Abstract

Although extant research demonstrates the negative impact of overparenting on child well-being, there remains a paucity of evidence on the effect of overparenting on the parents’ own well-being. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of overparenting on parental well-being, and to explore the mechanisms through which overparenting influences the well-being of working mothers, particularly among established adults. Thus, we examined the serial mediation effects of perceived stress and family-to-work conflict (FWC) in overparenting and well-being linkage. With this aim, the data were collected from working mothers (N = 258) aged between 30 and 45, a period of in their lifespan generally characterized by efforts devoted to career and care. Via serial mediation analyses, the findings postulate that (a) overparenting relates to the well-being and perceived stress of working mothers, (b) perceived stress (both individually and jointly with FWC) mediates the relationship between overparenting and well-being, and (c) perceived stress and FWC serially mediate the association between overparenting and well-being. The findings provide evidence related to the well-being experiences of established adulthood women in struggling their career-and care crunch from a perspective of overparenting, stress, and family-to-work conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Established adulthood, as a new theoretical conceptualization pioneered by Mehta et al. (2020), refers to the period between the ages of 30–45, when most individuals are deeply involved in developing their careers while tending to responsibilities involved in their partnerships and nurturing their children. This period is distinguished from the emerging adulthood and midlife periods in terms of well-being, physical, and mental health. More specifically, it involves a developmental challenge known as the ‘Career-and-Care-Crunch,’ in which individuals struggle to fulfill the responsibilities arising from the competing demands of work and family (Mehta et al., 2020). Owing to traditional gender roles that prescribe one gender more responsibility for childcare and household tasks (Blackstone, 2003), women might experience this challenge more than men (Mehta et al., 2020). Given that sociocultural factors may influence the timing and intensity of developmental demands, it is critical to examine the variations in the experience of established adulthood across different populations and cultural contexts (Mehta et al., 2020).

The current study responds to Mehta et al.’s call in delineating variations in the experience of established adulthood among Turkish working mothers. Turkey is a majority Muslim country, with 22.7% of the total population aged between 30 and 44 years of age (www.data.tuik.gov.tr), and a total labor force participation of 52.9%. Of this labor force participation, 34.3% are taken up by women while 65.7% are taken up by men (www.dataworldbank.org). Turkey continues to endorse traditional gender roles (Caner et al., 2016; Sakallı, 2002), with highly patriarchal social and family structures (Kandiyoti, 1995). In general, Turkish women’s participation in the workforce is encouraged unless it interferes with family life (Aycan, 2004; Esmer, 1991). In these respects, studying the career-and-care-crunch phenomenon among working Turkish mothers may be particularly informative. Specifically, the current study focuses on the associations between overparenting, stress, family-to-work conflict (FWC) and well-being in the established adulthood period.

Overparenting, which is colloquially known as helicopter parenting (Cline & Fay, 1990; LeMoyne & Buchanan, 2011; McGinley & Davis, 2021; Segrin et al., 2022), refers to the engagement of parents in developmentally inappropriate practices toward their children that take the form of excessive involvement in decision making, problem solving, and risk aversion (Segrin et al., 2012). Considerable research links overparenting with negative child outcomes such as poorer mental health, lower self-efficacy, and ineffective coping skills (Givertz & Segrin, 2014; Leung, 2020; Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012; Reed et al., 2016; Schiffrin et al., 2014, 2015, 2019; Segrin et al., 2012, 2013, 2015; Winner & Nicholson, 2018; see Metin-Orta & Miski-Aydın, 2020 for a review), as this type of parental involvement limits children’s autonomy, sense of competence, and responsibility (Odenweller et al., 2014; Schiffrin et al., 2014, 2015, 2019; Segrin et al., 2015, 2022).

In contrast, there is a dearth of evidence that speaks to associations of overparenting with parents’ own well-being. Consistent with the established adulthood construct of Mehta et al. (2020), scholars have shown that conflict between work and family demands (Bayhan-Karapinar et al., 2020; Hagqvist et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2016) and perceived stress (Kapoor et al., 2021; Schwepker et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2016) are predictors of poor well-being. Strong links between perceived stress and family to work conflict (FWC) (Voydanoff, 2005; Zhou et al., 2018) further suggest that these two variables work together in transmitting the effect of overparenting to well-being, as serial mediators.

The current study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, to the authors' knowledge, this is a pioneering study that investigates the effects of overparenting on parents’ well-being rather than on the child outcomes. Second, the majority of overparenting studies have been conducted on samples from Western societies (Ertuna, 2016; Odenweller et al., 2014; Pistella et al., 2020). Given the relatively limited parenting research in non-Western sociocultural contexts (e.g., Leung, 2020), the examination of overparenting in relation to parents’ own well-being in Turkey may prove particularly useful in that overparenting can be considered a common, natural and even valued attribute for Turkish mothers (Ertuna, 2016). Lastly, the current study addresses the need for research on the stress experienced by established adults trying to handle work and family demands (Mehta et al., 2020).

Theoretical Framework and Development of Hypotheses

Overparenting and Well-being

Overparenting is defined as “developmentally inappropriate parenting that is driven by parents’ overzealous desires to ensure the success and happiness of their children, typically in a way that is construed largely in the parents’ terms, and to remove any perceived obstacles to those positive outcomes” (Segrin et al., 2012, p. 238). These parents are highly involved in their children’s routines; for instance, by offering excessive advice, providing unnecessary tangible assistance and problem solving for their children, protecting them from risks, and managing their emotions and moods (Segrin et al., 2012). These overly effortful practices are considered as benevolent and loving but are in fact misguided parental attempts to promote a child's personal and academic success (Locke et al., 2012).

The limited number of studies that examine effects of overparenting on parental outcomes, show that indulgent (Cui et al., 2019) or intensive parenting (Rizzo et al., 2013) mostly yield adverse effects on parental well-being such as higher levels of stress, depression, and lower levels of life satisfaction. These effects may be reflections of the neglect of personal needs (Rehm et al., 2017), including sleep, personal time, and own interests (Becker & Moen, 1999; Bianchi et al., 2006; Fingerman et al., 2012; Maume, 2006). A qualitative study also found that Israeli parents reported higher levels of dissatisfaction over providing intense support to their grown children (Levitzki, 2009). Thus, it is expected that

Hypothesis 1:

Overparenting negatively relates to the well-being of working mothers in established adulthood.

The Associations among Overparenting, Perceived Stress, FWC and Well-Being

Scholars have emphasized the need for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that link parenthood and well-being (Nelson et al., 2014). Parental perceived stress may be one potential mechanism linking overparenting to lower well-being as previous research has demonstrated that the experience of stress among parents is negatively associated with their psychological well-being (Brown et al., 2020; Desmarais et al., 2018; Kapoor et al., 2021; Skok et al., 2006). For instance, mothers perceive taking care of their child/children as being more stressful compared to working (Guendouzi, 2005). Similarly, parental overinvestment of time, energy, and resources in their children, and protection from any potential obstacles and consequences of misbehavior may be stressful and promote psychological distress (Rehm et al., 2017). So, it is expected that

Hypothesis 2:

Perceived stress mediates the link between overparenting and the well-being of working mothers in established adulthood.

The link between overparenting and the well-being of working mothers may also be explained with FWC. Family to work conflict, “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77), occurs when the time devoted or strain created by the family environment interferes with the individual's ability to engage effectively in job roles (Eby et al., 2005). FWC is consistent with the notion of scarcity in Role Strain theory (Goode, 1960) which proposes that when individuals are trying to fulfill the requirements of multiple roles it will lead to a scarcity of resources due to the limited availability of time and energy spread among roles (Barnett & Gareis, 2006). Evidence has linked parental demands, the number of children, and the stressors of family life with FWC (Demerouti et al., 2012). Evidence has also linked FWC to a number of negative outcomes at both individual (e.g., psychological well-being, stress, life satisfaction, psychological strain, physical and mental health) and organizational levels (e.g., job satisfaction, task performance, organizational commitment) (Aycan & Eskin, 2005; Byron, 2007; Dettmers et al., 2016; Ford et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2006; Tayfur Ekmekci et al., 2021). Hence, it is reasonable to expect that overparenting practices (e.g., doing more of the parenting and household tasks such as taking children to extracurricular activities, spending more time and energy on children’s projects, and handling the obstacles the children face) may exacerbate FWC and, thus, may result in lower levels of well-being. So, it is expected that

Hypothesis 3:

FWC mediates the link between overparenting and the well-being of working mothers in established adulthood.

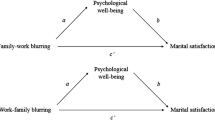

In addition, other evidence demonstrates that perceived stress and FWC are associated such that individuals experiencing psychological stress also report higher levels of conflict between work and family domains (Voydanoff, 2005). Hence, a serially mediated relationship (see Fig. 1) is also possible such that to the extent that as overparenting increases perceived stress, it also exacerbates FWC, which in turn lowers the well-being of working mothers. Thus, it is expected that

Hypothesis 4:

Perceived stress and FWC serially mediate the link between overparenting and the well-being of working mothers in established adulthood.

Contextual Background of Turkey

Turkey provides a pertinent context for examining the effects of overparenting, FWC, and perceived stress on the well-being of working mothers. The endorsement of traditional gender roles (Caner et al., 2016; Sakallı, 2002) constitutes a potential barrier to women’s career advancement in Turkey, where women’s participation in the workforce is encouraged unless it interferes with family life (Aycan, 2004; Esmer, 1991). The findings of Sakallı-Uğurlu et al. (2018) reveal that the familiar sexist ideology, emphasizing men’s power in contrast to the emphasis placed on motherhood and faithfulness themes for women, continues to be embraced among college students. These cultural expectations may result in higher levels of FWC among working mothers in Turkey. Therefore, the findings of this study using a non-Western sample may contribute to bridging the gaps of knowledge regarding work/family issues from a cultural perspective.

Method

Participants and Procedure

As the purpose of this study was to explore the associations of overparenting, family-to-work conflict, and well-being for the individuals who are in their established adulthood period, several criteria were adopted in the sample selection: (i) to be in established adulthood (aged ranging from 30 to 45); (ii) to be employed at a full-time job; and (iii) to have at least one child aged 10 or older (to ensure the appropriateness of typical overparenting items, such as managing peer influences, friendships, community/sports engagements, academic responsibilities, and adjustment to the environment).

Upon obtaining approval from the Ethical Committee, we recruited participants via social media. The participants were recruited on a convenience sampling methodology through an online survey. The authors posted the survey link on their professional social media network. As the questionnaires were all conducted in Turkish, there was information given prior to the link stating that all participants must be native Turkish speakers. Approximately a total of 500 posts were shared, and 321 respondents provided data for the survey (74%). First, we explained the study's purpose and assured participants’ confidentiality. After the initial data screening for the fit of the inclusion criteria and checking missing data frequencies (higher than 5% of the items), the final sample size was reduced to 258. The age range of the participants was between 30 and 45 years with an average of 36.2 years (SD = 12.57). 57% of the participants were university graduates and among those 31.3% held postgraduate degrees. Among the respondents, 86% of the participants were married. The participants were working in various industries including education, health and insurance, finance, and engineering. The average tenure was 12.7 (SD = 7.14). Most of the participants (62.7%) were working in non-managerial positions. The number of the children that the respondents had ranged from 1 to 3. While 41% of them had only one child, 48% had 2 children. The average mean age of the oldest child was reported as 14.2 (SD = 5.86).

The participation was voluntary and no incentives were given for participation. The participants provided informed written consent consistent with ethical research standards. The data collection took place between the periods of February–April 2021.

Measures

The current study included self-reported scales of overparenting, family-to-work conflict, perceived stress, and employee well-being in addition to demographic variables of gender, age, education, profession, sector, marital status, number of children, age of the older child, and tenure (see Appendix for the complete set of study items).

Overparenting

Overparenting behaviors were measured by the 15-item helicopter parenting inventory (HPI) developed by Odenweller et al. (2014). This instrument was originally designed to assess the apprehension of emerging adult children’s parents toward overparenting behaviors (e.g., ‘My parent tries to make all of my major decisions’). Scholars argue that employing mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions are also important (Burke et al., 2018; Somers & Settle, 2010). Because the current study was designed to assess parental perceptions of overparenting practices, all items were reworded to reflect how parents respond to their child. The participants indicated their level of agreement with statements relating to their experience (e.g., ‘I overreact when my child encounters a negative experience,’ ‘I try to make all major decisions of my child’). The response format was a Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The original scale was reported to have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 (Odenweller et al., 2014) and high construct validity for both mothers and fathers ranging from 0.62 to 0.69 (Pistella et al., 2020). The scale has also been used in several studies including Italian (Pistella et al., 2020, 2021), Portuguese (Borges et al., 2019), and Turkish samples (Ertuna, 2016; Komurcu-Akik & Alsancak-Akbulut, 2021). The Turkish translation and adaptation of the scale were conducted by Ertuna (2016). The previous studies revealed that the Turkish adaptation of the HPI was reliable and valid with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.77 (Ertuna, 2016) and 0.71 (Komurcu-Akik &Alsancak-Akbulut, 2021). In the current study, items were added to form a composite score of overparenting in which higher scores represent higher levels of the construct. The Cronbach Alpha was reported as 0.77.

Family-to-Work Conflict

This was measured by the five-item family-work conflict scale developed by Netemeyer et al. (1996). The participants were requested to indicate their level of agreement on items such as ‘My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime.’ The response format ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. Higher scores represent higher levels of inter-conflict between the family and work domains. Although the Netemeyer et al (1996) scale also has a work–family conflict scale (e.g., ‘My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill family duties’), we have only included the FWC subscale in the current study as the family demands are positively related to FWC (Lu et al., 2006), and we are particularly interested in how the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by, overparenting (i.e., rather than working conditions) related to the well-being of working mothers. The Turkish adaptation of the scale was conducted by Derya (2008). The Cronbach alpha was 0.86 in the current study.

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress levels were measured by the 14-item perceived stress scale (PSS) developed by Cohen et al. (1983). This scale is a widely used instrument for assessing perceived stress. The participants were asked to indicate how often they had felt or thought in a certain way during the last month (e.g., ‘In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed’). The response format was from never (1) to very often (5). Higher scores represent higher levels of perceived stress. The Turkish adaptation and validation were done by Çelik Örücü and Demir (2011). The Cronbach alpha was 0.84 in the current study.

Well-being

We administered Zheng et al.’s (2015) 18-item employee well-being questionnaire which adopts the call for capturing multiple facets of well-being (Page & Vella-Brodrick, 2009; see Zheng et al., 2015 for a review). Representing the hedonic perspective, the life well-being (LWB) scale reflects subjective well-being, and it refers to the happiness in one’s life (e.g., Most of the time, I do feel real happiness); the psychological well-being (PWB) scale represents the eudaimonic perspective and contains personal growth, autonomy, self-acceptance, and environmental mastery (e.g., ‘I feel I have grown as a person’) and the workplace well-being (WWB) scale captures work-related affect and work satisfaction (e.g., ‘In general, I feel fairly satisfied with my present job’). The Turkish version of the scale was obtained from Bayhan-Karapinar et al. (2020) with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.92. The response format ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. Higher scores represent higher well-being scores. Zheng et al (2015) also stated that the scale could be used as single factor indicating general well-being and reported the reliability coefficients as 0.87, 0.87, 0.84, and 0.91 for the LWB, PWB, WWB, and overall well-being scale, respectively. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated as 0.89, 0.90, 0.79, and 0.91, respectively.

Data Analysis Design

The main outcome variable of the study was well-being. The predictor variable was overparenting, the mediating variables were perceived stress and FWC. Following descriptive analysis and normality assumption checks, Confirmatory Factor analyses were conducted to ensure the factorial structure of the study variables. The study hypotheses were tested with serial multiple mediation analysis. This model with two serial mediators allowed us to explore both the direct and indirect effects of overparenting on employee well-being while isolating each mediator’s (perceived stress and FWC) indirect effect and also testing the total indirect effect of overparenting (Van Jaarsveld et al., 2010, p. 1496).

Preliminary Analysis

Initially, the data were checked for univariate and multivariate normality. Univariate normality was assessed with skewness and kurtosis values and multivariate normality was inspected with Mardia’s coefficient of value. All the skewness and kurtosis values were found to be less than ± 2 (Tabachnick et al., 2007) and no violation for multivariate normality was detected. As a second step, we checked the variance inflation factor values for multi-collinearity threat. The variance inflation factor values were 1.17–1.38 signaling no multi-collinearity.

Subsequently, we conducted Harman’s one factor test for testing common method bias as the study utilized a cross-sectional research design. The results of the unrotated factor analysis solution were examined. The analysis extracted 11 factors with the variance of 21.76% extracted by the first factor, which is less than the acceptable limit of 50% (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Therefore, we concluded that no general factor was apparent.

As a second remedy, we also conducted a series of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for examining the fit of the factorial structures. Several statistics such as Chi-Square, goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) were examined to assess the adequacy of the measurement model. The CFA for the 3-factor structure (overparenting, perceived stress, FWC) with 30 items showed three items (items 5, 9, and 12) from the overparenting scale either failed to load significantly or had low factor loadings. The three-factor model, CFA model, without those three items provided an acceptable fit to data [χ2 (321) = 873.12, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.07] with significant loadings that ranged between 0.48 and 0.91.

For the well-being scale, we performed two CFA’s. In the first model, we tested the three-factor structure of the well-being scale. After eliminating one item from psychological well-being (due to very low factor loading), the model yielded a satisfactory fit [χ2 (132) = 504.99, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.07; BIC = 738.21]. We also tested the second-order factor structure of the scale [χ2 (133) = 504.99, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, BIC = 737.98]. Collectively, these findings align with those of Zheng et al. (2015) that this scale can be used as an overall dimension as well as a three-dimensional instrument to capture all other facets.

The composite scores were calculated by averaging the responses given to scale items. Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all the composite scores. Correlations provide initial support for the proposed hypotheses, e.g., overparenting was positively associated with perceived stress (r = 0.14, p < 0.05), and FWC (r = 0.13, p < 0.05), and negatively associated with well-being (r = − 0.22, p < 0.001). Perceived stress was positively associated with FWC (r = 0.29, p < 0.001). Furthermore, well-being was negatively correlated with FWC (r = − 0.32, p < 0.001) and perceived stress (r = − 0.61, p < 0.001).

Hypotheses Testing

The hypotheses were tested with a serial multiple mediation analysis (model 6) using the SPSS PROCESS macro of Hayes (2018). As can be seen in Fig. 1, overparenting was entered as the independent variable (X), and well-being as the dependent variable (Y). We assigned perceived stress as Mediator 1 and FWC as Mediator 2. Marital status, the number of children, the age of the oldest child, and their position were entered as covariates. Table 2 displays the regression coefficients, standard errors, and model summary statistics for the serial multiple mediation model. Among the control variables, the participant’s marital status was negatively correlated with PSS (b = − 0.234, p < 0.05), and the number of children was negatively associated with PSS (b = − 0.126, p < 0.05) but positively associated with FWC (b = 0.236, p < 0.05). Furthermore, the participant's job position was negatively related with well-being (b = − 0.265, p < 0.05) indicating that participants in managerial positions report higher levels of well-being.

After controlling the covariates, the analysis initially tested the total effect of overparenting on well-being. The result revealed a negative total effect of overparenting on well-being (total effect: b = − 0.405, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001) confirming Hypothesis 1. When the two mediators were added to the analysis, the direct effect of overparenting on well-being was still significant (direct effect: b = − 0.203, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05). Overparenting was a positive predictor of PSS (b = 0.199, SE = 0.07, p < 0.005) but not FWC (b = 0.132, SE = 0.09, n.s.). Furthermore, PSS was found as a significant positive predictor of FWC (b = 0.388, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) (see Table 2).

Hypothesis 2 states that PSS mediates the linkage between overparenting and well-being. The significance of the indirect effects was examined with 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) based on 5000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, 2018). As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect (Ind 1) was significant (b = − 0.169, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.3031, − 0.0472]), suggesting that PSS mediated the linkage between overparenting and well-being. Likewise, Hypothesis 3 states that FWC mediates the linkage between overparenting and well-being. According to the test results, the 95% confidence interval of this indirect effect (Ind 2) contained zero, and thus, this hypothesis was not supported (b = − 0.020, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.0596, 0.0097]).

Finally, Hypothesis 4 states that PSS and FWC serially mediate the relationship between overparenting and well-being. As shown in Table 3, when both PSS and FWC were considered as serial mediators (Ind 3), they significantly, sequentially mediated the relationship between overparenting and well-being (b = − 0.0119, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.0373, − 0.0002]). Thus, this hypothesis was confirmed. Overall, the results, illustrated in Fig. 2, are such that FWC only jointly (with PSS) mediated the relationship between overparenting and well-being, whereas PSS both independently and jointly mediated the relationship between overparenting and well-being.

Discussion

While the emerging literature (e.g., LeMoyne & Buchanan, 2011; Segrin et al., 2012, 2013) has been largely focused on overparenting and its impact on children’s well-being, less is known about the influence of overparenting on the parents’ own well-being. The current study addressed this gap by exploring the effects of perceived stress and FWC in the association between overparenting and well-being of Turkish working mothers during the established adulthood period. A serial mediation model was tested to examine the relationships with the data gathered from Turkish full-time working mothers with children over 10 years old.

The findings of the study overall provided support for the hypotheses that overparenting is associated with poor well-being among working mothers (Hypothesis 1). This finding corroborates previous evidence that link parenting experience, rather than specifically overparenting, with higher levels of depression (Evenson & Simon, 2005), and lower levels of happiness (Nelson et al., 2014; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003). This finding also converges with prior research that associates specific overparenting practices such as indulgent (Cui et al., 2019) or intensive ways of parenting (Rizzo et al., 2013) with negative mental health outcomes. In particular, the parental practices of giving children more resources than they need (‘giving too much’), doing things for their children even when they are capable of doing them themselves (‘over-nurturance’), and imposing few rules toward their children (‘soft-structure’) may lead parents to neglect their own needs (Rehm et al., 2017), with a consequent deterioration of their well-being.

More importantly, the findings revealed that perceived stress mediates the relationship between overparenting and well-being (Hypothesis 2). Such that, overparenting positively predicted perceived stress which in turn was associated with lowered well-being. Likewise, the previous studies have demonstrated negative associations between the experiences of stress and well-being among parents (Brown et al., 2020; Desmarais et al., 2018; Kapoor et al., 2021; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003; Skok et al., 2006). This finding is consistent with arguments advanced by Rizzo et al. (2013) that if mothers perceive parenting as difficult and/or challenging, these perceptions may increase stress due to the perceived demands of parenting (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and decrease well-being due to lower feelings of competence (Deci & Ryan, 2008). As overparenting involves parental practices of excessive guidance, support, and problem solving to their children, the findings pertaining to higher levels of perceived stress and lower well-being among those mothers are not surprising.

Also consistent with our expectations and prior evidence (Amstad et al., 2011; Aycan & Eskin, 2005; Tayfur Ekmekci et al., 2021) was the finding that higher levels of FWC were associated with lower levels of well-being. One may argue that the conflict between family and work demands could be more negatively experienced by women living in a cultural context that mostly endorses traditional gender roles and low gender egalitarianism (Fikret-Paşa et al., 2001; Sakallı-Ugurlu et al., 2021). In such cultural contexts, the well-being of the individuals is mostly determined by the egalitarian relationships in the family (Aycan & Eskin, 2005). As professional women in Turkey are assumed to endorse family responsibilities as being more central to their lives (Aycan, 2004), those women could experience career-to-care-crunch to a greater extent while climbing the career ladder and caring for their families in the established adulthood period.

However, contrary to our expectations, the findings did not support the mediating role of FWC on overparenting and well-being (Hypothesis 3), as the link between overparenting and FWC was not significant. One reason for the lack of association between overparenting and FWC may concern socially prescribed parenting expectations for women in Turkish culture where womanhood is perceived to be equivalent to motherhood (Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2018, 2021). Accordingly, women are expected to meet all of their obligations with respect to their families, and to sacrifice their own needs for their families and children (Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2021; Tayfur Ekmekci et al., 2021). In other words, to the extent that working mothers may have internalized ‘overparenting’ as their ascribed role, separate and more important than their career, it would be reasonable to expect low levels of associations between overparenting and FWC (Tayfur Ekmekci et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, when perceived stress was taken into consideration, the findings provided support for the serial mediational effects of perceived stress and FWC (Hypothesis 4). That is to say, to the extent that overparenting predicted perceived stress positively, it was in turn associated with higher levels of FWC and subsequently lower levels of well-being. The absence of a direct association between overparenting and FWC but the presence of an indirect association may be consistent with our earlier speculation. Working mothers who struggle to fully internalize the ascribed role expressed in overparenting, or those who have a lower level of parental self-efficacy, may experience greater stress as a result of overparenting which may in turn elevate FWC. These speculations can only be addressed in future research where the extent to which working mothers internalize ascribed gender roles as individuals are also measured. Yet, these findings are aligned with previous work on Turkish samples regarding the experience of conflict in work and family domains and lower well-being (e.g., Aycan & Eskin, 2005; Bayhan-Karapinar et al., 2020; Tayfur Ekmekci et al., 2021).

Collectively, the findings supported the hypotheses that we generated mostly based on evidence collected in the Western sociocultural contexts that overparenting among working mothers is likely to affect well-being negatively. In that respect, it is important to note these expectations for the most part also held in a sample of working mothers in the cultural context of Turkey. Overparenting may be more consistent with the ‘view of an ideal mother’ who has internalized the socially ascribed role for mothering in the Turkish cultural context. As others have suggested, and consistent with data from other collectivistic cultures, parental overcontrol is prevalent and normative to reinforce close family ties (Chen-Bouck & Patterson, 2017; Dwairy & Achoui, 2010; Kağıtçıbaşı, 2007). Furthermore, because overparenting also involves a parental show of support, affection, and warmth toward children regardless of age (Nelson et al., 2014; Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012), it may not be inherently negative on children’s well-being in this cultural context (Kömürcü-Akik & Alsancak-Akbulut, 2021).

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to make causal inferences. The associations are only suggestive of potential causal links. Future research with longitudinal designs and/or random assignment can best address whether the interpretations we have offered for those associations are viable in the ‘causal’ sense. Moreover, reciprocal effects between parents and children are also possible such that the needs and abilities of the children may lead mothers to engage in more overparenting behaviors (Gagnon et al., 2020). Nevertheless, our examples emphasized cases where effects did not describe additional influences on parental reports of either overparenting, perceived stress, or FWC such as children’s difficult temperament or dysfunctional marriage. It is conceivable that if those influences were also measured in this study, the effects we have observed would be different. However, our goal was not to delineate the factors that impinge on overparenting (i.e., antecedents) in a population of working mothers.

Third, the data include self-report measures only, and hence, common-method-variance may have to lead stronger correlations. Although several precautions and remedies were taken (e.g., different response formats for scales, Harman’s test, Confirmatory Factor Analysis), future research on these issues needs to invest in measurement protocols with multiple informants (e.g., other family members within the family, the child, and the employee’s supervisor at work) and/or use parent–child dyads. However, several researchers have also pointed out the difficulty and sensitivity of gathering information from other family members regarding topics of family–work conflict (Touliatos et al., 2000). Future research could also benefit from qualitative research with semi-structured maternal interviews rather than questionnaires alone to gain additional insight. Fourth, future studies could examine the fathers’ overparenting tendencies in addition to maternal overparenting. It is possible that there are cohort effects between paternal and maternal overparenting tendencies, as recent evidence suggests that men, particularly the younger generations (millennials), like women, have the desire to be involved with their children and are also trying to balance family and work responsibilities (Liss & Schiffrin, 2014, p. 6).

Fifth, the study used a Western-developed measure of helicopter parenting scale by Odenweller et al. (2014). Even though it has shown adequate construct validity, the number of cross-cultural validation studies is relatively low.

Sixth, the educational level of women in this sample was higher than the overall education level of mothers in Turkey. However, the sample’s educational level was representative of working women since the Turkish Statistical Institute [TUIK], 2020) reports that 54.6% of the women participating in the workforce hold a graduate and/or post-graduate degree. Importantly, prior studies have shown that most helicopter parents are well-educated (Odenweller et al., 2014). Similarly, the sample of the study merely included working mothers, thus, limiting the generalizability of the findings to parents who do not work. Future studies would greatly benefit from diverse samples (e.g., low-educated and/or non-working parents) drawn from additional cultural contexts to inform impact of overparenting on parental well-being with respect to cultural similarities and differences.

Implications and Conclusions

The study contributes to the limited research in established adulthood and parental well-being in a non-western sociocultural context. Deepening our understanding of these constructs may promote well-being and positive outcomes both for children and their parents, and inform social policies or therapeutic interventions for parents. From a practical standpoint, the study findings encourage inclusion of additional modules into parenting training programs that identify and remedy developmentally appropriate parental skills that impact parents’ perceived stress and well-being positively (Rehm et al., 2017). For instance, they could include typical interactions where overparenting is common and suggest alternative ways (i.e., role play) to diminish the tendency to be a helicopter parent (Rehm et al., 2017).

Moreover, those supportive programs might encourage mothers to evaluate their behaviors with respect to overparenting, to reduce hovering, to learn to recognize the distinction between the needs and the wants of their children, offer choices, and assume personal responsibility for actions and/or mistakes. Furthermore, in their established adulthood parents who engage in overparenting, practices might benefit from stress reducing programs and relaxation exercises. Organizations could provide training that promotes gender equality and division of labor in the family (Aycan & Eskin, 2005). Furthermore, managers may use family-friendly policies to support work–life balance such as parental leave, job sharing, schedule control, and flexible work arrangements for their employees (Fuller & Hinch, 2008; Kelly et al., 2011). The successful implementation of such programs has the potential to improve parenting skills, parent–child communication, family work interference, stress, and well-being (Cui et al., 2019; Kelly et al., 2011).

Taken together, this study posed a unique question reframing whether overparenting practices would place working mothers at risk for a poorer sense of well-being. The findings contribute to the current literature by demonstrating the associations among overparenting, parental stress, FWC, and the well-being of Turkish mothers in established adulthood. Likewise, the critical direct and indirect roles of perceived stress through FWC between overparenting and employee well-being indicates that the experience of stress plays a significant role in determining the well-being of working women in established adulthood. Therefore, parental support programs that reduce the level of stress and provide participants with social support in coping with stress might be effective in promoting their well-being. The study emphasizes the need for implementing supportive programs to promote parents’ well-being in this unique developmental period.

References

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022170

Aycan, Z. (2004). Key success factors for women in management in Turkey. Applied Psychology, 53(3), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00180.x

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, M. (2005). Relative contributions of childcare, spousal support, and organizational support in reducing work–family conflict for men and women: The case of Turkey. Sex Roles, 53(7–8), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7134-8

Barnett, R. C., & Gareis, K. C. (2006). Role theory perspectives on work and family. The work and family handbook: Multi-disciplinary perspectives and approaches (pp. 209–221). Routledge.

Bayhan-Karapinar, P., Metin-Camgoz, S., & TayfurEkmekci, O. (2020). Employee well-being, workaholism, work–family conflict and instrumental spousal support: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 2451–2471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00191-x

Becker, P. E., & Moen, P. (1999). Scaling back: Dual-earner couples’ work-family strategies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(4), 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.2307/354019

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos120

Blackstone, A. (2003). Gender roles and society. In J. R. Miller, R. M. Lerner, & L. B. Schiamberg (Eds.), Human ecology: An encyclopedia of children, families, communities, and environments (pp. 335–338). ABC-CLIO.

Borges, D., Portugal, A., Magalhaes, E., Sotero, L., Lamela, D., & Prioste, A. (2019). Helicopter parenting instrument: Initial psychometric studies with emerging adults. Revista Iberoamericana De Diagnostico y Evaluacion-e Avaliacao Psicologica, 4(53), 33–48.

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699

Burke, T. J., Segrin, C., & Farris, K. L. (2018). Young adult and parent perceptions of facilitation: Associations with overparenting, family functioning, and student adjustment. Journal of Family Communication, 18(3), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2018.1467913

Byron, K. (2007). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

Caner, A., Guven, C., Okten, C., & Sakalli, S. O. (2016). Gender roles and the education gender gap in Turkey. Social Indicators Research, 129(3), 1231–1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1163-7

ÇelikÖrücü, M., & Demir, A. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the college adjustment self-efficacy scale for Turkish University students. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 153–156.

Chen-Bouck, L., & Patterson, M. M. (2017). Perceptions of parental control in China: Effects of cultural values, cultural normativeness, and perceived parental acceptance. Journal of Family Issues, 38(9), 1288–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15590687

Cline, F., & Fay, J. (2020). Parenting with love and logic: Teaching children responsibility. Pinon.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Cui, M., Darling, C. A., Coccia, C., Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2019). Indulgent parenting, helicopter parenting, and well-being of parents and emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 860–871.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Sonnentag, S., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work-related flow and energy at work and at home: A study on the role of daily recovery. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.760

Derya, S. (2008). Crossover of work–family conflict: Antecedent and consequences of the crossover process in dualearner couples. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Desmarais, K., Barker, E., & Gouin, J. P. (2018). Service access to reduce parenting stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 5(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-018-0140-7

Dettmers, J., Vahle-Hinz, T., Bamberg, E., Friedrich, N., & Keller, M. (2016). Extended work availability and its relation with start-of-day mood and cortisol. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 105–118.

Dwairy, M., & Achoui, M. (2010). Parental control: A second cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9334-2

Eby, L. T., Casper, W. J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C., & Brinley, A. (2005). Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(1), 124–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003

Efeoglu I. (2006). The effects of work-family conflict on job stress, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A study in the pharmaceutical industry. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey.

Ertuna, E. (2016). The Turkish translation, and reliability, validity study of helicopter parenting instrument (Doctoral dissertation, Master’s Thesis). Near East University

Esmer, Y. (1991). Values in Turkish society. TUSIAD.

Evenson, R. J., & Simon, R. W. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(4), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600403

Fikret-Pasa, S., Kabasakal, H., & Bodur, M. (2001). Society, organizations, and leadership in Turkey. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50, 559–589.

Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y. P., Wesselmann, E. D., Zarit, S., Furstenberg, F., & Birditt, K. S. (2012). Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x

Ford, M., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross domain relations’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 57–80.

Fuller, S., & Hirsh, C. E. (2019). “Family-friendly” jobs and motherhood pay penalties: The impact of flexible work arrangements across the educational spectrum. Work and Occupations, 46(1), 3–44.

Gagnon, R. J., Garst, B. A., Kouros, C. D., Schiffrin, H. H., & Cui, M. (2020). When overparenting is normal parenting: Examining child disability and overparenting in early adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01623-

Givertz, M., & Segrin, C. (2014). The association between overinvolved parenting and young adults’ self-efficacy, psychological entitlement, and family communication. Communication Research, 41(8), 1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212456392

Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25, 483–496.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Guendouzi, J. (2005). ‘“I feel quite organized this morning”’: How mothering is achieved through talk. Sexualities, Evolution, & Gender, 7, 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616660500111107

Hagqvist, E., Gådin, K. G., & Nordenmark, M. (2017). Work–family conflict and well-being across Europe: The role of gender context. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1301-x

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2017). Family, self, and human development across cultures: Theory and applications. Routledge.

Kandiyoti, D. (1995). Patterns of patriarchy: Notes for an analysis of male dominance in Turkish society. In S. Tekeli (Ed.), Women in modern Turkish society. Zed Books Ltd.

Kapoor, V., Yadav, J., Bajpai, L., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Perceived stress and psychological well-being of working mothers during COVID-19: A mediated moderated roles of teleworking and resilience. Employee Relations: THe International Journal, 43(6), 1290–1309. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-05-2020-0244

Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411400056

Kömürcü-Akik, B., & Alsancak-Akbulut, C. (2021). Assessing the psychometric properties of mother and father forms of the helicopter parenting behaviors questionnaire in a Turkish sample. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01652-4

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

LeMoyne, T., & Buchanan, T. (2011). Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 31(4), 399–418.

Leung, J. T. (2020). Too much of a good thing: Perceived overparenting and well-being of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1791–1809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09720-0

Levitzki, N. (2009). Parenting of adult children in an Israeli sample: Parents are always parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015218

Liss, M., & Schiffrin, H. H. (2014). Balancing the big stuff: Finding happiness in work, family, and life. Rowman & Littlefield.

Locke, J. Y., Campbell, M. A., & Kavanagh, D. (2012). Can a parent do too much for their child? An examination by parenting professionals of the concept of overparenting. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 22(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.29

Lu, L., Gilmour, R., Kao, S. F., & Huang, M. T. (2006). A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: The Taiwanese vs British. Career Development International, 11(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610642354

Maume, D. J. (2006). Gender differences in restricting work efforts because of family responsibilities. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 859–869.

McGinley, M., & Davis, A. N. (2021). Helicopter parenting and drinking outcomes among college students: The moderating role of family income. Journal of Adult Development, 28(3), 221–236.

Mehta, C. M., Arnett, J. J., Palmer, C. G., & Nelson, L. J. (2020). Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. American Psychologist, 75(4), 431. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000600

Metin-Orta, I., & Miski-Aydın, E. (2020). The impact of helicopter parenting on emerging adult child’s psychological well-being and its reflections on work life. In C. A. Gregory (Ed.), Family conflict: Perspectives, management and outcomes (pp. 115–139). Nova Science Publishers.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035444

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2003). Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00356.x

Odenweller, K. G., Booth-Butterfield, M., & Weber, K. (2014). Investigating helicopter parenting, family environments, and relational outcomes for millennials. Communication Studies, 65(4), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.811434

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black hawk down? Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007

Page, K. M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2009). The “what”, “why” and “how” of employee well-being: A new model. Social Indicators Research, 90(3), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9270-3

Pistella, J., Isolani, S., Morelli, M., Izzo, F., & Baiocco, R. (2021). Helicopter parenting and alcohol use in adolescence: A quadratic relation. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725211009036

Pistella, J., Izzo, F., Isolani, S., Ioverno, S., & Baiocco, R. (2020). Helicopter mothers and helicopter fathers: Italian adaptation and validation of the helicopter parenting instrument. Psychology Hub, 37, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.13133/2724-2946/

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Reed, K., Duncan, J. M., Lucier-Greer, M., Fixelle, C., & Ferraro, A. J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 3136–3149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0466-x

Rehm, M., Darling, C. A., Coccia, C., & Cui, M. (2017). Parents’ perspectives on indulgence: Remembered experiences and meanings when they were adolescents and as current parents of adolescents. Journal of Family Studies, 23(3), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1106335

Rizzo, K. M., Schiffrin, H. H., & Liss, M. (2013). Insight into the parenthood paradox: Mental health outcomes of intensive mothering. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 614–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9615-z

Sakallı, N. (2002). The relationship between sexism and attitudes toward homosexuality in a sample of Turkish college students. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v42n03_04

SakallıUğurlu, N., Türkoğlu, B., Kuzlak, A., & Gupta, A. (2021). Stereotypes of single and married women and men in Turkish culture. Current Psychology, 40(1), 213–225.

Sakallı-Uğurlu, N., TürkoğluDemirel, B., & Kuzlak, A. (2018). How are women and men perceived? Structure of gender stereotypes in contemporary Turkey. Nesne Psikolojisi Dergisi (NPD), 6(13), 309–336. https://doi.org/10.7816/nesne-06-13-04

Schiffrin, H. H., Erchull, M. J., Sendrick, E., Yost, J. C., Power, V., & Saldanha, E. R. (2019). The effects of maternal and paternal helicopter parenting on the self-determination and well-being of emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(12), 3346–3359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01513-6

Schiffrin, H. H., Godfrey, H., Liss, M., & Erchull, M. J. (2015). Intensive parenting: Does it have the desired impact on child outcomes? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2322–2331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0035-0

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3

Schwepker, C. H., Valentine, S. R., Giacalone, R. A., & Promislo, M. (2021). Good barrels yield healthy apples: Organizational ethics as a mechanism for mitigating work-related stress and promoting employee well-being. Journal of Business Ethics, 174, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04562-w

Segrin, C., Givertz, M., Swaitkowski, P., & Montgomery, N. (2015). Overparenting is associated with child problems and a critical family environment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9858-3

Segrin, C., Jiao, J., & Wang, J. (2022). Indirect effects of overparenting and family communication patterns on mental health of emerging adults in China and the United States. Journal of Adult Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09397-5

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., Bauer, A., & Taylor Murphy, M. (2012). The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations, 61(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00689.x

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., & Montgomery, N. (2013). Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(6), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.6.569

Skok, A., Harvey, D., & Reddihough, D. (2006). Perceived stress, perceived social support, and well-being among mothers of school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 31(1), 53–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250600561929

Somers, P., & Settle, J. (2010). The helicopter parent: Research toward a typology. College and University, 86(1), 18–27.

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5, pp. 481–498). Pearson.

Tayfur Ekmekci, O., Metin-Camgoz, S., & Bayhan-Karapinar, P. (2021). Path to well-being: Moderated mediation model of perfectionism, family–work conflict, and gender. Journal of Family Issues, 42(8), 1852–1879. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20957041

Touliatos, J., Perlmutter, B. F., Strauss, M. A., & Holden, G. W. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of family measurement techniques: Abstracts (Vol. 1). Sage.

Turkish Statistical Institute (2020). Retrieved February 7, 2022, from http://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=726&locale=tr

Van Jaarsveld, D. D., Walker, D. D., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). The role of job demands and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between customer and employee incivility. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1486–1504.

Voydanoff, P. (2005). Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.491

Winner, N. A., & Nicholson, B. C. (2018). Overparenting and narcissism in young adults: The mediating role of psychological control. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3650–3657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1176-3

Zheng, C., Kashi, K., Fan, D., Molineux, J., & Ee, M. S. (2016). Impact of individual coping strategies and organisational work–life balance programmes on Australian employee well-being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(5), 501–526.

Zheng, X., Zhu, W., Zhao, H., & Zhang, C. (2015). Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 36, 621–644.

Zhou, S., Da, S., Guo, H., & Zhang, X. (2018). Work–family conflict and mental health among female employees: A sequential mediation model via negative affect and perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 544–556.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The current study was approved by the Ethical Commission Board of Atilim University, Ankara/Turkey.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Helicopter parenting inventory (HPI) Odenweller et al. (2014) and adapted to Turkish by Ertuna (2016). (All items were reworded with “I” phrase to reflect how the mother responds to her child) |

1. My parent tries to make all of my major decisions |

2. My parent discourages me from making decisions that he or she disagrees with |

3. If my parent doesn’t do particular things for me, they will not get done |

4. My parent overreacts when I encounter a negative experience |

5. My parent doesn’t intervene in my life unless he or she notices me experiencing physical or emotional trauma |

6. Sometimes my parent spends more time and energy into my projects than I do |

7. My parent considers oneself a bad parent when he or she does not step in and ‘‘save’’ me from difficulty |

8. My parent feels like a bad parent when I make poor choices |

9. My parent voices their opinion about my personal relationships |

10. My parent considers himself or herself a good parent when he or she solves problems for me |

11. My parent insists that I should keep him or her informed of my daily activities |

12. When I have to go somewhere, my parent accompanies me |

13. When I am going through a difficult situation, my parent always tries to fix it |

14. My parent encourages me to take risks and step outside of my comfort zone |

15. My parent thinks it is his or her job to shield me from adversity |

Family–work conflict scale—Netemeyer et al. (1996) and adapted to Turkish by Efeoglu (2006) |

1. The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities |

2. I have to put off doing things at work because of demands on my time at home |

3. Things I want to do at work don't get done because of the demands of my family or spouse/partner |

4. My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime |

5. Family-related strain interferes with my ability to perform job-related duties |

Perceived stress scale (PSS)—Cohen et al. (1983) and adapted to Turkish by Çelik Örücü and Demir (2011) |

1. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? |

2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? |

3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and “stressed”? |

4. In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? |

5. In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way |

6. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? |

7. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life? |

8. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things? |

9. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control? |

10. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? |

Well-being—Zheng et al. (2015) and adapted to Turkish by Bayhan-Karapinar et al. (2020) |

Life well-being (LWB) |

1. I feel satisfied with my life |

2. I am close to my dream in most aspects of my life |

3. Most of the time, I do feel real happiness |

4. I am in a good life situation |

5. My life is very fun |

6 I would hardly change my current way of life in the afterlife |

Workplace well-being (WWB) |

7. I am satisfied with my work responsibilities |

8. In general, I feel fairly satisfied with my present job |

9. I find real enjoyment in my work |

10. I can always find ways to enrich my work |

11. Work is a meaningful experience for me |

12. I feel basically satisfied with my work achievements in my current job |

Psychological well-being (PWB) |

13. I feel I have grown as a person |

14. I handle daily affairs well |

15. I generally feel good about myself, and I’m confident |

16. People think I am willing to give and to share my time with |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miski Aydin, E., Metin-Orta, I., Metin-Camgoz, S. et al. Does Overparenting Hurt Working Turkish Mother’s Well-being? The Influence of Family–Work Conflict and Perceived Stress in Established Adulthood. J Adult Dev 30, 131–144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09408-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09408-5