Abstract

Objectives

Parents’ knowledge of children’s activities, friends and whereabouts is widely recognized as a promotive factor for adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment. As previous research showed, this knowledge mainly depends on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information about their daily lives. Parents can actively encourage adolescents’ disclosure by initiating conversations. However, such parental solicitation for information may be perceived as intrusive, and ironically lead to more concealment. In the present study, we examined whether and under which conditions parental solicitation for information is related to adolescents’ information management, thereby examining whether adolescents’ perceptions of an autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting context moderated these associations.

Methods

351 Swiss adolescents (45.6% girls; mean age = 15.01 years) completed self-report questionnaires about their mother and their father separately.

Results

Generally, parental solicitation for information was statistically significantly associated with greater disclosure. Further, perceived autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting altered some of the links between solicitation for information and adolescents’ information management strategies. Specifically, for both mothers and fathers, parental solicitation for information was respectively associated with more lies at low levels of autonomy support, and with fewer lies at high levels of autonomy support. We also found, for fathers only, that parental solicitation for information was associated with less secrecy at low levels of autonomy support.

Conclusions

These findings underscore that the general parenting context in which parents solicit for information has implications for adolescents’ information management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parents’ knowledge of children’s activities, friends and whereabouts is widely recognized as a promotive factor for adolescent psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Abar et al. 2017; Criss et al. 2015; Hamza and Willoughby 2011). Since Stattin and Kerr’s (2000; Kerr and Stattin 2000) pioneering work, a large body of research confirmed that this knowledge mainly depends on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information about their daily lives, rather than on parents’ monitoring practices (e.g., Crouter et al. 2005; Keijsers et al. 2010; Kerr et al. 2010). According to Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory (Petronio 2002, 2010), adolescents manage the information they communicate to their parents through a variety of strategies (e.g., by sharing information, by keeping secrets, or by lying) in order to regulate their privacy (Finkenauer et al. 2008). Moreover, adolescents’ disclosure has been consistently related to a better psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Kerr and Stattin 2000; Willoughby and Hamza 2011), whereas the opposite pattern was typically found for adolescents’ secrecy and lying (e.g., Frijns et al. 2005; Smetana et al. 2009).

Given that adolescent disclosure is the primary source of parental knowledge and a protective factor for adjustment, parents may reason that it is essential to encourage their child to open up about their daily lives. Some authors suggested that parents’ monitoring practices, such as asking questions (often labeled parental solicitation), and adolescents’ disclosure relate to one other, showing for instance that greater parental solicitation for information was associated with greater adolescents’ disclosure (e.g., Hamza and Willoughby 2011). However, other studies found that adolescents sometimes perceive parents’ solicitations as invasive, which may then lead to negative reactions both emotionally (e.g., feeling of being controlled; Kapetanovic et al. 2017; Laird et al. 2018) and behaviorally (e.g., keeping secrets; Hawk et al. 2008, 2013). According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan 2000), the effectiveness of specific parental practices would depend upon the degree to which these practices are embedded in a context of autonomy-supportive parenting (i.e., supporting a child's volitional function; Grolnick and Pomerantz 2009; Joussemet et al. 2008).

During adolescence, youngsters increasingly spend time with their peers and outside their parents’ direct supervision (Lam et al. 2014; Larson et al. 1996). This offers them the opportunity to actively regulate their parents’ knowledge, by deciding what information they disclose or conceal from their parents about their friends and activities, and by acting accordingly (i.e., information management process; Tilton-Weaver and Marshall 2008). According to CPM theory (Petronio 2002, 2010), when deciding whether to reveal or conceal information, people have to balance two paradoxical needs: a need for intimacy, which involves the need to feel connected to others such as family members, and which may be achieved through sharing private information, and a need for privacy, which involves the need to retain a sense of individuality, and which may be achieved through restricting access to private information (Petronio 1991, 2002, 2010). As children enter adolescence, they re-evaluate their conceptions of the legitimacy of their parents’ authority in their life (Smetana 2011), and they seek to expand the boundaries of what they consider as personal (Petronio 2002; Smetana 2018; Youniss and Smollar 1985). At the same time, adolescents try to maintain close relationships and strong bonds with their parents, who remain a major source of influence for their development (Finkenauer et al. 2008, 2009). In line with CPM (Petronio 2002, 2010), adolescents may regulate those boundaries and assert their privacy, while remaining connected with their parents (i.e., intimacy), through the use of different information management strategies (Finkenauer et al. 2008; Guerrero and Afifi 1995).

Research has generally shown that adolescents use a variety of strategies to manage information (e.g., Cumsille et al. 2010; Marshall et al. 2005). Routine disclosure refers to adolescents’ willingness to provide information to their parents about their free time away from home, including their unsupervised activities, friends and whereabouts (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2013). Adolescents also use distinct strategies of concealment, such as keeping secrets, when they intentionally conceal information from their parents in order to keep it private (Afifi et al. 2007; Frijns and Finkenauer 2009), or lying, when they deliberately provide incorrect information to their parents in order to deceive them (Marshall et al. 2005; Tilton-Weaver and Marshall 2008). Despite the assumption that teens’ increasing concealment of information would be developmentally normative during adolescence, as it would involve a way to gain more independence (e.g., Keijsers et al. 2009; Keijsers and Poulin 2013), the use of secrecy and lies has been consistently related to negative outcomes, not only in terms of adolescents’ adjustment, but also in terms of the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., Finkenauer et al. 2005; Goldstein 2016). By contrast, adolescents’ disclosure has been consistently associated with psychological adjustment, and with better relationships with the parents (e.g., Jiménez-Iglesias et al. 2013; Smetana et al. 2009). It seems therefore important for parents to foster communication with their children by, for example, asking questions (e.g., Hamza and Willoughby 2011) and by considering the child’s feelings and thoughts when communicating with him/her (i.e., autonomy-supportive parenting; Mageau et al. 2017).

“What did you do last night and with whom were you…?” are types of parental questions quite common in an attempt to encourage adolescents to communicate information about their friends, activities and whereabouts, and to obtain knowledge of their children’s daily life away from home. Adolescents could perceive such parental solicitation in a positive way, as it could reflect a parent’s interest in their child’s life. Hence, when parents initiate more frequently direct conversations, adolescents might disclose more information and, by doing so, try to maintain a close relationship with their parents. However, inconsistent findings exist in the literature. On the one hand, some studies showed parental solicitation for information to be associated with greater adolescents’ disclosure (e.g., Cottrell et al. 2017; Hamza and Willoughby 2011; Stavrinides et al. 2010; Willoughby and Hamza 2011). On the other hand, other studies indicated that parental solicitation for information was not statistically significantly related to adolescents’ disclosure (e.g., Garthe et al. 2018; Keijsers et al. 2010; Kerr et al. 2010; Tilton-Weaver 2014).

Regarding the link between parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ strategies of concealment (i.e., secrecy and lying), the literature is scarce and the interpretation of results equivocal as well. One reason for this is that some of the above-mentioned studies operationalized disclosure and secrecy as opposite sides of a unidimensional construct (e.g., Garthe et al. 2018; Kerr et al. 2010; Stavrinides et al. 2010), whereas in fact these two strategies should be studied as related but distinct constructs (Finkenauer et al. 2002; Frijns et al. 2010). In addition, the majority of studies on adolescents’ information management omitted other information management strategies (e.g., lying). The few available studies on the association between parental solicitation for information and the strategies of concealment suggest that soliciting information may ironically lead to more secrecy from the adolescents. The results of Villalobos Solís et al. (2015) indicated in fact that when mothers ask more often about their children’s unsupervised life, their adolescents disclosed more, but surprisingly, also kept more secrets from them. Furthermore, Hawk et al. (2008) found that parental solicitation for information longitudinally predicted increases in adolescents’ perceptions of parental privacy invasion. Such perceptions of privacy invasion have been found to predict higher levels of secrecy (Hawk et al. 2013), suggesting that parents’ active efforts to initiate conversations can be counterproductive and may promote greater secrecy when perceived as intrusive by the adolescents.

Overall, these results suggest that when parents solicit for information, adolescents may perceive and interpret this practice either as a sign of caring or as an intrusion in their private life (Bakken and Brown 2010; Laird et al. 2018). Previous research suggests that this may, in part, depend upon adolescents’ beliefs about the legitimacy of parental authority, namely “the extent to which parents’ assertion of control over an area is believed to be a natural or an appropriate extension of their role as parents” (Darling et al. 2008, p. 1103). Indeed, past research showed that adolescents’ willingness to disclose information is related to their own beliefs about the legitimacy of parental authority with, for instance, adolescents concealing more information when they endorse less parental legitimacy (Cumsille et al. 2010). Moreover, among adolescents who more strongly endorsed the legitimacy of their parents’ authority, parental solicitation for information predicted less secrecy over time (Keijsers and Laird 2014). Herein, we aim to extend this literature, by examining the role of perceived parental autonomy support in the associations between parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ information management. Indeed, previous research indicates that the general parenting context plays an important role in shaping adolescents’ beliefs about parental authority with, for instance, an autonomy-supportive parenting context being related to greater legitimacy perceptions (see Graça et al. 2013, in an education context; Van Petegem et al. 2017).

According to SDT (Deci and Ryan 2000), an autonomy-supportive family context is considered the ideal for promoting positive adolescent development (Joussemet et al. 2008). Autonomy-supportive parents encourage their adolescents to act upon personally endorsed values, objectives and interests by, for example, offering choice whenever possible, by taking adolescents’ perspective into account, and by providing an explanation when choices are limited (Deci et al. 1994; Soenens et al. 2007). By contrast, controlling parents use pressure and intrusion to force the child to behave, think and feel in parent-imposed ways, for instance by making use of threats of punishment, guilt induction, and performance pressures (Barber 1996; Grolnick and Pomerantz 2009; Soenens and Vansteenkiste 2010). Autonomy-supportive and controlling parenting are often considered as the opposite poles of a single dimension (Soenens and Vansteenkiste 2010; Soenens et al. 2009).

In line with SDT, there exists quite some research indicating that autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting has implications for adolescents’ information management. Specifically, autonomy-supportive parenting has been described facilitating adolescents’ disclosure (e.g., Bureau and Mageau 2014; Roth et al. 2009). For instance, Mageau et al. (2017) found that mothers who reported more autonomy support have children who disclosed more information about activities and whereabouts away from home. Similarly, using an observational methodology, Wuyts et al. (2018) showed that maternal autonomy support, as observed in a 10-min conversation about friendships, was related to more disclosure about friends. Conversely, controlling parenting has been found to relate to less disclosure (e.g., Soenens et al. 2006; Urry et al. 2011) and more secrecy (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that adolescents feel freer to disclose information within an autonomy-supportive parenting context. Moreover, as argued below, perceived autonomy-supportive parenting may potentially moderate the link between parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ strategies of information management.

Although no study to date directly tested the moderating role of autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting in the link between parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ information management, there is indirect evidence suggesting that the relationship between parents’ monitoring behaviors and adolescents’ responses partly depends upon the context within which such practices occur, confirming SDT’s propositions (Grolnick and Pomerantz 2009; Joussemet et al. 2008). For instance, one study (LaFleur et al. 2016) examined the moderating role of the broader parent–child context (i.e., parental warmth and adolescents’ legitimacy beliefs) in the relation between parents’ monitoring behaviors (including solicitation for information) and adolescents’ emotional reaction (i.e., feelings of being controlled and invaded). The results indicated that more parental monitoring was associated with more negative reactions at low levels of parental warmth and at low levels of perceived legitimacy. Further, there is also some research suggesting that autonomy-supportive parenting plays a role in understanding the effectiveness of other parenting practices, such as parental rule-setting. For instance, recent studies indicated that adolescents’ interpretations of and responses to parents’ rule-setting is predicted by parents’ (autonomy-supportive vs. controlling) communication style (Baudat et al. 2017; Van Petegem et al. 2015), as well as by a general autonomy-supportive parenting context (Van Petegem et al. 2017). Together, these findings suggest that the general parenting context in which parental solicitation for information occurs may be crucial for understanding if adolescents will be more likely to disclose or rather conceal information.

In the present cross-sectional study, we examined how perceived parental solicitation for information related to different forms of adolescents’ information management (i.e., disclosure, secrecy, lying), and tested whether these associations were moderated by adolescents’ perception of autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting. First, we tested whether solicitation for information was associated with disclosure, secrecy and lies. Moreover, on the basis of both CPM (Petronio 2002) and SDT (Deci and Ryan 2000), we tested whether perceptions of autonomy-supportive parenting would moderate the relations between parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ use of disclosure, secrecy and lies. That is, we expected that higher levels of parental solicitation for information would relate to more disclosure, less secrecy and less lies when autonomy-supportive parenting is high. Conversely, when autonomy-supportive parenting is low, higher levels of solicitation would be associated with less disclosure, more secrecy and more lies.

Given that past research has demonstrated mean-level differences in adolescent and parental gender for some of our variables, we asked participants to complete questionnaires about their mothers and their fathers, and we examined the role of gender. Specifically, several studies indicated gender differences in information management with, for instance, girls reporting more disclosure, in particular to mothers (e.g., Finkenauer et al. 2002; Keijsers et al. 2010; e.g., Soenens et al. 2006), and boys scoring higher on secrecy (e.g., Keijsers et al. 2010) and on lies (e.g., Jensen et al. 2004), regardless of the parent’s gender. Girls and boys also differ in the way they perceive their parents’ rearing style, with, for instance, girls reporting more parental solicitation for information and more paternal controlling parenting, whereas boys scoring higher on maternal controlling parenting (e.g., Kerr and Stattin 2000; Soenens et al. 2008).

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 351 adolescents (45.6% female) in their last year of mandatory school (i.e., 9th grade) in Switzerland (mean age = 15.01; SD = 0.72). Of our participants, 54.2% followed a general-oriented education and 45.8% followed an academic-oriented education. The majority of the participants were Swiss citizens (68%) or from other European countries (24.4%). Most of them (70.4%) came from an intact family (i.e., biological parents who live together). When comparing their family's financial situation to other families, 62.6% perceived their personal situation as average, 29% perceived it as below, and 8.4% perceived it as above.

Procedure

The study was conducted in compliance with the Ethics Code of the Swiss Psychological Society (SPS). Participants were recruited in three public schools of a canton of the French-speaking part of Switzerland. The School and Youth department of the canton authorized the execution of our study. Among the schools they allowed us to contact, we selected one urban school, one semi-urban school and one rural school. All adolescents participated on a voluntary basis and were free to withdraw from the study at any time. A few days prior to the survey, adolescents and their parents were informed about the purpose of the study and about the confidential treatment of the data. An oral consent was obtained from the adolescents in classrooms and a passive informed consent was required from parents, which involved asking the parents to fill out a form if they did not want their child to participate in the study. Of the 449 families contacted, 71 declined to participate and 27 adolescents were absent during the recruiting day (e.g., illness, training course outside school), resulting in a response rate of 78%. We asked adolescents to complete a set of self-report questionnaires during a class period, under the supervision of the first author and one graduate student.

Measures

Questionnaires were either already available in French or were translated through a back-translation procedure. Participants completed a set of self-report questionnaires about their mother and their father, separately. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Parental solicitation for information

We measured perceived parental solicitation for information with the Parental Solicitation scale (Stattin and Kerr 2000; Stattin et al. 2010). The original scale consists of five items, which evaluate how often parents ask children, children’s friends or friends’ parents about their unsupervised activities. As our goal was to evaluate how often parents’ initiate direct conversations with their adolescents, we omitted the two items assessing parents’ inquiries to other persons than their children. In line with past research (Hawk et al. 2008), the three final items that measured parents’ solicitation for information from the child were therefore (a) “During the past month, how often have your parents started a conversation with you about your free time?”; (b) “How often do your parents initiate a conversation about things that happened during a normal day at school?”; (c) “Do your parents usually ask you to talk about things that happened during your free time (whom you met when you were out in the city, free time activities, etc.)?”. In line with previous research (Hawk et al. 2008), this measure demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, ωt = 0.64, 95% CI [0.57, 0.71] and ωt = 0.71, 95% CI [0.65, 0.77], for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting

We assessed perceived autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting through the French version of the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS; Mageau et al. 2015). The P-PASS consists of two subscales counting 24 items. The autonomy-supportive subscale (12 items) assesses the provision of choice within certain limits (4 items; e.g., “Within certain limits, my parents allow me the freedom to choose my own activities”), the provision of rationale for demands and limits (4 items; e.g., “When my parents ask me to do something, they explain why they want me to do it”), and the acknowledgment of adolescents’ feelings (4 items; e.g., “My parents listen to my opinion and point of view when I disagree with them”). The controlling parenting subscale (12 items) assesses parents’ threats with punishments (4 items; e.g., “When my parents want me to do something, I have to obey or else I am punished”), guilt induction (4 items; e.g., “My parents make me feel guilty for anything and everything”), and performance pressures (4 items; e.g., “In order for my parents to be proud of me, I have to be the best”). Past research often found highly negative correlations between autonomy-supportive and controlling parenting, supporting the idea that these two dimensions represent two ends of a same theoretical continuum (e.g., Moreau and Mageau 2012; Soenens et al. 2007). In line with this, the correlations between these two subscales were also quite high and negative in our study (mothers: r = −0.57, p < 0.001, fathers: r = −0.59, p < 0.001). Therefore, similar to previous studies (e.g., Moreau and Mageau 2012; Soenens et al. 2009), we combined the two scales into a single dimension reflecting parents’ degree of autonomy-supportive versus controlling parenting. This was done by reverse-coding the items of the controlling parenting subscale, and averaging them with the items of the autonomy-supportive subscale. High scores reflect high levels of autonomy-supportive parenting (and low levels of controlling parenting), and low scores reflect low levels of autonomy-supportive parenting (and high levels of controlling parenting). In our study, this measure demonstrated an excellent internal consistency, ωt = 0.91, 95% CI [0.90, 0.93], and ωt = 0.92, 95% CI [0.90, 0.93], for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Adolescents’ information management

We evaluated three strategies of adolescents’ information management: disclosure, secrecy and lies. Both disclosure and secrecy were assessed with the Child Disclosure scale (Frijns et al. 2010; Stattin and Kerr 2000), and lies were measured through an adapted version of a 12-item questionnaire developed by Engels et al. (2006). The 3-item disclosure scale evaluated the degree to which adolescents disclose information to their parents (e.g., “I spontaneously tell my parents about my friends [which friends I hang out with and how they think and feel about various things]”). In line with previous research (Keijsers et al. 2009), this scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, ωt = 0.61, 95% CI [0.54, 0.69], and ωt = 0.64, 95% CI [0.56, 0.71], for mothers and fathers, respectively. The 2-item secrecy scale evaluated the degree to which adolescents intentionally withhold information from their parents (e.g., “I keep much of what I do in my free time secret from my parents”). Similar to previous studies (Keijsers and Poulin 2013), this scale had an acceptable internal consistency (ωt = 0.64, 95% CI [0.55, 0.73], and ωt = 0.65, 95% CI [0.56, 0.74], for mothers and fathers, respectively). Finally, the lying scale evaluated three aspects of adolescents’ lying behaviors: (a) outright lies (4 items; e.g., “I lie to my parents about the things that I am engaged in”); (b) exaggerations (4 items; e.g., “I picture things better than they actually are to my parents”); (c) subtle lies (4 items; e.g., “I tell white lies to my parents”). In line with Engels et al. (2006), this measure demonstrated good internal consistency, ωt = 0.86, 95% CI [0.84, 0.88], and ωt = 0.87, 95% CI [0.85, 0.89], for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Data Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Version 3.4.2; R Core Team 2017). Some participants did not complete the questionnaires for their mothers or their fathers, and therefore were removed from the analyses with the maternal or paternal variables. In other words, for all analyses with the maternal variables of interest, we removed the participants who did not complete the questionnaire for their mothers (n = 2). We did the same for the analyses with the paternal variables (n = 17). This led us to use two different datasets, one for each parental figure (Nmothers = 349; Nfathers = 334). In mothers’ and fathers’ datasets, there were 2.95% and 3.33% missing data, respectively. Little’s MCAR-test yielded a statistically nonsignificant result in both sub-datasets, indicating that missing values were likely to be missing at random, χ²(2397) = 2480.95, p = 0.113 and χ²(2738) = 2853.45, p = 0.061, for mothers and fathers, respectively. To deal with missing data, we used the regularized iterative Principal Components Analysis (PCA) algorithm described by Josse and Husson (2012, 2016). This method has the advantage of imputing missing values by taking into account the similarities between individuals as well as the links between variables. We applied this procedure for each of the scales in both mothers’ and fathers’ sample.

First, we conducted data screening for normality. Specifically, as our sample size was quite large, we inspected the values of the skewness and kurtosis (Field 2013; Kline 2016). We also inspected outliers using robust methods: the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) for univariate outliers (Leys et al. 2013), and the Mahalanobis-Minimum Covariance Determinant (MMCD) for multivariate outliers (Leys et al. 2018). Then, we performed robust multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA; Todorov and Filzmoser 2010), for the maternal and paternal variables separately, to examine if there were mean-level differences between girls and boys in terms of perceived maternal and paternal autonomy-supportive parenting and parental solicitation for information, and strategies of information management used with their mothers and fathers. We also tested if there were mean-level differences as a function of family structure and perceived financial situation in terms of autonomy-supportive parenting, parental solicitation for information and strategies of information management.

Second, as primary analyses, we tested for the main effects and interaction effects between perceived parental solicitation for information and autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting on adolescents’ strategies of information management, controlling for adolescent gender. This was done by using a latent variable approach, as such an approach has the advantage of reducing measurement errors (Marsh et al. 2013). Prior to estimating our hypothesized model, we reduced the numbers of indicators per latent construct through the use of four parcels for both autonomy support and lies. Specifically, using a domain-representative approach, we created each parcel by joining one item from each of their respective subscale into item sets (see Little et al. 2002). For example, as the lying scale comprised three dimensions (A, B and C), each measured by four items (e.g., A1 through A4), the first parcel contained items A1, B1, C1, the second parcel consisted of items A2, B2, C2, the third parcel consisted of A3, B3, C3, and the fourth parcel contained A4, B4, C4. Then, we tested a measurement model and inspected correlations among latent variables.

In the next step, we examined the main effects of perceived parental solicitation for information and autonomy support on adolescents’ information management using structural equation modeling (SEM). In a next step, we used latent moderated SEM based on residual centering (Little et al. 2006) to test our hypothetical interaction model (Fig. 1). Following the recommendations by Foldnes and Hagtvet (2014), we created orthogonalized indicators of our latent interaction construct, by calculating each possible product term from the two sets of indicators of the main effect latent variables (i.e., parental solicitation for information and autonomy-supportive parenting), which resulted in twelve orthogonalized product terms. These orthogonalized product terms were included as indicators of our latent interaction construct. The residual variances of the interaction indicators were specified, and the latent interaction construct was not allowed to correlate with the main effect latent constructs. We used the following goodness-of-fit indices to assess models fit: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values are interpreted to represent a good fit when CFI is greater than 0.95, RMSEA is lower than 0.06, and SRMR is lower than 0.08 (Hu and Bentler 1999). Finally, when an interaction was statistically significant, we conducted simple slope analyses to evaluate whether slopes were statistically significantly different from zero at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of autonomy-supportive parenting (Cohen et al. 2003; Dawson 2014). Data analyses for each parent were conducted separately, which resulted in two separated models.

The latent interaction model of perceived parental solicitation for information and autonomy support on adolescents’ strategies of information management, using orthogonalized indicators. x1 to x3 are indicators of parental solicitation, z1 to z4 are indicators of general autonomy support, y1 to y9 are indicators of information management strategies, x1z1 to x3z4 are orthogonalized indicators of the latent variable interaction. For reasons of clarity, we did not present the effects of adolescents’ gender, nor the intercorrelations between indicators are depicted

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics of study variables are presented in Table 1. Regarding data screening, the Fisher’s coefficients of skewness and kurtosis fell within the acceptable boundaries of ±1.96 (Field 2013), suggesting that the distribution is not statistically significantly different from a normal distribution. Results of the MAD and MMCD analyses indicated the presence of univariate outliers in several maternal (i.e., autonomy support, secrecy and lies) and paternal (i.e., autonomy support, secrecy and lies) dimensions, as well as multivariate outliers.

A robust MANOVA revealed a statistically significant multivariate effect of adolescent gender on the maternal variables of interest, Λ = 0.92, χ2(5) = 29.29, p < 0.001. In line with previous research, subsequent univariate analyses revealed that girls reported more disclosure to their mother (M = 3.81, 95% CI [3.67, 3.94], SD = 0.85) than did boys (M = 3.46, 95% CI [3.34, 3.58], SD = 0.87), F(1, 347) = 13.77, p = 0.001, ω² = 0.035. Boys reported more lies to their mother (M = 2.20, 95% CI [2.11, 2.30], SD = 0.67) than did girls (M = 2.03, 95% CI [1.93, 2.14], SD = 0.70), F(1, 347) = 5.52, p = 0.048, ω² = 0.013. We did not find a statistically significant multivariate effect of neither family structure nor perceived financial situation on the maternal variables of interest, Λ = 0.98, χ2(5) = 5.94, p = 0.312 and Λ = 0.97, χ2(10) = 9.69, p = 0.468, respectively. In addition, a statistically significant multivariate effect of adolescent gender on the paternal variables of interest was also found, Λ = 0.94, χ2(5) = 20.92, p < 0.001. Subsequent univariate analyses revealed that boys perceived higher levels of solicitation from their fathers (M = 2.96, 95% CI [2.82, 3.09], SD = 0.92), than did girls (M = 2.63, 95% CI [2.47, 2.80], SD = 1.01), F(1, 332) = 9.38, p = 0.012, ω² = 0.024. We did not find a statistically significant multivariate effect of neither family structure nor perceived financial situation on the paternal variables of interest, Λ = 0.99, χ2(5) = 2.77, p = 0.736 and Λ = 0.97, χ2(10) = 8.07, p = 0.622, respectively. Given these findings, we controlled for the role of gender in our subsequent models.

Primary Analyses

Structural equation modeling was used to examine the main and interaction effects of perceived parental solicitation for information and autonomy-supportive parenting on adolescents’ information management strategies. We used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and the Satorra–Bentler scaled test statistic. Because of the high correlations between parental solicitation and disclosure (r = 0.70, p < 0.001 and r = 0.88, p < 0.001, for mothers and fathers, respectively), as well as between secrecy and lies (r = 0.87, p < 0.001 and r = 0.78, p < 0.001, for mothers and fathers, respectively), we tested for discriminant validity between these constructs, using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT; Henseler et al. 2015). Results of the HTMT analyses are interpreted according to predefined thresholds of 0.85 or 0.90, with values below these criteria indicating discriminant validity. As shown in Table 2, results of the HTMT analyses provided evidence for discriminant validity among maternal constructs according to the 0.85 and 0.90 criteria. Similarly, all HTMT values between paternal constructs were below 0.85, except for one pair of variables (solicitation and disclosure), which violated both 0.85 and 0.90 criteria. Therefore, we handled this problem of discriminant validity by increasing the constructs’ average monotrait-heteromethod correlations, which is done by removing items that show low correlations with other items measuring the same construct (Henseler et al. 2015). Therefore, we inspected correlations among the disclosure items and removed the item which showed low correlations with the other items (r = 0.30 and r = 0.33), which is the item “If I went out at night, when I get home, I tell my parents where I went and with whom”. Then, we re-evaluated the discriminant validity between paternal solicitation and disclosure to fathers, with resulted in HTMT values below 0.85, which indicates discriminant validity between the two constructs.

Regarding the mother–adolescent model, the measurement model yielded a good fit, χ²(94) = 130.19, p = 0.008, robust CFI = 0.98, robust RMSEA = 0.037 [90% CI = 0.020, 0.052], SRMR = 0.044, with factor loadings for all indicators ranging between 0.48 and 0.93, p < 0.001. Similar results were found for the measurement model of the father–adolescent model, χ²(80) = 131.50, p < 0.001, robust CFI = 0.98, robust RMSEA = 0.047 [90% CI = 0.032, 0.062], SRMR = 0.040, with factor loadings ranging between 0.51 and 0.91, p < 0.001. Correlations among latent variables are presented in Table 1. Perceived parental solicitation for information was highly and positively correlated with disclosure, and negatively and moderately related to secrecy and lies. Similarly, autonomy-supportive parenting was positively correlated with disclosure, and negatively related to secrecy and lies. Evidence for strong invariance across gender was obtained in both the mother–adolescent and father–adolescent model, ΔCFI = 0.001 and ΔRMSEA = 0.000, and ΔCFI = 0.001 and ΔRMSEA = 0.001, respectively, suggesting that the measurement model is valid across adolescent gender.

We then tested the main effects of parental solicitation for information and autonomy-supportive parenting on adolescents’ disclosure, secrecy and lies, controlling for adolescents’ gender. The structural models fit the data well, χ²(107) = 152.70, p = 0.002, robust CFI = 0.98, robust RMSEA = 0.039 [90% CI = 0.023, 0.052], SRMR = 0.048, and χ²(92) = 155.22, p < 0.001, robust CFI = 0.97, robust RMSEA = 0.049 [90% CI = 0.035, 0.062], SRMR = 0.044, for the mother–adolescent model and the father–adolescent model, respectively. Regarding the mother–adolescent model (see Fig. 2), results indicated that higher levels of solicitation for information was statistically significantly associated with higher levels of disclosure. Main effects of maternal solicitation for information on adolescents’ secrecy and lying behaviors towards mothers were not statistically significant. Higher levels of maternal autonomy-supportive parenting was statistically significantly related to higher levels of disclosure, and lower levels of secrecy and lies. Regarding the father–adolescent model (see Fig. 2), results showed that paternal solicitation for information was statistically significantly associated with higher levels of disclosure and lower levels of secrecy, but not with lying behaviors. Similarly to mother–adolescent dyads, higher levels of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting was statistically significantly related to higher levels of disclosure, and lower levels of secrecy and lies.

Results of the structural equation models testing direct links between parental solicitation and autonomy support, and adolescents’ strategies of information management, controlling for adolescent gender. Standardized coefficients are reported. The first coefficient pertains to the model including adolescents’ reports of maternal variables, χ²(107) = 152.70, p = 0.002, robust CFI = 0.98, robust RMSEA = 0.039 [90% CI = 0.023, 0.052], SRMR = 0.048, the second coefficient pertains to the model including adolescents’ reports of paternal variables, χ²(92) = 155.22, p < 0.001, robust CFI = 0.97, robust RMSEA = 0.049 [90% CI = 0.035, 0.062], SRMR = 0.044. For reasons of clarity, we did not present the effects of adolescent gender. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

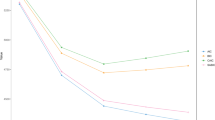

Finally, we tested for the moderating role of perceived autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting in the association between parental for information and adolescents’ strategies of information management, controlling for adolescents’ gender. In the first set of analyses, we focused on the moderating role of maternal autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting in the prediction of adolescents’ strategies of information management used with mothers (see Table 3). The mother–adolescent model yielded an excellent fit, χ2(332) = 263.77, p = 0.998, robust CFI = 1.00, robust RMSEA = 0.000 [90% CI = 0.000, 0.000], SRMR = 0.044, with factor loadings for all indicators ranging between 0.33 and 0.94, p < 0.001. We did not find evidence for a moderation effect of maternal autonomy-supportive parenting in the relationship between maternal solicitation for information and adolescents’ disclosure and secrecy. However, we found that maternal autonomy-supportive parenting moderated the relationship between maternal solicitation for information and adolescents’ lying behaviors. Subsequent simple slope analyses indicated that maternal solicitation for information was statistically significantly associated with fewer lies at high levels of mothers’ autonomy-supportive parenting, β = −0.26, z = −2.77, p = 0.006, but not at low levels of maternal autonomy-supportive parenting, β = 0.04, z = 0.44, p = 0.660 (see Fig. 3).

Two-way latent interaction effect of perceived maternal solicitation for information and maternal autonomy support on adolescents’ lying to mothers. The slope of maternal solicitation was statistically significant at high (+1 SD) levels of autonomy support, β = −0.26, p = 0.006, but not at low (−1 SD) levels of autonomy support, β = 0.04, p = 0.660

In the second set of analyses, we considered the moderating role of paternal autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting in the link between paternal solicitation for information and adolescents’ strategies of information management used with fathers (see Table 3). The father–adolescent model yielded an excellent fit, χ2(305) = 301.22, p = 0.550, robust CFI = 1.00, robust RMSEA = 0.000 [90% CI = 0.000, 0.022], SRMR = 0.038, with factor loadings for all indicators ranging between 0.48 and 0.92, p < 0.001. Similarly to the mother–adolescent model, we did not find evidence for a moderation effect of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting in the association between paternal solicitation for information and adolescents’ disclosure. However, our results indicated that autonomy-supportive parenting moderated the relationship between solicitation for information and adolescents’ secrecy with fathers. Simple slope analyses showed that paternal solicitation was statistically significantly associated with less secrecy at low levels of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting, β = −0.36, z = −3.07, p = 0.002, but not at high levels of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting, β = −0.06, z = −0.62, p = 0.535 (see Fig. 4). In other words, especially adolescents who perceived their fathers as being relatively low in solicitation for information and low in autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting reported keeping the highest levels of secrets. Furthermore, our results indicated that paternal autonomy-supportive parenting moderated the relationship between paternal solicitation for information and adolescents’ lying behaviors. Specifically, simple slope analyses showed paternal solicitation for information to be associated with more lies at low levels of autonomy-supportive parenting, and with fewer lies at high levels of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting, β = 0.19, z = 2.48, p = 0.013 and β = −0.25, z = −2.88, p = 0.004, respectively (see Fig. 5). In other words, when adolescents perceived more solicitation for information in an autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting context, they reported lying less to their parents. Conversely, adolescents who perceived their parents as being high in solicitation for information and low in autonomy-supportive parenting reported the highest levels of lies.

Two-way latent interaction effect of perceived paternal solicitation for information and paternal autonomy support on adolescents’ secrecy with fathers. The slope of paternal solicitation was statistically significant at low (−1 SD) levels of autonomy support, β = −0.36, p = 0.002, but not at high (+1 SD) levels of autonomy support, β = −0.06, p = 0.535

Two-way latent interaction effect of perceived paternal solicitation for information and paternal autonomy support on adolescents’ lying to fathers. The slope of paternal solicitation was statistically significant at low (−1 SD) and at high (+1 SD) levels of autonomy support, β = 0.19, p = 0.013 and β = −0.25, p = 0.004, respectively

Discussion

Drawing upon both CPM (Petronio 2002, 2010) and SDT (Deci and Ryan 2000), the general purpose of the present study was to examine the relationships between perceived parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ information management, and to test whether the general parenting context moderated these associations. More specifically, we examined the moderating role of autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting in the relationships between perceived parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ use of disclosure, secrecy, and lies to regulate their privacy.

Results indicated that parental solicitation for information was related to higher levels of disclosure and lower levels of secrecy, though the latter only for fathers. These findings support previous research (e.g., Willoughby and Hamza 2011) which positively linked parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ disclosure, and suggest that one way for parents to promote disclosure is to ask questions directly to their children. Indeed, when adolescents perceive parents’ initiation of conversations as a sign of caring and interest, they seem to be more willing to share information and, by doing so, they seem to try to maintain a close relationship with them. Moreover, in line with previous studies (e.g., Mageau et al. 2017; Wuyts et al. 2018), perceived maternal and paternal autonomy support were positively related to adolescents’ disclosure, and negatively associated with secrecy and lies. In other words, when parents are perceived to provide an autonomy-supportive parenting context, for example by being sensitive for their children’s feelings and by offering choices whenever possible, their adolescents are more likely to disclose information. As Wuyts et al. (2018) suggested, in an autonomy-supportive parenting context, adolescents disclose information because they personally want to (i.e., for volitional reasons), rather than because their parents pressured them to share information (i.e., for controlled reasons).

Importantly, the parenting context in which solicitation for information occurs seems to alter some of the links between parental solicitation and adolescents’ strategies of concealment (i.e., secrecy and lying), confirming SDT’s propositions (Grolnick and Pomerantz 2009; Joussemet et al. 2008). Specifically, when adolescents perceived their fathers as being low in solicitation for information but also low in autonomy-supportive parenting, they reported the highest levels of secrecy. In other words, when adolescents seem to feel like their fathers are not so much interested in their life outside the parental house (as manifested through low scores on perceived solicitation), while at the same time experience their fathers as highly controlling their behaviors, feelings and thoughts (as manifested through low scores on autonomy-supportive parenting), adolescents seem to be more likely to “make no impression”, that is to keep information private from their fathers (Smetana 2011). In line with CPM (Petronio 2002, 2010), it seems that those adolescents would assert their privacy by restricting their fathers’ access to information, which induces a certain distance in the relationship. This result is also consistent with past studies showing that adolescents’ reasons for concealing information is that they perceive their parents as low involved or little concerned by their life (e.g., Bakken and Brown 2010; Tilton-Weaver and Marshall 2008).

Our results further indicate that adolescents whose parents solicit for information in a context that is characterized by relatively low levels of autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting choose an alternative strategy of concealment, that is, lying. This suggests that those adolescents are more likely to make up stories in order to give “a false impression” to their parents (by lying), rather than making “no impression” by keeping secrets (Smetana 2011). Indeed, lying, by definition, implies willingly transmitting incorrect information to their parents in order to deceive them (Marshall et al. 2005; Tilton-Weaver and Marshall 2008). In that respect, Psychological Reactance Theory (PRT; Brehm 1966) may be a useful framework to understand why parents’ solicitation for information occurring in a controlling parenting context may be counterproductive for promoting adolescents’ disclosure. Reactance is defined as a “motivational state that is hypothesized to occur when a freedom is eliminated or threatened with elimination” (Brehm and Brehm 1981, p. 37). In previous research, reactance has been found to be elicited when requests are communicated in a controlling way and induces people to do exactly the opposite of what is expected from them (e.g., Baudat et al. 2017; Van Petegem et al. 2015). In a similar way, when parents’ solicitation for information takes place in a controlling parenting context, adolescents would be more likely to do the opposite of what their parents want them to do, that is, creating false stories through the use of lies.

Finally, our results also indicate that adolescents who reported the lowest levels of lies are those whose parents are perceived as highly autonomy-supportive and soliciting. In other words, such a parenting context seems to be characterized by high levels of openness and communication in the parent–child relationship so that adolescents do not need to engage in lying behaviors towards their parents. As there is some evidence showing that the frequent use of lies has detrimental effects for both adolescents’ adjustment and the relationship with their parents (e.g., Engels et al. 2006; Smetana et al. 2009), the present findings suggest that parents can foster the communication with their children by initiating conversations within an autonomy-supportive (vs. controlling) parenting context.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite these relevant findings, our study has some limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, this study is unable to draw any conclusion about direction of effects. However, past research suggested that parental solicitation for information and adolescents’ information management are reciprocally linked (e.g., Hamza and Willoughby 2011). That is, adolescents are more likely to disclose information when their parents ask questions, but parents are also more inclined to solicit for information when their adolescents communicate information to them. Future longitudinal studies are needed to consider those bidirectional associations. Other methodological limitations concern the design of our study. First, when using self-report questionnaires, participants may provide some inaccurate information due to memory issues, honesty or social desirability. Second, the internal consistency of each scale assessing parental solicitation and information management strategies (disclosure and secrecy) were quite low, which is likely due to the small number of items for each measure. Furthermore, analyses assessing discriminant validity raised concerns regarding overlap between the constructs of paternal solicitation and disclosure to fathers. Future studies would benefit from including multiple informants (e.g., parents, siblings), other scales of disclosure and concealment which have been adapted to the family context (e.g, Finkenauer et al. 2005), and other research methods (e.g., observation of parent–adolescent interaction). Third, our study focused specifically on the moderating role of the general parenting context in which solicitation for information occurs. Future studies could examine specific situational factors that qualify the effectiveness of parents’ solicitation for information, such as parents’ communication style. Indeed, using vignette-based methodologies, a number of recent studies have found that parents’ (autonomy-supportive vs. controlling) style of communicating rules is important for predicting adolescents’ acceptance (vs. defiance) of these rules (Baudat et al. 2017; Van Petegem et al. 2015). In a similar way, we could hypothesize that when parents solicit information using a controlling communication style, their adolescents would more likely to engage in lying behaviors, whereas an autonomy-supportive style most likely would elicit more disclosure. Fourth, in the present study, the questionnaires used in our study assessed solicitation for information and information management about a limited number of topics (i.e., school and unsupervised free time activities). However, drawing upon Social Domain Theory (Nucci 1996; Smetana et al. 2014; Turiel 1983), a growing number of studies demonstrated that, depending upon the social domain, adolescents reason differently about parental legitimacy and, as a consequence, manage information differently (e.g., Smetana and Metzger 2008; Smetana et al. 2006). In addition, even when parents’ solicitation for information is perceived as legitimate, adolescents may have a wide range of reasons for deciding to conceal information, such as avoiding parents’ disapproval or punishments (e.g., Nucci et al. 2014; Smetana et al. 2009). Future research could examine whether associations between parental solicitation for information and information management are different, depending on the content of the topic and on adolescents’ reasons to regulate their parents’ knowledge.

References

Abar, C. C., Clark, G., & Koban, K. (2017). The long-term impact of family routines and parental knowledge on alcohol use and health behaviors: results from a 14 year follow-up. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2495–2504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826017-0752-2.

Afifi, T. D., Caughlin, J., & Afifi, W. A. (2007). The dark side (and light side) of avoidance and secrets. In B. H. Spitzberg & W. R. Cupach (Eds), The dark side of interpersonal communication. 2nd Edn. (pp. 66–91). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bakken, J. P., & Brown, B. B. (2010). Adolescent secretive behavior: African american and hmong adolescents’ strategies and justifications for managing parents’ knowledge about peers. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(2), 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00642.x.

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67(6), 3296–3319. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131780.

Baudat, S., Zimmermann, G., Antonietti, J.-P., & Van Petegem, S. (2017). The role of maternal communication style in adolescents’ motivation to change alcohol use: a vignette-based study. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 24(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1192584.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Brehm, J. W., & Brehm, S. S. (1981). Psychological reactance: a theory of freedom and control. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bureau, J. S., & Mageau, G. A. (2014). Parental autonomy support and honesty: the mediating role of identification with the honesty value and perceived costs and benefits of honesty. Journal of Adolescence, 37(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.12.007.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the social sciences. 3rd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cottrell, L. A., Lilly, C. A., Metzger, A., Cottrell, S. A., Epperly, A. D., Rishel, C., & Stanton, B. F. (2017). Constructing tailored parental monitoring strategy profiles to predict adolescent disclosure and risk involvement. Preventive Medicine Reports, 7, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.06.001.

Criss, M. M., Lee, T. K., Morris, A. S., Cui, L., Bosler, C. D., Shreffler, K. M., & Silk, J. S. (2015). Link between monitoring behavior and adolescent adjustment: an analysis of direct and indirect effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(3), 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9877-0.

Crouter, A. C., Bumpus, M. F., Davis, K. D., & McHale, S. M. (2005). How do parents learn about adolescents' experiences? Implications for parental knowledge and adolescent risky behavior. Child Development, 76(4), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00883.x.

Cumsille, P., Darling, N., & Martínez, M. L. (2010). Shading the truth: the patterning of adolescents’ decisions to avoid issues, disclose, or lie to parents. Journal of Adolescence, 33(2), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.10.008.

Darling, N., Cumsille, P., & Martinez, M. L. (2008). Individual differences in adolescents' beliefs about the legitimacy of parental authority and their own obligation to obey: a longitudinal investigation. Child Development, 79(4), 1103–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01178.x.

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: what, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7.

Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: the self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Finkenauer, C., & van Kooten, D. (2006). Lying behavior, family functioning and adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(6), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9082-1.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using spss. 4th Edn. London, England: Sage.

Finkenauer, C., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Kubacka, K. E. (2008). Relational implications of secrecy and concealment in parent-adolescent relationships. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin & R. C. M. E. Engels (Eds), What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior (pp. 43–64). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Finkenauer, C., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Meeus, W. (2002). Keeping secrets from parents: advantages and disadvantages of secrecy in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014069926507.

Finkenauer, C., Frijns, T. O. M., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Kerkhof, P. (2005). Perceiving concealment in relationships between parents and adolescents: links with parental behavior. Personal Relationships, 12(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2005.00122.x.

Finkenauer, C., Kubacka, K. E., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Kerkhof, P. (2009). Secrecy in close relationships: investigating its intrapersonal and interpersonal effects. In T. D. Afifi & W. A. Afifi (Eds), Uncertainty, information management, and disclosure decisions: theories and applications (pp. 300–319). New York, NY: Routledge.

Foldnes, N., & Hagtvet, K. A. (2014). The choice of product indicators in latent variable interaction models: post hoc analyses. Psychological Methods, 19(3), 444–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035728.

Frijns, T., & Finkenauer, C. (2009). Longitudinal associations between keeping a secret and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408098020.

Frijns, T., Finkenauer, C., Vermulst, A., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2005). Keeping secrets from parents: longitudinal associations of secrecy in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-3212-z.

Frijns, T., Keijsers, L., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2010). What parents don’t know and how it may affect their children: qualifying the disclosure–adjustment link. Journal of Adolescence, 33(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.010.

Garthe, R. C., Sullivan, T. N., & Kliewer, W. (2018). Longitudinal associations between maternal solicitation, perceived maternal acceptance, adolescent self-disclosure, and adolescent externalizing behaviors. Youth & Society, 50(2), 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X16671238.

Goldstein, S. E. (2016). Adolescents’ disclosure and secrecy about peer behavior: links with cyber aggression, relational aggression, and overt aggression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1430–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0340-2.

Graça, J., Calheiros, M. M., & Barata, M. C. (2013). Authority in the classroom: adolescent autonomy, autonomy support, and teachers’ legitimacy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0154-1.

Grolnick, W. S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2009). Issues and challenges in studying parental control: toward a new conceptualization. Child Development Perspectives, 3(3), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00099.x.

Guerrero, L. K., & Afifi, W. A. (1995). What parents don’t know: topic avoidance in parent-child relationships. In T. J. Socha & G. H. Stamp (Eds), Parents, children, and communication: frontiers of theory and research. (pp. 219–246). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hamza, C., & Willoughby, T. (2011). Perceived parental monitoring, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent depressive symptoms: a longitudinal examination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(7), 902–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9604-8.

Hawk, S. T., Hale, W. W., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., & Meeus, W. (2008). Adolescents’ perceptions of privacy invasion in reaction to parental solicitation and control. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 28(4), 583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608317611.

Hawk, S. T., Keijsers, L., Frijns, T., Hale, W. W., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2013). “I still haven't found what i'm looking for”: parental privacy invasion predicts reduced parental knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 49(7), 1286–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029484.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

Hu, L.-t, & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jensen, L. A., Arnett, J. J., Feldman, S. S., & Cauffman, E. (2004). The right to do wrong: lying to parents among adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000013422.48100.5a.

Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Moreno, C., Rivera, F., & García-Moya, I. (2013). The role of the family in promoting responsible substance use in adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9737-y.

Josse, J., & Husson, F. (2012). Handling missing values in exploratory multivariate data analysis methods. Journal de la Société Française de Statistique, 153, 79–99.

Josse, J., & Husson, F. (2016). Missmda: a package for handling missing values in multivariate data analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 70, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v070.i01.

Joussemet, M., Landry, R., & Koestner, R. (2008). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012754.

Kapetanovic, S., Bohlin, M., Skoog, T., & Gerdner, A. (2017). Structural relations between sources of parental knowledge, feelings of being overly controlled and risk behaviors in early adolescence. Journal of Family Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2017.1367713.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S., VanderValk, I., & Meeus, W. (2010). Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 88–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00631.x.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S. J., Frijns, T., Finkenauer, C., & Meeus, W. (2010). Gender differences in keeping secrets from parents in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018115.

Keijsers, L., Frijns, T., Branje, S. J., & Meeus, W. (2009). Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: moderation by parental support. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1314–1327. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016693.

Keijsers, L., & Laird, R. D. (2014). Mother-adolescent monitoring dynamics and the legitimacy of parental authority. Journal of Adolescence, 37(5), 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.04.001.

Keijsers, L., & Poulin, F. (2013). Developmental changes in parent-child communication throughout adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 49(12), 2301–2308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032217.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36(3), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Burk, W. J. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th Edn. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

LaFleur, L. K., Zhao, Y., Zeringue, M. M., & Laird, R. D. (2016). Warmth and legitimacy beliefs contextualize adolescents’ negative reactions to parental monitoring. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.013.

Laird, R. D., Zeringue, M. M., & Lambert, E. S. (2018). Negative reactions to monitoring: do they undermine the ability of monitoring to protect adolescents? Journal of Adolescence, 63, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.007.

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85(4), 1677–1693. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12235.

Larson, R. W., Richards, M. H., Moneta, G., Holmbeck, G., & Duckett, E. (1996). Changes in adolescents' daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 744–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744.

Leys, C., Klein, O., Dominicy, Y., & Ley, C. (2018). Detecting multivariate outliers: use a robust variant of the mahalanobis distance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.09.011.

Leys, C., Ley, C., Klein, O., Bernard, P., & Licata, L. (2013). Detecting outliers: do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(4), 764–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.013.

Little, T. D., Bovaird, J. A., & Widaman, K. F. (2006). On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 13(4), 497–519. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1304_1.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Mageau, G. A., Ranger, F., Joussemet, M., Koestner, R., Moreau, E., & Forest, J. (2015). Validation of the perceived parental autonomy support scale (p-pass). Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 47(3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039325.

Mageau, G. A., Sherman, A., Grusec, J. E., Koestner, R., & Bureau, J. S. (2017). Different ways of knowing a child and their relations to mother‐reported autonomy support. Social Development, 26(3), 630–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12212.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., Wen, Z., Nagengast, B., & Morin, A. J. S. (2013). Moderation. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods (pp. 361–386). Vol. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Marshall, S. K., Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Bosdet, L. (2005). Information management: considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of Adolescence, 28(5), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.008.

Moreau, E., & Mageau, G. A. (2012). The importance of perceived autonomy support for the psychological health and work satisfaction of health professionals: not only supervisors count, colleagues too! Motivation and Emotion, 36(3), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9250-9.

Nucci, L. (1996). Morality and personal freedom. In E. S. Reed, E. Turiel & T. Brown (Eds.), Values and knowledge (pp. 41–60). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Nucci, L., Smetana, J., Araki, N., Nakaue, M., & Comer, J. (2014). Japanese adolescents’ disclosure and information management with parents. Child Development, 85(3), 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12174.

Petronio, S. (1991). Communication boundary management: a theoretical model of managing disclosure of private information between marital couples. Communication Theory, 1(4), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1991.tb00023.x.

Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: dialectics of disclosure. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Petronio, S. (2010). Communication privacy management theory: what do we know about family privacy regulation? Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(3), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00052.x.

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Roth, G., Ron, T., & Benita, M. (2009). Mothers’ parenting practices and adolescents’ learning from their mistakes in class: the mediating role of adolescent's self-disclosure. Learning and Instruction, 19(6), 506–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.10.001.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development: how teens construct their worlds. West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Smetana, J. G. (2018). The development of autonomy during adolescence: a social-cognitive theory view. In B. Soenens, M. Vansteenkiste & S. Van Petegem (Eds), Autonomy in adolescent development: towards conceptual clarity (pp. 53–73). London, England: Psychology Press.

Smetana, J. G., Jambon, M., & Ball, C. (2014). The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. In M. Killen & J. G. Smetana (Eds), Handbook of moral development. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Smetana, J. G., & Metzger, A. (2008). Don’t ask, don’t tell (your mom and dad): disclosure and nondisclosure in adolescent–parent relationships. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin & R. C. Engels (Eds), What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescents’ problem behavior (pp. 65–87). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Smetana, J. G., Metzger, A., Gettman, D. C., & Campione-Barr, N. (2006). Disclosure and secrecy in adolescent–parent relationships. Child Development, 77(1), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x.

Smetana, J. G., Villalobos, M., Tasopoulos-Chan, M., Gettman, D. C., & Campione-Barr, N. (2009). Early and middle adolescents’ disclosure to parents about activities in different domains. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 693–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.010.

Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Vansteenkiste, M., Duriez, B., & Goossens, L. (2008). Clarifying the link between parental psychological control and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Merrill-Palmer Quaterly, 54(4), 411–444. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0005.

Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2010). A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review, 30(1), 74–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.11.001.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Beyers, W., & Ryan, R. M. (2007). Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.633.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Luyckx, K., & Goossens, L. (2006). Parenting and adolescent problem behaviors: an integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Sierens, E. (2009). How are parental psychological control and autonomy-support related? A cluster-analytic approach. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00589.x.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x.

Stattin, H., Kerr, M., & Tilton Weaver, L. C. (2010). Parental monitoring: a critical examination of the research. In V. Guilamo-Ramos, J. Jaccard & P. Dittus (Eds), Parental monitoring of adolescents: current perspectives for researchers and practitioners (pp. 3–38). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Stavrinides, P., Georgiou, S., & Demetriou, A. (2010). Longitudinal associations between adolescent alcohol use and parents’ sources of knowledge. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(Pt 3), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151009x466578.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C. (2014). Adolescents’ information management: comparing ideas about why adolescents disclose to or keep secrets from their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(5), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0008-4.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., Kerr, M., Pakalniskeine, V., Tokic, A., Salihovic, S., & Stattin, H. (2010). Open up or close down: how do parental reactions affect youth information management? Journal of Adolescence, 33(2), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.011.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Marshall, S. K. (2008). Adolescents’ agency in information management. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin & R. C. M. E. Engels (Eds), What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior (pp. 11–41). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., Marshall, S. K., & Darling, N. (2013). What’s in a name? Distinguishing between routine disclosure and self-disclosure. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12090.

Todorov, V., & Filzmoser, P. (2010). Robust statistic for the one-way manova. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 54(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2009.08.015.

Turiel, E. (1983). The development of social knowledge: morality and convention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.

Urry, S. A., Nelson, L. J., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2011). Mother knows best: psychological control, child disclosure, and maternal knowledge in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Studies, 17(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2011.17.2.157.

Van Petegem, S., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Beyers, W. (2015). Rebels with a cause? Adolescent defiance from the perspective of reactance theory and self-determination theory. Child Development, 86(3), 903–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12355.

Van Petegem, S., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Zimmermann, G., Antonietti, J.-P., Baudat, S., & Audenaert, E. (2017). When do adolescents accept or defy to maternal prohibitions? The role of social domain and communication style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 1022–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0562-7.

Van Petegem, S., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Brenning, K., Mabbe, E., & Zimmermann, G. (2017). Does general parenting context modify adolescents’ appraisals and coping with a situation of parental regulation? The case of autonomy-supportive parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(2), 2623–2639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0758-9.

Villalobos Solís, M., Smetana, J. G., & Comer, J. (2015). Associations among solicitation, relationship quality, and adolescents’ disclosure and secrecy with mothers and best friends. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.016.

Willoughby, T., & Hamza, C. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of the bidirectional associations among perceived parenting behaviors, adolescent disclosure and problem behavior across the high school years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9567-9.

Wuyts, D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Van Petegem, S. (2018). The role of observed autonomy support, reciprocity, and need satisfaction in adolescent disclosure about friends. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.03.012.

Youniss, J., & Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the adolescents and their parents who kindly accepted to participate in the study. We are also grateful to the principals and deans of the schools, and the Direction de l’Enseignement Obligatoire (DGEO) of the Canton de Vaud in Switzerland. We thank Nadia Barmaverain for assistance with data collection and input.

Author Contributions

S.B. conceived of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. S.V.P. offered insights into parenting, and helped with the interpretation of the data and the writing of the manuscript. J.P.A. supervised and assisted with the data analyses, and helped with the interpretation of the data and the writing of the manuscript. G.Z. supervised the project and helped with the interpretation of the results, and the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read, edited and approved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in compliance with the Ethics Code of the Swiss Psychological Society (SPS).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article