Abstract

The present investigation sought to examine the efficacy of the instructional curriculum described in the Direct Training Module of the PEAK Relational Training System on the language repertoires, as measured by the PEAK direct assessment, of children diagnosed with autism or related developmental disabilities. Twenty-seven children diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorders were evaluated using the PEAK direct training assessment protocol prior to assignment to control and experimental groups. Participants in the experimental group received additional language instruction derived from the curriculum programs of the Direct Training Module, while participants in the control group received treatment as usual. Both groups were then re-assessed using the PEAK direct assessment after 1 month. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated that participants in the experimental group made significantly more gains in language skills than those who were assigned to the control group, F(1, 22) = 9.684, p = .005. Implications for evidence-based practice and future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Within the public education system, as much as 13.2 % of all students carry a developmental disability diagnosis with as many as .7 % being diagnosed with autism (US Department of Education 2011). For these students, early intervention and special education services are not only a necessity but also a legal right (IDEA 2004). These services often focus on specialized instruction of academic material, social skills coaching, behavior management strategies, and trainings designed to remediate language deficits. Among the various approaches utilized in providing these services, programs and methodologies derived from behavior analysis have shown a strong cumulative record of success with autism and have received endorsement as empirically established by the US Surgeon General (1998) and the National Autism Center (2009).

In addressing language deficits, behavior analytic approaches commonly focus on functional communication training to reduce problematic behaviors (see Tiger et al. 2008 for a review of literature on FCT) and intensive language instruction derived from psycholinguistic (Lovaas 2003) and verbal operant conceptualizations of language learning (LeBlanc et al. 2006). Although the former approach to language instruction is primarily focused on receptive and expressive language, the latter approach is derived from B.F. Skinner’s (1957) conceptual analysis of Verbal Behavior. According to Skinner, language learning was best described not by topography, but by the relationship between stimulating events (A), the response of the speaker (B), and subsequent actions on the part of the listener (C). For example, Skinner suggested that requesting or “manding” was best described in the context of a learning history in which a particular response was more likely to occur in the future if it was emitted in the presence of appropriate motivation and resulted in the delivery of the desired item. Skinner defined six elementary operants in this manner: that of the mand, tact, echoic, intraverbal, textual, and transcription responses. Skinner also described various types of audience controls and relational responses, called autoclitics, which modified the form of responses and modulated the meaning of language. Despite the broad scope of Skinner’s conceptualization of language learning, empirical research upon Skinner’s analysis has been generally limited to mands, tacts, intraverbals, and echoic responses (Dixon et al. 2007; Dymond et al. 2006). However, these four verbal operants have translated well into intervention strategies as they are fundamental to the language-learning process and are often observed to be absent in individuals with language deficits (cf. Sundberg and Michael 2001). Additionally, the ABC sequence of behavior acquisition can be applied easily to instruction procedure. For example, when teaching an individual to label items or “tact,” the instructor can present a stimulus along with the cue “what is this” (A), wait for a response on the part of the learner (B), and then provide an appropriate consequence such as praise or a corrective prompt (C).

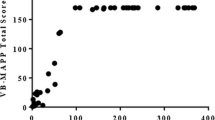

Applied verbal behavior (AVB) is an approach to language learning that has traditionally focused on Skinner’s verbal operants. In general, AVB assessment protocols have been used to demark the verbal repertoires of individuals across the independent verbal operant categories and inform instructors as to the types of skills that need to be taught. The assessment of basic language-learning skills (ABLLS-R; Partington 2008) and the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP; Sundberg 2008) are two popular examples of such AVB assessments. In both examples, criterion-referenced assessment items are provided across a number of language skill categories including the elementary verbal operants in addition to other relevant academic, functional, and social skill repertoires. In the case of the ABLLS-R, items are organized by complexity across 25 skill categories and are designed to assess repertoires up to 4 and 5 years of age. The VB-MAPP on the other hand is arranged into developmental milestones and includes skills up to 4 years of age. Both assessment protocols offer guidance on curriculum and development of Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). Despite the popularity of these two protocols, published literature detailing the reliability and validity of these assessments are unavailable. Furthermore, there have been no published demonstrations of the superiority of these protocols to treatment as usual in education settings where AVB treatments are not in place.

The PEAK Relational Training System (Dixon 2014a, b. Dixon, in press-a; Dixon, in press-b), a recent addition to the AVB literature, is a series of assessments and curriculum guides that incorporates the traditional Skinnerian verbal operants (Skinner 1957) with contemporary behavior analytic concepts such as relational frame theory (Hayes et al. 2001). The PEAK system consists of four modules, each including a separate 184-item criterion-referenced assessment and corresponding curriculum programs. The PEAK Direct Training Module (PEAK-DT; Dixon 2014a) is designed to assess and teach language skills according to the traditional ABC design in which each response is reinforced in the presence of an appropriate discriminative stimulus. The second module, the PEAK Generalization Module (PEAK-G; Dixon 2014b), focuses on the learner’s ability to extend learned responses to similar but nonidentical stimuli. The PEAK Equivalence Module (PEAK-E; Dixon, in press-a) and the PEAK Transformation Module (PEAK-T; Dixon, in press-b) are concerned with learning through relations between stimuli.

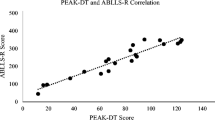

Although a relative new resource for the professional community, the assessment of the PEAK-DT has established a convergent validity through correlation with standardized assessments of language and cognition, such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary (Dixon et al. 2014a, b, c) and various assessments of IQ (Dixonet al. 2014b). However, demonstration of the efficacy of the curriculum portion of the PEAK-DT to produce gains in language acquisition has yet to be evaluated. As previously mentioned, efficacy studies evaluating AVB assessment and derivative curriculums as a combined package are limited in the current literature. Evaluation of this kind is crucial for ensuring that learners receive the most effective treatment options available. Therefore, the primary purpose of the current study was to establish the efficacy of the PEAK-DT as a language-learning program for children with autism by comparing the pre and posttreatment PEAK assessment scores of children who received training using the PEAK curriculum versus the same scores obtained from a treatment-as-usual control group.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Forty children were recruited from an autism-focused special education day school in the mid-west USA. All participants had been in attendance of this day school for at least 3 months, had an IEP goal that included special instruction for language skills, and had been receiving services including special education instruction, speech and language therapy, art, music, and behavior support programming. The verbal repertoires of the participants ranged from minimal, having few to no receptive and expressive skills, to moderate functioning in which basic conversational skills were observed. None of the participants had previously been exposed to the PEAK Relational Training System. All participants had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, pervasive developmental disability (PDD-NOS), or a developmental delay. From these 40 participants, four were excluded due to the presentation of high-frequency or high-intensity problem behaviors that disrupted assessment or training procedures (e.g., aggression, elopement, and property destruction). Additionally, nine subjects were excluded from data analysis as they scored at the ceiling of the PEAK-DT assessment.

Of the participants included in the final analysis, 25 were male and two female. Eleven participants were between the ages of 5 and 10, six were between ages 11 and 15, and the remaining 10 were between ages 16 and 21. All participants had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder with seven having the additional diagnosis of intellectual disabilities.

Although not directly assessed for the purpose of this study, participant scores on the Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROPVT; Martin and Brownell 2011b) and Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOPVT; Martin and Brownell 2011a) were on file with the participants’ school. The ROPVT and EOPVT are two separate 190-item assessments that include norm-referenced pictures organized into a developmental sequence that reflect how well an individual can identify and label objects, actions, and concepts. ROPVT and EOPVT scores were included in this analysis in order to further assess the influence of preexperimental language skills on PEAK curriculum outcomes. Individual ROPVT and EOPVT scores are included in Table 1.

Setting and Stimuli

Assessment and trainings took place in the participant’s classroom or in one-on-one therapy rooms. Assessment sessions ranged from 20 to 120 min, and training sessions averaged 25 min per session. Various stimuli needed to administer assessments and run training programs were gathered from the classroom (e.g., picture vocabulary cards, toys, common items, and blocks). Arrays of preferred edible and tangible items were selected for each individual based on indirect assessment with classroom staff who frequently worked with that child. A brief preference assessment was conducted at the beginning of each session by presenting the array of available items to the child and asking the child, “What do you want to work for?” The item selected by the child, either vocally or through gesture, was used as a reinforcing stimulus for the remainder of the session.

PEAK: Direct Training Assessment

The PEAK-DT assessment (PDA) is one of four 184-item, criterion-referenced, sub-tests designed to assess an individual’s ability to learn and respond to verbal stimuli. The direct training assessment specifically evaluates an individual’s ability to learn language skills through direct contingencies (i.e., through reinforcement of specific verbal responses). Items on the PDA are organized by complexity along 14 numeric levels and include not only receptive and expressive skills but also function-based verbal operants such as mands, tacts, intraverbals, echoics, transcriptions, and autoclitics. The structure of the PDA numeric levels can be visualized as a triangle called the PEAK performance matrix. The first level of the performance matrix is at its highest point and contains two skills, 1A and 1B. Each descending level of the triangle has a greater number of programs as the triangle expands (e.g., level 14 has 26 items). An image of the PDA performance matrix can be seen in Fig. 1. PDA items are organized into discrete trial presentations. Each item begins with the examiner providing an instruction along with relevant stimuli. The participant was allowed up to 3 s to respond. If the participant responded correctly, a “yes” was recorded for that skill; incorrect responses were recorded as a “no.” If a response was not made within 3 s or a disruptive behavior was emitted, a block of 10 trials was run; if the child was able to correctly respond to nine of 10 trials, a “yes” was recorded for that item. Because disruptive behavior or non-attending on the part of the participant can lead to false positives and false negatives, the 10-trial probe sequence is recommended in order to ensure that the particular skill being evaluated is consistently present in the learner’s repertoire. For example, if the assessor asked the participant to match objects to identical objects but the participant selected a stimulus without looking toward the stimuli, the researcher would further assess the skill using the 10-trial probe. By doing so, the participant was unlikely to correctly “guess” nine out of 10 trials without looking. PDA scores range from 0 to 184 and were calculated by adding the total number of items responded to correctly (Dixon 2014a). Examiners began the PDA at the first item and continued along the alphanumeric coding until the participant responded to less than 20 % of items correctly for a given PDA alphanumeric row (i.e., each row of the PDA performance matrix). Reinforcement was not provided during assessment sessions for correct responding, but was provided to participants on the basis of compliance with the assessment procedure. Specifically, participants were provided access to the chosen reinforcer after every 10 trials.

Above image displays the PEAK direct training performance matrix. This triangle represents the 184 skills of the Direct Training Module and is organized such that 1A is the least complicated skill and 14Z represents the most difficult. Practitioners are advised to begin assessing and teaching skills at 1A and then to progress along the alphanumeric sequence

Training of assessors was conducted by a board certified behavior analyst (BCBA) and experienced PEAK practitioner. Training consisted of asking the assessors to read the PEAK-D manual, didactic instruction, modeling and demonstration of PDA, and feedback during role-play and rehearsal. Inter-observer reliability (IOR) of the PDA was conducted during implementation of the PDA via a second observer. This second observer independently coded a scoring sheet for each assessment item and compared to that of the examiner. IOR was calculated by dividing the number of items scored in agreement by the total number of items observed and then multiplied by 100 to gain a percentage of IOR. IOR was conducted for 30 % of all assessment sessions and was determined to be within the acceptable range, 92.3 % for empirical use.

PEAK: Direct Training Curriculum

The PEAK-DT contains 184 curriculum programs that mirror the 184 assessment items of the PDA. Each program includes information relating to the program’s goal, a list of stimuli typically used in the program, instructions on how to arrange and present stimuli, and a place for recording the stimuli used. PEAK programs are arranged in an alphanumeric order that corresponds to the PDA and thus can be used in conjunction with the assessment to determine appropriate programs for instruction. As with the PDA, training of PEAK-DT curriculum therapists consisted of a behavior skills training that included review of the PEAK-DT manual, instruction by a BCBA, modeling, and rehearsal with feedback.

Experimental Design and Procedure

A randomized experimental control group design was utilized to assess the effectiveness of training based on the PEAK-DT curriculum (Dixon 2014a). Of the 36 participants who were assessed using the PDA, nine participants scored 184 and were therefore excluded from further analysis. The remaining 27 participants were randomly assigned to a control group (n = 13) or a treatment group (n = 14). Both groups received the PDA at the onset of this study and again after 1 month. See Table 1 for individual participant’s group assignment, age, and pre-experimental ROPVT and EOPVT scores.

Control Group

Thirteen children were assigned to the control group. Control group participants received treatment as usual; no additional training was provided as a part of this study. This standard treatment consisted of group-based special education practices at the guidance of the students’ teachers according to existing individual educational plans created by a multidisciplinary team. No behavior analytic skill acquisition programs were in place, and no form of discrete trial training was occurring for these students. Daily activities included music therapy, speech therapy, social interactions, worksheet completion, and behavioral reduction interventions when needed.

Experimental Group

Fourteen children were included in the experimental group. For each participant in the experimental group, five programs from the PEAK-DT curriculum were selected based on the individual’s performance on the PDA. Initial programs were selected that corresponded to the five lowest alphanumeric assessment items that the participant incorrectly responded to during the PDA. Training sessions were conducted two times a week and consisted of discrete trial trainings. A typical discrete trial begins with the presentation of a discriminative stimulus or question. The individual was then allowed up to 3 s to respond. If a correct response was emitted, a reinforcing consequence was provided (e.g., praise, edible, and preferred activity). If an incorrect response or no response was emitted, a series of prompts were presented in order to evoke the appropriate response (see Dixon et al. 2014c for a thorough description of discrete trial procedures used in PEAK). Each participant was required to respond to one trial block for each program assigned. Trial blocks consisted of 10 trials covering 3–10 targets (as specified in the program) and were presented as 10 consecutive trials from each program. Mastery criteria for all programs were set at 90 % for three consecutive trial blocks or across 30 trials if conducted as mixed trials. When a program was mastered, the trainer selected the next lowest alphanumeric PEAK program that the participant had incorrectly responded to on the PDA. If participants responded to 90 % of trials on the first presentation of a new program, that program was considered mastered and the next program was assigned. Session lengths varied according to participant performance (i.e., participants who frequently responded correctly completed the session more quickly).

Each participant was exposed to up to three trainers. Trainers were graduate students in an Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) Master’s program and had previous experience conducting discrete trial training with children with autism. All trainers received a 30-min behavior skills training session on how to deliver PEAK programs. Trainers were required to read a task analysis of the training procedure, observe an experienced trainer implement PEAK programs, and participate in role-plays. Feedback was provided by the experienced trainer during role-plays as well as during in situ implementations.

Results

All 27 participants assigned to the experimental groups completed the study. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate the presence of significant differences between the treatment and control groups on changes in pretreatment to posttreatment scores on the PDA. Additionally, preexperimental scores on the ROPVT and EOWPVT, as well as the age of the participant, were evaluated for covariance with the main effect. See Table 1 for individual pre- and post-PDA scores. A significant effect was observed between experimental groups on the change from pre to posttreatment PDA, F(1, 22) = 9.684, p = .005. Participants in the treatment condition made statistically significant gains from pretreatment PDA (M = 51.57, SD = 40.81) to posttreatment PDA (M = 67.36, SD = 47.37), with 13 out of 14 participants demonstrating positive gains. Participants in the control group, however, did not demonstrate significant gains with six out of 13 participants scoring lower on the PDA in posttreatment (M = 34.92, SD = 49.11) than in pretreatment (M = 37.158, SD = 47.75). Pretest scores alone were not observed to be a significant indicator of change within the ANOVA model, F(1, 22) = .484, p = .494. Preexperimental ROPVT and EOPVT scores also were each found to be nonsignificant predictors of change in PDA scores, F(1, 22) = 1.833, p = .190 and F(1, 22) = 1.533, p = .229, respectively. Likewise, age in years was not observed to be a significant covariate of change in PDA, F(1, 22) = .012, p = .913.

In order to further explore the effects of PEAK-DT training on post-PDA scores, within-subject analysis of individual PDA for the experimental group was conducted. Participants in the experimental group were each assigned five PEAK-DT programs on the basis of their pre-PDA. If a participant mastered the program during the training phase, a new program was added. In some cases, mastery was achieved on the last day of training, in which case no new program was added. See Table 2 for information relating to the specific programs assigned for each participant. In total, 89 programs were assigned across the 14 participants in the treatment condition. Of the 53 skills trained to mastery across all participants during the experiment, 46 (87 %) were scored as present in the participants’ repertoire in the posttest PDA. Of the 33 programs not mastered by participants during the training phase, 13 (39 %) were scored as present in the posttest PDA tests. Because session time varied in length as a function of participant success, i.e., participants who responded accurately received less overall minutes in training (MIT), the number of minutes in training was compared with changes in the PDA scores as a possible covariate. The overall duration of exposure to PEAK trainings during this study ranged between 160 and 315 min across the entire month (M = 221 min, SD = 50 min); see Table 1 for individual MIT. Despite the large disparities between MIT, a significant correlation r(12) = .05, p = .852 was not found.

Discussion

The present data lend support to the assertion that exposure to the curriculum portion of the PEAK-DT is functionally related to gains on the PDA. The lack of skill gains in the control group, and indeed the decline of six out of 13 participants, further justifies this position. While not directly assessed in this study, the demonstration of convergent validity of the PDA with other non-AVB standardized assessments of language (Dixon et al. 2014a, b, c) extends the implication that the PDA in conjunction with the corresponding PEAK programs may provide instructors with a pragmatic instructional package for improving language deficits as measured by these assessments. Where the Peabody Picture Vocabulary and WISC-IV IQ assessments provide little information on how to remediate the particular deficits observed, the PEAK Relational Training Program provides explicit instruction for practitioners to follow. Additionally, the presence of such convergent validity between assessments allows clinical practitioners the ability to maintain the integrity of standardized tests, while instead relying on the PDA and associated curriculum for ongoing classroom assessment. These assertions, however, require further empirical examination (i.e., comparison of pretreatment/posttreatment scores on non-AVB assessments). It is also important to note that some disparity was observed between performance during the training phase and performance on the PDA. For example, five out of the 14 participants in the experimental group failed to obtain a positive mark on the PDA for a skill mastered during training. Likewise, six out of 14 gained at least one positive mark on the PDA on a skill that was introduced but not mastered during training. One explanation for this inconsistency in PDA outcomes is that the criterion used to conclude possession of the skill set in the repertoire may have been deemed not as comprehensive as the specific stimuli targeted during the DTT training. However, if this was the case, one might expect that greater gains would be seen in those that had longer durations of exposure to the DTT trainings, i.e., those who had longer MITs to have greater changes in PDA scores. Future studies should seek to provide a greater within-subject analysis to determine the extent to which specific training on PEAK-DT skills impacts the overall acquisition of language skills not directly taught.

Although the findings of the study were significant, several limitations to the generalizability of these results should be acknowledged. While statistically significant differences were detected between treatment groups, the relatively small sample size increases the potential of sampling error. The wide range of preexperimental variables such as functioning level, presence of disruptive behavior, and diagnosis may have also influenced statistical outcomes. As with all statistical examinations, the presence of statistically significant differences does not necessarily indicate the presence of clinically significant differences. Future research should include a larger sample size and appropriate counterbalancing to reduce the potential influence of such nuance variability. Because this study took place across a very brief period of time, the frequency of tracking and reassessing the participants may not adequately reflect the application of the PEAK Relational Training System as it would be implemented in a completely applied setting. For example, the PEAK-DT instructions (Dixon et al. 2014c) recommend reevaluation of learner skills via the PDA every 3 to 6 months, rather than the 1-month period of this study. The lack of procedural fidelity or independent variable integrity analysis may also limit generalization of the current findings to all implementations of the PEAK-DT curriculum. Although assessors and DTT trainers had all received BST style training, formal feedback was limited to rehearsals and not conducted in situ. Future research should include specific observations designed to measure the degree to which assessors and trainers remain faithful to the specified procedures. Additionally, the constraints on exposure to the PEAK curriculum imposed by the research design utilized in this study may not reflect how practitioners choose to implement training trials in applied settings. For instance, in this study, training sessions were limited to the time it took to complete ten trials for each program currently being targeted. In an applied setting, session lengths are likely to be longer and include many repetitions of the targeted skills. These limitations withstanding, this study presents one of the first control group-design evaluations of an entire AVB assessment and curriculum package. Though many behavior analytic researchers are comfortable with the experimental control found in single-subject demonstrations, the evaluation of program efficacy via large sample control group designs is the gold standard in psychological research. This demonstration, however, represents only the first step in evaluating the PEAK Relational Training Systems and further validating the AVB approach.

In summary, these data suggest that applied behavior analysis-based interventions, delivered for brief periods of time twice per week can have a significant impact on repertoire development of children with autism special education interventions. Furthermore, the insignificance of intervention duration on treatment outcomes suggests that even 10- to 20-min exposure twice per week of a child to the PEAK Relational Training System for a period of 30 days can have a meaningful outcome on that child’s repertoire. Although many parents and caregivers strive for maximizing intervention time and intensity, it is promising to see that even smaller levels of applied behavior analysis-based interventions are promising given that such levels are more practical in typical educational settings.

References

Dixon, M. R. (2014a). PEAK relational training system: Direct training module. Carbondale, IL: Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R. (2014b). PEAK relational training system: Generalization learning module. Carbondale, IL: Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R. (in press-a). PEAK relational training system: Equivalence. Carbondale, IL: Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R. (in press-b). PEAK relational training system: Transformation. Carbondale, IL: Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R., Carman, J., Tyler, P. A., Whiting, S. W., Enoch, M. R., & Daar, J. H. (2014a). PEAK relational training system for children with autism and developmental disabilities: Correlations with peabody picture vocabulary test and assessment reliability. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 26(5), 603–614. doi:10.1007/s10882-014-9384-2.

Dixon, M. R., Small, S. L., & Rosales, R. (2007). Extended analysis of empirical citations with Skinner’s verbal behavior: 1984–2004. The Behavior Analyst, 30(2), 197–209.

Dixon, M. R., Whiting, S. W., & Daar, J. H. (2014). The direct training module. In M. R. Dixon (Ed.), PEAK relational training system: Direct training module. Carbondale, IL: Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R., Whiting, S. W., Rowsey, K., & Belisly, J. (2014c). Assessing the relationship between intelligence and the PEAK relational training system. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1208–1213. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2014.05.005.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (2004). Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/download/statute.html.

LeBlanc, L. A., Esch, J., Sidener, T. M., & Firth, A. M. (2006). Behavioral language interventions for children with autism: Comparing applied verbal behavior and naturalistic teaching approaches. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 22, 2249–2260.

Lovaas, O. I. (2003). Teaching individuals with developmental delays: Basic intervention techniques. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Martin, N., & Brownell, R. (2011a). Expressive one-word picture test: Manual 4. Novato, CA: ATP Assessments.

Martin, N., & Brownell, R. (2011b). Receptive one-word picture vocabulary test: Manual 4. Novato, CA: ATP Assessments.

National Autism Center (2009). National Standards Report. Retrieved from http://www.nationalautismcenter.org/pdf/NAC%20Standards%20Report.pdf.

Partington, J. W. (2008). The assessment of basic language and learning skills—Revised (the ABLLS-R). Pleasant Hill, CA: Behavior Analysts.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

Sundberg, M. L. (2008). Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: The VB-MAPP. Concord, CA: AVB Press.

Sundberg, M. L., & Michael, J. (2001). The benefits of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 698–724. doi:10.1177/0145445501255003.

Tiger, J. H., Hanley, G. P., & Bruzek, J. (2008). Functional communication training: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis In Practice, 1(1), 16–23.

United States Surgeon General. (1998). Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2011). Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKeel, A.N., Dixon, M.R., Daar, J.H. et al. Evaluating the Efficacy of the PEAK Relational Training System Using a Randomized Controlled Trial of Children with Autism. J Behav Educ 24, 230–241 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-015-9219-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-015-9219-y