Abstract

Objective

To determine factors associated with a positive male patient experience (PMPE) at fertility clinics among male patients.

Design: Cross-sectional study

Setting: Not applicable

Patients: Male respondents to the FertilityIQ questionnaire (www.fertilityiq.com) reviewing the first or only US clinic visited between June 2015 and August 2020.

Interventions: None

Main outcome measures: PMPE was defined as a score of 9 or 10 out of 10 to the question, “Would you recommend this fertility clinic to a best friend?”. Examined predictors included demographics, payment details, infertility diagnoses, treatment, and outcomes, physician traits, and clinic operations and resources. Multiple imputation was used for missing variables and logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for factors associated with PMPE.

Results

Of the 657 men included, 60.9% reported a PMPE. Men who felt their doctor was trustworthy (aOR 5.01, 95% CI 0.97–25.93), set realistic expectations (aOR 2.73, 95% CI 1.10–6.80), and was responsive to setbacks (aOR 2.43, 95% CI 1.14–5.18) were more likely to report PMPE. Those who achieved pregnancy after treatment were more likely to report PMPE; however, this was no longer significant on multivariate analysis (aOR 1.30, 95% CI 0.68–2.47). Clinic-related factors, including ease of scheduling appointments (aOR 4.03, 95% CI 1.63–9.97) and availability of same-day appointments (aOR 4.93, 95% CI 1.75–13.86), were associated with PMPE on both univariate and multivariate analysis. LGBTQ respondents were more likely to report PMPE, whereas men with a college degree or higher were less likely to report PMPE; however, sexual orientation (aOR 3.09, 95% CI 0.86–11.06) and higher educational level (aOR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–1.10) were not associated with PMPE on multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Physician characteristics and clinic characteristics indicative of well-run administration were the most highly predictive of PMPE. By identifying factors that are associated with a PMPE, clinics may be able to optimize the patient experience and improve the quality of infertility care that they provide for both men and women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infertility is present in approximately 10% of all couples and is partly or completely attributable to a male factor in approximately 50% of cases [1,2,3]. However, male factor infertility is often overlooked by the literature, media, and healthcare providers [1, 4]. Although male factor infertility has a substantial impact on physical and emotional health and quality of life for male patients, these measures have been studied far less in men compared to women [3,4,5]. Additionally, though men feel the loss associated with a failure to conceive, resources available for infertile men are both limited and underutilized [4].

Patient experience is known to be a key quality indicator in healthcare and is associated with improved patient safety and clinical efficacy [6]. However, there is limited data regarding the male partner experience in infertility clinics [5]. Available studies have either been performed outside the USA, sampled a disproportionately lower number of men, or been limited by relatively small sample sizes overall [7,8,9]. Our group was among the first to evaluate factors associated with a positive patient experience at US fertility clinics for female patients [10]. The study utilized data from FertilityIQ, a web-based platform created in 2015 which connects patients to information about infertility treatment and infertility clinics across the country and simultaneously collects data from patients about their care experiences through structured questionnaires.

The present manuscript utilizes FertilityIQ data to evaluate the male partner experience in US infertility clinics. We hypothesized that male patients would be more likely to report positive male patient experience (PMPE) if they felt that their physician was empathetic, trustworthy, and involved them in decision-making, as well as if they experienced shorter wait times, positive interactions with ancillary staff, and more robust clinic administration. Prior literature has demonstrated that male patients consistently report higher overall satisfaction with healthcare than female patients, across a variety of clinical settings [11,12,13,14]. A good provider-patient relationship, in particular, was more positively associated with patient satisfaction for male patients than female patients [11, 12]. Therefore, we additionally hypothesized that PMPE rates would be higher in male patients compared to female patients, and more provider-related characteristics would be associated with PMPE for male patients compared to female patients.

Methods

Data source and study cohort

The FertilityIQ website (www.FertilityIQ.com) is a publicly available resource designed to link individuals or couples interested in pursuing fertility treatment with relevant informational materials and nearby clinics. In addition to resources, the website features a voluntary 115 item questionnaire (https://www.fertilityiq.com/survey-intro) for individuals pursuing fertility treatment to report type of treatment(s) received, review their doctors and fertility clinics, and differentiate personal preferences regarding the infertility treatment experience. The questionnaire requires respondents to answer one question at a time, along with a minority of required questions that cannot be skipped. Most of the questions require respondents to choose from multiple pre-generated choices, whereas some allow free-text responses. Please refer to Shandley et al. (2020) for in-depth details regarding methodology and the survey instruments [10]. The FertilityIQ questionnaire database was chosen for this study because it is currently the only source collecting nationwide data about patient satisfaction in fertility clinics in the USA. The data is sourced from fertility clinics across the country and includes respondents from all 50 states. The data was obtained without cost directly from FertilityIQ.

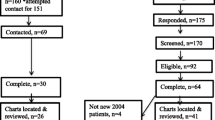

Approximately 3% of the respondents to the questionnaire were self-reported as male. We analyzed de-identified data from men who completed the FertilityIQ questionnaire between June 2015 to August 2020 and who reviewed their first or only clinic visit. The study was approved by our institutional IRB.

Outcomes

A positive male patient experience (PMPE) was defined as a score of 9/10 or 10/10 to the question, “Would you recommend this fertility clinic to a best friend?” We examined demographic factors, including age, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, and LGBTQ status. Other predictors examined included payment details, infertility diagnoses and treatment, physician traits, and clinic operations and resources.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the population of FertilityIQ respondents, comparing those reporting PMPE versus those reporting a non-positive patient experience (NPE) at a fertility clinic. Multiple imputations were used for missing variables that were missing 5% of observations. Analysis of these variables was performed to ensure they met criteria for missing at random before performing imputation. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) for factors associated with PMPE. A multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate adjusted ORs (aOR). Three variables were forced into the model a priori: male factor infertility, use of donor sperm, and pregnancy resulting from treatment. Additional variables were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model based on causal considerations. Change in estimate criterion was applied to reduce the number of variables in the model [15, 16]; variables were removed one at a time to explore how exclusion of each variable affected the remaining variables. Variables were included in the model if they altered the aOR’s of the other variables by > 10%.

Results

Descriptive statistics

There were 1001 survey responses from individuals who identified as male. Of those, 58 were duplicate responses and were excluded. Each survey response had a unique identifier, which was cross-referenced with respondents’ IP addresses in order to identify and remove duplicates. Of the remaining responses, 282 reviewed more than one clinic; for these, the review of the first clinic was included in the analysis. Finally, four survey responses completed by individuals who went to a clinic outside of the USA were excluded. The remaining total of 657 male respondents were included in the final analysis.

Of the 657 men included in the study, 400 patients (60.9%) reported a PMPE. The mean age at questionnaire was 36.9 +/− 6.8 years, and the mean age at time of fertility treatment was 35.2 +/− 6.7 years (Table 1).

Patient factors

Patient demographics and treatment characteristics stratified by PMPE are summarized in Table 1, and unadjusted odds ratios for the association of each factor with PMPE are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Men who were older at time of fertility treatment (35 years or older compared to under 35 years old) were less likely to report a PMPE (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.49–0.92).

Men with a college degree or higher were less likely to report a PMPE than those who did not have a college degree (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.37–0.80). Among men who ultimately contributed to a pregnancy versus those who did not, those with a college education or higher were more likely to report a PMPE.

Region of residence, residing in a state with mandated insurance coverage, and having insurance coverage of any portion of treatment all did not significantly impact patients reporting a positive or negative experience. Employment status and annual income also did not appear to impact reported PMPE.

Patients who self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) were more likely to report a PMPE (OR 2.75, 95% CI 1.36–5.57) than patients who did not identify as LGBTQ.

Diagnosis and treatment characteristics

There was no significant association between patients reporting PMPE and their underlying diagnosis of infertility, including female factor infertility, male factor infertility, or unexplained infertility. However, those who reported a pregnancy as a result of treatment were more likely to report a PMPE (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.69–3.50).

Physician characteristics

Men who felt their doctor was a good communicator (OR 30.21, 95% CI 15.38–59.35), was trustworthy (OR 77.73, 95% CI 21.31–241.46), and showed compassion (OR 26.9, 95% CI 14.05–51.55) were more likely to have a PMPE than those who felt negatively about their patient-physician relationship. The men who felt that they received individualized attention from their provider were more likely to report PMPE (OR 22.27, 95% CI 12.57–39.45).

Clinic characteristics

Physician and clinic characteristics, stratified by PMPE, are summarized in Table 2.

A clinic with well-run administration, determined by characteristics such as “no wait time to speak to a provider” (OR 16.74, 95% CI 9.27–30.23), greater ease of seeing a physician that day (OR 12.63, 95% CI 6.75–23.63), and a direct line of communication to a physician (OR 3.6, 95% CI 2.08–6.23), was all significantly associated with PMPE.

Multivariate analysis

In the multivariate analysis (Table 3), physician characteristics, including trustworthiness (aOR 5.01, 95% CI 0.97–25.93), ability to set realistic expectations at the end of each appointment (aOR 2.73, 95% CI 1.10–6.80), and responsiveness to setbacks with treatment adjustments (aOR 2.43, 95% CI 1.14–5.18) were associated with PMPE after adjusting for potential confounders. Similarly, several clinic characteristics were still associated with PMPE, including ease of scheduling an appointment (aOR 4.03, 95% CI 1.63–9.97), ability to see a physician on the same day (aOR 4.93, 95% CI 1.75–13.86), and satisfaction with the billing department (aOR 4.98, 95% CI 2.74–9.04). Availability of genetic counseling was also found to be associated with PMPE (aOR 2.59, 95% CI 1.32–5.10). Of note, achieving pregnancy, having a college degree or higher, and self-reported LGBTQ status were no longer significantly associated with PMPE. Additionally, neither the use of donor sperm nor a diagnosis of male factor infertility was associated with a PMPE.

Discussion

Overall, among the male respondents included in this study, 61% reported PMPE, and 39% reported NPE. This rate was similar to the rate reported by women in Shandley et al. of 63% [10]. As hypothesized and demonstrated in prior studies, some of the strongest predictors of PMPE for males were related to physician characteristics, including physicians who were rated as being good communicators, appearing trustworthy and compassionate, and setting accurate expectations. These associations were found to persist even after controlling for potential confounding variables, such as demographic characteristics including age, race, region, education status, and income level. Other strong predictors of PMPE included highly rated clinic characteristics—namely, clinics with no wait times to speak to a doctor or nurse, availability of same-day appointments, and direct lines of communication with providers. A significant proportion of male respondents reported NPE, consistent with NPE rates reported by female respondents. This highlights the utility of the present study in analyzing factors related to PMPE to guide future intervention to maximize PMPE for both male and female patients.

PMPE was found to be most strongly associated with multiple physician characteristics in our analysis. Patient satisfaction has previously been associated with achieving pregnancy and a good patient-physician relationship, whereas longer wait times, communication errors, and poor relationships with healthcare personnel were the main reasons for dissatisfaction [9, 10, 17, 18]. In this study, patients reported higher PMPE when they received individualized attention from providers, when providers set appropriate expectations for treatment, and when their treatment course was changed in response to setbacks. These measures may indicate a greater understanding of patients’ situations, and responsiveness to setbacks may make patients feel as their concerns are being heard and managed appropriately. Previous studies have extensively investigated the patient-provider relationship for female patients receiving infertility care. One previous European study showed that less than half of women were satisfied with the infertility treatment they received [9]. Another showed that 10 to 20% of women did not feel that their provider involved them in decision-making or was interested in them as a person [17]. Importantly, though pregnancy rates are generally deemed important for couples in choosing a fertility clinic, it has been shown that couples were willing to choose a clinic with a lower pregnancy rate if its providers were rated as more “patient-centered” [17]. This emphasizes the importance of the patient-physician relationship in infertility care, and it is crucial to make providers aware of these findings before any improvement in the patient experience is achievable. Physician characteristics should be an initial target for intervention in obtaining PMPE, particularly because these improvements can be made without significant costly infrastructural change [19, 20].

The characteristics of clinic administration that were associated with PMPE likely represent a longer-term target for intervention in infertility care. These findings are also supported by prior literature, which found that the ability to easily contact and schedule appointments with providers, even outside of business hours, was associated with higher patient satisfaction. Several studies have proposed the use of patient portals and online scheduling tools to seamlessly connect patients with their providers [21, 22]. Though the use of these tools should be balanced with the risk of placing additional burden on providers in some infertility clinics, they may be applied to many clinics to enhance the patient experience with infertility care nationally. Further, similar to the Shandley et al.’s study, availability of genetic counseling and satisfaction with the billing department were found to be one of the strongest predictors on multivariate analysis, even after controlling for confounders related to patients’ socioeconomic level, including income level, education level, and insurance coverage [10]. Therefore, it is likely that patients viewed the availability of ancillary services, such as genetic counseling, and interactions with the billing department, as components of the clinic administration, which further underlines the importance of seeking a more robust clinic administration.

Though prior literature has shown different factors associated with PMPE in male patients in other clinical settings [11,12,13,14], our findings align with the prior report by Shandley et al. [10], indicating that similar physician-related and clinic-related factors are associated with PMPE for both male and female patients receiving fertility care. Notably, in contrast to the Shandley et al.’s study, on multivariate analysis, PMPE in the male population was not associated with achievement of pregnancy, patient education level, and provision of certain ancillary services, including availability of acupuncture.

Achievement of pregnancy was one of the few non-modifiable factors found to be associated with PMPE on univariate analysis. However, this was surprisingly not found on multivariate analysis, unlike the results from the Shandley et al.’s study [10]. Further, modifiable factors, including provider and patient characteristics, are stronger predictors of PMPE than achievement of pregnancy for male patients. This highlights these factors as fruitful targets for intervention to improve male patient satisfaction, even in a setting where the primary outcome of pregnancy may be difficult for providers to predict and control, and these interventions may be even more effective at improving patient satisfaction for male patients than female patients. Other factors that we predicted to affect PMPE based on the results from Shandley et al., including male factor infertility and use of donor sperm, were also initially included in the model. However, like for achievement of pregnancy, the exclusion of these factors from the model did not significantly affect the aORs of the other factors in the model (data not shown). Further research should include larger samples of male respondents to better quantify the magnitude of the association between achievement of pregnancy, male factor infertility, and use of donor sperm with PMPE in males.

National rates of LGBTQ status reported in polls range widely, with recent estimates ranging between 4 and 8% [23]. In the present study, 8.2% of the included male respondents identified as LGBTQ. This rate is higher than the rate of self-reported LGBTQ status (4.7%) in Shandley et al. [10]. The percentages of LGBTQ individuals who identify as male versus female, as well as the rates at which self-identified male LGBTQ patients, seek fertility care, compared to the rates at which self-identified female LGBTQ patients do so, has not been well-studied. There is a need for future analysis to better understand the behaviors and needs of LGBTQ individuals seeking fertility care. Further, LGBTQ status was hypothesized to be negatively associated with PMPE because it is well-established that the population is more likely to experience discrimination and face systemic barriers when interacting with the healthcare system, leading to lower overall satisfaction with healthcare encounters [24, 25]. Interestingly, LGBTQ status was found to be positively associated with PMPE in our univariate analysis. It is possible that, in contrast to other clinical settings, fertility clinics may provide a more inclusive and non-biased environment for LGBTQ patients, where they are encouraged to candidly discuss their sexual preferences and concerns related to their sexual and gender orientations [26]. Still, this association was not noted on multivariate analysis, so further research to examine LGBTQ self-identification status and the patient experience in fertility clinics using other databases is warranted.

PMPE was associated with lower education level on univariate analysis, but was not found to be on multivariate analysis. Prior studies have found patients with high education levels are less likely to report PMPE, which has been proposed to be a result of the higher expectations of care from this population [27, 28]. However, this relationship was not found in this study after controlling for other potential confounding factors that are often associated with education level, including employment status and insurance coverage, which may be related to the highly variable costs and coverage for infertility services across different insurance policies.

Strengths

This is the first study to analyze the experience at fertility clinics for a national sample of male patients and uses the largest national database reporting patient-centric data regarding fertility care to do so. In previous studies, men who had received an infertility diagnosis were found to experience loss of masculine identity and feelings of insignificance [29, 30]. In addition, many men reported feeling excluded or dismissed from the process of infertility treatment because women were seen as being placed at the epicenter of infertility treatment. Men also felt that they were not as supported as their female counterparts throughout the process [29,30,31,32]. Further, a recent qualitative study found that, in interviews with couples undergoing fertility treatment, the emphasis on the female partner throughout diagnosis and treatment could make some women feel as though their body was “abnormal” while leading to missed infertility diagnoses in the male partners [33]. Hence, the results of this study are particularly important to highlight in the context of these previous findings and the lack of any large-scale analyses of this issue within the USA.

Limitations

It is important to note that although the FertilityIQ questionnaire is publicly available for all patients, it is completed by more women than men, so our analysis involves a smaller sample size when compared to prior large-scale studies that evaluate the female experience with fertility clinics. The prior study by Shandley et al.’s study included over 7000 respondents, whereas the present study includes just over 1000 respondents after expanding the study period by 2 years [10]. The discrepancy in sample size limits direct comparability of the results of the two studies. Further, it is difficult to assess whether the study population accurately represents the national population of male patients seeking fertility treatment. In the Shandley et al.’s study, the study group was compared to the population receiving in-vitro fertilization (IVF) nationwide as listed in the 2016 Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) National Summary Report from the CDC, and the two populations were found to reflect one another in overall characteristics [10]. However, the ART national summary reports do not detail patient characteristics by gender, so it remains difficult to accurately determine if the study group in the present study reflects the national male population receiving IVF treatment. Despite only 3% of respondents to the FertilityIQ questionnaire being male, FertilityIQ still provides the largest dataset of this kind nationwide in terms of absolute numbers of male respondents. However, the limited proportion of male respondents demonstrates the lack of emphasis on the experience of the male partner in this space. The FertilityIQ questionnaire was not designed specifically for research purposes. As such, it includes questions that are difficult to interpret for the purposes of research analyses. Completed questionnaires also included missing data, which required imputation prior to statistical analysis. Finally, this study draws several comparisons between the male and female population using the results from Shandley et al. [10]. Because both of these studies are drawn from the same questionnaire, the same survey and response biases affect both studies. This may lead to a higher number of identified similarities in the male and female patient experience than in reality.

Finally, because of the size of the study population, FertilityIQ was unable to standardize the point during treatment at which each fertility clinic requested respondents to fill out the survey. Therefore, some surveys may have been completed while participants had ongoing treatment, whereas others may have been completed after pregnancy was achieved. As part of the survey, participants reported whether they received their desired results during their care, and those who were still undergoing treatment were given the option to respond “Too early to say”. As Table 1 demonstrates, 20.8% of respondents who reported PMPE provide this response, whereas 17.6% of respondents who did not report PMPE did so. The similarity between these two proportions demonstrates that though these respondents may have still been undergoing treatment, it did not significantly affect their patient experience. Furthermore, our ultimate goal as providers is to provide a PMPE for patients at all stages of care regardless of eventual pregnancy outcome. Though the finding that PMPE is associated with pregnancy outcome is unsurprising, because we cannot always guarantee pregnancy at the conclusion of treatment, we should seek to have PMPE reported in all surveys irrespective of time of survey relative to fertility treatment.

Conclusion

Physician characteristics and ease of access to a physician or nurse were the most highly predictive of PMPE reported by male patients. By identifying factors that are associated with a PMPE, clinics may be able to optimize the patient experience and improve the quality of infertility care that they provide for both men and women.

Data sharing statement

N/A

Trial registration

N/A

References

Mehta A, Nangia A, Dupree J, Smith J. Limitations and barriers in access to care for male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(5):1128–37.

Smith J, Walsh T, Shindel A, et al. Sexual, marital, and social impact of a man's perceived infertility diagnosis. J Sex Med. 2009;6(9):2505–15.

Hammarberg K, Baker H, Fisher J. Men's experiences of infertility and infertility treatment 5 years after diagnosis of male factor infertility: a retrospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(11):2815–20.

Petok W. Infertility counseling (or the lack thereof) of the forgotten male partner. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(2):260–6.

Mehta A. Qualitative research in male infertility. Urol Clin North Am. 2020;47(2):205–10.

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:1.

Dancet E, Nelen W, Sermeus W, Leeuw LD, Kremer J, D'Hooghe T. The patients' perspective on fertility care: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(5):467–87.

Lass A, Brinsden P. How do patients choose private in vitro fertilization treatment? A customer survey in a tertiary fertility center in the United Kingdom. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(5):893–7.

Malin M, Hemmink E, Räikkönen O, Sivho S, Perala M. What do women want? Women's experiences of infertility treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(1):123–33.

Shandley L, Hipp H, Anderson-Bialis J, Boulet S, McKenzie L, Kawass J. Patient-centered care: factors associated with reporting a positive experience at United States fertility clinics. Assisted Reprod. 2020;113(4):797–810.

Okunrintemi V, Valero-Elizondo J, Patrick B, et al. Gender differences in patient-reported outcomes among adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24)

Otani K, Buchanan P, Desai S, Herrmann P. Different combining process between male and female patients to reach their overall satisfaction. J Patient Exp. 2016;3(4):145–50.

Bener A, Ghuloum S. Gender difference on patients' satisfaction and expectation towards mental health care. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16(3):285–91.

Chen P, Tolpadi A, Elliott M, et al. Gender differences in patients' experience of care in the emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):676–9.

Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–36.

Weng H, Hsueh Y, Messam L, Hertz-Picciotto I. Methods of covariate selection: directed acyclic graphs and the change-in-estimate procedure. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1182–90.

Mourad S, Nelen W, Akkermans R, et al. Determinants of patients' experiences and satisfaction with fertility care. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1254–60.

Iv E, Nelen W, Tepe E, Ev L, Verhaak C, Kremer J. Weaknesses, strengths and needs in fertility care according to patients. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1)

Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino M, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101.

Fenton J, Jerant A, Bertakis K, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405–11.

Carini E, Villani L, Pezzullo A, et al. The impact of digital patient portals on health outcomes, system efficiency, and patient attitudes: updated systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9)

Kinney A, Sankaranarayanan B. Effects of patient portal use on patient satisfaction: survey and partial least squares analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(8)

Jones J. LGBT Identification in U.S. Ticks Up to 7.1%. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx

Mulé N, Ross L, Deeprose B, et al. Promoting LGBT health and wellbeing through inclusive policy development. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8(18)

Colpitts E, Gahagan J. The utility of resilience as a conceptual framework for understanding and measuring LGBTQ health. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(60)

Hudson K, Bruce-Miller V. Nonclinical best practices for creating LGBTQ-inclusive care environments: A scoping review of gray literature. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2022;35(2):218–40.

Leyser-Whalen O, Bombach B, Mahmoud S, Greil A. From generalist to specialist: a qualitative study of the perceptions of infertility patients. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2021;14:204–15.

Quintana J, González N, Bilbao A, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;102(6)

Sylvest R, Fürbringer J, Schmidt L. Infertile men’s needs and assessment of fertility care. Ups J Med Sci. 2016;121(4):276–82.

Arya S, Dibb B. The experience of infertility treatment: the male perspective. Hum Fertil. 2016;19(4):242–8.

Iv E, Dancet E, Koolman K, et al. Physicians underestimate the importance of patient-centredness to patients: a discrete choice experiment in fertility care. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(3):584–93.

Zaake D, Kayiira A, Namagembe I. Perceptions, expectations and challenges among men during in vitro fertilization treatment in a low resource setting: a qualitative study. Fertil Res Pract. 2019;5(6)

Fisher J, Hammarberg K. Psychological and social aspects of infertility in men: an overview of the evidence and implications for psychologically informed clinical care and future research. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(1):121–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J.A.B. and D.A.B. have financial relationships with FertilityIQ, which served as the source of data for this article. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Attestation statement

• The subjects in this trial have not concomitantly been involved in other randomized trials.

• Data regarding any of the subjects in the study has not been previously published unless specified.

• Data will be made available to the editors of the journal for review or a query upon request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Siddharth Marthi and Lisa M. Shandley shared the first authorship.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Marthi, S., Shandley, L.M., Ismaeel, N. et al. Factors associated with a positive experience at US fertility clinics: the male partner perspective. J Assist Reprod Genet 40, 1317–1328 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-023-02848-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-023-02848-2