Abstract

A lack of empathy is related to some negative aspects of adolescent interpersonal functioning in the literature, such as bullying. However, the relationship between empathy and positive aspects of adolescent interpersonal functioning is less clear. Thus, this study sought to examine the association between empathy and positive components of peer relationships among adolescents. A scoping review was conducted to identify relevant literature and to provide a narrative overview of the identified studies. Three databases were searched (PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Sociological Abstracts). Subsequently, three reviewers independently analyzed articles to determine inclusion. Twenty-eight studies met inclusionary criteria. The aspects of peer relationships that were studied most frequently included peer attachment, social status (i.e., peer acceptance, likeability, social preference, and popularity), and friendship closeness or quality. The associations between empathy and some aspects of peer relationships among adolescents varied based on type of empathy and gender. Although inconsistencies were observed, the included studies often showed either a positive relationship or no relationship between empathy and positive peer relationship variables. In several studies, empathy was positively related to peer attachment and friendship quality or closeness, but not significantly related to popularity. Additional research is needed to further clarify these relationships. The results are integrated within a positive psychology framework examining the role of empathy as a potential strength in interpersonal functioning.

Highlights

-

Most studies reported positive correlations or no correlation between empathy and positive aspects of adolescent peer relationships.

-

Greater friendship quality or closeness and peer attachment were often related to higher empathy.

-

Based on the reviewed literature, empathy does not appear to be a robust strength in interpersonal functioning among adolescents.

-

More research is needed to clarify the role of empathy in adolescent peer relationships and to explore youth’s perceptions of empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As children transition into adolescence, friendships and peer relationships become increasingly important and complex (Brown and Larson 2009). Compared to friendships in childhood, adolescent friendships are characterized by greater disclosure and intimacy, and the formation of more significant attachment bonds (Gorrese and Ruggieri 2012). With increasing independence, adolescents begin to rely less upon the emotional support of parents and more on the emotional support of friends (Arnett 2010). During this developmental period, both peer relationships and friendships are important. Peers refer to individuals who share a common aspect of status and are typically of a similar age within a social network, community, or school. Friendships, on the other hand, refer to close, mutual relationships between individuals and only some peer relationships are also considered friendships (Arnett 2010). The importance of both friends and peers for adolescents means that these relationships account for a significant amount of social emotional interaction and influence in their lives. These interactions can be positive or negative and it is important to consider what factors enhance prosocial and other positive behaviours and whether gender has an influence.

Peer relationships can be defined as interactions, both positive and negative, with same-age peers (Naylor 2011). In this paper, we focus on the positive aspects of such interactions. Positive peer relationships are related to a number of variables, including peer attachment, friendship quality, and social status such as peer acceptance, perceived popularity, likability, and social preference. Peer attachment, which involves dimensions of trust and communication, is in turn associated with positive attributes such as high self-esteem (Gorrese and Ruggieri 2013). For example, self-esteem has accounted for the relationship between peer attachment and positive psychological wellbeing in cross-sectional studies (Wilkinson 2004). Peer social status, which is generally comprised of peer acceptance and perceived popularity (Cillessen and Marks 2011), refers to the extent that peers like an individual (i.e., likeability; de Bruyn et al. 2010; Oberle et al. 2010). A related construct is social preference, which takes into account both acceptance and rejection nominations when considering one’s desire to carry out school or leisure activities with peers (Coie et al. 1982; Zorza et al. 2013). Perceived popularity entails “visibility, prestige, or dominance” (de Bruyn et al. 2010, p. 544). Other variables may relate to popularity status such as number of friends, social reputation, and social impact. Peer acceptance and preference are considered to be different from perceived popularity since youth who are viewed as popular may not necessarily be liked (de Bruyn et al. 2010). More preferred and popular peers report higher friendship quality (Nangle et al. 2003; Poorthuis et al. 2012). An important distinction is made between negative and positive friendship quality. Negative friendship quality includes conflict and imbalance (Bukowski et al. 1994). Positive friendship quality includes aspects of intimacy, closeness, and companionship (Bukowski et al. 1994), which imply the presence of empathy and understanding the feelings of others. Peers who report higher friendship quality report higher psychological wellbeing and less deviant behaviour (Poulin et al. 1999; Rubin et al. 2004). Additionally, there is evidence of gender differences in male and female peer relationships, such as structure (e.g., number of friends, peer group size) and content (e.g., rough and tumble play, self-disclosure, consideration and caring, which suggests a different role of empathy in male and female peer relationships; Rose and Rudolph 2006; Rose and Smith 2009).

Similar to the multiple aspects of positive peer relationships, there are multiple components of empathy. First, a discussion of how empathy is defined is warranted, particularly since this definition has varied in the literature (Reniers et al. 2011). For example, empathy has been defined as “the reactions of one individual to the observed experiences of another” (Davis 1983, p. 113) and “…the cognitive awareness of another person’s internal states…[and] the vicarious affective response to another person” (Hoffman 2000, p. 29). Importantly, empathy consists of both cognitive and affective components. The cognitive component of empathy consists of being able to consider and understand what another person is thinking and feeling (Davis 1983). This ability to consider another person’s thoughts and intentions is sometimes referred to in the literature as mindreading (Cavojova et al. 2011), perspective taking, theory of mind, or mentalizing (Singer and Klimecki 2014). However, Cavojova et al. assert that mindreading should not be equated with empathy since empathy entails an understanding of emotions. The affective component of empathy consists of experiencing an emotion in response to another person’s emotions (Davis 1983; Spreng et al. 2009). Sometimes affective empathy is referred to as empathic concern or sympathy. Empathetic and personal distress have also been considered forms of empathy. Empathetic distress consists of “emotional involvement in the problems and distressed feelings of a relationship partner, to the point of taking on the partner’s emotional distress and experiencing it as one’s own” (Smith and Rose 2011, p. 1792). This type of distress differs from personal distress, as personal distress consists of focusing on one’s own emotional distress to the extent that other people’s emotions or experiences are not acknowledged (Smith and Rose 2011). Personal distress involves more of a focus on the self than the other empathy components discussed. It is also important to note that there is evidence of gender differences in the capacity for empathy itself (e.g., a female advantage for affective empathy; see review in Christov-Moore et al. 2014).

To some degree, greater empathy is theoretically purported to relate to more positive peer interactions. For example, if an individual is able to understand the perspective and emotions of another, it is believed that they will have more positive views of out-groups (Batson and Ahmad 2009) and will generally be less likely to interact with others in a negative manner (Lovett and Sheffield 2007). On the other hand, having high empathic distress has been suggested to relate to focusing on one’s self and one’s own distress, which may lead to acting in a way that is not as helpful to others (Eisenberg and Fabes 1990). Some empirical research has been generated that supports these theories, but inconsistencies are evident. For instance, van Noorden et al. (2015) found that bullying was negatively associated with affective empathy but that the relationship between cognitive empathy and bullying was less consistent. In addition, higher empathy has been related to positive aspects of peer relationships such as peer attachment (Laible et al. 2004), positive conflict management strategies (de Wied et al. 2007), and friendship quality (Smith and Rose 2011). Empathy has also been related to peer acceptance, although the nature of this relationship may differ by gender. For example, Oberle et al. (2010) found that empathy was a positive predictor of girls’ acceptance of peers, but empathy was a negative predictor of boys’ acceptance of peers. Other studies have also reported some negative correlates of high empathy. Smith and Rose (2011) described there to be “costs of caring” as they found greater social perspective taking to relate to higher empathetic distress.

Affective and cognitive empathy may also relate differently to aspects of interpersonal functioning. For example, among a sample of undergraduate students, Davis (1983) found that perspective taking modestly related to higher quality social functioning while the relationship between empathic concern and social functioning was less consistent. Empathic concern was positively related to shyness, social anxiety, and audience anxiety, but negatively related to loneliness and undesirable social characteristics (e.g., boastfulness; Davis 1983). Considering the various ways in which empathy may relate to peer relationships and the mixed findings on this topic, conducting a review of research would be of benefit in order to consolidate and summarize the research that exists in this area, identify gaps in the literature, and offer guidance for future research.

The purpose of this study was to examine and synthesize current literature on the relationship between empathy and positive aspects of peer relationships among adolescents. A scoping review was selected because they are suitable for initially gauging the research in an area, taking a broad focus, and incorporating various research designs (Levac et al. 2010). Given the nature of the existing research in this area and the lack of randomized controlled trials, a scoping review was believed to be more appropriate than a meta-analysis. Exploring how empathy relates to positive aspects of adolescent peer relationships aligns with a positive psychology perspective. Positive psychology focuses on growing positive qualities to allow individuals to thrive, rather than focusing on the qualities that contribute to illness (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). At its foundation is the belief that individuals want to lead fulfilling lives, cultivate their best qualities, and enhance all areas of their lives. From a positive psychology perspective, adolescents should be motivated to enhance their peer relationships. We proposed that cultivating a positive quality such as empathy might be one way of accomplishing this, in turn leading to greater adolescent wellbeing. The importance of empathy as a positive quality in peer relationships is supported by the fact that it is linked to greater wellbeing (Tan et al. 2011; Vinayak and Judge 2018) and prosocial behaviour (McMahon et al. 2006). Moreover, it is included as one of the interpersonal functioning components within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition (DSM-5) Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Thus, consolidation of the literature on how empathy relates to positive interpersonal functioning among adolescent peers is warranted. Given that gender differences have been documented in both the development of peer relationships and empathy, attention was given to any gender differences or interactions documented in the existing research to provide a greater understanding of the current findings. Our secondary aim was to determine whether empathy should be considered a strength within interpersonal peer relationships among adolescents. Through this aim, as well as the overall focus on positive aspects of peer functioning, the review utilizes a positive psychology framework.

Method

The scoping review methodological protocols outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac et al. (2010) guided the methods of this paper. Search criteria were devised and tailored to PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Sociological Abstracts. The general search terms that were used are outlined in Table 1. Database-specific subject headings were used as a part of the searches in PsycINFO and Sociological Abstracts, such as “Empathy”, “Peer Relations”, “Interpersonal Interaction” and “Interpersonal Relations”. The number of articles identified through these searches and the screening process of these articles is outlined in Fig. 1. As an initial step, the first three authors independently screened the relevance of article titles for inclusion. Titles that did not contain a term related to either empathy or peer functioning, broadly defined, were excluded. Next, the authors clarified the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be applied during the abstract screening phase. Articles were included if they entailed an adolescent, non-clinical sample, measured empathy or a related construct (e.g., theory of mind, prosocial attitudes), measured an aspect of peer relationships (e.g., bullying, friendship quality, etc.), were published between 2000-2017, and were published in English. Review articles, qualitative studies, and case studies were excluded. The first three authors independently reviewed abstracts using these criteria.

Following Levac et al. (2010) recommendation that reviewers meet during the abstract screening phase to discuss challenges, the three reviewers met after each reviewing 50 abstracts and after reviewing all abstracts. During these meetings, the reviewers discussed any questions that arose and collaboratively decided on inclusion or exclusion for abstracts that were unclear in meeting eligibility requirements. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were further clarified during this process.

Next, the reviewers screened the article text to determine inclusion and exclusion. The first author reviewed all articles while the second and third authors each reviewed approximately half of the articles so that two reviewers screened every article. A meeting was held during this process where the inclusion/exclusion criteria were further narrowed. To be included, studies were required to (a) have an adolescent (mean age between 10–18 years), non-clinical sample, (b) measure empathy or sympathy with a questionnaire, (c) measure an aspect of peer relationships with a questionnaire, (d) statistically analyze the relationship between empathy and peer functioning variables, and (e) have been published between 2000 and 2017 in English. The studies were restricted to those published after 2000 in order to contain the number of articles to an amount that was reasonable for a narrative review. If the mean age was not provided but the age range of participants was between 10–18 years, then such articles were included. Studies with college or university students as participants were excluded. Review articles, case studies, qualitative studies, and intervention studies that did not measure and statistically relate both empathy and interpersonal functioning variables at pre-intervention, were also excluded. The reviewers applied these refined criteria and recorded the following: decision regarding article relevance (i.e., include, exclude, or unsure), reason for exclusion if applicable, and the specific empathy and interpersonal variables measured within the articles they believed met inclusion criteria. Cohen’s κ was conducted to examine interrater agreement based on the three decisions that each reviewer could have made—include, exclude, or unsure about inclusion/exclusion. Reviewer 1 and 2 rated 97 of the same articles, κ = 0.67. Reviewers 1 and 3 rated 91 of the same articles, κ = 0.62. These values are indicative of moderate agreement (McHugh 2012). Utilizing the option of “unsure” when rating an article likely somewhat lowered the level of agreement. The three reviewers held a meeting to discuss disagreements. All disagreements were resolved through discussion.

As 83 articles were identified and the articles covered a wide breadth of interpersonal functioning variables, the reviewers decided to narrow the scope of the paper to only the positive interpersonal functioning variables related to peer relationships. Thus, articles examining only negative aspects of interpersonal relationships such as bullying or aggression were excluded. This decision was based upon the existing literature (e.g., a systematic review of the relationship between empathy and bullying has been published by van Noorden et al. 2015) and the fact that focusing on positive interpersonal relationship variables better aligned with the authors’ intention to examine empathy from a positive psychology framework. Prosocial behaviour was also excluded as this variable was sometimes measured generally rather than within the context of peer relationships.

As the authors had recorded the variables measured in each article during the screening process, this information was used to apply the refined exclusion criteria and narrow the list of articles to only those examining the relationship between empathy and positive peer connections among adolescents. The reference lists of these articles were screened (see Fig. 2). If an article title was related to both empathy and positive peer relationships, the first author screened the abstract. The first and second authors screened the full text of the three identified articles, with perfect agreement. One article met the inclusion criteria.

Upon further examination of the eligible articles, the inclusion criteria were further narrowed (see Fig. 3) by excluding variables that were (a) only examined within one article and (b) not as closely related to the more frequently studied interpersonal variables. Specifically, if the only interpersonal variable measured by an article was school culture, valuing friendship, communal social goals, leadership, or caring climate, then the article was excluded. This left 28 eligible articles remaining for inclusion in the review. As the final step, the reviewers each read a portion of the included articles and extracted information independently. This process entailed confirming if the article met the refined inclusion criteria and recording details about the article’s sample, methodology, and results.

Results

Twenty-eight studies met inclusion criteria. The included studies’ sample, variables measured, and findings are outlined in Table 2. Only information relevant to the relationship between empathy and positive peer relationships are reported. Please see Table 3 for a tally of the empathy measures used in each study and Table 4 for a tally of the peer relationship measures used in each study.

Since various peer relationship variables were examined within the included studies (see Table 2), both quantitative and narrative syntheses are provided in order to understand how these variables relate to empathy. Several studies reported correlations between cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and general empathy, and the peer relationship variables, which are summarized in Table 5. Only articles that reported a correlation statistic and indicated significance with a p value are reflected in Table 5. To further describe the findings and present the results of all types of statistical analyses utilized within the included studies, a narrative synthesis is provided below for the following peer relationship domains that were examined most frequently: peer attachment, social status, and friendship closeness and quality.

Peer Attachment

Peer attachment is an important component of peer functioning during adolescence that encompasses an enduring affectional bond between peers. Three studies reported that peer attachment was positively and significantly correlated with perspective taking, empathic concern, or general empathy (see Table 4) among both boys and girls (Llorca-Mestre et al. 2017; You and Kim 2016; You et al. 2015; correlation coefficients ranged from 0.21 to 0.43, p ranged from <0.01 to <0.001). In addition, peer attachment was not significantly related to personal distress for boys and girls (Llorca-Mestre et al. 2017).

Social Status

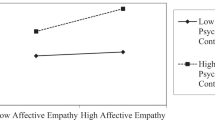

The following peer relationship variables were included under social status: peer acceptance, likeability, social preference, and perceived popularity and related aspects (e.g., number of friends). As shown in Table 5, peer acceptance/likeability/social preference was positively related to affective empathy in four studies (Meuwese et al. 2017; Oberle et al. 2010; Zorza et al. 2013, 2015; correlation coefficients ranged from 0.10 to 0.373, p ranged from < 0.001 to < 0.05), negatively related to affective empathy in one study (Oberle et al. 2010; r = −0.262, p < 0.01), and unrelated to affective empathy in four studies (Caravita et al. 2009, 2010; Huang and Su 2014; Pöyhönen et al. 2010). A gender difference in these relationships was reported by Oberle et al. (2010) who found that empathic concern was significantly and negatively correlated with peer acceptance among boys, but significantly and positively correlated with peer acceptance among girls. Overall, the relationship between affective empathy and peer acceptance/likeability/social preference is quite varied and appears to differ based on gender.

Peer acceptance/likeability/social preference was positively related to cognitive empathy among boys in one study (Huang and Su 2014; r = 0.213, p < 0.05) but unrelated to cognitive empathy among a sample of girls in Huang and Su’s study and among combined samples of girls and boys in five additional studies (Caravita et al. 2010; Meuwese et al. 2017; Pöyhönen et al. 2010; Zorza et al. 2013, 2015). Thus, the included articles in this study do not appear to support a robust relationship between cognitive empathy and peer acceptance/likeability/social preference and to differ by gender in some cases.

Perceived popularity was not significantly related to affective empathy in four studies (Caravita et al. 2009, 2010; Meuwese et al. 2017; Pöyhönen et al. 2010). One study found perceived popularity to be significantly and positively correlated with cognitive empathy (Pöyhönen et al. 2010; correlation coefficient = 0.31, p < 0.001), while two studies found no significant association between the two (Caravita et al. 2010; Meuwese et al. 2017).

Some studies examined related aspects of perceived popularity, including number of friends, friendship nominations, social reputation, social impact, and impressions of a new peer. Cavojova et al. (2011) found that theory of mind (understanding another’s mental state), compared to empathy (understanding another’s emotions), better predicted the number of friends a person reported having. In another study it was found that female opposite-sex associations (i.e., relationship between female empathy and number of friend nominations that females received from males) were non-significant, whereas the male opposite-sex associations were significant (Ciarrochi et al. 2017; t > 2, p < 0.05). The female same-sex associations between empathy (both cognitive and affective) and friendship nominations tended to be small or nonsignificant, while the male same-sex associations tended to be small and significant (Ciarrochi et al. 2017). Estévez López et al. (2008) found that empathy was significantly correlated with perceived social reputation for boys and girls, and ideal social reputation for boys, but not significantly correlated with ideal social reputation for girls. In a different sample of youth, Estévez López et al. (2016) found that empathy and perceived and ideal social reputation were not correlated among boys, and negatively and significantly correlated among girls (r = −0.19, −0.16, p < 0.001). Huang and Su (2014) found that emotional empathy was positively and significantly correlated with social impact (the degree to which an adolescent can influence his or her peers) among girls (r = 0.177, p < 0.05), but not among boys. Finally, in a study examining the behavioural intentions (e.g., desire to engage a peer in academic, social, and general activities) of young adolescents towards a new hypothetical peer with cancer, significantly more favourable impressions about the hypothetical new peer with cancer were reported by those in the high empathy group compared to those in the low or moderate empathy group (Gray and Rodrigue 2001). Overall, the relationship between empathy and perceived popularity and related aspects such as number of friends is again varied with few studies reporting a significant association. However, many studies reported a gender difference.

Friendship Closeness and Quality

Six studies reported a significant relationship between a type of empathy and friendship closeness or quality (Chow et al. 2013; Meuwese et al., 2017; Overgaauw et al. 2017; Smith 2015; Smith and Rose 2011; Soenens et al. 2007; correlation coefficients ranged from 0.23 to 0.72; p ranged from <0.01 to <0.001). Meuwese et al. (2017) found that negative friendship quality (e.g., friendship consisting of conflict) was significantly and negatively correlated with cognitive empathy (r = −0.15, p < 0.01) and prosocial motivation (r = −0.26, p < 0.001) but not significantly related to affective empathy. However, positive friendship quality (e.g., friendship consisting of positive qualities such as security) was positively and significantly correlated with all three empathy subscales (r = 0.27–0.45, p < 0.001). Meuwese et al. also found that the relationship between the likeability of one’s friend and friendship quality was partially mediated by empathy and prosocial motivation. In Smith’s study, friend dyads engaged in a conversation about a problem and a conversation about positive life events before each completing measures of empathetic distress and empathetic joy, respectively. Participants completed the measures of empathetic distress and joy with respect to that conversation, thus reflecting situational measures. Friendship quality was positively and significantly related to both empathetic distress (r = 0.37, p < 0.01) and empathetic joy (r = 0.45, p < 0.01). Empathetic distress and empathetic joy both predicted greater friendship quality (Smith 2015). Soenens et al. (2007) further investigated the relationships between empathy and friendship quality. Although they found that adolescent sympathy (i.e., empathic concern) and perspective taking both positively and significantly correlated with friendship quality (r = 0.23, 0.24, respectively, p < 0.01), perspective taking predicted friendship quality but sympathy did not.

In addition, empathy has been related to relationship commitment, friendship closeness and support. Johnson et al. (2013) found that empathy and relationship commitment were positively correlated among the overall sample (r = 0.22, p < 0.01), but this relationship was not significant when examined separately among girls and boys. Among a sample of 10th graders, Chow et al. (2013) found that empathy was significantly correlated with intimacy and friendship closeness (respective correlation coefficients = 0.49, 0.28, p < 0.01). Lastly, Ciarrochi et al. (2017) found that cognitive and affective empathy were related to higher friendship support across both males and females. When controlling for friendship quantity, affective and cognitive empathy substantially predicted friendship support in males and females (Ciarrochi et al. 2017). In summary, though there are some varied findings, several articles support an association between friendship quality or closeness and affective or cognitive empathy.

Discussion

This scoping review explored recent literature on the relationships between positive aspects of peer relationships and empathy among adolescents. In addition to better understanding the relationships between these variables, we also sought to guide future research in this area by utilizing a positive psychology framework.

Table 5 indicates that very few studies reported significant and negative correlations between the positive peer relationship and empathy variables. Rather, several studies found no relationship between these variables or positive correlations. The results varied based on gender and the type of empathy examined. Peer attachment, social status (including peer acceptance/likeability/preference and perceived popularity), and friendship quality or closeness were the most frequently studied peer relationship variables.

The three included studies examining peer attachment and empathy reported that peer attachment was positively and significantly correlated with perspective taking and empathic concern (Llorca-Mestre et al. 2017; You and Kim 2016; You et al. 2015). This finding aligns with other studies showing that peer attachment (as well as parent attachment in Laible 2007) predicted empathy among older adolescents (Laible et al. 2004, 2007). As Laible (2007) found that peer attachment was a stronger predictor of most socioemotional variables than was parent attachment, they suggest that although parental attachment is still important, peer attachment may uniquely contribute to the development of socioemotional qualities. The fact that empathy is associated with peer attachment is important since secure peer attachment is related to increased self-esteem (Gorrese and Ruggieri 2013) and reduced likelihood of developing internalizing problems (Gorrese 2016). However, the nature and directionality of the relationship between peer attachment and empathy requires further investigation. It could be that understanding the emotions and thoughts of one’s peers as well as responding to their emotions allows adolescents to connect with their peers in a meaningful way. Alternatively, being close with a peer may foster the development of empathy as one may have more opportunity to understand their thoughts and emotions. If empathy contributes to improved peer attachment then empathy could be targeted to enhance adolescent wellbeing. It potentially adds weight to the value of including programming in schools and school curricula (such as Malti et al. 2016) that seek to foster and promote empathy.

The relationship between affective empathy and peer acceptance/likeability/social preference was characterized by varied results. Thus, how affective empathy relates to peer acceptance/likeability/social preference is unclear and requires further investigation. For example, affective empathy was positively associated with peer acceptance/likeability/social preference in four studies, unrelated in four studies, and negatively related in one study. However, cognitive empathy was generally not significantly related to peer acceptance/likeability/social preference (not related in five studies but positively related in one study for boys, not girls). In other words, the extent that an adolescent considers what another person is thinking, was generally not related to how well the adolescent was liked by peers. This implies that when providing empathy interventions, awareness of what others think may be insufficient on its own; rather, an emotional responsiveness component would likely need to be included and perhaps given greater attention.

Similarly, few studies reported a significant relationship between popularity and empathy. A lack of relationship between these variables is not surprising since popularity could be achieved through the use of manipulative or aggressive behaviours (de Bruyn et al. 2010), which seem contrary to displaying affective and cognitive empathy. Yet, Huang and Su (2014) found that the degree to which adolescents can influence their peers (i.e., social impact) was positively and significantly correlated with emotional empathy among girls. However, it is unclear how the social impact assessed in this study was achieved by students (i.e., through manipulative tactics or through more positive means). Further research is again needed to confirm if empathy is generally unrelated to perceived popularity and whether the means by which adolescents achieve their social impact is negative or positive.

Affective and cognitive empathy were related to friendship quality or closeness in several studies. Again, longitudinal research is needed to elucidate how these variables relate to one another temporally. Nevertheless, there appears to be an important connection between empathy and friendship quality or closeness. Chow et al. (2013) found that interpersonal competence was consistent with a mediator of the relationship between empathy and friendship quality. Specifically, intimacy competence (i.e. self-disclosure and support) mediated the relationships between empathy and friendship closeness (as perceived by oneself and one’s friend), and conflict management competence mediated the relationship between empathy and friendship discord (as perceived by oneself and one’s friend). Therefore, enhancing interpersonal competence skills such as intimacy and conflict management, within empathy intervention programs, may be beneficial in promoting friendship quality. Chow et al. suggest that intervention programs focus on interpersonal competence skills within specific friend dyads since they found mutual relationships between these variables among friend dyads.

Among the main studies reviewed that reported on gender differences, all but one found higher levels of empathy among females compared to males (Barr and Higgins-D’Alessandro 2007; Cavojova et al. 2011; Chow et al. 2013; Ciarrochi et al. 2017; de Wied et al. 2007; Estévez López et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2013; Llorca-Mestre et al. 2017; Overgaauw et al. 2017; Pöyhönen et al. 2010; Smith 2015; Smith and Rose 2011; Soenens et al. 2007; Wentzel et al. 2007; Wölfer et al. 2012; You and Kim 2016; You et al. 2015). The one exception to this finding was a study that found a lack of statistical difference between males and females on perspective taking and empathic concern (Zorza et al. 2015). Evolutionary theoretical perspectives propose that females may experience greater empathy because traditionally it has been the role of the female to take care of and nurture supportive social relationships to help ensure the survival of their offspring (Geary 2010). Socialization theories propose that humans play a critical role in influencing gender differences by either explicitly or subtly reinforcing these differences, for example, by talking more to girls than to boys about emotions and caring for others’ wellbeing (Rose and Smith 2009). Parents, teachers, and peers are encouraged to be mindful of gender role stereotypes and their role in reinforcing gender-typed behaviour. If people refrain from words and behaviours that encourage males to be “manly” and unaffected by emotions, it may help to increase their empathy levels. Intervention programs designed to increase empathy levels among students should also take gender differences into account and tailor their protocols appropriately.

As this paper employed a positive psychology framework, consideration was given to whether empathy acts as a strength within the context of adolescent interpersonal peer relationships. Rawana and Brownlee (2009) define a strength as “a set of developed competencies and characteristics that is valued both by the individual and society and is embedded in culture” (p. 256). According to this definition, empathy would need to be valued by both an adolescent and society in order to be considered a strength. Future research could attempt to clarify under what circumstances and conditions adolescents value their own empathic qualities. Although empathy is associated with a host of positive outcomes, including prosocial behaviour (Laible et al. 2004), not all of the included studies reported a positive association between a positive aspect of peer relationships and empathy. Moreover, some studies have shown a link between increased empathy and increased aggression (see Buffone and Poulin 2014). The “costs of caring” must also be considered, given that greater social perspective taking has been found to relate to higher empathetic distress (Smith and Rose 2011). This work raises a question about the role of empathy and the implications of empathy training programs, which suggests that empathy needs to be understood more clearly and precisely than it is at the present time. Therefore, continued research examining empathy as a strength and the conditions under which it is most beneficial is warranted.

Limitations

The results of this scoping review should be considered along with the study’s limitations. First, although one study used an experimental design (Gray and Rodrigue 2001), one study used a longitudinal design (de Wied et al. 2007), and one study measured variables at two time-points (Jugert et al. 2013), the majority of the included studies utilized cross-sectional designs that cannot analyze relationships over time or provide evidence of cause and effect. As mentioned, future studies are needed to clarify the temporal pattern of the relationship between empathy and positive peer functioning variables.

Second, this review is limited by some of the exclusion criteria. For example, studies that did not measure empathy with a questionnaire were excluded in order to more readily make comparisons between study findings and to narrow the scope of the review to a manageable number of articles. Thus, future review studies could examine how peer relationships relate to empathy when empathy is measured using other methods. Qualitative studies were also excluded from this review as the aim was to synthesize results from quantitative studies. However, examining qualitative studies on empathy and positive aspects of peer relationships may provide more detailed information on adolescents’ individual experiences of their own and their friends’ empathy and how they perceive empathy to relate to variables such as peer attachment, social status, and friendship quality or closeness. Such qualitative studies could help to elucidate whether or not adolescents value empathic qualities and view empathy as a strength or not.

Third, this review sought to provide an overview of recent literature on how empathy and peer relationships relate by summarizing studies and guiding future research. For this reason as well as the state of the current literature, a narrative scoping review was believed to be more appropriate than a meta-analysis. Therefore, the effect sizes of the overall relationships between variables could not be determined. Conducting a meta-analysis of the association between peer relationships and empathy could be a valuable pursuit for future research now that a broad overview of this research has been generated as it could provide a more definitive summary of how these variables relate to one another. Fourth, as this was a scoping review, the quality of the included studies was not examined.

The results of this review contribute to some final suggestions for future research. Since this review showed that the connection between peer relationships and empathy varies depending on gender and the type of empathy examined, future studies exploring these relationships should measure cognitive and affective empathy separately and also consider gender differences in their analyses.

Conclusion

The 28 studies included in this scoping review often showed either a positive relationship or no relationship between empathy and positive peer relationship variables. The varied results depended on the type of empathy measured (i.e., cognitive or affective) and gender. For example, cognitive empathy was generally not significantly associated with peer acceptance/likeability/social preference, although affective empathy was positively associated with these variables in four studies, negatively related in one study, and not related in four studies. Popularity and empathy were not significantly associated in several studies so it appears that empathy and popularity do not tend to relate to one another. Friendship quality or closeness and peer attachment generally showed positive associations with empathy. Therefore, increased empathy relates to greater friendship quality or closeness and peer attachment. A larger number of articles supported a relationship between friendship quality or closeness and empathy compared to those supporting the relationship between peer attachment and empathy, leading to greater confidence in the former relationship. Friendship quality or closeness and peer attachment are important aspects of peer relationships. Their association with empathy speaks to the potential value of including empathy-promoting programming in schools. Counsellors working with youth on building positive peer relationships may also consider the role of empathy. For example, helping adolescents learn how to understand and address their peers’ thoughts and feelings could potentially help to promote more positive peer relationships. However, as previously stated, future research is needed to elucidate the direction of the relationship between empathy and peer attachment and friendship quality or closeness. A meta-analysis of the association between peer relationships and empathy would also be a valuable endeavour for future research.

Overall, the current review suggests empathy is not automatically or simplistically associated with positive peer relationships. Similarly, the present literature does not support the conceptualization of empathy as a robust strength in interpersonal functioning. Continued research is needed on when and how empathy does or does not make a positive contribution to interpersonal peer functioning among adolescents and whether adolescents view empathy as a strength. Further clarifying how cognitive and affective empathy relate to particular aspects of positive peer functioning would help to inform the expanding empathy intervention literature, within a positive psychology framework.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Arnett, J. J. (2010). Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A cultural approach (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Barr, J. J., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2007). Adolescent empathy and prosocial behavior in the multidimensional context of school culture. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168(3), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.168.3.231-250.

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3(1), 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x.

Brown, B.B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R.M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds), Handbook of adolescent psychology, volume 2: contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd edn., pp. 74–103). John Wiley & Sons.

Buffone, A. E., & Poulin, M. J. (2014). Empathy, target distress, and neurohormone genes interact to predict aggression for others–even without provocation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(11), 1406–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214549320.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: the development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(3), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407594113011.

Caravita, S., Di Blasio, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Social Development, 18(1), 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00465.x.

Caravita, S. C., Di Blasio, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Early adolescents’ participation in bullying: is ToM involved? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(1), 138–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609342983.

Cavojova, V., Belovicova, Z., & Sirota, M. (2011). Mindreading and empathy as predictors of prosocial behavior. Studia Psychologica, 53(4), 351–362.

Chow, C. M., Ruhl, H., & Buhrmester, D. (2013). The mediating role of interpersonal competence between adolescents’ empathy and friendship quality: a dyadic approach. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.10.004.

Christov-Moore, L., Simpson, E. A., Coudé, G., Grigaityte, K., Iacoboni, M., & Ferrari, P. F. (2014). Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 46(4), 604–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001.

Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., Sahdra, B. K., Kashdan, T. B., Kiuru, N., & Conigrave, J. (2017). When empathy matters: the role of sex and empathy in close friendships. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12255.

Cillessen, A. H. N. & Marks, P. E. L. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring popularity. In A. H. N. Cillessen, D. Schwartz, & L. Mayeux (Eds), Popularity in the peer system (pp. 25–56). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(4), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113.

de Bruyn, E. H., Cillessen, A. H., & Wissink, I. B. (2010). Associations of peer acceptance and perceived popularity with bullying and victimization in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(4), 543–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609340517.

de Wied, M., Branje, S. J., & Meeus, W. H. (2007). Empathy and conflict resolution in friendship relations among adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 33(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20166.

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1990). Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 131–149.

Estévez López, E., Jiménez, T. I., & Cava, M. J. (2016). A cross-cultural study in Spain and Mexico on school aggression in adolescence: examining the role of individual, family, and school variables. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(2), 123–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397115625637.

Estévez López, E., Pérez, S. M., Ochoa, G. M., & Ruiz, D. M. (2008). Adolescent aggression: effects of gender and family and school environments. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.007.

Geary, D. C. (2010). Male, female: the evolution of human sex differences (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12072-000.

Gorrese, A. (2016). Peer attachment and youth internalizing problems: a meta-analysis. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9333-y.

Gorrese, A., & Ruggieri, R. (2012). Peer attachment: a meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(5), 650–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9759-6.

Gorrese, A., & Ruggieri, R. (2013). Peer attachment and self-esteem: a meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.025.

Gray, C. C., & Rodrigue, J. R. (2001). Brief report: perceptions of young adolescents about a hypothetical new peer with cancer: an analog study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26(4), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/26.4.247.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805851.

Huang, H., & Su, Y. (2014). Peer acceptance among Chinese adolescents: the role of emotional empathy, cognitive empathy and gender. International Journal of Psychology, 49(5), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12075.

Johnson, H. D., Wernli, M. A., & LaVoie, J. C. (2013). Situational, interpersonal, and intrapersonal characteristic associations with adolescent conflict forgiveness. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(3), 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2012.670672.

Jugert, P., Noack, P., & Rutland, A. (2013). Children’s cross-ethnic friendships: why are they less stable than same- ethnic friendships? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10(6), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.734136.

Laible, D. (2007). Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence: Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 1185–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.010.

Laible, D. J., Carlo, G., & Roesch, S. C. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 27(6), 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.05.005.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Llorca-Mestre, A., Samper-García, P., Malonda-Vidal, E., & Cortés-Tomás, M. T. (2017). Parenting style and peer attachment as predictors of emotional instability in children. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(4), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.5363.

Lovett, B. J., & Sheffield, R. A. (2007). Affective empathy deficits in aggressive children and adolescents: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.03.003.

Malti, T., Chaparro, M. P., Zuffianò, A., & Colasante, T. (2016). School-based interventions to promote empathy-related responding in children and adolescents: a developmental analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1121822.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282.

McMahon, S. D., Wernsman, J., & Parnes, A. L. (2006). Understanding prosocial behavior: the impact of empathy and gender among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(1), 135–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.008.

Meuwese, R., Cillessen, A. H., & Güroğlu, B. (2017). Friends in high places: a dyadic perspective on peer status as predictor of friendship quality and the mediating role of empathy and prosocial behavior. Social Development, 26(3), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12213.

Nangle, D. W., Erdley, C. A., Newman, J. E., Mason, C. A., & Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: interactive influences on children’s loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(4), 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7.

Naylor, J. M. (2011). Peer relationships. In S. Goldstein & J. A. Naglieri (Eds), Encyclopedia of child behavior and development (pp. 1075–1076). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2098.

Oberle, E., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Thomson, K. C. (2010). Understanding the link between social and emotional well-being and peer relations in early adolescence: gender-specific predictors of peer acceptance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(11), 1330–1342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9486-9.

Overgaauw, S., Rieffe, C., Broekhof, E., Crone, E. A., & Güroğlu, B. (2017). Assessing empathy across childhood and adolescence: validation of the Empathy Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (EmQue-CA). Frontiers in Psychology, 8(870), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00870.

Poorthuis, A. M. G., Thomaes, S., Denissen, J. J. A., van Aken, M. A. G., & Orobio de Castro, B. (2012). Prosocial tendencies predict friendship quality, but not for popular children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112(4), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.04.002.

Poulin, F., Dishion, T. J., & Haas, E. (1999). The peer influence paradox: relationship quality and deviancy training within male adolescent friendships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(1), 42–61.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? The interplay between personal and social factors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(2), 143–163.

Rawana, E. P., & Brownlee, K. (2009). Making the possible probable: a strength-based assessment and intervention framework for clinical work with parents, children and adolescents. Families in Society, 90(3), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3900.

Reniers, R. L., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M., & Völlm, B. A. (2011). The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528484.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Rose, A. J., & Smith, R. L. (2009). Sex differences in peer relationships. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 379–393). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rubin, K. H., Dwyer, K. M., Booth-LaForce, C., Kim, A. H., Burgess, K. B., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (2004). Attachment, friendship, and psychosocial functioning in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(4), 326–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431604268530.

Sahdra, B. K., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., Marshall, S., & Heaven, P. (2015). Empathy and nonattachment independently predict peer nominations of prosocial behavior of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(263), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00263.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.5.

Singer, T., & Klimecki, O. M. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Current Biology, 24(18), R875–R878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054.

Smith, R. L. (2015). Adolescents’ emotional engagement in friends’ problems and joys: associations of empathetic distress and empathetic joy with friendship quality, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.020.

Smith, R. L., & Rose, A. J. (2011). The “cost of caring” in youths’ friendships: considering associations among social perspective taking, co-rumination, and empathetic distress. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1792–1803. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025309.

Soenens, B., Duriez, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Goossens, L. (2007). The intergenerational transmission of empathy-related responding in adolescence: the role of maternal support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206296300.

Spreng, R. N., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381.

Tan, E., Zou, Y., He, J., & Huang, M. (2011). Empathy and subjective well-being: emotion regulation as a mediator. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19(5), 672–674.

van Noorden, T. H., Haselager, G. J., Cillessen, A. H., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(3), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0135-6.

Vinayak, S., & Judge, J. (2018). Resilience and empathy as predictors of psychological wellbeing among adolescents. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 8(4), 192–200.

Wentzel, K. R., Filisetti, L., & Looney, L. (2007). Adolescent prosocial behavior: the role of self-processes and contextual cues. Child Development, 78(3), 895–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01039.x.

Wilkinson, R. B. (2004). The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(6), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20.

Wölfer, R., Cortina, K. S., & Baumert, J. (2012). Embeddedness and empathy: how the social network shapes adolescents’ social understanding. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1295–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.015.

You, S., & Kim, A. Y. (2016). Understanding aggression through attachment and social emotional competence in Korean middle school students. School Psychology International, 37(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316631039.

You, S., Lee, J., Lee, Y., & Kim, A. Y. (2015). Bullying among Korean adolescents: the role of empathy and attachment. Psychology in the Schools, 52(6), 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21842.

Zorza, J. P., Marino, J., de Lemus, S., & Mesas, A. A. (2013). Academic performance and social competence of adolescents: predictions based on effortful control and empathy. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16(e87), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.8.

Zorza, J. P., Marino, J., & Mesas, A. A. (2015). The influence of effortful control and empathy on perception of school climate. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0261-x.

Author Contributions

E.P.: Collaborated in designing the manuscript, co-conducting the review, and writing sections of the paper. S.P.: Collaborated in designing the manuscript, co-conducting the review, and writing sections of the paper. B.P.: Collaborated in co-conducting the review and writing sections of the paper. E.R.: Collaborated in designing the manuscript, provided feedback throughout the duration of the reviewing and writing process, and collaborated in editing manuscript drafts. K.B.: Collaborated in writing and editing manuscript drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Portt, E., Person, S., Person, B. et al. Empathy and Positive Aspects of Adolescent Peer Relationships: a Scoping Review. J Child Fam Stud 29, 2416–2433 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01753-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01753-x