Abstract

The Identity Issues Inventory (I3) uses an Eriksonian framework to assess identity stage resolution among those experiencing a prolonged transition to adulthood in terms of the developmental tasks of self-identity formation (integration and differentiation) and societal-identity formation (work roles and worldview). For this first analysis of this new measure, data were collected from two samples: (1) 196 people between the ages of 18 and 48 and (2) 1,489 participants between the ages of 18 and 41. Overall, the I3 yields good factorial validity and reliability, and scores increase with age toward the “ceiling” of each task subscale, which represent anchors of a stable adult identity. Structural equation modeling assessed the relationships between these prominent identity issues and psychological health, revealing a positive relationship between the two constructs, providing evidence for predictive validity. An analysis of the second sample of 1,498 people confirmed these findings. The I3 promises to be a useful tool in future investigations of identity stage resolutions for those aged 18 and above experiencing a prolonged transition to adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a broad consensus among social scientists that the transition to adulthood has become increasingly prolonged in developed societies over the last half century, extending it into the early- to late-20s for most young people, and beyond for others. Although a variety of causes for this change to the life course have been postulated and debated (e.g., Arnett et al. 2011; Côté and Bynner 2008), there has been little empirical attention on the consequences of this prolonged transition in terms of establishing a functional adult identity (Côté 2006a). In this paper, we propose a theoretical model that seeks to characterize the essential issues associated with prolonged identity formation, and based on this model, we develop and test a new operationalization of identity formation that is suitable for those in their 20s, 30s, and beyond in societies characterized by this prolonged transition to adulthood. This operationalization is based on a neo-Eriksonian model, updated to account for identity formation beyond adolescence in terms of the key identity issues now found in early adulthood in many Western countries.

Two issues are paramount in determining whether a new model and operationalization contribute to the field of identity studies: the content of the measures and their age appropriateness.

With respect to content, although a number of operationalizations are available in the literature, many were devised in the 1960s and 1970s (e.g., Constantinople 1969; Rasmussen 1964; Simmons 1973), so the content of these measures focused on some issues that may not be as relevant for current cohorts. For example, questions about religion and politics formed the original basis of the identity status assessment of respondents’ ideological values and beliefs (Marcia 1964, 1980). However, in contrast to adolescents of the mid-twentieth century, it is possible that religious and political issues have taken on an entirely different relevance for more recent cohorts (cf. Schwartz et al. 2013). In many countries, current cohorts are at historical low levels of involvement in organized religion and the mainstream political process (e.g., Gidengil et al. 2003); although many of those young people take an interest in these traditional institutions, involvements tend to be more individualized, based on a cafeteria-style, picking-and-choosing of various elements that they find personally appealing (Côté 2000).

For example, in Canada, only 12 % of young people attended services regularly in the 1990s, down dramatically from mid-century (e.g., Clark 1998). According to Statistics Canada, the percentage of Canadians reporting “no religion” on their census forms increased from less than 1 % prior to 1971 to 16 % in 2001, and 40 % of those reporting no religion were 24 or younger (Statistics Canada 2003). As of 2004, over half of young Canadians (aged 15–29) reported either no religious affiliation or not attending any religious services (Clark and Schellenberg 2006). Given the growing ambivalence toward and the consequent low level of community pressure to explore these issues in secularized countries like Canada, we should no longer expect these belief systems to be a source of normative explorations that are pivotal in terms of formulating a worldview upon which to base a sense of adult identity. Accordingly, we may now need to consider that there are new sources of identity content focused on different issues and belief systems, especially among those in their 20s and 30s, and that content-specific measures are becoming less useful. These developments suggest that it is possible that developing a coherent worldview in contemporary (individualized, late-modern) societies has become a significant impediment for many people in terms of developing an adult identity, so a measure that assesses this possibility would be useful.

In terms of age appropriateness, it is unclear how adequate these older measures are for assessing prolonged forms of identity development beyond the adolescent years. As Arnett (2000) and others (Schwartz et al. 2013) have stated, the issues faced by those in their 20s are often different than those faced in their teens, especially given the greater independence from parents of the older age-group in conjunction with their necessity of finding long-term employment and financial independence of some form. We would add that those in their 30s face additional and different issues, and so forth through the life course.

In looking at the identity literature on older age-groups, there is little available literature independent of university student samples upon which to assess how the prolonged transition to adulthood is affecting identity formation (Schwartz et al. 2013). And even among post-secondary students, the empirical literature has uncovered little identity development that is attributable to educational experiences at that age. For example, Pascarella and Terenzini (1991, 2005) report that there is little demonstrable effect of college attendance net of maturational effects (i.e., changes in these variables might take place without someone attending college).

Moreover, even in the sparse literature on identity formation among those who do not attend post-secondary institutions, the findings suggest that the existing measures fail to capture the essential issues driving whatever identity development might be taking place. For example, one landmark study using the identity status paradigm casts doubt of the appropriateness of that paradigm in studying identity formation among older age-groups. In this study, Fadjukoff and Pulkkinen (2005) followed over 200 Finnish adults from ages 27 to 36, and again to 42. They report that because of the piecemeal approach to the identity status domains taken by most adults in their sample, they had a difficult time determining an overall identity status for most adults. Less than 10 % of those studied shared all five domains in the same status at any of the three data collection points (politics, religion, occupation, relationships, and lifestyle). Overall, only one half of the sample had the same global identity status at all three points, even on three out of five criteria.

With respect to identity formation involving developing coherent religious and political commitments, Côté (2006b) found little activity beyond adolescence in a 10-year longitudinal study of Canadian university students first tested in their frosh year. Using Adams’ (Bennion and Adams 1986) paper-and-pencil operationalization of identity status, little activity was evident in religious and political identity formation during the 20s, especially after graduation, suggesting that most young people make up their minds in their teens, or avoid the issues entirely and then stick with that position.

Côté’s (2006b) longitudinal study also introduced a new measure based on a continuum approach to measuring identity formation processes—the Identity Stage Resolution Index (ISRI). In contrast to the lack of identity formation detected by the identity status measure, Côté (2006b) found that the ISRI detected evidence of progress in the early-20s in terms of forming a sense of Adult Identity, as well as in the late-20s in terms of forming a sense of Societal Identity. However, most of the progress of this sample in resolving the identity stage was made between the early- and late-20s, not between the late-teens and early-twenties, suggesting that some sort of developmental delay took place for this sample in the formation of adult and societal identities. Such a delay is understandable in the context of the research, indicating that the developmental milestones of adulthood are now delayed by some 5 years. Ample empirical evidence supports this consensus.

For example, in Canada, Clark (2007) provided census data showing that, since 1971, five key milestones have been delayed by between 3 and 5 years: leaving school, leaving their parents’ home, having full-year full-time work, entering conjugal relationships, and having children. Noting a continual decade-by-decade extension of the transition to adulthood, Clark concluded that the typical Canadian 25-year-old of 2001 had made the same number of milestone transitions as a 22-year-old of 1971, while the contemporary 30-year-old had progressed about as far as the 25-year-old of the early-1970s (women make the transitions earlier than men, with convergence at age 30).

Identity Stage Resolution Revisited: The Identity Tasks of Early Adulthood

Based on experience with the ISRI measure and the results that suggest important aspects of identity formation are delayed and/or prolonged because a number of important identity-related issues need to be resolved, the ISRI was elaborated into a multidimensional measure of identity formation, using items deemed appropriate to the life circumstances of those in their 20s, 30s, and beyond in some cases. This multidimensional measure strives to provide a more adequate construct representation (Cook and Campbell 1979) of identity formation during early adulthood than is available in existing measures designed to capture adolescent identity, mapping four interrelated tasks of adult-identity formation while building on three underlying and interrelated levels of identity. This instrument, the Identity Issues Inventory (I3) is based on Erikson’s writings about psychosocial identity formation in the areas of (1) self-identity, along with some recent elaborations of his work in terms of self-integration and self-differentiation, and (2) societal identity, as represented in the assumption of work roles and the acceptance of a functional worldview. This measure adopts the continuum approach to the measurement of identity formation, assuming that the same processes are potentially at work for everyone, but that individual differences exist in terms of how the issues underlying these processes are dealt with, including the rate of progress in resolving them. This measure also operationalizes the positive and negative aspects of identity formation, or what Erikson (1968) called ego syntonic and dystonic identity elements. (Erikson was critical of “the frequency with which not only the term identity, but also the other syntonic psycho-social qualities ascribed by me to various stages, were widely accepted as conscious developmental ‘achievements’, while certain dystonic states (such as identity confusion) were to be totally ‘overcome’ like symptoms of failure. Thus, my emphasis in each stage on a built-in and lifelong antithesis (‘identity’ v. ‘identity confusion’) was given a kind of modern Calvinist emphasis.” (1979, p. 24).)

Mapping the Constructs: Dimensions of Identity Issues and Tasks of Identity Formation

Dimensions Côté and Levine’s (2002) social-psychological approach to identity formation identifies three interrelated dimensions or levels of identity: (1) the subjective/experiential sense of the mental activities (ego identity), (2) the realm of the day-to-day interpersonal activities with others (personal identity), and (3) the social roles a person plays in a society and the relative status of these roles (social identity). This approach assumes that certain issues or challenges need to be addressed by the developing person for each identity-related task at each of these three levels. These levels are likely interrelated and mutually supportive. For example, progress at the level of the ego requires progress to be made at the personal and social levels, and progress at the social level needs to be sustained by development at the personal and ego levels. At the same time, each dimension has syntonic and dystonic aspects that need to find some sort of balance for effective functioning in terms of mastering the tasks of identity formation. Because these levels are conceptually interrelated at a moderate to high level, they are treated as different aspects of the construct represented by the identity-related task, thereby fulfilling Cook and Campbell’s (1979) requirement of construct representation. (None of the existing measures in the literature attempt this form of multidimensional representation of the identity construct.) Consequently, the three levels of identity are predicted to constitute single factors within each of the four tasks, with the total I3 comprising four task factors.

Tasks In place of culturally specific domains like political and religious experimentation and commitment, two sets of psychosocial tasks, each with subtasks, were identified in this model to represent four aspects of identity development that are less content specific than the domains identified in existing measures and which require “identity work” at each of the three dimensions of identity (ego-, personal-, and social identity).

The relevance of the first set of tasks—the formation of self-identity—is implicit in Erikson’s work, and indeed in much of the human development literature. Logically and in its essence, “identity” involves both sameness and difference. Even following dictionary definitions of identity, any entity needs to have sameness over time, but it also needs to have some sort of difference from other entities. (A table needs to maintain its structure to remain a table, and it must be sufficiently different from a chair to be recognized as a table.) Adams and Marshall (1996) elaborated these tasks in terms of “integration” and “differentiation” (noting similarities with concepts like communion and agency or relatedness and individuality). They argue that maintaining a balance of these two attributes is the key for optimal identity formation:

Balance between the processes of interpersonal differentiation and integration is critical for healthy human development (Erikson 1968; Grotevant and Cooper 1986; Papini 1994). A high degree of differentiation which results in extreme uniqueness of an individual is likely to be met with a lack of acceptance by, and communion with, others. Low interpersonal integration of an individual can lead to marginalization, or a drifting to the periphery of a life system. Some individuals will find community with other marginalized persons and build or join another life system that meets their need for communion. However, low integration into a life system(s) will diminish individuals’ sense of mattering to others and to commitments to particular social roles (Schlossberg 1989). Conversely, extreme connectedness and low interpersonal differentiation within a life system can curtail individuals’ sense of uniqueness and agency. This can leave individuals prone to difficulties in adapting to new circumstances … (Adams and Marshall 1996, pp. 431–432).

The identification of the second set of tasks—the formation of a societal identity—derives more directly from Erikson’ psychosocial stage formulations. In terms of Erikson’s overall stage hierarchy, the identity stage is preceded by the industry stage and followed by the intimacy stage. There are no clear boundaries between these stages and considerable overlap may exist. In fact, according to Erikson, “nobody… in life is neatly located in one stage; rather persons can be seen to oscillate between at least two stages and move more definitely into a higher one only when an even higher one begins to determine the interplay” (1978, p. 28). For the young adult, resolving the identity stage requires a sufficiently adequate resolution of the (preceding) industry stage, and while this might be resolved substantially for someone at the ego level with a sense of competence, at the social level, work roles that allow for the exercise of the sense of industry can be elusive in contemporary Western societies. Indeed, it is the extra time required to assume full-time work roles that now seem to delay the transition to adulthood for a substantial proportion of the population (e.g., Côté and Allahar 2006).

At the same time, Erikson saw the development of a sense of fidelity, or commitment to a worldview, to be an essential anchor for an adult identity. A coherent worldview that is shared with others provides a sense of purpose and direction as well as a justification for the adult roles assumed.

Viewed in terms of the challenges posed by Western secularized societies that require people to undergo a certain amount of “individualization” during the transition to adulthood to compensate for destructured social markers (e.g., the transition to adulthood), disjunctive transitions (e.g., education to work), and deconstructed ideologies (e.g., gender and marriage norms) (cf. Côté 2002), the specific nature of the developmental tasks can be specified as follows, taking into account the three levels of analysis for each:

Self-Identity Tasks

Integration Integration generally refers to the sense of wholeness, where the various spheres of experience are brought together in some unified way. Applied to self-identity, this sense of unity can be found, variously, in the inner mental world of the person, the immediate world of day-to-day behavior, and the more abstract arena of social functioning in (concrete, remote, and imagined) communities, as per the three levels of analysis, respectively. Thus, to lack this sense of unity—the dystonic experience—is to feel (a) mentally confused in term of temporal-spatial continuity, (b) fragmented in terms of one’s day-to-day activities and relationships, and (c) alienated from organized community involvements.

Differentiation The process of differentiation begins with the individuation process of childhood where the infant develops a sense of self as distinct from caregivers and significant others (i.e., basic ego boundaries). The individuation process now likely morphs into the individualization process during the transition to adulthood in secularized societies to the extent that the young must make decisions independent of social norms and guidance from significant others (i.e., they individualize), particularly in terms of their behavioral repertoire (Côté 2002). At the same time, contemporary Western societies also require “economic individualism” (Côté 2000): adult citizens are expected to function as self-sufficient economic units, or partners in one, in their social roles. Hence, syntonically, at the subjective level, (a) individuated people feel a sense of being their own person in terms of differentiating themselves from others in their lives; (b) at the behavioral level, individualized people have a sense that their life has a uniqueness that is of their own choosing; and (c) at the social role level, self-sufficient individuals feel that they have found a unique, self-sustaining niche in their community. To lack these senses of differentiation is to experience the dystonic senses of (a) an overwhelming engulfment by certain others in one’s immediate life, (b) a lack of behavioral control over, and uniqueness of, one’s life, and (c) an excessive sense of dependency on one’s family, community, or society.

Social-Identity Tasks

Work Roles The “work task” of the transition to adulthood involves an investment of self in acquiring and exercising skills in order to participate in productive activities that contribute to a wider community in some way. In Eriksonian terms, people’s (stage four) sense of industry merges with their (stage five) sense of identity, such that they come to define themselves in part in terms of their productive contributions (which can include parenting and homemaking roles). In terms of dystonic elements, those without this task completion experience (a) lack a sense of competence associated with productive skills, (b) will not feel recognized by others as possessing significant work skills, and (c) will not have productive work roles in their society.

Worldview The development of a worldview is a central task of identity formation as identified by Erikson (1968). A worldview provides people with a source from which to derive a sense of meaning and purpose in life in terms of some “thing” larger than themselves. This “thing” could be an organized religion, a political party, or a wider, diffuse ideology like humanism, technologism, or scientism. Dystonically, the person without this sense (a) lacks a sense of purpose rooted in a system of beliefs, (b) does not have articulated positions on relevant issues, and (c) does not adhere to an informal or formal belief system in religion, politics, science, humanism, and the like.

Table 1 presents the four tasks, with each of the three underlying levels defined, and representative items in each of the 12 cells that map the constructs. The actual scale items are presented in “Appendix.”

Research Questions

Using these four identity tasks, and the three underlying, interrelated dimensions, as a guide, we began the task of creating a measure of identity formation suitable to conditions of a prolonged transition to adulthood in secularized societies wherein people must resolve numerous issues for themselves in the absence of clear societal norms. Several research questions were developed to help assess the validity of the measure of identity issues.

First, does the instrument demonstrate sufficient factorial validity and internal consistency?

Second, does the instrument have predictive validity, in this case, showing a relationship with an important area of functioning: mental health. Previous research indicates that the transition to adulthood is associated with increases in well-being (e.g., Aseltine and Gore 1993; Schulenberg and Zarrett 2004; Gore et al. 1997; Schulenberg et al. 2004a, b). Schulenberg et al. (2004a, b) found overall increases in mental health as age increased but with a variety of individualized trends for different groups. Specifically, they found that youth—longitudinally measured at three ages (18, 22 and 26)—who had consistently high scores of well-being at all three ages, scored highly on developmental tasks associated with (the main effects of) education, work, and citizenship. Those who scored consistently lower on measures of well-being at all three ages had lower than average (deviation) scores on education, work, romantic involvement, peer involvement, and citizenship. Overall, they found that the dimensions of work, romantic involvement, and citizenship were particularly important for psychological health. When they tested for threshold effects for general achievement (work and education) and affiliation (romantic and peer involvement), they found both were necessary to maintain a solid sense of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Thus, the research of Schulenberg et al. (2004a, b) indicates that there are fundamental tasks to be achieved during the transition to adulthood that are associated with well-being. Therefore, in testing the predictive validity of the I3, it was hypothesized that higher scores of identity resolution would be associated with better mental well-being outcomes.

And, third, are there age-based threshold points at which problematic, adequate, and optimal resolutions of identity issues can be identified; for example, do those who experience delayed identity formation show evidence of psychological difficulties?

Methods

Sample 1

Convenience sampling was combined with snowball sampling to include participants beyond the university-attending age range. For example, stock cards describing the study were passed out randomly in public places and retail establishments in a mid-sized Canadian city to people roughly aged 18–40. The stock cards contained a URL for the online survey and a pass code to obtain access. Participants were also recruited via email, asked to fill out the survey, and then to forward through e-mail the URL and the pass code to others whom they thought might participate. The final sample comprised 196 participants (131 females, 2 not specifying) ranging in age from 18 to 48 (M = 29.6, SD = 5.8). About two-thirds of the sample were in the labor force, 3 % were unemployed, about one quarter were in school, and a minority were involved in other activities (e.g., travel, homemaker, illness/temporary leave). Participants, on average, had spent 4.8 years in post-secondary education (SD = 2.8). The majority of participants (80.5 %) reported making less than $60,000.

Sample 2

We collected a second sample using a crowdsourcing company called Mechanical Turk. Participants were directed to an online survey and were paid $.50 for completing the survey. The final sample comprised 1,489 participants (49 % females, 51 % males, three not specifying) ranging in age from 18 to 41 (M = 25.4, SD = 5.6). About two-thirds of the sample were in the labor force (check all that apply format allowed for multiple responses), 31 % were in school fulltime, 18 % unemployed and looking for work, and a minority were involved in other activities (e.g., travel, homemaker, illness/temporary leave). Participants, on average, had spent 3.5 years in post-secondary education (SD = 2.3). The majority of participants (90.1 %) reported making $60,000 or less.

Measures and Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained for sample 1 from the Research Ethics Board for Non-Medical Research Involving Human Subjects at the University of Western Ontario. Ethics approval for sample 2 was obtained from the Research Ethics Board for Non-Medical Research Involving Human Subjects at the University of Waterloo. The surveys took approximately 30–45 min to complete.

Variables

The Identity Issues Inventory (I 3 ) The items making up the Identity Issues Inventory are provided in “Appendix.” The I3 was developed based on the assumption that researchers would assess identity formation in terms of four tasks (integration, differentiation, work, and worldview). An original pool of 96 items was created for the I3. The societal-identity tasks were based on Adams and Marshall (1996), and the self-identity tasks were based on Arnett’s (2004) theoretical formulations on emerging adulthood, which is rooted in Erikson’s epigenetic model of psychosocial development. Both Adams and Arnett examined our original items for face validity and contributed to the overall continuity in phrasing.

Age and Gender Age was treated as a continuous variable and was normally distributed in both samples [skewedness and kurtosis results were satisfactory; (±2)]. Gender was coded as 1 = female and 0 = male.

Psychological Health Variables (Somatic and Emotional Indicators) For sample 1, we created a two-factor latent variable that represented psychological health in the analysis. Somatic indicators captured the physical manifestation of psychological health, while the emotional indicators captured the emotive manifestations of psychological health. These measures were derived from the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview (e.g., Kessler et al. 1998). The items utilized a five-point scale. A series of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed to select the items in the scales that were used in the structural equation modeling (SEM); in this process, a number of factorially complex items were eliminated. One latent psychological health variable was created and represented by two subscales reflecting emotional (worthless, sad, depressed, and anxious) and somatic indicators (restless, back pain, trouble sleeping, and being overly tired). Both indicators had adequate internal consistency (emotional health, α = .79; somatic health, α = .69), and both were within an acceptable range for skewedness and kurtosis (±2), so no transformations were performed.

Both somatic and emotional measures were used to represent two dimensions of the latent variable Psychological Health in the SEM analysis. However, in the additional analysis, where a single dependent psychological health variable was assessed (no latent variable), only the emotional measure of psychological health is presented to avoid repetition (note: the analysis of the physical indicators of mental health for the most part yield the same general trends).

For sample 2, due to the need for brevity in the survey, we used two continuous items to measure health (scored 1 = poor to 10 = excellent), worded as follows: in general, how would you rate your overall physical health, and in general, how would you rate your overall mental health. Both items were normally distributed (M = 7.1, SD = 1.9 and M = 7.2, SD = 2.2, respectively).

Results

Factorial Validity

From the original pool of 96 items, we reduced the number of items in the final version of the inventory to 48 items—12 items for each of the four primary subscales, with these subscales represented by an equal number of items from each of the three levels of identity (ego, personal, and social). Using sample 1, we reduced the items in the I3 based on a combination of confirmatory factor analyses (using modification indices in AMOS 21), skewedness tests, and kurtosis tests.

Table 2 presents the Cronbach’s alphas reliability coefficients, means, standard deviations, confirmatory factor analysis information (RMSEA, CFI), and number of items for the subscales. All of the alphas were acceptable (.77–.85). When all of the subscales were analyzed (12 items per subscales) in SPSS, using ML estimation, non-orthogonal rotation, the scree plots (Preacher and MacCallum 2003) indicated that single dimensions for each of these scales were satisfactory. The bivariate correlations (r) among the four subscales ranged from .44 to .83, indicating that the tasks are moderately to strongly correlated. The I3 (summing the four primary subscales) represents a global measure of identity stage resolution and has a potential range from 48 to 288, with each primary subscale potentially ranging from 12 to 72 (integration, differentiation, work, worldview). The participants’ scores in sample 1 ranged from 129 to 285 (M = 219.1, SD = 32.0). In sample 2, the I3 ranged from 87 to 275 (M = 192.8, SD = 29.4).

A traditional, second-order confirmatory factor analysis was completed on sample 2 that took into account all of the cross-factor loading of the items across the measures, which was stable (RMSEA = .05, GFI = .91; CFI = .90). Due to the complex pattern, we opted to test the predictive ability of a simpler model, where each of the 12 items from each subscale was aggregated into a single score. We examined these constructed scales using both factor-weighted scores and unweighted scores. No significant differences were found in any of these tests, so we continued analyses with the unweighted subscales. Thus, an overall measure with the stable, aggregated subscales was tested in a confirmatory factor analysis. The structure was stable in both samples (RMSEA .05; CFI .99).

Predictive Validity: Identity Issues Inventory and Psychological Health

Using sample 1, SEM was used to assess the ability of the I3 to predict psychological health, taking into account gender and age. Modification indices were used to adjust the model. Figure 1 presents this model, which has an excellent fit (χ2 = 15.61, df = 17, ns; RMSEA = .00; CFI = 1.00).

The SEM model shows that a one standardized unit increase in identity issues resolution (the total I3 score) predicted a b = .61 standardized unit increase in psychological health (p < .001). These results also indicate that psychological health is represented by more variance in the emotional (r 2 = .81) than the somatic measure (r 2 = .62).

As one would expect with a developmental measure, age significantly predicted higher scores in identity issues resolution, where a one standardized unit increase in age predicted a b = .40 standardized increase in identity resolution (p < .001).

The effect of gender was also explored in this model, with the finding that there were no gender differences in identity issues resolution. However, gender significantly predicted psychological health, with females scoring lower (a b = −.19 standardized difference). These results were then replicated in sample 2 (RMSEA = .07; CFI = .97) where all of the factor loads remained strong and directionally identical (integration r 2 = .89; differentiation r 2 = .91; work r 2 = .72; worldview r 2 = .63) for the subscales associated with the I3. Age predicted identity (b = .24) and work (b = .09), and identity predicted the latent health variable (b = .59) as did sex (b = −.20), and health was represented by both physical (r 2 = .51) and mental health (r 2 = .94) indicators.

Age Thresholds in Identity Development

To examine the relationships between age and identity issues resolution, the sample was divided into three categories representing age spans that have been associated with specific developmental periods: 18–25 (n = 53; 863), 26–29 (n = 57; 289), 30+ (n = 86; 337) in samples 1 and 2, respectively. Bivariate analyses were undertaken in these age comparisons.

First, a series of one-way analyses of variance show that there are significant increases in the scores of identity issues resolution across age for each of the tasks (Table 3). These trends are consistent in both samples 1 and 2. In addition, the post hoc tests suggest the following regarding developmental thresholds: integration differentiation, work, and worldview tend to show developmental increases across the age categories. The directional trends found in sample 1 are replicated in sample 2. The overall I3 score, too, shows significant increases with each age-grouping. These findings were also replicated in sample 2.

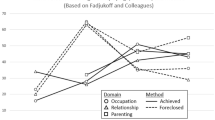

Second, optimal and problematic developmental thresholds were further explored with the aid of the emotional psychological health measure, based on the logic that significant delays in resolving identity issues have certain causes or consequences in terms of psychological functioning. The samples were split into tertiles to represent high (n = 66; 504), medium (n = 65; 484), and low (n = 65; 500; in samples 1 and 2, respectively) overall identity issues resolution to investigate “on time” and “delayed” identity formation. A univariate general linear model was used to assess the relationship between three levels of identity (low, mid, and high tertiles) and age (categories: 18–25, 26–29, 30+), and the interaction between identity level and age category on psychological health.

Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations of this analysis from the two samples. In sample 1, significant main effects were found in overall psychological health for the three levels of identity, F(2,187) = 11.17, p < .001. Age had no significant impact on emotional psychological health, F(2,187) = .46, ns. However, the interaction term (age and identity) was significant, F(4,187) = 2.99, p < .05.

Figure 2 displays the interaction between identity and age as they relate to emotional health: Those who are over 30 with the lowest level of identity issue resolution have the poorest emotional health (significantly different from the medium and high levels of identity resolution in the 30+ age category). Tukey’s post hoc tests found no significant differences in emotional psychological health among the high-, medium-, and low levels of identity for either of the 18–25 and 26–29 age categories.

These findings were partially replicated by sample 2. It is clear that those aged 30+ in the lowest identity tertile had overall the lowest scores of mental well-being. However, the interaction between age and identity was not significant. While there were no significant differences between the age-groups in the low and high identity groups, significant differences were found those who were in the mid level of identity where those who were 30+ had significantly lower levels of mental health. It should be noted that we were unable to have identical dependent variable measures for this particular test, and this may have impacted the results. Regardless, the trends provided in sample 2 indicate that those who are no longer in their early-20s and are not resolving their adult identities in a timely fashion tend to have lower scores on mental health measures.

Discussion

The SEM reveals that the four-indicator identity model has a stable structural fit, providing evidence of validity for the Identity Issues Inventory (I3; confirmatory factor model). In terms of the I3’s developmental sensitivity in assessing identity issues resolution beyond adolescence, there is a steady and significant increase in scores through the twenties and into the thirties, providing verification that identity formation continues beyond adolescence in the (now) prolonged transition to adulthood. At the same time, the variation suggests that a significant proportion of respondents may be stalled or delayed on key identity issues associated with the assumption of an adult identity, and this delay may have mental health causes or consequences (these cross-sectional data sets do not allow us to determine causality). Thus, it appears that these types of identity formation (now) continue into the late-twenties and thirties and beyond for a significant proportion of the population.

Several observations can be made about the potential of the I3 to help sort out some of the competing interpretations regarding the significance of the prolonged transition to adulthood.

First, these findings support the widely held view that identity formation is now more prolonged and individualized than in the past (e.g., Côté and Roberts 2005), but identity formation itself does not appear to be as highly fragmented as some postmodernists claim (e.g., Gergen 1991; Rattansi and Phoenix 2005). To the contrary, the four tasks of identity formation are moderately to highly correlated, even for those in their early-20s, suggesting that most people are able to develop a unified sense of identity. What will be of interest in future investigations is a closer examination of those people for whom the tasks are not unified. This analysis awaits the collection of data with additional samples and targeted groups for whom identity formation may be particularly problematic (e.g., those seeking mental health or career counseling or who continue to engage in high-risk behaviors beyond adolescence). This assessment of postmodernist claims can also be adjudicated with information on the rate and timing of identity development in different cultural contexts. If the postmodernist claims are valid, then most people should not be developing mature identities, but instead be arrested at lower levels of self-identity (e.g., poor integration) and societal identity (e.g., an absence of coherent worldview), and they should not show integrated resolutions (i.e., the levels and domains should not be even moderately correlated). The data from the current studies tentatively suggest that this is not the case.

Second, the measure appears to be well suited to assessing other claims about identity formation in the prolonged transition to adulthood, such as the positive benefits of emerging adulthood as postulated by Arnett (2000). When norms are developed based on larger population surveys, various aspects of the now prolonged period of identity formation can be empirically assessed in terms of how identity formation proceeds during this period, on average and for various subgroups. For example, the I3 can detect various patterns of identity formation, including delays and plateaus in certain types of identity development, and these modest studies found evidence of arrest and plateauing among subsamples that need to be further investigated with longitudinal studies. These patterns can then be more closely examined, especially delays in identity formation that might be associated with mental health problems, and the extent to which delayed identity resolutions are either the cause or consequence of mental health issues and developmental attributes like personal agency (cf. Schwartz et al. 2005).

Future Research

Regardless of cause and effect issues, the Identity Issues Inventory shows promise as a useful instrument in mapping the effects of the increasingly prolonged transition to adulthood in late-modern societies, where significant individualized “identity work” is apparently necessary to reach the levels of maturity in self-identity and societal identity now required for resolution of the identity stage. The evidence examined above shows that those who are over 30 years of age and older are significantly more developed in all domains of identity formation than both younger age-groups and are closer to the “ceiling” of the subscales in terms of task mastery. This is exactly what one would expect of scales operationalizing resolution of the issues associated with the identity stage and the acquisition of a mature, integrated identity. In addition, it appears that those who show less mastery of these tasks have challenges related to psychological health.

Future research can also investigate the development correlates of these types of identity formation. In fact, while we were developing this instrument, we shared its prototype with several researchers. Leslie (2011) reports that the total I3 correlates positively with age and perspective taking and negatively with egocentrism and “personal fable” (a sense of invulnerability and specialness) in a sample of American 18–25 year olds. Erdogan (2012), in a study comparing Burmese (Karen) refugees relocated to Canada with a comparable group of native born Canadians, found significant associations of the I3 with age and mental health, but also with other measures of identity formation (temporal continuity, identity crisis resolution, and lower levels of identity distress). And, Schwartz et al. (2010) found significant associations between two subscales of the I3 (subjective and behavioral integration) with better avoidance of health-compromising behaviors in a multisite sample of 1,546 American university students, with invariance across gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and living arrangements (living with parents, or not). The I3 is also being used as predictors of body image and eating disorders (Roberts and Fuentes 2013), where greater resolution of the transition to adulthood, as measured by the I3, predicts less eating disordered behavior and better body image. A study of the impact of unemployment on the transition to adulthood has also found that gaps in employment of 6 months predicted lower scores on the I3 (Swinarton and Roberts 2013). Finally, the I3 is being used to aid studies of the furry fandom (e.g., Plante et al. 2012). The first-ever longitudinal study of furries (Plante et al. 2014) employs the I3 to predict outcomes related to being part of the furry fandom.

More generally, profiles of the rate of resolution of these identity issues of diverse populations of groups and in various countries will help us understand cross-cultural differences in the role of identity formation in the transition to adulthood [Erdogan (2012) successfully translated the I3 into the Karen language]. In addition, the I3 has now been translated into Japanese, and cross-cultural identity comparisons are underway. It would be predicted that societies that provide more normative structure for this transition will produce different norms on the I3 that reflect a quicker rate and earlier timing of identity formation than those that are not as well structured or regulated (e.g., comparisons with more “traditional” or collectivist societies or communities should reveal significant contrasts with late-modern ones). Thus, if identity formation is associated with the transition to adulthood in the ways described above, the I3 promises to be useful in making cross-cultural comparisons to determine whether the rate of progress through these identity formation tasks differs according to (a) well-structured cultural practices marking an earlier and more concrete transition to adulthood as well as (b) State youth policies directed at increasing individual autonomy and effective entry into the labor force. This information should also help to adjudicate debates, such as whether—and for whom—the prolonged transition to adulthood is beneficial as a preparation for adulthood, and when this delay can constitute a developmental challenge with negative consequences for the people affected.

References

Adams, G., & Marshall, S. (1996). A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 429–442.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J., Kloep, M., Hendry, L. B., & Tanner, J. L. (2011). Debating emerging adulthood: Stage or process?. New York: Oxford University Press.

Aseltine, R. H., & Gore, S. (1993). Mental health and social adaptation following the transition from high school. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 3, 247–270.

Bennion, D., & Adams, G. (1986). A revision of the extended version of the objective measure of ego identity status: An identity instrument for use with late adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1, 183–197.

Clark, W. (1998). Religious observance: Marriage and family. Canadian Social Trends, 50, 2–7.

Clark, W. (2007). Delayed transitions of young adults. Canadian Social Trends, 84, 13–21.

Clark, W., & Schellenberg, G. (2006). Who’s religious? Canadian Social Trends, 81, 2–9.

Constantinople, A. (1969). An Eriksonian measure of personality development in college students. Developmental Psychology, 1(4), 357–372.

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Côté, J. E. (2000). Arrested adulthood: The changing nature of maturity and identity. New York: New York University Press.

Côté, J. E. (2002). The role of identity capital in the transition to adulthood: The individualization thesis examined. Journal of Youth Studies, 5(2), 117–134.

Côté, J. E. (2006a). Identity studies: How close are we to developing a social science of identity? An appraisal of the field. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 6(1), 3–25.

Côté, J. E. (2006b). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Côté, J., & Allahar, A. (2006). Critical youth studies: A Canadian focus. Toronto: Pearson.

Côté, J. E., & Bynner, J. (2008). Changes in the transition to adulthood in the UK and Canada: The role of structure and agency in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 11(3), 251–267.

Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. (2002). Identity formation, agency and culture: A social psychological synthesis. Mahwah. NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Côté, J. E., & Roberts, S. E. (2005). Identity Issues Inventory (III): Preliminary manual. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Erdogan, S. (2012). Identity formation and acculturation: The case of Karen refugees in London, Ontario. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1978). Adulthood. New York: W. W. Norton.

Erikson, E. (1979). Report from Vikram: Further perspectives on the life cycle. In S. Kakar (Ed.), Identity and adulthood. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

Fadjukoff, P., & Pulkkinen, L. (2005). Identity processes in adulthood: Diverging domains. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 5, 1–20.

Gergen, K. J. (1991). The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. New York: Basic Books.

Gidengil, E., Blais, A., Nevitte, N., & Nadeau, N. (2003). Turned off or tuned out? Youth participation in politics. Electoral Insight, 5(2), 9–14.

Gore, S., Aseltine, R. J., Colten, M. E., & Lin, B. (1997). Life after high school: Development, stress and well-being. In B. Wheaton & I. H. Gotlib (Eds.), Stress and adversity over life course: Trajectories and turning points (pp. 197–214). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grotevant, H. D., & Cooper, C. R. (1986). Individuation in family relationships. Human development, 29(2), 82–100.

Kessler, R., Wittchen, H., Abelson, J., Mcgonagle, K., Schwarz, N., Kendler, K., et al. (1998). Methodological studies of the composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) in the US national comorbidity survey (NCS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7(1), 33–55.

Leslie, M. (2011). Egocentrism, perspective-taking, and identity development in emerging adulthood. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Long Island University, New York, USA.

Marcia, J. (1964). Determination and construct validity of ego identity status. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Andelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley.

Papini, M. (1994). Family interventions. In S. Archer (Ed.), Intervention for adolescent identity development (pp. 47–61). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and insights from 20 years of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students, vol. 2: A third decade of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Plante, C., Freeman, R. S., Gerbasi, K. C., Roberts, S., & Reysen, S. (2012). International anthropomorphic research project: Anthrocon 2012. Unpublished raw data. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/anthropomorphicresearch/past-results/anthrocon-2012-iarp-2-year-summary.

Plante, C., Reysen, S., Roberts, S., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2014). International anthropomorphic research project: Longitudinal study wave 2. Unpublished raw data. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/anthropomorphicresearch/past-results/2014-furry-fiesta.

Preacher, K. J., & MacCallum, R. C. (2003). Repairing Tom Swift’s electric factor analysis machine. Understanding Statistics, 2(1), 13–43.

Rasmussen, J. E. (1964). The relationship of ego identity to psychosocial effectiveness. Psychological Reports, 15, 815–825.

Rattansi, A., & Phoenix, A. (2005). Rethinking youth identities: Modernist and postmodernist frameworks. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 5(2), 97–123.

Roberts, S., & Fuentes, H. (2013). I, in the mirror: Examining the associations between identity resolution, body image, and eating disorders symptomology. Presented at the Society for Research on Identity Formation conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 16–19.

Schlossberg, N. K. (1989). Marginality and mattering: Key issues in building community. New Directions for Student Services, 48, 5–15.

Schulenberg, J., Bryant, A., & O’Malley, P. (2004a). Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology [Special Issue: Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood], 16(4), 1119–1140.

Schulenberg, J. E., Sameroff, A. J., & Cicchetti, D. (2004b). The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 799–806.

Schulenberg, J. E., & Zarrett, N. R. (2004). Mental health during emerging adulthood: Continuities and discontinuities in course, content, and meaning. In J. J. Arnett & J. Tanner (Eds.), Advances in emerging adulthood. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schwartz, S. J., Côté, J. E., & Arnett, J. J. (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37(2), 201–229.

Schwartz, S. J., Forthun, L. F., Ravert, R. D., Zamboanga, B. L., Rodriguez, L., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., et al. (2010). Identity consolidation and health risk behaviors in college students. American Journal of Health Behavior, 34, 214–224.

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Luyckx, K., Meca, A., & Ritchie, R. A. (2013). Identity in emerging adulthood: Reviewing the field and looking forward. Emerging Adulthood, 1, 96–113. doi:10.1177/2167696813479781.

Simmons, D. D. (1973). Development of an objective measure of identity achievement status. Journal of Projective Techniques and Personality Assessment, 34, 241–244.

Statistics Canada (2003). 2001 Census: Analysis series religion in Canada, Cat. No. 96F0030XIE2001015. Ottawa: Author.

Swinarton, L., & Roberts, S. (2013). The impact of job stability on the resolution of identity during the prolonged transition to adulthood. Presented at the Society for Research on Identity Formation conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 16–19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Items for the Identity Issues Inventory (V1)

Appendix: Items for the Identity Issues Inventory (V1)

Integration

-

1.

I feel like I have grown into a “whole” person.

-

2.

Whatever happens, I still have a secure sense of who I am deep inside.

-

3.

*I often feel confused about who I am deep inside.

-

4.

*There is a struggle inside of me about who I really am.

-

5.

My friends think I behave maturely.

-

6.

My friends and family see me as a responsible person.

-

7.

*I act like a different person, depending on the social situation.

-

8.

*People who know me well often treat me like I’m immature.

-

9.

I belong to a community of like-minded people with whom I will be happy to closely associate indefinitely.

-

10.

I am recognized as an adult member of an established social group.

-

11.

*I have been unable to find a meaningful group of like-minded people with which to affiliate on a more or less permanent basis.

-

12.

*I have not been able to become a member of a “community” that will support who I am.

Differentiation

-

13.

I feel like I have fully matured into being my own person.

-

14.

I am in control of my own emotions.

-

15.

*I have a difficult time thinking and acting decisively.

-

16.

*Sometimes other people feel like I rely on them too much emotionally.

-

17.

Most of the time, I dress and act in ways that reflect the kind of person that I really am.

-

18.

My behaviour is generally consistent in all situations.

-

19.

*I continually change the way I present myself to others to get the best out of the situation I’m in.

-

20.

*If I think someone won’t approve of me, I pretend to have characteristics that I don’t really possess.

-

21.

I have found my niche (unique place of belonging) in life.

-

22.

Others would recognize me as a self-sufficient adult.

-

23.

*I have not been able to achieve the type of self-sufficiency expected of an adult.

-

24.

*I’m still not sure where I fit in adult society.

Productive/Work Roles

-

25.

I have certain abilities that make it possible for me to be effective in the work I choose to undertake.

-

26.

I think of myself as a competent person who makes productive contributions to society.

-

27.

*I really don’t know if I have the right talents to maintain a good job.

-

28.

*I do not feel like I have the necessary skills to get (or keep) the kind of job I would really like to have.

-

29.

People in my life think that I have some useful talents or skills.

-

30.

I have certain skills or talents that I use in my life.

-

31.

People who know me recognize me in terms of certain talents and skills.

-

32.

*When people think of who I am, they do not associate me with any specific talents or skills.

-

33.

I have as much formal education as I ever wanted to get.

-

34.

I have a job (or homemaking role) that I am happy keeping for the foreseeable future.

-

35.

*I do not yet have the educational credentials necessary to get the kind of job I would ultimately like to have.

-

36.

*I have yet to find a job (or homemaking role) that would gain me the respect I deserve.

Worldview

-

37.

My beliefs and values relate to something that is much more important than my own individual needs.

-

38.

My beliefs and values provide me with a firm sense of purpose in life.

-

39.

*My beliefs and values are mostly geared to satisfying my own immediate needs.

-

40.

*My sense of purpose in life mainly involves gratifying my own immediate, personal needs.

-

41.

I often speak up about what I believe in.

-

42.

People in my life know me as someone with firm beliefs and values.

-

43.

I make sure that my day-to-day behaviour reflects my underlying beliefs and values.

-

44.

*People in my life do not know me as someone with consistent beliefs or values.

-

45.

I live my life in way that is consistent with a firm set of values and beliefs (religious, political, secular or otherwise) associated with some organized groups.

-

46.

Other people know me as a member of a social group that espouses strong values and beliefs.

-

47.

*The way that I live my life is not based on any widely accepted religious or political beliefs.

-

48.

*Others do not generally think of me as someone who commits to any causes or organized beliefs systems.

Scales run from 1 to 6 (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree, strongly agree). Items with (*) need to be reverse coded. Items should be scrambled.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, S.E., Côté, J.E. The Identity Issues Inventory: Identity Stage Resolution in the Prolonged Transition to Adulthood. J Adult Dev 21, 225–238 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9194-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9194-x