Abstract

Within the United States, approximately 17% of marriages occur between spouses of different races and/or ethnicities, while 1 out of every 7 children born identify as multiracial. Research suggests that, compared with monoracial couples, multiracial couples are at increased risk for negative relationship outcomes including divorce or separation. Although little research explores why these disparities exist, we surmise that poorer relational outcomes in multiracial families may be the result of heightened conflict caused by a greater difference in partners’ values and beliefs. In an understudied sample of expectant couples working in low-wage jobs, we examine differences in partner gender ideology and parenting beliefs as possible mechanisms underlying differential outcomes in relationship quality among multiracial families. This study examines whether the relationship between couple’s racial and ethnic composition (i.e., same versus different racial/ethnic backgrounds) and relationship quality (conflict, love, satisfaction) is mediated by differences in parenting beliefs and gender ideology. It is hypothesized that one mechanism that explains poorer outcomes (i.e., more conflict, less love, less satisfaction) is greater cross-racial differences in parenting beliefs and gender ideologies. Results indicated that multiracial families have lower love and relationship satisfaction and greater partner differences in gender ideology beliefs, however, gender ideology did not mediate the relationship between couple type and relationship quality. Overall, this study highlights the need for more longitudinal research and the exploration of other mechanisms underlying the different relationship outcomes for monoracial and multiracial families like social support, religiosity, and multicultural values.

Highlights

-

This study examines mechanisms that may underly multiracial families increased risks for negative outcomes: parenting and gender ideology.

-

Results indicate multiracial families experience lower love and relationship satisfaction during the transition to parenthood.

-

Further, multiracial couples reported greater differences in parenting and gender ideologies compared to monoracial couples.

-

However, greater differences in parenting and gender ideology did not explain significant racial differences in relationship quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Within the U.S., the number of marriages involving partners from different racial and ethnic backgrounds has risen sharply over the past few decades (Lee & Bean 2010, Qian & Lichter 2011, Wang, 2012). In the 1980s, only about 3% of marriages were interracial, meaning partners were of different races (Wang, 2012), by 2017, approximately 17% of marriages were between spouses of different races and/or ethnicities (Livingston & Brown, 2017). Furthermore, outside of marriage, research points to the rise of multiracial families through childbirth; one in 7 infants are born to an interracial couple (Livingston, 2017).

Recent research indicates that biracial couples are more likely to separate and/or divorce in comparison to their same-race counterparts, yet little research has delved into the reasons why this disparity exists (Leslie & Letiecq, 2004, Rollins & Roy, 2019). Some speculate that the challenges partners face in negotiating different values and belief systems across different races and ethnicities may be one explanation (Rollins & Roy, 2019, Roy, James, Brown, Craft, & Mitchell, 2020). In the present study, we seek to address this question and explore how differing values related to gender and parenting roles may create unique challenges for biracial couples, challenges that hold more negative ramifications for their relationships compared to same-race partners. We examine these issues in a particularly critical transition point – the transition to parenthood – a time when gender roles and parenting values are first being negotiated within families.

Multiracial Couples

At the outset, it is important to define terminology when discussing couples comprised of partners from two different racial or ethnic backgrounds. A variety of different terms have been used to describe such couples such as: intermarriage (Yahirun, 2019), cross-cultural (Falicov, 1995), cross-national (Seto & Cavallaro, 2007), biracial (Rollins & Roy, 2019), interracial (Usita & Poulsen, 2003), mixed race (Bratter & Whitehead, 2018), and multiracial couples (Wilt, 2011). Racial and ethnic categories in the United States originated as a method of separating people; they are malleable categories “rooted in both macro and micro social processes, and… [have] structurally and culturally defined parameters” (Rockquemore & Brunsma, 2002).

Racial categories in the United States originated as a method of separating people based on privilege. While race plays an important role in our world—defining people’s experiences and opportunities—racial categories have no biological basis (Goodman, 2000). Within the United States census, race is categorized as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (IOM Institute of Medicine (2009), Telles, 2018).

Similarly, ethnicity is a socially constructed category used to separate individuals based on common national or cultural traditions. Historically, ethnic categories were used to separate people by skin color; for example, when first constructed, ethnicity included the terms white, black, yellow, red, and brown to be associated with people from European, African, Asian, Indigenous, and Hispanic backgrounds (Burton, Bonilla-Silva, Ray, Buckelew, & Freeman, 2010; Shih, Bonam, Sanchez, & Peck, 2007; Smedley & Smedley, 2005). Presently, the U.S. census uses ethnicity to demarcate individuals of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin from individuals of non-Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin (IOM Institute of Medicine (2009), Telles, 2018).

Given that both race and ethnicity are socially constructed, it may not be surprising that although the United States classifies ‘Hispanic’ as an ethnic category, about two thirds of Hispanic Americans consider it to be a racial category (Parker, Morin, Horowitz, Lopez, & Rohal, 2015). Thus, clarity about terms and language matters greatly. The present study uses the term “multiracial” to describe couples in which individuals identify with different racial and/or ethnic identities since not all people identify by their race (i.e., Hispanic individuals often identify only in terms of their ethnicity; Parker et al., 2015). The term “monoracial” describes couples in which the partners identify as the same race and/or ethnicity.

Research to date has demonstrated that multiracial couples are at a greater risk for several adverse relational outcomes compared to their monoracial counterparts. Specifically, researchers have found that multiracial couples experience higher rates of divorce/separation (Bratter & King, 2008, Hohmann-Marriott & Amato, 2008, Lehmiller and Agnew 2007, Zhang & Van Hook, 2009) and poorer health (Yu & Zhang, 2017). Researchers have found that after 10 years of marriage, interracial marriages have a 41% chance of disruption compared to a 31% chance of disruption among same-race marriages (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Similarly, utilizing a national representative data from over 23,000 participants, Zhang and Van Hook (2009) found that multiracial couples were 15–21% more likely to dissolve their relationships than same race couples. This is of importance in and of itself; further, individuals experiencing relationship dissolution or divorce report less happiness, more mental health issues, poorer health, and reduced standards of living as compared to stably married individuals (Amato, 2010, Fisher & Low, 2016, Raz-Yurovich (2013), Stack & Scourfield, 2015). These negative relationship outcomes are of increasing concern given the rising numbers of multiracial couples.

Theory Informing Research on Multiracial Couples

The Interracial Couples’ Life Transition Model (ICLT; Roy, James, Brown, Craft, & Mitchell, 2020), provides a useful framework for capturing how individual characteristics, couple characteristics and the broader social context can shape multiracial couples’ relationship in terms of both quality and stability. In a relationship, each partners’ life experiences as well as their individual traits (e.g., physical and mental health, substance abuse, personality), their family of origin, and sociocultural characteristics (e.g., age, education, income, occupation, class, race, and gender) influence couples’ interactions and their relationship satisfaction.

According to the ICLT model, in order to understand the increased risk for divorce or separation for multiracial couples, it is critical to understand the broader social contexts surrounding the couple. In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws forbade marriage between individuals of different races (specifically Black and White individuals); these laws were not declared unconstitutional until the Loving v. Virginia case in 1967 (Warren and Supreme Court of The United States (1967)). Multiracial relationships often face disapproval from loved ones and society at large in the form of discrimination and microaggressions for pursuing a relationship outside the social norm (Forrest-Bank & Cuellar, 2018, Roy et al., 2019). Further, the negative effects of racism can be exacerbated within multiracial couples when partners do not recognize or validate each other’s racialized experiences creating relationship strain or conflict (Roy, 2019). Multiracial couples’ experiences of discrimination and microaggressions may be one key factor contributing to their relational strain and, ultimately, their heightened risk for separation.

Unstandardized Associations Between Couple Type and Relational Outcomes. Conflict, love and satisfaction were measured at time 5, one year post birth. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 3 for more information. Married is a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating married, while 0 is single. Multiracial is also a dichotomous variable—1 indicated a multiracial couple while 0 indicated a monoracial couple. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines)

Unstandardized Associations Between Couple Type and Value Differences. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 4 for more information. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines)

a Unstandardized Associations Between Differences in Gender Ideology and Relational Outcomes. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 5 for more information. Married is a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating married, while 0 is single. Gender Ideology represents the difference in couples, mothers’ and fathers’, gender ideologies. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines). b Unstandardized Associations Between Differences in Maternal Strictness and Relational Outcomes. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 5 for more information. Married is a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating married, while 0 is single. Maternal Strictness represents the difference in couples reports of how strict their mother was growing up. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines). c Unstandardized Associations Between Differences in Paternal Strictness and Relational Outcomes. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 5 for more information. Married is a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating married, while 0 is single. Paternal Strictness represents the difference in couples reports of how strict their father was growing up. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines). d Unstandardized Associations Between Differences in Spoiling Beliefs and Relational Outcomes. All numbers represent the unstandardized coefficient; see Table 5 for more information. Married is a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating married, while 0 is single. Spoil is the difference in couples’ beliefs on spoiling children. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. (See solid lines)

Relationship Quality in Multiracial and Monoracial Couples

According to the ICLT framework, relationship quality within couples’ microsystems is shaped by larger systems of discrimination which can negatively affect satisfaction and stability. Many researchers have examined multiracial couples’ relationship quality as a precursor for their ultimate divorce and separation. Prior to separation or divorce, research has found that relationships decline in quality, both in terms of reduced satisfaction and increases in conflict (Birditt, Wan, Orbuch, & Antonucci, 2017, DeLongis, & Zwicker, 2017, Kanter, Lavner, Lannin, Hilgard, & Monk, 2021). The following section examines how unique aspects of relationship quality differ for monoracial and multiracial couples. Although research is clear that interracial relationships are, on average, of shorter duration and more likely to end in separation or divorce, the literature on the quality of interracial relationships is mixed (Toosi, Babbitt, Ambady, & Sommers, 2012).

Early research found no differences in relationship quality for multiracial and monoracial couples (Stevenson, 1995); and no differences in levels of secure and insecure couple attachments in multiracial couples compared to monoracial (Gaines et al., 1999). This suggests that although multiracial relationships may be more likely to end, the break up is not necessarily a result of being in a lower quality relationship. More recent findings with a college student sample showed that multiracial relationships are no more difficult to maintain than monoracial relationships. Troy, Lewis-Smith, and Laurenceau (2006) found no differences in the relational satisfaction, conflict style, coping, or attachment styles of individuals in multiracial versus monoracial relationships. More recently, in a sample of 232 couples between the ages of 19-35, Brooks, Ogolsky, and Monk (2018) found that multiracial couples reported significantly greater relationship satisfaction compared to monoracial couples. Furthermore, they found no differences in relationship investment by couple status (Brooks et al., 2018).

In contrast, other studies point to multiracial relationships as being of lower quality than monoracial couples. For example, some researchers reported that while interracial couples may have higher relationship quality than African-American couples, they experience lower relationship quality than White couples (Stringer, 1991). More recently, in a meta-analysis that included studies across a 40-year period using 108 samples (Toosi et al., 2012), it was found that monoracial couples reported higher quality relationships compared to multiracial couples. Specifically, monoracial dyads reported more positive attitudes about their partners, reported feeling less negative affect about their relationship, showed friendlier nonverbal behavior, and scored higher on a variety of performance measures compared to multiracial dyads (Toosi et al., 2012). Furthermore, some studies have connected multiracial couples’ poorer relationship stability (or higher likelihood of divorce) to their higher levels of relationship conflict (Chartier & Caetano, 2012).

One reason for the mixed findings on relationship quality may be because couple type, or the racial/ethnic match of the couple matters (i.e., Black-White, Latinx-Black). For example, Brown, Williams, & Durtschi (2019), utilizing data from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study, found that, on average, women in multiracial relationships were less satisfied compared to women in same race relationships. Further analyses revealed, however, that all multiracial relationships may not be equal. Of the six multiracial couple pairings evaluated (Black-White, White-Hispanic, Black-Hispanic, White- Asian, Black-Asian, and Hispanic-Asian), Black-Hispanic couples had the highest percentage of marital separations (Brown et al., 2019). This study highlights the importance of looking within interracial couples. While research suggests that on average interracial relationships are more likely to end in separation and divorce (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002, Zhang & Van Hook, 2009), this study shows that some couple pairings may be at a greater risk. However, a notable limitation of this study was its use of a single item measure of relationship quality. Relationships are complicated, and no one aspect of relationship quality tells the whole story. Thus, it is important to assess multiple domains of relationship quality, especially given the limited and conflicting knowledge on multiracial couples. Examining patterns of relationship quality among monoracial and multiracial couples/families has potential to inform education and intervention as well as providing groundwork for a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and strengths that multiracial families experience.

Transition to Parenthood as a Sensitive Period for Negotiating Partner Differences

The Interracial Couples’ Life Transition Model (ICLT, Roy et al., 2020) also recognizes the importance of the life phase of the couple, and specifically highlights the transition to parenthood as a critical time for relationships. Roy and colleagues assert that family roles, like parent and partner, are socially constructed and have different meanings for different individuals. Roles and role expectations are shaped by the cultural contexts (e.g., class, race, ethnicity) within which each person is raised. Thus, within all couples, but especially among multiracial relationships, it is of critical importance that partners navigate their differences and come to a consensus upon parental role expectations and responsibilities. This requires understanding of one another’s lived social-cultural experiences as well as awareness of how their identities interact and influence how they perceive the world and each other.

The importance of shared role consensus is further supported by the sociological principle of homogamy which posits that similarity in tastes, values, and worldviews enhances marital intimacy (Burleson and Denton, 1992, Clarkwest, 2007). Couples sharing similar heritages, backgrounds, characteristics, and belief systems have fewer misunderstandings and conflicts than couples of differing cultural backgrounds (Bratter & King, 2008, Zhang & Van Hook, 2009). Thus, the background differences of multiracial couples may be a unique source of relationship conflict and, ultimately, an antecedent of separation and divorce (Pasley, Kerpelman, and Guilbert, 2001, Zhang & Van Hook, 2009). In fact, there is substantial evidence to support the claim that similarity benefits marital stability and satisfaction (e.g., Larson and Holman, 1994). For instance, Clarkwest (2007) found that differences in partner attitudes toward fertility and domestic tasks was associated with higher divorce rates. Likewise, Gaunt (2006) showed that similarity in personality traits and values increased marital satisfaction. Qualitative work also provides evidence of within-couple differences in values and interests (e.g., differing gender-role beliefs); differences that may increase couple conflict which, in turn, may partially explain multiracial couples’ shorter relationship duration and higher propensity for divorce (Rollins & Roy, 2019, Roy, Mitchell, James, Miller, & Hutchinson, 2019).

Despite evidence that couple similarity “breeds” greater couple satisfaction and love, and dissimilarity leads to greater relationship challenges (Lemay Jr. & Ryan, 2020, Pasley et al., 2001), few studies have explored how differences that emerge between couples of different races and/or ethnicities around values and cultural traditions are related to relationship conflict (Hohmann-Marriott & Amato, 2008). A great deal of research, however, documents that there are racial/ethnic differences on a wide range of attitudes and values, especially regarding gender roles. For instance, research has found that Black men have more progressive attitudes than White men regarding women’s employment (Blair-Loy & DeHart, 2003; Ciabattari, 2001; England, Garcia-Beaulieu, & Ross, 2004; Kane, 1992); specifically, Black men are more likely to expect women to work than White men. Similarly, Orbuch and Eyster’s (1997) found African-American men to be more egalitarian in sex-role ideology than White men. This ideological difference translated into behavioral differences, with African-American husbands spending more time in stereotypically female housework activities than White husbands (Orbuch & Eyster, 1997). However, more recent research has found no evidence that married Black men devote more time to housework than White men (Sayer & Fine, 2011).

Sayer and Fine (2011) also found differences in gendered behaviors among women of different races and ethnicities as well; Latinx and Asian women did more cooking and cleaning than White or Black women. Their work suggests that the gender gap in housework was lowest for Blacks couples and highest for Latinx and Asian married couples. Focusing exclusively on Latinx families, the concept of machismo, defined as a ‘cult of exaggerated masculinity’ involving ‘the assertion of power and control over women, and over other men’ (Chant & Craske, 2003) reflects a more traditional gender ideology. In line with the machismo concept, research has found that Latino men are more conservative than White men when it comes to the division of labor within the household (Ciabattari, 2001). Similarly, Glass and Owen (2010) found that a greater sense of machismo was related to fathers doing less parenting work.

Turning toward interracial couples, Bolzendahl and Gubernskaya (2016) found that Latina women with White partners did less housework than those with Latino partners, and White women partnered with Black men spent less time on housework than those with White partners. Sayer and Fine (2011) found that Asian women with White partners spent less time on housework than those with Asian partners. In another study of gender ideology within interracial Black/White couples, Forry, Leslie, and Letiecq (2007) found that, overall, women reported more egalitarian ideologies than men. No significant differences in ideology were found by race—White women with Black partners reported similar results to Black women with White partners. In the current study we examine how couple-level differences in ideology differ across multiracial and monoracial couples and, in turn, it is expected these differences will predict couple relationship quality.

Similar to gender ideology, differences in parenting behaviors and beliefs have not been explicitly examined within multiracial couples, however, such differences can be a source of conflict for couples. For example, partners with different parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, permissive; Berg-Cross, 2001) may clash over child rearing practices, many of which are culturally influenced. That is, ample research documents differences in parenting across racial and ethnic groups, including methods of discipline, expectations about child behavior, demonstrations of affection, and roles of the parents (Jambunathan, Burts, & Pierce, 2000; Lam, 2011, Quah, 2003, Strom, Strom, & Beckert, 2008). Using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a nationally representative sample of over 8,000 White, Black and Hispanic youth, Mowen and Schroeder (2018) examined racial and ethnic differences in parenting styles. Mowen and Schroeder found that Hispanic mothers were more likely to be classified as authoritarian compared to Black and White mothers, while White mothers were more likely to be classified as permissive compared to Black and Hispanic mothers. Researchers have also found that Black families are more likely to be classified as authoritarian compared to White families (Baker & DeWyngaert, 2018, Schneider, & Schenck-Fontaine, 2021).

Researchers have not only found racial and ethnic differences in parenting practices but also around parents spoiling beliefs. Parents with high spoiling beliefs worry that responding quickly to the cries of an infant will make him/her too dependent on the parent and increase future crying (Burchinal, Skinner & Reznick, 2010, Leerkes et al., 2015). Generally, research suggests that more responsive parenting is associated with greater social emotional competence, better negative affect regulation, greater empathy, and prosocial responses (Brophy-Herb et al., 2011, Davidov & Grusec, 2006, Leerkes, Blankson, & O’Brien, 2009). However, researchers have found that many ethnic minority families, especially Black families, hold beliefs that emphasize discipline (strictness) and the avoidance of spoiling, Barnett, Shanahan, Deng, Haskett, & Cox, 2010, Burchinal et al., 2010, Deubel, Miller, Hernandez, Boyer, & Louis-Jacques, 2019). In fact, research suggests that these beliefs, particularly beliefs around strictness or authoritarian parenting, may be protective for Black families (Baker & DeWyngaert, 2018). Research also suggests that early childhood experiences of strict parenting is intergenerationally transmitted and influence how children come to parent their own children (Belsky, Conger, & Capaldi, 2009, Kerr, & Capaldi, 2019). Thus, due to the documented racial differences in parenting practices and experiences, multiracial couples may experience greater parental conflict as a result of their divergent parenting experiences and beliefs specifically around strictness and spoiling.

In sum, individuals from two different races or ethnicities may have different beliefs about marriage, parenting, and expectations for men and women’s roles across various life transitions (e.g., pregnancy, childbirth, and acquiring a home); these cultural differences may increase stress and conflict between partners in multiracial relationships (Rosenblatt, 2009). For multiracial couples in particular, the transition to parenthood may be a time when partners’ differing experiences, values, and expectations come in direct conflict. Multiracial couples may not agree, for example, on how to raise a child given their gender and race in society (Leslie & Young, 2015). Whereas these differing beliefs may be inconsequential and latent early in relationships, they may become fault lines as a couple contends with the reality of marriage, new parenthood and a long term partnership and may in part explain multiracial couples heightened risk for negative outcomes.

Current Study

Marriages or partnerships between individuals of different races and ethnicities can carry individual, couple, and systemic inequalities that affect relationship quality, relationship stability, and the likelihood of divorce (Killian, 2003, Roy et al., 2020). Research is clear that multiracial couples experience higher rates of divorce/separation (Bratter & King, 2008, Hohmann-Marriott & Amato, 2008, Lehmiller and Agnew 2007, Zhang & Van Hook, 2009). However, research on relationship quality among mono- and multiracial couples is mixed (Brown et al., 2019, Toosi et al., 2012). This may in part be due to prior studies limited definitions of relationship quality (Brown et al., 2019). Alternatively, another reason for the mixed results may be, in part, due to the fact that the couple type matters (Roy et al., 2020); different types of multiracial couples may have different experiences. The present study will address these two key gaps in the existent literature. First, we distinguish between and examine three dimensions of relationship quality—love, conflict, and satisfaction. The relationship quality literature distinguishes between positive (e.g., love, satisfaction) and negative (e.g., conflict) aspects of relationships and notes that relationships have dimensions of both. In the present study we evaluate relationship love, an indicator of how connected or attached a couple is to one another. In contrast, relationship satisfaction refers to how happy a couple is in their relationship, which may be unrelated to levels of love and/or conflict. Relationship conflict speaks to how much a couple disagrees or gets into arguments.

Further, the present study does not just evaluate relationship quality across multiracial and monoracial couples but also within multiracial couples—noting differences among couple types (e.g., White-Black, Black-Latinx, etc). Based on the ICLT framework, one aspect of multiracial couples’ relationships that may influence marital quality is the couple’s consensus on role expectations related to gender roles and parenting. The current study examines these issues within a group of low-income families experiencing the transition to parenthood and returning to low-wage jobs soon after the birth of a child, a group that has been understudied in the dual-earner literature. Because in the U.S. race and class are often confounded, the present study focuses on working families of lower income which allows us to look at variability in race and ethnicity while, essentially, controlling for social class differences. The current study teases apart how the match between race and ethnicity in a couple is related to different relational outcomes for multiracial couples compared to monoracial couples.

Research Question 1: Are there differences in partners’ relationship conflict, love, and satisfaction between monoracial and multiracial couples? We hypothesize that multiracial couples will report more conflict and less love and satisfaction compared to monoracial couples (Bratter & King, 2008, Kroeger & Williams, 2011, Zhang & Hook, 2009). Given the lack of studies looking at relationship quality within multiracial couples, exploratory analyses test for differences in relationship outcomes (love, satisfaction, and conflict) by couple type (i.e., Black-Latinx, White-Black, White-Latinx). We hypothesize that given the mixed literature on relationship quality in multiracial couples, differences will emerge within multiracial couples.

Although researchers have proposed hypotheses about why group-level differences exist between multiracial and monoracial couples, few studies investigate the reasons why multiracial families may be at higher risk for negative outcomes. Guided by the Interracial Couples’ Life Transition Model (ICLT, Roy et al., 2020), we seek to move beyond understanding that differences exist between multiracial and monoracial families and towards a better understanding of what factors explain those differences. Specifically, we examine both differences in gender ideology and parental beliefs as two mechanisms which may explain the different relational outcomes between monoracial and multiracial couples. Multiracial couples may find that they have greater differences in their parenting and gender-role beliefs which way undermine their relationship. For parental beliefs, we examine beliefs about spoiling children and parental strictness, two areas that have been shown to have racial and ethnic differences. Again, we examine these issues at a critical phase in the life course, during the transition to parenthood, when new couples are having to directly address both their parenting beliefs and values, as they learn to care for their new child, as well as gender-role beliefs as they negotiate the dramatic increases in household labor (e.g., laundry) and child care (e.g., feeding, dressing).

Research Question 2: Are there greater differences in parents’ gender role ideology and parenting beliefs in multiracial couples compared to monoracial couples? Gender Ideology: We hypothesize that multiracial families will have greater differences in their gender ideologies compared to monoracial families. A simple comparison of multiracial and monoracial families may mask differences across multiracial couples. Exploratory analyses test the hypothesis that Latinx-Black couples will have the greatest differences in gender roles since Latinx families tend to hold more traditional ideologies, while Black families are the least traditional compared to Latinx-White or White-Black couples (Dixon, Graber, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008). Parental Strictness: We hypothesize that multiracial couples will have greater differences in their beliefs on parental strictness compared to monoracial couples. However, research has found that Latino and Black families report stricter parenting beliefs and practices compared to Whites (Coll & Pachter, 2002). Our exploratory analyses test the hypothesis that multiracial couples with one White partner and one person of color (White-POC) will have greater differences in their beliefs of parental strictness compared to other multiracial couples (POC-POC). Lastly, Spoiling Beliefs: It is hypothesized that multiracial couples, specifically White-POC, will report greater differences in their beliefs about infant spoiling compared to monoracial couples.

Research Question 3: Are greater differences in couples’ gender ideology and parenting beliefs related to their relational outcomes (love, satisfaction, conflict)? We hypothesize that greater differences in both gender ideology and parenting beliefs will be related to higher reports of conflict, less love, and less satisfaction.

Research Question 4: Do partner differences in gender ideology and parenting beliefs mediate the relationship between couple type (i.e., multiracial vs. monoracial) and couples’ relational outcomes (love, satisfaction, conflict)? We hypothesize that multiracial couples will report greater differences in their gender ideology and parenting beliefs which will in turn be related to more conflict and less love and satisfaction. We anticipate that monoracial couples report fewer differences in their gender ideologies and parenting beliefs, which relate to better relational outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants were part of a larger longitudinal project examining the transition to parenthood among 207 working-class women and their partners, if present. Women were recruited during their third trimester of pregnancy from prenatal education classes, prenatal clinics, community centers, OB/GYN offices, and Women Infant and Children (WIC) offices in New England region of the United States. Expectant parents were included if they met the following criteria: (a) were in their third trimester of pregnancy, (b) were employed at least 20 hours per week and planned on returning to work within six months of the child’s birth, and (c) were “working” class defined by educational attainment of an Associate’s degree or less and employment in an unskilled or semiskilled occupation. This study focused on parental dyads; therefore, 55 single parents were excluded from the analysis because they did not have father data, resulting in a final sample of 152 dyads.

The sample was racially/ethnically diverse (Mothers: 39.5% White, 34.2% Latina, 20.4% Black, 5.9% Mixed/Multiracial; Fathers: 29.6% White, 34.9% Latino, 29.6% Black, 5.9% Mixed/Multiracial). 98 couples identified as monoracial (37.8% Mono-White, 35.7% Mono-Latinx, 26.5% Mono-Black) and 54 couples identified as multiracial. Within multiracial couples, 55.6% identified as White-POC indicating that one person in the couple identified as White and 44.4% of the multiracial couples identified as POC-POC meaning both individuals identified as a person of color. See Table 1 for demographic information.

Men’s average age was 28 years (SD = 6). Women’s average age was 26 (SD = 5). One way ANOVAs indicated that mothers in monoracial White couples were significantly older than mothers in monoracial Latinx relationships (F (4, 151) = 3.95, p = 0.005). Similarly, fathers in monoracial White relationships were significantly older than fathers in monoracial Latinx relationships (F (4, 118) = 4.42, p = 0.001).

At the time of recruitment, almost 20.4% of the couples (n = 31) were married, while 53.3% of couples were cohabitating, and the remaining 26.3% reported not living with their partner. One way ANOVAs indicated that monoracial White couples were significantly more likely to be married compared to all other couple types (F (4, 149) = 5.12, p = 0.001). On average, couples reported knowing each other for 44 months (SD = 45). However, results indicated that monoracial Black couples knew each other for significantly more time compared to monoracial Latinx and multiracial POC-POC couples (F (4, 148) = 2.53, p = 0.043). On average, couples reported living with 1 (SD = 1) child. However, monoracial White couples reported having significantly fewer children than POC-POC couples (F (4, 150) = 2.50, p = 0.045). See Table 1.

Since the original study was focused on low-income, working families, the sample was restricted to participants who had an associate’s degree or less. The majority of mothers (48.8%) and fathers (63.5%) held a high school or general equivalency diploma. While 38.8% of mothers had some type of vocational training or held a one- or two-year associate’s degree, only 15.4% of fathers attained the same level of educational. Finally, 12.4% of mothers and 21.1% of fathers held less than a high school degree. The median take-home family income was $37,610. Monoracial White couples reported significantly higher incomes compared to mono-Latinx, mono-Black, and multiracial POC-POC couples (F (4, 148) = 6.37, p < 0.001). On average, mothers reported working 33.50 (SD = 11.49) hours, while fathers worked 41.60 (SD = 16.14) hours. No significant differences emerged by couple type (Mother hours: F (4, 151) = 0.79, p = 0.537); Father hours: F (4, 112) = 0.98, p = 0.424).

Procedure

Data collection occurred between 2003 and 2009. Couples were interviewed separately in their homes by trained graduate students at five time points across the transition to parenthood. These timepoints were: (1) third trimester of pregnancy, (2) one month after the baby’s birth, but before the mother had returned to work, (3) one month after mothers returned to work fulltime, babies were 3-4 months old, on average, (4) six months postpartum, and (5) one year postpartum. For this study, couple values (parenting beliefs and gender ideology) were captured at time three, when parents had been back to work for about a month and the child was 3-4 months old, and relational outcomes (conflict, love, and satisfaction) were measured one year postpartum (time 5).

Measures

Demographics

At baseline, both parents reported demographic information, including their marital status, ethnic/racial identity, income, length of time with partner, and the number of children living in the household. Ethnoracial composition of each dyad was constructed using mothers and fathers reported racial or ethnic identity at baseline (third trimester). If their racial and ethnic identity was the same, the dyad was categorized as monoracial. If their racial and ethnic identity were not the same, they were categorized as multiracial.

Conflict

Relationship conflict was assessed using the conflict subscale of the Relationship Questionnaire (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). The conflict subscale (5 items) assessed how often parents argue and/or have negative interactions using a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all/never) to 9 (very much/very often). Psychometric properties of the Relationship Questionnaire have been tested elsewhere (Belsky, Lang, & Rovine, 1985) and been shown to be reliable. Cronbach’s α was 0.83 and 0.76 for mothers and fathers respectively.

Love

Relationship love was assessed using the love subscale of the Relationship Questionnaire (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). The love subscale (10 items) assesses the degree to which an individual reports love, belonging, and interdependence (closeness, attachment) with one’s partner. Respondents rated these feelings using a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all/never) to 9 (very much/very often). Psychometric properties of the Relationship Questionnaire have been tested elsewhere (Belsky, Lang, & Rovine, 1985) and been shown to be reliable. Cronbach’s α was 0.88 and 0.81 for mothers and fathers respectively.

Relationship satisfaction

Satisfaction was assessed using the Kansas Relationship Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1986). This questionnaire consists of 3 items which assessed how satisfied individuals were with their partnership/marriage using a 7-point Likert scale; 1 = extremely dissatisfied and 7 = extremely satisfied. Cronbach’s α was 0.98 and 0.96 for mothers and fathers respectively.

Parenting beliefs—spoiling

Parents were asked: “How long should/do you let your baby cry before you respond to him or her?”. Responses ranged from 0 minutes to 80 minutes. Previous research with this item by Barry, Smith, Deutsch, & Perry-Jenkins, (2011) has shown that parents’ response times are related to parents’ beliefs around spoiling. Specifically, short response times were related to the belief that infants cannot be spoiled, while longer response times were related to the belief that quick response times would spoil the baby. In the present study, longer wait times were indicative of stronger beliefs in child spoiling. A difference score was created by subtracting fathers’ response time from mothers’ response time then taking the absolute value (Leonhardt, Willoughby, Busby, Yorgason, & Holmes, 2018). Higher values represent greater differences in spoiling beliefs.

Parenting beliefs—strictness

Parents were asked two questions on parental strictness; “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = very lenient and 5 = very strict, tell me how lenient or strict your mother/father was in disciplining and raising you”. Past research has shown that childhood experience of parental strictness is intergenerationally transmitted. Specifically, children that experience harsh strict parenting are more likely to engage in the same parenting style with their children (Belsky et al., 2009, Kerr, & Capaldi, 2019). Thus, participants’ childhood experiences of strict parenting were used as a proxy for their own parenting beliefs around strictness. Separate scores were created to represent participants beliefs on maternal strictness and paternal strictness. Separate differences scores were then created for maternal strictness and paternal strictness respectively. For example, a maternal strictness difference score was created by subtracting men’s report of maternal strictness from women’s report of maternal strictness then taking the absolute value (Leonhardt et al., 2018). Higher values represent greater differences in strictness beliefs.

Gender ideology

Men’s and Women’s Roles Questionnaire (Spence & Helmreich, 1972; 1979) was used to access parents’ attitudes toward the roles of women in society. The questionnaire consists of 15 items which were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicated more traditional values. Cronbach’s α was 0.74 and 0.72 for mothers and fathers respectively. A difference score was created by subtracting fathers’ gender ideology from mothers’ and then taking the absolute value (Leonhardt et al., 2018). Higher values represent greater differences in couples gender ideology.

Analytic Plan

A series of structural equation models were used to test the hypothesized relationships between couple type, parenting/gender beliefs and relational outcomes in Mplus v.8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). To evaluate the absolute model fit for each model, we used recommended fit indices and guidelines suggested by Kline (2016). Models with RMSEA values < 0.08, SRMR < 0.10, and CFI > 0.90 were considered a close fit to the data, and non-significant model X2 statistics are considered a perfect fit to the data (Kline, 2016). Models used Full Information Maximum Likelihood to account for missing data.

Question 1

To examine the relationship between couple type (multiracial vs monoracial) and level of partner conflict, love, and satisfaction, we conducted a structural regression, enabling simultaneous testing of mothers’ and fathers’ relational outcomes in one model. The simultaneous testing of mothers’ and fathers’ outcomes allowed the model to account for dependency in dyadic data. This baseline model was then constrained; estimates for mother and father predictors were set to be equal. This approach compares a full model allowing for parent gender differences with a simpler nested model constraining parent gender effects to be equal across equations. A nonsignificant ∆χ2 was found (∆χ2 = 2.99, ∆df = 7, p = 0.886) indicating that the unconstrained model that allowed mothers and fathers paths to be freely estimated did not provide a significantly better fit to the data compared to the model which constrained parents to be equal. Although both mother and father relational outcomes were entered into each model, because the values were equal, tables only present one value for each outcome (conflict, love, and satisfaction).

Question 2

To examine the direct relationship between couple type (multiracial vs monoracial) and difference in gender ideology and parenting beliefs, a structural regression was run to simultaneously test each value difference (gender ideology, maternal strictness, paternal strictness, spoiling). Each value difference was unrelated to one another thus each of these covariations were set to 0.

Question 3

To examine the direct relationship between value differences (gender ideology, parenting beliefs) and relational outcomes, a structural regression was run for each difference (gender ideology, maternal strictness, paternal strictness, spoiling). Each model was then constrained to test for differences between parents. For each model, A nonsignificant ∆χ2 was found (Gender Ideology: ∆χ2 = 9.35, ∆df = 7, p = 0.228; Maternal Strictness: ∆χ2 = 4.65, ∆df = 7, p = 0.703; Paternal strictness: ∆χ2 = 8.31, ∆df = 7, p = 0.306; Spoil: ∆χ2 = 4.19, ∆df = 7, p = 0.757). For each value difference, the final model retained was the constrained model, which set mothers and fathers estimates to be equal.

Question 4

Finally, we examined whether value differences mediated the effects of couple type on relational outcomes. To test for mediation, we used a bootstrapping procedure in Mplus to assess indirect effects. This method is superior to traditional approaches to mediation (Baron & Kenny 1986, Sobel 1982) as it estimates direct and indirect effects simultaneously, does not assume a standard normal distribution when calculating the p-value for the indirect effect, and repeatedly samples the data to estimate the indirect effect (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). We used 10,000 resamples of the data, 0.05 alpha significance level, and examined bias corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals (95%) to adjust for any bias in the sampling distribution (Mackinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Full mediation is met if both the indirect effect is significantly different from zero (evidenced by the confidence interval not capturing zero) and the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is not significantly different from zero (p > 0.05).

Results

Descriptive Data

The means and standard deviations for the relational outcomes are presented in Table 2. We used repeated measures ANOVAs to test for differences in relational outcomes by partner/race and found no significant differences in relational outcomes by parent gender [conflict: F (1, 76) = 0.33, p = 0.570; love: F (1, 78) = 0.04, p = 0.846; satisfaction: F (1, 75) = 2.62, p = 0.110]. However, racial differences emerged between with respect to relationship satisfaction, such that Latino fathers reported significantly higher levels of satisfaction than White fathers [F (2, 69) = 3.61, p = 0.033]. See Table 2 for more information.

Repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to test for differences in gender and parenting ideologies across parents and race (see Table 2). A repeated measures ANOVA revealed that fathers reported significantly more traditional gender ideologies compared to mothers (F (1, 85) = 37.24, p < 0.001). Black fathers reported significantly more traditional gender ideologies compared to White fathers (F (2, 80) = 3.33, p = 0.041).

No significant differences emerged, between mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of maternal or paternal strictness results did reveal racial differences in parents experience of strictness. Black parents reported experiencing significantly higher rates of maternal strictness compared to White parents (Mothers: F (2, 146) = 6.45, p = 0.002; Fathers: F (2, 104) = 3.65, p = 0.029). While, Latino mothers reported experiencing significantly higher rates of paternal strictness compared to White or Black mothers (F (2, 115) = 3.28, p = 0.041).

In regards to spoiling, a repeated measure ANOVA revealed that mothers waited significantly less time to respond to children compared to fathers (F (1, 97) = 60.00, p < 0.001). No significant racial differences emerged for beliefs about child spoiling.

RQ1: Relational Outcomes in Multiracial and Monoracial Couples

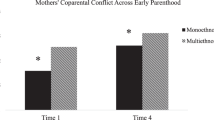

Research question 1 (model 1) examined parents’ relational outcomes at time 5 (one year postpartum) by couple racial match (monoracial or multiracial). We hypothesized that multiracial couples will report more negative relational outcomes (less love, less satisfaction and more conflict) compared to monoracial couples. The model tested marital status, income, and number of children as covariates. Income was unrelated to all couple outcomes and thus excluded to preserve power. Similarly, number of children was not significantly related to love and marital status was not significantly related to relationship satisfaction. Both were excluded from their respective models. Based on Kline (2016) model fit parameters, model 1 was a good fit to the data (χ2 (19) = 30.46, p = 0.046; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.07). Results indicated partial support for the hypotheses that multiracial couples will report more negative relational outcomes (less love, less satisfaction and more conflict) compared to monoracial couples (see Table 3; Fig. 1).

Conflict

Contrary to our hypothesis, no significant differences emerged between multiracial and monoracial parents in terms of relationship conflict, controlling for marital status and number of children (b = 0.18, SE = 0.25, p = 0.473). Additionally, results indicated that married couples reported higher rates of conflict (b = 0.41, SE = 0.15, p = 0.008) while couples with more children reported lower rates of conflict (b = −0.21, SE = 0.10, p = 0.003).

Love

As hypothesized, multiracial couples reported significantly lower levels of love compared to monoracial couples controlling for marital status (b = −0.56, SE = 0.18, p = 0.002). Married couples also tended to have higher ratings of love (b = 0.20, SE = 0.09, p = 0.021).

Satisfaction

Controlling for number of children, multiracial couples reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction compared to monoracial couples (b = −1.57, SE = 0.57, p = 0.006). Having more children was also related to higher reports of relationship satisfaction (b = 0.33, SE = 0.16, p = 0.035).

Exploratory results examined differences within multiracial couples. Results indicated significant differences between multiracial couples in which both individuals held minority identities (i.e., Latinx-Black multiracial couples) and multiracial couples in which one person identified as White. Specifically, results found that parents in multiracial relationships in which one person was white and the other identified as a person of color (White-POC) reported significantly lower levels of love compared to monoracial couples (b = −0.60, SE = 0.22, p = 0.007). Similarly, POC-POC multiracial couples reported significantly lower levels of relationship satisfaction compared to monoracial couples (b = −1.76, SE = 0.73, p = 0.015). No significant results emerged for conflict.

RQ2: Differences in Gender and Parenting Ideologies

Research question 2 (model 2) examined differences in parents’ gender ideology and parenting beliefs by couple type (monoracial or multiracial). We hypothesized that multiracial couples will report greater differences in gender and parenting ideologies compared to monoracial couples. The model tested marital status, income, and number of children as control variables. Only number of children was related to gender ideology—thus all other covariates were excluded to preserve power. Based on Kline (2016) model fit parameters, model 2 was a good fit to the data (χ2 (8) = 5.88, p = 0.661; RMSEA < 0.001; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.05). Overall, results indicated partial support for the hypotheses that multiracial couples will report greater differences in gender and parenting ideologies compared to monoracial couples. See Table 4 (Fig. 2) for full model statistics.

Gender ideology

As hypothesized, multiracial couples reported greater differences in gender ideologies compared to monoracial couples (b = 0.18, SE = 0.07, p = 0.007). Additionally, couples with more children tended to report fewer differences in their gender ideologies (b = −0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.010).

Parenting ideology

No differences emerged for parental strictness (Maternal: b = 0.14, SE = 0.16, p = 0.370; Paternal: b = 0.01, SE = 0.22, p = 0.952). or spoiling (b = −0.90, SE = 1.24, p = 0.466).

Exploratory results explored differences within multiracial couples. Results indicated that both POC-POC couples and White-POC couples reported significantly more differences in their gender ideology compared to monoracial White couples (POC-POC: b = 0.20, SE = 0.10, p = 0.049; White-POC: b = 0.18, SE = 0.09, p = 0.034).

RQ3: Value Differences and Relational Outcomes

Research question 3 (model 3) examined the relationship between couples’ differences in gender ideology and parenting ideology and relational outcomes (conflict, love, and satisfaction). We hypothesized that greater differences in cultural beliefs would be related to poorer relational outcomes (less love, less satisfaction, and more conflict). The model included marital status and number of children as control variables. number of kids was unrelated to love while marital status was unrelated to satisfaction. Both were excluded from their respective models to preserve power. Each model provided an adequate fit to the data based on Kline (2016) model fit criteria (See Table 5, Fig. 3; Gender Ideology = Model 3 A: χ2 (17) = 33.69, p = 0.009; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.07; Maternal strictness: χ2 (17) = 27.26, p = 0.054; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.07; Paternal strictness: χ2 (19) = 32.60, p = 0.027; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.09; Spoiling: χ2 (17) = 35.12, p = 0.006; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.94; SRMR = 0.07). Overall, results indicated partial support for the hypotheses that greater differences in cultural beliefs are related to poorer relational outcomes.

Gender ideology

A non-significant trend level effect suggests that greater differences in couples gender ideology was related to lower reports of love for mothers and fathers (b = −0.59, SE = 0.33, p = 0.071). No significant results emerged for conflict or satisfaction.

Parental strictness

No significant results emerged for couples reports of differences in their experiences of strict mothering. However, a trend level effect emerged for paternal strictness and conflict. Controlling for marital status and number of children, greater differences in couples experience of strict fathers was related to lower reports of conflict for mothers and fathers (b = −0.28, SE = 0.16, p = 0.075). No significant results emerged for love or satisfaction.

Spoiling

No significant results emerged. Controlling for number of children, greater differences in spoiling was related to parents’ lower satisfaction at the level of a trend (b = −0.06, SE = 0.04, p = 0.082). Spoiling was not significantly related to love or conflict.

Differences in Gender Ideology and Parenting Ideology as a Mediator

Model 4 examined whether value differences mediated the relationship between couple type (monoracial vs monoracial) and couple relationship outcomes. Overall, no support for mediation was found.

Gender ideology

Differences in gender ideology did not significantly mediate the relationship between couple type and relational outcome (Love: b = −0.08, 95% CI = [−0.30, 0.02], p = 0.293; Conflict: b = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.08, 0.38], p = 0.576; Satisfaction: b = −0.07, 95% CI = [−0.61, 0.32], p = 0.760.

Parental strictness

Differences in experiences of maternal strictness did not significantly mediate the relationship between couple type and relational outcome (Love: b = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.11], p = 0.929; Conflict: b = −0.03, 95% CI = [−0.23, 0.05], p = 0.688; Satisfaction: b = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.17, 0.33], p = 0.933.

Differences in experiences of paternal strictness also did not significantly mediate the relationship between couple type and relational outcome (Love: b = −0.01, 95% CI = [−0.13, 0.06], p = 0.930; Conflict: b = −0.02, 95% CI = [−0.19, 0.16], p = 0.859; Satisfaction: b = −0.01, 95% CI = [−0.37, 0.19], p = 0.941.

Spoiling

Differences in spoiling did not significantly mediate the relationship between couple type and relational outcome (Love: b = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.04], p = 0.512; Conflict: b = −0.03, 95% CI = [−0.12, 0.14], p = 0.668; Satisfaction: b = −0.07, 95% CI = [−0.14, 0.25], p = 0.491.

Discussion

The current study examined relational outcomes across the transition to parenthood in a sample of multiracial and monoracial families, as well as how partner differences in parenting beliefs and gender ideology might mediate this relationship. With the focus of the present study on families of low income, results focus on a group of parents who face noteworthy financial stressors and poorer work conditions, placing them at increased risk for early conflict and relationship discord compared to their more affluent middle class counterparts (Perry-Jenkins & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2019). Results indicated that multiracial couples experienced less love and satisfaction in their relationships. However, while multiracial families reported greater differences in their gender ideologies, this did not explain their increased risk for lower relationship quality.

Direct Effects of Couple Type on Relational Outcome

Consistent with our hypothesis and extant literature, parents in multiracial families reported lower levels of relationship satisfaction and love compared to individuals in monoracial families (Brown et al., 2019; Toosi et al., 2012). However, contrary to our hypothesis and past research suggesting that multiracial families will experience more conflict, results did not find differences in conflict (Chartier & Caetano, 2012). The results showing multiracial couples report less love and warmth, suggesting that future research examining why multiracial couples experience greater dissolution should focus on the lack of positive relationship assets as opposed to only the presence of conflict.

Furthermore, our findings expand on past research which points to different susceptibilities within multiracial families (Brown et al., 2019). Specifically, when exploring relational outcomes within subtypes of multiracial couples, couples in which one person identified as a person of color and the other being White (White-POC) may be at greater risk for experiencing lower levels of love compared to monoracial couples. While couples in which both individuals identified as people of color (POC-POC) may experience increased risk of lower relationship satisfaction. The different results in love and satisfaction may highlight the unique experiences of multiracial families. Given the small sample sizes, we cannot extrapolate the meaning behind these finds but this is a signal that love and satisfaction may play out differently in different couple types. Further research within multiracial families is needed.

Direct Effect of Couple Type on Family Values

Results were only partially consistent with the hypothesis that multiracial couples would report greater differences in their gender ideology and parenting beliefs. Couple type was related to differences in gender ideology, such that multiracial couples had greater differences than monoracial couples, findings that are consistent with previous research (Rollins & Roy, 2019; Roy, Mitchell, James, Miller, & Hutchinson, 2019). In fact, these results were consistent across different multiracial couples. Both White-POC and POC-POC couples reported greater differences in their gender ideologies than monoracial couples.

We found no differences in parenting beliefs (strictness and spoiling) by couple type. One reason why multiracial couples may not have reported greater differences in their parenting ideologies may be due to timing issues. Specifically, given that this study was conducted over the transition to parenthood and all couples were in the process of formulating their parent identity, both multiracial and monoracial couples may be equally as likely to report differences in their parenting ideologies. Another explanation for the lack of findings may be related to our measures of parenting beliefs. A one item measure assessed partners’ childhood experiences of parental strictness which restricted our ability to capture whether parents’ experiences of strictness were acceptable or harmful. While past research suggests that current parenting beliefs are often reflective, or positively related to childhood parenting experiences (Belsky et al., 2009; Kerr, & Capaldi, 2019), it is also plausible that as a result of negative childhood experiences, a parent may decide to enact parenting practices that are different from what they experienced. Ideally, future research would use a valid assessment of parents’ early experiences of discipline and, at a minimum, capture whether parents’ childhood experiences were viewed in a negative or positive way to understand their implications for current parenting beliefs.

Similarly, one reason results may not have emerged for spoiling beliefs may be due to how the construct was defined, which focused on how long a parent would wait before responding to a crying infant. While past research has shown that longer response times to infant distress were related to parental concerns of spoiling children (Barry, Smith, Deutsch, & Perry-Jenkins, 2011), we did not directly assess parents’ beliefs about spoiling. Additionally, it would have been useful to assess spoiling beliefs with a behavioral assessment. Future studies should continue to evaluate differences in parental behaviors and beliefs regarding spoiling as well as examine how these practices differ by race and ethnicity.

Direct Effect of Family Values on Relational Outcomes

Results provided signals that differences in parents’ gender ideologies and parenting beliefs are related to their relational outcomes. Trend effects revealed that greater differences in couples’ gender ideologies were related to less love, greater differences in experiences of paternal strictness were related to less couple conflict, and greater differences in spoiling beliefs were related to less satisfaction. These trend level effects point to the need for future studies to evaluate these hypotheses in a larger sample of multiracial families.

Another important consideration is social class. Because this study was conducted with a relatively homogeneous sample from a socioeconomic standpoint, there may be a restricted range of responding. It may be that differences in gender ideology and parenting beliefs are more reflective of class differences in couples that are diminished in our within-group analysis. Our findings cannot be extrapolated to more upper class families and future research should tease apart the role of social class as a possible moderator of these processes.

Alternatively, the relationship between differences in values and relational outcomes may be more complicated than the model specified. It may be that some couples value and welcome differences in gender ideology and parenting beliefs and work to respect and learn from differences (Yodanis, Lauer, & Ota, 2012). In this scenario, greater differences in values would be related to better relational outcomes (less conflict, more love, more satisfaction). In couples where differing values are viewed as problematic, or the couple is not able to successfully negotiate them, differences in gender ideology and parenting beliefs may relate to poorer relationship outcomes. Future studies should consider including measures of multiculturalism, namely the extent to which a family values and honors multiculturalism or diversity as a possible moderator of the connection between couple type and relationship quality. For example, if a couple chooses a partner of a different race and/or ethnicity because they value and respect cultural differences and diversity, these values could predict stronger relationship quality. This approach would reflect a strengths-based approach.

Value Differences as a Mediator

While this study found that couple type (monoracial, multiracial) was related to differences in couples’ values and differences in their relational outcomes, differences in values did not mediate the relationship between couple type and relationship quality. There may be a few reasons why significant differences did not emerge. First this study may have been under powered to find significance. Second, while this mediational process may occur, it may be dependent on a couples’ value of multiculturalism. As explained above, the direction of the relation between differences in couples ‘beliefs and their relational outcomes may depend on how the couple values multiculturalism. It may be that multiracial families come together because they value differences thus, we might expect in this case, multiracial families report greater differences in values which is in turn related to better outcomes.

Limitations and Strengths

The small sample sizes of different types of multiracial couples in the present study prevented a full exploration of how values and beliefs differ across different types of multiracial couples. Future studies should recruit a large enough sample to look within monoracial couples as well as specific multiracial pairings such as Black-White and Latinx-Black. In addition, it may not just be the difference in gender ideology that matters but who holds which identity; for example, an egalitarian mother with a traditional father might be different from a traditional mother with an egalitarian father.

Additionally, this study does not address the possibility that the impact of value differences may depend on the couples’ value of multiculturalism. In the context of a family that values differences in ideas and opinions and sees differences as an opportunity to understand different points of view, differences in gender ideologies and parenting beliefs may have less of an impact on relationship outcomes. Future research should explore the role of multiculturalism in understanding mono and multiracial couples’ relational outcomes.

While the exploration of relational outcomes in the unique sample of expectant families working low-wage work is a significant strength of the current investigation, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this sample. As a transitional timepoint, the reforming and establishing of parenting beliefs and gender ideologies that may occur in the context of bringing a new child into the world may make this an unstable time to study gender ideology and parenting beliefs. It would have been helpful to know if these constructs changed over the course of parenthood. Similarly, as the transition to parenthood is a volatile time, it may be that differences in values do not explain couples’ differences in their relationship one year post birth, but rather, differences in values may explain how the relationships of mono and multiracial families change over time.

Lastly, given that data was only captured over the first year of parenthood, results were restricted to looking at relationship quality (love, satisfaction, and conflict). It would be helpful for future studies to look at multiracial couples over a longer period of time to assess relationship stability, or divorce/separation, in addition to relationship quality.

Conclusions and Implications

Overall, this study highlights the continued need for research to explore mechanisms underlying the different relationships between couple type, monoracial and multiracial, and relationship quality and stability. The fact that partner differences in gender ideology and parenting beliefs did not help to explain relationship quality suggests that there may be different mechanisms at work. For instance, future studies may want to explore social support given that multiracial couples may experience greater social disapproval and discrimination. Additionally, it may be important for research to study other cultural values outside of gender, like religion. Shared religious beliefs may by protective among multiracial families that face differences in other domains of their identity (West, Magee, Gordon, & Gullett, 2014). On the other hand, it may be that differences are not always construed as negative and in fact multiracial couples may embrace and value differences in their families (Yodanis, Lauer, & Ota, 2012). While multiracial families may face additional societal stressors like microaggression and discrimination, if multicultural couples believe in and value multiculturalism, this may change the course of their relationship.

The implications of this research point to the importance of being sensitive to the unique challenges multicultural couples may face as they enter into parenthood. Differing beliefs about gender roles and parenting that reflect parents own socialization may create greater couple dissent. Thus, practitioners and interventionists should help new parents reflect on their cultural beliefs about parental roles and parenting to support couples in negotiating potential trouble spots in negotiating their transition to parenthood.

References

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x.

Baker, L., & DeWyngaert, L. (2018). Academic Socialization in the Homes of Black and Latino Preschool Children: Research Findings and Future Directions. In Academic Socialization of Young Black and Latino Children (pp. 233–255). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04486-2_11.

Barnett, M. A., Shanahan, L., Deng, M., Haskett, M. E., & Cox, M. J. (2010). Independent and Interactive Contributions of Parenting Behaviors and Beliefs in the Prediction of Early Childhood Behavior Problems. Parenting, science and practice, 10(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190903014604.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Barry, A. A., Smith, J. Z., Deutsch, F. M., & Perry-Jenkins, M. (2011). Fathers’ involvement in child care and perceptions of parenting skill over the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Issues, 32(11), 1500–1521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11406229.

Bell, G. C., & Hastings, S. O. (2015). Exploring parental approval and disapproval for Black and White interracial couples. Journal of Social Issues, 71(4), 755–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12147.

Belsky, J., Conger, R., & Capaldi, D. M. (2009). The intergenerational transmission of parenting: introduction to the special section. Developmental psychology, 45(5), 1201. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016245.

Belsky, J., Lang, M. E., & Rovine, M. (1985). Stability and change in marriage across the transition to parenthood: A second study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 855–865. https://doi.org/10.2307/352329.

Berg-Cross, L. (2001). Couples Therapy: A Cornerstone Approach. Department of Psychology Faculty Publications. 16. https://dh.howard.edu/psych_fac/16.

Birditt, K. S., Wan, W. H., Orbuch, T. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (2017). The development of marital tension: Implications for divorce among married couples. Developmental Psychology, 53(10). 1995. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000379.

Blair-Loy, M., & DeHart, G. (2003). Family and career trajectories among African American female attorneys. Journal of Family Issues, 24(7), 908–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03255455.

Bolzendahl, C., & Gubernskaya, Z. (2016). Racial and ethnic homogamy and gendered time on core housework. Socius, 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023116676277.

Braiker, H. B., & Kelley, H. H. (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships. In R. L. Burgess & T. L. Huston (Eds.), Social exchange in developing relationships (pp. 135–168). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6522.

Bratter, J. L., & King, R. B. (2008). “But will it last?”: Marital instability among interracial and same‐race couples. Family Relations, 57(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00491.x.

Bratter, J. L., & Whitehead, E. M. (2018). Ties That Bind? Comparing Kin Support Availability for Mothers of Mixed‐Race and Monoracial Infants. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(4), 951–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12485.

Brooks, J. E., Ogolsky, B. G., & Monk, J. K. (2018). Commitment in interracial relationships: Dyadic and longitudinal tests of the investment model. Journal of Family Issues, 39(9), 2685–2708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18758343.

Brophy-Herb, H. E., Schiffman, R. F., Bocknek, E. L., Dupuis, S. B., Fitzgerald, H. E., Horodynski, M., Onaga, E., Van Egeren, L. A., & Hillaker, B. (2011). Toddlers’ social-emotional competence in the contexts of maternal emotion socialization and contingent responsive- ness in a low-income sample. Social Development, 20(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00570.x.

Brown, C. C., Williams, Z., & Durtschi, J. A. (2019). Trajectories of interracial heterosexual couples: A longitudinal analysis of relationship quality and separation. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(4), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12363.

Burchinal, M., Skinner, D., & Reznick, J. S. (2010). European American and African American mothers’ beliefs about parenting and disciplining infants: A mixed-method analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190903212604.

Burleson, B. R., & Denton, W. H. (1992). A new look at similarity and attraction in marriage: Similarities in social‐cognitive and communication skills as predictors of attraction and satisfaction. Communications Monographs, 59(3), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376269.

Burton, L. M., Bonilla‐Silva, E., Ray, V., Buckelew, R., & Hordge Freeman, E. (2010). Critical race theories, colorism, and the decade’s research on families of color. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 440–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00712.x.

Chant, S., & Craske, N. (2003). Gender and sexuality. Gender in Latin America, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press

Chartier, K. G., & Caetano, R. (2012). Intimate partner violence and alcohol problems in interethnic and intraethnic couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(9), 1780–1801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511430392.

Ciabattari, T. (2001). Changes in men’s conservative gender ideologies: Cohort and period influences. Gender and Society, 15(4), 574–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015004005.

Clarkwest, A. (2007). Spousal dissimilarity, race, and marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00397.x.

Coll, C. G., & Pachter, L. M. (2002). Ethnic and minority parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting (pp. 1–20). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x.

DeLongis, A., & Zwicker, A. (2017). Marital satisfaction and divorce in couples in stepfamilies. Current opinion in psychology, 13, 158–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.11.003.

Deubel, T. F., Miller, E. M., Hernandez, I., Boyer, M., & Louis-Jacques, A. (2019). Perceptions and practices of infant feeding among African American women. Ecology of food and nutrition, 58(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2019.1598977.

Dixon, S. V., Graber, J. A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). The roles of respect for parental authority and parenting practices in parent-child conflict among African American, Latino, and European American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.1.

England, P., Garcia-Beaulieu, C., & Ross, M. (2004). Women’s employment among blacks, whites, and three groups of Latinas: Do more privileged women have higher employment?. Gender & Society, 18(4), 494–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265632.

Falicov, C. J. (1995). Cross-cultural marriages. In N. S. Jacobson, & A. S. Gurman (Eds.), Clinical Handbook of Couples Therapy (pp. 231–246). New York: Guilford Press.

Fisher, H., & Low, H. (2016). Recovery from divorce: comparing high and low income couples. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 30(3), 338–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebw011.

Forrest-Bank, S. S., & Cuellar, M. J. (2018). The mediating effects of ethnic identity on the relationships between racial microaggression and psychological well-being. Social Work Research, 42(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svx023.

Forry, N. D., Leslie, L. A., & Letiecq, B. L. (2007). Marital quality in interracial relationships: The role of sex role ideology and perceived fairness. Journal of Family Issues, 28(12), 1538–1552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07304466.

Gaines, Jr, S. O., Granrose, C. S., Rios, D. I., Garcia, B. F., Youn, M. S. P., Farris, K. R., & Bledsoe, K. L. (1999). Patterns of attachment and responses to accommodative dilemmas among interethnic/interracial couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16(2), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407599162009.