Abstract

Recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control; Sonnentag and Fritz (Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 204–221, 2007)) are thought to enhance both work and health outcomes, though the mechanisms are not well understood. We propose and test an integrated theoretical model in which work engagement and exhaustion fully mediate the effects of recovery experiences on job performance and health complaints, respectively. Meta-analytic associations (k = 316; independent samples; N = 99,329 participants) show that relaxation and mastery experiences positively predict job outcomes (work engagement, job performance, citizenship behavior, creativity, job satisfaction) and personal outcomes (positive affect, life satisfaction, well-being), whereas psychological detachment reduces negative personal outcomes (negative affect, exhaustion, work-family conflict), but does not seem to benefit job outcomes (work engagement, job performance, citizenship behavior, creativity). Control experiences exhibit negligible incremental effects. Path analysis largely supports the theoretical model specifying separate pathways by which recovery experiences predict job and health outcomes. Methodologically, diary and post-respite studies tend to exhibit smaller effects than do cross-sectional studies. Finally, within-person correlations of recovery experiences with outcomes tend to be in the same direction, but smaller than corresponding between-person correlations. Implications for recovery experiences theory and research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, organizational psychologists have pointed to recovery as a key way to unwind from work stress and improve well-being, citing growing evidence that recovery experiences during off-work time are positively related to well-being and negatively related to strain (see Sonnentag et al., 2017, for a qualitative review). This focus on recovery is timely because job stress is a global health crisis that significantly increases the odds of poor physical health and contributes to high costs of healthcare, turnover, and poor performance (Goh et al., 2015; Pfeffer, 2018). Off-work recovery experiences are conceptually linked to both positive work outcomes and personal health outcomes (Sonnentag et al., 2012).

Specifically, four recovery experiences have come to be the major focus of the recovery literature since Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) introduced the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (REQ). These four recovery experiences are psychological detachment (i.e., not thinking about work during nonwork time), relaxation (i.e., low psychological and physical activation), mastery (i.e., experiencing positive challenges and learning something new), and control (i.e., experiencing control over leisure time and activities). In developing the REQ, Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) sought to consolidate the field of work recovery research by enumerating the core functional aspects, or basic psychological experiences, underlying recovery activities. They state, “For example, one person might recover from job stress by going for a walk while the other recovers by reading a book. Although the activities are different, the underlying processes (e.g., relaxation) are rather similar” (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007, p. 204). Drawing upon Parkinson and Totterdell’s (1999) empirical classification of strategies for regulating unpleasant mood states, Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) focused on measuring the three so-called diversion strategies: psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery. In addition to these three, Sonnentag and Fritz also sought to measure control experiences due to the crucial theoretical role of control as a resource in Hobfoll’s (1989) conservation of resources (COR) theory.

Since the validation of the REQ, numerous studies have sought to establish the utility of each recovery experience for enhancing well-being and work engagement, as well as reducing exhaustion. Specially, empirical studies have found that employees who experience recovery report higher positive affective states (Fritz et al., 2010a; Sonnentag et al., 2008a) and better subjective well-being (de Bloom et al., 2012, 2015). In addition, such individuals report lower levels of exhaustion (Hahn et al., 2011; Kinnunen & Feldt, 2013; Siltaloppi et al., 2009) and strain (Shimazu et al., 2012) and also tend to experience higher levels of vigor at work (a subdimension of work engagement; Kinnunen & Feldt, 2013; Kinnunen et al., 2010; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012).

The growing interest in recovery has prompted both narrative (Sonnentag et al., 2017) and quantitative (Bennett et al., 2018; Steed et al., 2021; Wendsche & Lohmann-Haislah, 2017) reviews of the recovery literature. Although the previous quantitative reviews have shed light on the magnitude of bivariate associations between recovery and various predictors and outcomes (see Table 1 for a comparison), they provide an incomplete picture of the recovery process in particular ways. First, the previous focus on bivariate effects (Steed et al., 2021; Wendsche & Lohmann-Haislah, 2017) does not consider the overlap between the various recovery experiences nor specify their unique effects on work and health outcomes beyond each other. The current treatment can reveal, for example, that relaxation—which has a negative bivariate relation with negative affect—actually has no effect after the other recovery experiences are controlled. Second, previous work did not introduce a comprehensive theoretical model connecting recovery experiences with job performance and health outcomes [cf. Bennett et al. (2018) focus on only two outcomes—fatigue and vigor]. In essence, the theoretical model advanced in the current work—which establishes work engagement and exhaustion as complete mediators of recovery’s effects on job performance and health outcomes—describes a downstream process in the causal chain of recovery experiences not considered before and therefore extends the work done in previous meta-analyses. Third, although the recovery literature is an area where diary research is commonplace, the effects of temporal dynamics and within-person relationships have not been thoroughly examined in previous meta-analytic reviews. According to the theoretical conceptualization of recovery experiences (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007), recovery processes fluctuate within individuals and have dynamic effects on well-being and job outcomes. Despite this theoretical basis, previous meta-analyses addressing recovery have been based on between-person relationships. This is important because within-person and between-person recovery effects are distinct theoretical phenomena (Ostroff & Harrison, 1999), and as such the within-person effects have not been previously reviewed. Within-person recovery relationships capture the episodic effect of daily recovery on daily outcomes, while between-person recovery relationships capture how one’s tendency to experience recovery affects outcomes in general (Sonnentag et al., 2017). Therefore, in our empirical analyses we separately address between-person and within-person results and investigate the effect of study design (i.e., cross-sectional vs. daily diary or vacation/weekend study) on recovery.

With this in mind, we propose to make four contributions to research on recovery experiences. First, we propose and test a theoretical model that extends previous meta-analytic models by specifying dual pathways by which recovery experiences lead to performance and health. This begins to answer recovery researchers’ call for testing models of underlying mechanisms by which recovery experiences influence work and health outcomes (Sonnentag, 2018a, b; Sonnentag et al., 2012). In this model, consistent with the pathways suggested by the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), the effects of recovery experiences on job performance are mediated by work engagement, whereas effects of recovery experiences on individual health complaints are mediated by exhaustion. Besides specifying and finding support for these two mediation pathways, the model also considers all four recovery experiences simultaneously—and finds that not all recovery experiences have beneficial unique effects when considered together. Second, we meta-analytically estimate the magnitude and variability of the bivariate relationships of recovery experiences with a comprehensive set of personal and work-related outcomes. We then conduct regression analyses to determine whether recovery experiences uniquely predict these personal and work outcomes. Third, in addition to estimating between-person effects, we conduct a quantitative review of the within-person relationships (e.g., from experience-sampling studies; Demerouti et al., 2009) between recovery experiences and work and personal outcomes. Fourth, we identify possible moderators, positing that recovery experiences and outcomes may be more strongly related for some samples (i.e., cross-sectional samples and European samples). In summary, we believe that clarifying the relationships between recovery experiences and outcomes—as well as testing the theoretical linking mechanisms between recovery experiences and outcomes—will advance theory about recovery from work.

Theoretical Background

The foundational theories used to explain recovery are the effort-recovery model (ERM; Meijman & Mulder, 1998) and COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989; for a review see Hobfoll et al., 2018). The ERM holds that working inevitably requires effort expenditure, but continuous exposures to demands and stressors at work result in allostatic load reactions (e.g., fatigue). Such load reactions, however, can be removed or at least reduced through the absence of work demands. In other words, when individuals are no longer taxed by the demands of work, their functional systems can return to normal; but if their functional systems are continuously called upon without proper respites, their load reactions are not reversed before the next working period and further develop into long-term symptoms such as physical illness. Similarly, COR theory asserts that demands and stress in the environment (e.g., high job demands) deplete individuals’ resources (e.g., energies), and resource drains consequently harm well-being and health. As such, individuals must replenish lost resources and gain new resources to maintain their well-being and effectively function in the environment. Based on COR theory, recovery is conceptualized to occur when workers acquire, retain, protect, and enhance resources; halting cycles of resource loss and replenishing resources to prepare for the next working period (Hahn et al., 2011). Thus, both the ERM and COR theory suggest two necessary recovery processes: (a) temporarily being away from job demands and avoiding any activities that draw on the same functional systems as used for work and (b) gaining new resources that will aid in replenishing threatened or lost resources (e.g., self-efficacy, positive mood).

Overview of Existing Research on Recovery Experiences

Recovery experiences are subjective, individual perceptions of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, or control during off-work time (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Recovery experiences can occur both in the workplace (e.g., work breaks) and nonwork contexts (e.g., at home on weekends). Further, regarding temporal settings, research has examined recovery cross-sectionally (e.g., Siltaloppi et al., 2009) before and after respites (weekends or vacations; e.g., Fritz & Sonnentag, 2005, 2006), and repeatedly over time in diary studies (e.g., Binnewies et al., 2009). Also, a few studies have examined recovery in longer terms (e.g., across 1 year; Kinnunen & Feldt, 2013). Additionally, the outcomes considered in past research vary considerably and may be roughly classified as either covering personal outcomes or work outcomes. Personal outcomes include affect (positive affect and negative affect), energy (exhaustion, state recovery, and compensatory effort), sleep (sleep quality and sleep quantity), health (health complaints, life satisfaction, well-being, and stress), and role conflict (work-family conflict and family-work conflict). Job outcomes include work engagement and its subdimensions (vigor, absorption, and dedication), performance (job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, and creativity), proactive behavior at work (personal initiative), and job attitudes (job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and psychological withdrawal). The definitions of these outcomes and the scales used to measure them are provided in Table 2.

Recovery Experiences

The four recovery experiences as typically measured by the REQ (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007) are positively related to one another, but they have been distinguished in confirmatory factor analyses at both between- and within-person levels of analysis (Bakker et al., 2015; Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007;Sonnentag et al., 2008a, b). It is suggested that psychological detachment and relaxation experiences are the most beneficial experiences, especially for personal outcomes, such as exhaustion and well-being (Sonnentag et al., 2017). In particular, according to a qualitative review of the literature, psychological detachment has strong negative relationships with strain and positive relationships with well-being (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015). Regarding work-related outcomes, weak and mixed results have emerged. For example, psychological detachment had either weak or nonsignificant relationships with outcomes such as job performance and work engagement (e.g., de Bloom et al., 2015; Fritz et al., 2010b). Moreover, relaxation has been found to have positive links with work engagement and performance in some studies (e.g., de Bloom et al., 2015; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), but not others (e.g., Binnewies et al., 2009; Eschleman et al., 2014). In summary, the pattern might not consistently support the prevailing view that psychological detachment and relaxation are the most crucial recovery experiences that can improve employees’ functioning when they return to work.

Compared to psychological detachment and relaxation, research has underexplored the benefits of mastery and control experiences. Although mastery and control are expected to decrease strain and increase resources that can be reinvested in effective functioning at work, individual studies have found mixed results as well. For example, Moreno-Jiménez et al. (2012) found that mastery and control had negative bivariate relationships with work-family conflict, somatic symptoms, and anxiety; but when considered alongside other recovery experiences, mastery was no longer related to those outcomes, while control still was negatively related to the outcomes. On the contrary, Kinnunen et al. (2010) and Siltaloppi et al. (2009) found that when tested alongside other recovery experiences, mastery and control continued to negatively predict need for recovery while mastery still positively predicted work motivation.

Such inconclusive evidence led Sonnentag et al. (2017) to speculate that recovery experiences’ relationships with a variety of outcomes are more complex than reflected in bivariate correlations. Therefore, we meta-analytically estimate the relationships among recovery experiences and a comprehensive set of personal and work-related outcomes and use these estimates as input for testing all four recovery experiences simultaneously in regression equations to predict outcomes. This process will allow us to examine how each recovery experience uniquely predicts outcomes, while controlling for the other recovery experiences. Thus, we conjecture:

-

Research question 1: How do recovery experiences uniquely predict (a) personal and (b) work outcomes?

Within-Person Level Versus Between-Person Level

It should be also noted that recovery experiences and outcomes can vary between persons (e.g., people differ in the degree to which they experience relaxation) and within persons (e.g., on some days individuals may experience more relaxation than on other days). Previous meta-analyses have yet to consider whether the effect of recovery experiences at the within-person level differs from those at the between-person level. However, relationships at different levels of analysis have been found to vary in terms of direction and magnitude (Bliese et al., 2007). As an example, at the between-person level, those who exercise everyday will have better health indicators than those who do not; however, at the within-person level, a regular exerciser may not have that much change in their health indicators on the days they exercise (Schwartz & Stone, 1998). It is the cumulative effects of daily exercise that benefit individuals’ physiological health. On the other hand, at the within-person level, a regular exerciser may experience a greater change in their mood on the days they exercise (Giacobbi et al., 2005). Thus, daily exercise benefits individuals’ mood states. Beyond the exercise example, the general rule is that an X–Y relationship at one level of analysis implies nothing about the X–Y relationship at a different level of analysis (Ostroff, 1993).

As follows, it is unclear how relationships among recovery experiences and outcomes will differ at the within- and between-persons levels. At the within-person level, the relationship between daily recovery experiences and daily outcomes represents an episodic response to specific recovery event. In addition, the within-person level controls for the possible effects of individual differences. The repeated-measures or within-person designs (e.g., experience sampling/diary studies) utilized by researchers can better capture within-person fluctuations of recovery along with personal and work outcomes over time. This approach can help researchers answer to questions about whether people feel better or have a higher level of work outcomes on the days when they have experienced a higher level of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, or control during the evening before. Indeed, some diary studies have suggested that more than 80% of the variance in recovery can be attributed to within-person variations (e.g., ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Diary studies have also demonstrated significant intraindividual variations in outcomes of recovery, such as work engagement (Sonnentag, 2003) and exhaustion (ten Brummelhuis & Trougakos, 2014). Therefore, examining the recovery process within-individuals may reveal stronger associations with outcomes, similar to the effect of exercise on mood states, as this may be a process that unfolds within-individuals across days.

On the other hand, between-person level relationships of recovery experiences and outcomes reflect an accumulation of individual recovery episodes. This approach can help researchers answer questions about whether people who tend to experience more psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, or control generally feel better or generally experience better work outcomes. For example, recovery may be an experience that is beneficial for personal and work outcomes when it is practiced consistently, similar to the effect of exercise on health indicators. Accordingly, the ERM suggests that larger load effects of work demands require longer periods of time in order to be reversed. In other words, recovery experiences on one evening may not be enough to undo years of accumulated ill-effects of job stress. In addition, relationships at the between-person level may be larger due to more sources of systematic variance that affect these relationships. For example, emotional stability (i.e., one’s tendency to experience positive emotional states and adjust well to stress; Costa & McCrae, 1992) may strengthen the relationship between recovery experiences and outcomes. Due to their more positive approach to life, emotionally stable individuals may find it easier to detach from work, engage in more relaxation and mastery, and perceive more control over their time away from work (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Thus, examining recovery at the between-person level may result in greater associations with outcomes than the within-person level as the between-person level does not control for ones’ typical level of recovery experiences. In summary, it is unclear how the meta-analytic relationships will differ at the between- and within-person level of analysis, so we conjecture the following:

-

Research question 2: Do the relationships among recovery experiences and personal and work outcomes significantly differ at the between-person vs. the within-person level of analysis?

A Recovery-Engagement-Exhaustion Model of Performance and Health

The JD-R model (Demerouti et al., 2001; see Crawford et al., 2010), as revised by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), is a dual-process model that proposes two distinct mechanisms by which job demands and resources lead to work and health outcomes, respectively. In this model, work engagement is the motivational pathway by which job resources benefit job performance, whereas exhaustion is the health impairment pathway by which job demands lead to health problems. In an early attempt to incorporate recovery experiences into the JD-R model, Kinnunen et al. (2011) drew upon theoretical work by Demerouti et al. (2009) to propose and show that recovery experiences mediated the effects of job resources and job demands on work engagement and exhaustion, respectively. Additionally, according to the recovery paradox (Sonnentag, 2018a, b) and the stressor-detachment model (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015), job demands predict low levels of recovery experiences. Moreover, the meta-analysis by Bennett et al. (2018) demonstrated similar mediation pathways: job demands/resources → recovery experiences → fatigue/vigor. Furthermore, Steed et al. (2021) found significant relationships between job demands and recovery experiences (\(\overline{\rho }\) = − 0.18) and job resources and recovery experiences (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.24). In other words, recovery experiences transmit the effects of job demands and resources onto work engagement and exhaustion.

In brief, a high level of recovery experiences represents the accumulation of resources, and a lack of recovery experiences means that employees are unable to recover from job demands. Thus, drawing from the JD-R model and previous meta-analyses, our theoretical model in the current work extends past models by testing the dual paths by which recovery experiences predict job performance and health outcomes. In the motivational process, recovery experiences enliven work engagement which in turn helps workers more successfully accomplish their in-role tasks, while in the impairment process, workers with poor recovery experiences develop exhaustion, which in turn leads to health complaints such as headaches and gastrointestinal issues.

The Engagement Pathway

Work engagement is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74). The concept essentially captures the extent that workers view their work as interesting and captivating (absorption), and meaningful and significant (dedication), and stimulating and energetic (vigor). According to the JD-R model and engagement researchers, work engagement represents a motivational pathway to performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Christian et al., 2011; Halbesleben, 2010). When workers are dedicated to their work and enthusiastic about it, they will be more likely to want to sustain the positive situation and further improve it (Bakker et al., 2008a; Bakker et al., 2008b). In addition, when individuals are absorbed and concentrating on their work, they may pay more attention to details and improve their performance (Bakker et al., 2008a). Also, workers who have vigor will be able to put forth more effort and sustain their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Bakker et al., 2008a). In sum, enhanced work engagement will enable employees take a more active approach to their work, thereby improving their task performance. Relatedly, Salanova et al. (2005) found a positive relationship between hotel and restaurant workers’ work engagement and performance as rated by clients. Also, meta-analytic evidence shows work engagement is related to task performance (ρ = 0.43; Christian et al., 2011).

Our theoretical model specifies that this motivational state of work engagement may be the key pathway through which recovery experiences facilitate job performance, mainly because recovery experiences are theorized to generate and replenish personal resources that may be important predictors of work engagement (Kinnunen et al., 2011; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). For example, as psychological detachment and relaxation involve unwinding and recuperation from stress, they are linked to various positive states that further trigger work engagement, such as feelings of vigor and optimism at work (e.g., Ragsdale & Beehr, 2016; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Also, psychological detachment and relaxation are related to feelings of being recovered after respites, which are linked to better task performance (e.g., Binnewies et al., 2010). Additionally, mastery and control experiences are conceptualized to enhance internal resources (e.g., self-assurance, self-efficacy) that may be useful for work (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). Likewise, control experiences predicted higher self-regulatory capacity, which is linked to work engagement (Ragsdale & Beehr, 2016). According to the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) and COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), these positive resources can translate into work engagement, in that employees with increased personal resources are less discouraged by setbacks and expend less energy doing job tasks, and therefore may more easily experience engagement on the job.

Bakker et al. (2008a) found direct support that work engagement was a function of recovery perceptions, and that this work engagement predicted daily performance in turn. Altogether, the common theorization deriving from the JD-R model and recovery theory suggests that work engagement will act as an enlivening pathway from recovery experiences to job performance. That is, workers who enjoy more recovery experiences during off-work time will remain more engaged in their work, thereby improving their performance. Thus, we propose the following:

-

Hypothesis 1: Work engagement mediates the positive relationship between recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control) and job performance.

The Exhaustion Pathway

Exhaustion is a state characterized by physical fatigue and a sense of feeling emotionally and psychologically drained (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). It is a reaction that occurs when workers are unable to recuperate from job demands (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). According to the JD-R model and burnout researchers, a primary consequence of exhaustion is poor health (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Maslach, 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Shirom et al., 2005). Exhaustion impairs physical health as it involves the activation of physiological systems that respond to stress and makes daily functioning more effortful (Bakker & Costa, 2014; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Meijman & Mulder, 1998). The exposure to heightened physiological responses and increased effort result in the manifestation of physical symptoms, such as backache, headache, eye strain, and sleep disturbance (Nixon et al., 2011). For example, data from three large Dutch worker samples (van Veldhoven & Sluiter, 2009) demonstrated that exhaustion had a significant positive relationship with sleep complaints (sample 1), health complaints (e.g., headache, neck pain, palpitations, stomach pain; sample (2), and sickness absenteeism (sample 3). Also, meta-analytic evidence showed that exhaustion is significantly related to absenteeism, an indicator of health impairment (ρ = 0.21, Swider & Zimmerman, 2010).

Our theoretical model argues that workers who do not have sufficient recovery experiences are more likely to experience exhaustion, which will impair physical health, mainly because lack of recovery is theorized to prolong physiological reactions to stress and prevent effective coping (Meijman & Mulder, 1998; Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). For example, when individuals do not experience psychological detachment or relaxation, their work-related stressors remain activated, preventing their physical and psychological systems from recharging. Following this logic, Slatcher et al. (2010) found that lack of psychological detachment (i.e., work-related worry) is positively related to cortisol levels (a physiological stress response) in a sample of working couples over 6 days. Further, relaxation techniques (e.g., meditation, autogenic training) have been found to counteract the activation of physiological stress response systems (Esch et al., 2003). Also, mastery and control represents resource-providing experiences that have been found to help workers cope with exhaustion (e.g., Kinnunen et al., 2010; Siltaloppi et al., 2009). Through mastery, employees gain a sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Without these positive internal resources, employees struggle to deal with stressors in the environment, thereby increasing exhaustion. A series of studies has found a negative correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy and exhaustion (e.g., Friedman, 2003; Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007). Similarly, lack of control over events in one’s life is thought to diminish one’s ability to cope with exhaustion (Lazarus, 1966). Lower physiological responses to stress have been consistently found in those who reported effective coping and a perception of control over their environments (Cacioppo, 1998; Ursin & Eriksen, 2004).

Ragsdale et al. (2011) found support that exhaustion was a function of recovery experiences during off-work time and that exhaustion in turn predicted poor well-being upon returning to work. In sum, the common theorization deriving from the JD-R model and recovery theory suggests that exhaustion will act as an impairment pathway from poor recovery experiences to health complaints. That is, workers who do not experience recuperation during off-work time will experience stress reactions associated with exhaustion, thereby increasing their health complaints. Thus, we propose the following:

-

Hypothesis 2: Exhaustion mediates the negative relationship between recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control) and health complaints.

Moderators

Study Design (Cross-Sectional vs. Diary/Post-respite)

It is unclear whether there are differences in the relationships between meta-analytic associations assessed in cross-sectional studies and those assessed in a study with a time lag (i.e., diary studies on evening recovery and post-respite studies of weekend or vacation recovery). It may be that individuals perceive their experiences of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control to be deeper when they are assessing these experiences immediately after their evening respite (daily diary studies assess recovery experiences at bedtime) or after their weekend or vacation respite. Therefore, the strength of the relationships between recovery experiences and outcomes may be stronger in studies with diary designs or post-respite design compared to a cross-sectional design. On the other hand, there is more consistent evidence to suggest that the cross-sectional associations of the present model may be stronger. Relationships assessed in cross-sectional research tend to be inflated by contemporaneous common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

Hypothesis 3: Relationships among recovery experiences, work engagement, exhaustion, job performance, and health complaints will be stronger for samples with a cross-sectional design than for those with diary/post-respite designs.

Study Location (European vs. Non-European)

Cultural values may explain the potential moderating effect of study location (European vs. non-European) on the meta-analytic relationships in our model involving recovery experiences. The non-European studies in the recovery literature are mainly conducted in the USA; however, other studies have also been conducted in Australia, Canada, China, Iran, Japan, and South Korea. Non-European countries, such as the USA and China, tend to attach more value to work (Snir & Harpaz, 2006). These society-level values can affect the way individuals deal with their day-to-day lives and may drive them to place less emphasis on their recovery during leisure time. Furthermore, the work centrality cultural norm is evident in these countries by the policies surrounding leisure time. For example, the USA has no mandated minimum paid annual vacation or paid holidays (OECD, 2020). In contrast, European countries have on average 22 mandated paid vacation days and 13 holidays (OECD, 2020). In addition, contacting employees during leisure time has been banned in a growing number of European countries, such as Italy, Portugal, and France (Keane, 2021). Furthermore, although not yet mandated by law, many German and Scandinavian companies have policies in place that limit the digital connection employees have during their leisure time (Keane, 2021). These laws and policies are meant to protect one’s “right to disconnect.”

As follows, Europeans may strive for deeper experiences away from the workplace as their nonwork lives are more central to them compared to non-Europeans. Thus, we expect that Europeans will have stronger associations among recovery experiences, work engagement, exhaustion, job performance, and health complaints. For instance, Europeans may spend more time engaging in hobbies, which would encourage deeper mastery experiences. Also, Europeans may spend less time thinking about work and more time unwinding (i.e., psychological detachment and relaxation). Further, because it is accepted in European culture that individuals spend time on leisure, Europeans may feel more empowered to exert control of their time away from work (i.e., control experiences). On the other hand, non-European individuals may experience negative reactions when they are disconnected from work as work is more central to their lives. Non-Europeans may also feel the need to be connected to work more strongly than those in European countries. The stress or guilt that follows disconnecting from work may counterbalance the benefits that psychologically detaching from work provide. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

Hypothesis 4: Relationships among recovery experiences, work engagement, exhaustion, job performance, and health complaints will be stronger for European samples than for non-European samples.

Method

Literature Search

We performed our meta-analysis following the suggestions of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2008) and previous authors (Aytug et al., 2011). First, we conducted the literature search using several strategies. We searched PsycInfo for articles published since 1998 by keywords (i.e., “recovery” combined with “psychological detachment,” “relaxation,” “control,” “mastery,” or “work”). A start date of 1998 was chosen because Meijman and Mulder’s (1998) ERM provides the theoretical background for much of the recovery literature. Next, we used Google Scholar to identify all articles that cited Sonnentag and Fritz (2007), the original article that first introduced the REQ, as many subsequent studies on recovery have used this measure. Then, to identify unpublished articles, Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Work, Stress and Health, and Academy of Management conference programs were searched. The search was conducted up until July 2021. Finally, we double checked that our search contained all articles used in previous meta-analyses that involve recovery experiences (Bennett et al., 2018; Steed et al., 2021; Wendsche & Lohmann-Haislah, 2017). Results yielded 4832 studies for possible inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Inclusion Criteria

We included primary studies that reported relationships between (a) at least one recovery experience (e.g., psychological detachment) and (b) at least one other recovery experience or outcome (e.g., sleep quality). To be included, studies had to be published in English and the recovery experience had to reference nonwork time (i.e., evenings, weekends, or vacations). Furthermore, we included correlations at both the between-person and within-person levels of analysis, but these correlations were not combined because they are at different levels of analysis (Ostroff & Harrison, 1999). In the case of repeated-measures studies, if a study reported both a cross-sectional and a lagged relationship (i.e., detachment at T1 and exhaustion at T1 vs. detachment at T1 and exhaustion at T2), we included the lagged relationship in the present meta-analysis to mitigate the potential impact of contemporaneous common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Also, if lagged studies reported multiple time lags, the shortest lag was selected to reflect the proposed temporal ordering of recovery experiences and outcomes. For example, evening psychological detachment measured at bedtime should be temporally followed by vigor or exhaustion the next morning, rather than vigor or exhaustion at the end of the next workday. This led to the inclusion of 292 papers containing 316 samples.

Coding Procedures

Three coders extracted the following information independently: data on the between-person and within-person correlations, study design (e.g., daily diary, weekly diary, cross-sectional); between-person and within-person sample sizes, reliability, average weekly work hours, average age, percent male, study location; and whether the study was published or unpublished. For numerical variables, the average interrater reliability (r = 0.97; ICC1 = 0.97) was very high. The average interrater reliability for categorical variables (κ = 0.85) also indicates high agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977). However, we note that categorical variables (e.g., study design, variable label) are both subjective in nature and are sometimes described ambiguously in primary studies.

Of the 316 studies we coded, these could be categorized by study design into nine unique categories: (a) 157 (or 50%) were cross-sectional, (b) 87 studies (or 28%) had a daily diary design (daily diary studies had an average length = 7.16 days, SD = 3.20 days), (c) 6 (or 2%) had a weekly diary design, (d) 16 (or 6%) of the studies evaluated individuals both before and after (also sometimes during) a respite (i.e., weekend or vacation), (e) 15 (or 5%) studies used two measurement points, which were 1 month apart, (f) 5 (or 2%) studies used two measurement points, which were 1 week apart, (g) 2 (or 1%) used two measurement points, which were two weeks apart, (h) 15 (or 5%) were longer-term studies (i.e., spanning at least 4 months), and finally (i) 10 (or 3%) studies were experiments (for these studies, we only coded the relationships among recovery experiences and outcomes in the control group, or before any intervention took place). Three studies did not have a design that fit neatly into one of the above eight categories (but were still included in the meta-analysis). Zhou et al. (2020) had two measurement points, which were 6 weeks apart; DeArmond et al. (2014) had a design with 3 measurement points over 2 months; and Derks et al. (2014a) had a design with 6 measurement points over 2 weeks. In addition, roughly half of the studies in the current meta-analysis were conducted in Europe (159 studies or 50%).

Developing Coding Categories

For the outcome variables, 24 outcome constructs emerged and are summarized in Table 2. Most of the outcomes were straightforward; however, there was a small number of situations when the authors had to discuss which outcome construct a variable fell under. To do this, we started with frameworks presented in the occupational health psychology literature along with past research, underlying theory, item content of measures, and correlations among variables. We consulted the primary studies for construct definitions and item content. We worked collaboratively to categorize variables into overarching constructs for use in the meta-analysis. If there was not a clear case for combining variables, they were left separate. For example, studies that assessed negative affect as well as those that assessed depression and anxiety were all coded into the category of negative affect. These variables can fall under the general definition of negative affect as they are strongly related to measures of negative affect (Watson et al., 1988a).

In addition, studies assessing variables related to exhaustion were also discussed. The majority of studies in the current meta-analysis examined an exhaustion subdimension of a burnout inventory [e.g., the emotional exhaustion subscale of Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) Burnout Inventory (MBI) or the exhaustion subscale of the Oldenburg Burnout inventory (OLBI; Demerouti et al., 2003)]. Ultimately, we decided that the exhaustion category would also include burnout variables, which were usually assessed by some version of the MBI, the OLBI, the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM; Shirom and Melamed 2005), Wharton’s (1993) Burnout Measure, or Pines and Aronson’s (1988) Burnout Measure. Further, the exhaustion category also included need for recovery variables (de Croon et al., 2006) and measures of fatigue (i.e., the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion Recovery [OFER; Winwood et al., 2006], Checklist Individual Strength [CIS-20R; Vercoulen et al., 1994]). These variables were combined because they fall under the general definition of exhaustion and have very similar items. As further evidence for the convergence between these constructs, Schaufeli and van Dierendonck (2000) reported correlations near unity between “need for recovery” measures and the exhaustion facet of burnout measures (r = 0.84, N = 742; r = 0.75, N = 559; see van Veldhoven & Broersen, 2003). In sum, although burnout measures are included, the “exhaustion” variable by and large reflects a state of exhaustion as most studies measure the exhaustion subdimension of burnout or fatigue/need for recovery and these variables are conceptually and empirically overlapping.

Furthermore, exhaustion and work engagement were not collapsed into a single outcome variable despite previous research suggesting that the core dimensions of exhaustion as assessed by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986) and work engagement as assessed by the Utrecht Work Engagement scale (Schaufeli et al., 2002) are opposite ends of the same spectrum (Demerouti et al., 2010; González-Romá et al., 2006), and exhibit an average corrected meta-analytic correlation of -0.55 (Cole et al., 2012). This was done to better reflect our theoretical model and determine if recovery variables have different or similar relationships with work engagement vs. exhaustion. Also, whereas measures used to assess exhaustion varied, almost all (i.e., 99%) studies examining work engagement used the same version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale.

Finally, most of the studies assessing well-being used the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Goldberg, 1972). However, some studies scored this outcome as a measure of health complaints rather than well-being. For those studies that scored the GHQ as poor well-being or complaints, we reversed correlation signs for consistency purposes. In addition, some studies evaluated sleep quality with measures of insomnia. For studies that assessed sleep quality with insomnia measures, we also reversed correlation signs. Thus, all outcome variables were coded such that higher numbers reflect more of the variables.

Meta-analytic Procedures

We conducted a Hunter and Schmidt (2004) psychometric meta-analysis using the package metafor in R (Viechtbauer, 2010). Each sample effect size was corrected individually for measurement error in both the predictor and the criterion to estimate relationships: (a) among recovery experiences and (b) personal and job outcomes with recovery experiences. Also, for the within-person correlations, we used only those correlations from daily diary studies, so that all within-person correlations represent days nested within individuals.Footnote 1 No reliability estimates were reported by primary study authors for any single-item measures (such as sleep quantity and quality). The reliability of each of the single-item variables was fixed to 1.0 (i.e., correlations with these variables were not corrected for unreliability) for the sake of conservative estimation of corrected correlations. In the case of studies in which reliability estimates for outcomes were not reported when they could have been, the mean reliability for that construct (averaged across all the studies cumulated in the meta-analytic database) was used. In total, we generated between- and within-person meta-analytic correlations among the recovery predictors and between recovery predictors and each outcome (when at least 3 primary studies were available).

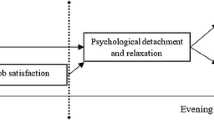

We conducted multiple regression analyses in R using recovery experiences to predict outcomes. We used the between-person correlations as the basis for these regression analyses because we did not have enough correlations at the within-person level to enable estimation of the regression models. Regression significance tests were based on the harmonic mean sample size (Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995). In these analyses, we examined whether each of the four recovery experiences uniquely contributed to the prediction of outcomes. Next, we used the between-person meta-analytic correlations as the basis for a meta-analytic structural equation model (MASEM; implemented in the lavaan package in R; Rosseel, 2012) to test our hypotheses and evaluate the fit of the comprehensive model of recovery experiences and outcomes (Fig. 1). The predictors include the recovery experiences, while the mediators (i.e., work engagement and exhaustion) and outcomes (i.e., health complaints and job performance) are those specified by the JD-R model. Further, to test the indirect or mediated paths specified in the model, we used Monte Carlo 95% confidence intervals based upon 10,000 repetitions (Selig & Preacher, 2008).

Recovery-engagement-exhaustion model of performance and health (all samples). Note: Path estimates in bold underline are from full mediation model (χ2 = 481.84, df = 8, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.040). Path estimates in italics are from partial mediation model (saturated model, df = 0, χ.2 = 0) and are reported in the manuscript. Solid lines are significant at the p < 0.05 level, whereas dashed lines are p > 0.05 (ns). Harmonic mean N = 10,488

Next, we conducted meta-analytic moderator analyses. These moderator analyses focused on examining the effects of two study variables (i.e., study location European or not, study design) on the relationships utilized in the model. To test for moderating effects, we adopted the weighted least squares regression procedure recommended by Steel and Kammeyer-Mueller (2002) to determine whether differences between subgroups were statistically significant. Specifically, we used the moderators as independent variables (dummy coded), in a weighted least squares regression, to predict the corrected correlation coefficients for each relationship.

Finally, we conducted funnel plot and trim‐and‐fill analyses (Kepes et al., 2012) to determine if the meta-analytic results might be impacted by publication bias. The funnel plot distributions display the magnitude of relationships on the x-axis and precision along the y-axis. The trim-and-fill method evaluates the degree of symmetry in a funnel plot distribution. For these analyses, we only looked at relationships with at least 10 correlations (k). If our meta-analytic correlation and the trim-and-fill adjusted correlation yield identical or comparable estimates, then publication bias is likely absent.

Results

Between-Person Intercorrelations Among Recovery Experiences

Table 3 reports the between-person meta-analytic correlations among recovery experiences. As shown in Table 3, the four types of recovery experiences (psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control) are all significantly positively intercorrelated (i.e., all confidence intervals exclude zero), such that individuals who tend to experience one type of recovery experience are also more likely to experience another.

Between-Person Correlations of Recovery Experiences with Outcomes

Psychological Detachment

Table 4 reports between-person meta-analyses of psychological detachment with outcomes. Psychological detachment was generally associated with better personal outcomes: mood (positive affect ρ = 0.16; negative affect ρ = − 0.28), energy (exhaustion ρ = − 0.32; state recovery ρ = 0.37; compensatory effort ρ = − 0.29), sleep (sleep quality ρ = 0.31; sleep quantity ρ = 0.21), health (health complaints ρ = − 0.20; life satisfaction ρ = 0.22; well-being ρ = 0.24; stress ρ = − 0.19), and work-family conflict (ρ = − 0.33). In contrast to its expected relationship with personal outcomes, psychological detachment was generally weakly related to work outcomes: work engagement (ρ = − 0.01; ns), organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (ρ = − 0.07), creativity (ρ = − 0.11), personal initiative (ρ = − 0.25), job performance (ρ = 0.02; ns), turnover intentions (ρ = − 0.003; ns) and psychological withdrawal (ρ = − 0.08; ns). However, psychological detachment was positively related to job satisfaction (ρ = 0.23).

Relaxation

Table 5 reports the between-person meta-analytic relationships of relaxation with outcomes. Relaxation was favorably associated with personal outcomes: mood (positive affect ρ = 0.31; negative affect ρ = − 0.23), energy (exhaustion ρ = − 0.32; state recovery ρ = 0.46; compensatory effort ρ = − 0.16), sleep (sleep quality ρ = 0.30; sleep quantity ρ = 0.14), health (health complaints ρ = − 0.24, life satisfaction ρ = 0.37, well-being ρ = 0.36, stress ρ = − 0.27), and work-family conflict (ρ = − 0.33). In addition, relaxation was associated with better job outcomes: work engagement (ρ = 0.22), job performance (ρ = 0.18), OCB (ρ = 0.11), job satisfaction (ρ = 0.29), and psychological withdrawal (ρ = − 0.14). However, it was not significantly related to creativity (ρ = 0.04; ns) and personal initiative (ρ = 0.11; ns).

Mastery

Table 6 reports between-person meta-analyses of mastery with outcomes. Mastery is related to better personal outcomes: mood (positive affect ρ = 0.30, negative affect ρ = − 0.19), energy (exhaustion ρ = − 0.23, state recovery ρ = 0.32), sleep quality (ρ = 0.17), health (health complaints ρ = − 0.17, life satisfaction ρ = 0.33, well-being ρ = 0.32, stress ρ = − 0.23), and work-family conflict (ρ = − 0.22). Mastery was also favorably related to work outcomes: work engagement (ρ = 0.34), job performance (ρ = 0.28), OCB (ρ = 0.28), creativity (ρ = 0.44), personal initiative (ρ = 0.14), job satisfaction (ρ = 0.26), and psychological withdrawal (ρ = − 0.12).

Control

Table 7 shows between-person meta-analyses of control with outcomes. Generally, fewer studies have examined relationships between control and both personal and job outcomes. Among the studies that did include control, it was consistently related to better personal outcomes: affect (positive affect ρ = 0.28, negative affect ρ = − 0.26), energy (exhaustion ρ = − 0.28, state recovery ρ = 0. − 039), sleep (sleep quality ρ = 0.28, sleep quantity ρ = 0.22), health (health complaints ρ = 0.22, life satisfaction ρ = 0.33, well-being ρ = 0.38, stress ρ = − 0.27), and work-family conflict (ρ = − 0.36). In addition, control was related to favorable work outcomes: work engagement (ρ = 0.22), job performance (ρ = 0.23), OCB (ρ = 0.07), creativity (ρ = 0.10), job satisfaction (ρ = 0.35), and psychological withdrawal (ρ = − 0.21).

Meta-analytic Regressions Involving Recovery Experiences

Recovery Experiences as Predictors of Personal Outcomes

We next assess whether each recovery experience uniquely predicts an outcome beyond the other recovery experiences to answer research question 1 (“How do recovery experiences uniquely predict (a) personal and (b) work outcomes?”). Table 8 reports results of regressions of each personal outcome onto the set of four recovery experiences. We only examined the personal outcomes for which meta-analytic correlations of all four recovery experiences were available (i.e., positive affect, negative affect, exhaustion, state recovery, sleep quality, sleep quantity, health complaints, life satisfaction, well-being, stress, and work-family conflict are included in Table 8; we omitted compensatory effort and family-work conflict).

In seeking to identify themes in the pattern of results in Table 8, for the sake of parsimony we focus on standardized regression coefficients that exceed |β |= 0.15 in magnitude. First, psychological detachment experiences uniquely predict negative affect (β = − 0.22), exhaustion (β = − 0.20), state recovery (β = 0.16), sleep quality (β = 0.20), sleep quantity (β = 0.18), and work-family conflict (β = − 0.20). Second, relaxation experiences uniquely predict positive affect (β = 0.20), state recovery (β = 0.25), life satisfaction (β = 0.20), and well-being (β = 0.15). Third, mastery experiences uniquely predict positive affect (β = 0.20) state recovery (β = 0.16), life satisfaction (β = 0.20), and well-being (β = 0.18). Fourth, control experiences uniquely predict sleep quantity (β = 0.23), well-being (β = 0.20), and work-family conflict (β = − 0.22). Generally, it seems that psychological detachment is the strongest (negative) predictor for the negative personal states (i.e., negative affect, exhaustion, work-family conflict), whereas the more positive personal states are predicted by relaxation (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction, well-being) and mastery (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction, well-being). Thus, this answers research question 1a as psychological detachment is associated with decreasing negative personal states, whereas relaxation and mastery are associated with increasing positive personal states when recovery experiences are considered simultaneously.

Recovery Experiences as Predictors of Job-Related Outcomes

Table 9 reports regressions of each job-related outcome onto the set of four recovery experiences. We only examined the job outcomes for which meta-analytic correlations with each recovery experience were available (i.e., work engagement, vigor, absorption, dedication, job performance, OCB, creativity, job satisfaction, and psychological withdrawal are included in Table 9; we omitted personal initiative and turnover intentions).

First, psychological detachment uniquely negatively predicted work engagement (β = − 0.20), OCB (β = − 0.17), and creativity (β = − 0.18). Second, relaxation experiences uniquely positively predicted work engagement (β = 0.24). Third, mastery experiences uniquely positively predicted work engagement (β = 0.28), job performance (β = 0.21), OCB (β = 0.29), and creativity (β = 0.49). Fourth, control experiences uniquely positively predicted job satisfaction (β = 0.23) and negatively predicted psychological withdrawal (β = − 0.20). Generally, relaxation, mastery, and control experiences positively predict work outcomes (i.e., work engagement, job performance, OCB, creativity, and job satisfaction). In contrast, it appears that psychological detachment experiences negatively predict work outcomes (i.e., work engagement, OCB, and creativity); however, at the bivariate level these relationships tend to be small and nonsignificant. Therefore, the significant incremental negative relationships for detachment may be due to a statistical artifact. These results answer research question 1b as psychological detachment is negatively associated with work outcomes, whereas relaxation, mastery, and control are positively associated with work outcomes when recovery experiences are considered simultaneously.

Theoretical Mediation Model Results

Next, we test a theoretical mediation model extending the JD-R model with two separate mechanisms (work engagement and exhaustion) linking recovery experiences to job performance and health complaints. Figure 1 shows our theoretical model. The full mediation model (with the work engagement pathway and the exhaustion pathway) specifies no direct paths from recovery experiences to job performance or health complaints. Using the meta-analytic correlation matrix in Table 10 as input for these analyses, the full mediation model exhibited adequate overall fit to the meta-analytic data (χ2 = 481.84, df = 8, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.040), supporting the proposed recovery-engagement-exhaustion model. In addition, for the sake of completeness we specified a partial mediation model that included direct paths from each recovery experience to both job performance and health complaints, which is a saturated model (df = 0) and therefore has perfect goodness of fit by design (James et al., 2006). As seen in Fig. 1, the addition of direct paths from the four recovery experiences to job performance and health complaints had little effect on the magnitudes of the hypothesized mediation pathways. To be conservative, we tested the hypothesized mediation effects in the presence of (i.e., while controlling for) the direct effects.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that work engagement would mediate the relationship between recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control) and job performance, and hypothesis 2 predicted that exhaustion would mediate the relationship between recovery experiences and health complaints. To test these two sets of mediation hypotheses, we examined each path coefficient (i.e., joint significance test) as well as the statistical significance of the indirect paths when the direct paths were also modeled (see Hayes & Scharkow, 2013).

As displayed in Fig. 1, each of the recovery experiences exhibited a statistically significant path coefficient both predicting work engagement (psychological detachment β = − 0.20; relaxation β = 0.19; mastery β = 0.28; control β = 0.06) and predicting exhaustion (psychological detachment β = − 0.20; relaxation β = − 0.11; mastery β = − 0.12; control β = − 0.07). Overall, the R2 or the variance explained by recovery experiences was 15% for work engagement and 15% for exhaustion. Relaxation and mastery appear to enhance work engagement while control has a small enhancing effect; and all four recovery experiences appear to reduce exhaustion, although only psychological detachment has a substantive effect (|β |> 0.15). In addition, psychological detachment appears to harm work engagement; however, this may be due to a statistical artifact given its high interrelation with the other recovery experiences.

Next, work engagement significantly predicted job performance (β = 0.40), whereas exhaustion significantly predicted health complaints (β = 0.45). As shown in Table 11, the indirect effects of psychological detachment (− 0.08, 95% CI [− 0.09, − 0.07]), relaxation (0.08, 95% CI [0.07, 0.09]), mastery (0.11, 95% CI [0.10, 0.12]), and control (0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.03]) on job performance via work engagement were all statistically significant. The R2 was 25% for job performance. These results provide support for hypothesis 1 (i.e., recovery experiences → work engagement → job performance), but note that there was a negative indirect effect of psychological detachment. We next tested the indirect effects of the four recovery experiences on health complaints via exhaustion (hypothesis 2: recovery experiences → exhaustion → health complaints). As shown in Table 11, the indirect effects of psychological detachment (− 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.10, − 0.08]), relaxation (− 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.06, − 0.04]), mastery (− 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.06, − 0.04]), and control (− 0.03, CI [− 0.04, − 0.02]) on health complaints through exhaustion were all statistically significant. The R2 was 23% for health complaints. These results support hypothesis 2. To summarize the results of the theoretical path model, we note that (a) recovery experiences predict job performance through the mechanism of work engagement; (b) psychological detachment is a negative predictor of work engagement, whereas relaxation, mastery, and control are positive predictors of work engagement; and (c) recovery experiences negatively predict health complaints through the mechanism of exhaustion.

Moderator Analyses

We next examined the potential moderating effects of study-related variables (i.e., study design and study location) on the relationships used in our model (see Table 12). Note that for some moderators, there were relatively small sample sizes within specific moderator categories (i.e., for the diary/post-respite designs, N’s ranged from 211 to 1657 for correlations involving job performance or health complaints). For these particular moderator analyses, the results should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless (as enumerated below), even for these diary/post-respite moderator categories with N’s in the low hundreds, the observed meta-analytic correlations tended to not significantly differ from the corresponding cross-sectional correlations (see Table 12).

For study design, we compared studies with diary designs or post-respite designs to those with cross-sectional designs. For coding the moderator variable, cross-sectional designs were dummy coded as 0 and diary and post-respite designs as 1. Studies that used a longitudinal design spanning at least 6 months, or a time lag between measures of 1 month or greater, were omitted from these moderator analyses (i.e., the remaining studies—which were the focus of the current analysis—had time lags of 1 week or shorter). By assessing time lags shorter than 1 month, we focused on comparisons involving the modal diary and post-respite primary study designs used in research on recovery experiences. When inspecting study designs in Table 12, it generally seems that the meta-analytic correlations for diary/post-respite designs are similar to or slightly smaller than corresponding correlations from cross-sectional designs. To further determine whether these differences were statistically significant, weighted least squares regressions were conducted. Diary/post-respite study design significantly moderated the relationships of psychological detachment and relaxation (b = − 0.10, 95% CI [− 0.18, − 0.02]), relaxation and mastery (b = − 0.13, 95% CI [− 0.25, − 0.02]), relaxation and control (b = − 0.12, 95% CI [− 0.23, − 0.01]), mastery and exhaustion (b = 0.11, 95% CI [0.01, 0.21]), and work engagement and exhaustion (b = 0.23, 95% CI [0.10, 0.35]), such that cross-sectional correlations were stronger and in the same direction as corresponding correlations from diary/post-respite designs. In addition, diary/post-respite study design moderated the relationships of psychological detachment and job performance (b = 0.22, 95% CI [0.03, 0.40]), such that cross-sectional correlations were in the opposite direction as corresponding correlations from diary/post-respite designs. In particular, the diary/post-respite design correlation was positive and significant (ρ = 0.21); however, the cross-sectional correlation was negative and non-significant (ρ = − 0.003). These results partially support hypothesis 3 (i.e., cross-sectional relationships will be larger than diary/post-respite relationships) as, for most correlations that were moderated, cross-sectional correlations were stronger than corresponding correlations from diary/post-respite designs (see Table 12).

For study location, we compared studies with European samples against studies with non-European samples. For the moderator variable, non-European was dummy coded as 0 and European as 1. In general, European studies have similar meta-analytic average correlations to non-European studies. Weighted least squares regressions revealed that European study location moderated only two correlations. European sample significantly moderated the relationship of psychological detachment with exhaustion (b = − 0.14, 95% CI [− 0.24, − 0.05]), such that the correlation was stronger and in the same direction in European samples than the corresponding correlation from non-European samples. Additionally, European sample significantly moderated the relationship of psychological detachment with job performance (b = 0.14, 95% CI [0.03, 0.26]) such that the average correlation was positive and statistically significant in European samples (psychological detachment-job performance: ρ = 0.11, p < 0.05), but was negative and non-significant in non-European studies (psychological detachment-job performance: ρ = − 0.04, ns).

Provided that European studies were more likely to utilize diary or post-respite designs, we ran weighted least squares multiple regressions for both the psychological detachment-exhaustion and psychological detachment-job performance relationships to further determine whether controlling for study design influenced the effect of study location. For the psychological detachment-exhaustion correlation, diary/post-respite design (b = 0.11, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.21) was not a significant moderator and European sample was a significant moderator (b = − 0.15, 95% CI [− 0.25, − 0.04]) when considered simultaneously. Similarly, for the psychological detachment-job performance correlation, diary/post-respite design (b = 0.14, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.29) was not a significant moderator and European sample was a significant moderator (b = 0.17, 95% CI [0.04, 0.29]) when considered simultaneously. In sum, these results partially support hypothesis 4 (i.e., relationships from European samples will be larger than relationships from non-European samples) as, of the correlations that were moderated, correlations from European samples were larger than corresponding correlations from non-European samples (see Table 12).

Within-Person Correlations Among Recovery Experiences

A within-person correlation is defined as the correlation between two variables measured on the same person across multiple occasions and is typically presented as an effect pooled (or averaged) across persons. Table 13 reports the within-person (day-level) meta-analytic correlations among recovery experiences. Far fewer studies reported within-person correlations compared to between-person correlations. For the within-person correlations among recovery experiences (Table 13), the four types of recovery experiences (psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control) are all significantly positively intercorrelated (i.e., all confidence intervals exclude zero), such that individuals who tend to experience one type of recovery experience at the day-level are also more likely to experience another. Comparing the within-person correlations (Table 13) against their corresponding between-person correlations (from Table 1), we see that the between-correlations are larger than the corresponding within-correlations [i.e., the between-vs.-within homology rescaling factor (i.e., “c parameter”; Chen et al., 2005) is ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 1.03–2.24 (see final column of Table 13)]. In other words, the recovery experiences are interrelated at the within-person level, but these relations are slightly stronger at the between-person level.

Within-Person Correlations of Recovery Experiences with Outcomes

Psychological Detachment

Table 14 reports the within-person meta-analytic associations between recovery experiences and outcomes for which sufficient data were available to meta-analyze (k ≥ 3 samples). Again, there were far fewer outcomes with enough samples to examine at the within-person level compared to the between-person level. Among the personal outcomes available, psychological detachment had significant within-person relationships with mood (positive affect ρwithin = 0.12; negative affect ρwithin = − 0.12), energy (exhaustion ρ = − 0.12; state recovery ρ = 0.17), sleep (sleep quality ρ = 0.11; sleep quantity ρ = 0.10), and health (well-being ρ = 0.49; stress ρ = − 0.29). Comparing these within-person correlations against their corresponding between-person correlations from Table 3 shows that these relationships are mostly in the same direction at the within-person and between-person levels. As shown in the final column of Table 14, the homology rescaling factor for these significant within-person relationships ranged from ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 1.17 to 4.0, except for stress (ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 0.66) and well-being (ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 0.49). This suggests that most between-person correlations were larger than their corresponding within-person correlations. However, for the relationships of psychological detachment between stress and well-being, these relationships tend to be larger at the within-person or day level. In addition, psychological detachment was more strongly and positively related to work outcomes at the day level: work engagement (ρ = 0.15; ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ − 0.07) and job performance (ρ = 0.13; ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 0.15).

Relaxation

At the within-person level, relaxation had significant relationships with mood (positive affect ρwithin = 0.23, negative affect ρwithin = − 0.17), exhaustion (ρwithin = − 0.19), and sleep quality (ρwithin = 0.15). In addition, relaxation had a significant relationship with work engagement at the within-person level (ρwithin = 0.15). The homology rescaling factor ranged from ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 1.35 to 2.00, suggesting relationships with relaxation were consistently larger at the between-person level.

Mastery

At the within-person level, mastery had a significant relationship with positive affect (ρwithin = 0.17), exhaustion (ρwithin = − 0.10), and sleep quality (ρwithin = 0.05). The homology rescaling factor ranged from ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ 1.76 to 3.40 for these correlations, suggesting relationships with mastery were consistently larger at the between-person level. Furthermore, although the relationship between mastery and negative affect was negative and significant at the between-person level (ρ = − 0.19), the relationship between mastery and negative affect was not significant and much smaller at the within-person level (ρwithin = 0.01; ρbetween/ρwithin ≈ − 19.00).

Control

At the within-person level, control had a significant relationship with exhaustion (ρwithin = − 0.22). This relationship with control is larger at the between-person level (ρbetween/ρwithin = 1.27).

In summary, in response to research question 2 (i.e., “Do the relationships among recovery experiences and personal and work outcomes significantly differ at the between-person vs. the within-person level of analysis?”), significant within-person correlations corresponded to larger between-person correlations in general among recovery experiences and for both personal and work outcomes (see Tables 13 and 14). However, for psychological detachment’s relationship with stress and well-being as well as job outcomes (i.e., work engagement and job performance), the significant within-person correlations corresponded to smaller rather than larger between-person correlations.

Publication Bias Analyses

Evidence for publication bias was analyzed with funnel plot and trim-and-fill techniques for all meta-analyses based on 10 or more primary study correlations (Kepes et al., 2012). Figures and results are available upon request from the first author. The funnel plot and trim-and-fill techniques interestingly suggest that publication-bias-corrected relationships of recovery experiences with outcomes might be slightly larger, rather than smaller, in magnitude. Consistent with this, Bennett et al. (2018)’s publication bias analyses in their meta-analysis of psychological detachment and relaxation with fatigue reached the same conclusion, and likewise Wendsche and Lohmann-Haislah (2017) found the relationships between psychological detachment and both sleep and neuroticism to be slightly larger after adjusting for publication bias. Our estimated publication-bias-adjusted correlations for psychological detachment-exhaustion (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.12), psychological detachment-sleep quality (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.04), psychological detachment-job performance (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.03), relaxation-negative affect (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.11), relaxation-work engagement (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.08), relaxation-job performance (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.02), mastery-negative affect (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.09), mastery exhaustion (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.05), mastery-sleep quality (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.05), mastery-work engagement (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.03), control-health complaints (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.04), and control-work engagement (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.02) are all the same sign but slightly larger in magnitude than the values presented in the result tables. Also, in contrast to the meta-analytic correlations involving recovery experiences, the exhaustion-job performance (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = 0.08) and exhaustion-health complaints relationships (Δ\(\overline{r}\) = − 0.09) demonstrated the expected attenuation of the meta-analytic correlation when correcting for publication bias.

Discussion

The primary goals of this study were (a) to clarify relationships of recovery experiences with both personal and job outcomes at both the between and within levels and (b) to propose and test a theoretical model extending the JD-R model, with two separate mechanisms linking recovery experiences to job performance and health outcomes. Results of meta-analytic regression reveal that psychological detachment experiences uniquely negatively predict work outcomes (i.e., work engagement, job performance, OCB, creativity), whereas relaxation (i.e., work engagement, job satisfaction) and mastery experiences (i.e., work engagement, job performance, OCB, creativity, job satisfaction) uniquely positively predict work outcomes. For personal outcomes, psychological detachment is the strongest (negative) predictor for the negative personal states (i.e., negative affect, exhaustion, work-family conflict), whereas the more positive personal states are predicted by relaxation (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction, well-being) and mastery (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction). In other words, psychological detachment is associated with decreasing negative personal states, whereas relaxation and mastery are associated with increasing positive personal states. Altogether, relaxation and mastery experiences predict stronger personal and job outcomes, whereas psychological detachment is a mixed blessing that reduces negative personal outcomes, but also might uniquely harm job outcomes after other recovery experiences are controlled.

Further, the available results involving recovery-outcome relations at the within-person level generally tend to be weaker than corresponding results at the between-person level of analysis. However, for psychological detachment’s relationship with stress and well-being as well as job outcomes (i.e., work engagement and job performance), the significant within-person correlations corresponded to smaller rather than larger between-person correlations. This suggests that psychological detachment may be more strongly related to stress and well-being as well as work engagement and performance when these variables are considered states rather than as stable variables. Future primary study research comparing such within- vs. between-person effects could be modeled after Chen et al. (2005) and Tay et al. (2014).

With regard to the theoretical mediation model, meta-analytic data are consistent with the proposed mechanisms. That is, results confirm that recovery experiences have indirect effects on job performance and health complaints, fully mediated through work engagement and exhaustion, respectively (see Fig. 1). Specifically, recovery experiences generally are positively associated with better job performance through enhancing work engagement, while they are negatively associated with health complaints through reducing exhaustion. In addition, we found detachment had a negative unique effect on work engagement and a negative indirect effect on job performance via engagement. However, this may be due to a statistical artifact given its high interrelation with the other recovery experiences. Also, we found that study designs moderated the observed effects, such that diary and post-respite studies of recovery exhibit smaller effects than do cross-sectional designs. In addition, study location moderated two relationships: psychological detachment-exhaustion and psychological detachment-job performance relationships were stronger in European samples compared to non-European samples. By taking stock of the current research base, the current meta-analysis offers several novel contributions, while highlighting areas that would benefit from additional research.

Theoretical and Research Implications of the Key Findings

Our findings advance the recovery literature in several ways. In line with previous empirical work, our meta-analysis suggests that people generally benefit from experiencing recovery during off-work times (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, control). In particular, the current study contributes to a better understanding of recovery by demonstrating that different recovery experiences have different unique relationships with important outcomes. For example, given that psychological detachment is associated with decreasing strain outcomes (i.e., negative affect, exhaustion, work-family conflict), the theoretical mechanism for psychological detachment may be most closely aligned with the ERM (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). According to the ERM, ceasing work-related effort expenditure is the key to reducing strain indicators, such as exhaustion or negative affect.