Abstract

This investigation answers and amplifies calls to model the transdiagnostic structure of psychopathology in clinical samples of early adolescents and using stringent psychometric criteria. In 162 clinically referred, clinically evaluated 11–13-year-olds, we compared a correlated two-factor model, containing latent internalizing and externalizing factors, to a bifactor model, which added a transdiagnostic general factor. We also evaluated the bifactor model psychometrically, including criterion validity with broad indicators of psychosocial functioning. In doing so, we compared alternative approaches to defining and interpreting criterion validity: a recently proposed incremental definition based on amounts of variance in criterion factors explained, and the more typical definition based on the presence of conceptually meaningful relationships. While traditional fit statistics favored the bifactor model as expected, psychometric analyses added important nuance. Despite moderate reliability, the general factor was not fully transdiagnostic (i.e., was not informed by several externalizing scores), and was partially redundant with internalizing scores. Approaches to criterion validity yielded opposing results. Compared to the correlated two-factor model, the bifactor model redistributed, without incrementally increasing, the total variance explained in criterion indicators of psychosocial functioning. Yet, the bifactor model did improve the precision of clinically important relationships to psychosocial functioning, raising questions about meaningful tests of bifactor psychopathology models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Understanding the structure of psychopathology, including features that are shared across disorders versus those that are unique to specific pathologies, bears directly on treatment and prevention. Data-driven approaches play a critical role by revealing common sources of variance shared by clusters of pathologies. Initially, quantitative studies on the structure of psychopathology focused on adult samples. Extensions into youth samples have made strides toward identifying common underlying pathogenic processes at play during high-risk periods preceding adult psychopathology (e.g., Haltigan et al. 2018). However, as we discuss below, adolescent structural studies have made methodological trade-offs limiting their relevance to higher levels of clinical dysfunction. We addressed the remaining need for structural studies in clinically referred, clinically evaluated samples with enough psychiatric acuity to allow modeling of clinically significant, transdiagnostic dysfunction in youth. This study also applied recent recommendations regarding psychometric interrogation of bifactor models (Bonifay et al. 2017). In doing so, it both addresses recent questions (Watts et al. 2019) and raises new ones about appropriate tests of criterion validity for bifactor models of psychopathology.

Transdiagnostic Approaches and the Principal Role of Emotion Dysregulation

Transdiagnostic approaches, which articulate common processes across mental disorders, have helped explain high rates of comorbidity (e.g., Caspi and Moffitt 2018; Kessler et al. 2005) and informed streamlined interventions targeting multiple psychopathologies simultaneously (Barlow et al. 2017). The major mental disorders converge reliably on at least two dimensions: internalizing psychopathologies (i.e., depression and anxiety disorders), and externalizing psychopathologies (i.e., those involving aggressive or disruptive behavior; Achenbach and Edelbrock 1981; Krueger and Markon 2006). The newest accounts theorize that these dimensions are better understood as sharing further common liabilities (e.g., Carver et al. 2017; DeYoung and Krueger 2018; Kotov et al. 2018). In adult—and more recently, youth—samples, statistical evidence points to the existence of a latent general psychopathology factor (the ‘p factor’), explaining a substantial portion of variance in disorders on internalizing and externalizing dimensions (e.g., Afzali et al. 2018; Caspi et al. 2014; Laceulle et al. 2015; Lahey et al. 2012; Snyder et al. 2017). Existence of a general psychopathology factor is compatible with the relatively general effects of genetic (Lahey et al. 2011; Pettersson et al. 2016), and neurobiological vulnerabilities (Sprooten et al. 2017).

Playing a principal role in transdiagnostic psychopathology is emotion regulation, a broad set of controlled and automatic processes involved in “monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one’s goals” (Thompson 1994, pp. 27–28). Emotion dysregulation, or difficulties in emotion regulation, is common to many psychopathologies (Aldao et al. 2010; Kring and Sloan 2009) and helps account for their rates of co-occurrence (e.g., McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema 2011; Weissman et al. 2019). Structural studies show associations between a general psychopathology factor and aspects of emotion dysregulation, including compromised executive functioning and effortful control (Martel et al. 2017; Snyder et al. 2015), emotional reactivity and trait rumination (Weissman et al. 2019), and negative affect (Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2016; Snyder et al. 2017).

The Structure of Psychopathology in Early Adolescence: Objectives for Research

The structure of psychopathology during its emergence may hold clues for identifying true boundaries between pathological processes (Murray et al. 2016). For instance, if a general factor is weak or nonexistent in younger samples, it would cast doubt on the theories postulating broad underlying liability factors, instead suggesting developmental drift toward increasing comorbidity and disorder-generalization in adulthood (e.g., via dynamic mutualism; McElroy et al. 2018; Murray et al. 2016; or via stress generation, Conway et al. 2012). By contrast, a strong general factor in early adolescents would be consistent with theories positing broad initial latent vulnerabilities, which may become differentiated into distinct syndromes over time (p-differentiation; McElroy et al. 2018; Murray et al. 2016). To speak to such issues in etiology, structural studies in younger samples are essential, especially in early adolescence, the period when emotion dysregulation increases (Kovacs et al. 2019) and psychopathology commonly onsets (Beesdo et al. 2010; Kessler et al. 2005). Researchers have begun to extend structural investigations from adults to older adolescents (e.g., Haltigan et al. 2018; Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2016; Laceulle et al. 2015; Snyder et al. 2017), and increasingly, to children and younger adolescents (Afzali et al. 2018; Snyder et al. 2017; McElroy et al. 2018; Martel et al. 2017; Murray et al. 2016; Patalay et al. 2015). These studies have generally supported both the existence, and relative stability of “p” during adolescence.

Need for Structural Assessment in Clinically Referred, Clinically Evaluated Samples

The existing structural studies such as referenced above have covered important ground by using large, community samples, many numbering in the thousands, to estimate a general psychopathology factor in the general population of children and adolescents. The large scale of those samples lends reliability to their estimates. At the same time, to further explain psychopathology and inform prevention, we (and others; e.g., Haltigan et al. 2018) believe there is also a need to assess the structure of psychopathology in clinical youth samples.

We see several advantages to using clinical samples to study psychopathology structure. For one, this strategy ensures larger variance in the clinical phenomena of interest, which may be needed to detect more nuanced patterning of psychopathology dimensions (e.g., Keenan et al. 2010). In the context of a general community sample, elevations on clinical symptoms might have inflated appearance of sharing common variance due to the relatively starker contrast with less impaired peers. Furthermore, clinical samples may differ from community samples in more than simple degree or extremity of symptoms. Even the very structure of personality differs between normal and pathological ranges (Morey et al. 2015; Wright et al. 2012) and between community and clinical samples (Hallquist and Pilkonis 2012), and these structural differences may be explained by the added presence of psychosocial impairment in clinical samples (Morey et al. 2020). For both of these reasons, focusing on clinically impaired adolescents increases the potential to reveal otherwise obscured fault lines between clusters of symptom variance in this group.

Structural studies that are or will become longitudinal may wish to consider a complementary strategy to maximize both cross-sectional and ongoing variance in clinical phenomena. That is, is to oversample on a robust predictor of the target phenomena (e.g., Keenan et al. 2010). Given the centrality of emotion dysregulation to transdiagnostic conceptualizations and to the general psychopathology factor (Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2016; Kring and Sloan 2009; Martel et al. 2017; McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema 2011; Sharp et al. 2015; Snyder et al. 2015; Weissman et al. 2019), it makes sense to select emotion dysregulation as the dimension on which to oversample. This could help provide the variance needed to ‘zoom in’ on the patterning of psychopathology as it is expressed in clinically significant ranges.

In addition to using clinical and dysregulated samples, using clinician ratings could complement findings of previous structural studies, which relied largely on self-report. Self-report is vulnerable to several biases, such as from difficulties in self-awareness, response styles, and general distress, which reduce the specificity of constructs and inflate the intercorrelations between them. Statistically, such biases would masquerade as common variance shared by all assessed indicators (Williams and McGonagle 2016), looking much like a p-factor. Using semi-structured clinical interviews minimizes such biases because clinicians use established scoring criteria and can integrate both adolescent and parent reports. Clinical evaluation could thus improve detection of differentiation in psychopathology dimensions and increase confidence in a general factor if one emerges. To date, we know of no structural study using clinician-administered assessment with clinically referred adolescents. Haltigan et al. (2018) found a general factor in a clinical sample of adolescents presenting at a mental health hospital, but using questionnaires. Martel et al. (2017) used a clinical interview with adolescents; but the sample was non-clinical, and the interview was computer-administered, with scores generated offsite by clinicians with no participant interaction. For feasibility reasons, structural studies in clinically referred, clinically evaluated youth would necessarily have smaller samples, and by extension, would provide less reliable and less generalizable estimates. At the same time, they could serve as the basis for meta-analytic investigations of measurement invariance across diverse clinical populations, and would be invaluable for their ability to reveal patterns of psychopathology at significant levels of acuity early in the course of impairment.

Need for Statistical Interrogation of Bifactor Solutions

Models incorporating a general factor, bifactor models, benefit from built-in statistical advantages, because they allow variance in each psychopathology indicator to be explained by two latent factors: the indicator’s “specific” factor (e.g., internalizing or externalizing), and the transdiagnostic common factor (Rodriguez et al. 2016). Because of this, bifactor models have been criticized for overfitting data (Bonifay et al. 2017; Greene et al. 2019; Markon 2019; Reise et al. 2016; Watts et al. 2019), capturing statistical artifact with “p” perhaps without real clinical meaning (Caspi and Moffitt 2018). Current recommendations emphasize two avenues for more critical interrogation of the general factor. First, there is a strong call (Bonifay et al. 2017; Greene et al. 2019) to apply a set of reliability tests available to rigorously interrogate bifactor model solutions (Rodriguez et al. 2016; Hammer and Toland 2016). Second, critical evaluation at the construct level is essential in order to determine the potential meaning and utility of a general psychopathology factor (Caspi and Moffitt 2018). Several studies have evaluated correlations between the ‘p-factor’ and indicators of criterion validity, including general cognitive and affective vulnerabilities (Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2016; Snyder et al. 2017; Martel et al. 2017), general risk factors (e.g., familial psychopathology; Martel et al. 2017), and broad indices of clinical functioning like self-harm/suicidality and psychosocial functioning (Haltigan et al. 2018; Pettersson et al. 2018; Patalay et al. 2015).

Watts et al. (2019) argued that such correlations with criterion indicators are not strong clues to the criterion validity of a general psychopathology factor. Rather, they urged comparison of the bifactor model to its predecessor, the correlated factor model, which posits “specific” (e.g., internalizing, externalizing) dimensions without a general factor. To demonstrate criterion validity, they argue, the bifactor model must account for additional variance in external indicators, compared to the correlated factor model; if it cannot, then a bifactor model has merely redistributed the variance already explained by prior theories. This standard heavily prioritizes incremental validity in the assessment of criterion validity, arguably conflating them. Alternatively, we suggest that even if a bifactor model fails to expand explained variance in external indicators, “mere” redistribution of variance may still be fruitful. Redistributing explained variance may be useful if it improves the precision of conceptualizations involving criterion indicators and sheds clinically meaningful light on dimensions of psychopathology.

Current Study

We assessed the structure of psychopathology in a clinically referred, early adolescent sample with thorough representation of emotion dysregulation and clinical assessment. We had two goals: (1) to compare the quantitative fit of alternative models suggested in the literature (correlated two-factor, bifactor) in order to test the hypothesis that a bifactor model would best describe the sample’s psychopathology; and (2) to use current best-practice approaches to interrogate the psychometric properties of the bifactor solution by evaluating: (a) recommended psychometric indices (Bonifay et al. 2017), and (b) criterion validity of the bifactor model with respect to broad indices of clinical functioning, using both the recently proposed incrementally focused standard (Watts et al. 2019) and our alternative, conceptually focused standard. To test criterion validity meaningfully and compare approaches, we needed transdiagnostically relevant criteria representing important real-world domains of functioning. Psychosocial competence and suicide risk were selected as two such clinically meaningful, broadly relevant indices.

Method

Sample

Participants were 162 clinically referred adolescents aged 11–13 (Mage = 12.03 years, SD = 0.92). Half of adolescents (47%) were female, and 60% of youth identified as racial/ethnic minorities (41% Black; 16.7% biracial; 6% American Indian/Alaskan Native; 4% Hispanic). Youth and their primary caregivers were recruited from pediatric primary care and ambulatory psychiatric treatment clinics within a large, urban, academic hospital-based setting. To capture a transdiagnostic sample of youth with a variety of internalizing and externalizing disorders, early adolescents were oversampled for emotion dysregulation based on the 6-item (4-point scale-rated) Affective Instability subscale from the Personality Assessment Inventory-Adolescent version (M = 13.05, SD = 2.90; scores>11 indicating clinical significance; Morey 2007). For eligibility, adolescents needed to be currently receiving psychiatric or behavioral treatment for any mood or behavior problem, have IQ > =70 (based on Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2007), and be free of organic neurological medical conditions and current manic or psychotic episode. Most (88%) of participating caregivers were biological mothers (Mage=39.84; SD = 7.25; 94% female; 48% racial/ethnic minority). Caregivers reported having M = 3.24 children (SD = 1.68), and 49% reported living with their romantic partners. One third (66%) of households reported not having any employed caregivers. Annual household income was <$20,000 for 31%, and between $20,000 and $39,000 for 19% of households.

Procedure

Adolescents and caregivers completed a laboratory visit as part of a larger study, during which adolescent psychopathology was assessed by trained interviewers using established semi-structured interviews within a larger protocol. Questionnaires and 4-day ecological momentary assessment (EMA) completed separately by adolescents and caregivers after the laboratory session provided select additional variables for analysis. Procedures were approved by the Human Research Protection Office and conducted in an ethical manner. Adolescent and caregiver each provided written informed consent, and each was compensated.

Measures

Clinical Interviews

Two instruments provided clinical severity scores. The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS-PL) is a semi-structured interview for youth aged 6–18 and their caregivers to assess the presence and severity of affective and other child psychiatric disorders (Kaufman et al. 1997). Questions begin with a screen interview that covers all diagnostic categories, then continue using specific diagnostic supplements as indicated when screen thresholds are met. In this study, when no diagnostic supplement was indicated, the screener alone provided severity ratings. Scores reflect lifetime disorder severity as the sum of clinician ratings for each symptom assessed (0 = absent; 1 = subthreshold; 2 = threshold) based on DSM-5 criteria. The Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder (CI-BPD) is a semi-structured interview for diagnosing borderline personality disorder adapted from the adult assessment of DSM-IV personality disorders and adjusted for adolescents (Zanarini 2003). Scores reflect past-2-years severity as the sum of clinician ratings for symptoms (0 = absent; 1 = subthreshold; 2 = threshold). To minimize participant burden, youth and caregivers were interviewed simultaneously by two clinicians in separate rooms, and for each disorder the maximum severity score obtained via either youth or caregiver interview was utilized in the current analyses. Ten percent of interviews were double-scored from video tape, showing strong inter-rater reliability using a two-way model with consistency type (avg ICC = .88).

Criterion Validity Measures. Psychosocial functioning

The Competence Scales (Activities, Social, Academic Performance) were used from the Childhood Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report (YSR) to represent adolescents’ psychosocial functioning (Achenbach 1991). The CBCL and YSR collect parent- and adolescent reports on identical behavioral items and are psychometrically reliable and normed for clinically referred youth (6–18 yrs. CBCL; 11–18 yrs. YSR). Minor scoring modifications were made to represent the present data appropriately. Data inspection showed that participants often listed activities multiple times (e.g., “basketball” listed under sports, hobbies, and clubs); therefore, count-based sub-scores were omitted to avoid overinflating competence calculations. Also, Academic Performance was computed identically for both respondents. Psychosocial competence was best represented by two correlated latent factors reflecting adolescent and parent appraisals, respectively, with each factor informed by three competence domains, and residuals of parallel scores between reporters correlated, χ2(5) = 4.06, p = .541, RMSEA = .00 [.00,.10], CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.03.Footnote 1

Suicide Risk Status

Although all adolescents can be considered at risk for suicide (Curtin and Heron 2019), those with a history of suicidal or self-harm-related ideation or behavior are at elevated risk (Ribeiro et al. 2016). We created a dichotomous index of elevated risk reflecting history of any suicidal or self-harm-related ideation or behavior, per the adolescent or caregiver report on any measure in our battery (details in Supplement B). This identified 99 (61.1%) adolescents at elevated suicide risk (n = 68 by adolescent report; n = 89 by parent parent).

Analytic Plan

Data were inspected in SPSS v.24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), and disorders with low prevalence in the sample were omitted from further analyses, based on skewed sample distribution (skewness and kurtosis with absolute value >2). Remaining analyses used the full information maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus (Version 8.0.0.1; Muthén and Muthén 1998–2011) and proceeded in two phases. First, we compared the correlated two-factor and bifactor models using adolescents’ clinical severity scores. The correlated two-factor model was constructed with latent internalizing and externalizing factors that were allowed to correlate. Overanxious disorder (GAD), social phobia (SOC), separation anxiety (SEP), and depression (DEP) were expected to load on the internalizing factor; oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were expected to load on the externalizing factor. Given known comorbidities (Bailey and Finn 2019; Eaton et al. 2011; Jopling et al. 2016), BPD was cross-loaded on both factors. Debate on the status of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) as a behavioral vs. mood disorder (e.g., Althoff et al. 2016; Stringaris et al. 2018) led us to consider whether DMDD would also cross load; however, because we observed stronger correlations with behavioral disorders (Table 2), we started by loading DMDD on the externalizing factor only, before considering model respecifications. To construct a true bifactor model, the internalizing and externalizing factors in that model were not allowed to correlate, and every severity score was also loaded onto an additional orthogonal latent factor representing general psychopathology. The fit of each model was assessed by examining conventional indicators of good model fit: non-significant χ2 likelihood ratio test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > = .95, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .05; 90% confidence intervals ideally containing zero (McDonald and Ho 2002). Models were compared using chi-square difference tests (Δχ2).

Given its statistical advantage (Bonifay et al. 2017), we expected the bifactor model to show the strongest fit, so we anticipated the need to interrogate its psychometric properties in two ways. First, we examined model-based reliability and related indices using available metrics (Rodriguez et al. 2016). Second, we explored criterion validity with respect to broad indices of clinical functioning: psychosocial functioning, and the composite index of suicide risk status, adjusted for related demographic characteristics. In doing so, we compared the variance in external criteria explained by the bifactor model versus the correlated factor model (Watts et al. 2019). To conduct the comparison, it was necessary to regress the criterion validity variables not only on the demographic-adjusted bifactor model, but also on a comparably adjusted, correlated two-factor model. This made it possible to examine the bifactor model for evidence of conceptual precision gained in the relationships between psychopathology and external criteria, as an alternative to Watts et al.’ (2019) incremental heuristic for criterion validity.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptives and bivariate correlations among severity scores appear in Table 1 (sample clinical characteristics in Supplement A). Expected patterns emerged, with internalizing-type severities intercorrelated, externalizing-type severities intercorrelated, and DMDD and BPD severities correlated with most disorder severities in both groups. Gender and minority status correlated with many variables.

Alternative Structural Models of Psychopathology

Correlated Two-Factor Model

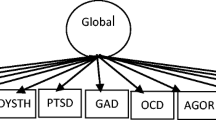

Initial fit indices revealed non-optimal fit, χ2(25) = 60.73, p < .001; RMSEA = .09 [.06,.12], CFI = .89, TLI = .84. Discrepancies between observed and model-implied loadings suggested cross-loading DMDD on the internalizing factor, which improved fit significantly, χ2(24) = 48.59, p = .002, RMSEA = .08 [.05,.11], CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.89, Δχ2(1) = 12.14, p < .001. Further allowing depression to correlate with BPD improved fit again, χ2(23) = 36.30, p = .039, RMSEA = .06 [.01,.10], CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, Δχ2(1) = 12.29, p < .001 (Fig. 1, Panel A; Supplement C). The internalizing and externalizing factors were characterized most strongly by GAD and ODD, respectively. Cross-loadings (BPD and DMDD) were significant.

Schematic illustration of final correlated two-factor (A) and bifactor (B) models. Factor loadings and correlation coefficients are standardized betas, boldfaced to indicate p < .05 (for full model coefficients, see Supplement C). INT = internalizing psychopathology; EXT = externalizing psychopathology; GEN = general psychopathology; GAD = overanxious disorder; SOC = social phobia; SEP = separation anxiety disorder; DEP = depression; DMDD = disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; BPD = borderline personality disorder; ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder

Bifactor Model and Model Comparison

The bifactor model was initially constructed with internalizing and externalizing factors identical to the final two-factor model, with an additional general factor informed by all nine severity scores (Fig. 1, Panel B; also Supplement C). For the model to converge and to produce an interpretable solution, two modifications were necessary: we had to remove BPD from the internalizing factor, suggesting that participants’ BPD did not have uniquely internalizing features, and fix the residual variances of BPD and GAD to zero, suggesting that the model explained all the variance in these disorders. This bifactor model fit the data well, χ2(19) = 20.09, p = .389, RMSEA = .02 [.00,.07], CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, and significantly better than the best two-factor model, Δχ2(4) = 16.21, p < .005.

As a final test to rule out the self-sufficiency of a general factor, all 9 severity indicators were loaded on one factor, which could not be adequately fitted to the data and was rejected.Footnote 2

Psychometric Properties of the Bifactor Model

Reliability and Related Indices for Bifactor Models

Values and interpretive guidelines for ancillary psychometric analyses for bifactor models are in Table 2 (see also Hammer and Toland 2016; Rodriguez et al. 2016). Overall, model-based reliability (omega, omega hierarchical, omega hierarchical subscale) indicated that the bifactor model accounted for over three-quarters of the total common variance in psychopathology severity, about one third of which was due to the general factor. The variance in psychopathology explained by the general factor tended to overlap with the variance explained by the specific factors (ωHS < .5), such that the internalizing factor explained the least unique variance, whereas the externalizing factor was somewhat more independent. Construct replicability (coefficient H) was highest for the general factor, followed by the externalizing factor, suggesting these factors were represented best by the observed indicators. Explained common variance (ECV), which ignores error-related variance, was divided among all three factors, consistent with neither a fully unidimensional, nor a two-factor solution (i.e., consistent with a bifactor solution). Item explained common variance (I-ECV) indicated that most externalizing indicators (ADHD, CD, ODD, and the externalizing portion of DMDD) and one internalizing indicator (GAD) were virtually unexplained by the general factor. By contrast, BPD and depression were explained mostly by the general factor, and the remainder of the indicators (SOC, SEP, and the internalizing portion of DMDD) reflected a balance of variance explained by internalizing and the general factor. The percent uncontaminated variance (PUC) suggested the earlier indices (ω and ECV) were relatively unbiased. In sum, the general factor was nonnegligible but also not fully transdiagnostic, and there were notable strengths in the internalizing and externalizing factors.

Criterion Validity

Regressing the bifactor model on criterion variables, adjusted for gender and minority status, produced adequate fit, χ2(104) = 126.34, p = .067, RMSEA = .04 [.00,.06], CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95. As shown in Fig. 2 (also Supplements E, F), externalizing and internalizing factors were associated with lower parent-rated psychosocial competence, while the general factor was associated with elevated suicide risk.Footnote 3 Regressing the correlated two-factor model on criterion variables, adjusted for gender and minority race, produced poor fit, χ2(113) = 180.52, p < .001, RMSEA = .06 [.04,.08], CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.85. Two-factor externalizing was associated with lower psychosocial competence, and internalizing and externalizing with suicide risk. The similarity of light and dark grey bars and standardized error margins (Fig. 2, Panel A) show that the variance explained in psychosocial functioning indicators did not differ between models. Yet, as evident in the discrepancy of significant regression pathways (Panel B), the bifactor model altered the pattern of associations, so that association with suicide risk became isolated to the general factor, and impaired psychosocial competence emerged in connection with internalizing—not just externalizing—psychopathology.

Alternative representations of criterion validity: (A) variances explained in psychosocial functioning indicators by the correlated two-factor and bifactor models (following Watts & Waldman, 2019); (B) significant regression paths emerging between psychosocial functioning indicators and the bifactor model (top) vs. correlated two-factor model (bottom). Panel A: Error bars represent standard errors. Variances were drawn from criterion validity analyses corresponding with models in Panel A of this figure (see also Supplements E and F). Panel B: Dashed lines represent non-significant paths (p > = .05). PSYC-A = psychosocial competence, adolescent-rated; PSYC-P = psychosocial competence, parent-rated; Suicide = elevated suicide risk; INT = internalizing psychopathology; EXT = externalizing psychopathology; GEN = general psychopathology. Not pictured: adjustments for gender and minority race, observed indicators of latent factors, latent factor correlations, and latent factor variances (which were fixed to one); full models are in Supplements E and F. *p < .05. **p < .001. ***p < .001

Discussion

In a sample of clinically referred, emotionally dysregulated early adolescents, we evaluated statistical evidence for the presence of transdiagnostic processes during this high-risk period. Fit statistics favored the bifactor model, but this was expected mathematically (Bonifay et al. 2017; Caspi and Moffitt 2018; Markon 2019). To more meaningfully evaluate the bifactor model, we conducted several psychometric tests (Rodriguez et al. 2016; Hammer and Toland 2016), which revealed a nuanced picture of an only partially transdiagnostic general factor. Findings provide a glimpse of the possible structure of psychopathology in clinically impaired early adolescents and raise questions about methods in structural psychopathology research.

The Bifactor Model Solution: Modest Strength and Implications for Psychopathology

Psychometric description of the final bifactor model revealed some strengths of the model and its general factor. The entire model accounted for over 75% of all symptom variance, and the general factor accounted for a nontrivial one third of this explained variance. Among all three factors, the general factor had the highest construct replicability, indicating that it was well characterized by its constituent indicators. The general factor explained the majority of modeled variance in BPD and depression, suggesting perhaps common variance related to emotion dysregulation; it also explained significant portions of the modeled variance of separation anxiety, social anxiety, and the internalizing portion of DMDD. This result echoes findings in the general population relating a general psychopathology factor to deficits in emotion regulation (e.g., Martel et al. 2017; Snyder et al. 2017; Weissman et al. 2019), and further suggests that in clinically impaired 11–13-year-olds, common variance in psychopathology manifests primarily as mood disorder. Future studies could use experimental tasks to identify emotional processing impairments characterizing the general factor in clinically referred adolescents. It may be fruitful to investigate whether general psychopathology variance in early adolescence may reflect self-other relational dysfunction, given that the indicators loading on the general factor (BPD, depression, social anxiety, separation anxiety) can all be conceptualized in this way (e.g., Bender and Skodol 2007; Berenson et al. 2009; Prinstein et al. 2005).

At the same time, notable portions of both internalizing and externalizing symptom variance were explained better by specific subfactors than by the general factor. The internalizing factor independently accounted for most modeled variance in GAD (92%) and social anxiety, and the non-trivial portions of separation anxiety, DMDD, and depression (31%). Others have found similarly that the internalizing factor overlaps somewhat more than other subfactors with a general psychopathology factor (e.g., Laceulle et al. 2015). Given the near purity of GAD as an internalizing indicator here, we interpret the present internalizing factor as reflecting the sample’s maladaptive anxiety-related processing (e.g., fear, worry, inhibition, avoidance). Likewise, the classically externalizing disorders retained unique relationships to the externalizing factor; all except BPD loaded only on the externalizing factor. Item-explained common variances showed that CD, ODD, ADHD, and a portion of DMDD remained nearly pure indicators of externalizing psychopathology. This independence of externalizing and some internalizing symptoms may be partly methodological. Given the observable, behavioral content of most externalizing symptoms, the relative independence of CD, ODD, and ADHD may be driven in part by reporting biases in caregivers. The subjectivity of worry, by contrast, may obscure GAD and related cognitive symptoms from observation, leaving anxiety disorder indicators vulnerable to low insight or reporting biases in youth.

To the extent that the subfactors’ independence was not artifactual, it could have implications for understanding the mechanisms and course of adolescent psychopathology. Given the different nature of our sample, findings do not contradict previous findings in community samples, but rather, provide a complementary view in a sample designed to maximize variance in clinically significant presentations. The partial independence of subfactors raises the possibility that a general psychopathology factor only weakly or incompletely explains many behavioral symptoms in clinically referred early adolescents. This could signal, perhaps, that early adolescent disruptive behaviors and/or anxiety symptoms may have mechanisms that are relatively distinct from the mechanisms of mood disorders (e.g., Nivard et al. 2017). Alternatively, it might indicate that substantial variance in disruptive behaviors and GAD-like symptoms may be driven by developmental processes that are nonpathological, even in a clinically referred sample such as ours. Many may adolescents “age out” of externalizing symptoms (e.g., Costello et al. 2011) and anxiety symptoms (e.g., McLaughlin and King 2014). Perhaps portions of disruptive and anxious symptom variance that will go on to be unremitting might show greater commonality with the general factor.

Disorder-specific findings have implications for future research. DMDD cross-loaded on both internalizing and externalizing factors in the final bifactor model. Its internalizing portion was weaker and less precise than the externalizing portion, as indicated both by lower factor loading and higher I-ECV. Even given this imbalance, the cross-loading of DMDD justifies confusion regarding its conceptualization as predominantly a mood or a disruptive disorder (Althoff et al. 2016; Stringaris et al. 2018). Future work could clarify the relationship of the DMDD construct to psychopathologies across both mood-related and disruptive spectra. BPD symptoms were strongly characteristic of the general factor, which bridged it with most internalizing disorders; yet BPD retained a significant loading on the externalizing factor, bridging it also with those disorders. These findings underscore the high clinical relevance of BPD symptoms in early adolescence and suggest that assessing BPD may efficiently provide a great deal of information on the clinical functioning of impaired adolescents in this age group. BPD findings resemble previous results from a bifactor model of personality disorder symptoms, in which BPD mapped almost fully onto the general factor (Sharp et al. 2015). It remains to be seen whether BPD continues to appear nearly synonymous with general psychopathology variance in future studies assessing both clinical (formerly Axis-I) and personality (formerly Axis-II) syndromes. If BPD remains closely aligned with general psychopathology variance across replications at early stages in psychopathology development, it would alter the conceptualization of BPD and the definition and prediction of transdiagnostic psychopathology.

Alternative Approaches to Criterion Validity of Bifactor Psychopathology Models

Whereas our structural findings must be interpreted within the context of the present sample, the contribution regarding alternative definitions of criterion validity is less sample-dependent and could be useful to researchers working with other populations. In promoting “riskier tests” of bifactor models, Watts et al. (2019) have taught us to be usefully skeptical of new approaches that merely redistribute variance in clinical outcomes without incrementally expanding the amount of psychopathology we can explain. In their view, incremental validity of bifactor models is essentially a prerequisite for criterion validity. This incremental standard has intuitive appeal because it speaks to the basic mission of clinical research to explain as much variance in clinical outcomes as possible. Yet, alternative standards for criterion validity are defensible for at least two reasons—one practical, one theoretical. In a practical sense, the incremental standard creates an interpretive conundrum because it requires regressing a weaker-fitting model than the bifactor model on criterion variables. and the resulting regressed model may not show appropriate fit. In our sample, the criterion validity model using the correlated two-factor model fit the data poorly. Compared to the regressed bifactor model, the regressed correlated-two factor model explained equivalent variance in external criteria, but its overall inappropriateness interferes with knowing what this equivalence means.

In a theoretical sense, criterion validity is distinguishable from incremental validity, in that criterion validity is evaluated based on the presence of conceptually meaningful relationships with external criteria (Kazdin 2002). We demonstrated that a bifactor model can fail to expand the amount of variance explained in clinical outcomes, and at the same time succeed in increasing the precision with which those outcomes are understood (Fig. 2, Panel B). Regression analyses yielded clinically meaningful relationships between psychopathology factors in the bifactor model and psychosocial functioning variables, including a relationship that was undetectable using the correlated two-factor model. Only by partitioning out general psychopathology variance could we reveal that psychosocial functioning impairments were related to uniquely internalizing variance, which was largely anxiety-related. This relationship between anxiety and psychosocial impairments is well founded (Essau et al. 2014; Woodward and Fergusson 2001), and it was therefore likely suppressed by noisiness of the internalizing factor in the correlated two-factor model. This example shows that by parsing more precisely the variance due to common versus specific dimensions of psychopathology, the bifactor model can expose clinically meaningful findings, demonstrating criterion validity according to a concept-focused standard (Kazdin 2002).

Suicide risk results also underscore the viability of the conceptually focused definition of criterion validity of bifactor models. The regression using the correlated two-factor model linked suicide risk to both internalizing and externalizing factors, concealing which aspects of the nine psychopathologies were primarily responsible. The bifactor model streamlined that picture, revealing the source of variance in suicide risk as the general factor (exemplified by this sample’s BPD and depression, perhaps representing emotion dysregulation or relational dysfunction, as speculated above). This suggests criterion validity of our bifactor model, because BPD and depression have already been strongly implicated in suicide (e.g., Evans et al. 2004; Soloff et al. 2000). Although not a focus of the present study, this finding is important in its own right. Virtually all psychopathologies are prevalent among suicide attempters, so it is urgent to isolate narrower portions of symptom variance related to suicide risk (Nock et al. 2019). The bifactor model contributed this very kind of precision, dismissing internalizing and externalizing factors in favor of the general factor as the more robust source of variance in suicide risk.

An early roadmap for transdiagnostic research urged researchers to work toward exposing both general and symptom-specific mechanisms of maladaptation (Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins 2011). Using psychosocial functioning and suicide risk as examples, we showed that the bifactor model contributes to both prongs of that mission. The incremental standard for bifactor models is important (Watts et al. 2019); it is a worthy goal to expand the total amount of variance in psychopathology that we can explain. In contrast, we have shown that, in the instances when one wishes to model precisely both shared and unique psychopathology variance in a given sample, even “mere” redistributions of variance may be clinically informative. In this way our findings reinforce the conclusions of a recent simulation study, that models be selected for their “substantive interpretability” depending on study aims (Greene et al. 2019).

Trade-Offs, Limitations, and Strengths

This sample was smaller than usual for structural modeling (but see Wolf et al. 2013). As such, specific model coefficients may be unreliable and require multiple replications. There is also risk that the clinical characteristics of the sample unduly influenced the pattern of findings. This sample has unusually high prevalence and broad distribution of BPD symptoms, which could exaggerate the appearance of BPD as a common denominator informing the general factor. However, the most prevalent psychopathology in this sample, ADHD, did not show a similar tendency toward acting as a common denominator in the bifactor model. ADHD did not load on the general factor, which explained only 4% of its variance. This makes it unlikely that results were driven straightforwardly by diagnostic prevalences, although subtler sample-specific effects are still possible. Future studies are needed in a wide range of adolescent samples with other clinical characteristics, to verify the invariance of the structure of psychopathology across different adolescent clinical populations. Larger studies of clinically referred adolescents are especially needed to provide more reliable replications.

The cross-sectional nature of the study constrains its interpretation. A few longitudinal structural psychopathology studies have been conducted (e.g., McElroy et al. 2018; Murray et al. 2016; Snyder et al. 2017), but these have not involved clinical samples. Thus, temporal shifts in the “joints” or boundaries between clinically relevant pathological processes remain unknown. Our sample will be pursued longitudinally, but at present we cannot know whether the relatively weak general factor in this cross-sectional snapshot will remain weak over time. The present study contributes a static picture of the structure of psychopathology in a clinically impaired adolescent sample during the transition into adolescence, which is a pivotal time in psychopathology development (e.g., Beesdo et al. 2010). The finding of a modest, only partially transdiagnostic general factor hints that, perhaps, psychopathology in clinically impaired youth in this age group is still fairly differentiated. This differentiation may decline as comorbidity increases in older adolescence, as some theories predict (e.g., dynamic mutualism, stress generation; Conway et al. 2012; McElroy et al. 2018; Murray et al. 2016).

There are advantages to modeling psychopathology at the symptom-level (Conway et al. 2019; Kotov et al. 2018). We opted instead for syndrome-level severities, because these are relevant for ease of communication as others have pointed out (e.g., Conway et al. 2019) and applicable to common clinical practice. Moreover, skip-outs during the K-SADS interview lead later scores to be missing frequently, preventing the use of symptom-level variables. Computing syndrome-level scores using all available data circumvented this problem and allowed us to evaluate adolescent psychopathology using the valuable clinician evaluations. Structural studies using a variety of informants, including clinicians, are needed in order parcel out potential method variance and build a comprehensive picture of psychopathology as it is expressed in early adolescents presenting for treatment. The structure of clinician-rated psychopathology in clinically referred adolescents can also inform unified treatment protocols (e.g., Barlow et al. 2017) and their adaptations to adolescent patients (Ehrenreich-May et al. 2017).

This study prioritized clinical richness over sample size to begin to fill the knowledge gap on the structure of psychopathology among clinically impaired adolescents. In doing so, it highlights the need for psychiatric, epidemiologically scaled studies that could achieve both sides of the trade-off at once. Until then, we hope this study demonstrates the potential utility of conducting small-N, clinically rich structural studies on adolescent psychopathology, for cautious empirical testing and for intervening in the discourse on transdiagnostic methods.

Notes

Coefficients for this unconditional model are in Supplement D. An alternative model loading all 6 indicators together on a factor, with residuals for parallel scores between reporters correlated, showed poor fit, χ2(6) = 29.79, p < .001, RMSEA = .16 [.11,.22], CFI = 0.78, TLI = 0.45.

The initial model fit the data poorly, χ2(27) = 156.14, p < .001, RMSEA = .17 [.15,.20], CFI = 0.60, TLI = 0.47. Discrepancies between observed and model-implied correlations suggested several theoretically-consistent correlations, which were added to the model sequentially to determine whether fit could be improved (i.e., depression with BPD, depression with GAD, GAD with social phobia, GAD with separation anxiety, and separation anxiety with BPD, added in this order). Even after respecifications, fit remained weak, χ2(22) = 47.29, p = .001, RMSEA = .08 [.05,.12], CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.87, and was significantly poorer than for the bifactor model, Δχ2(3) = 27.2, p < .001). Most internalizing pathologies would not load on the one-factor solution (Supplement C), and the density of correlations among error variances was suggestive of a separate latent factor.

Tested separately in two models, psychosocial functioning and suicide risk produced the same patterns of relationships with bifactor model psychopathology factors as when tested together. All model fits were adequate.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1981). Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 1-82.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Afzali, M. H., Sunderland, M., Carragher, N., & Conrod, P. (2018). The structure of psychopathology in early adolescence: Study of a Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(4), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717737032.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Rreview, 30(2), 217–237.

Althoff, R. R., Crehan, E. T., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Hudziak, J. J., & Merikangas, K. R. (2016). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder at ages 13-18: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey - adolescent supplement. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2015.0038.

Bailey, A. J., & Finn, P. R. (2019). Borderline personality disorder symptom comorbidity within a high externalizing sample: Relationship to the internalizing-externalizing dimensional structure of psychopathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 1–13.

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Latin, H. M., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., ... & Cassiello-Robbins, C. (2017). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

Beesdo, K., Pine, D. S., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2010). Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(1), 47–57.

Bender, D. S., & Skodol, A. E. (2007). Borderline personality as a self-other representational disturbance. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(5), 500–517.

Berenson, K. R., Gyurak, A., Ayduk, Ö., Downey, G., Garner, M. J., Mogg, K., Bradley, B. P., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.007.

Bonifay, W., Lane, S. P., & Reise, S. P. (2017). Three concerns with applying a Bifactor model as a structure of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(1), 184–186.

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., & Timpano, K. R. (2017). Toward a functional view of the p factor in psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(5), 880–889.

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Belsky, D. W., Goldman-Mellor, S. J., Harrington, H., Israel, S., Meier, M. H., Ramrakha, S., Shalev, I., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2014). The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 119–137.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831–844.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., Brière, F. N., O'Leary-Barrett, M., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A., Bromberg, U., et al. (2016). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(8), 1039–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000193.

Conway, C. C., Forbes, M. K., Forbush, K. T., Fried, E. I., Hallquist, M. N., Kotov, R., Mullins-Sweatt, S. N., Shackman, A. J., Skodol, A. E., South, S. C., Sunderland, M., Waszczuk, M. A., Zald, D. H., Afzali, M. H., Bornovalova, M. A., Carragher, N., Docherty, A. R., Jonas, K. G., Krueger, R. F., Patalay, P., Pincus, A. L., Tackett, J. L., Reininghaus, U., Waldman, I. D., Wright, A. G. C., Zimmermann, J., Bach, B., Bagby, R. M., Chmielewski, M., Cicero, D. C., Clark, L. A., Dalgleish, T., DeYoung, C. G., Hopwood, C. J., Ivanova, M. Y., Latzman, R. D., Patrick, C. J., Ruggero, C. J., Samuel, D. B., Watson, D., & Eaton, N. R. (2019). A hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology can transform mental health research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 419–436.

Conway, C. C., Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. A. (2012). Expanding stress generation theory: Test of a transdiagnostic model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(3), 754–766.

Costello, E. J., Copeland, W., & Angold, A. (2011). Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: What changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 52(10), 1015–1025.

Curtin, S. C., & Heron, M. P. (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017.

DeYoung, C. G., & Krueger, R. F. (2018). A cybernetic theory of psychopathology. Psychological Inquiry, 29(3), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2018.1513680.

Eaton, N. R., Krueger, R. F., Keyes, K. M., Skodol, A. E., Markon, K. E., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. S. (2011). Borderline personality disorder comorbidity: Relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 1041.

Ehrenreich-May, J., Rosenfield, D., Queen, A. H., Kennedy, S. M., Remmes, C. S., & Barlow, D. H. (2017). An initial waitlist-controlled trial of the unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 46–55.

Essau, C. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., Olaya, B., & Seeley, J. R. (2014). Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. Journal of Affective Disorders, 163, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033.

Evans, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2004). Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(8), 957–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005.

Greene, A. L., Eaton, N. R., Li, K., Forbes, M. K., Kreuger, R. F., Markon, K., et al. (2019). Are fit indices used to test psychopathology structure biased? A simulation study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(7), 74–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000434.

Hallquist, M. N., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2012). Refining the phenotype of borderline personality disorder: Diagnostic criteria and beyond, Personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment., 3(3), 228. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027953.

Haltigan, J. D., Aitken, M., Skilling, T., Henderson, J., Hawke, L., Battaglia, M., Strauss, J., Szatmari, P., & Andrade, B. F. (2018). “P” and “DP:” examining symptom-level bifactor models of psychopathology and dysregulation in clinically referred children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(6), 384–396.

Hammer, J. H., & Toland, M. D. (2016, November). Bifactor analysis in Mplus. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://sites.education.uky.edu/apslab/upcoming-events/

Jopling, E. N., Khalid-Khan, S., Chandrakumar, S. F., & Segal, S. C. (2016). A retrospective chart review: adolescents with borderline personality disorder, borderline personality traits, and controls. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 30(2), 1–9.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U. M. A., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., ... & Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988.

Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Research design in clinical psychology, 4th edn. New York: Pearson.

Keenan, K., Hipwell, A., Chung, T., Stepp, S., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Loeber, R., & McTigue, K. (2010). The Pittsburgh girls study: Overview and initial findings. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(4), 506–521.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627.

Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., & Watson, D. (2018). A paradigm shift in psychiatric classification: The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP). World Psychiatry, 17(1), 24–25.

Kovacs, M., Lopez-Duran, N. L., George, C., Mayer, L., Baji, L., Kiss, E., Vetró, Á., & Kapornai, K. (2019). The development of mood repair response repertories: Age-related changes among 7-to 14-year-old depressed and control children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 143–152.

Kring, A. M., & Sloan, D. M. (Eds.). (2009). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. Guilford Press.

Krueger, R. F., & Markon, K. E. (2006). Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213.

Laceulle, O. M., Vollebergh, W. A. M., & Ormel, J. (2015). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence: Replication of a general psychopathology factor in the TRAILS study. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 850–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614560750.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Hakes, J. K., Zald, D. H., Hariri, A. R., & Rathouz, P. J. (2012). Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(4), 971–977. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028355.Is.

Lahey, B. B., Van Hulle, C. A., Singh, A. L., Waldman, I. D., & Rathouz, P. J. (2011). Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(2), 181–189.

Markon, K. E. (2019). Bifactor and hierarchical models: Specification, inference, and interpretation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 51–69.

Martel, M. M., Pan, P. M., Hoffmann, M. S., Gadelha, A., do Rosário, M. C., Mari, J. J., … Salum, G. A. (2017). A general psychopathology factor (P factor) in children: Structural model analysis and external validation through familial risk and child global executive function. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 137–148.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64.

McElroy, E., Belsky, J., Carragher, N., Fearon, P., & Patalay, P. (2018). Developmental stability of general and specific factors of psychopathology from early childhood to adolescence: Dynamic mutualism or p-differentiation? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 59(6), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12849.

McLaughlin, K. A., & King, K. (2014). Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(2), 311–323.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(3), 186–193.

Morey, L. C. (2007). Personality assessment inventory. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Morey, L. C., Benson, K. T., Busch, A. J., & Skodol, A. E. (2015). Personality disorders in DSM-5: Emerging research on the alternative model. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 1–9.

Morey, L. C., Good, E. W., & Hopwood, C. J. (2020). Global personality dysfunction and the relationship of pathological and Normal trait domains in the DSM-5 alternative model for personality disorders. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12560

Murray, A. L., Eisner, M., & Ribeaud, D. (2016). The development of the general factor of psychopathology ‘p factor’ through childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(8), 1573–1586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0132-1.

Muthén, B. O. & Muthén, L. K. (1998-2011). Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Los Angeles.

Nivard, M. G., Lubke, G. H., Dolan, C. V., Evans, D. M., St Pourcain, B., Munafò, M. R., & Middeldorp, C. M. (2017). Joint developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing disorders between childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 29(3), 919–928. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000572.

Nock, M. K., Ramirez, F., & Rankin, O. (2019). Advancing our understanding of the who, when, and why of suicide risk. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 11–12.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Watkins, E. R. (2011). A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: Explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 589–609.

Patalay, P., Fonagy, P., Deighton, J., Belsky, J., Vostanis, P., & Wolpert, M. (2015). A general psychopathology factor in early adolescence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(1), 15–22.

Pettersson, E., Larsson, H., & Lichtenstein, P. (2016). Common psychiatric disorders share the same genetic origin: A multivariate sibling study of the Swedish population. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(5), 717–721. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.116.

Pettersson, E., Lahey, B. B., Larsson, H., & Lichtenstein, P. (2018). Criterion validity and utility of the general factor of psychopathology in childhood: Predictive associations with independently measured severe adverse mental health outcomes in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(6), 372–383.

Prinstein, M. J., Cheah, C. S. L., Borelli, J. L., Simon, V. A., & Aikins, J. W. (2005). Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 676–688.

Reise, S. P., Kim, D. S., Mansolf, M., & Widaman, K. F. (2016). Is the bifactor model a better model or is it just better at modeling implausible responses? Application of iteratively reweighted least squares to the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(6), 818–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2016.1243461.

Ribeiro, J. D., Franklin, J. C., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2016). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001804.

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P., & Haviland, M. G. (2016). Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 137–150.

Sharp, C., Wright, A. G., Fowler, J. C., Frueh, B. C., Allen, J. G., Oldham, J., & Clark, L. A. (2015). The structure of personality pathology: Both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(2), 387–398.

Snyder, H. R., Gulley, L. D., Bijttebier, P., Hartman, C. A., Oldehinkel, A. J., Mezulis, A., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2015). Adolescent emotionality and effortful control: Core latent constructs and links to psychopathology and functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1132–1149. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000047.

Snyder, H. R., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2017). Strong homotypic continuity in common psychopathology-, internalizing-, and externalizing-specific factors over time in adolescents. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(1), 98–110.

Soloff, P. H., Lynch, K. G., Kelly, T. M., Malone, K. M., & John Mann, J. (2000). Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: A comparative study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(4), 601–608.

Sprooten, E., Rasgon, A., Goodman, M., Carlin, A., Leibu, E., Lee, W. H., & Frangou, S. (2017). Addressing reverse inference in psychiatric neuroimaging: Meta-analyses of task-related brain activation in common mental disorders. Human Brain Mapping, 38(4), 1846–1864.

Stringaris, A., Vidal-Ribas, P., Brotman, M. A., & Leibenluft, E. (2018). Practitioner review: Definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 59(7), 721–739.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 25–52.

Watts, A. L., Poore, H. E., & Waldman, I. D. (2019). Riskier tests of the validity of the bifactor model of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1285–1303.

Weissman, D. G., Bitran, D., Miller, A. B., Schaefer, J. D., Sheridan, M. A., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2019). Difficulties with emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic mechanism linking child maltreatment with the emergence of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000348.

Williams, L. J., & McGonagle, A. K. (2016). Four research designs and a comprehensive analysis strategy for investigating common method variance with self-report measures using latent variables. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(3), 339–359.

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934.

Woodward, L. J., & Fergusson, D. M. (2001). Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(9), 1086–1093.

Wright, A. G., Thomas, K. M., Hopwood, C. J., Markon, K. E., Pincus, A. L., & Krueger, R. F. (2012). The hierarchical structure of DSM-5 pathological personality traits. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 951–957. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027669.

Zanarini, M. C. (2003). Childhood Interview for DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (CI-BPD). Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital.

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript was aided by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH101088, PI: Stepp; T32 MH018951, PI: Brent; K01 MH119216, PI: Byrd; K01 MH101289, PI: Scott; K01 MH109859, PI: Beeney).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 85.6 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vine, V., Byrd, A.L., Mohr, H. et al. The Structure of Psychopathology in a Sample of Clinically Referred, Emotionally Dysregulated Early Adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 48, 1379–1393 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00684-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00684-x