Abstract

Objectives

Examined the influences of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on young children’s social competence, and the potential mediating role of maternal parenting self-efficacy between them in Chinese urban families.

Methods

A two-wave longitudinal study was conducted. A total of 317 young children’s mothers participated in Wave 1, 179 of the 317 participants participated in Wave 2 six months later. Mothers completed scales of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy, and children’s social competence in Wave 1 and reported their children’s social competence again six months later.

Results

Structural equation modeling with a bootstrap resample of 1000 indicated: (a) the cross-sectional study showed that maternal strategies efficacy (ab = .06, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [.02, .10], p = .006) and child outcome efficacy (ab = .14, 95% CI = [.01, .08], p = .002) partially mediated the effect of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and children’s social competence. (b) the six-month follow-up study showed that child outcomes efficacy totally mediated the relationship between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and children’s social competence (ab = .07, 95% CI = [.03, .12], p = .003).

Conclusions

These findings highlight the contribution of the harmonious parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and maternal parenting self-efficacy to young children’s socialization and are discussed in light of family systems theory and the ecological model of coparenting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Given the fast pace of modern life and fierce competition in mainland China, young children’s parents are under pressure from both work and life and have limited time and energy to take care of their children. Meanwhile, the retired grandparents have a lot of time and voluntarily help to look after the young grandkids. This gives rise to the mode of parent-grandparent coparenting (Goh and Kuczynski 2010; Goh 2006). According to a survey on 20,083 seniors conducted by China Research Center on Aging (2012), 71.95% of urban elderly females participated in raising grandchildren. Parent-grandparent coparenting has been a common phenomenon in China that will not disappear in short term (Settles et al. 2009), especially in dual-earner urban families.

Parent-grandparent coparenting derives from mother and father coparenting. It is a conceptual term that refers to the ways that parent and grandparent relate to each other in the role of parenting. Different from grandparent involvement or the degree to which grandparents are involved in childrearing, parent-grandparent coparenting means parents and grandparents functioning as partners in their childrearing roles (Jia and Schoppe-Sullivan 2011; McHale et al. 2002). Coparenting occurs when at least two individuals have overlapping or shared responsibilities for rearing particular children, and consists of actions and feelings that may promote or undermine the partner’s effectiveness as a coparent (Feinberg 2003; Van Egeren and Hawkins 2004).

Parent-grandparent coparenting mode exists both in Chinese and western societies (Settles et al. 2009; Teun et al. 2015). Researchers focus on how such coparenting would influence children’s socialization. Some studies on low-income families or families of children with special needs found that greater mother-grandmother coparenting relationship quality was a protective factor for young children’s social adjustment (Baker et al. 2010; Barnett et al. 2010). Other researchers proposed that for high-risk families (such as families with low socioeconomic status and families having children with special needs), parent-grandparent coparenting could provide a better family environment for young children, give them a stronger sense of security and belonging, promote their interpersonal interactions and social adaption; for normal or low-risk families, however, parent-grandparent coparenting was slightly redundant compared to the role of parents and hence would have little influence on young children’s social adjustment (Lavers and Sonuga-Burke 1997). Guo (2014) also found that young children raised by parents and grandparents together were no different from other children in social competence. Pittman and Boswell (2007) revealed that no relation was found between mother-reported mother-grandparent coparenting and social adaption of children aged 2 to 4 years even in low-income families. Still other researchers reported that grandparenting had negative influences on young children’s social competence. For example, Fergusson et al. (2008) used information collected from 8752 British families in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, found that grandparenting was associated with peer difficulties of four-year-olds. Some Chinese researchers even proposed that parent-grandparent coparenting had a negative influence on young children’s social competence (Liu and Zhao 2013). As can be seen, there is no consensus on the influence of parent-grandparent coparenting on young children’s social competence.

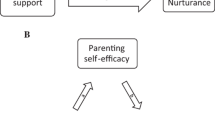

Researchers also probed into the possible process of how parent-grandparent coparenting influenced young children’s social adaption, and found that coparenting could affect children’s social adaption by influencing other factors in the family. This view was formed on the basis of the family systems theory. Family systems theory described how the executive subsystem, comprised of parents and grandparents in their role as co-managers of family members’ behaviors and relationships, regulates family interactions and outcomes (Minuchin 1988). In the whole family, the involvement of other adult nurturers like fathers, grandparents, relatives in extended families and non-family members extends the mother-child relationship to tripartite relationship. Good relationships between nurturers keep the family system balanced, thus benefiting the children (Minuchin 1988). Since then, researchers have made significant progress identifying the aspects of relationships between nurturers most salient for parenting and child adjustment. On the basis of family systems theory, Feinberg (2003) further developed an ecological model of coparenting described the relationship between coparenting and children’s social adaption, and proposed that the coparenting relationship was more closely linked to parenting and child adjustment than any other aspects of family relationship. In this model, coparenting relationship had a direct influence on parents’ way of child rearing and through it, had an indirect influence on children’s adjustment. Therefore, the influence of parent-grandparent coparenting on young children’s social adjustment spanned the whole family systems, in which variables interacted with and depended on each other. In particular, variables most relevant to young children’s social adjustment are maternal parenting concepts and behaviors.

Maternal parenting self-efficacy, as a variable that reflects a mother’s judgment about the extent to which she is able to perform competently and effectively as a mother (Coleman and Karraker 2000), includes how confident she is in using some strategies with her child (i.e., maternal strategies efficacy), and teaching her child an age-appropriate task (i.e., child outcomes efficacy) (Suzuki et al. 2009). Maternal parenting self-efficacy is influenced by the extent and quality of involvement of other family members in child rearing (Giallo et al. 2013), and is a key factor influencing young children’s social adaption (Bloomfield and Kendall 2012; Junttila et al. 2007). This indicates that parent-grandparent coparenting relationship may influence children’s social competence through its effects on maternal parenting self-efficacy. In fact, the above view has been supported to some degree by some studies. Majdandžić et al. (2012) concluded that coparenting could have effects on young children’s emotional adjustment through influencing mothers’ emotional adjustment and parenting behaviors, and proposed a model of relationship among coparenting, maternal adjustment and child adjustment accordingly. This model can be seen as the embodiment of Feinberg’s ecological model in the field of emotional adjustment research. The empirical study of Barnett et al. (2012) found that mother-grandmother coparenting influenced young children’s social development by way of mothers’ negative parenting. Nagase (2015) also revealed that supportive couple relationship affected children’s social competence through parenting self-efficacy. Nonetheless, there are few studies that examined the relationships of parent-grandparent coparenting, maternal parenting self-efficacy and young children’s social competence. In addition, parenting self-efficacy varies in different aspects of parenting (Bandura 1989; Holloway et al. 2016). Coleman and Karraker (2010) found that child outcomes efficacy was more closely related to children’s development compared with maternal strategies efficacy, which indicate that they may play different roles as separate mediators. Junttila et al (2007) also suggested that it would be revealing to study what aspect of maternal parenting self-efficacy is the one that is particularly important to children’s social competence.

Overall, previous studies of the relation between parent-grandparent coparenting and young children’s social competence have laid a foundation for this study, but Chinese and western studies vary greatly due to different cultures. In western countries, children coparented by parents and grandparents are mostly from special families, such as families in which parents are divorced, or one or two parents are unable or unwilling to raise their children because of mental illness, imprisonment, drug abuse, child abuse, etc. In China, however, parent-grandparent coparenting is very common in intact families. In addition, conclusions are inconsistent or even conflicting in some cases as to whether parent-grandparent coparenting has positive or negative influences on young children’s social competence, and the internal process of how parent-grandparent coparenting influences young children’s social adaption is not clear. So it is very important to examine the short-term and long-term predictive effects of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on young children’s social competence, and probe into the mediating role of maternal parenting self-efficacy between them.

On the basis of the family systems theory and the ecological model of coparenting, a follow-up study was conducted to examine the short-term and long-term predictive effects of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on young children’s social competence, and the mediating role of maternal parenting self-efficacy between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and young children’s social competence. This study aims to shed light on the influence and the internal process of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on young children’s social competence, so that nurturers could make full use of the advantages and overcome the negative influences of this coparenting mode to promote young children’s social development.

Method

Participants

Questionnaires were distributed to mothers of 372 preschool children in Guangzhou and Xi’an, China. In order to identify co-parenting families, first, we emphasized the definition of parent-grandparent coparenting in the instruction section of the scale, let the participants know what was parent-grandparent coparenting. Second, participants were asked whether grandparents undertake parts of responsibilities in childrearing, e.g., daily life care, emotional care, discipline, play, and so on. If the answer is yes, then they continue to fill in the scales. 38 mothers reported no parent-grandparent coparenting in childrearing, 17 mothers reported coparenting with other people such as babysitters and relatives, and 317 reported parent-grandparent coparenting in childrearing (144 from Guangzhou, and 173 from Xi’an), accounting for 85.2%. In parent-grandparent coparenting families, mothers aged 27 to 50 years, with an average age of 34.16 (SD = 3.27); 88.1% of them had junior college degree or above, and 93.0% of them had full-time jobs. Fathers aged 30 to 53 years, with an average age of 36.55 (SD = 3.80); 90.3% of them had junior college degree or above, and 99.0% of them had full-time jobs. The grandparents aged 49 to 83 years, with an average age of 61.81 (SD = 5.13), and maternal and paternal grandmothers accounted for 90.8% of grandparents. Among the children, there were 153 boys and 164 girls with an average age of 4.73 (SD = .56), and 81.3% of them were the only child in their family. 52.2% participating families that grandparents lived with parents and children. Families with an annual income of RMB100,000 (about $14,400 USD) and above accounted for 59.6%. According to the data of the National Statistical Bureau of the People’s Republic of China (2018), they belong to middle or high income families.

Six months later, we conducted a follow-up study of 179 families (78 from Guangzhou, response rate was 54.2%; 101 from Xi’an, response rate was 58.4%). Mothers aged 27 to 50, with an average age of 34.56 (SD = 3.23); 89.9% of them had junior college degree or above, and 92.7% of them had full-time jobs. Fathers aged 30 to 53, with an average age of 36.66 (SD = 5.13); 91.9% of them had junior college degree or above, and 98.8% of them had full-time jobs. Grandparents aged 49 to 80, with an average age of 61.46 (SD = 5.23), and maternal and paternal grandmothers accounted for 90.5% of grandparents. There were 83 boys and 96 girls with an average of 4.77 (SD = .54), and 80.4% of them were the only child in their family. 52.8% participating families that grandparents lived with parents and children.

Procedure

The proposal of the present study was approved by the institutional ethical review committee. Participants were recruited from two preschools in urban areas of Guangzhou and Xi’an, China. Guangzhou is located in southern China, and is the third largest city in China. Xi’an is a medium-sized city in the western region of China. Two preschools were selected by a clustered random sampling method. One preschool was randomly selected from the list of preschools in each city. Then, we contacted the preschool principals and acquired permission from them. Before asking for parents’ consent to participate, all family members were well informed about the purpose of the study and they were assured for the confidentiality of their responses. Parents were asked to sign the consent form if they want to participate in the study. Then, trained researchers explained how to fill in the questionnaires to parents when they came to school to pick up their children and asked mothers to complete. Parents were also asked to seal the completed questionnaires in an envelope and return them to class teachers within one week. Then, the researcher gathered all the returned questionnaires. Six months later, researchers sent an invitation letter and a consent form to families who participated in Wave 1, the mothers participated in the follow-up study filled in a questionnaire assessing children’s social competence. The result of the t-test of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship in seven dimensions showed no significant differences between the families that participated in the follow-up study and the families that did not. All the participants received a small gift.

Measures

Parent-grandparent coparenting relationship

Mothers rated their own coparenting relationship with grandparents on the Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS) using a 7-point scale with items from 1 (not true) to 7 (very true) (Feinberg 2003). The scale consists of 35 items in seven dimensions: coparenting agreement, coparenting closeness, exposure of child to conflict, coparenting support, endorsement of partner’s parenting, coparenting undermining and division of labor. It should be noted that the CRS was originally developed to measure father and mother coparenting, so adjustments were made to measure parent-grandparent coparenting. E.g., changed “My partner and I have the same goals for our child” into “The grandparent and I have the same goals for our child”, changed “My partner does not trust my abilities as a parent” into “The grandparent does not trust my abilities as a parent”. In this study, Cronbach’s α values of the seven dimensions were .71, .75, .87, .86, .84, .79, and .67 respectively; confirmatory factor analysis showed that χ2/df = 2.12, RMSEA = .06, NFI = .90, CFI = .93, NNFI = .90, and GFI = .91.

Maternal parenting self-efficacy

Mothers rated their own parenting self-efficacy on Parenting Self-Efficacy Scale using a 6-point scale with items rated from 1 (not confident) to 6 (very confident) (Suzuki et al. 2009). The scale consists of 25 items in two subscales: maternal strategies efficacy subscale (e.g., control your emotions in front of your child) and child outcomes efficacy subscale (e.g., teach your child to get along with others). It has been used in Chinese sample, showing good reliability and validity (Li and Wei 2017). In this study, Cronbach’s α values of the two dimensions were .88 and .94 respectively.

Children’s social competence

The Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation Scale (LaFreniere and Dumas 1996) is a 6-point scale to assess young children’s social competence and behavior. This study involves 10 items in the dimension of social competence. It is rated from 1 (never) to 6 (always). The scale has good reliability and validity in Chinese children (Liu et al. 2012; Liang et al. 2013). The Cronbach’s α value of the dimension of social competence was .76 in Wave 1 and .85 in Wave 2 six months later.

Data Analyses

Frist, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were computed. Then, structural equation modeling with a bootstrap resample of 1000 was concluded separately to analyze the proposed models for parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy, and children’s social competence in the cross-sectional study and the six-month follow-up study in Mplus. Missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood. Maternal education level and child age were used as control variables in all models. Young children’s social competence in Wave 1 were controlled in predicting children’s social competence in Wave 2. Maternal age and child gender were not included as control variable, because no statistically significant differences were found in social competence. Significance of effect was determined by the 95% CI generated through resampling 1000 random samples by the bootstrapping approach.

Results

To control common method variance (CMV), strict process control was adopted. Emphasizing that the questionnaires would be only used for research and be filled in anonymously, the information provided would be kept confidential, and questionnaires were arranged in random order and scored in different ways (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Harman’s single-factor test was also conducted. The results showed that 18 factors had an eigenvalue larger than 1 and the explained variance ratio of the first factor was 22.58%, lower than the 40% threshold, meaning that CMV was not significant.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Except correlation between exposure of child to conflict and child’s social competence (W2), and correlation between coparenting undermining and child outcomes efficacy, correlations between the other variables were statistically significant.

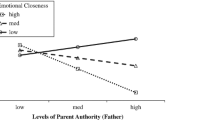

Structural equation modeling was used to examine the mediating role of maternal parenting self-efficacy between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and young children’s social competence in Wave 1 and Wave 2. The resulting standardized coefficients for tested models were shown in Figs 1 and 2. According to the first structural model, maternal parenting self-efficacy was a partial mediator between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and child’s social competence. According to the second structural model, when children’s social competence in Wave 1 was controlled, child outcomes efficacy, a dimension of maternal parenting self-efficacy, played a role of full mediation between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and child’s social competence.

As shown in Fig. 1, the model with maternal strategies efficacy and child outcome efficacy as mediators fit the data well. χ2/df = 2.14, p = .001, CFI = .98, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04. And as shown in Fig. 2, after control children’s social competence in Wave 1, the model with child outcome efficacy as a mediator fit the data well too. χ2/df = 2.54, p = .01, CFI = .94, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .06.

We next considered some focal indirect effects. To obtain the inference statistics, we followed the approach recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008) and applied bias-corrected bootstrapping 1000 samples to determine the 95% CI. They suggest that one can conclude a mediation effect has occurred when the product of the path between the independent variable and the mediator (called path a) and the path between the mediator and the dependent variable (called path b) is statistically significant. This approach has been recommended because it has greater power and better controls for Type I errors (MacKinnon et al. 2002). We found that maternal strategies efficacy (ab = .06) and child outcome efficacy (ab = .14) mediated the effect of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and children’s social competence (W1). The bootstrapping confidence intervals for these two indirect effects excluded zero (95% CI = [.02, .10], p = .006 for maternal strategies efficacy and 95% CI = [.01, .08], p = .002 for child outcomes efficacy), suggesting that these mediating effects were statistically significant in nature. In addition, child outcome efficacy mediated the effect of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on children’s social competence (W2) (ab = .07). The indirect paths from parent-grandparent coparenting relationship to children’s social competence (W2) was significant (95% CI = [.03, .12], p = .003). In sum, all mediating relationships hypothesized by our proposed model received support.

Discussion

Based on family systems theory and coparenting ecological model, this study examined the influences of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship on young children’s social competence, and the mediating role of maternal parenting self-efficacy between them. Structural equation modeling with data from cross-sectional study found that maternal parenting self-efficacy was a partial mediator between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and young children’s social competence. In other words, a harmonious coparenting relationship had a significant positive influence on young children’s social competence in a direct way, and could promote such competence indirectly through improving maternal strategies efficacy and child outcomes efficacy, two dimensions of maternal parenting self-efficacy. Our results were in line with existing research outcomes (Barnett et al. 2011; LeRoy et al. 2013), and provided empirical support for family systems theory and coparenting ecological model. The possible reasons for the direct, positive influence of coparenting relationship on children’s social competence were as follows. On the one hand, harmonious coparenting relationship and good social interaction between parent and grandparent set an example for children and provide lots of opportunities for observing how to engaging and interacting with others. On the other hand, the explanation for the current findings lies within the role of grandparent in a combined family system. Grandparents often undertake part of responsibilities in child rearing, provide care and social support, and interact with their grandkids sensitively and frequently, which may make young children acquire better social skills in the interactions with grandparents (Akhtar et al. 2017; Barnett 2008).

Structural equation modeling of the cross-sectional study also found that parent-grandparent coparenting relationship could promote children’s social competence indirectly through improving maternal strategies efficacy and child outcomes efficacy. Self-efficacy is influenced by past experiences, encouragement, modeling and such variables as stress, anxiety, or depression (Bandura 1997). The most straightforward explanation could be that grandparents offered mothers a kind of positive social support which could influence maternal self-efficacy through processes involving opportunities to observe grandparents’ parenting, verbal persuasion and encouragement, and share the responsibilities of parenting. Grandparents have rich experiences in child rearing, it is easier for them to translate past experiences into current parenting practices (King and Elder 1997). In the process of coparenting with mothers, they share experiences, demonstrate how to deal with related things, and give appropriate feedback and encouragement. Mothers could acquire lots of knowledge and learn some parenting strategies by observing what grandparents were doing which strengthened their parenting self-efficacy (Lesniowska et al. 2016). In addition, in families where grandparents helped take care of children in daily life and accompanied them on the way to and from preschool, the parenting burden and pressure of mothers were greatly reduced (Goh and Kuczynski 2010), this made mothers raising their children with a relaxed and positive way, and then boost mothers’ parenting self-efficacy (Gao et al. 2014). Mothers with high parenting self-efficacy more likely to be successful in establishing a warm and sensitive relationship with their children and be able to understand the needs of their kids and respond appropriately (Abarashi et al. 2014; Roskam et al. 2016). In the process of child rearing, mothers with high parenting self-efficacy not only directly demonstrated to their children how to interact with others and how to adjust their own emotions, but also exerted a potential influence on children by setting an example of respect, equality, mutual aid and sharing, thus promoting their social competence (Junttila et al. 2007).

The six-month follow-up study found that mothers’ child outcomes efficacy, a dimension of maternal parenting self-efficacy, played a role of full mediation between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and child’s social competence in Wave 2 when children’s social competence in Wave 1 was controlled. In other words, parent-grandparent coparenting relationship could promote children’s social competence in Wave 2 by influencing mothers’ child outcomes efficacy. This suggested that mothers’ child outcomes efficacy played a crucial role in developing the social competence of children (Akhtar et al. 2017). One possible reason is that, from a long-term perspective, a harmonious coparenting relationship between parent and grandparent make mothers fell supported and have confidence in teaching her child an age-appropriate task and supporting their children’s social-emotional and cognitive development. When mothers are full of efficacy on the development of children, they will express more positive affect, less irritability, more enthusiasm, and persistence towards parenting which can effectively improve the quality of mother-child interaction and boost the social competence of children (Mouton and Roskam 2015; Wilson et al. 2014). Another possible reason is that mothers having high child outcomes efficacy tend to report higher children’s social competence (Coleman and Karraker 2010).

The mediating effect of maternal strategies efficacy between parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and child’s social competence was not found in the six-month follow up study. Contextual and sampling factors should be considered here. A study by Elder et al. (1995) demonstrated that although African American and Caucasian parents had similar levels of parenting strategies efficacy, the African American parents engaged in greater use of parenting strategies both that promote adaptive child development and protect children from risk that may lead to negative outcomes. The researchers concluded this difference was due to the perception of some African American parents that the community is unresponsive, thus prompting high efficacy parents to take on the role of strongly promoting and protecting their children. However, in the present study, most of the mothers who were well-educated, middle-class women, were in advantaged child-rearing contexts, where there were parent-grandparent coparenting at home, finances were stable, there are numerous positive factors likely to enhance parenting and children’s development, rendering mothers’ strategies efficacy a potentially less salient correlate of outcomes (Jones and Prinz 2005).

Our findings deepened our understanding of associations among parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy and children’s social competence, supported family systems theory and coparenting ecological model which proposed that good relationship between family members other than the immediate family (i.e., parents or siblings) were related to better adjustment of children. Children, mothers and families could benefit from harmonious parent-grandparent coparenting relationship (Chen 2016).

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of the present study need to be noted. First, the variables in this study were measured by mother report and the perception of grandparent is not covered. Because of the traditional concept that “domestic shame should not be made public”, social desirability bias may be unavoidable. Thus, future studies should adopt multiple methods or multiple sources of information to accurately measure these variables. Regional and cultural diversity is another limitation for generalization of results of the present study. The study shall be replicated in families in different regions and with different cultural backgrounds. A third limitation is that though we used six-month follow-up study, a longer-term follow-up study might result in a better understanding of parent-grandparent coparenting relationship and maternal parenting self-efficacy’s roles in psychosocial development of young children. Fourth, there are different patterns of parent-grandparent coparenting in different families, and the level of grandparents’ involvement varies (Poblete and Gee 2018), therefore, it is an important area for future research to examine the role of different levels of parent-grandparent coparenting is linked to maternal self-efficacy and children’s development.

References

Abarashi, Z., Tahmassian, K., Mazaheri, M. A., Panaghi, L., & Mansoori, N. (2014). Parental self-efficacy as a determining factor in healthy mother-child interaction: a pilot study in Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 8(1), 19–25.

Akhtar, P., Malik, J. A., & Begeer, S. (2017). The grandparents’ influence: parenting styles and social competence among children of joint families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(2), 603–611.

Baker, J., McHale, J., Strozier, A., & Cecil, D. (2010). Mother-grandmother coparenting relationships in families with incarcerated mothers: a pilot investigation. Family Process, 49(2), 165–184.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 729–735.

Barnett, M. A., Mills-Koonce, W. R., Gustafsson, H., & Cox, M. (2012). Mother-Grandmother conflict, negative parenting, and young children’s social development in multigenerational families. Family Relations, 61(5), 864–877.

Barnett, M. A., Scaramella, L. V., McGoron, L., & Callahan, K. (2011). Coparenting cooperation and child adjustment in low-income mother-grandmother and mother-father families. Family Science, 2(3), 159–170.

Barnett, M. A., Scaramella, L. V., Neppl, T. K., Ontai, L. L., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Grandmother involvement as a protective factor for early childhood social adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 635–645.

Barnett, M. A., the Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2008). Mother and grandmother parenting in low-income three generation rural households. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(5), 1241–1257.

Bloomfield, L., & Kendall, S. (2012). Parenting self-efficacy, parenting stress and child behaviour before and after a parenting programme. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 13(4), 364–372.

Chen, W. C. (2016). The role of grandparents in single-parent families in Taiwan. Marriage and Family Review, 52(1-2), 41–63.

China Research Center on Aging (2012). A compilation of survey data on the system of elderly support for the elderly in China. Vol. 132. Beijing, China: Huangling Press.

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (2000). Parenting self-efficacy among mothers of school-age children: Conceptualization, measurement, and correlates. Family Relations, 49(1), 13–24.

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (2010). Maternal self-efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers’ behavior and developmental status. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(2), 126–148.

Elder, G. H., Eccles, J. S., Ardelt, M., & Lord, S. (1995). Inner city parents under economic pressure: perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(3), 771–784.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: a framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131.

Fergusson, E., Maughan, B., & Golding, J. (2008). Which children receive grandparental care and what effect does it have? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(2), 161–169.

Gao, L., Sun, K., & Chan, S. W. (2014). Social support and parenting self-efficacy among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Midwifery, 30(5), 532–538.

Giallo, R., Treyvaud, K., Cooklin, A., & Wade, C. (2013). Mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in home activities with their children: psychosocial factors and the role of parental self-efficacy. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 343–359.

Goh, E. C. L. (2006). Raising the precious single child in urban China: an intergenerational joint mission between parents and grandparents. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 4(4), 6–28.

Goh, E. C. L., & Kuczynski, L. (2010). Only children and their coalition of parents: considering grandparents and parents as joint caregivers in urban Xiamen, China. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(4), 221–231.

Guo, X. (2014). The influence of grandparenting on cognitive development among children: a longitudinal study. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22(6), 1072–1076+1081.

Holloway, S. D., Campbell, E. J., & Nagase, A., et al. (2016). Parenting self-efficacy and parental involvement: Mediators or moderators between socioeconomic status and children’s academic competence in Japan and Korea? Research in Human Development, 13(3), 258–272.

Jia, R., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2011). Relations between coparenting and father involvement in families with preschool-age children. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 106–118.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: a review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363.

Junttila, N., Vauras, M., & Laakkonen, E. (2007). The role of parenting self-efficacy in children’s social and academic behavior. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(1), 41–61.

King, V., & Elder, Jr, G. H. (1997). The legacy of grandparenting: childhood experiences with grandparents and current involvement with grandchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59(4), 848–859.

LaFreniere, P. J., & Dumas, J. E. (1996). Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: The short form (SCNE–30). Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 369–377.

Lavers, C. A., & Sonuga-Burke, E. J. (1997). Annotation: on the grandmothers’ role in the adjustment and maladjustment of grandchildren. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(7), 747–753.

LeRoy, M., Mahoney, A., Pargament, K. I., & DeMaris, A. (2013). Longitudinal links between early coparenting and infant behaviour problems. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 360–377.

Lesniowska, R., Gent, A., & Watson, S. (2016). Maternal fatigue, parenting self-efficacy, and over reactive discipline during the early childhood years: a test of a mediation model. Clinical Psychologist, 20(3), 109–118.

Li, X., & Wei, X. (2017). Father involvement and children’s social competence: Mediating effects of maternal parenting self-efficacy. Journal of Beijing Normal University, 62(5), 49–58.

Liang, Z., Zhang, A., Zhang, G., Song, Y., Deng, H., & Lu, Z. (2013). A longitudinal study on relations between parents’ marital quality and children’s behavior problems: moderating effect of children’s effortful control. Psychological Development and Education, 5, 525–532.

Liu, Y., Song, Y., Liang, Z., Bai, Y., & Deng, H. (2012). Evaluation of social competence and behavior of urban children in China. Journal of Southeast University, 31(3), 268–273.

Liu, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2013). Effects of grandparenting on preschool children’s emotion regulating strategies. Studies in Preschool Education, 2, 37–42.

McHale, J., Lauretti, A., Talbot, J., & Pouquette, C. (2002). Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In J. P. McHale & W. S. Grolnick (Eds.), Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families. (pp. 127–166). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

Majdandžić, M., Vente, W. D., Feinberg, M. E., Akta, E., & Bögels, S. M. (2012). Bidirectional associations between coparenting relations and family member anxiety: a review and conceptual model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(1), 28–42.

Minuchin, P. (1988). Relationships within the family: A systems perspective on development. In R. Hinde & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual influences (pp. 7–26). Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

Mouton, B., & Roskam, I. (2015). Confident mothers, easier children: a quasi-experimental manipulation of mothers’ self-efficacy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2485–2495.

Nagase, A. (2015). Revealing the pathway from couple relationship to children’s social competence: the role of life stress, parenting self-efficacy, and effective parenting. Berkeley: University of California. Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

National Statistical Bureau of the People’s Republic of China. (2018). Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2017. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201802/t20180228_1585631.html

Pittman, L. D., & Boswell, M. K. (2007). The role of grandmothers in the lives of preschoolers growing up in urban poverty. Applied Developmental Science, 11(1), 20–42.

Poblete, A. T., & Gee, C. B. (2018). Partner support and grandparent support as predictors of change in coparenting quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), 2295–2304.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effect in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Roskam, I., Brassart, E., Loop, L., Mouton, B., & Schelstraete, M. (2016). Do parenting variables have specific or widespread impact on parenting covariates? The effects of manipulating self-efficacy or verbal responsiveness. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 38(2), 142–163.

Settles, B. H., Zhao, J., Mancini, K. D., Rich, A., Pierre, S., & Oduor, A. (2009). Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: Emerging roles and exchanges in global perspectives. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(5), 827–848.

Suzuki, S., Holloway, S. D., Yamamoto, Y., & Mindnich, J. D. (2009). Parenting self-efficacy and social support in Japan and the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 30(11), 1505–1526.

Teun, G., Theo, V. T., Anne-Rigt, P., & Dykstra, P. A. (2015). Child care by grandparents: changes between 1992 and 2006. Ageing and Society, 35(6), 1318–1334.

Van Egeren, L. A., & Hawkins, D. P. (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 165–178.

Wilson, S. R., Gettings, P. E., Guntzviller, L. M., & Munz, E. A. (2014). Parental self-efficacy and sensitivity during playtime interactions with young children: unpacking the curvilinear association. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 42(4), 409–431.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a grant from the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 15CSH053): Parent-grandparent coparenting in urban families and its influence on young children’s social adjustment. We wish to thank the families who volunteered for the study for their time and effort. This study was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 15CSH053) to Xiaowei Li.

Author Contributions

L.X.: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. L.Y.: analyzed the data and wrote part of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Beijing Normal University and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Liu, Y. Parent-Grandparent Coparenting Relationship, Maternal Parenting Self-efficacy, and Young Children’s Social Competence in Chinese Urban Families. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1145–1153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01346-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01346-3