Abstract

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of rumination, experiential avoidance, dissociation and depressive symptoms in the association between daily peer hassles and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents. Additionally, this study explored gender differences in these associations and tested whether the proposed model was invariant across genders. The sample consisted of 776 adolescents, of them 369 are males (47.6%) and 407 are females (52.4%), aged between 12 and 18 years old from middle and high schools in Portugal. Participants completed self-report questionnaires to assess daily peer hassles, rumination in its severe component (i.e., brooding), experiential avoidance, dissociation, depressive symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury. Path analysis showed that daily peer hassles indirectly impact on non-suicidal self-injury through increased levels of brooding, experiential avoidance, dissociation, and depressive symptoms. Results indicated significant gender differences in mean scores and path analysis. Male adolescents were more likely to engage in brooding and experiential avoidance in response to external distress (particularly, daily peer hassles), whereas female adolescents were more likely to engage in non-suicidal self-injury in response to internal distress (particularly, depressive symptoms). These findings suggest relevant preventive and intervention actions to address emotion dysregulation in adolescence, by teaching them acceptance and mindfulness skills as a way of coping with stressful experiences and internal distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is highly prevalent among adolescents and is associated with several psychological impairments and augmented risk for future suicide (Klonsky et al. 2013). NSSI refers to a deliberate and direct destruction of one’s body tissues for non-socially sanctioned reasons without suicidal intent (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Previous studies found prevalence rates ranging between 10 and 40% in community samples of adolescents and an onset age for NSSI ranging between 12 and 16 years old (Klonsky et al. 2011; Nock 2010). Regarding gender differences there are mixed results, still there is a general trend in finding that female adolescents report engaging more frequently in NSSI (Bresin and Schoenleber 2015; Klonsky et al. 2011).

Although several distal risk factors have been identified in the development of NSSI, including family environment, early life events and temperament, there are proximal vulnerabilities that may trigger and maintain NSSI. Among these proximal factors, daily life hassles may play a prominent role. Daily hassles are the frustrating and irritating everyday experiences that occur during transactions with the environment (e.g., family, peers, school and neighborhood; Seidman et al. 1995). Daily life hassles are common chronic stressors that affect individuals’ psychological adjustment (Pinquart 2009). Research conducted in samples of adolescents showed that daily life hassles are associated with maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies (Garnefski et al. 2003), depressive symptoms, substance use (Bailey and Covell 2011) and suicidal ideation (Mazza and Reynolds 1998). Recently, some studies found that high levels of current life stressors prospectively predict NSSI (Hankin and Abela 2011; Liu et al. 2014), especially interpersonal stressors (Guerry and Prinstein 2009; Jutengren et al. 2011). Given that the transition to adolescence is mainly characterized by a shift in social affiliation from family to peer approximation (Steinberg and Morris 2001), stressful experiences in peer group may be a source of stress for adolescents. For instance, when experiencing negative emotional states, adolescents who perceived moderate and high levels of daily peer hassles are more likely to engage in NSSI (Xavier et al. 2016a). According to Nock (2010), when exposed to stressful life events, individuals who experience both physiological hyperarousal activation and difficulties in emotion regulation may be particularly at risk for engaging in NSSI as a maladaptive coping strategy. Such predisposing characteristics may include poor interpersonal problem-solving skills (Nock and Mendes 2008), rumination (Hilt et al. 2008) and self-criticism in its most severe form—hated self (Xavier et al. 2016). It seems that the way individuals respond to stress through mal-adaptive emotion regulation processes may increase depressive symptoms and dysfunctional behavior patterns (Garnefski et al. 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema 2012). Specifically, avoidance-focused emotion regulation processes, namely rumination, experiential avoidance and dissociation, may be key mediating psychological mechanisms in the relationship between daily peer hassles and depressive symptoms and NSSI.

Rumination is a response to distress that involves the tendency to brood and reflect on “the symptoms of depression and on the causes, meanings, and consequences of those symptoms” (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991, p. 569) and has been found to exacerbate and prolong depressive symptoms in adolescence (Abela and Hankin 2011). Female adolescents tend to endorse higher levels of ruminative response style than male adolescents and this trend may help to explain gender differences in depression during adolescence (Nolen-Hoeksema 2001). According to Treynor et al. (2003), rumination is a multi-dimentional construct that may be distinguished between harmful and helpful sub-types of ruminative thought (brooding vs. reflection). Indeed, rumination is considered a maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategy, especially when it takes the form of brooding (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008; Treynor et al. 2003), as it is implicated on several aspects of both mental and physical health (Smith and Alloy 2009). Moreover, rumination may function as an avoidant coping strategy, as individuals may avoid dealing with emotionally threatening material through rumination, albeit doing so increases their negative affect (Giorgio et al. 2010; Smith and Alloy 2009). Ruminative response style has been associated with NSSI (Hoff and Muehlenkamp 2009) and serves both as a moderator and mediator variable. For instance, rumination had a moderator effect in the relationship between depressive symptoms and NSSI among female early adolescents (Hilt et al. 2008). Selby Connell and Joiner (2010) found a significant interaction between rumination and painful or provocative life events to explain NSSI among college students. A recent study showed that ruminative thinking is an underlying mediator mechanism in the association between stressful life events and psychological distress and NSSI among adolescents (12–18 years-old; Voon et al. 2014).

Another transdiagnostic process that may be implicated in the development and maintenance of psychopathology is experiential avoidance (EA). EA is defined as the “phenomenon that occurs when a person is unwilling to remain in contact with particular private experiences and takes steps to alter the form or frequency of these events and the contexts that occasion them” (Hayes et al. 1996; p. 1154). NSSI may be included in the broader class of experiential avoidance behaviors, as it is usually served the purpose of escaping, managing and regulating emotions, resulting in a temporary emotional relief, but leading to long-term impairments (Chapman et al. 2006). Various studies conducted with adult populations suggest that EA may serve as a mediator of the impact of stressful events on poor outcomes (e.g., Biglan et al. 2008). For example, aversive and shaming experiences in childhood and adolescence are associated with increases in EA, which in turn will affect psychopathology (e.g., depressive symptoms; Carvalho et al. 2015). Although empirical research are still scant, a few studies on EA during adolescence showed that female adolescents tend to report more levels of experiential avoidance than male adolescents (Biglan et al. 2015; Greco et al. 2008; Howe-Martin et al. 2012). Regarding correlational studies conducted with adolescents’ community samples, EA has been associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, social comparison (Cunha and Santos 2011) and lower quality of life (Greco et al. 2008). Moreover, EA is longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms and is more likely in adolescents who report family conflicts (Biglan et al. 2015). Other study found that adolescents with a history of NSSI and other functionally equivalent behaviors (e.g., eating disturbance, substance abuse) reported more chronic experiential avoidance than those who reported not engaging in those behaviors (Howe-Martin et al. 2012). Furthermore, EA predicted severity of borderline symptoms at 1-year follow-up, controlling for baseline levels of borderline, anxiety and depressive symptoms (Sharp et al. 2015). Studies on the mediating role of EA in adolescence are still lacking, but two studies have found that EA exert an indirect effect between stressful experiences (e.g., child maltreatment; daily school and peer hassles) and psychopathology (e.g., depression, PTSD symptoms) (Shenk et al. 2012; Xavier et al. 2015).

Dissociation refers to the avoidance of reality, to a deficit in accessibility to memory and knowledge, and in the integration of behavior and sense of the self (American Psychiatric Association 2013), often in response to severe traumatic events. Alternatively, EA is a broader construct, transversal to specific emotional regulation strategies, because it does not focus on a specific form of action nor on a particular response, but rather on the function of emotion regulation (Boulanger et al. 2010; Hayes et al. 1996; Kashdan et al. 2006). There is a paucity of empirical studies that examine the relationship between dissociation and EA. An exception is the study in adult population conducted by Marx and Sloan (2005) demonstrating that peritraumatic dissociation and experiential avoidance were significantly related to each other, and this last one significantly predicted the severity of PTSD symptomatology. Dissociative experiences are commonly psychological responses aiming at coping with severe trauma (Putman 1996) and are frequently associated with other mental health difficulties (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficits) (e.g., Ozdemir et al. 2015). Furthermore, there is empirical evidence that dissociation mediates the relationship between trauma experiences (e.g., child maltreatment) and psychopathology, including NSSI (e.g., Rallis et al. 2012; Swannell et al. 2012). These studies suggest that previous trauma and current stress may trigger dissociative experiences into avoiding intolerable emotions, thoughts and memories, which in turn may lead to NSSI as a way to escape from unpleasant states of dissociation, numbness or emptiness (Chapman et al. 2006; Klonsky 2007; Rallis et al. 2012).

Considering this theoretical and empirical background, the present study tests a model with multiple mediators where emotion dysregulation processes, such as rumination (specifically brooding component), experiential avoidance and dissociation, function as mediators on the relationship between daily peer hassles and psychopathology (particularly, depressive symptoms and NSSI). More specifically, the current study aims to test a hypothesized model in which daily peer hassles would impact on NSSI through avoidance-focused emotion regulation processes (namely, brooding, experiential avoidance and dissociation) and depressive symptoms. In the same model, it is tested whether these avoidance-focused emotion regulation processes would impact upon NSSI through depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the current study also aims to test whether this explanatory model of NSSI is equal or vary across gender. We hypothesized that adolescents who perceived greater daily hassles with their peers are more likely to brood, avoid and dissociate and experience depressive symptoms, which in turn impacts upon NSSI. We also expected that the effect of daily peer hassles on depressive symptoms occurs through rumination, EA and dissociation. Additionally, it was hypothesized that avoidance-focused emotion regulation processes are associated with NSSI through their effect on depressive symptoms. Given the theoretical conceptualizations on gender differences of emotion regulation in adolescence (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema 2001, 2012), we hypothesized that the associations between daily peer hassles, rumination, EA, dissociation, depressive symptoms and NSSI would differ for adolescent males and females.

Method

Participants

The sample included 776 adolescents, of them 369 are males (47.6%) and 407 are females (52.4%). Participants are aged between 12 and 18 years old (M = 14.55, SD = 1.76) and were recruited from 7th to 12th grade in middle and secondary schools (mean of years of education = 9.45, SD = 1.61) in Portugal. No gender differences were found for age, t (774) = 1.069, p = .286, but significant gender differences existed for years of education, t (774) = 2.417, p = .016. Female adolescents had more years of education (M = 9.58, SD = 1.63) than male adolescents (M = 9.30, SD = 1.58).

Results from G*Power calculations for correlations, t-test and linear multiple regression analyses, assuming a p value = 0.05, an effect size of f = 0.15, with a statistical power of 0.95, recommend a sample size ranging from 89 to 210.

Procedure

The sample recruitment was through non-probability sampling method, i.e. convenience sample. Nevertheless, participants were recruited from seven different independent schools. After obtaining ethical approvals from Portuguese Commission for Data Protection and Ministry of Education, schools in the central region of Portugal were contacted to participate in the study. The Head Teacher and the parents were informed and gave written consent. All adolescents enrolled in the study were fully informed about the goals of the study and the aspects of confidentiality. Adolescents consented to participate and filled out voluntarily the instruments in the classroom in the presence of the teacher and researcher. The researcher provided clarifications about the questionnaires when requested. Participants who did not want to participate or were not authorized by their parents to participate in this study were given an academic task by the teacher in the classroom.

Measures

The Daily Hassles Microsystem Scale (DHMS; Seidman et al. 1995; Portuguese version: Paiva 2009) is a self-report questionnaire composed by 25 items that assess the perceived daily hassles within four microsystems. Respondents answer to each event how much of hassles it was in the last month on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all a hassles; 4 = a very big hassles). In the present study only peer hassles subscale was used, which represents troubles and conflicts with friends (4 items; e.g., “Trouble with friends over beliefs, opinions and choices.”; “Being left out of activities or ignored by other kids.”). In the original study (Seidman et al. 1995) the daily peer hassles subscale had an adequate internal consistency (α = .71). In the current study the internal consistency for daily peer hassles subscale was also adequate (α = .72).

The Ruminative Responses Scale – short version (RRS; Treynor et al. 2003; Portuguese version for adolescents: Xavier et al. 2016b) is a 10-item scale that measures the individual’s tendency to ruminate when in a sad or depressed mood. Originally designed for adults, the RRS has been administered in prior studies to adolescents, demonstrating good psychometric properties in youngster population. In the current study only brooding subscale (5 items) was used to assess the passive and judgmental pondering of one’s mood because it is considered the maladaptive component of rumination. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (1 = almost never to 4 = almost always). In the original version, the Cronbach’s alpha for brooding subscale was .77 (Treynor et al. 2003). This subscale also had adequate internal consistency in adolescents’ sample (α = .80; Xavier et al. 2016b). In the current study the brooding subscale presented a Cronbach’s alpha of .80.

The Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (AFQ-Y; Greco et al. 2008; Portuguese version: Cunha and Santos 2011) is a 17-item self-report questionnaire that was based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy’s model to assess psychological inflexibility through cognitive fusion (e.g., “My thoughts and feelings mess up my life.”) and experiential avoidance (e.g., “I push away thoughts and feelings that I don’t like”). Items responses are rated on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all true; 4 = very true). The AFQ-Y is a unidimentional scale, with higher total scores indicating higher experiential avoidance/cognitive fusion. Greco et al. (2008) found good internal reliability (α = .90). The Portuguese version also found adequate internal consistency (α = .82). In the current study the AFQ-Y presented a Cronbach’s alpha of .89.

The Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (A-DES-II; Armstrong et al. 1997; Portuguese version: Espirito-Santo et al. 2014) is a 30-item self-report questionnaire that assesses dissociative experiences. The A-DES-II items can be grouped into four domains reflecting basic aspects of dissociation (experiences of dissociative amnesia; absorption and imaginative involvement; passive influence; and despersonalization and derealization) and can be used as a total score. Each item is rated on 11-point scale (from 0 = never to 10 = always) and higher scores representing high levels of dissociative experiences. Armstrong et al. (1997) found a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 for the total score. In the present sample the Cronbach’s alpha was .94.

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995; Portuguese version: Pais-Ribeiro et al. 2004) is a self-report measure composed of 21 items to assess symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. The items indicate negative emotional symptoms and are rated on a 4-point scale (0–3) during the last week. Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) found the subscales to have high internal consistency (α = .91 for depression; α = .84 for anxiety; α = .90 for stress). In the present study only the depression subscale (7 items) was used and presented good internal consistency (α = .90).

The Risk-taking and Self-harm Inventory for Adolescents (RTSHIA; Vrouva et al. 2010; Portuguese version: Xavier et al. 2013) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses simultaneously risk-taking and self-harm behaviors. In the present study only the Self-harm dimension was used to measures the frequency of intentional self-injury behaviors (e.g., cutting, burning or biting). The items are rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never; 3 = many times), referring to the lifelong history. There is also one categorical item to assess the absence or presence of NSSI, following by a question about the part(s) of the body that were deliberately injured and a question about when it happened (in the last month; in the last three months; and more than three months), if applicable. In the present study, items 32 and 33, which assess suicidal ideation and intent respectively, were not included in the overall sum of NSSI and prior to analyses four respondents were excluded from data set because they reported suicidal intent. Vrouva et al. (2010) found a good internal consistency for self-harm dimension (α = .93). In the current study the self-harm dimension (15 items) presented a good internal reliability (α = .88).

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Software (Predictive Analytics Software, version 18, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and AMOS Software (Analysis of Moment Structures, version 18, AMOS Development Corporation, Crawfordville, FL, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed to analyze demographic variables and means scores on all variables. Gender differences were tested using independent-samples t-tests (Field 2013). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were performed to explore the relationships between all variables in the study (Field 2013).

Path analysis was performed to estimate the presumed relations among variables in the proposed theoretical model. This technique from structural equation modelling (SEM) considers theoretical causal relations among variables that have already been hypothesized (Kline 2005). In the path model tested, it was examined whether daily peer hassles would impact upon the frequency of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), mediated by brooding, experiential avoidance (EA), dissociation and current depressive symptoms. Additionally, it was tested whether brooding, EA and dissociation would impact upon NSSI, mediated by depressive symptoms. The Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method was used (Kline 2005). The following goodness-of-fit indexes were analyzed to evaluate overall model fit: Goodness of Fit Index (GFI ≥ .95, good), Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ .95, good), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI ≥ .95, good), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ .05, good fit; ≤ .08, acceptable fit; ≥ .10, poor fit), with 95% confidence interval (CI) (Hu and Bentler 1999). Significance tests of indirect effects were performed using Bootstrap sampling with 2000 samples and bias-corrected confidence levels set at .95 (Hayes and Preacher 2010; Kline 2005).

A multi-group analysis was performed to test whether path coefficients in the model are equal or invariant for groups (i.e., males vs. females) (Byrne 2010). The comparison between the unconstrained model (i.e., with free structural parameter coefficients) and the equality constrained model (i.e., where the parameters are constrained equal across groups) was analyzed through the chi-square difference test statistic (Byrne 2010). The critical ratio difference method provided by AMOS software was calculated to test for differences between male and female adolescents among all parameter estimates and critical ratio values larger than 1.96 indicate a significant difference between genders on the corresponding parameter (Byrne 2010).

Results

Data were screened for univariate normality and there were no severe violations to normal distribution (ǀSkǀ < 3 and ǀKuǀ < 8–10; Kline 2005). To inspect for possible multivariate outliers Mahalanobis Distance squared (D 2) were used and some extreme observations were excluded (6 cases considered as outliers). Missing data at random were minimal (less than 5% of cases) and the regression imputation method available in AMOS software was used. This approach for handling incomplete data has shown satisfactory performance (Schafer and Graham 2002). All analyses were performed with the completed data from the participants. Multicollinearity was examined by inspecting the tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF < 5) and no multicollinearity problems were found among variables (Kline 2005).

History of NSSI

In the current sample, approximately 22% of the adolescents reported engaging in NSSI at least once in their lifetime (n = 171) and of them 19% revealed engaging in NSSI in the last month (n = 32). The most common self-injured parts of the body endorsed by the adolescents were hands, arms, fingers and nails (n = 105, 62%). Additionally, female adolescents did significantly differ in frequency of NSSI, χ(1) = 14.403, p < .001, showing that females were more likely to endorse NSSI (n = 111, 27.3%) than males (n = 59, 16%).

Daily Peer Hassles, Avoidance-Focused Emotion Regulation Processes and NSSI

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of each variable for the full sample and by gender. Results showed that female adolescents have significantly higher levels of daily peer hassles, EA, brooding, depressive symptoms and NSSI than male adolescents. The effect sizes ranged between small and medium effects (cf. Table 1), according with Cohen’s guidelines (1988).

Table 2 shows the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients for all variables in study for male and females adolescents. As can be seen in Table 2, daily peer hassles is significantly associated with brooding, EA, dissociation, depressive symptoms and NSSI for both males and females. Brooding was significantly and moderately correlated with EA for both males and females. EA and dissociation were significantly correlated with each other and with depressive symptoms and NSSI.

How Daily Peer Hassles Affect Avoidance-focused Emotion Regulation Processes and Depressive Symptoms and NSSI

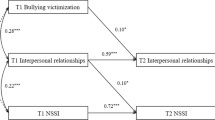

A path analysis was performed to test a sequential mediation model. The theoretical model was tested through a saturated or just-identified model, which comprised 26 parameters. Since this is a saturated model, its degrees of freedom are zero and the goodness-of-fit is perfect to the data. The following paths were not statistically significant: the direct effect of brooding on NSSI (b = -.012, SE = .056, Z = −0.217, p = .828, β = -.01); and the direct effect of EA on NSSI (b = .010, SE = .016, Z = 0.660, p = .509, β = .03). These non-significant paths were sequentially removed and the model was recalculated (with 24 parameters). The respecified model showed an excellent fit to the data, GFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .000, 95% CI [.000, .045], p = .965, and all paths were statistically significant. The model explained 15% of brooding, 16% of EA, 13% of dissociation, 42% of depressive symptoms and 28% of NSSI (Fig. 1).

Path diagram for the final model showing the associations between daily peer hassles, brooding, experiential avoidance, dissociation, depressive symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Standardized regression coefficients and multiple correlations coefficients are presented; all paths are statistically significant ( p < .001), except for the two paths drawn in dotted lines

Results showed that daily peer hassles had an indirect effect on NSSI, b = .21, 95% CI [.164, .264], p = .001, through brooding, EA, dissociation and depressive symptoms. Daily peer hassles also had a direct effect on NSSI (β = .12). There is also an indirect effect of daily peer hassles on depressive symptoms, b = .26, 95% CI [.215, .299], p = .001, through brooding, EA and dissociation. Daily peer hassles also had a direct effect on depressive symptoms (β = .16). Regarding the association between avoidance processes and NSSI, results indicate that brooding component of rumination had an indirect effect on NSSI, b = .08, 95% CI [.053, .123], p = .001, through depressive symptoms. Similarly, there was a significant indirect effect of EA on NSSI, b = .08, 95% CI [.047, .123], p = .001, through depressive symptoms. Dissociative experiences had a significant indirect effect on NSSI, b = .07, 95% CI [.039, .100], p = .001, through depressive symptoms. Additionally, dissociative experiences had a direct effect on NSSI (β = .19).

Gender Differences in the Relationships among Daily Peer Hassles, Brooding, EA, Dissociation, Depressive Symptoms and NSSI

The hypothesized model was tested by a multi-group approach to analyze gender differences in the relationships among daily peer hassles, brooding, EA, dissociation, depressive symptoms and NSSI. Results from the Chi-square difference test showed that the model was not invariant for both genders, χ2 dif(12) = 26.321, p = .010. For male adolescents, the model accounted for 20% of brooding, 17% of EA, 14% of dissociation, 43% of depressive symptoms and 26% of NSSI. For female adolescents, the model explained 10% of brooding, 13% of EA, 12% of dissociation, 39% of depressive symptoms, and 28% of NSSI. Results from critical ratios for differences among parameters indicated significant differences on three parameters. First, daily peer hassles was more strongly related to brooding for male adolescents than for female adolescents (z-score = −2.855, p < .01, β = .45 vs. β = .31, respectively). Second, the direct effect of daily peer hassles on EA was stronger for male adolescents than for female adolescents (z-score = −1.996, p < .05, β = .41 vs. β = .36, respectively). Third, depressive symptoms were more strongly associated to NSSI for female adolescents than male adolescents (z-score = 3.485, p < .01, β = .41 vs. β = .18, respectively).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether rumination, EA, dissociation and depressive symptoms mediate the tendency to engage in NSSI in response to daily peer hassles among a community sample of adolescents. Additionally, this study explored differences between male and female adolescents in daily peer hassles, avoidance-based emotion regulation strategies (i.e., rumination, EA and dissociation), depressive symptoms and NSSI, and tested whether the proposed model was invariant across genders.

The results of this study fit with previous findings showing that the prevalence rate of NSSI among community samples of adolescents is high and female adolescents are at a higher risk than male adolescents to engage in NSSI (e.g., Bresin and Schoenleber 2015). Moreover, there are important gender differences in how each gender perceives and responds to stressful daily experiences. Our findings reveal that female adolescents tend to perceive greater daily peer hassles than male adolescents. Additionally, rumination in its maladaptive component (i.e., brooding), experiential avoidance, dissociation and depressive symptoms are higher among female adolescents than male adolescents. Overall, these results are in line with previous research that shows the same pattern (e.g., Biglan et al. 2015; Greco et al. 2008; Howe-Martin et al. 2012; Nolen-Hoeksema 2001).

Findings in the present study converge with a substantial body of research, showing that daily peer hassles is a risk factor for depressive symptoms and NSSI (e.g., Liu et al. 2014; Xavier et al. 2016a). However, our results extend this prior work by showing the indirect effect of daily peer hassles on NSSI through avoidance-focused emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms. More specifically, adolescents who engage in brooding, EA and dissociation in response to daily peer hassles, tend to experience increased levels of depressive symptoms, which in turn impact on NSSI. Overall, these data suggest that, when confronted with daily stressful peer experiences, adolescents who are unable to deploy adaptive strategies to regulate negative emotional states and struggle with maladaptive cognitive and emotion strategies (e.g., rumination, experiential avoidance and dissociation) may experience depressive symptoms and engage in NSSI.

Moreover, the impact of brooding, EA and dissociation on NSSI occurred through increased levels of depressive symptoms. Additionally, dissociative experiences also had a direct effect on NSSI. These results are in accordance with the experiential avoidance model for NSSI proposed by Chapman et al. (2006), clarifying that NSSI is a behavior output that aims at regulating, escaping and generally avoiding thoughts, emotions, memories, sensations or other undesirable internal experiences, which in turn reduces or eliminates the emotional arousal. However, the association between emotional arousal and NSSI establish a vicious cycle through negative reinforcement that maintains NSSI over time (Chapman et al. 2006). Additionally, NSSI has been found to serve an antidissociation function. In other words, it seems that individuals may use self-injury to interrupt dissociative experiences and numbness (Chapman et al. 2006; Klonsky 2007; Rallis et al. 2012).

Furthermore, the current study is of key importance in understanding gender differences in the associations between daily peer hassles, rumination, EA, dissociation, depressive symptoms and NSSI. Indeed, results indicate that the relationship between daily peer hassles and brooding and EA is stronger in males than in females. When confronted with daily peer hassles, male adolescents display a high tendency to engage in brooding and to avoid internal experiences than female adolescents. On the other hand, the relationship between depressive symptoms and NSSI is stronger for females in comparison to males. It seems that female adolescents are more likely to respond to stress with internalizing emotions (e.g., depressive symptoms) and subsequently to engage in NSSI.

On the whole, these results are in line with existent theoretical frameworks on gender differences in depression in which women are suggested to be more vulnerable than men to develop depressive symptoms and other psychological disorders, even when confronted with similar stressors (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema 2001, 2012).The findings of the current study add to the current knowledge by showing gender differences in daily hassles, emotion regulation processes, depressive symptoms and NSSI in adolescence. While adolescent males are more likely to engage in brooding and EA in response to external distress (i.e., daily peer hassles), adolescent females are more likely to engage in NSSI in response to internal distress (i.e., depressive symptoms).

Limitations

Some limitations of the current study should be noted. Firstly, this study used a cross-sectional design, which implies that causal inferences cannot be drawn. Longitudinal research is needed to identify temporal relationships among variables that are associated with NSSI. Secondly, the study relied on self-report questionnaires and this methodology may lead to bias reporting (e.g., due to social desirability). Future studies should include other assessment methods to assess NSSI and life stressors, such as semi-structures interviews and ecological momentary assessment (EMA). Third, some self-report questionnaires using only a few items (e.g., daily peer hassles) may be limited to capture the variable under study, although the internal consistency was adequate. Fourth, future studies should evaluate the constructs of interest in the same temporal intervals (e.g., lifetime or in the last month). Finally, future studies should examine other types of daily hassles and its impact on adolescents’ lives. The model tested in the present study was intentionally restrained to analyze daily peer hassles since peer group plays an important role on adolescence and this variable has been found to be associated with NSSI (e.g., Xavier et al. 2016a).

References

Abela, J. R., & Hankin, B. L. (2011). Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022796.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Armstrong, J., Putnam, F. W., Carlson, E., Libero, D., & Smith, S. (1997). Development and validation of a measure of adolescent dissociation: The adolescent dissociative experience scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199708000-00003.

Bailey, S. J., & Covell, K. (2011). Pathways among abuse, daily hassles, depression, and substance use in adolescents. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 8, 4–14.

Biglan, A., Gau, J. M., Jones, L. B., Hinds, E., Rusby, J. C., Cody, C., & Sprague, J. (2015). The role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between family conflict and depression among early adolescents. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.12.001.

Biglan, A., Hayes, S. C., & Pistorello, J. (2008). Acceptance and commitment: Implications for prevention science. Prevention Science, 9, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-008-0099-4.

Boulanger, J. L., Hayes, S. C., & Pistorello, J. (2010). Experiential avoidance as a functional contextual concept. A. Kring & D. Sloan (eds.) Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology. (pp. 107–136). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bresin, K., & Schoenleber, M. (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009.

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Carvalho, S., Dinis, A., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Estanqueiro, C. (2015). Memories of shame experiences with others and depression symptoms: The mediating role of experiential avoidance. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 22, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1862.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cunha, M., & Santos, A. M. (2011). Avaliação da Inflexibilidade Psicológica em Adolescentes: Estudo das qualidades psicométricas da versão portuguesa do Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (AFQ-Y) [Assessment of the Psychological Inflexibility among adolescents: Study of the psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the AFQ-Y]. Laboratório de Psicologia, 9, 133–146.

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005.

Espirito-Santo, H., Lopes, M., Simões, S., Cunha, M., & Lemos, L. (2014, March). Psychometrics and correlates of the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale in psychological disturbed and normal Portuguese adolescents. Poster session presented at the meeting of the 22nd European Congress of Psychiatry (EPA), Munich, Germany.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). London: SAGE Publication Lda.

Garnefski, N., Boon, S., & Kraaij, V. (2003). Relationships between cognitive strategies of adolescents and depressive symptomatology across different types of life event. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025994200559.

Giorgio, J. M., Sanflippo, J., Kleiman, E., Reilly, D., Bender, R. E., & Wagner, C. A., et al. (2010). An experiential avoidance conceptualization of depressive rumination: Three tests of the model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 1021–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.004.

Greco, L. A., Lambert, W., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Psychological inflexibility in childhood and adolescence: Development and evaluation of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth. Psychological Assessment, 20, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.93.

Guerry, J. D., & Prinstein, M. J. (2009). Longitudinal prediction of adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Examination of a cognitive vulnerability-stress model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903401195.

Hankin, B. L., & Abela, J. R. (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 2½ year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 186, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.056.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2010). Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45, 627–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2010.498290.

Hayes, L. L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2015). The Thriving Adolescent: Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Positive Psychology to Help Teens Manage Emotions, Achieve Goals, and Build Connection. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152.

Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63.

Hoff, E. R., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). Nonsuicidal self‐injury in college students: The role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 576–587. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.6.576.

Howe-Martin, L. S., Murrell, A. R., & Guarnaccia, C. A. (2012). Repetitive nonsuicidal self-injury as experiential avoidance among a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 809–829. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21868.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jutengren, G., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2011). Adolescents’ deliberate self-harm, interpersonal stress, and the moderating effects of self-regulation: A two-wave longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.11.001.

Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1301–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002.

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Glenn, C. R. (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030278.

Klonsky, E. D., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Lewis, S., & Walsh, B. (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury. Advances in psychotherapy: Evidence-based practice. Hogrefe, Cambridge, MA.

Liu, R. T., Frazier, E. A., Cataldo, A. M., Simon, V. A., Spirito, A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2014). Negative life events and non-suicidal self-injury in an adolescent inpatient sample. Archives of suicide research, 18, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.824835.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Mazza, J. J., & Reynolds, W. M. (1998). A longitudinal investigation of depression, hopelessness, social support, and major and minor life events and their relation to suicidal ideation in adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 28, 358–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1998.tb00972.x.

Marx, B. P., & Sloan, D. M. (2005). Peritraumatic dissociation and experiential avoidance as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptomatology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.004.

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual review of clinical psychology, 6, 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258.

Nock, M. K., & Mendes, W. B. (2008). Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.28.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00142.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424.

Ozdemir, O., Boysan, M., Ozdemir, P. G., & Yilmaz, E. (2015). Relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociation, quality of life, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among earthquake survivors. Psychiatry Research, 228, 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.045.

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. [Contribution to the adaptation study of the Portuguese adaptation of the Lovibond and Lovibond depression anxiety stress scales (EADS) with 21items]. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5, 229-239.

Paiva, A. (2009). Temperament and Life Events as risk factors of Depression in Adolescence. Portugal: University of Coimbra. Unpublished Master’s Thesis.

Pinquart, M. (2009). Moderating effects of dispositional resilience on associations between hassles and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.10.005.

Putnam, F. W. (1996). Child development and dissociation. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 5, 285–301.

Rallis, B. A., Deming, C. A., Glenn, J. J., & Nock, M. K. (2012). What is the role of dissociation and emptiness in the occurrence of nonsuicidal self-injury? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26, 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.26.4.287.

Seidman, E Allen, L Aber, J. L Mitchell, C Feinman, J Yoshikawa, H et al. (1995). Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 355–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506949.

Selby, E. A., Connell, L. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The pernicious blend of rumination and fearlessness in non-suicidal self-injury. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9260-z.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

Sharp, C., Kalpakci, A., Mellick, W., Venta, A., & Temple, J. R. (2015). First evidence of a prospective relation between avoidance of internal states and borderline personality disorder features in adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0574-3.

Shenk, C. E., Putnam, F. W., & Noll, J. G. (2012). Experiential avoidance and the relationship between child maltreatment and PTSD symptoms: Preliminary evidence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.012.

Smith, J. M., & Alloy, L. B. (2009). A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83.

Swannell, S., Martin, G., Page, A., Hasking, P., Hazell, P., Taylor, A., & Protani, M. (2012). Child maltreatment, subsequent non-suicidal self-injury and the mediating roles of dissociation, alexithymia and self-blame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.005.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259.

Voon, D., Hasking, P., & Martin, G. (2014). The roles of emotion regulation and ruminative thoughts in non‐suicidal self‐injury. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12030.

Vrouva, I., Fonagy, P., Fearon, P. R., & Roussow, T. (2010). The risk-taking and self-harm inventory for adolescents: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment, 22, 852–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020583.

Xavier, A., Cunha, M., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2016a). The indirect effect of early experiences on deliberate self-harm in adolescence: Mediation by negative emotional states and moderation by daily peer hassles. Journal of Child and Family Studies., 25, 1451–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0345-x.

Xavier, A., Cunha, M., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2016b). Rumination in adolescence: The distinctive impact of brooding and reflection on psychopathology. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.41.

Xavier, A., Cunha, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Paiva, C. (2013). Exploratory study of the Portuguese version of the risk-taking and self-harm inventory for adolescents. Atención Primaria, 45, Especial Congreso I (I World Congress of Children and Youth Health Behaviors/ IV National Congress on Health Education), 165.

Xavier, A., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Cunha, M. (2015, July). The role of psychological inflexibility in the relationship between life hassles and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Poster session presented at the meeting of the ACBS Annual World Conference, Berlin, Germany.

Xavier, A., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Cunha, M. (2016). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: The role of shame, self-criticism and fear of self-compassion. Child and Youth Care Forum, 45, 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9346-1.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the first author, Ana Xavier, Ph.D. Grant (grant number: SFRH/BD/77375/2011), sponsored by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the European Social Fund (POPH).

Author Contributions

A.X. executed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. M.C. assisted with the study and data analyses, discussed the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. J.P.G. designed the study, discussed the results and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xavier, A., Cunha, M. & Pinto-Gouveia, J. Daily Peer Hassles and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescence: Gender Differences in Avoidance-Focused Emotion Regulation Processes. J Child Fam Stud 27, 59–68 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0871-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0871-9