Abstract

The current study compares the effectiveness of interventions that attempted to uniquely influence hypothesized determinants of behavior in the Theory of Planned Behavior versus some optimal combination of constructs (three constructs vs. four) to increase condom use among intentions and behavior college students. 317 participants (Mage = 19.31; SDage = 1.31; 53.3% female; 74.1% Caucasian) were randomly assigned to one of seven computer-based interventions. Interventions were designed using the Theory of Planned Behavior as the guiding theoretical framework. 196 (61.8%) completed behavioral follow-up assessments 3-month later. We found that the four construct intervention was marginally better at changing intentions (estimate = − .06, SE = .03, p = .06), but the single construct interventions were more strongly related to risky sexual behavior at follow-up (estimate = .04, SE = .02, p = .05). This study suggests that these constructs may work together synergistically to produce change (ClinicalTrials.gov Number NCT# 02855489).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Often when the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen & Madden, 1986; Ajzen, 1991) is used as the basis for an intervention, only a subset of the constructs seem to produce behavior change (Montanaro & Bryan, 2014; Reid & Aiken, 2011), and it is unclear which theoretical constructs in the theory are the active ingredients of change. A careful examination of the extent to which the theoretical constructs in the Theory of Planned Behavior successfully produce behavior change individually or in combination will help clarify the optimal theoretical framework that should be utilized in behavior change interventions (Sheeran et al., 2017; Conner, 2014). Using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen & Madden, 1986; Ajzen, 1991) as the guiding theoretical framework, this study explores one way to experimentally test how the constructs in the TPB work uniquely and/or in combination with each other to successfully produce health behavior change.

The Theory of Planned Behavior

There are several health behavior theories that purport to explain/predict health behaviors or behavior change (e.g., the Health Belief Model, Janz & Becker, 1984; the Social Cognitive Theory, Bandura, 1985; the Theory of Reasoned Action, Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; and the Theory of Planned Behavior). The TPB has become a popular model, guiding a majority of health behavior research (see McEachan et al., 2011; Noar and Zimmerman, 2005; Armitage and Conner, 2001 for a review of the TPB’s successes). Furthermore, the TPB has successfully predicted (e.g., Albarracín et al., 2001) and changed condom use behavior (e.g., Montanaro & Bryan, 2014). While the TPB certainly has its shortcomings (Sniehotta et al., 2014), meta-analytic work supports both its ability to explain variance in intentions and behavior (McEachan et al., 2011) and behavior change (Sheeran et al., 2016). Thus, the TPB serves as a useful guiding theoretical framework for understanding how one might tease apart the relative contributions of individual constructs in the context of experimental intervention—the major goal of this study.

The Theory of Planned Behavior proposes that attitudes, normative beliefs, and perceived behavioral control (often used interchangeably with self-efficacy) directly influence an individual’s intentions to participate in a behavior. Intentions, and under some circumstances perceived behavioral control (PBC), are then the most proximal causes of action (Ajzen & Madden, 1986). Attitudes toward a specific behavior, subjective norms supporting the behavior, and PBC over the behavior are related to one another, and are direct predictors of intentions.

The TPB assumes that causal associations do not exist between the three proximal determinants of intentions (i.e., attitudes, norms, PBC). Yet literature outside of the TPB framework suggests that such relationships are likely to exist. For example, literature suggests a significant positive relationship between norms and attitudes—specifically, the influence of norms on attitudes in social psychology (Asch, 1956; Milgram, 1964; Stangor, Sechrist, & Jost, 2001). Past work has investigated whether attitudes may also be determinants of norms but, thus far, the role of norms in the attitude-behavior relationship has generally failed to support this hypothesis (Ajzen, 1991; Trafimow & Finlay, 1996). The relationship PBC has with attitudes and/or norms is rarely explicitly discussed, and when explicitly addressed tends to provide weak correlations that support the idea that the relationship of PBC to attitudes and norms is potentially indirect, if it exists at all (Rivis & Sheeran, 2003; Bandura, 1989).

Intentions are the most proximal and important predictor of behavior, according to the TPB (Hagger et al., 2017). The TPB assumes that intentions capture the motivational processes necessary to influence behavior, and this hypothesis has largely been borne out—medium-to-large changes in intentions generally produce small-to-medium changes in behavior (Webb & Sheeran, 2008). The TPB states that, to produce changes in intentions, one must first produce changes in attitudes, norms, and PBC; however, researchers have found that directly targeting intentions can also be a successful approach to producing behavior change. For example, Gollwitzer’s (1993, 1999) implementation intentions technique directly targets intentions, and has a significant effect on behavior. Implementation intentions require an individual to specify a behavior to perform and the context in which they will perform it. Forming implementation intentions increases the likelihood of performing that behavior and achieving a particular goal. Implementation intentions have worked to change behavior in a variety of domains, in particular increasing condom use preparatory behavior (Montanaro & Bryan, 2014).

The TPB has been criticized for its exclusive focus on rational reasoning and its limited predictive validity (Sniehotta et al., 2014). In fact, Sniehotta et al. (2014) called for a retirement of the TPB. However, others have begun to explore the nomological validity of the TPB and have found support for the nomological validity of the TPB (Hagger et al., 2016). Still others believe the TPB offers a solid foundation for more expansive theoretical work. These researchers think that the TPB has made important contributions and we must capitalize on this in order to “usefully extend” the TPB in health behavior change research Conner (2014). Conner (2014) suggests the next research question be an examination of “the extent to which the different components specified by the TPB can be independently manipulated (pg. 2)”. Are all of the constructs in the TPB necessary to create behavior change (Sheeran et al., 2017)? It might be the case that multiple constructs (e.g., attitudes, intentions) need to be targeted in order to create behavior change (Williams et al., 1998) and none on their own are sufficient by themselves to create that change. Additionally, many studies utilizing the TPB as a theoretical framework simply do not include intervening measures of the meditational constructs included in the theory (Sheeran et al., 2016). Often times this leads to interventions lacking the necessary information to examine the mechanisms by which a TPB intervention leads to behavior change; ultimately making it impossible to determine if it is really changes in these constructs that produce behavior change (Sheeran et al., 2016). These are empirical questions that should be answered to facilitate optimal intervention development and to inform the progress of theoretical innovations in the behavior change domain.

Dismantling studies

One way to investigate the unique influence of each individual construct versus the synergistic effects of the combination of constructs on behavior is through the use of a dismantling study. Dismantling studies attempt to influence single components of a theory versus increasingly complex combinations of components in order to inform the question of whether one component may act as the active ingredient of change or whether some threshold of a combination of components is necessary (Shadish et al., 2002). This allows for theoretical advancement because it determines which constructs in which combinations are necessary and sufficient in behavior change processes (Holtforth et al., 2004). In a recent meta-analysis Sheeran et al. (2016) suggest that is important to identify the key psychological construct(s) that may be the central determinant of behavior change for a specific behavior.

Current study

This study assesses how the manipulation of each TPB construct, either alone or in combination, influences the targeted construct/s and, importantly, those constructs not explicitly targeted in the intervention. This question is explored in the health domain of condom use intentions and behavior among college students. The American College Health Association (2014) reported that only 27% of college-aged students use condoms every time they have sex, and emerging adults remain at relatively higher risk for HIV/STI (CDC, 2012). This population needs theoretically driven interventions to increase condom use.

Distinct interventions were designed for this study in order to target the core constructs of the TPB, following model development recommendations by Aiken (2010). We sought to determine which individual TPB constructs and which combinations of these constructs (single construct interventions vs. partial vs. full TPB intervention) are most successful at changing risky sexual behavior among college students. Interventions were categorized into single construct interventions versus partial versus a full TPB intervention using Sheeran et al.’s (2016) taxonomy. In their meta-analysis, the authors investigated whether changing more than one cognition resulted in larger behavioral changes than focusing on all constructs included in a health behavior theory (Sheeran et al., 2016). Although Sheeran et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis stated that one construct interventions were more successful at changing behavior than “full theory” interventions, this is in direct opposition to current suggestions for intervention development recommending that the full TPB should be targeted in an intervention to produce behavior change (Peters et al., 2013; Williams et al., 1998). Given current intervention development recommendations, we hypothesized that interventions targeting all TPB constructs would have greater behavior change than those targeting a single construct or a subset of constructs. A secondary question was whether it is feasible to uniquely impact only one construct, given the theoretical, empirical and conceptual overlap between them.

Method

Participants

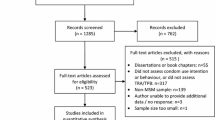

A total of 317 participants were recruited from introductory psychology courses at the University of Colorado Boulder during the Fall of 2013 and Spring of 2014 (see Fig. 1; ClinicalTrials.gov Number NCT# 02855489). The predictors of condom use are dramatically different in casual versus serious relationships (c.f., Reid & Aiken, 2011) and condom use is extremely difficult to change among those in established long-term relationships. Thus, participants were excluded if they indicated that they were “living with” someone or “married”.

Overall, participants were about half female (53.3%) and predominantly Caucasian (74.1%; 2.5% African American; 5.7% Hispanic; 1.6% Native American; 10.1% Asian or Pacific Islander; 6.0% other). On average, participants were 19.32 years of age (SD = 1.31; range 18–26). 95.5% of participants reported being heterosexual and 67.1% were not currently in a romantic relationship. A majority of participants reported experiencing vaginal intercourse in their lifetime (83.5%). Of those who had experienced intercourse, only 27.1% reported using condoms 100% of the time they have had sex in the last 3 months. On average, participants had M = 5.11 (SD = 5.96) lifetime sexual partners (see Table 1).

Design

Seven computer-based intervention conditions were developed targeting the constructs in the TPB (i.e., attitudes, norms, PBC, and intentions). Four single construct conditions (i.e., attitudes only, norms only, PBC only, intentions only) were designed in order to identify whether it was possible to uniquely manipulate one construct at a time or whether effects of our manipulations were more diffuse, and to determine whether any of the constructs might be sufficient alone to engender behavior change. Two multiple construct conditions were also designed. A three construct condition, which included attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control represented the core components of the TPB that are thought to work through intentions to result in behavior change. A four construct condition (i.e., attitudes, norms, PBC, and intentions) was designed to represent the “full TPB model” intervention which we expected would be more successful than either the three-construct intervention or any of the single construct interventions. For the two multi-construct interventions, each construct was presented in a discrete module (e.g. all attitude intervention components were presented together, followed by all norms intervention components, and so on). Finally, a no-treatment control condition, which solely consisted of pretest and posttest assessments, was included. This allowed us to obtain important information about how the theoretical constructs in the TPB change over time (or do not) in the absence of an experimental manipulation. For each condition participants completed a pretest assessment, an intervention (except for the control group), immediate posttest assessment, and a 3 months follow-up assessment.

Procedure

Participants received course credit for their participation in the first component of the study. If students provided consent a computer algorithm randomly assigned them to one of the seven intervention conditions. Researchers and participants were both blinded to study condition. Once assigned to an intervention condition they completed a baseline series of questionnaires, completed the intervention, and completed a set of posttest assessments. Participants completed all aspects of the study on their personal computers in locations and times most convenient for them. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Attitudes towards behavior

All constructs contained in the TPB were measured using techniques following Ajzen and Madden (1986). Participants were asked seven questions regarding their attitudes toward condoms. Each item was assessed using a seven-point scale. A sample item is: “For me, using a condom would be unhealthy (1) versus healthy (7).” The remaining six anchors included (1) harmful versus beneficial, (2) unpleasant versus pleasant, (3) bad versus good, (4) worthless versus valuable, (5) unenjoyable versus enjoyable, and (6) punishing versus rewarding. Items were averaged to form a scale score (α = .91). Higher scores indicated more positive attitudes.

Subjective norms

These items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). Participants were asked what their sexual partners, friends, family, and most people think about condom use. This scale consisted of items such as “My friends think that I should use condoms” that were averaged (α = .86). Higher scores indicated higher condom use norms.

Perceived behavioral control

Ajzen and Madden (1986) note that, conceptually, the construct that is most “similar to the present use of perceived behavioral control is Bandura’s (1977, 1982) concept of self-efficacy beliefs.” We thus measured the construct of PBC using Brien et al.’s (1994) Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES). This measure uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The CUSES addresses four domains of condom use: the mechanics of putting on a condom, partner disapproval, assertiveness, and the influence of intoxicants on a person’s ability to use condoms. A sample item from the CUSES is: “I feel confident in my ability to use a condom correctly.” Items were averaged to form a scale score (α = .89). Higher scores indicated greater condom use self-efficacy.

Intentions

Four questions relating to the TPB concern participants’ intentions to use a condom within the next 3 months. A sample item is: “How likely is it that you will use a condom the next time you have intercourse?” These items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (very likely) and averaged to form a scale score (α = .84). Higher scores indicated greater condom use intentions.

Behavioral outcome

Behavior was assessed by calculating risky sexual behavior, which was a composite variable calculated using “how often a participant had sex in the past 3 months (1 = once a month to 5 = almost everyday)” X “how much of the time they used a condom when having sex during those 3 months (0 = 0% of the time to 10 = 100% of the time)” (reverse coded). Higher scores indicated riskier sexual behavior.

Conditions

The appendix provides descriptions and examples of intervention content. The techniques used have all been previously used into influence the constructs of interests (Michie et al., 2013). Briefly, the attitudes condition targeted cognitive and affective attitudes by pairing attitudinal messages with pictures, and included an evaluative conditioning task. The norms condition utilized a group-affirmation exercise, personalized feedback, and group norms in an attempt to influence perceptions of normative support for condom use norms. The PBC condition included a condom application video, lubrication instructions, condom negotiation videos, and a detailed description regarding purchasing condoms to increase participant confidence that they could accomplish these behaviors. Finally, the intentions condition asked participants to form implementation intentions in order to increase their condom use intentions. Each intervention component was previously developed and validated in the broader social psychology literature (e.g., the norms intervention included a group affirmation exercise; Sherman et al., 2007). These developmental and validation studies are in the appendix, which describes intervention content. Additionally, participants in the active conditions, but not in the control condition, received a list of area resources for STI testing and other sexual health services. The interventions themselves, quality control and utilization assessments from the web interface, are available on request.

Average completion times for each condition ranged from 30 to 68 min: attitudes only condition (Mtime = 40 min), norms only condition (Mtime = 51 min), PBC condition (Mtime = 52 min), intentions only condition (Mtime = 30 min), attitudes/norms/PBC condition (Mtime = 64 min), attitudes/norms/PBC/intentions condition (Mtime = 68 min), control condition (Mtime = 31 min).

Immediate posttest outcomes

Assessments for each theoretical construct were completed immediately following the end of each condition by participants (e.g., Schmiege et al., 2009; Jemmott et al., 1998). This provided an assessment of the extent to which levels of those constructs were impacted by the condition and allowed for an assessment of the degree to which changes in those constructs were associated with changes in intentions and/or behavior.

Follow-up behavioral assessments

Three months after the intervention and posttest assessment, participants received an email from the experimenter. The follow-up assessment, which participants completed on their personal computers via Qualtrics, focused on risky sexual behavior during the 3 months follow-up period. Risky sexual behavior was a composite variable calculated using “how many times a participant had sex in the past 3 months” X “how many times they used a condom when having sex during those 3 months” (reverse coded). Higher scores indicated riskier sexual behavior. Participants received $15 for completion of the follow-up assessment via PayPal.

Data analysis plan

First, bivariate correlations were examined among the TPB variables and risky sexual behavior at baseline. Second, to examine whether the intervention utilizing the full TPB was more successful than those including either a subset of TPB constructs or only individual TPB constructs at changing the TPB mediators and risky sexual behavior, we compared the single construct interventions versus the three construct versus the full four construct intervention. Finally, the assessments of the TPB constructs at posttest were included in a mediational structural equation model (Bryan et al., 2007) to explore the active ingredients of condition effects on risky sexual behavior at follow-up. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was utilized (c.f., Schafer & Graham, 2002) to account for missing data.

Results

Baseline relationships between TPB constructs & behavioral outcomes

Correlations between pretest TPB constructs and past risky sexual behavior are displayed in Table 2. These indices suggest the relative strength of the individual predictors. All of the TPB constructs, except for PBC, were significantly related to risky sexual behavior at baseline. We noted a possible ceiling effect in levels of condom use PBC at baseline (M = 4.27, SD = .57, on a 1–5 scale). Thus it is difficult to examine either associations of behavior with PBC or changes in PBC as a result of the interventions given so little variability among participants. We chose to focus on risky sexual behavior, as opposed to condom use per se, as the outcome in order to also include participants who had not had sex during the 3 months follow-up period. Such participants would have missing data for condom use (as they had not had intercourse so condom use is not relevant) whereas they could be assigned a risky sexual behavior score = 0 indicating that they had no risky sex.

Condition differences

All conditions

One-way ANCOVAs were conducted for each of the TPB constructs to examine the effectiveness of intervention condition (i.e., attitude only, norms only, PBC only, intentions only, attitude/norms/PBC, attitude/norms/PBC/intentions, and no-intervention control) whilst controlling for pre-test scores. The pre- and posttest means for all constructs across all conditions appear in Table 3. There was a significant difference in attitudes towards condom use at posttest (F (6, 279) = 2.77, p = .01) and condom use intentions (F (6, 286) = 4.30, p < .001), but not for norms supporting condom use (F (6, 243) = 1.75, p = .11) or PBC (F (6, 241) = 1.59, p = .15). Post hoc tests examining attitudes towards condom use at posttest showed there was a significant difference between the attitudes only condition and the four construct condition (i.e., attitude/norms/PBC/intentions; p < .001). Comparing estimated marginal means show that attitudes towards condom use were highest in the four construct condition (M = 5.81) and lowest in the attitudes only condition (M = 5.28). Post hoc tests examining condom use intentions at posttest showed there were significant differences between the attitudes only condition and the four construct condition (p < .001), the intentions only condition and the four construct condition (p < .01), and the four construct condition and the control condition (p < .01). Comparing estimated marginal means showed that the highest condom use intentions were in the four construct condition (M = 5.08) compared to the intentions only condition (M = 4.36), control condition (M = 4.31), and the attitudes only condition (M = 4.24).

Theory versus control

We also examined whether theory-based conditions (combining all 6 theory-based conditions) were more effective than the control condition at changing the constructs in the TPB and risky sexual behavior. We found that there was a marginal effect of theory-based conditions versus the control condition on intentions after controlling for pretest intention scores, F (1, 291) = 2.97, p = .09. Comparing estimated marginal means showed that the highest condom use intentions were in the theory-based conditions (M = 4.59) compared to the control condition (M = 4.31). No other psychological constructs showed differences between the theory-based conditions and the control condition from pretest to posttest (p’s > .10).

Construct combination differences

One-way ANCOVAs were conducted to determine differences between the number of constructs targeted (i.e., single vs. three vs. four) controlling for pretest scores. Pretest and posttest means by contrast condition are presented in Table 4. There was a significant effect of the number of constructs targeted (i.e., single vs. three vs. four) in an intervention on attitudes towards condom use after controlling for pretest attitude scores, F (2,242) = 3.12, p < .05. Pairwise Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons revealed that the greatest difference existed between the single construct interventions and the four construct intervention (p < .05). Comparing estimated marginal means showed that the highest attitudes towards condom use were in the four construct condition (M = 5.78) compared to the single construct condition (M = 5.49). There was also a significant effect of the number of constructs targeted in an intervention on intentions, F (2,251) = 6.80, p < .001. Pairwise Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons revealed that significant differences existed between the single construct conditions and the four construct intervention (p < .001) and between the three construct and four construct interventions (p < .05). Comparing estimated marginal means showed that the highest condom use intentions were in the four construct condition (M = 5.05) followed by the single construct condition (M = 4.46), and lowest in the three construct condition (M = 4.45).

Three month follow-up

196 of the 317 (61.8%) participants completed follow-up assessments (see Table 1). A series of ANOVAs on attitudes, norms, PBC, intentions, and risky sexual behavior at pretest using condition and retention (retained vs. not retained) as the independent variables were conducted to test for differential attrition (Bryan et al., 1996). There were no condition x retention interactions for any of the theoretical constructs or behavior examined (ps > .32), suggesting no differential attrition by condition occurred.

Of the 196 participants who completed the follow-up, 59.7% (n = 117) had had sex in the past 3 months. There were no overall condition differences for risky sexual behavior at the 3 months follow-up after controlling for risky sexual behavior at baseline (p > .50; see Table 3). However, when examining the specific contrast of whether theory-based conditions were better than control we found that there was a significant effect for risky sexual behavior at the 3 months follow-up after controlling for risky sexual behavior at baseline, F (1, 127) = 6.12, p < .05. Comparing estimated marginal means showed that risky sex was highest in the control condition (M = 12.64) and lowest in the theory based conditions (M = 9.15).

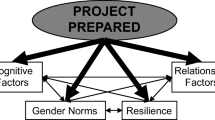

Which constructs are active ingredients of change?

We found that, in general, the theory-based conditions were better at changing behavior than the control condition, thus we chose to focus only on differences among the theory-based conditions when investigating the active ingredients of change. We estimated a mediational model via path analysis (c.f., Bryan et al., 2007) using Mplus, wherein there were two exogenous variables representing two planned contrasts: single construct interventions versus four construct intervention and three construct intervention versus four construct intervention (see Fig. 2). With the exception of attitudes towards condom use there were no significant differences at baseline between conditions, thus the mediators were the posttest values of each mediational construct (Bryan et al., 1996). A difference score (posttest attitudes–pretest attitudes) was used to test the attitudes mediator within the context of the model. To account for the missing data at follow-up, full information maximum likelihood estimation was utilized (c.f., Schafer & Graham, 2002) and thus robust estimation of standard errors was conducted for tests of fit and significance of the paths. The fit of this model was adequate, χ2(5, N = 310) = 14.48, p = .013, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI .03–.13), SRMR = .04. Paths from the single construct versus four construct intervention contrast were related to a change in intentions, such that the four construct intervention resulted in a greater change in intentions than the single construct interventions. Changes in attitudes and norms were related to changes in intentions, which was then associated with risky sexual behavior at follow-up (see Fig. 2). No other constructs were related to intentions or behavior.

Examining the active ingredients of change. Note PBC perceived behavioral control. Coefficients are standardized path coefficients. The contrasts were coded as such: single versus four: four = − 1, three = 0, single = 1. Three versus four: four = − 1, three = 1, single = 0. *p < .05, two-tailed. **p < .01, two-tailed; ***p < .001, two-tailed. Tests of skewness and kurtosis of risky sexual behavior were conducted and indicated that the data were normally distributed. The model was estimated using intervention duration and gender as a covariate and the substantive findings were unchanged. Additionally, the model was estimated without participants who had never had sex and the substantive findings were unchanged. For simplicity, we present the model without the covariate included and the full sample

Next, we explored the total indirect effects of experimental condition on intentions and risky sexual behavior at follow-up using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Total indirect effects are the sum of all the indirect effects of an exogenous variable (e.g., single construct interventions vs. four construct intervention contrast) on endogenous variables (e.g., risky sexual behavior). Marginal direct effects were found from the single construct versus four construct intervention contrast to intentions (estimate = − .06, SE = .03, p = .06). Additionally, indirect effects were found from the single construct versus four construct intervention contrast to risky sexual behavior at follow-up (estimate = .04, SE = .02, p = .05). These results suggest the four construct intervention was better at producing change in intentions, but the single construct interventions were better at changing risky sexual behavior at follow-up. No other indirect effects were related to intentions or behavior. The model was estimated using completion times and without participants who had never had sex, and the substantive findings were unchanged.

Discussion

When examining the intervention content most successful at changing the TPB mediators and risky sexual behavior, we found that for attitudes and intentions the full TPB four construct intervention (attitudes + norms + PBC + intentions) produced the biggest changes. However, examination of the indirect effects from the full mediational model revealed it was the single construct interventions that were related to risky sexual behavior at follow-up. Findings partially support the nomological validity of the TPB given the (1) significant omnibus test of the full meditational model, and (2) the ‘core’ relationship of intentions-behavior in the TPB was supported (Hagger et al., 2017). Overall, these results suggest that an examination of the relationships between the cognitive mechanisms hypothesized to underlie behavior in the TPB and their relative strength in predicting behavior change is important to facilitate our understanding of the mechanisms by which theory-based interventions have their effects. Practically speaking, it was remarkably difficult to influence only one construct uniquely, and in fact interventions specifically designed to target only one construct influenced other constructs as well (i.e., a PBC only intervention resulted in changes in attitudes).

Implications

Results of this study speak to a larger and potentially more important concern in health behavior theory research—current recommendations for the development of theory-based interventions to change behavior suggest that each construct of a particular theory ought to be targeted in an intervention (Peters et al., 2013; Williams et al., 1998). However, interventions targeting a single construct, implementation intentions interventions, for example, are often used in hopes of creating behavior change (Lo et al., 2014). The results of the current study suggest all four constructs in the TPB potentially need to be targeted in order to create change, but why this is the case remains largely unknown. For example, our data suggest that an intervention focusing on attitude change alone would be uniquely unsuccessful at reducing risky sexual behavior. The TPB is often criticized for not providing guidance on which intervention techniques one should use to change the constructs discussed in the theory (McEachan et al., 2011). It is possible that the lack of robust changes in TPB constructs we saw was due to weak or ineffective operationalization of the intervention content. However, we tried to optimally target the individual constructs using techniques discussed in both the condom use intervention literature and in literature relevant to each individual construct. For example, the attitudes component of the interventions was primarily guided by Conner et al. (2011) where they presented participants with cognitive and affective attitudes to change exercise behavior. Yet our manipulation of attitudes failed to result in changes to the attitudes construct. This would be a compelling direction for future research at the interface of health behavior theory and the emerging literature on behavior change techniques (Michie et al., 2013).

The constructs of the TPB are often treated as isolated entities that are minimally related to each other, yet a rich history of research in social psychology suggests otherwise (Milgram, 1964; Stangor et al., 2001; Bandura, 1989; Rivis & Sheeran, 2003) as do the results of this study. For example, Stangor et al. (2001) found that providing participants with in-group members’ supposed opinions (a manipulation of norms) can actually make attitudes stronger and more resistant to change. Similarly, Bandura (1989) theorizes that negative attitudes are really controlled by self-efficacy, such that those with high self-efficacy in anxiety provoking situations will have fewer negative attitudes than those with lower self-efficacy. Hagger et al. (2017) suggested a complete test of nomological validity of the TPB must include a priori hypotheses about when and how the theoretical constructs are interconnected, and perhaps even causally related. Thus some reconceptualization regarding the interconnectedness between theoretical constructs in the TPB would seem another fruitful avenue to pursue.

A possible limitation to conventional behavior change interventions is the ability to accurately catalog exposure to a given intervention component. As technology (e.g., smart phones) is increasingly being used as an effective platform for the delivery of interventions, it also provides opportunities to improve upon traditional intervention delivery techniques (Montanaro et al., 2015). Advances in technology allow for the kind of micro level data needed to dismantle the active ingredients of the TPB for an individual, not just a group of participants. The optimal combination of constructs within an intervention may ultimately depend on characteristics of the individual as well as their unique interaction with the intervention material.

There is still a tremendous amount to be learned about the optimal theory or the optimal combination of constructs from across theories that will most strongly influence behavior change. This study addressed one important question regarding the TPB and risky sexual behavior, and suggests that many of the constructs manipulated here are conceptually and empirically interconnected and that attempting to influence one may have residual—or even stronger—effects on other constructs. But knowing that having all four “present” in the intervention is important does not make use of the interconnectedness among the constructs. There is a great deal of conceptual overlap and potentially causal associations between constructs and this linkage may not be fully utilized by intervention designers. Further research is necessary to develop the optimal ordering of presentation of intervention materials regarding potential causal associations among the constructs of the model under investigation.

Limitations

Despite our attempts to limit the participation of those in relationships by excluding those who were married or living with a partner, individuals in a serious committed relationship nevertheless comprised nearly 33% of the study sample (Bauman et al., 2007). This may have made the intervention inappropriate for a large portion of the study sample. Participants in this study were overwhelmingly Caucasian (74.1%), limiting the generalizability of our findings While the fact that our participants were also all college students, a further limitation to generalizability, this is a population in need of effective sexual risk reduction programs (ACHA, 2014). A further limitation of this study includes the low retention rate: 61.8%. In general, researchers consider an 80% retention rate adequate to detect reliable effects (Desmond et al., 1995), but in reality, retention rates vary widely across studies. Statistical power is lowered when participants do not return to participate, potentially hindering our ability to detect condition effects on behavior (Shadish et al., 2002) or biasing our estimates of intervention effects. However, no pretest differences existed among those who were retained versus not-retained, which helps to alleviate some concerns about bias. In Spencer et al. (2005), the authors argue that mediators must also be experimentally manipulated, because even if the path from intervention to mediator is experimental, the path from mediator to outcome is not. In our study, by examining the direct effects of the conditions on all the constructs and behavior, we believe we have provided a test of the causal relationships. Ultimately, though, because our mediators are measured constructs (e.g., attitudes scale) causal inferences are limited in regards to the relationships of the measured mediators to behavior. Finally, perhaps the largest limitation was the possible ceiling effect in levels of condom use PBC making it practically impossible to improve PBC within this sample. It is difficult to examine either the efficacy of our intervention to change PBC or the relative contributions of PBC change to behavior change with so little room to change and so little variability among participants. Perhaps a study using the same methodology, but focusing on a behavior that people do not know how to perform and do not have confidence in their ability to do (e.g., CrossFit among sedentary individuals) would allow for the examination of the relative contributions of PBC in the behavior change process.

Conclusions

It is important that theories guiding intervention development be accurate regarding the production of behavior change. Thus, a nuanced understanding of the relationships between attitudes, norms, PBC, and intentions in affecting behavioral change is required. Researchers have the tools to explain these relationships via the development, testing, and implementation of novel interventions in rigorous experimental designs. A better understanding of the interconnectedness, causal ordering, necessity, and sufficiency of each of these constructs has the potential to alter the way health behavior change is accomplished.

References

Aiken, L. S. (2010). Advancing health behavior theory: The interplay among theories of health behavior, empirical modeling of health behavior, and behavioral interventions. In H. Friedman (Ed.), Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 1–39). New York City: Oxford University Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I., & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 453–474.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., Fishbein, M., & Muellerleile, P. A. (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 142–161.

American College Health Association (ACHA). (2014). American college health association-national college health assessment II: Undergraduate students reference group data report spring 2014. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70, 1–70.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.

Bandura, A. (1985). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. The American Psychologist, 44, 1175–1184.

Bauman, L. J., Karasz, A., & Hamilton, A. (2007). Understanding failure of condom use intention among adolescents completing an intensive preventive intervention. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 248–274.

Brien, T. M., Thombs, D. L., Mahoney, C. A., & Wallanu, L. (1994). Dimensions of self-efficacy among three distinct groups of condom users. Journal of American College Health, 42, 167–174.

Bryan, A. D., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1996). Increasing condom use: Evaluations of a theory-based intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases in young women. Health Psychology, 15, 371–382.

Bryan, A., Schmiege, S. J., & Broaddus, M. R. (2007). Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: Estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 365–383.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). STDs in adolescents and young adults. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/adol.htm

Conner, M. (2014). Extending not retiring the theory of planned behaviour: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychology Review, 9, 141–145.

Conner, M., Rhodes, R. E., Morris, B., McEachan, R., & Lawton, R. (2011). Changing exercise through targeting affective or cognitive attitudes. Psychology and Health, 26(2), 133–149.

Desmond, D. P., Maddux, J. F., Johnson, T. H., & Confer, B. A. (1995). Obtaining follow-up interviews for treatment evaluation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 12, 95–102.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 141–185). London: Wiley.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

Hagger, M. S., Chan, D. K., Protogerou, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2016). Using meta-analytic path analysis to test theoretical predictions in health behavior: An illustration based on meta-analyses of the theory of planned behavior. Preventive Medicine, 89, 154–161.

Hagger, M. S., Gucciardi, D. F., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2017). On nomological validity and auxiliary assumptions: The importance of simultaneously testing effects in social cognitive theories applied to health behavior and some guidelines. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14.

Hofmann, W., De Houwer, J., Perugini, M., Baeyens, F., & Crombez, G. (2010). Evaluative conditioning in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 390–421.

Holtforth, M. G., Castonguay, L. G., Borkovec, T. D., & Building, M. (2004). Expanding our strategies to study the process of change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 396–404.

Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11, 1–47.

Jemmott, J. B., III, Jemmott, L. S., & Fong, G. T. (1998). Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 279, 1529–1536.

Lo, S. H., Good, A., Sheeran, P., Baio, G., Rainbow, S., Vart, G., et al. (2014). Preformulated implementation intentions to promote colorectal cancer screening: A cluster-randomized trial. Health Psychology, 33, 998–1002.

Magnan, R. E., Callahan, T. J., Ladd, B. O., Claus, E. D., Hutchison, K. E., & Bryan, A. D. (2013). Evaluating an integrative theoretical framework for HIV sexual risk among juvenile justice involved adolescents. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 4, 217.

McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., & Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5, 97–144.

Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., et al. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46, 81–95.

Milgram, S. (1964). Group pressure and action against a person. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69, 137–143.

Montanaro, E. A., & Bryan, A. D. (2014). Comparing theory-based condom interventions: Health belief model versus theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology, 33, 1251–1260.

Montanaro, E., Fiellin, L. E., Fakhouri, T., Kyriakides, T., & Duncan, L. R. (2015). Using videogame applications to assess gains in substance use knowledge in adolescents: New opportunities for evaluating intervention exposure and content mastery. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e245.

Noar, S. M., & Zimmerman, R. S. (2005). Health behavior theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: Are we moving in the right direction? Health Education Research, 20, 275–290.

Peters, E., Klein, W., Kaufman, A., Meilleur, L., & Dixon, A. (2013). More is not always better: Intuitions about effective public policy can lead to unintended consequences. Social Issues and Policy Review, 7, 114–148.

Reid, A. E., & Aiken, L. S. (2011). Integration of five health behavior models: Common strengths and unique contributions to understanding condom use. Psychology & Health, 26, 1499–1520.

Rivis, A., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social, 22, 218–233.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177.

Schmiege, S. J., Broaddus, M. R., Levin, M., & Bryan, A. D. (2009). Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 38–50.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Leaning.

Sheeran, P., Klein, W. M., & Rothman, A. J. (2017). Health behavior change: Moving from observation to intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 573–600.

Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A. D., Klein, W. M. P., et al. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35, 1178–1188.

Sherman, D. K., Kinias, Z., Major, B., Kim, H. S., & Prenovost, M. (2007). The group as a resource: Reducing biased attributions for group success and failure via group affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1100–1112.

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8, 1–7.

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective in examining psychological process than mediational analyses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 845–851.

Stangor, C., Sechrist, G. B., & Jost, J. T. (2001). Changing racial beliefs by providing consensus information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 486–496.

Trafimow, D., & Finlay, K. A. (1996). The importance of subjective norms for a minority of people: Between subjects and within-subjects analyses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 820–828.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2008). Mechanisms of implementation intention effects: The role of goal intentions, self-efficacy, and accessibility of plan components. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 373–395.

Williams, G. C., Freedman, Z. R., & Deci, E. L. (1998). Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care, 21, 1644–1651.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Erika Montanaro was supported by T32MH020031 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Erika A. Montanaro, Trace S. Kershaw, Angela D. Bryan declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and Informed consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montanaro, E.A., Kershaw, T.S. & Bryan, A.D. Dismantling the theory of planned behavior: evaluating the relative effectiveness of attempts to uniquely change attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control. J Behav Med 41, 757–770 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9923-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9923-x