Abstract

The problem of academic dishonesty in general and exam cheating in particular, has been ubiquitous in schools, colleges, and universities around the world. This paper reports on the findings from teachers’ and students’ experiences and perceptions of exam cheating at Nepali schools, colleges, and universities. In so doing, the paper highlights the challenges of maintaining academic integrity in Nepali education systems. Based on qualitative research design, the study data were collected by employing semi-structured interviews with the teachers and the students. Findings from the study indicated that over-emphasized value given to marks/grades and the nature of exam questions among others were the predominant factors. Our findings contribute to the practical understanding that academic institutions in Nepal have largely failed to communicate the value of academic honesty and integrity to the students of all levels of education despite the increasing prevalence of exam cheating. Therefore, exam cheating requires urgent attention from academic institutions, educators, and education leaders to educate students about the long-term educational and social values of academic honesty and integrity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research highlights that the fundamental obligation of students and faculties in educational institutions is to uphold academic integrity and exhibit high standards of performance (Mensah et al., 2018). However, the issue of academic dishonesty remains prevalent among students from school through higher education systems throughout the world (Chiang et al., 2022; Kasler et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022). The widespread prevalence of academic dishonesty such as exam cheating, plagiarism, contract cheating, and other forms of assessment fraud, for example, has long emerged as a serious threat to academic integrity within educational institutions (Kasler et al., 2023; Roe, 2022). Although exam cheating is not a new phenomenon, it has become a matter of particular concern among education and psychology scholars over the past few decades (Anderman & Koenka, 2017; Błachnio, 2019). While extensive research has been conducted on exam cheating, most of the studies have examined this phenomenon in the contexts of developed countries such as the US (McCabe et al., 2001; Whitley & Kost, 1999), Canada (Awosoga et al., 2021; Hughes & McCabe, 2006; Jurdi et al., 2012), the UK (Bacon et al., 2020), and Australia (Busch & Bilgin, 2014) among others. Also, comparisons of this phenomenon among these countries and of these countries with other countries have been more frequent (Awosoga et al., 2021; Bernardi et al., 2012; Lupton & Chaqman, 2002; Preiss et al., 2013). Moreover, most of the studies previously published have particularly focused on either graduate students (Bucciol et al., 2020), college students (Awosoga et al., 2021), or school students (Dejene, 2021), whereas relatively few studies have explored cheating behaviors from school through university students. On top of that, in developing countries like Nepal, where exam cheating has long become commonplace in examinations of all levels (Gautam, 2017; The Himalayan Times, 2017), it has rarely become a matter of academic discussion until now. Studies indicate that cheating in an educational context can result in far-reaching academic and social consequences such as loss of learning opportunities, unjustified credentials, low levels of knowledge, production of incompetent graduates, and lack of confidence in the whole education systems (Chala, 2021; Miller et al., 2017).

Given the issues raised in the international context, it is possible that there is a multiplicity of issues which relate to exam cheating in Nepal. These issues have not yet been explored and need attention, something which this study addresses. With this rationale in mind, this study answers two major questions:

-

How do teachers and students conceptualize exam cheating practices in Nepal?

-

In teachers and students’ experience, what factors have contributed to exam cheating practices in schools, colleges, and universities of Nepal, and in what ways such challenges can be deterred?

We believe this paper will both add value to the international literature on academic dishonesty and fill the paucity of literature on Nepali students’ exam cheating practices from schools through higher education. In doing so, our study primarily aims to highlight the information regarding how educational leaders, teachers, and students need to respond to the burgeoning culture of exam cheating practices to ensure academic honesty and integrity in Nepali education systems.

Country Context

As a resolution of a decade-long (1996–2006) armed conflict, Nepal transitioned from constitutional monarchy to federalism. As a result, Nepal promulgated new constitution in 2015 and embarked on its journey towards federal restructuring (Rankin et al., 2018). The three-layered governments, provisioned in that rearrangement, are entrusted with concurrent responsibilities to coordinate in public issues, including educational affairs (Daly et al., 2020). However, the process of reorganizing educational structures, including higher education, by federalizing “educational institutions as per the essence of the constitution of Nepal” is still on its way (Baral, 2016, p. 45).

School-level education, in Nepal, covers from Grade I to Grade XII (5-16-year-old children) and education after Grade XII has now been defined as higher education (Ministry of Education, 2016). There are twelve universities, and five medical academies offering higher education in Nepal (UGC, 2022b). In the year 2020-21, 1,437 higher education institutions enrolled a total of 466,828 students (167,107 students in constituent, 167,840 students in private, and 131,881 students in community campuses) in different academic programs (UGC, 2022a). These institutions run various programs on annual and semester systems at Bachelor’s, Master’s, MPhil, and Ph.D. levels and evaluate their students as per their rules and regulations.

While assessing school level students, terminal examinations are conducted in their respective schools and final examinations are conducted at local and provincial levels. But the final examinations of Grade XII are administered by National Education Board. In higher education, both internal and final examinations are in practice, but they are executed differently in different universities and subjects with differences in the weightage of internal and final examinations. Mostly, exam offices run these examinations with the physical presence of the students in the designated exam centers. But during the Covid era, some universities postponed their exams for a while, some administered online exams, and some institutions conducted exams in their home centers.

The Nepali education system has some explicit problems. Researchers’ calls for the need of strengthening it indicates the existing complications that surround it. Baral (2021, p. 137), for instance, indicated “centralized institutional arrangements” of higher education institutions as a hindrance, and Nepali higher education is not fully directed toward contemporary global needs of HE owing to the dearth of both timely updated courses and skilled teachers. The pass rate of students is also not satisfactory. For instance, in 2020-21, only 41% students from Tribhuvan University, which had the highest number of enrollment (347,269 students), passed their respective exams (UGC, 2022b). But there are some privately funded institutions that consider “pass with high percentage as the indicator of quality education” (Baral, 2016, p. 42) and always focus to make their students pass with good marks/grades.

Amidst these complications, University Grants Commission, in 2020-21, endorsed multiple policy documents aiming to fulfill the promises of higher education to produce skilled human resources (UGC, 2022a).

Review of Literature

Academic cheating is broadly linked to any dishonest act that tricks, defrauds, and fools the instructors/teachers with the sole aim of yielding academic advantages to those involved (Davis et al., 2009). Researchers maintain that such unethical activities are predominantly aimed at evading the assessment process to gain an unfair advantage to better results which are often inaccurate and misleading (Cizek & Wollack, 2016; Srikanth & Asmatulu, 2014). Although scholars hold diverse views regarding academic dishonesty in general, exam cheating, in particular, is often associated with unethical means and fraudulent actions that examinees take before, during, or after examinations have been administered. Scholars, for instance, have demonstrated that while potential opportunities for examinees, in terms of when and how they cheat, may be wide-ranging and vast, cheating can mainly occur at any point of the three major stages of the examination process—development, administration, and scoring (Cizek & Wollack, 2016). Available literature has particularly linked exam cheating—whether in the offline or online environment—to an act of using unauthorized materials and information by potential examinees while examinations are being administered (Dawson, 2021; Krienert et al., 2022). Traditional method of exam cheating broadly entails, but not limited to, the use of cheat sheets, crib notes, notebooks, etc., by examinees to write one’s exams; copying from peers’ answer sheets in the exam hall; collaborating with other examinees or staff to obtain and use unauthorized resources; gaining help from outsiders; and having access to question papers or contents before the examinations (Chala, 2021). Further, with the rapid expansion of digital technologies, technology-based learning, and e-assessment methods, new modes of cheating techniques have emerged over the years (Dawson, 2021). More specifically, examinees can engage in e-cheating by accessing unauthorized materials and information through the use of digital technologies such as computers, cell phones, Internet, earpieces, smart watches, and social media among others, whether in the offline or online examination environment (Chirumamilla et al., 2020; Dawson, 2021; Krienert et al., 2022; Noorbehbahani et al., 2022).

A plethora of research has shown that exam cheating has always existed, whereas a large proportion of students from all levels of education around the world continue to report their engagement in exam cheating, at least once in their academic careers (Bacon et al., 2020; Bernardi et al., 2012; Busch & Bilgin, 2014; Chala, 2021; Davis et al., 2009; Kobayashi & Fukushima, 2012; Krienert et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2012). For example, research conducted between 2002 and 2010 by McCabe et al. (2012) and other follow-up studies conducted by International Center for Academic Integrity (2020) indicated that 60% of university students and 95% of high school students respectively admitted of cheating using either traditional or technology-driven method. In a recent study, Chala (2021) found a huge prevalence of exam cheating among students, with the rate of 81% of undergraduate students reporting their involvement in exam cheating at least once. Other recent studies, which investigated students’ cheating practices on online examination amid the COVID-19 pandemic, have also replicated prior findings although more studies are required to measure the extent of impacts COVID-19 had on academic integrity (Jenkins et al., 2022).

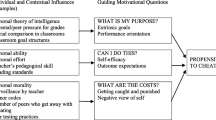

Although there is no simple answer to what contributes to students’ exam cheating, studies have reported multifaceted causes that induce this phenomenon within educational institutions. ‘Cheating in school: What we know and what we can do?’ by Davis et al. (2009) is perhaps one of the most comprehensive studies investigating students’ cheating behaviors in all segments of education. Based on their study, Davis et al. (2009) have identified situational factors, dispositional factors, and changes in attitudes, values, and morals of students, and other external factors (pressure for grades, size of classes, nature of exams among others) as the major determinants of exam cheating practices. When it comes to dispositional factors, they, nonetheless, argue that students’ morality and ethical development, academic motivation, naturalized perception of peers’ cheating, perceived risks of cheating, and sense of accountability have significant impacts on cheating behaviors. Other studies have highlighted that exam cheating has its preoccupation with fear of failure and elevated stress and pressure for achievement or competition for better grades (Anderman & Koenka, 2017; Bujaki et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2013). Given the fact that better grades are often the strongest predictor of one’s admission into desired colleges or universities, career prospects, and academic status, students are often motivated to cheat (Henry et al., 2021). Further, in their multivariate analysis of a national sample of 2,503 college students, Yu et al. (2017) indicated that several individual factors such as gender, socioeconomic status, academic year, lack of self-control, purposes in life, college experience, involvement in extracurricular activities, employment, lack of preparation for exams, perceptions and attitudes toward cheating behaviors, perception of faculty’s responses against cheating, and cheating environment had significant impacts on students’ cheating. Moreover, research suggests that perception of peers’ cheating behaviors, honour codes, and personality traits are other influential factors in students’ frequency and the likelihood of exam cheating (Malesky et al., 2022; McCabe et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2022). Other studies indicate that perceived opportunity and absence of punishment can equally contribute to students’ cheating (Dejene, 2021; Walters & Morgan, 2019). Moreover, based on their review of 58 publications on online cheating practices published between 2010 and 2021, Noorbehbahani et al. (2022) identified four major factors (teacher-related, institutional, internal, and environmental factors) that could lead to students’ exam cheating behaviors. In addition, numerous studies have highlighted that the advancement of digital technologies, rapid expansion of e-assessment, availability of search engines, and accessibility of information as significant factors affecting students’ exam cheating behaviors (Kelley & Dooley, 2014; Krienert et al., 2022; Noorbehbahani et al., 2022; Srikanth & Asmatulu, 2014).

A plethora of research has outlined students’ perceptions of exam cheating. However, empirical studies focused on faculties’ attitudes are relatively scanty. Available studies show that although faculty and students often perceive exam cheating as a serious form of academic misconduct, they respond to exam cheating practices in diverse ways, many of which seem to undermine the value of academic integrity (Catacutan, 2021; Chirikov et al., 2020; MacLeod & Eaton, 2020). For example, MacLeod and Eaton’s (2020) study investigated that although university teachers expressed serious concerns about increased prevalence of academic dishonesty, including exam cheating, the majority of them showed their unwillingness to consistently report such malpractices to the concerned authorities due to their feeling of unsupportive and burdensome administrative process. Further, in their study Burgason et al. (2019) found that a large number of university students (71%) taking distance learning course did not regard looking at their notes as cheating during online exams; rather the examinees viewed it as a trivial act. Further, in a survey conducted among university undergraduates, Henry et al. (2021) reported that, although students were found to have anti-cheating perceptions, they justified their cheating as a means to attain scholarships and meet parents’ expectations. Similarly, in another study conducted among undergraduate students, Chala (2021) figured out that although the majority of the students (81%) perceived most cheating behaviors as forms of serious academic misconduct, they were found to have continuously engaged in exam cheating. More interestingly, 91–93% of the students in the same study admitted to having whispered answers to others or allowed others to copy their answers during examinations at least once, rationalizing these behaviors as moderate acts.

It becomes clear that academic institutions are facing increasing challenges regarding how to mitigate students’ pervasive cheating behaviors. Based on empirical evidences that explain students’ motivation, rationalization, and methods of cheating, scholars have recommended that faculty and institutions adopt a wide range of strategies to reduce the probability of students’ involvement in such actions, whether in offline or online environment. These strategies entail but are not entirely limited to, warning and counselling about the consequences of cheating (Asokan et al., 2013; Corrigan-Gibbs et al., 2015; Fontaine et al., 2020); having regular discussions with students regarding virtues of academic integrity and its long-term social benefits (Miller et al., 2017; Tabsh et al., 2019; Vučković et al., 2020); breaking friendship chain or maintaining proper spacing between examinees and careful invigilation (Topîrceanu, 2017); and adopting deterrent-based approaches, such as the imposition of harsh penalties (Chirikov et al., 2020). Other studies, albeit entirely focused on online examination contexts, have suggested adopting “cheat-resistant” exam design such as designing open-book exams or knowledge-based questions/essays that require examinees to demonstrate high-order thinking and critical abilities (Nguyen et al., 2020). Furthermore, Nugroho et al. (2023) have proposed the implementation of an effective proctoring system within learning management systems to verify the users, lockdown browsers, and automatically counter students’ potential cheating behaviors.

It seems that most of the strategies have been predominantly premised either on distrust of students or efforts of educational institutions and educators to foster character improvement and moral obligations in students (Miller, 2013). Nonetheless, educating students that academic honesty and integrity are the utmost priority of education and enhancing moral obligation have been often regarded as the most effective deterrents to all the forms of academic dishonesty, including exam cheating (Birks et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2017).

Methodology

This study based on a qualitative research approach employed phenomenological interpretative design (Cohen et al., 2017) intending to examine teachers’ and students’ experiences and perceptions of exam cheating practices in Nepali educational institutions. Owing to the nature of the study which aimed to investigate unethical practices in examinations, the researchers initially faced challenges in finding potential voluntary respondents for this research project. Using the researchers’ three colleagues, who were serving as teachers in different universities, as gatekeepers (De Laine, 2000), voluntary respondents were sought at schools, colleges, and universities in Nepal. The researchers’ colleagues (none of them were involved as respondents in this study) assisted in locating three respondents (teachers). Following this, other respondents were recruited in the study adopting a snowball sampling technique (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981), through which the early respondents assisted in recruiting their friends/students as potential research respondents. Altogether, 6 full-time and 6 part-time university teachers (many of whom informed that they were also teaching in schools and colleges at the time of data collection) and 18 students (3 each from two high schools, two colleges/constituent campuses, and two universities) showed their willingness to take part in this research project as respondents. Following ethical guidelines, informed consent was obtained from all the respondents after we had emailed them an information sheet and consent form through emails or communicated on Facebook Messenger. To maintain the research ethics, confidentiality, and anonymity of the respondents and education institutions as suggested by Cohen et al. (2017), respondents names were anonymised as detailed in Table 1.

After we received informed consent from all the respondents involved in this study, an interview schedule was used to interview them individually on videoconferencing tools such as Zoom, Google Meet, and Facebook Messenger based on what suited them. We employed semi-structured interviews (half an hour to an hour) to elicit the study data from the respondents. Consulting existing literature on academic dishonesty in general and exam cheating in particular, 14 representative open-ended interview questions were initially designed for both teachers and students. In this situation, Galletta’s (2013) ideas were useful to guide the researchers in designing primary questions and framing sub-questions and probes both to generate unstructured responses from each respondent and create deeper discussion with them on the study topic. The interviews were conducted on multiple occasions and audio-recorded on smartphones and laptops for later transcription and analysis. The audio-recorded data were then translated, transcribed, systematically coded, and collated to identify emergent themes, and critically analyzed by following inductive coding schemes based on a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Results

Experiences, Attitudes, and Perceived Consequences of Exam Cheating

All the respondents involved in this study reported that exam cheating was a common phenomenon they had routinely witnessed in schools, colleges, and universities. Also, both teachers’ and students’ reported information revealed that while exam cheating was prevalent in all the segments of education, students’ propensity to cheat was relatively higher in the examinations of final years/terms of all the academic levels—SEE (previously SLC), Grade XII, Semester End Examinations of Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. When asked about cheating experiences, although the majority of teachers and students showed their willingness to report their peers/colleagues/students’ cheating behaviors, they initially seemed reluctant to disclose their engagement in exam cheating. Nonetheless, all the students and the teachers (except one teacher) confessed that they had cheated at least once on examinations. Surprisingly, the majority of teachers and students admitted that they had cheated either in their SLC/SEE or + 2 examinations for the first time. For many students, exam cheating was likely to continue throughout higher education. The data also indicated that cheating behavior patterns between the teachers and students differed significantly. For example:

I was writing my SLC exam, and we had been asked to draw and label a four-stroke petrol engine. I did not intend to cheat, but what happened was that I noticed a sheet of paper with the required diagram being circulated from underneath our desks. I quickly looked into it to confirm if my labeling was okay. (T5)

I cheated in school and college, and even if I get a chance in future exams, won’t be an exception […] You know everybody cheats if their luck favors them. If you know the guards, you can also ask them sometime. I remember while I was in + 2, teachers told us the answers at the end of the exam […]. (S9)

Both T5 and S9’s expressions represent the voice of many other teachers and students who indicated that cheating had become an epidemic in educational institutions. Also, S9’s voice emulated the lived- experience of many other students who regarded the opportunity to cheat as luck, which was often ensured in coordination with peers, invigilators, and even teachers. Further, all the respondents reported that they had witnessed an intense form of cheating behaviors such as mass cheating on examinations of all levels in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, S8 commented:

All the exams were held in home centers during the pandemic. Everybody cheated and even invigilators facilitated cheating. You know, those who had failed their + 2 exam multiple times in the past, passed during this time. Even some who had quit their study also filled out the form and passed their exams.

S8’s voice reflected the idea that COVID-19 had not only adversely affected learning activities but also hampered the evaluation process in which mass cheating was only the viable option for educational institutions, teachers, and students to cover the loss of learning opportunities and ensure faked academic improvement. This indicated that the teachers were unable to properly diagnose students’ real abilities and largely failed to address the shortcomings of many students who had continuously failed in the previous examinations.

Although all the students admitted their engagement in diverse ways of cheating behaviors (which we have detailed in the following section) both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, their understanding of what constitutes cheating, to a greater extent, seemed limited. Interestingly, although all the students perceived cheating behaviors as dishonest activities, they viewed using crib notes, cheat sheets, and technological devices only as serious forms of cheating.

However, it should be noted that all the respondents perceived exam cheating as a deviant act that could largely question both the credibility of exam systems and the academic spirit of educational institutions, teachers, and students. In their view, although exam cheating could result in unfair evaluation and reduced educational engagement, which would, in the long run, deteriorate the learning abilities and skills of students, it was still routine practice in their schools, colleges, and universities. For instance, T9 added:

It’s a serious crime and continues to plague higher education. It does not only hinder the evaluation process but also impairs skills that learners are expected to gain. Even unprepared students who cheat might score more than the one who devotes more time to study […] such a sick culture certainly demotivates true learners.

Like T9, other teachers expressed their concerns about the unfair assessment processes that could undermine the quality and skills promised by university degrees. Similar to T9, many teachers and students commented that exam cheating could have adverse impacts not only on the academic development of cheaters but also on the psychology of students who were non-cheaters.

In many ways, the information provided by the respondents indicated that exam cheating has long become an epidemic in Nepali educational institutions. Also, their views reflected the fact that while the perceived seriousness of exam cheating behaviors significantly varies among them, exam cheating can largely impair the academic integrity that educational institutions, teachers, and students are expected to adhere to.

Methods of Exam Cheating

In the interviews, almost all the respondents admitted their engagement in either or both of the two dominant methods of cheating—conventional method (use of pen, paper, notebooks, and other belongings); and modern methods (use of technological devices like calculators, smartphones and smartwatches). It became evident from the interviews that while almost all respondents confessed to adopting mainly conventional methods of cheating, half of the student respondents accepted adopting both the conventional and modern ways of cheating on examinations at least once in their academic careers. In describing conventional methods of cheating, both teachers and students agreed on their cheating behaviors that entailed at least one among using cheat sheets and crib notes; writing on body parts, clothes, admit cards, graph papers, and other stationery items such as geometry box; and either copying from or peeking at other examinees’ answer sheets, and allowing other examinees to copy from their answer sheets. Further, many students reported hiding cheat sheets either in the sleeves, socks, necktie, belt, or in “chest and undergarment” (S6) and accessing them at the opportune time when invigilators seemed inattentive. For example:

Many times, I have unstitched the lower section of the necktie and inserted tiny pieces of cheat in it. Some of my friends used to fold it inside their sleeves, others hid it inside their belts. Once it is in, students always know how to use them. (S9)

Students often manage to look at solutions. If they couldn’t, once they go to toilet, they copy it on their palms or memorize. (S18)

Other students also revealed that they had concealed cheat sheets, crib notes, and notebooks in the restrooms quite earlier than their exam started and accessed them once they were allowed to use the restrooms. Further, students shared:

Often, there is hardly any space to place the feet in the toilet due to torn pieces of books, and notes on the floor […]. Only the thing is you need to find what you need. (S6)

With regard to modern methods, almost half of the student respondents reported using technological devices such as smartphones and smartwatches either to google the answers or check the shots they had taken. These students reported that their peers even used wireless pods and Facebook Messenger to transmit exam questions to people outside the exam hall. Like many students, S10 and S17 commented:

It is easier to carry a phone rather than a book and a mobile phone with internet access is more than just a book. (S10)

Students often hide phones inside their socks to cheat [...] It is so funny that one of my friends had even made a TikTok in the exam hall. (S17)

These examples illustrate how students could outsmart exam officials and invigilators and involve in academic dishonesty. Their voice did not only represent the voice of many other students but also suggested the fact that how students had normalized modern methods of cheating that often went unnoticed in educational institutions and motivated them to persistently engage in cheating.

Surprisingly, the majority of the students regarded some forms of cheating, such as signalling answers with fingers, glancing at others’ papers, asking some questions with friends and teachers for clarity, and letting other examinees copy from their answer sheets as trivial activities. Rather, they indicated these forms of cheating had been a commonly acceptable culture among students and teachers. Surprisingly, most respondents perceived blatant copying from a book, solution papers, notes, and smartphones only as serious cheating.

Factors of Exam cheating

Pressure for Marks/Grades

Almost all the respondents, both teachers and students, admitted that one of the major reasons behind cheating was the over-emphasis given to marks/grades. Such importance directed students in learning the ways of securing good grades or passing the exams disregarding its long-term impacts. The majority of the respondents specified “peer behaviors and family pressure” for marks/grades as a supportive factor of cheating. When everyone seemed busy cheating in the exam halls, those not previously interested also collected some courage for this unplanned act (S13). Similarly, S8 shared that “If I see someone cheating, I forget what I know and that forces me to do the wrong.” Additionally, sometimes students cheated to prove to themselves (in front of their family and friends) that they could pass the exam. S6 stated that when passing an exam becomes a “matter of reputation,” students took cheating as the best alternative. S7’s argument in this regard was identical to S6’s when he argued that the family’s direct or indirect pressure for good grades or pass marks ended up in cheating because what counts is grades on transcripts. The respondents revealed that students, chased by “score-obsession” (T7), concentrated more on ‘marks-making’ because it was also “associated with status” (T1) and significant criteria that would assist them to be eligible in the “job market and promotion” (S11). Though the respondents shared their awareness about the ethical aspects of cheating— cheating violates academic rules and degrades institutions’ integrity, ethics, and moral values— when the psychology of “anyhow pass” (T9) or/and grades-mania pressurized them, students resorted for cheating as an easy recourse. Both teacher and student respondents, for instance, shared:

Grades are your fortune. A low grade means you can’t study in a good college with subjects you like and even can’t sit in an entrance. If you have good grades, you got your fortune even with various scholarships. (S7)

The main reason is the belief system that the marks one obtains determine his academic, social, economic, or administrative status. (T1)

These representative voices are helpful to assert how good-grade syndrome became an overriding motive for cheating among Nepali students. It shows their involvement in cheating was one way or the other directed by good future opportunities with better GPAs or higher percentages reflected in their transcripts.

One interesting point that we observed was that students whether academically sound or unsound, cheated in the exams for the sake of the marks. For S8, it was only “a matter of chance,” – talented students cheat to “maintain their place/position in the class” and to “increase their score” whereas weak students cheated “to pass their exams.” S4 aligned with S8 when she said, “Talented students aim to top, whereas average always aim for better.” Similarly, S5, also agreed with S8 and S4 when she reported that she had seen many talented students carrying cheats with them. It is further justified when T8 reported that many times he had caught diligent students red-handed in the exam halls.

Nature of Questions

The majority of the teachers and a few students pointed out the nature of questions in examinations as one of the main instigators of cheating. Their main proposition was that the examination system of Nepali academic institutions either stimulated rote-learning or encouraged cheating to secure good grades. Teachers believed that the university questions, both in yearly-based and semester systems, often tested the capacity to memorize and reproduce information instead of expecting some creative insights as the answers to the questions. The data show that cheating became more frequent with the repetitive nature of the questions, or the questions demand to “‘define’, ‘describe’, ‘enumerate’, or ‘explain’” (S12), and question setters’ negligence to follow the grid. T3 expressed her dissatisfaction vis-à-vis the question setting. When question setters did not follow grids, she argued, students wallowed in confusion and took shelter on pieces of paper, pages of notes, and mobile screens. T7 pointed out that if courses were designed to teach “what, how, and who only, and questions are set accordingly, then the answer is in the tip of a finger.” Students did not need to think at all to answer such questions, nor they needed to exploit their creative faculty of mind— “answer can be reproduced through cheating” because such questions have universal answers (T12). In like vein, other teachers shared:

We should add a creative edge to our questions so that students won’t be able to lift ready-made answers from anyone or anywhere. (T5)

We should maneuver our questions and assignments in such a way that cheating becomes pointless. (T11)

These remarks made by the respondents helped us to infer how exam question patterns stemming from professional carelessness and lack of skill on the part of the one who sets them was a determining factor in encouraging students to cheat.

In many respects, reported information indicated that question patterns did not only fail to promote students’ creative and critical abilities but also seem to have aggravated the perennial phenomenon of students’ engagement in exam cheating in Nepali educational institutions. Also, teachers’ expressions call for a need to reconsider designing exam questions.

Other Factors

It became evident from the interviews with students that some of them were deprived of quality teaching and learning with qualified teachers. They indicated that when they were deprived of such a facility, the result could be course incompletion that compelled students to resort on cheating. Additionally, as responded, Covid became “a reason for course incompletion” (S7) during the Covid years and it served as a cause for cheating. And importantly their final exams, during those years, were held in their home centers, and they were tempted to cheat in an unmonitored environment. In some cases, as respondents reported that even some academic institutions were agents for encouraging cheating because they pressurized students “to pass the exams by hook or by crook” (T6) so that they would be recognized as a ‘good college’ having good exam results. In other cases, students were involved in this act because they lacked confidence in the subject matter due to their “laziness toward study” (T3, S4, T2, T10) or “negligence of students” (S1, S5, S2, S16), “negligence of teachers” (S10, S5, S16, S17), “role of invigilators” (T3, S3, S8, S14), and “spending time on social media” (T3, S5). They also informed that “individual and/or family problems” (S1, S5) like work-study-family time management, and poor economic conditions to afford books and other materials forced them to shelter on cheating.

Deterring Exam Cheating

All the respondents thought that complete deterrence of exam cheating was almost unlikely in the education sector. Although the respondents were divided in opinions in many instances regarding what could prevent exam cheating, their views, to a greater extent, still pointed to three major strategies to discourage exam cheating among students.

Firstly, the majority of the respondents had a common understanding that if higher educational institutions transformed their focus from marks/grades to skill-based approaches to teaching and evaluations that promote students’ creative abilities, exam cheating could be significantly reduced. T1, for instance, said:

Society and the government should realize and act accordingly that one shouldn’t be judged only by three hours of examinations and the marks printed on a sheet of paper. A change could happen if students are assessed based on their creative and continuous performance.

T1’s opinion emulated the voice of the majority of teachers and almost half of the students who highlighted that improvement in the evaluation system could significantly promote students’ engagement and confidence in course-related content to discourage exam cheating. It also reflected the idea that implementing creative and continuous “labor-based, engagement-based, project-based” (T8), and “performance-based evaluation systems” (T1) rather than “a three-hour close examination system” (S6, S11) could have significant impacts on students’ perceived opportunity to cheat. Some respondents, especially teachers, mentioned that “weak assignment design” (T7, T6, T4) was a significant factor that encouraged cheating amongst students. As they detailed in the interviews, unless the assignment requires the personal and original involvement of the students, students take refuge in cheating.

However, a fraction of other respondents seemed skeptical of these strategies as they believed that dishonest students always could locate ways to cheat regardless of the evaluation system. S8, S10, and S5, for instance, thought that the evaluation system was “less important” and it “won’t make any difference”.

In the majority of students and slightly more than half of the teachers’ views, the second strategy could involve imposing a robust mechanism of “vigilance” (S1, S8, S2, S15) both inside and outside the exam halls. To this end, they indicated that exam officials and invigilators need to reduce examinees’ perceived cheating opportunities by ensuring proper spaces between them, identifying students’ potential cheating strategies and constant monitoring, prohibiting technological devices, and strictly following the time limit allowed for restrooms and its routine monitoring or even by prohibiting restroom breaks, while exams are being administered.

More importantly, almost all the respondents viewed the third strategy—educating teachers and students about academic honesty, morality, and accountability—would be the most effective approach to deterring exam cheating. For instance:

The problem in government-funded campuses is that the teachers really ignore their duties. They do not care whether the student study or not. They even do not bother to complete the course in time. (S8)

It is necessary to raise awareness that cheating leads nowhere […] inspire all […] I mean administrators, teachers, and students to honestly play their parts. (T10)

In sum, these examples highlighted the views of many other respondents whose voices emphasized that instilling educational honesty in students, motivating both teachers and students for moral and professional development and responsibilities, and inculcating academic culture among all could be only the most effective, sustained, and viable approach to deterring exam cheating in the long run.

Discussions and Conclusions

In this study, we explored teachers’ and students’ experiences and perceptions of exam cheating behaviors in Nepali educational institutions—school through higher education—particularly focusing on Grade XII students (who had taken final examinations prior to the data collection), university undergraduate and graduate students, and teachers. In light of the findings, we noted that the phenomena of students’ exam cheating behaviors have long been an epidemic in all levels of education in Nepal. Respondents’ narratives of exam cheating behaviors either in coordination with peers or exam officials and invigilators both pre and post Covid era painted scary pictures of academic dishonesty existing in Nepal. For example, out of 30 respondents (12 teachers and 18 students) involved in this study, 11 teachers admitted having cheated at least once and all the students confessed cheating more than once. On top of that, the majority of students indicated that they had not only frequently cheated in the past, including Covid era examinations that were held in unmonitored environments in home centers, but also suggested that they were more likely to cheat in the future examinations if they had such opportunities. This highlighted the fact that the frequency and likelihood of students’ engagement in exam cheating in Nepal appear to be far more alarming compared to the plethora of research that investigated the prevalence and self-reported exam cheating behaviors in the international contexts (Bacon et al., 2020; Bernardi et al., 2012; Busch & Bilgin, 2014; Chala, 2021; Davis et al., 2009; Kobayashi & Fukushima, 2012; Krienert et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2012). Contrary to the prior research findings (International Center for Academic Integrity, 2020; McCabe et al., 2012), our study found that students’ exam cheating behaviors were more likely in higher education degrees than in high schools.

Interestingly, our findings corroborate with prior research in many instances in terms of how, when, and why students cheat. With regard to how examinees cheat, as indicated in existing literature, respondents in this study also reported having employed a range of both traditional and modern cheating methods to access unauthorized materials and information during examinations (Chala, 2021; Davis et al., 2009; Dawson, 2021; Krienert et al., 2022). Respondents’ reported information revealed the widespread use of cheat sheets and crib notes, whether hidden in the sleeves, socks, neckties, belts, chest, and undergarments or clues written on body parts, clothes, admit cards, graph papers, and other stationery items such as geometry box. Also copying from or peeking at other examinees’ answer sheets, and allowing other examinees to copy from their answer sheets were other common ways of cheating among the students. Moreover, students’ involvement in modern forms of cheating, particularly assisted by digital technologies such as smartphones, smartwatches, wireless pods, Internet, and social media, was rampant in the examinations (Dawson, 2021). Surprisingly, although the majority of the students regarded most cheating behaviors as unacceptable, they had lenient attitudes toward some forms of cheating, such as signalling answers with fingers, glancing at others’ papers, asking some questions with friends and teachers for clarity, and letting other examinees copy from their answer sheets, which they perceived as trivial activities. Surprisingly, most respondents regarded only blatant copying from a book, solution papers, notes, and smartphones as serious cheating behaviors. More interestingly, the respondents (both teachers and students) suggested that many forms of cheating, including technology-driven cheating, had been a commonly acceptable culture among students and teachers. In this sense, both teachers and students in Nepali educational institutions seem to have largely normalized cheating behaviors as minor problems while cheating was considered one of the highly valued social abilities among adult peers to gain an unfair advantage. Numerous studies have indicated that students who perceive cheating as abilities to garner success can be always at higher risk of normalizing cheating behaviors (Grenness, 2022; McCabe et al., 2012; Moss et al., 2018). These findings, to a greater extent, are also congruent with the findings of Chala (2021) who contends that cheating would be more pervasive where students normalize cheating behaviors as minor problems and continue to engage in such behaviors. It is clear that the normalization of cheating behaviors in Nepali educational institutions has been also hugely influenced by other numerous factors identified in the present study. For example, as Chala (2021) noted, limited understanding of what constitutes exam cheating and perceived opportunities to cheat among students have resulted into the normalization of exam cheating behaviors such as peeking at or copying from peers’, and allowing them to copy from their own answer sheets as trivial acts. Interestingly, although teacher respondents thought using unauthorized material such as crib notes and cheat sheets as serious acts, student respondents did not perceive them as serious as the teachers in this study and students in the international context (Preiss et al., 2013) often perceived them to be. Rather, they associated such cheating activities with a matter of luck that could be used in the opportune time to ensure better marks/grades leading to future possibilities of admission in higher degrees, scholarship grants, and potential careers (Henry et al., 2021).

Further, our findings revealed that all the respondents involved in this study were somehow aware of far-reaching consequences of cheating, such as low level of knowledge and skills, that might emanate from what they perceived as serious forms of exam cheating. Mainly students, however, admitted continuous engagement in a range of exam cheating behaviors. It is surprising why these teachers and students tended to think that academic dishonesty was largely acceptable and fail to stick to moral obligations in practice. It can be argued that their exam cheating behaviors were hugely shaped by lack of self-control (Błachnio, 2019) and perceived benefits of dishonest acts. Our findings offer enough grounds to speculate that the lack of self-control on the part of students and the perceived benefits of dishonesty, which appeared stronger than its adverse consequences, must have resulted into their continuous engagement in cheating behaviors and attitudes in terms of why exam cheating was almost unlikely to be prevented entirely, nonetheless, controllable.

More importantly, our findings provide enough evidence that the systemic culture of associating students’ overall learning outcomes and future potentialities with grades/marks can induce exam cheating behaviors. In this respect, prior research has also explained that when educational institutions and society give more priority to competition and achievement and pressurize students for better grades, students would be more likely to cheat (Anderman & Koenka, 2017; Bujaki et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2013).

Likewise, this study identified that the nature of questions, their frequency of repetitions in the examinations, and memory-based evaluation systems could largely contribute to students’ cheating behaviors. Prior studies have also highlighted that when the designs of questions are more information-focused and rarely require students to demonstrate high order thinking and creative abilities, students are more prone to cheating (Nguyen et al., 2020). Similar to the views of Nguyen et al. (2020), respondents in this study also suggested adopting cheat-resistant techniques such as prioritizing open-book examination/assessment systems and knowledge-based question designs that require students to demonstrate their critical and creative abilities, whether in the offline or online examinations. Further, our findings highlighted that designing skill-based courses that promote students’ performance based on labor, engagement, and project work play pivotal roles in reducing students’ perceived opportunity to cheat.

This study also revealed that the equally prominent factors of exam cheating could be linked to seniors’ and peers’ influences, lack of teachers’ professional skills, earnestness and accountabilities, high tolerance, and poor vigilance of examinees, examinees’ lack of confidence, perseverance and preparation for exams, and decreased educational engagement among them. These findings to a larger extent are congruent with the previous research findings (Bernardi et al., 2012; Malesky et al., 2022; Noorbehbahani et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2017). It seems that both internal factors (such as students’ low self-control, lack of confidence, perseverance and preparation for exam, and motivation, attitudes, and rationalization for cheating) and external factors (such as peers’ behaviors, grades, competition, perceived opportunity, institution, and environment) may always promote academic dishonesty, as noted by the earlier studies (Błachnio, 2019; Bujaki et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2017; Noorbehbahani et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2017). In various aspects, our respondents even rationalized their own and peers’ engagement in exam cheating on these grounds. This indicated that multiple factors, as Davis et al. (2009) noted, could always be in play to neutralize examinees’ beliefs and attitudes to exam cheating. In this regard, other studies have also emphasized that those students who have neutralization attitudes often tend to rationalize their unethical behaviors as normal activities and continue to fall into the trap of academic dishonesty despite their awareness (Meng et al., 2014; Murdock & Stephens, 2007). This suggested that whether students’ exam cheating behaviors are impacted by the lack of their understanding of what counts as cheating or influenced by internal or external factors, they are likely to fall into the trap of academic dishonesty if educational institutions and educators fail to communicate not only the value of integrity in education but also the dangers of academic dishonesty, as scholars noted (Birks et al., 2020).

In describing the deterrence strategies to cheating, majority of the respondents viewed that improvement in evaluation system (such as transforming marks/grades-focused approaches to skill-based approaches as well as cheat-resistance exam designs as suggested in the literature discussed above), maintaining ample spaces between the examinees, identifying potential cheating techniques, strictly prohibiting technological devices, as well as following the time limit allowed for restrooms or prohibiting restroom breaks during the examinations could largely reduce one’s perceived opportunity to cheat. Nonetheless, it is still worth noting that the rhetoric of all the perceived deterrents to exam cheating pointed to a blame game hugely directed either to teachers, invigilators, exam officials, or educational institutions. Therefore, education institutions and educators have greater roles to engage both teachers and students not only into the regular academic integrity conversations but also into the discussion of potential risks of academic dishonesty, as scholars argue (Bearman et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2017).

This study provides insights into teachers and students’ experiences and perception of what is cheating, why and in what forms exam cheating occurs, and how such behaviors can be prevented in Nepal. Although we do not claim the truth value of evidence that the limited samples of respondents (30) provided in this study, it should be noted that what the respondents have highlighted are of paramount importance to policymakers, curriculum designers, educational leaders, exam officials, and teachers/invigilators to identify the loopholes in education and evaluation systems. More importantly, educational institutions and teachers/invigilators need to take the note of how to communicate honesty and accountability to both teachers and students to promote moral behaviors in practice and maintain academic honesty and integrity in Nepal.

Although our study on academic dishonesty is probably the first among its kind in Nepal and is primarily based on the interviews with teachers and students, it provides enough evidence that students’ exam cheating is a pervasive issue within Nepali educational institutions. However, the findings of the study may not be generalized in all exam/ assessment situations such as terminal exams and assessments or exams on online environment since our study solely reports on teachers and students’ experiences and perceptions of cheating in final examinations that are conducted in physical mode. Therefore, we invite future studies to also investigate these issues by also involving administrators and exam officials and considering a survey design so that they can produce more powerful debates on academic dishonesty within higher education in Nepal.

Data Availability

Data associated with the study is not available publicly as it can breach the promised confidentiality of the research respondents, but will be available at the request wherever applicable.

References

Anderman, E. M., & Koenka, A. C. (2017). The relation between academic motivation and cheating. Theory into practice, 56(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308172.

Asokan, S., John, J. B., Janani, D., Jessy, P., Kavya, S., & Sharma, K. (2013). Attitudes of students and teachers on cheating behaviors: Descriptive cross-sectional study at six dental colleges in India. Journal of Dental Education, 77(10), 1379–1383. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.10.tb05613.x.

Awosoga, O., Nord, C. M., Varsanyi, S., Barley, R., & Meadows, J. (2021). Student and faculty perceptions of, and experiences with, academic dishonesty at a medium-sized canadian university. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00090-w.

Bacon, A. M., McDaid, C., Williams, N., & Corr, P. J. (2020). What motivates academic dishonesty in students? A reinforcement sensitivity theory explanation. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12269.

Baral, R. K. (2016). The higher education policy of Nepal: An analysis. Discovery Dynamics: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Research and Development, 3(1), 30–47. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341867439_The_Higher_Education_Policy_of_Nepal_An_Analysis.

Baral, R. K. (2021). Problems and challenges in higher education reforms in Nepal. TU Bulletin Special Issue, 134–152. http://tribhuvan-university.edu.np/journal/9_60f68e3bf0ae8.

Bearman, M., Dawson, P., O’Donnell, M., Tai, J., & de Jorre, T. (2020). Ensuring academic integrity and assessment security with redesigned online delivery. C. f. R. i. A. a. D. Learning. https://dteach.deakin.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/103/2020/03/DigitalExamsAssessmentGuide1.pdf.

Bernardi, R. A., Banzhoff, C. A., Martino, A. M., & Savasta, K. J. (2012). Challenges to academic integrity: Identifying the factors associated with the cheating chain. Accounting Education, 21(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2011.598719.

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205.

Birks, M., Mills, J., Allen, S., & Tee, S. (2020). Managing the mutations: Academic misconduct in Australia, New Zealand and the UK. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00055-5.

Błachnio, A. (2019). Don’t cheat, be happy. self-control, self-beliefs, and satisfaction with life in academic honesty: A cross-sectional study in Poland. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 60(3), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12534.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bucciol, A., Cicognani, S., & Montinari, N. (2020). Cheating in university exams: The relevance of social factors. International Review of Economics, 67(3), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-019-00343-8.

Bujaki, M., Lento, C., & Sayed, N. (2019). Utilizing professional accounting concepts to understand and respond to academic dishonesty in accounting programs. Journal of Accounting Education, 47, 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.01.001.

Burgason, K. A., Sefiha, O., & Briggs, L. (2019). Cheating is in the eye of the beholder: An evolving understanding of academic misconduct. Innovative Higher Education, 44(3), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-9457-3.

Busch, P., & Bilgin, A. (2014). Student and staff understanding and reaction: Academic integrity in an australian university. Journal of Academic Ethics, 12(3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-014-9214-2.

Catacutan, M. R. (2021). Attitudes toward cheating among business students at a private kenyan university. Journal of International Education in Business, 14(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIEB-01-2019-0001.

Chala, W. D. (2021). Perceived seriousness of academic cheating behaviors among undergraduate students: An ethiopian experience. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00069-z.

Chiang, F. K., Zhu, D., & Yu, W. (2022). A systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(4), 907–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12656.

Chirikov, I., Shmeleva, E., & Loyalka, P. (2020). The role of faculty in reducing academic dishonesty among engineering students. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2464–2480. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1616169.

Chirumamilla, A., Sindre, G., & Nguyen-Duc, A. (2020). Cheating in e-exams and paper exams: The perceptions of engineering students and teachers in Norway. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(7), 940–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1719975.

Cizek, G. J., & Wollack, J. A. (2016). Exploring cheating on tests: The context, the concern, and the challenges. In G. J. Cizek, & J. A. Wollack (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative methods for detecting cheating on tests (pp. 3–19). Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

Corrigan-Gibbs, H., Gupta, N., Northcutt, C., Cutrell, E., & Thies, W. (2015). Deterring cheating in online environments. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 22(6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/2810239.

Daly, A., Parker, S., Sherpa, S., & Regmi, U. (2020). Federalisation and education in Nepal: Contemporary reflections on working through change. Education 3–13: International Journal of Primary Elementary and Early Years Education, 48(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1599408.

Davis, S. F., Drinan, P. F., & Gallant, T. B. (2009). Cheating in school: What we know and what we can do. John Wiley & Sons.

Dawson, P. (2021). Defending assessment security in a digital world: Preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education. Routledge.

De Laine, M. (2000). Fieldwork, participation and practice: Ethics and dilemmas in qualitative research (1 ed.). Sage.

Dejene, W. (2021). Academic cheating in ethiopian secondary schools: Prevalence, perceived severity, and justifications. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1866803.

Fontaine, S., Frenette, E., & Hébert, M. H. (2020). Exam cheating among Quebec’s preservice teachers: The influencing factors. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00062-6. Article 14.

Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication (18 vol.). NYU press.

Gautam, M. (2017). Entrance exam cheating case: Prolonged probe to affect TU’s MBBS calendar. The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2017/10/28/prolonged-probe-to-affect-tus-mbbs-calendar.

Grenness, T. (2022). If you don’t cheat, you Lose”: An explorative study of business students’ perceptions of cheating behavior. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2116479.

Henry, C., Jurdi-Hage, R., & Hage, H. S. (2021). Justifying academic dishonesty: A survey of canadian university students. International Journal of Academic Research in Education, 7(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.17985/ijare.951714.

Hughes, J. M. C., & McCabe, D. L. (2006). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ771043.pdf.

International Center for Academic Integrity (2020). Facts and statistics. International Center for Academic Integrity. Retrieved 20 April 2023 from https://academicintegrity.org/resources/facts-and-statistics.

Jenkins, B. D., Golding, J. M., Grand, L., Levi, A. M., M. M., & Pals, A. M. (2022). When opportunity knocks: College students’ cheating amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching of Psychology, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211059067.

Jurdi, R., Hage, H. S., & Chow, H. P. H. (2012). What behaviours do students consider academically dishonest? Findings from a survey of canadian undergraduate students. Social Psychology of Education, 15(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9166-y.

Kasler, J., Sharabi-Nov, A., Shinwell, E. S., & Hen, M. (2023). Who cheats? Do prosocial values make a difference? International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00128-1. Article 6.

Kelley, R., & Dooley, B. (2014). 23–24 May 2014). The technology of cheating. 2014 IEEE international symposium on ethics in science, technology and engineering, Chicago, IL, USA.

Kobayashi, E., & Fukushima, M. (2012). Gender, social bond, and academic cheating in Japan. Sociological Inquiry, 82(2), 282–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2011.00402.x.

Krienert, J. L., Walsh, J. A., & Cannon, K. D. (2022). Changes in the tradecraft of cheating: Technological advances in academic dishonesty. College Teaching, 70(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1940813.

Lupton, R. A., & Chaqman, K. J. (2002). Russian and american college students’ attitudes, perceptions and tendencies towards cheating. Educational Research, 44(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880110081080.

Ma, Y., McCabe, D. L., & Liu, R. (2013). Students’ academic cheating in chinese universities: Prevalence, influencing factors, and proposed action. Journal of Academic Ethics, 11(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-013-9186-7.

MacLeod, P. D., & Eaton, S. E. (2020). The paradox of faculty attitudes toward student violations of academic integrity. Journal of Academic Ethics, 18(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09363-4.

Malesky, A., Grist, C., Poovey, K., & Dennis, N. (2022). The effects of peer influence, honor codes, and personality traits on cheating behavior in a university setting. Ethics & Behavior, 32(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1869006.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_2.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what educators can do about it. JHU Press.

Meng, C. L., Othman, J., D’Silva, J. L., & Omar, Z. (2014). Influence of neutralization attitude in academic dishonesty among undergraduates. International Education Studies, 7(6), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n6p66.

Mensah, C., Azila-Gbettor, E. M., & Asimah, V. (2018). Self-reported examination cheating of alumni and enrolled students: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9286-x.

Miller, C. (2013). Honesty, cheating, and character in college. Journal of College and Character, 14(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcc-2013-0028.

Miller, A. D., Murdock, T. B., & Grotewiel, M. M. (2017). Addressing academic dishonesty among the highest achievers. Theory into practice, 56(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1283574.

Ministry of Education (2016). School Sector Development Plan, Nepal, 2016–2023. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Retrieved from https://www.doe.gov.np/assets/uploads/files/3bee63bb9c50761bb8c97e2cc75b85b2.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3w24ivZyKumugD0Lf0SMQyG3TKBgktLzDjpFraQLNyx37zb1__Q-epvS4.

Moss, S. A., White, B., & Lee, J. (2018). A systematic review into the psychological causes and correlates of plagiarism. Ethics & Behavior, 28(4), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2017.1341837.

Murdock, T. B., & Stephens, J. M. (2007). Is cheating wrong? Students’ reasoning about academic dishonesty. In E. M. Anderman & T. B. Murdock (Eds.), Psychology of Academic Cheating (pp. 229–251). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372541-7/50014-0.

Nguyen, J. G., Keuseman, K. J., & Humston, J. J. (2020). Minimize online cheating for online assessments during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 3429–3435. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00790.

Noorbehbahani, F., Mohammadi, A., & Aminazadeh, M. (2022). A systematic review of research on cheating in online exams from 2010 to 2021. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8413–8460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10927-7.

Nugroho, M. A., Abdurohman, M., Prabowo, S., Nurhayati, I. K., & Rizal, A. (2023). 2023//). Intelligent remote online proctoring in Learning Management Systems. Singapore: Information Systems for Intelligent Systems.

Preiss, M., Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., & Nohavova, A. (2013). A cross-country evaluation of cheating in academia—A comparison of data from the US and the Czech Republic. Journal of Academic Ethics, 11(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-013-9179-6.

Rankin, K. N., Nightingale, A. J., Hamal, P., & Sigdel, T. S. (2018). Roads of change: Political transition and state formation in Nepal’s agrarian districts. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(2), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1216985.

Roe, J. (2022). Reconceptualizing academic dishonesty as a struggle for intersubjective recognition: A new theoretical model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01182-9.

Srikanth, M., & Asmatulu, R. (2014). Modern cheating techniques, their adverse effects on engineering education and preventions. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 42(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.7227/ijmee.0005.

Tabsh, S. W., Kadi, E., H. A., & Abdelfatah, A. S. (2019). Faculty perception of engineering student cheating and effective measures to curb it 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

The Himalayan Times (2017). 30 held for cheating, helping students cheat. The Himalayan Times. https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/30-held-cheating-helping-students-cheat/.

Topîrceanu, A. (2017). Breaking up friendships in exams: A case study for minimizing student cheating in higher education using social network analysis. Computers & Education, 115(C), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.08.008.

UGC (2022b). Education management information system: Report on higher education (2020/21). https://www.ugcnepal.edu.np/publications/1/14.

UGC (2022a). Annual report (2020/21). https://www.ugcnepal.edu.np/uploads///upload/hKUV3N.pdf.

Vučković, D., Peković, S., Blečić, M., & Đoković, R. (2020). Attitudes towards cheating behavior during assessing studentsá¾½performance: Student and teacher perspectives. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00065-3.

Walters, G. D., & Morgan, R. D. (2019). Certainty of punishment and criminal thinking: Do the rational and non-rational parameters of a student’s decision to cheat on an exam interact? Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 30(2), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2018.1488982.

Whitley, B. E., & Kost, C. R. (1999). College students’ perceptions of peers who cheat. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(8), 1732–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb02048.x.

Yang, S. C., Huang, C. L., & Chen, A. S. (2013). An investigation of college students’ perceptions of academic dishonesty, reasons for dishonesty, achievement goals, and willingness to report dishonest behavior. Ethics & Behavior, 23(6), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2013.802651.

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2017). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A study of individual factors. Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535.

Zhao, L., Mao, H., Compton, B. J., Peng, J., Fu, G., Fang, F., & Lee, K. (2022). Academic dishonesty and its relations to peer cheating and culture: A meta-analysis of the perceived peer cheating effect. Educational Research Review, 36, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100455. Article 100455.

Funding

This is not applicable as we have not received any financial support or funding from anywhere for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure Statement

We do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghimire, S.N., Bhattarai, U. & Baral, R.K. Academic Dishonesty Within Higher Education in Nepal: An Examination of Students’ Exam Cheating. J Acad Ethics 22, 303–322 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-023-09486-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-023-09486-4