Abstract

Based on attachment, socialization, and social learning theories, it was hypothesized that fathers’ parenting style and fathers’ specific behaviors would be related to emerging adults’ romantic relationship quality. These hypotheses were partially supported. Hierarchical regression analyses examined one hundred twenty-eight 18- and 19-year-olds in romantic relationships. For males, more paternal warmth and less psychological control were related to more support in a romantic relationship. For both males and females, more psychological control was related to more relationship conflict. Additionally, for males, perceptions of better paternal attentiveness, praise and affection, time and talking, mother support, and school encouragement were related to more relationship support, as was more global father involvement. Perceptions of better attentiveness and school encouragement were related to more depth in romantic relationships for males. The original 9-factor structure of Hawkins et al.’s (J Men’s Stud 10:183–196, 2002) Inventory of Father Involvement was not confirmed for offspring reports. However, an 8-factor structure with one second-order factor was supported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple investigations have demonstrated that positive parent–child relationships are related to offspring’s positive romantic relationships (Conger et al. 2000; Donnellan et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 1998; Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2001). Conversely parental conflict and hostility and parental emotion disregulation are associated with conflict and hostility in offspring romantic relationships (Fite et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2009; Stocker and Richmond 2007). However, few investigations have specifically examined the relation between fathering behavior and offspring romantic relationship quality.

Theoretical Background

Although there is a dearth of research on the association between fathers’ behavior and their children’s romantic relationships, three complementary theories of family processes in general have been suggested to influence romantic relationship quality (Feldman et al. 1998; Whitton et al. 2008). Attachment theory suggests that early parenting behaviors shape children’s internal working models of relationships (Ainsworth and Bowlby 1991). That is, children use early parent–child interactions to create an understanding of whether they are worthy of another’s love and whether others are trustworthy. These internal working models are suggested to be relatively stable throughout life and affect relationships with significant people throughout the lifespan. Socialization theory suggests that parents’ behaviors shape children’s psychological adjustment and interpersonal skills (Feldman et al. 1998). This theory suggests that parenting affects whether or not children will grow up to have the skills and adjustment (e.g., interpersonal skills, self-esteem) necessary to succeed in many social interactions, including romantic relationships. Specific parenting practices that are suggested to promote these skills and adjustment are warmth and behavioral control (Baumrind 1991; Maccoby and Martin 1983; as discussed in Feldman et al.). Social learning theory suggests that children learn by observing their parents’ relationship (Feldman, et al.). That is, children observe their parents’ relationships and create expectations for how romantic relationships should be. All three of these theories, along with the previous research discussed below, provided the basis of the hypotheses examined in the current investigation.

Prior Research

Only one investigation was located that investigated the association between positive father involvement and romantic relationship quality. In a longitudinal investigation that began when children were 7 years old and ended when those same individuals were 33 years old, adolescents with a good relationship with their fathers at age 16, had better marital satisfaction at age 33 (Flouri and Buchanan 2002). Additionally, the association between having a good relationship with their fathers at 16 and later marital adjustment did not depend on the quality of the mother–child relationship at age 16. One limitation to this study is that the parent–child relationship measure was only one question. It asked to what extent “they get on well with their father/mother.” However, the longitudinal nature of this study and the fact that they examined the possible interaction of the mother–child relationship strengthen the interpretation of the findings.

The evidence for an association between relationships with parents (i.e., a combination of mothers and fathers or just mothers) and relationships with romantic partners emerges during late adolescence and early adulthood. Multiple studies examine constructs related to parenting style. Nurturant-involved parenting (i.e., high affect and monitoring, low hostility and harsh parenting) in adolescence, measured through observation and averaged across 4 years and across both parents, predicts affective behaviors toward a romantic partner 5 years later, in early adulthood (Conger et al. 2000). Similarly, nurturant-involved parenting when the adolescent was a senior in high school, also measured through observation and averaged across both parents, predicts romantic relationship quality and negative interactions in romantic relationships 5 years later (Donnellan et al. 2005).

Another study examines a related but separate aspect of the parent–child relationship. In a longitudinal study starting at age 13 and continuing into the transition to young adulthood (Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2001), reliable alliance (i.e., a bond that is lasting and dependable; Furman and Buhrmester 1985) with parents at both age 15 and age 17, predicted connectedness and attraction in romantic relationships at age 20.

Some studies examine family relationships as opposed to parenting, per se. Adolescent reports of family cohesion and family adaptability, assessed at age 13–18, predict happiness in love at age 19–25 (Feldman et al. 1998).

Conversely, adolescent exposure to negative parental behaviors affects offspring romantic relationship quality as well. For example, negative family affect influences later romantic relationships (Kim et al. 2001). The level of negative emotions (i.e., hostility, angry coercion, and antisocial behavior) adolescents express toward their parents (i.e., combined mother and father scores on an observational measure) predicts the level of negative emotions they express to a romantic partner several years later. Additionally, when, over time, adolescents have an increasing amount of negative affect towards their parents, the same adolescents, as adults, are likely to have an increasing amount of negative affect towards an adult romantic partner over time. Investigations have also examined the intergenerational transmission of aggressive relationship conflict and of relationship hostility. Children’s exposure to interparental conflict, a latent variable combining mothers’ and fathers’ scores, in early childhood is related to their own relationship conflict in emerging adulthood (Fite et al. 2008). In the Fite et al. investigation, this relationship is partially mediated by social information processing, specifically response generation and response evaluation. Similarly, parental emotion disregulation, averaging mother and father scores, when sons are in early adolescence is associated with sons’ emotion disregulation in late adolescence, which is then related to their relationship conflict in early adulthood (Kim et al. 2009). Finally, exposure to parents’ marital hostility (e.g., criticizing, blaming, impatience, and coldness; averaged across mothers and fathers) in adolescence is related to hostility in adolescents’ own romantic relationships 3 years later (Stocker and Richmond 2007).

As discussed above, there is a dearth of research on the relation between fathering and offspring romantic relationship quality. By extension, there is little research on potential gender differences in that association. There is, however, reason to suspect that there could be gender differences. Although they did not examine fathers separately from mothers, De Goede et al. (2012) found that middle and late adolescents’ commitment to parents (i.e., attachment to the relationship and intention to maintain the relationship; a combination of mother and father scores) was longitudinally related to romantic relationship commitment. In preliminary analyses, they found that commitment to mothers and fathers was the same for boys. However, for girls, commitment to mothers was higher than commitment to fathers. This suggests the possibility that, due to the difference in commitment level, boys’ romantic relationships may be more influenced by their fathers than girls’ romantic relationships. Thus, it is important to investigate gender differences when examining the relation between emerging adults’ relationship with their father and their romantic relationship quality.

Present Study

This investigation sought to increase knowledge of the association between father involvement and offspring’s romantic relationship quality. Specifically, it examined how positive father involvement in their offspring’s lives is related to romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. That is, it examined the association between both fathers’ parenting style (i.e., constellations of behavior) and specific fathering behaviors and offspring relationship quality. The relation between parenting behavior and romantic relationship quality seems most evident during late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Thus, if there are associations related specifically to fathering behavior, they are most likely to be found in the age group in the current study.

Two distinct measures of father involvement were used. In the fathering literature, there are multiple conceptual frameworks of father involvement; there are no widely used, psychometrically tested measures of father involvement; and one set of behaviors may not reflect how all fathers are involved with their children (Cabrera et al. 2000; Marsiglio et al. 2000; Palkovitz 2002). Using both a standard measure of parenting style and a specific measure of fathering behavior provided richer data. It allowed for the investigation of constellations of behavior (i.e., parenting style), which is a common construct in the parenting literature, and specific measures of fathering behavior, which is common in the fathering literature.

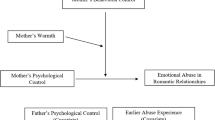

Two hypotheses were put forth is this investigation. First, fathers’ parenting style would be related to emerging adults’ romantic relationship quality. It was predicted that more paternal warmth, more paternal behavioral control, and less paternal psychological control would be associated with more romantic relationship support and depth, and less conflict during emerging adulthood. Second, it was hypothesized that subjective accounts of specific fathering behaviors would be associated with emerging adult romantic relationship quality. Specifically, it was predicted that when emerging adults perceived that their father did a good job with discipline and teaching responsibility, mother support, praise and affection, time and talking together, and attentiveness they would also experience more romantic relationship support and depth, and less conflict. In addition, gender was added as an interaction term in order to explore potential gender differences in the relation between fathers’ behavior and emerging adult romantic relationship quality.

Methods

Sample

Participants in this study were taken from a larger study of family relationships (N = 550), all of whom were recruited from introductory psychology classes at a large, Midwestern university. Participants were excluded if they were over 19 years old, were not freshmen, were not in a romantic relationship, or if their fathers were deceased, resulting in 128 participants. Thirteen percent were African American; 1 % were Asian American, 9 % were Latino, 73 % were European American, 3 % were multi racial, 1 % were other ethnicities. Seventy-six percent were female. Forty-eight percent had been in the relationship for 1 year or more, 13 % for 6 months to 1 year, 23 % for 3–6 months, and 16 % for less than 3 months (M = 1.25 years, SD = 1.18). Data were collected on both fathers and stepfathers. However, in order to avoid problems with non-independence of data, only data on biological or adoptive fathers were included in these analyses. The Institutional Review Board at the author’s graduate institution approved the study protocol.

Measures

Demographics and Background Information

Basic demographic data were gathered. This included age, gender, ethnicity, and romantic relationship status.

Parenting Style

The Children’s Report of Parent Behavior Inventory was used to assess perceptions of the parenting style of the father and the mother. The CRPBI was designed by Schaefer (1965) and revised by Schludermann and Schludermann (1970). It has been shown to be a sensitive measure for both boys and girls assessing both mothers and fathers (Margolies and Weintraub 1977; Schaefer 1965), across ethnicities (Schludermann and Schludermann 1983), for children and adolescents (Margolies and Weintraub 1977).

Participants completed the 53-item scale for mothers and fathers separately. The measure is comprised of three subscales that represent levels of warmth (e.g., seems proud of the things I do), levels of behavioral control (e.g., lets me off easy when I do something wrong [reverse coded]), and levels of psychological control (e.g., thinks I’m not grateful when I don’t do what he wants). All items are rated on a 3-point scale (3 = just like your mother/father; 2 = a little like your mother/father; 1 = not at all like your mother/father). The maternal authoritative parenting style variable was created by summing the warmth and behavioral control subscales. Higher scores represent more authoritative parenting and lower scores represent less authoritative parenting. Internal consistency reliability estimates were strong for maternal authoritative parenting (α = .90). The separate subscales were examined for fathers. Higher scores represent more warmth (α = .97), more behavioral control (α = .89), and more psychological control (α = .89).

Father Involvement

The emerging adult’s perception of the quality of father involvement, across nine domains of involvement, was measured using a modified version of the Inventory of Father Involvement (IFI; Hawkins et al. 2002). This assessment taps into behavioral, cognitive, and affective, aspects of fathering. It includes both direct and indirect involvement. This scale has nine subscales, or can be combined into a global fathering scale. Hawkins et al. found the subscales to have good internal consistency. This measure also has good face validity and good construct validity for eight of the nine subscales (Hawkins et al.). The construct validity for School Encouragement was weaker than Hawkins et al. had expected.

The IFI was originally designed to be from the father’s perspective. In the current investigation, the measure was modified to be from the offspring’s perspective. It asked how good of a job the participant thought their father did on the various tasks relating to fathering. In addition, one original item that was not developmentally appropriate was deleted (i.e., reading to your younger children). All items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from very poor to excellent. The mean for each subscale was computed. Higher scores represent perceptions of better performance on each subscale construct. Although not ideal, the participants were asked to reflect back to the previous year when reporting on their father’s behavior. The specific items in each subscale are discussed in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) below. The reliabilities listed for all of the measures are from the larger study sample (N = 550). The Discipline and Teaching Responsibility subscale focuses on the behavioral control aspect of parenting. This subscale has three items (α = .90). The School Encouragement subscale focuses on how the father is involved in school-related matters. This subscale has three items (α = .93). The Mother Support subscale focuses on how much support the father gives the mother. This subscale has three items (α = .94). The Providing subscale focuses on financial or in-kind support that the father gives his offspring. This subscale has two items (α = .92). The Time and Talking Together subscale focuses on the friendliness of the relationship between father and offspring and the amount of time the father spends with his offspring. This subscale has three items (α = .93). The Praise and Affection subscale focuses on the praise that the father gives his offspring. This subscale has three items (α = .93). The Developing Talents and Future Concerns subscale focuses on encouraging their offspring’s strengths and planning for the future. This subscale has three items (α = .88). The Reading and Homework Support subscale focuses on how the father is involved in encouraging reading and helping with homework. This subscale has two items (α = .78). The Attentiveness subscale focuses on monitoring and involvement in everyday activities. This subscale has three items (α = .88). Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale is .98.

Romantic Relationship Quality

Romantic relationship quality was assessed by the 25-item Quality of Relationship Inventory (Pierce et al. 1991). This inventory was originally created to measure relationship quality in a variety of specific relationships. The inventory has three scales, which assess the support, depth, and conflict dimensions of relationship quality. Previous research (Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2001) has suggested that behaviors related to support in a romantic relationship are most likely to be associated with parental behaviors. However, this study examined all three subscales. The 7-item support dimension measures the extent to which the participant can rely on the other person. An example is, To what extent can you turn to this person for advice about problems? The 6-item depth dimension measures how significant the other person is in one’s life. An example is, How much would you miss this person if you couldn’t see or talk to them for a month? The 12-item conflict dimension measures anger and ambivalence in a relationship. An example is, How often do you have to work hard to avoid conflict? The original 3-factor structure was confirmed for romantic couples by Verhofstadt et al. (2006). Pierce et al. found this measure to have good discriminant and predictive validity. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to always/a lot/very. The mean was computed for each subscale. Higher scores represent more support received, more depth, and more conflict. For this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .84 for the support subscale, .85 for the depth scale, and .91 for the conflict scale.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In order to test the IFI’s (Hawkins et al. 2002) utility as a measure for which an offspring reports on their father’s involvement, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, with guidance from Kline (2005), first using three standard analyses. The model was tested as a single factor model, it was tested as a 9-factor model, and it was tested as the original 9-factor model with one hierarchical factor. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess model fit.

The model was tested with a sample of 508 participants at a large Midwestern university. This subsample of the larger data set (N = 550) only included participants with complete data on this scale. The larger dataset was used because SEM, especially with the number of indicators in this analysis, requires a large sample. The larger data set is the data from which the subsample for the analyses of romantic relationship quality was taken. The subsample was 57 % female, had a mean age of 19.47 years, and was 14 % African American, 6 % Asian American, 69 % European American, 8 % Latino, 3 % multi-racial, and 1 % other. The skew of all indicators was less than 2; the kurtosis of all indicators was less than 2.6.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) first estimated a single-factor model using a maximum likelihood estimation. The scale of each of the latent variables was specified by fixing the unstandardized coefficient of one indicator of each latent variable to one. The goodness-of-fit indices for this model did not indicate a good fit to the data (CFI = .76, TLI = .74, RMSEA = .15). Second, the model was estimated as a 9-factor model. Again, the goodness-of-fit indices for this model did not indicate a good fit to the data (CFI = .65, TLI = .62, RMSEA = .19). Third, the model was estimated with the original factor structure. This model includes 25 indicators, 9 first-order factors, and 1 second-order factor. The goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that the model did not fit the data (CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .08). The RMSEA was within the moderate fit range, but the CFI and the TLI were below the .95 cutoff for a good fit. The goodness-of-fit statistics for all models are listed in Table 1.

With the original factor structure being very close to being a good fit, the next step was to systematically remove each subscale from the model, one by one, to test for model fit. Indeed, with the removal of the Developing Talents and Future Concerns subscale, the model fit the data well. The CFI was .96 and the TLI was .95, both indicating a good fit to the data, and the RMSEA was .07, which indicates a moderate fit to the data. The factor loadings for each indicator are listed in Table 2. With the Developing Talents and Future Concerns subscale removed, the full scale had excellent internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of .97.

Thus, in the subsequent analyses, the IFI was used as an eight sub-scale measure, with a global father involvement full-scale measure that included those eight subscales. However, because modifications were made to the original factor structure, the factor structure used in these subsequent analyses should be considered preliminary, and should be confirmed in future analyses.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses examined associations between parenting style and retrospective accounts of fathers’ behavior the previous year and current romantic relationship quality. Separate analyses were conducted for each father variable (i.e., paternal warmth, paternal behavioral control, paternal psychological control, the IFI full scale, and each of the 8 IFI subscales). In this study, it was decided to control for maternal behavior, as opposed to examining interactions. By doing this, fathers’ behavior could be examined above and beyond mothers’ behavior. In order to control for maternal parenting behaviors, maternal authoritative parenting was entered into the model first. Variables were entered in four separate blocks as follows: maternal authoritative parenting, gender, father variable, interaction between father variable and gender. Bivariate correlations for all variables included in the regression analyses are available in Table 3.

Above and beyond maternal authoritative parenting, the interaction between emerging adults’ gender and paternal warmth (B = −.02, p = .005, ∆R2 = .07) and gender and paternal psychological control (B = .03, p = .032, ∆R2 = .04) were associated with relationship support (i.e., how much the participant felt he or she could rely on the other person). Simple slope analyses revealed that more paternal warmth (B = .01, p = .019) and less psychological control (B = −.02, p = .032) were associated with more support in a relationship, but only for males. A main effect was found for the relation between paternal psychological control and emerging adult’s relationship conflict. Less psychological control was related to less relationship conflict (B = .02, p = .007, ∆R2 = .06). No association was found between behavioral control and romantic relationship support, conflict, or depth. See Table 4 for all parenting style analyses.

Eight subscales and the global full-scale assessed emerging adults’ perceptions of the quality of father involvement. No main effects were found. However, seven analyses had significant interactions. The ∆R2 for the significant interactions associated with support ranged from .06 to .09. The ∆R2 for the significant interactions associated with depth ranged from .03 to .04. Simple slope analyses revealed that five subscales and the global full scale (B = .22, p = .009) were related to support in romantic relationships; however, these associations were only found for males. Perceptions of better paternal attentiveness (B = .23, p = .001), praise and affection (B = .17, p = .006), time and talking (B = .16, p = .007), mother support (B = .20, p = .007), and school encouragement (B = .23, p = .002) were related to more support. In addition, perceptions of better attentiveness (B = .18, p = .033) and school encouragement (B = .17, p = .046) were related to depth in the romantic relationship for males. None of these nine variables were related to relationship conflict. All analyses for the measure of specific father behavior can be found in Table 5.

Discussion

At least three theories suggest the mechanism through which emerging adults’ relationship quality might be affected by fathering behavior. Attachment theory, socialization theory, and social learning theory are all supported by this study as pathways through which positive romantic relationships may be formed. Instead of pitting one theory against another, this section will demonstrate how the theories are complementary and how they can work together to help explain behavior.

Warmth, psychological control, attentiveness, praise and affection, time and talking, and school encouragement were all related to romantic relationship quality. When a male emerging adult has a father who demonstrates warmth, that male may learn that he is worthy of being loved and being treated well, and thus form relationships with people who support him. Similarly, when a father is attentive, gives his son praise and affection, spends time with his son, and encourages his son to achieve in school, the son may learn that he is worthy of being supported and learn that he can trust others to be there for him. Thus, he may seek out relationships in which he receives support. When a father is attentive, provides school encouragement, and is involved overall in his son’s life, the trust and sense of worthiness that is gained from this behavior may translate into the son being able form romantic relationships that have depth and significance. In contrast, when a father exhibits psychological control, the son may learn that he is not worthy of being loved and, thus, may not demand that from a romantic relationship. The son may also learn that he cannot necessarily trust someone with whom he is supposed to have a loving relationship. That son may then not expect or engage in a relationship in which he is properly supported. Conversely, when a father engages in less psychological control, the sense of trust and worthiness of love is fostered and support may then be sought out in later romantic relationships. These results are consistent with the internal working models of attachment theory (Ainsworth and Bowlby 1991).

When a father is warm towards his son, when he praises his son and shows him affection, and when he spends time talking with his son, the son may learn the interpersonal skills necessary to be a part of a supportive relationship. He may, thus, learn to give and receive support within a romantic relationship. When a father is attentive, a son may learn the attentiveness to another person’s needs that is necessary in a romantic relationship that is characterized by depth. Conversely, when a father engages in psychological control, the offspring may learn this type of interpersonal behavior, and carry it over into romantic relationships. This may then result in conflict in the relationship. These results are consistent with socialization theory (Baumrind 1991; Maccoby and Martin 1983).

When a son sees his father being supportive of his mother, the son may learn not only to support his partner in a romantic relationship, but also to expect support from that partner in return. This is consistent with social learning theory (Feldman et al. 1998).

In addition to theory, this study supports previous findings regarding the influence of parenting on offspring romantic relationships. Specifically, that fathering behavior influences offspring’s romantic relationships (Flouri and Buchanan 2002). This study goes beyond previous findings to examine specific fathering behavior and constellations of behavior, as opposed to a single item measure of father involvement, that are associated with emerging adults’ behavior. Similarly, this study supports and extends previous findings related to parenting in general. Previously, it has been demonstrated that positive parent–child relationships are associated with healthy offspring romantic relationships (Conger et al. 2000; Donnellan et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 1998; Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2001) and that parental conflict, hostility, and emotion disregulation are associated with conflict and hostility in offspring romantic relationships (Fite et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2009; Stocker and Richmond 2007). This study extends previous research to suggest that fathering behavior, specifically, may be related to emerging adults’ relationship quality. In addition, the work of Seiffge-Krenke et al. (2001) found that parent–child relationships were most related to connectedness (i.e., a close and trusting relationship that includes exclusivity and support) in a romantic relationship. This study supports those findings, with an emphasis on fathering. Overall, support was the most consistent association found in this study.

The amount of variance explained by the interaction terms associated with support ranged from 4 to 9 %. This suggests that although not explaining a large amount of the variance, the interaction of fathering behavior and offspring gender does uniquely contribute to the constellation of factors that explain the variance in romantic relationship support. The amount of variance explained for conflict was 6 %. The amount of variance explained by the interaction terms associated with depth were smaller, and ranged from 3 to 4 %. Thus, fathering behavior may be especially important in accounting for the variance in romantic relationship support and in conflict.

This study did not find the same results for females as it did males. This is not to suggest that female romantic relationships are not related to their father’s behavior. There are several possible reasons why the same results were not found for females. It could be that this construct of romantic relationship does not tap into what specifically females are acquiring from positive relationships with their fathers. For example, fathering behavior might be more related to female sexual development and behavior (James et al. 2012) than romantic relationships quality, per se. Alternatively, De Goede et al. (2012) suggest that adolescent girls’ commitment to mothers is higher than it is to fathers, whereas for boys it is the same. Consistent with social learning theory (Bandura 1978; Feldman et al. 1998), when it comes to romantic relationships, if offspring are more committed to one parent than another, they may be more influenced by that parent. Similarly, girls may be more influenced by their same-sex parent than their opposite sex parent due to the nature of the behavior that is being modeled. Finally, the reason that the same results were not found for females as were found for males could be an artifact of this particular sample.

There are several limitations and future directions for this study. First, participants’ account of their father’s behavior was a retrospective account of their behavior the previous year. When reporting retrospectively, participants’ memories may have faded or their memories may be influenced by their current state of mind. Future longitudinal studies should tease out this potential confound. Second, this sample consisted entirely of college students. The timing of relationship patterns may be different for emerging adults who do not attend college. That is, the age at which associations between parenting and emerging adults’ romantic relationships are found might differ for individuals who do not attend college. In the future, studies should recruit non-college attending emerging adults. Third, this study was cross-sectional and partially retrospective. Therefore, no assumption of causality can be made. Although the wording of the questions suggests temporal precedence, longitudinal studies are required to show true temporal precedence. Finally, the CFA for the modified measure did not confirm the original factor structure of the IFI for offspring reports. Thus, the factor analysis should be treated as an exploratory factor analysis until the new factor structure is confirmed.

Conclusion

This study suggests that fathers may play an important role in the healthy development of sons’ romantic relationships. The father-son relationship itself and the son’s observations of the father-mother relationship were associated with the son’s romantic relationship quality. In addition, psychological control was related to relationship conflict for both sons and daughters. Although data in this study cannot speak to causality, the results do suggest that paternal warmth, including attentiveness, praise and affection, school encouragement, and time and talking; modeling a healthy relationship with the child’s mother; and engaging in less psychological control may promote healthy young adult romantic relationships. This study contributes to the growing body of literature on the importance of the father in child, adolescent, and emerging adult development. It highlights the need to carefully consider fathers when examining the development of adolescents and emerging adults. It also demonstrates the importance of encouraging the inclusion of fathers when promoting healthy development.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46, 333–341. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.46.4.333.

Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33, 344–358.

Baumrind, D. (1991). Parenting styles and adolescent development. In R. M. Lerner, A. C. Petersen, & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (Vol. 2, pp. 746–758). New York: Garland Publishing.

Cabrera, N. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bradley, R. H., Hofferth, S., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71, 127–136. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00126.

Conger, R. D., Cui, M., Bryant, C. M., & Elder, G. H, Jr. (2000). Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 224–237. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224.

De Goede, I. H. A., Branje, S., van Duin, J., VanderValk, I. E., & Meeus, W. (2012). Romantic relationship commitment and its linkage with commitment to parents and friends during adolescence. Social Development, 21, 425–442. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00633.x.

Donnellan, M. B., Larsen-Rife, D., & Conger, R. D. (2005). Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 562–576. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562.

Feldman, S. S., Gowen, L. K., & Fisher, L. (1998). Family relationships and gender as predictors of romantic intimacy in young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8, 263–286. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0802_5.

Fite, J. E., Bates, J. E., Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Dodge, K. A., Nay, S. Y., & Pettit, G. S. (2008). Social information processing mediates the intergenerational transmission of aggressiveness in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 367–376. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.367.

Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2002). What predicts good relationships with parents in adolescence and partners in adult life: Findings from the 1958 British birth cohort. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 186–198. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.2.186.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024.

Hawkins, A. J., Bradford, K. P., Palkovitz, R., Christiansen, S. L., Day, R. D., & Call, V. R. A. (2002). The inventory of father involvement: A pilot study of a new measure of father involvement. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 10, 183–196. doi:10.3149/jms.1002.183.

James, J., Ellis, B. J., Schlomer, G. L., & Garber, J. (2012). Sex-specific pathways to early puberty, sexual debut, and sexual risk taking: Tests of an integrated evolutionary–developmental model. Developmental Psychology, 48, 687–702. doi:10.1037/a0026427.

Kim, E. J., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Elder, G. H, Jr. (2001). Parent-adolescent reciprocity in negative affect and its relations to early adult social development. Developmental Psychology, 37, 775–790. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.6.775.

Kim, H. Y., Pears, K. C., Capaldi, D. M., & Owen, L. D. (2009). Emotion disregulation in the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 585–595. doi:10.1037/a0015935.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

Margolies, P. J., & Weintraub, S. (1977). The revised 56-item CRPBI as a research instrument: Reliability and factor structure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 472–476.

Marsiglio, W., Day, R. D., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Exploring fatherhood diversity: Implications for conceptualizing father involvement. Marriage & Family Review, 29, 269–293. doi:10.1300/J002v29n04_03.

Palkovitz, R. (2002). Involved fathering and child development: Advancing our understanding of good fathering. In C. S. Tamis-LeMonda & N. Cabrera (Eds.), Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 119–140). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (1991). General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 1028–1039. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.6.1028.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424. doi:10.2307/1126465.

Schludermann, E., & Schludermann, S. (1970). Replicability of factors in children’s report of parent behavior (CRPBI). The Journal of Psychology, 76, 239–249. doi:10.1080/00223980.1970.9916845.

Schludermann, S., & Schludermann, E. (1983). Sociocultural change and adolescents’ perceptions of parent behavior. Developmental Psychology, 19, 674–685. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.19.5.674.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., Shulman, S., & Klessinger, N. (2001). Adolescent precursors of romantic relationships in young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18, 327–346. doi:10.1177/0265407501183002.

Stocker, C. M., & Richmond, M. K. (2007). Longitudinal associations between hostility in adolescents’ family relationships and friendships and hostility in their romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 490–497. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.490.

Verhofstadt, L. L., Buysse, A., Rosseel, Y., & Penne, O. J. (2006). Confirming the three-factor structure of the Quality of Relationships Inventory within couples. Psychological Assessment, 18, 15–21. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.15.

Whitton, S. W., Waldinger, R. J., Schulz, M. S., Allen, J. P., Crowell, J. A., & Hauser, S. T. (2008). Prospective associations from family-of-origin interactions to adult marital interactions and relationship adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 274–286. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karre, J.K. Fathering Behavior and Emerging Adult Romantic Relationship Quality: Individual and Constellations of Behavior. J Adult Dev 22, 148–158 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-015-9208-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-015-9208-3