Abstract

Exposure to child maltreatment and maternal depression are significant risk factors for the development of psychopathology. Difficulties in caregiving, including poor emotion socialization behavior, may mediate these associations. Thus, enhancing supportive parent emotion socialization may be a key transdiagnostic target for preventive interventions designed for these families. Reminiscing and Emotion Training (RET) is a brief relational intervention designed to improve maternal emotion socialization behavior by enhancing maltreating mothers’ sensitive guidance during reminiscing with their young children. This study evaluated associations between maltreatment, maternal depressive symptoms, and the RET intervention with changes in children’s maladjustment across one year following the intervention, and examined the extent to which intervention-related improvement in maternal emotion socialization mediated change in children’s maladjustment. Participants were 242 children (aged 36 to 86 months) and their mothers from maltreating (66%) and nonmaltreating (34%) families. Results indicated that RET intervention-related improvement in maternal sensitive guidance mediated the effects of RET on reduced child maladjustment among maltreated children one year later. By comparison, poor sensitive guidance mediated the effects of maltreatment on higher child maladjustment among families that did not receive the RET intervention. Direct effects of maternal depressive symptoms on child maladjustment were also observed. This suggests RET is effective in facilitating emotional and behavioral adjustment in maltreated children by improving maltreating mothers’ emotional socialization behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Maltreatment is a transdiagnostic risk factor for the development of psychopathology (Cicchetti & Toth, 2016). Maltreating families subject children to severe and destructive failures in the caregiving environment (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006). These caregiving deficiencies are a central risk process for the development of psychopathology among maltreated children (Valentino, 2017). Similarly, maternal depression relates strongly to children’s development of psychopathology, and inadequate caregiving may contribute to this risk process (Goodman et al., 2011). Across both contexts of risk, difficulties in caregiver emotion socialization may serve as a key mechanism through which risk for psychopathology is conferred (Gottman et al., 1997).

Emotion socialization is a multi-faceted construct that includes the ways parents respond to and guide children’s emotional experiences. These parent behaviors include parents’ own expression of emotions, their reactions to children’s emotions, and their behaviors during discussions of emotion with their children (Eisenberg, 2020; Eisenberg et al., 1998). Supportive emotion socialization has been positively linked to child emotional development, including emotion knowledge and emotion regulation during early childhood (Klimes-Dougan & Zeman, 2007), and to reduced child internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Johnson et al., 2017; Kehoe et al., 2014). As such, enhancing supportive parent emotion socialization has been conceptualized as a key transdiagnostic target for preventive interventions designed for families with children at risk for psychopathology (Havighurst et al., 2015) and for families where caregivers are at risk for difficulties with emotion socialization, including maltreating parents and parents with psychopathology. In the current study, we examined maternal emotion socialization as a mediator of longitudinal associations between two risk processes, maltreatment and maternal depressive symptoms, with children’s emotional and behavioral maladjustment. Herein, children’s maladjustment refers to a composite of internalizing and externalizing behavior symptoms as well as peer problems. Using a randomized clinical trial design of maltreating and nonmaltreating families, where the maltreating families were randomized to receive an emotion socialization intervention or community standard services, we experimentally evaluated the mediating role of emotion socialization on child maladjustment and the effectiveness of our intervention on child maladjustment over time among maltreating families.

There are important individual differences in how parents engage in emotion socialization. During early and middle childhood, parent responses to child emotion are conceptualized as sensitive or supportive when parents encourage children’s expression of emotions, validate children’s emotional experiences, help children to understand their feelings, and provide opportunities to discuss how to cope with negative emotions (Morris et al., 2007). In contrast, negative parent responses minimize or discourage emotional expression and do not assist children in resolving negative emotions (Gottman et al., 1997; Morris et al., 2007). Findings from correlational research suggest that supportive parental discussions of emotions relates positively to children’s behavioral and emotional adjustment (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2009), whereas, unsupportive responses to children’s emotions relate to greater emotion dysregulation, poorer emotion coping, and increased child internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Lunkenheimer et al., 2007; Sanders et al., 2015). As such, sensitive and supportive parent emotion socialization has been conceptualized as central to children’s adjustment (Eisenberg, 2020).

One important component of emotion socialization is the manner through which parents discuss emotions with their child. During early childhood, parent–child discussions of past shared emotional events are a salient context through which parents may scaffold children’s understanding of emotions as well as how to cope with those emotions (Fivush et al., 2006; Salmon & Reese, 2016). Parent–child reminiscing about children’s past emotional experiences provides a unique opportunity for parents to communicate with their children about emotional events once emotional arousal has decreased (Laible et al., 2013; Salmon & Reese, 2016). The term maternal sensitive guidance refers to the degree to which mothers sensitively support children’s emotions during past event discussions (Koren-Karie et al., 2008; Speidel et al., 2019). Consistent with the broader construct of supportive emotion socialization, sensitive guidance includes acceptance and encouragement of children’s expression of emotions, validation of children’s emotional experiences, and the provision of opportunities to discuss how to cope with negative emotions.

Maltreatment has been associated with negative parent emotion socialization practices and poor sensitive guidance, specifically, with implications for child emotional development (Shipman et al., 2007; Speidel et al., 2020). For example, Shipman and colleagues demonstrated that maltreating mothers engaged in less validation and more invalidation in response to school-aged children’s emotions, and endorsed less emotion coaching than nonmaltreating mothers (Shipman et al., 2007). Moreover, these maternal emotion socialization behaviors mediated the association between maltreatment and children’s emotion regulation skills in a cross-sectional design. Similarly, in prior research using baseline data from the current sample, maltreatment was negatively associated with sensitive guidance and related indirectly to problems in child emotion regulation and inhibitory control through poor maternal sensitive guidance (Speidel et al., 2020). Reminiscing and Emotion Training was developed, in part, to enhance maternal sensitive guidance among maltreating families to facilitate healthy child development during early childhood.

Randomized trials offer an important opportunity to evaluate theoretical mechanisms of change in an experimental design (Cicchetti & Gunnar, 2008). To date, interventions and/or parenting programs aimed at improving parental emotion socialization have provided experimental evidence for the role of positive emotion socialization in shaping children’s emotional development. Indeed, a recent review indicates that emotion socialization programs are effective in improving parenting behaviors related to the coaching of young children’s emotion regulation (England-Mason & Gonzalez, 2020). For example, the Tuning into Kids and Tuning into Teens programs have been shown to improve parent emotion coaching and decrease emotion dismissing beliefs and behaviors (Havighurst et al., 2009, 2010), with associated improvements in child internalizing (Kehoe et al., 2014) and externalizing behaviors (Havighurst et al., 2015). While much of this work has been conducted among low-risk, community samples, there is emerging evidence that emotion socialization interventions may be useful among higher risk families as well, such as families exposed to intimate partner violence (Katz et al., 2020), or families of children with behavior problems (Salmon et al., 2009).

The current study evaluates the effectiveness of Reminiscing and Emotion Training (RET), a relational intervention which was designed to improve maternal support via enhanced elaboration and sensitive guidance during mother–child reminiscing about past emotional events among maltreating families (Valentino et al., 2013, 2019). Rooted in ecological-transactional theory on the development of maltreated children (e.g., Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006), relational interventions aim to address the sequelae of maltreatment through the enhancement of the mother–child relationship (Valentino, 2017). During early childhood, sensitive parenting shifts to emphasize verbal interactions, including supportive guidance during discussion of children’s emotions (Thompson & Meyer, 2007). RET was developed for maltreated preschool-aged children and their mothers to improve maternal elaborative and emotionally sensitive reminiscing because of the importance of this parenting process for supporting child emotional and cognitive development during the preschool age period (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Salmon & Reese, 2016), and evidence that maltreating mothers have difficulty with this parenting behavior (Valentino et al., 2015).

Evaluations of treatment outcomes with this sample have demonstrated that RET is associated with improvements in maternal elaboration and sensitive guidance immediately after the intervention (Valentino et al., 2019). RET related changes in maternal sensitive guidance are also associated with improvements in maltreated children’s emotion regulation six months following treatment (Speidel et al., 2020), and improved stress physiology one year following treatment (Valentino et al., 2020). This study extends prior work as the first to evaluate whether treatment-related gains in maternal sensitive guidance are related to improvements in maltreated children’s subsequent maladjustment. Additionally, this study evaluated whether poor sensitive guidance may serve as a parenting process that explains associations among maltreatment and maternal depressive symptoms with child maladjustment over time among untreated families. We focused on children’s maladjustment, a composite of internalizing, externalizing, and peer problems, rather than evaluating these symptoms separately because these dimensions of psychopathology are highly correlated during the preschool years (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Valentino et al., 2018).

When evaluating family-level risk processes that are associated with the development of maladjustment among young children, it is important to do so in the context of other well-established risk factors, such as maternal depressive symptoms. Maternal depressive symptoms are linked with poor child adjustment outcomes including heightened behavioral and emotional problems and lower cognitive skills (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011). Moreover, maternal maltreatment and depressive symptoms are interrelated, as depression is the most prevalent mental health concern among mothers involved with the child welfare system (Dolan et al., 2012). Multiple mechanisms may explain associations between maternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment, including shared genetic risks and disrupted parenting processes. Maternal depressive symptoms are associated with negative behaviors during interactions with their children, including expressions of irritability, sadness, helplessness, and less warmth (Goodman et al., 2011). Parents with elevated depressive symptoms may be less able to scaffold child functioning (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999), undermining the capacity for sensitive guidance and relating to emotional adjustment difficulties in young children (Kochanska et al., 1987). Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether maternal depressive symptoms are related to poor sensitive guidance and whether poor sensitive guidance is a relevant parenting process for understanding how maternal depressive symptoms relate to child maladjustment. Towards a more comprehensive understanding of processes involved with the development of child maladjustment, we evaluated how maltreatment and maternal depressive symptoms may uniquely lead to emotional problems among young children, through the potential effects of sensitive guidance.

The present study examined longitudinal associations between maltreatment, maternal depressive symptoms, and RET on child maladjustment, including their indirect effects through maternal sensitive guidance using a longitudinal design with baseline (Time 1; [T1]), 8 week (T2), 6 month (T3), and 1 year (T4) assessments. Maltreating families were randomized into RET or community standard conditions, which were delivered between T1 and T2. Nonmaltreating families were included as a second comparison group to enable evaluation of the effects of both maltreatment and the RET intervention.

We hypothesized that maltreatment (untreated) and baseline maternal depressive symptoms would be related to higher child maladjustment at T4 and continued increases in child maladjustment from T1-T4. In contrast, we hypothesized that receiving the RET intervention would be associated with decreased child maladjustment at T4, and greater decline in maladjustment from T1-T4. Furthermore, we tested maternal sensitive guidance as the mechanism of change. We expected that maltreatment (untreated) and maternal depressive symptoms would be indirectly related to increased child maladjustment at T4 and change from T1-T4 through poorer sensitive guidance at T3 and less change over time in sensitive guidance from T1-T3. By comparison, we expected that the RET intervention would be indirectly related to decreased child maladjustment at T4 and change from T1-T4 through improved sensitive guidance at T3 and more change over time in sensitive guidance from T1-T4.

Method

Participants

Families in the current study were drawn from an ongoing, longitudinal intervention study currently being conducted in a mid-sized, Midwestern city. The full sample consists of 248 mothers and their 3- to 6-year-old children (M = 4.9 years, SD = 1.14 years). To minimize any effects of co-occurring intellectual disability, n = 6 dyads (n = 1 nonmaltreating, n = 2 maltreating intervention, n = 3 maltreating control) were dropped because mothers scored more than two standard deviations below the sample mean (standard score < 60) on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007), a measure of receptive language ability. Thus, the final sample consisted of 242 mother–child dyads. Approximately two-thirds (n = 160) of these dyads had at least one documented, substantiated case of child maltreatment in which the mother was named a perpetrator and were recruited through the local Department of Child Services (DCS) office. The remaining families (n = 82) had no history of involvement with the child welfare system and were recruited to be demographically similar to the maltreating dyads. Table 1 provides demographic characteristics by maltreatment group, including results of one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests of independence used to assess for differences by group.

Maltreatment Classification

All mothers signed consent forms that allowed project staff to view any records available within the DCS system. Nonmaltreating mothers and their children were verified to have no history of DCS involvement. Maltreating mothers’ perpetration of maltreatment was verified by coding and review of their DCS records as well as a maternal interview. Maltreating mothers were only eligible to participate in the study if there was at least one substantiated or codeable case of child maltreatment by the mother on the child enrolled in the study. Trained graduate-level coders used the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS; Barnett et al., 1993) to code each case of maltreatment within the DCS records for each child within the maltreated group. The MCS was also used to categorize children’s maltreatment experiences into subtypes including sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional maltreatment and moral/legal/educational maltreatment. Within the full sample, 16% of the children experienced abuse, 66% experienced physical neglect, 59% experienced emotional maltreatment, and 38% experienced moral/legal/educational maltreatment. Further, subtype comorbidity was high with approximately 61% of children experiencing more than one type of maltreatment.

Procedure

The study’s protocol was approved by the University of Notre Dame Institutional Review Board. Mothers consented to participate in the study at each timepoint and received monetary compensation for their participation. During the baseline assessment (T1), mothers and children completed several task-based and interview measures in the lab and in their homes. Following T1, maltreating mothers were randomized into Reminiscing and Emotion Training (RET; n = 81) or a Community Standard (CS, n = 79) control group. Randomization was stratified by child age and sex to ensure similarity across groups, but not by maltreatment subtype. As such maltreatment was treated as dichotomous (1 = maltreated, 0 = nonmaltreated) throughout analyses. Nonmaltreating mothers were assigned to an assessment only nonmaltreating comparison (NC) group. Follow-up assessments were conducted 8 weeks (T2), 6 months (T3), and 1 year (T4) following the baseline assessment (T1). The intervention was delivered between T1 and T2. Pertinent to the current study, receptive language and maternal depressive symptoms were assessed at T1, while maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing and child maladjustment were assessed at each timepoint.

Intervention Conditions

RET

Maltreating mothers who were randomized to the RET condition received the Reminiscing and Emotion Training intervention, a relational intervention that seeks to train mothers to increase elaboration and sensitivity during conversations about past, shared emotional events with their children (e.g., Salmon et al., 2009; Valentino et al., 2013; Van Bergen et al., 2009). The intervention included six weekly, in-home training sessions conducted by bachelor’s level staff. In addition to reminiscing skills, sessions 2–4 included emotion-related activities to focus on emotion identification, emotion causes, and emotion regulation, respectively. Families were contacted via phone with text reminders relevant to the skills being learned that week. More details regarding RET are available in previously published work (Valentino et al., 2019).

CS

Maltreating mothers randomized into the CS condition received enhanced case management services and written parenting materials. CS mothers did not receive weekly home visits but were contacted via phone multiple times throughout the week as part of the case management services. More details regarding the CS condition are available in previously published work (Valentino et al., 2019).

Measures

Receptive Language

Mothers and children were individually administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007), which provided a reliable assessment of receptive language ability at T1. Standard scores were used as an exclusion criterion for mothers scoring lower than two standard deviations below the sample mean and as a covariate for child maladjustment scores.

Maternal Depressive Symptoms

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed at T1 using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). This measure is often used as a screening measure for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and asks respondents to rate their frequency of experiencing specific symptoms of MDD within the last week across 20 questions. The total symptom score from the CES-D was used in the current study. Within the current sample, the internal consistency was good with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79.

Child Maladjustment

Mothers reported on children’s typical behaviors on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001) across 25 items. The SDQ yields a comparison measure of children’s behaviors to their peers across several domains. The current study summed mothers’ answers across the emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, and peer problems subscales into a single composite measure of child maladjustment (Total Difficulties score). Cronbach’s alpha indicated acceptable internal consistency among the four subscales across the time points (range = 0.67-0.73).

Maternal Sensitive Guidance

At each timepoint, dyads were asked to discuss four past, shared emotional events within the lab setting as they normally would at home. Before the conversations, mothers worked with trained assessors to recall specific events in which they thought their child felt happy, sad, angry, or scared and these events were written on notecards as a reminder for mothers during the task. All dyads discussed the happy event first, and the remaining events were counterbalanced across participants. Conversations were video and audiotaped. Trained undergraduate coders used the Autobiographical Emotional Event Dialogue (AEED; Koren-Karie et al., 2003) coding system to assess for maternal sensitive guidance. The AEED has been used extensively to code conversations between adults and preschool-aged children and found to be a reliable measure of reminiscing quality (e.g., Fivush et al., 2006). Coders scored each dyad’s conversation using a series of 9-point Likert scales across several different domains including: Focus on the Task (mothers’ attention and whether she went off topic during the conversation), Acceptance and Tolerance (mothers’ encouragement of her child’s contributions to the conversations without becoming critical), Involvement and Reciprocity (mothers’ engagement and interest), Resolution of Negative Feelings (how well mothers encouraged the appropriate handling of negative emotions), Structuring (mothers’ ability to jointly construct coherent narratives), Adequacy (how well the conversations matched the given emotional themes), and Coherence (the clarity and fluency of the narratives). Coders were naive to each dyad’s group status and reliability was established using 20% of the videos; interclass correlation coefficients for individual subscales ranged from 0.73 to 0.93. For the current study, a composite score was calculated by averaging mothers’ scores across these seven maternal subscales following past work (e.g., Valentino et al., 2019). Cronbach’s alpha calculations for the composite score at each timepoint indicated very good internal consistency (range = 0.89-0.91).

Data Analytic Plan

A priori power analyses were based on 80 families in each of our three groups. For estimations of power to fit an SEM model for the hypothesized relationships among the variables of interest, we utilized methods developed by MacCallum et al. (1996). All models accounted for 20% attrition in sample size (to be conservative) with 0.08 specified as an estimate of RMSEA under the alternative hypothesis which is the recommended minimum criteria for satisfactory model fit. Power to detect medium effects (based on prior RET intervention effects (Valentino et al., 2013) exceeded 0.93 for models examining the direct mediation of the relation between intervention group and 1 year outcomes by mother–child reminiscing. Though the model we present in this paper is more complex, it has the advantage of using all data available to us regarding maternal reminiscing (sensitive guidance) and child maladjustment at all time points.

There was some attrition throughout the present RCT. Of the 242 dyads who participated in the T1 assessment, n = 221 (91.3%) participated at T2, n = 209 (86.4%) participated at T3, and n = 209 (86.4%) participated at T4. Missingness on any of the study variables included in the model was not associated with intervention group, \({\chi }^{2}\)(2, N = 242) = 4.73, ns. To further assess patterns of missingness in the data, Little’s test of missing completely at random (Little, 1998) was conducted in SPSS (Version 24, IBM Corp), and was not statistically significant (\({\chi }^{2}\)(153) = 167.05, ns), suggesting the missing data do not violate the assumption of missing completely at random. Thus, main analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data.

The primary goals of the current investigation were to assess the direct effects of maltreatment, RET, and maternal depressive symptoms on child maladjustment and change in child maladjustment over time, as well as their indirect effects through maternal sensitive guidance and change in maternal sensitive guidance over time. This objective was assessed using a single structural equation model examining longitudinal mediation with latent growth curve components to examine change in the time-varying mediator (maternal sensitive guidance assessed at T1, T2, T3, and T4) and change in the time-varying outcome (child maladjustment assessed at T1, T2, T3, and T4). Maltreatment was a dummy coded variable reflecting the presence or absence of any maltreatment occurring prior to study enrollment (1: maltreatment; 0: nonmaltreatment). RET was similarly treated as a dummy coded variable (1: RET intervention provided; 0: RET intervention not provided). This approach to dummy coding allowed for us to represent our three groups (RET, CS, and NC) in the model with two variables: RET and maltreatment, and allowed us to model the two main comparisons of interest: RET vs CS, which tells us about the impact of the intervention for maltreated children compared to maltreated children who did not receive the intervention; and CS vs. NC, which tells us about the effects of maltreatment (untreated) compared to nonmaltreated children over time. The three input variables (maltreatment, RET, and maternal depressive symptoms) were simultaneously modeled to predict the latent intercepts and slopes of maternal sensitive guidance and child maladjustment. Therefore, the individual effects of each input variable were isolated while controlling for effects of the other input variables.

Prior to fitting the full longitudinal mediation model, initial univariate latent growth curve models examining the patterns of change present in the longitudinal maternal sensitive guidance and child maladjustment data were conducted. In each of these models, two latent growth factors were formed, one representing levels (i.e. intercept) and the other representing change (i.e. slope) in the variable from T1 to T4. Latent intercept factor loadings were fixed at 1.0. In the present study, we wished to examine estimated T3 levels of maternal sensitive guidance and estimated T4 levels of child maladjustment. Thus, the slope loadings of the T3 maternal sensitive guidance indicator variable and the T4 child maladjustment indicator variable were set to 0.0. The remaining slope loadings were anchored by the appropriate time scale such that the slope estimates could be interpreted to reflect the average estimated change in that variable per year. First, a no-change (i.e. intercept only) model was assessed to determine whether the longitudinal data could be more appropriately modeled without including a latent change variable. If a no change model showed poor fit for the data, a linear growth curve model was examined to assess if linear change was a more appropriate characterization of the change in the data. If both the no change and linear change models did not prove adequate representations of the change in the longitudinal data, a latent basis growth model was further tested to allow the estimated change to fit the actual trends in the longitudinal data. Following McArdle and Nesselroade (2014), the residual variances of the manifest variables were constrained to be the same within each latent growth curve component to maintain a more parsimonious, theory-based model. All models were run in Mplus (Mplus Version 8.0; Muthen & Muthen, 2017). The bias-corrected bootstrap method (MacKinnon et al., 2004) with 1,000 resamples was used to construct 95% confidence intervals around the indirect effects to assess the presence of statistically significant mediation. Model fit was assessed using the following fit indices: the chi square test, for which a nonsignificant test statistic indicates good fit; the comparative fit index (CFI) for which a value above 0.90 indicates adequate fit and a value above 0.95 indicates good fit (Bentler, 1990); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for which a value less than 0.08 indicates mediocre fit and a values less than 0.05 indicates good fit (MacCallum et al., 1996); and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) for which a values of less than 0.08 is considered a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Demographic characteristics of the present sample by maltreatment group, including results of one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests of independence used to assess for differences by group, are presented in Table 1. The groups were matched on all demographic variables, except for child language, F(2,232) = 11.53, p < 0.001 and maternal ethnicity, \({\chi }^{2}\)(4, N = 242) = 10.72, p = 0.03. Child language was included in the model as a covariate on the child maladjustment outcomes. Follow up one-way ANOVAs revealed that maternal ethnicity was not significantly associated with any of the other model variables. Therefore, maternal ethnicity was not considered as a covariate in the main analysis. Families’ DCS records were reassessed at T4; n = 38 children experienced a new report of maltreatment between the T1 and T4 assessment (as substantiated by DCS or the Maltreatment Classification System). New maltreatment experience (1: experienced new maltreatment, 0: no new maltreatment) was also included as a covariate throughout the model.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the primary variables of interest are presented in Table 2. Continuous depressive symptoms scores were used throughout analyses, however, it is important to note that when using the recommended clinical threshold score of 16 on the CES-D, 31.5% of mothers scored in the clinical range. Statistically significant standardized results are reported below for the main hypothesized effects. Full unstandardized model results are presented in Table 3.

Modeling Procedures

Modeling procedure for maternal sensitive guidance

The model fit of a no change (χ2 (11) = 44.64, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.83, SRMR = 0.15) and linear change model (χ2 (8) = 44.16, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.14, CFI = 0.82, SRMR = 0.14) were poor. A latent basis growth model fit showed good fit χ2 (6) = 10.47, p = 0.11, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.04) therefore the latent basis growth model was used to model the change in maternal sensitive guidance over time. T1 sensitive guidance was set to -0.5, and T3 sensitive guidance was set to 0. The freely estimated sensitive guidance loadings for T2 and T4 were 0.107 and 0.016 respectively, suggesting steep initial change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T2 (immediately after the intervention), followed by a slight decline and then a plateau over time. The average estimated change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T4 was statistically significant, indicating an increase in sensitive guidance over time (b = 0.41, SE = 0.13, p = 0.001). The latent basis growth model was used to characterize the change across time in maternal sensitive guidance in the main analysis.

Modeling procedure for child maladjustment

Model fit of a no change model was adequate according to two of the four fit indices (χ2 (11) = 53.18, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.13, CFI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.08). The model fit of a linear change model improved model fit (χ2 (8) = 27.44, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.10, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.04). Further, in the linear growth curve model, the average estimated change in child maladjustment was statistically significant in that on average, child maladjustment declined across T1 to T4 (b = -1.49, SE = 0.33, p < 0.001). Due to the improved model fit, the linear change model was used to characterize the change across time in child maladjustment in the main analysis.

Longitudinal Mediation Model

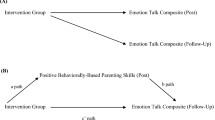

The model fit of the full model (see Fig. 1), including latent growth curve components for the mediator and outcome variables, was adequate ((χ2 (46) = 76.87, p = 0.003, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.03). There was a direct effect of maternal depressive symptoms at T1 on child maladjustment at T4 indicating that elevated maternal depressive symptoms were associated with higher maternal report of child maladjustment (b = 0.41, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001). No direct effects emerged for either maltreatment or RET on child maladjustment at T4. There were no direct effects of maltreatment, RET, or maternal depressive symptoms on change over time in child maladjustment.

Mediation model. Structural equation model depicting the indirect effects of maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing at T3 and its change from T1 to T4 on associations between maltreatment, the RET intervention, and maternal depression at T1 on child maladjustment at T4 and the child maladjustment slope from T1 to T4, controlling for child language on child maladjustment and for maltreatment between T1 and T4 throughout the model. Nonsignificant pathways are indicated by thin dashed lines and statistically significant pathways are indicated by solid lines. Standardized coefficients are reported. Maltreatment (1: maltreatment, 0: nonmaltreatment); RET (1: RET intervention provided, 0: no RET intervention provided); T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; T4 = Time 4. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

There was an effect of maltreatment on sensitive guidance at T3 (b = -0.24, SE = 0.09, p = 0.006) in that maltreating mothers were lower on sensitive guidance. There was also an effect of RET on sensitive guidance at T3 (b = 0.45, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) and change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T4 (b = 0.49, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001) such that mothers in the intervention were higher on sensitive guidance at T3 and showed steeper improvement over time. Maltreatment was not associated with change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T4. Maternal depressive symptoms were not associated with sensitive guidance at T3 or change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T4. Sensitive guidance at T3 was associated with child maladjustment at T4 (b = -0.31, SE = 0.11, p = 0.004), but was not associated with change in child maladjustment from T1 to T4. Change in sensitive guidance was not associated with child maladjustment at T4 or change in child maladjustment from T1 to T4.

According to bias-corrected, resampled bootstraps results, there were two significant indirect effects. First, sensitive guidance at T3 mediated the relationship between RET and child maladjustment at T4 (CI 95%: -0.30, -0.04). Second, sensitive guidance at T3 mediated the relationship between maltreatment and child maladjustment at T4 (CI 95%: 0.02, 0.17). There were no other statistically significant indirect effects. Additionally, the longitudinal mediation model was re-run with the addition of child sex as a covariate on child maladjustment and the pattern of results was unchanged.

Discussion

The current study enhances the literature on the influence of parental emotion socialization on child maladjustment over time by examining the effects of an intervention designed to improve maternal emotion socialization behavior in the context of child maltreatment and maternal depressive symptoms. Our results provide experimental evidence for the role of maternal emotion socialization broadly, and of maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing about children’s emotional events, specifically, as important processes that influence child emotional development among maltreating families. Moreover, this study demonstrates that intervention-related improvement in maternal sensitive guidance mediates the effects of the RET intervention on reduced child maladjustment among maltreated children one year later, whereas poor sensitive guidance mediates the effects of maltreatment on higher child maladjustment. Direct negative effects of maternal depressive symptoms on subsequent child maladjustment one year later were also observed; however, maternal sensitive guidance did not mediate this association.

Child maltreatment significantly increases risk for child maladjustment and for psychopathology across the lifespan (Cicchetti & Toth, 2016). Impairments in positive caregiving behaviors are thought to be a key process linking child maltreatment to maladjustment (Toth et al., 2013; Valentino, 2017). The current study adds to our understanding of the specific parenting behaviors that influence child maladjustment by identifying poor emotion socialization, and maternal sensitive guidance, specifically, as explaining associations between maltreatment and child maladjustment one year later. These indirect effects align with cross-sectional work that identifies poor maternal emotion socialization as a mechanism that explains associations between maltreatment and child emotion regulation (Shipman et al., 2007), as well as longitudinal associations with child emotion regulation in the current sample (Speidel et al., 2020). This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has supported maternal sensitive guidance as a mechanism explaining how maltreatment may lead to child maladjustment, while also controlling for maternal depressive symptoms.

Moreover, the current study demonstrates that improved maternal sensitive guidance six-months following intervention (T3) is related to reductions in child maladjustment one year after the intervention (T4). Our experimental data coheres with and advances hypotheses about the salience of parent emotion socialization for supporting child emotional development that have been observed, primarily, from cross sectional or correlational longitudinal designs with low-risk samples (Morris et al., 2007). By randomly assigning maltreating mothers to the RET condition, where we trained mothers in sensitive guidance during reminiscing, or to a comparison condition, the current study provides important experimental evidence for how positive emotion socialization behavior supports child emotional development in a treated high-risk sample (i.e., maltreating families) while also highlighting how poor emotion socialization increases risk for child maladjustment among untreated maltreating families. Importantly maternal sensitive guidance at T3, but not change in sensitive guidance over time, was a significant mediator of the associations between RET and maltreatment with children’s maladjustment at T4. Our results, which indicated steep initial change in sensitive guidance from T1 to T2, followed by a slight decline and plateau suggest that the extent to which mothers retained their sensitive guidance skills at T3 was most relevant for predicting children’s maladjustment six months later.

Additionally, our results highlight both parental emotion socialization behaviors, broadly, and the RET intervention, specifically, as having important transdiagnostic implications for children’s emotional development. Child maladjustment during the preschool years is often observed as a precursor to the development of clinically significant internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Egger & Angold, 2006). Notably, we did not observe direct effects of maltreatment or RET on child adjustment. Instead, the significant indirect effects of maltreatment and RET on child maladjustment one year later through maternal sensitive guidance suggests that this emotion socialization parenting behavior is part of a developmental cascade, which can either increase risk for maladjustment when left untreated, or may be protective for maltreated children’s emotional health when enhanced through intervention. As such these results add to our understanding of the benefits of this intervention, which include improved emotion knowledge immediately after treatment (Valentino et al., 2019), steeper positive change in emotion regulation from baseline to six months after the intervention (Speidel et al., 2020), and improved physiological regulation one year after the intervention (Valentino et al., 2020). As a brief intervention that was designed to be delivered by paraprofessional staff, RET has much promise as a low-cost intervention that is associated with positive behavioral and biological outcomes for maltreated children, and has the potential for wide dissemination; the evaluation of RET in effectiveness trials will be an important next step towards that goal.

Consistent with our hypothesis and the broader literature on maternal depressive symptoms and risk for child maladjustment (Goodman et al., 2011), we found maternal depressive symptoms, measured at baseline, directly related to greater child maladjustment one year later. Contrary to hypotheses, this effect was not mediated by maternal sensitive guidance. Prior research has indicated that dysfunctional parenting behaviors mediate, at least in part, the association between maternal depressive symptoms and child adjustment (e.g., see review by Goodman & Garber, 2017) including parent sensitivity. However, in the current sample, maternal depressive symptoms were not related to maternal sensitive guidance or change in sensitive guidance over time. Though unexpected, our results are consistent with other research highlighting nonsignificant associations between maternal depressive symptoms and responses to child affect (e.g., Breaux et al., 2016). However, there are many other possibilities regarding parenting variables that may mediate the direct effects of maternal depressive symptoms on maladjustment. It is important to recognize that we did not randomize families into intervention conditions as a function of maternal depressive symptoms. As such, our test for the role of sensitive guidance as mediator of associations between maternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment was weaker than our test of sensitive guidance as mediator of associations between maltreatment and child maladjustment. Given the non-significant results, we can only conclude that sensitive guidance, as tested here, was not a significant mediating process for maternal depressive symptoms among maltreating and nonmaltreating families. Furthermore, in the context of elevated maternal depressive symptoms, there may be individual differences in how mothers engage in reminiscing and provide sensitive guidance during discussions of children’s past emotional events. Future person-centered, rather than variable-centered approaches to understanding profiles of maternal emotion socialization may be beneficial to enhance our understanding of how risk processes such as maternal depression and maltreatment affect maternal emotion socialization behaviors.

On the other hand, given that maternal depressive symptoms related directly to child maladjustment in a sample of maltreating mothers, the results underscore the significance of maternal depressive symptoms for child maladjustment in these families. That is, our results highlight the importance of attending to maternal psychological functioning to prevent the development of emotional and behavioral maladjustment among young children (Goodman & Garber, 2017). This may be especially relevant among mothers involved in the child welfare system, where high rates of depression are observed (Dolan et al., 2012). Among maltreating families where maternal depressive symptoms are high, it may be important to provide relational parenting interventions in combination with treatment to directly support maternal depressive symptoms as it appears that improving maternal sensitive guidance may not be a useful target for reducing the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on child adjustment. Supporting maternal well-being directly may be a central process for fostering resilience among children at risk for maladjustment (Luthar & Eisenberg, 2017). Moreover, additional risk factors associated with maltreating mothers merit exploration in future research (e.g., antisocial behavior, substance use).

Although the current study has several methodological strengths including minimal attrition in a longitudinal RCT design with repeated measurements, a number of limitations exist. Given the design of our RCT with two comparison groups (CS, NC), we have limited statistical power to evaluate more complex models such as considering interactions among maternal depressive symptoms, maltreatment and RET on these processes over time. For example, to further clarify the complex associations among maternal depressive symptoms and the RET intervention on child maladjustment, future research should evaluate whether maternal depressive symptoms at baseline (and/or other time points) may moderate the effect of RET on maternal sensitive guidance or on child maladjustment. Alternately, it is possible that secondary effects of RET may include improvement in maternal depressive symptoms over time. Improvements in maternal depressive symptoms following other family-based interventions have been shown to contribute to lower maladjustment among children, even after accounting for changes in positive parenting behavior (Shaw et al., 2009). Additionally, although our sample of ethnically diverse, low-income families expands our understanding of emotion socialization processes among families who are underrepresented in the literature, we did not evaluate ethnicity, or other demographic factors, as a moderator of associations between emotion socialization and child adjustment.

Another limitation is our reliance on maternal report for child maladjustment symptoms over time. Shared method variance could have inflated associations between maternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment. Also mothers with elevated depressive symptoms may have more negative interpretations of their children’s behavior, though evidence for the depression-distortion hypothesis as it relates to maternal reports of child behavior are equivocal, with recent research finding little empirical support for biases in maternal report of youth behavior as a function of psychopathology (Olino et al., 2020). Regardless, in future research, it will be important to incorporate children’s own perspectives, as well as the perspectives of others such as teachers, to evaluate child maladjustment more comprehensively. Finally, we examined maternal depressive symptoms, but, as noted above, we did not include other forms of maternal psychopathology such as antisocial behavior or substance use that have been shown to be related to emotion socialization practices and child socioemotional outcomes (e.g., Godleski et al., 2020), and may be relevant for further understanding these processes among maltreating families.

Overall, our results are consistent with findings from other emotion socialization programs whereby improvements have been demonstrated in parent emotion socialization as well as in children’s emotional adjustment (e.g., Havighurst et al., 2009, 2010, 2015; Kehoe et al., 2014). Furthermore, our work advances the literature by directly testing our hypothesized mechanism of effects, and by showing how maternal sensitive guidance following intervention can explain improvements in child maladjustment one year later. Although the RET intervention is similar to other emotion socialization interventions by focusing on the enhancement of caregiver support and validation of child emotion (Havighurst et al., 2009; Katz et al., 2020), RET is unique in its specific focus on maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing. As such, our findings add to accumulating evidence for maternal sensitive guidance as a key aspect of maternal caregiving and emotion socialization during early childhood that may be enhanced following brief training, and in turn, may reduce risk for maladjustment among maltreated children.

References

Barnett, D., Manly, J. T., & Cicchetti, D. (1993). Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In D. Cicchetti & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Advances in applied developmental psychology: Child abuse, child development and social policy (pp. 7–73). Ablex.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238.

Breaux, R. P., Harvey, E. A., & Lugo-Candelas, C. I. (2016). The role of parent psychopathology in emotion socialization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(4), 731–743.

Cicchetti, D., & Gunnar, M. R. (2008). Integrating biological measures into the design and evaluation of preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 737–743.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2016). Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective. In D. Cicchetti (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology (Vol. 3, pp. 457–512). Wiley.

Cicchetti, D., & Valentino, K. (2006). An Ecological Transactional Perspective on Child Maltreatment: Failure of the Average Expectable Environment and Its Influence Upon Child Development. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental Psychopathology (2nd ed.): Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, Vol. 3 (pp. 129–201). NY, New York: Wiley.

Cunningham, J., Kliewer, W., & Garner, P. (2009). Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 261–283.

Dolan, M., Casanueva, C., Smith, K., Lloyd, S., & Ringeisen, H. (2012). NSCAW II Wave 2 Report: Caregiver Health and Services. OPRE Report #2012–58, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (4th ed.). NCS Pearson.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337.

Eisenberg, N. (2020). Findings, issues, and new directions for research on emotion socialization. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 664–670.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., & Spinrad, T. L. (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 241–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

England-Mason, G., & Gonzalez, A. (2020). Intervening to shape children’s emotion regulation: A review of emotion socialization parenting programs for young children. Emotion, 20(1), 98–104.

Fivush, R., Haden, C. A., & Reese, E. (2006). Elaborating on elaborations: Role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development, 77, 1568–1588.

Gilliom, M., & Shaw, D. S. (2004). Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 313–333.

Godleski, S. A., Eiden, R. D., Shisler, S., & Livingston, J. A. (2020). Parent socialization of emotion in a high risk sample. Developmental Psychology, 56, 489–502.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337–1345.

Goodman, S.H., & Garber, J. (2017). Evidence‐Based Interventions for Depressed Mothers and Their Young Children. Child Development, 88, 368-377. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12732

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1997). Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Havighurst, S. S., Kehoe, C. E., & Harley, A. E. (2015). Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 148–158.

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., & Prior, M. R. (2009). Tuning in to kids: An emotion-focused parenting program—initial findings from a community trial. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 1008–1023. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20345

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Prior, M. R., & Kehoe, C. (2010). Tuning in to kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children- findings from a community trail. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1342–1350.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Johnson, A. M., Hawes, D. J., Eisenberg, N., Kohlhoff, J., & Dudeney, J. (2017). Emotion socialization and child conduct problems: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.001

Katz, L. F., Gurtovenko, K., Maliken, A., Stettler, N., Kawamura, J., & Fladeboe, K. (2020). An emotion coaching parenting intervention for families exposed to intimate partner violence. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 638.

Kehoe, C. E., Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. E. (2014). Tuning in to teens: Improving parent emotion socialization to reduce youth internalizing difficulties. Social Development, 23(2), 413–431.

Klimes-Dougan, B., & Zeman, J. (2007). Introduction to the special issue of Social Development: Emotion Socialization in Childhood and Adolescence. Social Development, 16, 203–209.

Kochanska, G., Kuczynski, L., Radke-Yarrow, M., & Welsh, J. D. (1987). Resolutions of control episodes between well and affectively ill mothers and their young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15(3), 441–456.

Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., & Getzler-Yosef, R. (2008). Shaping children's internal working models through mother–child dialogues: the importance of resolving past maternal trauma. Attachment & Human Development,10, 465-483.

Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., Haimovich, Z., & Etzion-Carasso, A. (2003). Autobiographical Emotional Event Dialogues: Classification and scoring system. Unpublished measure.

Laible, D., Panfile Murphy, T., & Augustine, M. (2013). Constructing emotional and relational understanding: The role of mother–child reminiscing about negatively valenced events. Social Development, 22(2), 300–318.

Little, R. J. A. (1998). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202.

Lunkenheimer, E. S., Shields, A. M., & Cortina, K. S. (2007). Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development, 16, 232–248.

Luthar, S. S., & Eisenberg, N. (2017). Resilient adaptation among at-risk children: Harnessing science toward maximizing salutary environments. Child Development, 88, 337–349.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

McArdle, J. J., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2014). Longitudinal data analysis using structural equation models. American Psychological Association.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16, 361–388.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus (Version 8) [Computer software]. Los Angeles.

Nelson, K., & Fivush, R. (2004). The emergence of autobiographical memory: A social cultural developmental theory. Psychological Review, 111, 486. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.486

Olino, T., Guerra-Guzman, K., Hayden, E.P., & Klein, D.N. (2020). Evaluating maternal psychopathology biases in reports of child temperament: An investigation of measurement invariance. Psychological Assessment, online ahead of publication.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Salmon, K., Dadds, M. R., Allen, J., & Hawes, D. J. (2009). Can emotional language skills be taught during parent training for conduct problem children? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40, 485–498.

Salmon, K., & Reese, E. (2016). The benefits of reminiscing with young children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(4), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416655100

Sanders, W., Zeman, J., Poon, J., & Miller, R. (2015). Child regulation of negative emotions and depressive symptoms: The moderating role of parental emotion socialization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9850-y

Shaw, D. S., Connell, A., Dishion, T. J., Wilson, M. N., & Gardner, F. (2009). Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 417–439.

Shipman, K. L., Schneider, R., Fitzgerald, M. M., Sims, C., Swisher, L., & Edwards, A. (2007). Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and non-maltreating families: Implications for children’s emotion regulation. Social Development, 16, 268–285.

Speidel, R., Wang, L., Cummings, E. M., & Valentino, K. (2020). Longitudinal Pathways of Family Influence on Child Self-Regulation: The Roles of Positive Parenting, Positive Family Expressiveness, and Maternal Sensitive Guidance in the Context of Child Maltreatment. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 608–622.

Speidel, R., Valentino, K., McDonnell, C.G., Cummings, E.M., & Fondren, K. (2019). Maternal Sensitive Guidance During Reminiscing in the Context of Child Maltreatment: Implications for Child Regulatory Processes. Developmental Psychology, 55, 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000623

Thompson, R. A., & Meyer, S. (2007). Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. Handbook of emotion regulation, 249, 249-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413519014

Toth, S. L., Gravener-Davis, J. A., Guild, D. J., & Cicchetti, D. (2013). Relational interventions for child maltreatment: Past, present, and future perspectives. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1601–1617.

Valentino, K. (2017). Relational Interventions for Maltreated Children. Child Development, 88, 359–367.

Valentino, K., Cummings, E. M., Borkowski, J., Hibel, L. C., Lefever, J., & Lawson, M. (2019). Efficacy of a Reminiscing and Emotion Training Intervention on Maltreating Families with Preschool Aged Children. Developmental Psychology, 55(11), 2365–2378.

Valentino, K., Comas, M., Nuttall, A. K., & Thomas, T. (2013). Training maltreating parents in elaborative and emotion-rich reminiscing with their preschool-aged children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 585–595.

Valentino, K., Hibel, L.C., Cummings, E.M., Comas, M., Nuttall, A.K., & McDonnell, C. (2015). Maternal elaborative reminiscing mediates the effect of child maltreatment on behavioral and physiological functioning. Development & Psychopathology, 27, 1515-1527. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415000917

Valentino, K., Hibel, L.C., Speidel, R., Fondren, K., & Ugarte, E. (2020). The effects of maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and Reminiscing and Emotion Training on children’s diurnal cortisol over time. Development & Psychopathology.

Valentino, K., McDonnell, C. G., Comas, M., & Nuttall, A. K. (2018). Preschoolers’ autobiographical memory specificity relates to their emotional adjustment. Journal of Cognition and Development, 19(1), 47–64.

Van Bergen, P., Salmon, K., Dadds, M. R., & Allen, J. (2009). The effects of mother training in emotion-rich, elaborative reminiscing on children’s shared recall and emotion knowledge. Journal of Cognition and Development, 10, 162–187.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Heidi Miller and the H2H2 project staff for their invaluable assistance with this project. Additionally, we are grateful to the children and families that participated in this study and the Department of Child Services of St. Joseph County. This research was supported by grants R01 HD071933 and R01HD091235 to K. Valentino. A full list of publications supported by these grants can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/myncbi/kristin.valentino.1/bibliography/public/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The data for the current study are part of a larger project, approved by the University of Notre Dame Institutional Review Board and granted approval number 12-06-376.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent and signed release forms granting access to their DCS records.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valentino, K., Speidel, R., Fondren, K. et al. Longitudinal Effects of Reminiscing and Emotion Training on Child Maladjustment in the Context of Maltreatment and Maternal Depressive Symptoms. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 50, 13–25 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00794-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00794-0