Abstract

Previous research has found significant associations between family routines (e.g., time shared and family meals), parenting characteristics, and later adolescent health behaviors. In general, greater family interactions, parental monitoring, and more optimal parenting style have been associated with less alcohol use during adolescence. We expanded upon this work by examining effects of family and parenting characteristics on alcohol use and health behaviors during young adulthood. We also followed tenets of the Contextual Model of Parenting by examining the moderating effects of parenting style on the associations between parent/family practices and outcomes. Data came from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997. A total of 5419 youth were surveyed at 12–14 years of age, and then annually for the next 14 years; 4565 were surveyed at a 10 year follow-up and 4539 were examined at the 14 year follow-up (84% retention). Multivariate models, controlling for sex and race/ethnicity, indicated that, in general, family routines and parental knowledge in early adolescence were associated with healthier behaviors at both the 10-year and 14-follow-ups. Results also showed that the protective effects of parental knowledge and family routines were strongest in families characterized by and authoritative parenting style.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research has shown that parenting characteristics during early adolescence can have profound impacts on development later in adolescence (Barnes et al. 2000; Pettit et al. 1999; Stattin and Kerr 2000). Two aspects of parenting that have received significant attention are the extent to which parents are aware of their child’s activities, termed parental knowledge (Kerr and Stattin 2000), and the establishment of family routines, or activities that occur with the family unit on a regular, frequently patterned basis like meals spent together or housework/chores performed.

Significant research has shown that higher levels of perceived parental knowledge are associated with less use of alcohol and other substances during adolescence and less delinquent activity (Barnes et al. 2000; Fletcher et al. 2004; Pettit et al. 1999; Stattin and Kerr 2000). A smaller body of research has indicated a relationship between parental knowledge and adolescent dietary intake (Alia et al. 2013; Mellin et al. 2002), as well.

Family routines, or time spent doing an activity on a regular basis as a family, have also been frequently investigated for many decades (Fiese et al. 2002; Skeer and Ballard 2013), with results, in general, supporting their utility in enhancing youth well-being. For example, more frequent family meals during adolescence have been associated with lower rates of depression, substance use, and delinquency (Musick and Meier 2012). The literature, however, has not been unanimous in observing significant protective effects of family routines. More frequent routines have been inconsistently found to be related to youth outcomes (Eisenberg et al. 2008; Hoffman and Warnick 2013; Miller et al. 2012; Sen 2010; White and Halliwell 2011).

A weakness of much of the work on these parenting practices is that only concurrent or short-term outcomes have been explored. Much of the work linking family routines and parental knowledge with youth behavior also fail to take into account the potential impact the family context might play in determining the impact of efforts made by parents. The Contextual Model of Parenting Style (Darling and Steinberg 1993) states parenting practices, like efforts to establish positive family routines and to know about the activities on one’s child directly, have a direct and proximal impact on adolescent outcomes. These practices serve as the mechanisms by which parents seek to socialize their children their values and those of society across a variety of domains. In contrast, no direct effect of parenting style on outcomes is implied in this model, as the style with which parents interact with their children is independent of the substance of the interaction/domain. Instead, parenting style, as defined by qualities of warmth and demandingness, serves primarily as a moderating influence, such that the impacts of specific parenting practices on socialization goals (e.g., achievement, healthy activities) are dependent, to some extent, upon the primary style employed by parents during adolescence.

The current study expands upon previous literature by examining long-term effects of family and parenting characteristics during early adolescence on substance use and other health behaviors beyond adolescence. We first hypothesized that more frequent family routines will be associated with a consistent pattern of positive health behaviors during emerging and young adulthood (Hypothesis 1). The current study also examined the extent to which the effect of family routines on later outcomes was dependent on perception of parental knowledge during adolescence. We expected to observe main effects of parental knowledge on outcomes (Hypothesis 2) and significant moderation, such that the impact of family routines would be most pronounced in families where parents are well informed about the activities of their children during adolescence (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we followed tenets of the Contextual Model of Parenting Style (Darling and Steinberg 1993) by examining the moderating effects of parenting style on the associations between family and parenting characteristics and later health outcomes. We hypothesized that the impact of both family routines and parental knowledge would be most pronounced in families characterized by an authoritative parenting style (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants

Data for this study come from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth-1997 (NLSY97). The NLSY97 is prospective, national study of youth in the US between 12-year and 16 year-old at baseline. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study, and have been surveyed annually since 1997 (see www.bls.gov/nls/handbook/2005/nlshc2.pdf). The current study utilizes data from those participants who were 12–14-years old in 1997 (baseline). Data from waves 1, 10 (ages 22–24; emerging adulthood), and 14 (ages 26–28; young adulthood) were examined. The baseline sample consisted of 5419 participants (52% men). The sample was highly diverse with regard to race and ethnicity, with 2823 non-Hispanic White participants (52%), 1388 non-Hispanic Black (26%) participants, 1157 Hispanic (21%) participants, and 51 non-Hispanic, mixed race (1%) participants. The mean age at baseline was 13.33 years (SD = 0.95 years).

Retention of participants was high in this sample. A total of 4565 participants (84%) were surveyed at the 10 year follow-up (Wave 10; 2007), and 4539 (84%) were surveyed at the 14 year follow-up (Wave 14; 2011). Participant age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Coded Non-Hispanic White vs. Other) were included as covariates.

Measures

Baseline measures

Family routines

Family routines were measured at baseline using the Index of Family Routines, derived from the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen et al. 1983). This index consisted of four youth-reported items measured on an 8-point scale from 0 = No days per week to 7 = All 7 days per week (Potential Range = 0–28). The specific items were: “In a typical week, how many days from 0 to 7—(a) do you eat dinner with your family?, (b) does housework get done when it is supposed to, for example cleaning up after dinner, doing dishes, or taking out the trash?, (c) do you do something fun as a family such as play a game, go to a sporting event, go swimming and so forth?, and (d) do you do something religious as a family such as go to church, pray or read the scriptures together?”. Given that this measure represents an index, internal consistency metrics are not calculated because the individual indicators represent items that are not necessarily closely correlated (though each item is significantly, positively related) but likely have a cumulative effect when used in predictive modeling (Bollen and Lennox 1991). To further support the use of these items as an index, we examined associations between each routine and outcomes in preliminary bivariate analysis. Previous work using data from the NLSY 97 has made use of this measure (e.g., Hair et al. 2009; Hogan et al. 2007; Manlove et al. 2008).

Perceived parental knowledge

Youth perceptions of parental knowledge of their activities at baseline were indexed by four items responded to for each parent (eight items total; Maccoby and Mnookin 1992). Items were measured on a five-point scale from 0 = knows nothing to 4 = knows everything, and asked for youth perceptions of how much their mothers/fathers know about who (1) their best friends are, (2) their best friends’ parents are, (3) they are with when not at home, and (4) their teachers are and what they are doing at school (Maternal α’s > 0.71; Paternal α’s > 0.80). Preliminary analyses showed the paternal scale to have limited predictive utility beyond the maternal scale, paternal and maternal scales were closely associated (r = 0.65), and there was substantial missing data on the paternal scale (27% of the sample). As such, in order to avoid unnecessary multicolinearity, we utilized only maternal knowledge in the current study.

Perceived parenting style

Two youth self-report items were used to create baseline perceived parenting styles along the Baumrind/Macobby and Martin framework (Baumrind 1971; Maccoby and Martin 1983). We focused solely on maternal style for the same reasons discussed regarding parental knowledge. The first item asked, “When you think about how s/he acts towards you, in general, would you say that s/he is very supportive, somewhat supportive, or not very supportive?”. Responses of “somewhat supportive” and “not very supportive” represented non-responsive parenting, and responses of “very supportive” represented responsive parenting. The second item asked, “In general, would you say that s/he is permissive or strict about making sure you did what you were supposed to do?”. The four parenting styles were defined as: Authoritative (responsive and strict; 42.7% of respondents), Authoritarian (non-responsive and strict; 14.2%), Permissive (responsive and permissive; 31.6%), and Uninvolved (non-responsive and permissive; 11.5%). This measure has been used previously in work utilizing the NLSY 97 (e.g., Bolkan et al. 2010; Bronte-Tinkew et al. 2006).

Follow-up measures

Alcohol use

Alcohol use was measured in several ways. Participants reported on (a) whether or not they had a drink of an alcoholic beverage since the last annual measurement (labeled past year alcohol use), (b) on how many days in the last 30 days they had one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage (labeled drinking frequency), (c) on the days they drank alcohol in the past 30 days, about how many drinks did they usually have (labeled drinking quantity), and (d) on how many days did they have five or more drinks on the same occasion during the past 30 days (labeled binge drinking).

Cigarette use

To measure cigarette use, participants reported on (a) whether or not they had smoked a cigarette since the last annual measurement (labeled past year cigarette use), (b) on how many days in the last 30 days they had smoked a cigarette (labeled cigarette frequency), and (c) on the days they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days, about how many cigarettes did they usually smoke (labeled cigarette quantity).

Marijuana use

To capture marijuana use, participants were asked (a) whether or not they had used marijuana since the last annual measurement (labeled past year marijuana use) and (b) on how many days they used marijuana in the last 30 days (labeled marijuana frequency).

Fruit and vegetable intake

Participants were asked to indicate how often in a typical week (a) they ate vegetables other than French fries or potato chips (labeled vegetable intake) and (b) they ate fruit, excluding fruit juice (labeled fruit intake). These items were indexed on a seven-point scale from 1 = do not typically eat to 7 = four or more times per day.

Sleep hours

Participants were asked to report how many hours of sleep they usually got per night from 1 h to 10+ h.

Data Analyses

A series of structural equation models were performed predicting past year alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use, fruit and vegetable intake, and sleep hours using family routines, parental knowledge, the interaction term between routines and monitoring, and covariates. Models were performed separately for the 10-year and 14-year follow-ups. A second set of analyses were performed for the subset of youth who reported use of substances in the past year. These models examined the number of days used in the past month and the quantity of use per day (for alcohol and cigarettes). We then performed a set of multiple groups structural equation models to examine differences in associations between predictors and outcomes by parenting style.

All models were performed in Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) using full information maximum likelihood estimators robust to non-normality and missing data over time. Model fit was evaluated using the model χ², Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler 1990), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger and Lind 1980). Changes in χ² and CFI were used to evaluate the fit of the multiple groups models when estimated freely and with constrained paths. Associations between variables are described using standardized beta coefficients using a more stringent alpha level than standard (p < 0.01). This level was set to account for the multiple associations examined in the current study and the potential to identify exceedingly small associations with a more liberal alpha given the large sample utilized. The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College at Brockport.

Results

Descriptive statistics for covariates, predictors, and outcomes are presented in Table 1. Before performing structural equation models, attrition analysis and bivariate correlations were then examined (see Table 2). Comparisons were made between those retained at follow-up and those lost to attrition. Results indicated that there we no differences across groups in age and baseline substance use (p’s > 0.01). A greater percentage of males were lost to attrition at the 10-year (19 vs. 15%) and 14-year follow-ups (19 vs. 16%, p’s < 0.01), and more non-Hispanic White youth were lost to attrition at the 14-year follow-up (20 vs. 15%, p < 0.001). As such, these demographic characteristics were included in each of the predictive models. With regard to associations between primary predictors and outcomes, greater family routines were associated with less tobacco and marijuana use and better dietary intake at each follow-up. Greater knowledge was associated with decreased likelihoods of tobacco and marijuana use and better dietary intake at each follow-up, as well as greater sleep hours at the 14-year follow-up. In contrast, greater monitoring is also associated with a greater likelihood of alcohol use at each time point. The magnitudes of each of these associations were small.

Among individuals who used alcohol, greater family routines were associated with less quantity of alcohol consumed at each follow-up and less frequency at the 10-year follow-up (see Table 3). The only significant association between parental knowledge and alcohol use behaviors among current users was for heavy episodic drinking at the 14-year follow-up, with greater knowledge associated with less heavy episodic drinking. Among cigarette users, greater family routines were associated with less frequent use and lower quantities are each follow-up, while greater parental knowledge was associated with less frequent use at the 14-year follow-up.

Given that the primary predictor of the proposed models was an index variable, we also wanted to first determine the consistency of associations both within family routines and between specific routines and outcomes. Results indicated that routines were all positively associated with each, with correlations between 0.15 and 0.37 (p’s < 0.001). With regard to bivariate associations between specific routines and health behavior outcomes at each follow-up, the vast majority of correlations with each outcome were in the same direction and of similar magnitude across each of the four family routines. The only discrepancies observed were with respect to the alcohol-use behaviors, such that greater days with family fun and religious activities tended to be associated with less use while greater days with family meals tended to be associated with more use. Given the associations within routines, the general (though not uniform) pattern of consistent associations with outcomes, and previous use in the published literature (e.g., Hair et al. 2009; Hogan et al. 2007), we felt comfortable utilizing the index as a primary predictor in our structural equation models.

Predicting Health Behaviors at the 10-Year Follow-Up

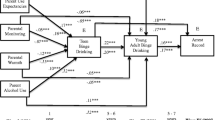

We then sought to predict outcomes using the covariates and primary predictors in a manifest structural equation model (see Fig. 1). Given that participant age was infrequently related to outcomes at the bivariate level, it was not included as a covariate in predictive models due to an interest in model parsimony. The resulting model for the 10-year follow-up provided excellent fit to the data, χ² (6) = 68.60, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04 (see Table 4), with all misfit extending from un-modeled correlations among predictors (i.e., the beta matrix was saturated). Hypothesis 1 was supported, such that more frequent family routines were associated with a decreased likelihood of marijuana use, greater vegetable intake, and greater fruit intake. Greater parental knowledge was again associated with a decreased likelihood of cigarette use, providing some support for Hypothesis 2, and an increased likelihood of alcohol use, which stands in contrast to our hypothesis. Hypothesis 3 was not supported, as the interaction between family routines and parental knowledge was not predictive of any outcome. None of the predictors or covariates were predictive of sleep hours.

Among current alcohol users, no significant associations were observed between alcohol-use behaviors and parental knowledge or family routines. Among current cigarette users, Hypothesis 2 was supported such that greater parental knowledge was predictive of less frequent smoking and lower quantities of use. No significant associations were observed between marijuana frequency and parental knowledge or family routines.

Predicting Health Behaviors at the 14-Year Follow-Up

The base model for the 14-year follow-up provided fit as observed at the 10-year follow-up given the saturated beta matrix, χ² (6) = 68.60, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04 (see Table 4). Once again in support of Hypothesis 1, greater family routines was associated with a decreased likelihood of marijuana use, greater vegetable intake, and greater fruit intake. Greater parental knowledge was associated with an increased likelihood of alcohol use and increased vegetable intake, proving inconsistent support Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 regarding the moderation of family routines by parental knowledge was again not supported as the interaction term was not predictive of any outcome. The only significant predictor of sleep hours was race/ethnicity.

Among current alcohol users, Hypothesis 1 received further support as greater family routines was associated with less heavy episodic drinking (β = −0.07, p = 0.01). Among current cigarette users, greater parental knowledge was predictive of less frequent smoking (β = −0.10, p < 0.001) and lower quantities of use (β = −0.12, p < 0.001), thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. No significant associations were observed between marijuana frequency and parental knowledge or family routines.

Moderation by Parenting Style

We then performed the same series of structural equation models in a multiple groups framework with perceived parenting style as the grouping variable. In order to facilitate model convergence, the interaction between family routines and parental knowledge was eliminated from these models.

10-Year follow-up

The freely estimated base model predicting health behaviors at 10-year follow-up provided excellent fit to the data, χ² (16) = 74.46, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.05. There were considerable differences in the pattern of significant findings across style with regard to the primary predictors of interest. Among authoritative parents, greater family routines was associated with a decreased likelihood of marijuana use (β = −0.11, p = 0.007), greater fruit intake (β = 0.07, p = 0.01), and greater sleep hours (β = 0.06, p = 0.01), while greater parental knowledge was associated with a decreased likelihood of cigarette use (β = −0.10, p = 0.002) but an increased likelihood of alcohol use (β = 0.11, p = 0.001). Greater routines among uninvolved parents were also predictive of greater vegetable intake (β = 0.16, p = 0.005).

We then constrained pathways from predictors to outcomes with differential significance to be equivalent across parenting style. Results indicated that, contrary to Hypothesis 4, the associations between parental knowledge and outcomes were not statistically different across parenting style, Δχ² (6) = 12.59, p = 0.18, ΔCFI = 0.00. The differences observed in the associations between family routines and outcomes across parenting style were significant, Δχ² (9) = 19.52, p = 0.02, ΔCFI = 0.01, providing a degree of support Hypothesis 4.

Among current alcohol users, greater parental knowledge was only associated with less frequent drinking (β = −0.11, p = 0.005) among authoritative parents. The differences observed in this association across parenting style was statistically significant, Δχ² (3) = 8.31, p = 0.04, ΔCFI = 0.01, providing further support for Hypothesis 4. No other predictions of knowledge or family routines on outcomes were significant.

14-Year follow-up

As would be expected given the structure of the models, the freely estimated base model predicting health behaviors at 14-year follow-up provided very similar fit as the 10-year model, χ² (16) = 74.44, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05. Again, there were considerable differences in the pattern of significant findings across style with regard to the primary predictors of interest. Among authoritative parents, greater family routines was associated with a decreased likelihood of alcohol (β = –0.08, p = 0.01) or marijuana use (β = –0.13, p = 0.002), and greater fruit intake (β = 0.07, p = 0.01), while greater parental knowledge was associated with a decreased likelihood of cigarette use (β = –0.13, p < 0.001) and greater vegetable intake (β = 0.08, p = 0.004). The only other significant predictions were (1) between family routines and fruit intake among uninvolved (β = 0.17, p = 0.002) and permissive (β = 0.08, p = 0.01) parents and (2) between parental knowledge and fruit intake among authoritarian parents (β = 0.15, p = 0.01). Results of constrained models indicated that the associations between parental knowledge and outcomes were statistically different across parenting style, Δχ² (9) = 23.34, p = 0.005, ΔCFI = 0.01, providing support for Hypothesis 4. In contrast, the differences observed in the associations between family routines and outcomes across parenting style were not statistically significant, Δχ² (9) = 13.44, p = 0.14, ΔCFI = 0.00, thereby failing to support our fourth hypothesis.

Among current alcohol users, when separated by parenting style, there were no significant predictions of outcomes by family routines or parental knowledge. Among current cigarette users, greater parental knowledge was associated with lower frequency of cigarette use among authoritative parents (β = –0.12, p = 0.01). Differences in this association were not statistically significant across parenting styles, Δχ² (3) = 5.45, p = 0.14, ΔCFI = 0.00. Finally, when examined separately by parenting style, there were no significant associations between primary predictors and frequency of marijuana use.

Discussion

This study sought to utilize a large, nationally sampled dataset to examine the long-term impact of family routines and parental knowledge during early adolescence on health-related behaviors during emerging and young adulthood. Results show that, despite the extended length of time between initial survey and follow-up time points, when accounting for known influential covariates, our main effects hypotheses were largely supported given there was a relatively consistent pattern of associations linking greater family routines and greater parental knowledge with more optimal health behaviors. These findings support an ever-growing body of research demonstrating parental influences beyond childhood and adolescence (Abar et al. 2014; Barnes et al. 2000; Wood et al. 2004). The current study also adds to the literature by demonstrating effects of routines and knowledge on a diverse set of outcomes, each with a unique etiology and representing both positive and negative health behaviors. The fact that these patterns of associations were observed across both the 10-year and 14-year spans adds to their validity. Findings linking greater family routines with more optimal development correspond to previous research linking family meals with less substance use and delinquency in adolescence (Musick and Meier 2012). There was, however, an unexpected association observed between parental knowledge and past year alcohol use, with greater knowledge associated with greater likelihood of use during young adulthood. Given that, among current alcohol users, greater parental knowledge was not associated with the quantity and frequency of alcohol use, it is possible that greater knowledge may lead to moderate, low risk use of alcohol in adulthood. Though this finding would be in line with the current associations linking family/parenting practices with health behaviors, additional research is needed to validate this supposition.

The multiple groups analyses performed testing our forth hypothesis provided a degree of support for the Contextual Model of Parenting Style (Darling and Steinberg 1993). By demonstrating that several of the observed protective effects of routines and knowledge were most pronounced in authoritative families, we showed how the impact of a specific practice or set of practices, like establishing routines for daily family life, should be contextualized within the overarching family setting. However, though we found some evidence for moderation by parenting style, this moderation was not uniform, as several protective effects of family routines and parental knowledge on outcomes were observed among families characterized by non-authoritative mothers. These findings are particularly encouraging for public health scientists, as they imply universal intervention programs to encourage family interaction and parent-child conversations (Kumpfer and Alvarado 2003; Turrisi et al. 2013) can be beneficial across family contexts. This is also important from an applied perspective since family routines and parental knowledge represent parental practices (Darling and Steinberg 1993) which can be effectively modified (Dishion et al. 2003; Turrisi et al. 2013), rather than more diffuse and general contexts like parenting style or parent-child relationship quality which are established over a long-period of time and are not as amenable to brief, or even sustained, intervention.

There were several limitations to the current study. First, several of the measures (specifically family routines and parenting style) collected during the early waves of the NLSY 97, while representing their construct, were lacking in granularity and sophistication. The parenting style measure, in particular, was designed for the NLSY 97 to be a very brief index appropriate for large, national data collection with the understanding that a more in-depth measure would likely provide added predictive utility (Child Trends, Inc. 1999). Future research would likely benefit from operationalizing routines using additional indicators of family interactions (e.g., family visits, shared errands, etc.) and using more established indices of perceived parenting style (Buri 1991). Second, many of the associations observed were small in magnitude. Though effect sizes were small, the presence of relatively consistent protective associations across 10 and 14-years of significant development and across multiple domains of health behaviors highlight the relevance of the findings. They also highlight the need to identify mediators of the associations observed, such that parenting practices in early adolescence likely impact youth factors during later adolescence that cascade into health behaviors as adults. Third, like the vast majority of work on parenting influences, the measurement of family routines and parental knowledge in the NLSY 97 study does not take into account valence of the interactions (with a salient exception being White and Halliwell 2010). For example, it is likely that family routines that are viewed by the teen as highly aversive would have a very different impact than family routines that are perceived as enjoyable or beneficial. Similarly, a great deal of parental knowledge about youth antisocial behaviors will result in different interactions and outcomes than a great deal of knowledge about more pro-social activities. Fourth, while the current study examined a relatively broad set of health behaviors in young adulthood as outcomes, this set is not comprehensive, such that follow-up work should examine additional behaviors like exercise/activity level, preventive health care, and/or self-harming behaviors. Fifth, the current study accounted for baseline differences in outcomes between males and females by including gender as a covariate in the predictive models. Future research might benefit from incorporating gender as a grouping variable to explore potential differential associations between health behaviors and family/parenting activities. Finally, an exhaustive set of potential relevant covariates (e.g., parental modeling of substance use and health behaviors, peer normative beliefs about heath behaviors, etc.) was not included in the models presented, such that alternative explanations for associations remain. Subsequent replication research should seek to observe findings similar to those in the current study while including additional covariates.

References

Abar, C. C., Jackson, K. M., & Wood, M. D. (2014). Reciprocal relations between parental monitoring and adolescent substance use and delinquency: The moderating role of parent-teen relationship quality. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2176–2187.

Alia, K. A., Wilson, D. K., George, S. M. S., Schneider, E., & Kitzman-Ulrich, H. (2013). Effects of parenting style and parent-related weight and diet on adolescent weight status. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 321–329.

Barnes, G. M., Reifman, A. S., Farrell, M. P., & Dintcheff, B. A. (2000). The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 175–186.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bolkan, C., Sano, Y., De Costa, J., Acock, A. C., & Day, R. D. (2010). Early adolescents’ perceptions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and problem behavior. Marriage & Family Review, 46, 563–579.

Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 305–314.

Bronte-Tinkew, J., Moore, K. A., & Carrano, J. (2006). The father-child relationship, parenting styles, and adolescent risk behaviors in intact families. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 850–881.

Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 110–119.

Child Trends, Inc. (1999). NLSY97 codebook supplement main file round 1, appendix 9: Family process and adolescent outcome measures. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496.

Dishion, T. J., Nelson, S. E., & Kavanagh, K. (2003). The family check-up with high risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavioral Therapy, 34, 553–571.

Eisenberg, M. E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Fulkerson, J. A., & Story, M. (2008). Family meals and substance use: Is there a long-term protective association? Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 151–156.

Fiese, B. H., Tomcho, T. J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., & Baker, T. (2002). A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 381–390.

Fletcher, A. C., Steinberg, L., & Williams-Wheeler, M. (2004). Parental influences on adolescent problem behavior: Revisiting Stattin and Kerr. Child Development, 75, 781–796.

Hair, E. C., Park, M. J., Ling, T. J., & Moore, K. A. (2009). Risky behaviors in late adolescence: Co-occurrence, predictors, and consequences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 253–261.

Hoffman, J. P., & Warnick, E. (2013). Do family dinners reduce the risk for early adolescent substance use? A propensity score analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54, 335–352.

Hogan, D. P., Shandra, C. L., & Msall, M. E. (2007). Family developmental risk factors among adolescents with disabilities and children of parents with disabilities. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 1001–1019.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36, 366–380.

Kumpfer, K. L., & Alvarado, R. (2003). Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist, 58, 457–465.

Jensen, E. W., James, S. A., Bryce, W. T., & Hartnett, S. A. (1983). The family routines inventory: Development and validation. Social Science & Medicine, 17, 201–211.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen, & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 1–101). New York, NY: Wiley.

Maccoby, E. E., & Mnookin, R. H. (1992). Dividing the child: Social and legal dilemmas of custody. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Manlove, J., Logan, C., Moore, K. A., & Ikramullah, E. (2008). Pathways from family religiosity to adolescent sexual activity and contraceptive use. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 40, 105–117.

Mellin, A. E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Ireland, M., & Resnick, M. D. (2002). Unhealthy behaviors and psychosocial difficulties among overweight adolescents: The potential impact of familial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 145–153.

Miller, D. P., Waldfogel, J., & Han, W. (2012). Family meals and child academic and behavioral outcomes. Child Development, 83, 2104–2120.

Musick, K., & Meier, A. (2012). Assessing causality and persistence in associations between family dinners and adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 476–493.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., & Meece, D. W. (1999). The impact of after-school peer contact on early adolescent externalizing problems is moderated by parental monitoring, perceived neighborhood safety, and prior adjustment. Child Development, 70, 768–778.

Skeer, M. R., & Ballard, E. L. (2013). Are family meals as good for youth as we think they are? A review of the literature on family meals as they pertain to adolescent risk prevention. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 943–963.

Sen, B. (2010). The relationship between frequency of family dinner and adolescent problem behaviors after adjusting for other family characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 187–196.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085.

Steiger, J.H., & Lind, J.C. (1980). Statistically-based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the annual Spring Meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IO.

Turrisi, R., Mallett, K. A., Cleveland, M., Varvil-Weld, L., & Abar, C., et al. (2013). Evaluation of timing and dosage of a parent-based intervention to minimize college students’ alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74, 30–40.

White, J., & Halliwell, E. (2010). Alcohol and tobacco use during adolescence the importance of the family mealtime environment. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 526–532.

White, J., & Halliwell, E. (2011). Family meal frequency and alcohol and tobacco use in adolescence testing reciprocal effects. Journal of Early Adolescence, 31, 735–749.

Wood, M. D., Read, J. P., Mitchell, R. E., & Brand, N. H. (2004). Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 19–30.

Author Contributions

C.A.: Designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. G.C.: Assisted in literature searching, preliminary analysis, writing of the manuscript, and editing. K.K.: Assisted in literature searching, preliminary analysis, writing of the manuscript, table preparation, and editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Each of the authors has received up-to-date CITI training in the conduct of research with human participants, and all principles have been followed in the conduct of this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abar, C.C., Clark, G. & Koban, K. The Long-Term Impact of Family Routines and Parental Knowledge on Alcohol Use and Health Behaviors: Results from a 14 Year Follow-Up. J Child Fam Stud 26, 2495–2504 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0752-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0752-2