Abstract

We describe the development and validation of the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), a measure of parents’ perceptions of daily coparenting quality, to address the absence of such a daily measure in the field. A daily measure of coparenting can help us to better identify specific mechanisms of short-term change in family processes as well as examine within-person variability and processes as they are lived by participants in their everyday lives. Mothers and fathers, from 174 families with at least one child age 5 or younger, completed a 14-day diary study. Utilizing multilevel factor analysis, we identified two daily coparenting factors at both the between- and within-person level: positive and negative daily coparenting. The reliabilities of the overall D-Cop and individual positive and negative subscales were good, and we found that parents’ reports of coparenting quality fluctuated on a daily basis. Also, we established the initial validity of the D-Cop, as scores related as expected to (a) an existing and already validated measure of coparenting and to (b) couple relationship quality, depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems. Further, fluctuations in daily couple relationship feelings related to fluctuations in daily coparenting quality. The D-Cop and its subscales functioned almost identically when only utilizing 7 days of data instead of 14 days. We call for future work to study day-by-day fluctuations and dynamics of coparenting to better illuminate family processes that lead to child and family outcomes in order to improve the efficacy of family interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coparenting relationship refers to the way that partners work together in rearing their children (Feinberg 2003). The level of coparenting relationship quality has been tied to family and child outcomes, such as marital quality, child behavior problems, and child attachment security (Brown et al. 2010; Belsky and Hsieh 1998; McHale and Rasmussen 1998; Murphy et al. 2016; Schoppe et al. 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2004; Teubert and Pinquart 2010). Coparenting can influence child outcomes directly through compromising the emotional security that children feel in regards to their parents (Davies and Cummings 1994) and indirectly as the quality of coparenting spills over into the quality of parenting (Erel and Burman 1995; Margolin et al. 2001). Coparenting can also be a source of strain or support for parents, as they provide assistance to one another. Therefore, examining the development of coparenting contributes in important ways to efforts to enhance family and child well-being.

Some studies have reported moderate stability in the quality of coparenting during the early years after birth (Favez et al. 2006; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2004; Van Egeren 2004), yet the intervals between assessments are often relatively large such as 6 months or more. Although there may be moderate rank-order stability over long stretches of time, coparenting quality likely fluctuates within families over shorter periods, as parents manage the daily hassles of childrearing and other work, social, and health stressors. No studies have examined how coparenting might fluctuate on a more intensive time scale than years or months. Yet, Gable et al. (1992) suggested that “it is the day-to-day functioning of the coparenting relationship that provides a window on one important mechanism by which poor marriages both directly and indirectly affect child development” (p. 284, emphasis added) and that “information based on repeated observations of naturally occurring coparenting interactions are warranted” (p. 286).

Before noting the unique advantages of intensive data designs (such as daily diaries or daily surveys), we point out that these designs have some disadvantages—such as potentially greater burden on participants and creating the need for complex analytic approaches. Yet, daily diary designs are well-suited to answer within-person and process level questions, and research designs, data collection, and analyses should correspond with theories of processes and change in “ideal longitudinal research” (Collins 2006, p. 507). Thus, at times daily diary data are needed to answer questions more fully, whereas at other times a more traditional cross-sectional or longitudinal design may work best. In sum, daily diary designs are well-suited to approximate the processes that individuals and families experience in their daily lives (Bolger et al. 2003).

Bolger et al. (2003) summarized four important advantages offered by daily measures. First, they state that these methods are able to approximate and measure the natural, spontaneous contexts that participants experience in life. Second, using daily diary methods reduces the likelihood of retrospection, as researchers measure the process closer to the actual occurrence of the process. The potential problem with retrospective point-in-time measures is that participants may misremember or be biased in their recall (e.g., Bower 1981; Shiffman et al. 1997). Thus, Bolger et al. (2003) argue that daily diary measures are able to reduce measurement error and therefore improve validity and reliability (also see Shiffman et al. 2008).

Third, daily measures allow us to better examine and characterize lived processes and change across time (Bolger et al. 2003). For example, we may be able to find cycles in family processes across a week or examine how an individual or family adjusts after experiencing a particular event. Indeed, daily diary data are needed to investigate questions about short-term fluctuation and change. Daily diary data also allow researchers to obtain estimates of processes that we could not otherwise obtain with traditional point-in-time measures, such as variability or the instability in particular processes across brief periods of time (Ram and Gerstorf 2009).

Finally, Bolger et al. (2003) note that, with daily diary designs, researchers are able to examine causes and consequences of everyday experiences. For example, researchers can utilize a within-person approach in which individuals serve as their own controls. In other words, one can examine associations between fluctuations in variables within individuals, regardless of the overall level of these variables. In sum, daily diary designs provide unique advantages which make developing a daily measure of coparenting particularly useful for research.

Coparenting is a family process that is inherently experienced on a momentary basis by parents and children. Family systems theory (Cox and Paley 1997; Minuchin 1974; Minuchin 1985) suggests that the functioning of the coparental subsystem is linked to the experiences of the individual members of the family as well as the functioning of other subsystems within the family; family systems theory also suggests that the family system tends toward homeostasis, or a dynamic equilibrium. These tenets of family systems theory suggest that coparenting perceptions and behavior would fluctuate in response to everyday and moment-to-moment experiences as the complex family system responds to events and an ever-changing environment. Therefore, examining changes in day-to-day coparenting would allow us to understand how coparenting fluctuates, changes, and reacts on a daily basis to perturbations to the family system. These fluctuations may seem small and insignificant at one level, but may underlie overarching processes of long-term change that are not yet well understood or identified.

Studying coparenting at the daily level will better illuminate our understanding of day-to-day family processes, and information gleaned from daily diary studies of coparenting could be used to inform and improve family interventions. For example, if particular daily experiences were found to be the most closely linked to the coparenting that children receive on those days, those factors could be targeted by intervention efforts to enhance the quality of coparenting. In other words, a daily measure of coparenting can help researchers to better identify specific mechanisms of short-term change in family processes. More traditional types of cross-sectional or macro-longitudinal designs—which often focus on between-person differences and associations between variables—although useful and informative, cannot identify how families react to their daily experiences of stress, relationships, conflict, and so forth. Additionally, a daily measure of coparenting would allow us to examine the overall extent of variability or instability from day-to-day in coparenting and the effects of such variability on children, individual parents, and family relationships. Indeed, inconsistency and instability in parenting and family relationships have been linked in prior work to insecure attachment (Belsky and Pasco Fearon 2008) and to greater strain on couple well-being (Arriaga 2001). Indeed, unstable relationships are often theorized to be harmful for children and relationships (Ainsworth et al. 1978; Kelley et al. 1983). A validated measure of daily coparenting could help researchers understand this instability and other family processes as they are lived by participants in their everyday lives.

A variety of parent self-report questionnaire measures of coparenting exist. As we developed the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), we carefully examined these measures and briefly mention most of them here. The first survey measure of coparenting was created to examine the quantity and quality of communication about the child between divorced coparents (Ahrons 1981), and work examining coparenting in the divorce literature often focused on conflict, triangulation of the child, and coordination between partners across households in regards to rearing the child (e.g., Durst et al. 1985; Howe et al. 1984). In the 1990s, Belsky, McHale, and their collaborators brought the study of these coparenting processes into intact two-parent, heterosexual families (e.g., Belsky et al. 1995; McHale 1995, 1997). For example, McHale’s (1997) Coparenting Scale contains 16 items in which parents are asked to rate their own behaviors and communications within the family. This measure assesses overt behaviors (11 items) in the presence of the rest of the family and covert communications (5 items)—typically dealing with the integrity of the family or undermining the other parent in the absence of the other parent.

This work and the work of many others since then (e.g., Abidin and Brunner 1995; Floyd et al. 1998; Margolin et al. 2001; Stright and Bales 2003; Van Egeren 2003) have focused on a variety of issues related to parenting with one’s partner, such as conflict, triangulation of the child, support, endorsement and mutual respect, cooperation, sharing the burden of discipline, and satisfaction with the division of child care. All of this work was an important beginning to better understand coparenting in two-parent families. For instance, the Parenting Alliance Inventory was developed and validated by Abidin and Brunner (1995). This measure asked individual parents to rate how they feel about their parenting alliance with their partner, across 20 items. It was originally intended to operationalize Weissman and Cohen’s (1985) conceptualization of the coparenting alliance, including parental investment, the value placed on parent involvement, respect for parenting decisions, and quality of parenting communication. Abidin and Brunner (1995) found a 2-factor solution with one very broad factor and a small factor appearing to assess coparenting respect. Others have found a 3-factor solution (McBride and Rane 1998), including the emotional appraisal of partner’s parenting, shared philosophy and perceptions of parenting, and partner’s confidence in own parenting.

Other self-report measures include the Family Experiences Questionnaire, The Coparenting Questionnaire, and the Perceptions of Coparenting Partners Questionnaire. The Family Experiences Questionnaire (Frank et al. 1986; Frank et al. 1991) is a cumbersome measure with 133 items and 12 subscales. Commonly, the “General Alliance” subscale (32 items) is used (e.g., Floyd et al. 1998; Floyd and Zmich 1991; Van Egeren 2003, 2004), as this assesses similar things to the Parenting Alliance Inventory by Abidin and Brunner (1995), including perceptions of mutual respect, support, and satisfaction with shared parenting goals and values. At least one study also used the “Denigrate Spouse” subscale (10 items) in order to assess disapproval, tension, and criticism by one’s partner regarding one’s parenting practices (e.g., Floyd et al. 1998). The Coparenting Questionnaire, developed and used by Margolin et al. (2001), consists of 14 items on which parents rate the extent to which their spouse does specific actions, such as “shares the burden of discipline.” Factor analysis revealed 3 factors consisting of cooperation (support, value, and respect partner shows to you as a parent), conflict (conflict, undermining, and hostility on parenting issues), and triangulation (extent to which boundary problems and attempts to form coalitions occur). Also, Stright and Bales (2003) created a coparenting questionnaire with 14 items, the Perceptions of Coparenting Partners Questionnaire, based on the observational coparenting coding system developed by Belsky and his colleagues (Gable et al. 1992; Belsky et al. 1995; Gable et al. 1995). Its two subscales consist of seven supportive items (e.g., “My partner backs me up when I discipline my child”) and seven unsupportive items (e.g., “My partner competes with me for our child’s attention”).

Finally, Feinberg (2003) organized this work into a conceptual framework of coparenting, which consisted of four overlapping domains: childrearing agreement, coparenting support/undermining, division of labor, and joint management of family dynamics. Drawing upon prior work and Feinberg’s (2003) conceptual framework, Feinberg et al. (2012) created a comprehensive, multi-domain measure of coparenting (Coparenting Relationship Scale, CRS) which allows researchers to better assess the various dimensions of coparenting. We examined this validated measure carefully when creating items for our daily measure of coparenting.

Furthermore, in this prior literature the coparenting relationship has been conceptualized at the center of parent, child, and family interactions and well-being (e.g., Feinberg 2003). For example, coparenting is influenced by contextual characteristics such as the quality of the pre-existing couple relationship which sets the tone for the development of the coparenting relationship (Van Egeren 2004), by parent characteristics such as depression that influence how parents behave in close relationships (McDaniel and Teti 2012), and by child characteristics such as temperament that may pose challenges for the coparental dyad (Davis et al. 2009). As a central family dynamic, coparenting also acts as a mediator through which the quality of the couple relationship spills over into individual parenting quality (Margolin et al. 2001) and influences child behavior problems (Schoppe et al. 2001). Accordingly, established measures of coparenting have linked greater coparenting quality with greater couple relationship quality, fewer parent depressive symptoms, and fewer child behavior problems (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2012; McDaniel and Teti 2012; Murphy et al. 2016; Schoppe et al. 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2004), and a valid measure of coparenting should be related to these factors and also closely linked with feelings about the couple relationship.

For the current study, we developed the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), a 10-item daily diary measure of parents’ perceptions of the quality of coparenting. The purpose of the current study was to establish the initial reliability and validity of the D-Cop. We therefore utilized the measure on a sample of 174 families with a young child, examined the factor structure at the between- and within-person level, calculated the reliability of assessing within-person changes in daily coparenting (e.g., Shrout and Lane 2012), and descriptively explored the individual items and overall D-Cop scale. To establish the validity of the D-Cop, we (a) examined whether an established measure of coparenting (CRS; Feinberg et al. 2012) was related to average levels of daily coparenting, (b) examined whether perceptions of couple relationship quality, parent depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems significantly related to average levels of daily coparenting, and (c) examined whether perceptions of daily coparenting quality fluctuated within individuals across days as predicted by fluctuations in daily couple relationship feelings.

Method

Participants

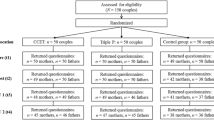

Participants included both mothers and fathers from 174 heterosexual couples with a young child who were a part of the Daily Family Life Project. Participants were currently living together in the United States and had a child age 5 or younger (M = 2.88 years, SD = 1.33; 55% female). We recruited 183 families through three primary sources: (1) a database of families across a Northeastern U.S. state who had expressed that they were willing to be contacted by researchers, (2) announcements on parenting websites and listservs, and (3) flyers in community buildings such as family doctor offices. As data collection was conducted online, families were not required to live in the state in which the study took place. Families resided in the following U.S. regions: 52% Northeast, 17% West, 16% South, and 15% Midwest.

In terms of relationship length, participants ranged from 2 to 23 years, with 92% in a relationship of 5 years or longer (M = 9.99 years, SD = 4.07). Most were Caucasian (93% for mothers, 89% for fathers), married (95%), had a Bachelor’s degree or higher (76% of mothers, 68% of fathers), and were not currently attending school (80%); 57% had more than one child. On average, mothers were 31.52 years old (SD = 4.41; range 20–42), husbands were 33.31 (SD = 5.04; range 22–52), and median yearly household income was approximately $69,000 (M = $74,000, SD = $39,000), but ranged extensively from no income to $250,000 with 21% of families reporting they were on some form of federal aid (e.g., medical assistance, food stamps, etc.). Also, 68% of mothers and 91% of fathers currently worked for pay (weekly work hours for mothers, M = 31.46, SD = 14.09; for fathers, M = 41.69, SD = 11.56).

Procedure

Participants were assigned a unique ID number which they used each day they entered responses into our online survey. This ID number was able to link partners within families and participants across days. After study enrollment and informed consent, participants first completed a baseline online survey via a secure server. This survey measured demographic characteristics, baseline coparenting quality (CRS), relationship quality, parent depressive symptoms, and perceptions of child behavior problems. Then, approximately two weeks after finishing their baseline survey (M = 17.87 days, SD = 9.38) participants completed 14 consecutive days of the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop) and other daily measures before bed. Participants completed the daily surveys about two weeks after the baseline survey to allow for comparison of time points that are relatively close to one another when examining prediction and validity, and to reduce participant burden instead of having them complete the 14 days immediately after the baseline. Families in which both partners each completed at least 10 days received a $20 gift card; participants were also entered into a drawing for one of three $100 gift cards. There were 21 participants who dropped out or who did not complete any daily surveys, yielding a sample of 345 parents (174 women and 171 men from 174 families). Of those who completed at least one day of the daily surveys (95% of full sample), participants completed an average of 11.76 days (SD = 2.94 days), with 87% completing 10 or more days, for a total of 4058 person-days of data.

Measures

Baseline coparenting quality

On the baseline survey about 2 weeks before the daily surveys began, participants completed the CRS (Feinberg et al. 2012). This measure includes 35 items that assess a variety of subdomains within coparenting, including support, undermining, agreement, endorsement of partner’s parenting, closeness, division of labor, and child exposure to conflict. Example items include “My partner and I have different ideas about how to raise our child” and “When I’m at my wits end as a parent, partner gives me extra support I need.” Participants respond to all items on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (Not true of us) to 7 (Very true of us), except for the child exposure to conflict items which are measured on a 7-point scale that ranges from 0 (Never) to 7 (Very often, several times a day). Negatively worded items were reverse scored and then items were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher quality coparenting (Cronbach’s alpha = .94 for both mothers and fathers). Please note that in order to correspond with the subscales of our daily coparenting measure that resulted from our exploratory factor analysis, we also created a positive coparenting score (i.e., support, agreement, endorsement, closeness, division of labor; 24 items; Cronbach’s alpha = .93 for mothers, .91 for fathers) and negative coparenting score (i.e., undermining and exposure to conflict; 11 items; Cronbach’s alpha = .87 for mothers, .90 for fathers). Other researchers in the field have also created overall positive and negative coparenting subscales from the CRS (e.g., Kim and Teti 2014). Feinberg et al. (2012) have demonstrated the CRS to be a reliable and valid measure of coparenting. The overall, positive, and negative CRS scores all showed good internal consistency in the current study as well.

Baseline relationship quality

Participants also completed the Quality of Marriage Index (Norton 1983) which we adapted to apply to all couples by changing “spouse” to “partner” and “marriage” to “relationship.” This measure contains 5 items (e.g., “We have a good relationship”) measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Very strongly disagree) to 7 (Very strongly agree). Then, the final item asks participants “All things considered, what degree of happiness best describes your relationship?” which participants rated on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 (Unhappy) to 10 (Perfectly happy). All items were summed to produce an overall relationship quality score for each participant (Cronbach’s alpha = .96 for mothers and .95 for fathers).

Baseline depressive symptoms

Participants rated how often they felt 20 symptoms during the past week relating to depressed mood (e.g., “I felt depressed” and “I could not get going”) on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). They responded on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Rarely or none of the time—less than 1 day) to 3 (Most or all of the time—5 to 7 days). Positively worded items were reverse scored, and then all items were summed to produce an overall score. Higher scores indicate experiencing depressive symptoms more frequently (Cronbach’s alpha = .89 for both mothers and fathers).

Baseline child behavior problems

Participants responded to 60 items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1½-5; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) which made up the internalizing (36 items) and externalizing scales (24 items). They responded to each item concerning their child now or within the past 2 months on a 3-point scale: 0 (Not true, as far as you know), 1 (Somewhat or sometimes true) and 2 (Very true or often true). Internalizing is made up of items relating to the child being emotionally reactive, anxious or depressed, experiencing somatic complaints, or being withdrawn (e.g., “whining,” “sulks a lot,” “feelings are easily hurt,” and “shows little interest in things around him/her”). Externalizing relates to attention and aggression problems (e.g., “can’t sit still, restless, or hyperactive,” “easily frustrated,” “temper tantrums or hot temper,” and “screams a lot”). Within each scale, items were summed to produce separate internalizing or externalizing ratings for each participant (Cronbach’s alpha for internalizing = .90 for mothers, .88 for fathers; alpha for externalizing = .92 for mothers, .93 for fathers).

Daily coparenting scale (D-Cop)

Although we developed the D-Cop from a careful review of the coparenting literature and Feinberg et al.’s (2012) CRS, daily diary measures must be kept brief as to not overly burden participants across days. Therefore, we limited our measure to 10 items (see Appendix Table 6 for a complete list of the items), which allowed us to obtain a sampling of possible coparenting-related feelings and behaviors that parents may encounter while working cooperatively together (or in conflict with each other) during parenting on a daily basis. However, the items provide fairly comprehensive coverage of the range of coparenting-related constructs, as we inquired concerning many of the dimensions that have been measured by prior research, such as daily experiences of the solidarity of the parenting team, cooperation, support, endorsement, disagreement, undermining, and fairness in the division of childcare tasks. Additionally, to further reduce participant burden, items were kept short and some items adapted from the CRS were shortened.

In developing items, we focused on coparenting feelings or behaviors that likely happen on a daily or almost daily basis. For example, some of the items from already validated coparenting scales could not be included on a daily measure as they ask parents to think more broadly than the daily context, such as “Parenting has given us a focus for the future” from the CRS (Feinberg et al. 2012). Furthermore, researchers have found that negative dimensions of coparenting—such as coparenting conflict or undermining—were rated as occurring quite infrequently on average (i.e., less than once or twice a week) (Feinberg et al. 2012). Thus, we included fewer negatively worded coparenting items than positively worded items (3 negative vs. 7 positive) in order to maximize our ability to examine even minor changes in coparenting on a daily basis. Additionally, to further refine the negative items we did not ask parents to rate whether they undermine each other in their parenting (as has been done in prior work, such as Feinberg et al. 2012), because of the strong negative connotation of this word. Instead, we modified negative items to be milder in tone, such as “We got upset with each other over a parenting issue.”

Apart from one item, which focused on the individual parent’s feelings about the parenting team, the other 9 items use the pronoun “we” to focus on interactions and behaviors that have occurred between parents, instead of focusing on behaviors that only one partner exhibited. This is important as many other coparenting measures (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2012) often only have the participant rate the coparenting behaviors of the partner or are inconsistent regarding whether the participant is rating the coparenting behavior of the respondent or the partner.

Participants were asked to select the response to each item that best describes the way he/she feels about how they worked together as parents today. They responded on a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). A 7-point scale allowed us to better capture the small variations in coparenting quality and discord that likely occur in low-risk, non-clinical samples on a day-to-day basis. Example items include “We cooperated in parenting” and “We upheld each other’s rules and limits to the child.” Negatively worded items were reverse coded, and then all item responses were averaged for each day to produce an overall coparenting score for each day. We also examined the average score across the 7 positive coparenting items, and the average score across the 3 negative items, as the multilevel factor analysis presented in the Results (see Table 1) indicated a positive factor and a negative factor. Although we refer to positive and negative items here, we did not know beforehand whether the 10 items would hold together into a positive and a negative subscale or break apart into three or more dimensions of coparenting. Therefore, scales were created only after the exploratory multilevel factor analysis. The scales showed good internal consistency on average (for the overall D-Cop, average Cronbach’s alpha across all days = .89 for mothers and .89 for fathers; for positive coparenting, average Cronbach’s alpha across all days = .92 for mothers and .94 for fathers; for negative coparenting, average Cronbach’s alpha across all days = .76 for mothers and .76 for fathers). Reliability estimates for assessing within-person change are reported in the results section.

Daily relationship feelings

Participants also rated how they felt each day about their relationship with their partner in terms of love, closeness, satisfaction, commitment, conflict, and ambivalence (Curran et al. 2015; Totenhagen et al. 2012). Participants responded on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not very much or just a little) to 7 (very much or a lot). Example items include “Today, how satisfied were you with your relationship with your partner?” and “Today, how much conflict did you have with your partner?” Negative items were reversed scored and then all items were averaged, with higher scores indicating a more positive assessment of the relationship on that day (average Cronbach’s alpha across all days = .86 for mothers and .87 for fathers). In our analyses, daily relationship quality was split into person-centered scores (within-person fluctuations around their mean level) and individual mean scores across days (between-person average).

Data Analyses

D-cop item and overall scale descriptive information

We first examined descriptive information concerning the D-Cop. Within-person means were calculated by averaging each individual’s scores across the 14 days, and within-person standard deviations represent the amount of variability within individuals’ scores across the 14 days. We then examined the within-person correlations, which represent the correlations among the within-person portions of the items (i.e., daily deviations above and below a participant’s overall average level across the 14 days on that item). A significant within-person correlation can be interpreted as indicating that on days when individuals deviate from their average level of an item they also tend to deviate (consistently in one or the other direction) from their average level of another item. Correlations are not reported on the raw data which would conflate the different levels of variation in our daily data (i.e., between-person with within-person), and if the variance was conflated then we could not distinguish whether the correlations were significant at the within-person level, between-person level, or both. To examine the within-person correlations, we used a multilevel structural equation model in MPlus (see Muthén 1994; Wright et al. 2015) which accounted for the nesting in our data (e.g., parents across days) while appropriately calculating significance levels for the within-person correlations. In this model, we allowed all of the items to freely covary at both the between- and within-person levels and then examined the standardized model results at the within-person level.

As final descriptive information, we ran “empty” multilevel models (i.e., models with no predictors, only the intercept) with each item or overall D-Cop score as the outcome. In these models, individuals were crossed with time (or days). These models then provided us with estimates of variability around the intercept (between-person variability in coparenting scores) and residual variability, which allowed us to calculate the intraclass correlations (ICC) for each item or overall score. The ICC provides an estimate of the proportion of variability in the item or D-Cop score that is attributable to between-person differences in level (i.e., between-person variance divided by total variance).

Assessing the factor structure of the D-Cop

Due to our data having variation at multiple levels (e.g., days, persons), we examined the factor structure of the D-Cop at both the between- and within-person level for men and then for women utilizing an exploratory multilevel factor analysis in MPLUS (Muthen and Muthen 2007; also see Mogle et al. 2015). Please note that although positively-worded items and negatively-worded items were included in the D-Cop measure, it was important to utilize an exploratory factor analysis to determine the factor structure because the 10 items cover a variety of aspects of coparenting and also because in daily diary research it is possible for measures to break apart into different between- and within-person factor structures (Mogle et al. 2015). This is due to the fact that within-person processes may function differently than between-person associations. In other words, as coparenting had never been measured on a daily basis before it was unclear whether a differential factor structure would exist at the between- and within-person levels, and we therefore made no a priori hypotheses regarding the factor structure of our measure.

Assessing the reliability of the D-Cop

To establish the reliability of our measure to capture within-person changes in daily coparenting, we calculated the within-person reliability coefficient (R c ) for intensive longitudinal data as outlined by Shrout and Lane (2012) and Mogle et al. (2015). Some have suggested that this is the most important reliability coefficient to examine in daily measures, as researchers often wish to use daily measures to examine within-person associations and fluctuations from day-to-day (Bolger and Laurenceau 2013). This index is based on generalizability theory and decomposes the variability in the daily coparenting scores into its variance components (e.g., variance across days, across participants, across items, etc.) using an ANOVA approach. A multilevel modeling approach can also be used but we found the reliability estimates to be practically identical and therefore used a simple ANOVA approach. In general, a daily measure should be able to capture within-person changes across days and between-person differences in these within-person changes (Bolger and Laurenceau 2013). The reliability coefficient is then calculated by taking the day X participant variance and dividing this by the day X participant variance plus the error variance divided by the number of items (see the equation below).

Assessing the validity of the D-Cop

To examine validity, we first examined correlations between average daily coparenting quality (overall, positive, and negative) and baseline coparenting quality (overall, positive, and negative; measured by the CRS), couple relationship quality, parent depressive symptoms, and child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. We then ran two-intercept multilevel models (MLM; as recommended for dyadic daily data by Bolger and Laurenceau 2013) predicting overall, positive, and negative daily coparenting quality by baseline coparenting quality measured by the CRS and by daily couple relationship feelings. MLM is utilized to account for the nested nature of the data (time within parents within families), and we created dummy codes for mothers and fathers so that estimates for each could be modeled simultaneously.

To examine within-person associations between daily variables in the models, Bolger and Laurenceau (2013) suggest splitting daily predictors into their between-person portions (trait) and within-person portions (state). This is done by (1) grand mean centering the daily variable, (2) calculating the mean level in that variable across days within individuals (trait), and (3) subtracting the trait variable from each individual’s daily scores on that variable (state). Thus, the trait portion measures between-person differences in that predictor; the state portion measures within-person fluctuations around their own average trait level in that variable; and the trait and state variable are uncorrelated. We included the state relationship feelings variable as a predictor in our model, as we were most interested in validating that on days when relationship quality is better coparenting quality should also be better. The MLM equations are presented here for mothers (these equations were estimated simultaneously for fathers as well):

Level 1: Coparenting ti = β 0i + β 1i Day ti + β 2i State Relationship Feelings ti + e ti

Level 2: β 0i = γ00 + γ01 Baseline Coparenting i + μ 0i

At Level 1, the equation describes the within-person relation of daily coparenting quality (Coparenting ti ) to the daily predictor state relationship feelings (β 2i ). The predicted value for coparenting quality for each individual “i” on a given occasion “t” is a function of the individual’s average coparenting quality on day 1 (intercept, β 0i ), the linear slope of day (β 1i ), daily fluctuations around the individual’s average relationship feelings (β 2i ), and residual variation in coparenting quality (e ti ).

At level 2, we entered the between-person predictor, baseline coparenting quality, and between-person random effects. The average coparenting quality score (β 0i ) is a function of the sample average coparenting quality score (γ 0i ), baseline coparenting quality (γ 01), and random variation around the sample average (μ 0i ). The linear slope in coparenting quality over days (β 1i ) is the average sample linear slope across days (γ 10). The effect of state relationship feelings (β 2i ) is a function of the sample average state relationship feelings effect (γ 20) and random variation (μ 2i ).

Results

D-Cop Item and Overall Scale Descriptive Information

We examined the within-person means, within-person standard deviations, as well as the within-person correlations across the 14 days on each of the 10 items. Means and standard deviations can be found in Table 2. The within-person estimates in Table 2 represent the average values for these statistics across all participants. The average within-person mean on the overall D-Cop was 5.92 (SD = 0.75), indicating that on average participants in our sample felt positively about their daily coparenting. The average within-person SD on the overall D-Cop score was 0.55 (SD = 0.31), which indicates that there was variability from day-to-day within individuals’ D-Cop scores and that individuals differed in the extant of daily variability they experienced.

We report within-person correlations in Table 3. Almost all within-person correlations were significant for both mothers and fathers, which indicates that within-person fluctuations across days in one item tended to also be related to similar fluctuations in other items on the D-Cop. The positive coparenting items (1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9) often related strongly to one another. The negative coparenting items (5, 6, and 10) related moderately to one another, and had the lowest correlations with the positive items. Mothers’ and fathers’ daily ratings within families were also significantly related, such that on days when mothers rated coparenting as better than her average fathers also tended to rate coparenting as better than his average (see Table 3 on the diagonal).

The ICCs ranged from .29 to .56 (see Table 2), indicating that there was a substantial amount (44–71%) of variability tied to within-person differences across days. This level of within-person variability suggests that we captured variability in parents’ feelings about daily coparenting and that it is important to examine both between- and within-person variation in daily coparenting (as there is variability at both levels).

Factor Structure of the D-Cop

The same factor structure emerged for both men and women. We selected the model with two between-person and two within-person factors, as this model produced the best fit to the data (for men, χ² (52) = 417.01, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .97; SRMR between = .01; SRMR within = .03; for women, χ² (52) = 386.15, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .97; SRMR between = .02; SRMR within = .03). We report the rotated factor loadings in Table 1. Items 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9 loaded onto one factor, reflecting positive daily coparenting (e.g., cooperation, support, upholding rules), and items 5, 6, and 10 loaded onto the other factor, reflecting negative daily coparenting (e.g., disagreement, hostility). The results indicated that this factor structure existed at both the between level (e.g., some parents were more positive in their coparenting than others) and within level (e.g., on days when mothers rated more support, they were likely to rate more cooperation). This two-factor structure also indicates that positive and negative coparenting can vary somewhat distinctly between parents as well as within an individual parent over days.

Reliability of the D-Cop

In terms of assessing within-person change, the D-Cop showed substantial reliability for daily positive coparenting (7 items; R c = .88 and .87 for women and men respectively), moderate reliability for daily negative coparenting (3 items; R c = .67 and .65), and substantial reliability for daily overall coparenting (10 items; R c = .83 and .82).

Validity of the D-Cop

Correlations between average daily coparenting quality (overall, positive, and negative), baseline coparenting quality (CRS), and other baseline study variables are presented in Table 4. Average daily coparenting scores were highly correlated with the already established measure of coparenting (CRS). In Table 4, we also presented the correlations between the established measure of coparenting (CRS) and perceptions of couple relationship quality, parent depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems. The correlations between average D-Cop scores and couple relationship quality, parent depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems were similar to those found between the already established measure of coparenting and these other factors. These correlations suggest that our daily measure functioned as expected.

In Table 5, we present the unstandardized estimates of the fixed effects from our three MLMs (predicting overall, positive, and negative daily coparenting). The expected relations emerged with higher baseline coparenting (CRS) scores related to higher average overall and positive daily coparenting and lower negative daily coparenting scores for both mothers (γ 01 = 0.67, 0.73, and −0.51, ps < .001) and fathers (γ 01 = 0.56, 0.57, and −0.54, ps < .001). Additionally, on days when couple relationship feelings were more positive, daily coparenting scores (overall, positive, and negative) were more positive for mothers (γ 20 = 0.50, 0.50, and −0.45, ps < .001) and fathers (γ 20 = 0.44, 0.46, and −0.40, ps < .001). These results lend validity to the D-Cop and its scales as a measure of daily coparenting.

Reliability and Validity of the D-Cop Utilizing Only 7 Days of Data

We used the methods and models described in the Data Analyses section to also examine the reliability and validity of the measure and its subscales using only the first 7 days of data. The D-Cop again showed good reliability for assessing within-person change in daily positive coparenting (7 items; R c = .88 and .88 for women and men respectively), daily negative coparenting (3 items; R c = .73 and .69), and daily overall coparenting (10 items; R c = .85 and .83). We also present the correlations between average daily coparenting quality (overall, positive, and negative) measured only across 7 days as opposed to 14 days, baseline coparenting quality (measured by the CRS), and other variables in Table 4. The measure and subscales again functioned similarly to the already established measure of coparenting (CRS). We then ran the two-intercept multilevel models—utilizing only 7 days of data—predicting overall, positive, and negative daily coparenting quality by baseline coparenting quality measured by the CRS and by daily couple relationship feelings. Again, the expected relations emerged with higher baseline coparenting (CRS) scores related to higher average overall and positive daily coparenting scores and lower negative daily coparenting scores for both mothers (γ 01 = 0.70, 0.78, and −0.47, ps < .001) and fathers (γ 01 = 0.56, 0.58, and −0.50, ps < .001). On days when couple relationship feelings were more positive, daily coparenting scores (overall, positive, and negative) were also more positive for mothers (γ 20 = 0.48, 0.48, and −0.46, ps < .001) and fathers (γ 20 = 0.45, 0.45, and −0.47, ps < .001). These results also lend validity to the D-Cop and its subscales as a measure of daily coparenting, even when used across only 7 days.

Discussion

To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined how coparenting might change on a more intensive time scale than years or months. Therefore, we developed the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), a 10 item measure of parents’ perceptions of daily coparenting quality. We then utilized this measure on a sample of 174 heterosexual, two-parent families who had at least one young child. The results of the current study are encouraging and lend some weight to the reliability and validity of the D-Cop as a measure of overall, positive, and negative daily coparenting quality. The results also suggest that, although an overall D-Cop score can be reliably created and used, positive and negative coparenting may function somewhat distinctly across individuals and within individuals across days. The current study was an important first step in assessing daily coparenting quality, and we suggest that future studies examining predictors and outcomes of daily coparenting quality will further elucidate the measure’s usefulness.

Utilizing the D-Cop, we confirmed that parents’ feelings about coparenting do indeed fluctuate on a daily basis and that these daily fluctuations coincide with similar daily fluctuations in their feelings regarding the quality of the couple relationship (i.e., feelings of love, commitment, conflict, etc.). In future work, the D-Cop should allow researchers to capture estimates of processes that we could not otherwise obtain with point-in-time measures, such as daily variability (or instability) in coparenting processes (Ram and Gerstorf 2009). Future work should explore (a) the various daily factors (such as parenting stressors, work and life stressors, etc.) that may influence the quality of daily coparenting that children and parents experience, (b) why some families experience greater variability (or instability) in their daily coparenting as compared with other families, and (c) what low vs. high levels of daily variability in coparenting might mean for family and child outcomes. A knowledge of the factors that are most influential for the quality of daily coparenting could be used to better inform prevention and intervention efforts with families. If we can find ways to enhance these positive daily factors, or buffer against the effects of daily negative factors, then we could further improve and stabilize the quality of coparenting that children experience on a daily basis.

The D-Cop will likely be useful in examining the reciprocal relations between the couple and coparenting relationship within the family. From a family systems perspective, both the couple relationship and the coparenting relationship are subsystems within the broader family whole separated by permeable boundaries (Minuchin 1974; Cox and Paley 1997); therefore we would expect functioning in one to be inherently tied to the other and research on coparenting has generally supported this view (e.g., McHale 1995; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2004). Indeed, the current study found that daily coparenting quality was linked to daily couple relationship quality. Future work could expand on this to examine the directionality of effects between daily coparenting and relationship quality.

The D-Cop may be particularly useful for examining the impact of particular discrete events or stressors on changes and adaptations in the coparenting subsystem, because daily measures are often useful for characterizing changes across time (e.g., Bolger et al. 2003). Examining the family system with the D-Cop in relation to particular events should help to elucidate how we can best assist families to create or maintain strong relationships as they experience stressful events. Some events that could be examined include: the transition to first-time parenthood; the birth of a sibling; the child’s attainment of developmental milestones such as walking (as it has been hypothesized that as children age parents must work together more actively to set limits on the child; McHale and Rotman 2007; Van Egeren 2003); and reintegration of a parent into the family after military deployment. The measure could also be used to assess change in coparenting before, during, and after parenting programs as families attempt to implement the programs in their everyday lives (e.g., Bamberger et al. 2014).

We caution however that this measure should not simply be used because daily diary or ecological momentary assessment research is a hot topic. In “ideal longitudinal research,” it is crucial that research designs and data collection efforts match with theories of processes and change (Collins 2006, p. 507). Thus, at times daily diary data is needed to answer our questions more fully, whereas at other times a more traditional cross-sectional or longitudinal design may work best. Often, researchers find it useful to also embed bursts of daily diaries into more traditional longitudinal designs (Sliwinski 2008).

We also examined the reliability and validity of the overall, positive, and negative D-Cop scores restricting our data to only 7 days of reports instead of 14 days. We found almost identical reliability and validity results with only 7 days of data. These results suggest that our measure successfully discriminated small variations in daily coparenting quality and therefore can also be utilized in studies that collect fewer days of participant reports. We caution however that the number of days one should assess depends on one’s theory of change and how variables are expected to relate to one another over time. This would depend on how frequently (or rarely) certain perceptions, feelings, or behaviors occur. In other words, it was possible with our current data to assess whether we could reliably measure between-person differences and within-person change in daily coparenting with varying numbers of days of data collection (e.g., 7 vs. 14); however, we cannot establish that this would always equate to obtaining equivalent information. We would argue that one should assess individuals and families for at least 7 days, especially since much of our daily experiences are structured around this social construction of weekly time—in other words, individuals and families often create rhythms and predictable patterns in their weekly routines (e.g., Almeida and McDonald 1998).

Limitations

We note several limitations of the current study. Although we had data from both parents within these families and our sample ranged greatly in their geographical residence and income, the sample was fairly homogeneous in terms of ethnicity and education (majority were White and many had at least an Associate’s degree). It may be that families of lower socioeconomic status are more at risk for spillover from various stressors within the family system into the quality of daily coparenting, as multiple risk factors may already be present. Thus, future work should examine daily coparenting in these other contexts as well. This future work would also serve to examine how sustainable daily measurement is in more diverse and lower-income samples. Moreover, as with any survey research, it is not clear how the results of these daily coparenting ratings would relate to observations of parents’ actual coparenting behaviors across days. Future research could examine relations between the D-Cop and observational measures of coparenting, child behavior problems, and so forth, as multiple methods would serve to reduce the potential for shared method variance. We find it encouraging however that our daily measure related to other important factors in similar ways to an already established and validated coparenting measure in the field (the CRS; Feinberg et al. 2012). Additionally, future research should examine whether daily coparenting relates to daily measures of parent, child, and contextual characteristics as would be expected and whether variability in daily coparenting is important over and above baseline or general levels of coparenting in predicting parent, child, and family outcomes. Finally, as the daily negative coparenting subscale showed moderate within-person reliability, it may be possible to further improve the measurement precision of this subscale by including an additional negative daily coparenting item.

In the current study, we found evidence suggesting that the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop) and its subscales are reliable and valid measures of parents’ feelings about coparenting on a daily basis. We found that parents’ feelings about their coparenting relationship fluctuated on a daily basis and that daily coparenting quality was linked positively to daily relationship quality. As coparenting has been linked to long-term couple outcomes such as marital quality and child outcomes such as internalizing/externalizing behaviors, attachment security, and academic success (e.g., Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2004; Teubert and Pinquart 2010), it is important to also examine coparenting at the daily level; this daily examination can help us to better identify and optimize specific mechanisms of short-term change in family processes as well as examine within-person variability and processes as they are lived by participants in their everyday lives. Future work using this measure to study coparenting at the daily level will illuminate our understanding of the day-to-day family processes that lead to the best outcomes for children and families.

Change history

02 June 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Abidin, R. R., & Brunner, J. F. (1995). Development of a parenting alliance inventory. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24, 31–40.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Ahrons, C. A. (1981). The continuing coparental relationship between divorced spouses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 51, 415–428.

Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Pattems of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Almeida, D. M. & McDonald, D. (1998). Weekly rhythms between parents’ work stress, home stress, and parent-adolescent tension. In R. Larson & A. C. Crouter (Eds), Temporal rhythms in adolescence: Clocks, calendars, and the coordination of daily life (pp. 53–67). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arriaga, X. B. (2001). The ups and downs of dating: Fluctuations in satisfaction in newly formed romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 754–765.

Bamberger, K. T., Coatsworth, J. D. & Ram, N. (2014, May). Change in family systems: Tracking family functioning through intensive daily data collected during interventions. Poster presented at the Society for Prevention Research 22nd Annual Conference, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268102244_Change_in_Family_Systems_Tracking_Family_Functioning_through_Intensive_Daily_Data_Collected_during_Interventions. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1377.3925.

Belsky, J., Crnic, K., & Gable, S. (1995). The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development, 66, 629–642.

Belsky, J., & Hsieh, K. (1998). Patterns of marital change during the early childhood years: Parent personality, coparenting, and division-of-labor correlates. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 511–528.

Belsky, J., & Pasco Fearon, R. M. (2008). Precursors of attachment security. In J. Cassidy, & P. R. Shaver (Eds). Handbook of attachment (2nd ed., pp. 295–316). New York, NY: Guilford.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616.

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148.

Brown, G. L., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Neff, C. (2010). Observed and reported coparenting as predictors of infant–mother and infant–father attachment security. Early Child Development and Care, 180, 121–137.

Collins, L. M. (2006). Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 505–528.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267.

Curran, M. A., McDaniel, B. T., Pollitt, A. M., & Totenhagen, C. J. (2015). Gender, emotion work, and relationship quality: A daily diary study. Sex Roles, 73, 157–173. doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0495-8.

Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411.

Davis, E. F., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Brown, G. L. (2009). The role of infant temperament in stability and change in coparenting across the first year of life. Parenting: Science and Practice, 9, 143–159.

Durst, P. L., Wedemeyer, N. V., & Zurcher, L. A. (1985). Parenting partnerships after divorce: Implications for practice. Social Work, 30, 423–428.

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108.

Favez, N., Frascarolo, F., & Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. (2006). Family alliance stability and change from pregnancy to toddlerhood and marital correlates. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 65, 213–220.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131.

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A Multi-Domain Self-Report Measure of Coparenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 1–21.

Floyd, F. J., Gilliom, L. A., & Costigan, C. L. (1998). Marriage and the parenting alliance: Longitudinal prediction of change in parenting perceptions and behaviors. Child Development, 69, 1461–1479.

Floyd, F. J., & Zmich, D. E. (1991). Marriage and the parenting partnership: Perceptions and interactions of parents with mentally retarded and typically developing children. Child Development, 62, 1434–1448.

Frank, S. J., Jacobson, S. & Hole, C. B. (1986). The parenting alliance: Bridging the relationship between marriage and parenting. Unpublished manuscript, Michigan State University.

Frank, S. J., Olmsted, C. L., Wagner, A. E., Laub, C. C., Freeark, K., Breitzer, G. M., & Peters, J. M. (1991). Child illness, the parenting alliance and parenting stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 16, 361–371.

Gable, S., Belsky, J., & Crnic, K. (1992). Marriage, parenting, and child development: Progress and prospects. Journal of Family Psychology, 5, 276.

Gable, S., Belsky, J., & Crnic, K. (1995). Coparenting during the child’s 2nd year: A descriptive account. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 609–616.

Howe, G. W., Bishop, G., Armstrong, B., & Fein, E. (1984). Parental decision-making styles during and after divorce. Conciliation Courts Review, 22, 63–70.

Kelley, H. H., Berschied, E., Christensen, A., Harvey, J. H., Huston, T. L., Levinger, G., & Peterson, D. R. (1983). Close relationships. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Kim, B., & Teti, D. M. (2014). Maternal emotional availability during infant bedtime: An ecological framework. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 1–11. doi:10.1037/a0035157.

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 3–21.

McBride, B. A. & Rane, T. R. (1998). Parenting alliance as a predictor of father involvement: An exploratory study. Family Relations, 47, 229–236.

McDaniel, B. T., & Teti, D. M. (2012). Coparenting during the first three months after birth: The role of infant sleep quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 886–895. doi:10.1037/a0030707.

McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31, 985–996.

McHale, J. P. (1997). Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process, 36, 183–201.

McHale, J. P., & Rasmussen, J. L. (1998). Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 39–59.

McHale, J. P., & Rotman, T. (2007). Is seeing believing? Expectant parents’ outlooks on coparenting and later coparenting solidarity. Infant Behavior and Development, 30, 63–81.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56, 289–302.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mogle, J., Almeida, D. M., & Stawski, R. S. (2015). Psychometric properties of micro-longitudinal assessments: Between- and within-person reliability, factor structure and discriminate validity of cognitive interference. In M. Diehl, K. Hooker, & M. Sliwinski (Eds), Handbook of intraindividual variability across the life span. New York, NY: Routledge.

Murphy, S. E., Jacobvitz, D. B., & Hazen, N. L. (2016). What’s so bad about competitive coparenting? Family-level predictors of children’s externalizing symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1684–1690.

Muthén, B. O. (1994). Multilevel covariance structure analysis. Sociological methods & research, 22(3), 376–398.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2007). MPlus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and Family, 45, 141–151.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Ram, N., & Gerstorf, D. (2009). Time-structured and net intraindividual variability: Tools for examining the development of dynamic characteristics and processes. Psychology and Aging, 24(4), 778–791.

Schoppe, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Frosch, C. A. (2001). Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers’ externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 526–545.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Frosch, C. A., & McHale, J. L. (2004). Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 194–207.

Shiffman, S., Hufford, M., Hickcox, M., Paty, J. A., Gnys, M., & Kassel, J. D. (1997). Remember that? A comparison of real-time versus retrospective recall of smoking lapses. Journal of Consult. & Clinical Psych., 65(2), 292–300.

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32.

Shrout, P. E., & Lane, S. P. (2012). Psychometrics. In M. R. Mehl, & T. S. Conner (Eds), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 302–320). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sliwinski, M. J. (2008). Measurement-Burst Designs for Social Health Research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 245–261.

Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52(3), 232–240.

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4), 286–307.

Totenhagen, C. J., Serido, J., Curran, M. A., & Butler, E. A. (2012). Daily hassles and uplifts: A diary study on understanding relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 719–728. doi:10.1037/a0029628.

Van Egeren, L. A. (2003). Prebirth predictors of coparenting experiences in early infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24, 278–295.

Van Egeren, L. A. (2004). The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25, 453–477. doi:10.1002/imhj.20019.

Weissman, S. H., & Cohen, R. S. (1985). The parenting alliance and adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 24–45.

Wright, A. G., Beltz, A. M., Gates, K. M., Molenaar, P. C., & Simms, L. J. (2015). Examining the dynamic structure of daily internalizing and externalizing behavior at multiple levels of analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–20.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families who participated in this research, as well as the research assistants who made all of this recruitment and data collection possible. We would also like to acknowledge the College of Health and Human Development, the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, as well as the Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center at The Pennsylvania State University which awarded research funds to the first author to complete this research. The first author's time on this manuscript was also partially funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Award Number T32DA017629) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Award Number F31HD084118).

Funding

The first author’s time on this manuscript was partially funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Award Number T32DA017629) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Award Number F31HD084118).

Author Contributions

B.M.: conceptualized the research idea, designed the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), designed the Daily Family Life Project and executed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript. D.T.: assisted in the refining of the research idea, provided feedback on results, and assisted with the writing and editing of the manuscript. M.F.: assisted in the refining of the research idea, provided feedback on the initial design of the Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop), and assisted in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake. The sixth row in Table 6 was missed by the typesetter. The original article was corrected. The corrected table is given below.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0794-5.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 6

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDaniel, B.T., Teti, D.M. & Feinberg, M.E. Assessing Coparenting Relationships in Daily Life: The Daily Coparenting Scale (D-Cop). J Child Fam Stud 26, 2396–2411 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0762-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0762-0