Abstract

The present study explored the lived experiences of Chinese immigrant parents in New York City who went through prolonged separation and faced challenges after reunification in the United States. The study assessed their attitudes, perceptions, and reactions to the separation and reunification process to gain better understanding of the ways prolonged separation and reunification impact on child development and family wellbeing. A phenomenological research approach was used to study qualitatively the narrative data from in-depth interviews. The analytical process was based on data immersion, coding, sorting codes into themes, and comparing the themes across interviews. The sample included 18 Chinese immigrant families who had sent their American-born children to China for rearing and reunited with their children within the past 5 years. Data analyses revealed specific themes that included reasons for separation, parenting methods, child’s initial adjustment, behavior, and family relationship, child’s social, emotional, and academic challenges, parental stress and challenges, and recommendations for services. This study contributed to our knowledge of prolonged separation, a common practice among a vulnerable, hard-to-reach immigrant population. It shed light on specific needs of Chinese immigrant families by examining closely the unique circumstances pertaining to prolonged separation, parenting practice, and related family challenges. An understanding of the approaches these families adopt to cope with life challenges may help inform practitioners in formulating service strategies for these families. Specific assessments in child-care, education, and health care settings are essential to prompt immediate follow-up and intervention when needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chinese (excluding Taiwanese) accounted for 84% of the Asian population in New York City (Asian American Federation 2013a). As the largest Asian group in NYC, the Chinese–American population had grown from 458,586 in 2008 to 506,768 in 2011, at a rapid 10.5% rate of increase (Asian American Federation 2013b). From 2000 to 2010, the number of Chinese–American children under the age of 18 years increased by 23% (Asian American Federation 2012). In the past two decades, a significant number of Chinese immigrant parents have sent their infants back to China to be cared for by relatives, and reunited with their children years later in the United States. A survey study of over 200 Chinese immigrant pregnant women at a community health center found that 57% of expectant parents planned on sending their infants back to China within 3–6 months; and more than 90% of them planned for their child’s return at 6 years of age (Kwong et al. 2009). The 2013 vital statistics of NYC showed that 8819 newborns delivered that year were of Chinese ethnicity (NYC DOHMH 2015). The growth in Chinese immigrant population would mean that there would be an increase number of U.S.-born infants being sent back to China for care, resulting in prolonged separation with their parents during the early years of their life.

Familial separation as a result of migration is not a new phenomenon. Across ethnic groups, adult immigrants in search of economic opportunities often leave their family behind in their home country (Abrego 2014; Chen 2013; Dreby 2012). The experience of immigrants separating with their families has been well documented in literatures categorized by groups, i.e., Mexicans (Dreby 2012), Hondurans (Schmalzbauer 2004), Salvadorans (Abrego 2014), Caribbean (Smith et al. 2004), and Chinese (Bohr and Tse 2009). Serial migration occurs when parents migrate to the new country first, and have their children sent for reunification at a later date (Smith et al. 2004). The practice whereby immigrant parents send their newborns to the home country to be raised, and have the children returned to the U.S when they reach school age is termed “reverse-migration separation” (Kwong et al. 2009). Reverse-migration separation was found to be prevalent in more recent Chinese immigrants from the Fujian Province. (Kwong et al. 2009). Part of the fastest-growing Chinese–American subgroup in the U.S., many Fujianese immigrants enter this country through illegal means and owe large financial debts to those who arrange for their arrival (Chen 2013). These immigrants, many of whom arrived in U.S. without extended families, generally work long hours in restaurants and/or garment factories for low wages without benefits (Kwong et al. 2009). Despite their undocumented status, and risking exposure and deportation, they are pressured to seek employment in order to support their transnational families (Chen 2013).

For families with working mothers, having children cared for by grandparents is a very common practice in China (Chu et al. 2011), Taiwan (Sun 2008), and Asian communities in the U.S. (Asian American Federation 2014). Low-income Chinese immigrants without extended family are faced with the dilemma of whether to raise their children in the U.S. or have them sent back to home country to be raised. In case of the latter, the extended family in China would assume the responsibility of caring for the American-born infant. Maintaining transnational ties with the home country is common amongst immigrants acclimating to a new country (Zentgraf and Chinchilla 2012). Orellana et al. (2001) discussed the importance of maintaining such ties: The children would get to know their relatives, learn the native language, and appreciate their cultural roots. For Chinese immigrant parents sending their infants back home for rearing, economic and career needs, as well as desire to preserve original culture were among the main reasons (Bohr and Tse 2009). In addition, Kwong et al. (2009) found that immigrant parents’ lacking confidence and experience in childrearing and their inability to afford child-care costs in the U.S. also precipitated the decision on prolonged separation.

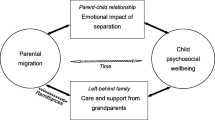

Despite efforts on part of Chinese immigrant parents to maintain some level of communication with caregivers (mostly grandparents), there are notable concerns associated with physical separation of parent and child (Bohr and Tse 2009; Kwong et al. 2009). Bohr (2010) argued that prolonged separations could have an adverse effect on parent-child attachment, the psychological development of children, and adjustment of parents. Several studies have shown that maternal separation was associated with maternal depression as well as the children’s future emotional and psychological development (Mäki et al. 2003; Miranda et al. 2005; Veijola et al. 2004). Bowlby (1976)’s classical attachment theory suggested that a child’s anger and aggressive behavior could be attributed to separation and interrupted relationships between the child and the primary caregiver. Prolonged separation during the first 5 years of life was associated with lack of affection and persistent delinquency (Bowlby et al. 1953). A recent attachment study by Tornello et al. (2013) also found that infants who spent frequent overnights away from the primary caregiver experienced greater attachment insecurity than those who consistently stayed with their primary caregiver. Of the limited number of studies done on Chinese immigrants in North America in the areas of parenting and child development, several found that Chinese immigrant families who had prolonged parent-child separation experienced elevated risks of socio-emotional and behavioral problems in the child, as well as strained parent-child relationships (Bernstein 2009; Bohr and Tse 2009; Cheah and Li 2010; Kwong et al. 2009).

Studies on child development and parenting education identified a number of social adversity factors that might impact on parent intervention outcomes (Beauchaine et al. 2005; McInTye and Phaneuf 2008). Social adversity factors include socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal depression, marital problems, poor social support, and negative life stresses (Deater-Deckard 2005). Parents who experienced chronic stress tended to use harsh reactive parenting approach and were less able to respond constructively to their children’s ever-changing competencies and difficulties (Deater-Deckard 2005). Low coping competence (difficulty in social and emotional situations) in children was found to correlate to low academic performance and high parental stress level (Soltis et al. 2013). The study by Cheah et al. (2009) on Chinese immigrant mothers and their preschoolers found that when these mothers perceived a higher level of parenting hassles, they might be less likely to use their psychological strengths to engage in warm and responsive parenting and foster their child’s autonomy development. Chinese immigrant parents who experienced higher level of parental stress had more parent–child conflicts and were more likely to engage in harsh discipline methods (Liu 2014). Children who experienced prolonged separation are at risk of “double jeopardy”: separation from their parents at infancy and having to adjust to parents who were emotional strangers with high stress in life (Valtolina and Colombo 2012). The parents of prolonged separation had adjustment issues as “new parents” themselves, and were more likely to use harsher discipline on their children, resulting in their children exhibiting poor behavioral emotional adaptations (Cheah and Li 2010; Yates et al. 2010).

Previous studies discerned the key factors considered by Chinese immigrant parents intend on sending their infants back to China (Bohr and Tse 2009; Bohr 2010; Kwong et al. 2009). The present study explored specifically the lived experiences of these immigrant families that went through prolonged separation and faced challenges after reunification in the U.S. The focus of this study was to elicit the experiences of these families and to gain better understanding of the ways prolonged separation and reunification impact on child development and family wellbeing. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to (1) explore the factors that contributed to the decision of Chinese immigrant parents in NYC to send their children back to China; (2) understand their attitudes, perceptions, reactions, and experiences to the separation and reunification process; (3) assess how family wellbeing and child adjustment and behaviors are impacted by prolonged separation and post-reunification challenges; and (4) solicit recommendations about resources, support, and assistance these families would need to address their specific concerns and challenges.

Method

Participants

This study used purposive sampling to select Chinese immigrant families, specifically Fujianese immigrants, who had sent their American-born children to China for rearing and reunited with their children within the past 5 years (Patton 2014). To recruit potential participants, the researcher and a research assistant published two news articles in local media outlets, and distributed a total of 605 recruitment flyers and 80 copies of the news articles during seven major health fairs and outreach activities targeting Chinese immigrant populations. Of 565 individuals approached, 455 were not eligible for the study. Among 110 who were eligible, 84 declined to participate due to reasons such as time constraints, inconvenience, privacy and confidentiality concerns, and fear of legal involvement. Of the 26 who signed up for the study, 18 families were successfully interviewed.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of 18 participants. Three participants were male and 15 were female. The average age was 38.83 years (SD = 9.54). All participants were immigrants from China and their average length of stay in the U.S. was 10.14 years (SD = 4.28). The majority (77.8%) reported an annual income below $30,000. The majority (94.4%) received a high school education or less and spoke English poorly or could not speak English at all (66.7%). Eight participants (44.5%) rated their health status as fair or poor. Of the 18 families, a total of 25 children were separated from their parents and the majority of them were separated when they were infants. Of the 25 children, 20 have reunited with parents. Of these 20 children, the average age of the infant at the time of separation was 7.5 months old. At the time of reunification, their average age was 4 years old. The average time during separation was 3.27 years.

Procedure

This study used a phenomenological research approach to explore the participants’ perceptions, perspectives and understandings of prolonged separation and reunification, and the meanings they attributed to their experiences (Merriam 2009). The focus of phenomenological inquiry is what these immigrant families experience in regard to prolonged separation, and how they interpret those experiences. Prior to interviewing participants who have had direct experience with the phenomenon, the researcher reviewed his knowledge and experiences to become aware of personal prejudices and preconceptions. These prejudices and preconceptions were then “bracketed” (Merriam 2009, p.25). Participants were asked semi-structured interview questions to assess their attitudes, perceptions, and experiences regarding prolonged separation and reunification. Their responses formed the basis for assessment and evaluation of the possible impacts of prolonged separation and related family factors on child development and family wellbeing. The researcher, a bilingual (Chinese) social work educator and mental health professional, conducted all interviews in the participants’ native dialect. Each interview lasted for an hour. All participants consented to be audiotaped; they were given pseudonyms to protect their identities. Every effort was made to ensure that participation in the study would be voluntary and that no participants should feel coerced to participate in the study. All interviews were then transcribed into English. Only the researcher and the research assistant had access to the data. The Human Research Protection Program of Hunter College approved the study. The researcher had no conflict of interests and complied with all applicable regulations, institutional policies, and conflict-of-interest management oversight plans issued by Hunter College.

Measures

An interview guide (see Appendix 1) was designed to include open-ended questions, and where necessary, “probes” or follow-up questions were used to clarify responses and increase the richness of responses (Patton 2014). Specific themes and domains of questions covered in the interview guide include: parent–child relationship and communication, parental stress and challenges, sources and availability of support, perceived benefits and consequences of prolonged separation arrangement, child’s and family’s physical and emotional adjustments, specific parenting practice for a more positive reunification, and recommendations for services. Prior to the actual interview, each participant was asked to provide basic demographic information such as age, gender, country of origin, marital status, income, education, social, family, and health data.

Data Analyses

All demographic data were entered into and analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS). Most of the quantitative data were categorical in nature. Frequency distributions were presented. A step-by-step approach was used to study qualitatively the narrative data from in-depth interviews, ensuring that themes and interpretations that emerge from the analytical process address the original research questions (Grinnell and Unrau 2013). The analytical process consisted of data immersion, coding, sorting codes into themes, and comparing the themes across interviews. ATLAS.ti, the qualitative analytical software program, was used to code and organize the data (Friese 2014). Open coding was used to scrutinize the interview data’s body of words, phrases, and sentences (Grinnell and Unrau 2013). After the interview text was coded and classified, a comprehensive list of codes and categories were generated. All transcript data, codes, categories, and quotations were reviewed for interconnection as well as relevance to the central themes of the research questions. Emerging themes were identified based on their centrality in relation to other categories, frequency noted in the data, and their clarity and inclusiveness. To enrich the analysis, the researcher noted questions, understandings, and reflections on the data and emerging concepts on analytical memos (Miles and Huberman 2014).

There were threats to the validity and trustworthiness of the interview data due to the fact that certain Chinese words have no absolute equivalents in English. This issue in translation raises questions on the extent to which translated data accurately reflects the meaning, feelings, and experience of participants. Several steps were taken in this study to improve credibility and validity of study data (Yin 2014). A bilingual (Chinese) research assistant transcribed all interviews into English. The transcripts were then checked to ensure accuracy and completeness of interview data prior to coding. Peer debriefing was held immediately following each interview to ensure the capturing of major themes. It was also utilized to provide consistent checks for accuracy of each transcribed interview, and for the integrity of the researcher’s interpretive process. During data analysis, the researcher checked whether descriptions and emerging themes on the data were both clear and accurate. The researcher also examined the representativeness of key findings, as well as quotations used to illustrate the themes.

Results

Reasons for Separation

Table 2 summarizes the major themes regarding attitudes, perceptions, and experiences of Chinese immigrant parents toward prolonged separation and reunification. In this study, the key reasons for Chinese immigrant parents to send their infants to China were financial hardship (78%) and lack of affordable and quality child care (78%). These findings concurred with a previous study (Kwong et al. 2009) on the subject. Other reasons mentioned by participants included the availability of support by extended family in China, mother’s lack of knowledge and experience in childrearing, and peer acceptance of this common practice in the Fujianese communities.

Most participants (13) indicated that they had wished for their infants to remain in the U.S. under their own care, and expressed their unwillingness to part with their child. However their financial situation required that both parents worked long hours in low-paying jobs, resulting in limited time and resources to care for the child. These parents believed they had “no choice” but to send the child to China.

Because of financial constraints we had to send her back to China. Truth is, children will fare better in America…. As parents, we felt sad to be separated with our child. Some parents let their child stay in China for a long period of time due to financial constraints. They work hard for their living in America. (P6)

I would feel a lot of pressure between working and daily living. I had to take care of her. I had to feed her and do many things for her. We couldn’t handle too much as we had to work…. Many of our fellow countrymen sent their children back to China because they had no choice…. It’s all about our financial problems. (P14)

For these participants, separation was considered inevitable if they wanted to improve their current financial situation in order to provide a better future for their children. One participant (P7) shared, “We always want our next generation to have better life. We want to save more money for our kids to spend in the future…. Two people can earn more money. If only my husband works, he will be stressed out. If we both work for a few more years, we can save more money for our kids.”

Participants in this study voiced that the lack of affordable and available child-care services was another key reason why they chose to send their child to China. They indicated that the child-care expenses in the U.S. were too high. Some participants felt that if they had child-care support of extended family in the U.S., it would have made a difference. Grandparents and other relatives were preferred over nannies or daycare workers as caregivers for some participants. As one participant (P17) stated, “Because we don’t know the caregiver, we would feel anxious letting the nanny take care of our children. It would be better to find a relative to care for our daughters. However, we didn’t have many relatives living here.”

The growth of Chinese immigrant population in U.S. means more immigrant parents are finding their own ways and means to meet the challenges of childrearing. For the past two decades, as prolonged separation grew more prevalent within the Fujianese community, it has gained increasing acceptance among this more recent group of Chinese immigrants.

It’s a common practice for us to send our child back to China to be raised by our parents. After giving birth to our child, we sent the child back and we were able to work for a few years. We would bring our child back at the age of five because they have to go to school… Here in America, Fujianese immigrants are not able to take care of their children because they have to work. They send their infants to China for a period of three to 5 years. (P5)

Most participants repeatedly cited financial hardship as the main reason to send their child back to China. Other themes that emerged from the data analyses were interrelated or were an effect of financial hardship. If new immigrants were able to obtain jobs with stable work schedules and higher wages, they could more likely afford the cost of childcare and a better living environment for their infants in the U.S.

Parenting Methods (China vs. US)

In this study, many Chinese immigrant families (15) engaged grandparents and other relatives in China as caregivers. The majority of participants (15) used webcams to communicate weekly with their children and caregivers. Of particular note was the fluidity of child-care arrangements among some of these families. Separate and multiple caregivers are common in raising siblings within the same family.

My son was sent to Canada. He wasn’t sent back to China but my daughter was… My mother, her grandma, took care of her … My father took care of my daughter as well…. My son’s aunt took care of him. Because my son’s paternal grandparents migrated to Canada, I sent him to Canada to be taken care of by them. (P7)

My parents were in poor health. They were old. Within the first 2 years after my child was back to China, my parents died. After my son was sent back to China, he became very sick and was in the hospital for 3 days. My parents felt that it was difficult to care for him. 8 months after that, my father died. My son was then sent to his aunt’s care. He stayed there for about 2 months. His grandmother felt lonely so he was again sent back to her. She took care of him by herself. When my son was two to 3 years old, he became cognizant of his environment. But soon his grandmother passed away. Then he got sent back to his aunt’s care. About 6 months ago, his aunt told me that she was unable to take care of him due to her age. Then I brought him back to America. (P1)

Many participants (14) in this study had disagreements with the caregivers in China on child discipline issues. They stated that the caregivers often spoiled their children. In addition, the caregiver did not share much information about the child, or follow the requests of parents from the U.S. Two participants below shared childrearing methods used by caregivers in China.

My kids were being spoiled a lot by their grandparents. The grandparents do not have the ‘heart’ to discipline the kids. They did not dare to spank the kids if they were wrong…. My parents always fulfilled my daughter’s every wish. They bought whatever she asked for even when she had no need for it at all. They loved her so much that they won’t discipline her. They prepared everything for her every day. (P7)

My mother was an elderly woman. She did whatever my son asked. She did not fix his bad habits at all. While in China, he didn’t pick up after himself and he was too messy. Since our reunion, he has exhibited some undesirable behavior. My mother did not discipline him well…he showed a lot of behavioral problems after coming back from China. I asked my mother whether she parented my son the same way she parented me. She said no. Asked why, and she said she felt bad for my son because his parents did not live with him. She just let him do whatever he wanted. (P4)

In traditional Chinese culture, providing food is an expression of love. Grandparents in China tend to overfeed the grandchildren and this often results in poor eating habits, putting the children at risk of obesity. A participant (P5) commented, “My mother thinks children should have four to five meals a day. However, I think my daughter is overweight… Actually elders don’t really know how to take care of the children besides providing food and lodging. They keep preparing food for the kids. They still maintain their traditional values.”

Some participants (5) believed that there were better healthcare facilities and educational opportunities for children in the U.S. If parents could raise their child in the U.S., they would impose stricter disciplinary measures and set more limits to help children develop self-efficacy and independence skills.

If our children lived with us, we can tell them what they are allowed to do. We hope they can develop skills such as independence and self-efficacy so they can do certain things on their own. Because their grandparents cared them for, we did not know how or what our children were taught. There is a big difference between children who were raised in America and those raised in China. (P7)

Every time I spoke with her aunt over the phone, I told her to be strict with my daughter. She couldn’t just spoil my daughter… It’s natural that my daughter will come to rely more on her aunt. She will think that her aunt is the best person. If I can’t do for her what her aunt does, I will be the bad person. Moreover, it will be difficult to discipline her in the future. (P14)

Child’s Initial Adjustment, Behavior, and Family Relationship

Bohr (2010) argued that prolonged separations could have an adverse effect on attachment and on the psychological development of children. Many parents (13) in this study shared that after prolonged separation, their children had adjustment issues initially after they reunited with their parents. The returned children were antagonistic, irritable, needy, and disorganized. They were described as noncompliant, self-centered, and stubborn. They tended to compete with their siblings who had been living in the U.S., resulting in sibling rivalry and jealousy.

After returning home from China, he did the opposite of what we asked…he is better now but still easily frustrated. He is very impatient. Sometimes he fights with his sister. He does not like to interact with others.… After he came back he loved to compare himself against others…. He wanted everything other kids in school had. When he saw other kids possessing better things than he had, he would damage their belongings. He is always alone and can’t seem to get along with other classmates. He gets angry easily and talks weird. Sometimes he will smash stuff…. He can’t sleep alone. If he can’t see me at night, he will cry. He lacks sense of security. (P1)

In the beginning it was not easy taking care of him. He resisted when I asked him to do things. He would not listen and ignored me when I instructed him to do something…When I told him to write his homework neatly, he tore it up angrily and scattered it everywhere. I got mad at him so I punished him by having him stand in a corner. He was upset and started to hit me… He did not seem happy, and he was timid… He did not want to come back to the U.S. in the beginning. He thought China was better than America. He felt more at home with people such as his grandparents around. (P2).

Part of the adjustment difficulties these children went through could likely be attributed to the profound sense of loss and separation from their caregivers in China. Many participants (9) reported that their children often missed their grandparents terribly and they saw their parents as strangers.

After she was back, she kept asking about returning to China. She was taken care of by her grandma in China, and she had difficulty adjusting after coming back. She was not that close to me…She cried a lot during the first week of her return. She kept looking for her grandma. Also, she did not speak to me unless I spoke first. (P5)

He missed his grandmother very much as she was his caregiver in China. During the first week after I brought him back to the U.S., he frequently asked for his grandmother…. He would not call me “mom”. I was a stranger to him. I didn’t know what was going on in his mind since he had been away from me for a year. (P4)

Some parents (4) reported that their children felt abandoned or rejected after being sent to China and they grew resentful of their abandonment. Because prolonged separation usually began when the child was an infant, parents did not have the opportunity to establish a close relationship with the child. The resulting parent-child relationship was described as distant, strange, and detached.

She would think that we were the ones who wanted to send her away. Every negative consequence she suffered, she blamed us for it.… ‘Because you and daddy sent me back to China, I couldn’t learn English. You created the problems.’ Why would a little girl think that? (P10)

She learned a few English words from school so she often said to me, ‘I don’t like mommy.’ I said, ‘You don’t like me? I don’t like you either.’ One time, I felt very angry with her. I said to her, ‘Get out of here and please pack your clothes too.’ To my surprise, she really did that…. After the incident, I realized I shouldn’t say that to her.… It would cause serious problems if she did run away from home. It’s bad for us or it will ruin her future. (P9)

Due to 4 years of separation from our daughter, there was little communication between us when she first returned from China. We didn’t actually share a profound feeling of closeness. Then, we started to redevelop the family bond with her…Her mother takes care of her all the time but their relationship is not close. She acts differently than her brother. (P12)

Child’s Emotional, Social, and Academic Challenges

Research on child development and parenting issues of Chinese immigrant families have found that children from these families are at elevated risks of socio-emotional, learning, and behavioral problems, due to disruptive relocation circumstances, prolonged separation, and reunification (Bohr and Tse 2009; Kwong et al. 2009). Many parents in this study (11) reported that after reunification, their children experienced speech delays and difficulties with English pronunciation. Speaking little or no English, these children were saddled with a high level of anxiety while they struggled to communicate with their teachers and fellow classmates.

I asked him why he didn’t tell the teachers that he did not understand. He said he was afraid his teacher would be mad at him or beat him…. When these kids first enter school, they do not understand English. If they were afraid to make contact with teachers, they cannot understand the lessons due to the language barrier.… Once he learned more English, he would know how to communicate with teachers. I spent more than a year trying to change his behavior. (P2)

Because she needed to attend private school, we moved to another State. All students in her class were Americans. In those days, she cried every day. She started to cry before I brought her to school and she cried while at school. Her eyes were swollen when she came home. I was very angry and did not like her. Because she cried every day, she stopped attending school there… She said she couldn’t speak English with American students. She did not get used to speaking English. Nobody talked to her and she did not understand the teacher. (P5)

Parents also reported that their children displayed a range of behavioral problems such as being rowdy and disruptive, lacking self-control, and lying. As one participant (P16) summarized, “They [teachers] said he did not behave properly and lacked self-control. He wouldn’t be still. Sometimes he did not listen to the teachers. His behavior improved later but he remained disorderly. He lacked self-control and self-awareness: He would touch others inappropriately or whispered to his classmates during class. He did not pay attention to the teachers.”

Parental Challenges

The majority of participants (78%) reported an annual family income below $30,000. On top of financial hardship, they felt stressed and physically exhausted from taking care of their children and were overwhelmed by child-care responsibilities. The participants noted their lack of freedom, short temper, and constant worries. The high level of parental stress resulted in greater parent-child conflicts, leading to harsher disciplinary measures.

If you berate him at home, he would threaten to call the police. Sometimes if I am really mad, I would say, ‘You get out, I don’t want you as my child.’ He would say, ‘In America, parents have to raise their children from birth until 18. If you throw me out, I will call the police.’…I have learned to be patient in my conversations with him. But he would turn into a bully and point a finger to you and say, ‘you stupid idiot’… I become impatient and give in to bad temper. (P1)

I have not had a good night’s sleep since they were back. Sometimes they cough at midnight. Sometimes I have to help replace their blankets when they move around in bed…. My husband asked me to talk to them peacefully when I am mad at them. I told him I felt angry. I have to take care of them 24 h a day. (P3)

We only rented a one-room apartment and my kids leave their toys everywhere. When I get out of bed, I usually step on a toy and get hurt. I get angry and call them out for their misconduct. They also leave food out on the table and let it get cold. (P5)

Due to strained parent-child relationships, many of these immigrant families were at higher risk of developing behavioral and psychosocial issues. The following two participants reported their encounters with child welfare system as a result of their childrearing methods and tense parent–child relationships.

I said to my daughter, ‘See, you brought the police here to take you away. They did this because you didn’t listen to me. If you continue doing so, they are going to take you away and we will lose a child. Should you be happy or should we be happy? I told you not to say anything but you did.’… After this incident, I think the separation and reunification had affected our family. When she came back from China, you didn’t really know what her thoughts were. You didn’t know her personality at all. Because you don’t know her well, incidents are bound to happen. (P9)

She said, ‘My mother beats me and my father beats me.’ Sometimes she would hurt herself then lies to her teachers. Some Chinese teachers understood our difficulties. However, she went straight to the school nurse’s office. She told the nurse, ‘I got hurt and my parents did it.’ So the nurse had to call the police…. Her teacher was Chinese so she understood the situation. She knew that it wasn’t child abuse. However, the nurse didn’t know anything about us. She only knew that a kid got hurt and therefore she must call the police.… They [the police] gave us a warning not to beat the child again, or else they would have to take her away. (P12)

Parents’ Regret about Separation

Most participants (10) in this study expressed strong and mixed feelings about the separation and reunification process. After sending their infants to China, they missed their child and worried about their child’s wellbeing from thousands of miles away. The missed opportunity to raise their child themselves and the resulting ramifications come to light upon reunification. The lack of attachment culminated in a parent-child relationship that was awkward and disconnected. They felt hurt from constant rejection from their child. Caregivers in China, primarily grandparents and relatives, tend to spoil the child making discipline much more difficult after reunification. Extra effort is required of parents to correct their child’s negative and unhealthy habits formed in the former all-permissive environment. All these contribute to a sense of regret many parents felt about the decision they made to send their child to China.

I really want to see him and take care of him during his different developmental stages. Unfortunately, I missed this opportunity.… I see now how every child who was sent back to be raised is totally different from those who are raised here. My son did not bond with me when he first came back. He was like a stranger. He did not want to be close to me or have any intimacy such as hugging and kissing. He felt strange in a new environment. (P2)

I have a best friend who lives in Virginia. She gave birth to her first child. Then she sent the child back to China…. Her daughter was diagnosed with anorexia. Because there was no other solution, she had to bring her daughter back from China. Now, her daughter is very weak, with a very poor physique … she often got sick because of her poor physique… The child’s grandparents felt guilty. They were responsible for taking care of the child and they took her to see different doctors. But nothing worked. Now, they often blame themselves….The responsibility to care for their grandchildren places a great psychological burden on these old folks. The grandparents couldn’t get rid of the scar on their memories. When my friend brought her child back for a visit, the grandparents cried at the sight of their frail and feeble granddaughter. (P11)

Recommendations from Participants

Participants were asked what types of support, resources, and assistance they needed the most to help address their concerns and strengthen their parenting skills. Some of them suggested more organized outdoor parent-child activities where parents and children could interact in a more opened, relaxed setting. Such activities would also help bring together children of similar age, as well as their parents of similar experience. More workshops on parenting and effective communication with children should be provided to help foster stronger parent–child relationships.

We need more social activities for kids that involve playing and socializing with other kids. Kids who came back from China would want more activities such as singing and dancing. If I attend different workshops about parenting, I could learn how to raise my son better … how to communicate and develop close relationships with the child, and how to respect one another. (P1)

You can organize more parent-child activities on how to communicate better with children, or different outdoor activities such as family health day…. It is better for children to have more interaction with parents and other children.… More community workshops about raising children are also a good way to help these families. (P2)

Several participants (4) indicated that they would not send children back to China if there were more child-care service options available to them in the U.S. They suggested further advocacy for the specific needs of low-income Chinese immigrant families. These families needed more concrete financial assistance in the form of free or affordable child-care services.

I hope they will provide more low-cost day care services. They can help to take care of our child for a few hours. Or they can provide inexpensive child-care services. We might not make such painful decision if we could afford day care services here. (P5)

Many of our fellow countrymen are of poor health and experience financial hardships while supporting their children. Their family situation is even worse than mine. I hope the government can provide support and assistance to these families so that they can reduce their life stress. Then they would not need to send their child back to China. (P14)

We hope we can have affordable day care service. We don’t wish for free day care but at least one we can afford. If we don’t send the children back, we could only afford to hire nannies to take care of them [at home] because day care services are expensive.… I hope there is an agency that provides day care services for children on weekends. (P8)

Discussion

The present study specifically explored the lived experiences of Chinese immigrant families who went through prolonged separation and faced numerous challenges after they were reunited with their children. “It would be very painful that the family bond will be broken. The ties of kinship may not be as close as it used to be but I have no choice.” This comment from a participant (P14) elucidated the fact that the choice these parents made to be separated from their newborns was not entirely a “voluntary” decision. Many voiced regret in not having their child with them in the U.S. They clearly stated that they had “no choice” but to send their child to China; and that having their child cared for by grandparents and relatives was the best option that they had. On societal level, as a significant segment of immigrant parents continue to practice prolonged separation, many American-born children of Chinese immigrants are not being raised by their birth parents during the formative years of his or her life. At a time when other urban disadvantaged populations, with the help of early childhood intervention services, are trying to strengthen families and promote social cohesion, the immigrant families that practice prolonged separation are heading the opposite direction. Their family ties threatened instead of strengthened, these immigrant families are trapped within a cycle of financial and emotional dilemmas.

The findings of this study suggested that the prolonged-separation and reunification arrangement might impact on the emotional and psychosocial wellbeing of both the parent and the child involved. While the separation process put parents through much emotional turmoil, the reunification process exerted a toll on both the parents and the child. The experiences of these families gave a glimpse of the negative impacts of under-developed, or absence of, parent-child attachment and bonding as put forth by attachment theory and object relations theory. The parents came to realize that although there were benefits in sending their children back to China—namely better child-care assistance and support, and retention of language and culture—the price they paid would likely include poor parent–child relationship, attachment challenges, and socio-emotional and behavioral issues among the returning children.

By eliciting the stories, narratives, and experiences of Chinese immigrant families, this study shed light on the separation and reunification process as a whole. It explored the ways in which Chinese immigrant families adjusted under the challenges of prolonged separation and reunification. It also highlighted the unique circumstances pertaining to prolonged separation, parenting practice within the Chinese cultural context, and related family challenges that might impact on children’s behavior and development. The findings of this study illustrated that child development and parental behaviors were embedded within larger systems of influence. While this study shed some light on a number of issues faced by families who practiced prolonged separation—a subject matter that was largely understudied—there still exists a need for more systematic studies employing longitudinal study designs and standardized measures. Such studies would help assess both short-term and long-term psychosocial and mental health effects on children who went through prolonged separation. More in-depth inquiry, with a focus on attachment and separation within cultural and family contexts, would help further our understanding of the impact of prolonged separation on these families.

This study was limited by a small sample size. Many potential participants turned down the invitation to participate in the study out of fear of legal involvement. The small sample size meant our findings could not be generalizable to a larger population of Chinese immigrants. In addition, the current study did not include standardized clinical assessment tools. Future studies might focus on a clinical assessment of this population employing parental mental health screens, as well as assessing the child’s emotional, behavioral, and psychological developments. Another limitation related to the accurate translation of Chinese words for which there was no absolute equivalents in English. Despite these limitations, this study contributed to our knowledge of prolonged separation, a common practice among a vulnerable, hard-to-reach immigrant population. It shed light on specific needs of Chinese immigrant families who have to send their child to China to be raised while the parents work in the U.S. By examining closely the unique circumstances pertaining to prolonged separation, parenting practice, and related family challenges (low income, parental stress, lack of social support), preventive measures could be developed to promote and safeguard the overall wellbeing of parent and child. An understanding of the approaches these families adopt to cope with life challenges would help inform practitioners in formulating service strategies for these families. Specific assessments in child-care, education, and health care settings are essential to prompt immediate follow-up and intervention where needed. In the long run, appropriate and adequate healthcare, psychological and educational interventions could be designed to meet the precise needs of these families.

The knowledge derived from these families’ experiences might also expand the awareness of human-service and healthcare practitioners, and contribute to their appreciation of an under-studied yet growing population in the U.S. To work effectively with these families at the time of reunification, practitioners have to grasp what it means for these families to engage in prolonged separation within the larger cultural and familial context. An understanding of these immigrant families’ experiences, struggles, and challenges would provide service practitioners across health, education, and social service systems with a wealth of reference points in their concerted efforts to assist these families toward integration both within their family and to the community beyond.

References

Abrego, L. J. (2014). Sacrificing families: Navigating laws, labor, and love across borders. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Asian American Federation (2012). Asian Americans in New York City: A decade of dynamic change 2000-2010. New York, NY. http://www.aafny.org/pdf/AAF_nyc2010report.pdf.

Asian American Federation (2013a). Asian Americans of the Empire State: Growing diversity and common needs. New York, NY. http://www.aafederation.org/doc/FINAL-NYS-2013-Report.pdf.

Asian American Federation (2013b). Profile of New York City’s Chinese Americans: 2013 Edition. Asian American Federation Census Information Center. New York, NY. http://www.aafederation.org/cic/briefs/chinese2013.pdf.

Asian American Federation (2014). The state of Asian American Children. New York, NY. http://www.aafederation.org/doc/AAF_StateofAsianAmericanChildren.pdf.

Beauchaine, T. P., Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2005). Mediators, moderators, and predictors of one-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 371–388.

Bernstein, N. (2009, July 23). Chinese-American children sent to live with kin abroad face a tough return. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/24/nyregion/24chinese.html.

Bohr, Y. (2010). Transnational infancy: A new context for attachment and the need for better models. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 189–196.

Bohr, Y., & Tse, C. (2009). Satellite babies in transnational families: A study of parents’ decision to separate from their infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(3), 265–286.

Bowlby, J. (1976). Attachment and loss, volume II, separation: Anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J., Frey, M., & Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1953). Child care and the growth of Love. London: Penguin Books.

Cheah, C. S. L., Leung, C. Y. Y., Tahseen, M., & Schultz, D. (2009). Authoritative parenting among immigrant Chinese mothers of preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(3), 311–320.

Cheah, C. S. L., & Li, J. (2010). Parenting of young immigrant Chinese children: Challenges facing their Social-emotional and intellectual development. In E. L. Grigorenko, & R. Takanishi (Eds.), Immigration, diversity, and education (pp. 225–241). New York, NY: Routledge.

Chen, F. (2013). Fujianese immigrants fuel growth, changes. Voices of NY. http://voicesofny.org/2013/06/fuzhou-immigrants-fuel-growth-changes-in-chinese-community/.

Chu, C. Y. C., Xie, Y., & Yu, R. R. (2011). Coresidence with elderly parents: A comparative study of Southeast China and Taiwan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 120–135.

Deater-Deckard, K. (2005). Parenting stress and children’s development: Introduction to the special issue. Infant & Child Development, 14, 111–115.

Dreby, J. (2012). The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 829–845.

Friese, S. (2014). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Grinnell, R. M., & Unrau, Y. A. (2013). Social work research and evaluation: Foundations of evidence-based practice (10th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kwong, K., Chung, H., Sun, L., Chou, J., & Taylor-Shih, A. (2009). Factors associated with reverse-migration separation among a cohort of low-income Chinese immigrant families in New York City. Social Work in Health Care, 48(3), 348–359.

Liu, S.W. (2014). Parental stress, acculturation, and parenting behaviors among Chinese immigrant parents in New York City (Doctoral dissertation). ProQuest LLC. (3620826).

Mäki, P., Hakko, H., Joukamaa, M., Läärä, E., Isohanni, M., & Veijola, J. (2003). Parental separation at birth and criminal behavior in adulthood: a long-term follow-up of the Finnish Christmas Seal Home Children. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 354–359.

McInTye, L. L., & Phaneuf, L. K. (2008). A three-tier model of parent education in early childhood - Applying a problem-solving model. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27(4), 214–222.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A method sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miranda, J., Siddique, J., Der-Martirosian, C., & Belin, T. (2005). Depression among Latina immigrant mothers separated from their children. Psychiatric Services, 5(6), 717–720.

New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. (2015). Summary of vital statistics 2013, the City of New York. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/vs/appendixa-2013.pdf.

Orellana, M. F., Thorne, B., Chee, A., & Lam, W. S. E. (2001). Transnational childhoods: The participation of children in processes of family migration. Social Problems, 48, 572–591.

Patton, M. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schmalzbauer, L. (2004). Searching for wages and mothering from afar: The case of Honduran transnational families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1317–1336.

Smith, A., Lalonde, R. N., & Johnson, S. (2004). Serial migration and its implications for the parent-child relationship: A retrospective analysis of the experiences of the children of Caribbean immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10, 107–122.

Soltis, K., Davidson, T. M., Moreland, A., Felton, J., & Dumas, J. E. (2013). Associations among parental stress, child competence, and school-readiness: Findings from the PACE study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 649–657.

Sun, S. H.-L. (2008). ‘Not just a business transaction’: The logic and limits of grandparental child-care assistance in Taiwan. Childhood, 15, 203–224.

Tornello, S. L., Emery, R., Rowen, J., Potter, D., Ocker, B., & Xu, Y. (2013). Overnight custody arrangements attachment, and adjustment among very young children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(4), 871–885.

Valtolina, G. G., & Colombo, C. (2012). Psychological well-being, family relations, and developmental issues of children left behind. Psychological Reports, 111(3), 905–928.

Veijola, J., Mäki, P., Joukamaa, M., Läärä, E., Hakko, H., & Isohanni, M. (2004). Parental separation at birth and depression in adulthood: A long-term follow-up of the Finnish Christmas Seal Home Children. Pychological Medicine, 34, 357–362.

Yates, T. M., Obradovic, J., & Egeland, B. (2010). Transnational relations across contextual strain, parenting quality, and early childhood regulation and adaptation in a high risk sample. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 539–555.

Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zentgraf, K. M., & Chinchilla, N. S. (2012). Transnational family separation: A framework for analysis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(2), 345–366.

Author Contributions

K.K.: designed and executed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. Q.Y.: assisted with data analyses and collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Interview Guide

Assess the current parent–child communication and relationship other factors that may affect it.

-

How often do you speak to your child? How is your communication and relationship with your child?

-

Is there anything that you may not have thought about before the separation, but realize now about your child or your situation?

-

How is your financial situation now that you have reunited with your child?

Learn about transnational parenting and perceived benefits and consequences of separation

-

What were the rewards/benefits of having your children raised in China while you live in the U.S.?

-

What were the negative consequences of having your children raised in China while you live in the U.S.?

-

How did you communicate with your family back home during separation? What was your relationship like with the caregiver of your children back home? How did you handle disagreements with the caregiver?

Learn about the child’s physical and emotional adjustment since the reunification

-

How is the child’s ability to learn and adjust to living with you in a new environment?

-

How did your child react initially when she/he saw you and the family again after several years’ separation?

-

How is your child doing in terms of his/her educational, medical and behavioral conditions?

-

Have you noticed ways in which separation and reunification have affected your child’s behavior or mood?

Learn about the parent’s experience and his/her family’s physical and emotional adjustment since the reunification.

-

How did you and your family (including the child’s siblings, if applicable) react toward the reunion? How do you feel physically and emotionally now that you’ve reunified with your child?

-

What was it like for you to take on responsibility to care for your children after such long separation?

-

What are the impacts of separation and reunification, and how that affected your family in the past few years?

-

If you had the choice, would you repeat this decision with your other children? Why or why not?

Learn about resources, support, coping used by the family during separation and since the reunification.

-

How are you and your family coping with the child’s return and presence? What kinds of coping adjustments/changes have you made?

-

What concerns do you have now regarding your family?Do you need help to address those concerns?

-

Did you learn anything in the U.S. about parenting that influences how you parent your children?

-

What types of support, resources, and assistance you need most to help with your parenting?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwong, K., Yu, Q.Y. Prolonged Separation and Reunification among Chinese Immigrant Children and Families: An Exploratory Study. J Child Fam Stud 26, 2426–2437 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0745-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0745-1