Abstract

This longitudinal investigation examined interactions between aggression and peer victimization during middle childhood in the prediction of arrest through the adult years for 388 (198 boys, 190 girls) study participants. As part of an ongoing multisite study (i.e., Child Development Project), peer victimization and aggression were assessed via a peer nomination inventory in middle childhood, and juvenile and adult arrest histories were assessed via a self-report questionnaire as well as review of court records. Early aggression was linked to later arrest but only for those youths who were rarely victimized by peers. Although past investigators have viewed youths who are both aggressive and victimized as a high-risk subgroup, our findings suggest that the psychological and behavioral attributes of these children may mitigate trajectories toward antisocial problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this study, we examined aggression and victimization by peers during childhood as interacting predictors of arrest during adolescence and adulthood. Childhood aggression is a powerful marker of serious antisocial problems in later stages of development. Indeed, there are well-documented associations between aggressive behavior and antisocial outcomes in adulthood that include criminal behavior and eventual arrest (Huesmann et al. 2002; Patterson et al. 1998). Aggression early in life could serve as a lead indicator of emerging antisocial traits (Dodge and Pettit 2003) as well as a correlate of problematic socializing experiences (Petersen et al. 2015). Still, the full picture is complicated by themes that have emerged from the literature on bullying in school peer groups. As first described in Olweus’ (1978) seminal work on Swedish bullies and their “whipping boys,” some highly aggressive children are also frequent targets of bullying. Because this subgroup is characterized by distinct behavioral and psychological features (Schwartz 2000), youths who are both aggressive and victimized by peers may experience a unique developmental trajectory.

Children who are concurrently aggressive and victimized are now a well-recognized subgroup, although conceptualizations regarding the attributes of these youths vary across literature. The term “bully-victim” has been widely used in the extant research (Cook et al. 2010), perhaps implying that some children alternate between the roles of aggressor and victim. Other formulations have emphasized difficulties in self-regulation that might include impulsiveness, poorly modulated affect, and over reactivity (Schwartz et al. 2001). From these perspectives, aggressive victims are not expected to exhibit the goal-oriented behavioral profiles associated with perpetration of bullying (i.e., aggression used to purposely dominate peers). Rather, these children may display more disorganized “hot-headed” and overly reactive behavior (Perry et al. 1992).

To some extent, differences in conceptualization could reflect measurement issues and implicit assumptions regarding the nature of the underlying phenomenon. The construct of bullying has often been viewed through the lens of Olweus’ (1993) definitional criteria, incorporating key features such as imbalance of power and chronicity. Self-report inventories that assess involvement in bullying (as either an initiator or a target) generally specify these criteria and with items that are worded specifically to detect a relatively narrow range of behaviors. Under these circumstances, the bully-victim label seems logical. In other research traditions, bullying is essentially operationalized as an indicator of high levels of aggression toward peers, and there is less of a focus on the specific topography of the behavior. Typically, peer nomination inventories and teacher rating forms do not alert respondents to the particular features of bullying. The terminology in the latter body of work does not bring strong a priori assumptions regarding subtypes of aggressive behavior.

Despite inconsistencies in measurement approaches, as well as variability in terms and labels, there remains a remarkable degree of consistency in the findings across the literature with regard to short-term psychosocial correlates. On an immediate basis, youths who are concurrently aggressive (i.e., characterized by either high levels of bullying or other forms of agonistic behavior) and victimized are more likely to be characterized by maladjustment across domains than other subgroups of aggressive or victimized youths. Cross-sectional (Toblin et al. 2005) and short-term longitudinal findings (Lereya et al. 2015) are indicative of extremely high levels of both internalizing and externalizing problems as well as serious academic difficulties. These youths also tend to be somewhat more aggressive and hyperactive than bullies (i.e., rarely victimized children who are highly aggressive) while also experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Schwartz 2000; Toblin et al. 2005).

The eventual adult outcomes that aggressive victims experience are not yet fully clear, given the limited availability of long-term data. Moreover, investigators have often operationalized aggression and peer victimization as unitary dimensions of social experience without an explicit focus on potential interactions (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2015; Sourander et al. 2011). Still, a handful of relevant studies do exist with the available evidence indicating that childhood aggression and bullying by peers can combine to amplify risk for psychosocial difficulties during adulthood (Sourander et al. 2007; Wolke et al. 2013).

With regard to prediction of arrests and related antisocial outcomes, there may be reasons to view aggressive youths who also experience frequent victimization as a particularly vulnerable subgroup. As noted above, existing conceptualizations have often portrayed these youths as being characterized by deficits in self-regulation that manifest with hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and other disruptive behavior problems (Schwartz 2000). The externalizing difficulties displayed by aggressive victims might then be expected to potentiate involvement in a wider range of antisocial behaviors. Consider, for example, elevated rates of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms among youths who are both aggressive and victimized (Schwartz et al. 2001). Longitudinal research has demonstrated predictive relations between symptoms of this nature during the childhood years and later trajectories toward arrest (Lahey et al. 2016).

Although there are certainly reasons to expect long-term risk for criminal justice outcomes, the limited findings that are available suggest a more nuanced pattern. We are aware of only two studies that have examined aggression and victimization by peers in childhood as simultaneous predictors of arrest through the adult years. Sourander et al. (2007) conducted analyses based on the Finnish “Boys to Men” study, with self-reported involvement in peer group victimization during childhood as a predictor of adult criminal outcomes. Bullies were slightly more likely to experience adult arrest than bully-victimsFootnote 1, but recidivism rates were particularly elevated for bully-victims. Wolke et al. (2013) examined relations between childhood victimization and bullying (assessed via self- and parent- report) and criminal outcomes in the context of the Great Smoky Mountains Study. These investigators reported that bullies were somewhat more likely to engage in later risky or illegal behaviors than bully-victims.

The ambiguous pattern emerging from the initial research might partially reflect the marked deficits in emotional and behavioral self-regulation that hypothetically characterize children who are both initiators and targets of peer aggression (Perry et al. 1992; Schwartz 2000). The externalizing behavior of these children appears to be a product of poorly modulated affect and not just trait-fearlessness, defiance, or a general antisocial orientation (Schwartz et al. 2001; Toblin et al. 2005). Accordingly, aggressive victims may not gravitate toward premeditated offenses or planned criminal activity. We would not expect aggressive victims to use force to obtain external goals. Likewise, in the absence of antisocial motivations, nonaggressive criminal or rule-breaking behavior would seem to be relatively unlikely (e.g., shoplifting and other petty thefts).

It is also important to consider the social marginalization experienced by this high-risk subgroup. Aggressive victims tend to be widely disliked by their peers. On average, they receive much higher social rejection scores (e.g., peer nominations for disliking) than bullies or nonaggressive victims (Schwartz 2000). These youths also have difficulty forming intimate relationships. They lack friendships and are excluded from cliques and related network structures (Pellegrini et al. 1999; Toblin et al. 2005). This social isolation could function to mitigate potential for group-oriented antisocial behaviors and may constrict exposure to antisocial role models.

In the current paper, we focused on aggression and victimization by peers during middle childhood as predictors of arrest during the adolescent and adult years. We analyzed data from the Child Development Project (CDP), an ongoing multisite study in which participants have been followed from the preschool years through adulthood. The CDP has been the basis for past reports on persistently bullied youths (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2000, 2008a, 2013, 1998, 1999;), including one of the earliest published investigations focusing on the aggressive victim subgroup (Schwartz et al. 1997). This project includes peer nomination assessments of aggression and victimization in the middle years of elementary school and indices of antisocial behavior through adulthood. To present a full picture of the developmental progression, we examine aggression and peer victimization as markers of both juvenile arrests (middle to late adolescence), and adult arrest histories. Our goal was to consider a sequence of developmental stages (adolescence and early adulthood) in an effort to understand cascading processes.

We anticipated that childhood aggression would be strongly predictive of eventual arrest. However, we expected that the full pattern would be moderated by peer victimization. Our hypothesis was that the association between early aggression and contact with the criminal justice system would be attenuated for those youths who also experienced frequent bullying by peers. This expectation was informed by the limited findings examining adult outcomes that are presently available as well as our own theoretical conceptualization of the attributes of the aggressive victim subgroup. Based on the existing conceptualizations (Perry et al. 1992; Schwartz 2000; Toblin et al. 2005), our assumption was that concurrent high levels of aggression and peer victimization would identify emotionally dysregulated youths who are unlikely to engage in goal-oriented antisocial behavior. Under these conditions, a statistical interaction between aggression and peer victimization might serve as an efficient marker of characteristics that preclude involvement in some forms of criminal behavior.

In conducting our analyses, we were careful to take into account the potential moderating role of gender. Boys are far more likely than girls to experience concurrent problems with aggression and victimization (Schwartz et al. 2001), a finding that replicates even when relational and overt subtype distinctions are taken into account (Toblin et al. 2005). Adult males are also more likely to experience a wider variety of antisocial outcomes than females (Petersen et al. 2015). These main-effect patterns notwithstanding, little is known about the way that gender influences (or does not influence) risks associated with interactions between peer victimization and aggression.

Our analyses also included ethnic/racial background and socioeconomic status (SES) as main-effect covariates. In past research conducted with the CDP data, we did not find associations between SES and bully/victim status (Schwartz et al. 1997). Most notably, youths who experienced concurrent difficulties with aggression and peer victimization were not especially likely to have come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Nonetheless, we view SES as a complex construct that can function as a correlate and marker of wide range of problematic influence (e.g., aggressogenic home environments; Dodge et al. 1994). The underlying mechanisms may be multifaceted, but economic hardship is linked to an array of social difficulties in childhood as well as antisocial outcomes in adulthood.

We included ethnic/racial background as an additional covariate given well-documented group differences in arrest rates for both adolescents and adults (Piquero and Brame 2008). Ethnicity is a broad contextual factor that is a marker of cultural experience, patterns of interaction with dominant social institutions, and larger sociological forces (e.g., racial bias). The impact of peer victimization on development processes could also be partially determined by interactions between the youths’ own background and the composition of the proximal social environment (Graham et al. 2009). Although these complexities preclude strong hypotheses related to direction of effect, we sought to increase the precision of our models through consideration of this potential confounder.

To summarize, the objective of the current paper is to examine interactions between peer victimization and aggression during middle childhood and antisocial indicators in two developmental epochs. We hypothesized that the link between early aggression and later antisocial outcomes would be attenuated for those who were also frequent targets of victimization by peers. We also considered gender as an additional moderating factor and included SES and ethnic/racial background as important covariates in all our models.

Method

Participant Recruitment and Retention

The CDP is a multisite prospective study that began in 1987 and has included annual assessments through childhood and adolescence. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant institutional review boards. Two separate cohorts, recruited in consecutive years, are participating in the CDP. We recruited both cohorts from the same school districts, and they did not differ markedly in composition. There were no differences across cohorts in the concurrent correlates, predictors, or outcomes associated with peer group victimization (Schwartz et al. 1997).

Full details regarding the recruitment of the CDP sample are described in numerous past reports based on this project (e.g., Dodge et al. 1994). However, as a brief summary, we recruited the initial sample just prior to kindergarten enrollment in three geographic regions (Bloomington, IN; Knoxville, TN; Nashville, TN). Research staff approached parents at the time of kindergarten preregistration, and invited them to participate in a longitudinal study of child development. These parents were then asked to complete a parental consent form.

About 75% of the parents consented. A total of 585 children (304 boys, 281 girls) participated in the study, 308 in Cohort 1 (C1) and 277 in Cohort 2 (C2). By the time they reached middle childhood, the original participants had been dispersed into a number of different elementary schools over a wide geographic area. Resource limitations precluded data collection in all of these schools, but we obtained peer nomination data for a representative subsample (388 children; 198 boys, 190 girls; 297 European American; 84 African American; 7 other) of the initial participants. This subsample has been the subject of a number of previous reports based on the CDP (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2000), and our past analyses have demonstrated similar patterns of attributes to the full sample. Approximately 26% of the children came from families classified in the two lowest socioeconomic status groups (Dodge et al. 1994). These children attended schools in a range of urban, suburban, and semirural contexts.

Peer victimization and aggression were assessed with a peer nomination inventory that was administered in the 5th year of the project. At this point in the data collection, C1 was in the fourth grade (average of approximately 9 years) and C2 (average age of 8 years) was in the third grade. Juvenile arrest histories were assessed at age 18, using self-report and review of court records. In similar manner, adult arrest histories (i.e., arrests after the age of 18) were assessed at age 27. Arrest data was available at both waves of assessment for the full subsample. Thus, analyses were conducted with no missing values.

Procedures

In the summer before the participants began kindergarten, trained interviewers visited homes and conducted a structured interview directly with parents (for further details see Dodge et al. 1994). Data obtained from this interview were then used to assess the demographic backgrounds (e.g., SES) of the participants.

During the fifth year of the project, schools were visited by a team of trained graduate and undergraduate research assistants. The research assistants administered the peer nomination inventories in a group format, conducted in the participant’s primary school classroom. Items were read out loud, as research assistants circulated the class to answer question and ensure confidentiality.

In the adolescent and early adult years, follow-up data collections (e.g., the self-report assessment of arrest) were accomplished via multiple methods. Depending on the specific year of the project and logistical issues (e.g., whether the participant lived too far from the data collection sites to make in person data collection possible), data were collected online, in person, over the telephone, or through the mail.

Measures

Peer Victimization

Children were given a roster with the names of all peers in their classroom, and asked to identify up to three classmates who fit a series of descriptors. Three of these descriptors assessed children’s social reputation as a victim (i.e., “kids who get picked on,” “kids who get teased,” “kids who get hit or pushed”). For each child, a victimization score was calculated from the total number of nominations received for the three items (α = .82) standardized within classroom.

Current standards emphasize the assessment of both relational and overt subtypes of peer victimization (Crick and Grotpeter 1995), whereas the items in the CDP either tap overt victimization or are not specific to either subtype. Nonetheless, in a previous paper (Schwartz et al. 2008a), we used the CDP data to replicate findings from an independent 2-year longitudinal study that was conducted with separate items for relational and overt victimization (i.e., Schwartz et al. 2008b).

Aggression

The peer nomination inventory also included three descriptors assessing children’s social reputation as aggressive (“kids who start fights,” “kids who say mean things,” “kids who get mad easily”). An aggression score was calculated from the total nominations received for these items, standardized within class (α = 0.89).

SES

As part of data obtained from a structured interview conducted directly with parents (Dodge et al. 1994), we calculated Hollingshead’s (1979) index to assess family socioeconomic status background. This index is based on level of education and occupation of both the mother and father (or other male partner).

Arrests during the Adolescent Years

Histories of arrest for offenses (status, violent, or nonviolent) prior to age 18 were obtained directly from court records. Youths also completed a dichotomous item indicating arrest history as part of a larger self-report inventory. Concordance between the two sources (i.e., arrest of any type as compared to self-reported arrest) was 77%. The disagreement that did exist may reflect record keeping errors in the public system but might also be indicative of formal detainments in which charges were eventually dropped.

For later analysis, we created a summary dichotomous score that was indicative of arrest via either data source (1 = self-reported and/or court-reported arrest of any kind; 0 = no arrest). Because the combined score collapses across arrest categories, it does not allow for fined-grained analysis of specific forms of criminal behavior. We opted to take this approach partially because we viewed arrest as a broad indicator of antisocial trajectories and did not have hypotheses predicting arrests for specific forms of crime. On a more pragmatic level, we were wary of the small cell sizes that would result from analyses focused on the individual indicators, particularly given the conservative nature of the predictor (i.e., statistical interactions between aggression and victimization).

Arrests during the Adult Years

Histories of arrest for offenses after age 18 were similarly derived from court records (including violent and nonviolent offenses). Participants also completed a dichotomous item indicating adult arrest history as part of a larger self-report inventory. Concordance between the two sources was identical to the pattern for adolescent assessments at 77%. For later analyses, we generated a summary dichotomous score that collapsed across all indices (1 = self-reported or court-reported arrest of any kind; 0 = no arrest).

Results

Overview

Our analytic strategy involved distinct steps, with descriptive statistics, bivariate analyses, and multivariate models. We considered the primary study hypotheses using logistic regression to predict dichotomous arrest outcomes. Previous research on youths who are both aggressive and victimized has tended to emphasize categorical analyses. The general strategy is to use cutoff scores or other criteria to identify bully/victim subgroups. However, we wanted to optimize statistical power and avoid potential induction of artifacts. These concerns loomed particularly large, insofar as our focus was on the prediction of extreme dichotomous outcomes. Accordingly, we maintained the full distribution for the peer victimization and aggression variables.

For each developmental epoch, we conducted a series of hierarchical logistic regression models predicting dichotomous arrest outcomes. We examined peer victimization by aggression interactions in these models and we included two- and three-way interaction effects involving gender. SES and ethnic/racial background (coded as dichotomous yes/no scores for European American and African American backgrounds) were entered as main-effect covariates in these models. On the first step of each of these models, we entered the main effects for gender, ethnicity, SES, aggression, and victimization. On the second step, we entered the two-way interactions for victimization by gender, aggression by gender, and victimization by aggression. On the third step, we entered the three-way effect for peer victimization by aggression by gender. Variables were entered simultaneously at each step, and steps were entered sequentially.

Univariate and Bivariate Statistics

Means and standard deviations are presented for all variables in Table 1. We also examined bivariate correlations between continuous variables. As noted in earlier reports based on the CDP (e.g., Schwartz et al. 1997), aggression and peer victimization were positively correlated, with a medium effect size, r = 0.37, p < 0.01. In addition, aggression was negatively associated with SES, r = −0.21, p < 0.01, whereas peer victimization was not significantly correlated with SES, r = −0.05, ns.

Aggression and Peer Victimization as Predictors of Juvenile Arrests from Middle to Late Adolescence

Next, we conducted a series of stepwise logistic regressions with the dichotomous juvenile arrest score as the outcome. As shown in Table 2, there were significant peer victimization and aggression main effects on Step 1. Peer victimization was negatively associated with adolescent arrests whereas aggression was positively associated with arrest. There were no significant interactions on Step 2 or Step 3. Note that odds ratios (and the corresponding confidence intervals) are not summarized in Table 2, and we rely instead on the unstandardized regression parameters. The effect of interest in these models is the aggression by victimization interaction. In this case, the odds ratio for aggression would be dependent on the level of victimization.

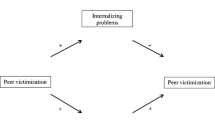

Aggression and Peer Victimization as Predictors of Adult Arrests

In a similar manner, stepwise logistic regressions were conducted with the dichotomous adult arrest score as the outcome. As shown in Table 2, there was a significant peer victimization by aggression interaction on the second step. We decomposed the peer victimization by aggression effect using Aiken and West’s (1991) recommendations. Adult arrests were predicted from ethnicity, SES, gender, and aggression at low (1 SD below the mean), medium (the mean), and high levels of peer victimization (1 SD above the mean). Consistent with our hypotheses the association between aggression and arrest declined as the level of peer victimization moved from low, OR = 1.68, p = 0.03, 95% CI [1.07, 2.65], to medium, OR = 1.21, ns, 95% CI [0.89, 1.63], to high, OR = 0.87, ns, 95% CI [0.61,1.23].

Discussion

During childhood, aggressive behavior and victimization in the peer group are partially intertwined social experiences (Ostrov 2010). As one manifestation of the overlap, a small percentage of highly aggressive youths emerge as persistent targets of bullying (Olweus 1978; Perry et al. 1988; Schwartz 2000). Children who are both aggressive and victimized tend to be characterized by unique behavioral and psychological attributes (Schwartz et al. 2001). Accordingly, questions may be raised regarding the eventual developmental outcomes experienced by this extreme subgroup. In fact, the findings of the current project revealed an interaction between aggression and peer victimization in the prediction of adult arrests. We found evidence that high levels of peer victimization can attenuate associations between early aggression and later contact with the criminal justice system (as indicated by arrest histories during the adult years). Our results provide new evidence that victimization by peers, and whatever these experiences imply about developmental process, can influence the likelihood of association between early aggression and later arrest.

Past investigators have generally viewed children who are concurrently victimized and aggressive as a high-risk subgroup (Nansel et al. 2001; Sourander et al. 2007). These youths exhibit marked deficits in emotional and behavioral self-regulation and experience dysfunction in a number of different domains (Schwartz et al. 2001). Compared to other aggressive and/or victimized youths, they display high rates of both externalizing and internalizing behavior problems (Schwartz 2000). Moreover, aggressive victims are among the most rejected children in the peer group and are likely to have difficulties forming friendships (Toblin et al. 2005). Given these significant functioning difficulties, trajectories toward serious antisocial outcomes seem possible.

The results from our current analyses suggest that peer victimization might serve as an indicator of attenuated risk. We examined interactions between aggression and peer victimization during middle childhood as predictors of arrest histories in late adolescence and adulthood. During adolescence, there was a main- effect negative association between peer victimization and juvenile arrest. By adulthood, however, there was a significant aggression by peer victimization interaction. At high levels of peer victimization, aggression was not related to arrest. Conversely, predictive relations between aggression and arrests were evident at low levels of peer victimization.

The processes underlying these results are not yet clear. Nonetheless, we speculate that the co-occurrence of aggressive behavior and victimization by peers can serve as a marker of behavioral and psychological attributes that mitigate risk for later contact with the criminal justice system. Existing conceptualizations portray aggressive victims as emotionally dysregulated and prone to ineffective displays of hotheaded aggression (Olweus 1978; Perry et al. 1992). Although some victimized youths may also be characterized by callous-unemotional traits (Barker and Salekin 2012), they will still lack the capacity to use antisocial behavior as an efficacious strategy for reaching external goals (Schwartz et al. 2001). Belief systems that potentiate involvement in criminal behavior, such as defiant attitudes toward authority, could also be relatively unlikely. Ultimately, their disorganized behavior, high levels of anxiety, and lack of antisocial motivation, could mitigate risk for arrest.

Social isolation would seem to be another relevant factor to consider. Aggression is a strong correlate of social rejection during the elementary school years. Nonetheless, aggressive youths who are not victimized can still succeed in forming dyadic friendships (albeit with other aggressive peers; Low et al. 2013) and may eventually achieve a degree of social prominence as the transition to adolescence unfolds (Cillessen and Mayeux 2004). Aggressive victims, in contrast, have greater difficulties establishing friendships and tend to remain socially isolated. They may thus be excluded from some group-oriented contexts (e.g., gang violence) in which arrests are likely to occur.

These hypotheses notwithstanding, it is important to recognize that the present study was not focused on mechanisms or underlying process. We examined interactions between aggression and peer victimization during middle childhood as markers of antisocial outcomes in distinct developmental epochs. Our results shed light on a previously undetected statistical association, but we are not attempting to use the findings as demonstrations of causal process. For example, our moderator analyses should not be viewed as suggesting that frequent victimization by peers can be conceptualized as a buffering factor.

Related cautions were offered by Wolke et al. (2013), who viewed early involvement in bullying (as either a perpetrator or victim) as a correlate of a wider set of risk factors. These investigators systematically controlled a variety of contextual factors in their models. Their conclusion was that links between bullying and criminal justice outcomes were likely to have roots in a wider pattern of childhood adversity as well as premorbid antisocial tendencies. Results of this nature are not surprising; given the equifinality that characterizes trajectories toward antisocial outcomes. Still, it does seem important to recognize that bully/victim problems are complex phenomena that can serve as distal indicators of a wide range of eventual risk processes. We were careful to include theory-relevant covariates (e.g., socioeconomic status), which enhances our confidence in the findings. Nevertheless, they cannot account for the full complexity of etiological pathways.

Wolke et al.’s (2013) caveats regarding the importance of external factors as well as existing psychological attributes are pertinent in light of the results produced by our logistic models. We did not find a consistent pattern of main-effect relations between aggression and later arrest. In fact, in our models examining adult outcomes, aggression was only predictive of arrest for those youths who were infrequently victimized by peers. We would expect these youths to be especially likely to be characterized by callous-unemotional traits (Zych, Ttofi, & Farrington, 2016) and to hold positive expectations for the outcomes associated with aggressive behavior (Schwartz et al. 1998). The pathways from early aggression to later antisocial outcomes are likely to be influenced by interactive and transactional processes (Dodge and Pettit 2003).

Questions also remain regarding the potential role of gender. We did not find any gender interactions in our analyses. As a caveat, the bully/victim assessment in the CDP was developed before validation of the distinction between relational and overt aggression (Crick and Grotpeter 1995). It may be the case that a more nuanced assessment that facilitates detection of victimization in girls’ peer groups might have produced a distinct pattern. It also seems important to recognize that girls who experience concurrent problems with aggression and peer victimization may represent a unique subpopulation (Schwartz et al. 2001).

With regard to detecting extreme subgroups, there are empirical tradeoffs associated with categorical and dimensional perspectives. Research in this domain has often operationalized peer victimization and aggression as continuous predictors. This general strategy optimizes statistical power by retaining the full distribution and allows for complex modeling. Other investigators have relied on categorical analyses, either using cutoff scores or more naturally occurring empirical distinctions to identify subgroups of aggressive and/or victimized youths. Although either methodology is justifiable, the findings of the current investigation suggest that aggression and peer victimization may be interacting processes. With either dimensional or categorical approaches, it will be important to recognize that co-occurrence can potentiate a unique pattern of outcomes.

Analyses that focus on subgroups or statistical interactions might also be shaped by the nature of the underlying assessment approaches. Research on subgroups who are both aggressive and victimized has tended to emphasize self-report methodologies. Indeed, nearly all of the published long-term investigations rely in part, or in whole, on youth self-reports. Peer nomination methodologies have been used much less often, at least in subgroup investigations that include data on adult outcomes. In fact, the CDP is the only known project to examine relations between peer nominated victimization and adult arrests. Self-report and peer nomination data can both provide valid and reliable assessments (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002), but agreement across data sources has not always been high (Perry et al. 1988). The idea that peer nominations (i.e., reputational assessments) and survey data (i.e., self-perceived social situation) might capture distinct information is certainly not new. Research on the aggressive victim subgroups has produced consistent findings across studies (Schwartz et al. 2001). Still, methodological issues of this nature can help explain any incongruities that do emerge.

Measurement strategies warrant particular consideration in relation to the operationalization of bullying and/or aggression. Olweus’ (1993) influential conceptualization of bullying emphasizes an imbalance of power (both social and physical) between the initiator and victim, chronicity, and negative intent. These definitions are core components of some measurement approaches (including Olweus’ own well-validated and widely used inventory). On the other hand, peer nomination methodologies, behavior problem checklists, and teaching rating scales tend to capture more undifferentiated forms of aggression. A targeted focus on bullying as specific subtype of aggression versus more global assessments may yield different conclusions.

Regardless of these significant methodological issues, our findings emphasize the importance of delineating the implications of interactions between aggression and victimization. The idea that youths who are both initiators and targets of aggression represent a distinct subgroup was first proposed by Olweus (1978). Based on open-ended comments by teachers, Olweus described a group of “provocative” whipping boys who were irritable, hot-tempered, and likely to fight back when attacked. Similar subgroups were later identified by other research teams (Perry, Kusel, & Perry, 1988; Schwartz 2000). Despite these early findings, aggression and victimization are often conceptualized as independent dimensions with interactions and interdependencies rarely a main theme.

We acknowledge potential shortcomings of our research design. The most central limitation of this project relates to the one-time assessment of peer group victimization. Past research on the adult outcomes associated with victimization by peers has often relied on very similar designs, examining relations between victimization during a constricted period of childhood and later outcomes (e.g., Sourander et al. 2007). However, in the absence of a multi-wave assessment, we are unable to draw conclusions regarding trajectories and outcomes. We might also be in a stronger position to generate causal hypotheses (but not causal conclusions) if full cross-panel data were available. For now, we are restricted to a focus on aggression and victimization as interactive markers of later outcomes.

Our conceptualization of aggression and victimization as lead indicators of other difficulties also raises a number of concerns. We assessed peer group victimization during the middle years of elementary schools. At this point in development, the underlying mechanisms may have already begun to stabilize (as evidenced by the marked stability of conduct disorder in this project). Research targeting earlier stages of the lifespan could prove to be informative.

In further studies, it might also be worthwhile to consider wider implications for the hypothesized developmental processes. We suggested that victimization by aggression interactions would be indicative of impairments in self-regulation that paradoxically mitigate risk for arrest. It seems reasonable to suggest that such deficits would have implications for functioning in a wide array of academic, occupational, and interpersonal domains. The long-term studies that do exist, including the current project, focus largely on psychopathology, criminal outcomes, and personal distress. We currently know little about the implications of the examined social problems for adjustment in these central domains of adult life.

A final set of concerns relates to our arrest index. We conceptualized arrest as a dichotomous outcome, and we did not separately consider arrests for different types of crimes or arrest under specific sets of circumstances. Our goal was to capture trajectories toward serious criminal behavior that might result in arrest, and we did not have hypotheses that would lead to a more fine-grained operationalization of arrests (i.e., we did not separately consider arrests for different types of crimes or arrest under different kinds of circumstances). Given issues related to cell size, as well as concordance across indicators, analyses of this nature would also be limited by power issues and related concerns. These issues notwithstanding, arrest can occur under many different circumstances, and our global assessment may not fully capture the underlying dynamics.

In summary, our analyses offer a new perspective on children who are concurrently aggressive and victimized by their peers. We found evidence that high rates of victimization can be indicative of attenuated relations between aggression and later arrest. Existing theory, and empirical findings, have consistently portrayed aggressive victims as a high-risk subgroup. Nonetheless, the full pattern is complex with aggression and victimization interacting to predict unique outcomes.

Notes

As noted earlier in this paper, terminology and conceptualization vary across studies. Insofar as appropriate, we will describe existing findings using the categories and terminology relied on by the original researchers.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Barker, E. D., & Salekin, R. T. (2012). Irritable oppositional defiance and callous unemotional traits: Is the association partially explained by peer victimization? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1167–1175.

Cillessen, A. H. N., & Mayeux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75, 147–163.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722.

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371.

Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1994). Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development, 65, 649–665.

Graham, S., Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., & Juvonen, J. (2009). “It must be me”: Ethnic diversity and attributions for peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 487–499.

Hollingshead, W. (1979). The Hollingshead four factor index of sociometric status. Yale University: Unpublished paper.

Huesmann, L. R., Eron, L. D., & Dubow, E. F. (2002). Childhood predictors of adult criminality: Are all risk factors reflected in childhood aggressiveness? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 12, 185–208.

Ladd, G. W., & Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2002). Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, incidence of victimization, characteristics of identified victims, and estimation of relational adjustment. Psychological Assessment, 14, 74–96.

Lahey, B. B., Lee, S. S., Sibley, M. H., Applegate, B., Molina, B. S. G., & Pelham, W. E. (2016). Predictors of adolescent outcomes among 4–6-year-old children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 168–181.

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Zammit, S., & Wolke, D. (2015). Bully/victims: A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of their mental health. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 1461–1471.

Low, S., Polanin, J. R., & Espelage, D. L. (2013). The role of social networks in physical and relational aggression among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1078–1089.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behavior among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and their whipping boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Ostrov, J. M. (2010). Prospective associations between peer victimization and aggression. Child Development, 81, 1670–1677.

Patterson, G. R., Forgatch, M. S., Yoerger, K. L., & Stoolmiller, M. (1998). Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 531–547.

Pellegrini, A. D., Bartini, M., & Brooks, F. (1999). School bullies, victims, and aggressive victims: Factors relating to group affiliation and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 216–224.

Perry, D. G., Kusel, S. J., & Perry, L. C. (1988). Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology, 24, 807–814.

Perry, D. G., Perry, L. C., & Kennedy, E. (1992). Conflict and the development of antisocial behavior. In C. U. Shantz & W. W. Hartup (Eds.), Conflict in child and adolescent development (pp. 301–329). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Petersen, I. T., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Lansford, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2015). Describing and predicting developmental profiles of externalizing problems from childhood to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 791–818.

Piquero, A. R., & Brame, R. W. (2008). Assessing the race–crime and ethnicity–crime relationship in a sample of serious adolescent delinquents. Crime and Delinquency, 54, 390–422.

Schwartz, D. (2000). Subtypes of victims and aggressors in children’s peer groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 181–192.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1997). The early socialization of aggressive victims of bullying. Child Development, 68, 665–675.

Schwartz, D., McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Peer victimization as a predictor of behavior problems at home and in school. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 87–100.

Schwartz, D., McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Early behavior problems as a predictor of later peer group victimization: Moderators and mediators in the pathways of social risk. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 191–201.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2000). Friendship as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology, 36, 646–662.

Schwartz, D., Proctor, L. J., & Chien, D. (2001). The aggressive victim of bullying: Emotional and behavioral dysregulation as a pathway to victimization by peers. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), School-based peer harassment: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 147–174). New York: The Guilford Press.

Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2008a). Friendships with peers who are low or high in aggression as moderators of the link between peer victimization and declines in academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 719–730.

Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Duong, M. T., & Nakamoto, J. (2008b). Peer relationships and academic achievement as interacting predictors of depressive symptoms during middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 289–299.

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2013). The link between harsh home environments and negative academic trajectories is exacerbated by victimization in the elementary school peer group. Developmental Psychology, 49, 305–316.

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2015). Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 393–404.

Sourander, A., Jensen, P., Rönning, J. A., Niemelä, S., Helenius, H., Sillanmäki, L.,. .. Almqvist, F. (2007). What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish "from a boy to a man" study. Pediatrics, 120, 397–404.

Sourander, A., Brunstein Klomek, A., Kumpulainen, K., Puustjärvi, A., Elonheimo, H., Ristkari, T.,. .. Ronning, J. A. (2011). Bullying at age eight and criminality in adulthood: Findings from the Finnish Nationwide 1981 birth cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46, 1211–1219.

Toblin, R. L., Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., & Abou-Ezzeddine, T. (2005). Social-cognitive and behavioral attributes of aggressive victims of bullying. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 329–346.

Wolke, D., Copeland, W. E., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychological Science, 24, 1958–1970.

Zych, I., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2016). Empathy and Callous–Unemotional Traits in Different Bullying Roles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683456

Acknowledgements

The Child Development Project has been funded by grants MH56961, MH57024, and MH57095 from the National Institute of Mental Health, HD30572 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and DA016903 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J.E., Dodge, K.A. et al. Peer Victimization during Middle Childhood as a Marker of Attenuated Risk for Adult Arrest. J Abnorm Child Psychol 46, 57–65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0354-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0354-x