Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the associations between emotional availability (EA) and mindful parenting (MP), as well as their independent and combined associations with indicators of adolescent well-being. EA is a well-established measure of parent-child relationship quality and conceptualized to be a life-span measure of emotional connection in relationships. Thus far, the EA literature spans pregnancy to middle childhood. The current study extends the concept into the adolescence. MP is a construct shown to be associated with both positive parent-child relationships and adolescent well-being.

Methods

The current study tests the association among EA, MP, and indicators of adolescent well-being in a sample of 30 mother-adolescent dyads (adolescent ages 10-14 years). EA and MP were assessed through observational coding of parent-adolescent interactions.

Results

Results indicated significant associations between EA and MP, and between each construct and adolescent outcomes. The strongest correlations were found between global scores of MP and EA (.53), and between MP subscales and the EA Scales of sensitivity (0.44-0.56) and structuring (0.48-0.59). One EA scale, adult nonhostility, and one MP scale, nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child, were significant predictors of parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems, independently and after accounting for the other (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

These results indicate there are significant relations between EA and MP and both constructs are related to adolescent outcomes, with some specific contributions to indicators of adolescent well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness has become a common approach for understanding interpersonal relationships (Cohen and Semple 2010). Across a broad developmental spectrum, higher levels of mindfulness has been associated with such outcomes as positive affect, less depression and anxiety, and greater relationship satisfaction and less relationships stress (Barnes et al. 2007; Brown and Ryan 2003; Duncan et al. 2009).

Mindful parenting (MP) is a construct for understanding parent-child relationships (Duncan et al. 2009). Mindful parenting (MP) is globally defined as receptive attention to and awareness of present events and experience and being present in the moment for one’s children (Brown et al. 2007). Research has shown that MP is associated with multiple aspects of the quality of parent-adolescent relationships (Coatsworth et al. 2010; Duncan et al. 2009; Lippold et al. 2015). Emotional availability (EA) is a well-established construct of parent-child relationship quality, based in attachment and systems theories, that is significantly associated with various positive developmental outcomes in infancy and early childhood (Biringen et al. 2014). EA already has a wide evidence base related to infancy and childhood; the current study extends this work into adolescence (Biringen et al. 2014). Moreover, although the definitions and descriptions of EA and MP show some overlap, to our knowledge, these constructs have not been investigated together in a single study. As MP continues to grow as a method of enhancing relationships, it is important to investigate a potential association with EA in parent-adolescent dyads. Additionally, examining the association between two constructs may elucidate which components of MP are most related to the qualities of EA, and whether these are uniquely related to adolescent outcomes.

The conceptual model of MP includes five dimensions: listening with full attention, nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child, emotional awareness of self and child, self-regulation in the parenting relationship, and compassion for self and child (Duncan et al. 2009). The first dimension, listening with full attention, includes correctly discerning a child’s behavioral cues, and accurately perceiving the child’s verbal communication. The second dimension, non-judgmental acceptance of self and child, entails a healthy balance between child-oriented, parent-oriented, and relationship-oriented goals, a sense of self-efficacy in parenting, and appreciation for the child’s traits, rather than unrealistic views based solely on parental expectations. The third dimension, emotional awareness of self and child, involves responsiveness to the child’s needs and emotions, rather than dismissal of such emotions, and accuracy in attributions of responsibility. The fourth dimension, self-regulation in the parenting relationship, refers to regulating emotions in the parenting context, and parenting in accordance with values and goals, rather than through over-reactiveness to the moment. Lastly, the fifth dimension, compassion for self and child, entails positive affection in the parent-child relationship, and a more self-forgiving view of parental efforts, rather than negative emotions toward the child and self-blame (Duncan et al. 2009). Mindful parenting has been associated with a greater ability to regulate one’s own emotions and provide consistent parenting (Parent et al. 2016) as well as lower levels of coercive and ineffective discipline, higher levels of warmth and reinforcement, and increased parent-child communication (Lippold et al. 2015).

Emotional availability (EA) is a construct that emphasizes the “emotional” features in parent-child relationships. EA expands upon attachment, accounting for perspectives of the adult as well as of the child in the same observational context. Additionally, EA offers a view of the parent-child dyadic relationship that is more than parental sensitivity. This perspective focuses on positive as well as negative aspects of relationships and has the capacity to be applied to multiple contexts (Biringen et al. 2014). The EA Scales were created to observationally measure EA and are comprised of four scales for adults that include sensitivity, structuring, non-hostility, and non-intrusiveness, as well as two scales for children including responsiveness and involvement (Biringen et al. 2014). Adult sensitivity entails a caregiver’s ability to create a positive and genuine environment, as well as having a clear discernment of and appropriate responsiveness to their child’s emotional expressions. This scale also includes elements of parental acceptance of the child. Adult structuring refers to the amount of guidance, scaffolding, and mentoring a caregiver provides to their child. This component also incorporates appropriate boundary setting and getting successful responses to demands, while facilitating autonomy and internal rules for the child. Adult non-hostility involves lack of hostility in a caregiver’s interactions with their child, including covert and explicit or open forms of hostility. Hostility might include feelings of frustration, anger, or impatience. Adult non-intrusiveness refers to the caregiver’s ability to avoid over-direction, over-stimulation, interference, or over-protection. Child responsiveness encompasses positive affect and emotion regulation as well as emotional responsiveness to the adult. Lastly, child involvement includes the child’s level of simple and elaborative initiative to engage the adult in an interaction, in addition to the balance of autonomy and exploration (Biringen et al. 2014). In addition, the system provides a measure of emotional attachment, specifically “emotionally available”, “complicated”, “detached”, and “problematic” that theoretically maps onto attachment categories (Biringen 2008).

Emotional availability has been found to be associated with multiple positive outcomes throughout infancy, the preschool years, as well as middle childhood. Specifically, higher levels of many of the EA qualities have been found to be related to greater incidence of secure attachment (Biringen et al. 2014). In addition, some studies have used still face interactions to show that poor parent-baby relationship quality, or low levels of EA, is related to disrupted emotion regulation (Kogan and Carter 1996). Results showed lower EA prior to the still face relates to more avoidant and resistant infant behaviors following the still face period, whereas higher EA relates to more responsive and involved infant reengagement behavior, and less resistance and avoidance. These results suggest that parent-child relationship quality may contribute to emotion regulation skills in stages as early as infancy. Furthermore, EA has been linked with language development and prosocial outcomes in early childhood, such as complex peer play, higher pretend play, and less peer exclusion in pre-kindergarten children (Biringen et al. 2014; Howes and Hong 2008). Additionally, aspects of emotional availability (maternal sensitivity, nonhostility, and nonintrusiveness) are associated with adaptive functioning in middle childhood (Easterbrooks et al. 2012). Utilizing the EA Scales into adolescence could be valuable because parent-adolescent relationship quality is an important contributing factor to overall adolescent well-being, despite children becoming more independent (Biringen et al. 2014; Johnson and Galambos 2014).

Adolescence has been identified as a critical developmental stage of interest as children become more independent and develop psychosocial competencies that become a foundation for a successful transition to adulthood and later functioning (Johnson and Galambos 2014). Thus, relationships that are fostered during adolescence impact the way individuals interact and connect with others in adulthood. Specifically, the quality of parent-child relationships has been associated with multiple positive outcomes in adolescence. For example, a high-quality parent-child relationship is a significant protective factor in adolescent development with positive outcomes such as higher young adult intimate relationship quality and fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, including depression and low self-esteem (Johnson and Galambos 2014).

While there is no prior research on emotional availability during adolescence, the related construct of attachment is viewed as an important quality through the adolescence years, and well beyond. In fact, Bowlby (1983) indicated that attachment relationships are actually formed, and even revised during adolescence. Indeed, the many tasks of adolescence, including the task of successful conflict negotiation and its resolution (Collins 1997) are thought to take place against a backdrop of an existing secure attachment relationship. Attachment security is significantly associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence (Allen et al. 2007). Explicitly, secure attachment is linked to success in overall adjustment, including establishing autonomy and agency while maintaining connection with fathers and peers, and insecure attachment is associated with increased patterns of externalizing behavior and depressive symptoms (Allen et al. 2007). Finally, there is evidence that secure parent-child attachment relationships (as well as such romantic relationships) during adolescence are associated with greater life satisfaction during adolescence (Guarnieri et al. 2015). Studies such as these indicate the importance of the parent-child relationship in adolescence as it relates to long-term outcomes. They also support the need for an expanded view of contributing factors to the quality of parent-adolescent relationships.

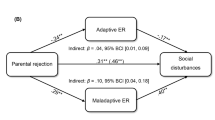

Harnett and Dawe (2012) offer a model for the connection between mindfulness and emotional availability, with a theoretical integrated model of family functioning, proposing that mindfulness contributes to self-regulatory capacities in parents, which allows them to be more emotionally available in interactions with their children. In addition to this overall model, we believe the components of these two constructs may also be related to one another. We use the Mindful Parenting Observational Scales (MPOS; Geier et al. 2012), which will be used to assess MP, evaluates the five components described by Duncan et al. (2009) and the Emotional Availability Scales are used to evaluate EA, which is comprised of 6 dimensions. There may be multiple connections between specific elements of each construct. Components of MP such as listening with full attention, nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child, emotional awareness of self and child, self-regulation, as well as compassion for self and others, all share common themes with the EA dimensions of caregiver sensitivity and non-hostility. For example, the EA dimension of adult sensitivity and the MP component of listening with full attention both involve a caregiver’s capacity to accurately discern their child’s expressions, with one being specific to emotions (Biringen et al. 2014) and the other to behavioral or verbal expressions (Duncan et al. 2009). Similarly, there is overlap between EA components of adult sensitivity and the MP element of non-judgmental acceptance in that both require appreciation for the child’s traits (Biringen et al. 2014; Duncan et al. 2009). Additionally, the EA subscale of adult non-hostility is similar to the MP component of self-regulation, in that both emphasize the regulation of negative affective expressions, such as frustration, anger, or impatience. Additional conceptual overlaps between EA and MP are depicted in Fig. 1.

EA also differs from MP in some respects. For example, EA focuses on nonverbal communication in a parent-child interaction and the discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal channels of communications, whereas this is not a specific focus of MP. In addition, being a relational or dyadic quality, EA explicitly takes into account the child’s perspective and response in even the evaluation of the parental side of the relationship, whereas the child is not specifically assessed or explicitly taken into account in MP. EA also emphasizes attachment-relevant functioning in its components, particularly the child’s side of emotional availability. In contrast, MP may contribute to more secure attachment functioning, but does not directly address attachment.

Because this study is novel in examining the associations between EA and MP, our analyses are generally descriptive. Our hypotheses were based on conceptual rather than empirical grounds. Our first aim was to examine the associations between dimensions of MP and EA. Based on our proposed conceptual overlap between these two constructs (see Fig. 1), we hypothesized that each of the EA dimensions would be weakly to moderately associated with the MP dimensions. The second aim involved examining the association of EA and MP with adolescent outcomes, including behavioral issues (internalizing and externalizing behavior problems) and wellbeing (agency and life satisfaction). We hypothesized that EA and MP would be significantly associated with adolescent behavior problems and wellbeing. Because of the lack of strong theory and any empirical literature, we did not make predictions about which specific EA and MP dimensions would show these associations. The third aim examined the unique and combined associations of EA and MP dimensions with adolescent behavior problems and well-being. Although these two constructs are conceptually similar, we hypothesized that EA and MP would demonstrate unique positive associations with well-being, and unique negative associations with adolescent behavior problems. The suggested correlation between EA and MP and their relations to adolescent outcomes is depicted in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants

The sample for this study was comprised of 30 mother-adolescent dyads that were randomly selected from the original study sample, stratified by intervention condition. The current study sample was evenly split by gender (47% males), with average adolescent age of 12.4 (SD = 0.66). Families had an average income of $63,536 (SD = $45,936), with 50% of mothers having graduated from college. Racial diversity was consistent with the demographics of the region, with 80% of mothers self-reporting as White and 20% as non-White (Black/African American or Hispanic). Two-thirds of the families were from two-parent homes with mothers reporting being married or in a stable, marriage-like relationship. We included only mothers, because there was full data for the 30 mothers but full father data were available for only 60% of the sample.

Procedures

The current study is a secondary analysis of a previously collected data set to study the relation between EA and MP and their potential intercorrelations, as well as their associations with adolescent outcomes. By way of background, please note that the data were collected in the context of a randomized trial of the Mindfulness Enhanced Strengthening Families Program (MSFP 10-14) intervention (Coatsworth et al. 2015), although in this paper we were not interested in examining the intervention effects. Again, by way of background, the original project included families of 5th, 6th, and 7th grade students who were recruited from three rural school districts in central Pennsylvania (Coatsworth et al. 2015). Assessments were completed just before and after the intervention and surveys were mailed at both times to participating families. Following baseline assessments, families were randomly assigned to three conditions including the original SFP 10-14 program, the MSFP 10-14, and a delayed home study intervention control condition. Data for the current study are taken from post-intervention assessments, which we believed would provide greater variability in mindfulness scores and therefore a stronger possibility of observing associations with EA. In addition to this, we conducted very high-quality coding of MPOS as well as the EA Scales, decreasing “noise” in the data, and obtained full coding with no missing values.

Video Interaction Task

As part of the assessment procedures for the original project, mothers and adolescents participated in a video recorded 15-min structured interaction task. For past evaluations of SFP 10-14, the task has been used to generate data as rated by the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales, 5th Edition (IFIRS; Melby et al. 1989). In the interaction task, the mother and adolescent discussed a series of 13 questions about the nature of their relationship. Questions were designed to elicit increasingly strong emotional responses and potential for disagreement. Example questions included “How do I know what’s going on in my child’s life, like in school, friends or other activities”; and “What does mom say when I do something she doesn’t like? Does she always do what she says she will do when this happens?”

For the current study, 30 video recordings of mother-adolescent dyadic interactions from post-intervention observations were selected. All cases with codable videos (N = 275) were stratified by the three intervention conditions and ten from each were randomly selected for this study. Videos were coded using an adapted version of the Mindful Parenting Observational Scales (MPOS; Geier et al. 2012) and the EA Scales coding manual, 4th edition (Biringen 2008).

Coding Procedures for MP

Coding using the adapted version of the MPOS was conducted by one of the developers of the scales who is also a gold standard coder.

Coding Procedures for EA

EA in mother-adolescent relationships was double coded for all 30 videos by the first author and a gold standard coder. For the EA Scales, two researchers who had completed the required training (Biringen 2005) were responsible for the coding. After achieving inter-rater reliability (assessed as intraclass correlations, ICCs) between coders on the first ten cases, the remaining videos were coded in groups of 10 with ICCs calculated to check for drift. Across the 30 cases the ICC for the EA Scales ranged from 0.70 to 0.94, indicating strong inter-rater reliability.

Data Analysis

Our data analysis proceeded in three steps. First, we conducted preliminary analyses to examine the distributions of each study variable and one-way Analysis of Variance tests on all independent and dependent variables to determine if there were differences by intervention condition. When examining these differences, we set a relatively conservative level of p < 0.10. Second, we computed bivariate correlations to examine the associations between EA and MP (aim 1) and the associations between EA dimensions MP dimensions and adolescent outcomes (aim 2). Lacking prior empirical findings, we conducted these analyses in exploratory mode without strong directional hypotheses predicting how specific dimensions of EA and MP would associate with adolescent outcomes. We therefore did not apply a Type I correction (e.g., Bonferroni) to account for number of correlations examined. Third, multiple regression analyses were used to test the hypothesis that emotional availability (EA) and mindful parenting (MP) variables would show significant unique and combined associations with adolescent outcome variables (aim 3). Because of the modest sample size, we sought to limit the number of variables entered into the regression equations. For each regression, we selected the EA and MP variables with the strongest associations with the adolescent outcomes (aim 2) to be used as predictors in these analyses. When more than one EA or MP variables had identical correlations to the outcome variable, both were tested in separate analyses and the strongest of the two is presented.

For each outcome variable, we conducted two regression equations. In these analyses, step 1 included the control variables of sex, age, and maternal education (as proxy for socioeconomic status), step 2 and step 3 alternated entering the selected EA or MP variables with step 3 testing for unique variance accounted for beyond effects of prior predictors.

Measures

Mindful Parenting

Mothers’ mindful parenting was assessed observationally using an adapted version of the mindful parenting observational scales (MPOS; Geier et al. 2012). The original measure consists of 17 behavioral rating scales of parenting behavior that assess various facets of how mindful parenting is hypothesized to manifest interpersonally, and 1 rating of adolescent behavior. On the original scales, ratings on each scale are made on a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (“Low”/“None”) to 5 (“High”). These scales are combined into composite scores reflecting the five dimensions of mindfulness in parenting articulated by Duncan and colleagues (2009): Listening with full attention; emotional awareness of self and child; nonjudgmental acceptance of self and other; self-regulation in parenting relationship; compassion for self and other. For the adapted version of the scales used in this study, a global rating was made for each of the five dimensions and one overall global scale. Each dimensional rating was based on similar concepts as the sub-items of the MPOS, even though ratings were not made on those sub-items. All ratings were made on a 1-5 Likert scale.

Listening with full attention was based on two broad concepts of attentive listening, which means the extent to which a mother reflects a present-centered focus on her child through her listening behavior, and verbal reciprocity, which means the extent to which the mother is an active and willing participant in the interaction and how well she aligns her speech with meaning conveyed by her child (Bryan et al. 2016). Emotional awareness of self and child assessed the frequency of the mother’s use of emotion words to describe global or discrete emotional states (e.g. “I felt sad when you didn’t make the team, too”) that reference the mother or the child (Bryan et al. 2016). Nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child reflected mother’s degree of openness/acceptance, meaning her interest in and openness towards her adolescent’s opinions, attitudes, behavior, attributes, and emotions, with minimal evaluation or judgment, and validation, the mothers’ level of communication of understanding and/or agreement with an adolescent’s statements and emotions a mother employs (Bryan et al. 2016). Self-regulation in the parenting relationship reflected mothers’ defensiveness, meaning her behavior that is characterized by attempts to avoid responsibility, blame, or judgment, wait time, representing an aspect of reactivity referring to the time between when an adolescent stops talking and when the mother begins, negative emotional valence, which assessed the frequency of negative affect in mothers’ responses to the adolescent and, Intensity which refers to the emotional strength, magnitude, and meaning of a mother’s responses (Bryan et al. 2016). Compassion for self and child reflected the extent to which mother expressed contempt, or blatant disrespect or disregard for her child, often in a hurtful, humiliating, or belittling manner, affection, reflecting frequency and strength of clear, intentional displays of caring, concern, comfort, and love. Compassion addressed the level of recognition, empathy, and child-centeredness in the way a mother approaches her adolescent when they display an actual or potential experience of negative emotion (Bryan et al. 2016). Global ratings were made based on the entire interaction. Bryan et al. (2016) discovered that the original MPOS measure can be reliably coded by independent observers and acceptably compares to other established and similarly structured observational measures.

Emotional Availability

Mother-adolescent interactions were coded for Emotional Availability using The Emotional Availability Scales 4th edition for middle childhood/youth (Biringen 2008). The system includes six scales. Adult sensitivity ranges from 1 (“Insensitive”) to 7 (“Highly Sensitive”) and captured appropriateness of a mother’s affect and behavior in the interaction (Biringen 2008). This measure assessed the amount of warmth and enjoyment of the interaction by both the mother and child as evidenced by pleasant facial expressions and tone of voice, and comfortable physical and eye contact. This scale also assessed a mother’s ability to appropriately detect and respond to their child’s signals or cues such as in a situation of distress. Other components include mothers’ awareness of timing, acceptance of the child, and amount of age appropriate interaction with appropriate flexibility for play themes, and ability to skillfully resolve conflicts (Biringen 2008). Adult structuring ranges from 1 (“Non-optimal”) to 7 (“Optimal”) and captured the amount of guidance and support that a mother provided for the child while allowing for an appropriate amount of autonomy (Biringen 2008). Also captured were how successful bids for structuring were and how well the mother provides a firm but not harsh level of discipline, while remaining firm under pressure from the child. Additional components include adult utilization of nonverbal and verbal forms of structuring and ability to maintain a parental role as opposed to a peer-like role as evidenced by posture, tone of voice, or facial expressions (Biringen 2008). Adult nonintrusiveness ranges from 1 (“Intrusive”) to 7 (“Nonintrusive) and captured how well a mother allowed their adolescent to lead interactions and to explore autonomy without overpowering the interaction (Biringen 2008). Also assessed were the mother’s ability to find non-interruptive points of entry to the interaction without causing a feeling of intrusiveness to the adolescent, as evidenced by adolescent’s reactions and behaviors; the use of few commands; and talking as an interactional communication tool, allowing space for the adolescent to contribute and respond. This scale also incorporated how well the mother taught with the purpose of relating, facilitated participation while actively listening, and limited physical or verbal interferences to a minimum. (Biringen 2008). Adult nonhostility ranges from 1 (“Hostile”) to 7 (“Nonhostile) and encompassed lack of overt and covert forms of hostility which are evidenced by negativity in face or voice, and in words or deeds (Biringen 2008). Additional components include a lack of the following: demeanor or statements that are mocking or disrespectful of the adolescent, threats of separation, frightening statements, inappropriate silence, and unresolved negative play themes. Also incorporated was the mother’s ability to maintain composure during stressful circumstances and not become stressed or dysregulated (Biringen 2008). Youth responsiveness ranges from 1 (“Non-optimal in Responsiveness”) to 7 (“Optimal in Responsiveness”) and assessed for an affectively positive stance evidenced by pleasure in the interaction and an appearance of genuine contentment (Biringen 2008). Other measures include amount of well-balanced emotion regulation that is age appropriate and showing predictability and organization of affect, frequency of responsiveness to bids from the mother while balancing appropriate level of autonomy, physical positioning that welcomes interaction, lack of role reversal or avoidance of the mother, and being appropriately task-oriented or focused on an activity (Biringen 2008). Youth involvement ranges from 1 (“Non-optimal Involvement) to 7 (“Optimal Involvement”) and assessed for adolescent’s attempts to eagerly engage the mother without anxiety or negativity and without compromising autonomy (Biringen 2008). This scale also assessed for use of visual, physical, and verbal connection with the mother as well as lack of negatively involving behaviors such as irritation or anger. Other components include use of simple initiatives, such as looking or talking, and elaborate initiatives, such as creating an elaborated exchange with the mother (Biringen 2008). In addition to the six scales above, the system also yields a measure of emotional attachment, called EA Clinical Screener (CS) (or overall EA Zones), on a scale from 1 to 100, which is then partitioned into four zones that theoretically map onto attachment categories. Relationships are thus categorized into the emotionally available zone (81-100), complicated emotional availability zone (61-70), emotionally unavailable/ detached zone (41-60), and problematic/disturbed zone (1-40) (Biringen 2008). Mother and child are given separate overall scores for this. Thus, we use the EA Mother CS for the mother and EA Adolescent CS for the adolescent.

The EA Scales have been found to have inter-rater reliability in numerous studies (Biringen et al. 2014). Cross-contextual reliability has also been established with significant correlations between EA scores collected in the laboratory and home contexts (Bornstein et al. 2006). The EA Scales have also been found to have construct validity and cross-cultural applicability (Biringen et al. 2014) and links with attachment (Altenhofen et al. 2010; Biringen et al. 2014).

Adolescent Behavior Problems

Mothers reported on their adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). This is a frequently used measure with well-established reliability and validity (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). In this study, the two broad-band measures of internalizing, indicating behaviors reflecting anxiety, depression and somatization, and externalizing, indicating behaviors of aggression, attention problems and minor delinquency, were used. Internal consistency reliability for internalizing (α = 0.91) and externalizing (α = 0.94) in the original study was excellent.

Adolescent Well-Being

Adolescent well-being was assessed using the Student Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner 1991), and Youth Agency Scale (Bradley 2013). The life satisfaction scale is the most commonly used measure of child and adolescent satisfaction with life. It contains seven broad items reflecting adolescent report of how satisfied they are with their life (e.g. “My life is just right”) all reported on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). This measure has been shown to have good construct validity through appropriate associations with other life satisfaction measures and concurrent validity through associations with related outcomes such as depression, anxiety, social stress, loneliness, and aggressive behaviors (Huebner et al. 2003). This measure has also shown appropriate discriminant validity wherein life satisfaction measures are not correlated with IQ scores or grades, as well as predictive validity which indicates life satisfaction as a protective factor against adverse life events in adolescence (Huebner et al. 2003). The Life Satisfaction Scale also shows significant test-retest reliability across several time points (Huebner et al. 2003). In the original study, this measure showed good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.86) (Coatsworth et al. 2015). The Youth Agency Scale is a brief, 9 item measure developed for the original study (Bradley 2013) designed to measure adolescent intrinsic motivation (e.g., “I feel inspired to do things that interest”), behavioral agency (e.g., “I take action to do the things I want to do”), and cognitive agency/goal direction (“I think of different ways to reach my goals”). This measure has shown good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.81). The measure also showed good concurrent validity with other indicators of adolescent functioning (Bradley 2013).

Demographic Variables

Demographic information was collected to describe the sample and to use as covariates when necessary. Youth and mothers reported on age (date of birth), and sex. Mothers reported on household income and level of education completed. We used youth report of sex (Male = 1, Female = 0). We computed age at time of assessment using youth birthdate. Similar to prior studies (Coatsworth et al. 2015), we used mothers’ education level as an indicator of SES. Mothers education was reported on a scale ranging from 1 = less than 7th grade to 7 = graduate degree (MS, JD, PhD., M.D., etc).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

All study variables showed relatively normal distributions with skew/Standard Error of skew less than 1.96. Only adolescent reports of internalizing showed differences between intervention conditions that approached statistical significance; F (2,27) = 2.52, p = 0.09. Condition was therefore included as a control variable in analyses involving adolescent report of internalizing symptoms.

Associations Between EA and MP Dimensions

With only a few exceptions, adult EA variables were significantly correlated with MP variables (see Table 1). Correlations between EA and MP dimensions ranged between 0.08 and 0.59 (bottom left bolded portion of Table 1). Correlations were particularly strong between MP subscales and the EA scales of sensitivity (0.44-0.56) and structuring (0.48-0.59). Weaker and non-statistically significant correlations were found between the EA variable of nonintrusiveness and MP dimensions.

Associations Between EA Dimensions, MP Dimensions and Adolescent Outcomes

As presented in Table 2, the adolescent outcome of life satisfaction was most consistently and strongly associated with EA dimensions, especially with adult sensitivity, adult structuring, adolescent responsiveness, and adolescent involvement (r = 0.40-0.52). Adult nonhostility and adolescent responsiveness were significantly negatively associated with parent reported adolescent externalizing problems. Adolescent responsiveness was significantly negatively correlated with parent reported adolescent internalizing problems. Correlations between EA dimensions and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems were weak to moderate in size and not statistically significant.

Overall, weak to moderate correlations between MP variables and adolescent outcomes were found. Only two associations reached statistical significance: nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child had a significant positive correlation with life satisfaction (r = 0.37) and self-regulation had a significant negative correlation with youth-reported externalizing problems (r = −0.44).

Combined and Unique Associations of EA and MP With Adolescent Outcomes

Adolescent- and Parent-Reported Adolescent Internalizing Problems

As presented in Table 3, EA adolescent responsiveness was a significant independent predictor of parent reported adolescent internalizing problems after controlling for the demographic variables (R2 = 0.19) and was also a unique predictor accounting for an additional 11% of the variance after the MP variable of emotional awareness was entered in the equation. In contrast, emotional awareness was a significant predictor independently, but did not account for additional variable after adolescent responsiveness was entered. Neither emotional awareness of self and child nor adolescent responsiveness are significant predictors of adolescent-reported internalizing problems. In this analysis, the intervention condition was the only significant predictor.

Adolescent- and Parent-reported Adolescent Externalizing Problems

Table 4 presents results from regression analyses, predicting externalizing problems. EA nonhostility has an identical correlation as EA adolescent responsiveness with parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems, and both relate similarly to the outcome variable in a regression analysis as they are each a significant predictor together but nonsignificant independently. Nonhostility has a slightly stronger relationship to parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems and was used in the analysis including the MP and outcome variables. Additionally, MP nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child has an identical correlation as MP compassion for self and child with parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems and were both included separate regression analyses. However, nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child is a statistically significant predictor of the outcome variable and is thus presented in Table 4 as opposed to the nonsignificant predictor, compassion for self and child.

After controlling for variables entered in step 1, both EA adult nonhostility and MP nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child were statistically significant predictors of parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems, independently and also after accounting for the other. Analyses indicated that MP parental self-regulation and EA adolescent responsiveness were both significant independent predictors (EA adolescent responsiveness showed a weaker non-statistically significant trend) but were not significant after accounting for the other. These results suggest that the two variables may be associated with this outcome variable in similar ways.

Adolescent Life Satisfaction and Agency

EA mother CS and MP nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child were selected for regression analyses with adolescent-reported life satisfaction. EA adult structuring and MP emotional awareness of self and child were selected for regression analyses with adolescent-reported agency. Results, presented in Table 5, indicate that EA or MP variables were not statistically significant predictors of adolescent life satisfaction or adolescent agency. However, weaker statistical trends at the .10 level were found between life satisfaction and the predictors of EA mother CS and MP nonjudgmental acceptance. See Table 5.

Discussion

We examined the association between emotional availability (EA) and mindful parenting (MP), and their similar and unique links with adolescent well-being (life satisfaction, agency), and behavior problems (internalizing and externalizing). The first aim was to understand if EA would be correlated with MP in meaningful ways, with our findings supporting this hypothesis but also indicating that the constructs are not identical. The strong correlation between the global scores of the maternal EA and MP constructs indicates that high quality mother-adolescent relationships also tend to have higher levels of mindful parenting. This finding is interesting because it provides insight into how specific parenting behaviors (captured in the MP construct) are related to mother-child relationship quality, captured in the EA construct. The strongest associations emerged between EA and the MP scale of parental self-regulation, suggesting mothers who are better able to regulate their own emotions (as evidenced by low levels of defensiveness, infrequent negative affect, and appropriate responses) (Duncan et al. 2009), are more likely to exhibit higher EA. For example, a mother who can regulate emotions such as impatience, frustration, or boredom, is also more available to show sensitivity to her adolescent and less likely to show hostility (Biringen 2008). The findings also suggest that adolescents show higher EA (e.g., being more eager to engage with their mother in a positive, enthusiastic, and appropriate manner, and initiate elaborated engagement with their mother) when the mother is well-regulated.

Additional features of EA that are correlated with self-regulation include adult structuring (providing appropriate guidance and support for the interaction), and adolescent involvement (appropriately engaging and elaborating interactions) (Biringen 2008). These findings are consistent with Harnett and Dawe’s (2012) integrated model of family functioning, which suggests mindful parenting is a means for enabling parents to be emotionally available in their relationships with their children, as it enhances their self-regulatory capacities and allows for consistent parenting. Because the largest number of correlations are seen between EA Scales and MP self-regulation, results from this study would be consistent with the integrated model theory. Further, numerous EA Scales (sensitivity, structuring, nonhostility) as well as the overall EA CS (now referred to as EA emotional attachment zones), are related to all MP dimensions. These associations suggest that mothers who exhibit high emotional availability (by being sensitive, providing appropriate structuring, and exhibiting low hostility) are more likely to exhibit mindful parenting behaviors (Biringen 2008).

Interestingly, all EA Scales except adult nonintrusiveness are related to at least one dimension of MP. This finding could indicate that nonintrusiveness is a unique component of EA and captures some aspect of the mother-adolescent relationship that MP dimensions do not. This is somewhat unexpected because the concept of nonintrusiveness (being available to the adolescent in the relationship without over-mentoring, over structuring, or providing too much guidance) is integrated within some MP dimensions. For example, when coding for listening with full attention, attentive listening requires a mother’s focus on the adolescent and alignment of speech to match the adolescent’s meaning (Duncan et al. 2009), which seems to capture elements of nonintrusiveness. Nonjudgmental acceptance also requires the ability to accept and validate adolescent’s expressions (Duncan et al. 2009), which is consistent with nonintrusive properties of following the adolescent’s lead in an interaction. Nonintrusiveness might be observed in an interaction with a mother allowing the adolescent to read their own conversation question card and respond without interruption (verbal or nonverbal—such as cutting the adolescent off, arguing, or physically taking the card away), and will not use conversation as an opportunity to lecture or over-teach the adolescent. It is quite possible that MP scales incorporate elements of nonintrusiveness, while not explicitly assessing for intrusive behaviors (physical intrusions, verbal interruptions, preventing opportunities for the adolescent to exhibit autonomy), as the EA Scales do.

One important factor to consider in the interpretation of these findings is that the EA measures include adult and adolescent behaviors, whereas MP incorporates only maternal behaviors. Although both constructs take the dyadic interaction with an adolescent into account, it would be expected that elements of adolescent specific measures would be unique to EA. However, there are no MP dimensions that are completely unrelated to an aspect of EA, suggesting there are many overlaps between these constructs.

Our second aim was to understand if EA and MP scales would show significant combined and unique associations with adolescent outcomes. Findings indicate that although there are many similarities between the constructs of EA and MP, there is reason to believe each construct provides unique contributions to understanding mother-adolescent relationships, which is supported further through relationships with adolescent outcomes. The strong associations between EA Scales and life satisfaction suggest that adolescents with more emotionally available mother-adolescent relationships are more likely to report high life satisfaction. This finding is consistent with existing literature that indicates high-quality parent-adolescent relationships relate to fewer internalizing and externalizing problems as well as intimate relationship quality in young adulthood (Johnson and Galambos 2014). Additionally, mothers are more likely to report adolescent externalizing problems when mothers exhibit higher levels of hostility and when adolescents are less responsive. Parents are also more likely to report adolescent internalizing problems when adolescents are less responsive. This finding is consistent with previous studies indicating high-quality mother-adolescent relationships serves as a protective factor for adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems (McWey et al. 2015). Additionally, these findings support that patterns found in middle childhood, such as effective discipline predicting improvements in internalizing and externalizing problems, continue into adolescence (McClain et al. 2010).

MP dimensions are also significantly correlated to adolescent outcomes including life satisfaction and adolescent-reported externalizing problems. Adolescents are more likely to report high life satisfaction when mothers exhibit a nonjudgmental acceptance of themselves and their child. Thus, adolescents are more likely to report life satisfaction with mothers who exhibit interest toward their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors without judgement, and who validate such features of the adolescent. This is interesting considering nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child is also correlated with mother-adolescent relationship quality (as measured by EA Scales), which is strongly related to life satisfaction as well. In addition, adolescents are more likely to report externalizing problems when their mothers have lower levels of self-regulation. Mothers with poor self-regulation may exhibit defensiveness, negative affect, and strong negatively reactive responses to the adolescent. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider how adolescent children of such mothers would manage negative emotions poorly in the form of externalizing behaviors (aggression, delinquency, etc.). This finding provides support of previous research indicating a connection between parenting behaviors and adolescent externalizing problems (Forehand et al. 2013).

The third aim was to understand if EA and MP would show combined and unique prediction of adolescent outcomes. Although there were many statistically significant associations between EA and MP constructs, and both showed significant associations with adolescent outcomes, the correlations were generally moderate in magnitude, suggesting these constructs are also independent in some respects. We tested this idea further in regression analyses in which unique relationships were determined between components from each construct and specific outcomes. This last hypothesis was partially supported with low adolescent responsiveness as a predictor of parents’ reporting internalizing problems (such as anxiety, depression) for their adolescent, after accounting for influences of mothers’ low emotional awareness of themselves and their child. Thus, (low) adolescent responsiveness is a unique EA contributor to indications of adolescent internalizing problems, distinct from MP. Adolescent responsiveness is unique to EA because of the different focus on the adolescent’s behaviors as opposed to the mother’s behaviors. However, its effect on parent reports of adolescent internalizing problems may indicate the effect of adolescent behavior on the mother-child relationship through specific interactions. For example, responsive adolescent behaviors may be one way in which mothers and their children have bidirectional influences on one another, which impacts the overall quality of the relationship and in turn, adolescent outcomes.

Further support for this hypothesis is seen in parents reporting more adolescent externalizing problems (aggression, delinquency) when parents exhibit higher levels of hostility (low nonhostility), after accounting for effects from parents having low nonjudgmental acceptance of themselves and their child. Thus, (low) nonhostility is a unique EA contributor to indicators of adolescent externalizing problems, distinct from MP. There may be behaviors of explicit hostility (captured in nonhostility) that may not be encompassed in MP dimensions, and such behaviors predict adolescent outcomes. Additionally, parents report more adolescent externalizing problems when mothers exhibit less nonjudgmental acceptance for themselves and their child, after accounting for higher levels of parental hostility (low nonhostility). Thus, (low) nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child is an MP dimension independently linked with indicators of adolescent externalizing problems, distinct from EA. This dimension may capture beneficial elements of positive mother-child relationships that is not captured in EA Scales, and these elements predict adolescent outcomes. Moreover, EA Scales uniquely contribute to parent-reported adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems, and MP uniquely contributes to parent-reported adolescent externalizing problems.

Interestingly, despite numerous correlations with EA Scales and an MP dimension, results did not determine unique predictive relationships with life satisfaction. Mothers’ overall emotional availability and nonjudgmental acceptance are not unique predictors of adolescent life satisfaction, after accounting for the other. This may be due to these components being strongly correlated and overlapping in their contributions to adolescent life satisfaction. Because there are so many correlations between dimensions of EA and MP, it may be important to consider how this could have impacted the unique predictive abilities of each component for adolescent outcomes. It is possible that the dimensions included in analyses were correlated in ways that similarly contribute to the adolescent outcome variables, thus confounding each other. Perhaps if alternative correlated scales and dimensions were paired in analyses, there would be more to learn about how each construct relates to adolescent outcomes.

Limitations

Although a small sample size is a limitation, this study is novel in empirically examining the relation between these two important constructs. Harnett and Dawe (2012) suggested a theoretical model of integration that is supported with the empirical findings in this report. Future studies will need to examine this association further to determine which components of EA and MP are similar or unique in contributing to mother-adolescent relationship quality and adolescent well-being. Incorporating these measures into an intervention to enhance MP or EA, could help to illustrate the correlations between these constructs more definitively.

There is also sparse empirical work exploring EA in adolescence, despite a vast amount of literature emphasizing the importance of mother-adolescent relationships and developmental outcomes. Additional exploration of EA within this developmental period is important to consider how the quality of mother-adolescent relationships contributes to adolescent well-being. It will also be important to expand the demographic to include fathers and variations in two-parent homes when examining these relationships. Interventions to increase EA as well as MP in mother-adolescent relationships may be useful in furthering understanding of these relationship qualities to adolescent well-being.

The research reported in this article was supported in part by Grant R01DA026217 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and through grants from the Pennsylvania State University Children Youth and Families Consortium. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Adolescent, & Families.

Allen, J. P., Porter, M., McFarland, C., McElhaney, K. B., & Marsh, P. (2007). The relation of attachment security to adolescents' paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Development, 78, 1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x.

Altenhofen, S., Sutherland, K., & Biringen, Z. (2010). Families experiencing divorce: age at onset of overnight stays, conflict, and emotional availability as predictors of child attachment. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 51(3), 141–156.

Barnes, S., Brown, K. W., Krusemark, E., Campbell, W. K., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33, 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752–0606.2007.00033.x.

Biringen, Z. (2005). Training and reliability issues with the Emotional Availability Scales. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 404–405.

Biringen, Z. (2008). The Emotional Availability (EA) Scales Manual. 4th edition, MiddleChildhood/Adolescent Version. Boulder, CO: emotionalavailability.com.

Biringen, Z., Derscheid, D., Vliegen, N., Closson, L., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (2014). Emotional availability (EA): theoretical background, empirical research using the EA Scales, and clinical applications. Developmental Review, 34, 114–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.01.002.

Bornstein, M. H., Gini, M., Putnick, D. L., Haynes, O. M., Painter, K. M., & Suwalsky, J. D. (2006). Short-term reliability and continuity of emotional availability in mother-child dyads across contexts of observation. Infancy, 10(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327078IN1001_1.

Bowlby, J. (1983). Attachment and Loss: Attachment 1, New York: Basic Books.

Bradley, S. (2013). Adolescent agency: a conceptual model, measurement, and construct validity. State College, PA: The Pennsylvania State University (unpublished doctoral dissertation).

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298.

Bryan, M. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2016). The mindful parenting observational scales (MPOS): Theoretical background and preliminary evidence for inter-rater reliability and incremental validity. Fort Collins, CO: The Colorado State University.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2010). Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their adolescent: Results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Nix, R. L., Greenberg, M. T., Gayles, J. G., Bamberger, K. T., & Demi, M. A. (2015). Integrating mindfulness with parent training: Effects of the mindfulness-enhanced strengthening families program. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038212.

Cohen, J. S., & Semple, R. J. (2010). Mindful parenting: a call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9285-7.

Collins, A. W., Laursen, B., Mortensen, N., Luebker, C., & Ferreira, M. (1997). Conflict processes and transitions in parent and peer relationships: Implications for autonomy and regulation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12, 178–198.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3.

Easterbrooks, M. A., Bureau, J., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2012). Developmental correlates and predictors of emotional availability in mother–child interaction: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 24(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579411000666.

Forehand, R., Jones, D. J., & Parent, J. (2013). Behavioral parenting interventions for child disruptive behaviors and anxiety: what's different and what's the same. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.010.

Geier, M. H., Coatsworth, J. D., Turksma, C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2012). The Mindful Parenting Rating Scales Coding Manual. State College, PA: The Strengthening Families in Pennsylvania Project, Department of Health and Human Development, The Pennsylvania State University.

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., & Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 121, 833–847.

Harnett, P. H., & Dawe, S. (2012). The contribution of mindfulness-based therapies for children and families and proposed conceptual integration. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00643.x.

Howes, C., & Hong, S. S. (2008). Early emotional availability: predictive of pre-kindergarten relationships among Mexican-heritage children? Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 4, 44–25.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the students' life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240.

Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Psychometric properties of two brief measures of Children’s Life Satisfaction: The Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) and the brief multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Paper presented at the Indicators of Positive Development Conference, University of South Carolina.

Johnson, M. D., & Galambos, N. L. (2014). Paths to intimate relationship quality from parent–adolescent relations and mental health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 145–160.

Kogan, N., & Carter, A. S. (1996). Mother–infant reengagement following the still-face: The role of maternal emotional availability in infant affect regulation. Infant Behavior and Development, 19, 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(96)90034-X10.1111/jomf.12074.

Lippold, M. A., Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., Nix, R. L., & Greenberg, M. T. (2015). Understanding how mindful parenting may be linked to mother–adolescent communication. Journal of Adolescent and Adolescence, 44, 1663–1673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0325-x.

McClain, D. B., Wolchik, S. A., Winslow, E., Tein, J.-Y., Sandler, I. N., & Millsap, R. E. (2010). Developmental cascade effects of the New Beginnings Program on adolescent adaptation outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000453.

McWey, L. M., Claridge, A. M., Wojciak, A. S., & Lettenberger‐Klein, C. G. (2015). Parent–adolescent relationship quality as an intervening variable on adolescent outcomes among families at risk: dyadic analyses. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 64, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12111.

Melby, J. N., Conger, R. D., Book, R. A., Rueter, M., Lucy, L., Repinski, D., Ahrens, K., Black, D., Brown, D., Huck, S., Mutchler, L., Rogers, S., Ross, J., & Stavros, T. (1989). The Iowa Family Interaction Coding Manual. Ames, IA: Iowa Adolescent and Families Project, Department of Sociology, Iowa State University.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Rough, J., & Forehand, R. (2016). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x.

Authors’ contributions

J.B. designed and executed the study, E.A. coding, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. J.D.C. collaborated with the design, M.P. coding, data analysis, and writing of the study. Z.B. collaborated with the design, E.A. coding training, and writing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J.B. and D.J.C. declare that they have no conflict of interest. Z.B. has disclosed a potential financial conflict of interest because she developed the emotional availability (EA) system used in this paper and potentially stands to gain from favorable findings. Because of this potential, she voluntarily distances herself from evaluation and reporting activities (e.g. primary data handling, analysis, and sole control over reporting results) and has a conflict of interest management plan supervised by Colorado State University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benton, J., Coatsworth, D. & Biringen, Z. Examining the Association Between Emotional Availability and Mindful Parenting. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1650–1663 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01384-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01384-x