Abstract

The last decade of research on college student financial wellness was driven by the onset of the “student loan debt crisis.” Prior to the focus on student loans, credit card use and marketing was the primary area of interest for those studying young adult finances on campuses. This paper consolidates the findings reported in twenty papers related to college student finances that were published in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues between 2010 and 2019. The work is organized into individual financial behaviors and its antecedents, followed by a summary of studies that study well-being indicators. The reviewed studies address financial behaviors as products of individual and personal characteristics, family relationships and formal socialization processes, and how these factors influence general well-being outcome. Though the approaches vary widely across published studies, each addressed at least one outcome within the socialization model. Credit card and student loan financial behaviors are common factors in determining well-being, their resulting impact on financial or general subjective well-being are mixed at best. The area of research is relatively new and directions for future research are outlined. Studies of emerging adults over time, replication of previous work, consistency in approach to measuring key constructs, and commitment to theoretically based approaches to research will all help to clarify our understanding of college students’ transition to financial independence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholarship on the boundary between families and economic issues mushroomed three decades ago when the journal shifted focus to this area and changed its title to the Journal of Family and Economic Issues (JFEI) (Dew 2008; Hennon 1988). A review of studies published between 1988 and 2007 in JFEI identified fifteen research themes including poverty, consumer attitudes, family policies, and work-family issues (Dew 2008). College financial implications, the theme for this decade review, was previously unrecognized. JFEI research themes emerge as individuals and families meet new or unprecedented financial difficulties and economic challenges, such as the Global Financial Crisis that spurred the Great Recession or the economic shock of the current pandemic.

The growth in scholarship of the college financial implications theme can be attributed to the more precarious financial condition in which today’s young adults are situated compared to earlier generations (Dwyer et al. 2012; Kurz et al. 2019; Maroto 2019). Debt burden among young adults has risen substantially relative to previous generations, with a pronounced shift to unsecured debt and student loans (Addo et al 2019; Houle 2014; Marato 2019). Today, families are dedicating more of their resources to pay for college, reporting an average of $26,226 spent on college, typically using income and savings to cover 43% of the costs. More than half of families borrow to pay for college (Sallie Mae 2018, 2019). Based on Federal Reserve’s G.19 reports, total student debt surpassed total credit card debt in June of 2010, and to much fanfare, student loan debt passed the $1 trillion mark in May of 2012. Such milestones likely shifted the attention of researchers from student experiences with credit cards toward student loans.

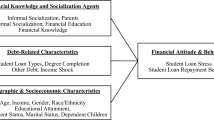

The studies selected for this decade review theme seek to understand the individual, family, and financial conditions that inhibit or enable the successful development of college students’ financial behaviors, skills, attitudes and well-being indicators. In general terms, early work on college student finances focused on individual financial behaviors such as credit card use and student loan default. This work led to studies of the antecedents to positive financial behaviors (e.g., socialization and education) as well as the resulting impact of adopting positive financial behaviors on measures of financial well-being and overall subjective well-being. With 20 articles as a foundation, half from a special issue on student loans, this review is organized into four sections. The first section provides a general overview of the college-going young adult financial behaviors and financial wellness outcomes. The second section summarizes the reviewed research that investigates financial behaviors and the factors that predict them. Section three summarizes the decade review studies that highlight college student financial and personal well-being and other life satisfaction outcomes. With the decade review studies as an underpinning, the final section offers recommendations for future directions in the scholarship on college financial issues.

Trends in Student Financial Behavior and Financial Well-Being Outcomes

Over the past decade of research on college student financial issues, 20 related papers were published in JFEI reflecting the major themes found in the wider literature. For those new to this research theme, an overview of historical and current trends in student financial behavior and outcomes is summarized well in Montalto et al.’s (2019) descriptive study. They drew a roadmap of financial wellness that tracks studies of individual financial behaviors involving credit cards and student loans, to studies of financial capability and financial literacy, to more general constructs like financial well-being, financial stress, and financial self-efficacy. The organization of this decade review works in somewhat corresponding fashion to Montalto et al.’s organization.

Evidence from two administrations of the Study on Collegiate Financial Wellness (SCFW), a nationwide data collection effort involving multiple post-secondary institutions, illustrated the state of college student financial behaviors and financial wellness in 2014 and 2017. Credit card use was highlighted as the earliest area of research on college student finances, with studies showing both positive and negative outcomes for college student financial wellness (Hayhoe et al. 1999; Montalto et al. 2019). In the 2017 SCFW about 60% of the sample held at least one credit card and almost 60% of these card holders expected to graduate with no revolving debt on the card (Montalto et al. 2019). There was no strong evidence that young adults mismanage credit cards (Cloutier and Roy 2020; Hancock et al. 2013; Robb 2011; Montalto et al. 2019).

Student loans were embedded in a broader discussion of college student financial wellness which was described as a multi-dimensional concept. The study reported on the steadily increasing use of student loans to finance education relative to grants and family resources. Just over half of the SCFW respondents reported ever having a student loan and expected total debt at graduation among borrowers was nearly $24,000. Among the approximately 50% of students with no student loans, 44% said they were not comfortable with borrowing, and almost 40% reported that parents and family discouraged the use of loans to pay for education. The concept of “loan aversion” was but one of the many areas where the significant role of parents and socialization was highlighted in the survey.

Research on college student persistence and degree completion was characterized as “mixed,” and the lack of a clear association between student loan use and academic outcomes was attributed to wide differences in measurement of loans, time periods studied, and quality of the data. Regarding repayment and default on student loans, degree completion and total amount of debt were shown to be critical in previous studies. Both anticipated and actual default rates rose precipitously among borrowers who did not finish their degrees. Planning and budgeting was also highlighted in a striking SCFW 2017 finding that almost half of the respondents reported having no idea what to expect in terms of monthly student loan payments upon completion of their education (Montalto et al. 2019). Within the past decade, the financial matters of emerging young adults has become a popular focus and Montalto and colleague’s (2019) review provides a window to the nuances and complexities involved in studying this research theme.

Financial Behaviors of Young Adults

Among the reviewed research, the financial behavior of young adults has been measured as a phenomenon in general and at the more granular level (e.g., credit card usage or repaying student loans). Some studies take a strength-based approach, estimating what predicts healthy behaviors (Kim and Torquati 2019; Robb 2011; Watson and Barber 2017) versus a deficit approach that frames financial behaviors as problematic (Worthy et al. 2010). In the decade review articles, general financial behavior varied greatly in the content focus and the range of measurement items administered. Watson and Barber (2017) measured the frequency of healthy financial behavior of young adults in the previous 6 months using three items, tracking monthly expenses, spending within the budget, and saving money each month for the future. Worthy et al. (2010) used these nine items: “(1) thought about dropping out of school and working; (2) had trouble paying bills; (3) borrowed from friends or family to pay bills; (4) spent student loan(s) or scholarships on non-school items and/or activities; (5) maxed out credit cards; (6) wrote at least one check knowing it was bad; (7) pretended to have more money than he or she actually had; (8) got a job because of financial need; and (9) had an overdrawn checking account (p. 165).” Kim and Torquati (2019) used a 16-item measure that included living paycheck to paycheck, tracking spending, and estimating net worth. The inconsistencies in the approach to studying financial behaviors, across general financial behavior outcomes and within specific financial behaviors, and the variables of interest predicting both, make comparisons problematic.

Of the reviewed studies of young adults’ financial behaviors, almost all have been cross-sectional student samples, few studies are longitudinal or nationally representative. Studies are mostly convenience samples that are typically based on self-reported information, most have robust samples in terms of size but no sampling strategy was used to obtain them. Studies were motivated by unhealthy outcomes (e.g., stress, loan burden, degree attainment) associated with problematic financial behaviors (e.g., risky behaviors), while others searched to identify the determinants of healthy financial behaviors (e.g., financial knowledge). The variables of interest used to predict financial behaviors differed greatly, from individual factors such as sensation-seeking to family process factors like parent financial socialization. The diverse findings of the review articles are organized by the explanatory variables used to predict financial behaviors. These variables largely fall into individual factors, family and family process variables or both. Table 1 presents a summary of studies related to financial behaviors.

Individual Factors Associated with Financial Behaviors

Sociodemographic Factors

Structural categories of age, gender, and race/ethnicity are valid explanatory factors for financial behavior. Studies in this review mostly modeled age, gender, and race/ethnicity as covariates and seldom as an explanatory variable in model analyses, likely because it would undermine the investigation’s research goal. In a study of the association between sensation-seeking and problematic financial behaviors, age (range of 18–25 years old) and gender (being female) was associated with more problematic financial behaviors, but race/ethnicity had no association (Worthy et al. 2010). Older students (measured as class rank) and females were more likely to have two or more credit cards, and older students were more likely to have $500 or more in credit card debt; gender was not included in the debt model (Hancock et al. 2013). Robb (2011) reported credit card behavior was not associated with gender, but minority group membership and age (measured as class rank) was associated with greater rates of irresponsible credit card behaviors.

Providing the only comparative investigation based on sociodemographic factors, Addo et al. (2019) modeled cohort and gender differences to determine whether student debt played a role in young adults’ transition to marriage. Among the most recent cohort, females with student loan debt were less likely to enter into a first marriage compared to females from the older cohort. For males, while student loan debt increased the likelihood of entering into a first marriage among the older cohort, it had no effect on marital formation among males from the younger cohort. Other financial holdings, including unsecured debt, home ownership, and financial assets, increased the transition into a direct marriage for females, regardless of cohort membership. Survey data was mostly utilized in the decade review research, with a few exceptions. Bartholomae et al. (2019) took an experimental approach by manipulating the framing of the student loan decision. There were no gender differences between male and female participant’s evaluation of the decision scenarios when loss, gain, and aspiration frames were presented, and no gender differences in student loan decisions when the gender of the scenario subject was manipulated. The implications of the findings highlight a shift to gender-neutral attitudes toward student loan borrowing and degree-seeking motivations.

Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), Kimmes and Heckman (2017) examined the influence of six mediators in the relationship between parenting style and the decision to enroll in college. They controlled for gender and race/ethnicity in their study, but no discussion was devoted to these variables since they were not of central interest to the study. Gimenez-Nada and Ortega’s (2015) study focused on time dedicated to friends, peers, and community (measured as NGOs). The study found females were more altruistic, devoting more time to family and friends compared to males and females reported higher levels of satisfaction with their contribution. Age was not associated with time dedicated. The complexity of structural variables and their intersectionality require systematic analyses, future scholarship would benefit from such examinations (see critical reviews of gender and race; Hamilton and Darity 2017; Sent and van Staveren 2019).

Developmental Stage and Adulthood Status

Although most studies took a narrow focus on traditionally aged (18–25) college students, a few studies integrated the developmental stage of emerging adulthood as a conceptual factor in consideration with financial behaviors. Worthy et al. (2010) were the first to explore emerging adulthood in the context of financial behaviors, relying on Arnett’s (2002, 2004) extensive work that identified adulthood as beliefs about: “(a) marriage or settling down; (b) independent decision making; (c) financial independence from parents; and (d) less questioning of parental religious beliefs (p.165).” They found that college students who believed they fell more into an adult status, rather than as an emerging adult, tended to engage in more problematic financial behaviors (Worthy et al. 2010).

The financial tie of support between parents and young adults has increased over time (Kornrich and Furstenberg 2013; Marato 2019). Research on this link indicates variability by type of support and duration, with young adults displaying consistent, quick, or gradual financial independence or young adults who are consistently supported (Bea and Yi 2019). Robb (2011) explored college students’ financial independence, a key marker of adulthood. Being financially independent was associated with less responsible credit card behavior, in particular, there was a greater likelihood of young adults maxing out their credit card and being less likely to pay it off in full. However, Robb (2011) found that students responsible for monitoring and making their credit card payments appeared to be more responsible with their credit cards.

A milestone to adulthood occurs when young adults leave their parents’ home to live on their own. The concept of autonomy and financial independence was a primary feature of Watson and Barber (2017) cross-sectional study of Australian young adults (ages 17–21). They used path models to estimate the association of parent or peer financial socialization and found living independently had differential effects on these sources of financial socialization. Among employed young adults, living independently appeared to raise the influence of perceived injunctive parental norms (how young adults think their parents expect them to behave), and had no effect on parental or peer descriptive norms (how young adults think others behave). Conversely, among college going young adults, living independently had no effect on injunctive parental norms, but it appeared to reduce the influence of parental or peer descriptive norms. Maroto (2019) investigated the role of living arrangements, her findings on its association with parental household wealth is presented later in the discussion of the consequence of financial behaviors on other outcomes.

Employment is a socialization factor considered in the larger literature. Some studies in the current decade review examined the role of employment but not as purposefully as Watson and Barber (2017) study of healthy financial behavior. As just noted, they examined the patterns of young adults who chose working full-time compared to those attending college directly after high school. When investigating credit card behaviors, Hancock et al. (2013) study did not find work experience, measured in years, to have an association with the number of credit cards college student had or whether a college student had $500 or more in credit card debt.

In this decade review, scholarship was advanced by those studies that investigated young adults’ individual perceptions and outlook, which tend to be connected with an emerging adult’s developmental stage and their financial behavior. For example, one’s time orientation or preferences, attitude toward risk, and willingness to engage in risky and sensation-seeking activities were considered (Kimmes and Heckman 2017; Robb 2011; Worthy et al. 2010). College students with higher sensation-seeking scores and other risky behaviors (i.e., gambling, smoking, alcohol use, binge drinking) tended to engage in more problematic financial behaviors (Worthy et al. 2010). In the relationship between parenting style and the decision to enroll in college, Kimmes and Heckman (2017) investigated the mediating role of a young adult’s willingness to take risks and time preference (measured as smoking behavior). Risk tolerance had a direct positive path to the college enrollment decision, increasing the likelihood of enrolling, whereas time preferences had a direct negative association, decreasing the likelihood of college enrollment. Uninvolved parenting was associated with young adults holding more immediate time preferences whereas authoritative and permissive parenting styles was associated with a longer time preference. Parenting style was not associated with young adults’ willingness to take risks. These articles illustrate the growing interest in including personality-type factors in the study of financial behaviors, future scholarship should continue to extend this line of inquiry.

While these studies advanced scholarship by digging deeper into the psychological landscape of college student financial behavior, the next decade of research will benefit from scholars investigating the cognitive processes at work as young adults approach, plan and manage decisions related to their finances. Montalto et al. (2019) was the only study to describe the multiple factors used by students in a financial decision. Specifically, they describe how students arrived at the decision of how much to borrow in student loans. Simultaneous strategies were used in this decision-making with approximately four in ten indicating they borrowed only what they needed, borrowed as little as possible, and/or used a budget in the decision-making process. Eight in 10 students relied on others to help with decisions, most consulted parents or guardians, followed by a financial aid counselor or the Internet. Research has focused on the competency of young adults in the domain of financial decision making, like credit card behavior, future scholarship can help understand the complex process of financial decision making.

Financial Attitudes

Financial attitudes, like being fearful of taking on too much debt or perceiving the use of credit cards or loans as too costly, influence financial behavior. Financial attitudes are influenced by parents and a few of the reviewed studies explored this relationship (Hancock et al. 2013; Kim and Torquati 2019). The financial attitudes of college students was captured by Kim and Torquati (2019) with 31-items that measured perceived control over managing money, the importance of insurance, budgeting and savings behavior, and confidence in ability to manage credit and debt. In moderated mediation models, parental financial behaviors (measured as modeling sound money management) positively affected college students’ financial attitudes, and college students’ financial attitudes were positively associated with healthy financial behaviors. Parents’ disclosure of financial information and family communication patterns moderated the relationship between parent financial behaviors and college students’ financial attitudes. In a study of the financial attitudes of college young adults, specifically a fearful attitude toward the use of credit cards, Hancock et al. (2013) found young adults were less likely to have credit cards if they had a fearful attitude towards them. Young adult students who were comfortable paying just the minimum each month on their card had a greater likelihood of having two or more cards and maintaining credit card debt over $500 (Hancock et al. 2013).

Studies in this decade review modeled attitudes in student loan choice using an experimental approach. Given that literature illustrates that consumers do not act rationally, even when provided with full information, Caetano et al. (2019) were interested in understanding why people do not invest in education, given the high rate of return. With a sample from three Latin American countries, Caetano et al. found evidence of debt aversion when hypothetical student loan decisions were manipulated with framing and labeling. Motivated by human capital theory and the differential returns to education between males and females, Bartholomae et al. (2019) did not find gender differences in the student loan decision when providing loss, gain, and aspiration frames to the participants. A strength of the decade in research on financial behaviors was the introduction of psycho-social and financial attitudes among the individual factors examined, and the increase in investigations using experimental conditions.

Financial Knowledge and Financial Education

Montalto et al. (2019) summarized the work in the broad area of college student financial literacy, defining the term and linking knowledge to intentions to adopt positive financial behaviors. Previous evidence demonstrated a positive association between financial knowledge and financial behaviors, and subjective measures of financial knowledge have had a greater association than objective financial knowledge (Fan and Chatterjee 2019; Robb 2017). Robb studied financial knowledge and responsible credit card behavior and noted that ample research shows that college students are actually responsible in credit card behavior, but low in financial knowledge. Robb (2011) found greater levels of financial knowledge predicted college student’s responsible use of credit cards. Financial knowledge was measured as low or high, high reported financial knowledge was associated with more responsible credit card use, low financial knowledge with less responsible credit card use. Objective financial knowledge reduced the likelihood of late student loan payments (Fan and Chatterjee 2019). In a study of the influence of financial socialization and financial knowledge on the number of credit cards and the amount of credit card debt held by young adults, Hancock et al. (2013) found parental interactions (measured as arguing) was a strong predictor but financial knowledge had no association with having two or more credit cards. The conclusion and recommendations relative to financial literacy was that there is much research still to be done to explain differences across gender, race, income, and family experiences (Montalto et al. 2019).

Despite being a research theme on its own, the topic of financial education was absent from most of the reviewed research. Results from the SCFW in 2017 showed higher personal financial education participation rates in high school than in college (Montalto et al. 2019). Similar to the broader literature, the role of financial education was not a consistent predictor of the financial behaviors of college students. Young adults who had taken a financial education course were more likely to pay off their credit card cards; but were also more likely to have a credit card at its maximum limit or made only the minimum payment (Robb, 2011). Fan and Chatterjee (2019) found the likelihood of late student loan payments was reduced when young adults had participated in financial education.

Maurer and Lee (2011) compared knowledge levels and behavioral intentions for students in a one-hour peer financial counseling session to those in a semester-long course in personal finance. While the research was conducted on a single university campus, this study stands alone among those published over the decade in JFEI as it follows a program evaluation approach. Based on pretest/posttest results, Maurer and Lee showed equal gains in learning about budgeting and credit between the counseled and semester-long educated college students. Somewhat surprisingly, students counseled by peers on budgeting reported lower anticipated use of effective budgeting tools. The authors speculated that lower anticipated positive financial behaviors may result from the fact that the budget-counseled group started with a relatively high level of budgeting knowledge, reducing the impact of any gains on behavior change. Students self-selected into the counseling and semester-long course, any future studies that can creatively introduce random assignment to educational interventions stands to move the evaluation of financial education programs forward.

Family Financial Background

Financial stability, or financial problems of one’s family of origin, contribute to a young adult’s healthy or unhealthy financial behaviors. A stable financial background provides a stronger foundation for young adults than less stable families (Worthy et al. 2010). Parental income was included as a control in Kim and Torquati’s mediation models. Parental income was positively associated with parental financial behaviors and with college students’ financial attitudes in all of the models. College students in Kim and Torquati (2019) study provided information about their socioeconomic status (SES) when growing up, but it was not used to model financial behavior. Family financial background was investigated in a convenience sample of college students (18–25 years), college students whose parents received public assistance were more likely to engage in problematic financial behaviors (Worthy et al. 2010). In their investigation of credit card behaviors, Hancock et al.’s (2013) descriptive findings found no relationship between parental income level and parental arguments about finances. A study of college enrollment only looked at family financial factors in terms of descriptive results, and found families that exhibited authoritative and permissive parenting styles had higher levels of net worth, income, and education, compared to authoritarian parenting style who had the lowest levels of these financial variables (Kimmes and Heckman, 2017). Given the strong influence of a young adults’ financial upbringing, future studies should continue to examine these important variables.

Family Process Variables

To determine its relationship with financial behaviors, scholarship in this decade review included family process variables, such as parenting style, socialization, and family communication processes. An online survey administered at multiple universities in six states allowed Hancock et al. (2013) to study the influence of parental interactions, work experience, financial knowledge, and attitudes on the number of credit cards and credit card debt. Parental interactions, measured as arguments about finances, increased the likelihood of maintaining credit card debt over $500 and owning two or more credit cards. Kimmes and Heckman (2017) examined the influence of six mediators in the relationship between parenting style and the decision to enroll in college. Parenting style had no direct association with college enrollment decisions in their models. Parents’ expectation that their child attain a degree by age 30, students’ own expectation of degree attainment, academic achievement (GPA) and cognitive ability were mediators, increasing the probability of enrolling in college. Authoritative parenting style was associated with longer time preferences and greater cognitive ability, academic achievement, and subjective probability of graduating. Young adults with parents who exercised permissive parenting styles had longer time preferences and greater academic achievement. Uninvolved parenting style reduced parental expectation of their child attaining a degree and shortened the time preferences of young adults (Kimmes and Heckman 2017). All three parenting styles had a negative association with time preferences, measured as smoking.

Fan and Chatterjee (2019) investigated young adults’ difficulty managing student loan payments, and found that increasing levels of financial socialization, financial education, and objective financial knowledge all reduced the likelihood of late student loan payments. Relative to those holding only federal student loans, borrowers with both federal and private loans were more likely to be late on debt payments. In four moderator–mediator models, Kim and Torquati (2019) showed that parental financial socialization and healthy financial attitudes among college students was strengthened by parents who disclosed financial information during conversations or who valued an open and non-conforming family communication style. Healthy financial attitudes were weakened when parents avoided conversations about money or emphasized a family communication style that valued conformity rather than homogeneity. As described earlier, Watson and Barber (2017) investigation of the association of parent financial socialization on healthy financial behaviors found different associations among outcomes for young adults who chose to work full-time versus attending college. In contrast, peer financial socialization had a positive association with healthy financial behaviors for both groups. The transition to adulthood and the persistent reach of parental influence on financial behavior is a much-needed area of scholarship. The articles in this decade review highlighted new, novel and untested conceptual factors to predict financial behaviors. Future research continues to be necessary to understand the factors that help individuals to develop healthy financial behaviors.

Scholarship in this decade review mostly model financial behavior as an outcome, others consider the consequence of financial behaviors on subsequent work, family, and financial decisions. For example, growing student loan debt spurred scholars to examine the consequence of greater debt burdens. Addo et al. (2019) investigated gender patterns of marital formation of young adults using two generational cohorts from the National Longitudinal Studies. Their findings suggested that student loan debt was an economic barrier to marital transitions among more recent cohorts. Specifically, young women who would have gone directly into a first marriage were delayed, compared to those never marrying. For men, the association of asset and debt holdings did not delay relationship formation among males in the older cohort, neither was there an association among younger cohort males. Among men and women in both cohorts, student loan debt had no association with cohabitation. Using propensity score matching and linear regression, Maroto (2019) utilized three waves of the Canadian Survey of Financial Security dataset to determine whether coresidence with and support for young adult children was associated with parental household wealth. Young adults’ coresidence was a detriment to family assets and parental household debt levels, which were used as a proxy for household economic security. Scholarship would benefit from additional studies that examine the role of student loans on the life transitions and trajectories of young adults. Addo et al. (2019) demonstrated the reach of financial behaviors on non-financial outcomes and transitions, whereas Maroto (2019) showed the bi-directional nature and linked financial lives of families. These studies are exemplars of this decade review theme and a research priority for future scholarship should closely approximate them.

Financial and Personal Well-Being

It is fair to conclude that the overarching goal of researchers in the field of personal and consumer finance is to better understand the mechanisms that contribute to financial and general well-being, and ultimately explain the role of financial wellness in overall wellness. Over the decade, seven college student financial well-being articles focused on a latent construct indicating either financial well-being or subjective well-being. In JFEI, studies of financial satisfaction and financial stress emphasized the role of student loan debt in financial well-being. A single study published in the journal focused on the role of financial management behaviors such as budgeting, savings, and spending and its link to financial well-being. Four of the seven studies centered on general life satisfaction and mental health outcomes. As with the financial well-being studies, two focused on the role of student loans and debt in influencing general well-being. One linked financial stress levels to subjective well-being, and a final study highlighted the role of perceived financial strain as the mechanism that connects financial behavior to general life satisfaction and mood. Table 2 presents a summary of studies related to financial wellness and general wellbeing outcomes.

Financial Well-Being

The financial well-being constructs measured in the SCFW related to financial stress and financial self-efficacy (Montalto et al. 2019). The literature reviewed showed financial stress or anxiety on the rise with as many as 7 in 10 students stressed over their personal finances (Heckman et al. 2014). Moreover, previous work linked financial stress to lower subjective well-being, and reactive instead of proactive approaches to financial management (Serido et al. 2014). In the SCFW, among debt holders, almost 80% of students reported student loans as a significant source of stress, but only 30% reported such stress caused by credit cards. The level of control or self-efficacy reported among college students was quite high, for example almost 9 in 10 said they had the knowledge needed to make good financial decisions. The interaction of knowledge and confidence in using this knowledge was discussed as a well identified antecedent to positive financial behaviors.

The studies of general financial satisfaction all used large scale surveys to primarily assess the association between financial behaviors, student loan decisions, and financial well-being. Likely in response to well documented rises in student loan debt and default (Looney and Yannelis 2015), two of the studies used the 2015 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) to identify the relative association of private and public student loans with specific indicators of financial well-being. Measures of financial well-being were primarily single items, and often simple yes/no indicators of personal worry about student loan debt or satisfaction with prior borrowing decisions. One study used an established and tested 8-item scale of financial well-being in a study focused on the role of financial behaviors in satisfaction.

Robb and colleagues (2019) used cross-sectional, nationally representative data from the 2015 NFCS to examine the influence of student loan debt on a general measure of financial satisfaction. The single item used to measure financial satisfaction was a 1–10 ranking (not at all satisfied to extremely satisfied) response to the question, “Overall, thinking of your assets, debts and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition?” The direct effects of student loan debt on financial satisfaction were estimated in a single model along with indicators of financial knowledge, education, financial socialization, financial attitudes, financial behaviors, financial strain, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Over a wide age range (18–54), student loans did not associate with financial satisfaction, and the same was found in a narrower range of younger adults (18–34). Notably, other factors such as parent modeling (socialization), financial attitudes (risk tolerance and worry about retirement), credit and debt circumstances, and indicators of economic pressure more strongly associated with financial satisfaction. The two indicators of financial knowledge (subjective and objective) yielded opposite associations, with subjective financial knowledge associating positively with financial satisfaction.

Turning to a selection model based on having student loans, the type of student loan used by borrowers appeared to relate to financial satisfaction. Those with only private loans had higher levels of satisfaction relative to those only using federal student loans, even when controlling for knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, strain, and demographics. This was somewhat surprising given the relatively favorable terms of federal loans. The authors speculated that those holding only private loans may have had more favorable professional opportunities and earnings expectations (not captured in the model), and these higher expectations translated to higher financial satisfaction, but the question remains unresolved and this result indicates a fruitful direction for future research. Finally, Robb et al. (2019) explored the likelihood of student loan borrowers making the same borrowing decision which was considered an alternate indicator of financial satisfaction for the student loan-holding subgroup. With this specification, use of private loans negatively associates with the likelihood that a borrower would make the same loan decisions. In other words, private loan holders were not happy with their past student loan decisions. Along with the type of student loan used, parent modeling and financial socialization seemed to be a positive factor in making acceptable loan decisions.

Fan and Chatterjee (2019) also used a nationally representative sample drawn from the 2015 NFCS to investigate difficulty managing student loan payments and worry about paying off total student loan debt. Conceptualized as a financial socialization model, debt stress was modeled on financial knowledge, education, and learning from parents along with debt-related characteristics and demographic/socioeconomic information. Over half (55%) of the 25–64 year old sample of student loan borrowers worried about paying off their student loan debt. An additional focus of the study was on type of student loan (federal, private, or both). In the second model of financial stress caused by student loans, again those with both federal and private loans worried more about making debt payments than those with only federal loans, and, similar to Robb et al. (2019), it appeared that those holding private loans perceived their financial wellbeing to be better than those holding only federal loans. As in the previous model, financial education, socialization, and objective knowledge all negatively associated with worry about student debt repayment. A financial education and financial socialization interaction term coefficient was also negative, indicating that parental socialization may modify the effectiveness of financial education when it comes to debt stress. In comparing the fit of the two models, the specification with a subjective outcome (worry about debt) was slightly better than that using the manifest outcome (being late on payments). The authors consider their findings regarding socialization, financial education, and financial knowledge supportive of previous studies by Lusardi (2003), Jorgensen and Savla (2010), Shim et al. (2010), Shim et al. (2013), and Brown et al. (2016).

Gutter and Copur (2011) reported the link between financial behaviors and financial well-being employing a survey conducted at 15 US universities in the fall of 2008. Conceptualized in the Deacon and Firebaugh (1988) family resource management framework, inputs such as financial disposition and financial education were expected to work through financial behaviors resulting in the output of financial well-being. The InCharge financial distress/financial well-being (IFDFW) scale (Prawitz et al. 2006) was used to measure financial well-being. The 8-item scale captures feelings about one’s current personal financial situation and was shown to be valid and reliable within a college student sample. The study relied on additional established scales to measure financial disposition such as the: materialism scale (Richins and Dawson 1992), money ethic scale (Tang 1992), consideration of future consequences scale (Strathman et al. 1994), and the compulsive buying scale (Faber and O’Guinn 1992). A bivariate analysis indicated that budgeting and savings track with higher levels of perceived financial well-being, and risky credit behaviors (maxing out cards or paying late) linked to lower financial well-being scores. In the multivariate models, positive financial behaviors mainly correlated with higher levels of financial well-being, however, budgeting proved to be negatively related to financial well-being when controlling for all “input” factors in the Deacon and Firebaugh model. In particular, the addition of the compulsive buying scale and a measure of financial self-efficacy or sense of control appeared to modify the impact of the budgeting behavior variable in the model. The general finding of positive financial behaviors associating with higher self-assessed financial well-being was linked to previous studies by Shim et al. (2009), Xiao et al. (2006), and Xiao et al. (2009). Gutter and Copur (2011) concluded with pointed statements calling for “action-oriented financial education programs” given the observed link between positive financial behaviors and financial well-being (p. 710).

In combination, the studies of financial well-being did not support expectations that student loan debt has a negative impact on perceived financial satisfaction or wellness. Equally surprising was the finding in two studies showing a positive association between the use of private student loans and financial well-being. The result was surprising given the less beneficial terms of private loans, yet authors partially explained these results through the type of borrowers using private versus public student loans. Generally, recommended financial behaviors were shown to positively associate with financial well-being. All studies of financial well-being used some form of direct estimation of association based on a cross-section of college students and/or student debt holders. Unfortunately, the design of the studies does not allow for conclusions or statements based on causal relationships.

Life Satisfaction and Well-Being

Personal well-being, not specifically tied to finances, was the main outcome in four studies. Two of the studies used established scales to measure satisfaction and well-being, yet no two studies took the same approach to outcome measurement. Measures of well-being ranged from a single scale item of self-assessment of personal satisfaction to use of a well-established (within the wider psychology literature) 6-item scale of psychological distress. Two of the four studies of general well-being used the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) allowing for assessment of individual changes in satisfaction or mental health over time. Three of the four studies were based on a traditional college aged sample and a fourth examined the role of student loan debt across age groups, including individuals up to age 54. Three of the four studies estimated direct effects on well-being through widely varied multiple regression specifications. The fourth study compared a direct effects specification with a structural meditational model focusing on the role of perceived financial strain on satisfaction and mood.

Robb (2017) focused on the Satisfaction with Life scale from Pavot and Diener (1993), where five 5-point scale items were summed to assess levels of agreement with statements on positive life outcomes. The study was exploratory, primarily explaining the role of finances in subjective well-being. In a convenience sample of 324 undergraduates, financial stress negatively associated with subjective well-being. Similarly the feeling that “finances restrict options” (economic pressure) associated with lower values on the satisfaction with life scale. Self-efficacy, measured with a 4-item sum of scale scores of feelings of control over finances, associated positively with subjective well-being. Robb (2017) also looked at reduced credit hours and perceived debt burden as a barrier to degree completion. College students with higher stress were more likely to reduce credit hours taken and perceive their burden significant enough to impede degree completion. Notably, Robb used the Northern et al. (2010) Financial Stress scale-college version. Of the original 22-item scale of financial stressors (e.g., being behind on payments, having large debts, having a low credit score), 14 were retained and used in the analysis. The 14 stress items for college students primarily came from decision-making under significant resource limitations. Higher financial self-efficacy lowered the chances of taking on a reduced course load and showed no relation to perception of college persistence. Even with employment status, debt amounts, and credit card use included in the models, the strongest associations with well-being were shown to be the subjective factors related to health and finances. Similarly, subjective financial knowledge (or confidence in what is known about finances) appeared to lessen the likelihood of feeling burdened by student debt. Finally, Robb highlighted findings related to financial stress as linked with previous studies outlining the ill effects of financial stress on college student’s subjective well-being (Heckman et al. 2014; Joo et al. 2008; Letkiewicz et al. 2014; Robb et al. 2011).

Zhang and Kim (2019) used five waves from the Transition into Adulthood Study from the PSID to identify the relative impact of student loan versus credit card debt on psychological distress over time. Following Brown et al. (2005) and others, debt was considered a source of economic pressure leading to uncertainty and inability to become self-sufficient. With the advantage of multiple observations over time, the source of change in distress was identified within individuals. Using changes in the Kessler scale of psychological distress, which centers on respondent reflection of their emotional state over the past 30 days, the study showed that changes in debt levels led to changes in distress. Most significantly, the negative impact of credit card debt on psychological distress was assessed to be approximately twice that of student loan debt. Being employed while holding credit card debt reduced distress as did finishing a 4-year degree when holding student loan debt, indicating that perceived economic pressure was dependent on situation. Distress was shown to increase with income, and though somewhat surprising, this result fits with previous findings where employment was a source of stress for college students (Neill 2015).

Based in stress response and stress coping theory, Kim and Chatterjee (2019) used three waves of data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to examine the relative role of student loan debt in perceived life satisfaction, psychological problems, and self-assessed health status. Given the longitudinal nature of the PSID, the impact of student loan debt on latent outcomes was observed over time, setting this study apart from much of the student loan literature. Across the adult population, having student loan debt preceded lower self-assessment of life satisfaction and higher reports of psychological problems. Student loan debt from previous waves appeared to negatively impact health status among Hispanics. The reported associations of current and lagged credit card and medical debt were similar to those found for student loan debt. Kim and Chatterjee considered their results consistent with previous studies of debt, life satisfaction, and psychological problems citing Adams et al. (2016), Drentea and Lavrakas (2000), Sweet et al. (2013), and Walsemann et al. (2015) among others.

Watson et al. (2015) investigated life satisfaction and depressed mood among college students in a Western Australian university. By adopting the instruments used in the Arizona Pathways to Life Success for University Students (APLUS), life satisfaction and depressed mood were measured with three and four item conceptualized scales. Central to the study was the comparison between a mediation model, where perceived financial strain mediates the effect of financial behaviors, and the “literature” model, where behavior and perception of economic situation independently and directly impact satisfaction and mood. Based on model fit, the mediation model proved superior, implying that engaging in money saving behaviors impacts satisfaction and mood only through individual perception of difficulty paying for things and worrying about money (perceived financial strain). Incorporating perceived economic well-being as the mechanism through which behaviors link to general satisfaction and psychological health helped explain the process and relative importance of objective and subjective economic indicators. Watson et al. (2015) identified the “psychological mechanism” through which objective resource limitations affected student well-being. Budgeting or “economizing behaviors” could have multiple impacts on general well-being, but when analyzed through their impact on personal perception of economic pressure, their effect was less ambiguous. In other words, general life outcomes were less dependent on objective economic circumstances, and more influenced by the personal perception of these circumstances. Bacikova-Sleskova et al. (2007), Chou et al. (2004), and Mistry et al. (2009) were cited as also showing similar use of indirect indicators of satisfaction and mood.

When compared to the other three studies of life satisfaction and subjective well-being, the Watson et al. (2015) study staked a wider claim in approach and implications. By conducting a general test for model fit, contrasting the more prevalent in the literature direct effects approach with a structural mediational model, the study discussion and implications focus on the psychological process linking behavioral observations to general well-being. A second significant contribution of Watson et al. (2015), shared with Robb (2017), is an observation of the stronger role of personal perception of economic pressure over objective measures of financial position. The implications are important as approaches to intervention can focus on changing consumer sentiment over changing objective economic outcomes (e.g., income or net worth) or financial management behavior (e.g., budgeting, savings, and investing). Finally, two of the four studies of subjective well-being focus on the role of student loan debt. Surging student loan debt through the past decade is the most frequent motivator for studying the finances of emerging adults. While student loan debt appears to associate with well-being, the negative impact is less when compared with credit card debt and may actually be a protective or buffering factor among emerging adults with 4-year degrees.

Recommendations for Future Scholarship on Financial Behaviors

Ultimately, the goal of this decade review’s research theme is to understand the conditions, characteristics and skills that promote the healthy development of sound financial management behaviors and well-being outcomes of young adults. Understanding that only 20 studies were selected for this decade review, research priorities for the next decade of researchers are related to research design, data and measurement issues, theoretical conceptualization and modeling, and studies that produce replications.

Too often, studies of college students are limited to the scope of a single university and to one point in time. Data sources in the next decade need to move beyond convenience samples. The use of nationally representative data sets (e.g., NLYS) were more the exception, as were experimental study designs. Prevalent in the decade review were cross-sectional data and thus study models suffer from an inherent simultaneity problem. Longitudinal research design can address issues of ordering, tracking changes over time, and permit causal analyses. For example, it is still not clear if knowledge leads to better financial behaviors, if practicing good financial behaviors helps increase knowledge, or whether these concepts are recursive. Little has been shown beyond association between key constructs such as financial socialization, financial capability, behaviors, and general wellness outcomes. Kim and Chatterjee (2019) and Zhang and Kim (2019) were exceptions over the last decade in JFEI as they used longitudinal data in studies of satisfaction and psychological distress, but the research design did not speak fully to causality. The long-term consequences of financial attitudes, such as debt aversion, or financial socialization, on financial outcomes is little understood without longitudinal data. In terms of changes over time and causal analysis, some of the most promising work focused on the college student population comes from the APLUS study. For example, Rudi et al. (2020) used three waves of the APLUS to estimate a multigroup cross-lagged panel model of parent socialization and financial self-efficacy. By implementing a research design that follows the same college students over time, a clear causal relationship is established from parent communication and modeling leading to financial self-efficacy. Unfortunately, such studies are too few in the literature and APLUS data collection ended after the fourth wave, when the students were in their late twenties.

The reviewed studies were all quantitative research designs. To deepen our understanding of the tenuous relationships between financial behaviors and outcomes, future studies might incorporate mixed methods or qualitative approaches. For example, Maroto (2019) studied the shared living arrangements between young adults and their parents. Qualitative work could uncover reasons and motivations for why the adult child came back to live with their parents or remained living with their parents and sharing resources. The perspective of young adults dominated the research reviewed, priority can be given to greater inclusivity to other voices, such as partners and parents. More typically students provided information about their parent’s financial information rather than parent self-report (Kim and Torquati 2019). Future research could experiment with the use of more natural experiments or real world data, like registrar or financial data. The proprietary nature these data, FERPA protections, and the lack of information desired for studying families would need to be addressed first.

Most of the reviewed studies were designed without a sampling strategy. Females tended to be overrepresented, certain majors were oversampled, and minority membership and non-traditional students were underrepresented. For researchers interested in contributing to the next decade of research, we concur with Worthy et al.’s (2010) recommendation that young adults are approached as a heterogeneous rather than homogenous group. Many studies drew samples from public universities, future research should extend to multiple universities for sampling and be sure that a variety of institutional types is represented, as in the SCFW. More purposeful sampling and representative data will allow comparisons among individuals, groups, and other features. Understanding that groups are not homogeneous, students who take gap years, students who are parents, first generation students, students on the GI Bill, and graduate students may have unique financial behaviors and outcomes to uncover. Diverse samples and the intentional design of comparative models can address the tendency of researchers to treat college students as a homogenous group. A careful research design that includes a purposeful strategy to addresses data quality and sampling issues would tackle several limitations at once.

A conclusion of this decade review is that due to methodological heterogeneity, empirical support is largely inconsistent between explanatory factors and outcomes. The variety of measurement in the current review limited the ability to infer and report broadly on the efficacy of individual and family process and their role in whether young adults engage in financially responsible behaviors or mismanage their financial matters. The decade review identified varying degrees of evidence concerning financial behavior and knowledge, however the perception of financial behaviors and knowledge, and not necessarily objective measures, appear to explain more in college student financial well-being. For example, what young adults think about their finances, not what they objectively are, has a more significant influence on behavior (Robb 2017). Watson et al. (2015) elegantly demonstrated that perceived financial strain is the process that links economizing behaviors to well-being. Much of the work on college student finances links to perceived and actual levels of knowledge among college students. Subjective measures of financial knowledge show more impact on satisfaction and well-being outcomes (Robb 2017). Moreover, subjective or self-reports of knowledge positively relate to financial satisfaction and objective measures work in the opposite direction (Robb et al. 2019; Hader et al. 2013; Seay and Robb 2013), implying that it may be as important to make students believe in themselves (increased financial self-efficacy) as it is to actually teach them facts about personal finance. The wide variation in both the dependent and explanatory variables in the reviewed studies is a methodological limitation that future studies can address.

As noted earlier, the variation in measurement of general financial behavior in the decade review articles was somewhat striking, begging the questions, should general financial behavior be measured as a single underlying construct? Are there types of financial behaviors that differ from one another and types that should be grouped together? Which financial behaviors matter most? What associates with the development of healthy financial outcomes? Worthy et al. (2010) recommended the use of a comprehensive measure of financial behaviors. The question remains whether financial behaviors should be measured as a domain specific measure or a general measure. An example of a domain specific financial behavior is Roberts and Jones’ (2001) credit card use scale that Robb (2011) used. It measures five responsible credit card use behaviors: less likely to have card at max limit, more likely to always pay off their credit card; less likely to make only minimum payment; less likely to be delinquent in making credit card payment; and less likely to take cash advances. It is recommended that future research conduct exploratory factor analyses to examine the factor structure of financial behavior, with subsequent testing with diverse populations. Just as the deconstruction of financial knowledge into subjective versus objective concepts provides a means toward refinement, exploratory research is needed to determine whether the deconstruction of general financial behavior is of value. Certainly the use of a general measure prevents the ability to make precise recommendations related to policies and programs.

The previous decade saw more investigations that examined personality-type factors and risk behaviors, like sensation seeking (Kimmes and Heckman 2017; Worthy et al. 2010). Future research may need to be more expansive in its representation of internal (latent) concepts that matter more to financial behaviors and outcomes. Identifying the role of agency, efficacy, empowerment, planning, goal setting, and other executive functioning skills that map onto the development of healthy financial behaviors can help inform decisions related to policies and programs. A recent study showed consumer credit self-efficacy contributed to responsible credit card behaviors among undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate students (Cloutier and Roy 2020), demonstrating a domain specific measure predicting a domain specific behavior. When their modeling of financial knowledge did not predict college students having 2 or more credit cards, Hancock et al. (2013) suggested there was either an issue with the measurement of financial knowledge or an omission bias caused by missing predictor variables. The next decade of research can investigate effective measures that improve financial skills, attitudes and indicators of well-being and have not yet been identified. Studies included psychometrically validated measures but more often developed or adapted measures for the study. As this work continues, the use of well-validated, established scales and measures will be critical for advancing scholarship.

Novel investigations of family processes were demonstrated in the studies, however, few studies explored family characteristics. Kimmes and Heckman (2017) was one of the few to consider family structure as a control, however findings were not discussed since it was not a variable of interest. The review did not include studies that investigated the heterogeneity of SES among study subjects, or control for SES when examining variables of interest. Family structure and SES has the power to drown the effects of other model variables, particularly variables of interest. Financial behaviors and outcome indicators are susceptible to the influence of family background variables, these types of variables deserve greater attention.

Conceptualizing and modeling the relationships among sociodemographic, psychosocial, family, and financial behaviors and outcomes can be difficult. Financial behavior and outcomes can be explained by multiple interdependent factors. These relationships can be bi-directional or circular in nature. For example, a circular relationship has been previously reported between having a credit card by a young adult and credit card debt (Norvilitis and Maclean 2010). Scholarship could address this complexity by simplifying the modeling. Some studies tend to include too many independent variables into the explanatory models when it would be better served with more discrimination.

Understanding the process by which young adults form financial attitudes, skills, and habits is critical in understanding financial and health outcomes. There are plenty of studies assuming direct effects, but Watson et al. (2015) focused on perceived financial strain as mediating financial behaviors and general life outcomes. Watson et al. tested the “literature model” of direct effects in comparison to a mediational model. More work testing explicit theoretical relationships will strengthen the field, especially if it is based on longitudinal data. For example, Gutter and Copur (2011) presented a clear three-level relationship based on the classic family resource management model of Deacon and Firebaugh (1988), but reported direct effects missed the nuance of following inputs to outcomes by way of throughputs or processes. Building our understanding of these processes, where students consolidate experiences, behaviors, knowledge, and resources, which translate into becoming healthy adults, can be the ultimate payoff for researchers of college student finances in the next decade.

Several studies were informed by a theoretical perspective and provided methodological frameworks within a theoretical framework. A theoretical framework can help explain the mechanisms and processes that emerge within and between financial behavior and outcomes. A number of modeling approaches were represented in the decade review studies, many identifying the mediating and moderating influences of key factors. Starting first with a simple mediation model, Kim and Torquati (2019) conceptualized financial socialization, financial attitudes on financial behaviors. Additional moderated mediation models were estimated to test their hypotheses that parents’ disclosure of financial information and family communication patterns moderate the implicit financial socialization (measured as perceived parents’ financial behaviors). They tested their hypotheses and furthered the conceptualization of the family financial socialization. To understand and address the various phenomenon related to financial behavior and wellness, it is recommended that future work conceptualize relationships using a theoretical framework, testing these conceptual relationships.

Using formal, well-developed theories to predict behaviors or outcomes provides conceptual guidance and a framework to develop hypotheses and research questions. Some of the studies explicitly name theories, whereas others are atheoretical. Theories used in the reviewed research included family financial socialization model (Gudmunson and Danes 2011), family resource management theory (Deacon and Firebaugh 1988), human capital theory (Becker 2009), social learning theory (Bandura and Walters 1977), and frameworks grounded in behavioral economics (Tversky and Kahneman 1979). Financial behaviors like those summarized in this review could be explained by principles from cognitive science and neuroscience, new theoretical directions for scholarship.

The study of young adults and emerging adulthood is central to this decade review research theme. Given this dynamic period of development, future research that implements a life course framework as a theoretical perspective would be valuable (Bengtson et al. 2012). Watson and Barber (2017) compared young adult life choices to investigate patterns of young adults who select full-time employment versus those who choose to attend college. The developmental milestone of financial independence looked different for these two groups. College students who delayed this milestone relied more heavily on parental expectations versus employed young adults who had greater access to financial resources and held greater responsibilities had more opportunities to develop financial independence and behaviors. These unique factors highlight the importance of future research focusing on instrumental pathways chosen by young adults within a life course perspective (Watson and Barber 2017).

The link between economic behavior and family is central to JFEI scholarship, thus individual outcomes among young adults and their families are often driven by intergenerational relationships. In the next decade, it is recommended that scholarship apply the linked lives principle of life course theory (Bengtson et al. 2012). The importance of intergenerational links was illustrated in JFEI’s recent publication of Xu’s (2020) study that examined parental foreclosure and the homeownership decision of young adults. Worthy et al. (2010) discussed the effects that the financial behaviors of emerging adults have on their family of origin, with those who seek financial support potentially jeopardizing the financial future of their parents. Maroto (2019) confirmed the complex and sometimes problematic nature of intergenerational ties in her study that showed young adults’ coresidence with parents and parental support undermined parental financial security. Research on the intergenerational networks and the support that flows between them can provide greater understanding of the intricacies of the relationship between financial behavior and outcomes.

The inclusiveness of multi-disciplinary approaches of JFEI is a strength, it richly informs scholarship on any given research theme. This strength also inhibits the ability of scholarship to accumulate a body of findings due the divergent assumptions that various disciplines hold. Worthy et al. (2010) noted that the inconsistencies between their findings and previous scholarship may be attributed to “how the studies were conceptualized, the variables that were included, and the underlying assumptions that guided the research” (p.169). Individual studies demonstrate correlative relationships between various explanatory variables and financial outcomes, but multiple constructs between and within disciplines can hinder empirical conclusions. Consistent use of theory or replication studies could potentially support the capacity to reach consensus and would address this limitation. No two studies published in JFEI over the decade approached the examination of financial behaviors similarly. Models and measurement varied widely, making generalizations problematic. Findings are tentative until subsequent work is confirmed by future studies that use the same approach to measurement and modeling of key outcomes. Kim and Torquati (2019) urged the replication of their results and recommended the expansion of their family financial socialization model by testing other processes that are relevant, and replicating these models. With more studies focused on validating previous findings, authors can make stronger recommendations for policy, planning, and programming.

Limited information about “how” financial knowledge was obtained or developed by young adults is a noted limitation in the decade review studies (Robb 2011). Higher education institutions implement a range of methods, practices, and strategies to address the financial literacy and wellness of its student body (Fletcher et al. 2015). Although there are varying degrees of success, and resources to dedicate to such efforts, future studies should give greater attention to these initiatives when studying financial implications. Many institutions take a multi-prong approach, and as noted in the research reviewed, financial education interventions generally lack necessary specific information on the content and duration of financial education (Fan and Chatterjee 2019; Maurer and Lee 2011; Robb 2011). Replication of promising outcomes across campuses will not happen unless more details are shared on successful interventions.

Conclusion

It is important to remember that this review did not capture all studies that were published in the past decade. College financial implications is a research theme marked by an extensive body of literature that demonstrates a richness of studies designed to investigate the contexts and precursors of financial behavior, skills, knowledge, satisfaction, and life outcomes. We describe a decade of research, and suggest research priorities that builds our understanding of the individual and family processes that promote an opportunity for positive development of healthy financial outcomes. Great strides will be made if the next iteration of research on this theme can produce cumulative findings based on rigorous research designs. Future research can help provide data to inform specific programming models, such as financial education interventions, and policy decisions.

References

Adams, D. R., Meyers, S. A., & Beidas, R. S. (2016). The relationship between financial strain, perceived stress, psychological symptoms, and academic and social integration in undergraduate students. Journal of American College Health, 64(5), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2016.1154559.

Addo, F. R., Houle, J. N., & Sassler, S. (2019). The changing nature of the association between student loan debt and marital behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9591-6.

Arnett, J. J. (2002). A congregation of one: Individualized religious beliefs among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17, 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558402175002.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford Press.

Bacikova-Sleskova, M., Dijk, J. P., Geckova, A. M., Nagyova, I., Salonna, F., Reijneveld, S. A., et al. (2007). The impact of unemployment on school leavers’ perception of health mediating effect of financial situation and social contacts? International Journal of Public Health, 52(3), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-007-6071-4.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bartholomae, S., Kiss, D. E., Jurgenson, J. B., O’Neill, B., Worthy, S. L., & Kim, J. (2019). Framing the human capital investment decision: Examining gender bias in student loan borrowing. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(1), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9603-6.

Bea, M. D., & Yi, Y. (2019). Leaving the financial nest: Connecting young adults’ financial independence to financial security. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(2), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/t6ar5.

Becker, G. S. (2009). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bengtson, V. L., Elder, G. H., Jr., & Putney, N. M. (2012). The life course perspective on ageing: Linked lives, timing, and history. Adult lives: A life course perspective. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t895q0.7.

Brown, M., Grigsby, J., Klaauw, W., Wen, J., & Zafar, B. (2016). Financial education and the debt behavior of the young. The Review of Financial Studies, 29(9), 2490–2522. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhw006.

Brown, S., Taylor, K., & Price, S. W. (2005). Debt and distress: Evaluating the psychological cost of credit. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(5), 642–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2005.01.002.

Caetano, G., Palacios, M., & Patrinos, H. A. (2019). Measuring aversion to debt: An experiment among student loan candidates. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(1), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9601-8.

Chen, H., & Volpe, R. P. (1998). An analysis of personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 7(2), 107–128.

Chou, K. L., Chi, I., & Chow, N. W. (2004). Sources of income and depression in elderly Hong Kong Chinese: Mediating and moderating effects of social support and financial strain. Aging & Mental Health, 8(3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860410001669741.

Cloutier, J., & Roy, A. (2020). Consumer credit use of undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate students: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Consumer Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09447-8.

Deacon, R. E., & Firebaugh, F. M. (1988). Family resource management: Principles and application (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Dew, J. (2008). Themes and trends of journal of family and economic issues: A review of twenty years (1988–2007). Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(3), 496–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-008-9118-7.

Drentea, P., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2000). Over the limit: The association among health, race and debt. Social Science & Medicine, 50(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00298-1.

Dwyer, R. E., McCloud, L., & Hodson, R. (2012). Debt and graduation from American universities. Social Forces, 90(4), 1133–1155. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos072.

Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1086/209315.

Fan, L., & Chatterjee, S. (2019). Financial socialization, financial education, and student loan debt. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9589-0.

FINRA Investor Education Foundation. (2016). Financial capability in the United States: Report of findings from the 2015 National Financial Capability Study. Washington, DC: FINRA Investor Education Foundation. https://www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads/NFCS_2015_Report_Natl_Findings.pdf.

Fitzsimmons, V. S., Hira, T. K., Bauer, J. W., & Hafstrom, J. L. (1993). Financial management: Development of scales. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 14(3), 257–274.

Fletcher, C., Webster, J., Klepfer, K., & Fernandez, C. (2015). Above and beyond: What eight colleges are doing to improve student loan counseling. TG (Texas Guaranteed Student Loan Corporation). Research Report.

Giménez-Nadal, J. I., & Ortega, R. (2015). Time dedicated to family by university students: Differences by academic area in a case study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(1), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9399-y.

Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 644–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y.

Gutter, M., & Copur, Z. (2011). Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9255-2.

Hadar, L., Sood, S., & Fox, C. R. (2013). Subjective knowledge in consumer financial decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0518.

Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. A. (2017). The political economy of education, financial literacy, and the racial wealth gap. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Review, First Quarter. pp. 59–76. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.2017.59-76