Abstract

The traditional family, today, is outclassed by the spread of dual-career families (Gahlawat et al., 2019), hence the need to seek a balance in the management of work and family and to pay attention to what can affect individual well-being. Through attention to the quality of contexts, it is possible to study those constructs considered fundamental for psychological functionality as motivation and basic psychological needs. This study, therefore, analyzes a model that validates the mediating role of needs between work and family motivation and work and family satisfaction, in 208 dual-career parenting couples. Analyzes have shown that needs mediate the effect of motivations on satisfaction outcomes. Motivation, encouraging needs satisfaction, contributes to results of greater satisfaction in the domains of interest. These results, in line with the most recent SDT contributions (Ryan & Deci, 2017), confirm the mediation role of needs as a guarantee of greater well-being results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the twenty-first century, the imagery of the “traditional” family, with the husband as breadwinner and the wife as housewife, has increasingly weakened (Aziz et al., 2018). The increase in female participation in employment has led to the collapse of the existing rigid boundaries between work and family roles (Cooklin et al., 2015). These changes characterizing the last 50 years of history have helped to narrow the gap based on popular stereotypes and reflect changing gender roles in performing certain tasks and filling certain positions (Young et al., 2014). Parents are thus participating in work at an increasing rate (OECD, 2011), children are being brought up in contexts where both parents are employed and ‘dual- income families’ are becoming the norm in industrialized countries (Michel et al., 2011). Growing number of workers are part of ‘dual-career’ couples of parents, more women, in fact, make up the workforce, just as the proportion of working fathers becoming more involved in parenting is increasing (Gahlawat et al., 2019).

Having abolished the ‘myth of separate worlds’ whereby work life was separate from family life, it is now reasonably assumed that the relationship between work and family is dynamic and reciprocal; not only do factors in the work sphere influence family life, but also family issues have strong effects on work-life (Michel et al., 2011). Thus, the work-family pair becomes the subject of attention in the literature, but while many studies initially focused only on the experiences of mothers in this circumstance, it was later realized that issues relating to this binomial also affected working fathers and thus the parental couple system as a whole (Gahlawat et al., 2019). The achievement of a balance between work and family, the reduction of harmful interference between the two contexts and a greater inter-role balance is in fact a goal of both working parents (Kelliher et al., 2019). Unsurprisingly, many parents may find it difficult to manage both contexts and this may have an impact on their own well-being (Cooklin et al., 2015). Some authors believe that in the past, especially in work and family-related studies, positive outcomes, such as life satisfaction have not been addressed with due care, to the detriment of major studies in which the focus was mainly on interruptive conflict and stress generated by the coexistence of multiple responsibilities (Kossek et al., 2011). In light of this, it is instead of fundamental importance to explore satisfaction at work and in the family as crucial indicators of subjective well-being in both these two contexts. Some studies, that have focused on these two aspects, have in fact highlighted the spillover between satisfaction in these two realities of attention, confirming that the crossover effects of satisfaction in one domain on that of the other cannot be ignored (Gahlawat et al., 2019). The authors confirm the presence of evidence that satisfaction in work roles leads to better perceptions of family roles and therefore better satisfaction in this context as well (Gahlawat et al., 2019). The increase in dual-career families thus draws attention to the importance of achieving a functional inter-role balance, as both partners need to cope with the increasing demands of the working world and the needs of the family (Gahlawat et al., 2019).

The literature on the work-family binomial has produced some studies in which it is therefore found that family motivation, by encouraging the sense of self-efficacy, increases work motivation which in turn is also fueled by family needs and requests (Umrani et al., 2020). In both the two domain (family and work), indeed, a consolidate line of studies have examined the role of motivational processes using the self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017) as a theoretical framework. The Self Determination Theory is a macro-theory of human motivation that pays attention to both the quantity and the quality of motivation and postulates that people show distinct forms of motivation that can be placed in a continuum that goes from a more intrinsic motivation to the external (Ryan & Deci, 2017). People may feel motivated to take an action because they appreciate the action itself (intrinsic motivation) or act because they fully accept and approve the importance of an activity (identified regulation), or because the person has internalized the reasons for engaging in behaviour (integrated regulation), to arrive at a type of behaviour implemented to avoid a sense of guilt or shame (introjected regulation) up to the least autonomous form of motivational regulation or external coercion, or the behaviour implemented because driven by external factors such as obtaining praise or expectation of reward (extrinsic motivation). Although there is a lack of studies that explore simultaneously the motivational process in both work and family contexts using SDT as theoretical framework, in each specific domain several studies pointed out that when the experience in a specific context is driven by more autonomous motivation, this can lead to higher positive outcomes in that context (Kanat-Maymon, et al., 2016; Ryan & Deci, 2017). In the context of parenting, some studies have focused on motivation for parenthood (Brenning et al., 2015) showing that a more autonomous motivation seems to correlate with more positive outcomes such as self-efficacy, relational functioning and personal well-being. Similarly, more autonomous motivations at work provide positive work performance, greater satisfaction in employment and a greater stress reduction (Autin et al., 2022; Deci et al., 2017).

According to SDT, a relevant role in the association between autonomous motivation and well-being is due to the basic psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Chen et al., 2013; Ryan & Deci, 2010; 2017). The need for autonomy, refers to a perceived sense of control over one’s actions, the need of competence, describes a feeling of being capable of completing tasks and activity, and relatedness, is about the sense to be emotionally connected to other people (Gillison et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2017). The satisfaction of these needs recognized as “psychological nutrients” thus allows for a greater state of well-being (Chen et al., 2013). Several studies have in fact highlighted the mediating role of the satisfaction of needs in the association between autonomous motivational regulation and well-being outcomes (Baard et al., 2004; Brenning et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2013; Olafsen et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2010). Consequently, as well as more autonomous motivations, through the mediation of the satisfaction of needs, determine positive outcomes in several domain and contexts, in the same way is plausible to find the same paths of association also examining simultaneously the experience in both work and family domain.

Furthermore, when both the experience in the work and family domains are tested, generally most of the studies (Greenhaus et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2019) have focused only on one component of the couple. However, today, with the increasing number of dual-career families, there is a greater need to stimulate research within both members of the parental couple; couples find themselves having to manage work as well as family and household responsibilities (Zhao et al., 2019). For this reason there is a strong need to turn the focus not only on the well-being in the individual experiencing, but extending to the couple with an examination on the dynamics that are triggered within the members of the family unit. In these realities, the commitment to the growth and care of the offspring directs towards a new redefinition of individual needs, in addition to family needs; the involvement of both partners, in both domains of life, produces new challenges that lead to a new redefinition of both personal and family management and balances (Hall, 2018).

Within the family context, both partners can influence each other, determining repercussions on their own psycho-physical well-being, but also on the partner (Lebow et al., 2012), which makes a dyadic approach to the study of the constructs that can interact and influence the functioning of couples of fundamental importance. To allow for a greater and more complete understanding of the dynamics of the parental couple, it is necessary to pay attention to the close interdependence between the partners, hence the need to underline not only the individual elements, but also the interpersonal ones; therefore, the Actor Partner Interdependence (APIM) model turns out to be the most suitable analysis strategy. The APIM models take into account the interdependence of the partners, thus analyzing at the same time not only the “actor” effects (associations between different variables of the same person), but also the “partner” effects, which represent the associations between the variables of one person and the variables of the other (Conradi et al., 2017). Indeed, through the use of APIM models, all possible associations between the variables under examination are detected, thus controlling the effect of the reciprocal associations.

The Present Study

In accordance with previous studies that have showed the positive correlation between autonomous motivations and positive outcomes in several domain (Moran, 2012) and in agreement with previous finding that suggest the importance need satisfaction (Autin et al., 2022), the present study aims to investigate a model that, consistently with the SDT, confirms the mediating role of need satisfaction in the association between autonomous motivational in both work and family domain and work and parental satisfaction in both the partners of dual career parents using an APIM approach. Specifically, starting from preliminary analyses, the aim of this study is to test a full APIM model that highlights (a) the association of work motivation and family motivation with needs satisfaction; (b) the association of needs satisfaction with work and parental satisfaction; (c) possible indirect associations between motivations and satisfactions via needs satisfaction (d) possible direct associations between family motivation and parental satisfaction; (e) possible direct associations between work motivation and work satisfaction; (f) possible crossover association between partners; (g) cross effects between the constructs inherent the two different domains (work motivation with parental satisfaction and family motivation with work satisfaction).

Method

Participants

The participants in the research are 208 parental couples from the Italian territory, more specifically, the participants, for the most part, reside in the Sicily region. In the selection process, two were the discriminating variables for participation, specifically the need for both spouses to be workers and to have at least one child aged between 10 and 15 years. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample and highlights that for the male partner, the age is included in a range from 31 to 63 years (M = 49.12, SD = 6.81), while for the female partner, the age is included between 30 and 57 years (M = 45.95, SD = 6.43). The data set was mostly homogeneous with regard to the participants’ educational qualifications and professional categories. Specifically, with regard to educational qualifications, 19% of male spouses had a middle school degree, 55% a high-school degree, 21% a graduation, 4% a postgraduate degree and 1% indicated ‘other’; female spouses, on the other hand, had 12% a middle school degree, 50% the high school degree, 30% a graduation and 7% a postgraduate degree. Concerning the professional category, both men (73%) and women (77%) indicated a higher percentage of being ‘employee’, while only 25% of men and 21% of women indicated that they were ‘freelance’. Finally, the data revealed that the majority of families had two children (63%), followed by those who had only one child (21%), those who had three children (14%) and finally a small percentage of families with four children (2%).

Procedure

The research was accepted by the ethics committee and complies with the APA criteria. A convenience sample was enrolled on a voluntary basis in the territory of Sicily, and therefore did not receive any form of compensation for participation. Inclusion criteria were: cohabitation of parents, parents both workers, age of children between 10 and 15 years. Groups of graduated students recruited the adult participants through their social groups, direct acquaintances, and contacted also several local organizations. In some cases, these participants distributed the survey among their friends, creating a snowball approach. This type of sampling helped reach a more diverse sample of participants. Therefore, given the nature of the convenience sample, it is not known how many participants were contacted but declined to participate. Before completing the questionnaires, the participants read and signed the informed consent which was stored separately from the protocol to ensure their privacy. Participants were allowed to fill in the questionnaire using a paper–pencil approach or with an online version through the diffusion of a telematics link. Subsequently, the responses received were collected in an online dataset and matched thanks to a anonymous code that safeguarded their privacy.

Measures

Family Motivation

The instrument used to assess motivation to have a family is an adaptation of the instrument on motivation to have a child (AMHCS) proposed by Brenning et al. (2015), reformulating each item with reference not to the motivation to have a child, but to the motivation to have a family. The instrument, which maintains the presence of 20 items on a Likert scale from 1 “do not agree at all” to 5 “agree very strongly”, is thus composed of items that assess the intrinsic motivation “For the satisfying feeling of good moments with my family”, the identified regulation “Having my family is one of the valuable ways to realise my goals”, the introjection “I can only feel proud of myself when I will build my family”, the external regulation “Because everyone is expected that a new family to be built” and finally the amotivation “I don’t think any reasons to having a new family”. Through two confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), models for male and females participants were analyzed using the Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator and, for this adaptation of the instrument, the results obtained indicated good fit indexes, male: χ2(160) = 299.068, ScF = 1.05, p = 0.00, R-CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.08, R-RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.08 (0.07, 0.09); female: χ2(160) = 229.488, ScF = 0.97 p = 0.00, R-CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.08, R-RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.07 (0.06, 0.08). In agreement with previous studies, also in this research contribution the results indicated that the 5 subscales have satisfactory internal consistency values, respectively for males and females equal to: α = 0.93 and α = 0.91 for intrinsic motivation, α = 0.90 and α = 0.89 for identified regulation, α = 0.88 and α = 0.87 for introjection, α = 0.93 and α = 0.92 for external regulation and finally α = 0.84 and α = 0.81 for amotivation. In this research contribution, a total score created by the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) was calculated from the original subscales present to evaluate the motivation to have a family; it is a single score derived from the subscales that provide an index of the general degree of autonomy perceived by the respondents from the SDT point of view; it is in fact considered an index of the motivational quality of the individuals, which, confirming the correlational model between the subscales, emphasises the presence of autonomous motivations rather than controlled motivations (Brenning et al., 2015). Imagining motivational adjustments along a continuum, the following calculation was therefore used: (2 × Intrinsic Motivation) + (1 × Identified Adjustment) + (− 1 × Introjected Adjustment) + (− 2 × External Adjustment); from this it is possible to deduce that for the AMHCS instrument, the “Amotivation” scale was not considered as it is not a relevant index for the motivational intensity of individuals, which is instead the object of analysis.

Work Motivation

The work motivation (WM) instrument was proposed by Moran et al. (2012) based on the theoretical assumptions of Self-Determination Theory regarding motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The instrument proposes an initial question “Why are you motivated to do your work? “ followed by 15 items, three for each type of regulation identified; specifically, it is possible to find items on the external regulation “Because my boss wants me to do it”; introjected regulation “Because I would feel ashamed if I did poorly”; identified regulation “Because I believe my work is valuable”; integrated regulation “Because my work helps to define me” and intrinsic regulation “Because I find the work interesting”. In accordance with previous studies, also in this research contribution the results indicated that the 5 subscales present the following reliability indices, respectively for males and females: α = 0.62 and α = 0.68 for external regulation; α = 0.77 for introjected regulation; α = 0.85 and α = 0.90 for identified regulation; α = 0.85 and α = 0.87 for integrated regulation and finally α = 0.85 and α = 0.86 for intrinsic motivation. In this research contribution a total score created by the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI), was calculated from the original subscales present to evaluate the work motivation; it is a single score derived from the subscales that provides an index of the general degree of autonomy perceived by the respondents from the SDT point of view; it is in fact considered an index of the motivational quality of the individuals, which, confirming the correlational model between the subscales, emphasises the presence of autonomous motivations rather than controlled motivations (Brenning et al., 2015). Imagining motivational adjustments along a continuum, the following calculation was therefore used: (2 × Intrinsic Motivation) + (1 × Identified Adjustment) + (− 1 × Introjected Adjustment) + (− 2 × External Adjustment); from this it is possible to deduce that for the WM instrument the scale of “Integrated regulation” was left out in order to make the calculation of the motivational level more equivalent in both domains of interest and to align it with the choice of previous studies based on SDT (Chemolli & Gagné, 2014).

Need Satisfaction

The Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; Chen, et al., 2015; Costa et al., 2018) is the instrument used to assess basic psychological need frustration and satisfaction, which consists of 24 items, which assess, on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 “Not true at all” to 5 “Completely true”, the twofold facet of satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs, and specifically: autonomy “I feel my choices express who I really am”, “I feel forced to do many things I wouldn’t choose to do”; relatedness “I feel that the people I care about also care about me”, “I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to”; competence “I feel capable at what I do”, “I feel like a failure because of the mistakes I make”. In the present research contribution, an overall score of satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs was evaluated, calculating as a reverse the items of frustration of the same (Hope et al., 2019). The reliability coefficient was adequate both in males (α = 0.86) and in females (α = 0.87).

Parental Satisfaction

The Kansas Parental Satisfaction (KPS, James et al., 1985) is the instrument used to assess parental satisfaction. There are three items and they investigate parental satisfaction with their child’s behavior, their perception of themselves as parents and their relationship with their child. These items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 “Completely dissatisfied” to 7 “Completely satisfied”. Some examples of items: “How satisfied are you with your children’s behavior?”, “How satisfied are you with yourself as a parent?”. The choice of this instrument for the present study lies in the important psychometric properties found; the analyses showed excellent reliability indices in both males (α = 0.82) and females (α = 0.77).

Work Satisfaction

Job Satisfaction Scales (JS, Di Fabio, 2018; Heller & Watson, 2005) was used to assess work satisfaction. The instrument through its five items evaluates, on a Likert scale from 1 “Completely disagree” to 7 “Completely agree”, the degree of agreement of the participants regarding propositions inherent to the pleasure, enthusiasm and satisfaction in carrying out the professional task (E.g. “In this period, I feel enthusiastic about my job”). In this study, the level of reliability was satisfactory in both males (α = 0.84) and females (α = 0.83).

Data Analysis

The data were structured as dyadic data in excel dataset, the data were organized in a pairwise structure so that each line represented a dyad containing the mothers’ and fathers’ scores. The Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Statistics 19) was used to conducted descriptive statistics (Mean, Standard Deviations, Skewness and Kurtosis), Pearson correlations and t-test for paired data, were used to compare scores obtained by parents in all scales of each questionnaire. Using the “lavaan” package of R with the implementation of R studio (version 4.1.0), the hypothesized model with latent variables was tested using SEM with the robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) estimation and following the indication for actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) approach. Specifically need satisfaction, work satisfaction and parental satisfaction consisting of three parcels each. The family motivation was operationalized through the creation of four RAI parcels according to the following RAI procedure = (2 * Intrinsic Item) + Identified Item + (− 1 * Introjected Item) + (− 2 * Extrinsic Item) (Evans & Bonneville-Roussy, 2016). The same procedure was used to create three RAI parcel of work motivation. The adoption of an actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) is based on the use the dyad as a unit of analysis. Specifcally, the APIM was defined with the incorporation of male and female variables in the same model: (a) estimating the associations of male and female work/family motivations (predictors), need satisfaction (mediator), and work/family satisfactions (outcomes) beetween the same member (actor effects); (b) estimating the associations of male and female work/family motivations (predictors), need satisfaction (mediator), and work/family satisfactions (outcomes) of a member with the variables of the other member of the couple (partner effects); (c) correlating each other the work/family motivations of the male and female partners; (d) correlating each other the need satisfaction of the male and female partners; (e) correlating each other the work/family satisfactions of the male and female partners. Finally, using the bootstrap procedure (MacKinnon et al., 2004), have been examined the regressions and indirect associations between variables.

Preliminary Analysis

Examination of the missing values have shown that 27 values were missing on a total of 24,960 total values in the dataset (120 items * 208 couples of participants) and represent less than 5% of the total values. The Little’s MCAR test for missing have shown to be significant, χ2(1956) = 2095.36, p = 0.02, suggesting that the data were not to be missing completely at random. The total scores of the variables used in this study were created averaging single items in an aggregate score and when some items were missing the score was created with the mean of the other available items. Using this approach only one variable of a single subject remains with a missing. Considering that when less than 5% of data are missing the choice of the methods for handling them make little difference (Raymond & Roberts, 1987) the listwise approach was used for the correlation analyses and the FIML method was implemented in path analysis. Descriptive statistics and correlations analyses for the study’s variables for both male and female partner were reported in Table 2. Family motivation, work motivation, needs satisfaction and work satisfaction, in both partners, had levels of skewness and kurtosis within the range of ± 1, suggesting a normal distribution, while the parental satisfaction have shown higher level of skewness and kurtosis (male: Ske = − 1.08, Kurt = 1.00; female: Ske = − 1.36, Kurt = 3.09) suggesting a minor violation that was handled with the bootstrapping approach in the path analysis. The collinearity of the data was verified with the magnitude of the correlation coefficients that in this case were modest with a range between − 0.04 and 0.56. Through the parametric test for paired data t- test a subsequent moment of analysis was carried out which made it possible to highlight any average differences in the levels of the variables studied for fathers and mothers. Specifically, within partners only in the work motivation there was a statistically difference, with women that reported higher level of autonomous motivation than male partner [t (206) = − 3.04 p < 0.01].

In Table 2, in addition to the mean and standard deviation, it is possible to highlight the correlations between the variables in both partners. Table 2 shows not only the correlations in reference to the variables of the male partners and those of the female partners separately, but also pays attention to the possible cross-over effects. Regarding this last aspect, it is possible to deduce that the family motivation for male correlates positively and in a statistically significant way only with the family motivation for female and with needs satisfaction for female. The work motivation for male correlates positively and statistically significantly with all female variables except for the work motivation for female. The needs satisfaction for male correlates positively and significantly with all the variables observed in the female partner. The parental satisfaction for male correlates positively and significantly with the need satisfaction, parental satisfaction and work satisfaction for female; but always the parental satisfaction for male correlates in a non significant way with family motivation for female and with the work motivation for female. Finally, the work satisfaction for male correlates positively and statistically significantly with all the variables of the female partner except for the family motivation for female.

Hypothesized Model

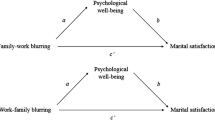

Before testing the full model, presented in Fig. 1, analyzes were conducted on a preliminar latent model that included only male and female motivational predictors (family motivation and work motivation) and outcomes (family satisfaction and work satisfaction). This first model presented good fit indices χ2(271) = 529.272, S-Bχ2 (271) = 486.588 p = 0.00, R-CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.06, R-RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.06 (0.05, 0.07). Specifically, positive associations were found between male work motivation and both parental and work satisfaction of male. Finally, further positive associations were also highlighted between the work motivation of females and their parental and work satisfaction. The other paths were not significant.

Consequently, the proposed full APIM model with latent variables was tested (Fig. 1), showing good fit indices, χ2 (419) = 716.130, S-Bχ2 (419) = 659.473 p = 0.00, R-CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05, R-RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.05, 0.06) and allowing the examination of associations between all the study variables. Specifically, from the model represented in Table 3 it is possible to observe that the family motivation for male and the work motivation for male, have a positive association with need satisfaction for male. In turn, need satisfaction for male has positive associations with parental satisfaction for male and work satisfaction for male. A similar paths of association is visible with the female variables; also in this case the family motivation for female and work motivation for female, present a positive association with need satisfaction for female, that in turn has positive associations with parental satisfaction for female and work satisfaction for female. From Table 3 it is also possible to observe that work motivation for male has a direct association on work satisfaction for male and the same thing happens for the female variables, with work motivation for female that has a direct association with the work satisfaction for female. Finally, it is also possible to find some cross-partner associations with the family motivation for female that has a positive association with the parental satisfaction for male, moreover, while the need satisfaction for male presents an association with the work satisfaction for female, the need satisfaction for female instead presents an association with the parental satisfaction for male.

The indirect associations among the observed variables are visible in Table 4 and suggest that through needs satisfaction for male, significant indirect associations are visible between: family motivation and parental satisfaction for male; family motivation and work satisfaction for male; work motivation and parental satisfaction for male; and work motivation and work satisfaction for male. There is also a significant indirect effect across partners between family motivation for female and work satisfaction for male. Through needs satisfaction for female stand out significant indirect associations between family motivation and parental satisfaction for female, between family motivation and work satisfaction for female, between work motivation and family satisfaction for female, and between work motivation and work satisfaction for female. There are also significant indirect associations across partners via needs satisfaction for female, in particular between work motivation for female and parental satisfaction for male.

Finally, the model described above was then tested controlling for background variables, demonstrating good fit indices χ2(573) = 896.30, S-Bχ2(573) = 849.541 p = 0.00, R-CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05, R-RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.04, 0.06). Specifically, the background variables used for males and females were age, educational qualification, professional category (dichotomic: employee vs freelance) and number of children. Examination of associations have shown that all the paths of the full hypothesized model tested remain significant after the control of the background variables. Results have shown also some significant associations between the study variables and the background ones. Specifically, between the family motivation of females and their educational qualification, between the work motivation of females and their professional category. Furthermore, a significant role was also found for the satisfaction of male needs by their professional category; significanti associations between work and parental satisfaction of males and educational qualifications of females, finally a significanti role for the work satisfaction of females by the professional category of males.

Discussion

The study carried out has the goal of paying attention to work and family motivation, need satisfaction, work and family satisfaction within parental couples with an experience of dual career families. The primary objective of this study was to validate an APIM mediation model that reveals the role of the satisfaction of basic psychological needs between motivation and satisfaction in dual-career parenting couples. The analyzes conducted for the survey regarding the proposed mediation model involved the entire parental couple, therefore both fathers and mothers; for these reasons, the suitable methodology was found to be the Actor Partner Interdependence Model. The actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) has been highly successful, has been used extensively in the study of romantic couples, and has become the default method for analyzes of dyadic data where both members of the couple have the same measures (Kenny, 2018). Overall, results of this study have shown that in accordance with the SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017), autonomous motivations support well-being through the satisfaction of basic psychological needs in both partners and with some association also between partners.

The present study, examining actor associations, has therefore highlighted that, in both the partners, both work autonomous motivation and family autonomous motivation have a positive association with the satisfaction of basic needs. This is in line with previous studies in other contexts, such as sport in which Adie et al. (2008) found that more autonomous orientations in athletes defined greater satisfaction of needs, which in turn led to more positive outcomes; as well as later in the study conducted by Ryan et al. (2010) they talked about the ‘weekend effect’, which showed that more self-determined choices and perceived as truly autonomous and dictated by the volition promote better health outcomes through a more effective satisfaction of needs, while the sense of ‘duty’, frustrating these, would lead to a greater perception of discomfort.

On the basis of this, the results obtained are relevant and show significant associations not only between motivations and needs but also between needs and satisfactions in the specific domain (work and family). Specifically, the study conducted showed significant associations between need satisfaction and parental satisfaction as well as between needs satisfaction and job satisfaction, both in men and women. Reasonably, these results obtained, consistently with the literature, confirm the important attention to be paid to the role of basic psychological needs satisfaction in companies in order to obtain greater satisfaction and results at work (Olafsen et al., 2018). Furthermore, the satisfaction of autonomy, competence and relatedness, is associated with an increase in well-being, which also seems to correlate with better work performance (Van den Broeck et al., 2016).

As previously reported, significant associations are also found between need satisfaction and parental satisfaction in male and female partners. The result obtained is in line with previous studies which have confirmed that the needs satisfaction contributes to a better perception of parental satisfaction and therefore consequently to a better adaptation to parenthood (Ross-Plourde & Basque, 2019). Specifically, the study of Ross-Plourde and Basque (2019) focused on the motivation to have a child, while the present study extends them to a type of motivation relating to the care and support of an already formed family. Despite this, in accordance with the study conducted by Ross-Plourde and Basque (2019), this contribution also shows relevant results regarding the association between needs and parental satisfaction, underlining the importance of needs satisfaction for an optimal parenting experience for both working parents.

The above helps us to understand how needs, presenting significant associations both with motivational factors and with satisfaction outcomes, can reasonably be identified as mediating factors. The present research contribution, starting from these last considerations, indeed wanted to follow an even newer line of investigation, already carried out by other studies (Brenning et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2013), in which once again it was possible to confirm the role of mediation of needs satisfaction between motivation and satisfaction in the two work and family domains examined. Acting voluntarily and guided by a more autonomous regulation, acts in a way that satisfies the three basic psychological needs (Olafsen et al., 2018). The satisfaction of needs is thus a key mechanism which, as demonstrated and confirmed with the model performed with the path analysis, explains the function of motivation towards well-being outcomes. In support of this statement it is possible to highlight the presence of some significant indirect effects. Specifically, it is relevant to underline how family motivation for males is associated with family satisfaction for males through the male needs satisfaction. This data supports the importance of the mediating action of needs. Indeed, when parents have a more self-determined motivation to become parents, they feel more fulfilled in their parenting role only in the condition in which their needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness are satisfied (Ross-Plourde & Basque, 2019).

The examination of the preliminar model with only predictors and outcomes (without psychological needs), highlighted the initial presence of positive associations between work motivation and satisfaction, not only at work but also with the family. This initially underlined the importance of the interaction between the targeted domains, emphasizing how motivation in one sector can be associated with the outcome of the second context. This highlights the close interconnection existing in society between family and work (Erum et al., 2020) and once again confirms how feeling motivated in a context, the consequent perception of competence and well-being experienced in interconnected realities significantly influence the outcomes in the systems in close interaction. Results tested through this preliminar model cleary show strong actor effects from work motivations in both partners, but highlight also the absence of direct associations between family motivations and satisfactions in both partners that is also visible in the full model (with the basic needs). This result finds a reasonable explanation as it has just been demonstrated by the presence of the indirect role of the needs satisfaction. This absence of a direct and significant association between family motivation and parental satisfaction could be probably due by the conflictual experience that working parents could have between their motivations to have a family and the actual experiences in the context of parenthood. This could be in line with previous findings that have shown that working mothers often experience feeling of guilty towards their family, even more so towards their children, because they believe do not have the cultural ideal of the “good mother” (Collins, 2021). Similarly, some working parents with an autonomous motivation to have a family could desire to spend more time with their children but they could not have this opportunity for working reason and this could reduce the parental satisfaction because they their actual experience in parenting is not in line with their expectation. However, parental satisfaction could occur when autonomous motivational factors promote the satisfaction of psychological needs, parents with autonomous motivations could have more resources to balance their activities and cope with problematic situations promoting parental autonomy, competence and relatedness that in turn could facilitate the parental satisfaction.

The tested full model showed also a significant association between work motivation and job satisfaction in both partners. In males, it seems reasonable to think that this figure follows what is commonly called “gender ideology”, which has always seen man spend more energy and resources in world of work and women in the family domain, and this is easily justifiable as it conforms to the expectations on roles imposed by society, today (Li et al., 2020) as in the past (Eagly, 1987). The same direct association in females adds an extra element, extending the presence of this result to further reflections. Mothers can certainly pay attention to the family sphere, but they are also able to calibrate the importance of the working sphere; this confirms that women are able to achieve relatively functional results in the family as well as in work, contrary to what is often handed down in popular belief (Senécal et al., 2001).

The attention paid to gender is in this regard a constant of the proposed study, one of the objectives was in fact to highlight cross association between partners and thus detect, in line with the APIM models, partner and therefore interpersonal results. From the tested model there are cross associations between partners, in particular, a direct association between parental motivation for female and parental satisfaction for male, as well as female needs satisfaction and parental satisfaction for males. Also in this case, a fundamental role seems to be played by the satisfaction of needs. In fact, previous studies have shown that the satisfaction of needs has positive associations also in romantic relationships, it seems in fact to be associated with healthy relationships, higher levels of self-esteem, relationship satisfaction and more adaptive responses in conflict (Ross-Plourde & Basque, 2019). Feeling autonomous, competent and connected can lead to more adaptive couple behaviors, greater happiness and support which is important for achieving positive outcomes between partners (Ross-Plourde & Basque, 2019).

The relationships between partners have been the subject of studies, and it has often been of fundamental importance, as a key to understanding the results, to understand the relevance acquired by the interweaving of the circumstances of one partner with those of the other partner (Slotter & Gardner, 2009). The attention paid in this case to the intersection of constructs such as the motivations of a partner on the satisfactions of the other partner, or even the insertion of basic psychological needs help to understand how it is useful to pay attention as a whole to the dynamics that characterize the families and how it is necessary to study not only the single individuals, but also the social dynamics around them. Quality adult relationships turn out to be those relationships in which people feel strong-willed and autonomous, but also feel the other as autonomously determined (Ryan et al., 2021). The interweaving in the associations found between the autonomous motivation of one partner and the final satisfaction of the other partner, demonstrates what has just been mentioned, confirming how the self-determination of the individual affects the well-being of the other partner, configuring itself as a result of great interest for the well-being of the couple, and in this case the functionality of the entire family unit. The motivational construct in relationships also indicates the direction and energy of the behavior of each member of the couple and appears to be a fundamental construct for the study of dyadic happiness (Blais et al., 1990). Hence the importance of taking into consideration the associations between partners and the particular reference to the links between motivation and satisfaction outcomes and, no less, to the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Indeed, quality relationships are characterized by a sense of mutual voluntariness, mutual support and support for autonomy and relatedness; these dynamics are sometimes considered, by some theories, as contrasting and in opposition, but profoundly coincident for the SDT, which, addressing autonomy as a concept of voluntariness and freedom of choice thus seems to clearly connect to the satisfaction of a functional relatedness and connection with the other (Ryan et al., 2021). Furthermore, all the associations described in the full model remain significance also after controlling for the effect of the background variables, and confirm the large applicability of the principles proposed by the SDT, which seem relevan also in relation to the different contexts or different circumstances that can characterize the various families (Nalipay et al., 2020).

Since the preliminary analyzes it has also been possible to focus on the results obtained and reflect on gender. In fact, already from the sample correlations, there are no statistically significant results between the family motivation for male and the perception of satisfaction in the family context itself or in the working context; the same family motivation for male does not find statistically significant correlations even with work motivation, unlike for woman. This result seems to be in contrast with what is present in the literature, according to which family motivation would encourage work motivation (Umrani et al., 2020). These first data obtained thus allow us to reflect on the salience that certain domains may have for people, while for some both the work and family roles are equally important, others, instead, do not consider either one or the other role relevant or even they may consider one role more salient than another (Erdogan et al., 2021).

In addition to the study of cross effects on gender, a further reflection may arise from the results obtained on the study of cross effects on the domains of interest. In particular, cross associations between contexts are found between male family motivation and male job satisfaction through the male needs satisfaction, between female family motivation and job satisfaction for females, as well as between female job motivation and female family satisfaction, both of the latter two associations through the mediating action of the needs satisfaction for females. There are also cross associations not only with regard to contexts but also with regard to gender, in particular between female work motivation and male family satisfaction through the female needs satisfaction. As highlighted, however, this cross-association between the constructs inherent in the two different domains does not manifest itself as a direct effect but always for the mediation action of the needs satisfaction, which is confirmed once again of fundamental importance in the explanation of the motivating factors action on satisfaction results. However, the attention to be paid to the relationship that mutually influences the domains of interest remains of fundamental importance.

Studies on the spillover theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013) have in fact always underlined the mutual influence between the two contexts of interest. Consequently, some studies carried out on dual-career pairs of parents have confirmed this (Schnettler et al., 2022). Underlining the huge presence of studies on work motivation and consequent job satisfaction, Schnettler et al. (2022) underlined the attention to be paid instead to the mutual influence of the two contexts, emphasizing how the family climate can affect job satisfaction. Furthermore, while in this cited study no cross effects were found with regard to gender; in our obtained results, a double cross effect between gender and contexts is detectable, which highlights not only the reciprocal influence between the domains but also the possible influence between partners of each other’s wellbeing, as addressed through previous findings.

Furthermore, the proposed model highlights associations between female family motivation and work motivation for females, a relationship that is not evident in males. This emerged data, in addition to further supporting the thesis regarding the different perception of the salience of the two roles, also opens up a new reflection on the possible incidence and positive influence of the work domain in the family domain, in those people as in our case of mothers, who live both roles in a position of almost equal salience. In this regard, in fact, it can be taken into consideration that work motivation, producing functional results, generates a greater sense of self-efficacy that is also carried into other domains, as in our case in the family sphere, encouraging the motivation itself and positive behavioral outcomes (Erum et al., 2020). Some studies, in fact, have pointed out that motivation can act as a main factor for satisfaction outcomes, proposing therefore what was called the two-factor theory, in which it was assumed the existence of a two-factor structure of motivation and satisfaction, through which the second element was reached only in the presence of adequate motivating factors (Sanjeev & Surya, 2016).

Nonetheless, this research has several limitations to take in account. The use of only self-report questionnaires can lead to some measurement bias, due for example to social desirability. In future research, the use of additional measurement methodologies such as observational designs or interviews, which can compare different types of measurement and check for possible bias, is encouraged. The use of a cross-sectional correlational studies does not allow to establish neither the direction nor the causality of the effects. In fact the data were collected at one time point and not across multiple time points. Several other variables were not studied such as work and family conflict or even relevant elements such as support between colleagues or couple satisfaction. Some research has shown that individuals, who show high levels of self-determined motivation towards family activities, were more satisfied with their family life and experienced fewer work-family conflicts, thus leading to positive consequences in various life contexts (Senécal et al., 2001). It may also be of significant importance, to pay attention to what may be the implications for parenting methods such as psychological control or parental support; through the use of daily surveys, some studies have revealed, the relationship between parental needs satisfaction and more functional parenting strategies (Mabbe et al., 2018). The use of at least cohabiting or married households does not allow a total generalization of the data, it could be useful for this to address also to separated or divorced families; just as having involved parental couples from southern Italy alone could cause a cultural limitation, it could therefore be useful to direct future research to the rest of the national territory or to other cultural contexts. Furthermore, a possible limitation of the present research could be attributable to the lack of control of several differences between the participants regarding background characterises, social contexts, and the realities in which everyday life develops. For example couples from urban and rural areas could potentially differ in the study variables and these could affect the level of motivation and the importance of satisfying some needs rather than others. We suggest a possible control in this sense in future research.

However, the results obtained would then make it possible to improve the knowledge and awareness of what can lead to more positive outcomes, so as to facilitate possible interventions on those that are configured as strengths in the promotion of health and well-being, in a reality, that of ‘dual career’ families, which is now increasingly widespread. These findings also extend research on the important role of basic psychological needs, providing further support for previous SDT studies in which needs satisfaction mediated the relationship between motivational factors and well-being outcomes. Furthermore, since the basic psychological needs satisfaction plays an important role in the link between motivation and psychological adaptation, psychological needs could act as a key mechanism that could also be addressed in the design of some intervention programs. However, it is considered necessary to encourage research on these aspects and encourage attention to the influence of these contexts of primary importance today, in particular using a broader approach such as the biopsychosocial perspective and also involving the institutional sphere. It may be useful to direct further research also to the inclusion of all those elements that can influence the outcomes in the family and work context, such as the support of other family members or the perception of the children’s experience. Finally, considering that some variables can change their perception of intensity as the development period varies, it might be useful to consider the possibility of carrying out subsequent studies within several groups of families that experience different periods of children development.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in fact, if in the past the investigated domains saw a clear separation of roles, today the participation of both members of a couple in one context and in the other grows considerably. It is therefore important to highlight how the reality of dual carrier families is increasingly growing, in which, just as the involvement of women in the world of work increases, so does the involvement of men in family responsibilities; this therefore requires a more equitable redistribution of responsibilities among the partners and a greater attention to the sources of support of the well-being of the same (Li et al., 2020). Through the data reported it is in fact possible to state that highly effective people do not achieve well-being if they do not follow goals that satisfy basic psychological needs; cultural values and social contexts, proximal or distal, in fact influence both the type of motivation and the satisfaction of these basic needs, and from this follows better psychological health (Deci & Ryan, 2012).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abd Aziz, N. N., Yazid, Z. N. A., Tarmuji, N. H., Samsudin, M. A., & Abd Majid, A. (2018). The influence of work-family conflict and family-work conflict on well-being: The mediating role of coping strategies. Strategies, 8(4), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i4/4012

Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motivation and Emotion, 32, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9095-z

Autin, K. L., Herdt, M. E., Garcia, R. G., & Ezema, G. N. (2022). Basic psychological need satisfaction, autonomous motivation, and meaningful work: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Career Assessment, 30(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727211018647

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and weil-being in two work settings 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover—crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–70). Psychology Press.

Blais, M. R., Sabourin, S., Boucher, C., & Vallerand, R. J. (1990). Toward a motivational model of couple happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1021–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1021

Brenning, K., Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2015). What’s your motivation to be pregnant? Relations between motives for parenthood and women’s prenatal functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(5), 755. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000110

Chemolli, E., & Gagné, M. (2014). Evidence against the continuum structure underlying motivation measures derived from self-determination theory. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 575. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036212

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(7), 1184–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113480038

Collins, C. (2021). Is maternal guilt a cross-national experience? Qualitative Sociology, 44(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-020-09451-2

Conradi, H. J., Noordhof, A., Dingemanse, P., Barelds, D. P., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2017). Actor and partner effects of attachment on relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction across the genders: An APIM approach. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(4), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12222

Cooklin, A. R., Westrupp, E., Strazdins, L., Giallo, R., Martin, A., & Nicholson, J. M. (2015). Mothers’ work–family conflict and enrichment: Associations with parenting quality and couple relationship. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12137

Costa, S., Ingoglia, S., Inguglia, C., Liga, F., Lo Coco, A., & Larcan, R. (2018). Psychometric evaluation of the basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale (BPNSFS) in Italy. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 51(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1347021

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 85–107). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0006

Di Fabio, A. (2018). Job Satisfaction Scale Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana. G Ital Ric Appl. https://doi.org/10.14605/CS1121807

Eagly, A. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation. Erlbaum.

Erdogan, I., Ozcelik, H., & Bagger, J. (2021). Roles and work–family conflict: How role salience and gender come into play. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(8), 1778–1800. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1588346

Erum, H., Abid, G., Contreras, F., & Islam, T. (2020). Role of family motivation, workplace civility and self-efficacy in developing affective commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 358–374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010027

Evans, P., & Bonneville-Roussy, A. (2016). Self-determined motivation for practice in university music students. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735615610926

Gahlawat, N., Phogat, R. S., & Kundu, S. C. (2019). Evidence for life satisfaction among dual-career couples: The interplay of job, career, and family satisfaction in relation to workplace support. Journal of Family Issues, 40(18), 2893–2921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19868267

Gillison, F. B., Rouse, P., Standage, M., Sebire, S. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychology Review, 13(1), 110–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1534071

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work-family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8

Hall, M. E. (2018). Dual-career couple counselling: An elaboration of life-design paradigm. Australian Journal of Career Development, 27(2),) 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416218777882

Heller, D., & Watson, D. (2005). The dynamic spillover of satisfaction between work and marriage: The role of time and mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1273

Hope, N. H., Holding, A. C., Verner-Filion, J., Sheldon, K. M., & Koestner, R. (2019). The path from intrinsic aspirations to subjective well-being is mediated by changes in basic psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: A large prospective test. Motivation and Emotion, 43, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9733-z

James, D. E., Schumm, W. R., Kennedy, C. E., Grigsby, C. C., Shectman, K. L., & Nichols, C. W. (1985). Characteristics of the Kansas Parental Satisfaction Scale among two samples of married parents. Psychological Reports, 57(1), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1985.57.1.163

Kanat-Maymon, Y., Antebi, A., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2016). Basic psychological need fulfillment in human–pet relationships and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.025

Kelliher, C., Richardson, J., & Boiarintseva, G. (2019). All of work? All of life? Reconceptualising work-life balance for the 21st century. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12215

Kenny, D. A. (2018). Reflections on the actor–partner interdependence model. Personal Relationships, 25(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12240

Kossek, E. E., Baltes, B. B., & Matthews, R. A. (2011). How work–family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(3), 352–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2011.01353.x

Lebow, J. L., Chambers, A. L., Christensen, A., & Johnson, S. M. (2012). Research on the treatment of couple distress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(1), 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00249.x

Li, X., Cao, H., Curran, M. A., Fang, X., & Zhou, N. (2020). Traditional gender ideology, work family conflict, and marital quality among Chinese dual-earner couples: A moderated mediation model. Sex Roles, 83, 622–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01125-1

Mabbe, E., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., van der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Mouratidis, A. (2018). Day-to-day variation in autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting: The role of parents’ daily experiences of need satisfaction and need frustration. Parenting, 18(2), 86–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2018.1444131

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.695

Moran, C. M., Diefendorff, J. M., Kim, T. Y., & Liu, Z. Q. (2012). A profile approach to self-determination theory motivations at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.09.002

Nalipay, M. J. N., King, R. B., & Cai, Y. (2020). Autonomy is equally important across East and West: Testing the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory. Journal of Adolescence, 78, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.009

OECD. (2011). Doing better for families. OECD Publishing.

Olafsen, A. H., Deci, E. L., & Halvari, H. (2018). Basic psychological needs and work motivation: A longitudinal test of directionality. Motivation and Emotion, 42, 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9646-2

Raymond, M. R., & Roberts, D. M. (1987). A comparison of methods for treating incomplete data in selection research. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 47(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164487471002

Ross-Plourde, M., & Basque, D. (2019). Motivation to become a parent and parental satisfaction: The mediating effect of psychological needs satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 40(10), 1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19836458

Ryan, R. M., Bernstein, J. H., & Brown, K. W. (2010). Weekends, work, and well-being: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.95

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2010). A self-determination theory perspective on social, institutional, cultural, and economic supports for autonomy and their importance for well-being. In V. I. Chirkov, R. M. Ryan, & K. M. Sheldon (Eds.), Human autonomy in cross-cultural context: Perspectives on the psychology of agency, freedom, and well-being (pp. 45–64). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9667-8_3

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2021). Building a science of motivated persons: Self-determination theory’s empirical approach to human experience and the regulation of behavior. Motivation Science, 7(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000194

Sanjeev, M. A., & Surya, A. V. (2016). Two factor theory of motivation and satisfaction: An empirical verification. Annals of Data Science, 3(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40745-016-0077-9

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Orellana, L., Poblete, H., Lobos, G., Lapo, M., & Adasme-Berríos, C. (2022). Family-to-work enrichment associations between family meal atmosphere and job satisfaction in dual-earner parents. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02580-z

Senécal, C., Vallerand, R. J., & Guay, F. (2001). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Toward a motivational model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201272004

Slotter, E. B., & Gardner, W. L. (2009). Where do you end and I begin? Evidence for anticipatory, motivated self–other integration between relationship partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1137–1151. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013882

Umrani, W. A., Siyal, I. A., Ahmed, U., Ali Arain, G., Sayed, H., & Umrani, S. (2020). Does family come first? Family motivation-individual’s OCB assessment via self-efficacy. Personnel Review, 49(6), 1287–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2019-0031

Van den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C. H., & Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1195–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316632058

Young, M., Schieman, S., & Milkie, M. A. (2014). Spouse’s work-to-family conflict, family stressors, and mental health among dual-earner mothers and fathers. Society and Mental Health, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869313504931

Zhao, K., Zhang, M., & Foley, S. (2019). Testing two mechanisms linking work-to-family conflict to individual consequences: Do gender and gender role orientation make a difference? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(6), 988–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1282534

Funding

No financial support was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EDS assisted with generation of the initial draft of the manuscript, data analyses, study design and concept and manuscript editing, FC assisted with manuscript editing, data analysis, study design and concept, SC assisted with data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript editing, FL assisted with data interpretation, manuscript editing, and study supervision. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

The authors complied with the American Psychological Association’s ethical standards in the treatment of participants for this work. This research has been approved by the local institutional research ethics committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

De Salvo, E., Cuzzocrea, F., Costa, S. et al. Parents Between Family and Work: The Role of Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J Fam Econ Iss 45, 672–686 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-023-09910-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-023-09910-2