Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine how behavioral manifestations of trauma due to abuse are expressed in youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) compared outcomes between patients with a caregiver reported history of abuse and those without. Findings indicate that patients with ASD and reported abuse (i.e. physical, sexual, and/or emotional) have more intrusive thoughts, distressing memories, loss of interest, irritability, and lethargy than those without reported maltreatment. Those with clinical diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) had more severe and externalized symptoms than those with reported abuse not diagnosed with PTSD. Results emphasize the need for trauma screening measures to guide evidence-based treatments for children with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The high prevalence rates of maltreatment in children with disabilities, specifically autism spectrum disorder (ASD), points to the need to identify and treat symptoms of trauma in this highly vulnerable population. An electronic merger of hospital, central registry, foster care, and law enforcement records in Nebraska found that children with disabilities (including developmental, physical and medical disabilities) were twice as likely to be maltreated compared to children without disabilities (Sullivan and Knutson 2000). Likewise, a national research hospital found that when compared to children without disabilities, children with disabilities were 1.8 times more likely to experience neglect, 1.6 times more likely to experience physical abuse, and 2.2 times more likely to experience sexual abuse (Sullivan and Cork 1996). Children with ASD may be at particular risk, as Hall-Lande et al. (2015) surveyed 35 Child Protective Service (CPS) agencies in Minnesota and found that children with ASD had three to four times greater risk for maltreatment compared to other CPS-involved children. Despite these high prevalence rates for maltreatment in children with disabilities, there are currently no known specific evidence-based screening or assessment tools or treatments for children with ASD and a history of maltreatment. The initial step in developing such tools and treatments is to better understand how trauma symptoms are expressed in children and adolescents with ASD.

There are many barriers related to identifying trauma symptoms in the ASD population. First, there is a high degree of overlap between the ASD and PTSD diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association 2013), making differential diagnosis difficult in some cases (Table 1). For example, children with PTSD, regardless of whether or not they have a diagnosis of ASD, may engage in repetitive behaviors, be hypersensitive to sensory experiences, and struggle with social interactions. They may also experience sleep difficulties, engage in isolative behaviors, show approach avoidance behaviors, and display mood lability (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Furthermore, children who have experienced severe early global deprivation in orphanages have been observed to develop symptoms labeled, “quasi-autism” (Rutter et al. 1999). Key features of “quasi-autism” include having sensory preoccupations and circumscribed interests as well as difficulties with forming selective friendships, engaging in social reciprocity, accompanied by struggles using direct eye-gaze and communicative gestures during social exchanges, which bears similarities to the symptomology of reactive attachment disorder, a diagnosis commonly connected with early maltreatment (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Similar findings were reported by a recent study of children with ASD who experienced abuse/neglect in early childhood in the United Kingdom. In this study, 11% of participants were diagnosed with ASD, 18.5% were found to have sub-threshold ASD traits and 9% of respondents screened as false positives for ASD (Green et al. 2016). This is yet another example of differential diagnostic complexities between ASD and PTSD. Additionally, cumulative traumatic life experiences other than abuse (e.g., car accidents, loss of a loved one, parental divorce) may be related to symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with ASD further complicating differential diagnosis and detection of PTSD for mental health professionals (Taylor and Gotham 2016). Thus, the diagnosis of ASD may not only make children more susceptible to maltreatment, but the experience of maltreatment may also lead to the development of ASD-like symptoms making accurate diagnosis all the more difficult (Kerns et al. 2015).

Given the large symptom overlap between ASD and PTSD, it may be difficult to identify PTSD in children with ASD due to the problem of diagnostic overshadowing, defined as a tendency for professionals to over-attribute a patient’s symptoms to a particular condition while overlooking a comorbid condition (Reiss et al. 1982). Diagnostic overshadowing can ultimately lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. Professionals may not consider PTSD symptoms because they may attribute trauma-related behaviors to ASD symptoms. This situation is further complicated by the fact that children with ASD tend to be poor self-reporters, particularly when it comes to reporting their emotional experiences (Mazefsky et al. 2011; Shalom et al. 2006). If professionals are not aware of a child’s exposure to a traumatic event due to lack of self or parent report, they may be less likely to consider a co-existing diagnosis of PTSD. Due to the many barriers to identifying trauma-related symptoms in children with ASD, it is important to examine how trauma due to abuse is expressed in children and adolescents with ASD.

Several theories currently exist in the literature regarding how individuals with ASD may react to a potentially traumatic event. One theory proposes that individuals with ASD are more susceptible to the expression of trauma symptoms compared to neurotypical individuals when exposed to a potentially traumatic event. Proponents of this theory point to difficulties with information processing, language comprehension, emotion-regulation and the experience of social isolation as factors that may contribute to greater expression of trauma symptoms in individuals with ASD (Kerns et al. 2015; Mansell et al. 1998). A second theory hypothesizes that individuals with ASD who are exposed to a potentially traumatic event are less susceptible to the development of trauma symptoms. This theory argues that the inward and narrow focus (i.e. differences in perception and social awareness and difficulties describing inner psychic states) common in this population may limit their ability to accurately interpret or perceive an event as traumatic (Kerns et al. 2015; Mansell et al. 1998; Mehtar and Mukaddes 2011). A third school of thought posits that individuals with ASD react to traumatic events in the same way as neurotypical individuals (Cook et al. 1993; King and Desaulnier 2011; Mansell et al. 1998). Unfortunately, there has been limited research to test these theories.

The objective of this study was to examine how behavioral manifestations of caregiver-reported abuse may be expressed in children and adolescents with a research-reliable diagnosis of ASD admitted to six inpatient specialty psychiatric hospital units in the United States. Although many events may be experienced as traumatic for youth with ASD, this study focuses on the caregiver report of participants who had experienced physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse. Data was collected as part of the autism inpatient collection (AIC) study (Siegel et al. 2015). Analyses focused on those with and without a caregiver-reported history of abuse and those with and without a discharge diagnosis of PTSD made by the participant’s clinical treatment team. Specific aims were to: (1) identify the prevalence of caregiver-reported abuse and participant symptoms consistent with a PTSD diagnosis in the AIC sample as a whole, (2) identify the type of maltreatment (i.e., physical, sexual, or emotional abuse), (3) examine the types and degree of PTSD symptoms present in the sub-sample of the AIC study population identified by caregivers as having been exposed to abuse versus those whose caregivers did not report exposure to abuse and (4) identify differences between participants with and those without caregiver-reported abuse in adaptive functioning, severity of core ASD symptoms and behavioral symptom severity. As there has been little research done on trauma in the ASD population, these aims were exploratory.

Methods

Sample

Participants were 350 children and adolescents aged 4–21 years recruited from six specialty psychiatric hospital units as part of the AIC (Siegel et al. 2015). All 350 participants in the AIC sample received a score of 12 or higher on the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), a screener for ASD (Rutter et al. 2003) or were referred by the clinical team due to high suspicion of ASD. All participants had at least one parent or caregiver who spoke proficient English. All participants were administered the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2), a structured, interactive assessment of social communication, social reciprocity, and stereotyped/repetitive behaviors to confirm ASD diagnosis by a research-reliable examiner (Lord et al. 2012). Of the 350 participants, 79% were male and 21% were female. The average age of the sample was 12.9 years (SD = 3.3), 79% of the sample was Caucasian, and the average non-verbal IQ (NVIQ) as measured by the Leiter International Performance Scale, Third Edition (Leiter-3) was 76.4 (SD = 29.0) with 42% of the sample falling below the IQ cutoff (70) for Intellectual Disability (Roid et al. 2013). 127 (36%) participants had very low verbal ability as indicated by use of ADOS-2, Module One. Demographics are summarized in Table 2.

Measures

The ADOS-2 (Lord et al. 2012) comparison score, was used as a measure of current ASD core symptom severity to determine if there was a difference between severity of ASD symptoms in children who had experienced caregiver reported abuse and those who had not. The ADOS-2 was also used to determine participants’ verbal ability based on whether or not participants were administered Module One, as Module One is given to individuals who do not consistently engage in phrase speech. The Leiter-3 (Roid et al. 2013) was used to assess between group differences of NVIQ and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS-II) (Sparrow et al. 2005) was used to assess between group differences in adaptive functioning. The scales from the aberrant behavior checklist (ABC-C) (Aman et al. 1985) provided an overall picture of behavioral symptomology present in participants who were exposed to maltreatment compared to those who were not. Each of the ABC-C subscales (irritability, inappropriate speech, lethargy, stereotypy and hyperactivity) are measured on a scale from zero to three, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms in children. Specific items from the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory, Fifth Edition (CASI-5) (Gadow and Sprafkin 2013) were used to determine PTSD symptomology. The CASI-5 is a 142-item parent-report measure rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (very often), which was designed to help clinicians with making DSM-5 diagnoses. Since there are a limited number of PTSD specific items on the CASI-5, additional items were chosen by the two lead authors based directly on DSM-5 criteria for PTSD to create a more complete picture of PTSD symptoms (Table 3). If more than one item represented a DSM-5 criterion, the item ratings were averaged.

Finally, caregiver report of the participant’s abuse history was collected via the Demographic and Medical Intake Form created by AIC researchers. This item asked caregivers, “Does the child have a history of abuse?” with checkbox response options including: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse or none. Participants’ PTSD diagnoses was derived from the consensus diagnosis of each participant’s inpatient treatment team at discharge.

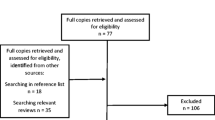

Procedure

Data on demographics, experience of abuse, diagnosis, cognitive functioning, adaptive functioning, and psychiatric symptomology was collected from the overall AIC sample; methods of the AIC have been published previously (Siegel et al. 2015). Briefly, within 7 days of admission caregivers completed the ABC-C, CASI-5, and Intake Demographic and Medical Form. During hospitalization, participants were administered the Leiter-3 and the ADOS-2 by an examiner who had achieved research reliability with the AIC certified ADOS-2 trainer. Caregivers also completed the Vineland-II. At discharge consensus co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses were assigned by the attending child psychiatrist and a unit clinician (psychologist or social worker), based on inpatient observation and history, as well as extensive experience evaluating mental health in youth with ASD. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at all participating sites and all families gave permission for their data to be used in publications related to this study.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and numbers and proportions for categorical variables. Student t test comparisons were conducted to examine differences in mean scores on all CASI-5 items and ABC subscales between patients with/without PTSD diagnosis. Satterthwaite approximation was used should equal variance assumption be violated and exact method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals for prevalence of abuse history and diagnosis of PTSD. Moreover, multiple linear regression analysis (ANCOVA) was used to compare continuous outcomes between participants with reported abuse history and those without while adjusting for age, non-verbal IQ, and verbal ability. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC) and statistical significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed tests.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Out of the total sample (n = 350), ninety-nine caregivers (28.3%, 95% CI 24–33%) reported that their child had experienced abuse. The group of participants with reported abuse ranged from 4 to 21 years of age with a mean age of 12.89 (SD = 3.34) and included 21 females (21%) and 78 males (79%), similar to the age and gender ratios of the total sample. Mean non-verbal IQ as measured by the Leiter-3 was 77.46 (SD = 25.17), ranging from 30 to 125. Out of the 99 participants with reported abuse histories, 22 (22%) had very low verbal ability. Of those with caregiver-reported abuse, 13 (13%) reported physical abuse, 12 (12%) reported emotional abuse and 8 (8%) reported sexual abuse. One caregiver (1%) reported that their child experienced both sexual and emotional abuse; one caregiver (1%) reported that their child experienced both physical and sexual abuse, and 16 caregivers endorsed both physical and emotional abuse (16%). Out of the 99 participants whose caregivers indicated that their children had experienced abuse, only 7 (2.6%, 95% CI 1.2–4.8%) were diagnosed with PTSD at discharge by clinical team consensus (Table 2).

Between Group Differences: PTSD Symptomology

An ANCOVA was run to compare frequency of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms (Table 4) in the no abuse reported group compared to the abuse reported group on the CASI-5 while controlling for age, nonverbal IQ, and verbal ability (p < 0.05). Regarding intrusion symptoms of PTSD, the groups did not significantly differ on irritability items (p = 0.4840), but the abuse reported group had significantly greater endorsement of intrusive thoughts (p = 0.0108) and distressing memories than those whose caregivers did not endorse abuse (p < 0.001). In the persistent avoidance diagnostic category, the groups did not significantly differ (p = 0.1700). With regard to negative alterations in mood and cognition, the reported abuse group endorsed significantly more loss of interest than the no reported abuse group (p = 0.0190). There were no significant differences between the groups on experience of fear (p = 0.4301) and anger (p = 0.6914) on CASI-5 items. In the final diagnostic category, alterations in arousal/reactivity, youth with caregiver reported abuse did not have significantly more temper tantrums than those with no caregiver-reported abuse (p = 0.8210). The groups also did not differ regarding attention problems (p = 0.1007) or sleep disturbance (p = 0.5745).

Between Group Differences: General Symptomology

In order to address whether there were differences between youth with ASD with reported abuse compared to those without reported abuse with regard to general behavioral symptomology, that may not necessarily be directly connected to PTSD diagnostic criteria, an ANCOVA controlling for nonverbal-IQ, age, and verbal ability was run with the ABC-C sub-scales (p < 0.05; Table 4). On the inappropriate speech subscale, the abuse reported group did not significantly differ from the no abuse reported group (p = 0.1188). However, the abuse reported group scored significantly higher on the Irritability subscale than the no abuse reported group (p = 0.0033). Additionally, on the Lethargy subscale the abuse reported group endorsed significantly higher symptoms than the no abuse reported group (p = 0.0217). There were no significant differences between groups on the stereotypy (p = 0.1563) and hypereactivity (p = 0.2074) subscales.

Between Group Differences: Severity of Core ASD Symptoms, Adaptive Functioning, and Diagnostic Comorbidity

The abuse reported and no abuse reported groups did not significantly differ on the ADOS-2 Comparison Score, a measure of severity of ASD core symptoms (p = 0.4556). In the area of adaptive functioning, no significant differences were found between the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups on any of the subscales of the Vineland-II (p = 0.5390). Due to the possibility that differences between groups regarding co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses may impact the results of this study, a Chi-square analysis was conducted to compare the comorbid diagnoses between participants in the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups. No significant differences were found for any diagnoses or the number of comorbid diagnoses.

Between Group Differences: Trauma-Related Symptoms

Student t tests were run to examine possible differences between the PTSD group and no PTSD diagnosis group among participants with reported abuse history (Table 5). Due to the small number of participants clinically diagnosed with PTSD (7 of the 99 with reported abuse) these results should be interpreted cautiously. Differences between the groups were similar to those between the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups. However, caregivers of youth diagnosed with PTSD endorsed almost double the severity of intrusive thoughts compared to those whose youth were not diagnosed with PTSD (p = 0.0160). They also reported more distressing memories compared to the no PTSD group (p = 0.0234). Two symptoms, persistent fear and temper tantrums, were not significant when comparing the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups, but were significant when comparing participants with a PTSD diagnosis versus participants with no PTSD diagnosis. Youth diagnosed with PTSD experienced more fear according to their caregivers than youth who were not diagnosed with PTSD (p = 0.0143). Likewise, the PTSD group showed significantly more temper tantrums than the undiagnosed group (p = 0.0238).

Discussion

This study presents caregiver-report data on child abuse and associated behavioral symptoms from a large inpatient psychiatric sample of children with ASD. The study sample was divided into two groups: those whose caregivers identified them to have experienced abuse and those who did not. Demographic and reported abuse data were compared in these two groups by examining PTSD-specific symptoms, general behavioral symptomology, adaptive functioning, and ASD core symptom severity while controlling for age, non-verbal IQ, and verbal ability. Findings suggest that children with ASD and reported abuse have significantly more intrusive thoughts, distressing memories, loss of interest, irritability, and lethargy than those whose caregivers did not endorse abuse. When comparing those participants who received a clinical PTSD diagnosis compared to those with caregiver-reported abuse histories without a clinical PTSD diagnosis, participants with PTSD had more intrusive thoughts, distressing memories, persistent fear and temper tantrums.

Data from this study suggests that children with ASD experience symptomology similar to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD, but that the overlap between symptomology in children with ASD and no reported abuse versus ASD and reported abuse makes differentiation difficult. For example, CASI-5 items indicated that children with ASD and caregiver reported abuse have significantly more intrusive thoughts, distressing memories, and loss of interest in things that they used to find enjoyable than those children with ASD whose caregivers did not report abuse. These findings support prior arguments that children with ASD are susceptible to developing trauma-related symptomology (Cook et al. 1993; King and Desaulnier 2011; Mansell et al. 1998). However, a comparison to a typically-developing sample would be needed in order to understand whether they may be more or less susceptible. Further, some symptoms associated with PTSD, including fear, anger, temper tantrums, irritability, attention problems, and sleep problems did not significantly differ between the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups, likely because these are common symptoms associated with ASD (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

This study also examined general behavioral symptomology to determine if symptomology not directly related to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD was more prevalent in children with ASD and reported abuse versus ASD and no reported abuse. On the ABC-C, the abuse reported group had significantly more irritability and lethargy than the no abuse reported group. These findings go along with expected negative alterations in mood and cognition criteria for PTSD found in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013). It has also been proposed that experience of abuse may exacerbate already present ASD symptoms (Kerns et al. 2015), but our reported abuse and no reported abuse samples did not differ in ASD core symptom severity.

The similarity of the abuse reported and no abuse reported groups in ASD severity and some PTSD symptoms might have played a role in the low rate of PTSD diagnoses among those with caregiver reported abuse histories. Out of 99 children with caregiver-reported abuse, only seven were diagnosed with PTSD by expert clinical teams. The competing factors of resilience versus vulnerability are not well understood in individuals with ASD with respect to the potential formation of PTSD symptoms. It may be that a large portion of those with ASD and caregiver-reported abuse histories were resilient in the face of those experiences. It is also possible that the difference between the caregiver reported abuse histories and the clinical diagnosis proportion was due to diagnostic overshadowing and the complex emotional and behavioral presentations of children with ASD (regardless of abuse). This could have led clinicians to rely on a higher severity threshold of PTSD symptoms in order to diagnose PTSD, given that most of the PTSD symptoms were more severe for the diagnosed group versus the undiagnosed group of participants. Those diagnosed with PTSD endorsed significantly greater amounts of fearful behavior and temper tantrums. The potentially low rate of PTSD diagnosis may also reflect that not all individuals with trauma symptoms go on to meet full diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Finally, it is also possible that the rate was impacted by caregiver reported abuse not representing the actual experience of abuse or not of participants.

When comparing the participants who had reported abuse, but were not diagnosed with PTSD to those who were diagnosed with PTSD some intriguing findings emerged that shed further light on this issue. Two significant differences that did not appear when analyzing the reported abuse versus no reported abuse groups were found between the PTSD versus no PTSD groups. Those diagnosed with PTSD, endorsed significantly greater amounts of fearful behavior and temper tantrums. This suggests that these two externalized behaviors may be red flags for clinicians making PTSD diagnoses in children with ASD and that professionals may need to look more closely at other subtler or internalized trauma symptomology, such as report of distressing memories, intrusive thoughts, loss of interest, and lethargy when a child with ASD has a history of abuse.

There were several limitations of this study. Measures were not designed to collect trauma-specific information and caregiver reports of abuse and symptomology could not be further explored and clarified. Due to the communication difficulties in the ASD population and the nature of abuse and trauma, it is likely that there were participants in the no reported trauma group that had a history of abuse or that some caregivers felt uncomfortable disclosing maltreatment. Further, trauma symptoms, behavioral symptoms, and report of whether abuse occurred were all gathered by caregiver report so there is the possibility of reporter biases. The limited language abilities of some participants complicated being able to self-report abuse and some symptomology, as well. Additionally, diagnosis of PTSD was not standardized (other than meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria) so clinician biases may have impacted whether or not a diagnosis was given.

There are many opportunities for further research with regard to ASD and PTSD. Specifically, more detailed information could be gleaned from using trauma-specific measures and behavioral observations. Also, comparing symptoms based on type of abuse experienced could provide valuable information, but the number of participants in our study was too small to have adequate power for this type of analysis. Our measure only asked about physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, but future work should consider other types of trauma as well. Additionally, it may be interesting for future studies to continue to address theories in the literature regarding how individuals with ASD respond to potentially traumatic events. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to compare children with ASD who have been maltreated to neurotypical children with a history of maltreatment in order to gain greater insight into the similarities and differences between these two groups’ behavioral presentations and further aid in addressing the complexities of differential diagnosis.

References

Administration for Children and Families. (n.d.). FAM7. A Child maltreatment: Rate of substantiated maltreatment reports of children ages 0–17 by selected characteristics, 1998–2014. Retrieved July 19, 2016, from http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/fam7a.asp?popup=true.

Aman, M. G., Singh, N. N., Stewart, A. W., & Field, C. J. (1985). The aberrant behavior checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 89, 485–491.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Cook, E. H. Jr., Kieffer, J. E., Charak, D. A., & Leventhal, B. L. (1993). Autistic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1292–1294.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2013). Child & adolescent symptom inventory (CASI-5) (5th ed.). Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus.

Green, J., Leadbitter, K., Kay, C., & Sharma, K. (2016). Austism spectrum disorder in children adopted after early care breakdown. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1392–1402.

Hall-Lande, J., Hewitt, A., Mishra, S., Piescher, K., & LaLiberte, T. (2015). Involvement of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the child protection system. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 30, 237–248.

Kerns, C., Newschaffer, C. J., & Berkowitz, S. J. (2015). Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 3475–3486.

King, R., & Desaulnier, C. L. (2011). Commentary: Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Implications for individuals with autism spectrum disorders - part II. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 47–59.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, second edition (ADOS-2). Manual (part I) (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Mansell, S., Sobsey, D., & Moskal, R. (1998). Clinical findings among sexually abused children with and without developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 36, 12–22.

Mazefsky, C. A., Kao, J., & Oswald, D. P. (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174.

Mehtar, M., & Mukaddes, N. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 539–546.

Reiss, S., Levitan, G. W., & Szyszko, J. (1982). Emotional disturbance and mental retardation: Diagnostic overshadowing. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86, 567–574.

Roid, G. H., Miller, L. J., Pomplun, M., & Koch, C. (2013). Leiter International Performance Scale, third edition (Leiter-3) manual. Wood Dale: Stoelting Company.

Rutter, M., Andersen-Wood, L., Beckette, C., Bredenkamp, D., Castle, J., Groothues, C., … O’Connor, T. G. (1999). Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(4), 537–549.

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Social Communication Questionnaire. Torrance: WPS Publishing.

Shalom, D. B., Mostofsky, S. H., Hazlett, R. L., Goldberg, M. C., Landa, R. J., Faran, Y., … Hoehn-Saric, R. (2006). Normal physiological emotions but difference in expression of conscious feelings in children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 395–400.

Siegel, M., Smith, K. A., Mazefsky, C., Gabriels, R. L., Erickson, C., Kaplan, D., … for the Autism and Developmental Disorders Inpatient Research Collaborative (AIC). (2015). The autism inpatient collection: Methods and preliminary sample description. Molecular Autism, 6, 61. doi:10.1186/s13229-015-0054-8.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition (Vineland-II) manual. Circle Pines: AGS Publishing.

Sullivan, P., & Cork, P.M. (1996). Developmental Disabilities Training Project. Omaha, NE: Center for Abused Children with Disabilities, Boys Town National Research Hospital, Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services.

Sullivan, P. M., & Knutson, J. F. (2000). Maltreatment and disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 1257–1273.

Taylor, J. L. & Gotham, K. O. (2016). Cumulative life events, traumatic experiences and psychiatric symptomatology in transition-aged youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 8, 3–11.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Administration for children and families, administration on children, youth and families, children’s bureau. Child maltreatment 2012 [online]. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Acknowledgments

The ADDIRC is made up of the co-investigators: Matthew Siegel, MD (PI) (Maine Medical Center Research Institute; Tufts University), Craig Erickson, MD (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; University of Cincinnati), Robin L. Gabriels, PsyD (Children’s Hospital Colorado; University of Colorado), Desmond Kaplan, MD (Sheppard Pratt Health System), Carla Mazefsky, PhD (Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinics; University of Pittsburgh), Eric M. Morrow, MD, PhD (Bradley Hospital; Brown University), Giulia Righi, PhD (Bradley Hospital; Brown University), Susan L. Santangelo, ScD (Maine Medical Center Research Institute; Tufts University), and Logan Wink, MD (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; University of Cincinnati). Collaborating investigators and staff: Jill Benevides, BS, Carol Beresford, MD, Carrie Best, MPH, Katie Bowen, LCSW, Briar Dechant, BS, Tom Flis, BCBA, LCPC, Holly Gastgeb, PhD, Angela Geer, BS, Louis Hagopian, PhD, Benjamin Handen, PhD, BCBA-D, Adam Klever, BS, Martin Lubetsky, MD, Kristen MacKenzie, BS, Zenoa Meservy, MD, John McGonigle, PhD, Kelly McGuire, MD, Faith McNeill, BA, Ernest Pedapati, MD, Christine Peura, BA, Joseph Pierri, MD, Christie Rogers, MS, CCC-SLP, Brad Rossman, MA, Jennifer Ruberg, LISW, Cathleen Small, PhD, Kahsi A. Smith, PhD, Nicole Stuckey, MSN, RN, Barbara Tylenda, PhD, Mary Verdi, MA, Jessica Vezzoli, BS, Deanna Williams, BA, and Diane Williams, PhD, CCC-SLP. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the coordinating site advisory group: Donald L. St. Germain, MD and Girard Robinson, MD, and our scientific advisory group: Connie Kasari, PhD., Bryan King, MD, James McCracken, MD, Christopher McDougle, MD, Lawrence Scahill, MSN, PhD, Robert Schultz, PhD and Helen Tager-Flusberg, PhD, the input of the funding organizations and the families and children who participated. The autism inpatient collection (AIC) phenotypic database and biorepository is supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative and the Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation, (SFARI #296318 to MS).

Author Contributions

JB conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; ZP participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis; KAS participated in the design of the study and helped draft the manuscript; CM helped conceive and coordinate the study; RG helped conceive the study, participated in its design and helped with the interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brenner, J., Pan, Z., Mazefsky, C. et al. Behavioral Symptoms of Reported Abuse in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Inpatient Settings. J Autism Dev Disord 48, 3727–3735 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3183-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3183-4