Abstract

Anxiety disorders are one of the most widespread psychological diseases in adolescence, which may lead to impairment in several areas of life and has been demonstrated a risk factor of other psychiatric disorders. One of the most widely used self-report measures to assess multiple symptoms of anxiety in youth is the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS). Literature suggests that anxiety symptoms vary across cultures to some extent. It has been found that individuals from collectivistic culture report higher levels of anxiety disorders than those from individualistic culture. Poland is a country whose culture was traditionally collectivistic; but now Poland is undergoing social and economic system transformation, which is taking it closer to individualistic culture. However, SCAS has never been validated in Polish samples, and thus the current study aimed (1) to assess the psychometric properties (structural validity and reliability) of SCAS in a sample of 303 Polish adolescents, (2) to examine gender differences, (3) to test the divergent validity of SCAS by relating it to the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and (4) to compare the mean levels with Chinese (collectivistic) and Italian (individualistic) samples. The results confirmed that the Polish version of SCAS showed good reliability and validity. Polish girls showed higher physical injury and generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms than boys. Furthermore, Polish adolescents reported higher levels of anxiety than Italian youth but lower levels of anxiety than their Chinese counterparts. Implications for professionals and researchers are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are one of the most widespread psychological diseases in childhood and adolescence (Beesdo et al. 2010). They may lead to impairment in several areas of life and are a risk factor of other psychiatric disorders (Antony and Stein 2009). One of the most widely used self-report measures to assess multiple symptoms of anxiety in nonclinical children and adolescents is the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence 1997). It is designed according to the six anxiety dimensions described in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). SCAS has been validated and used in many countries (e.g., the US, Australia, UK, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Cipro, Greece, Spain, China, Japan, Brazil, Iran, Nigeria, Delvecchio et al. 2014), showing good psychometric properties in different cultural settings (Essau et al. 2012). So far, several studies have been carried out to assess the factorial structure of the SCAS using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Most of them find a model that involves six discrete but correlated factors (e.g., Orgilés et al. 2016). However, evidences suggest that the factorial structure of SCAS as well as the level of anxiety symptoms differ across cultures (Delvecchio et al. 2014; Ishikawa et al. 2009; Orgilés et al. 2016).

Prior literature has emphasized the existence of cultural differences in the mean level of anxiety disorders, as data has showed that adolescents from collectivistic cultures report higher levels of anxiety than their individualistic counterparts (Baxter et al. 2013; Delvecchio et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2012), which may be due to the socialization practices characterized by collective norms (e.g. the filial piety, obedience to authority), familistic values, and higher levels of self-control and emotional restraint (Zhao et al. 2012; Xie and Leong 2008). By contrast, socialization practices in individualistic cultures encourage autonomy and independence (Essau et al. 2008), which may contribute to the lower level of anxiety problems in adolescence. For example, in a recent study, Delvecchio et al. (2014) found that Chinese community adolescents show significantly higher levels of anxiety symptoms compared to Italian ones. Parallel results were obtained from parents’ reports, with Chinese parents considering their children to be more anxious than do Italian parents (Li et al. 2016). Zhao et al. (2012) found that Chinese adolescents score higher than Dutch (Muris et al. 2000) and German adolescents (Essau et al. 2008). Moreover, Colombian children were found to be more anxious than Australian ones (Crane Amaya and Campbell 2010).

So far, no studies have validated the SCAS or examine the level of anxiety disorder among Poland adolescents. According to Różycka et al. (2013) cross-cultural study, Poland can be defined an individualistic country. Hofstede’s model of national culture (http://geert-hofstede.com) is a useful frame to compare different cultural dimensions, one of which—and the most relevant for the current study—is the individualism vs. collectivism dimension. This refers to people’s self-image orientation in terms of “I” or “we” along a scale ranging from 1 to 100 with higher scores indicating higher individualist attitude. In line with this, Poland is categorized as an individualistic culture (the Individualism score is 60), even if its score falls very close to the midpoint (M = 50). As suggested by Lubiewska (2014), Poland hosts significant inter-generation differences, with elderly showing stronger collectivistic orientation than the young generation who shows higher individualistic tendencies. In a similar vein, Brycz et al. (2015) advocated that Poland is a country traditionally collectivistic but that now is undergoing social and economic system transformation, which is taking Poland closer to individualistic culture. As highlighted by Stefaniak and Bilewicz (2016), Poles host several ethical, religious and social differences in one culture, due to their historical heritage (World War II) and the fast economic development. These inner and deep transformations involving intra-personal and interpersonal changes have affected the whole society, particularly the youngest generations, and therefore attention should be given to their psychological well-being. Anxiety symptoms are one of the most prevalent diseases in adolescence and strictly connected with transformations and changes, which emphasizes the need to shed light on this matter.

Beside cultural issues, anxiety symptoms are also affected by gender, as gender differences have been found in previous studies (Delvecchio et al. 2014; Orgilés et al. 2016). Indeed, girls have been thought to report more anxiety disorders than boys (Costello et al. 2003; Craske 2003), but the reason for this difference is unclear. A possible explanation is that girls are faced with more psychological and social challenges than boys, thus having higher levels of anxiety (Essau et al. 2012). In addition, genetic predispositions also show that girls are more susceptible to anxiety symptoms than boys (Silberg et al. 2001).

Furthermore, a number of papers have been devoted to analyzing the risk and protective factors linked to anxiety disorders in adolescence. Positive self-esteem has been listed as a crucial factor to promote psychological well-being in general (Birndorf et al. 2005; Trzesniewski et al. 2006). Lee and Hankin (2009) found that low level of self-esteem predicts prospective symptoms of anxiety in adolescence; more specifically they reported that the association between anxious attachment and anxiety symptoms is mediated by dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. However, recently, Maldonado et al. (2013) investigated the impact of anxiety symptoms on self-esteem development using a longitudinal study and found that early adolescents’ anxiety disorder predicts self-esteem development. This approach is quite uncommon due to the universal perception that low self-esteem is considered a risk factor for mental illness among adolescents but not vice versa. However, their results suggested that anxiety categories impact differently on self-esteem development. For example, social phobia, overanxious disorder and OCD are the most important predictors for self-esteem, whereas SAD does not bear significant impact on self-esteem (Maldonado et al. 2013). Nevertheless, although the link between anxiety and self-esteem has been studied in different perspectives, both views underline the importance of this association.

To date, no international paper on anxiety disorders in Polish adolescents has been published. Furthermore, SCAS has never been validated in Polish samples. In order to fill these issues, the current study aimed (1) to assess the factorial structure of SCAS: according to previous theoretical and empirical research on SCAS, the six factor model was hypothesized to better represent the factorial structure of Polish data (Orgilés et al. 2016). Good internal consistency was expected for the SCAS total and subscales (Orgilés et al. 2016); (2) to examine the gender differences in mean levels of SCAS: higher levels of anxiety were expected among girls than boys (Essau et al. 2011); (3) to test SCAS divergent validity with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES, Rosenberg 1965): higher levels of anxiety symptoms were hypothesized to negatively correlate with positive self-esteem (Lee and Hankin 2009; Maldonado et al. 2013); and (4) to compare current Polish sample’s anxiety level with that of Chinese and Italian adolescents with similar age range published in a previous work (Delvecchio et al. 2014): due to the cultural changes affecting Poland in recent years, it was hypothesized that Polish adolescents report higher level of anxiety symptoms than Italians (representative of the individualistic culture) but lower scores than Chinese (representative of the collectivistic culture) adolescents. It was expected that Polish adolescents would express lower anxiety than Chinese due to fewer social and emotional pressures and demands they are exposed to (Li et al. 2008). However, considering Polish hierarchical society and elaborate etiquette in social and relational interactions, they were expected to score higher than Italians where autonomy and low emphasize on self-control are shared values (Delvecchio et al. 2014).

Method

Participants

Three hundred and three Polish adolescents (176 boys and 127 girls; age range: 15–19 years; Mage = 16.86 years, SD = 0.87) were recruited from high schools located in Bydgosz, a large city in Northern Poland. The selected schools mainly served middle-class families (SES, Hollingshead 1975), with approximately similar basic quality of life, within urban and suburban school districts. Exclusion criteria included psychiatric hospitalization or psychological treatment or testing over the past 2 years.

Procedures

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards for research outlined in the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association 2010). Approval by the Ethical Committee for Psychological Research was obtained from university of Bydgosz (Project title: Anxiety in adolescents and its selected determinants; approval date: 19.11.2015). School approval and parents’ signed consent were sequentially obtained before data collection and adolescents provided their assent before participation. No incentives were awarded; voluntary participation and anonymity were emphasized. Administration was implemented during regular classes.

Measures

Anxiety

The self-report Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence 1997, 1998; Spence et al. 2003) was used to assess participants’ anxiety. This scale consists of 44 items, 38 of which reflect specific symptoms of anxiety and 6 are filler items excluded in scoring. The 38 anxiety items comprise six different subscales: panic and agoraphobia (e.g., item 21—“I suddenly start to tremble or shake when there is no reason for this”), separation anxiety (e.g., item 8—“I worry about being away from my parents”), fears of physical injury (e.g., item 23—“I am scared of going to the doctors or dentists”), social phobia (e.g., item 35—“I feel afraid if I have to talk in front of my class”), obsessive-compulsive problems (e.g., item 42—“I have to do some things in just the right way to stop bad things happening”), and generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms (e.g., item 1—“I worry about things”). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, and 3 = always). All items can be summed to compute a total score; higher scores indicate higher anxiety levels. Since there was no Polish version of the SCAS, a back translation was conducted following Van de Vijver and Hambleton’s (1996) guideline and is now available on http://scaswebsite.com.

Self-esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES, Rosenberg 1965) was used to assess respondents’ level of self-esteem. A Polish version of RSES was used (Laguna et al. 2007). This scale consists of ten items rated on a 4-point scale (from “1 = strongly disagree” to “4 = strongly agree”), with five items being negatively worded and the other five items positively worded. Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. RSES has been used among Polish adolescents, showing adequate psychometric properties (e.g., Schmitt and Allik 2005). Sample items included “I feel that I have a number of good qualities” (positively worded) and “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure” (negatively worded). The internal consistency was .85 in this study.

Data Analyses

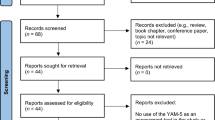

First, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out in Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) to evaluate whether the original 6-correlated factor model reported by Spence (1998) was adequate for the Polish sample. A robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) was used because the data were ordinal. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were used to judge model’s goodness of fit. Value of RMSEA lower than .08 and values of CFI and TLI higher than .90 were considered as indicative of adequate fit (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). Second, internal consistencies of subscales and total scale of the SCAS were calculated. Third, independent t-tests were conducted to determine if there were gender differences in the total scale and subscales. Significance was judged based on p value and effect size (Cohen’s d, small, medium, and large effects were .20, .50, and .80, respectively, Cohen 1988). Fourth, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to capture the association between anxiety and self-esteem. Finally, Polish adolescents’ anxiety levels were compared with previous results obtained from Chinese and Italian samples (Delvecchio et al. 2014) using one-sample t-tests.

Results

The results of the CFA showed that the six-factor structure was adequately fit, χ 2 (650) = 1332.355, RMSEA = .059 (90% CI = [.054, .063]), CFI = .944, TLI = .940. Factor loadings ranged from .428 to .908 and all of them were significant at p < .001 level (Table 1). Inter-correlations between subscales and total score are presented in Table 2.

Cronbach’s Alpha for the total scale was .96 (95% CI = [.95, .97]), .91 for panic and agoraphobia (95% CI = [.90, .93]), .85 for separation anxiety (95% CI = [.82, .87]), .72 for fears of physical injury (95% CI = [.67, .77]), .77 for social phobia (95% CI = [.73, .81]), .85 for obsessive-compulsive problems (95% CI = [.82, .87]), and .83 for generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms (95% CI = [.79, .86]).

The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3. Among the total score and the six dimensions of the SCAS, boys reported significantly higher levels of fear of physical injury (boys: M = 5.04, SD = 2.72; girls: M = 3.58, SD = 3.38, t(301) = 4.151, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .479) and generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms (boys: M = 6.53, SD = 3.21; girls: M = 5.41, SD = 3.58, t(301) = 2.865, p = .004, Cohen’s d = .330) than girls. No other significant differences were found.

Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the association between anxiety symptoms and self-esteem measured by the RSES (Table 4). The results showed that anxiety symptoms were negatively associated with self-esteem at statistically significant level.

One-sample t-tests were carried out to compare the current results with a previous study done among Chinese and Italian samples (Delvecchio et al. 2014). We chose these samples because the age group was comparable. As shown in Table 5, the results showed that Polish adolescents reported substantially higher levels on total anxiety, fears of physical injury, obsessive-compulsive problems, separation anxiety, panic and agoraphobia, and lower levels on generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms than did Italian adolescents; Polish adolescents reported significantly lower levels of total anxiety, social phobia, and obsessive-compulsive problems than did Chinese adolescents.

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess anxiety symptoms in Polish adolescents adopting a cross-cultural perspective and to stimulate research on this topic in Poland. The choice of Poland, a country undergoing a process of cultural transformation which is slowly moving its cultural attitude from collectivistic to individualistic orientation, guided the decision of comparing this sample with Italian (individualistic) and Chinese (collectivistic) adolescents. Therefore, the first purpose was to assess the structural validity and reliability of the Polish version of SCAS. The second aim was to evaluate gender differences in SCAS mean levels. The third purpose was to assess divergent validity of SCAS and the last goal was to compare the levels of anxiety symptoms reported by Polish with the ones reported by Chinese and Italian adolescents.

In line with previous studies on SCAS, the six-correlated factor model showed adequate fit (Delvecchio et al. 2014; Essau et al. 2011; Spence et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 2012). The strong correlations among the six subscales highlighted the high comorbidity of anxiety disorders (Whiteside and Brown 2008) and advocated the existence of a high-order anxiety factor (Di Riso et al. 2013). SCAS appeared as a reliable tool, as the total scale showed excellent internal consistency and the subscales showed good internal consistency. In line with previous studies, the fears of physical injury subscale displayed the lowest internal consistency, although still adequate (Delvecchio et al. 2014). Internal consistency for the Polish SCAS total and subscales was higher than the mean alpha coefficients reported in the recent meta-analysis (Orgilés et al. 2016). A possible explanation may be the differences in the mean age of the samples (Orgilés et al. 2016: 9-16 years old, M = 12.5; current study: 16–19 years old, M = 16.86) because Orgilés et al. (2016) found that the reliability of SCAS augments as children’s mean age increases.

Unexpectedly, no significant gender differences were found on the total score of SCAS. This result is in line with a study looking at the mean levels of state and trait anxiety in a small sample of psychotherapy-seeking Polish adults (21–40 years old) (Mielimąka et al. 2015). This study did not find significant gender differences and women reported slightly lower anxiety levels than men in a qualitative way. Although the sample features were very far from the one considered in our sample, Mielimąka’s et al. (2015) called for further research to address possible cultural-specific trends of anxiety symptoms in Polish culture. A further explanation may be linked to Polish school system which has a selective function for the society (Muchacka 2014), promoting the school as a preparation for the ability to compete for jobs and opportunities later in life (Wærdahl 2016). This therefore elicits anxiety symptoms in male and female students in similar ways. However, contrary to what we expected, significant differences were found for generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms and physical injury, with boys reporting higher symptoms than girls. Further research deepening on cultural meaning of gender role and its features is needed to address these unexpected results.

As expected, higher levels of anxiety symptoms were negatively correlated with self-esteem (Delvecchio 2013; Lee and Hankin 2009; Muris et al. 2016). In line with Maldonado et al. (2013), stronger negative correlations were found between self-esteem and obsessive-compulsive problems and generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms. However, the link between social anxiety and self-esteem was low. A possible explanation may concern the statistical analysis used: since the aim of the current study was to assess divergent validity of SCAS, instead of deepening on the etiology of anxiety disorders or self-esteem, correlation, instead of a linear mixed-effect model (Maldonado et al. 2013), was adopted. Moreover, this study referred uniquely to self-report measures, whereas Maldonado et al. (2013) assessed anxiety symptoms through interview. Due to the core role of protective variables for anxiety disorders in adolescence (Wenar and Kerig 2000) and the risk factor of anxiety disorder for self-esteem (Maldonado et al. 2013), future studies should adopt a longitudinal design as well as both non-clinical and clinical samples to shed new lights on these findings. Roberts (2006) claimed that self-esteem should be considered a key ingredient for treatment of anxiety disorders; moreover he highlighted the association between poor response to psychological treatment and individual’s low self-esteem. Deepening on the relationship between self-esteem and psychological maladjustment may promote clinicians to decrease anxiety disorder and increase psychological well-being by raising self-esteem (Maldonado et al. 2013).

Shifting to the cross-cultural comparison, Italian adolescents reported lower score on the total scale than Polish adolescents, which in turn, scored lower than Chinese youths. Regarding the subscales, Polish adolescents reported higher scores on separation anxiety, fears of physical injury, panic and agoraphobia and obsessive-compulsive problems than Italians. Moreover, Polish adolescents reported lower levels of social phobia and obsessive-compulsive problems than Chinese ones. Cultural as well as environmental reasons support these findings. A first explanation may be due to cultural stressors related to anxiety. For example, several authors explained Chinese adolescents’ anxiety symptoms referring to Chinese cultural principles such as filial piety and obedience to authority (Quach and Harnek Hall 2013), which, on the contrary, are not perceived as fundamental values to pursue by Italian and Polish parents or adolescents (Pearlin and Kohn 1966; Rabaglietti et al. 2012). In addition, the national school system may play a role for the exacerbation of anxiety symptoms in adolescence (Dello-Iacovo 2009). Specifically, the Chinese school system with its examinations that entitles students to enter into the higher education institutions which may decide their future may amplify anxiety symptoms during this stage of life (Zhao et al. 2012). Similarly, Polish school system with its selective and highly competitive mission may increase the chance to experience distress and anxiety in adolescence (Mielimąka et al. 2015). Although the Italian school system also comprehends exams to enter high schools as well as college and may cause a certain amount of pressure, there is no such a strict and competitive cut-off test and school pressure, resulting in a more flexible and relaxed school enrolment (Bertola and Checchi 2002). Furthermore, the ongoing inter-generation cultural transformation found in Poles who are moving from collectivistic to a more individualistic orientation may have resulted in lower anxiety levels than Chinese adolescents (collectivistic culture) but higher level than Italian ones (individualistic culture). Moreover, as suggested by Hofstede’s cultural model (2001), although Poland belongs to individualistic cultures, it is a hierarchical society, in which everyone has a place and which needs no further justification. This combination of hierarchical society and individualistic tendencies may “create a tension” (http://geert-hofstede.come). In addition, previous studies claimed that anxiety runs in families, prompting for a high heritability of anxious symptoms from parents to child (Drake and Ginsburg 2012; Ollendick and Grills 2016). Turner et al. (1987) reported that children of parents with an anxiety disorders are seven times more at risk for developing an anxiety disorder than children of parents without such disorders. As mentioned, it is known that anxiety symptoms affect greater collectivistic than individualistic countries (Delvecchio et al. 2014). Since Poland is currently undergoing this cultural transformation, it may need some years and generations to show more clear cultural-oriented patterns of anxiety. At last, Wojciszke (2004) suggested that complaining is linked to reduced moods and increased negative emotions, decreased life satisfaction and optimism, belief in the negativity and injustice of the social world. Wojciszke (2004) and Wojciszke et al. (2009) emphasized that complaining mood is widespread among Poles and it is connected to affective correlates, showing a positive correlation with anxiety symptoms. Although this finding added possible explanation to cultural related anxiety differences, further studies are needed to assess complaining attitude and its relationships to anxiety in other cultural backgrounds.

Furthermore, unexpectedly, Italian adolescents reported higher scores than Polish in generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms. As suggested by Beesdo et al. (2009) those symptoms increase during adolescence and young adulthood. On the other hand, Polish adolescents reported higher scores than Italian ones on fears of physical injury (i.e., fear of dark, fear of animals, fear of doctor), panic and agoraphobia and separation anxiety. Bruce and Sanderson (1998) suggested that those fears are mostly age-related and they mainly affect children. Thus, although participants of the current study have a similar age range to the ones enrolled in Delvecchio et al. (2014), Polish adolescents seem to be affected longer than Italians by children’s fears. Those findings claim for possible explanation linked to cultural as well as developmental-stage differences. Future studies should focus on this issue. Moreover, Polish adolescents seem more able to evaluate themselves on specific fears or situations than Italians who score higher on generalized anxiety.

However, we are aware that the present study holds several limitations. A first limitation is that this study focuses exclusively on limited geographical areas of Poland. Thus, results may not be well representative of the whole country. Second, since only community based adolescents were enrolled in the current research, findings cannot be extended to clinical populations. Future studies should deepen on this issue. Another limitation arises from the use of self-report measures that introduces issues of potential reporter-bias and shared method variance. Additional assessment modalities (e.g., structured interviews) together with self-report measures can contribute to a more objective and accurate understanding of anxiety (Lee and Hankin 2009; Silverman and Ollendick 2005). Moreover, this study enrolled uniquely adolescents’ point of view. A multiple-informant perspective may add relevant information about youths’ anxiety symptoms (Karver 2006; Grills and Ollendick 2002). In addition, future research with SCAS could be referred to the comparison between girls and boys in a cross-cultural point of view. Last but not least, additional variables should be taken into account to better understand anxiety symptoms in adolescence. Especially following a cross-cultural perspective, future studies should assess the specific values and beliefs that characterize a country (e.g. familism, individualism/collectivism, perception of social norms).

To conclude, findings from the current study revealed that the SCAS is a valid and suitable tool for the screening of anxiety symptoms with Polish adolescents. Moreover, in line with expectations, results confirmed that anxiety symptoms are affected to some extent by cultural issues, showing the need to consider the influence of culture when prevalence of anxiety as well as adolescents’ feelings and psychological adjustment are studied. Implications of the current study may reinforce the knowledge on anxiety symptoms in Polish adolescents and suggest that the SCAS is a useful and easy tool for psychological assessment and treatment planning.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. edn. Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx.

Antony, M. M., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baxter, A. J., Scott, K. M., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 43, 897–910. doi:10.1017/S003329171200147X.

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32, 483–524.

Beesdo, K., Pine, D. S., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2010). Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 47–57.

Bertola, G., & Checchi, D., (2002). Sorting and private education in Italy. CEPR Discussion Papers 3198, C.E.P.R. http://www.cepr.org/pubs/dps/DP3198.

Birndorf, S., Ryan, S., Auinger, P., & Aten, M. (2005). High self-esteem among adolescents: Longitudinal trends, sex differences, and protective factors. The Journal of the Adolescent Health, 37, 194–201.

Bruce, T. J., & Sanderson, W. C. (1998). Specific phobias: Clinical Applications of evidence-based psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Brycz, H., Różycka-Tran, J., & Szczepanik, J. (2015). Cross-cultural differences in metacognitive self. Economics and Sociology, 8, 157–164. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-1/12.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., & Angold, A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 837–844.

Crane Amaya, A., & Campbell, M. (2010). Cross cultural comparison of anxiety symptoms in Colombian and Australian children. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 8, 497–516.

Craske, M. G. (2003). Origins of phobias and anxiety disorders: Why more women than men? Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and quality education in China: An overview. International Journal of Educational Development, 29, 241–249.

Delvecchio, E. (2013). Protective and mediator factors for internalizing disorders in early and mid-adolescence. (Unpublished doctorate thesis). University of Padua.

Delvecchio, E., Mabilia, D., Di Riso, D., Miconi, D., & Li, J. (2014). A comparison of anxiety symptoms in community-based Chinese and Italian adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2418–2431. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-0045-y.

Di Riso, D., Chessa, D., Bobbio, A., & Lis, A. (2013). Factorial structure of the SCAS and its relationship with the SDQ: A study with Italian children. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 29, 28–35. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000117.

Drake, K. L., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2012). Family factors in the development, treatment, and prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 144–162. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0109-0.

Essau, C. A., Leung, P. W., Conradt, J., Cheng, H., & Wong, T. (2008). Anxiety symptoms in Chinese and German adolescents: Their relationship with early learning experiences, perfectionism, and learning motivation. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 801–810.

Essau, C. A., Olaya Guzmán, B., Pasha, G., O’Callaghan, J., & Bray, D. (2012). The structure of anxiety symptoms among adolescents in Iran: A confirmatory factor analytic study of the spence children’s anxiety scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 871–878.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X., Olaya Guzmán, B., & Ollendick, T. M. (2011). Psychometric properties of the spence child anxiety scale with adolescents from five European countries. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 19–27.

Grills, A. E., & Ollendick, T. H. (2002). Issues in parent–child agreement: The case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 57–83.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale-University. (Unpublished working paper).

Karver, M. S. (2006). Determinants of multiple informant agreement on child and adolescent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 251–262.

Ishikawa, S., Sato, H., & Sasagawa, S. (2009). Anxiety disorder symptoms in Japanese children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 104–111.

Laguna, M., Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K., & Dzwonkowska, I. (2007). Skala samooceny SES Morrisa Rosenberga—polska adaptacja metody [The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Polish adaptation of the scale]. Psychologia Spoleczna, 2, 164–176.

Lee, A., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional attitudes, and low self-esteem predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 219–231.

Li, H., Ang, R., & Lee, J. (2008). Anxieties in Mainland Chinese and Singapore Chinese adolescents in comparison with the American norm. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 583–594.

Li, J., Delvecchio, E., Lis, A., Nie, Y., & Di Riso, D. (2016). The parent-report version of the spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS-P) in Chinese and Italian community samples: Validation and cross-cultural comparison. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47, 369–383. doi:10.1007/s10578-015-0572-9.

Lubiewska, K. (2014). Znaczenie kolektywizmu i indywidualizmu dla zachowań rodzicielskich matek oraz przywiązania polskich i niemieckich nastolatków w perspektywie hipotezy kulturowego dopasowania [Cultural fit hypothesis: The impact of individualism-collectivism on maternal parenting and adolescent attachment in Germany and Poland]. Psychologia Społeczna, 2, 200–220.

Maldonado, L., Huang, Y., Chen, R., Kasen, S., Cohen, P., & Chen, H. (2013). Impact of early adolescent anxiety disorders on self-esteem development from adolescence to young adulthood. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 287–292.

Mielimąka, M., Rutkowski, K., Cyranka, K., Sobański, J.A., Dembińska, E., & Müldner-Nieckowski, L. (2015). Trait and state anxiety in patients treated with intensive short-term group psychotherapy for neurotic and personality disorders. Psychiatria Polska, 36. doi:10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/60537.

Muchacka B. (2014). Expert report on the characteristics of polish primary education. http://www.transfam.socjologia.uj.edu.pl/documents/32445283/1b4b6f7f-23da-4b60-985d-5fe63a38b957.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., Pierik, A., & de Kock, B. (2016). Good for the self: Self-compassion and other self-related constructs in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-clinical youths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 607–617. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0235-2.

Muris, P., Schmidt, H., & Merckelbach, H. (2000). Correlations among two self-report for child anxiety related emotional disorders and the spence children’s anxiety scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 333–346.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide. 7th edn Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ollendick, T. H., & Grills, A. E. (2016). Perceived control, family environment, and the etiology of child anxiety—Revisited. Behavior Therapy, 47, 633–642. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2016.01.007.

Orgilés, M., Fernández-Martínez, I., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Espada, J. P., & Essau, C. A. (2016). A systematic review of the factor structure and reliability of the spence children’s anxiety scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 333–340.

Pearlin, L. J., & Kohn, M. L. (1966). Social class, occupation and parental values: A cross national study. American Sociological Review, 31, 466–479.

Quach, A., & Harnek Hall, D. (2013). Chinese American attitudes toward therapy: Effects of gender, shame, and acculturation. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3, 209–222.

Rabaglietti, E., Vacirca, M. F., Zucchetti, G., & Ciairano, S. (2012). Similarity, cohesion, and friendship networks among boys an d girls: A one-year follow-up study among Italian children. Current Psychology, 31, 246–262. doi:10.1007/s12144-012-9145-2.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roberts, J. (2006). Self-esteem from a clinical perspective. In M. Kernis (Ed.), Self-esteem issues and answers: A sourcebook of current perspectives. New York: Psychology Press.

Różycka, J., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Khanh Ha, T. T. (2013). Wartości osobiste i kulturowe w ujęciu Shaloma Schwartza w kulturze polskiej i wietnamskiej [Schwartz’s personal and cultural values in Polish and Vietnamese cultures]. Psychologia Społeczna, 4, 408–421.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Test of significance and descriptive goodness of fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research, 8, 23–74.

Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Selfesteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and cultural-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 623–642.

Silberg, J., Rutter, M., Neale, M., & Eaves, L. (2001). Genetic moderation of environmental risk for depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 116–121.

Silverman, W. K., & Ollendick, T. H. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 380–411.

Spence, S. H. (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 280–297.

Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 545–566.

Spence, S. H., Barrett, P. M., & Turner, C. M. (2003). Psychometric properties of the spence children’s anxiety scale with young adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17, 605–625.

Stefaniak, A., & Bilewicz, M. (2016). Contact with a multicultural past: A prejudice-reducing intervention. International. Journal of Intercultural Relations, 50, 60–65.

Trzesniewski, K., Moffit, T., Poulton, R., Donnellan, M. B., Robins, R., & Caspi, A. (2006). Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 42, 381–389.

Turner, S. M., Beidel, D. C., & Costello, A. (1987). Psychopathology in the offspring of anxiety disorders patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 229–235.

Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1, 89–99.

Wærdahl, R. (2016). The invisible immigrant child in the norwegian classroom: Losing sight of polish children’s immigrant status through unarticulated differences and behind good intentions. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 5, 93–108.

Wenar, C., & Kerig, P. (2000). Developmental psychopathology: From infancy through adolescence. 4th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Whiteside, S., & Brown, A. (2008). Exploring the utility of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scales Parent- and Child-Report forms in a North American sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 1440–1446.

Wojciszke, B. (2004). The negative social world: Polish culture of complaining. International Journal of Sociology, 34, 38–59.

Wojciszke, B., Baryla, W., Szymków-Sudziarska, A., Parzuchowski, M., & Kowalczyk, K. (2009). Saying is experiencing: Affective consequences of complaining and affirmation. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 40, 74–84.

Xie, D., & Leong, F. T. (2008). A cross-cultural study of anxiety among Chinese and Caucasian American university students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development, 36, 52–63. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2008.tb00069.x.

Zhao, J., Xing, X., & Wang, M. (2012). Psychometric properties of the spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS) in Mainland Chinese children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 728–736. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.05.006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all parents’ participants included in the study. Oral consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delvecchio, E., Li, JB., Liberska, H. et al. The Polish Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale: Preliminary Evidence on Validity and Cross-Cultural Comparison. J Child Fam Stud 26, 1554–1564 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0685-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0685-9