Abstract

The purpose of this investigation was to examine the association between emotion regulation and adolescent adjustment and whether parent and peer factors moderated this link. The sample consisted of 206 families with 10–18-year-old adolescents from predominantly ethnic minority and low-income families. We assessed emotion regulation and antisocial behavior (via parent and adolescent reports); depressive symptoms were based on youth reports. In addition, we examined the following moderators: observed parent-adolescent relationship quality and youth reports of parental emotion coaching, peer prosocial behavior, and peer-youth openness. Findings indicated that emotion regulation was negatively and significantly related to adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Evidence for moderating effects was found for antisocial behavior but not depressive symptoms. Specifically, the link between youth emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was attenuated under high levels of parent-child relationship quality and peer prosocial behavior. Implications for emotion socialization among adolescents from low-income families are discussed.

Highlights

-

Investigated whether the link between adolescent emotion regulation and adjustment was moderated by parent and peer factors.

-

Evidence for moderation was found in the prediction of adolescent antisocial behavior but not depressive symptoms.

-

The link between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was attenuated under high levels of parent–youth relationship quality.

-

The association between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was attenuated under high levels of peer prosocial behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A number of studies have demonstrated the link between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms (e.g., Buckholdt et al. 2014; Criss et al. 2016a). While these links have been established in investigations using child and adolescent samples, less is understood about whether parent and peer characteristics and relationships moderate the link between emotion regulation and psychopathology during adolescence. The purpose of the current study was to determine whether adolescent emotion regulation was related to antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms when examined simultaneously. Further, we investigated whether this link was moderated by parent–youth and peer characteristics and relationships.

Links between Emotion Regulation and Adjustment Difficulties

Adolescence is highlighted by a number of developmental transformations (Steinberg et al. 2006; Steinberg and Morris 2001). In addition to the cognitive (e.g., abstract thinking) and social cognitive (e.g., perspective taking) changes (Selman 1980), adolescents experience physical and hormonal changes that influence how they view themselves and how others (e.g., parents, peers) perceive them (Steinberg et al. 2006). Adolescence is also characterized by frequent and intense negative emotions (Larson and Lampman-Petraitis 1989) which may be why there is dramatic rise in affective and behavioral disorders during this developmental period (Dahl 2004). Also, adolescence is characterized by advances in brain development (Paus 2009; Spear 2000). Because of these developmental transformations, adolescence is an ideal time to study the impact of emotional processes on psychopathology.

Emotion regulation has been defined as the process of modulating the form, intensity, duration, and occurrence of emotion-related physiological processes and internal feeling states as a means of accomplishing one’s goals (Eisenberg and Morris 2002). In other words, emotion regulation may reflect how adolescents influence their emotions and how they experience and express them (Gross 2014, 2015). Due to advances in cognitive and neurological development during adolescence (Steinberg et al. 2006), evidence from the literature has indicated that adolescents are better able to regulate their negative emotions and often use more advanced cognitive strategies in their attempts to self-regulate compared to younger children (e.g., Morris et al. 2007). In addition to the developmental changes in emotion regulation, researchers have found emotion regulation to be negatively and significantly related to adolescent adjustment difficulties, such as delinquency, antisocial behavior, and depression (Buckhold et al. 2014; Compas et al. 2017; Criss et al. 2016a; Yap et al. 2011). While the association between emotion regulation and adolescent psychopathology has been established by several research teams using different samples, researchers have speculated different possible reasons for this link. For example, some have speculated that children and adolescents who demonstrate low self-efficacy at dealing with negative emotions may withdraw from parents and peers and continue to experience feelings of negative affect and depressed mood (Buckholdt et al. 2014). Herts et al. (2012) added that these individuals may be more sensitive to hostile cues (e.g., hostile attribution error; Crick and Dodge 1994) that may lead them to lash out at others. It is also possible that the under-regulation of emotions may reflect a degree of impulsivity when experiencing emotions which can lead to risky and problematic behaviors (Buckholdt et al. 2014). Related to this perspective, engaging in risky, delinquent, or antisocial behavior may be one way of avoiding or escaping painful negative emotions (Cooper et al. 2003).

Parents and Peers as Moderating Effects

While adolescent emotion regulation has been linked to psychopathology, not all individuals with emotion regulatory deficiencies experience adjustment problems. Indeed, parents and peers may moderate the link between youth emotion regulation and adjustment difficulties. In particular, adolescents from low-income families may start puberty earlier than their peers (Ellis et al. 1999) which may be accompanied by intensive and negative emotions (Larson and Lampman-Petraitis 1989). Moreover, younger youth may lack sufficient competence in emotion regulation (Morris et al. 2007), perhaps due to immaturity in the prefrontal cortex, which does not fully mature until emerging adulthood (Willoughby et al. 2013). This discordance between heightened emotional arousal and neurological immaturity may create a significant vulnerability that is unique to adolescence (Steinberg et al. 2006). Thus, parents and peers may play an especially critical role in the lives of youth with poor emotion regulation.

In terms of specific parent and peer factors, it is possible that relationship qualities (e.g., emotion coaching, relationship quality) and characteristics (e.g., prosocial behavior) may afford critical benefits among adolescents with poor emotion regulation skills. Emotion coaching refers to parental socialization efforts in which the parent labels and discusses the emotion, is accepting of the emotion, and helps the child come up with ways to manage the emotion (Gottman et al. 1996; Morris et al. 2017). Moreover, this construct is similar to inductive discipline in that it can facilitate the internalizing of adaptive emotion regulatory strategies by focusing on how children’s negative emotions may impact other people as well as recommendations for effectively dealing with the negative emotions (Criss et al. 2016b). Relationship quality reflects the extent to which the parent and adolescent have a warm, supportive, and mutually responsive relationship (Criss et al. 2003). Both emotion coaching and relationship quality have been positively related to emotion regulation (e.g., high emotion regulation, low negative affect; Criss et al. 2016a, 2016b; Gottman et al. 1996) suggesting that these factors may serve as protective factors. This would be consistent with the findings from Alink et al. (2009) who reported that the association between emotion regulation and internalizing problems was attenuated among children in the secure relatedness group but not the insecure related group.

Based on previous research (e.g., Criss et al. 2017; Lansford et al. 2003), having positive peer relationships and positive peer role models may serve as protective factors among youth with poor emotion regulation skills. Given that previous research has demonstrated that supportive peer interactions (e.g., peer group affiliation; Lansford et al. 2003) served as buffers among at-risk adolescents, it is possible that positive peer relations may attenuate the link between adolescent emotion regulation and adjustment. Likewise, peer prosocial behavior (i.e., engaging in positive, empathetic, and helpful behaviors for the benefit of others; Eisenberg and Fabes 1998; Eisenberg et al. 2016) may be another important characteristic given that it has been found to be related to higher levels of emotion regulation (Cui et al. 2015). To the best of our knowledge, there has been little research examining whether peer characteristics moderate the link between emotion regulation and adolescent adjustment. Therefore, this study was conducted to address this gap in the literature.

Low-Income Families

Examining potential moderators in the link between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms may be particularly relevant among low-income families. For example, adolescents from these families may experience more chronic negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, fear) perhaps owing to early onset of puberty (Ellis et al. 1999) and exposure to community violence (Fite et al. 2010). Moreover, adolescents from low-income families are at risk for emotion-related difficulties (e.g., poor emotion regulation, externalizing and internalizing problems; Criss et al. 2016b; Steinberg et al. 2006). There also is evidence that the emotional climate of low-income families may be especially harsh and coercive (e.g., walking on eggshells, intrusive parenting; Consedine et al. 2012). Thus, it is critical to investigate moderators in the link between emotion regulation and adjustment difficult among low-income families.

Current Study

There were two major goals of the current investigation. First, we examined whether adolescent emotion regulation was significantly related to adolescent adjustment difficulties. The current investigation focused on antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms as these factors typically have been utilized as outcomes in the emotion regulation literature (Buckhold et al. 2014; Compas et al. 2017) and are cited as key indicators of adolescent mental health (Graber and Sontag 2009; Patterson et al. 1992). It was hypothesized that high levels of emotion regulation would be significantly related to low levels of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. For the second research goal, we investigated whether positive parent-adolescent relationship attributes (i.e., emotion coaching, relationship quality) and peer relationships (i.e., openness) and characteristics (i.e., peer prosocial behavior) moderated the link between adolescent emotion regulation and adjustment difficulties. It was expected that the link between emotion regulation and adolescent adjustment would be attenuated under high levels of the moderators.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 206 families with adolescents who participated in the Family and Youth Development Project (Criss et al. 2017), a study of the correlates of adolescent emotion regulation. Data were collected from both adolescents (Mage = 13.37 years, SD = 2.32, age range = 10–18 years; 51% female; 30.1% European American, 32.5% African American, 18.4% Latino American, 6.4% Native American, 12.6% other) and their primary caregivers (83.3% biological mothers, 10.7% biological fathers, 2% grandparents, 4% other). The sample was comprised of predominantly low-income (Median annual income = $40,000, SD = 34,179.28, range = 0–150,000; 25.4% of families living below poverty line) families with an average of 4.35 people living in each home and 38.7% headed by single parents.

Procedure

The participants were recruited in a Midwestern American city and surrounding areas via fliers distributed at public facilities, area schools, and local Boys and Girls Clubs. In addition, snowball sampling was utilized with participants giving fliers to their friends. We focused on the recruitment of male and female adolescents (ages 10–18 years) from predominantly low-income, single parent, and ethnic minority homes. We also recruited the adolescents’ biological mothers if she was the primary caregiver and available. At the beginning of the 2.5 h assessment at a university laboratory, the consent and assent (for participants 17 years and younger) forms were read and explained to the parent and youth. After answering questions, the research assistants had the parent and adolescent sign the respective forms. The parent and adolescent were given copies of their forms. During the consent process and throughout the laboratory assessment, the parent and adolescent were assured that their answers would be kept confidential. Next, the parent and teen each completed a series of questionnaires separately. After the questionnaires, the parent–youth dyad participated in a 6-min (digitally recorded) semi-structured conflict discussion task that was adapted from Conger and colleagues (Melby et al. 1998). During the task, the dyads were given cards containing their five most common disagreements, which were selected using parent and adolescent reports on the Conflict Frequency Questionnaire (35 items, e.g., clothing, chores; Melby et al. 1998). Each card listed the conflict topic (e.g., “What is the conflict that we have about clothing?”) and three questions about the conflict: (1) “Who is usually involved?” (2) “What usually happens?” and (3) “What can we do to resolve the problem?” The parents and adolescents were asked to discuss as many conflict cards (up to five) as they wanted. The parent and adolescent each received $60 compensation for their participation and were debriefed at the end of the study. This project was approved by the university IRB.

Measures: Youth Emotion Regulation

The youth emotion regulation factor was based on parent and youth reports using the Sadness and Anger Management Scales developed by Zeman et al. (2001, 2002). The scales have demonstrated adequate internal reliability and predictive validity (Zeman et al. 2002). The emotion regulation (e.g., “I stay calm and keep my cool when I’m feeling mad.” “When I am feeling sad, I control my crying and carrying on.”) scale contained eight items that were rated using a 3-point Likert scale (0 = “not true,” 1 = “somewhat true,” 2 = “very true”). Adolescent (α = 0.74, M = 1.44, SD = 0.43) and parent (α = 0.80, M = 1.04, SD = 0.42) reports of emotion regulation were each created by averaging the eight items. The final adolescent emotion regulation factor was created by averaging (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) the adolescent- and parent-reported scores.

Measures: Adolescent Adjustment Difficulties

Youth antisocial behavior

Parents and adolescents reported on the adolescents’ level of antisocial behavior using a questionnaire adapted from the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale (PBFS; Farrell et al. 1992, 2000). Each of the 35 items (e.g., “hit/slap,” “break a rule at home”) were rated using a 5-point scale (1 = “never” to 5 = “7 or more times”). Adequate internal consistency (αs = 0.87 and 0.88 for urban and rural samples, respectively) and predictive validity has been found for the scale (Farrell et al. 1992). The youth-reported (α = 0.92; M = 1.44, SD = 0.43) and parent-reported (α = 0.92; M = 1.48, SD = 0.43) adolescent antisocial behavior scores were each computed by averaging the 35 items. Youth antisocial behavior was created by averaging (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) the youth- and parent-reported scores.

Youth depressive symptoms

Using the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ; Angold et al. 1995), adolescents reported on their depressive symptoms. We used adolescent self-reports because research has shown that youth reports of depressive symptoms to be more accurate than measures using other informants, such as teachers and parents (Bowes et al. 2015). Moreover, there is evidence that adolescents are better informants of their subjective internal states compared to their parents (Kent et al. 1997). The MFQ has 33 items (e.g., “I felt I was no good anymore.” “I blamed myself for things that were not my fault.”) which were rated on a 3-item Likert scale (0 = “not true,” 1 = “sometimes,” 2 = “true”). Adequate reliability and predictive validity have been found for this instrument (Wood et al. 1995). The final youth depressive symptoms score (M = 12.24, SD = 11.03) was created by summing (α = 0.93) the 33 items.

Measures: Moderator Variables

Parental emotion coaching

Parental emotion coaching was based on youth reports on the Emotions as a Child Scales (EAC; Klimes-Dougan et al. 2001; Magai and O’Neal 1997). This instrument was developed to assess parental responses to children’s expression of negative emotions. Parental emotion coaching refers to the frequency with which the parent and youth discusses the adolescent’s daily negative emotions including strategies for appropriately dealing with the emotions. Adequate validity and reliability have been found for the EAC scales (Klimes-Dougan et al. 2007). In the current investigation, adolescents were asked to rate how typical their parents’ responses to their expression of emotion are using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all,” 3 = “sometimes,” 5 = “very much”). In the current investigation, parental emotion coaching was based on the combination of three sadness items (i.e., “Ask you about it.” “Help you deal with the issue.” “Comfort you.”) and three anger items (i.e., “Find out what made you angry.” “Understand why you were angry.” “Help you deal with the problem.”) for a total of six items. The parental emotion coaching factor was created by averaging (α = 0.88) the six items.

Parent–youth relationship quality

Using a 9-point Likert scale, trained observers rated parent–youth relationship quality during the parent–youth conflict discussion task using a scale adapted from Melby et al. (1998). The graduate student and advanced undergraduate student coders were trained during several sessions for six weeks. The coders were recruited mainly from students who worked as research assistants in the laboratory. Training involved learning and being quizzed on the codebook, watching short video clips of evidence, and coding full length parent-adolescent conflict discussion tasks. The coders passed the coding training and coded real videos once they reached 80% exact agreement with the trainer. Although the coders usually did not discuss their assigned videos with the trainer after training, they all met with the trainer every three weeks in which everyone coded 1–2 videos. The purpose of these “Avoid the Drift” meetings was to limit any possible drifting that might occur in coding after the training.

Evidence from the video was based on observed (i.e., what was seen in the videos) and reported (i.e., what the participant said happened) evidence of positive and supportive (e.g., warmth, reinforcement, humor/laugh, physical affection) and negative and unsupportive (e.g., hostility, yelling, belittling, interruptions) behaviors. Videos were viewed separately to code for parent-to-adolescent behaviors and for adolescent-to-parent behaviors. Low scores reflect an emotionally unsatisfying, unhappy, or weak relationship with little and no evidence of positive or supportive behaviors. Middle range scores signify families that demonstrate fairly equal amounts of positive and negative relationship evidence. High scores on this scale indicate a parent–youth dyad that exhibits emotionally satisfying, open, warm, and happy interactions with little or no evidence of negative behaviors. Coders provided a single rating for parent–youth relationship quality for each family. Adequate interrater reliability has been found for this scale in previous studies (Lansford et al. 2009). Approximately 20% of the tapes in the current study were coded by the reliability coder (who was the coding trainer). Interrater reliability for parent–youth relationship quality was in an acceptable range (via intraclass correlations: ρ = 0.71, p < 0.001).

Peer factors

The adolescents also were asked to complete questionnaires regarding their best friend. Most of the friends were female (51.1%) and were on average 13.55 years old (SD = 2.60). Moreover, the youth participants reported knowing their best friends for over three years (Mdn = 3.33, SD = 3.76). The adolescents first completed a survey assessing the frequency of their best friend’s prosocial behavior. Peer prosocial behavior reflects the extent to which the best friend engages in helpful, positive, and empathetic behaviors especially for the benefits of others. Using a three-point rating scale (ranging from 1 = not true to 3 = very true), peer prosocial behavior was based on five items (e.g., “My best friend is considerate of other people’s feelings.” “My best friend usually shares with others.”) from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman and Scott 1999). This scale has adequate reliability and validity (Goodman 2001). The peer prosocial behavior factor (M = 3.57, SD = 1.05) was created in the current study by averaging (α = 0.81) the five items. In addition, the adolescent participant completed a survey assessing peer-youth openness which reflects the degree to which the adolescent has a mutually responsive, open, and warm relationship with his/her best friend. This instrument was adapted from the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta, 2001) and the Adult–Child Relationship Scale (Criss et al. 2003). Adolescents rated the 10 items using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “definitely not” to 5 = “definitely”). Five of the items focused on adolescent-to-peer openness (e.g., “If upset about something, I would talk with my friend about it.” “I liked telling my friend about myself.”) and five items focused on peer-to-adolescent openness (e.g., “If my friend was upset about something, he/she would talk with me about it.” “My friend liked telling me about him/herself.”). The peer-youth openness factor (M = 2.41, SD = 0.48) was created by averaging (α = 0.84) the 10 items.

Results

Analytical Plan

First, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the study variables were computed (see Table 1). Next, a series of path analyses were conducted using R with the lavaan package version 0.6–5 (Rosseel 2012) to examine how youth emotion regulation (IV), moderators (parent–youth relationship quality, parental emotion coaching, peer-youth openness, or peer prosocial behavior), and the two-way interaction terms between the IV and moderator were linked to adolescent adjustment (youth antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms) after controlling for youth gender and age. The IV and moderators were centered, and the interaction terms were created using the centered variables. The two dependent variables were examined in the same model. Separate path model was run for each of the four moderators. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used in the path analysis to handle missing data, and robust (Huber-White) standard errors were examined. Model fit was evaluated based on the χ2 fit statistics and other indices including CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR (Bentler 2007). We further probed the significant two-way interactions by examining the simple slopes between IV and adolescent adjustment at low (1 SD below the mean), mean, and high (1 SD above the mean) levels of the moderator (Holmbeck 2002).

Bivariate Correlations

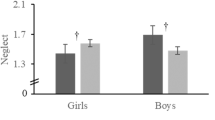

A series of bivariate correlations were computed (see Table 1). The findings indicated that high levels of youth emotion regulation were significantly related to high levels of parental emotion coaching, parent–youth relationships quality, peer prosocial behavior, and peer-youth openness and low levels of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. In addition, parent emotion coaching was positively and significantly related to observed relationship quality. The results also showed that high levels of emotion coaching and relationship quality were significantly related to high levels of peer prosocial behavior and peer-youth openness and low levels of adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Peer prosocial behavior was negatively and significantly related to youth antisocial behavior. Gender was significantly related to parent–youth openness, peer prosocial behavior, and peer-youth openness (higher in girls) and youth antisocial behavior (higher in boys). Finally, age was negatively and significantly related to emotion coaching, relationship quality, and peer prosocial behavior and positively and significantly related to antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms.

Examination of Parents and Peers as Moderating Effects

The four path models fit the data well (see fit indices in the notes for Figs. 1–4). Across the models, findings showed that emotion regulation was significantly and negatively related to youth antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Parental emotion coaching and peer-youth openness were not significantly associated with antisocial behavior or depressive symptoms. Parent–youth relationship quality and peer prosocial behavior were significantly and negatively related to youth antisocial behavior (but not youth depressive symptoms). The parental emotion coaching X youth emotion regulation (see Fig. 2) and peer-youth openness X youth emotion regulation (see Fig. 4) interaction factors were not significantly related to either adjustment outcome. However, as indicated in Fig. 1, the interaction between parent–youth relationship quality and emotion regulation was significantly related to youth antisocial behavior (but not depressive symptoms). Further probing indicated the link between youth emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was significant under low (b = −0.66, p < 0.001) and mean (b = −0.47, p < 0.001) levels of relationship quality (see Fig. 5). This relation was attenuated (albeit still significant) under high levels of relationship quality (b = −0.29, p < 0.001). Moreover, we found that the youth emotion regulation X peer prosocial behavior was marginally associated with antisocial behavior (but not depressive symptoms). Inspection of the slopes indicated that the link between youth emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was significant under low (b = −0.62, p < 0.001) and mean (b = −0.49, p < 0.001) levels of relationship quality (see Fig. 6). This link was attenuated (albeit still significant) under high levels of peer prosocial behavior (b = −0.36, p < 0.001).Footnote 1

Examining parent–youth relationship quality a moderator in the links between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Model fit: χ2 (21) = 172.19, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR = 0.01. PRQ parent–youth relationship quality, YER youth emotion regulation. Youth gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male. Standardized coefficients were presented. Non-significant covariations were omitted for presentation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Examining parent emotion coaching as a moderator in the links between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Model fit: χ2 (21) = 153.48, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR = 0.01. PEC parent emotion coaching, YER youth emotion regulation. Youth gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male. Standardized coefficients were presented. Non-significant covariations were omitted for presentation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Examining peer prosocial behavior as a moderator in the links between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Model fit: χ2 (21) = 182.20, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR = 0.01. PPB peer prosocial behavior, YER youth emotion regulation. Youth gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male. Standardized coefficients were presented. Non-significant covariations were omitted for presentation. †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Examining peer-youth openness a moderator in the links between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Model fit: χ2 (21) = 186.90, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR = 0.01. PYO peer-youth openness, YER youth emotion regulation. Youth gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male. Standardized coefficients were presented. Non-significant covariations were omitted for presentation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine whether adolescent emotion regulation was significantly related to antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms in a diverse, low-income sample. In addition, we investigated whether this link was moderated by supportive parent and peer factors. Findings indicated that adolescent emotion regulation was negatively and significantly related to adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. In addition, the link between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior (but not depressive symptoms) was attenuated under high levels of parent–teen relationships quality and peer prosocial behavior. Implications for positive interpersonal relationships as protective factors are discussed.

Findings indicated that high levels of emotion regulation were significantly related to low levels of adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with evidence in the extant literature (Buckhold et al. 2014; Compas et al. 2017; Yap et al. 2011) and suggest that the ability to regulate negative emotions (i.e., anger, sadness) may play a key role in the development of adjustment difficulties during adolescence. It is possible that adolescents who have poor emotion regulation skills may be more sensitive to cues in social contexts that may lead them to be hostile towards others (Herts et al. 2012). Alternatively, the inability to modulate one’s negative emotions may reflect poor impulse control which could result in externalizing behaviors (Buckholdt et al. 2014).

For the next research goal, we investigated whether parent and peer relationships and characteristics moderated the links between youth emotion regulation and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Results indicated that the emotion regulation X parent–youth relationship quality interaction term was significantly related to antisocial behavior. Moreover, the link between the emotion regulation X peer prosocial behavior interaction term and antisocial behavior was marginally significant. In particular, the association between emotion regulation and antisocial behavior was attenuated under high levels of parent–youth relationships quality and peer prosocial behavior. These findings are consistent with previous research in demonstrating that positive parent and peer relationships may serve as protective factors among at-risk youth (e.g., Alink et al. 2009; Lansford et al. 2003). It is possible that adolescents who have warm and mutually responsive relationships with their parents are more likely to be open to their parents’ socialization efforts and thus less likely to engage in disruptive behavior (Criss et al. 2003; Kochanska 1997). In contrast, friends may play different ameliorating roles among youth with emotion regulation difficulties. That is, prosocial and empathetic friends may serve as positive role models for at-risk youth, perhaps by helping the youth recognize how their negative emotional outbursts influence their relationships with other people. It is also possible that poor and hostile relationships with parents or having friends who display low levels of prosocial behaviors may exacerbate the link between emotion regulation and adjustment difficulties. The somewhat stronger moderating effects for parent-adolescent relationship quality compared to peer prosocial behavior may suggest that parents may be more critical than friends in promoting resilience among at-risk youth (Criss et al. 2017). It should be acknowledged that high levels of the parent and peer factors did not fully mitigate the link between emotion regulation and adolescent antisocial behavior. Thus, it is possible that parents and peers may not completely offset the risks associated with poor emotion regulation.

It is notable that the findings in the current investigation did not demonstrate what could be called cross-domain resilience. That is, in general, positive parent–teen relationships and peer traits promoted resilience regarding antisocial behavior but not depressive symptoms. Just as the value of protective factors may vary by context (Luthar and Cicchetti 2000; Masten and Coatsworth 1998), it is possible that the effectiveness of some buffers may be domain/outcome specific. Indeed, this is consistent with previous work demonstrating that some resilient children may have lingering psychological distress despite achieving competence in other areas (Luthar et al. 1993; Masten and Coatsworth 1998). For instance, Luthar (1991) found that adolescents categorized as resilient (i.e., high risk, behaviorally competent) had higher internalizing symptoms compared to youth who were behaviorally competent but did not come from a high-risk background. This might be why parents and peers promoted resilience in terms of antisocial behavior but not depressive symptoms. Another possible explanation for the findings could be that depressive symptoms may be considered more normative during adolescence compared to antisocial behavior. Indeed, depression is the most common psychological problem during adolescence (Graber and Sontag 2009). It is also feasible that the specific parent and peer factors that we utilized as moderators were not sufficient or salient with respect to promoting resilience for depressive symptoms. Clearly, further research is needed to explore this issue.

Limitations

While the results of the present study provide insight into factors and processes that may promote resilience among at-risk adolescents, there were limitations that need to be acknowledged. One limitation was the cross-sectional design. Although we hypothesized that emotion regulation would be related to adjustment difficulties, there is some preliminary evidence that this association may be reciprocal in nature (Kim-Spoon et al. 2013). Future investigations would benefit from longitudinal designs. Additionally, this sample was comprised predominantly of ethnic minorities from low-income and single parent families. It is possible that different patterns of findings may be evidenced using different types of samples. Although mother, adolescent, and observation ratings were utilized in the assessment of the factors in the current study, future research would benefit from using other informants (e.g., friends, fathers) and methods (e.g., interviewer ratings, physiology arousal and regulation). Finally, the factors assessed in the current investigation were not meant to be an exhaustive overview of all forms of emotions (e.g., fear), protective factors (i.e., teacher-student relationships, sibling relationships, IQ), or adolescent outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, binge drinking).

Implications

Despite the limitations, the current study found evidence for possible protective factors among at-risk youth using a multi-method and multi-informant design. These findings have implications for service providers, counselors, and interventionists. For example, future inventions may benefit from using both parents and peers in programs targeting high-risk youth. Indeed, there is evidence that including parents in programs may be more successful compared to youth-only programs (see Gorman-Smith and Tolan 2003). Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of emotion regulation interventions involving parents that are applicable to most negative emotions (e.g., anger, sadness), including the “Tuning into Teens” program (Havighurst et al. 2013). Regarding peers, there is some evidence that friends (especially antisocial peers) may hinder the efficacy of group-based prevention programs (Dodge and Sherrill 2006). However, the findings from the current study suggest that including prosocial and empathetic friends may improve the success of such programs.

Notes

The effects of three-way interactions (IV, moderator, and adolescent age) also were examined in separate exploratory path models for each moderator. None of the three-way interactions were significant indicating that there were no significant age differences regarding the moderating effects of parents and peers.

References

Alink, L. R., Cicchetti, D., Kim, J., & Rogosch, F. A. (2009). Mediating and moderating processes in the relation between maltreatment and psychopathology: mother–child relationship quality and emotion regulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-0099314-4.

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., & Pickles, A. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249.

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024.

Bowes, L., Joinson, C., Wolke, D., & Lewis, G. (2015). Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. British Medical Journal, 350, 9 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2469.

Buckholdt, K. E., Parra, G. R., & Jobe-Shields, L. (2014). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation through parental invalidation of emotions: implications for adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9768-4.

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110.

Consedine, N. S., Magai, C., Horton, D., & Brown, W. M. (2012). The affective paradox: an emotion regulatory account of ethnic differences in self-reported anger. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(5), 723–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111405659.

Cooper, M. L., Wood, P. K., Orcutt, H. K., & Albino, A. (2003). Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.390.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

Criss, M. M., Houltberg, B. J., Cui, L., Bosler, C. D., Morris, A. S., & Silk, J. S. (2016a). Direct and indirect links between peer factors and adolescent adjustment difficulties. Journal of applied developmental psychology, 43, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.002.

Criss, M. M., Morris, A. S., Ponce‐Garcia, E., Cui, L., & Silk, J. S. (2016b). Pathways to adaptive emotion regulation among adolescents from low‐income families. Family Relations, 65(3), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12202.

Criss, M. M., Shaw, D. S., & Ingoldsby, E. M. (2003). Mother–son positive synchrony in middle childhood: relation to antisocial behavior. Social Development, 12(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.002.

Criss, M. M., Smith, A. M., Morris, A. S., Liu, C., & Hubbard, R. L. (2017). Parents and peers as protective factors among adolescents exposed to neighborhood risk. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 53, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.10.004.

Cui, L., Morris, A. S., Harrist, A. W., Larzelere, R. E., Criss, M. M., & Houltberg, B. J. (2015). Adolescent RSA responses during an anger discussion task: relations to emotion regulation and adjustment. Emotion, 15(3), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000040.

Dahl, R. E. (2004). Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. In R. E. Dahl & L. P. Spear (Eds.), Adolescent brain development: vulnerabilities and opportunities (pp. 1–22). New York, NY, US: New York Academy of Sciences.

Dodge, K. A., & Sherrill, M. R. (2006). Deviant peer group effects in youth mental health interventions. In K. A. Dodge, T. J. Dishion, J. E. Lansford, K. A. Dodge, T. J. Dishion & J. E. Lansford (Eds.), Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: problems and solutions (pp. 97–121). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1998). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), , Handbook of child psychology: social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 701–778). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Eisenberg, N., & Morris, A. (2002). Children’s emotion-related regulation. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior, vol. 30 (pp. 189–229). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press.

Eisenberg, N., VanSchyndel, S. K., & Spinrad, T. L. (2016). Prosocial motivation: inferences from an opaque body of work. Child Development, 87(6), 1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12638.

Ellis, B. J., McFadyen-Ketchum, S., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: a longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.387.

Farrell, A. D., Danish, S. J., & Howard, C. W. (1992). Relationship between drug use and other problem behaviors in urban adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 705 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.705.

Farrell, A. D., Kung, E. M., White, K. S., & Valois, R. F. (2000). The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(2), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13.

Fite, P. J., Vitulano, M., Wynn, P., Wimsatt, A., Gaertner, A., & Rathert, J. (2010). Influence of perceived neighborhood safety on proactive and reactive aggression. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(6), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20393.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015.

Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022658222914.

Gorman-Smith, D., & Tolan, P. H. (2003). Positive adaptation among youth exposed to community violence. In S. S. Luthar & S. S. Luthar (Eds.), Resilience and vulnerability: adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (pp. 392–413). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615788.018.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243.

Graber, J. A., & Sontag, L. M. (2009). Internalizing problems during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), 3rd ed.; handbook of adolescent psychology: individual bases of adolescent development (vol. 1, 3rd ed.). 3rd ed. (pp. 642–682). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Gross, J. J. (2014). Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Gross, J. J. (2015). The extended process model of emotion regulation: elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.989751.

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Kehoe, C., Efron, D., & Prior, M. R. (2013). ‘Tuning into kids’: reducing young children’s behavior problems using an emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44(2), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1.

Herts, K. L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2012). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking stress exposure to adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9629-4.

Holmbeck, G. N. (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87.

Kent, L., Vostanis, P., & Feehan, C. (1997). Detection of major and minor depression in children and adolescents: evaluation of the mood and feelings questionnaire. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01543.x.

Kim-Spoon, J., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2013). A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability-negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development, 84(2), 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01857.x.

Klimes-Dougan, B., Brand, A., & Garside, R.B. (2001, August). Factor structure, reliability, and validation of an emotion socialization scale. In C. O’Neil (Chair), Multiple approaches to emotion socialization: methodology and emotional development. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA.

Klimes-Dougan, B., Brand, A. E., Zahn-Waxler, C., Usher, B., Hastings, P. D., Kendziora, K., & Garside, R. B. (2007). Parental emotion socialization in adolescence: differences in sex, age and problem status. Social Development, 16(2), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00387.x.

Kochanska, G. (1997). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: implications for early socialization. Child Development, 68(1), 94–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131928.

Lansford, J. E., Criss, M. M., Dodge, K. A., Shaw, D. S., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2009). Trajectories of physical discipline: early childhood antecedents and developmental outcomes. Child Development, 80(5), 1385–1402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01340.x.

Lansford, J. E., Criss, M. M., Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Bates, J. E. (2003). Friendship quality, peer group affiliation, and peer antisocial behavior as moderators of the link between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(2), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1302002.

Larson, R., & Lampman-Petraitis, C. (1989). Daily emotional states as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development, 60(5), 1250–1260. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130798.

Luthar, S. S. (1991). Vulnerability and resilience: a study of high‐risk adolescents. Child Development, 62(3), 600–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x.

Luthar, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004156.

Luthar, S. S., Doernberger, C. H., & Zigler, E. (1993). Resilience is not a unidimensional construct: insights from a prospective study of inner-city adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006246.

Magai, C., & O’Neal, C. R. (1997). Emotion as a Child (Child Version). Brooklyn, NY: Long Island University.

Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.205.

Melby, J., Conger, R., Book, R., Rueter, R., Lucy, L., Repinski, D., & Scaramella, L. (1998). The Iowa family interaction rating scales. 5th ed. Ames, IA: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research. Iowa State University.

Morris, A.S., Houltberg, B. J., Criss, M. M., & Bosler, C. (2017). Family context and psychopathology: the mediating role of children’s emotion regulation. In L. Centifanti & D. Williams (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118554470.ch18

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Paus, T. (2009). Brain development. In R. M. Lerner, L. Steinberg, R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: individual bases of adolescent development (pp. 95–115). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001005.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling and more. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Selman, R. L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. London: Academic Press.

Spear, L. P. (2000). The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 24(4), 417–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(00)00014-2.

Steinberg, L., Dahl, R., Keating, D., Kupfer, D. J., Masten, A. S., & Pine, D. S. (2006). The study of developmental psychopathology in adolescence: Integrating affective neuroscience with the study of context. In D. Cicchetti, D. J. Cohen, D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: developmental Neuroscience (pp. 710–741). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. 10.1002/9780470939390.ch18

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83.

Wood, A., Kroll, L., Moore, A., & Harrington, R. (1995). Properties of the mood and feelings questionnaire in adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a research note. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 36(2), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01828.x.

Willoughby, T., Good, M., Adachi, P. J., Hamza, C., & Tavernier, R. (2013). Examining the link between adolescent brain development and risk taking from a social–developmental perspective. Brain and Cognition, 83(3), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2013.09.008.

Yap, M. H., Allen, N. B., O’Shea, M., Di Parsia, P., Simons, J. G., & Sheeber, L. (2011). Early adolescents’ temperament, emotion regulation during mother–child interactions, and depressive symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000787.

Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Penza-Clyve, S. (2001). Development and initial validation of the Children’s Sadness Management Scale. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 25(3), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010623226626.

Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Suveg, C. (2002). Anger and sadness regulation: predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1207/153744202760082658.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oklahoma Agriculture Experiment Station Project grant (OKL02659), an Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) grant Project (#HR11-130), and a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R15HD072463-01) R15 grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Oklahoma State University Internal Review Board–IRB: HE0886) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Specifically, parents provided consent for their participation and the participation of their children ages 10–17 years. Adolescent assent was taken for children ages 10–17 years. Adolescents who were 18 years old provided consent for their participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Criss, M.M., Cui, L., Wood, E.E. et al. Associations between Emotion Regulation and Adolescent Adjustment Difficulties: Moderating Effects of Parents and Peers. J Child Fam Stud 30, 1979–1989 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01972-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01972-w