Abstract

Theoretical advances in the study of the development of aggressive behaviors indicate that parenting behaviors and child aggression mutually influence one another. This study contributes to the body of empirical research in this area by examining the development of child aggression, maternal responsiveness, and maternal harsh discipline, using 5-year longitudinal data from a nationally representative sample of Turkish children (n = 1009; 469 girls and 582 boys). Results indicated that: (i) maternal responsiveness and harsh discipline at age 3 were associated with the subsequent linear trajectory of aggression; (ii) reciprocally, aggressive behaviors at age 3 were associated with the subsequent linear trajectories of these two types of parenting behaviors; (iii) deviations from the linear trajectories of the child and mother behaviors tended to be short lived; and, (iv) the deviations of child behaviors from the linear trajectories were associated with the subsequent changes in mother behaviors after age 5. These findings are discussed in the cultural context of this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The prevalence of aggressive behaviors peaks around age 2 and declines thereafter (Tremblay 2000). It is well established, however, that some children’s developmental trajectories diverge from this norm (Campbell 2002). The current study is focused on parenting factors that may be associated with non-normative trajectories of aggressive behaviors in early childhood, between ages 3 and 7. We investigate the role of two proximate and dynamic factors that may be associated with the trajectories of overt aggression: trajectories of maternal responsiveness and maternal harsh discipline. These parenting behaviors have been identified as major predictors of aggressive behaviors in early childhood, and consequently have been targeted by numerous interventions (e.g., Smith et al. 2014). However, recent theoretical and empirical work has found that these parenting behaviors not only influence child aggression, but are also influenced by it, suggesting bidirectional processes. The aim of the current study is to contribute to the knowledge in this area by examining the development of child aggression, maternal responsiveness, and maternal harsh discipline, using 5-year longitudinal data from a nationally representative sample of Turkish children. It is the first study, to our knowledge, that simultaneously considers two types of parenting behaviors and child aggressive behaviors, using methods that allow the estimation of bidirectional associations of the trajectories of parent and child behaviors.

The years that precede school entry are particularly important for studying the developmental trajectories of aggression. At the time of school entry and during the early years of school, children who display high levels of aggression are likely to face substantial academic (e.g., grade failure) and social difficulties (e.g., peer rejection) that set them up for poor psycho-social outcomes later (Reef et al. 2010). Aggressive children also suffer poor relationships with their teachers that lead to academic failure, a lack of sense of school belonging, and achievement problems down the line (Patterson et al. 1992). Furthermore, children with high initial levels of aggression at school entry tend to remain more aggressive than their peers subsequently (Reef et al. 2010).

This study is also significant due to its large and representative sample from Turkey, a country located between Europe and the Middle East. The Turkish society has changed from a traditional and agricultural society to an industrial society during the last 70 years. Although the economic transformation was rapid, the cultural norms for family relationships lagged behind (Sunar and Fisek 2005). Based on Hofstede’s collectivism-to-individualism ranking, Turkey is 37th out of 93 countries (Hofstede et al. 2010), located closer to the collectivistic end of this distribution. On one hand, the normative socialization goals in Turkish culture value parental authority and obedience to family rules. These values are often associated with regular and widespread use of parental harsh discipline. On the other hand, family interdependency, and protective care and support of young children are valued, which are often associated with high levels of positive and responsive parenting (Kagitcibasi 1996). Indeed, previous studies documented that Turkish parents used high levels of intrusive and harsh strategies in disciplining their children, but also displayed a high level of positive behaviors (Akcinar and Baydar 2014; Kagitcibasi 1996).

Gender based division of responsibilities prevail in most Turkish families where few mothers work and few children attend preschool (OECD 2010). The current sample is no exception: 98% of children at age 3, 94% at age 4, and 91% at age 5 remained in maternal care, underscoring the overwhelming relative importance of maternal parenting in children’s socialization. In contrast, in the U.S., 53% of children at age 3, 32% at age 4, and only 6% at age 5 remained in care arrangements other than preschools or Kindergartens (OECD 2010). The social context of this study, therefore, provided an excellent opportunity to study the interdependent trajectories of two kinds of maternal parenting behaviors and child aggressive behaviors.

Processes that Link Parenting Behaviors with Child Aggressive Behaviors

Harsh parenting has been found to be associated with high initial levels and slow declines in aggression in different developmental periods (Prinzie et al. 2006). This positive association has been attributed to three processes. First, harsh discipline tends to induce fear that may interfere with a child’s capacity for behavioral and emotional regulation, and may prevent the development of social problem solving skills (Sheehan and Watson 2008). Second, harsh discipline may provide negative behavioral models to the child, in the face of stress, conflict, or frustration (Bandura 1977). Third, harsh discipline may result in escalating negative and aversive interactions between the mother and the child. This latter process suggests mutual influences between the negative behaviors of the mothers and the children.

The coercion theory (Granic and Patterson 2006), which offers a dynamic systems framework, posits that a demand by the mother may elicit an aversion from the child, which, in turn, may ward off further maternal demands, reinforcing the child’s negative response. Such exchanges will result in an escalation of the negative behaviors displayed by both the mother and the child. The cycle of ‘maternal demand- child aversion-maternal anger- child anger’ may lead to a consolidation of negativity, resulting in increasing likelihoods of maternal power assertion and aggressive responses by the child. Over time, alternative interaction patterns may become less frequent, and this coercive pattern may become dominant. The child, then, will learn to use negative strategies to achieve his or her goals. The mother, on the other hand, may become increasingly power assertive, in anticipation of the child’s resistance. Thus, the coercion theory posits (i) high aggression in response to high parental harsh discipline; (ii) high parental harsh discipline in response to high child aggression; and, (iii) infrequent positive responsive parenting behaviors as a collateral outcome of the consolidation of coercive interactions between the mother and the child.

Responsive parenting has been found to be associated with low levels of child aggression (Denham et al. 2000). Responsive behaviors of the mothers are likely to support the children’s capacity for regulation (Feng et al. 2008). Responsive parenting is also expected to provide positive behavioral models for children when they are upset, angry, or frustrated. Responsive and supportive interactions between the mother and the child also point to “multistability”, (i.e., alternative interaction patterns to coercive and hostile interactions, Granic and Patterson 2006). Hence, the presence of maternal responsiveness may signal a lower likelihood of escalation of harsh discipline and child aggression.

Intervention research has provided further empirical evidence to the link between parent and child behaviors. Parent training programs were found to be effective in reducing antisocial behaviors and aggression, especially in early childhood years (Reid et al. 2004). These findings support the hypothesis that increases in positive responsive behaviors and declines in harsh discipline by the mothers will be associated with a decline in aggressive behaviors of their children.

Transactional Associations between Mother and Child Behaviors

In the current study, we use a transactional conceptual framework. We posit mutually influential parent and child behaviors. Extant evidence about mutual influences between parenting behaviors and child aggression is mixed regarding whether the child behaviors contribute to the changes in parenting behaviors in early childhood. Among the studies that estimated cross-lagged associations with designs that included three or more time points of observation, none found significant child-to-parent associations prior to age 6 (Barnes et al. 2013; Berlin et al. 2009; Besnard et al. 2013; Villodas et al. 2015). Some studies that estimated transactional models with data extending to middle childhood found significant child-to-mother associations after 6 years of age (Besnard et al. 2013; Sheehan and Watson 2008). Two studies that found both significant mother-to-child and child-to-mother associations had only two time points of observation (Gershoff et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2013). Only one study found only child-to-mother associations but the model estimated in that study considered concurrent bidirectional associations rather than cross-lagged paths (Verhoeven et al. 2010).

Modeling of the Reciprocal Associations between Mother and Child Behaviors

Generally, data from several time points provide a strong design for detecting reciprocal associations between the behaviors of the mother and the child. Several different approaches to the modeling of longitudinal trajectories of child and parent behaviors have been proposed. Latent growth curve modeling (Gross et al. 2008), and autoregressive cross-lagged modeling (Besnard et al. 2013; Gershoff et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2013) have been used most frequently. These two models represent different processes of change. Latent growth curve modelling of mother-child behaviors do not allow the estimation of the variability of the strength of the association between the mother behaviors and the child behaviors over time. Similarly, they do not allow the estimation of developmental discontinuities in bidirectional associations. Cross-lagged models with autoregressive components do not allow the modeling of proportionate changes in a time series of developmental measures. Without this self-feedback component, the model usually requires a complex autoregressive structure for an acceptable fit. Furthermore, cross-lagged models do not quantify age-related trends.

The model that we use in the current research is an augmented dual latent change score model. Dual latent change score models have a latent growth component and a latent change component (Ferrer and McArdle 2003; McArdle 2009). We present an augmented model that combines three parallel dual latent change score models (i.e., a trivariate dual latent change score model). While bivariate versions of these models have been used before, this is the first study that we know of, that adapted the basic dual latent change score model to quantify reciprocal associations between three longitudinal processes simultaneously, including child aggression, and two types of maternal behaviors. Our model quantifies the association of each type of parenting behaviors with subsequent changes in the child behaviors, and the association of child behaviors with the subsequent changes in both types of parenting behaviors. As such, we are able to test which of the three processes (i.e., child aggressive behaviors, maternal harsh discipline, or maternal responsiveness) may be a leading indicator of change in the others, at any given age interval. Our model also incorporates the concurrent associations of the mother and child behaviors that may be due to reasons other than reciprocal causation (e.g., a change in the environment such as a new sibling, or a move to a new neighborhood). The concurrent associations were omitted from some previous autoregressive cross-lagged models, which could have led to inflated estimates of the transactional associations (Fite et al. 2008; Verhoeven et al. 2010). Furthermore, the latent change score model includes a self-feedback process where change in each measure is proportionate to its initial value. Proportionate changes are effective in representing the trajectories of change for individuals who have very high or very low scores (Ferrer and McArdle 2010).

The Current Study

This study has a three-fold contribution to the literature. First, the development of child aggressive behaviors is investigated during the critical years that span the transition to school. Second, the dynamic, transactional associations between maternal harsh discipline and maternal responsiveness with child aggressive behaviors are modeled simultaneously, using recently developed statistical methods. Third, using data from a large representative sample from a collectivistic culture, we test transactional hypotheses derived from the developmental theories that have rarely been tested in samples other than North American and Western European samples.

In line with the previous research, we expect the trajectories of parenting behaviors and child aggressive behaviors to have considerable inter-individual variation that are interdependent. A high level of maternal harsh discipline, and increases in maternal harsh discipline are expected to be associated with increases in subsequent aggressive behaviors. Based on the coercion theory, we also expect that high levels of child aggression and increases in child aggression will be associated with subsequent increases in maternal harsh discipline.

There is a lack of empirical studies investigating the association of child aggression with subsequent trajectories of maternal responsiveness (for exceptions, see Besnard et al. 2013; Serbin et al. 2015; Verhoeven et al. 2010). Changes in maternal responsiveness following a high level of child aggression may be due to two reasons. First, the mothers may respond in a way that is consistent with what much intervention research suggests: by increasing maternal responsiveness in order to support a decline in child aggressive behaviors (by encouraging regulation and by modeling positive responses to negative situations). At the same time, increases in child aggression may trigger a decline in responsiveness because of increasing maternal anger leading to harsh and coercive maternal behaviors that consolidate in negative mother-child interactions to the exclusion of responsiveness (see above). Because of this consolidation of negative mother and child behaviors, we expect that a high level of maternal harsh discipline will be associated with a decline in maternal responsiveness.

We included some covariates in our models. Child reactivity was included to control for potential child effects on parenting that could be due to dispositional characteristics and because of its strong association with both child aggression and parenting behaviors (Farbiash et al. 2014). Similarly, socioeconomic status (SES) was included as a control because it was linked with harsh discipline, responsiveness, and child aggressive behaviors (Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997). We also included child gender in our models, to account for the higher levels of aggression in boys than in girls (Prinzie et al. 2006).

Method

Sample and Procedure

The data were obtained from the Early Childhood Developmental Ecologies study, a 5- year longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of children in Turkey. The data were collected through in-person interviews with the mothers and observations of mother-child interactions. The interviewers were trained by the researchers to conduct the observations during the home visits that lasted 2–3 h. Observational data were recorded by the interviewers at the completion of the home visits. The age of the child (36–47 months) and the mother’s ability to speak sufficient Turkish to respond to the survey protocol determined the eligibility of the participants. The sample was a stratified cluster sample with selection probabilities at each stage proportional to the population size. The analyses presented here used data collected annually from the same sample between ages 3–7. The adult participants were the mother figures, who were the biological mothers in all cases except for seven children who were cared for by their grandmothers. The sampling procedure and the representativeness of the sample were discussed elsewhere (Baydar and Akcinar 2015). The analyses presented here used a sample of 1009 mother-child dyads, eliminating 43 dyads who provided inadequate information on basic demographic variables. The sample sizes for each of the subsequent four waves were 879, 837, 786 and 762, respectively.

Measures

Children’s aggressive behaviors, about half of the items pertaining to the parenting behaviors, a majority of the indicators of SES, children’s reactivity, and children’s sex were reported by the mothers. Another half of the items on parenting behaviors and two of the SES indicators were reported by the trained observers. All measures were scaled to range between 0 and 100, except for SES and child sex. The distributions of all measures were examined. The outliers were trimmed. The only measure that had substantial skewness was maternal harsh discipline.

Child Aggressive Behaviors

This measure consisted of a subset of the items of the Turkish adaptation of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI-TR). The ECBI (Eyberg and Robinson 1983) consisted of 36 items describing potentially problematic behaviors. The ECBI-TR was adapted for use with Turkish mothers through translation and back translation (Batum and Yağmurlu 2007). The frequencies of occurrence of behaviors were rated on 5-point scales instead of the original 7-point scales, to facilitate comprehension and reliable reporting by participants who had low levels of education. The psychometric properties of the ECBI-TR were also established with the current representative sample (Baydar and Akcinar 2015). The factor analyses with the current sample suggested the presence of three subscales similar to the original version of the ECBI (Burns and Patterson 2000). Here, we used the 9-item aggressive behaviors intensity scale (e.g., “Fights with peers”, “Hits parents”; α = 0.80 to 0.93 for ages 3–7). This scale measured both proactive and reactive overt aggression. The variance accounted for by the first factor of the nine aggression items for each age were 38.7%, 45.2%, 45.7%, 39.9%, and 43.0% for the ages 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively. At age 3, additional data on externalizing behaviors were available for a subsample of children who participated in an observational protocol (n = 123), and these data were used to further validate the ECBI-TR aggression measure. Observed child behaviors were coded using the Dyadic Parent-Child Coding System (DPICS) and the Coder Impression Inventory (CII; Akcinar and Baydar 2014). The ECBI-TR aggression scores were significantly correlated with the DPICS and CII measures of child conduct problems (r = 0.31, p = 0.00, and r = 0.29, p = 0.00, respectively).

The mean levels of aggression in the current study were in agreement with the reported means of aggression items of two published standardization samples (Colvin et al. 1999; Reedtz et al. 2008). These comparisons were made after converting the aggression scores to percentage scores of the maximum possible point totals. Age specific clinical cutoff scores for the ECBI were not available for the subscales. We must, therefore, cautiously interpret the estimated proportion above the clinical cutoff in the study sample because the published cutoff scores were based on data from older standardization samples. Based on the total ECBI intensity score, 11.7% of 7 year-old children in the current study sample were in the clinical range (Colvin et al. 1999).

Parenting Behaviors

We used measures of two types of parenting behaviors: maternal harsh discipline and responsiveness. Five consecutive annual assessments based on maternal and observer reports were available. The Turkish adaptation of the Child Rearing Questionnaire (CRQ) was used for mother report items, and the Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment (HOME-TR) was used for mother and observer report items.

The original CRQ (Paterson and Sanson 1999) and its Turkish adaptation (CRQ-TR; Yağmurlu and Sanson 2009) consisted of 30 self-report items on the frequency of specific parenting behaviors. It had four subscales: obedience demanding behavior, punishment, parental warmth, and inductive reasoning. A version of the HOME scales that was developed for large scale studies was used (Bradley et al. 2001). Observational data were collected by the interviewers who were trained by the research team. The interviewers observed the maternal behaviors and mother-child interaction during the home visits that lasted 2–3 h. The interviewers reported the HOME items at the end of the home visits, prior to departing.

The early childhood (ages 3–5, 52 items) and middle childhood (ages 6–7, 56 items) versions of HOME -TR were adapted for this research (Baydar and Akcinar 2010; Baydar and Bekar 2007). The items were modified to render them relevant to the living conditions of the Turkish children (R. H. Bradley, personal communication, May 20, 2008). Each item equally contributed to the total score, regardless of its rating scale. In other words, each item’s score was rescaled so that its score would vary between 0 and 1. The mean of these items was then expressed as a percentage of the total point score. If the majority of the items of a scale was missing, then the scale score was not computed.

Harsh Discipline

This scale was from HOME-TR, and had 6 items for ages 3–5 and 5 items for ages 6–7. Three of the six items in the early childhood version and one of the five items in the middle childhood version were reported by the observers (e.g., “Mother hit, slapped or otherwise physically punished the child”; α between 0.60 and 0.65 for 5 years). Unfortunately each home visit was conducted by a single observer. Hence inter-observer reliabilities were not available. For the current study, maternally reported open-ended items that elicited the description of types of responses mothers gave to various undesirable behaviors of her child were coded to indicate harsh responses only.

Maternal Responsiveness

A combined measure of responsiveness was constructed that had identical 12 items for all five time points (α between 0.71 and 0.79 for the 5 years of data). In the resulting scale, five items came from the CRQ-TR (e.g., “I try to soothe my child, when s/he feels sad or scared”). There was one maternally reported item from the HOME-TR (“How often do you take the child to outings that are planned specifically for his/her enjoyment”), and the remaining six items were reported by the observers (e.g., “The mother listens to the child and encourages him/her to speak”).

Reactivity

Child reactivity was measured at age 3, with the 9-item reactivity subscale of the 30-item Short Temperament Scale for Children (Prior et al. 1989). For the Turkish adaptation of this measure (Yağmurlu and Sanson 2009), the rating scale was revised to a 5-point scale. A sample item is “When (s)he opposes something such as brushing her/his hair, this resistance can go on for months” (α = 0.75). At low and normative levels, reactivity was not associated with child aggression. We therefore dichotomized reactivity with a cutoff score of 60 (M = 49.2, SD = 16.5).

SES

A factor score (M = 0, SD = 1) was calculated on the basis of age 3 measures of maternal education, paternal education, and a composite measure of family economic well-being. The latter measure itself was a factor score that combined a measure of the material possessions of the family (e.g., a car, a dishwasher, a computer), the monthly per person expenditures of the household, the actual or estimated value of the family residence, and the physical quality of the home and the neighborhood environments reported by the observer (Baydar et al. 2014).

Statistical Methods

We used multivariate dual latent change score models (Ferrer and McArdle 2003) to quantify the reciprocal associations of changes in aggression with the changes in the two types of parenting behaviors. All analyses were conducted with MPLUS version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) and missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood. First, we investigated whether the trajectories of aggression and parenting behaviors could be represented with a simple proportional change model. When this model did not yield an adequate fit to the observed data, we estimated a dual latent change score model that included both a component of a latent linear trajectory, and a component of proportional changes between consecutive observations. These models (i) characterize a linear trajectory of change that describes a latent developmental trend; and, (ii) allow the modeling of deviations from that trend both due to earlier deviations, and due to exogenous factors. The adequacy of the models of change were assessed using the goodness of fit statistics. In order to assess the impact of the skewness of one of our measures, maternal harsh discipline, on the estimated coefficients of the models, we re-estimated the final model with robust maximum likelihood. The estimates were not appreciably different from the maximum likelihood estimates.

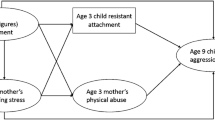

Following the estimation of the univariate dual latent change score models, we estimated a trivariate model where reciprocal associations between the child and parenting behaviors were estimated. Specifically, the variables measuring parenting behaviors could predict both the linear trajectory of aggression and the deviations from this trajectory. Reciprocally, the measures of aggression could predict both the linear trajectory of harsh punishment and responsiveness, and the deviations from these trajectories. Figure 1 depicts the trivariate dual latent change score model. To our knowledge, bivariate latent change models have been estimated (e.g., Dogan et al. 2010; Kouros and Garber 2010) but this is the first trivariate dual latent change score model that tests hypotheses about reciprocal associations between more than two longitudinal processes.

In the model depicted in Fig. 1, each parenting behavior at age 3 was associated with the slope of the subsequent latent trajectory of child aggressive behaviors, and the slope of the latent trajectory of the other parenting behavior. Similarly, age 3 child aggressive behaviors were associated with the slopes of the latent trajectories of harsh and responsive parenting behaviors. Furthermore, parenting behaviors at any age T could predict the change in aggression between T and T + 1. Reciprocally, child aggressive behaviors at any age T could predict the change in harsh and responsive parenting behaviors between T and T + 1. Thus, both a latent linear trend in aggressive behaviors, and the deviations from this trend throughout early childhood were modeled.

The resulting trivariate dual latent change score model was difficult to interpret because of the complexity of the factors that contributed to aggressive behaviors at each age. For example, the aggressive behaviors at age 7 were associated with the parenting behaviors at age 3, aggression at age 3, and interim deviations from the latent trajectory of aggression that were associated with the interim deviations of the two parenting behaviors from their respective latent trajectories. In order to facilitate the interpretation of the model, we plotted the predicted trajectories of aggressive behaviors under various scenarios.

Results

Table 1 compares the characteristics of the children and their families who were lost to follow-up (n = 249) with those who had complete data (n = 760). Those who were lost to follow-up had higher family SES, higher maternal education, lower birth order, and were of slightly younger age than the others. High SES could imply a high rate of mobility for young families, resulting in higher rates of attrition than others. The attrited sample was not different from those who were retained in terms of child gender, maternal age, child aggression, child reactivity, and any of the parenting behaviors considered here.

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics and correlations of the study variables. The mean trajectory. Among the children who had higher gradually declined over early childhood from a mean of 37.2 (SD = 19.5) at age 3 to a mean of 20.7 at age 7 (SD = 17.7). This decline was monotonous, except for the ages 5 to 6. Maternal harsh discipline also increased between ages 5 and 6, by about 0.20 SD. There was no discernible trend in the mean values for maternal responsiveness.

The autocorrelations between the aggression scores were around 0.5 for one year lags, and 0.4–0.5 for two year lags, very similar to other studies (e.g., Lee et al. 2013). Autocorrelations between harsh discipline measures were modest (0.2–0.3) probably because observer reports could be influenced by situational factors specific to the time of the visit. Autocorrelations between responsive parenting measures were around 0.3–0.4. Taken together, these autocorrelations suggest that the mother-child relationships could undergo substantial changes between ages 3–7.

Cross-domain correlations revealed much stronger associations of aggression with harsh discipline than with responsiveness. At age 3, the correlation between harsh discipline and responsiveness was −0.1, indicating that at this age, one type of parenting behavior did not predict the other. Starting at age 4, concurrent correlations between the use of harsh discipline and responsive parenting were negative and in −0.3 to −0.4 range, suggesting a tendency to display harsh or responsive behaviors. However, substantial proportions of the mothers displayed high or low levels of both harsh discipline and responsiveness concurrently. For example, 21.7% of the mothers at age 4, 21.1% of the mothers at age 5, and 29.1% of the mothers at age 6 had both harsh discipline and responsiveness scores that were above the median.

Reciprocal Associations between Aggressive Behaviors, Harsh Discipline, and Responsiveness

The trivariate model depicted in Fig. 1 was built in four steps. First, univariate models of change were tested. For all three trajectories of interest, the univariate proportional change models resulted in extremely poor fit indicators: χ2(6) = 262.7, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.202, 95% CI [0.181, 0.223], CFI = 0.78, SRMR = 0.140 for aggressive behaviors; χ2(6) = 84.9, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.112, 95% CI [0.091, 0.134], CFI = 0.77, SRMR = 0.079 for harsh discipline; and, χ2(6) = 211.9, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.181, 95% CI [0.160, 0.201], CFI = 0.70, SRMR = 0.133, for responsiveness.

Next, univariate dual change models were estimated for each of the observed trajectories. These models included an underlying linear trajectory, in addition to latent proportional changes between observations. The dual latent change score models resulted in satisfactory fits for all three trajectories: χ2(4) = 6.5, p = 0.16; RMSEA = 0.025, 95% [CI 0.000, 0.057], CFI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.014 for aggressive behaviors; χ2(4) = 11.4, p = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.042, 95% [CI 0.014, 0.072], CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.023 for harsh discipline; and, χ2(4) = 6.8, p = 0.15; RMSEA = 0.026, 95% CI [0.000, 0.058], CFI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.020 for responsiveness. In all three models, the estimated linear slopes, their variances and the coefficients of proportional change (from now on labeled autoproportion coefficients) were significant. The autoproportion coefficients were large and negative, decelerating positive growth and dampening the deviations from the trajectories.

At the third step, the univariate dual latent change models were combined into a trivariate model that included transactional associations between aggressive behaviors and parenting behaviors (Fig. 1). This model had a good fit, χ2(53) = 113.4, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.033, 95% CI [0.025, 0.041], CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.032. In order to obtain a parsimonious model, the autoproportion coefficients were constrained to be equal for each one of the three trajectories, Wald χ 2(9) = 15.9, p = 0.07.

At the final step, age 3 measures, and each of the latent change scores were regressed on the three covariates: SES, child gender, and child reactivity. The estimated coefficients of this trivariate dual latent change model are given in Tables 3 and 4. The findings from the underlying linear trend components of the trivariate model are presented first, followed by the findings from the latent change score components. The standardized coefficients are presented in Fig. 1.

The trivariate model presented in Tables 3 and 4 yielded a highly satisfactory fit, χ2(64) = 118.5, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.028, 95% CI [0.020, 0.036], CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.024. The proportions of variance in the latent slopes that were accounted for by the model were 8.5% for aggressive behaviors, 7.4% for responsiveness, and 23.1% for harsh discipline. The proportions of variance in latent change variables (deviations from the trajectories) that were accounted for by the model were high. The model accounted for an average of 49.8% of the variance of the deviations in aggressive behaviors, ranging from 47.2% to 55.0%. The comparable average proportions of variance in deviations that were accounted for by the model were 48.9% for responsiveness, and 44.8% for harsh discipline.

As expected, harsh discipline at age 3 was significantly positively associated with the slope of aggressive behaviors, B = 0.166, β = 0.313, p = 0.00. Reciprocally, aggressive behaviors at age 3 were significantly positively associated with the slope of maternal harsh discipline, B = 0.136, β = 0.447, p = 0.00, pointing to a transactional process. Maternal responsiveness at age 3 was significantly negatively associated with the slope of aggressive behaviors, B = −0.075, β = −0.128, p = 0.01. However, the reciprocal association of aggressive behaviors at age 3 with the slope of maternal responsiveness was not significant, B = −0.033, β = −0.103, n.s. Furthermore, harsh discipline at age 3 was negatively associated with the slope of responsiveness, B = −0.087, β = −0.222, p = 0.00, and responsiveness at age 3 was negatively associated with the slope of harsh discipline, B = −0.041, β = −0.126, p = 0.04.

Covariances were specified to account for the association of the intercept and the slope of each trajectory. These covariances were significant and positive (correlations of 0.438, 0.356, and 0.351, for aggression, harsh discipline, and responsiveness, respectively) indicating a steeper slope when the age 3 observation was higher. Note that these steep slopes were attenuated by the autoproportion components, as described below.

The large negative autoproportion coefficients of the trivariate model (Table 4, the first three columns) indicated that large deviations from the linear trajectories self-corrected, underscoring the relative importance of the underlying linear trends. Few of the parameters quantifying the cross-domain associations were significant. A high level of harsh discipline at age 4 was associated with an increase in aggressive behaviors between the ages of 4 and 5, B = 0.132, β = 0.099, p = 0.00. No other cross-domain associations were significant for the ages 3–4, and 4–5. A high level of aggressive behaviors at age 5 was associated with an increase in harsh discipline, B = 0.124, β = 0.111, p = 0.00, and an increase in responsiveness, B = 0.126, β = 0.121, p = 0.00 between the ages of 5 and 6. A high level of aggressive behaviors at age 6 was also associated with a subsequent modest increase in responsiveness, B = 0.070, β = 0.064, p = 0.03. Although these transactional path coefficients were statistically significant, they were substantially smaller than the autoproportion coefficients by many orders of magnitude. For example, the largest cross-domain path coefficient, which was estimated for the association of aggressive behaviors at age 5 with the subsequent change in responsiveness, was one-seventh of the size of the autoproportion coefficient for aggressive behaviors.

The combined outcomes of the underlying linear trend and the proportional change components of the trivariate model are depicted in Figs. 2 and 3. “Low” and “high” values were defined by a SD below and a SD above the means of the measures. Children who had aggressive behavior scores, responsiveness, and harsh discipline that were 2 SD’s apart at age 3, were expected to have aggressive behavior scores that were still 1 SD apart at age 7, despite a strongly self-correcting trajectory due to the large negative autoproportion coefficients (Fig. 2). Differences in the predicted trajectories of aggressive behaviors associated with the differences in parenting behaviors are depicted in Fig. 3, for low and high levels of responsiveness and harsh discipline. For a trajectory that starts with a mean level of aggressive behaviors at age 3, four trajectories were estimated. When age 3 maternal responsiveness was low and harsh discipline was high, aggressive behaviors at age 7 were 0.28 SD higher than the case when age 3 maternal responsiveness was high and harsh discipline was low.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to quantify the roles of maternal responsiveness and harsh discipline in predicting the trajectories of aggressive behaviors while accounting for the reciprocal associations between the child and maternal behaviors. We simultaneously modeled the unfolding trajectories of child aggression, maternal harsh discipline, and responsiveness. Our conceptual model and hypotheses were based on the premises of the social learning and the coercion theories. We used 5-year longitudinal data from a nationally representative sample of children from Turkey. During the ages of 3 to 7, the mean level of aggressive behaviors steadily declined except for ages 5 and 6. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the decline in about one-quarter of the children’s aggressive behaviors was delayed, resulting in the observed fluctuation in age-specific means. These children were likely to be boys, of low SES, and had high reactivity.

In this sample, only a small percentage of children attended non-maternal care or school prior to age 6. Because of minimal non-family influences on child behaviors, we expected that the reciprocal associations of maternal and child behaviors would be strong. Furthermore, because of the characteristics of the Turkish culture (hierarchical and collectivistic), this sample included mothers who used high levels of harsh discipline and those who had high levels of responsiveness, allowing sufficient variability in the trajectories of both types of parenting behaviors.

Our model included two types of transactional associations between parenting behaviors and child behaviors: (i) maternal and child behaviors at age 3 were reciprocally associated with the slopes of the subsequent trajectories of these behaviors (the latent trajectory components of the model); and, (ii) maternal and child behaviors were reciprocally associated with the subsequent changes in these behaviors (the latent change score components of the model). The implications of the results of these two components of the model must be interpreted together.

Harsh discipline at age 3 was positively associated with the slope of the linear trajectory of aggressive behaviors during the following 4 years, and maternal responsiveness at age 3 was positively associated with that slope. These findings are consistent with the proposed process: harsh discipline provides a negative behavioral model and inhibits the acquisition of regulatory skills (Bandura 1977; Sheehan and Watson 2008), and responsiveness provides a positive behavioral model and facilitates regulation (Feng et al. 2008). The strong association of the maternal behaviors at age 3 with the trajectory of child behaviors during the following 4 years may be partly due to the continuity of the mother-child interactions in early childhood in this sample, with little interruption and little outside influence. The association of harsh discipline at age 3 with the trajectories of aggressive behaviors was 3.5 times the size of the comparable association of responsiveness with the trajectories of aggressive behaviors.

Previous studies indicated that the mothers in this cultural context were more obedience oriented (Kagitcibasi 1996) and more controlling (Akcinar and Baydar 2016) than the mothers in Western samples, resulting in a higher prevalence of harsh discipline. The use of harsh discipline was not confined to a subgroup in this sample, as evidenced by its undifferentiated use among all SES groups except for the families in the top 20th percentile. The non-stigmatized widespread use of harsh discipline may have allowed it to be measured without substantial underreporting. These conditions also likely yielded a high statistical power when estimating the association of harsh discipline with child aggression.

Not only that the association of harsh discipline with the slope of subsequent aggressive behaviors was stronger than that of responsiveness, but reciprocally, aggressive behaviors at age 3 was positively associated with the slope of maternal harsh discipline, but was not associated with the slope of responsiveness. These findings are consistent with the premises of the coercion theory (Granic and Patterson 2006). Accordingly, child aggressive behaviors and maternal harsh discipline directly influence each other because one occurs in response to the other. In contrast, the link between child aggression and maternal responsiveness is indirect. Coercion theory posits that the consolidation of the negative interactions between the mother and the child results in a decline in their positive interactions due to the formation of “attractor” states. Positive interactions, on the other hand, are expected to marginally slow down the escalation of negative interactions only because they offer an alternative attractor state. Indeed, in the current study, the negative association of age 3 harsh discipline with the slope of responsiveness was negative and 1.7 times stronger than the association of age 3 responsiveness with the subsequent slope of harsh discipline.

We found few statistically significant transactional associations beyond those embedded in the prediction of the long term trajectories. Any transactional associations estimated by the model were many orders of magnitude smaller than the autoproportionate associations. Before age 5, only a positive deviation in harsh discipline between the ages of 4 and 5 moderately predicted an increase in aggression at age 5. This pattern is in agreement with the previous research with strong longitudinal designs (Barnes et al. 2013; Berlin et al. 2009; Besnard et al. 2013; Villodas et al. 2015). An emergence of child-to-mother associations at the end of early childhood may be due to increasing peer influences and autonomy at that time.

We found that a high level of aggressive behaviors at age 5 was associated with increases not only in harsh discipline but also in responsiveness between the ages of 5 and 6. Although these associations were modest in strength, this finding was surprising. Coercion theory suggests otherwise: a high level of aggression may be associated with an increase in maternal harsh discipline, but not responsiveness (Granic and Patterson 2006). In order to shed light on this finding, we conducted post-hoc analyses. We found that some mothers increased harsh discipline, some mothers increased responsiveness, and very few increased both, following a high level of child aggression at age 5 that deviated from the underlying trajectory. Among the children who had higher than expected aggressive behaviors at age 5 (standardized residual > 0.5, n = 257, 24.4%), 18.3% (n = 47) had mothers whose harsh discipline increased by age 6 (standardized residual > 0.5), 26.1% (n = 67) had mothers whose responsiveness increased by age 6 (standardized residual >0.5), and only 5.4% (n = 14) had mothers who increased both types of parenting behaviors. Furthermore, the mothers who responded with an increase in harsh discipline were significantly more likely to be of low SES than those who responded with an increase in responsiveness, F(3234) =2.7, p = 0.05. The mothers with the two distinct response patterns following an increase in child aggression did not differ in their children’s gender or reactive temperament. Taken together, these findings suggest that the families in stressful circumstances may be vulnerable to the escalation of the cycle of negative interactions as predicted by the coercion theory.

Two important policy implications of this research must be highlighted. The first implication pertains to the timing of the interventions for the prevention of aggressive behaviors. Our findings show that by age 3, the negative behaviors of the mothers and their children strongly and mutually predict their negative behaviors in the following 4 years, spanning the transition to school. This finding supports the view that early interventions targeting the reduction of aggressive behaviors may be more effective than those for school ages or later. Integrative reviews of parenting interventions for early childhood behavior problems have also underscored the importance of early prevention and intervention (e.g., Shepard and Dickstein 2009). One of the few studies that specifically estimated the age differences in the effectiveness of a parenting intervention showed that parenting intervention effectiveness was nearly zero for 6 year-old children (Gardner et al. 2010). This policy implication may be particularly significant for the cultural context of the current study where very few children receive non-maternal care, and established patterns of interaction by age 3 have a high probability of being perpetuated.

The second policy implication pertains to the insight that could be gleaned from the relative roles of the two components of the longitudinal model (latent trajectory and the latent change score components) for these data. Note that an intervention in parenting behaviors or child aggressive behaviors could be represented in this model as a “deviation” from the underlying linear trajectory, similar to the latent change score component. The results showed that, under naturalistic conditions, the ultimate consequences of these deviations for the long term trajectories were limited. Hypothetically, an effective and long-term intervention could result in a large and sustained “deviation”, which could be larger than those observed in naturalistic circumstances. Nevertheless, the individually varying latent developmental trajectory accounted for much of the patterns of development between ages 3 and 7, indicating that following an intervention, there would be a tendency for the aggressive behaviors to return to a level that was largely predicted by this trajectory. The findings of our analyses, therefore, could contribute to the understanding of lower long-term effectiveness of the interventions than their short-term effectiveness, especially after age 3, when most of the interventions are implemented. Indeed, a study of the effectiveness of a parenting intervention in infancy versus ages 2–3 on social behavior found that only the intervention in infancy was effective in predicting changes in social behaviors of the children (Landry et al. 2008).

Our study has some weaknesses that must be considered. First and foremost, the data on children’s aggression and many of its predictors are maternally reported. The parenting measures include both maternal and observer reports, but none of our measures are exclusively from an independent informant. We addressed this deficiency to some extent, by including cross-sectional, time specific covariances in the model.

Second, our focus is on maternal behaviors. Our sample is one where almost all mothers are married and residing with the biological fathers of the children. By studying maternal parenting, one could only gain a partial view of family processes in the development of children’s aggression. The current sample is from a patriarchal culture where a gender based division of household responsibilities prevail (Kagitcibasi and Ataca 2005). The fathers have a limited role in the day-to-day caring of young children. Nevertheless, the association between the fathers’ involvement in discipline and their children’s aggression remains to be investigated.

Third, our sample experienced some selective attrition. Specifically, families with high SES were more likely to drop out of the study. We implemented full information maximum likelihood to impute missing data when we estimated dual latent change score models. This approach provides unbiased estimates of the model parameters when variables that are associated with attrition are included in the model. Nevertheless, the estimated parameters of the model that quantify the associations of the mother and child behaviors in later years may have represented the processes in low SES families more closely than in high SES families.

Fourth, there may be concern that the latent change score component of the model may be negatively impacted by the issue of low reliability of change scores. If multiple measures of parenting and child behaviors were available, measurement errors could be explicitly modeled. With single indicators, the modeling of measurement errors require assumptions that may be untenable (e.g., that the error variances are equal across ages). We chose not to model the error variances, hence our estimates may be subject to low statistical power. Nevertheless, in multivariate models, the estimated associations of the exogenous variables with the change scores were found to be relatively robust with respect to the variance of the measurement errors (Allison 1990; Edwards 2001).

We presented a model that linked the trajectories of mothers’ parenting behaviors to the trajectories of children’s aggression. The availability of nationally representative longitudinal data from early childhood, from a cultural context that strongly differs from the Anglo-American context is an important strength of this study. We estimated a comprehensive empirical model exploiting these data. Our model is grounded in the theories of development of aggression and has the distinction of including the transactional associations between maternal harsh discipline, maternal responsiveness, and child aggression, simultaneously. It also explicitly quantifies and models changes in aggressive behaviors. The overwhelming importance of maternal harsh discipline as the factor that is 3.5 times more strongly associated with the trajectories of aggressive behaviors than maternal responsiveness, suggests that this parenting behavior is detrimental even in societies where harsh discipline is the norm. Furthermore, high levels of maternal responsiveness are not strongly associated with declines in harsh discipline. Taken together, these results call for a sustained focus on harsh discipline for policy development targeting the reduction of school-age aggression in diverse cultural contexts.

References

Akcinar, B., & Baydar, N. (2014). Parental control is not unconditionally detrimental for externalizing behaviors in early childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 118–127.

Akcinar, B., & Baydar, N. (2016). Development of externalizing behaviors in the context of family and non-family relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1848–1859. doi:10.1007/s10826-016-0375016-0375-z.

Allison, P. D. (1990). Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. Sociological Methodology, 20, 93–114.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Barnes, J. C., Boutwell, B. B., Beaver, K. M., & Gibson, C. L. (2013). Analyzing the origins of childhood externalizing behavioral problems. Developmental Psychology, 49, 2272.

Batum, P., & Yağmurlu, B. (2007). What counts in externalizing behaviors? The contributions of emotion and behavior regulation. Current Psychology: Developmental-Learning- Personality- Social, 25, 272–294.

Baydar, N., & Akcinar, B. (2010). Middle childhood HOME-TR observation and interview scales. Unpublished Manuscript. Retrieved from http://portal.ku.edu.tr/~ECDET/index.htm.

Baydar, N., & Akcinar, B. (2015). Ramifications of socioeconomic differences for three year old children and their families in Turkey. Early Child Research Quarterly, 33, 33–48.

Baydar, N., & Bekar, O. (2007). Early childhood HOME-TR observation and interview scales. Unpublished Manuscript. Retrieved from http://portal.ku.edu.tr/~ECDET/index.htm.

Baydar, N., Küntay, A. C., Yagmurlu, B., Aydemir, N., Cankaya, D., Göksen, F., & Cemalcilar, Z. (2014). “it takes a village” to support the vocabulary development of children with multiple risk factors. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1014.

Berlin, L. J., Ispa, J. M., Fine, M. A., Malone, P. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Brady-Smith, C., et al. (2009). Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income white, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development, 80, 1403–1420.

Besnard, T., Verlaan, P., Davidson, M., Vitaro, F., Poulin, F., & Capuano, F. (2013). Bidirectional influences between maternal and paternal parenting and children's disruptive behaviour from kindergarten to grade 2. Early Child Development and Care, 183, 515–533.

Bradley, R. H., Corwyn, R. F., Burchinal, P., McAdoo, H. P., & Garcia-Coll, C. (2001). The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Development, 72, 1844–1867.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children, 7, 55–71.

Burns, G. L., & Patterson, D. R. (2000). Factor structure of the eyberg child behavior inventory: a parent rating scale of oppositional defiant behavior toward adults, inattentive behavior, and conduct problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 569–577.

Campbell, S. B. (2002). Behavior problems in preschool children; Clinical and developmental issues (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

Colvin, A., Eyberg, S. M., & Adams, C. D. (1999). Restandardization of the eyberg child behavior inventory. Retrieved from: www.pcit.org.

Denham, S., Workman, E., Cole, P., Weissbrod, C., Kendziora, K., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2000). Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: the role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 23–45.

Dogan, S. J., Stockdale, G. D., Widaman, K. F., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Developmental relations and patterns of change between alcohol use and number of sexual partners from adolescence through adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1747.

Edwards, J. (2001). Ten difference score myths. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 265–287.

Eyberg, S., & Robinson, E. A. (1983). Conduct problem behavior: standardization of a behavioral scale with adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 12, 347–354.

Farbiash, T., Berger, A., Atzaba-Poria, N., & Auerbach, J. G. (2014). Prediction of preschool aggression from DRD4 risk, parental ADHD symptoms, and home chaos. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 489–499.

Feng, X., Shaw, D. S., Kovacs, M., Lane, T., O'Rourke, F. E., & Alarcon, J. H. (2008). Emotion regulation in preschoolers: the roles of behavioral inhibition, maternal affective behavior, and maternal depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 132–141.

Ferrer, E., & McArdle, J. (2003). Alternative structural models for multivariate longitudinal data analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 493–524.

Ferrer, E., & McArdle, J. J. (2010). Longitudinal modeling of developmental changes in psychological research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 149–154.

Fite, P. J., Colder, C. R., Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2008). Developmental trajectories of proactive and reactive aggression from fifth to ninth grade. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 412–421.

Gardner, F., Hutchings, J., Bywater, T., & Whitaker, C. (2010). Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 568–580.

Gershoff, E. T., Lansford, J. E., Sexton, H. R., Davis-Kean, P., & Sameroff, A. J. (2012). Longitudinal links between spanking and children’s externalizing behaviors in a national sample of white, black, Hispanic, and Asian American families. Child Development, 83, 838–843.

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: a dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113, 101.

Gross, H. E., Shaw, D. S., Moilanen, K. L., Dishion, T. J., & Wilson, M. N. (2008). Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 742.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations. Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kagitcibasi, C. (1996). Family and human development across cultures: a view from the other side. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc..

Kagitcibasi, C., & Ataca, B. (2005). Value of children and family change: a three decade portrait from Turkey. Applied Psychology: International Review, 54, 317–337.

Kouros, C. D., & Garber, J. (2010). Dynamic associations between maternal depressive symptoms and adolescents’ depressive and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1069–1081.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., & Guttentag, C. (2008). A responsive parenting intervention: the optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1335–1353.

Lee, S. J., Altschul, I., & Gershoff, E. T. (2013). Does warmth moderate longitudinal associations between maternal spanking and child aggression in early childhood? Developmental Psychology, 49, 2017.

McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 577–605.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

OECD. (2010). Data by topic. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/social/soc/oecdfamilydatabase.htm.

Paterson, G., & Sanson, A. (1999). The association of behavioral adjustment to temperament, parenting and family characteristics among 5-year-old children. Social Development, 8, 293–309.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene: Castalia.

Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., & Hellinckx, W. (2006). A cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth curve analysis of normative CBCL aggressive and delinquent problem behavior: associations with harsh discipline and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 444–459.

Prior, M., Sanson, A., & ve Oberklaid, F. (1989). The Australian temperament project. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 537–556). Chichester: Wiley.

Reedtz, C., Bertelsen, B., Lurie, J. I. M., Handegård, B. H., Clifford, G., & Morch, W. T. (2008). Eyberg child behavior inventory (ECBI): Norwegian norms to identify conduct problems in children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49, 31–38.

Reef, J., Diamantopoulou, S., van Meurs, I., Verhulst, F., & van der Ende, J. (2010). Predicting adult emotional and behavioral problems from externalizing problem trajectories in a 24-year longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 577–585.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Baydar, N. (2004). Halting the development of conduct problems in head start children: the effects of parent training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 279–291.

Serbin, L. A., Kingdon, D., Ruttle, P. L., & Stack, D. M. (2015). The impact of children's internalizing and externalizing problems on parenting: Transactional processes and reciprocal change over time. Development and Psychopathology, 27(4 pt1), 969–986.

Sheehan, M. J., & Watson, M. W. (2008). Reciprocal influences between maternal discipline techniques and aggression in children and adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 245–255.

Shepard, S. A., & Dickstein, S. (2009). Preventive intervention for early childhood behavioral problems: an ecological perspective. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18, 687–706.

Smith, J. D., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., Winter, C. C., & Patterson, G. R. (2014). Coercive family process and early-onset conduct problems from age 2 to school entry. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 917–932.

Sunar, D., & Fisek, G. O. (2005). Contemporary Turkish families. In J. L. Roopnarine & U. P. Gielen (Eds.), Families in global perspective. Boston: Pearson Education Inc..

Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behaviour during childhood: what have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 129–141.

Verhoeven, M., Junger, M., van Aken, C., Deković, M., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2010). Parenting and children's externalizing behavior: Bidirectionality during toddlerhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 93–105.

Villodas, M. T., Bagner, D. M., & Thompson, R. (2015). A step beyond maternal depression and child behavior problems: the role of mother–child aggression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 16, 1–8.

Yağmurlu, B., & Sanson, A. (2009). The role of child temperament, parenting and culture in the development of prosocial behaviors. Australian Journal of Psychology, 61, 77–88.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Turkish Institute for Scientific and Technological Research (106 K347 and 109 K525) and received generous support from Koc University. Additional partial support for this study was received from Grand Challenges Canada (Grant 0072-03 to the Grantee, The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants of the study.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baydar, N., Akcinar, B. Reciprocal Relations between the Trajectories of Mothers’ Harsh Discipline, Responsiveness and Aggression in Early Childhood. J Abnorm Child Psychol 46, 83–97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0280-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0280-y