Abstract

Individuals with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have a greater number of healthcare provider interactions than individuals without ASD. The obstacles to patient-centered care for this population, which include inflexibility of hospital environments, limited resources, and inadequate training, has been documented. However, there is little knowledge on efforts to address such concerns. A scoping review was conducted and the systematic search of the literature resulted in 23 relevant studies. The predominant themes include the use of data collection instruments, application of evidence-based practices and resources, and training of providers. The results of this review have implications for practitioners and future research to adapt and improve upon the provision of medical care for individuals with ASD across the lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As the fastest growing developmental condition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network estimate that 1 in 54 children are diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the United States (Maenner et al. 2020). Individuals with ASD are a fundamentally heterogeneous population with variability in severity as it relates to both verbal and nonverbal social communication and interaction, and with regards to restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). These conditions impact the entire lifespan of the individual (Boyle et al. 2011).

Providing optimal care for patients with ASD and their families is becoming increasingly difficult due to potential needs related to strict adherence to routines, sensory defensiveness, and coexisting healthcare comorbidities (Gurney et al. 2006; Suarez 2012; Zwaigenbaum et al. 2016). It is estimated that more than 70% have comorbid conditions, with the most common medical concerns involving neurological, gastrointestinal disturbances and respiratory issues (Iannuzzi et al. 2015; Lai et al. 2014; Lui et al. 2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, generalized anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) are also coexisting conditions in the population (Kiln et al. 2005). Additional psychiatric concerns include externalizing symptoms such as aggression and self-injury, and internalizing symptoms such as mood disturbances (Iannuzzi et al. 2015; Lui et al. 2017).

These coexisting medical comorbidities result in a greater number of healthcare interactions (Liptak et al. 2006). According to Croen et al. (2006), and Gurney et al. (2006) children with ASD had a higher annual mean number of total clinic, pediatric, and psychiatric outpatient visits, and inpatient and outpatient hospitalizations when compared to children without ASD. Individuals with ASD also visit the emergency department (ED) at higher rates, with studies reporting that adolescents with ASD access ED services up to four times as often as their neurotypical peers (Iannuzzi et al. 2015; Lui et al. 2017; Nicholas et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2015).

The medical environment presents several challenges for patients with ASD, such as unpredictably long wait times, loud noises, novel or aversive smells, bright lighting, and continual movement of healthcare staff, patients and families from one location to another (Carter et al. 2017; Johnson et al. 2014a, b; Scarpinato et al. 2010; Giarelli et al. 2014; McGonigle et al. 2014a, b; Vaz 2010). Thus, the need to adhere to routines, and difficulty with transitions may then lead to challenging healthcare interactions (Nicholas et al. 2016; Zanotti, 2018). Cooperation with healthcare providers may also be difficult due to a limited ability to communicate and understand what is occurring (Davis et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2014a, b).

Several studies gathering the perspectives of families of individuals with ASD with regards to their experiences during medical encounters depict overwhelming dissatisfaction. Parents have reported frustrations related to the lack of knowledge healthcare providers had in regards to the individual complexity of ASD and how to effectively communicate and address behaviors, as well as perceived disregard for the concerns expressed by families (Bultas 2012; Minnes and Steiner 2009; Rhoades et al. 2007). Parents also reported concerns about whether medical settings were prepared and knowledgeable enough to address anxiety and challenging behaviors exhibited by patients with ASD to ensure their success with medical procedures (Bultas 2012; Kopecky et al. 2013; Johnson and Rodriguez 2013).

Healthcare providers have also reported concerns surrounding appropriate management of externalized behaviors, safety, and effective medical care within the constraints of medical environments (Balakas et al. 2015; Broder-Fingert et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2012; Mayes et al. 2012; Rhoades et al. 2007). These concerns include a pressing need for advanced education, training, and resources to increase comfort, confidence, and safety in addressing the variable needs of patients with ASD. Healthcare providers are seeking training to identify antecedents to fear, anxiety, and stress, and to proactively prevent escalating behaviors such as using strategies to effectively communicate with patients (Johnson et al. 2012; Scarpinato et al. 2010). The limited formal training, experiences, and resources identified by healthcare providers poses a risk to the treatment of patients with ASD with particular regard to the use of pharmacological sedation or physical restraints (Kamat et al. 2018; McGonigle et al. 2014a, b).

Patients with ASD benefit from the same health-promotion and disease-prevention priorities, and have the right to ethical medical care without discrimination (Myers and Johnson 2007; WHO 2013). Yet, patients with ASD experience a lack of family-centered care, delayed or foregone medical care, and obstacles in obtaining referrals (Johnson and DeLeon 2016; Karpur et al. 2019; Kogan et al. 2008). Unmet needs related to preventative care, mental health services, specialty and therapy services, and family support services are apparent in this patient population of patients as well (Chiri and Warfield 2012). Even in comparison to children without ASD that do have other special healthcare needs, patients with ASD experience an overall lower quality of healthcare (Zuckerman et al. 2014).

Purpose of the Scoping Review and Guiding Questions

Providing an ethical standard of healthcare for individuals with ASD, considering the increasing number of individuals identified, is of immense concern. A number of issues have been recognized by both families and healthcare providers which impact the delivery of patient- and family-centered care. A scoping review of the literature may provide a better understanding of what efforts have been made to respond and support the heterogenous needs of patients with ASD, and identify the limitations and challenges individuals may encounter in the medical setting. The literature will provide a basis for the further development and adoption of quality improvement initiatives and more effective supports for patients with ASD and their families. In addition to identifying the present efforts of medical settings to provide care for patients with ASD, which may also include training and the provision of supplementary resources to serve the population, it would be imperative to examine whether these efforts are grounded in scientific research. The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC; Wong et al. 2015) and National Autism Center (NAC 2015) have identified evidence-based practices for individuals with ASD. Some of these interventions include reinforcement, modeling, prompting, social narratives, task analyses, and visual supports. Though focused primarily in educational and therapeutic contexts, these effective practices may be generalizable to medical environments and provide a framework to examine the efforts conducted in medical settings.

Conversely, due to many of the same reasons already discussed that make medical visits challenging for children with ASD, many of the same practices commonly used in educational and therapeutic settings may be more challenging to implement in medical settings. Specifically, time and staffing constraints, lack of resources needed to train medical staff in utilizing specific interventions, and absence of predictable routine are all variables in medical settings that may limit the generalizability of certain interventions. Thus, a scoping review of the literature is necessary to identify interventions that have been successfully tested in medical settings, evaluated for efficacy, and were able to be easily implemented into existing workflows without need for hiring additional staff. The results of the review may further lead to the identification of implications for practitioners and future research, while also acknowledging the realistic constraints of medical settings which may obstruct the implementation of such efforts.

Therefore, the questions that will guide the scoping literature review and support the identification of themes and gaps in the literature are listed below:

-

1.

What tools and/or interventions have been implemented in healthcare settings to facilitate medical care that support the individual needs of patients with ASD and their families?

-

2.

Are these interventions aligned to the evidence-based practices found in educational settings?

-

3.

Do these efforts include education, training, and resources for healthcare providers?

-

4.

What are the implications of these studies for practitioners and future directions for research?

-

5.

What are the limitations and challenges associated with implementing these supports?

Methods

The aims of a scoping review are to map the existing body of literature on a topic, provide a descriptive overview, and identify gaps in the research (Arksey and O’Malle 2005; Levac et al. 2010). Therefore, a scoping review was conducted to search the literature to broadly determine what efforts have been made to support patients with ASD in medical settings, summarize the themes and gaps in the literature, and identify implications for practitioners and future research to continue to support patients with ASD.

Search Strategy

The methodology for this scoping review was grounded in the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). Therefore, the review included the following five key phases: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. The optional sixth stage was not conducted. The review was guided by the question, “What interventions have been implemented in healthcare settings to facilitate medical care that support the individual needs of patients with ASD and their families?”.

For the purposes of this review, a healthcare setting was defined as settings such as acute-care hospitals, physicians’ offices, urgent-care centers, inpatient and outpatient clinics, mental health services, and emergency medical services. The definition did not include dentistry, perioperative, ophthalmology, home healthcare (i.e., care provided at home by professional healthcare providers), and specific sites within non-healthcare settings where healthcare is routinely delivered (e.g., a medical clinic embedded within a workplace or school). The rationale for excluding dentistry and perioperative care is due to recent publications documenting the breadth of literature on how professionals in these medical environments have worked to facilitate care for patients with ASD (Isong et al. 2014; Koski et al. 2016). The definition of healthcare setting also did not include assessment settings for the diagnosis of ASD or supportive services, such as speech therapy, occupational therapy and social skills groups.

The initial literature search was conducted in February 2019 by a research librarian, and Covidence® and EndNote® software were utilized to manage the citations. The databases selected included: PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. The following databases were selected to ensure comprehensive coverage of all medical settings or specialties, while also recognizing the possible overlap between the fields of medicine and special education. The search query consisted of terms identified by the authors and research librarian to be related to ASD and healthcare settings. These key terms (see Table 1), were truncated or broadened to ensure widespread coverage, and the search query was tailored to the specific requirements of each database (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010). Date limits were not set, and all countries and healthcare systems were included. However, only literature available in English were included (Table 1).

Titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance utilizing a form developed by the authors. Citations were included if the title and abstracts referenced patients with ASD of any age, a medical setting as defined above, and described an intervention that was implemented or suggested to support the patient with ASD and/or their families. Due to the iterative methodology of scoping reviews, which allows for adjustment to the inclusion criteria to provide a broad overview of the literature, consensus discussions occurred between the authors to resolve any disagreements and ensure fidelity in applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Levac et al. 2010). The remaining citations were then collated for a review of the full-text article. Continuing to utilize the inclusion and exclusion criteria, any disagreements were resolved through consensus discussions. The reference lists of the remaining citations following the full-text review were manually searched to identify any additional literature, applying the same process of reviewing titles and abstracts, followed by the full-text review.

It is important to note that the authors decided to include articles with no empirical data to present suggestions identified by professionals to improve upon medical care for patients with ASD. Furthermore, this information may provide implications for future research.

Results

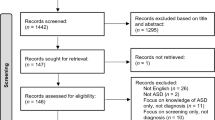

The literature search process is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 395 articles identified by the search, 83 (21%) were identified as duplicates. The first screening of titles and abstracts eliminated 280 articles. The primary rationales for excluding the studies were due to a focus on interventions conducted in the aforementioned excluded settings or other settings, or focus on early identification procedures of children with ASD. Following an examination of the reference lists of the 32 remaining articles for full-text review, an additional 31 studies were added to the full-text review. Based on the inclusion criteria stated above, the final decision was to exclude 40 of the 63 articles put forward for full-text review. Reasons for exclusion included: the incorrect setting, type of intervention, which did not aim to optimize medical encounters for patients with ASD, and incorrect study population (Fig. 1).

The final review included 23 studies (see Table 2) that focused on interventions have been implemented in healthcare settings to facilitate medical care that support the individual needs of patients with ASD and their families. The 23 included articles were published between 2002 and 2019, and 89.9% (n = 20) were published after 2010.

The included studies shared a number of methodological characteristics. Of the 23 included studies, 12 studies implemented a research design. Four of the 12 studies utilized a quality or performance improvement model (Johnson et al. 2012; Lucarelli et al. 2018; McGonigle et al. 2014a; Pratt et al. 2012). Three studies employed a cross-sectional survey design (Broder-Fingert et al. 2016; Bultas et al. 2016; Drake et al. 2012), and two conducted feasibility pilot studies (Chebuhar et al. 2013; Johnson et al. 2014a, b). The remaining three articles utilized retrospective chart review, case study, and survey respectively (Gabriels et al. 2012; Kennedy et al. 2016; Vaz 2013). Two studies implemented no design, but conducted initial intervention testing through the collection of anecdotal evidence and parental survey (Kennedy andBinns2014) and observations (Souders et al. 2002). Nine studies implemented no design or intervention testing (Carter et al. 2017; Jolly 2015; McGonigle et al. 2014b; McGuire et al. 2016; Samet and Luterman 2019; Scarpinato et al. 2010; Vaz 2010; Venkat et al. 2016; Zanotti 2018). These studies provided practice guidelines for medical settings and healthcare providers to be more cognizant and responsive to the needs of patients with ASD and their families.

Nine of the studies targeted emergency, intensive, or acute care settings. Five of the studies focused on general hospital, community health services, or pediatric primary care settings. Broder-Fingert et al. (2016), Jolly (2015), and Drake et al. (2012) examined inpatient settings, excluding nonmedical issues (e.g., psychiatric). Elective treatments and/or radiology clinics and burn services were the settings of three articles. Chebuhar et al. (2013) focused on pediatric specialty clinics and center for individuals with disabilities, and Gabriels et al. (2012) targeted children’s psychiatric inpatient program and neuropsychiatric special care program. Souders et al. (2002) targeted settings with difficult medical procedures (e.g., physical exam, phlebotomy, IV insertion), and Lucarelli et al. (2018) targeted eight outpatient hospital departments with a high volume of patients with ASD or departments with frequent procedures necessary for the population (i.e., urology, developmental medicine, psychiatry, phlebotomy, electroencephalogram, audiology, and two ambulatory satellite locations).

Patients with ASD were the primary recipients of the interventions in five of the included articles. Ages of the included participants in these studies ranged from 2 to 21 years of age, with sample sizes ranging from 32 to 142 patients with ASD. Four studies aimed to support pediatric, adolescent, and adults with ASD through recommendations and interventions implemented. Healthcare providers were the sole target of the intervention (i.e., training, implemented interventions) in four of the studies which included healthcare providers in addition to patients with ASD. Sample sizes ranged from 24 to 604 healthcare providers. Healthcare providers and parents were involved in the intervention in two of the articles.

In terms of facilitating medical encounters for the population, 11 studies implemented proactive interventions that involved collecting key information about the patient with ASD from families and developing a specific care plan. Of the 23 articles included, thirteen articles implemented an intervention or a package of interventions, which utilized evidence-based practices for individuals with ASD. Five studies focused on the provision of training for healthcare providers, and two studies involved appointing a staff leader to assist in care plan application and communication.

The first three aims of the scoping review involve the identification of tools and/or interventions, which may include education, training, and provision of resources, that have been utilized in healthcare settings, and whether these correspond to evidence-based practices identified by NPDC and NAC. In alignment with these aims, the following section further discusses the included studies separated according to three identified core themes, which include: (1) the use of tools and/or interventions to develop an individualized care plan for the patient with ASD, (2) application of evidence-based practices and resources, and (3) education, training, and resources for healthcare providers to support the individual needs of the population.

Tools and/or Interventions that have been Implemented in Healthcare Settings

Of the 23 articles selected for inclusion, 11 studies developed and/or implemented a data collection instrument to elicit information from families of patients with ASD. The instruments included prompts or questions related to receptive and expressive communication, social and pragmatic skills, sensory needs, strict adherence to routines, repetitive or stereotyped behaviors, safety and other behavioral concerns, interests and reinforcers. Additionally, instruments sought out interventions that were effective in past medical encounters, as well recommendations from families as it related to reducing agitation, clarifying expectations, communicating real-time concerns, and other suggestions and information. Such information was then used to develop and provide an individualized care plan of interventions and resources that addressed the unique needs of the patient with ASD.

Information Collecting Instrument

In order to improve delivery of care experiences for the population, four articles focused primarily on developing and utilizing an instrument to elicit information about the patient with ASD. These survey instruments were designed to either be completed prior to a planned admission to the hospital in the case of Broder-Fingert et al (2016) and Pratt et al. (2012), or to be completed on-the-spot in the case of an emergency or acute medical need such as in the case of Bultas et al. (2016) and Venkat et al. (2016). Broder-Fingert et al. developed an autism-specific care plan (ACP) to be completed prior to hospital admission and included questions which addressed three domains: expressive and receptive communication, social and pragmatic concerns, and safety. Similarly, Pratt et al. also developed and examined the impact of a structured checklist to elicit information during pre-admission. The checklist collected information on functional age, expressive communication, motivating factors and interests, challenging behaviors, and recommendations based on past or similar experiences or procedures.

In contrast, Bultas et al. recommended the use of a researcher-developed tool eliciting information from parents and was designed specifically to be completed on site. The Quick Tips Card (QTC) is a parent-driven tool used to communicate specific characteristics of the patient with ASD as it related to modes of communication, challenging behaviors, present mood, fears, real-time concerns, and idiosyncrasies. Venkat et al. (2016) also developed an instrument to collect information on communication and social ability, sensory, behavioral and dietary patterns, and vaccination and menstrual history. The instrument also collected information on sensory needs, communication of needs and pain, receptive communication, and medications. The survey tools all collected to some degree information pertaining to communication ability, sensory needs, and behavioral needs. Overall, both parents and providers responded favorably to the use of these survey tools in post-intervention surveys.

Package of Interventions

Six articles focused on both a data collection instrument and other interventions and resources to support patients with ASD. These approaches varied from protocol or algorithm-based approaches that could be universally applied to every patient to individualized care plans for each patient. Carter et al. (2017) suggested a package of interventions or toolkit to deliver ASD-centered care. The Admission Basic Checklist outlined a protocol of considerations when admitting a patient with ASD. These factors included specific orders, consultants, and environmental needs. The Clinical Care Algorithm leveraged and built upon preexisting resources or care plans to address limited verbal communication, certain behavioral triggers, and patient or family expectations of adult patients with ASD. A similar hospital-wide protocol was developed by Kennedy and Binns (2014), who implemented a hospital-wide, comprehensive intervention package that integrated an information form in conjunction with a patient passport, communication do’s and don’ts, social storyboards, and visual supports.

McGonigle et al. (2014b) recommended a more personalized approach by conducting an initial assessment interview to focus on crisis behaviors and the antecedents and consequences to such presenting behaviors. Following the interview, the authors recommend first addressing medical needs that may be causing behavioral agitation, and then address lingering agitation through environmental adaptations (stimulation, lighting, number of people), communication, behavioral and somatosensory interventions. In a similar manner, Scarpinato et al. (2010) and McGuire et al. (2016) developed individualized care plans unique to each patient after an initial assessment. After conducting a series of assessment components for each individual patient, Scarpinato et al. provided recommendations such as limiting the number of staff, addressing sensory input in the environment, communicating using preferred modes, and using visuals and other effective practices to address inflexibility, and restricted interests or stereotyped behaviors. McGuire et al. developed a practice pathway for pediatric psychiatry in order to provide an individualized care plan and address irritability and problem behaviors (I/PB).

Involvement of Nurses

Jolly (2015) provided a list of recommendations for nurses to implement to further understand the core features of ASD, identify modes of communication, include families, establish a routine, limit the number of clinicians, and adjust the environment to address sensory needs behavioral triggers and reinforcers. Jolly also recommended that nursing staff continually include families in the care process, and optimize future medical encounters by documenting information about the patient and disseminating such information with other medical staff caring for the patient. In a similar manner, Souders et al. (2002) developed an assessment which collected information on the unique communication, behavioral, and sensory needs, as well as effective strategies to encourage patient compliance. Nurses were trained to effectively implement behavioral strategies, which included role-playing, reinforcement, shaping, provision of choices, visuals, distraction techniques, and restraints.

Application of Evidence-Based Practices

Thirteen studies included as part of their patient-centered care plan evidence-based practices that are ubiquitous in educational settings. This demonstrates a bridging of both the medical setting and educational setting in working to improve medical care practices, and minimize trauma, stress, and anxiety experienced by patients, families, and healthcare providers. Some of these evidence-based practices include visual supports, schedules, social scripts, environmental modifications, sensory-based therapies and resources, and other Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) practices.

Visual Supports and Communication

Chebuhar et al. (2013) piloted picture schedules of procedures by photographing demonstrations of each step. The four to six step sequence of photographs were utilized along with verbal explanations. Based on survey responses, families reported decreased anxiety and distress for themselves and their child with ASD. Healthcare providers also reported that the use of pictures schedules was feasible and effective in facilitating medical visits. Similarly, Gabriels et al. (2012) applied daily and mini-routine picture schedules in a children’s psychiatric inpatient program and neuropsychiatric special care program along with other visual cues and social stories.

Kennedy and Binns (2014) applied social storyboards and visual supports to communicate to patients a sequence of procedures (i.e., now and next, then and this). Johnson et al. (2014a, b) also utilized social narratives presented through an iPad application to communicate with patients about an imaging procedure. Patients with ASD were able to use the application to advance screens which presented photos and a narrated script.

A coping kit developed by Drake et al. (2012) provided a social script about going to the hospital, as well as communication cards and picture communication symbols (PCS) organized on a ring. Kennedy et al. (2016) developed a visual of Do’s and Don’ts for Communication to support healthcare providers to effectively interact with patients with ASD. Additionally, visual supports, social stories, and PCS were organized on an easily accessible ring to help visually communicate with patients. Similarly, Scarpinato et al. (2010) and McGonigle et al. (2014b) recommended the use of American Sign Language (ASL), and augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices, such PCS and Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) for patients with ASD. Vaz (2013) utilized Widgit software to provide visuals on a timeline or key ring to represent common medical examinations, clinical procedures and treatments.

In addition to visuals and social stories, Vaz (2010) recommended the use of modeling, imitation, use objects to role-play/model procedures, pictures or photographs, and succinct explanations to help patients understand and anticipate procedural expectations. Zanotti (2018) also recommended keeping communication direct and clear. Samet and Luterman (2019) developed See-Hear-Feel-Speak, a four-step system. With Speak, the authors advised healthcare providers to utilize simple language to specifically communicate each step of a procedure (e.g., physical exam, injection) before and while conducting it.

Sensory Needs and Environmental Modifications

Samet and Luterman’s (2019) four-step system addressed the potential need to remove excessive visual stimuli by dimming lights, eliminate the flickering or blinking of lights, and dull or eliminate florescent lighting. With Hear, the authors recommend removing excessive stimuli by dampening alarms and noises in the surrounding equipment and environment. The authors also recommended healthcare providers offer materials that may help to calm the patient and remove particular textures that may be abrasive to the patient. Within the coping kit developed by Drake et al. (2012), patients had access to thera-tubing and ring to play with or chew, a soft ball, light up spinning fan, and vibrating toy to address sensory preferences.

Addressing sensory needs may include specific environmental considerations. In addition to addressing sounds, smells, textures, noises, Scarpinato et al. (2010) recommended that the number of staff who come in contact with the patient be minimized. Similarly, Zanotti (2018) recommended that a limited number of healthcare providers be involved in the care plan and that a box of sensory toys could be provided to address sensory needs. McGonigle et al. (2014b) also recommended environmental adaptations to address stimulation, lighting, and the number of healthcare providers providing care. In regards to environmental modifications, Gabriels et al. (2012) applied the TEACCH model within the hospital setting to provide a more structured, predictable, and visually accommodating hospital environment. Using TEACCH, the authors created defined areas and utilized visual cues to explicitly define expectations.

Behavioral Interventions

Souders et al. (2002) applied effective behavioral strategies to facilitate medical encounters with patients with ASD. These strategies, along with recommendations for when they could be applied during specific medical procedures, included imitation, role-modeling, shaping of behaviors, reinforcement, providing choices, and use of visuals. Gabriels et al. (2012) also recommended the use role playing, modeling, error correction techniques, and social praise to teach and encourage the use of appropriate behaviors. Through the recommendations of families, Vaz (2010) also recommended the use of rewards to increase engagement in preferred behaviors.

To address the connection between communication and maladaptive behaviors, McGuire et al. (2016) aimed to address I/PB by understanding functional communication needs and the function maladaptive behaviors aims to serve. The authors recommended that behaviors be continually monitored based on duration or frequency. Lastly, McGonigle et al. (2014b) stated that both applied behavior analysis and cognitive behavior therapy, which employ reinforcement of preferred behaviors have been identified as evidence-based and best practice for individuals with ASD.

Other Best Practices

Distraction through the discussion of preferred topics (Sounders et al. 2002; Vaz, 2010), and counting, reciting the alphabet, singing, and toys was suggested to help facilitate medical encounters (Drake et al. 2012; Sounders et al. 2002). Other recommended strategies included allowing patients with ASD to explore devices (i.e., see, touch), and being aware of routines and providing warnings for transitions and sequences of procedural steps (Scarpinato et al. 2010; Vaz2010).

Education, Training, and Resources for Healthcare Providers

The above intervention strategies and evidence-based practices indirectly educated healthcare providers on how to effectively interact and address the unique needs of this population of patients. However, five articles also provided direct training to nursing staff and other healthcare providers through online avenues and/or in-person trainings.

In addition to instruments and resources to support patients with ASD, Kennedy and Binns (2014) and Kennedy et al. (2016) provided healthcare providers with training. Kennedy and Binns developed a monthly training program which provided burn service staff members information on ASD, and interventions and supports to communicate with patients and families to prepare the patient for burn treatments. Overall, these trainings aimed to increase partnerships with families to improve upon the hospital experience. Kennedy et al. (2016) provided training through the help of educational, interactive, and visual sessions delivered by Positive About Autism, a company providing training on autism.

In order to address fear and intimidation experienced by healthcare providers, Johnson et al. (2012) developed a one-hour online training and a one-hour instructor-led training. The online lessons included a review of developmental disabilities with a particular emphasis on ASD, strategies to prepare for a patient with ASD, and strategies for communication and playing with the patient. The strategies shared in the online component were applicable to patients with ASD across the age range. The in-person trainings, which were co-taught by security personnel, child life specialists, and nurses, involved healthcare providers viewing six videos depicting common scenarios and the role modeled strategies to prevent or respond to challenging behaviors. Discussions and opportunities to practice the demonstrated methods followed these videos. Demonstrations involved opportunities to apply the strategies to case study situations, and strategies outlined on teaching sheets were presented to participating healthcare providers. Using the coping kit developed by Drake et al. (2012), participants learned about the kit of resources to support communication, sensory needs, and distract the patient. Participants also learned about how environmental modifications could be made to address the sensory needs of patients and potentially avoid challenging behaviors.

Similarly, Lucarelli et al. (2018) developed online learning modules and in-person training, which was customized to the needs of eight participating departments. The developed modules focused on symptoms, epidemiology, etiology of ASD, as well as how medical settings may present a challenge for this population, and provided a foundation for the following in-person training. Mirroring the training developed by Johnson et al. (2012), Lucarelli et al. utilized a multidisciplinary team, including medical providers, a psychologist, and child life specialist, as well as an Autism Spectrum Center and our ASD Parent Advisory Committee. These trainings provided healthcare providers with strategies to prevent and address maladaptive behaviors such as noncompliance, hyperactivity, sensory defensiveness, and self-injury. Strategies also included partnering with families. The trainings included videos depicting behaviors, case discussions, direct instruction, problem solving discussions, and interviews of families sharing their unique experiences.

Following a needs assessment, McGonigle et al. (2014a) developed didactic and training materials for emergency department healthcare providers. A training manual and accompanying DVD of case examples and experiences shared by individuals with ASD and their families were developed to address epidemiology and defining characteristics of the population, misconceptions about individuals with ASD, comorbidities, and strategies to aid in obtaining a medical history, conducting a physical examination, collect laboratory and radiographic testing, and begin treatment procedures. Training also provided strategies for triage procedures, environmental modifications, and use of sedation.

Healthcare Provider Champions

Appointing a healthcare provider or several to assist in collecting information from families, developing a patient-centered care plan, implementing the developed plan, and also facilitate transitions to other healthcare providers was identified in two studies. As part of their intervention design, Kennedy and Binns (2014) included two champions to ensure necessary resources were available, coordinated the care plan, and partner with other care staff. Pratt et al. (2012) identified a staff member with experience working with individuals with ASD in order to gather checklist information and work with families at admission. This staff member was also responsible for providing the ascertained information to necessary providers in the ward and also identify another staff member to oversee the care plan.

Discussion

The scoping review presents a broad overview of the efforts made by healthcare providers and others in both the medical and autism field to ensure ethical medical care for individuals with ASD. Specifically, the review aimed to examine the implemented tools and/or interventions and recommendations that attempt to facilitate medical encounters and decrease anxiety and stress experienced by individuals with ASD and their families. The NPDC (Wong et al. 2015) and NAC (2015) have identified evidence-based practices for individuals with ASD, and the review aimed to also identify whether interventions implemented in medical settings aligned to these practice recommendations. The scoping review also aimed to examine whether efforts integrated education, training, and resources for healthcare providers, as well as limitation and challenges to implementing these interventions and the implications for future practice and research.

In total, 23 articles were identified as meeting inclusion criteria for the scoping review. The predominant theme amongst the studies included the use of survey instruments to effectively collect information from families in order to develop an individualized care plan for the patient with ASD. The studies also utilized evidence-based practices and resources based on elicited information. These strategies and materials included visual and communication supports, response to sensory needs, environmental modifications, application of behavioral interventions, and other strategies such as distraction. Training healthcare providers on ASD, the etiology, and core characteristics of the disability, as well as strategies to best communicate and be responsive to the individual needs of the population were apparent in the included literature.

The studies align with past literature documenting the challenges experienced by individuals with ASD, families of those patients, and healthcare providers. The findings substantiate and expand upon the present literature by utilizing past literature on the documented obstacles to patient-centered care for individuals with ASD and their families to develop instruments and interventions. Therefore, beyond presenting these challenges and experiences, the scoping review presents the efforts to address and resolve the concerns of patients with ASD and their families, as well as healthcare providers. Several of the studies included in the review also gathered additional information and collaborated with patients, other healthcare providers within and outside their departments, as well as community partners and autism advocacy groups in developing interventions and resources (e.g., Broder-Fingert et al. 2016; Carter et al. 2017; Johnson et al. 2012; Jolly 2015; Lucarelli et al. 2018).

The scoping review presents the initial steps to ensuring that individuals with ASD are appropriately treated in medical settings. These efforts are commendable and draw upon the current understanding of the disability. There are several implications for practice that should be applied across all medical environments, and there are notable gaps in the literature that necessitate additional discussion, development, and research to continue to inform the development of supports.

Implications for Practitioners and Future Research

The fourth and fifth aim of the scoping review involve the identification of limitations and challenges associated with implementing these supports, and the work moving forward that can continue to or better support families and patients with ASD. The findings of this scoping review suggest a number of implications for future intervention, development and research. Based on the complexity of the disability and as evidenced in the literature, the interventions employed should be nuanced and multifaceted, and both directly and indirectly increase the knowledge and strategic practices of healthcare providers. Multidisciplinary collaboration in developing the interventions is another strength and consideration for practitioners. Such partnerships may also be further expanded to include the educators and related service providers of patients with ASD. As discussed by McGonigle et al. (2014b), practitioners should ensure increased proactivity and application of effective practices by accessing information from educators and information available on an individualized education plan or behavior intervention plan. Such efforts would connect both the educational and medical setting, and provide continuity for the individuals with ASD.

Methodological Rigor

Of the 23 articles selected for inclusion, fourteen of the articles attempted to collect information on the interventions and supports recommended or developed. The decision to include opinion or practice guideline papers provides implications for future research. Limited in their methodology, future researchers may consider collecting both quantifiable and subjective data to substantiate and test the effectiveness of the interventions implemented for patients with ASD. As mentioned, with the multiple components involved in many of the efforts, researchers should examine the impact of individual or packaged components, and identify gaps that need to be addressed with other evidence-based practices. Furthermore, feedback was predominately collected from families and healthcare providers. Researchers should consider whether the direct voices of individuals with ASD are included in both the development of supports and the testing of whether they are indeed effective in facilitating medical encounters.

Efficiency of Care Delivery

Future research should further examine whether the interventions put into place improve upon the workflow efficiency and delivery of medical care. Broder-Fingert et al. (2016) examined length of stay, however, researchers should more closely examine whether length of stay for patients with ASD is decreased and whether the conducting of medical procedures and tests are not deferred. As noted, it would be important to identify whether the interventions, which aim to prevent and reduce maladaptive behaviors, lessen or eliminate the use of restraints, seclusion, pharmacological medications, and increase patient safety across all medical settings. Future research should also examine whether medical costs for families are reduced with these supports in place, as well as whether disparities in medical care are addressed.

In order to ensure there is a broad, transformative impact for patients with ASD, it is important to consider and study whether healthcare providers are implementing evidence-based practices with fidelity and with consistency, and whether providing training increases these two factors. Additionally, practitioners should consider the ease of use to ensure maintained application of resources and interventions. These considerations may include the accessibility and organization of resources (e.g., EMR, location and availability of materials). Beyond accessing the information and materials, it would be necessary to consider whether healthcare providers are able to effectively identify the appropriate resources and strategies, and how to accurately use them.

Continuity of Care

Application across all settings is another essential component, and thus adoption by other medical departments and medical settings is critical. As suggested by Carter et al. (2017) and Jolly (2015), the transfer of information gathered and best practices to interact with the patient with ASD is necessary to ensure consistent practices across medical staff, departments, and other medical settings. Additionally, the responsibilities of eliciting, reviewing, and utilizing information collected on the patient, as well as applying the individualized care plan should not solely fall upon nursing staff. This was evidenced by Broder-Fingert et al. (2016), Bultas et al. (2016), Jolly (2015), and McGonigle et al. (2014a). Furthermore, Broder-Fingert et al. discussed that families may not be aware of the availability of supports for their child with ASD. Advertising may therefore be essential in ensuring that all appropriate stakeholders are aware of resources available to facilitate medical encounters.

Future researchers and practitioners should also consider whether interventions developed could be generalized across medical environments, or could be customized to be responsive to the specific obstacles and needs of different medical settings. The sustainability of the intervention materials is another factor. Researchers and practitioners should examine the cost of implementation and cost of consumables. Lastly, consistent application of these practices must again take into account time. With healthcare providers undergoing training to ensure medical practices are empirically based and align with safety concerns and other regulations, it would be important to examine the ideal method to delivering training that is effective and cost- and time-efficient.

In addition to generalization across all medical settings, researchers and practitioners should examine whether the interventions developed address individuals across the spectrum. As Souders et al. (2002) examined, certain strategies were found to be more effective for individuals with high-functioning than mild to moderate and severe ASD and intellectual disabilities. If such efforts do not fully address the spectrum, additional consideration is needed to ensure the inclusion of all individuals with ASD. The articles included in the review also predominately focused on children and adolescents with ASD. Practitioners and researchers should examine whether such interventions are applicable to adults with ASD.

Empowerment of Families

Broder-Fingert et al. (2016) and Bultas et al. (2016), as well as other articles, aimed to empower and engage families to provide valuable information about their child with ASD and ensure best practices were being used to facilitate the medical encounter. Further research should be done to see if this empowerment spans across the medical setting, with a particular focus on families from lower socioeconomic statuses or families with limited access to evidence-based interventions and resources. Researchers should examine whether the application and observation of interventions being used in the medical setting leads families to further advocate on behalf of their child and seek out interventions to be implemented in the school, home, and community setting.

Limitations and Challenges to Implementing These Interventions

Without individualized care plans for patients with ASD, the healthcare system will experience systemic strain. As discussed in the introduction, patients with ASD are more likely than typically developing children to have multiple medical comorbidities and thus require more frequent encounters with the healthcare system for longitudinal care. While several medical practices and hospitals have made individual efforts to implement autism-friendly practices, the healthcare system is ill-equipped to accommodate the sensory and behavioral needs of this vulnerable population of patients. The absence of these accommodations is a barrier to care for patients with ASD who become fearful of medical encounters, and as a result, do not seek preventative management of their medical problems until they become more severe and therefore, more costly to manage. It is important to acknowledge that individualized care plans and the suggested tools and/or interventions do require an initial investment of time and resources. Responding to the individual needs of each patient with ASD through the collection and reviewing of data collected from families and acting upon the suggestions through the utilization of evidence-based practices and resources may further prolong the medical visits. The constraint of time may be further impeded with training and continued trainings. A dedicated champion to coordinate a care plan and accompanying resources, and partnership with other care staff may strain the limited number of healthcare providers available in the setting. It is also notable that funding and building or environmental obstacles may further hinder the availability of resources, their maintenance, and the recommended changes to the physical medical setting. However, many of the interventions that the authors have reviewed in this article were relatively inexpensive and well-received by both patients and medical staff.

Limitations of the Scoping Review

This review is limited in scope to general medical care, with a particular emphasis on emergency or acute care settings and an exclusion of dentistry and preoperative care. The vast majority of studies included in this review were conducted in the United States, and it is important to recognize that medical care across the world differs. The studies focused primarily on medical encounters of school-aged children with ASD. Understanding that adults with ASD experience unique challenges related to medical encounters, it would be important to further explore studies focused on patients older than 21 years of age. Lastly, a scoping review methodology does not incorporate a detailed analysis of methodological rigor of studies included in the synthesis. Therefore, a future systematic review or metanalysis of the literature may be appropriate to provide greater implications for future research efforts and refinement of supports provided for this population.

Conclusion

The healthcare environment may be highly rigid and may not easily adapt to the unique needs of individuals with disabilities, especially those with ASD. It is necessary to continually examine whether such medical environments and those involved can be made more flexible and responsive to the individual needs of patients. This scoping review allows for a robust understanding of how medical professionals and those working closely with individuals with ASD have made impactful adjustments to hospital settings to be more conducive and to facilitate interactions with this growing and heterogenous population. However, more work must be done to ensure that these supports are available equitably across all medical settings and that the limitation and challenges identified are ameliorated. Enhancing the delivery of healthcare practices for individuals with ASD may have a universal impact, and could be beneficial for all patients with disabilities, or more broadly all patients may benefit for such interventions and greater partnerships with families to develop individualized medical care plans.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Balakas, K., Gallaher, C. S., & Tilley, C. (2015). Optimizing perioperative care for children and adolescents with challenging behaviors. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 40(3), 153–159.

Boyle, C. A., Boulet, S., Schieve, L. A., Cohen, R. A., Blumberg, S. J., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., et al. (2011). Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics, 127(6), 1034–1042.

*Broder-Fingert, S., Shui, A., Ferrone, C., Dorthea, I., Cheng, E., Giauque, A., et al. (2016). A pilot study of autism-specific care plans during hospital admission. Pediatrics, 137(S2), S196–S204.

Bultas, M. W. (2012). The health care experiences of the preschool child with autism. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27, 460–470.

*Bultas, M. W., McMillin, S. E., & Zand, D. H. (2016). Reducing barriers to care in the office-based health care setting for children with autism. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30(1), 5–14.

*Carter, J., Broder-Fingert, S., Neumeyer, A., Giauque, A., Kao, A., & Iyasere, C. (2017). Brief report: Meeting the needs of medically hospitalized adults with autism: A provider and patient toolkit. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 1510–1529.

*Chebuhar, A., McCarthy, A. M., Bosch, J., & Baker, S. (2013). Using picture schedules in medical settings for patients with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28(2), 125–134.

Chiri, G., & Warfield, M. E. (2012). Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 1081–1091.

Croen, L. A., Najjar, D. V., Ray, T., Lotspeich, L., & Bernal, P. (2006). A comparison of health care utilization and costs of children with and without autism spectrum disorders in a large group-model health plan. Pediatrics, 118, e1203–e1211.

Davis, I. T. E., Moree, B. N., Dempsey, T., Reuther, E. T., Fodstad, J. C., Hess, J. A., et al. (2011). The relationship between autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: The moderating effect of communication. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 324–329.

*Drake, J., Johnson, N., Stoneck, A. V., Martinez, D. M., & Massey, M. (2012). Evaluation of a coping kit for children with challenging behaviors in a pediatric hospital. Pediatric Nursing, 38(4), 215–221.

*Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Beresford, C., Morrow, M., Mesibov, G., & Wamboldt, M. (2012). Improving psychiatric hospital care for pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Autism Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/685053

Giarelli, E., Nocera, R., Turchi, R., Hardie, T. L., Pagano, R., & Yuan, C. (2014). Sensory stimuli as obstacles to emergency care for children with autism spectrum disorder. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 36(2), 145–163.

Gurney, J. G., McPheeters, M. L., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Parental report of health conditions and health care use among children with and without autism: National Survey of Children’s Health. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(8), 825–830.

Iannuzzi, D., Cheng, E., Broder-Fingert, S., & Bauman, M. (2015). Brief report: Emergency department utilization by individuals with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 1096–1102.

Isong, I. A., Hanson, E., Ware, J., Nelson, L. P., Rao, S. R., Holifield, C., & Iannuzzi, D. (2014). Addressing dental fear in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled pilot study using electronic screen media. Clinical Pediatrics, 53(3), 230–237.

Johnson, H. L., & DeLeon, P. H. (2016). Accessing care for children with special health care needs. Practice Innovations, 1(2), 105–116.

Johnson, N., Bekhet, A., Robinson, K., & Rodriguez, D. (2014). Attributed meanings and strategies to prevent challenging behaviors of hospitalized children with autism: Two perspectives. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 28(5), 386–393.

*Johnson, N., Bree, O., Lalley, E. E., Rettler, K., Grande, P., Gani, M. O., & Ahamed, S. I. (2014). Effect of a social script iPad application for children with autism going to imaging. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(6), 651–659.

*Johnson, N., Lashley, J., Stonek, A., & Bonjour, A. (2012). Children with developmental disabilities at a pediatric hospital: Staff education to prevent and manage challenging behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27, 742–749.

Johnson, N. L., & Rodriguez, D. (2013). Children with autism spectrum disorder at a pediatric hospital: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatric Nursing, 39(3), 131–141.

*Jolly, A. A. (2015). Handle with care: Top ten tips a nurse should know before caring for a hospitalized child with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Nursing, 41(1), 11–16.

Kamat, P. P., Bryan, L. N., McCracken, C. E., Simon, H. K., Berkenbosch, J. W., & Grunwell, J. R. (2018). Procedural sedation in children with autism spectrum disorders: A survey of current practice patterns of the society for pediatric sedation members. Pediatric Anesthesia, 28(6), 552–557.

Karpur, A., Lello, A., Frazier, T., Dixon, P. J., & Shih, A. J. (2019). Health disparities among children with autism spectrum disorders: Analysis of the National Survey of Children’s Health 2016. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(4), 1652–1664.

*Kennedy, R., & Binns, F. (2014). Communicating and managing children and young people with autism and extensive burn injury. Wounds UK, 10(3), 1–5.

*Kennedy, R., Binns, F., Brammer, A., Grant, J., Bowen, J., & Morgan, R. (2016). Continuous service quality improvement and change management for children and young people with autism and their families: A model for change. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 39(3), 192–214.

Kiln, A., McPartland, J., & Volkmar, F. (2005). Asperger’s syndrome. In F. Volkmar, R. Paul, A. Kiln, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (Vol. 1, pp. 88–125). New York: Wiley.

Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Blumberg, S. J., Singh, G. K., Perrin, J. M., & van Dyck, P. C. (2008). A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics, 122, e1149–e1158.

Kopecky, K., Broder-Fingert, S., Iannuzzi, D., & Connors, S. (2013). The needs of hospitalized patients with autism spectrum disorders: A parent survey. Clinical Pediatrics, 52(7), 652–660.

Koski, S., Gabriels, R. L., & Beresford, C. (2016). Interventions for paediatric surgery patients with comorbid autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 101(12), 1090–1094.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. Lancet, 383, 896–910.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9.

Liptak, G. S., Stuart, T., & Auinger, P. (2006). Health care utilization and expenditures for children with autism: Data from U.S. national samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 871–879.

*Lucarelli, J., Welchons, L., Sideridis, G., Sullivan, N. R., Chan, E., & Weissman, L. (2018). Development and evaluation of an educational initiative to improve hospital personnel preparedness to care for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(5), 358–364.

Lui, G., Pearl, A. M., Kong, L., Leslie, D. L., & Murray, M. J. (2017). A profile on emergency department utilization in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(2), 347–358.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., et al. (2020). Prevalence of Autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States. MMWR Surveill Summ, 69(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

Mayes, S. D., Calhoun, S. L., Aggarwal, R., Baker, C., Mathapati, S., Anderson, R., & Petersen, C. (2012). Explosive, oppositional, and aggressive behavior in children with autism compared to other clinical disorders and typical children. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 1–10.

*McGonigle, J., Migyanka, J., Glor-Scheib, S., Cramer, R., Fratangeli, J., Hegde, G., et al. (2014a). Development and evaluation of educational materials for pre-hospital and emergency department personnel on the care of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1252–1259.

*McGonigle, J. J., Venkat, A., Beresford, C., Campbell, T. P., & Gabriels, R. L. (2014b). Management of agitation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders in the emergency department. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(1), 83–95.

*McGuire, K., Fung, L. K., Hagopian, L., Vasa, R. A., Mahajan, R., Bernal, P., et al. (2016). Irritability and problem behavior in autism spectrum disorder: A practice pathway for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics, 137(Suppl 2), S136–S148.

Minnes, P., & Steiner, K. (2009). Parent views on enhancing the qual- ity of health care for their children with fragile X syndrome, autism or Down syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(2), 250–256.

Myers, S. M., & Johnson, C. P. (2007). Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120, 1162–1182.

National Autism Center. (2015). Findings and conclusions: National standards project, phase 2: Addressing the need for evidence-based practice guidelines for autism spectrum disorder. Randolph, MA: National Autism Center.

Nicholas, D. B., Zwaigenbaum, L., Muskat, B., Craig, W. R., Newton, A. S., Cohen-Silver, J., et al. (2016). Toward practice advancement in emergency care for children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 137, S205–S211.

*Pratt, K., Baird, G., & Gringras, P. (2012). Ensuring successful admission to hospital for young people with learning difficulties, autism and challenging behaviour: A continuous quality improvement and change management programme. Child Care, Health, and Development, 38(6), 789–797.

Rhoades, R. A., Scarpa, A., & Salley, B. (2007). The importance of physician knowledge of autism spectrum disorder: Results of a parent survey. BMC Pediatrics., 7, 37.

*Samet, D., & Luterman, S. (2019). See-Hear-Feel-Speak: A protocol for improving outcomes in emergency department interactions with patients with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Emergency Care, 35(2), 157–159.

*Scarpinato, N., Bradley, J., Kurbjun, K., Bateman, X., Holtzer, B., & Ely, B. (2010). Caring for the child with an autism spectrum disorder in the acute care setting. Journal for Specialists Pediatric Nursing, 15(3), 244–254.

*Souders, M., Freeman, K., DePaul, D., & Levy, S. (2002). Caring for children and adolescents with autism who require challenging procedures. Pediatric Nursing, 28(6), 555–562.

Suarez, M. (2012). Sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorders and impact on functioning. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 59(1), 203–214.

*Vaz, I. (2010). Improving the management of children with learning disability and autism spectrum disorder when they attend hospital. Child: Care, Health & Development, 36(6), 753–755.

*Vaz, I. (2013). Visual symbols in healthcare settings for children with learning disabilities and autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Nursing, 22(3), 156–159.

*Venkat, A., Migyanka, J., Cramer, R., & McGonigle, J. (2016). An instrument to prepare for acute care of the individual with autism spectrum disorder in the emergency department. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2565–2569.

WHO. (2013). Autism spectrum disorders & other developmental disorders—From raising awareness to building capacity. Geneva: Meeting Report of World Health Organization.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucha-rczyk, S., et al. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951–1966.

Wu, C. M., Kung, P. T., Li, C. I., & Tsai, W. C. (2015). The difference in medical utilization and associated factors between children and adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 78–86.

*Zanotti, J. M. (2018). Handle with care: Caring for children with autism spectrum disorder in the ED. Nursing, 48(2), 50–55.

Zuckerman, K. E., Lindly, O. J., Bethell, C. D., & Kuhlthau, K. (2014). Family impacts among children with autism spectrum disorder: The role of health care quality. Academic Pediatrics, 14(4), 398–407.

Zwaigenbaum, L., Nicholas, D., Muskat, B., Kilmer, C., Newton, A., Craig, W., & Sharon, R. (2016). Perspectives of health care providers regarding emergency department care of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1725–1736.

Funding

This study was not funded by any grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK conceived of the study; participated in its design and coordination; participated in collection, interpretation and analysis of data; and drafted the manuscript. TK participated in the design and coordination, interpretation and analysis of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kouo, J.L., Kouo, T.S. A Scoping Review of Targeted Interventions and Training to Facilitate Medical Encounters for School-Aged Patients with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 51, 2829–2851 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04716-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04716-9