Abstract

This study investigated faculty attitudes towards student violations of academic integrity in Canada using a qualitative review of 17 universities’ academic integrity/dishonesty policies combined with a quantitative survey of faculty members’ (N = 412) attitudes and behaviours around academic integrity and dishonesty. Results showed that 53.1% of survey respondents see academic dishonesty as a worsening problem at their institutions. Generally, they believe their respective institutional policies are sound in principle but fail in application. Two of the major factors identified by faculty as contributing to academic dishonesty are administrative. Many faculty members feel unsupported by their administration and are reluctant to formally report academic dishonesty due to the excessive burdens of dealing with paperwork and providing proof. Faculty members also cite unprepared students and international students who struggle with language issues and the Canadian academic context as major contributors to academic dishonesty. This study concludes with recommendations for educators and recommendations for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A perceived lack of student academic integrity is seen as a serious threat to the fundamental function of educational institutions (Bertram Gallant 2008; Davis et al. 2009). Yet, academic dishonesty has not been thoroughly explored in Canada (Christensen Hughes and McCabe 2006a, b; Eaton and Edino 2018). Although research on this topic is increasing, this work offers one of the first investigations of policy nationally.

Universities invest significant resources into crafting policies to guide student and faculty behaviour. Thoughtfully considered and constructed policy can be invaluable in helping to form a culture of academic honesty by establishing a framework of what is acceptable and not acceptable in an academic context (Morris and Carrol 2016). Academic integrity/dishonesty (AID) policies must be tailored to meet the unique needs of each institution yet contain “the essential elements of an effective policy”. These essential elements are categorized under: 1. Policy Development; 2. Statement of Policy; 3. Definition/Explication of Prohibited Behavior; 4. Specification of Responsibilities; 5. Specification of Resolution Procedures for Both Formal and Informal Resolution of Suspected Cases of Academic Dishonesty; 6. Specification of Penalties; 7. Remediation; 8. Record Keeping; 9. Specifications of Preventative Measures Faculty Should Implement; 10. Implementation of Policy; 11. Faculty Training; 12. Student Assistance/Orientation (Whitley and Keith-Spiegel 2001 p. 325).

The aim of this study was to explore differences in focus and quality of academic integrity policies and the possible relationship between policy quality and faculty members’ attitudes about student academic integrity and misconduct. This study analyzed the AID policies at 17 Canadian universities and compared policy quality as elucidated by Whitley and Keith-Spiegel (2001) with faculty attitudes and experiences derived from a survey of faculty members at each university.

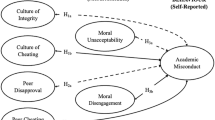

As the culture of an academic institution can have a profound effect on students’ attitudes and behaviors around academic dishonesty (McCabe 1993; McCabe et al. 2012), our first research question was, “Do the institutions’ AID policies focus on integrity, rule compliance (deterrence), or a combination using Bertram Gallant’s 2008 definitions of these three categories?” Given the importance of quality policy to the achievement of its purposes (Freeman 2013) the AID policies of the selected universities were compared to the framework for an effective policy advocated for by Whitley and Keith-Spiegel (2001).

The question of “What are typical faculty attitudes and beliefs about student academic integrity and dishonesty?” arose from the number of studies that found that a trusting relationship between students and their instructor can lead to increased learning and a corresponding decrease in students’ desire to cheat (Genereux and McLeod 1995; Jordan 2001; Stearns 2001). Although research has shown a positive relationship between instructors’ adherence to academic dishonesty policies (e.g., McCabe 1993; McCabe and Pavela 2004; Whitley and Keith-Spiegel 2002) and student honesty, many faculty members are reluctant to discuss the issue or deal with violations. As a result, we chose to explore the question of “What are typical faculty beliefs about their institutions’ policies surrounding student academic integrity and dishonesty?”

Finally, to expand the discussion in this area we wanted to examine the relationship, if any, between institutional policy and faculty attitudes towards student academic integrity and dishonesty.

Literature Review

We identified three main themes in the literature relevant to this study: large-scale surveys of students, plagiarism and contract cheating, and responses to academic dishonesty. We elaborate on each of these major themes in the sections that follow.

Large-Scale Studies

The first large-scale exploration of academic dishonesty in the US, involving over 5400 students on 99 campuses, concluded that the self-reported rates of cheating for students were 50% to 70% (Bowers 1964). A replication of Bowers’ work three decades later showed a minimal increase in academically dishonest behaviours (McCabe and Bowers 1994), although subsequent large-scale surveys found that more than 75% of undergraduates had engaged in serious cheating at least once during their academic careers (McCabe 2016; McCabe et al. 2001; Christensen Hughes and McCabe 2006a, b).

In recent years, there has been a resurgence in large-scale research internationally in an effort to understand the phenomenon on a broader scale (Bretag et al. 2018; Glendinning 2014; Mahmud et al. 2019). However, there has been almost no large-scale research on academic dishonesty in Canada since Christensen Hughes and McCabe’s (2006a, 2006b) landmark study of Canadian universities over a decade ago (Eaton and Edino 2018).

Plagiarism and Contract Cheating

Plagiarism

Plagiarism remains a contentious issue in the literature on academic integrity and dishonesty. The most common definition of plagiarism is copying someone else’s words or ideas and claiming them as one’s own (e.g., Bertram Gallant 2008; Martin 1994). Institutional definitions are imprecise, definitions continue to evolve (Eaton 2017) and some claim that defining plagiarism is an impossible task (Howard 2000).

Students sometimes plagiarize unintentionally (Kier 2013, 2019; Martin 1994; Walker 2008). Some scholars consider plagiarism a question of teaching and learning, as students need to be taught how to write in an academic style (Hall et al. 2018; Howard 2016; Levin 2003, 2006). Others argue that plagiarism would be rendered obsolete if students’ focus shifted from a degree–certifying learning–to meaningful learning (Hunt 2010).

Plagiarism using the internet or other digital sources has been addressed at some length in the literature (Kier 2019; Leung and Chang 2017; Panning Davies and Moore Howard 2016; Scanlon and Neumann 2002; Sutherland Smith 2008). Contemporary students’ immersion in a culture of file sharing and free downloads has given them a different view of the ethics of sharing. They do not understand the need for citation and originality and so ignore the rules (Blum 2009a, 2009b).

International students, or students whose first language is not English, are seen to be persistent plagiarists (Liu 2005; Tysome 2006). However, others argue that this assumption may be erroneous (Bretag 2019; Bretag et al. 2018; Eaton and Burns 2018; Liu 2005). In Canada, to our knowledge, this issue has not been subject to empirical study.

Contract Cheating

Contract cheating occurs when a student has a third party complete their coursework. This frequently involves payment to the third party and is commonly facilitated through essay “practice” websites (Clarke and Lancaster 2006). In effect, the essay mills of yesteryear are using social media–savvy marketing techniques (Lancaster 2019). Although contract cheating appears to be on the rise (Newton 2018), rates are subject to debate and range from 3.5% (Curtis and Clare 2017) to 15% (Newton 2018). In one study, more than 50% of students admitted they would buy an assignment under the right circumstances, but potential penalties and fear of a poor product were significant deterrents (Rigby et al. 2015).

Responses to Academic Dishonesty

The academic culture of an institution can have a profound effect on student attitudes towards academic integrity (Bertram Gallant and Drinan 2008; Mahmud et al. 2019; McCabe 2005; McCabe and Drinan 1999; McCabe and Pavela 2004). Implementing a process in which students are involved in policy development, implementation, and judicial application of policies can reduce academic dishonesty (McCabe 1993; McCabe and Trevino 1996; McCabe et al. 2012; Stoesz et al. 2019). At the very least, students need to be clear about what the policies are (Mahmud et al. 2019; Stoesz et al. 2019). Institutional values and policy must be aligned in order to be effective:

One of the most important aspects of reducing cheating is to ensure that faculty and students understand the values and expectations of the institution. The institution’s policy of academic integrity must reflect these values and be actively promoted by the administration (Carpenter et al. 2005, p. T2D-13).

Methodology

Research Design and Rationale

This study had two purposes, one qualitative and one quantitative. First, we qualitatively investigated the nature of AID policies at selected Canadian universities, first by classifying them according to Bertram Gallant’s (2008) taxonomy of the most common institutional responses to academic dishonesty: rule compliance (deterrence), integrity, or a combination of these approaches. Further, we evaluated the policies against Whitley and Keith-Spiegel’s (2001) framework for what makes an effective policy, then converted this qualitative data into a numerical score. Each policy was then assigned to one of Pavela’s (n.d.) four categories of academic dishonesty policy: (a) honor code, a fully developed and coherent set of policies and procedures in which students play an important role; (b) mature, a well-developed and coherent set of policies and procedures that are widely followed but lack meaningful student involvement; (c) radar screen, a set of policies and procedures in place but not fully developed or followed; and (d) primitive, minimal policies and procedures. There are other policy evaluation frameworks available (e.g., Bretag et al. 2011) but Pavela’s was chosen as its categories matched well with Whitley and Keith-Spiegel’s framework and it is linked to as a trusted resource on the International Center for Academic Integrity website.

We also quantitatively examined faculty beliefs and actions regarding academic integrity and dishonesty and compared it with their opinions of, and adherence to, their institutions’ AID policy. The research design followed a modified concurrent triangulation design (Creswell and Plano Clark 2010). Despite the difficulties inherent in this approach, the qualitative policy review including related artifacts informed and enhanced the quantitative analysis of faculty opinions and actions around institutional strategies for academic integrity.

Data Sources

For the qualitative policy review, this study relied on files made publicly available through institutional websites, including (a) documents, webpages, and artifacts related to AID policies (e.g., online tutorials, academic honesty resources prepared for students) and (b) archives (university publications) of proceedings against students for breaches of academic integrity policy where available. While the number of documents and sites visited varied by institution, all sites related to academic integrity were reviewed where present. In other words, the dedicated academic integrity webpage, AID policies and procedures and related links were reviewed for all institutions. If an institution had a library site or specific departmental sites dedicated to academic integrity or an online student tutorial, then these sites were reviewed as well.

Population and Sample

The population of the study was Canadian universities belonging to Universities Canada (Universities Canada n.d.) and full-time faculty teaching undergraduates. The sample was purposive-mixed-quantitative (Teddlie and Yu 2007). In order to generate a sample that would give an accurate view of AID policies across Canada, 18 universities, two from each province with more than one university and one each from Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Laborador were chosen to yield a high sample-to-population ratio. The U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities is a group of the top research universities in Canada that works together to promote sustainable research and higher education in Canada and abroad. For provinces with a U15 institution (U15 n.d.), we chose one institution from the U15 and an additional university randomly. For provinces without a U15 member, we selected two universities. A replacement strategy (Gorard 2001) was used as two initially selected institutions declined to participate. Additional participants were selected at random from remaining candidates from a particular province.

The population for the survey was all faculty members primarily teaching undergraduates at the selected universities. The sampling frame was a list of faculty who teach undergraduate courses compiled from each university’s official website. Invitations to participate in the survey were emailed to 25 randomly selected faculty members at each of the 17 selected universities. As this approach did not yield a significant response, requests for participation were sent to deans and chairs at each institution.

Instrumentation

The instruments for the qualitative portion of the study were a matrix for determining how each institution’s AID policy fit in Bertram Gallant’s (2008) taxonomy and a checklist adapted from Whitley and Keith-Spiegel’s (2001) framework for an effective policy.

Policy Evaluation Checklist

The literature on policy evaluation matrixes being applied to institutional AID policies is limited. Bretag et al. (2011) developed an evaluation framework based on best practices in Australian universities and divided into five core areas: access, approach, responsibility, detail, and support. The International Center for Academic Integrity (2012) developed the Academic Integrity Rating System to allow institutions to assess their own internal AID policies and procedures. We selected the Whitley and Keith-Spiegel (2001) framework as the basis of policy analysis for this work because it had more detailed descriptors and lent itself to detailed external analysis. The qualitative evaluation based on the checklist was converted to a numerical score and each policy was given a percentage ranking, to facilitate comparisons, and then placed in one of Pavela’s (n.d.) categories of institutional policy. These instruments were chosen because they are based on a wide variety of literature that explores academic integrity, and thereby inform institutional responses to student academic dishonesty (e.g., Jendrek 1989; Levin 2003, 2006; McCabe 1993, 2005; McCabe and Bowers 1994; McCabe and Trevino 1996; McCabe et al. 1999, 2001; Park 2003; Pavela and McCabe 1993).

The instrument for the second part of the study was an online survey of approximately 30 multiple-choice and short-answer questions (depending on the respondent’s choices) with space for commentary. We followed guidelines for the construction of conventional survey questions (Fink 2009; Fowler 2002; Gorard 2001) and online surveys and question types (Eysenbach 2005; Fink 2009). The question content was adapted in part from a previous survey of faculty attitudes and responses to academic dishonesty (Coalter et al. 2007).

Analysis 1: Examination of Policy

Rule Compliance, Integrity, and Combination Policy Types

The AID policies of the selected universities were categorized as rule compliance, integrity, or combination types (Bertram Gallant 2008) by matching “the themes or patterns, ideas, concepts, behaviors, interactions, incidents, terms or phrases used” (Taylor-Powell and Renner 2003, p. 2) with the dominant characteristics of the categories. We also examined data for repetition, as well as similarities and differences, in relation to the key concepts of each category (Bernard and Ryan 2010). In order to ensure consistency and reliability, all data analysis was done by a single rater.

Rule compliance policies are primarily concerned with emphasizing the seriousness of academic dishonesty and the punishments that accompany it. The focus is on due process, disciplinary bodies, violations, and sanctions (i.e., crime and punishment). Academic dishonesty is “treated primarily as a disciplinary issue” (Bertram Gallant 2008, p. 36); administrators handle policy and process with minimal input from students or faculty members. We categorized policies as rule compliance if the wording, supporting documents, and related media focused primarily on consequences and punishment for academic offences.

Integrity policies are based on the assumption that academic dishonesty results from a lack of moral or ethical reasoning. The primary approach is to prevent academic dishonesty by teaching the values of honesty and integrity. Integrity policies often focus on student involvement, and in the US they contain honour codes or modified honour codes, which are rarely used in Canadian universities (Bertram Gallant and Drinan 2008). We categorized policies as integrity if the wording, supporting documents, and related media focused on honesty as a core value of education and emphasized teaching and learning in the remediation of academic dishonesty.

We designated policies as combination if they placed approximately equal emphasis on integrity, teaching students about how to learn, why integrity is important, and rule compliance.

Primitive, Radar Screen, Mature, or Honor Code Policy Types

We used a checklist developed from Whitley and Keith-Spiegel’s (2001) framework for an effective policy to evaluate the elements of each institution’s response to academic dishonesty. The checklist included 12 categories: policy development, statement of policy, definition/explication of prohibited behaviour, specification of responsibilities (for students, faculty members, and administrators), specification of resolution procedures, specification of penalties, remediation, record keeping, specification of prevention measures, implementation of the academic integrity policy, faculty training, and student assistance/orientation. Each category contained several items. For example, the category of policy development was intended to determine which of administrators, faculty members, and students were involved in the development and revision of each institution’s AID policy. A form of content analysis based on keywords and phrases from the checklist was used to evaluate the policies and associated resources to determine if they contained the elements mandated in the checklist (Grbich 2007; Thomas 2003). The presence or absence of the qualitative elements in each category were scored on a binary basis—present or absent/no data (Abeyasekera 2005). We used a form of the constant comparison approach to check the data reduce errors in the analysis (Flick 2007). For each item, we reviewed an institutions’ score three times. Detailed notes were taken regarding the location and the content of the institutional policy or resource that supported the scoring decision. One researcher did all data review and scoring to ensure rater reliability (Flick 2007; Grbich 2007). When the checklist evaluation was complete, the total score was converted to a percentage to facilitate comparison of the policies.

We then sorted each institution’s AID policy into one of Pavela’s (n.d.) categories and assessed them: primitive (60%–69%); radar screen (70%–79%); mature (80%–89%); honor code (90%–100%). (We did not rename the latter category even though honour codes or modified honour codes are not common in Canada.) We cross-checked the category placement against the essential elements that defined each category to ensure that the policies were categorized accurately and consistently and that a policy assigned to a particular category matched the essential elements of the category. This was important for policies that scored near the borderline between two categories.

Analysis Part 2: Quantitative Survey

We tabulated the survey results to examine respondents’ common or predominant attitudes toward academic dishonesty. Qualitative comments were divided into thought units (individual ideas) and coded (McCabe et al. 1999). We also looked for repetition and similarities and differences (Bernard and Ryan 2010). Constant comparison and multiple evaluations of the categories and individual items within each category were done to ensure accuracy and consistency (Gibbs 2007). We compared survey data to the policy analysis for possible links between policy and faculty attitudes. Finally, trends in the survey data and the dominant trends from the qualitative examination were examined in an attempt to generalize results for the Canadian context. For all data analysis, the analysis was done by one rater to ensure consistency.

Results

Policy

Of 17 universities, 13 had a combination orientation, while three had a rule compliance orientation and one had an integrity orientation. Eleven policies ranked as mature, four policies as radar screen, and two as honor code. No policies ranked as primitive. The percentage scores ranged from 70 to 96. Note that the total possible score varies by institution. This occurred because some items on the policy evaluation checklist did not apply to all institutions. For example, Section 5a “Informal resolution” deals with the policy provisions for faculty to informally address “minor” violations of academic integrity. However, not all institutions allow for faculty to informally resolve even minor violations of academic integrity. Therefore, the decision was made to exclude non- applicable sections ---when they were the result of deliberate and explicit policy and procedural choices---from the policy evaluation score. The results are summarized in Table 1, where each institution’s name has been replaced by a letter.

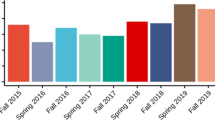

Survey

A total of 412 faculty members from 17 institutions who primarily teach undergraduates, representing a cross-section of academic ranks and teaching experience, completed the survey. Note that some percentages do not add up to 100 as participants could chose multiple responses for some items.

Knowledge of Policy

Over 90% of respondents considered themselves to be familiar with or knowledgeable about their institution’s policy. “Discussion with colleagues” was the most common way of learning about it (61.2% of respondents). Institutional orientation (35.6%), websites (34.6%), and academic catalogues (33.9%) were also popular sources of information. Many respondents did not concern themselves with the policy until triggered by an external stimulus—most commonly an encounter with student academic misconduct or an institutional email reminder to include policy details on course syllabi. Lack of consistent implementation of the policy was the most common concern. Nearly 63% of respondents did not know which stakeholders were involved in the development or revision of AID policy.

Fairness of Policy

Although more than 50% of respondents considered their institutional policy to be fair and equitable, only about 24% considered it to be effective. A recurring theme in the comments was that “the policy is fine, but it is not implemented consistently” (Q10).

Policy Orientation

Respondents at 16 of 17 institutions rated their policy as a combination type, which agreed with the policy review in 12 of 17 cases. The comments reflected significant dissatisfaction with the way in which AID policies are implemented and enforced; numerous respondents implied that their institution is primarily concerned with saving face rather than dealing with the issue.

Level of Academic Dishonesty

Nearly 62% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that academic dishonesty is a problem at their respective institutions. The 12% of respondents who disagreed believed that academic dishonesty at their university is at the same level as other institutions’. Over 53% of respondents believed that academic dishonesty is more prevalent than in the past; 37% were unsure.

Institutional Factors

Views on the contribution of institutional factors to academic dishonesty varied significantly. There were 133 comments divided into seven categories, with “policy not enforced consistently” and “faculty not supported” being the most common. “Penalties for cheating are not severe enough” (28.2%) and “policies for dealing with academic dishonesty are too time consuming to follow” (30.3%) were also popular responses. Further, 23% believed that no institutional factors contribute to an increase in academic dishonesty.

Student Factors

Nearly 41% of related comments referred to students’ lack of academic preparation or lack of understanding of the rules. Again, leniency or lack of consistency in application of the policy was a common theme, with approximately 15% of respondents indicating that this was a major contributing factor to academic dishonesty.

Institutional Response

Asked if their institution was taking “well-considered action,” 42% agreed and 31.5% did not.

Upholding Academic Honesty

Approximately 90% of respondents indicated that upholding standards of academic honesty is part of their duty to themselves, their students, and their profession. Respondents reported providing information to students regarding academic dishonesty in a variety of ways: 89.1% give written instructions at the beginning of the semester; 57.8% teach students academic conventions concerning citation and use of sources; 50.2% review the concepts of plagiarism, authorized collaboration, cheating, and so on before assessments; 45.9% refer students to the university website; 43.9% refer students to the university calendar or student handbook, and 41.8% regularly discuss the issue in class. Only 4.1% did not discuss the AID policy with students.

Further, most respondents use some kind of safeguard to discourage academic dishonesty: 73.5% closely monitor students taking quizzes or exams; 72.3% change quizzes, exams, and assignments frequently; 43.1% use the internet or software to detect plagiarism; 41.9% give different versions of quizzes or exams within the same class; 34.8% require projects or essays to be submitted in stages; and 7.4% require students to sign an academic integrity pledge on all assessed work. Only 3.9% reported not using any safeguards.

When faced with a “clear, but minor case of academic dishonesty,” 42.0% would deal with the matter informally; 36.1% would follow their institution’s policy exactly; 35.9% would seek advice before acting; 34.9% would give a reduced grade; 25.3% would refer the case to a dean, chair, or other administrator; 13.0% would give a grade of F; and 12.5% would do “other.” An additional 1.2% would ignore it. Many comments focused on the difficulty of determining intent in cases of academic dishonesty and the overly judicious and time-consuming nature of academic dishonesty proceedings.

Responses to the same question about major cases of academic dishonesty were similar, but only 3.9% would handle it informally and no respondent said that they would ignore it altogether. Conversely, the proportion of respondents who would follow institutional policy strictly rose to 69.3% and those who would refer the case to the dean, chair, or other administrator increased to 54.7%. More than 62% of respondents indicated they were satisfied with the way cases of academic dishonesty were handled by their administration. Comments, however, indicated that this satisfaction depends on the particular individual with whom the respondent has to interact when reporting academic dishonesty.

Responding to Academic Dishonesty

Of respondents, in the last two years, 61% reported suspecting academic dishonesty one to four times, while just over 55% said they had responded to student academic dishonesty one to four times. A further 21.4% indicated they had never responded, while 7.5% said they had responded more than 10 times.

“I typically respond to academic dishonesty by….” elicited fewer responses of following policy exactly in minor instances of academic dishonesty and more such responses in major cases. The number of respondents who indicated they would ignore the dishonesty rose slightly from the previous questions. However, in response to the question “Have you ever ignored a case of academic dishonesty?” more than 40% of respondents said no, but over 48% indicated that they had ignored cases of academic dishonesty when the evidence was not conclusive. Regarding whether their attitude towards academic dishonesty had ever changed, nearly 59% of respondents reported no change. Of those whose attitude had changed, the number who reported becoming more lenient was nearly equal to the number who said they had become stricter.

Colleagues’ Commitment

Although less than 10% of respondents indicated that their colleagues did not demonstrate a commitment to academic honesty, nearly 30% indicated that they did not know what their colleagues believed about academic dishonesty. In the comments, a persistent theme was that the issue is not discussed except among one’s most trusted colleagues. The final question asked whether participants believed that their institution deals with academic dishonesty consistently. Approximately 34% of respondents selected “not sure” or “agree,” with few selecting other options. This may reflect the uncertainty expressed in the comments; respondents were sure of consistency in their own academic unit but uncertain of what happens in other parts of the institution.

Policies Do Not Provide a Solution

Overall, the survey indicated that respondents believe that academic dishonesty is a problem, and that lack of student preparation and lenient, time-consuming, or inconsistently applied policies contribute to this problem. The consensus—supported by the policy review—is that the policies as written are fine but not a solution.

Discussion

This study is unique in Canadian literature for the national scope of its policy analysis and for its attempt to explore how policy interacts with faculty attitudes and influences—or does not influence—actions. The findings that faculty members often do not read policy until they feel they have no other choice and that they often rely on the opinions and advice of their colleagues parallel findings in the literature that suggest students are strongly influenced by perceptions of their peers’ behaviour regarding academic dishonesty, often cheating because they believe cheating to be commonplace (Bloodgood et al. 2008; Jurdi et al. 2011; McCabe 2001).

Prior to this study, limited research had been conducted on the topic of academic integrity policy in Canadian post-secondary institutions (Eaton 2017; Neufeld and Dianda 2007; Stoesz et al. 2019). Our study echoes previous findings insofar as the troubling degree of variability in the way that institutions approach the prevention and remedy of academic dishonesty. This study extends what has previously been found in showing that there are variable approaches to academic dishonesty within different faculties and departments at the same institution.

Faculty Attitudes

Dealing with Academic Dishonesty

Previous research on faculty attitudes towards student academic dishonesty indicates that many faculty members are reluctant to discuss the issue or deal with violations. They generally prefer to deal with instances of student cheating independently, without administrative intervention, due to time constraints and fears of lack of institutional support (Jendrek 1989; McCabe 1993; Thomas and de Bruin 2012). Therein lies the paradox of faculty attitudes towards dealing with academic dishonesty: most faculty members report that it is one of their key responsibilities, yet they often avoid confronting it.

Culture of Cheating

More than half (53.1%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that academic dishonesty is more prevalent at their institution than in the past, a belief reiterated in their comments. This accords with studies that found self-reported cheating rates of 50% to 75% over students’ academic career (Bowers 1964; McCabe and Bowers 1994; McCabe and Trevino 1996; Vandehey et al. 2007). More troubling than self-reported cheating rates are student attitudes towards academic honesty. There are fears that “views of the [cheating] behaviors seem to have changed from being ‘morally reprehensible’ to ‘morally disagreeable’ or even acceptable.. .. we may be tipping towards an unacceptable level of corruption” (Davis et al. 2009, pp. 65–66). It follows that if students do not view a particular act as wrong, they will have no compunction about doing it repeatedly. As one respondent observed, “Cheating is not stigmatized among students. .. it seems to be viewed as just another way to get through the work” (Study Participant). Note: all study participants are quoted verbatim, without corrections.

Students should not bear all of the blame for this development. Economic, social, and organizational realities combine to impinge on an institution’s ability to live up to idealistic views of integrity. Unfortunately, it is difficult to promote academic integrity as an organizational priority, or to promote it to students, if the organization is compelled, or chooses, to talk about integrity while emphasizing other concerns—such as financial issues. Students “often learn more from the example of those in positions of authority than they do from lectures in the classroom” (Bok, as cited in Thomas and de Bruin 2012, p. 15). As one respondent argued, universities often fall short of educational ideals: “Cut down the stupid size of the largest undergraduate classes and get a more person[al] contact. Give more relevance, and credit, to teaching rather than just insisting on research excellence. Provide more teacher training for professors.” (Study Participant).

The pressure on students to get high grades and a degree (resulting in many students valuing the qualification, not the education that should precede it) is cited as a key societal factor in fostering cheating (Davis et al. 2009). This view was echoed in our study. A typical reponse to the question “What are the most significant factors contributing to academic dishonesty at your institution?” was: “High standards and competition between students for limited resources is coupled with a prevalence of weak or disinterested students who view education as a commodity to be bought with tuition as opposed a life experience that needs to be earned.”

It is reasonable to assume that disengaged students are alienated from the academic culture of their institution and would, therefore, have little reluctance to cheat. The clash between the economic imperative of many students (and society as a whole) and the ideals of learning that are supposed to underpin higher education can lead to cheating: “At a time when the university student is increasingly treated as a consumer demanding value for money it would appear that subcontracting some of the work required to achieve their degree is seen as a rational choice for many consumers on campus” (Rigby et al. 2015, p. 36).

Underprepared Students

One-fifth of students graduating from postsecondary education in Canada in 2006 scored below a level 3 (basic literacy) on the International Adult Life Skills Survey (Canadian Council on Learning 2009). Numerous respondents in this study believe that students who are unprepared for university-level work tend to cheat because they do not know how, or do not care, to do otherwise. One respondent’s desired institutional changes included “creating an atmosphere in the institution that is less focused on grades and more on learning objectives .... Improved high school curriculum so students enter our university with significantly improved literacy, writing, and research skills.” (Study Participant).

The idea that international students are more likely to cheat is a contentious issue. The struggles of international students to adapt to North American educational culture have been documented in Canada: “The disproportionate number of international students accused of plagiarism or cheating on exams is raising red flags in university administrations and legal aid offices” (Bradshaw and Balujah 2018, para. 2). Our study suggests that respondents believe that international students tend to cheat more simply because they are unable to function effectively in English. Two respondents noted institutional changes that could remedy academy dishonesty. “Stop recruiting foreign students who lack English language skills,” the first advised. The second respondent was even more explicit in their comments:

Better screening of international chinese students to ensure they enter with sufficiently solid english language skills to succeed in classes. Virtually 100% of the academic dishonesty cases in my dept and in my faculty involve international chinese students. . . . when they attend the hearings, it is almost always the case that they can barely communicate in english, to the point that you worry about the process being fair if they can’t understand the questions you are asking in the hearings (Study Participant).

These responses appear to strengthen the notion that policies alone are not enough to address breaches of academic integrity in Canadian universities.

Conclusion

This study explored faculty attitudes towards student academic integrity and dishonesty at 17 Canadian universities. Although institutional policies at these institutions generally ranked highly on a policy evaluation framework based on the work of Whitley and Keith-Spiegel (2001)—and were highly regarded in principle by surveyed faculty members—a majority of faculty respondents did not believe the policies are implemented effectively. Similarly, surveyed faculty members displayed a variety of attitudes towards student academic dishonesty, with general agreement that academic misconduct is an increasing problem at their respective institutions, and that unprepared students and foreign students who struggle to communicate effectively in English are a particular concern. Additionally, according to faculty members, academic dishonesty is not consistently addressed and they are generally tired of of dealing with it. Overall, the faculty members in this study projected an attitude of frustration due to a perceived increase of incidents of academic dishonesty, the amount to time they spend dealing with academic dishonesty and inconsistent institutional responses. This study underlines that academic dishonesty is a complex issue with a variety of contributing factors and with general disagreement about how it can be managed. We conclude with a call to action for further large-scale research in Canada to better understand how institutions can move beyond policy to ensure that both academic and institutional integrity are cultivated.

References

Abeyasekera, S. (2005). Quantitative analysis approaches to qualitative data: Why, when and how? In J. D. Holland & J. Campbell (Eds.), Methods in development research: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches (pp. 97–106). Warwickshire: ITDG.

Bernard, H. R., & Ryan, G. W. (2010). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2008). Academic integrity in the 21st century: A teaching and learning imperative (Ashe higher education reports) (Vol. 33, No. 5). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bertram Gallant, T., & Drinan, P. (2008). Toward a model of academic integrity institutionalization: Informing practice in post-secondary education. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 38(2), 25–43.

Bloodgood, J. M., Turnley, W. H., & Mudrack, P. (2008) The influence of ethics instruction, religiosity, and intelligence on cheating behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9576-0.

Blum, S. D. (2009a). Academic integrity and student plagiarism: A question of education, not ethics. The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/Academic-IntegrityStud/32323/. Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

Blum, S. D. (2009b). My word: Plagiarism and college culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bowers, W. J. (1964). Student dishonesty and its control in college. New York: Bureau of Applied Research, Columbia University.

Bradshaw, J., & Balujah, T. (2018). Why many international students get a failing grade in academic integrity. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/why-many-international-students-get-a-failing-grade-in-academic-integrity/article4199683/. Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., James, C., Green, M., & Partridge, L. (2011). Core elements of exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 7(2), 3–12.

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., & van Haeringen, K. (2018). Contract cheating: A survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788.

Bretag, T. (2019). Academic integrity and embracing diversity. Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity, Calgary, Canada. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110278. Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Canadian Council on Learning. (2009). Post-secondary education in Canada: Meeting our needs? https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED525254. Accessed 01 Nov 2019.

Carpenter, D., Harding, T. Finelli, C., & Mayhew, M. (2005). Work in progress - an investigation into the effect of an institutional honor code policy on academic behavior. In Proceedings Frontiers in Education 35th Annual Conference (pp. T2D-13–T2D-14). https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2005.1611895.

Eysenbach, G. (2005). Using the internet for surveys and research. In J. G. Anderson & C. E. Aydin (Eds.), Evaluating the organizational impact of healthcare information systems (pp. 129–143). New York: Springer.

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006a). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21.

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006b). Understanding academic misconduct. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(1), 49–63.

Clarke, R., & Lancaster, T. (2006). Eliminating the successor to plagiarism? Identifying the usage of contract cheating sites. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.120.5440&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2019.

Coalter, T., Lim, C. L., & Wanorie, T. (2007). Factors that influence faculty actions: A study on faculty responses to academic dishonesty. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2007.010112.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Curtis, G., & Clare, J. (2017). How prevalent is contract cheating and to what extent are students repeat offenders? Journal of Academic Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9278-x.

Davis, S. F., Drinan, P. F., & Bertram Gallant, T. (2009). Cheating in school: What we know and what we can do. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Eaton, S. E. (2017). Comparative analysis of institutional policy definitions of plagiarism: A pan-Canadian university study. Interchange: A Quarterly Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-017-9300-7.

Eaton, S. E., & Burns, A. (2018). Exploring the intersection between culturally responsive pedagogy and academic integrity among EAL students in Canadian higher education. Journal of Educational Thought, 51(3), 339–359.

Eaton, S. E., & Edino, R. I. (2018). Strengthening the research agenda of educational integrity in Canada: A review of the research literature and call to action. Journal of Educational Integrity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0028-7.

Fink, A. (2009). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Flick, U. (2007). Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Fowler, F. J. (2002). Survey research methods: Fundamental principles of clinical reasoning & research (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Freeman, B. (2013). Revisiting the policy cycle. Association of Tertiary Education Management (ATEM): Developing policy in tertiary institutions. Melbourne: RMIT University. https://federation.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/119043/Revisiting_Policy_Cycle_2013_BFreeman.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Genereux, R. L., & McLeod, B. A. (1995). Circumstances surrounding cheating a questionnaire study of college students. Research in Higher Education, 36, 687–704.

Gibbs, G. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Glendinning, I. (2014). Responses to student plagiarism in higher education across Europe. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 10(1), 4–20.

Gorard, S. (2001). Quantitative methods in educational research: The role of numbers made easy. New York: Continuum.

Grbich, C. (2007). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hall, S., Moskovitz, C., & Pemberton, M. A. (2018). Attitudes toward text recycling in academic writing across disciplines. Accountability in Research, 25(3), 142–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2018.1434622.

Howard, R. M. (2016). Plagiarism in higher education: An academic literacies issue? – Introduction. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of Academic Integrity (pp. 499–501). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Howard, R. M. (2000). Sexuality, textuality: The cultural work of plagiarism. College English, 62(4), 473. https://doi.org/10.2307/378866.

Hunt, R. (2010). Four reasons to be happy about internet plagiarism. In J. Boss (Ed.), Think: Critical thinking for everyday life (pp. 367–369). Retrieved from http://people.stu.ca/~hunt/www/think4r.pdf. Accessed 01 Nov 2019.

International Center for Academic Integrity. (2012). Academic Integrity Rating System. https://academicintegrity.org/academic-integrity-rating-system-ai/. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Jendrek, M. P. (1989). Faculty reactions to academic dishonesty. Journal of College Student Development, 30, 401–406.

Jordan, A. E. (2001). College student cheating: The role of motivation, perceived norms attitudes and knowledge of institutional policy. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 233–247.

Jurdi, R., Hage, H. S., & Chow, H. P. H. (2011). Academic dishonesty in the Canadian classroom: Behaviours of a sample of university students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 41(3), 1–35.

Kier, C. A. (2013). Is it still cheating if it’s not done on purpose? Accidental plagiarism in higher education [PowerPoint presentation]. Paper presented at the 2013 Hawaii International Conference on Education, Honolulu, HI. https://auspace.athabascau.ca/handle/2149/3316. Accessed 25 Sept 2019.

Kier, C. A. (2019). Plagiarism intervention using a game-based tutorial in an online distance education course. Journal of Academic Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09340-6.

Lancaster, T. (2019). Social media enabled contract cheating. Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity, Calgary, Canada. https://www.slideshare.net/ThomasLancaster/social-media-enabled-contract-cheating-canadian-symposium-on-academic-integrity-calgary-18-april-2019. Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Levin, P. (2003). Beat the witch-hunt! Peter Levin’s guide to avoiding and rebutting accusations of plagiarism, for conscientious students. http://student-friendly-guides.com/wp-content/uploads/Beat-the-Witch-hunt.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Levin, P. (2006). Why the writing is on the wall for the plagiarism police. http://student-friendly-guides.com/wp-content/uploads/Why-the-Writing-is-on-the-Wall.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Leung, C. H., & Cheng, S. C. L. (2017). An instructional approach to practical solutions for plagiarism. Universal Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2017.050922.

Liu, D. (2005). Plagiarism in ESOL students: Is cultural conditioning truly the major culprit? ELT Journal. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci043.

Mahmud, S., Bretag, T., & Foltýnek, T. (2019). Students’ perceptions of plagiarism policy in higher education: A comparison of the United Kingdom, Czechia, Poland and Romania. Journal of Academic Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9319-0.

Martin, B. (1994). Plagiarism: A misplaced emphasis. Journal of Information Ethics, 3(2), 36–47. https://documents.uow.edu.au/~bmartin/pubs/94jie.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2019.

McCabe, D. L. (1993). Faculty responses to academic dishonesty: The influence of student honor codes. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991924.

McCabe, D. L. (2001). Cheating: Why students do it and how we can help them stop. American Educator. http://www.aft.org/newspubs/periodicals/ae/winter2001/mccabe.cfm. Accessed 12 Oct 2019.

McCabe, D. L. (2005). It takes a village: Academic dishonesty & educational opportunity. Liberal Education, 91(3), 26–32.

McCabe, D. L. (2016). Cheating and honor: Lessons from a long-term research project. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 187–198). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

McCabe, D. L., & Bowers, W. J. (1994). Academic dishonesty among males in college: A thirty year perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 35(1), 280–291.

McCabe, D. L., & Drinan, P. (1999). Toward a culture of academic integrity. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 46(8), B7–B10.

McCabe, D. L., & Pavela, G. (2004). Ten (updated) principles of academic integrity: How faculty can foster student honesty. Change. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091380409605574.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1996). What we know about cheating in college: Longitudinal trends and recent developments. Change, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1996.10544253.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (1999). Academic integrity in honor code and non-honor code environments: A qualitative investigation. The Journal of Higher Education, 70(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1999.11780762.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_2.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what educators can do about it. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Morris, E. J., & Carrol, J. (2016). Developing a sustainable holistic institutional approach: Dealing with realities “on the ground” when implementing an academic integrity policy. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 449–462). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Neufeld J., & Dianda, J. (2007). Academic dishonesty: A survey of policies and procedures at Ontario universities. http://www.queensu.ca/secretariat/senate/Nov15_07/COUPaper.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2019.

Newton, P. (2018). How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education and is it increasing? A systematic review. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00067.

Panning Davies, L. J., & Moore Howard, R. (2016). Plagiarism and the internet: Fears, facts, and pedagogies. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 591–606). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Park, C. (2003). In other people’s words: Plagiarism by university students: Literature and lessons. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301677.

Pavela, G. (n.d.). Educational resources: Stages of institutional development. https://academicintegrity.org/educational-resources/. Accessed 17 Sept 2019.

Pavela, G., & McCabe, D. L. (1993). The surprising return of honor codes. Planning for Higher Education, 21(4), 28–33.

Rigby, D., Burton, M., Balcombe, K., Bateman, I., & Mulatu, A. (2015). Contract cheating & the market in essays. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 111, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.019.

Scanlon, P. M., & Neumann, D. R. (2002). Internet plagiarism among college students. Journal of College Student Development, 43(3), 374–385.

Stearns, S. A. (2001). The student–instructor relationship’s effect on academic integrity. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 275–285.

Stoesz, B., Eaton, S. E., Miron, J. B., & Thacker, E. (2019). Academic integrity and contract cheating policy analysis of colleges in Ontario, Canada. International Journal for Educational Integrity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-019-0042-4.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2008). Plagiarism, the Internet and student learning: Improving academic integrity. New York: Routledge.

Taylor-Powell, E., & Renner, M. (2003). Analyzing qualitative data. Retrieved https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0145/8808/4272/files/G3658–12.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2019.

Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292430.

Thomas, R. M. (2003). Blending qualitative and quantitative research methods in theses and dissertations. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press/Sage.

Thomas, A., & De Bruin, G. P. (2012). Student academic dishonesty: What do academics think and do, and what are the barriers to action? African Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.15249/6-1-8.

Tysome, T. (2006). English deficit leads to cheating. Times Higher Education Supplement. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk. Accessed 25 Sept 2019.

U15. (n.d.). Our members. Retrieved from http://www.u15.ca/our-members. Accessed 25 Sept 2019.

Universities Canada.(n.d.). Member universities. Retrieved from https://www.univcan.ca/universities/member-universities/. Accessed 25 Nov 2019.

Vandehey, M. A., Diekhoff, G. M., & LaBeff, E. E. (2007). College cheating: A twenty-year follow-up and the addition of an honor code. The Journal of College Student Development. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0043.

Walker, A. L. (2008). Preventing unintentional plagiarism: a method for strengthening paraphrasing skills. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35, 387–395.

Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2001). Academic integrity as an institutional issue. Ethics & Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_9.

Whitley Jr., B. E., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic dishonesty: An educator’s guide. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacLeod, P.D., Eaton, S.E. The Paradox of Faculty Attitudes toward Student Violations of Academic Integrity. J Acad Ethics 18, 347–362 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09363-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09363-4