Abstract

Stress is one candidate mechanism posited to contribute to the intergenerational risk of psychopathology. However, the ways in which parent and child stress are related across adolescence, and the role that co-occurring parent and child stress may exert regarding bidirectional risk for internalizing symptoms, are not well understood. Using repeated measures data spanning 3-years, this study investigated (1) the extent to which trajectories of parent and child stress are related during adolescence, and (2) whether co-occurring parent and child stress trajectories mediate prospective, bidirectional associations between parent depression symptoms and child internalizing symptoms (depression, physical and social anxiety). Participants included 618 parent-adolescent dyads (age 8-16; 57% girls; 89% mothers). Parent depressive symptoms and child symptoms of depression, social anxiety, and physical anxiety were assessed via self-report questionnaire at baseline and 36 months later. Parent and child stress were assessed via self-report questionnaire every three months between 3- and 33-months (11 total assessments). Latent growth curve model (LGCM) analysis found that parent and child stress trajectories were positively related across development. Prospective LGCM mediation analysis showed that higher youth stress at 3-months partially mediated prospective relations between parental depressive symptoms at baseline and youth depressive, as well as physical and social anxiety symptoms at 36-months. Parent and child stress reinforce each other across adolescence and may lead to increased risk for psychopathology. Increases in child stress represent an important factor conferring transdiagnostic risk for internalizing among children of depressed parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parental depression is a well-established risk factor for offspring psychopathology that associates transdiagnostically with youth internalizing symptoms (Goodman, 2020; Goodman et al., 2011). Interest in understanding intergenerational risk processes for psychopathology has generated a wealth of literature, and a number of mechanisms have been proposed to account for the increased risk for psychopathology among children of depressed parents (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). One such mechanism is exposure to stress. Parental depression is proposed to contribute to youth risk for internalizing symptoms through its effects on youth experience of stress. Previous research supports longitudinal relations between parental depression and youth depression through changes in children’s exposure to stressful life events (e.g., Garber & Cole, 2010; Hammen, 2005; Hammen et al., 2012). However, previous studies have largely focused on adolescent depression at the exclusion of other psychopathological outcomes, such as anxiety, which commonly co-occurs with depression (Brady & Kendall, 1992; Kessler et al., 2003) and associates with parental depression (Goodman et al., 2011). Additionally, parent-adolescent relationships are bidirectional in nature (Lougheed, 2020; Pardini, 2008), yet previous work has not rigorously examined patterns of mutually reinforcing relations between parent and child stress and the role that bidirectional stress processes may play in the coupling of parent and adolescent wellbeing. The present study therefore aimed to examine co-occurring trajectories of parent and child stress, as well as the role of these stress trajectories in mediating the prospective, bidirectional associations between parent depression and child internalizing symptoms.

Intergenerational Transmission of Depression: A Focus on Stress

Depression demonstrates robust relations with stress (Hammen, 2005), and conceptual models propose that stress plays a key role in the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology among children of depressed parents (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Gotlib et al., 2020). Stress generation models of depression suggest that depressive symptoms affect individuals’ functioning in ways that contribute to the generation of more stressors. For example, impairment associated with parental depression may contribute to increases in parent-child conflict or disturbances in parental marital and occupational functioning, with downstream implications for youth wellbeing (Hammen, 2006; Liu & Alloy, 2010). A rich literature suggests that stress functions as a key mechanism by which the intergenerational transmission of depression unfolds (e.g., Garber & Cole, 2010; Hammen et al., 2012; Hammen et al., 2004).

Research supports associations between parental depression and parental or family stress (e.g., marital conflict), as well as between parental depression and stress specific to the child (e.g., impaired social functioning) (e.g., Hammen et al., 2003; Hanington et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2011). However, few studies have evaluated how parental or family stress and child-specific stress are related to one another over time, nor how these distinct loci of stress function as mechanisms by which the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology occurs. In a prospective study of mother-child dyads assessed across a 20 year follow up period, Hammen et al. (2012) found that longitudinal relations between maternal and offspring depression were mediated by youth experience of interpersonal stress. Associations with maternal or family stress, however, were not examined. Additionally, Garber and Cole (2010) found that maternal depression predicted mothers’ own stressful life events, which in turn predicted trajectories of their adolescents’ depressive symptoms across 6 years. One cross-sectional study found that both parent and child stress explain unique variance in youth depressive outcomes among offspring of depressed parents (Hammen et al., 2004). However, longitudinal research accounting for both parent and child stress is needed to rigorously evaluate patterns of co-occurrence between parent and youth stress and to assess the specificity of these trajectories as mediators of prospective, bidirectional associations between parent and youth symptoms.

Beyond Child Depression Outcomes: Parental Depression, Stress, and Adolescent Anxiety

Meta-analyses indicate that parental depression predicts a range of internalizing outcomes in youth, including anxiety (Goodman et al., 2011). Mechanisms supporting prospective relations between parental depression and different forms of adolescent anxiety (e.g., social anxiety, physical symptoms of anxiety), however, have been understudied. Stress is one potential mechanism that may link parental depression to youth anxiety. Evidence supports prospective associations between youth stress and social anxiety (Hamilton et al., 2016) and youth stress and physiological anxious arousal (Hankin, 2008a). Relatively less work has examined associations between parent stress and youth anxiety, although meta-analytic findings indicate that family-level stress (e.g., marital conflict) predicts youth anxiety (Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006). It is unknown whether parent stress associates broadly with heterogeneous forms of youth anxiety, or whether relations between parent stress and youth anxiety display specificity to particular forms of youth anxiety (e.g., social anxiety). Given a wealth of evidence demonstrating that stress functions as a mechanism of the intergenerational transmission of depression (e.g., Garber & Cole, 2010; Hammen et al., 2012; Hammen et al., 2004), as well as a rich literature illustrating some shared mechanisms of risk between youth depression and social anxiety and between youth depression and panic disorder (Cummings et al., 2014), additional work is needed to examine whether exposure to stress functions as an intergenerational risk process for depression specifically, or to various forms of anxiety as well.

Mutuality and Bidirectionality: Accounting for Linked Lives

A wealth of evidence has examined parental impacts on youth outcomes (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2017; Schwartz et al., 2017), and a growing literature demonstrates that youth effects on parent functioning represent an important, if understudied, developmental phenomena (Lougheed, 2020; Pardini, 2008). Life course theories of development emphasize the interdependence of parent and child’s “linked lives,” and highlight the role of transactional parent-child processes in contributing to outcomes for both parent and child (Elder, 1998). Consistent with this theoretical framework, researchers have recognized that child psychopathology has downstream effects on family stress (Chan et al., 2014), parenting behaviors (Moore et al., 2004), and parent symptoms of depression (Kouros & Garber, 2010). Limited research has been conducted, however, to evaluate how trajectories of parent and child stress are intertwined across adolescent development, nor mechanisms linking child internalizing psychopathology with parental depression across adolescent development.

Existing research examining bidirectional associations between parent and child psychopathology has yielded a mixed pattern of results, and work is needed to clarify discrepancies and tensions in the current body of knowledge. Numerous studies have found evidence for bidirectional associations between parent and child depressive symptoms during adolescence. For example, Kouros and Garber (2010) used sophisticated analytic techniques to disentangle between- from within- dyad variance and a repeated-measures design in which mother and adolescent depression symptoms were assessed annually for a period of 6 years. Their results demonstrated prospective, bidirectional within-dyad associations between mother and adolescent depressive symptoms across time. Johnco et al. (2021) also found evidence for reciprocal associations between parental depressive symptoms and adolescent symptoms of anxiety and depressive assessed annually over a period of 3 years. Of note, however, child anxiety was measured using a single composite score in this study. It is possible that discrete forms of adolescent anxiety, such as adolescent social and physical symptoms of anxiety, differentially associate prospectively with parental depressive symptoms; however, this possibility remains untested.

A contrasting literature finds much more limited support for the bidirectional associations between parent and child depressive symptoms during adolescence. For example, Mennen et al. (2018) found only limited evidence for reciprocal effects of parent and child depressive symptoms in a three time-point study spanning a period of 2.5 years. Specifically, researchers found that adolescent depressive symptoms predicted parent depressive symptoms only among boys (Mennen et al., 2018). Hastings et al. (2021) also found evidence that effects of adolescent depressive symptoms on parental depressive symptoms may be conditional in nature, such that adolescent effects on parent were only observed among youth high in physiological reactivity. Further, research by Felton et al. (2021) in a sample of early adolescent youth found that youth depressive symptoms predicted changes in maternal emotion regulation, but not changes in maternal depressive symptoms, per se, over time. Subsequent research conducted among two independent samples of adolescent youth assessed every three months for 2-3 years found no evidence reciprocal within-dyad change in parent and adolescent depressive symptoms across three months, although associations were found between stable, trait-like elements of parent and adolescent depression, as well as contemporaneous co-fluctuations in within-dyad parent and adolescent depression at any given point in time (Griffith et al., 2021).

Research on the longitudinal coupling of parent and child symptoms during earlier periods of the lifespan has also yielded mixed and sometimes inconsistent findings. Work conducted using a large cohort sample assessed repeatedly beginning at age 3 found complex patterns of relations between child and parent internalizing distress, with differences noted by gender (Speyer et al., 2022). For example, reciprocal associations between maternal distress and boys internalizing symptoms were observed, whereas maternal distress was not predicted by girls’ internalizing symptoms. In another prospective longitudinal study of mother-child dyads followed from age 1 to 4.5, Curci et al. (2022) demonstrated reciprocal, within-dyad associations between maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems. In contrast, results of work by Xerxa et al. (2021) in a large sample of parent-child dyads found no evidence for bidirectional associations between youth behavior problems, as assessed between ages 1.5 and 10, and parental psychopathology. Together, this body of work indicates the need for more research clarifying prospective, bidirectional patterns of effects between parent and child symptoms of psychopathology.

Less research has aimed to examine interconnections between parent and child stress, and their relations with parent and child internalizing symptoms, across adolescent development. Some indications that parent and youth stress co-develop over time in ways that support the longitudinal coupling of internalizing symptoms can be drawn from studies examining prospective effects of child psychopathology on family-level processes, including parenting behaviors and family stress. Mothers of anxious children, for example, have been found to demonstrate less warm and autonomy-supportive parenting, which may function to both increase child stress, and reinforce youth symptoms of psychopathology (Moore et al., 2004). Moreover, preadolescent youths’ depressive symptoms have been found to prospectively predict the generation of dependent family stress assessed using contextual-stress interview measures across a one year follow up period, indicating that youth internalizing psychopathology may introduce stressors into the family-system, which may downstream effects on parents’ own intrapersonal stress exposure (Chan et al., 2014). An integrated model evaluating parent and child co-occurring stress trajectories, as well as the role of these stress trajectories in potentiating the longitudinal coupling of parent and child symptoms, however, has not been previously tested.

The Present Study

The present study investigated the extent to which trajectories of parent and child stress co-occur during adolescence. Additionally, the present work examined the role of parent and child stress trajectories in mediating the prospective, bidirectional associations between parent and child depressive symptoms across a 36-month period. Last, the present study aimed to clarify the specificity of associations between symptoms of parental depression and child internalizing psychopathology by examining associations between parental depressive symptoms, parent and child stress trajectories, and youth depression, physical anxiety, and social anxiety symptoms.

Parent symptoms of depression and youth symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed at baseline and 36-months later. Parent and child stress were assessed every three months. We evaluated co-occurring parent-child stress using a bivariate latent growth curve modeling (LCGM) approach, allowing us to evaluate the role of (1) initial levels of stress and (2) trajectories of stress in mediating associations between parental depression and child internalizing symptoms. Multiple group models were used to evaluate the extent to which patterns of associations differed according to child gender and child grade cohortFootnote 1, given previous research indicating that girls demonstrate heightened interpersonal sensitivity and reactivity to stress during adolescence (e.g., Cyranowski et al., 2000; Hankin et al., 2007; Rudolph, 2002), and the magnitude of associations between parental depression and youth internalizing outcomes may vary across child development (Goodman et al., 2011).

We hypothesized that parent and child stress trajectories (i.e., intercepts and slopes) would be positively related, such that parents who demonstrated higher initial levels and more rapid change in stress would have children who also demonstrated higher initial levels and more rapid same-direction change in stress over time. Further, we hypothesized that parental depressive symptoms at baseline would be positively associated with intercepts and slopes of youth stress across the follow-up period, and that youth stress trajectories would mediate the prospective associations between parental depressive symptoms at baseline and youth depressive symptoms at 36-months. We expected to observe a similar pattern of prospective associations with respect to youth symptoms of physical and social anxiety. Moreover, we expected that patterns of prospective associations would be stronger among girls relative to boys. We made no a priori hypotheses regarding group differences by grade cohort. Previous findings regarding child effects on parental depression are mixed (e.g., Garber & Cole, 2010; Kouros & Garber, 2010; Mennen et al., 2018; Xerxa et al., 2021), so we did not make a priori hypotheses whether child depression and anxiety symptoms and parent-child co-occurring stress would predict parental depressive symptoms over time.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants included youth and a parent recruited in 3rd, 6th, and 9th grade cohorts (full study N=680, age 8-16 at baseline, Mage = 11.87, SDage = 2.41, 56.7% female) in association with the Gene, Environment, and Mood (GEM) Study (Hankin et al., 2015). Participating parents included mothers (89.4%), fathers (6.0%), and other caregivers (1.2%).Footnote 2 Inclusion criteria included English language fluency, absence of autism or psychotic disorder diagnosis, and IQ > 70 as assessed via parent report. The sample identified as 68.3% White, 11.4% African American, 9.2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.7% Multi-racial, 5.6% Other racial identity, with 11.9% identifying as having a Latinx ethnic identity. Further details regarding the sample are described in Hankin et al. (2015). When parents participated with more than one child, one sibling was randomly chosen to be included in the present analyses. Data with which to evaluate co-occurring stress trajectories were available from 618 dyads, and data from 583 dyads were available to evaluate relations between stress trajectories and internalizing symptoms. Participants included in the present analyses did not differ from excluded dyads based on child age (t=-0.19, df=588, p=.852) or gender (t=-1.04, df=595, p=.300), nor on child symptoms of depression (t=.40, df=588, p=.692), social anxiety (t=-1.60, df=673, p=0.110), or physical anxiety (t=.38, df=672, p=.706) at baseline. Included dyads also did not differ from excluded dyads based on parental depressive symptoms (t=1.05, df=591, p=.297). Number of assessment points completed with negatively related with parent (r=-0.14) and child (r=-0.15) baseline depressive symptoms. Number of assessments completed was not significantly correlated with youth age or symptoms of anxiety at baseline (r’s<|0.01-0.08|).

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).Footnote 3 Upon enrolling in the study, parent-child dyads were invited to the laboratory, where written informed consent and assent were obtained. Parent-child dyads were assessed every 3 months for 36 months (13 time points). Parent and youth symptoms were assessed via self-report at the baseline and 36-month assessments. Self-report measures of stress were administered at 3-month intervals between the 3- and 33-month assessment points, yielding 11 timepoints of parent-child stress data. Both child and parent participants received monetary compensation. Specifically, dyads could earn up to $190 for their participation in the study.

Measures

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 2003)

Youth depressive symptoms were measured at baseline and 36-months via self-report on the CDI (Kovacs, 2003). The CDI comprises 27-items assessing youths’ experience of a range of symptoms associated with depression. For each item, youth were asked to indicate which of a series of statements best described them on a 0 (e.g., “I am sad once in a while”) to 2 (e.g., “I am sad all of the time”) scale. For the purposes of the present analyses, youth depressive symptoms were represented using a sum score, with a possible range of 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating higher depressive symptoms. The CDI demonstrates good psychometric properties, including convergent validity, as evidenced by correlations with other measures of depression and related constructs (Klein et al., 2005). Internal reliability (Cronbach’s \(\mathrm{\alpha })\) of the CDI in the present sample ranged from .79-.90.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., 1997)

Youth symptoms of anxiety were measured at baseline and 36-months via self-report on the MASC (March et al., 1997). The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, and harm avoidance, and shows good reliability and validity (March et al., 1997). For each item, youth were asked to indicate how true a statement is for them (e.g., “I worry about other people laughing at me”) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Never true about me” to 3 (“Often true about me”). The decision was made a priori to focus on the physical symptoms (MASC-PH) and social anxiety (MASC-SA) subscales in the present study, which are associated with risk for their specific disorders and demonstrate discriminant validity (March et al., 1997; van Gastel & Ferdinand, 2008; Wei et al., 2014). That is, the physical symptoms subscale is associated with risk for panic disorder, and the social anxiety subscale is associated with risk for social anxiety disorder. The harm avoidance subscale of the MASC displays poor discriminant validity, and is either uncorrelated or negatively correlated with the other subscales (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007; Snyder et al., 2015). The separation anxiety subscale was not included given that separation anxiety disorder commonly onsets prior to adolescence (Beesdo et al., 2009; Kessler et al., 2005), and shows differential patterns of relations with youth symptoms of depression relative to symptoms of social and physical anxiety (Long et al., 2019). Further, existing evidence supports prospective associations between youth stress and social anxiety and youth stress and physical symptoms of anxiety (Hamilton et al. 2016; Hankin, 2008a) and shared mechanisms of risk between youth depression and social anxiety and youth depression and panic disorder (Cummings et al., 2014). The physical symptoms subscale comprises 12 items, with a possible score range of 0 to 36, and the social anxiety subscale comprises 9 items, with a possible score range of 0 to 27. Subscale scores were generated by computing a sum score of the items in each subscale. Cronbach’s \(\mathrm{\alpha }\) across subscales and assessments were >.80 in the present study.

Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996)

Parental depressive symptoms were measured at baseline and 36-months via self-report on the BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996). The BDI-II comprises 21 items assessing parents’ experience of a range of symptoms associated with depression. Each item is scored on a 0 (e.g., “I do not feel sad”) to 3 (e.g., “I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it”) Likert scale. For the purposes of the present study, parental depression was represented using a sum score with a possible range of 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. Numerous studies have found that the BDI demonstrates strong internal reliability (\(\mathrm{\alpha }\) > .75) in both clinical and non-clinical samples, and BDI scores have been found to demonstrate good convergent and content validity (Richter et al., 1998). Cronbach’s \(\mathrm{\alpha }\) in the present sample ranged from .90-.94.

Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002)

Youth stress was measured every 3 months via self-report on the ALEQ (Hankin & Abramson, 2002). The ALEQ comprises 37 items assessing the experience of a range of negative events (e.g., academic, social, and family problems). The ALEQ have been found to demonstrate good test-retest reliability and validity (Calvete et al., 2013; Hankin, 2008a, b). For the present study, youth stress was represented using a sum score indicating the total number of stressors endorsed by youth participants at each of the 11 respective time points.

Life Events Inventory (LEI; Cochrane & Robertson, 1973)

Parent stress was measured every 3 months via self-report on the LEI. The LEI comprises 36 items assessing the experience of a range of stressful life events (e.g., work, family, financial difficulties). For each item, respondents were prompted to indicate whether to not they experienced a given stressor (e.g., "changes related to your job,” “involvement in a fight,” “money problems,” etc) in the preceding three months. Total parental stress was represented in the present work using a sum score with a possible range of 0 to 36. Higher scores indicate higher stress. The LEI demonstrates good content validity and captures a range of theoretically and practically relevant stressors (Cochrane & Robertson, 1973). For the present analyses, parent stress was represented using a sum score indicating the total number of stressors endorsed by parent participants each of the 11 time points.

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM) implemented in the ‘lavaan’ library in R (Rosseel, 2012; R Core Team, 2013) using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to account for missing data and maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation due to non-normality of data. Goodness of fit was assessed using convergence across multiple fit indices, including RMSEA, SRMR, and CFI (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Good fit was indicated by RMSEA≤0.06, SRMR≤0.08, and CFI≥ .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Acceptable fit was indicated by RMSEA≤0.08 and CFI≥.90. We prioritized convergence across indices over reliance on any one particular measure of fit (Barrett, 2007; Chen et al., 2008).

Parallel growth in parent and youth life stress was modeled using latent growth curve modeling (LGCM). First, separate univariate growth curve models were fit to identify trajectories of parent and child life stress, respectively. An unconditional means (no-growth) model was fit to each domain, followed by a linear and a quadratic model. Models were compared across fit measures, as well as AIC and BIC to identify the best fitting growth model for each domain. Both parent and child stress trajectories were best characterized by linear growth (Supplemental Table 1); thus, linear models were retained for all subsequent analyses.

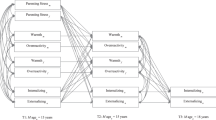

We next fit a parallel growth model to the data in which growth parameters (i.e., intercepts and slopes) of the best fitting models were covaried (Fig. 1). Residual variance terms were covaried within timepoint to account for interdependence of parent and adolescent data. As we did not have theoretical reason to believe that the magnitude of residual covariances would differ across assessment occasions, within-timepoint covariances were constrained to be equal to one another across all time points to maximize statistical power. To examine prospective relations between parent and child symptoms and co-occurring stress trajectories, we then fit a model in which co-occurring growth parameters were simultaneously regressed on parental BDI, as well as child CDI, MASC-SA, and MASC-PH scores at baseline. BDI, CDI, MASC-SA, and MASC-PH scores at 36 months were also regressed on their corresponding baseline score, as well as co-occurring stress intercepts and slopes (Fig. 2).

Structural model corresponding to the parallel process latent growth curve analysis evaluating patterns of association between starting levels (i.e., intercepts) and rates of change (i.e., slopes) in parent and child self-reported stress levels over time. ALEQ = Adolescent Life Events Questionnaires. LEI = Life Events Inventory

Structural model corresponding to structural regression analyses evaluating bidirectional, longitudinal associations between parental depressive symptoms, co-occurring parent and child stress trajectories, and child internalizing symptoms. Covariances between relevant variables were modeled but are omitted from the present diagram for ease of interpretation. Child gender and grade cohort were also included as covariates, although they are not pictured in the present diagram. BSL = baseline

Formal tests of mediation were conducted in an SEM framework based on 95% confidence intervals generated using 1000 bootstrapped samples (Cheung & Lau, 2008; MacKinnon et al., 2002). All pathways specified in Fig. 2 were included in mediation modeling; however, indirect effects were evaluated only for pathways that emerged as significant in the preceding analyses in the interest of power and parsimony.

Multiple Group Models

To evaluate whether patterns of effects varied by child gender or grade cohort, we conducted multiple group models. First, we specified a model in which all regression paths were constrained to be equal across groups (e.g., boys and girls). Next, we specified a model in which all regression paths were permitted to vary between groups. We then compared the fully constrained model to the relatively unconstrained model using chi-squared difference tests, as well as on multiple fit indices, including change in RMSEA and CFI and change in AIC and BIC. By constraining and un-constraining regression paths, differences in model fit could be interpreted as reflecting group differences in associations of interest to the present hypotheses. Models were determined to not vary if the chi-square difference test was not significant and/or comparison across multiple fit indices indicated equivalent fit. ΔRMSEA≤0.015, ΔCFI≤0.01, and ΔAIC/BIC≤10 were applied as criterion indicating relative equivalence in model fit (Chen et al., 2008; Chen, 2007).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1. A complete correlation matrix is available on OSF (https://osf.io/7j3er/). Mean levels of child-reported physical symptoms of anxiety, social anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms were comparable to levels reported in similar community samples of adolescents (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007; Reed-Knight et al., 2014). Likewise, parental levels of depression were also comparable to levels of depressive symptoms observed in similar adult community samples (Beck et al., 1996; Roelofs et al., 2013. Parent and child stress were modestly correlated with one another (r's=0.09-.27). Parental depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with concurrent child depressive symptoms (r=0.10), as well as child depression (r=0.16) and physical anxiety (r=0.15) symptoms at 36-months. Parental depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with parental stress across assessment points (rs=.24-0.41). Child depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with child stress across the duration of the study (rs=.24-0.35).

Co-occurring Stress Trajectories

A parallel process LGCM with latent intercepts and linear slopes characterizing parent and child stress trajectories across 11 time points demonstrated good fit (CFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03, SRMR=0.05). Results are reported in Table 2. Parent and child stress intercepts were positively related (β=0.30, p<0.001); parents with high initial levels of stress had children who also reported high initials levels of stress. Slopes of parent and child stress were also positively related (β=0.18, p=0.04). Relative rate of change in parental stress was related to the rate of same-direction change in child stress. Parents who changed more rapidly in stress tended to have children who also changed more rapidly in stress relative to their peers (Fig. 3). The intercept of parental stress was additionally related to the slope of child stress (β=-0.15, p=0.028); parents reporting higher initial levels of stress tended to have children who reported high, relatively stable levels of stress (Fig. 4). The intercept of child stress was not significantly associated with the slope of parent stress (β=-0.10, p=0.183).Footnote 4

Associations between Co-occurring Stress Trajectories and Internalizing Symptoms

A model including bidirectional relations between parent depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms and co-occurring stress trajectories (Fig. 2) fit the data well (CFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03, SRMR=0.04). Multiple group analyses indicated that a model in which all regression paths were constrained to be equal across youth genders did not fit significantly worse than a model in which all regression paths were free to vary (Δχ2=49.45, df=40, p=0.145), indicating that patterns of prospective associations did not significantly vary across boys and girls. Similarly, multiple groups models indicated no significant difference in patterns of prospective relations according to youth grade cohort (Δχ2=920.04, df=72, p=0.056; see Supplemental Table 2 for complete fit indices for all multiple group models).Footnote 5 Thus, data were collapsed across the entire sample for analyses. Gender and grade cohort were entered as covariates to account for mean-level differences in key variables based on youth gender and grade. Results of structural regression analyses are reported in Table 3.

Paths from baseline symptoms to later stress trajectories

Baseline levels of parental depressive symptoms (β=0.08, p=0.031) predicted intercepts of child stress at 3-months; children of parents higher in depression reported higher initial levels of stress at the 3-month assessment. Child baseline levels of depression (β=0.18, p<0.001), social anxiety (β=0.09, p=0.035), and physical anxiety symptoms (β=0.27, p<0.001) also predicted the intercept of child stress at 3-months. Neither parent nor child symptoms at baseline predicted the slope of child stress (βs=-0.13-0.05, ps>0.05). Baseline levels of parental depressive symptoms (β=0.45, p<0.001) also predicted the intercept of parent stress at 3-months. Baseline child depression and anxiety symptoms were not associated with the intercept of parent stress (βs=-0.06-0.10, ps>0.05). Neither parent nor child baseline symptoms predicted the slope of parent stress (βs=-0.03-0.06, ps>0.05).

Paths from earlier stress trajectories to later symptoms at 36-months

As reported in Table 3, significant pathways emerged from the intercept and slope of child stress trajectories to later child symptoms (assessed at 36-months) of depression (βint=0.29, p<0.001; βslope=0.42, p<0.001), social anxiety (βint=0.23, p<0.001; βslope=0.44, p<0.001), and physical anxiety (βint=0.34, p<0.001; βslope=0.38, p<0.001). Children who started higher or demonstrated more rapid growth in stress between 3- and 33-months reported higher levels of depression, social anxiety, and physical anxiety 3 years later, controlling for baseline symptoms (Fig. 5a-c). Child physical anxiety at 36-months was also positively associated with the slope of parental stress (β=0.15, p=0.031). Children of parents who increased more rapidly in stress reported higher levels of physical anxiety at 36-months, controlling for baseline physical anxiety. Parental depression at 36-months was positively associated with the intercept (β=0.38, p<0.001) and slope (β=0.42, p<0.001) of parental stress trajectories. Parents who started higher and/or increased more rapidly in stress reported higher levels of depression at 36-months, controlling for baseline depression. Parental depression at follow-up was not related to the intercept of child stress (β=0.05, p=0.379). A small effect was observed of the slope of child stress on parental depression at follow up (β=0.09, p=0.051).Footnote 6

Indirect Effects of Parental Depression on Child Internalizing through Child Stress

Given the preceding patterns of results, we evaluated indirect effects of baseline parental depression contributing to child depression, social anxiety, and physical anxiety symptoms at 36-months through youths’ stress levels at 3-months (i.e., child stress intercept). Mediation analyses found that baseline elevated parental depressive symptoms contributed to more child stress 3-months later, which in turn prospectively predicted increases in child internalizing outcomes at 36-months (Fig. 6). Specifically, the intercept of child stress partially mediated the prospective relations from baseline parental depressive symptoms to later child depression (b=0.03[0.003, 0.05]), social anxiety (b=0.02[0.003, 0.04]), and physical anxiety symptoms (b=0.03[0.004, 0.06]).

Results of mediation analyses evaluating the intercept of child stress as a mediator of prospective relations between parental depression and child symptoms of depression, social anxiety, and physical anxiety. Indirect effect estimates are reported using unstandardized coefficients. For ease of interpretation, all other estimates are reported using standardized coefficients. *p<0.05

Discussion

Stress has long been implicated as a mechanism in the intergenerational transmission of depression (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). However, the longitudinal inter-relations of parent and adolescent stress, and the role that these interrelated trajectories may play in prospective, bidirectional associations between parental depression and child internalizing symptoms has not been rigorously evaluated. The present work demonstrated that trajectories of parent and child stress were positively related across a 3-year period, suggesting that co-occurring longitudinal changes in individual parent and child stress levels may contribute to mutually reinforcing patterns of stress accumulation within parent-adolescent dyads. Moreover, bidirectional effects were observed between parental depressive symptoms and youth internalizing outcomes. Last, mediation analyses indicated that child stress levels partially mediated prospective relations between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms. Higher baseline levels of parental depression predicted greater child stress 3-months later, and in turn, elevated child stress levels at 3-months predicted increases in child internalizing outcomes at 3-year follow up. These results lend support to developmental psychopathology models proposing that parental depression may confer transdiagnostic risk for child internalizing psychopathology in part via the effects of parental depression on child exposure to stressful life experiences.

Building upon principles of life course theories of development that emphasize the salience of linked lives in predicting key outcomes during developmental “turning points” (Elder, 1998), the present work modeled reciprocal processes of parent-adolescent co-influence with respect to stress during a vulnerable period of child development. Results show that longitudinal trajectories of parent and child stress are associated over time, such that parents whose stress is increasing more rapidly relative to other parents have children whose stress is increasing more rapidly relative to their peers. As highlighted by life course and developmental ecological systems theories (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Elder, 1998), both between-dyad (e.g., poverty, exposure to adversity) as well as within-dyad (e.g., parent-adolescent conflict, interpersonal withdrawal) factors likely contribute to the co-occurrence in parent and child stress. Consistent with these notions, findings indicate that increasing trajectories in parent and/or child stress should serve as an indicator of risk in the dyad more broadly, and may be a useful cue to trigger preventive interventions at both the individual and dyadic level to circumvent cascading patterns of risk and vulnerability to psychopathology.

Present findings advance knowledge of processes of intergenerational symptom transmission by demonstrating that increases in youth stress levels partially mediate prospective associations between parental depression and youth depression and youth physical and social anxiety, even after statistically accounting for co-occurring parental stress trajectories. The findings are consistent with work showing that child stress is involved in explaining, in part, the intergenerational transmission of depression (e.g., Garber & Cole, 2010; Hammen et al., 2004; Hammen et al., 2012). The present results advance this literature by demonstrating that increases in youth stress related to parental depression also predict changes in youth symptoms of anxiety over three years, accounting for co-occurring symptoms of depression. The pattern of findings is consistent with meta-analytic work finding that parental depression relates transdiagnostically to youth internalizing outcomes (Goodman et al., 2011), as well as literature implicating stress in the etiology of adolescent anxiety (Hamilton et al., 2016; Hankin, 2008a). Together, these findings implicate youth stress as an important target for interrupting intergenerational risk processes in the development and maintenance of internalizing symptoms for both parents and children. Moreover, patterns of associations did not differ across youth genders and grade cohorts, suggesting that stress functions as a transdiagnostic mechanism linking parent depression with youth internalizing across both gender and age.

Interestingly, parental stress trajectories prospectively predicted youth physical anxiety, but not youth depression or social anxiety across the follow up period. The slope of parent stress across the follow-up period positively related to youth symptoms of physical anxiety at 36-months, controlling for youth baseline physical anxiety levels. That is, parents who increased faster than other parents in stress had children who experienced increases in physical symptoms of anxiety. To the extent that children perceive their parents’ increasing stress to be unpredictable and uncontrollable, exposure to increasing trajectories of parental stress may contribute to increased anxiety sensitivity and associated physical symptoms of anxiety among youth (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009). In line with this hypothesis, research has found that adults demonstrating clinical levels of panic disorder, characterized by heightened physical anxiety, are particularly sensitive to stressors perceived to be unpredictable (Grillon et al., 2008). Future research is needed to replicate the present pattern of findings and examine potential mechanisms (e.g., changes in anxiety sensitivity), by which exposure to parental stress contributes to changes in youths’ physical symptoms of anxiety.

Parental stress trajectories were not significantly related to youth subsequent depression or social anxiety in this study. This finding is inconsistent with results of previous research implicating increases in parental stressful life events in the etiology of youth depression (Garber & Cole, 2010). Notably, however, previous work did not account for youth’s own co-occurring experience of stressful life events. Present results suggest that prospective associations between parental stress and youth depression observed in previous studies may be better accounted for by stress affecting the adolescent, specifically, rather than stress endemic to the broader family environment. This explanation is further supported by results of follow-up analyses, in which parent and child stress trajectories were examined separately in prospective models (see Supplemental Materials), revealing that effects of parent stress trajectories on youth symptom outcomes emerge only when youths’ own stress levels are unaccounted for. These findings suggest that among children of parents high in depression, interventions targeted specifically at youth mean levels of stress may more directly target youth risk for depression and anxiety. Moreover, results highlight the need for future research to disentangle processes by which parent stress contributes to and reinforces child stress on varied timescales (e.g., months, years) to inform interventions to effectively disrupt transdiagnostic mechanisms of intergenerational risk transmission.

Findings yielded limited support for the presence of child effects on parents. Specifically, the slope of child stress trajectories was modestly related to change in parental depression across the follow-up period. Results suggest that accounting for parents’ own stress levels, exposure to their children’s increasing experience of stress may have a depressogenic effect, reinforcing parental psychopathology. This interpretation is tentative but represents a compelling area for future research. It may be that the timescale at which change was measured in the present work was not optimal for capturing dynamic processes by which child stress influences parent symptoms. As highlighted by recent work investigating the within-dyad longitudinal coupling of parent and adolescent depression, issues of timescale are key to understanding patterns of intergenerational risk (Griffith et al., 2021). Future research can clarify if and at what timescale changes in child stress influence parental symptom experience.

Contrary to expectations, youth internalizing symptoms did not predict individual differences in parental stress trajectories. One potential explanation for these findings is that parental stress was relatively stable across the study period, limiting the variance in parental stress trajectories that could be predicted by youth internalizing symptoms. It is also possible that the types of parental stress most likely to be impacted by youth internalizing symptoms are not well-captured by the LEI, as many events measured by the LEI include “fateful” or uncontrollable stressors (e.g., prolonged ill health) to which a child’s internalizing symptoms would not contribute. As evidence indicates that interpersonal stressors are especially likely to both predict and be predicted by depressive symptoms (Hammen, 1988), youth internalizing problems may be especially likely to contribute to parental interpersonal stress trajectories.

The present study demonstrates a number of strengths that advance knowledge of mediators driving longitudinal coupling between parental depression and youth internalizing symptoms. Participating dyads were assessed every three months for three years, yielding rich repeated measures data and permitting more reliable and precise modeling of co-occurring parent and child stress trajectories. Moreover, using an advanced SEM approach, the present work evaluated a mediation model capturing pathways of bidirectional influence, as well as co-occurring mechanism of change, thus isolating unique associations between parental depression, parent-child stress trajectories, and youth internalizing symptoms.

Findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations which represent important directions for future research. Stress was measured using self-report questionnaires, and future work may wish to replicate findings using alternative methods (e.g., interview measures). Moreover, it is possible that at least some of the relationship between parent and child stress trajectories may be attributed to family-related stressors shared across parents and children. Future work using methods such as contextual stress interviews (see e.g., Hammen et al., 2009), which are well-suited to disentangle nuanced aspects of individuals’ stress exposure (see Harkness & Monroe, 2016), may bolster confidence in findings. Given that all variables were assessed using self-report questionnaires measures, it is possible that shared method variance played some role in observed patterns of results, although it must be noted that the integration of multiple informants (i.e., parent-report of parental depressive symptoms and parent stress, child-report of child internalizing symptoms and stress) lends support for the present pattern of findings. Additionally, all variables were representing using manifest indicators in the present work. The use of manifest indicators is a common feature of research in developmental psychopathology; however, methodologists have highlighted that the use of manifest indicators may yield less reliable estimates that are more susceptible to measurement error relative to latent path analysis (see Cole & Preacher, 2014). Future work should aim to replicate findings using larger sample sizes and multimethod designs to strengthen confidence in findings.

Of note, participating dyads predominantly identified with a non-Latinx, white racial identity. Results should be replicated in more diverse samples of youth to evaluate whether patterns of associations differ among individuals of different racial, ethic, and other social identities. The experience of racial discrimination and other forms of minority stress, for example, are likely to function as relatively unique risk factors for internalizing symptoms amongst individuals and families with historically marginalized identities (see e.g., Arbona & Jimenez, 2014; Chodzen et al., 2019; English et al., 2014; Woody et al., 2022). The extent to which patterns of results observed in the present work may replicate after accounting for structural inequality and associated forms of stress is unclear. Finally, participating caregivers were predominantly mothers. Research is needed to extend this line of work to samples of fathers and other caregivers.

The present study contributes to understanding of intergenerational risk processes of internalizing psychopathology by characterizing co-occurring trajectories of parent and child stress. Results illustrate that increases in youth stress mediate the prospective longitudinal associations between parental depression and youth depression, physical, and social anxiety across youth age and gender. Findings highlight youth experience of stress as a significant transdiagnostic mechanism via which intergenerational transmission of psychopathology occurs during adolescence.

Data Availability

The datasets analysed during the current study may be available from the senior author on reasonable request.

Notes

As described in the study Methods, sampling for the present study was conducted using an accelerated longitudinal cohort design such that youth were recruited in discrete 3rd, 6th, and 9th grade cohorts. Due to this sampling feature, age was not distributed continuously amongst study participants. For this reason, we elected to use grade cohort, rather than age, as the clearest and most interpretable indicator of youth development in the present study.

Data concerning the participating caregiver’s relationship to the participating youth was not available in 3.4% of cases.

The following institutions provided IRB approval for the present study: University of Denver, Rutgers University, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Multiple group models in which cross-partner covariances (e.g., slope of parent stress with slope child stress, intercept of parent stress with intercept of child stress, etc.) were successively constrained and un-constrained across gender and grade cohort groups revealed that effects were not meaningfully different across boys and girls (χ2=3.36, df=4, p=.500) as well as 3rd, 6th, and 9th grade cohorts (χ2=8.73, df=8, p=.366).

Results of model comparison tests evaluating group differences in patterns of effects according to youth grade cohort were not significant according to a priori cut-offs of null hypothesis significant testing (i.e., p<0.05). Further, comparison of relative change in CFI and RMSEA fit indices indicated negligible change in relative fit across models, further supporting interpretations of invariance (see Supplemental Table 2). Nevertheless, we provide the complete model results by grade cohort in Supplemental Table 3 for interested readers. Of note, we do not endeavor to interpret small changes in parameters estimates across grade cohorts, given results of model testing. Further, results must be considered tentative given relatively limited cell sizes within each grade cohort. We hope these exploratory results serve to inform future research clarifying continuity and discontinuity in the mechanisms of intergenerational risk transmission across development.

To better understand the incremental value of simultaneously modeling co-occurring stress trajectories as potential mediators in the intergenerational transmission of internalizing above and beyond modeling individual parent and child stress trajectories alone as mediators of these prospective relations, a series of follow-up analyses were conducted. Specifically, one model was conducted in which prospective, bidirectional associations between parent and child internalizing symptoms and the intercept and slope of child stress trajectories were evaluated (Supplemental Table 4), and another model was conducted in which prospective, bidirectional associations between parent and child internalizing symptoms and the intercept and slope of parent stress trajectories were evaluated (Supplemental Table 5). Overall, models yielded a similar pattern of results to those reported in the present manuscript. Of note, when only child stress trajectories were modeled (and parents’ own stress trajectories were not accounted for), the intercept (β=0.15, p=0.007) and slope terms (β=0.11, p=0.035) characterizing growth in child stress across the follow-up period were observed to demonstrate significant positive associations with parental depressive symptoms at 36-months (Supplemental Table 4). In a similar manner, when only parent stress trajectories were modeled (and children’s own stress trajectories were not accounted for), the intercept term characterizing growth in parent stress across the follow-up period was observed to positively relate to child depressive (β=0.11, p=0.045) and physical anxiety symptoms (β=0.15, p=0.010) at 36-months (Supplemental Table 5).

References

Arbona, C., & Jimenez, C. (2014). Minority stress, ethnic identity, and depression among Latino/a college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034914

Baldwin, J. S., & Dadds, M. R. (2007). Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(2), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1

Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual differences, 42(5), 815–824.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory–II [Database record]. APA PsycTests.

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002

Bögels, S. M., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 834–856.

Brady, E. U., & Kendall, P. C. (1992). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 244-255.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Hankin, B. L. (2013). Transactional relationships among cognitive vulnerabilities, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(3), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9691-y

Chan, P. T., Doan, S. N., & Tompson, M. C. (2014). Stress generation in a developmental context: The role of youth depressive symptoms, maternal depression, the parent–child relationship, and family stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035277

Chen, F., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J., & Paxton, P. (2008). An Empirical Evaluation of the Use of Fixed Cutoff Points in RMSEA Test Statistic in Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108314720

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 464–504.

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational research methods, 11(2), 296-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107300343

Chodzen, G., Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., & Garofalo, R. (2019). Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.006

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 3.

Cochrane, R., & Robertson, A. (1973). The Life Events Inventory: A measure of the relative severity of psycho-social stressors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 17(2), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(73)90014-7

Cole, D. A., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Manifest variable path analysis: potentially serious and misleading consequences due to uncorrected measurement error. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033805

Cummings, C. M., Caporino, N. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2014). Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: 20 Years After. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 816–845. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034733

Curci, S. G., Somers, J. A., Winstone, L. K., & Luecken, L. J. (2022). Within-dyad bidirectional relations among maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems from infancy through preschool. Development and Psychopathology, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421001656

Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent Onset of the Gender Difference in Lifetime Rates of Major Depression: A Theoretical Model. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21

Elder, G. H. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

English, D., Lambert, S. F., & Ialongo, N. S. (2014). Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 50(4), 1190–1196. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034703

Felton, J. W., Schwartz, K. T., Oddo, L. E., Lejuez, C. W., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2021). Transactional patterns of depressive symptoms between mothers and adolescents: The role of emotion regulation. Depression and Anxiety, 38(12), 1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23225

Garber, J., & Cole, D. A. (2010). Intergenerational transmission of depression: A launch and grow model of change across adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000489

Goodman, S. H. (2020). Intergenerational Transmission of Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071519-113915

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for Psychopathology in the Children of Depressed Mothers: A Developmental Model for Understanding Mechanisms of Transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490.

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

Gotlib, I. H., Goodman, S. H., & Humphreys, K. L. (2020). Studying the Intergenerational Transmission of Risk for Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(2), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420901590

Grillon, C., Lissek, S., Rabin, S., McDowell, D., Dvir, S., & Pine, D. S. (2008). Increased anxiety during anticipation of unpredictable but not predictable aversive stimuli as a psychophysiologic marker of panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(7), 898–904. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101581

Griffith, J. M., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2021). Longitudinal Coupling of Depression in Parent-Adolescent Dyads: Within-and Between-Dyads Effects Over Time. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1059–1079. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621998313

Hamilton, J. L., Potter, C. M., Olino, T. M., Abramson, L. Y., Heimberg, R. G., & Alloy, L. B. (2016). The temporal sequence of social anxiety and depressive symptoms following interpersonal stressors during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 495-509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0049-0

Hammen, C. (1988). Self-cognitions, stressful events, and the prediction of depression in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16(3), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913805

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(9), 1065-1082. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20293

Hammen, C., Hazel, N. A., Brennan, P. A., & Najman, J. (2012). Intergenerational Transmission and Continuity of Stress and Depression: Depressed Women and their Offspring in 20 Years of Follow-up. Psychological Medicine, 42(5), 931–942. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001978

Hammen, C., Kim, E. Y., Eberhart, N. K., & Brennan, P. A. (2009). Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depression and anxiety, 26(8), 718–723. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20571

Hammen, C., Shih, J., Altman, T., & Brennan, P. A. (2003). Interpersonal impairment and the prediction of depressive symptoms in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(5), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000046829.95464.E5

Hammen, C., Shih, J. H., & Brennan, P. A. (2004). Intergenerational Transmission of Depression: Test of an Interpersonal Stress Model in a Community Sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511

Hanington, L., Heron, J., Stein, A., & Ramchandani, P. (2012). Parental depression and child outcomes–is marital conflict the missing link?. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(4), 520-529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01270.x

Hankin, B. L. (2008). Cognitive vulnerability–stress model of depression during adolescence: Investigating depressive symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 999–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9228-6

Hankin, B. L. (2008). Response styles theory and symptom specificity in adolescents: Investigating symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 701–713.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2002). Measuring Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression in Adolescence: Reliability, Validity, and Gender Differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex Differences in Adolescent Depression: Stress Exposure and Reactivity Models. Child Development, 78(1), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x

Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F., Abela, J. R. Z., Smolen, A., Jenness, J. L., Gulley, L. D., Technow, J. R., Gottlieb, A. B., Cohen, J. R., & Oppenheimer, C. W. (2015). Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 803–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000089

Harkness, K. L., & Monroe, S. M. (2016). The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000178

Hastings, P. D., Ugarte, E., Mashash, M., Marceau, K., Natsuaki, M. N., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Klimes‐Dougan, B. (2021). The codevelopment of adolescents' and parents' anxiety and depression: Moderating influences of youth gender and psychophysiology. Depression and Anxiety, 38(12), 1234-1244. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23183

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Johnco, C. J., Magson, N. R., Fardouly, J., Oar, E. L., Forbes, M. K., Richardson, C., & Rapee, R. M. (2021). The role of parenting behaviors in the bidirectional and intergenerational transmission of depression and anxiety between parents and early adolescent youth. Depression and Anxiety, 38(12), 1256–1266. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23197

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K., & Wang, P. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(60), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Klein, D. N., Dougherty, L. R., & Olino, T. M. (2005). Toward Guidelines for Evidence-Based Assessment of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(3), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3

Kouros, C. D., & Garber, J. (2010). Dynamic Associations between Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Adolescents’ Depressive and Externalizing Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9433-y

Kovacs, M. (2003). Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI): Technical Manual Update. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems.

Liu, R. T., & Alloy, L. B. (2010). Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.010

Long, E. E., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2019). Separating within-person from between-person effects in the longitudinal co-occurrence of depression and different anxiety syndromes in youth. Journal of Research in Personality, 81, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.06.002

Lougheed, J. P. (2020). Parent-Adolescent Dyads as Temporal Interpersonal Emotion Systems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora0.12526

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

March, J. S., Parker, J. D. A., Sullivan, K., Stallings, P., & Conners, C. K. (1997). The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor Structure, Reliability, and Validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019

McLaughlin, K. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 659–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016499

Mennen, F. E., Negriff, S., Schneiderman, J. U., & Trickett, P. K. (2018). Longitudinal Associations of Maternal Depression and Adolescents’ Depression and Behaviors: Moderation by Maltreatment and Sex. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(2), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000394

Moore, P. S., Whaley, S. E., & Sigman, M. (2004). Interactions Between Mothers and Children: Impacts of Maternal and Child Anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(3), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.471

Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017). The impact of parenting on emotion regulation during childhood and adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12238

Pardini, D. A. (2008). Novel Insights into Longstanding Theories of Bidirectional Parent-Child Influences: Introduction to the Special Section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9231-y

R Core Team. (2013). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing.

Reed-Knight, B., Lobato, D., Hagin, S., McQuaid, E. L., Seifer, R., Kopel, S. J., & Shapiro, J. (2014). Depressive symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease compared with a community sample. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 20(4), 614-621. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000442678.62674.b7

Richter, P., Werner, J., Heerlein, A., Kraus, A., & Sauer, H. (1998). On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory: A review. Psychopathology, 31(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1159/000066239

Roelofs, J., van Breukelen, G., de Graaf, L. E., Beck, A. T., Arntz, A., & Huibers, M. J. (2013). Norms for the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) in a large Dutch community sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 35(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9309-2

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more Version 0.5-12 (BETA).

Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(4, Suppl), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4

Schwartz, O. S., Simmons, J. G., Whittle, S., Byrne, M. L., Yap, M. B., Sheeber, L. B., & Allen, N. B. (2017). Affective parenting behaviors, adolescent depression, and brain development: A review of findings from the Orygen Adolescent Development Study. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12215

Snyder, H. R., Gulley, L. D., Bijttebier, P., Hartman, C. A., Oldehinkel, A. J., Mezulis, A., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2015). Adolescent emotionality and effortful control: Core latent constructs and links to psychopathology and functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000047

Speyer, L. G., Hall, H. A., Hang, Y., Hughes, C., & Murray, A. L. (2022). Within-family relations of mental health problems across childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(11), 1288–1296. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13572

Van Gastel, W., & Ferdinand, R. F. (2008). Screening capacity of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) for DSM-IV anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 25(12), 1046–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20452

Wei, C., Hoff, A., Villabø, M. A., Peterman, J., Kendall, P. C., Piacentini, J., McCracken, J., Walkup, J. T., Albano, A. M., Rynn, M., Sherrill, J., Sakolsky, D., Birmaher, B., Ginsburg, G., Keaton, C., Gosch, E., Compton, S. N., & March, J. (2014). Assessing Anxiety in Youth with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 43(4), 566–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.814541

Woody, M. L., Bell, E. C., Cruz, N. A., Wears, A., Anderson, R. E., & Price, R. B. (2022). Racial stress and trauma and the development of adolescent depression: a review of the role of vigilance evoked by racism-related threat. Chronic Stress, 6, 24705470221118576. https://doi.org/10.1177/24705470221118574

Wu, Y. P., Selig, J. P., Roberts, M. C., & Steele, R. G. (2011). Trajectories of postpartum maternal depressive symptoms and children’s social skills. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(4), 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9407-2

Xerxa, Y., Rescorla, L. A., van der Ende, J., Hillegers, M. H., Verhulst, F. C., & Tiemeier, H. (2021). From parent to child to parent: Associations between parent and offspring psychopathology. Child Development, 92(1), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13402

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE – 1746047.

Funding

The research reported in this article and work were supported by grants from the National Institute of Health to Benjamin L. Hankin (R01MH077195, R01MH109662, R01MH105501, R21MH124026, and R01HL155744) and to Jami F. Young, R01MH077178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Dr. Young has developed Interpersonal Psychotherapy - Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST) and has received royalties from sales of the book she co-authored that describes the program.

Ethical Approval

The study has been conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association. The research was approved by the University of Denver and the Rutgers University Institutional Review Boards

Informed Consent

All participants provided written consent as well as assent to participation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffith, J.M., Long, E.E., Young, J.F. et al. Co-occurring Stress Trajectories and the Longitudinal Coupling of Internalizing Symptoms in Parent-Adolescent Dyads. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51, 885–903 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-023-01046-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-023-01046-z