Abstract

Over two (i.e., a 2 × 2 experiment and a multi-source field study) studies, we propose and demonstrate how employees increase their emotional (i.e., affective commitment) and behavioral (i.e., citizenship behavior) investments in the workplace as a valuable outcome of the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness. We also explain how supervisory moral identity impacts the trickle-down effect. Notably, the research integrates social cognitive theory with the diversity and inclusion literature to enhance our understanding as to how organizations can create a welcoming environment for all organizational members. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The ongoing struggle for all organizational members, especially those from minority populations (e.g., women, ethnic minorities, LBGTQ individuals), to achieve success and feel welcomed in organizations has increasingly inspired scholars and practitioners to emphasize the importance of organizational inclusiveness (Shore et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2015). Whereas diversity focuses on actual demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, national origin, gender, sexual orientation), and “the varied perspectives and approaches to work that members of different identity groups bring” (Ely and Thomas 1996: 80), inclusion pushes organizations further, as it is described as the extent to which diverse individuals “are allowed to participate and are enabled to contribute fully” (Miller 1998, p. 151). Thus, inclusion has moved scholars and practitioners from solely focusing on the “what” and “who” to understanding the “how” and “why.”

Organizations run the risk of employee withdrawal and alienation when the importance of establishing an inclusive work environment is marginalized (Rice 2018). Indeed, a low level of inclusiveness can be disastrous for organizations via creating intragroup polarization (Nishii and Mayer 2009), increased turnover (Nishii 2013; Nishii and Mayer 2009; Wiersema and Bird 1993), heightened interpersonal conflict (Jehn et al. 1999), and reduced group cohesion and communication (O’Reilly et al. 1989). Conversely, research has demonstrated that organizational members’ perceptions of inclusiveness positively impacts performance, job satisfaction, trust, and engagement (Acquavita et al. 2009; Avery et al. 2008; Cho and Mor Barak 2008; Downey et al. 2015; Nishii 2013). Thus, creating an environment where diverse individuals feel welcomed and included has become a central concern for many organizations (Bilimoria et al. 2008; Roberson 2006).

It is likely that effectively disseminating organizational inclusiveness across the organization also improves the degree to which employees invest emotionally (i.e., affective commitment) and behaviorally (i.e., going above and beyond their formal job duties—citizenship behavior) into the organization. Notably, a heightened level of employee commitment and citizenship behavior enhances the work environment (Lambert 2000; Zhao et al. 2013). However, organizational leaders are tasked with the role of communicating and demonstrating the importance of inclusiveness in their respective organizations, as their conduct can saliently convey a sense of inclusion (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006). Direct supervisors are frequently the principal organizational leaders determining access to rewards and opportunities for subordinates (Douglas et al. 2003). Thus, direct supervisors play a critical role as key agents of the organization through which members form their judgments (e.g., inclusiveness) of the organization (Liden et al. 2004). As such, we propose that organizational inclusiveness has the ability to trickle down from the broader organizational level to the employee level, but the key in the transmission of organizational inclusiveness rests with organizational leaders at the supervisory level.

We aim to make several contributions. First, we propose and demonstrate the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness. By relying on the social cognitive theory we offer novel theoretical insights that explain the process by which inclusiveness traverses multiple organizational levels and allows us to break away from traditional diversity theories (Riordan 2000; Shore et al. 2010; Theodorakopoulos and Budhwar 2015; Umphress et al. 2007). Thus, we conceptualize inclusiveness at the supervisory level as a form of modeling resulting from inclusiveness at the broader organizational level.

Second, we explain and demonstrate the moderating impact of supervisory moral identity on the trickle-down effect. Social cognitive research has noted that both organizational factors and individual differences impact the conduct of individuals (Aquino and Reed 2002; Bandura 1986; Blasi 1993; Mayer et al. 2009, 2012). We propose that supervisors who possess a high level of moral identity should demonstrate a level of consistency in terms of their inclusive behavior. In other words, irrespective of the level to which an organization is inclusive, a supervisor who possesses a high level of moral identity will express the same high level of inclusiveness, as being inclusive is central to the supervisor’s self-concept of being a moral person. The supervisor should exhibit a certain level of regularity and situational factors should not change his/her inclusive behaviors. However, when a supervisor possesses a low level of moral identity, his/her inclusive behaviors are more reliant on contextual cues and may increase as an organization becomes more inclusive. As such, we identify supervisors’ moral identity as a key moderator to this effect, which prior research has yet to examine.

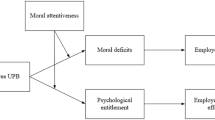

Third, we demonstrate that organizational inclusiveness trickles down to positively impact subordinates’ inclusiveness-related behavior and attitudes through supervisory inclusiveness. We targeted citizenship behavior and commitment as the subordinate-level inclusion-related outcomes because they convey a sense of organizational unity and inclusion (Eisenberger et al. 1990; Katz 1964; Shore et al. 2010). As shown in Fig. 1, we comprehensively examine and explain the significant interaction between a situational feature (i.e., organizational inclusiveness) and an individual difference (i.e., supervisory moral identity) as factors relevant to supervisors promoting a welcoming experience that triggers significant employee investments within the organization.

Although supervisors are essential to conveying a sense of inclusiveness to other organizational members, little research has examined the underlying psychological processes that can prompt a supervisor to promote organizational inclusion efforts. This may be partly attributed to the focus on diversity theoretical frameworks typically cited when exploring inclusion (e.g., relational demography, attraction-similarity; Riordan 2000; Shore et al. 2010; Theodorakopoulos and Budhwar 2015; Umphress et al. 2007). While these theories provide valuable insights, they tend to focus more on how organizations can diversify their workforce and what can be done to increase the number of minorities, as opposed to how organizational inclusiveness can be transferred across multiple levels within organizations, which ultimately enhances the work environment among all organizational members. While this literature remains relevant, understanding the role that organizational leadership plays with respect to the dissemination of organizational inclusiveness can further our understanding of how organizations can increase their level of inclusiveness.

Theory and hypothesis development

Supervisory inclusiveness: a modeling byproduct of organizational inclusiveness

A growing body of research suggests that supervisors are likely to see themselves as extensions of their organizations (Liden et al. 2004; Mayer et al. 2009). As agents of the organization, supervisors are prone to emulate and convey the values and conduct displayed within their employing organizations (Mawritz et al. 2012; Mayer et al. 2009). Drawing on Bandura’s (1977, 1986) social cognitive theory, these scholars have collectively reasoned that this process occurs because supervisors value and learn to model the conduct of a credible entity. That is, supervisors look for cues from their employer regarding acceptable conduct within their organization. Given that role modeling conveys the values and conduct that are important to the organization (Grojean et al. 2004; Shore et al. 2010), we propose that if supervisors are employed by inclusive organizations, then they can be expected to disseminate and demonstrate inclusiveness toward their subordinates.

Research suggests that organizational inclusiveness can be evaluated based upon the policies, practices, and procedures that implicitly and explicitly communicate the extent to which fostering and maintaining diversity and eliminating discrimination are priorities to the organization (Pugh et al. 2008). This type of inclusiveness entails organizations engaging in efforts to involve all employees in the mission and operation of the organization with respect to their individual talents (Avery et al. 2008), remove hurdles to the full participation and contribution of employees in the organization (Roberson 2006), and frequently elicit and value contributions from all employees (Lirio et al. 2008).

Thomas and Ely (2001) proposed that organizational inclusiveness entails organizations adopting a learning and integration perspective, which is characterized by the belief that individuals’ diverse backgrounds are a source of insight that should be utilized to adapt and improve the organizations’ strategic tasks. Consistent with their description of organizational inclusiveness, we propose that supervisory inclusiveness entails supervisors adopting a learning and integration perspective that views individuals’ diverse backgrounds as an asset to the successful implementation of the organizations’ strategic tasks. This particular learning and integration perspective implies that inclusiveness can be viewed as a psychological process that entails integrating and demonstrating what one has learned or observed from credible entities. Considering the above, supervisors—who are considered credible entities representative of the organization—may transmit organizational inclusiveness to lower-level employees via a trick-down effect, as suggested by the social cognitive theoretical perspective.

The fundamental premise of social cognitive theory is that lower-level employees emulate management conduct and salient organizational cues (Bandura 1986). As such, the trickle-down effect occurs through the process of role-modeling, and due to organizational rewards and punishment systems, broader organizational perceptions, attitudes, and behavior are likely to be positively related to supervisory perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors (Ambrose et al. 2013; Mawritz et al. 2012; Mayer et al. 2009; Ruiz et al. 2011). Indeed, trickle-down effects have been noted throughout the ethics literature.

While drawing on social cognitive theory, Ambrose and her colleagues (2013) demonstrated that supervisors’ perceptions of interactional fairness trickled down to influence their workgroup perceptions of interactional fairness. Similarly, Mayer and his colleagues (Mayer et al. 2009) revealed that ethical leadership from the upper level in the organization trickled down to impact followers’ behaviors and attitudes via ethical leadership at the supervisory level. Another study, conducted by Mawritz and her colleagues (Mawritz et al. 2012), demonstrated that abusive behavior at the upper management level impacted deviant behavior two hierarchal levels lower through abusive behavior at the supervisory level. The underlying rationale for these studies was that people (e.g., supervisors) learn through modeling the observable social cues (e.g., organizational values, philosophy, behaviors, displayed acts, attitudes, etc.) of credible entities (e.g., employers). Taken together, we hypothesize that a positive relationship exists between organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness.

-

Hypothesis 1: Organizational inclusiveness (i.e., evaluated by supervisors) is positively related to supervisory inclusiveness (i.e., evaluated by subordinates).

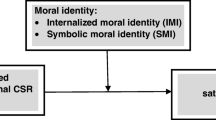

The moderating role of supervisory moral identity

Although we propose that inclusiveness at the broader organizational level should trickle down to the supervisory level, it is important to note (vis-á-vis social cognitive research) that some supervisors may generally promote and display a certain level of inclusiveness due to their own sense of right and wrong (Aquino and Reed 2002; Reed and Aquino 2003), not necessarily due to the situational cue of organizational inclusiveness. To explain why this is likely to occur, we targeted supervisory moral identity as a moderator regarding this particular trickle-down effect.

While it may initially seem that supervisory moral identity should strengthen the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness on supervisory inclusiveness due to organizational inclusiveness serving as a prompt for morally upright supervisors to be even more inclusive, we argue somewhat counterintuitively, that supervisory moral identity (i.e., at higher levels) weakens the relationship. Our rationale is based upon the nature of moral identity and how it is characterized in social cognitive research. Moral identity has been described as a self-schema organized around a set of moral trait associations (e.g., honest, caring, compassionate; Aquino and Reed 2002). It also operates as a self-regulatory mechanism that motivates moral action (Blasi 1984, 1993). Like other individual differences and personality traits, moral identity exerts varying levels of impact on an individual’s self-concept (Markus and Kunda 1986). Moral identity is rooted in the very core of one’s being and integrity (Reed and Aquino 2003), as opposed to it being a characteristic that is a prompted due to a situational cue. As such, regardless of the extent to which an organization is inclusive, a supervisor who possesses a high level of moral identity will display the same high level of inclusiveness, because being inclusive is part of this supervisor’s self-concept of being a moral person. The supervisor should demonstrate a certain level of consistency and the situation should not change his/her inclusive behaviors. However, when a supervisor possesses a lower level of moral identity, his/her inclusive behaviors are more dependent on external cues and may increase as an organization becomes more inclusive.

In their investigation of how specific factors affect moral conduct, Aquino et al. (2009) found that people with strong moral identities were more likely to behave morally and justly. This type of moral conduct included acts that demonstrated care, compassion, and fairness toward others. Consequently, it is likely that supervisors with strong moral identities are not necessarily modeling the cue of inclusiveness from their employers, but rather they are psychologically affirming their moral identity by displaying inclusiveness. Our rationale is that if inclusiveness entails demonstrating a concern for others’ points of views, distributing resources fairly, removing obstacles that could inhibit full participation, and making employees feel valued (e.g., Lirio et al. 2008; Roberson 2006; Shore et al. 2010), then this type of conduct shares many of the aspects that are commonly associated with “what it means” to be a moral person (i.e., moral identity internalization) and the right way to treat others (i.e., moral identity symbolization) (Aquino and Reed 2002). Consequently, supervisors with strong moral identities are likely to deem treating people considerately, and valuing others’ inputs as important to their self-identities. As such, these supervisors can be expected to be a welcoming presence across varying situations (Shao et al. 2008), rendering the situational cue of being employed by an inclusive organization less of a factor to their inclusive behavior.

Additionally, regarding issues rooted in diversity and inclusion, scholars have demonstrated that individuals who possess a high level of moral identity tend to possess a significant amount of moral regard or cognitive awareness toward the plight of out-group members (e.g., typically minority classes) and more favorable attitudes toward relief efforts (e.g., elimination of barriers to inclusion) to aid out-group members (Harrison et al. 1998; Reed and Aquino 2003). Furthermore, recent research suggests that moral identity has prescriptive and proscriptive mechanisms (Boegershausen et al. 2015). We also argue that supervisory inclusiveness entails both prescriptive moral self-regulation (i.e., demonstrating behavior that one thinks is required) and proscriptive moral self-regulation (i.e., avoiding behavior that one thinks is forbidden). Distinctly, inclusiveness entails being welcoming (demonstrating proper conduct) and not being discriminatory (avoiding inappropriate conduct). As such, supervisors who possess a high level of moral identity should view being inclusive as a matter of it being important to their identity, which mitigates the influence of being impacted by varying levels of organizational inclusiveness. Taken together, this suggests that supervisory moral identity should weaken the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness.

-

Hypothesis 2: The positive relationship between organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness will be weaker when supervisory moral identity is high.

Inclusiveness at the subordinate level

Social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986) can also help to explain why the trickle-down effect ultimately impacts subordinate behavior and attitudes that convey their own sense of inclusion. Citizenship behavior and commitment are typical ways that subordinates respond to the extent that they feel involved and enjoy full membership within an organization, resulting in an emotional attachment to the organization (Allen and Meyer 1990; Colquitt et al. 2001; Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Eisenberger et al. 1986; Konovsky and Pugh 1994; Mayer et al. 2009; Shanock and Eisenberger 2006). Our research suggests that organizational inclusiveness will also trickle down to the subordinate level. Therefore, citizenship behavior and affective commitment should be representative of an inclusion-related behavior and inclusion-related attitude, respectively. This further demonstrates the cascading dissemination of organizational inclusiveness across levels of the organization.

As a unique type of behavioral investment within the organization, citizenship behaviors entail going above one’s job description to help others feel a sense of unity and inclusion (Shore et al. 2010). These types of behaviors include helping out at the interpersonal and organizational levels. As a distinct type of emotional investment within the organization, affective commitment conveys a sense of belonging and emotional attachment to one’s employer, which is also an essential dimension of feeling included (Shore et al. 2010). Due to shared attachments and the conceptual linkage between inclusion and commitment, Shore and her colleagues noted that commitment should be an outcome of inclusion. Additionally, Cho and Mor Barak (2008) found that a positive relationship exists between inclusion and commitment. Consistent with our earlier theorizing, organizational inclusiveness should positively impact subordinate citizenship and commitment through a trickle-down model. That is, we believe these effects are transmitted through supervisory inclusiveness.

In all, we propose a first-stage moderated mediation effect. Specifically, the conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on subordinate citizenship behavior and commitment through supervisory inclusiveness will be weaker when supervisors possess strong moral identities.

-

Hypothesis 3a: The relationship between organizational inclusiveness and subordinate citizenship behavior is mediated by supervisory inclusiveness.

-

Hypothesis 3b: The conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on subordinate citizenship behavior through supervisory inclusiveness will be weaker when supervisors possess strong moral identities.

-

Hypothesis 4a: The relationship between organizational inclusiveness and subordinate commitment is mediated by supervisory inclusiveness.

-

Hypothesis 4b: The conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on subordinate commitment through supervisory inclusiveness will be weaker when supervisors possess strong moral identities.

Overview of studies

We relied on two distinct research designs to test our hypotheses. As such, our methods, analysis, and results are presented separately as Study 1 and Study 2.

Study 1 method

In Study 1, we used a 2 × 2 experiment (1) to provide evidence of the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness from a broader organizational level to the supervisory level and (2) to examine the moderating role of supervisory moral identity. Experimentalists argue that this type of research design can be utilized to assess how individuals use and combine available information when making evaluative judgments (Aguinis and Bradley 2014; Karren and Barringer 2002), such as supervisory inclusiveness. Participants assess a series of scenarios where cues (i.e., key pieces of information) are manipulated. Accordingly, the experimental manipulation of cues (e.g., organizational inclusiveness) can clarify the causal nature of our hypothesized trickle-down effect. Furthermore, this type of experimental methodology allows for an implicit assessment of respondent values, thereby reducing the concern of social desirability bias found with more direct measurement approaches, such as survey data. Given these distinct strengths, researchers have used this type of research methodology to assess individuals’ judgment regarding other inclusion-relevant organizational topics (Karren and Barringer 2002; Nicklin et al. 2011; Rousseau and Anton 1991; York 1989).

Participants and procedure

Study 1 participants were 61 undergraduate business students at a large southeastern university. The sample demographics were 48% female, 45% working adults, and 47% percent self-identified as minorities. The average age of a participant was 22.41 (SD = 2.36) years old. Participants assumed the role of a manager evaluator responsible for succession management and evaluations of manager inclusiveness. They were provided with 360-degree evaluations of six mid-level managers (i.e., the participants were informed that the managerial profiles were based upon evaluations provided by the managers’ superiors, peers, and subordinates). Manager profiles were presented in a randomized order to control for order effects. The profiles contained information regarding four key pieces of information. The first critical piece was a rating of the TMT (Top Management Team) organizational inclusion initiatives (i.e., organizational inclusiveness). The other three ratings were descriptions of competencies for each manager under review: the manager’s characteristics (i.e., moral identity), talent utilization, and problem-solving skills. Given our interest in and predictions about organizational inclusiveness and supervisory moral identity, only these two characteristics were manipulated (i.e., strength/weakness) across the manager profiles of specific interest. The other cues were held constant and clearly marked in the moderate range. Manager talent utilization and problem-solving skills were included in an effort to reduce the participants from focusing solely on our manipulations.

Four profiles were fully manipulated. Thus, we used a 2 (strength vs. weakness, organizational inclusiveness) × 2 (strength vs. weakness, supervisory moral identity) design. To account for the possibility of demand characteristics, we included one control profile wherein organizational inclusiveness and supervisory moral identity levels were moderate, talent utilization was given a low score, and problem-solving skill was given a high score. Additionally, the order of presentation of the managerial profiles was randomized. We also included a duplicate profile (i.e., a sixth profile) of a weak rating for organizational inclusiveness and a strong rating of supervisory moral identity. Rater reliability is frequently a potential weakness of experimental studies (Aiman-Smith et al. 2002). Nonetheless, the reported means between our manipulated condition (M = 2.47) and its duplicate condition (M = 2.41) regarding supervisory inclusiveness were not statistically different. Therefore, rater reliability was consistent. Notably, responses to the control profile and duplicate profile were removed prior to analysis (Aiman-Smith et al. 2002). It is important to note that we used the Durbin-Watson test to examine the presence of auto-correlation. In experimental research, auto-correlation can be problematic in interpreting findings. The value lies between 0 and 4 (Durbin and Watson 1971). If the d-statistic is significantly less than 2, then evidence of positive serial correlation exists. If the d-statistic is significantly more than 2, then evidence of negative serial correlation exists. A value of 2 suggests autocorrelation is not present. The Durbin-Watson was 2.27. Thus, the presence of auto-correlation appears to be absent from the data (Gujarati 2003). This suggests that our analyses were based on 244 distinct observations (61 participants × 4 profile ratings).

Experimental designs and manipulations

Appendix A includes one manager profile as a sample. Within each 360-degree managerial profile (i.e., the participants were informed that the managerial profiles were based upon evaluations of the managers’ superiors, peers, and subordinates), both descriptive and numerical ratings (i.e., cues) were provided for each of the hypothetical manager’s assessed characteristics. In line with Aiman-Smith et al.’s (2002) prescriptions, we supplemented written information with graphical depictions of the cue levels. In each of the 6 profiles, we specifically manipulated organizational inclusiveness and supervisory moral identity with various cues: (i) percentile scores, where values (on a 1–100 scale) indicated how a leader scored relative to other mid-level managers; (ii) graphics (i.e., bar charts and tables); and (iii) color, such that green signaled strength and red indicated weakness of each rating. In the high organizational inclusiveness condition, TMT organizational inclusion initiatives were scored at the 92nd or 94th percentile out of 100 (minor variations were included to prevent participants from cuing in on identical manager scores across profiles). The TMT organizational inclusion initiatives items were “removes obstacles to the full participation and contribution for employees (Roberson 2006),” “engages in efforts to involve all employees in departmental operations (Avery et al. 2008),” and “diverse individuals are allowed to participate and enabled to contribute fully (Miller 1998),” and were noted as distinct strengths. In the low organizational inclusiveness condition, TMT inclusion items were scored at the 32nd or 35th percentile, and the items were marked as weaknesses.

Supervisory moral identity was similarly manipulated. It is important to note that due to our experimental research design, our manipulation may be considered as a proxy for moral identity symbolization, as it is described as characteristics that are demonstrated. Moral identity symbolization is the extent that an individual demonstrates their possession of moral traits through moral action (Aquino and Reed 2002). In the strong supervisory moral identity condition, manager characteristics were rated 87 or 88 out of 100, and the four supervisory moral identity indicators, which were “shows compassion,” “demonstrates fairness,” “exhibits generosity,” and “displays helpfulness (operationalized per Aquino and Reed 2002),” were rated as strengths. In the weak supervisory moral identity condition, the moral indicators were rated at 29 or 34 out of 100, and each indicator was rated as a weakness.

We conducted manipulation checks to ensure that our selection of values was representative of how participants would interpret values that correlate with high and low and strong and weak levels of the variables. In each profile, regarding organizational inclusiveness, participants responded to the following item (5-point Likert, 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree): “This manager’s upper management shows that being inclusive is important.” One-way ANOVA revealed that participants indicated a higher level of organizational inclusiveness in the high conditions (M = 4.89) than in the low conditions (M = 1.37), t (60) = 284.07, p < .01, both being significantly different statistically from the control condition (M = 3.48). Similarly, participants indicated a higher level of supervisory moral identity in strong conditions (M = 4.22) than in the weak conditions (M = 1.80), t (67) = 278.43, p < .01, both being significantly different statistically from the control condition (M = 3.70). The supervisory moral identity manipulation check scale-item (five-point Likert agreement scale) was “This manager seems to be a moral person.” Based on this check we confirmed that participants accurately interpreted the manipulated profiles. This manipulation check item was included in each profile.

Measures

Supervisor inclusiveness was assessed by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) a modified four-item organizational inclusiveness climate measure developed by Pugh and his colleagues (Pugh et al. 2008). The modification was a referent shift to focus exclusively on the manager. As such, sample items included “This manager is likely to make it easy for people from diverse backgrounds to fit in and be accepted” and “This manager is likely to demonstrate through his/her actions that he/she wants to hire and retain a diverse workforce.” The Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Study 1 results

We used ANOVA to examine the mean differences among the various groupings of managerial profiles. Hypothesis 1 stated that organizational inclusiveness should have a positive impact on supervisory inclusiveness. One-way ANOVA revealed that managers in the high condition of organizational inclusiveness were rated higher on supervisory inclusiveness (M = 3.95, SD = .72) t (242) = 299.53, p < .01 than managers in the low condition (M = 2.10, SD = .93). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 was tested using PROCESS (Hayes 2013). This hypothesis predicted that the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness will be weaker when supervisory moral identity is strong. The data revealed a significant and negative interaction between organizational inclusiveness and supervisory moral identity (β = − .11, p < .05). The impact of organizational inclusiveness on supervisory inclusiveness was weaker when supervisory moral identity was high. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was also supported. Figure 2 depicts the interaction effect.

Study 1 discussion

First, this experimental study demonstrates the effect of organizational inclusiveness on supervisory inclusiveness. Supervisors were expected to model inclusiveness if employed by inclusive organizations. A key issue with past social-cognitive research is that it is primarily survey-based and cross-sectional (e.g., Mayer et al. 2009; Mawritz et al. 2012). Second, we identify supervisory moral identity as an important moderator of this particular trickle-down effect. Recently, social cognitive theorists (Mawritz et al. 2012) have noted the importance of identifying boundary conditions of trickle-down effects. The trickle-down effect was weaker for supervisors with stronger moral identities. Third, this particular type of experimental vignette methodology reduced the impact of social desirability effects by indirectly evaluating the significance of explanatory variables and thus, is considered superior to the self-report survey method (Arnold and Feldman 1981; Bretz and Judge 1994). Fourth, by experimentally manipulating cue values we methodologically diminished variable intercorrelations and the issue of multicollinearity, which are frequently found in field data, and increased the ability to gage the independent effects of cues (e.g., Karren and Barringer 2002; Feldman and Arnold 1978).

As with any study, Study 1 has limitations. First, it was an indirect test of social cognitive theory. Unlike the traditional supervisor-subordinate dyadic approach, we cannot definitively say we captured the internal psychological processes that typically underlie social cognitive research. However, past research has utilized experimental simulations to illustrate an indirect but expected impact of trickle-down effects (e.g., Doyle et al. 2002). In general, individuals are expected to model the conduct of credible entities relevant to those particular persons (Bandura 1977). Second, the moderator was also indirectly measured. Despite the manipulation checks and data demonstrating that supervisory moral identity moderated the illustrated trickle-down effect, the supervisory moral identity scores were experimentally constructed and operated as a proxy for moral identity symbolization. As such, because a supervisor did not rate his or her own moral identity, we cannot undoubtedly say that supervisory moral identity was a direct operationalization of the construct. Nonetheless, this manipulation avoids the positive bias of self-rating and considers the unlikelihood that a supervisor would self-report themselves low on a morality scale. A third limitation of Study 1 is the issue of realism, which is inherent in any experiment. Although our manipulation checks and findings suggest that we tested our hypotheses, we relied on hypothetical scenarios. However, given the sensitive topic of inclusion, an indirect assessment of variables is a way to mitigate social desirability bias. A fourth limitation of Study 1 is that all of our manipulated conditions did not have duplicate conditions. Consequently, we cannot entirely eliminate the concern of rater reliability. In an effort to reduce this concern, we replicated 25% percent of our manipulated conditions, when in accordance with Cable and Judge (1994), only a small percentage (i.e., 12%) is needed to ease the concern of rater reliability. A final limitation is that the manipulation checks were included in each profile. We did this to ensure a level of uniformity, however, it is possible that it potentially cued the respondents to the nature of the study.

Study 2 method

Sample and procedure

Study 2 was designed to serve as a constructive replication (Lykken 1968) and extension of Study 1. Additionally, Study 2 was designed to overcome the key limitations of Study 1. Subsequently, Study 2 complements Study 1 by offering a more direct assessment of our proposed model and reduces the concern of experimental realism. As such, we collected data from immediate supervisors and their direct reports (i.e., dyads) from various businesses and organizations located in the southeastern United States. A variety of industries (e.g., accounting, banking, education, food services, manufacturing, retail, hospitality, and social services) were represented. We administered surveys to working adults via the Internet through the Qualtrics software. The focal employee (i.e., subordinate-level) was responsible for completing his or her survey and then asked his or her immediate supervisor to complete the respective supervisor questionnaire. This data collection approach was in line with previous management research (e.g., Letwin et al. 2016; Mayer et al. 2009; Piccolo et al. 2010; Skarlicki and Folger 1997).

Consistent with prior research (Mayer et al. 2009, 2012), we took a number of steps to ensure that the surveys were completed by the correct sources. First, we stressed the significance of integrity in the research process. Second, time stamps and IP addresses were recorded and verified to see if they were submitted at different times and on different computers. Of the 316 participants invited to participate and have the opportunity to receive extra credit for their participation, we received completed surveys from 206 direct reports and 188 immediate supervisors. After eliminating incomplete and suspicious data (e.g., failing to correctly mark instructionally directed responses embedded within the survey), we had 121 usable subordinate-supervisor dyads or a total of distinct 242 participants.

Subordinate respondents were 44% male. These respondents were 68% Caucasian, 16% Hispanic American, 8% African American, 4% Asian American, and 4% other. On average, subordinates were 25 years old (SD = 7.23) and had approximately 4 years of experience with their organization (SD = 3.80). Supervisor participants were 43% female. Supervisors were 65% Caucasian, 18% Hispanic American, 10% African American, 2% Asian American, 1% Native American, and 4% other. Supervisors, on average, were 38 years old (SD = 11.79) and had an average of 8 years of organizational tenure (SD = 5.82).

The subordinate survey contained measures of supervisory inclusiveness, affective commitment, trait cynicism, and demographics. The supervisor survey contained measures of organizational inclusiveness, moral identity, subordinates’ citizenship behaviors, and demographics. In line with Becker’s (2005) recommendations, we controlled for the effects of ethnic similarity and gender similarity within the dyads, organizational tenure at both levels, and subordinate cynicism in an effort to account for alternative explanations, as these variables can impact diversity-related issues (Bacharach et al. 2005; Dean et al. 1998; Elvira and Cohen 2001). For example, Bacharach and colleagues noted (Bacharach et al. 2005) that there is a tendency for similar individuals to associate more than dissimilar individuals. Additionally, research also suggests that cynical individuals are likely to believe that people do not care about diversity and inclusion matters (Dean et al. 1998), but it is portrayed in a way to conceal ulterior motives.

Measures

All ratings were made on a scale ranging from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 7, “strongly agree.”

Organizational/supervisory inclusiveness

Similar to Study 1, we used a modified version of the organizational inclusive climate scale (Pugh et al. 2008). Again, the referent shift in the wording directed supervisors to focus on their organization, whereas the referent shift in the wording directed subordinates to focus on their supervisor. Subsequently, sample items from the supervisor survey included “My organization demonstrates through its actions that it wants to hire and retain a diverse workforce” and “My organization makes it easy for people from diverse backgrounds to fit in and be accepted.” However, sample items in the subordinate survey included “My supervisor demonstrates through his or her actions that he or she wants to hire and retain a diverse workforce” and “My supervisor makes it easy for people from diverse backgrounds to fit in and be accepted.”

Moral identity

Moral identity was measured using Aquino and Reed’s (2002) 10-item scale. Supervisors responded to the following scenario: “Caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind. The person with these characteristics could be you or it could be someone else. For a moment, visualize in your mind the kind of person who has these characteristics. Imagine how that person would think, feel, and act. When you have a clear image of what this person would be like, answer the following questions.” Accordingly, supervisors responded to sample items such as “I strongly desire to have these characteristics” and “Being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am.”

Citizenship behavior

A 12-item scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991) measured subordinates’ citizenship behavior. Sample items included “This employee generally helps others who have heavy workloads,” and “This employee goes out of his/her way to help new employees.”

Affective commitment

A three-item scale developed by Meyer et al. (1993) measured affective commitment. Sample items included “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization,” and “I enjoy discussing my organization with people outside of it.”

Trait cynicism

A five-item version of Wrightsman’s Cynicism Subscale (Wrightsman 1974) measured trait cynicism. Sample items included “Most people inwardly dislike putting themselves out to help other people,” and “People pretend to care about one another more than they really do.”

Study 2 data analysis and results

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities can be found in Table 1.

Prior to our data analyses, we utilized LISREL (Jöreskog and Sörbom 2006) to perform confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to demonstrate variable uniqueness and measure model fit. Regarding our conceptualized model, the CFA results suggested that our full five-factor model fit the data adequately (x2 = 1121.74; df = 517; CFI = .90; IFI = .90; RMSEA = .09; SRMSR = .11; Hox 2002; Jöreskog and Sörbom 2006). Notably, our theorized model was superior to several alternative models. The alternative models included a four-factor model that combined organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness (x2 = 1495.96; df = 521; CFI = .82; IFI = .82; RMSEA = .14; SRMSR = .15); a four-factor model that combined supervisory inclusiveness and supervisory moral identity (x2 = 1392.92; df = 521; CFI = .83; IFI = .83; RMSEA = .14; SRMSR = .12); a four-factor model that combined subordinate citizenship behaviors and commitment (x2 = 1356.40; df = 521; CFI = .82; IFI = .83; RMSEA = .14; SRMSR = .14); and a three-factor model that combined (1) organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness and (2) subordinate citizenship behavior and commitment (x2 = 1729.75; df = 524; CFI = .77; IFI = .77; RMSEA = .15; SRMSR = .16).

In testing all of our hypotheses, we conducted analyses with and without control variables (Becker 2005; Becker et al. 2016). Following Becker’s (2005) recommendation, we report the results of the analyses without the control variables, because if the results are similar (i.e., same conclusions can be drawn from the data) then concern regarding control variables as alternative explanations is reduced.

Hypothesis 1 was tested using simple regression. The relationship between organizational inclusiveness (i.e., supervisor-rated) and supervisory inclusiveness (i.e., subordinate-rated) was positive and significant (β = .34, p < .01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Table 2 shows the regression results. We utilized the SPSS PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2013) to test the remaining hypotheses. Hypothesis 2 predicted that the positive relationship between organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness would be weaker when supervisors possessed strong moral identities. The results revealed a significant and negative interaction between organizational inclusiveness and supervisory moral identities (B = − .27, p < .01). Figure 3 depicts the moderating effect of moral identity. When supervisors possessed strong moral identities, the impact of organizational inclusiveness was weaker. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Hypotheses 3a and 4a tested mediation via indirect effects. The results of our analyses revealed a significant indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on subordinate citizenship behavior (standardized boot indirect effect = .07, LCI = .02, UCI = .17) and commitment (standardized boot indirect effect = .12, LCI = .04, UCI = .25) through supervisory inclusiveness. Thus, hypotheses 3a and 4a were supported (Table 3). The complementary path analyses provided in Table 4 provides additional support for mediation. Hypotheses 3b and 4b proposed that the conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on citizenship behavior and commitment via supervisory inclusiveness would be weaker when supervisory moral identity is higher. The data revealed that at a higher level of supervisory moral identity, the conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on citizenship and commitment was non-existent. However, at a lower level of supervisory moral identity, the conditional indirect effect of organizational inclusiveness on citizenship behavior and commitment was present. Notably, zero only appears in the confidence intervals when supervisory moral identity is higher, which suggests first-stage moderated mediation. As a result, hypotheses 3b and 4b were supported. Table 4 provides evidence of mediation and Table 5 provides evidence of moderated-mediation. Using Edwards and Lambert (2007) methodology (i.e., first-stage moderation mediation equation), we provide graphical support for hypotheses 3b and 4b. Figures 4 and 5 depict the results using their methodology.

Study 2 discussion

In Study 2, we were able to replicate and extend the results from Study 1 in a field setting, which is a more direct test of our model. Study 2 demonstrated that organizational inclusiveness trickles down from the broader organizational level to the lower supervisory level. Second, we captured multi-source data, as supervisors rated organizational inclusiveness and subordinates rated supervisory inclusiveness. It is important to note that our third-party supervisor evaluators were their respective direct reports, which is consistent with prior social cognitive research (Mawritz et al. 2012; Mayer et al. 2009). Third, we showed again that supervisory moral identity moderates this particular trickle-down effect, which may suggest an important boundary condition to this social cognitive process. That is, certain supervisors (i.e., those with highly self-important moral identities) display inclusiveness in general, thereby reducing the need to observe or be employed by inclusive organizations. Fourth, we demonstrated that supervisory inclusiveness mediates the relationship between organizational inclusiveness and important organizational outcomes (i.e., citizenship behavior and commitment). Thus, inclusiveness at higher levels of the organization can positively impact lower levels of the organization via supervisory inclusiveness. Fifth, our sample represented a wide variety of organizations and industries, enhancing our confidence in the generalizability of these effects.

Although Study 2 overcomes some of the limitations of Study 1, Study 2 also has some limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional. Consequently, we cannot rule out the issue of reverse causality. Nonetheless, the predominant thought in social cognitive research is trickle-down effects (e.g., Mawritz et al. 2012; Mayer et al. 2009), not necessarily trickle-up effects. Additionally, the experimental research design of Study 1 complements the findings of Study 2 and increases our confidence in the results. Second, Study 2 may be positively biased, as subordinates are likely to seek out supervisors they have good rapport with to participant in research projects (Piccolo et al. 2010). To combat this, we took steps to ensure participants that their answers would be confidential (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

General discussion

Theoretical contributions

The present research has various theoretical contributions to the diversity and inclusion, social cognition, and leadership literatures. First, non-traditional diversity and inclusion theories can offer unique insights regarding organizational inclusiveness. Specifically, social cognitive theory provided a framework to explore how the dissemination of organizational inclusiveness can indeed traverse multiple levels. Second, this particular theory also allows us to incorporate the recent psychosocial mechanism associated with more recent conceptualizations of organizational inclusion (e.g., Shore et al. 2010). Third, our social cognitive approach facilitated the integration of Thomas’ and Ely (2001) learning and integration perspective of organizational inclusiveness and supervisory inclusiveness, which enhanced our understanding of what can prompt leaders to be allies to organizational efforts to creating a welcoming environment for all organizational members. Consequently, the results of Study 1 and Study 2 reliably demonstrate that organizational inclusiveness is a strong predictor of supervisory inclusiveness.

Another contribution is that we have a greater understanding of how supervisory moral identity also plays a significant role as a boundary condition for this particular trickle-down effect. Rooted in a social cognitive approach to inclusion, supervisory inclusiveness can also be triggered when supervisors care about their subordinates and the right way to treat others is important to their self-concept. Although diversity and inclusion research can be dominated at times by demographic features, the concept of inclusion is likely to have moral implications as well. As noted earlier, conceptual linkages exist between what it means to be inclusive and what it means to be a moral person. For this purpose, it is important to understand the relationship between morality and inclusion. This can enhance and broaden our understanding of what types of leaders display inclusiveness.

Finally, organizational inclusiveness can traverse multiple levels and impact subordinate-level outcomes, such as commitment and citizenship behavior, through supervisory inclusiveness. Stated differently, organizational inclusiveness can enhance employee emotional and behavioral investments within organizations. Notably, the results of the experiment paralleled the field-study results. Consistent with past experimental and field data (e.g., Stumpf and London 1981), we found largely similar results between student and working professional samples. Consequently, the experiment and field study formed a complementary and comprehensive way to test our conceptual model.

Practical implications

From a practical perspective, our results highlight the importance of organizational leaders in disseminating a message of organizational inclusiveness. Specifically, the conduct of supervisors may supersede surface-level characteristics (i.e., among all organizational members) with respect to being viewed as inclusive. This is particularly noteworthy because research has found individuals of varying races to have differential perspectives and subsequent outcomes (McKay et al. 2007). We suggest that organizations may be able to increase organizational inclusiveness by shifting a focus to leader conduct and having their leaders serve as key messengers of the organizational stance on inclusion. To increase the consistency and prevalence of organizational inclusiveness, organizations should provide managerial training on the importance of displaying inclusive behaviors toward employees.

Secondly, we encourage organizations to identify applicants’ level of moral identity during the selection process. Many organizations rely on a variety of selection tools to evaluate applicants (Highhouse 2008). However, instead of simply relying on personality dimensions such as the Big 5, we encourage organizations to consider applicants’ moral identity or other proxies of managers being other-focused. One possible way is for employers to examine applicants’ reference letters to gage the extent that they speak to the applicant’s character, level of integrity, and compassion. As we found, supervisors with higher levels of moral identity may be more likely to display inclusiveness regardless of their employing organizations.

Future research

While our focus for this study centered on the trickle-down effect between supervisors and employees, the trickle-down effect may occur elsewhere during the employee life cycle. As suggested by Schneider (1987), the employment cycle occurs in phases: attraction, selection, and attrition. Therefore, judgments and perspectives about organizations may be formed or altered as an employee progresses through various phases of the employee life cycle. For instance, prior research has shown that some applicants, especially racial minorities, are particularly impacted by perceptions of diversity during the attraction phase (McKay and Avery 2006). As such, applicants may be able to detect inclusiveness prior to accepting a job opportunity with an organization. Therefore, future research may benefit by exploring the trickle-down effect within the context of the selection process.

Additionally, we suggest further exploring the implications of the trickle-down effect to other individual and organizational outcomes. Specifically, to what degree does inclusive leadership matter for other subordinate attitudes or behaviors? As discussed, supervisors can impact employee attitudes and behaviors within the workplace. Thus, individual-level attitudes such as job satisfaction, or team level constructs such as cohesion or trust may be influenced by supervisory inclusiveness. Considering these potentially larger and multi-level outcomes, we encourage future research to examine the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness within different employment contexts and as related to various employee outcomes.

Conclusion

As the workforce continues to become more diverse, the importance of workplace inclusion will only grow. While some supervisors may respond differently to organizational cues regarding inclusiveness, organizations that adopt a learning and integration perspective regarding organizational inclusiveness can positively affect how welcoming the organization feels. One key reason this occurs is when supervisors follow the lead set by their organizations.

References

Acquavita, S. P., Pittman, J., Gibbons, M., & Castellanos-Brown, K. (2009). Personal and organizational diversity factors’ impact on social workers’ job satisfaction: results from a national internet-based survey. Administration in Social Work, 33, 151–166.

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17, 351–371.

Aiman-Smith, L., Scullen, S. E., & Barr, S. H. (2002). Conducting studies of decision making in organizational contexts: a tutorial for policy-capturing and other regression-based techniques. Organizational Research Methods, 5, 388–414.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18.

Ambrose, M. L., Schminke, M., & Mayer, D. M. (2013). Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 678.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed II, A., Lim, V. K. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: the interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 123–141.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1423–1440.

Arnold, H. J., & Feldman, D. C. (1981). Social desirability response bias in self-report choice situations. Academy of Management Journal, 24, 377–385.

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., Wilson, D. C., & Volpone, S. (2008). Attenuating the effect of seniority on intent to remain: the role of perceived inclusiveness. Paper presented at the meeting of the Academy of Management, Anaheim, CA.

Bacharach, S., Bamberger, P., & Vashdi, D. (2005). Diversity and homophily at work: supportive relations among white and African-American peers. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 619–644.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice- Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought & action. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: a qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8, 274–289.

Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 157–167.

Bilimoria, D., Joy, S., & Liang, X. (2008). Breaking barriers and creating inclusiveness: lessons of organizational transformation to advance women faculty in academic science and engineering. Human Resource Management, 47, 423–441.

Blasi, A. (1984). Moral identity: Its role in moral functioning. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behavior and moral development (pp. 128–139). New York: Wiley.

Blasi, A. (1993). The development of identity: some implications for moral functioning. In G. G. Naom & T. E. Wren (Eds.), The moral self (pp. 99–122). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Boegershausen, J., Aquino, K., & Reed II, A. (2015). Moral identity. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 162–166.

Bretz Jr., R. D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). The role of human resource systems in job applicant decision processes. Journal of Management, 20, 531–551.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Pay preferences and job search decisions: a person-organization fit perspective. Personnel Psychology, 47, 317–348.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Cho, S., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2008). Understanding of diversity and inclusion in a perceived homogeneous culture: a study of organizational commitment and job performance among Korean employees. Administration in Social Work, 32, 100–126.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900.

Dean, J. W., Brandes, P., & Dharwadkar, R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Academy of Management Review, 23, 341–352.

Douglas, C., Ferris, G. R., Buckley, M. R., & Gundlach, M. J. (2003). Organizational and social influences on leader–member exchange processes: implications for the management of diversity. In G. Graen (Ed.), Dealing with diversity (pp. 59–90). Greenwich: Information Age.

Downey, S. N., Werff, L., Thomas, K. M., & Plaut, V. C. (2015). The role of diversity practices and inclusion in promoting trust and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45, 35–44.

Doyle, R. P., Chase, J. S., Gadde, S., & Vahdat, A. M. (2002). The trickle-down effect: Web caching and server request distribution. Computer Communications, 25(4), 345–356.

Durbin, J., & Watson, G. S. (1971). Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression. III. Biometrika, 58(1), 1–19.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22.

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 51–59.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Elvira, M. M., & Cohen, L. E. (2001). Location matters: a cross-level analysis of the effects of organizational sex composition on turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 591–605.

Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (1996). Making differences matter: A new paradigm for managing diversity. Harvard Business Review, 74(5), 79–90.

Feldman, D. C., & Arnold, H. J. (1978). Position choice: comparing the importance of organizational and job factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 706–710.

Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., & Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(3), 223–241.

Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). West Point: McGraw Hill United States Military Academy.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. (1998). Beyond relational demography: time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 96–107.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/.

Highhouse, S. (2008). Stubborn reliance on intuition and subjectivity in employee selection. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 333–342.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analyses: techniques and applications. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Jehn, K. A., Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. (1999). Why differences make a difference: a field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 741–763.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (2006). Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific Software.

Karren, R. J., & Barringer, M. W. (2002). A review and analysis of the policy-capturing methodology in organizational research: guidelines for research and practice. Organizational Research Methods, 5, 337–361.

Katz, D. (1964). The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behavioral Science, 9, 131–146.

Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 656–669.

Lambert, S. J. (2000). Added benefits: the link between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 801–815.

Letwin, C., Wo, D., Folger, R., Rice, D., Taylor, R., Richard, B., & Taylor, S. (2016). The “right” and the “good” in ethical leadership: implications for supervisors’ performance and promotability evaluations. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(4), 743–755.

Liden, R. C., Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2004). The role of leader-member exchange in the dynamic relationship between employer and employee: Implications for employee socialization, leaders, and organizations. The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives, 226–250

Lirio, P., Lee, M. D., Williams, M. L., Haugen, L. K., & Kossek, E. E. (2008). The inclusion challenge with reduced load professionals: the role of the manager. Human Resource Management, 47, 443–461.

Lykken, D. (1968). Statistical significance in psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 151–159.

McKay, P. F., & Avery, D. R. (2006). What has race got to do with it? Unraveling the role of racioethnicity in job seekers'reactions to site visits. Personnel Psychology, 59(2), 395–429.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Tonidandel, S., Morris, M. A., Hernandez, M., & Hebl, M. R. (2007). Racial differences in employee retention: are diversity climate perceptions the key? Personnel Psychology, 60, 35–62.

Markus, H., & Kunda, Z. (1986). Stability and malleability of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 858.

Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Marinova, S. V. (2012). A trickle-down model of abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 65, 325–357.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mayer, D., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Examining the effects of supervisory and top management ethical leadership. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 538–551.

Miller, F. A. (1998). Strategic culture change: the door to achieving high performance and inclusion. Public Personnel Management, 27, 151–160.

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 941–966.

Nicklin, J. M., Greenbaum, R., McNall, L. A., Folger, R., & Williams, K. J. (2011). The importance of contextual variables when judging fairness: an examination of counterfactual thoughts and fairness theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114, 127–141.

Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 6, 1754–1774.

Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader-member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1412–1426.

O’Reilly, C. A., Caldwell, D. F., & Barnett, W. P. (1989). Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 21–37.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., den Hartog, D. N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 259–278.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method variance in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Pugh, S. D., Dietz, J., Brief, A. P., & Wiley, J. W. (2008). Looking inside and out: the impact of employee and community demographic composition on organizational diversity climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1422–1428.

Reed, I. I., & Aquino, K. F. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard toward out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270.

Rice, D. B. (2018). Millennials and institutional resentment. A new integrated process of marginalization, suppression, and retribution. In M. Gerhardt & J. Peluchette (Eds.), Millennials: Trends, characteristics, and perspectives. New York: Nova Science. Hauppauge.

Riordan, C. M. (2000). Relational demography within groups: past developments, contradictions, and new directions. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 19, 131–173.

Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group and Organization Management, 31, 212–236.

Rousseau, D. M., & Anton, R. J. (1991). Fairness and implied contract obligations in job terminations: the role of contributions, promises, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 287–299.

Ruiz, P., Ruiz, C., & Martínez, R. (2011). Improving the “leader–follower” relationship: Top manager or supervisor? The ethical leadership trickle-down effect on follower job response. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(4), 587–608.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–453.

Shanock, L. R., & Eisenberger, R. (2006). When supervisors feel supported: relationships with subordinates' perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 689–695.

Shao, R., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: a review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18, 513–540.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., & Singh, G. (2010). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37, 1262–1289.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: the roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 434–443.

Stumpf, S. A., & London, M. (1981). Capturing rater policies in evaluating candidates for promotion. Academy of Management Journal, 24, 752–766.

Theodorakopoulos, N., & Budhwar, P. (2015). Guest editors’ introduction: diversity and inclusion in different work settings: emerging patterns, challenges, and research agenda. Human Resource Management, 54, 177–197.

Thomas, D. A., & Ely, R. J. (2001). A new paradigm for managing diversity. Harvard Business Review, 74(5), 79–94.

Umphress, E. E., Smith-Crowe, K., Brief, A. P., Dietz, J., & Watkins, M. B. (2007). When birds of a feather flock together and when they do not: status composition, social dominance orientation, and organizational attractiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 396–409.

Wiersema, M., & Bird, A. (1993). Organizational demography in Japanese firms: group heterogeneity, individual dissimilarity, and top management team turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 996–1025.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.

Wrightsman, L. S. (1974). Assumptions about human nature: a social-psychological analysis. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

Wu, I. H., Lyons, B., & Leong, F. T. (2015). How racial/ethnic bullying affects rejection sensitivity: the role of social dominance orientation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 156–161.

York, K. M. (1989). Defining sexual harassment in workplaces: a policy-capturing approach. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 830–850.

Zhao, X., Sun, T., Cao, Q., Li, C., Duan, X., Fan, L., & Liu, Y. (2013). The impact of quality of work life on job embeddedness and affective commitment and their co-effect on turnover intention of nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22, 780–788.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 582 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rice, D.B., Young, N.C.J. & Sheridan, S. Improving employee emotional and behavioral investments through the trickle-down effect of organizational inclusiveness and the role of moral supervisors. J Bus Psychol 36, 267–282 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09675-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09675-2