Abstract

There is little research on the experiences of foster parent resource workers. Resource workers in foster care are the staff members who work most closely with foster parents. Foster parent resource workers in a large metropolitan area were asked the question: “What makes for a good relationship between a resource worker and a foster parent?”. The results were analyzed using concept mapping and resulted in eight concepts. Resource workers needed foster parents to follow through on expectations of their role through licensure and agency guidelines and agreements. They described the need for flexibility in their own role and actions. They focused described the need for common ground with foster parents, have respect for their knowledge and contributions, as well as to provide recognition and thanks. Resource workers needed to be attentive to foster parents, clear about their role and be good communicators. There was a great deal of overlap in the qualities of a good relationship from the perspectives of resource workers in the present study and the perspectives of foster parents as reflected in the existing literature. However, differences that appeared in the literature but not in the present study focused on the importance of resource provision by resource workers to foster parents, and in the results but not the literature focused on the evaluative aspects of resource workers’ role with foster parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Relationships with workers are key contributors to satisfaction and retention for foster parents (Rodger et al. 2006). The relationship with one’s worker has an impact on foster parents who might consider quitting and is a contributor for those who choose to stop. The quality of this relationship may also buffer against challenges faced in relationships with other individuals involved in the foster family such as the foster child’s worker and the birth family (Rosenwald and Bronstein 2008). There has been some research on the perspectives of foster parents on the contributors to a good relationship with staff but very little from the perspective of those workers who work most closely with them.

Resource worker is a title that is used in many North American jurisdictions to designate the professional staff member in an agency who works most closely with the foster parents themselves. This role is distinguished from the child welfare, child protection or children’s services worker who is assigned to the foster child (Esaki et al. 2012). However, this role is not clearly distinguished in the literature on fostering. Indeed, the research to date includes references to staff members, child welfare, Children’s Aid, child protection workers interchangeably when referring to the professional staff who work with foster parents. Given the importance of foster parents’ relationships with the workers involved, it is important to distinguish the contributions of those with different roles in the lives of foster parents to determine which functions as well as the nature of those relationships are most important for retention to slow the turnover of foster parent resource workers.

There is an emphasis in the literature on the importance for the relationship to serve a purpose and be productive. For this to happen, it is good for the worker and foster parents to feel like they can find some commonality (Farmer et al. 2010) in order to collaborate in the best interests of the foster child(ren) (Altshuler 2006). This collaboration is based on functional communication (Frey et al. 2008; i.e., not “just talking”), sharing information (Spielfogel et al. 2011) and ensuring that there is adherence to standards (Pavkov et al. 2010). Additionally, there is active involvement of foster parents in decision-making because their input is seen as valuable (Delgado and Pinto 2011).

There is a need for worker recognition and understanding about the foster parents’ values and traditions especially if they are different from the worker’s or agency’s orientation. There are indications that awareness of each other’s perspectives and appropriate engagement is viewed positively by foster parents (Bates et al. 2005) as is worker sensitivity, appropriateness and openness (Downs and James 2006) so that foster parents are not left not feeling judged for who they are as people (Riggs 2011). There is attention to the need for culturally responsive practice (Mindell et al. 2003) and recognition that this quality of relationship takes effort and time (Gerstenzang and Freundlich 2005). Evidence of the success is apparent in communication about sensitive topics (e.g. spirituality and religion; Furman et al. 2004).

A good relationship between workers and foster parents from the perspetive of foster parents leads to tangible outcomes for foster parents. Specifically, the worker provides services and supports to foster parents (Blakey et al. 2012), and the quality of support provided by the worker to the foster parent is of central improtance (Vanschoonlandt et al. 2014). Workers keep foster parents up to date with policy and system changes as they occur (Galehouse et al. 2010) and joint problem solve as well as help with direct intervention for foster children who are struggling (McLean 2012). Use of technology is also an important need in the relationship (e.g. texts and emails between foster parents and workers) as well as for the foster children (e.g. assistive technology for communication; Feil et al. 2012).

There is also attention in the literature to the need for workers and foster parents to have appropriate levels of responsibility for their roles. This is predicated on the importance of role clarity including understanding of who has what responsibilities to whom (Morrison et al. 2011), as well as recognition of lines of accountability for each role with cooperation and shared understanding between the foster parent and worker (Briggs 2009). This leads to appropriate expectations commensurate with responsibilities and their weight of (Rhodes et al. 2003) as well as coordination of service (Geenen and Powers 2007).

There is a need for continuity in the relationship. Consistency is key in terms of physical presence and “service” provided by the worker to the foster parent (Cushing and Greenblatt 2009). While the presence of a rationally oriented and dependable worker is seen positively (Robertson 2006) foster parents also want to be involved as a team member, and feel like they are understood (Rodger et al. 2006). Retention of resource workers with foster parents is also important to maintain the same worker with the family so that dependability can be established personally (Unrau and Wells 2005).

There is also literature that references expectations of foster parents by workers. There is attention to the importance of having confidence in self and each other (Finn and Kerman 2004) based on self-awareness of own values and perspectives on family issues and fostering (O’Brien 2012). Trusting this knowledge and experience is important (Saleh 2013) as a foundation for assertive and meaningful communication (MacGregor et al. 2006).

The importance of flexibility for both foster parents and workers is evident in the literature as a need for a good working relationship between them. There is a need for willingness to learn from each other (Jenson 2005) as well as listen to the children (Mitchell et al. 2010). This quality is evidenced by ability to influence, positively, each other (Slettebø 2013). It is necessary for the worker and foster parents to recognize the level of experience each brings to the role (Taylor and McQuillan 2014) as well as understanding of the preferences for different types of relationships such as detached, complementary and reciprocal between case workers and foster parents (Mosek 2004) and adjust accordingly to meet each where she or he as at. There is also the recognition that extention of kindness toward each other (Steen and Smith 2011) and inclusion of other community members as appropriate into the relationship (Haight et al. 2002) contribute positively.

Additionally, there is evidence in the literature of worker expectations of foster parents and foster parents expectations of workers that the relationship is proactive to head off potentially greater problems by taking action when there is the first indication of trouble or potential for it to develop (Khoo and Skoog 2014). This is aided by some advance strength in the relationship with agreement on some important issues (Holland and Gorey 2004) as well as a value of the other person (Mapp 2002) and ability to bridge differences of opinion as needed (Salas Martínez et al. 2014).

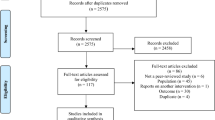

The studies referenced herein reflect a range of methods from large-scale representative samples utilizing measures with strong reliability and validity, to small-scale snowball samples with exploratory open-ended questions. Our purpose with the review was to include the range of possible research contributions on the topic to identify any that may have been overlooked before or underrepresented among foster parents, but possibly pronounced among resource workers. Our purpose with the present study was to identify, from the perspectives of foster parent resource workers, the characteristics of good relationships with foster parents. A sample of foster parent resource workers from a range of Children’s Aid agencies within a large metropolitan Canadian city were asked the question: “What makes for a good relationship between a resource worker and a foster parent?”. Responses were analyzed using a concept mapping procedure (Trochim 1989) to identify salient characteristics of a good relationship between those professional agency staff who work most closely with foster parents and the foster parents.

Method

Participants

Resource workers from a large metropolitan area who were attending a professional workshop were invited to participate in the study. There were a total of 68 individuals who participated in the study. The vast majority (88 %) was female. The average age of participants was 44 years and they had been working in the child welfare field for an average of 18 years. They were employed as a resource worker for an average of 8 years at the time of participation. About 1/3 had a graduate degree. The remainder had at least a college diploma and/or an undergraduate university degree.

Procedure

Individuals who provided written consent to participate were seated at small tables accommodating between 6 and 8 individuals and provided with several open-ended questions. Additionally, each was asked if she or he was interested in participating in the sorting task at a later date and those who were willing provided their contact information to the researchers.

Two of the researchers reviewed the responses provided on flipcharts by participants independently. All responses identified by either reviewer as being unclear or redundant were discussed and agreement was reached on necessary changes for clarity or removal from the final list. The final list of responses included 67 unique answers to the focal question.

Each participant who provided contact information for potential participation in the sorting task for the study was contacted by telephone by the researchers. All who remained interested provided consent to participate in the task. Each was provided with a complete set of cards. A different response was printed on each card. Cards were used to facilitate the grouping of responses into themes. Participants were provided with the instruction to group the cards in whatever way made sense to them and that they could have as many groups as they wanted. A total of 12 participants returned their sorts for analysis.

Measures

The focal question for the present study was: “What makes for a good relationship between a resource worker and a foster parent?”. They were asked to brainstorm as many unique responses as possible and record the responses verbatim on flipcharts.

Data Analyses

The Concept System (1987) was used to analyze sort data, however, statistical packages that offer multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis functions could be substituted. Two analyses were performed on the data. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) placed the results onto a 2-dimensional space where distance between the responses on the “point map” represented the frequency with which they were grouped together by participants.

As part of the MDS results, a bridging index was calculated for each response. The bridging index was a value between 0.00 and 1.00, which reflected the frequency with which each response “bridged” or grouped together by participants with other responses near to it on the map. Individual bridging indices above 0.75 were high and generally grouped with responses both in close proximity on the map as well as other areas of the map. Individual bridging indexes below 0.25 were low and generally grouped only with responses in close proximity on the map.

Cluster analysis used the MDS data to construct clusters. Hierarchical cluster analysis (Anderberg 1973; Everitt 1980) utilized the multidimensional scaling X–Y coordinate values for each point. According to Borgen and Barnett (1987), Ward’s minimum variance technique is a widely used agglomerative hierarchical technique and one of the most effective cluster analysis methods available for recovering underlying structure (Murtage and Legendre 2014). To minimize the variance with clusters at each stage of grouping, each response was initially treated as its own cluster. At each stage responses were joined by merging individual and grouped responses which resulted in the least increase in the within-groups sums of squares.

Researchers determined the most appropriate number of concepts for the final map based on qualitative and qualitative data. Qualitative data included the responses contacted within clusters. The “best” map was one that included clusters, which contained conceptually similar responses within each and conceptually distinct responses between. Quantitative data included the average bridging indices for the clusters. The “best” map was one where the clusters had moderate to low average bridging indices, which indicated that few responses in the clusters were grouped with responses in other clusters. Concept maps from 15 to 6 were reviewed before the decision was made to select the 8-cluster solution.

Researchers reviewed the 8-cluster concept map and responses within each cluster to inform the choice of labels. Within each cluster individual responses with the lowest individual bridging indices were most reflective of the central content of the cluster and these carried slightly more weight when labeling than responses with very high bridging indices.

Results

In the concept map below (see Fig. 1), each number represents one of the 67 unique responses provided by participants (see Table 1). The concepts represent the way that participants grouped the responses. In response to the question “What makes for a good relationship between a resource worker and a foster parent?”.

Foster Parent Compliance

Responses in this concept focused on the need that resource workers had for foster parents to follow through on expectations of their role through licensure and agency guidelines and agreements. The resource workers indicated that they found it helpful when foster parents obtained “education” related to their work as well as more specific areas related to their fostering practice, such as “child development education”. Having the foster parents working toward “achieving competencies” was positive, as well as “attending POC” (i.e. Plan of Care referred to a service planning meeting for a foster child) to discuss and make decisions with other team members. In addition, resource workers also described the need for foster parents to “provide training” to other foster parents, as relevant.

Resource Worker Flexibility

In this concept resource workers described the need for flexibility in their own role and actions. It was important for resource workers to remember that “we are a part of the team” including other professionals and the foster parents as well. The importance that members would “understand each others roles” was necessary, as well as to “share resources and ideas” about what works in foster care and for foster parents in particular. It was also noted that resource workers needed to put effort into “learning from foster parent” not only to understand that works in each home specifically as well as more general information about what is useful and needed by foster parents.

Compromise

Resource workers focused on the importance of finding common ground with foster parents when there were disagreements that arose. They were able to promote good resolutions with foster parents by “sharing information” and “dealing with mistakes as opportunities”. They also found it important to show “respect for varied values and cultural practices”. Resource workers also described the need to be reliable, so “don’t make promises can’t keep”.

Mutual Respect

An important quality for a good relationship with foster parents was to have respect for their knowledge and contributions in the system more broadly, as well as within their homes. For resource workers this meant taking “time to get to know them” and “give space” when needed. It was necessary that they “let them be heard” and were “validating what you hear” from foster parents. Once credibility and some level of trust was earned by the worker, they could have an easier time “saying difficult things” and offering “constructive confrontation” in ways that were “not minimizing impact of fostering on foster family” and reflected the genuine attitude of “value their work”. Resource workers also benefitted from “having a sense of foster parents and child’s needs” and “helping the foster parent draw on their own strengths” as well as “knowing when to protect foster parent” and “advocating on their behalf”.

Appreciation

The importance of having foster parents providing good care would need to be reflected through their recognition and thanks. This could be shown in different ways, such as through “coffee and treats at visits build the relationship”, or in “some cultures give hugs”. Resource workers also indicated that one would “give flowers” as a special recognition. The purpose of tokens of appreciation was for the “empowerment of foster parents” and their efforts with foster children, not as favoritism by the resource worker. Sound and realistic boundaries were important to maintain, and to do that they had to “know each others limitations”. The content of this concept was not evident in the literature.

Responsiveness

There were several responses that related to the need for resource workers to be attentive, interactive and, as necessary, take action to reflect their dedication to the foster parents’ roles. This meant “being interested and authentic” in their interactions with foster parents and to show a “genuine interest in their lives” while “appreciating their work”. Resource workers also needed to put effort into “being available” and “following up” as well as “responding to their needs in a timely fashion” despite their busy schedules. While some situations required them to “give hope” and be particularly involved, “knowing when to move on” was also important.

Role Clarity

Responses in this concept referred to the need for resource workers to have a sense of purpose for themselves and to promote a sense of purpose in their professional relationships with foster parents. While resource workers needed to display “flexibility”, spend time “listening” and just “being human” with foster parents, they were also to have “empathy without crossing boundaries”. While the relationship was a “partnership”, resource workers had the responsibility for “being professional” in their dealings, including “clarity and quality” interactions using well developed “communication skills” and “time management” as well as “paying attention to details”, with “clear expectations” and “having goals”. It was important for them to be “responsive rather than reactive”, share “acknowledgement” for their own or a foster parent’s behavior and employ good “conflict resolution skills” as needed. The ability to manage disagreements well was enhanced through recognition of some “shared values”, clear “boundaries” and ability for “seeing positive in negative”.

Good Communication

Resource workers described a range of qualities to reflect meaningful and effective communication between themselves and foster parents. In addition to the values of “honesty”, “integrity”, and “openness”, they noted that the communication would be “trustworthy”, reflect “consistency” and “predictability”, “sensitivity” as well as “transparency”. They noted that having a “sense of humor” was as important as being “non-judgmental” and “direct” at times in their dealings with foster parents.

Discussion

The literature that describes foster parents’ experiences was compared to the perspectives of workers in the present study concerning good relationships. Although there was considerable overlap between these perspectives, some areas of divergence were apparent.

There is a considerable literature base on the importance of involvement in decisions affecting their foster children (Delgado and Pinto 2011), which was clearly indicated by resource workers in the present study, as there was more of an evaluative emphasis that characterized their dealings with foster parents. Although their recognition of this evaluative function was noted by foster parents in the literature (Pavkov et al. 2010), resource workers in the present study saw this as an incremental process of improvement through education and training, both as a student and teacher to arrive at higher levels of competency.

There was clear evidence in the literature on the need for both worker and foster parent flexibility. The convergence centered on openness to learning from one another (Jenson 2005), and ability to contribute to what each other knows about foster children and what foster parents can do in the home that works with kids (Slettebø 2013). There was some difference in the range of stakeholders to be included in the relationship and “team” from the literature to include others from the community (Haight et al. 2002) as appropriate (e.g. Indigenous Elder) in the discussions between foster parents and resource workers.

There was considerable overlap between responses in this concept and the literature indicating that ability to find some common ground (Holland and Gorey 2004) and move forward following a disagreement (Salas Martínez et al. 2014) was favored as a quality of good relationships from both the perspectives of foster parents in the literature and workers in the present study. There was also attention in the literature to the need for openness to cultural differences and responsive practice that was sensitive to those differences (Mindell et al. 2003).

There was evidence in the literature (Bates et al. 2005) and by participants in the present study about the need to be able to perspective take. Recognition of the other’s perspective formed the basis of appreciation for the different roles (Finn and Kerman 2004) and their associated types (O’Brien 2012) as well as levels of competence and expertise (Saleh 2013). A secure basis (Mapp 2002) could create safe opportunities (Riggs 2011) for honest and direct communication (MacGregor et al. 2006) about potentially difficult topics (Gerstenzang and Freundlich 2005; Furman et al. 2004).

Workers in the study identified the need to be attentive and honestly interested in the contributions of foster parents and there was literature consistent with the idea. In order for there to be a good and functional connection with foster parents (Altshuler 2006), workers needed to communicate that they understood (Rodger et al. 2006) and were able to relate to them (Farmer et al. 2010). While there was attention in the literature to the need for workers to be proactive in their dealings with foster parents (Khoo and Skoog 2014) workers in the present study expressed this in the importance of being accessible.

There was a great deal of overlap between the responses in this concept and the literature beginning with the importance of having a sense of caring for each other as people (Steen and Smith 2011) as well as functional differences in the activities each undertook in their work (Morrison et al. 2011). It was evident that the relationship was a professional one with a particular purpose (Spielfogel et al. 2011) and desired outcome (Frey et al. 2008). It would be best characterized by clarity (Briggs 2009) and appropriate expectations (Rhodes et al. 2003) for the parties involved to coordinate their efforts (Geenen and Powers 2007).

There was a considerable overlap between the literature and participants experiences of these qualities of a good relationship to include consistency and predictability (Robertson 2006) as well as openness (Downs and James 2006). Resource workers indicated that they needed a personable presence with the foster parents. However, foster parents in the literature indicated the need for reliable (Unrau and Wells 2005) physical presence by the worker and concrete, useful outcome for their work together (Cushing and Greenblatt 2009).

Overall there was a great deal of overlap in the qualities of a good relationship from the perspectives of resource workers in the present study and the perspectives of foster parents as reflected in the existing literature. Both sources reinforced the need for participation in decision-making regarding the foster children in their care as well as working as a team and being open to the different kinds of experiences and qualifications each member brings. They also highlighted the need for sensitivity to cultural differences and working through difference of opinion and conflict when it arose. The strength of the relationship was tested by the ability to be responsive and honest with one another. In addition, the professional nature of the relationship, with clear roles and boundaries was noted by both participants in the present study and evident in the literature. These similarities indicate that there is a great deal of agreement between those in different roles about what qualities contribute to a positive relationship, and that there is the potential for existing research on foster parents’ perceptions of positive worker relationships to be accepting of workers’ views on the topic. In addition, these similarities provide a good starting point for finding ways to promote relationships between foster parents with other staff in the system, including resource workers specifically, as well as possibly other professionals, staff in the agency and child protection system personnel.

There were also differences between the results of the present study and the experiences of participants. The content that appeared in the fostering literature but not in the results of the present study focused on the importance of resource provision, and the content that appeared in the results of the present study but not in the fostering literature focused on the evaluative aspects of their role with foster parents. Because the literature reviewed was from the perspective of foster parents and the results from the present study reflected the perspectives of resource workers differences may indicate that there are potential qualitative differences in the qualities of a good relationship as perceived by these two groups.

Resource workers viewed a positive relationship in terms of foster parent compliance with standards and self-improvement efforts through education and training. They were also very cognizant of the benefits of positive reinforcement and recognition for the work that foster parents took on and accomplished. Foster parents, as evidenced in the literature, viewed a positive relationship in terms of tangible resources provided by the worker, including information, direct intervention (by the worker her or himself, or an outsider brought into assist, such as a cultural knowledge holder or other professional) and provision of equipment, such as technology for the parents and children to use.

It is suggested that while there are core commonalities in perceptions of good relationships between foster parents and resource workers, differences in focus could be implicated in conflicts and disagreements or problems that result in poor relationships between these groups. In the interest of promoting positive relationships, it would be worthwhile to test the weight of these qualities by ranking all of the common and specific by group and further, to determine which, if any, are central to major problems in foster care that lead to placement breakdown or foster parent attrition.

It would also be useful to explore the contributions of these relationship qualities to the selection of foster parents and resource workers into their roles and their self- and other-rated success in terms of longevity in their role, contributions to foster parent/resource worker and foster child wellbeing. The focus on wellness is a useful possibility for framing these relationship qualities in terms of the potential positive impact that the relationship between worker and parent has on the foster child and foster family in general.

In practice, these relationship qualities may be worth considering for the purpose of recruitment of workers and foster parents to identify preference and style that could be used for matching. The qualities identified may also be relevant for the development of foster parent and resource worker training on important areas related to the working relationship. Finally, development of interventions to promote positive relationships between resource workers and foster parents could be considered on the basis of qualities identified herein. For example, a discussion of these qualities could be considered in a remedial effort to restore or promote better functioning when challenges between worker and foster parent become strained. A major benefit of these qualities is that they are neither pathology oriented, negative or fixed in nature, opening possibilities for positive change.

Limitations

Limitations to the study include sample selection, participation rate in the sorting task and utility of results. Although the sample was obtained from a large-scale training event for resource workers across a metropolitan area, some staff did not attend, and of those who did attend, some did not participate. It is not possible to know how many resource workers staff the agencies within the catchment area, nor how many registered, attended and chose not to participate in the study. The other limitation concerns the modest participation in the sorting task. Although all participants were invited to sort, the task was time-consuming and while many initially agreed, upon follow up and after sending out the materials, 12 remained. It is not known how these 12 were similar or different from the others who did not participate in sorting. The results of this methodology do not provide evidence of relative strength of the relationship qualities or their frequency of occurrence.

References

Altshuler, S. J. (2006). (One hundred and) ten years later, students in foster care still need our help! School Social Work Journal, 31(SpecIss), 79–93.

Anderberg, M. R. (1973). Cluster analysis for applications. New York: Academic Press.

Bates, L., Baird, D., Johnson, D. J., Lee, R. E., Luster, T., & Rehagen, C. (2005). Sudanese refugee youth in foster care: The “lost boys” in America. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 84(5), 631–648.

Blakey, J. M., Leathers, S. J., Lawler, M., Washington, T., Natschke, C., Strand, T., & Walton, Q. (2012). A review of how states are addressing placement stability. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(2), 369–378.

Borgen, F. H., & Barnett, D. C. (1987). Applying cluster analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 34, 456–468.

Briggs, H. E. (2009). The fusion of culture and science: Challenges and controversies of cultural competency and evidence-based practice with an African American family advocacy network. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(11), 1172–1179.

Cushing, G., & Greenblatt, S. B. (2009). Vulnerability to foster care drift after the termination of parental rights. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(6), 694–704.

Delgado, P., & Pinto, V. S. (2011). Criteria for the selection of foster families and monitoring of placements. Comparative study of the application of the Casey Foster Applicant Inventory-Applicant Version (CFAI-A). Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 1031–1038.

Downs, A. C., & James, S. E. (2006). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual foster parents: Strengths and challenges for the child welfare system. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 85(2), 281–298.

Esaki, N., Ahn, H., & Gregory, G. (2012). Factors associated with foster parents’ perceptions of agency effectiveness in preparing them for their role. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6(5), 678–695.

Everitt, B. (1980). Cluster analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Halstead Press.

Farmer, E. M. Z., Burns, B. J., Wagner, H. R., Murray, M., & Southerland, D. G. (2010). Enhancing “usual practice” treatment foster care: Findings from a randomized trial on improving youths’ outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 61(6), 555–561.

Feil, E. G., Sprengelmeyer, P. G., Davis, B., & Chamberlain, P. (2012). Development and testing of a multimedia Internet-based system for fidelity and monitoring of multidimensional treatment foster care. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(5), 239–248.

Finn, J., & Kerman, B. (2004). Internet risks for foster families online. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 22(4), 21–38.

Frey, L., Cushing, G., Freundlich, M., & Brenner, E. (2008). Achieving permanency for youth in foster care: Assessing and strengthening emotional security. Child & Family Social Work, 13(2), 218–226.

Furman, L. D., Benson, P. W., Grimwood, C., & Canda, E. (2004). Religion and spirituality in social work education and direct practice at the millennium: A survey of UK social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 34(6), 767–792.

Galehouse, P., Herrick, C., & Raphel, S. (2010). Position statement on foster care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(1), 36–39.

Geenen, S., & Powers, L. E. (2007). “Tomorrow is another problem”: The experiences of youth in foster care during their transition into adulthood. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(8), 1085–1101.

Gerstenzang, S., & Freundlich, M. (2005). A critical assessment of concurrent planning in New York state. Adoption Quarterly, 8(4), 1–22.

Haight, W. L., Black, J. E., Mangelsdorf, S., Giorgio, G., Tata, L., Schoppe, S. J., & Szewczyk, M. (2002). Making visits better: The perspectives of parents, foster parents, and child welfare workers. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 81(2), 173–202.

Holland, P., & Gorey, K. M. (2004). Historical, developmental, and behavioral factors associated with foster care challenges. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21(2), 117–135.

Jenson, J. M. (2005). Editorial: Reflections on natural disasters and traumatic events. Social Work Research, 29(4), 195–198.

Khoo, E., & Skoog, V. (2014). The road to placement breakdown: Foster parents’ experiences of the events surrounding the unexpected ending of a child’s placement in their care. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 13(2), 255–269.

MacGregor, T. E., Rodger, S., Cummings, A. L., & Leschied, A. W. (2006). The needs of foster parents: A qualitative study of motivation, support, and retention. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 5(3), 351–368.

Mapp, S. C. (2002). A framework for family visiting for children in long-term foster care. Families in Society, 83(2), 175–182.

McLean, S. (2012). Barriers to collaboration on behalf of children with challenging behaviours: A large qualitative study of five constituent groups. Child & Family Social Work, 17(4), 478–486.

Mindell, R., de Haymes, M. V., & Francisco, D. (2003). A culturally responsive practice model for urban indian child welfare services. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 82(2), 201–217.

Mitchell, M. B., Kuczynski, L., Tubbs, C. Y., & Ross, C. (2010). We care about care: Advice by children in care for children in care, foster parents and child welfare workers about the transition into foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 15(2), 176–185.

Morrison, J., Mishna, F., Cook, C., & Aitken, G. (2011). Access visits: Perceptions of child protection workers, foster parents and children who are Crown wards. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1476–1482.

Mosek, A. (2004). Relations in foster care. Journal of Social Work, 4(3), 323–343.

Murtage, F., & Legendre, P. (2014). Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: Which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? Journal of Classification, 31, 274–295.

O’Brien, V. (2012). The benefits and challenges of kinship care. Child Care in Practice, 18(2), 127–146.

Pavkov, T. W., Hug, R. W., Lourie, I. S., & Negash, S. (2010). Service process and quality in therapeutic foster care: An exploratory study of one county system. Journal of Social Service Research, 36(3), 174–187.

Rhodes, K. W., Orme, J. G., & McSurdy, M. (2003). Foster parents’ role performance responsibilities: Perceptions of foster mothers, fathers, and workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 25(12), 935–964.

Riggs, D. W. (2011). Australian lesbian and gay foster carers negotiating the child protection system: Strengths and challenges. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 8(3), 215–226.

Robertson, A. S. (2006). Including parents, foster parents and parenting caregivers in the assessments and interventions of young children placed in the foster care system. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(2), 180–192.

Rodger, S., Cummings, A., & Leschied, A. W. (2006). Who is caring for our most vulnerable children? The motivation to foster in child welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(10), 1129–1142.

Rosenwald, M., & Bronstein, L. (2008). Foster parents speak: Preferred characteristics of foster children and experiences in the role of foster parent. Journal of Family Social Work, 11(3), 287–302.

Salas Martínez, M. D., Fuentes, M. J., Bernedo, I. M., & García-Martín, M. A. (2014). Contact visits between foster children and their birth family: The views of foster children, foster parents and social workers. Child & Family Social Work, 1–11. doi:10.1111/cfs.12163.

Saleh, M. F. (2013). Child welfare professionals’ experiences in engaging fathers in services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 30(2), 119–137.

Slettebø, T. (2013). Partnership with parents of children in care: A study of collective user participation in child protection services. British Journal of Social Work, 43(3), 579–595.

Spielfogel, J. E., Leathers, S. J., Christian, E., & McMeel, L. S. (2011). Parent management training, relationships with agency staff, and child mental health: Urban foster parents’ perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2366–2374.

Steen, J. A., & Smith, K. S. (2011). Foster parent perspectives of privatization policy and the privatized system. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1483–1488.

Taylor, B. J., & McQuillan, K. (2014). Perspectives of foster parents and social workers on foster placement disruption. Child Care in Practice, 20(2), 232–249.

Trochim, W. M. K. (1989). An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12, 1–16.

Unrau, Y. A., & Wells, M. A. (2005). Patterns of foster care service delivery. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(5), 511–531.

Vanschoonlandt, F., Van Holen, F., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., & Andries, C. (2014). Flemish foster mothers’ perceptions of support needs regarding difficult behaviors of their foster child and their own parental approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31(1), 71–86.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of this research through a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We would also like to thank the foster parent resource workers who participated for their time and expertise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, J.D., Anderson, L. & Rodgers, J. Resource Workers’ Relationships with Foster Parents. J Child Fam Stud 25, 336–344 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0204-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0204-9