Abstract

The article describes the background to, and implementation of, the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS) in South Africa from 2010 to 2014—an initiative aimed at system-wide instructional improvement in the Global South. Working in over 1000 underperforming primary schools in poor- and working-class communities, the government-led GPLMS combined scripted lesson plans, provision of quality learner materials and personalised instructional coaching to enable teachers to adopt more effective instructional practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the publication of the ground breaking studies of system-wide instructional change in the 1990s—in particular Earl et al. (2000) evaluation of the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies in England; and Elmore and Burney’s (1997) studies of New York City Community School District #2—the field of educational change has flourished. At the core of the new knowledge is the publication of case studies of education systems of various configurations—districts, cities, provinces, and whole countries—that have embarked on successful change journeys (Malone 2013; O’Day et al. 2011; Tucker 2011; Fullan and Boyle 2014; City et al. 2009). But while the field is now filled with studies on high-performing systems in the Global North (including a growing number of studies in the East, such as in Singapore and Shanghai), the knowledge base of system-wide instructional reform in low-performing systems in the Global South remains very limited. It is to this gap in the field that this paper is addressed.

In 2010, in response to the call of South Africa’s president to improve school literacy and mathematics outcomes, the provincial minister of education in the metropolitan province of Gauteng, centred around Johannesburg, took the bold—and, at the time unusual—step of prioritising primary education reform over a more visible and politically more popular focus on high schools. From 2010 to 2014, under the direction of the provincial minister, the provincial education department developed and implemented the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS). Despite its apparent successes, and its spin-offs, the strategy has received little attention from the international educational change community.

The article begins by providing information about the context and background to the system reform initiative, exploring the research on prevalent instructional practices. This is followed by a section that describes the scope, features, and theory of change of the GPLMS. The third section discusses the growing body of qualitative research on how teachers in South Africa have enacted and experienced this example of system reform. The fourth section summarises the evaluation research on the impact of the system reform on student outcomes. The paper concludes with an exploration of the contribution that the South African case makes to the wider field of educational change.

On the problem of positionality, Elmore (2010) described having made a shift in his academic work from research on policy and practice to research in the service of practice. In many respects, my own work has followed a similar trajectory. Over the past 6 years I have worked closely with policy makers and senior government officials on the GPLMS, and more recently in other provinces and at national level in South Africa, on the problem of system-wide change at the instructional core. The dilemma associated with the shift from research on policy to research in the service of practice is the challenge of impartiality—specifically the challenge of advancing the field of educational change—when scholars in this particular research community are insiders, essentially studying innovations or initiatives on which they have substantial influence. My own response to this dilemma is to move in my own research towards what is often referred to as the ‘gold standard’ of impact evaluation; namely counterfactual research and particularly the use of randomised control trials. While I recognised early on in the life of GPLMS that these methodologies would be difficult, I have made every effort to use powerful counterfactual empirical approaches to ground claims of efficiency and impact, but balance them with independent qualitative research findings.

Primary education in South Africa in crisis

In the years immediately following the first democratic elections in April 1994, South Africa’s school system, with over 10 million schoolchildren in Grades 1–12, 400,000 teachers and 22,000 schools, was in deep crisis (Shindler and Fleisch 2007). While much of the educational research community focused on the unequal distribution of resources along racial and geographic lines (Fiske and Ladd 2004), there was growing recognition of the near collapse of what became known as a ‘culture of teaching and learning’ (Jansen and Taylor 2003). Secondary schools in black working-class communities across the country had been the site of intensive political contestation during the 1980s and early 1990s, with young secondary school students often being described as the ‘foot soldiers of the revolution.’ The routines and rhythms of schooling in most urban working class communities (the very grammar of classroom life) had been ruptured (Christie 1998).

The first challenge of the newly elected government was to restructure the racially segregated administrative systems. The next step was to redress resource inequalities, institutionalise democratic school governance and transform the official curriculum (Fleisch 2002). The pace, complexity and magnitude of changes were unprecedented in the years from 1995 to 2005. While many of the reform initiatives began to impact positively on the system, others soon proved to be major failures—particularly in the curriculum policy field (Jansen 1998; Chisholm 2003).

A new dimension of the education crisis began to emerge during the mid-2000s. Along with other cross-national studies in which South Africa had begun to participate, the publication in 2006 of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) raised public and policy awareness of the problem of primary school literacy achievement. Unlike its more famous cousins, TIMSS and PISA, the PIRLS study focuses on reading performance of schoolchildren in Grades 4 and 5. The PIRLS results basically showed that, on average, South African schoolchildren had the worst scores among the 45 systems in the study. South Africa’s PIRLS median score was 283. The researchers heading up the team in South Africa, Howie et al. (2008) observed that the score fell far short of international average of 500 and was well below the closest two countries: Morocco at 335 and Kuwait at 342.

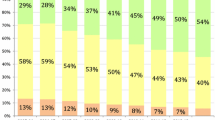

While the mean score provided a picture of where South Africa stood in relation to other countries, it provided little real information about the actual reading levels of South African children. To show reading levels, the PIRLS study used four benchmark literacy levels: low, intermediate, high, and advanced. To achieve the low benchmark, schoolchildren were expected to “recognise, locate and reproduce information that was explicitly stated in texts, especially if the information was placed at the beginning of the text”. Only 13 % of Grade 4 students and 22 % of Grade 5 students reached the minimum low benchmark. The remaining 87 % and 78 % of students in Grades 4 and 5 respectively, did not even reach the low level. In terms of performance across the 11 official languages, Grade 5 students who took the test in local African languages, such as isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sepedi, and Setswana, averaged in the low 200s.

The PIRLS results were largely confirmed a few years later in a Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) Grade 6 study. As a long-running cross-national study of student achievement, the SACMEQ programme provided not only a good benchmark of education in South Africa against that in neighbouring countries, but also a picture of the relative change in aggregate performance over time. The SACMEQ III (2007) provided a detailed breakdown of reading competency levels. This study found that 76 % of South African schoolchildren were reading at or below the basic level. Spaull (2011), who analysed the 2007 SACMEQ III dataset for South Africa, observed that

[g]iven that South Africa has more qualified teachers, lower pupil-teacher ratios and better access to resources, one would expect that South African students would perform at the top of the regional distribution. Unfortunately, this is not the case. In a league table of student performance, South Africa ranks 10th out of 15 SACMEQ countries for student reading […] [W]hen ranked by the performance of the poorest 25 % of students, South Africa ranks 15th out of 15 [...]. To put this in perspective, the average ‘poor’ South African student performs worse at reading than the average ‘poor’ Malawian or Mozambican student. This is in spite of the fact that the average ‘poor’ South African student is significantly wealthier than the average ‘poor’ Malawian and Mozambican student. (p. 24)

In the latest TIMSS study, Reddy and Prinsloo (2015) concluded that while mathematics performance in South Africa has improved over the past decade, the reality remains that three-quarters of South African students do not acquire even the minimum set of mathematics skills. The TIMSS report makes the argument that the shallow achievement of the majority of schoolchildren is cumulative—the mastery of the foundation of mathematics and language has not occurred in the early grades. This is a recurring theme in all of the main studies undertaken in South Africa (see Carnoy et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2013; National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU) 2014).

The link between underachievement and instructional practice

Given the activist approach adopted towards policy reform during South Africa’s democratic era, why did government’s multifaceted reform programme fail to help working-class and poor students thrive educationally? The answer lies, at least in part, in the failure of policy to get at the ‘instructional core’, understood as the relationship between teachers and students in the presence of content (City et al. 2009); to find levers that could penetrate deep into the classroom, to shift deep-rooted instructional practices. Growing evidence in South Africa (e.g. Jansen 2002; De Clercq 1997) has shown that policy reforms have little substantial impact on instructional practice. At best, such reforms tend to impact indirectly and weakly on schools, and only on the peripheral activities, such as governance.

A precondition for sustainable, system-wide, instructional reform is knowledge of prevailing instructional practices themselves. In other words, the nature of the instructional change problem must be better understood. A review of the rich qualitative research classroom case studies in South Africa reveals very powerful insights into prevalent practices in the teaching of reading and writing in the early grades. This research literature shows that despite policy having been in force for two decades, there remain two distinct systems of instructional practices in primary schools in South Africa. One of the two systems is evident in early-grade classrooms serving working-class, poor, and rural communities (see Macdonald 2002, 2006; Botha 2007; Place 2005; Pretorius and Mokhwesana 2009; Pretorius and Currin 2010; Reeves et al. 2008; Ganasi 2010; Mackie 2007; Maphumulo 2010; Maswanganye 2010; Taylor et al. 2013; Bizos 2009). While each classroom has its unique emotional tone, and resources vary from context to context, researchers consistently report observing early-grade teachers making frequent use of a narrow set of pedagogical techniques, such as choral recitation, and copying from the board onto worksheets. In Grades 1 and 2 in the nine African home languages, the teaching of reading focuses on drilling of the letter names, letter-sound relationships, and simple words, with little or no silent individual reading of extended texts for meaning. Researchers have observed that while Grade 3 teachers begin to introduce longer texts, reading is still predominantly done through the reading-aloud method, i.e. the teacher reads the text, either from the board, from a worksheet, or from a workbook, and the children repeat the words, phrases, or sentences. A few individual ‘clevers’ are selected as the proxy readers for the read-aloud tasks, while the majority of students remain passive. The researchers consistently report systems of instruction in schools in poor communities defined by low expectations, narrow repertoires of pedagogical techniques, slow-paced lessons, incomplete coverage of the curriculum, and arbitrary sequencing (Fleisch 2008; Taylor et al. 2013).

A distinctly different system of instruction has been reported in schools that enrol middle-class children, both white and black. Teachers in these schools generally have high expectations of students and make use of sophisticated reading resources, such as basal reader schemes and commercial phonics programmes. Students have access to special learning spaces such as book corners and school libraries (Gains 2010; Dixon 2010; Kruizinga 2010). Daily use of the basal readers, such as the Ginn Series, was often the core around which reading instruction was structured. In this system, teachers’ instructional practice was an effective blend of phonics, group guided reading, guided writing, and vocabulary development, which are precisely the skills that tend to be measured on the standardised tests.

What are the implications of the findings of this research? They show the links between the two systems of instruction and the bimodal pattern of student achievement. Children whose primary experience of early school literacy is limited to truncated learning letter names, collective chanting of texts, and copying as writing are (with few exceptions) unable to perform on standardised tests that presuppose an extensive vocabulary, reading fluency, and a relatively high level of text comprehension. Existing education policies in South Africa, governance and curriculum reform, school management training, and even just provision of workbooks, have little impact on weak systems of instruction.

Change knowledge that informed the GPLMS

Given the limitations of much of education policy reform in impacting on the instructional core, and findings regarding the weaknesses of prevailing systems of early-grade reading and mathematics instruction in poor schools, the challenge in designing the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy was to identify the right combination of levers to get deep into instruction in thousands of classrooms. Fortunately, there was a growing body of change research to draw upon. One of the major shifts that have taken place in the field of education policy/educational change is the recognition that conventional input–output models for policy development are problematic (Cohen et al. 2003; Raudenbush 2005). Resources in the learning space, in and of themselves, do not enable improved learning at-scale; rather, it is how resources are mobilised that counts. This is a rather abstract idea, but it has substantial implications for conceptualising changing instructional practices. It signals the need for an in-depth understanding of prevailing systems of instruction and the factors in the immediate field that reproduce them.

Raudenbush’s (2005) provocative suggestion is that only new evidenced-based ‘instructional regimes’ have the potential to rupture entrenched systems of instruction. In his argument, rigorous compliance helps to institutionalise new systems of instruction, and, in so doing, improves learning outcomes. This idea is not new, and there is a long tradition of critique of change via externally developed programmes; from the earliest work in the field (see Sarason 1966) to more current analyses (see Hargreaves’ (2003) analysis of performance training sects).

There is a long-established finding regarding the centrality of alignment and coherence in changes to systems of instruction. Cohen and Spillane (1993) distinguish between education policies in general, and education policies that have the potential to influence—and ultimately change—systems of instruction in classrooms, or what Cohen (2011) has recently referred to as the ‘instructional infrastructure’. For Cohen, instructional infrastructure includes curriculum policy frameworks, external assessment of student performance, provision of learning materials, monitoring of classroom instruction, and policy requirements for teacher education and licensure. While governments make education policies to regularise other aspects of education, Cohen and Spillane argue that it is only policies that deal with instructional infrastructure that have the potential to contribute to change the instructional core. The relative success of policies that promote instructional change depends on the extent to which the policies are consistent—that is, the degree to which the various instructional policies not only speak to each other, but are internally aligned. Also, the degree of specificity, or prescriptiveness, is key. Instructional policies that have deliberately been designed to be vague—to allow for a wide variation of interpretation and adaptation—are less likely to drive rapid system-wide change. Tightly aligned instructional infrastructure that is highly prescriptive, i.e. clear and detailed, specifying the ‘what’, the ‘when’, and the ‘how’ of teaching, is more likely to act as levers in systems of instruction.

Alongside this insight there is a growing body of research that specifically explores scripted lesson plans (Beatty 2011), learning materials that help teachers learn new content (Ball and Cohen 1996), and new ways of enabling teacher development, such as coaching, which addresses both the learning of new practices and the complex emotional terrain associated with educational change (Gallucci et al. 2010).

One of the major contributions of the educational change knowledge has been the research on England’s National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies (NLNS). This includes Barber’s (2008) insights into the fusing of a high-challenge, high-support approach with five key components: ambitious standards, good data and clear targets, prescribed lesson plans, quality professional development, and accountability and intervention in inverse proportion to success; and Fullan’s (2010) persuasive argument that England’s success was at least in part attributable to the fact that they made use of an explicit theory of large-scale change.

Mourshed et al. (2010) study of how the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better began with the assumption that education systems are at different points in their respective ‘change journeys’, and that—depending on the stage—certain policy approaches would be more effective than others. Based on their cross-national research, they hypothesize that for education systems on the change journey from ‘poor’ to ‘fair’, (e.g. Minas Gerais in Brazil, and Madhya Pradesh in India), highly prescriptive interventions, such as mandated lessons plans, monitoring compliance through regular class visits, and performance targets based on universal external assessment, might work best. Mourshed et al.’s interviews suggest that many policy makers working in failing education systems more often than not adopt change approaches that have been developed in and for high-functioning education systems. These approaches often do not transfer effectively to structurally frail systems.

While change research is gaining traction, there is limited ‘gold-standard’ empirical evidence to support key hypotheses, particularly those that claim relevance to the Global South. While the number of studies that establish causal links between system-wide interventions and improved student outcomes has increased since Glewwe’s (2002) review, the number of published studies is small (McEwan 2013). In their literature review, Lucas et al. (2013) cited a number of interesting examples in the past 10 years. These include Banerjee et al. (2007) study of remedial tutoring for low-achieving students in India; He et al. (2008) Indian study of scripted lessons; and Friedman et al. (2010) and Piper and Medina’s (Piper and Korda 2011) work on structured lesson plans and in-service training. Most recently, Piper et al. (2014) have published positive findings of a randomised control trial (RCT) study that made use of scripted lessons, high-quality materials, and in-classroom (coaching) support in English and Kiswahili. Recently, Snilstveit et al. (2015) reviewed a larger group of studies that focus on access and learning outcomes in low and middle income countries. They found that structured pedagogy interventions as well as interventions with combined components are consistently associated with significant gains in learning outcomes.

The Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy

Drawing on the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies that came a decade before it, the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS), initiated in 2010, was explicitly grounded on change knowledge. The Strategy made use of multiple, overlapping, and mutually-reinforcing components of an instructional infrastructure, all of which were tightly aligned, both in terms of their emphasis on instructional practice, and in terms of the sequencing and pacing of the initiative’s roll-out. While the use of standardised student test results (Annual National Assessments) was seen as an important pillar of the Strategy, the key levers of the intervention were scripted lesson plans, the provision of quality learning materials, and instructional coaching. Although the provincial minister of education remained the patron and champion of the initiative, day-to-day leadership was undertaken by a transversal team of five managers: two permanent public servants and three contracted specialists; with the management located within provincial government. Save for a small contribution from McKinsey & Company, the entire initiative was paid for by the government.

The scripted daily lesson plans were delivered to all intervention teachers in the GPLMS. The emphasis of the lesson plans was on daily and weekly routines, with a strong emphasis on pacing and sequencing. The lesson plans were designed to enable teachers to cover the official curriculum within allocated time frames. The lesson plans were also designed to expand teachers’ pedagogic repertoire, particularly in early-grade reading and mathematics.

The GPLMS designers recognised that the scripted lesson plans alone would not—and, in fact, could not—shift instructional practice. The provision of quality learner materials, such as multilingual mathematics textbooks, vocabulary posters, Big Books for shared reading, word cards and word lists, and alphabet charts was a necessary condition for change. When a base-line evaluation found that the quality of the graded readers in African languages was inadequate, the province commissioned the development of linguistically sound graded reading series in eight African languages. Prior to the introduction of the GPLMS, although all schools received funds for the purchase of learner materials, most primary schools serving poor and working class students had inadequate book collections. None had proper reading schemes in the African languages. These instructional materials had never been produced by the local publishers because of the perceived cost and limited market (Koornhoff 2011; Katz 2014).

While the scripted lesson plans and the new learner materials were a necessary condition for the emergence of the new practice, a catalyst was needed to ensure that the lesson plans were enacted and the learner materials utilised. The catalyst was to be system-wide instructional coaching. The Gauteng Department of Education contracted outside not-for-profit service providers to hire and manage the instructional coaches. McKinsey and Company provided pro bono support for the design of the coach training. At the height of the intervention (at the end of 2013), over 500 coaches were working in the project. Most of these coaches had experience as primary school teachers, and some had worked in teacher education. They were paid the equivalent of a school Head of Department. For many of the schools in the province, teachers in Grades 4–7 were subject specialists, focusing on either English or mathematics. This meant that the second wave of coaches tended to be hired based on their subject specialisation rather than on phase (e.g. early-grade) expertise.

Coaches visited every teacher in the programme at least once a month and in many cases twice a month. During their visits they modelled the new practice, observed and commented on lessons, and examined students’ exercise books and assessment activities. In addition, the coaches also provided ‘just-in-time’ training to clusters of teachers, working through the scripted lesson plans a few days before they were due to be taught. They also helped to establish small ‘communities of practice’ for teachers that met every month after school.

The GPLMS intervention was first rolled out in 2011 in Grades 1–3 in the Home Language subject in 792 underperforming primary schools. The following year the programme was expanded to include Grades 1–7 and Home Language, English as First Additional Language, and mathematics across a slightly enlarged group of primary schools. In 2014, at the height of the programme, over 1040 schools in the provinces were directly involved in the Strategy. To address the backlog of students in the middle years (Grades 4–7) that had not benefited from the intervention from Grade 1, the GPLMS initiated an eleven-week catch-up programme that aimed at ‘re-teaching’ content that should have been mastered in the early year grades.

The GPLMS could be characterised as ‘materials-driven’. This is a fair assessment, given the high proportion of the budget that was spent on reading and mathematics schoolbooks. But the learner materials—particularly the graded readers developed in all of South Africa’s official indigenous languages, the phonics programmes, and the workbooks, (again in all the official languages), and the early-grade multilingual mathematics books—were designed as interlocking components of instructional infrastructure, intended to lever teachers to adopt the system of instruction.

Instructional coaching and just-in-time training were designed to contribute to the enactment of the lesson plans and use of the learner materials. Instructional coaching functioned both as a form of capacity building and as a form of professional accountability. Coaches came to classrooms for regular visits (once every 3 weeks) to model teaching of the lesson plans, and to provide supportive feedback to teachers based on lesson observations. The just-in-time training that took place with small clusters of schools offered teachers a wider perspective, as well as a theoretical understanding of the new instructional practice; and it addressed the knowledge gaps that teachers had as they prepared for future lessons. In the classroom the coaches modelled new pedagogical techniques and management skills, and they signalled to teachers something of the professional ethos associated with the new instructional practice. The coaching process allows teachers to begin learning from where they are, and it individualises their learning pathway. Following Gallucci et al. (2010), the change strategy came to recognise the need to develop consistency in coaching practice.

But while the emphasis of the coaching process is on learning from and alongside an expert in situ, (a process that has already demonstrated its usefulness in building trust), informal and unanticipated forms of internal accountability began to develop. In a system where teachers had in the previous two decades actively resisted classroom visits by district officials, the GPLMS coaches made over 120,000 successful visits in the first 3 years; experiencing almost no opposition from teacher unions. This suggests that the coaching process has gained the trust of teachers. The coaching visits de facto opened up the classroom to external scrutiny. Opening up of classrooms to outsiders and, by extension, the opening up of the actual new instructional practice to external appraisal has enhanced professional accountability across the system.

Evaluation of the impact of the reform

Did the GPLMS, and the model of system-wide instructional change, contribute to closing the achievement gap between disadvantaged and advantaged primary school students? Did the intervention raise the aggregate achievement level in the system? These evaluation questions are at the same time the most important and the most complex to answer, and are often questions around which a great deal of contestation emerges (for early critics of the GPLMS, see Janks 2014; Sayed et al. 2013).

The most common approach to evaluating the impact of the system-wide intervention is to measure the gains in key literacy and mathematics indicators on either national or international benchmarking assessment processes, or both. South Africa began its first round of universal primary school testing in 2011, and it has continued to test all primary school students every year since (with the exception of 2015). A simple comparison of aggregate system performance in Gauteng Province between 2011 and 2014 reveals a very steep upward trend. Inter-year comparisons are, however, not valid, as the test instruments changed over time (Department of Basic Education 2012, 2013). And while South Africa participates in two important international testing processes, namely PIRLS and SACMEQ, the long intervals between testing cycles and the time-lags in reporting the results make these measures equally unhelpful.

To address the question of the impact of the reform, a number of alternative approaches have been pursued. While inter-year comparisons of aggregate testing scores are not valid, intra-year comparisons of similar groups that received and did not receive the intervention offer the basis for more trustworthy findings. Although the research permit claims only about a local average treatment effects (LATE),Footnote 1 Fleisch and Schöer (2014) and Fleisch et al. (2016) show that the GPLMS model is having an impact of the magnitude of between .2 and .7 of a standard deviation. These studies made use of a ‘natural experiment’ approach that resulted from a miscalculation of the provincial systemic evaluation test scores in 2008, which had been used to assign schools to the GPLMS intervention. While not as effective as some of the interventions recently reported from Kenya (Piper et al. 2014), the recent impact evaluations certainly go some of the way towards demonstrating the effectiveness of the model in shifting systems of instruction.

Although the findings described above are robust, given the importance of this initiative and the change model that it represents, critics have raised concerns about generalisability of the findings, given the importance of context. To respond to this challenge a number of replication studies, using randomised control trial (RCT) methods, are currently underway or in the planning stages. The first of these RCTs, (based on a relatively small intervention component) was undertaken in KwaZulu-Natal (Fleisch et al. 2015). A more comprehensive 2-year trial of the GPLMS began in March 2015 in North West Province (Taylor 2015). A third RCT study, also in South Africa, focussing on English as First Additional Language, will begin in schools in 2017. The Kwazulu Natal study was a replication study of one component of the GPLMS—a catch-up programme for students in the middle years.

A growing group of qualitative researchers (e.g. De Clercq 2014; De Clercq and Shalem 2014; Masterson 2013; Molotsi 2015) provided insights into the dynamics and mechanisms of implementation and changes in teachers’ knowledge. This research reveals the nuances of teachers’ enactment with scripted lesson plans, the graded readers, multilingual mathematics materials, and the coaching process itself. In general, these researchers have found that rather than deskilling teachers, that is, separating planning from execution, teachers talked about how daily lesson plans allow them to learn new and more effective instructional practices, particularly when the lesson plans are mediated by coaches. Teachers also talk about the intensification of teaching work. Specifically from the perspective of teachers’ knowledge, De Clercq and Shalem (2014) research found that the intervention did not and could not address the deep-seated gaps in teachers’ content knowledge.

Conclusion

What has the Gauteng experience contributed to the research base of system-wide change at the instructional core? In large part, the Gauteng strategy drew heavily on extant knowledge in the field, making use of insights from the available literature. The experience of the past 5 years in the South African case largely confirms the hypothesis regarding the feasibility of system-wide instructional improvement in the short to medium term. As a school system, the Gauteng case joins a growing corpus of well-documented cases that show how strong political leadership can usher change across a vast network of underperforming schools.

Besides simply confirming the feasibility of system-wide change in the short to medium term in the Global South, the second contribution made by the South African case comes from an analysis of the generative mechanisms of change. The emphasis in the South African strategy was on a unique blend of prescriptive curriculum instruments with personalised instructional coaching. While internalisation of new, more powerful instructional routines associated with scripted lesson plans could be conceived of as simply bureaucratic compliance, teachers more often than not experienced the new routines as a form of professionalisation. At the same time, the personalised coaching—which rebuilt interpersonal trust—enabled the emergence of new forms of collective accountability.

With reference to the instructional core, the concern in the Global North is with increasing the proportion of schools that offer an ambitious curriculum, particularly those that serve working-class students. In the South African case, as is the case in much of the Global South, the challenge is to go from very weak teaching to systematic, structured and incremental instructional practice that affords the majority of students the opportunity to achieve reading, writing and mathematical proficiency. To do this, South African early-grade classrooms must improve key aspects of instruction, such as the pacing and sequencing of lessons, coverage of the curriculum, and repertoire of pedagogical techniques. The use of scripted lesson plans, tightly articulated with quality and appropriate learner materials, as well as teachers’ emotional and social learning via coaching, has facilitated the emergence of new, more effective instructional practices. The concept of ‘instructional core’ is useful in several contexts, not only in the context of systems struggling to upgrade to more ambitious instruction. The concept focuses attention towards those tasks or activities that are at the interface between teachers, resources, and students, and away from policy interventions that are removed from classroom life.

Postscript

in the past 2 years in South Africa, the change journey has taken a number of different directions. The provincial minister, due to her success, was promoted from the education portfolio to political head of provincial finance. A new provincial minister of education was appointed in the middle of 2014. He was appointed from the same party as the original political champion. The provincial minister identified a very different political ‘mandate’, and articulated a distinctly different political ideology, associated with what he referred to as the initiatives of his ‘legacy’. While he did not discontinue the GPLMS, the new political leader shifted government emphasis away from primary literacy and mathematics, (what some had seen as a ‘back-to-basics’ approach), and towards ICT in secondary schools, (what he referred to as the ‘schools of the future’). This significantly undermined the GPLMS initiative, as only a few top provincial managers are now devoting energy to the project. Following much of the literature, it is clear that leadership churn is one of the chief threats to the sustainability of change at the instructional core. As in all contexts, leadership continuity—not just compliance of the willing—is key to institutionalisation.

At the same time, there is increasing evidence that the GPLMS lesson plans are being photocopied and informally circulated and used by teachers in schools in other provinces. We became aware of this when planning a randomised control trial in a neighbouring province. Rural schools servicing the children of farm workers had copies of the GPLMS lesson plans, which had been circulated between teachers and between schools. Within the not-for-profit sector, a range of formal initiatives have taken up some, if not all, of the aspects of the system-wide reform model. This suggests that what was initially intended as state-directed change at the instructional core can have an unintended secondary spin-off. Informal networks of teachers have begun to enact a version of the new system of instruction, as they observe its positive benefits for their students.

Notes

The study results speak only to the impact of the intervention on a limited pool of the intervention schools and cannot be generalised to all schools that were part of the intervention. The study also focuses on only one indicator, Grade 3 mathematics. The study compared programme impact by comparing arbitrarily selected better-performing intervention schools to similar schools that were not part of the intervention.

References

Ball, D., & Cohen, D. K. (1996). Reform by the book: What is—Or might be—The role of curriculum materials in teacher learning and instructional reform? Educational Researchers, 25, 6–14.

Banerjee, A. V., Cole, S., Duflo, E., & Linden, L. (2007). Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1235–1264.

Barber, M. (2008). Instruction to deliver. London: Methuen.

Beatty, B. (2011). The dilemma of scripted instruction: Comparing teacher autonomy, fidelity, and resistance in the Froebelian kindergarten, Montessori, direct instruction, and success for all. Teachers College Record, 113(3), 395–430.

Bizos, E. N. (2009). Authoring lives: A case study of how grade 6 children in a South African township construct themselves as readers and writers. PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Botha, D. (2007). Early childhood literacy and emergent bilingualism: Vocabulary teaching and learning in one Soweto classroom. Honours thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Carnoy, M., Chisholm, L., & Chilisa, B. (2015). The low achievement trap: Comparing schooling in Botswana and South Africa. HSRC Press.

Chisholm, L. (2003). The state of curriculum reform in South Africa: The issue of Curriculum 2005. State of the nation. South Africa, 2004, 268–289.

Christie, P. (1998). Schools as (dis)organisations: The ‘breakdown of the culture of learning and teaching’ in South African schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3), 283–300.

City, E. A., Elmore, R. A., Fiarman, S., & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional rounds in education: A network approach to improving teaching and learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cohen, D. K. (2011). Teaching and its predicaments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cohen, D. K., Raudenbush, S. W., & Ball, D. L. (2003). Resources, instruction, and research. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25, 119–142.

Cohen, D. K., & Spillane, J. (1993). Policy and practice: The relations between governance and isntruction. In S. Fuhrman (Ed.), Designing coherent education policy: Improving the system. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

De Clercq, F. (1997). Policy intervention and power shifts: An evaluation of South Africa’s education restructuring policies. Journal of Education Policy, 12(3), 127–146.

De Clercq, F. (2014). Improving teachers’ practice in poorly performing primary schools: The trial of the GPLMS intervention in Gauteng. Education as Change, 18(2), 303–318.

De Clercq, F., & Shalem, Y. (2014). Teacher knowledge and employer-driven professional development: a critical analysis of the Gauteng Department of Education programmes. Southern African Review of Education with Education, 20, 129–147.

Department of Basic Education. (2012). Report on the annual national assessment of 2012. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education.

Department of Basic Education. (2013). Report on the annual national assessment of 2013. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education

Dixon, K. (2010). Literacy, power and the schooled body: Learning in time and space. New York: Routledge.

Earl, L., Fullan, M., Leithwood, K., & Watson, N. (2000). OISE/UT evaluation of the implementation of the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies. Summary: First annual report. Watching & learning. Annesley, UK: Department for Education and Skills.

Elmore, R. (2010). Institutions, improvement and practice. In A. Hargreaves & M. Fullan (Eds.), Change wars. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Elmore, R. F., & Burney, D. (1997). Investing in teacher learning: Staff development and instructional improvement in Community School District #2, New York City. New York: National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Fiske, E. B., & Ladd, H. F. (2004). Elusive equity: Education reform in post-apartheid South Africa. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Fleisch, B. (2002). Managing educational change: The state and school reform in South Africa. Johannesburg: Heinemann.

Fleisch, B. (2008). Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren underachieve in reading and mathematics. Cape Town: Juta.

Fleisch, B., & Schöer, V. (2014). Large-scale instructional reform in the Global South: Insights from the mid-point evaluation of the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy. South African Journal of Education, 34(3), 1–12.

Fleisch, B., Schöer, V., Roberts, G., & Thornton, A. (2016). System-wide improvement of early-grade mathematics: New evidence from the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy. International Journal of Educational Development, 49, 157–174.

Fleisch, B., Taylor, S., Schöer, V., & Mabogoane, T. (2015). A report of the findings of the impact evaluation of the Reading Catch-Up Programme. Manuscript with author.

Friedman, W., Gerard, F., & Ralaingita, W. (2010). International independent evaluation of the effectiveness of Institut pour l’Education Populaire’s ‘Read-Learn-Lead’ (RLL) program in Mali. Mid-term report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

Fullan, M. (2010). Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Educational Change, 10, 101–113.

Fullan, M., & Boyle, A. (2014). Big-city school reforms: Lessons from New York, Toronto and London. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gains, P. (2010). Learning about literacy: Teachers’ conceptualisations and enactments of early literacy pedagogy in South African Grade One classrooms. PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Gallucci, C., Van Lare, M. D., Yoon, I. H., & Boatright, B. (2010). Instructional coaching building theory about the role and organizational support for professional learning. American Educational Research Journal, 47(4), 919–963.

Ganasi, R. (2010). The reading experiences of Grade Four children. MEd research report, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Glewwe, P. (2002). Schools and skills in developing countries: Education policies and socioeconomic outcomes. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 436–482.

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the knowledge society: Education in the age of insecurity. New York: Teachers College Press.

He, F., Linden, L., & MacLeod, M. (2008). How to teach English in India: Testing the relative productivity of instruction methods within the Pratham English language education program. New York: Columbia University. Mimeographed document.

Howie, S., Venter, E., & Van Staden, S. (2008). The effect of multilingual policies on performance and progression in reading literacy in South African primary schools. Educational Research and Evaluation, 14(6), 551–560.

Janks, H. (2014). Globalisation, diversity, and education: A South African perspective. The Educational Forum, 78(1), 8–25.

Jansen, J. D. (1998). Curriculum reform in South Africa: A critical analysis of outcomes-based education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(3), 321–331.

Jansen, J. D. (2002). Political symbolism as policy craft: Explaining non-reform in South African education after apartheid. Journal of Education Policy, 17(2), 199–215.

Jansen, J., & Taylor, N. (2003). Educational change in South Africa 1994–2003: Case studies in large-scale education reform. (http://jet.org.za/publications/research/Jansen%20and%20Taylor_World%20Bank%20report.pdf)

Katz, J. (2014). Vula Bula: Basal Readers in African Languages. In Paper Presented at the South African Education Research Association Meeting. Durban.

Koornhoff, H. (2011). From conception to consumption: An examination of the intellectual process of producing textbooks for the Foundation Phase in South Africa. MEd, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Kruizinga, A. (2010). An evaluation of guided reading in three primary schools in the Western Cape. MA thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch.

Lucas, A. M., McEwan, P. J., Ngware, M., & Oketch, M. (2013). Improving early-grade literacy in East Africa: Experimental evidence from Kenya and Uganda (Unpublished manuscript).

Macdonald, C. (2002). Are children still swimming up the waterfall? A look at literacy development in the new curriculum. Language Matters, 33(1), 111–141.

Macdonald, C. (2006). The properties of mediated action in three different literacy contexts in South Africa. Theory and Psychology, 16(1), 51–80.

Mackie, J. M. (2007). Beyond learning to read: An evaluation of a short reading intervention in the Ilembe District of KwaZulu-Natal. MEd research report, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Malone, H. J. (Ed.). (2013). Leading educational change: Global issues, challenges, and lessons on whole-system reform. Teachers College Press.

Maphumulo, T. (2010). An exploration of how Grade 1 isiZulu teachers teach reading. MEd thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

Masterson, L. (2013). A case study of Foundation Phase teachers’ experiences of literacy coaching in the GPLMS programme. Doctoral dissertation.

Maswanganye, B. (2010). The teaching of First Additional Language reading in Grade 4 in selected schools in the Moretele Area Project Office. MEd thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria.

McEwan, P. J. (2013). Improving learning in primary schools of developing countries: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Unpublished manuscript, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA.

Molotsi, G. (2015). An exploration of teachers’ view and experiences toward the use of Gauteng Primary Literacy and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS) Lesson Plans with and without coaches. Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand.

Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. New York: McKinsey & Company.

National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU). (2014). National Report 2013: Teaching and learning in rural primary schools. Pretoria: NEEDU.

O’Day, J. A., Bitter, C. S., & Gomez, L. M. (2011). Education reform in New York City: Ambitious change in the nation’s most complex school system. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Piper, B., & Korda, M., (2011). EGRA Plus: Liberia. Program Evaluation Report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

Piper, B., Zuilkowski, S. S., & Mugenda, A. (2014). Improving reading outcomes in Kenya: First-year effects of the PRIMR Initiative. International Journal of Educational Development, 37, 11–21.

Place, J. (2005). The college book sack project in the Kwena Basin farm schools of Mpumalanga: A case study. PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Pretorius, E., & Currin, S. (2010). Do the rich get richer and the poor poorer? The effects of an intervention programme on reading in the home and school language in a high poverty multilingual context. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 67–76.

Pretorius, E., & Mokhwesana, M. (2009). Putting reading in Northern Sotho on track in the early years: Changing resources, expectations, and practices in a high poverty school. South African Journal of African Languages, 1, 54–73.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2005). Advancing educational policy by advancing research on instruction. American Educational Research Journal, 45, 206–230.

Reddy, V., & Prinsloo, C. H. (2015). The meaning and utility of TIMSS data for systemic and school change: highlights from TIMSS 2011: South Africa.

Reeves, C., Heugh, K., Prinsloo, C. H., Macdonald, C., Netshitangani, T., Alidou, H., et al. (2008). Evaluation of literacy teaching in primary schools in Limpopo. Polokwane: Limpopo Department of Education.

Sarason, S. B. (1966). The school culture and processes of change. College of Education, University of Maryland.

Sayed, Y., Alhawsawi, S., Mwale, S., & Van Niekerk, R. (2013). The state and education policy change in South Africa: Walking the tightrope between choice and equity. In D. Turner & H. Yolcu (Eds.), Neo-liberal educational reforms: A critical analysis. London: Routledge.

Shindler, J., & Fleisch, B. (2007). Schooling for all in South Africa: Closing the gap. International Review of Education, 53(2), 135–157.

Snilstveit, B, Stevenson, J, Phillips, D, Vojtkova, M, Gallagher, E, Schmidt, T, Jobse, H, Geelen, M, Pastorello, M, & Eyers, J. (2015). Interventions for improving learning outcomes and access to education in low—And middle—Income countries: A systematic review, 3ie Final Review. London: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

Spaull, N. (2011). A preliminary analysis of SACMEQ III South Africa S.E.W.P. 11/11. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch.

Taylor, S. (2015). Early grade reading study: Baseline data collection and year 1 activities. Manuscript with author.

Taylor, N., Van der Berg, S., & Mabogoane, T. (2013). Creating effective schools. Cape Town: Pearson.

Tucker, M. S. (2011). Surpassing Shanghai: An agenda for American education built on the world’s leading systems. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fleisch, B. System-wide improvement at the instructional core: Changing reading teaching in South Africa. J Educ Change 17, 437–451 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9282-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9282-8