Abstract

The starting question before us here is: how should we approach complex international entrepreneurship decisions and problems? This article aims to trace the evolutionary scholarly road that has brought us here and highlight some of the significant signals, road signs, milestones, and barriers along the way. We will pause at each milestone to view the scenery surrounding it and also examine the underlying structures there, especially those that have served as foundations for the evolutionary course that usually starts at a local origin, passing through milestones, for reaching global destinations; as well as examining the nature of the evolution that has brought us to the current state of affairs. In light of multidisciplinary nature of international entrepreneurship (IE), drawing and relying on a few disciplines, there is a need to abstract from some in favor of deeper discussion of others with more prominent impact and presence in IE. We aspire to portray the outline of a multilayered conceptual framework to serve two primary purposes: to suggest a promising path for further theoretical developments and to provide a roadway to allow us to travel through to farther theoretical and operational destinations; and to highlight the articles appearing in this issue. We will view each article as a milestone and examine how the selective features of the article confirm, if not support, the framework enabling us to push forward to see farther horizons. Structurally, this article starts with a brief introduction that travels through three theoretical and foundational stops on the way to develop a broader view of IE at the end. A proposed conceptual framework will project, and enable us to see, that broader view. The latter part of the article travels through the four articles to highlight their theoretical developments and empirical findings that lend support to pertinent aspect of the proposed framework. A brief discussion at the end explore selected implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

McDougall and Oviatt (2000, 2003) initially defined international entrepreneurship at the intersection of International Business (IB) and entrepreneurship. Even then, both the IB and entrepreneurship were somewhat complex already. Although the extent of their inherent complexities has continually increased over time, they were not yet deeply explored. The main aims of this article are to highlight the extent of IB’s and entrepreneurship’ complexities, examine their intersection, and possibly broaden it; although the initial intersection has already expanded and enriched with newer developments, including global value-creating networks, the internationalization of firms from emerging markets, the quickening pace of international competition, the appearance of the “platform operations,” and the billion dollar start-ups, popularly called “Unicorns,” among others, all portraying their own features and imposing corresponding complexities on other competing entities.

A brief perspective on IB

Generally, IB referred to the conduct of business across country borders in disparate market environments, ranging from socio-culturally proximate to highly distant from the home environment across many dimensions, necessitating careful attention to each market condition. The annals of international marketing have documented many international market failures by otherwise successful large firms that failed to understand local markets and did not respond properly at the time. This may have motivated Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 1990) to adopt a cautious approach to internationalization and propose psychic and geographic distance as factors in international market selection and also in the extent of involvement in the market under consideration through the firm’s initial market entry strategy in order to give the firm (or its agents) the opportunity to learn experientially over time and increase its commitment to the market when warranted. Even in insolated indirect exporting—through local import agents and distributors facing low levels of risk and involvements—the inherent difficulties of dealing with foreign local agents could be challenging. Furthermore, distant cross-cultural communications could also add to the relational complexity. As far back as the turn of the millennia, this may have led Johanson and Vahlne (2003, 2009) to emphasize “outsidership” as a barrier to international operations and to suggest that becoming a member of local value-creation network (e.g., local distribution and marketing network) would be a way to ease the difficulties of entering local foreign markets. Sullivan-Mort and Weerawardena (2006) go further to suggest that “primary and secondary networking capabilities” facilitate, if not necessary, to successful local operation of smaller entrepreneurial firms in foreign markets. In addition to the inherent difficulties of managing cross-cultural relations with members of different and diverse local networks to remedy “outsidership,” their operational procedures may not necessarily conform with those of firm’s, as they are external to the firm. Larger firms, such as multinational enterprises (MNEs), have developed their own internal network of sister subsidiaries and have established structural and associated operational rigidities of their own, to ensure optimal performance for the institution as a whole, which may not be open to outsiders. In spite of their capable management and rich resources, differences in the home and multiple host country requirements, resulting in corresponding operational differences, may not allow for rapid adaptation and adjustments to each and every market or external institution, or conducive to easing existing complexities. Additionally, the natural evolutions of the entire institution (i.e., the headquarters and sister-subsidiary network) over time may even increase the initial environmental gaps between the home and potential hosts, which could also add to the extent of complexities, requiring timely adaptation in order to operate coherently. The comparable situation facing smaller, resource-constrained and time-compressed younger firms could be much worse. These observations led Etemad (2004) to propose IE as a dynamic open complex adaptive system (DOCAS for short), in which all participating agents would continually adapt to change and new conditions, regardless of the source, to avoid costly irreconcilable conflicts and even reduce inherent complexities.

McDougall and Oviatt (2000: 903) pointed to still other complexity arising from application and viewing problems (and decisions) from different research approaches or perspectives (e.g., anthropology, economics, psychology, sociology, among others, or their combinations), which may differ from those of managers; as they evolve at different rates over time and gain experience and learn from different local operations (or from local agents operating on behalf of international companies) on how to conduct their business more effectively. We now turn to the entrepreneurial side of IE.

A brief perspective on entrepreneurship

In contrast to the main focus of IB on larger, relatively well-established, and generally resource-rich firms with structured organizations and a network of sister-subsidiaries, the main agents of IE have been smaller and resource-constrained firms for the most parts. However, most smaller firms are more entrepreneurial, and at times the entrepreneur-founder remains at the helm for sometimes; although these conditions also change as these firms grow further internationally and introduce structural rigidities with more procedural guidelines in order to help controlling their expanding international operations. At the core of these firms, however, are the entrepreneur-founder-managers, or a small top management team (Covin and Slevin 1988), that operate as an entrepreneurial entity. For simplicity, we abstract from this relational and operational complexities of team’s dynamics and continue as if the individual entrepreneur makes the critical decisions; thus allowing us to rely on the construct of entrepreneurial orientation. The entrepreneurial orientation of these firms has been examined extensively. We follow Covin and Slevin (1991) conceptualizing firm’s entrepreneurial behavior and Dess and Lumpkin’s (2005: 147) later characterization of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) in terms of a five-component construct (i.e., Innovativeness, Pro-activeness, Risk-taking, Autonomy and Competitive Aggressiveness) that also includes Miller’s (1983) correlates of entrepreneurship in three different type of firms. Although the construct excludes Mintzberg (1973) original suggestion and its further expansion by Miller and Friesen (1978), Lumpkin and Dess (1996) expanded on EO by linking it to performance, which provides a sufficiently comprehensive framework for our further discussion.

Entrepreneurial orientation in international Contexte

Etemad (2015a, b) suggested that the EO-Performance construct (or simply EO-P, hereafter) needs to account for the multi-market operations and the overtime evolution of such operations in internationalizing entrepreneurial firms to be more reflective of IE in general, and to the internationally oriented start-ups as well as knowledge-intensive smaller firms in particular, before they become (or can be considered as) Born Globals, INVs, rapidly internationalizing enterprises—RIEs (Keen and Etemad 2012), High Growth Firms—HGFs (Keen and Etemad 2011), among others. A brief examination of EO-P relations in internationalizing small firms confirms the impact of time and experience on all of the EO components that consequently affect performance. Logically, for example, an internationalizing smaller firm initially faces the liabilities of a higher perceived operating risks due to the perception of its “foreignness” (Hymer 1976; Johanson and Vahlne 2009), “newness” (Stinchcombe 1965), insufficient international “experiential knowledge” and “outsidership” (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2003, respectively) in its early entries than the later ones, when elapsed time enables the firm to learn and accumulate higher levels of experiential knowledge and resources overtime, and have, for example, higher affordable losses (Sarasvathy 2001, 2004) allowing for tolerating higher risks or acting more aggressively or more proactively that earlier. Although similar arguments can be easily made for the remaining components of EO-P, we abstract from doing so in favor of time and space in order to introduce and incorporate the network component into the above discussion.

The contribution of networks to entrepreneurial internationalization

Aside from the numerous strategic advantages of network operations, a combination of two evolutionary phenomena—intense global competition for achieving higher values, and distributed specialization leading to higher competiveness—have given a rise to the need for integrating the fragmented components of the supply chain’s upper-stream activities through synergistic, and even symbiotic, network agreements (Etemad et al. 2001; Dana et al. 2000). Although the down-stream activities, especially distribution, are usually distributed geographically, the system of local distribution has been traditionally viewed as an intra-firm network of marketing and distribution network, whose interests are highly allied with those of the firm. The challenge here is, therefore, to make the two networks at both the upper and lower streams as effective and as synergistic as possible. Through such synergistic network agreements, a firm can concentrate on developing its own competitive advantage and yet construct an optimized value-creating integrated network by taking advantage of the competitiveness of each highly specialized operation owned and operated by independent firms; and possibly distributed in different geographic locations across the globe. Optimization, however, imposes certain constrains, if not rigidities, on the participating network members, including reciprocity of operating norms, trust through personal relations, and alignment of related transaction and connecting logistics, among others, that are well discusses elsewhere (e.g., see Alvarez and Barney 2001; Gulati 1995; Larson 1992, among a host of others). Even when one can abstract from the rigidifying impact of other influential components besides those of IB, entrepreneurship and networks, the important emerging point is that EO-P, placed in the appropriate international context, will have its own behavioral characteristics capable of potentially adding to the complexities inherent to IB, entrepreneurship and networks, as briefly discussed above.

The state of smaller entrepreneurial firm in the composite IB, EO-P, and networked conditioned

Naturally, smaller firms, deprived of rich resources, find international operations more challenging than their larger counterparts in managing the transition from home to host and adapting well to each different local market condition for delivering the maximum possible value to their customers. The concept of customer value has also evolved overtime. Customer satisfaction, one at the time, arising from perceived value, has become highly crucial, and possibly central, to attaining success and differs from its past counterpart when there were limited supplies and customers had a very few choices. Regardless of their time and location, global customers now have access to: (i) readily available information about competitive global suppliers providing similar products and values, (ii) platform operators that do customize (i.e., tailor-make for each customer) to deliver high perceived values to each customer, and consequently, (iii) world-wide customers are demanding the highest possible values from potential suppliers thus making global competition much more intense even at the individual levels. Just being objectively better than other competing firms across a market does not guarantee success any longer. The overall success is only achieved when the delivered value is being perceived as higher by each customer, one at the time, and at their own time, location, and convenience. The time that a market as a whole, or an entire market segment, was the unit of analysis, and profits were a measure of success, appear far in the distant past. Seemingly, it is only a matter of time that each and all customers’ requirements are met, and their corresponding values are maximized as a prerequisite for firm’s survival and growth.

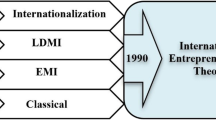

Towards a conceptual and integrated framework

In addition to the above brief discussion of entrepreneurship, IB, and Networks in relation to IE, the influence of other disciplines are also well-documented. Although, the scope of this article does not permit for their discussion, no matter how brief the coverage, a multi-layered integrated framework should be able to allow for proper consideration of such influences and to account for their possible impact. Accordingly, the following schematic figure depicts international entrepreneurship (IE) at the common intersection of five layers, each representing a selected influential discipline, with the flexibility of easily incorporating others. The noteworthy point is that a comprehensive framework should be able to incorporate, and also account for, all influential factors, forces, and perspectives; and the concept of common intersections is designed to allow for the interactive impact of such influencesFootnote 1(See Fig. 1).

Brief highlight of the articles appearing in this issue

The second article in this issue is entitled as “Enacted identities in the university spin-off process—bridging an imaginative gap” and is authored by Martin Hannibal. This paper examines the transitional and evolutionary path that university-based scholars experience in becoming an entrepreneur when embarking on the course of establishing a start-up firm to offer an innovative, and possibly knowledge-intensive, product or service to a target market. In addition to all of the entrepreneurial challenges involved in starting a new firm, university-based scholars experience a personal and career challenge, for which they were not trained; and as a result, they face added uncertainties. The true nature of academic scholarship is, in a sense, entrepreneurial as the discovery of new innovations or creation of new knowledge involves continuous uncertainties of researching a topic full of unknowns with important implications for the scholars involved. Although such uncertainties may adversely impact one’s career path, or the pace of one’s promotion, it does not threaten the scholar’s livelihood. Most research problems are eventually solved after sometimes using different methodologies and engaging others with different perspectives to collectively solve the problem. Leaving academia to embark on nascent entrepreneurship exposes university-based scholars not only to the risk of losing a relatively safe career path; but it also challenges their capabilities, identity, and even livelihood, for which they are ill-prepared. Ideally, a richer entrepreneurial network and support system replaces their previous fully functional arrangements, but there is no guarantee, especially in starting-up a small firm with little to no resources, small to no proven market, a small and tentative network and insufficient, if not inadequate, capabilities to solve start-up’s operational problems; in addition to the inherent difficulties of commercializing an innovation resulting from university research and development laboratories. Although mainly entrepreneurial but mainly technical at the core, the nature of the problems facing a start-up lies at the cross sections of strategy (e.g., acquiring resources and capabilities and gaining competitive advantage), networks (e.g., networks of buyers, suppliers, resource providers, and their corresponding human, financial and social capital as well as knowledge and technical resources), operations management (e.g., staffing, scheduling, and production management), and international business if forced to outsource from, or to sell to, international markets. Logically, approaching the problem from only one perspective will result in a sub-optimal strategy with an unsatisfactory solution. The paper’s findings indicate that academics-turned-entrepreneurs straddled initially on the boundaries or at the intersection of influential factors in both the old career and the new path and strategize at the overlapping aspects of networks, entrepreneurship, and operations management by leveraging their intellectual property and university-based (or scholarly) social capital to enable the creation and management of their start-ups (i.e., the causation concept), by keeping their academic identity, and its corresponding intellectual and social capital, on which to fall back in case of adversity requiring increased tolerance for risk (i.e., “Affordable loss” in the parlance of effectuation theory of entrepreneurship). This paper followed the “behavioral logics” of eight inventor-founders embedded in university spin-off ventures, thus giving rise to the importance of the initial context (eco-system), in which the entrepreneur was embedded (i.e., the university environment), in relation to the new context that entrepreneur was entering (i.e., the start-up and entrepreneurial eco-system). Furthermore, the paper highlights the fact that entrepreneurial start-ups balance between the individual entrepreneur’s aspirations and planned behavior (i.e., drawing on the theory planned behavior, discussed in the fifth paper in this issue) as well as an initial knowledge of general entrepreneurship, but not necessarily those involved in starting-up and growing a new enterprise. In short, this article lends support to the concept of operating in overlapping operating contexts, each of which are parts of different systems and are influenced by different forces and operating procedures and requirements.

The third article in this issue follows the path of the second article and provides further empirical support for the proposed framework. It is entitled as the “Paths of evolution for the Chinese migrant entrepreneurship: a multiple case analysis in Italy” and is co-authored by Simone Guercini, Matilde Milanesi, and Gabi Dei Ottati. These authors’ research was motivated by their general observation that Chinese immigrating to Italy had formed a rich and successful business community and adjusted to entrepreneurial life in Italy with relative ease. These entrepreneurs have not only leverage the advantages of their ethnic community and the Chinese business networks, but also draw upon the resources and capabilities embedded in both the home and host environments by capitalizing on their ethnic social capital in Italy and in China as well as relying on the strong and large business network of the Chinese diaspora and Chinese enterprises worldwide. Moreover, this and the next article in this issue document the international movement of entrepreneurs to conduct business outside of their home market thus confirming that there are at least two broad internationalization strategies—i.e., the international movement of entrepreneurs to operate in local foreign markets and internationalization of enterprises. The former possibility suggests that any conceptual framework, including the proposed one in this article, should further expand to allow for the sociological aspects of migration and international movements of entrepreneurs, which have not been an integral part of the main stream IE or IB in the past.

The fourth article in this issue shares some of the features of the previous two articles. It examines the operations of Latino ethnic entrepreneurs that have established and operate enterprises in southern regions of the state of Texas in the USA, where there is a strong presence of Latino and American-Mexican population and businesses. It is entitled as “Small business enterprises and Latino entrepreneurship: An enclave or mainstream activity in South Texas?”, coauthored by Michael J. Pisani, Joseph M. Guzman, Chad Richardson, Carlos Sepulveda, and Lyonel Laulié. The underlying research surveyed a sample of 298 Latino small business enterprises in Southern Texas. The authors suggest that Sothern Texas is “a minority-majority region,” and the Latino businesses and start-ups are located close to the US-Mexico borders to conduct formal and informal businesses. The geographic proximity has resulted in the prevalence of a mixture of US and Mexican cultures, including the advantage of using English and Spanish, which helps in easing the transitional process from embeddedness in one into the other. The authors introduce and examine the concept of entrepreneurial activities in “an enclave” located within the mainstream environment and present a typology of entrepreneurial start-ups in such an environment.

The fifth and final article in the issue is entitled as “Entrepreneurial intentions—theory and evidence from Asia, America, and Europe” and is coauthored by Justin Paul, Philippe Hermel, and Archana Srivatava. This paper draws on the theory of planned behavior to examine the cross-cultural antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions in four strategically important countries in different regions of the world—India, Japan, France, and the USA to suggest that the country culture and proactive personality directly determine the degree of entrepreneurial intention. In a cross-cultural sample of young managers, the authors compare entrepreneurial intentions within the context of the four country cultures and postulate a theoretical framework to link entrepreneurial intention and its drivers. In short, this article finds that culture—an integral part of countries’ operating environment—influences entrepreneurial intentions in young managers.

Collectively, the above four articles not only confirm and lend support to the basic concept and structure of the proposed framework, but they also point to the need for incorporating the impact of additional potentially influential factors that may have direct or indirect effects on internationalization of entrepreneurship or entrepreneurial internationalization, regardless of time and location, as the four articles conducted research in diverse environments, diffrent aspects and at different time periods.

A brief discussion and implications

The theoretical discussion guiding the structural architecture of the proposed framework pointed to a degree of complexity arising from the impact of a number of influential factors and forces affecting IE, each of which have their own regulatory regimes, operating procedures, and behavioral rigidities. It is within such levels of complexity and rigidities, originating from differ sources, that international entrepreneurship operates; and therefore, any framework needs the flexibility of incorporating, and also accounting for, the various factors and forces capable of exerting influence on IE processes, even indirectly. Accordingly, the proposed framework offers the desired flexibility and the search for cross-section of the potential influential factors should be able to identify, and provide for, their joint and at times conflictive influences.

The proposed framework is suggesting the concept of common intersection to portray the necessary conditions for successful IE operations in particular and the corresponding decisions in general. The common intersection is likely to exclude the possibility of violating inflexible constraints and hard boundary conditions, the measurement, the nature of which require judicious and research-based decisions. In contrast, when and if a relatively narrow and simple—as opposed to comprehensive and inclusive, within the logical reasons—is considered, the influence of what is not conceptualized, and thus left out, will be missing and may become a potential cause for difficulty. Given the prevailing level of complexity, a sample of which was briefly discussed earlier on, such oversights are unnecessary and should be avoided. The time is ripe for IE scholars to expand the span of their theoretical horizons and to become as inclusive as possible. Although such efforts may take longer time, impose difficulty, and not yield immediate result, the Journal of International Entrepreneurship invites all efforts in that vein.

The implications of this article fall in two categories—complexity of entrepreneurial internationalization and conducive public policy to stimulate international entrepreneurship activities. Regarding the former, while the initial strategic planning and the design of business models should consider potential incremental influences (in spite of their added complexities, as discussed earlier) in order to provide clarity on the required degree of entrepreneurial orientation in terms of pro-activeness, innovativeness, competitive aggressiveness, and risks mitigation, in order to ensure optimal performance, their corresponding operational plans and models need not be as involved or as detailed. Their simplification may require additional time and efforts, but is likely to ensure success in delivering acceptable optimal value to each and every buyer, supplier, and stake holder.

For the latter, public policy should not only recognize the added benefit accruing to both the home and host countries and reward international entrepreneurs for enacting them, but also introduce incentive to reduce the costs of the incremental complexities in order to encourage, and even stimulate, entrepreneurial firms’ internationalization for their potentials in delivering benefits to all stake-holders, regardless of their origins and destinations.

Again, the journal calls on the IE scholarly community and public policy designers to conduct research in these areas for contributing to and easing the delivery of optimal, if not maximal, value to all concerned.

Notes

The term “common intersection” should be viewed as the joint cross-section of pertinent influences.

References

Alvarez SA, Barney JB (2001) How entrepreneurial firms can benefit from alliances with large partners. Acad Manag Exec 15:139–148

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1988) The influence of organization structure on the utility of entrepreneurial top management style. J Manag Stud 25:217–234

Covin, JG, and Slevin, DP (1991). A Conceptual model of entrepreneutshipas firm behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1): 7–24

Dana LP, Etemad H, Wright R (2000) The Global Reach of Symbiotic Networks. J Euromarketing 9(2):1–16

Dess GG, Lumpkin GT (2005) The role of entrepreneurial orientation in stimulating corporate entrepreneurship. Acad Manag Exec V19(1):147–156

Etemad H (2015a) Entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship in the international context. J Int Entrep 13(1):1–6

Etemad H (2015b) The promise of a potential theoretical framework in international entrepreneurship: an entrepreneurial orientation-performance relation in internationalized context. J Int Entrep 13(2):89–95

Etemad H (2004) International entrepreneurship as a dynamic adaptive system: towards a grounded theory. J Int Entrep 2(1 & 2):5–59

Etemad H, Wright R, Dana LP (2001) Symbiotic Business Networks: Collaboration Between Small and Large firm. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev 43(4):481–500

Gulati R (1995) Social structure and alliance formation patterns: a longitudinal analysis. Adm Sci Q 40:619–652

Hymer SH (1976) The international operations of National Firms. MIT Press, Cambridge

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (1977) The internationalization process of the firm: a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. J Int Bus Stud 4:20–29

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (1990) The mechanism of internationalization. Int Mark Rev 7:11–24

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (2003) Business relationship learning and commitment in the internationalization process. J Int Entrep 1:83–101

Johanson J, Vahlne JE (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J Int Bus Stud 40:1411–1431

Keen CH, Etemad H (2012) Rapid-Growth and Rapid Internationalization of Smaller Enterprises from Canada. Manag Decis 50(4):569–590

Keen CH, Etemad H (2011) Rapidly-growing firms and their main characteristics: a longitudinal study from United States. Int J Entrep Ventur 3(4):344–358

Larson A (1992) Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: a study of the governance of exchange relationships. Adm Sci Q 37:76–104

McDougall PP, Oviatt BM (2003) Some fundamental issues in international entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship theory and practice, pp 1 to 27 (down loaded from Google scholars in June 2017)

McDougall PP, Oviatt BM (2000) International entrepreneurship: the intersection of two research paths. Acad Manag J 43:902–908

Miller D (1983) The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science 29:770–791

Miller D, Friesen P (1978) Archetypes of strategy formulation. Manag Sci 24:921–933

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (1996) Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad Manag Rev 21(1):135–172

Mintzberg H (1973) Strategy making in three modes. Calif Manag Rev 16(2):44–53

Sarasvathy SD (2001) Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency the. Acad Manag Rev 26:243–263

Sarasvathy SD (2004) Making it happen: beyond theories of the firm to theories of firm design. Enterp Theory Pract 28:519–532

Stinchcombe AL (1965) Social structure and organizations. In: March JG (ed) Handbook of organizations. Rand McNally, Chicago, pp 142–193

Sullivan-Mort G, Weerawardena J (2006) Networking capability and international entrepreneurship: how networks function in Australian born globals. Int Mark Rev 23(5):549–572

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Etemad, H. Towards a conceptual multilayered framework of international entrepreneurship. J Int Entrep 15, 229–238 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-017-0212-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-017-0212-5