Abstract

Loneliness is an adverse phenomenon that tends to peak during adolescence. As loneliness is a subjective state, it is different from the objective state of being alone. People’s attitudes toward being alone can be more or less negative or positive. Cultures differ in the form and meaning of social behavior, interpersonal relationships, and time spent alone. However, for cross-cultural comparisons to be meaningful, measurement invariance of the measure should be established. The present study examined measurement invariance of the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA) in a sample of 218 Belgian and 190 Chinese early adolescents, aged 11–15 years. Using nested multigroup confirmatory factor analyses, measurement invariance of the LACA across Belgium and China was established. More specifically, evidence was found for configural, metric, and partial scalar invariance. Because partial scalar invariance was established, the two cultural groups could be compared. No significant differences were found for peer-related loneliness. Regarding the attitudes toward aloneness, Belgian adolescents were more negative and less positive toward being alone than Chinese adolescents. The present study is encouraging for researchers who want to use the LACA for cross-cultural comparisons, in that we found evidence for measurement invariance across two disparate cultural groups speaking completely different languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Loneliness is an unpleasant, subjective experience that occurs when people perceive their social relations to be deficient in some important way, either quantitatively or qualitatively (Perlman and Peplau 1981). It is a universal phenomenon that is experienced by all human beings at some time in life, but tends to peak during adolescence (Qualter et al. 2015). Transient feelings of loneliness may represent normative experiences, but persistent feelings of loneliness may have detrimental effects on one’s mental and physical well-being across development (Ernst and Cacioppo 1999; Heinrich and Gullone 2006). One can feel lonely when alone, but also when surrounded by other people. Hence, loneliness is different from being alone, which is an objective experience. People differ in their general reaction toward being alone, that is, their attitude toward aloneness, which may be more or less negative or positive. There might be cultural differences in adolescents’ loneliness and negative and positive attitudes toward aloneness. However, before cross-cultural comparisons can be made, measurement invariance should be established.

Cultures differ in the form and meaning of social behaviors, and ascribe different values and meaning to interpersonal relationships (Chen and French 2008; Van Staden and Coetzee 2010). Cultures are often classified as varying in levels of individualism and collectivism. However, it is not clear which of these types of cultures has a higher prevalence rate of loneliness. Chen et al. (2004) and Lykes and Kemmelmeier (2014) both described two contrasting hypotheses. The first hypothesis stated that in more individualistic cultures, psychological autonomy and individuality are highly valued, which may lead to feelings of social alienation and loneliness among early adolescents. More collectivistic cultures are more group-oriented and provide more social support, which may lead to feelings of belongingness and interpersonal connectedness. The second hypotheses, by contrast, stated that in these collectivistic cultures, the thresholds for loneliness may be relatively low. Expectations for social connections may be higher and therefore more difficult to meet, which results in feelings of loneliness. In a similar vein, in individualistic cultures, the threshold for loneliness may be relatively high. The expectations for social connections may be lower and therefore easier to meet. These theoretical notions, however, are about the importance of social connections in a particular culture, whereas loneliness is about the negative feeling that arises when there is a gap between the actual and desired social connections. Cross-cultural theories about this gap between actual and desired social connections, that is, loneliness, have not been developed yet.

Empirical evidence on cross-cultural differences in loneliness in adolescents is scarce. When comparing adolescents from two more individualistic cultures, that is, Western Australia and the US, no significant differences in loneliness were found (Renshaw and Brown 1992). When comparing adolescents from two more collectivistic cultures, that is, Cape Verde and Portugal, no significant differences were found either (Neto and Barros 2000). When comparing more individualistic with more collectivistic cultures, finally, no significant differences in levels of loneliness were found for adolescents from Canada, Southern Italy, Brazil, and China (Chen et al. 2004), Russia and the US (Stickley et al. 2014), or Canada and China (Liu et al. 2015).

Cultures also differ in the value they place on time spent alone (Jones et al. 1985; Larson 1990). However, empirical evidence on cross-cultural differences in attitudes toward being alone in adolescence is almost non-existent. Some theoretical notions do appear in the literature. Regarding China and Western countries, two lines of reasoning can be found in the literature. According to the first line of reasoning, being alone might be valued more positively in Western countries and more negatively in China. In Western countries, assertiveness and autonomy are valued and being alone might be seen as an autonomous expression of personal choice (Liu et al. 2015). In China, however, greater value is placed on interdependence and commitment to the group. Being alone might therefore be seen as selfish and in conflict with the group orientation (Liu et al. 2015). Based on this reasoning, we might thus expect more positive and less negative attitudes toward aloneness in Belgian than in Chinese adolescents.

According to the second line of reasoning, being alone might be more negatively viewed in Western countries and more positively in China. Most people in modern Western society see being alone as an undesirable state (Suedfeld 1982). When alone, they actively try to find companionship or distract themselves, for example, by watching television. Also, when encountering another person who spends much time alone, they feel sorry for that person (Suedfeld 1982). In China, attitudes toward being alone might be more positive. Several translations are available in Chinese for the English term “solitude”, all including the root term “du”, which is also the root for “independence” and “uniqueness” in Chinese (Averill and Sundararajan 2014). Contrary to the more commonly noted Chinese emphasis on collectivism, there is a strong tradition of individualism in China. Similarly, in the West, a hermit is seen as an outsider, whereas in China this lifestyle is actually valued very positively and appears as a common theme in Chinese poetry (Averill and Sundararajan 2014). Based on this reasoning, we might expect more positive and less negative attitudes toward aloneness in Chinese than in Belgian adolescents.

Associations among various aspects of one’s attitude toward being alone can also be examined. Positive and negative attitudes toward aloneness can be measured in early adolescence using the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA; Marcoen et al. 1987). These attitudes were found to represent separate factors in confirmatory factor analyses on almost 10,000 Belgian children and adolescents (Maes et al. 2015a). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis showed a very small average correlation between the two (r = −.02; Maes et al. 2015b). However, the large majority of the studies included in that meta-analysis sampled from Western countries. It is not yet known whether a similar association between the two types of attitudes toward aloneness holds in adolescents from non-Western countries.

Peer-related loneliness can also be measured using the LACA. Associations between peer-related loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness again have been examined in Western countries mainly. Across studies, a small correlation was found between peer-related loneliness and negative attitudes toward aloneness (r = .15) and a medium correlation was found between peer-related loneliness and positive attitudes toward aloneness (r = .34; Maes et al. 2015b). However, it is not entirely clear how loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness are related (Majorano et al. 2015). For example, it could be the case that adolescents with positive attitudes toward aloneness create more opportunities to spend time alone and, as a consequence, may miss opportunities for social interactions leading to increased loneliness. However, it could also be the case that adolescents’ dissatisfaction with their relationships with peers makes them more inclined to spend time alone (Majorano et al. 2015). Cross-cultural studies on these issues have not been conducted yet.

For cross-cultural comparisons to be meaningful, researchers should first establish measurement invariance, which basically means that the instrument is measuring the same factor structure in the cultures that are studied (Chen 2007; Van de Schoot et al. 2012). However, none of the studies mentioned earlier has directly addressed measurement invariance. There are several levels of measurement invariance. The first level is called configural invariance, and implies that items are associated with the same factors for the cultures being compared. Analyses at this level examine whether the instrument that is used is configured to measure basically the same constructs. The second level is called metric invariance, and implies that the relations between specific scale items and the underlying constructs (i.e., factor loadings) are equal across cultures. Analyses at this level examine whether the latent constructs have exactly the same meaning across cultures (Van de Schoot et al. 2012). Metric invariance is important to establish when researchers aim to compare associations between variables across cultures. The third level of measurement invariance is called scalar invariance, and implies that not only the factor loadings, but also the levels of the underlying items (i.e., intercepts or constants when items are written as linear combinations of factors) are equal across groups. Scalar invariance should be established if researchers want to compare the means of different groups. Full scalar invariance, however, may be considered unrealistic, especially when diverse cultural groups are compared that speak completely different languages (Byrne and Watkins 2003; Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998). Partial scalar invariance, with at least two items per factor exhibiting scalar invariance, has been found sufficient to conduct comparisons of means across countries (Byrne et al. 1989; Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998).

A first aim of this study was to examine measurement invariance across Belgian and Chinese early adolescents for the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA; Marcoen et al. 1987). A second aim was to explore cross-cultural differences in loneliness and attitudes toward being alone. Regarding loneliness, previous studies on adolescents did not find significant differences across cultures. So we did not expect marked differences in loneliness. Regarding attitudes toward aloneness, two contrasting lines of reasoning appear in the literature and no empirical evidence is available as of yet. Therefore, we could not state strong a priori hypotheses about cultural differences in these attitudes, and we examined these differences in a more exploratory way. Finally, we also examined cross-cultural differences in the associations among loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness, again in an exploratory way.

Method

Participants

Two convenience samples were recruited for the present study. One sample came from the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium (N = 229) and the other came from Beijing, China (N = 200). The Belgian sample consisted of fewer females (53.7 %) than the Chinese sample (66.5 %), χ2(2) = 264.98, p < .001. All participants were between 11 and 15 years old, but the participants were somewhat younger in the Belgian sample (M = 12.80, SD = 0.74) as compared to the Chinese sample (M = 13.62, SD = 0.63), t(422) = 12.14, p < .001. Information about the socioeconomic background of the participants was not available, but the schools they were drawn from are known to serve primarily middle and upper middle class neighborhoods. Most Chinese adolescents (85 %) came from two-parent families, but this information was not available for the Belgian adolescents.

Because measurement invariance studies rely on fitting the observed data to a model, any bias in one of the groups due to outliers will affect factor loadings, intercepts, and error variances (Van de Schoot et al. 2012). Therefore, before examining measurement invariance, we removed participants with univariate outliers. That is, values more than 3 SD below or above the mean (7 cases in the Belgian sample and no cases in the Chinese sample) were removed. We also removed participants with multivariate outliers, based on their Mahalanobis distance values (Tabachnick et al. 2001; 4 cases in the Belgian sample and 9 cases in the Chinese sample). Little’s MCAR Test (Little 1988) indicated that the data could be considered as missing at random, χ2(434) = 459.04, p = .196. Therefore, we imputed missing values by means of the Expectation-Maximization procedure in SPSS 22.0, except for one case from the Chinese sample that had missing values on 27 of the 36 LACA items and therefore was removed from our dataset. This multi-step approach resulted in a final analytical sample of 218 Belgian and 190 Chinese adolescents.

Procedure

For the Belgian sample, information letters were sent to the schools, after which the principals of the schools were contacted. The participants filled out the LACA during regular school hours with a research assistant being present to introduce the study and answer questions. This assistant emphasized that participation was anonymous and voluntary, and that the adolescents could discontinue their participation at any time. This procedure was in line with the ethical standards at the time of data collection. The Chinese sample was drawn from the research project “Social Withdrawal, Friendship, and Social, School, and Psychological Adjustment in Chinese Adolescents”. Participants were first contacted by telephone. If both parents and adolescents expressed interest, parental consent and adolescent assent forms were mailed to the home with preaddressed and stamped return envelopes, along with the questionnaire measurements.

Measure

Participants filled out three subscales of the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA; Marcoen et al. 1987) in either Dutch or Chinese. These subscales, of 12 items each, measured peer-related loneliness (e.g., “I feel sad because I have no friends”), negative attitudes toward being alone (e.g., “When I am alone, I feel bad”), and positive attitudes toward being alone (e.g., “I want to be alone”). Items could be answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) often to (4) never. The fourth subscale of the LACA, measuring parent-related loneliness, was not included because the focus of the broader project for which the Chinese data were collected was on peer relationships (Wang 2014).

The LACA was translated carefully into Chinese by several members of the research team who were fluent in both English and Mandarin (Wang 2011). The LACA was then back-translated to ensure comparability with the English version. A variety of formal and informal strategies (e.g., repeated discussion in the research group, interviews with youth, and psychometric analysis) were applied to maximize the validity of the items. Earlier research indicated that the internal consistency of the subscales was high (i.e., α > .80) in studies from several countries (Maes et al. 2015b). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were also good, in both the Belgian and Chinese samples, for peer-related loneliness (α = .91 and .89, respectively), negative attitudes (α = .79 and .87, respectively), and positive attitudes toward being alone (α = .87 and .83, respectively). Average scores for Belgian and Chinese adolescents were similar to the values reported in previous research (Maes et al. 2015a) on the three subscales, that is, peer-related loneliness (M BE = 21.39, SD BE = 7.50 and M CN = 24.05, SD CN = 7.19), negative attitudes toward aloneness (M BE = 32.04, SD BE = 6.15 and M CN = 29.92, SD CN = 7.17), and positive attitudes toward aloneness (M BE = 29.06, SD BE = 7.37 and M CN = 32.52, SD CN = 6.53).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed in Mplus 6.11 (Muthén and Muthén 2007). To test for configural invariance, we examined whether a three-factor model (with the items of the three respective subscales loading on these three factors) yielded adequate fit in both samples separately. Configural invariance is further established by running a multiple group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with no constraints. To test for metric and scalar invariance, we compared the fit of multigroup models without constraints (i.e., not assuming metric or scalar invariance) to constrained models (i.e., by constraining intercept and loadings to the same values for both groups, to explore metric and scalar invariance, respectively). As recommended by Cheung and Rensvold (2002), we relied on multiple indices when evaluating model fit, including the Normed Chi Square, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the root means square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). The Normed Chi Square should be between 1.00 and 5.00, as values below 1.00 reflect poor model fit and values above 5.00 reflect a need for improvement (Schumacker and Lomax 2004). As regards CFI, .90 represents acceptable fit and .95 good fit. RMSEA and SRMR should not exceed .06 and .08, respectively, to consider the models as good-fitting models and should not be larger than .08 and .10, respectively, for mediocre-fitting models (Hu and Bentler 1999). Following the guidelines of Chen (2007), we regarded metric invariance as established if the difference in CFI (ΔCFI) between models with group-specific or common factor loadings is smaller than .010, ΔRMSEA is smaller than .015 and ΔSRMR is smaller than .030. We regarded scalar invariance as established if ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA and ΔSRMR between models with group-specific or common intercepts is smaller than .010, .015, and .010, respectively. In addition, we relied on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), which should be as low as possible.

We did not use items as indicators of latent factors, but we aggregated items into parcels. Numerous researchers have highlighted the psychometric merits of parcels relative to items, such as higher reliability and communality, and the advantages of models based on parcels regarding factor solution and model fit (Little et al. 2002). A reduction in model complexity when using parcels is expected to lead to more stable parameter estimates (Nasser-Abu Alhija and Wisenbaker 2006). Moreover, when the data to be analyzed are nonnormally distributed and coarsely categorized, is has been found that parameter estimates are usually unbiased, but that the model fit indices are adversely affected. Using parcels reduced this effect, without leading to biased parameter estimates (Bandalos 2002). However, these advantages of parceling only hold when the set of parceled items within a factor is unidimensional (Nasser-Abu Alhija and Wisenbaker 2006; Bandalos 2002). The factor structure of the LACA has been examined in previous studies (Goossens 2015; Marcoen et al. 1987; Maes et al. 2015a) suggesting that the items within each subscale of the LACA are unidimensional. This is confirmed by factor analyses on the data of the current sample. For each subscale, three four-item parcels were created based on the factor loadings obtained for the total sample, following the well-established item-to-construct balance parceling method described by Little et al. (2002).

For our second aim, that is, to explore cross-cultural differences in loneliness and attitudes toward being alone, we used the same multi-group models. When using a multi-group model in Mplus, the means of the latent variables for one group are automatically set to zero. The values of the means of the latent factors for the other group actually represent the difference in these means between the two groups. A two-tailed test is provided showing whether these values (i.e., the mean differences) differ from zero. Finally, we examined cross-cultural differences in correlations among the LACA factors between Belgian and Chinese adolescents in exploratory fashion, using the Wald Test.

Results

Configural invariance was first examined by running confirmatory factor analyses with the three-factor structure that was used to construct the LACA instrument for the two samples separately. Model fit is presented in Table 1. RMSEA was somewhat high, but the Normed Chi Square, CFI, and SRMR suggested an acceptable to good fit for both the Belgian and Chinese samples. Table 2 shows the model fit indices for the unconstrained and constrained models. The unconstrained model also showed acceptable fit, which meant that the number of factors and the pattern of factor loadings were roughly equivalent in both groups and that we could establish configural invariance. Evidence for metric invariance was also found (∆CFI = .003, ∆RMSEA = .003, ∆SRMR = .008), which meant that factor loadings could be regarded as equal in both groups. The AIC and BIC values confirmed this finding, as AIC is only somewhat higher and BIC is even lower when comparing the constrained with the unconstrained model.

Because full scalar invariance could not be established (∆CFI = .073, ∆RMSEA = .041, ∆SRMR = .017), we tested for partial scalar invariance. Based on the modification indices, we released the constraints of the intercepts for one parcel loading on the peer-related loneliness factor and for one parcel loading on the negative attitudes toward being alone factor. With these constraints released, evidence was found for partial scalar invariance (∆CFI = .019, but ∆RMSEA = .010, ∆SRMR = .001). The AIC and BIC values seemed to confirm this finding as they were not much larger in the partial scalar invariance model compared with the metric invariance model.

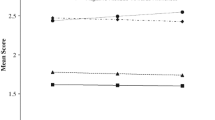

Because partial scalar invariance was established, we proceeded to compare the factor means between Belgian and Chinese early adolescents. In addition, we examined the correlations among the three factors, that is, peer-related loneliness, and negative and positive attitudes toward being alone, for the two samples separately. Because the two groups differed significantly regarding gender and age, we controlled for these variables by adding them to the model. In this analysis, age was centered around the grand mean of 13 years. The differences in factor means between the two groups and the correlations among the factors are presented in Table 3.

No significant differences were found between the Belgian and Chinese adolescents regarding peer-related loneliness, but significant differences emerged for attitudes toward being alone. On average, Belgian adolescents scored higher on negative and lower on positive attitudes toward being alone than Chinese adolescents. Correlations among the three factors were also compared between the two groups. Results from an overall Wald Test demonstrated no significant differences, χ2(3) = 5.06, p = .17. Results from separate Wald tests for each pair of correlations also indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p = .09 to .45).

Discussion

In all psychological research, it is essential to establish measurement invariance when groups are compared (Byrne and Watkins 2003). The large majority of cross-cultural studies on loneliness, however, have not explicitly addressed this issue. Some cross-cultural researchers replicated the factor structure across cultural groups (i.e., configural invariance), but such evidence is not sufficient to conduct meaningful comparisons across groups. The present study examined more demanding levels of measurement invariance for the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA; Marcoen et al. 1987) in Belgian and Chinese early adolescents. In line with previous research in Belgium (Maes Klimstra et al. 2015a) and Italy (Cicognani et al. 2014), the model reflecting the proposed factor structure of the LACA yielded a good fit for both the Belgian and Chinese sample. In addition to configural invariance, we established metric and partial scalar invariance.

In addition, because partial scalar invariance could be established (Byrne et al. 1989; Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998), we explored cross-cultural differences in loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness. First, the Belgian and Chinese adolescents in our study did not differ on peer-related loneliness. This result is in line with previous studies that found no significant differences in loneliness between adolescents with diverse cultural backgrounds. These studies have used other measures of loneliness, including a single-item measure and two well-known loneliness measures, that is, the Children’s Loneliness Scale (Asher et al. 1984) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al. 1980). Despite this variety of measures, all studies show similar results, which seems to suggest that there are no differences in levels of loneliness in adolescents from different countries.

Second, we explored cross-cultural differences in attitudes toward aloneness, which has not been done before. We found that the Belgian adolescents in our sample showed greater negative and less positive attitudes toward being alone than the Chinese adolescents. This finding is in line with previous findings (Suedfeld 1982) that indicated that in the Western world, being alone is seen as an undesirable state. Our findings are also in line with research (Averill and Sundararajan 2014) that emphasized the Chinese traditions of eremitism (i.e., living in seclusion from social life) and individualism. However, replication of these results is needed, as this is the first study to examine attitudes toward being alone from a cross-cultural perspective. Third, we examined cross-cultural differences in associations among loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness between Belgian and Chinese adolescents and found no differences in this regard. For both groups, negative and positive attitudes toward aloneness were negatively related. In addition, peer-related loneliness was positively related with both attitudes toward aloneness in both Belgian and Chinese adolescents. However, although we found no significant differences in these associations between the two groups, the size of the associations seem to differ and additional research on these correlations is needed.

Besides the innovative aspect of this study, there are also some limitations to keep in mind. Both samples were of medium size and not nationally representative. We were only able to establish measurement invariance for Belgian adolescents from the Dutch-speaking part of the country and Chinese adolescents from Beijing. Future research should aim to replicate our results using larger and nationally representative samples. Such samples could include, for instance, a more diverse set of participants, such as children and adolescents from other regions of Belgium and China and participants with other cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Furthermore, the present study examined measurement invariance only. This is an important requirement before groups can be compared, but it is not the only one. Other types of biases might exist as well (Van de Vijver and Tanzer 2004) and future studies should address these. One such study could be a more qualitative study with open interviews to investigate whether Belgian and Chinese adolescents themselves mention similar feelings, thoughts, and behaviors when talking about loneliness and attitudes toward being alone. Finally, no data were available for the fourth subscale of the LACA, that is, parent-related loneliness, which should be included in future research.

Despite these limitations, the present study extends the current literature on loneliness in significant ways. We found evidence for measurement invariance of the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents across two disparate cultural groups speaking completely different languages. In addition, we confirmed previous research that found no differences in loneliness in adolescents with a different cultural background. Finally, we extended the literature by examining cross-cultural differences in attitudes toward aloneness in an exploratory way. The findings regarding the latter topic, which question traditional views on solitude in collectivistic cultures, are in need of replication in future research on larger and more representative samples.

References

Asher, S. R., Hymel, S., & Renshaw, P. D. (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55, 1456–1464. doi:10.2307/1130015.

Averill, J. R., & Sundararajan, L. (2014). Experiences of solitude. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 90–108). New York, NY: Wiley.

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 78–102. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthen, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 456–466.

Byrne, B. M., & Watkins, D. (2003). The issue of measurement invariance revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 155–175. doi:10.1177/0022022102250225.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834.

Chen, X., & French, D. C. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 591–616. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606.

Chen, X., He, Y., Oliveira, A. M. D., Coco, A. L., Zappulla, C., Kaspar, V., & DeSouza, A. (2004). Loneliness and social adaptation in Brazilian, Canadian, Chinese and Italian children: A multi-national comparative study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1373–1384. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00329.x.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Cicognani, E., Klimstra, T., & Goossens, L. (2014). Sense of community, identity statuses, and loneliness in adolescence: A cross-national study on Italian and Belgian youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 414–432. doi:10.1002/jcop.21618.

Ernst, J. M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1999). Lonely hearts: Psychological perspectives on loneliness. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8, 1–22. doi:10.1016/s0962-1849(99)80008-0.

Goossens, L. (Ed.). (2015). De Leuvense Eenzaamheidsschaal voor Kinderen en Adolescenten: Handleiding [Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents: Manual]. Unpublished manuscript, Leuven, Belgium.

Heinrich, L. A., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 695–718. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jones, W. H., Carpenter, B. N., & Quintana, D. (1985). Personality and interpersonal predictors of loneliness in two cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1503–1511.

Larson, R. W. (1990). The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10, 155–183. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(90)90008-R.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. doi:10.2307/2290157.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007sem0902_1.

Liu, J., Chen, X., Coplan, R. J., Ding, X., Zarbatany, L., & Ellis, W. (2015). Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,. doi:10.1177/0022022114567537.

Lykes, V. A., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2014). What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 468–490. doi:10.1177/0022022113509881.

Maes, M., Klimstra, T., Van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2015a). Factor structure and measurement invariance of a multidimensional loneliness scale: Comparisons across gender and age. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1829–1837. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-9986-4.

Maes, M., Van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2015b). A reliability generalization study for a multidimensional loneliness scale: The Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment,. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000237.

Majorano, M., Musetti, A., Brondino, M., & Corsano, P. (2015). Loneliness, emotional autonomy and motivation for solitary behavior during adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3436–3447. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0145-3.

Marcoen, A., Goossens, L., & Caes, P. (1987). Loneliness in pre through late adolescence: Exploring the contributions of a multidimensional approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 561–577. doi:10.1007/bf02138821.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nasser-Abu Alhija, F., & Wisenbaker, J. (2006). A Monte Carlo study investigating the impact of item parceling strategies on parameter estimates and their standard errors in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling, 13, 204–228. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1302_3.

Neto, F., & Barros, J. (2000). Psychosocial concomitants of loneliness among students of Cape Verde and Portugal. Journal of Psychology, 134, 503–514. doi:10.1080/00223980009598232.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal relationships in disorder (Vol. 3, pp. 31–56). London: Academic Press.

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R. A., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 250–264. doi:10.1177/1745691615568999.

Renshaw, P. D., & Brown, P. J. (1992). Loneliness in middle childhood. Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 545–547. doi:10.1080/00224545.1992.9924735.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 472–480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472.

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New Jersey, NJ: Erlbaum.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 78–107. doi:10.1086/209528.

Stickley, A., Koyanagi, A., Koposov, R., Schwab-Stone, M., & Ruchkin, V. (2014). Loneliness and health risk behaviours among Russian and U.S. adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 366–377. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-366.

Suedfeld, P. (1982). Aloneness as a healing experience. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 54–67). New York, NY: Wiley.

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Osterlind, S. J. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 486–492. doi:10.1080/17405629.2012.686740.

Van de Vijver, F., & Tanzer, N. K. (2004). Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview. European Review of Applied Psychology, 54, 119–135. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2003.12.004.

Van Staden, W. C., & Coetzee, K. (2010). Conceptual relations between loneliness and culture. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 524–529. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833f2ff9.

Wang, J. (2011). Subtypes of social withdrawal and adjustment in young Chinese adolescents. Paper presented at the National Science Foundation’s East Asian Pacific Summer Institute Conference, Beijing, China.

Wang, J. M. (2014). Preference for solitude, friendship support, and internalizing difficulties during early adolescence in the USA and China (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Maryland, College Park, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maes, M., Wang, J.M., Van den Noortgate, W. et al. Loneliness and Attitudes Toward Being Alone in Belgian and Chinese Adolescents: Examining Measurement Invariance. J Child Fam Stud 25, 1408–1415 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0336-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0336-y