Abstract

Based on a review of articles published from 1990 to 2017, we provide insight into the overall positioning of the international entrepreneurship (IE) literature in terms of methodological issues and diversity. We also explore the impact of recommendations in earlier literature on methodology in subsequent research published after 2011. Finally, we evaluate methodological issues and diversity in studies undertaken to date in the context of emerging and developing countries. The research undertaken involved the review and analysis of one hundred and fifty eight studies. Methodologies were systematically analysed under different categories. We found that IE studies are to a great extent confined to mainstream international business and marketing journals. Our findings also demonstrate that IE studies focused on developed countries dominate those from emerging and developing countries, and remain highly skewed towards the European region. The preponderance of high-tech and knowledge-intensive firms as study samples is evident from our analysis. The subjective and objective ontological underpinnings remain the dominant philosophical stance among IE researchers. We also found that IE studies are almost equally dominated by both qualitative and quantitative research approaches. The increasing popularity of case study over other data collection strategies is evident. Although our analysis demonstrates that the domain of IE is still fragmented with knowledge gaps remaining that stem from country context, industry or sector context, ontological diversity, research approach and data collection and interpretation techniques, some progress has been made to the development of IE as a distinct body of knowledge. The findings of our study provide important implications for improving methodological rigor in future IE scholarship.

Resumen

Sobre la base de una revisión de los artículos publicados de 1990 a 2017, proporcionamos información sobre el posicionamiento general de la literatura sobre el espíritu empresarial internacional (IE) en términos de diversidad y problemas metodológicos. También exploramos el impacto de las recomendaciones en la literatura anterior sobre metodología en investigaciones posteriores publicadas después de 2011. Finalmente, evaluamos las cuestiones metodológicas y la diversidad en los estudios realizados hasta la fecha en el contexto de los países emergentes y en desarrollo. La investigación realizada incluyó la revisión y el análisis de ciento cincuenta y ocho estudios. Las metodologías fueron analizadas sistemáticamente bajo diferentes categorías. Descubrimos que los estudios de IE se limitan, en gran medida, a publicaciones internacionales de negocios y marketing. Nuestros hallazgos también demuestran que los estudios de IE centrados en los países desarrollados dominan los de los países emergentes y en desarrollo, y siguen siendo altamente sesgados hacia la región europea. La preponderancia de empresas de alta tecnología e intensivas en conocimiento como muestras de estudio es evidente a partir de nuestro análisis. Los fundamentos ontológicos subjetivos y objetivos siguen siendo la postura filosófica dominante entre los investigadores de IE. También encontramos que los estudios de IE están casi igualmente dominados por los enfoques de investigación tanto cualitativos como cuantitativos. La creciente popularidad del estudio de caso sobre otras estrategias de recolección de datos es evidente. Si bien nuestro análisis demuestra que el dominio de IE aún está fragmentado y que aún quedan lagunas en el conocimiento del contexto del país, la industria / sector, la diversidad ontológica, el enfoque de investigación y las técnicas de recopilación de datos e interpretación, se ha avanzado algo en el desarrollo de IE como un cuerpo distinto de conocimiento. Los hallazgos de nuestro estudio proporcionan implicaciones importantes para mejorar el rigor metodológico en la futura beca de IE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Summary highlights

Contributions: Based on a review of articles published from 1990 to 2017, we provide insight into the overall positioning of the IE literature in terms of methodological issues and diversity. Our contribution is further enhanced through the assessment of the impact of recommendations from past reviews on IE studies conducted beyond 2011. Moreover, we contribute to the literature by identifying methodological issues in studies undertaken in the context of emerging and developing countries. These contributions can serve to guide future studies and further the development of IE as a distinct and established body of knowledge.

Purpose: To address the question raised by Nummela (2014), viz. ‘how IE should be studied in the future’, this study undertakes a systematic review of pertinent literature incorporating IE studies published from 1990 to 2017. In particular, we aim to analyse the overall positioning of IE in terms of methodological rigor and diversity so that scholarly efforts can be directed towards making unique and novel contributions.

Methods and results: The findings of this study confirm that IE studies are to a great extent confined to mainstream international business and marketing journals with a tendency to focus on high-tech and knowledge-intensive firms originating predominantly from developed countries in the European region. Subjective and objective ontological underpinnings remain the dominant philosophical stance on the part of IE researchers. Contrary to previous review studies indicating the preponderance of the quantitative approach, an equal embrace of qualitative and quantitative research approaches is evident from our analysis. In terms of data collection strategy, the case study is found to be the most popular.

Limitations: Our study is not free from limitations. Since we eliminated books, book chapters, reports and conference publications, our list of reviewed articles is not inclusive. Additionally, our review and findings overlap to a limited extent with those of prior review studies. Moreover, given resource and time limitations, our review does not report the theoretical underpinnings nor the dependent and independent variables and unit of analysis employed in IE studies.

Theoretical implications: Though not substantial, some progress is evident from our review in the development of IE as a distinct and established body of knowledge. IE scholars should direct their focus to neglected countries or regions, and industries or sectors, and utilise those research methods and techniques that are seldom used given that the significance of context and generalisability of findings to different settings in the development of a good theory have been much emphasised in the management literature. In addition, there have been increasing calls for more richness and practical relevance in IE research.

Practical implications: Our review suggests that the share of emerging and developing countries in IE studies remains marginal. Since emerging and developing countries have become major players in international business and they are different both institutionally and culturally from their advanced counterparts, there is a need to draw samples from less-studied emerging and developing countries in IE studies. A lack of government support, various bureaucratic complexities and minimal cooperation from the top management of international firms in emerging and developing countries are thought to be a hindrance in undertaking research activities in these countries. Some support mechanisms from governments and cooperation from firms’ top management in emerging and developing countries can be of great help in this regard.

Introduction

The aim of our study is to analyse the overall positioning of international entrepreneurship (IE) in terms of methodological approach and diversity, and make recommendations so that future scholarly efforts can be directed to the development of IE as a distinct and established body of knowledge going beyond traditional practices. There have been increasing calls for more research and greater rigor and richness of theoretical knowledge around IE (Cavusgil and Knight 2015; Coviello et al. 2015; Nummela 2014). Nummela (2014) has raised the question as to how IE should be studied in the future. Guiding future research in the right direction involves undertaking a systematic review of pertinent literature. Although IE has been enriched from research since the early 1990s, a number of reviews consider that IE is still an emerging field with a growing body of knowledge (Coviello et al. 2015; Peiris et al. 2012). Based on a detailed analysis of 7651 citations, stemming from 287 documents, Etemad and Lee (2003) argued that IE is a rich, yet a young field which is facing rapid change and several challenges. According to Etemad (2018, p. 112), although IE as a young field has advanced and evolved over the past three decades, its ‘expansion and evolution has not been organised and systematic, but organic and issue driven’. A similar trend is evident from a number of past reviews which suggest that IE is still a fragmented field, and in its infancy stage (Evers et al. 2012; Gray and Farminer 2014; Keupp and Gassmann 2009). However, others believe that the field has matured over the past decades (Verbeke and Ciravegna 2018), and has become an important body of knowledge, with an increasingly established position (Baier-Fuentes et al. 2019). Consistent with a number of scholars, we believe that the theory of IE needs to be enriched from different theoretical, empirical and methodological perspectives (Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, b; Cavusgil and Knight 2015; Coviello et al. 2015) to increase its methodological rigor (Nummela 2014) and to be a claimant of a distinctive body of knowledge from its parent disciplines (Coviello et al. 2015).

It is argued that the validity and generalisability of a study are affected directly by the methodologies employed (McGrath and Brinberg 1983), and hence, methodologies play a critical role in international business (IB) in terms of knowledge development (Yang et al. 2006). This underlines the importance of understanding the customary and intermittent practice (Yang et al. 2006) in the IE field. A research field becomes more powerful when its applicability is established and broadened to different theories, country contexts (Kiss et al. 2012), industry contexts and data collection and analysis methods. Although concern for methodological rigor in terms of research design, data collection and analysis methods, and for the means to improve the validity and reliability of the research process and output in IE research is not new, methodologically, the field has not yet advanced to a large extent (Nummela 2014). As noted earlier, she had therefore raised the question of how IE should be studied in the future (Nummela 2014). Addressing this question requires undertaking a systematic review of pertinent literature so that scholarly efforts can be directed towards making unique and novel contributions that surpass traditional approaches. A number of studies have sought to identify methodological issues manifested in theoretical knowledge on IE (see Coviello et al. 2015; Coviello and Jones 2004; Jones et al. 2011; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Kiss et al. 2012; Peiris et al. 2012). However, these reviews were undertaken from 1989 to 2004 (see Coviello and Jones 2004), 1989 to 2009 (see Jones et al. 2011), 1994 to 2007 (see Keupp and Gassmann 2009), from the year of initial publication through January 2011 issue (see Kiss et al. 2012), 1993 to 2011 (see Peiris et al. 2012) and since inception up until 2012 (see Coviello et al. 2015). This indicates that methodological trends beyond 2011 have yet to be explored. We divide our review into two periods to explore the impact of recommendations from past reviews on studies conducted beyond 2011 to understand the recent trend. In particular, a lack of knowledge about methodological issues in IE studies beyond 2011 requires research focusing on the extent to which IE has evolved and benefited from the past reviews. Moreover, while a number of these reviews involved identifying theoretical frameworks employed in IE, others focused on identifying antecedents, determinants and business strategies of born global firms/international new ventures. In doing so, these studies tended to focus less on the research methods employed in IE studies. Therefore, there is a need to review the range of studies published from the 1990s to 2017 to analyse the overall positioning of IE in terms of methodological approach and diversity. A further limitation of prior reviews is that none of them has explored the methodological issues in IE studies that have been undertaken in the context of less-developed countries with one exception (see Kiss et al. 2012). Their study incorporated articles from the year of their initial publication through the January 2011 issues and was confined to emerging economies. However, methodological trends in studies undertaken in emerging economies beyond 2011 have not yet been explored. Furthermore, focusing only on emerging economies or countries may lead to the overlooking of those studies undertaken in less-developed countries.

Therefore, through a review of one hundred and fifty eight studies that were published from 1990 to 2017, we aim to contribute to the extant literature by identifying a number of methodological issues, trends and knowledge gaps in the IE literature, and thereby provide guidelines for future scholarship. We contribute to the literature by providing insight on the overall positioning of IE literature in terms of methodological issues and diversity. Since it is argued that past methodological reviews led to academic and methodological rigor in the IE field (Peiris et al. 2012), it is instructive to assess the impact of past reviews on subsequent research. We thus contribute to the literature by exploring the impact of recommendations from past reviews on studies conducted beyond 2011. Finally, we contribute to the literature by identifying methodological issues and diversity in studies undertaken in the context of emerging and developing countries. Six studies focused on methodological issues are used to complement our review (i.e. Coviello et al. 2015; Coviello and Jones 2004; Jones et al. 2011; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Kiss et al. 2012; Peiris et al. 2012).

The rest of our paper is structured as follows. An overview of literature around IE is presented in the “Overview of literature on IE” section. Subsequently, in the “Research approach” section, we discussed our research approach employed for this review. The results related to the overall methodological positioning of IE are presented in the “Results” section. In the “Review of studies undertaken in emerging and developing countries (1990–2017)” section, we explore the methodological trends and patterns in studies from emerging and developing countries. Finally, a discussion and the implications of our findings are provided in the “Discussion and implications” section, followed by some concluding remarks in the “Conclusion” section.

Overview of literature on IE

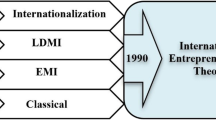

The paper by Oviatt and McDougall in 1994 ‘Towards a Theory of International New Ventures’ published in Journal of International Business Studies was instrumental in generating scholarly interest in IE. With the evolution of IE as a body of knowledge, different definitions are evident in the literature which corresponds to the interdisciplinary nature of the field. In particular, IE is argued to have its origins within three distinct perspectives: strategic management, entrepreneurship and IB (Dimitratos and Jones 2005; Jones and Coviello 2005; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Zahra and George 2002; Zucchella and Scabini 2007). Taking into consideration the strategic management perspective, McDougall and Oviatt (2000, p. 903) define IE as ‘a combination of innovative, proactive and risk-taking behaviour that crosses national borders and is intended to create value in organisations’. The proponents of the entrepreneurship perspective maintain that IE involves ‘the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities to introduce new goods and services, ways of organising, markets, processes and raw materials through organising efforts that had no existence previously’ (Shane and Venkataraman 2000, p. 218). The underlying assumption of this perspective is that IE is the nexus of individuals and opportunities (Di Gregorio et al. 2008). The third perspective from IB considers IE as ‘the discovery, enactment, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities across national borders to create future goods and services’ (Oviatt and McDougall 2005, p. 540). Oviatt and McDougall (1994) first integrated these perspectives in their endeavour to develop a new model of IE.

Since its inception, the field of IE has benefited from two streams of studies (Lu and Beamish 2001). The first stream is related to born global firms (BGFs) or international new ventures’ (INVs) studies. More specifically, to date, many studies using a variety of terms have been undertaken in this field, for example born global firms (Knight and Cavusgil 2004; Madsen and Servais 1997; Rennie 1993), international new ventures (McDougall et al. 1994) and early or rapidly internationalising firms (Rialp et al. 2005; Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, b, c). The first stream of IE research is concerned with explaining and understanding the underlying factors influencing firms’ early or rapid internationalisation (Rialp et al. 2005) and focused on newly established small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Keupp and Gassmann 2009). The discovery, evaluation and exploitation of foreign market opportunities early in a firm’s life cycle feature the firm as either a BGF or INV. The use of ‘born’ and ‘new’ in the definitions of a BGF and INV highlights the importance of earliness in internationalisation (Verbeke and Ciravegna 2018). And ‘early internationalisation is still a novel approach in firms’ international expansion literature’ (Cavusgil and Knight 2015, p. 11). This has become the basis for a critique of mainstream IB research focused on internationalisation (Verbeke and Ciravegna 2018), particularly behavioural theories explaining firms’ internationalisation. With regard to the second stream, researchers examine IE among established firms irrespective of their size and age. IE should not be examined by confining it solely to the first stream of research but needs to broaden its boundaries by including firms irrespective of their size and age (Dimitratos and Jones 2005; McDougall and Oviatt 2000; Zahra and George 2002) since established firms also adopt a rapid and aggressive internationalisation strategy similar to a born global internationalisation pattern (Bell et al. 2003).

Since the early 1990s, the growing importance of IE has been reflected in the considerable number of studies undertaken (see Cavusgil and Knight 2009, 2015; Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Knight and Cavusgil 2004; Madsen and Servais 1997; Oviatt and McDougall 1994; Rennie 1993; Rialp et al. 2005; Sharma and Blomstermo 2003). Over the past decades, the increasing globalisation of markets has stimulated scholarly attention towards IE (Kiss et al. 2012). The paramount importance of entrepreneurship to the economic prosperity of a country and economic well-being of entrepreneurs is well documented. However, in this era of rapid globalisation, entrepreneurial engagement beyond national borders is even more important and required for a variety of reasons (Ahmed and Brennan 2019c). For example, entrepreneurial activities across borders in the form of exporting help a country to integrate into the world economy, generating foreign revenue that can lessen the pressure on the balance of payments, reduce the impact of external shocks on the domestic economy (Abou-Stait 2005), increase domestic production, decrease the unemployment rate and meet import expenditures of a country (Shamsuddoha 2004). For a firm, international engagement, particularly exporting, helps to achieve economies of scale, market diversification, different growth rates in different markets and stability advantages (Czinkota 1994). Therefore, understanding the mechanism instrumental to the initiation and success of IE is of vital importance for theory, policy and practice.

Research approach

Past reviews suggest that the theoretical knowledge around IE tends to be developed country-centric and is confined largely to high-tech industry or sectors (Peiris et al. 2012; Reuber et al. 2015). Understanding the extent to which theoretical knowledge has proliferated to a broader set of countries and industries is of vital importance to the development of a good theory. There have been increasing calls for more richness in IE research through the application of diverse and complex research methodology and methods, particularly examining IE-related phenomena in different settings, and from different ontological stances, and using those research approaches, data collection and analysis methods that are seldom used (see Coviello et al. 2015; Coviello and Jones 2004; Jones et al. 2011; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Peiris et al. 2012). It is important to assess the extent to which these calls have been addressed in the literature. In this study, the methodologies pertaining to IE studies are therefore systematically evaluated by focusing on the country context, industry or sector context, ontological underpinnings, research approach and data collection and analysis methods. Of the reviewed studies, empirical articles (collection and analysis of primary and/or secondary data as stated by Sin and Ho 2001), conceptual papers and literature reviews are included for analysis. This study excludes those that claim to be IE, although they are not as argued by Coviello et al. (2015). A number of articles published within the domain of IE are outside of this field and thus researchers must be careful ‘in understanding what IE research is and what it is not’ (Coviello et al. 2015, p. 11). Thus, in the selection of articles, this study has embraced the protocol suggested by these researchers.Footnote 1 A number of articles were rejected as they primarily focused on SMEs rather than IE per se, and focused on biotech firms in global industries, technological innovation rather than business or entrepreneurial processes, entrepreneurship in home country, cross-cultural examination of entrepreneurial orientation dealing with scale and measure development or validation, and transnational and diaspora entrepreneurship (Coviello et al. 2015). In addition, books, book chapters, reports and conference publications were excluded from our analysis (Jones et al. 2011) since they are not widely accessible and/or peer reviewed (Coviello and Jones 2004; Jones et al. 2011). Our systematic literature search involved using the following databases: ABI/INFORM Global, EBSCO Host, Emerald full-text database, Google Scholar, ProQuest and SpringerLink (iRel). The following keywords: international entrepreneurship, born global firms, born internationals, born again globals, international new ventures, global start-ups, early and rapidly internationalising firms were used in locating pertinent articles using the above electronic databases. Full access to the reviewed studies was facilitated from the utilisation of a leading European University’s Library directory. From the systematic literature search, we located more than two hundred studies. The majority of these articles were screened after reading them fully, while a small number of the articles were screened based on reading the abstract and methodology/methods and data analysis and interpretation sections. The protocol that we used to select IE studies resulted in one hundred and fifty-eight studies suitable for analysis.

Results

The reviewed one hundred and fifty-eight studies were published in a number of leading journals. However, it should be noted that the reviewed articles were not only confined to top journals in the respective field (Jones et al. 2011); rather, the selection of articles ‘was based on the aim of capturing the theoretical and empirical contributions that have added value to the IE field’ (Peiris et al. 2012, p. 281). The distribution of selected and reviewed published studies among these journals is provided in Appendix Table 8. Our findings in Appendix Table 8 indicate that the majority of the analysed studies were published in eight leading international business and marketing journals: Journal of International Entrepreneurship (approx. 29%), International Business Review (approx. 14%), Journal of World Business (approx. 11%), Journal of International Business Studies (approx. 7%), Journal of International Marketing (approx. 6%), International Marketing Review (approx. 5%), Journal of Business Venturing (approx. 4%) and Management International Review (approx. 4%). Of the reviewed studies, fourteen (approx. 9%) were published in mainstream entrepreneurship journals, i.e. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice (5%), Entrepreneurship and Regional Development (approx. 2%), Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development (approx. 1%), Small Business Economics (approx. 1%) and Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal (approx. 1%). This finding indicates that IE studies are to a large extent confined to mainstream IB and marketing journals which has an implication for IE as a research field. The implication of this finding is addressed in the “Discussion” section.

As noted earlier, the reviewed articles were systematically analysed (frequency analysis) under different categories, i.e. country context, industry or sector context, philosophical stance, research approach and data collection and interpretation methods or techniques, to identify the key methodological patterns. Of the analysed one hundred and fifty-eight studies, five were literature reviews, nineteen conceptual papers and the remaining one hundred and thirty four were empirical papers.

Results pertaining to country context

Of the analysed one hundred and thirty-four empirical papers published between the 1990s and 2017, developed countries were sampled in the majority of IE studies (approx. 78%), followed by emerging and developing countries (approx. 24%). In these studies, sixteen drew on samples from two developed countries, while nine were developed multi-country studies. Our results also indicate that two incorporated samples from both developed and developing countries. Our results demonstrate the marginal representation of sample firms from emerging and developing countries. In terms of geographical distribution, a majority of IE studies were based in the European region (71, representing approx. 53% of the total share), followed by the Asian (31, representing approx. 24% of the total share), American (29, representing approx. 22% of the total share), Australian (19, representing approx. 15% each of the total share) and African (2, representing approx. 2% of the total share) regions. It should be noted that a number of studies used a combination of countries from different regions. Therefore, the cumulative percentage cannot be accumulated to equal the total number of reviewed studies.

Among the total analysed studies, the USA was the most popular context, appearing in twenty studies (representing approx. 15% of the total share), followed by Finland (18 studies which represent approx. 14% of the total share), Australia and China (14 each, representing approx. 11% each of the total share), and Spain (12 studies which represent 9% of the total share). While New Zealand and the UK each featured in ten studies (approx. 8% each of the total share), Germany featured in nine and Denmark appeared in eight studies (representing approx. 7% and 6% of the total share respectively). Ireland and Sweden each appeared in seven studies (approx. 5% each of the total share). Since a number of studies used a combination of countries, the cumulative percentage thus cannot be accumulated to equal the total number of reviewed studies. Summary results related to studies’ country and regional contexts are provided in Table 1, while the complete distribution of studies by country is reported in Appendix Table 8.

Now we consider the country context utilised beyond 2011 to assess the evolution of IE based on recommendations from past reviews. From the reviewed one hundred and fifty-eight studies, we found sixty-seven studies that were published beyond 2011(between 2012 and 2017). Of the sixty-seven studies, two were literature reviews, eight conceptual papers and the remaining fifty-seven were full research (empirical) papers. Among the analysed studies, as expected, IE studies in the context of developed nations dominate those relating to emerging and developing countries. In particular, forty studies (representing 70% of the total share) have drawn samples from developed countries, and the remaining seventeen (approx. 30%) were undertaken from the perspective of emerging and developing countries. In terms of geographical distribution, results in Table 1 indicate that countries from the European region were represented in a majority of IE studies (appeared in 31 studies, representing approx. 55% of the total share), followed by the Asian region (featured in 14 studies, representing approx. 25% of the total share), the American region (utilised in 9 studies which represent approx. 16% of the total share) and the Australian region (appeared in 5 studies, representing approx. 9% of the total share). Of these studies, eight have drawn samples from two or more countries in different regions. Table 1 indicates that among the studies conducted in emerging and developing countries, China is the most popular context, featuring in six studies (representing approx. 11% of the total share), followed by Brazil (3, representing approx. 6% of the total share) and India (2, representing approx. 4% of the total share). As far as the frequency of developed countries is concerned, Spain as a study context dominate in IE publications as this country is featured in seven studies (representing 12% of the total share). While Finland and the USA appeared in six studies each (representing approx. 11% each of the total share), and Australia and Italy featured in five each (representing approx. 9% each of the total share). Denmark, Germany and Sweden featured in four studies each (representing 7% each of the total share), followed by Ireland in three studies (representing approx. 6% of the total share). Of these studies, a limited number of cross-country comparison and multi-country studies are evident from our analysis.

Results pertaining to industry/sector context

Among the analysed studies, high-tech firms remain the most frequently studied (approx. 42%), followed by SMEs (approx. 32%). However, we also observed the existence of high-tech or knowledge-intensive firms in the SME category.Footnote 2 It should be noted that high-tech or knowledge-intensive industries or sectors are considered as those that have drawn sample firms from the airline industry, biotechnology firms, home appliances, software, IT, PC/mobile phone manufacturers, internet-based firms, medical and wireless technology-oriented firms, and wind turbine. Firms from different industries or sectors, irrespective of their technological intensity and nature of business, were the third most frequently studied (approx. 29%). The marginal representation of firms from the agriculture-based industry or sector is evident from our analysis. The results are reported in Table 2. It should be noted that a number of studies have drawn their sample from a combination of industries and/or sectors. Therefore, the cumulative percentage cannot be aggregated to equal the total number of reviewed studies.

Now we report the findings on the industry or sector context used in IE studies beyond 2011 (comparisons between 1990–2011 and 2012–2017 periods are discussed in the “Discussion” section). Our analysis in Table 2 reveals that in a large number of IE studies, SMEs were drawn as sample firms (approx. 34%), followed by firms from different industries/sectors and high-tech firms (approx. 32% each). Firms from different industries or sectors consist of both high-tech and low-tech firms, as well as both manufacturing and service-oriented firms.

Results related to philosophical stance, and data collection and interpretation methods

IE phenomena to date seem to be explored equally from either an objectivist or subjectivist ontological position. Over the past three decades of scientific inquiry, the negligible use of pluralistic approaches in examining topics related to IE is evident from our analysis (approx. 11%). Our findings suggest that IE research is almost equally dominated by both the quantitative (approx. 46%) and qualitative (approx. 45%) research approaches. In terms of data collection strategy, our analysis indicates that the case study was adopted in a large number of studies (approx. 45%), followed by the survey (approx. 31%). Secondary data sources, namely database, IPO prospectus, registers, websites, reports, government publications and other available secondary data sources, were employed in nineteen studies (representing approx. 15% of the total analysed). Both the survey and case study methods were also employed together in fourteen studies (representing approx. 11%). Of the reviewed studies, both the quantitative (approx. 46%) and qualitative (approx. 45%) data analysis techniques have been revealed to be equally popular techniques among IE researchers, followed by mixed methods (approx. 9%). The results are reported in Table 3.

Now we report the findings on ontological stance, research approach and data collection and interpretation methods prior to and beyond 2011 (comparisons between 1990–2011 and 2012–2017 periods are discussed in the “Discussion” section). Results in Table 4 suggest that objectivism (approx. 50%) and subjectivism (approx. 44%) remain the dominant ontological positions beyond 2011. Pluralistic underpinnings are evident in the case of a small number of studies (7%). In terms of research approach, our analysis indicates that IE research undertaken over the last 6 years has been almost equally dominated by quantitative (approx. 48%) and qualitative (approx. 44%) approaches. As far as data collection strategy and analysis methods are concerned, our analysis demonstrates that a majority of studies embraced the case study (approx. 44%), followed by the survey (approx. 37%). Both the survey and case study methods are also employed together in a small number of studies (4), representing about 7% of the share. Moreover, the share of secondary data sources, namely database, firm registers, government publications, IPO prospectus, publication office of the EU, register and other secondary data sources in IE studies, is approximately 13%. In terms of data analysis, we found almost an equal representation of both quantitative (approx. 48%) and qualitative interpretations (approx. 44%). The remaining studies (approx. 9%) utilised mixed data analysis methods.

Review of studies undertaken in emerging and developing countries (1990–2017)

As highlighted earlier, of the one hundred and thirty-four analysed studies, a small number of studies (32) were undertaken in the context of emerging and developing countries, representing approximately 24% of the total analysed. Of these thirty-two analysed studies, twenty-six were based on a single country study, and the remainder had drawn sample firms from two or more countries. This is an indication of less enthusiasm for cross-country and multi-country studies. The results are reported in Table 5. Among the thirty-two reviewed studies, China as a study context dominates other emerging and developing countries. In particular, China (sampled in 14 studies) has the highest representation (approx. 44% of the total share within the emerging and developing country sample), followed by Brazil and India (4 each, representing approx. 13% each of the total studies). While Malaysia was featured in three studies (representing approx. 10%), Mexico, Russia, Turkey and Vietnam were featured in two studies each (representing approx. 7% each of the total studies). Among these studies, three BRIC countries dominate other emerging and developing countries. This finding is consistent with the extant literature (e.g. Peiris et al. 2012). Peiris et al. (2012) systematically reviewed 291 journal articles on IE published between 1993 and 2012. They have documented the marginal representation of developing countries in IE studies, particularly countries from the South Asian and African regions.

In terms of industry or sector context, since the beginning of IE research, researchers have been incorporating or examining firms from high-tech or knowledge-intensive industries or sectors with a specific focus on SMEs. This has been evident in almost all studies dealing with methodological issues in IE (e.g. Coviello and Jones 2004; Peiris et al. 2012; Zahra and George 2002). In this study, we have established a similar pattern. Among the analysed studies in emerging and developing countries, sample firms from high-tech or knowledge-intensive industries or sectors have the highest representation (approx. 44%), followed by SMEs (approx. 38%), and firms from different industries or sectors (approx. 32%), irrespective of their technological intensity and nature of business. The results are reported in Table 6. It should be noted that a number of studies have drawn samples from a combination of industries and/or sectors. Therefore, the cumulative percentage in Table 6 cannot be accumulated to equal the total number of reviewed studies. For example, in SMEs and firms from different industries category, a number of firms belong to the high-tech category.

Our results corresponding to the ontological stance, research approach and data collection and interpretation methods in IE studies conducted in emerging or developing countries reported in Table 7 suggest the prevailing preference of an objectivist ontological position (approx. 60%) over subjectivist (approx. 38%). The pluralistic underpinnings are evident in the case of one study, accounting for only 3% of the share. IE research undertaken in emerging/developing country contexts was dominated by the quantitative research approach (approx. 63%), followed by the qualitative approach (approx. 38%). As far as data collection and analysis methods are concerned, more than half of IE studies in emerging and developing countries deploy the survey (approx. 54%) with quantitative interpretation (approx. 63%), followed by the case study (approx. 38%) with qualitative data analysis (approx. 38%). In addition, both the survey and case study methods were employed together in a single study. This implies that primary data has been used for the most part in approximately 92% of studies. The database and other available secondary data sources were used in only two studies, accounting for approximately 7% of the share.

Discussion and implications

Journal outlets

Of our reviewed studies, approximately 42% were published beyond 2011. Our analysis reveals that mainstream IB and marketing journals have published a majority of the reviewed studies (approx. 80%), followed by entrepreneurship journals (approx. 9%). Such a narrow focus limits the disseminations of knowledge to wider scholarly communities. Our analysis also indicates that publication of IE studies in mainstream management journals is insignificant. One plausible explanation for this could be that studies in this field focus less on the management practices and issues. Consistent with Terjesen et al. (2016), we argue that IE is not well communicated to scholars outside the entrepreneurship and/or marketing field, and this is problematic due to its interdisciplinary nature. They further argued that ‘scholars should have open lines of communication in order to share and build upon related findings’ (Terjesen et al. 2016).

Hambrick and Chen (2008, p. 32) have developed a model where they proposed three criteria: differentiation, mobilisation and legitimatisation, to explain ‘the development of new academic fields as part of an admittance-seeking social movement’. Coviello et al. (2015, p. 1) in their review study used these criteria to address the question of whether or not IE has developed itself as a field. Legitimacy is argued to involve both intellectual persuasion and emulation of norms in the parent or adjacent fields (Hambrick and Chen 2008; cited in Coviello et al. 2015). In terms of emulation, it is argued that some progress have been made, reflected by publications in top-tier IB or entrepreneurship journals. However, outside of the parent disciplines, much work is required, because most IE studies are not published in strong journals (Coviello et al. 2015) and are confined mostly to IB and entrepreneurship journals (Jones et al. 2011). Despite this recommendation, our findings suggest that the mainstream IB, marketing or entrepreneurship journals remain the main focus among IE scholars, thus indicating that emulation has not occurred to any great extent in the field.

Country context

Our results indicate that theoretical knowledge on IE is skewed towards developed countries. Although in recent years, some studies have focused on firms from emerging countries, particularly three BRIC countries; IE studies from emerging and less-developed countries are still relatively few. Although the equivocal and hostile institutional environments of less-developed countries make them atypical, there is scant research that draws on sample firms from developing countries (Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, c). Beyond the dearth of research from developing country contexts, the challenging institutional environments for entrepreneurship make these countries critical from a theoretical perspective (Ahmed and Brennan 2019c). Our findings are consistent with the extant literature (e.g. Peiris et al. 2012; Reuber et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2006). It should also be noted that developing countries are not only under-represented in IE literature, but they are also largely overlooked in IB scholarship in general. For example, a study on methodologies in IB undertaken by Yang et al. (2006) revealed that some regions like Africa and countries like Bangladesh are under-researched by IB researchers.

Our results (in Table 1) indicate that over the past 6 years, researchers have increased their focus on a number of developed countries. For example, there have been increasing numbers of studies on Spain (approx. 13%); Denmark, Germany and Sweden (approx. 7% each); Ireland (approx. 6%); and Belgium, Greece and France (approx. 4% each) during the past 6 years compared to the previous 21 years (1990–2011). Surprisingly, our analysis indicates that Italy as a study context was not utilised prior to the period 2012. However, beyond 2011, a negligible number of studies undertaken in the context of UK (approx. 2%) compared to approximately 12% in the previous 21 years. Moreover, New Zealand and Norway featured only in two studies each (representing approx. 4% each) compared to approximately 11% and 6%, respectively, in 1990–2011. Canada as a study context was not utilised at all following 2011.

Although our overall results suggest that emerging and developing countries are under-represented in the IE field, our analysis indicates that researchers have increased their focus on these countries (approx. 30% of the total share), particularly on BRIC countries beyond 2011 compared to the period 1990–2011 (approx. 20% of the total share), suggesting beneficial impact of past reviews. For example, there have been more studies on China (approx. 11%), followed by Brazil (approx. 6%), India (approx. 4% each), and Mexico and Russia (approx. 2% each) during the 6 years following 2011 than in the previous 21 years (1990–2011).

As far as the geographical distribution is concerned, IE studies are highly skewed towards the European region, followed by the Asian, American and Australian regions. However, there have been a small number of studies undertaken in the context of American and Australian regions, and no study from the perspective of the African region is evident during the 6 years compared to the previous 21 years (1990–2011). Our analysis (in Table 1) reveals that research in the context of both European and Asian regions has increased during the 6 years in comparisons to the previous 21 years. Although our study demonstrates the prevalence of IE studies in different parts of the world, countries from the African, South American, South Asian and the Middle-Eastern regions are under-represented. This finding supports a number of prior review studies (Peiris et al. 2012; Reuber et al. 2015). Peiris et al. (2012) systematically reviewed 291 journal articles on IE published between 1993 and 2012. They found that the literature around IE in the context of developed countries is abundant. However, studies from countries in the South American, South Asian and African regions are marginal in the IE field (Peiris et al. 2012). Similarly, a bibliographic study undertaken by Reuber et al. (2015) revealed that a majority of studies related to IE emanates from developed economies. Based on a review of prior studies, Nummela (2014) argued that literature around firms’ early or rapid internationalisation is confined to findings from the West.

Our findings suggest that recommendations made in past reviews on utilising samples from under-represented countries (particularly less-developed countries) and regions (such as South Asian, African, South American and the Middle-Eastern regions) were followed intermittently. This is problematic for IE as a research field for two reasons. First, it is well documented that developed and developing countries differ significantly in many economic and social aspects. Entrepreneurial behaviour is argued to vary across countries and regions due to differences in institutional profiles, culture and social settings (see Busenitz et al. 2000; Mitchell et al. 2002; Kreiser et al. 2010). Therefore, the generalisability of findings found so far in the context of developed countries turns out to be a theoretical issue for IE (Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, c). An over reliance on particular contexts, which is evident in both internationalisation and comparative studies, may result in inaccurate generalisations to other unfamiliar contexts (Kiss et al. 2012). Reynolds (1991, p. 245) argued that ‘finding the same empirical patterns in different countries provides evidence that the same explanations of entrepreneurial phenomena have broad empirical support and, hence, deserve greater confidence for applications in any one situation’.

Second, theoretical knowledge is argued to develop in an idiosyncratic response to local conditions and trends (Jing et al. 2015). Context-specific research thus can observe the local specificities (Ferreira et al. 2015). According to Kiss et al. (2012), a theory becomes more powerful when its applicability is established in different and novel contexts. Therefore, studies focusing on under-represented countries or regions such as developing and emerging countries can significantly deepen and broaden context-specific theoretical knowledge on the behaviour of international entrepreneurs (Peiris et al. 2012). Consistent with Kiss et al (2012), we argue that a broader geographic concentration has the maximum potential to provide new insights that can lead to new theoretical developments in this field. Reuber et al. (2018, p. 402) argued that little knowledge exists in the IE field about the ‘mechanisms underlying successful coopetition among heterogeneous and geographically dispersed international opportunity seekers, and the outcomes they produce over time’.

Our findings also indicate that a vast majority of studies in the IE field were single country-based and cross-sectional in nature. Single country samples were found to dominate in IB research in general (see Yang et al. 2006) and IE literature in particular. This finding is consistent with the extant literature. For example, the preponderance of studies based on a single country is evident in methodological reviews undertaken by Coviello and Jones (2004), and Zahra and George (2002). Similarly, IE studies that were cross-sectional in nature were found to dominate over longitudinal study design (see Coviello and Jones 2004; Coviello et al. 2015; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Kiss et al. 2012). A number of these researchers have therefore urged that IE phenomena be examined in multiple countries and that a longitudinal study design be adopted. Our findings suggest that the recommendations made in prior reviews on undertaking cross-country comparisons/multi-country studies and adopting a longitudinal study design have not been followed in IE research.

The inclination towards undertaking single country-based and cross-sectional studies is another key obstacle in the development of IE as a research field. To test the validity of extant theory and increase the generalizability of extant findings, there is a greater need to examine IE phenomena from a multi-country perspective. Terjesen et al. (2016, p. 324) argued that ‘comparative research can lead to common understandings of definitions and methods across multiple levels of analysis. The results will indicate whether there are generalizable patterns—similarities as well as differences—across countries or country groups, leading to the development of better theories’. In addition, since time is considered as a critical dimension of entrepreneurial opportunity identification, creation and exploitation (Baron 1998), the preponderance of cross-sectional studies seems problematic (Keupp and Gassmann 2009, p. 612). Experimental and longitudinal studies can explore the complex social processes that evolve over time. This is particularly important for studies focusing on the performance/competitiveness and growth of born global firms/international new ventures’/early internationalising firms. According to Rajulton (2001, p. 171), ‘social processes have become increasingly complex and if we would like to grasp this complexity, we need longitudinal data for establishing temporal order, measuring change and making stronger causal interpretations’. Consistent with Keupp and Gassmann (2009, p. 614), we argue that future IE scholars examining IE as the intersection of internationalisation and entrepreneurship can benefit from longitudinal study designs, because ‘just like internationalisation, entrepreneurship is a process, rather than a static phenomenon. It is essentially a planned behavior that develops over time and interacts with its environment’.

Industry/sector context

Our results demonstrate that IE studies have predominantly concentrated on samples originating from high-tech and/or knowledge-intensive industries or sectors, although high-tech and knowledge-intensive firms differ significantly from those of low-tech firms. This finding supports prior review studies (see Coviello and Jones 2004; Peiris et al. 2012; Zahra and George 2002). While the majority of studies have drawn samples from biotechnology, software and hardware, IT, medical instruments, electronics, high service or high design industries (see Bell 1995; Fernhaber et al. 2008; Gabrielsson et al. 2014; Gassmann and Keupp 2007; Hagen and Zucchella 2014; Hashai and Almor 2004; Zahra et al. 2000), the progression of research in this area has involved a small number of researchers who have shown that BGFs/INVs can also exist in non-knowledge-intensive, low-tech and traditional manufacturing and service industries or sectors. For example, the existence of BGFs/INVs was revealed in metal fabrication, furniture, processed foods and consumer products’ industries (see Madsen and Servais 1997), arts and crafts sectors (see McAuley 1999), food industry (see Hurmerinta et al. 2015; Ismail and Kuivalainen 2015), and the apparel industry (see Dana et al. 2007). Evidence suggests that IE can occur in any industry or sector irrespective of whether it is knowledge or non-knowledge intensive or whether it belongs to high-tech and low-tech industries or sectors.

However, our analysis reveals that there has been increasing focus on SMEs (approx. 34%), followed by firms from various industries/sectors (approx. 32%), and firms involved in food business (4%) beyond 2011 compared to the period 1990–2011, suggesting beneficial impact of past reviews. Surprisingly, our findings in Table 2 indicate that the focus on firms from other sectors, namely agro-based (food), only appeared after 2011. There seems to be a declining interest on high-tech/knowledge-intensive samples during the 6 years following 2011 than in the previous 21 years (1990–2011). This might be due to the fact that several researchers have incorporated high-tech/knowledge-intensive samples using the SME tag in their study. To increase the methodological rigor in IE, past reviews have stressed the significance of incorporating samples from a wide range of industries and sectors, irrespective of firm age and size, and of whether they are knowledge or non-knowledge intensive or belong to high-tech or low-tech industries or sectors (Jones et al. 2011; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Zahra and George 2002). Given the preponderance of high-tech firms and SME sample in our review, it can be argued that empirical knowledge about IE is to a large extent specific to high-tech firms and SMEs. This can be considered to be another barrier to the development of a good theory. According to Keupp and Gassmann (2009, p. 617), IE should not be confined by firm size and age, because the underlying principles of mainstream IB and entrepreneurship theories are not limited by firm size or age. Stepping away from examining primarily successful cases such as smaller new ventures can be a mechanism to advance IE research (Verbeke and Ciravegna 2018). The widely accepted definition of IE, i.e. ‘the discovery, enactment, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities–across national borders–to create future goods and services’ (Oviatt and McDougall 2005, p. 540), is not necessarily specific as to firm size and age (Keupp and Gassmann 2009). Similarly, Jones et al. (2011) also argued that firm size and age variables are not necessarily specific to IE.

Similarly, focusing on high-tech firms limits the generalisability of findings to other industries (Zahra and George 2002), and thus ‘emphasis should be given to the issue for generalising further the results found so far to a wider spectrum of industries’ (Zhou 2007; p. 285), particularly to those low-tech and labour-intensive firms in less-developed countries. Developing countries are typically the major exporters of relatively low-tech and labour-intensive products or services, namely apparel, footwear, toys, handicrafts and consumer electronics (Gereffi and Memodovic 2003). Moreover, the export of agro-based products seems to play a critical role in the economic development of many less-developed countries. Historically, exporting relatively low-tech, labour-intensive and agro-based products or services has been a critical trajectory for economic and industrial development of a number of developing countries (Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, c). Evidence suggests that many low-tech and labour-intensive firms are not necessarily burdened by their technological intensities when entering international markets (see Ahmed and Brennan 2019a, b, c). The owners of these firms may be active in ‘global ecosystems’ (the term used by Reuber et al. (2018)), which might compensate for their firms’ technological shortcomings in their internationalisation endeavour. IE is manifested in ‘global ecosystems which are positioned somewhere between global networks of autonomous opportunity seekers and global factories controlled by brand owners’ (Reuber et al. 2018, p. 401). They recommend that it is important for future IE researchers to examine the mechanism used by different opportunity seekers in global ecosystems in ‘managing the duality of jointly exploiting extant opportunities while exploring new possibilities and avoiding resource dependency’ (p. 401).

Overall, our result indicates that while there has been a tendency towards a narrow focus within IE studies in terms of sample selection, this appears to be changing gradually to encompass a more diverse range of industry/sector contexts, suggesting some beneficial outcomes from past reviews.

Philosophical stance, and data collection and interpretation methods

Researchers typically take a number of philosophical standpoints when it comes to choosing research topics and research design. Since research philosophy has an effect on research topics, research design and methodology (Saunders et al. 2006), the consideration of different research paradigms and matters of ontology and epistemology are therefore of vital importance when undertaking a research (Flowers 2009). Ontology involves explaining the view of a researcher about the nature of reality (i.e. what is the nature of reality?). Objectivism and subjectivism are two distinct ontological positions. Epistemology refers to the theory of knowledge and is related to the question of what should be regarded as acceptable knowledge in a particular field (Bryman and Bell 2007). The epistemological positions determine the application of the available research methods in the study of social reality (Benton and Craib 2001). Positivism and interpretivism are considered two major epistemological positions. Our findings suggest that to date, ontologically and epistemologically, IE researchers have subscribed to either objectivist (epistemologically positivists) or subjectivist (epistemologically interpretivists) ontological positions. The preponderance of objectivist ontology with positivist paradigm is evident in our analysis (in Table 4). There seems to be an increasing focus on objective ontology with positivist paradigm and declining interest in subjective ontology with interpretivist paradigm, followed by pluralistic approaches in IE research during the 6 years following 2011 than in the previous 21 years (1990–2011).

A trivial representation of critical realist/post-positivists or other pluralistic approaches in IE research limits the theoretical rigor in this area. Grégoire et al. (2006, p. 335) argued that a new field must establish ‘a widely shared “paradigm,” i.e., a set of assumptions about a field’s object of study, method of investigation, explanatory model, and overall interpretation scheme’. IE involving the discovery, enactment, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities in international markets (Oviatt and McDougall 2005) is not straight forward, but rather, it is a complex process which evolves over time. Exploring, explaining and gaining in-depth understanding of complex social processes or phenomena require making different philosophical assumptions and interpretations. Surprisingly, apart from Coviello and Jones (2004) and Kiss et al. (2012), no explicit recommendations have been provided in prior review studies related to the significance of different philosophical underpinnings in the development of IE as a research field. According to Coviello and Jones (2004), IE research designs tend to be static and positivist in nature which are therefore unable to capture certain dynamic processes. It is therefore argued that IE researchers may benefit from a ‘more pluralistic approach to methodological application, recognizing that the positivist and interpretivist paradigms can be combined to better capture entrepreneurial behavior and processes over time’ (Coviello and Jones 2004, p. 500; Kiss et al. 2012). Despite their recommendations, our findings suggest that in terms of philosophical underpinnings, IE researchers tend to confine themselves to either objectivists or subjectivists ontologies.

Quantitative and qualitative are two major research approaches frequently employed by social scientists. According to Bazeley (2002, p. 2), these approaches can be distinguished on ‘the basis of the type of data used (textual or numeric; structured or unstructured), the inductive or deductive logic employed, the type of investigation (exploratory or confirmatory), the method of analysis (interpretive or statistical), the approach to explanation (variance theory or process theory), and for some, on the basis of the presumed underlying paradigm (positivist or interpretive)’. While the quantitative approach focuses on confirming or falsifying predefined hypothesis, the qualitative approach deals with providing an answer to ‘why’ and/or ‘how’ type of questions (Yin 2003). Our findings indicate the equal importance of both approaches in IE research undertaken in the context of developed countries. However, IE studies that have drawn samples from emerging and developing countries were dominated by the quantitative research approach. The past reviews have documented the extensive use of the quantitative approach and thus emphasised the adoption of the qualitative approach (Coviello et al. 2015; Coviello and Jones 2004). Keupp and Gassmann (2009) stressed the significance of adopting a theory building research approach (which involves a qualitative approach), rather than theory testing (which is often done using a quantitative approach) to arrive at a body of interdisciplinary understanding of IE. Despite this recommendation, our findings (in Table 4) indicate the growing popularity of quantitative research over qualitative approach during the 6 years following 2011 than in the previous 21 years (1990–2011).

As far as the data collection method is concerned, it is argued that the choice of research strategy/methods is guided by the research question and objectives, the extent of existing knowledge, the amount of time and the other resources that researchers have available and the philosophical underpinnings (Saunders et al. 2003). Yin (2003) identifies experiment, survey, archival analysis, history and case study as five major research strategies that can be employed in a study to collect and analyse data. Our results demonstrate that the case study as a data collection method has been applied in an increasing number of IE studies, followed by the survey as the second dominant research method in studies that draw samples from developed countries. This finding diverges from Coviello et al. (2015). They have shown that the survey method dominates over the case study method. However, the majority of the reviewed studies undertaken in emerging and developing countries employed the survey method, followed by case studies. The application of both research methods in a study is referred to as mono or mixed methods. Our results indicate that although a small number of researchers have utilised mixed methods, a majority of them applied a simple two-step approach, i.e. collection and discussion of secondary data followed by case studies or interviews followed by a survey (Coviello and Jones 2004). To deal with or overcome single method bias, researchers have advocated adopting mixed methods, i.e. combination of both survey and case study methods (Yang et al. 2006). However, IE researchers remain reluctant to use mixed methods in their studies. Secondary data sources, particularly databases in conjunction with primary data sources, can be used to increase the validity and reliability of findings. However, the low use of secondary data sources, namely database, firms’ registers, IPO prospectus, government reports and publications, other secondary data sources evident in our findings, suggests a greater need to increase the use of such readily available data sources to enrich this field of research.

The distribution of IE studies by data collection methods across two periods is presented in Table 4. The case study is almost equally popular across the two periods. Specifically, the deployment of the case study method exceeded the survey in both periods, suggesting the beneficial impact of past review studies. Coviello and Jones (2004) had found that less than a quarter of reviewed studies employed qualitative data collection strategies involving case studies or interviews. However, it should be noted that there has been an increase in the use of survey, and declining focus in other data collection methods during the 6 years following 2011 than in the previous 21 years (1990–2011). The limited use of combined survey and case study methods is also evident from our analysis. This implies that despite recommendations in prior reviews to include both survey and case study, IE researchers seem to limit themselves to one of these methods for the sake of simplicity. The same applies in the case of secondary data sources.

Table 4 also reports the distribution of IE studies by data interpretations across two periods. It is evident from our analysis that both the quantitative and qualitative data interpretation techniques were used almost equally in two periods. Quantitative data interpretation tends to be dominant in IE studies from emerging and developing countries (in Table 7). Mixed methods analysis is considerably less prevalent in both periods and in both developed and emerging/developing country studies. The application of other methods is almost non-existent. Therefore, scholars in this field need to adopt mixed methods for both data collection and interpretation. They also need to adopt more advanced, diverse and sophisticated analytical methods such as content analysis of secondary data sources, meta-analysis, multi-level analysis (Terjesen et al. 2016) and fuzzy set/qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). QCA can compare cases and establish a causal relationship (Roig-Tierno et al. 2017; 1921). QCA’s ability to deal with complex configurations helps it to cope with complex antecedents that social scientists often examine (Roig-Tierno et al. 2017). Our results reveal no application of QCA in IE studies. Given the broader applicability of QCA including explaining entrepreneurial activities, dealing with database and cross-country comparison studies (Roig-Tierno et al. 2016), testing typological and configurational theory (Fiss 2011) and its greater explanatory power (Roig-Tierno et al. 2017), IE scholars thus need to incorporate QCA in their studies, rather than just relying on the hitherto applied methods.

Conclusion

To develop IE as an established and distinct body of knowledge, future scholars should focus on sharing knowledge to wider scholarly communities through publication of their works in mainstream management journals and should target journals outside of the parent disciplines. Moreover, to consider IE as a global phenomenon and a distinct field as claimed in prior studies, it should include more contributions that are focused on neglected countries and/or regions. Focusing on a specific region and a category of industry/sector/firm can contribute to theoretical knowledge in an incremental manner. Although the share of emerging and developing countries in IE studies is marginal, the growing importance of these under-represented countries over the past 6 years is evident. In particular, of the analysed thirty-two studies undertaken in emerging and/or developing countries from 1990 to 2017, half of them belong to the period between 2012 and 2017. Despite this trend, there remain a number of countries and/or regions, and industries or sectors to be explored, irrespective of their economic conditions, and nature of business. Such a pursuit can help IE to develop as a prolific body of knowledge. In addition, more scholarly contributions are required that incorporate research methods and techniques beyond typical practices, i.e. the survey and case study, and qualitative and quantitative interpretations towards the development of a better theory. Exploration of underlying theoretical mechanisms is a difficult task which demands the application of advanced or diverse methods and techniques. Consistent with Coviello and Jones (2004; p. 502), we argue that for IE field to progress, ‘researchers need to make methodological decisions with greater coherency and thoroughness which may involve striving for more rigor and minimising the tendency to adopt simple methodological design’. Overall, although knowledge gaps remain to be explored, some progress has been made to the development of IE as a distinct body of knowledge. This is usual for any field of research. Following Weick’s (1995) suggestion, Jones et al. (2011) argued that since theorising is an incremental and time-consuming process, two decades of research is a very short time for IE to develop as an established body of knowledge.

Like other review studies, this study is not free from limitations. First, our list of reviewed articles is to some extent not inclusive and overlaps with those of prior review studies. This is because we sought to provide a synthesis of accrued knowledge related to methodological trends within the IE field that can benefit future research in making novel contributions. It should however be noted that approximately half of the reviewed empirical papers (57) were published beyond 2011 and therefore, we can argue that our study is distinct to a large extent from the extant literature. Second, our review excludes books, book chapters, reports and conference publications, the inclusion of which might yield additional insights in future research. Third, given resource and time limitations, our review does not report theoretical underpinnings, nor the dependent and independent variables and unit of analysis employed in IE studies. Future research can benefit from a review of these aspects up to the present.

Notes

According to Coviello et al. (2015, p. 17), ‘studies that directly and explicitly integrates theory and concepts from both international business and entrepreneurship fields to examine and explain entrepreneurial behaviour across borders (entrepreneurial internationalization), and/or international comparisons of entrepreneurial behaviour, and/or comparative studies of entrepreneurial internationalization should be considered as IE studies’.

Those authors, who mentioned that they used SME samples, were reluctant to use the phrase high-tech or knowledge-intensive or even low-tech samples in the methodology. However, when explaining the features of their samples, it was evident that many of those falls into our high-tech category.

References

Abdullah NAHN, Zain SNM (2011) The internationalization theory and Malaysian small medium enterprises (SMEs). Int J Trade Econ Finance 2(4):318

Abou-Stait F (2005) Are exports the engine of economic growth? An application of co-integration and causality analysis for Egypt, 1977–2003 (No. 211). Working Paper 76. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/00363566-EN-ERWP-76.PDF. Accessed 28 July 2019

Acedo FJ, Jones MV (2007) Speed of internationalization and entrepreneurial cognition: insights and a comparison between international new ventures, exporters and domestic firms. J World Bus 42(3):236–252

Acs ZJ, Terjesen S (2013) Born local: toward a theory of new venture’s choice of internationalization. Small Bus Econ 41(3):521–535

Ahmed FU, Brennan L (2019a) The impact of Founder’s human capital on firms’ extent of early internationalisation: evidence from a least-developed country. Asia Pac J Manag 36(3):615–659

Ahmed FU, Brennan L (2019b) Performance determinants of early internationalizing firms: the role of international entrepreneurial orientation. J Int Entrep 17(3):389–424

Ahmed FU, Brennan L (2019) An institution-based view of firms’ early internationalization: effectiveness of national export promotion policies. Int Mark Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-03-2018-0108

Åkerman N (2015) International opportunity realization in firm internationalization: non-linear effects of market-specific knowledge and internationalization knowledge. J Int Entrep 13(3):242–259

Al–Aali A, Teece DJ (2014) International entrepreneurship and the theory of the (Long–Lived) international firm: a capabilities perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 38(1):95–116

Andersson S, Danilovic M, Hanjun H (2015) Success factors in Western and Chinese born global companies. iBusiness 7(1):25–38

Andersson S, Evers N (2015) International opportunity recognition in international new ventures—a dynamic managerial capabilities perspective. J Int Entrep 13(3):260–276

Andersson S, Evers N, Griot C (2013) Local and international networks in small firm internationalization: cases from the Rhône-Alpes medical technology regional cluster. Entrep Reg Dev 25(9–10):867–888

Andersson S, Wictor I (2003) Innovative internationalisation in new firms: born globals–the Swedish case. J Int Entrep 1(3):249–275

Arenius P (2005) The psychic distance postulate revised: from market selection to speed of market penetration. J Int Entrep 3(2):115–131

Arenius P, Sasi V, Gabrielsson M (2005) Rapid internationalisation enabled by the Internet: the case of a knowledge intensive company. J Int Entrep 3(4):279–290

Aspelund A, Moen Ø (2001) A generation perspective on small firms’ internationalisation from traditional exporters and flexible specialists to born globals. In: Axinn CN, Matthyssens P (eds) Advances in International Marketing, vol 11. JAI Press, Greenwich

Autio E, George G, Alexy O (2011) International entrepreneurship and capability development—qualitative evidence and future research directions. Entrep Theory Pract 35(1):11–37

Autio E, Sapienza HJ, Almeida JG (2000) Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Acad Manag J 43(5):909–924

Baier-Fuentes H, Merigó JM, Amorós JE, Gaviria-Marín M (2019) International entrepreneurship: a bibliometric overview. Int Entrep Manag J 15:385–429

Bangara A, Freeman S, Schroder W (2012) Legitimacy and accelerated internationalisation: an Indian perspective. J World Bus 47(4):623–634

Baron RA (1998) Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. J Bus Ventur 13:275–294

Baum M, Schwens C, Kabst R (2015) A latent class analysis of small firms’ internationalization patterns. J World Bus 50(4):754–768

Bazeley P (2002) Issues in mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Qualitative Research in Marketing and Management, University of Economics and Business Administration, Vienna

Bell J (1995) The internationalization of small computer software firms: a further challenge to “stage” theories. Eur J Mark 29(8):60–75

Bell J, McNaughton R, Young S, Crick D (2003) Towards an integrative model of small firm internationalisation. J Int Entrep 1(4):339–362

Benton T, Craib I (2001) Philosophy of social science: philosophical issues in social thought (traditions in social theory). Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Blesa A, Monferrer D, Nauwelaerts Y, Ripollés M (2008) The effect of early international commitment on international positional advantages in Spanish and Belgian international new ventures. J Int Entrep 6(4):168–187

Bloodgood JM, Sapienza HJ, Almeida JG (1996) The internationalization of new high-potential US ventures: antecedents and outcomes. Entrep Theory Pract 20(4):61–76

Bonaglia F, Goldstein A, Mathews JA (2007) Accelerated internationalization by emerging markets’ multinationals: the case of the white goods sector. J World Bus 42(4):369–383

Bryman A, Bell E (2007) Business research methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bunz T, Casulli L, Jones MV, Bausch A (2017) The dynamics of experiential learning: microprocesses and adaptation in a professional service INV. Int Bus Rev 26(2):225–238

Burgel O, Murray GC (2000) The international market entry choices of start-up companies in high-technology industries. J Int Mark 8(2):33–62

Busenitz LW, Gomez C, Spencer JW (2000) Country institutional profiles: unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Acad Manag J 43(5):994–1003

Casillas JC, Moreno-Menéndez AM (2014) Speed of the internationalization process: the role of diversity and depth in experiential learning. J Int Bus Stud 45(1):85–101

Cavusgil ST, Knight G (2009) Born global firms: a new international enterprise. Business Expert Press

Cavusgil ST, Knight G (2015) The born global firm: an entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. J Int Bus Stud 46(1):3–16

Chandra Y, Styles C, Wilkinson I (2009) The recognition of first time international entrepreneurial opportunities: evidence from firms in knowledge-based industries. Int Mark Rev 26(1):30–61

Chandra Y, Styles C, Wilkinson IF (2012) An opportunity-based view of rapid internationalization. J Int Mark 20(1):74–102

Chen J, Saarenketo S, Puumalainen K (2016) Internationalization and value orientation of entrepreneurial ventures—a Latin American perspective. J Int Entrep 14(1):32–51

Chetty S, Campbell-Hunt C (2004) A strategic approach to internationalization: a traditional versus a “born-global” approach. J Int Mark 12(1):57–81

Chetty S, Johanson M, Martín OM (2014) Speed of internationalization: conceptualization, measurement and validation. J World Bus 49(4):633–650

Choquette E, Rask M, Sala D, Schröder P (2017) Born globals—is there fire behind the smoke? Int Bus Rev 26(3):448–460

Coeurderoy R, Murray G (2008) Regulatory environments and the location decisions of start-ups: evidence from the first international market entries of new technology-based firms. J Int Bus Stud 39(4):670–687

Coviello NE, Jones MV (2004) Methodological issues in international entrepreneurship research. J Bus Ventur 19(4):485–508

Coviello NE, Jones MV, McDougall-Covin PP (2015) Is international entrepreneurship research a viable spin-off from its parent disciplines. Rethinking entrepreneurship: debating research orientations, pp 78–100

Coviello NE, Munro HJ (1995) Growing the entrepreneurial firm: networking for international market development. Eur J Mark 29(7):49–61

Coviello N, Munro H (1997) Network relationships and the internationalisation process of small software firms. Int Bus Rev 6(4):361–386

Covin JG, Miller D (2014) International entrepreneurial orientation: conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrep Theory Pract 38(1):11–44

Crick D, Spence M (2005) The internationalisation of ‘high performing’ UK high-tech SMEs: a study of planned and unplanned strategies. Int Bus Rev 14(2):167–185

Cumming D, Sapienza HJ, Siegel DS, Wright M (2009) International entrepreneurship: managerial and policy implications. Strateg Entrep J 3(4):283–296

Czinkota MR (1994) A national export assistance policy for new and growing businesses. J Int Mark 2(1):91–101