, exposure was rated more favorably than psychoeducation.

Clinician Acceptability Ratings

Parent and youth clinician acceptability was examined across conditions (i.e., Manual, Workshop, Workshop-Plus). A one-way ANOVA was completed to compare youth clinician acceptability ratings across the three conditions. The overall model was significant, F(2,62) = 8.001, p = .001, suggesting that there is a difference between youth clinician acceptability ratings across conditions. Tukey HSD posthoc contrasts found significant differences in acceptability ratings between the Manual (M = 3.84, SD = .33) and Workshop conditions (M = 4.25, SD = .36), p = .001, and between the Workshop (M = 4.25, SD = .36) and Workshop-Plus (M = 3.95, SD = .39) conditions, p = .026. A second one-way ANOVA was completed to compare parent clinician acceptability ratings across the three conditions. The overall model was significant, F(2,32) = 4.53, p = .018, suggesting that there is a difference between clinician acceptability ratings across conditions. Tukey HSD posthoc contrasts found significant differences in acceptability ratings between the Manual (M = 4.04, SD = .39) and Workshop conditions only (M = 4.41, SD = .30), p = .038.

Acceptability Ratings Related to Youth Outcomes

To examine the association between acceptability ratings and youth anxiety outcomes, separate multiple regression analyses were completed with parent and youth total SCARED change scores as the dependent variables and acceptability of the overall treatment as well as each block of treatment as the predictor variables. For the following results, only a subset of parents (N = 49) and youth (N = 46) were included from two of the four sites because acceptability data at these sites was collected anonymously and were not able to be matched with outcome data (see Table 3).

For parent report of acceptability, the overall model accounted for 6% of the variance in youth anxiety and approached significance, F(2,46) = 2.56, p = .089. Examination of acceptability of specific treatment blocks demonstrated that higher acceptability ratings for the exposure block accounted for a significant proportion of variance, β = 15.18, p = .030; however, this was not observed in the psychoeducation block. For youth, the overall regression model was significant and accounted for 25% of the variance in youth anxiety, F(2,43) = 4.33, p = .019, indicating that higher acceptability ratings predicted lower anxiety ratings on the SCARED. There was a significant predictive relationship between youth acceptability of exposure to youth ratings of anxiety, β = −10.24, p = .017. As with parent report, youth report of acceptability of the psychoeducation block was not associated with youth anxiety symptoms post-treatment.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to examine acceptability of a group CBT intervention for anxiety and ASD across multiple informants in a systematic manner. Overall, acceptability ratings were high for parents, youth, and clinicians, confirming the hypothesis that overall perceptions of the treatment will be positive. This finding is also consistent with previous reports of acceptability of FYF (Reaven et al. 2012, 2014).

As expected, parent ratings of acceptability were significantly higher for both psychoeducation and exposure sessions compared to the youth’s ratings. The lowered acceptability ratings for youth may reflect, in part, the challenges of participation in treatment. For instance, youth may have underrated acceptability if they perceived the treatment to further highlight their differences from neurotypical peers. In addition, parents initiated treatment and may have been more invested or open to strategies for addressing their youth’s anxiety symptoms, compared to the youth themselves. Parents tended to view the specific strategies for how to manage their youth’s anxiety as both easy to understand as well as effective, possibly increasing their self-efficacy in addressing these issues at home.

Youth acceptability ratings for each session, also may have been influenced by developmental factors including their overall mood on any given day. That is, the occurrence of a distressing event that coincidentally occurred on group day, may unduly influence a youth’s acceptability ratings for that particular session, as some youth may have a difficult time separating their current negative mood from the helpfulness of a particular treatment activity. In past studies, youth with ASD under reported their level of anxiety symptoms, which suggests a lack of insight into their emotional experiences (Blakeley-Smith et al. 2012). This decreased personal insight may impact youth’s understanding about why they are in treatment and how the treatment (or the learned strategies) may benefit them in the long-term. When looking at session-by-session mean ratings of youth acceptability, sessions 5–7 appear to be rated as lower than the other sessions. These sessions introduce cognitive strategies as well as focus on preparing for exposure, selecting goals, and designing steps for exposure practice, which may inherently cause youth anxiety. An important future direction may include gaining a better understanding about how to make these particular sessions more satisfactory or acceptable to youth.

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous research on the use of CBT in the general pediatric literature, both parents and youth rated exposure sessions as more acceptable when compared to psychoeducation sessions. This is somewhat puzzling given that exposure is often viewed as the more challenging part of treatment and resistance tends to be highest. One possible explanation for this finding may be related to the order of the intervention blocks (i.e., psychoeducation and exposure). Sessions with psychoeducational content occur early on the treatment, while sessions with exposure content occur after session 7. In the initial sessions, participants are meeting new people, learning new concepts, and are being asked to identify and discuss anxiety-provoking situations; thus, both parents and youth may experience increased anxiety associated with these initial sessions. Although exposure concepts are introduced in earlier sessions, exposure practices begin at week eight, and by this time, participants have had ample time to increase their comfort with other participants in the group. Participants are more familiar with the group routine, the clinicians, and with the expectations of group participation.

It may also be that participants have previously learned some of the strategies presented in the psychoeducation block of treatment, which may impact participants’ beliefs about the helpfulness of these strategies. Further, families may have less experience prior to treatment with creating a stimulus hierarchy of graded exposure steps, and may have also had less experience encouraging their child to face fears, making the exposure block more acceptable than the psychoeducation block. The novelty of these approaches may lead to increased hopefulness for the parents. In addition, because exposure is such an active and critical ingredient in treatment for anxiety, encouraging their youth to engage in exposure practice may allow parents to see meaningful behavior changes in their youth and may also provide them with the tools to help their sons and daughters face fears at home. The youth may feel a sense of pride or accomplishment for completing difficult exposures and for facing fears and their parents may be equally proud to share in their displays of “brave behavior.”

Significant differences were found in clinician ratings of acceptability across instructional condition. Although acceptability ratings were generally high for clinicians across condition, youth clinicians in the Workshop condition rated the treatment as significantly more acceptable than clinicians in the Manual or Workshop-Plus conditions. Similarly, parent clinicians in the Workshop condition rated the treatment as significantly more acceptable than clinicians in the Manual condition. Thus, participation in a Workshop appears to be positively related to treatment acceptability, while the addition of bi-weekly feedback and consultation (at least for youth clinicians only), resulted in relatively lowered acceptability ratings. It may be that clinicians in the Workshop condition found the treatment most helpful because they were provided with a one time “crash course” of the treatment, sufficient enough to successfully deliver the intervention. Receiving ongoing feedback may have made clinicians feel “on the spot” and may have negatively affected their experiences with the intervention. It may be helpful in the future to measure clinician ratings of acceptability of the supervisory experience, which could lead to improvements in supervision.

When examining the association between treatment acceptability and youth anxiety post-treatment, the overall hypothesis was supported. Results indicated that higher acceptability ratings of the overall treatment for parents and youth predicted lower anxiety symptoms on the SCARED post-treatment. More specifically, parents’ and youth’s acceptability ratings of exposure sessions in particular, were related to improvement in anxiety ratings. Believing that exposure practice is helpful predicts improvements in youth anxiety. Exposure is often thought of as the “bread and butter” of anxiety treatment and these findings suggest that participant perceptions regarding helpfulness of exposure may, in fact, impact treatment outcomes. The current findings suggest that making exposure more palatable to youth and their families (e.g., through fun activities like making movies) may impact the acceptability of facing fears.

Implications

Results from this study have important implications for treatment research. Despite previous research indicating that graded exposure may trigger increased client resistance and treatment refusal (Kendall et al. 2009; Abramowitz et al. 2002), youth and parents in the present study reported that they found exposure to be more helpful than psychoeducation, and that a positive view of exposure was related to positive treatment outcomes. Perhaps the ways in which exposure is introduced and encouraged in the FYF treatment (e.g., via making movies, video modeling, parent support through difficult exposures) may help youth and their families view facing fears as achievable and well worth the effort. Although both parent and youth participants in this study viewed exposure as quite helpful, one area for future research could include studying avenues for how to convey to the parents and youth who struggle with exposure, that graded exposure is necessary and doable, and that brave behavior is worthwhile. It is also important to consider ways to individualize treatment for families, as some youth may need more psychoeducation and some may need more exposure. Future research should also focus on further identifying ways to tailor treatment based on individual family needs.

An important factor related to the improvement of anxiety symptoms is the belief that treatment is helpful. Enhancing acceptability may in fact help reduce the risk of dropout and may increase treatment compliance and completion. Future studies should continue to examine treatment acceptability in this population, particularly when new treatments are developed. It may also be important to examine both parent and youth self-efficacy, particularly as it relates to treatment acceptability and to youth treatment outcome.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that may impact the interpretation and generalizability of the results. Ratings for both acceptability and anxiety may have been impacted by social desirability. All participants (i.e., parents, youth, clinicians) were aware that their acceptability ratings were being considered as part of research program, which could have led to inflated ratings of acceptability and lower ratings of anxiety post-treatment. Another limitation includes the grouping of sessions 1–7 as Psychoeducation, and sessions 8–14 as Exposure in that both blocks include activities that are not entirely reflective of their conceptual groupings (e.g., making movies included in the exposure block). Additionally, sessions 8–14 include a movie making activity where youth create movies about facing fears, which can be viewed as a fun, engaging activity that actually incorporates elements of both psychoeducation and exposure. Another limitation occurred during data collection as two sites collected acceptability data anonymously therefore only a subset of parents and children were included in the analyses reflecting acceptability and outcome. Finally, it is difficult to parse out the factors driving the relationship between acceptability and treatment outcome. Future research with larger sample sizes would allow enough power to examine specific treatment components (e.g., session by session comparisons) and acceptability of each component. This would be an interesting area for future research.

Overall, this is one of the first studies to document the relationship between treatment acceptability and youth outcome for youth with ASD and anxiety. The findings also suggest that there is a relationship between ongoing consultation for clinicians and ratings of acceptability. Most importantly, it highlights the significance of measuring acceptability as part of treatment research (at each session/component as well as globally), and shows that viewing exposure practice in a positive light may be a key component to improvements in youth with ASD and anxiety.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., Franklin, M. E., & Foa, E. B. (2002). Empirical status of cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analytic review. Romanian Journal of Cognitive & Behavioral Psychotherapies, 2, 89–104.

Allinder, R. M., & Oats, R. G. (1997). Effects of acceptability on teachers’ implementation of curriculum-based measurement and student achievement in mathematics computation. Remedial and Special Education, 18, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259701800205.

Berument, S. K., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Pickles, A., & Bailey, A. (1999). Autism screening questionnaire: Diagnostic validity. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 175(5), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.175.5.444.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011.

Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J., Ridge, K., & Hepburn, S. (2012). Parent-child agreement of anxiety symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.020.

Calvert, S. C., & Johnston, C. (1990). Acceptability of treatments for child behavior problems: Issues and implications for future research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_8.

de Bruin, E. I., Ferdinand, R. F., Meester, S., de Nijs, P. F. A., & Verheij, F. (2007). High rates of psychiatric co-morbidity in PDD-NOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 877–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0215-x.

Finn, C. A., & Sladeczek, I. E. (2001). Assessing the social validity of behavioral interventions: A review of treatment acceptability measures. School Psychology Quarterly, 16, 176–206. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.16.2.176.18703.

Hale, W. W., Crocetti, E., Raaijmakers, Q. A., & Meeus, W. H. (2011). A meta-analysis of the cross-cultural psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02285.x.

Kaczkurkin, A. N., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: An update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17, 337–346.

Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant youth behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1980.13259.

Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Perceived barriers to treatment participation and treatment acceptability among antisocial children and their families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9, 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009414904228.

Kazdin, A. E., Bass, D., Siegel, T., & Thomas, C. (1989). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and relationship therapy in the treatment of children referred for antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.4.522.

Kendall, P. C. (1994). Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.1.100.

Kendall, P. C., Comer, J. S., Marker, C. D., Creed, T. A., Puliafico, A. C., Hughes, A. A.,… Hudson, J. (2009). In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013686.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule (2nd ed.). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Miltenberger, R. G. (1990). Assessment of treatment acceptability: A review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 10, 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149001000304.

O’Brien, S., & Karsh, K. (1991). Treatment acceptability: Consumer, therapist and society. In A. Repp & N. Singh (Eds.), Perspectives on the use of nonaversive and aversive interventions for persons with developmental disabilities (pp. 503 516). Sycamore: Sycamore Publishing Company.

Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Beattie, T. L., Sullivan, A., Moody, E. J., Stern, J. A., Hepburn, S. L., et al. (2014). Improving transportability of a CBT intervention for anxiety in youth with ASD: Results from a US-Canada collaboration. Autism, 19, 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313518124.

Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Culhane-Shelburne, K., & Hepburn, S. L. (2012). Group cognitive behavior therapy for youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: A randomized trial. The Journal of Youth Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02486.x.

Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Nichols, S., & Hepburn, S. (2011). Facing your fears: Group therapy for managing anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Baltimore: Paul Brookes Publishing.

Reaven, J., Moody, E., Klinger, L., Keefer, A., Duncan, A., O’Kelley, S., … Blakeley Smith, A. (in press). Training clinicians to deliver group CBT to manage anxiety in youth with ASD: Results of a multi-site trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

Reimers, T. M., Wacker, D. P., Cooper, L. J., & de Raad, A. O. (1992). Acceptability of behavioral treatments for children: Analog and naturalistic evaluations by parents. School Psychology Review, 21, 628–643.

Silverman, W., & Albano, A. (1996). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for children for DSM-IV: (Child and Parent Versions). San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Stern, J. A., Gadgil, M. S., Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J. A., & Hepburn, S. L. (2014). Psychometric properties of the SCARED in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.008.

Taylor, S., Abramowitz, J. S., & McKay, D. (2012). Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.010.

Van Steensel, F. J., Bogels, S. M., & Perrin, S. (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0.

Walkup, J. T., Albano, A. M., Piacentini, J., Birmaher, B., Compton, S. N., Sherrill, J. T., & Iyengar, S. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(26), 2753–2766. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804633.

Wergeland, G. J. H., Fjermedtada, K. W., Marind, C. E., Storm-Mowatt Hauglanda, B., Silvermand, W. K., Ost, L. G., Havika, O. E., & Heiervanga, E. R. (2015). Predictors of dropout from community clinic youth CBT for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 31, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.01.004.

Wood, J. J., Drahota, A., Sze, K., Har, K., Chiu, A., & Langer, D. A. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend a special thanks to the clinicians, children, and parents who participated in this study.

Funding

This research is supported in part, by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (LEND) Grant T73MC11044 and by the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD) under the University Center of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCDEDD) Grant 90DD0632 of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This research was also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R33MH089291-03. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by NIH, HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors Audrey Blakeley-Smith, Ph.D., Susan Hepburn, Ph.D., and Judy Reaven, Ph.D. receive royalties from Paul Brookes Publishing for the Facing Your Fears Manual.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, C.E., Moody, E., Blakeley-Smith, A. et al. The Relationship Between Treatment Acceptability and Youth Outcome in Group CBT for Youth with ASD and Anxiety. J Contemp Psychother 48, 123–132 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-018-9380-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-018-9380-4