Abstract

To determine the effectiveness of current ethical teaching and to suggest ways to reform the current ethical curriculum in light of students’ perspectives and experiences. Students of Dow Medical College were selected for this cross-sectional study conducted between the year 2020 till 2023. The sample size was 387, calculated by OpenEpi. A questionnaire consisting of 17 close-ended questions was used to collect data from participants selected via stratified random sampling. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part included the demographics. While the second contained 15 questions designed to assess the participants’ current teaching of ethics and effective ways to further improve it. The data obtained were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 26. Out of the 376 students who gave consent, the majority of the respondents (64.6%) encountered situations where they felt that their current teaching of ethics was insufficient and (54%) believed that the current teaching of ethics could be improved and made further effective. Practical sessions, PBLs (problem-based learning), case analysis, and ward visits were some of the ways the participants believed could help improve the teaching of medical ethics. Most students (92.8%) agreed that external factors like burnout and excessive workload have an impact on medical professionals’ ethical practices. In light of our study, a refined curriculum with a focus on ethical teaching must be established, with input from students to ensure that the medical students have the necessary expertise to manage an ethical dilemma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals are often looked up to as the pillars of society. The significance of their attitude toward patients cannot be emphasized enough and doctors themselves are obligated to not only treat their patients’ pathology but also to be aware of the patient's condition and treat them well. Healthcare professionals hold significant obligations to the patients under their care that they do not only treat their patients' diseases but also treat them as a whole in the most effective way, and medical ethics teaches them how to make the right choices of conduct considering all circumstances. In the field of medicine, in addition to clinical expertise, the ethical conduct of a healthcare professional plays a significant role in enhancing the patient-physician relationship. This has been shown to enhance patient satisfaction and outcomes in the long term (Gabel, 2011; Nandi, 2000).

Prior to becoming physicians, medical students are subjected to an extensive curriculum covering many of the core subjects, supplemented with intense hours of hospital rotations. However, in developing countries such as Pakistan, one aspect of the curriculum remains comparatively neglected — the teaching of medical ethics (Jafarey, 2003).

Substantiating the statements mentioned above, a study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan brought to light alarming findings regarding medical ethics (Jafarey, 2003). A vast majority of junior doctors felt that their teaching of medical ethics had been unsatisfactory, while more than half of them observed that their senior's medical practice was unethical, and a substantial number of them perceived that the majority of the patients suffered due to the unethical practices of the senior medical staff.

Ethics has been a salient aspect of medical practice that is overlooked as a skill in the quest to develop accomplished doctors, particularly in government sector medical colleges in Pakistan. Although it is widely considered a part of the medical curriculum, the teaching is inadequate and the application in the field by professionals is even more scarce. The emphasis on the vitality of ethics is because it is the foundation of a good patient-doctor relationship. Mutual respect, trust, and regard in this relationship will lead to satisfaction and fruitful results for the patient and this is the ultimate success for a doctor and clinical medicine at large (Ruberton et al., 2016). This cannot be ensured without the doctor having a sound understanding of ethics.

Proper training in ethics for students who will become future doctors is therefore necessary. A study conducted in Saudia Arabia shows a stark difference in the attitudes and practices of healthcare workers who received formal training in ethics, compared to the ones who did not (Althobaiti et al., 2021). The study showed that the participants with a duration of medical practice of < 20 years had a significant higher mean attitude scores compared with other participants (0.01). Participants who reported having previous training in bioethics had a significant higher mean attitude scores compared with those had had not (P = < 0.001). The insufficient incorporation of ethics in the practice of medical professionals in Pakistan is a grave issue. The paucity of literature discussing this situation has prompted us to further investigate what is causing the lack of implementation of ethics (Althobaiti et al., 2021).

In this paper, we intend to gain students' insights regarding their medical school’s teaching of ethics, which will prove to be beneficial in establishing a curriculum well-suited to cover all aspects of medical practice.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Dow Medical College between 2020 and 2023. Participants included medical students, between the years of the first and final year of MBBS. The sample size of this study was 387, calculated by OpenEpi. Participants were selected using stratified random sampling techniques. Inclusion criteria included medical students from Dow Medical College, students from all other institutes and those who refused to consent were excluded from the study to minimize the chances of error because of the disparity seen in the teachings, hospital environment, resources, and patient influx, between different universities of Karachi.

A self-administered questionnaire consisting of 17 close-ended questions was used to collect data. The questionnaire was designed by the authors of the article. The first part of the questionnaire consisted of demographic information including sex and year of study. Email IDs were asked to ensure no forgery was done in data collection. The second part of the questionnaire included 15 questions that were developed to attain participants’ experiences about medical ethics, their major source of learning, current barriers to learning ethics, and their ideas about improving ethics. No other personal information was asked, ensuring participants’ privacy. The questionnaire was validated through a pilot study. Consent was attained from all participants.

Informed consent was sought from all participants and confidentiality of the identities was maintained. Details about the objectives of the study were explained to the participants. The pattern and time required were conveyed to the respondents before the survey-based study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institutional review board (IRB), Dow University of Health Sciences.

All the data obtained were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 26. Descriptive statistics of socio-demographic variables were presented as mean, frequency, and percentages. Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) Kruskal–Wallis H test was used as a non-parametric measure to assess the relationship between variables. A p-value of 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

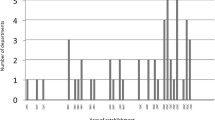

A total of 387 medical students from Dow Medical College were invited to participate in the study. Eleven students failed to provide consent. As a result, data obtained from 376 students was used for analysis. Making the overall response rate 97.15%. Participants who filled the questionnaire on hard copy were taken verbal consent,where there were summarized about the study and its scope as well, and those who filled online, were taken written consent to proceed with the questionnaire. Sampling was random, no credentials about the participants were asked, and their filled questionnaires were opened only at the time of result analysis. About three quarter (73.9%) of our participants were female and the remaining one-quarter (26.1%) were male. 135 students were in pre-clinical years of study, i.e., 1–2 year of medical school and 241 students were in their clinical years, i.e., 3–5 year of medical school, as depicted in Fig. 1.

More than two-thirds (79.3%) of the respondents felt that the ethical behavior of senior doctors and hospital staff plays a significant role in shaping students’ perceptions of ethical practices. Most students (92.8) agreed that external factors like burnout and excessive workload impact medical professionals’ ethical practices. Refer to Table 1.

Regarding whom the respondents will approach when facing an ethical dilemma, friends, colleagues, HOD (Head of Department) and supervisors were the most popular choices. Internet and Ethical Committee were the least popular choices as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Numerous students stated that their practice of ethics can be assessed by evaluations of the patients, faculty observation, and scenario-based learning. 22.1% of the students disagreed that non-medical staff should evaluate those students. Most students agreed that guidelines and ethical consultancy could tackle ethical dilemmas. Using books as a reference remained an unpopular choice. Refer to Table 2.

When asked if the students would benefit from help from a clinical psychologist, students who have experienced ethical issues firsthand agreed, as they thought consultation with a psychologist would be of help (χ2 = 13.288, p = 0.000). Students who believed they had experienced ethical erosion over the years (Refer to Table 3) agreed that burnout has played its part in it. On the other hand, those who didn't experience ethical erosion didn’t think that burnout contributed to unethical behavior (χ2 = 13.103, p = 0.001).

Lastly, regarding strategies to improve ethical practices amongst medical professionals, practical sessions, PBLs (problem-based learning), case analysis, and ward visits were popular choices. Teaching using videos and medical talk shows remained an unpopular choice as demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Students perception about ethical ethings in their institute is highighted in Table 3. Majority of the participants think that the ethical tecahings in their institute needs improvement (54%), and it can cause drastic change in the ethical standings of future doctors and their interactions with patients (49.7%). This can be improved by mentorship programs from the experts from the field, as well as targeted workshops on ethics and psychology can be beneficial.

A majority (65.2%) of the respondents had witnessed a physician interacting with a patient derogatorily. This furthur lead to the majority of the participants feeling ethical erosion with time during their hopsital rotations. Refer to Table 4.

Discussion

In today’s fast-paced world of medicine, we have come a long way in terms of scientific advancements. This has, however, come at a heavy cost; a compromise in basic ethical practice owing to a high-stress increasingly competitive environment. An exemplary doctor-patient relationship that is based on 4 key elements; mutual knowledge, trust, loyalty, and regard (Ruberton et al., 2016), is not only necessary for patient satisfaction but ensures effective communication, which eventually leads to better patient outcomes (Ridd et al., 2009). More than half of the students in our study agreed that we can improve ethical teachings in our institution (Table 3). Multiple studies have shown a decrease in empathy in medical students over years (Stratta et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2007; 2012), which is contrary to our finding that 58% of clinical year students believe that they have not experienced such erosion of ethics. Ethical teaching must commence at a grassroots level. Students’ input is invaluable when designing curricula for ethical studies. Our study found that the respondents suggested practical learning in the form of PBLs, ward visits, etc. should be incorporated into their ethical teaching. Compared to the overwhelming response to using ethical consultancy and guidelines as an approach to ethical dilemmas, fewer people wanted to use books. A study conducted by Ozgonul et al. also showed that team-based learning for ethics in medical education is a better alternative to lectures (Ozgonul & Alimoglu, 2019). Robert LW et al. also concluded in a study that ethical education should be based on the real-time experiences of physicians and sessions should be focused on enhancing critical thinking amongst students, rather than a focus on memorizing learn the theoretical instructions (Roberts et al., 2005). Although the students did not like the idea of using medical talk shows as a source of learning, perhaps medical podcasts can be a good source of remote learning, but we found no literature discussing the use of podcasts specifically for teaching medical ethics. However, there have been multiple articles exploring the potential role of podcasts in revolutionizing remote-accessible medical education (Cho et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2022).

A staggering 65% of our respondents reported having witnessed a physician interacting with a patient derogatorily. Students look up to the medical staff and eventually follow in their footsteps as they step into the hospital as doctors. Their personal experience would leave a bigger footprint than guidelines, as Imad et al. highlighted that 58% of the house officers did not even read the PMDC ethical guidelines (Aleem et al., 2021). Hence, safe-ethical practice must start from the top as the faculty proves to be role models for upcoming doctors, and accountability measures are put in place. Doctors, nurses, and other medical staff should be all routinely assessed to ensure that ethical guidelines are being adhered to. In addition, patient feedback is another invaluable tool to gauge the behavior of hospital personnel. We must explore new approaches to medical ethics by using simulations and faculty observations. We found students will find their friends, potential colleagues, and supervisors a safer place to consult in need as compared to their HODs. Building a stronger support group within respective wards can help future doctors share their experiences and ethical dilemmas they faced with other colleagues to have a healthy discussion, which can serve as a learning environment for future dealings. We also reported that most students attributed ethical malpractice to poor working conditions. While it warrants further exploration, a lack of privacy and a resource-limited setting may be contributing factors to the lack of application of ethical knowledge.

A study found that as much as 92% of the residents felt burnout due to their workload, and 20% fell onto the depression scale due to the increased work stress. This led to greater chances of malpractice, as depressed doctors were 6 times more likely to make medical errors than non-depressed ones (Ozgonul & Alimoglu, 2019). New ways should be devised to distribute the workload of healthcare staff to reduce the individual burden which ultimately might help reduce stress and burnout. Furthermore, doctors with burnout were likely to report at least one major incidence of suboptimal patient care and medical malpractice in one month, which was lower among their non-burnout counterparts (Silverman et al., 2013). A decrease in burn-out and eventually malpractice can be ensured by building stronger support groups within wards where workers can share their experiences and ethical dilemmas they face with other colleagues to have a healthy discussion, which can serve as a learning environment for future dealings. Moreover, effectively balancing workloads among colleagues and reducing extended work hours for doctors and healthcare workers can help in reducing fatigue among doctors as well (Martins et al., 2021).

Strict guidelines need to be developed within the wards to strengthen ethical consultancy to ensure workers' adherence to them, as most of the students also agreed to an Ethical Guideline in wards, to help combat ethical dilemmas among workers. Lack of role models and accountability within workspaces can lead to increased incidences of malpractice.

Conclusion

In light of our findings, an ethically and morally sound environment is pertinent to the holistic development of medical students and has a significant impact on their trajectory as physicians. A refined curriculum with a focus on ethical teaching must therefore be established, with input from students.

Limitations

Our project adopted a single-centered approach, incorporating only government sector universities and excluding the private sector. Our study was limited to medical students’ perspective only, if the audience of this research was expanded to practicing doctors, the study would have been more well-rounded. Future studies can be done which are more inclusive. To counter the response bias in this study, interview-based qualitative studies can be considered to obtain more detailed responses from the participants for the study.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Aleem, I., Zaidi, TafazzulHyder, Usman, G., Siddiq, H., Usman, T., Baloch, Z. H., & Abbas, K. (2021). Practice of medical ethics among house officers at tertiary care hospital in karachi. Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS), 16(3), 3.

Althobaiti, M. H., Alkhaldi, L. H., Alotaibi, W. D., Alshreef, M. N., Alkhaldi, A. H., Alshreef, N. F., Alzahrani, N. N., & Atalla, A. A. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of medical ethics among health practitioners in Taif government, KSA. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(4), 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2212_20

Chen, D., Lew, R., Hershman, W., & Orlander, J. (2007). A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(10), 1434–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x

Chen, D. C., Kirshenbaum, D. S., Yan, J., Kirshenbaum, E., & Aseltine, R. H. (2012). Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Medical Teacher, 34(4), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.644600

Cho, D., Cosimini, M., & Espinoza, J. (2017). Podcasting in medical education: A review of the literature. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 29(4), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2017.69

Gabel, S. (2011). Ethics and values in clinical practice: whom do they help? Mayo Clinic proceedings, 86(5), 421–424. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0781

Jafarey, A. M. (2003). Bioethics and medical education. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 53(6), 210–214.

Kelly, J. M., Perseghin, A., Dow, A. W., Trivedi, S. P., Rodman, A., & Berk, J. (2022). Learning through listening: a scoping review of podcast use in medical education. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 97(7), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004565

Martins, V., Santos, C., Bataglia, P., & Duarte, I. (2021). The teaching of ethics and the moral competence of medical and nursing students. Health Care Analysis: HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy, 29(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-020-00401-1

Nandi, P. L. (2000). Ethical aspects of clinical practice. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960), 135(1), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.135.1.22

Ozgonul, L., & Alimoglu, M. K. (2019). Comparison of lecture and team-based learning in medical ethics education. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017731916

Ridd, M., Shaw, A., Lewis, G., & Salisbury, C. (2009). The patient-doctor relationship: A synthesis of the qualitative literature on patients’ perspectives. The British Journal of General Practice: THe Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 59(561), e116–e133. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X420248

Roberts, L. W., Warner, T. D., Hammond, K. A., Geppert, C. M., & Heinrich, T. (2005). Becoming a good doctor: Perceived need for ethics training focused on practical and professional development topics. Academic Psychiatry : THe Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 29(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.301

Ruberton, P. M., Huynh, H. P., Miller, T. A., Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2016). The relationship between physician humility, physician-patient communication, and patient health. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(7), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.012

Silverman, H. J., Dagenais, J., Gordon-Lipkin, E., Caputo, L., Christian, M. W., Maidment, B. W., 3rd., Binstock, A., Oyalowo, A., & Moni, M. (2013). Perceived comfort level of medical students and residents in handling clinical ethics issues. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(1), 55–58.

Stratta, E. C., Riding, D. M., & Baker, P. (2016). Ethical erosion in newly qualified doctors: Perceptions of empathy decline. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 286–292. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.57b8.48e4

Syed, S. S., John, A., & Hussain, S. (1996). Attitudes and perceptions of current ethical practices. PakIstan Journal of Medical Ethics, 1, 5–6.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors took an equal part in performing the literature search, drafting the questionnaire, and the data collection of this study. Rida Saleem, Syeda Zainab Fatima, Roha Shafaut, Asfa Maqbool, and Faiza Zakaria drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. Saba Zaheer and Musfirah Danyal Barry contributed to the editing and revisions of the initial and subsequent drafts for incorporating important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. Haris Jawaid played an essential role in the data analysis and formulation of the results of this study. This study was completed under the supervision and guidance of Dr. Fauzia Imtiaz. She contributed to getting the IRB approval from DUHS- Research Committee. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from Ethics Committee of the institutional review board (IRB), (Authors will indicate the name of the granting institution after the acceptance of the manuscript).

Competing Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saleem, R., Fatima, S.Z., Shafaut, R. et al. To Determine the Effectiveness of Current Ethical Teachings in Medical Students and Ways to Reform this Aspect. J Acad Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09550-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09550-7