Abstract

This study traces the developmental course of irritability symptoms in oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) from ages 3–5 and examines the psychopathological outcomes of the different trajectories at age 6. Method. A sample of 622 3-year-old preschoolers (311 were boys), followed up until age 6, was assessed yearly with a semi-structured diagnostic interview with parents and at age 6 with questionnaires answered by parents, teachers and children. Results. Growth-Mixture-Modeling yielded five trajectories of irritability levels for the whole sample (high-persistent 3.5 %, decreasing 3.8 %, increasing 2.6 %, low-persistent 44.1 % and null 46.0 %). Among the children who presented with ODD during preschool age, three trajectories of irritability symptoms resulted (high-persistent 31.9 %, decreasing 34.9 % and increasing 33.2 %). Null, low-persistent and decreasing irritability courses in the sample as a whole gave very similar discriminative capacity for children’s psychopathological state at age 6, while the increasing and high-persistent categories involved poorer clinical outcomes than the null course. For ODD children, the high-persistent and increasing trajectories of irritability predicted disruptive behavior disorders, comorbidity, high level of functional impairment, internalizing and externalizing problems and low anger control at age 6. Conclusions. Irritability identifies a subset of ODD children at high risk of poorer longitudinal psychopathological and functional outcomes. It might be clinically relevant to identify this subset of ODD children with a high number of irritability symptoms throughout development with a view to preventing comorbid and future adverse longitudinal outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Irritability is defined as “an excessive reactivity to negative emotional stimuli that has an affective component (anger) and a behavioral component (aggression)” (Leibenluft and Stoddard 2013, p. 1473), and is characterized by easy annoyance, low frustration, touchiness, and anger/temper outbursts. Irritability is moderately stable from school age to adulthood and heritable (heritability between 0.25 and 0.45 in childhood and adolescence), and has been described as a personality trait (Kuny et al. 2013; Stringaris et al. 2012). Irritability is a common symptom in different disorders, such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder, and specifically it is a core component of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Anger, hostility and irritability are all negative emotions relevant to disruptive behavior disorders. Such negative emotionality is correlated with self-regulation problems, which in turn, associates with behavioral difficulties (DeLisi and Vaughn 2014). High negative emotionality has been proposed by temperament theorists as central in the etiology of antisocial behavior (DeLisi and Vaughn 2014).

ODD is among the most prevalent disorders from preschool age (Ezpeleta et al. 2014) to adulthood (Nock et al. 2007). ODD is accompanied by varied concurrent (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder –ADHD) and successive (conduct disorder, anxiety, depression) comorbidity (Maughan et al. 2004), and it is a strong predictor of depression in adulthood (Copeland et al. 2009). In an attempt to explain this consistent comorbidity pattern, the underlying structure of ODD symptoms has been studied, and several dimensions of ODD have been identified in child-to-adolescent samples: irritable (including loses temper, angry and touchy); headstrong (argues, defies, annoys, blames), and hurtful (spiteful-vindictive) (Rowe et al. 2010; Stringaris and Goodman 2009b). Both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, the dimensions show distinct psychopathological associations: the irritable dimension is associated with emotional disorders, headstrong with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and hurtful with conduct disorder (CD) and aggressive symptoms (Rowe et al. 2010; Stringaris and Goodman 2009a; Whelan et al. 2013). For preschoolers, these dimensions (Ezpeleta et al. 2012) as well as Burke’s model (Burke et al. 2010a, 2005) with negative affect (touchy, angry, spiteful), oppositional behavior (temper, argues, defies) and antagonistic behavior (annoys, blames) have been confirmed (Ezpeleta and Penelo 2015; Lavigne et al. 2014, 2015). Based on these results, it has been suggested that the association between ODD and depression or anxiety may be explained by the shared negative affectivity and the irritability component.

For the definition of ODD, the recent DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) classification separates the symptomatology following the above dimensions, but does not indicate any specifier for cases in which ODD presents with strong or persistent irritability. On the contrary, cases with marked, chronic irritability with severe recurrent temper outbursts are classified under disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) in the depressive section, a diagnosis that cannot be made together with ODD. Copeland et al. (2013) tested the proposed DSM-5 definition for DMDD in three samples from the general population aged 2 to 17 and reported prevalence between 0.8 (ages 9–17) and 3.3 % (ages 2–6) and a strong overlap with ODD. According to these authors, the high comorbidity with ODD and the common longitudinal association of both disorders with depressive disorders questions the classification of DMDD as a mood disorder, given that both have mixed emotional and behavioral symptoms. Recently, Dougherty et al. (2014) reported a prevalence of 8.2 % for DMDD in a sample of 6-year-old children and observed that the disorder was associated with depression and ODD. Therefore, further study is needed regarding how chronic irritability presents through development.

Few studies have focused on person-centered analyses, which enable us to find groups of children with similar responses in relation to irritability and to continue studying the outcomes for the different groups of children. Using Latent Class Analysis in a large sample of 7–12-year-old Dutch twins to define subsets of ODD based on the 6 symptoms of the ODD scale in the Conners Parent Rating Scale, four classes emerged: no symptoms, defiant, irritability and high symptoms (Kuny et al. 2013). Children in the irritability category (10 %) presented higher scores on anxious-depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and internalizing problems. Analogously, Althoff et al. (2014) found similar categories using the DSM-oriented oppositional defiant problems scale of the CBCL in large samples from the general population in the U.S. and the Netherlands. The irritability category encompassed 22 % of the sample; this class was concurrently associated with a lifetime diagnosis of anxiety disorders but not with a diagnosis of ODD, and predicted mood disorders 14 years later.

Few studies have centered on the outcomes of irritability specifically within children with ODD. One such study examined 7–12-year-old boys from a clinical sample that was over-representative of children with ADHD, ODD, and CD (Burke 2012). The information provided by parents on ODD symptoms from the DISC interview from year 1 gave three categories of children: oppositional behavior (47.5 %), irritability (36 %), and low symptoms (16.4 %). Children in the irritability category at year 1 showed more depressive and anxiety symptoms and higher neuroticism scores at follow-up at ages 17 and 18. In preschoolers from the general population, Lavigne et al. (2014) have reported that ODD irritable dimension scores at ages 4 and 5 predicted subsequent depression but not anxiety. At these ages, however, the associations or predictions from irritability were not specific, given that other dimensions (such us headstrong or antagonistic behavior) were also associated with internalizing disorders (Ezpeleta et al. 2012; Lavigne et al. 2014). Therefore, more information is needed about the outcomes and specificities of irritability at younger ages. Using a variable-oriented approach, Dougherty et al. (2013) examined a large sample of preschoolers from the general population to determine whether chronic irritability at age 3 was related to negative psychopathological outcomes at age 6. Irritability, as defined through six symptoms in a diagnostic interview (irritable mood, feelings of anger, displays anger and resentment, feelings of frustration, episodes of temper, and episodes of excessive temper), was associated concurrently and longitudinally with ODD, depressive disorders, and functional impairment, even when controlling for baseline symptomatology and excluding symptom overlap.

Previous studies, mostly based on variable-oriented analyses, indicate that irritability marks a specific risk for subsequent internalizing disorders and suggest several subtypes of ODD. Most of the person-centered studies have been carried out in samples of children aged 7 and older which do not represent the general population (twins, clinical patients, or only boys), and have studied categories of ODD such as irritability, cross-sectionally, but none has longitudinally studied the trajectories of irritability in preschoolers in the context of ODD. The current conception of ODD is that it is a mixed behavior and emotion disorder that starts early in life and remains stable. Preschool age is developmentally important in relation to both anger (a high frequency of irritability symptoms; Egger and Angold 2006) and emotion regulation, as most children are developing self-regulation skills during this period (Halligan et al. 2013). Therefore, it is imperative to know if irritability can identify subtypes of ODD at this early age. This information might be highly relevant for detection and might permit us to prevent subsequent internalizing psychopathology associated with ODD. Given this, we set three specific objectives in this study: 1) to trace the developmental trajectories of irritability symptoms as defined in DSM-IV ODD from ages 3 to 5 for a sample of preschool children representing the general population; 2) to trace the developmental trajectories of irritability symptoms among a subsample of children with ODD; and 3) to ascertain the outcomes of these trajectories at age 6. We expected to find several developmental trajectories of irritability both in the whole sample and among the children with ODD, with one trajectory being chronically irritable children (objectives 1 and 2). Among the children with ODD, we expected that the chronic trajectory would identify a subgroup of children with different outcomes in comparison to other irritability trajectories. With respect to the research carried out to date, we will add information regarding whether irritability specifies a distinct ODD group starting at preschool age using a person-centered longitudinal approach in a sample from the general population and with information from several reporters (parents, teachers, and the children themselves).

Method

Participants

The sample derives from a longitudinal study on psychopathological risk factors starting at age 3 described in Ezpeleta et al. (2014). The initial sample consisted of 2283 children randomly selected from early-childhood schools in Barcelona (Spain). A two-phase design was employed. In the first phase of sampling, 1341 families (58.7 %) agreed to participate (33.6 % high socioeconomic status, 43.1 % middle, and 23.3 % low; 50.9 % were boys). To ensure the participation of children with possible behavioral problems, the parent-rated SDQ (3–4 year-old version) conduct problems scale (Goodman 2001) plus four ODD DSM-IV-TR symptoms were used to screen. Two groups were potentially considered: screen-positive (all children with SDQ scores ≥ 4, percentile 90, or with a response option of two ("certainly true") in any of the 8 DSM-IV ODD symptoms), and screen-negative (a random group comprising 28 % of children who did not reach the positive threshold). The number of refusals in this phase was n = 135 (10.6 %), and these children did not differ in sex (χ 2 = 0.05, p = 0.815) or type of school (χ 2 = 0.04, p = 0.850) from those who did agree to participate. The only difference was in SES, with a higher participation ratio for high socioeconomic levels, 86.2 % vs. 73.6 %; χ 2 = 14.09, p = 0.007.

The final sample for the follow-up (second phase of sampling design) included 622 children first assessed at age 3. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 (and Table S1 online). The screen-positive group comprised 417 children (49.4 % boys) and the screen-negative group comprised 205 children (105, 51.2 %, boys). At age 4, 603 children remained in the follow-up (97.4 % of the initial screen positive group and 96.6 % of the screen negative; χ 2 = 0.28, p = 0.598) (303 boys), at age 5 there were 570 children (92.8 % pertaining to the initial screen positive and 91.3 % to the screen negative; χ 2 = 0.45, p = 0.502) (288 boys), and at age 6 there were 511 children (83.4 % for the initial screen positive group and 79.6 % of the screen negative; χ 2 = 1.36, p = 0.244) (256 boys). No differences in sex (χ 2 = 1.57; p = 0.21), SES (χ 2 = 8.63; p = 0.071) or type of school (χ 2 = 0.39; p = 0.53) were found on comparing completers and drop-outs.

Measures

The Diagnostic Interview of Children and Adolescents for Parents of Preschool Children (DICA-PPC; Ezpeleta et al. 2011) is a semi-structured interview for parents of children aged 3 to 7 that follows the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric 2000). The interview was used to identify ODD diagnoses and the ODD dimensions described by Stringaris and Goodman (2009b): irritability symptoms (loses temper, touchy-annoyed and angry-resentful), headstrong (argues, defies, annoys, blames), and hurtful (spiteful-vindictive). The symptom count from the irritability dimension of ODD was used to yield the trajectories. The diagnoses analyzed as outcomes at age 6 were disruptive behavior disorders (ADHD, ODD, and CD), depressive disorders (major and minor depression) and anxiety disorders (separation and generalized anxiety, specific and social phobia), in addition to the number of CD-aggressive symptoms (bullying, fighting, weapon use, cruelty to people, cruelty to animals, stealing with confrontation, and forced sex) and CD-non-aggressive symptoms (fire-raising, vandalism, breaking and entering, lying, and stealing without confrontation). Comorbidity was defined as the presence of more than one disorder among those analyzed in the study. Use of services was recorded after assessment of the symptoms of each disorder. DICA-PPC diagnoses have shown acceptable test-retest agreement, ranging from kappa 0.76 for disruptive behavior disorders to 0.64 for anxiety disorders (Ezpeleta et al. 2011). Interviews were carried out by psychologists with master’s degrees and psychology students supervised by two Ph.D. clinical child psychologists.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/6-18; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) measures a child’s behavioral and emotional problems according to the parents’ perception. Cronbach’s alpha of the scales in the sample ranged from 0.46 for somatic complaints to 0.92 for total scale.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 2001) assesses children’s mental health with 25 items on five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior. The items on the first four scales provide a total difficulties score. Two broader internalizing (emotional and peers) and externalizing (conduct and hyperactivity) scales (Goodman et al. 2010) were also analyzed. The questionnaire also has an impact supplement, which is useful for considering possible service use, and in which the informant judges whether the child has a problem and the degree of distress, social impairment, and burden it causes to others. This questionnaire was completed by teachers. Cronbach’s alpha in the sample ranged from 0.60 for emotional symptoms to 0.82 for total scale.

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al. 1983) is a global measure of functional impairment rated by the interviewer based on information from the diagnostic interview. Scores above 70 indicate normal adaptation.

The Anger Questionnaire was created for this research project. It contains 40 items using a 3-point Likert-type scale (0: not at all; 1: a little; 2: a lot) related to the tendency to experience anger (Anger trait scale), to inadequately express anger (External expression scale), or to control anger appropriately (Control scale). The items included in each dimension were constructed by a committee of experts in developmental psychopathology based on a theoretical-clinical framework regarding anger at early ages. Children answered the questionnaire, which was read out by the researchers, at age 6. For the Anger trait scale, they were asked to indicate how often the situations happen to them (e.g., getting angry when asked to go to sleep, when another child takes his/her toys, or when it is difficult to do something, being in a bad mood when adults do not allow them to do something, getting angry easily, etc.). For the External expression and Control scales, the child was asked to say what s/he does when s/he gets angry (arguing, hitting, insulting, telling somebody off, trying to calm down, breathing deeply, etc.). Psychometric evidence of the reliability of the Anger-Questionnaire was obtained. A confirmatory factor analyses testing the internal structure of the questionnaire showed adequate fit for the 3-factor model, with low root mean square error of approximation index (RMSEA = 0.064, 95 % CI: 0.061 to 0.068), low standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR = 0.069) and significant (p < 0.001) and high standardized factor loadings (above 0.30) for all the items on their correspondent dimension (with the exception of three items with factor-scores between 0.19 and 0.22). Cronbach’s alphas were adequate and equal to 0.79 for the Trait scale, 0.82 for the External expression scale, and 0.72 for the Control scale.

Procedure

The project was approved by the ethics review committee of the authors’ institution. Families were recruited at the schools and gave their written consent. All families of children in grade P3 (3-year-olds) in the participating schools were invited to answer the screening questionnaire. Families who agreed were interviewed at the school for each assessment. The interview team was specifically trained, and all interviewers were blind to the screening group (see Ezpeleta et al. 2011). All interviews were audio-recorded and supervised. After the interview, the interviewer completed the CGAS, the teachers were given the SDQ for completion before the end of the academic year, and parents and children answered the questionnaires (at age 6). The data were collected once a year between November 2009 and July 2013, with an average interval of 11.01 months between the first and second assessments (SD = 1.15), 12.45 months (SD = 1.19) between the second and third assessments, and 10.81 months (SD = 1.55) between the third and fourth assessments. The average interval between the parent-family assessment and teacher’s report in the follow-ups ranged from1.42 months (SD = 1.80) for the first assessment to 2.84 months (SD = 1.89) for the fourth assessment.

Statistical Analysis

The trajectories were obtained in MPlus7 using the sampling weight procedure to account for the multi-sampling design (each child was weighted by the inverse proportion to the probability of selection in the second phase of the sampling), through Growth-Mixture-Modeling (GMM) and Robust-Maximum-Likelihood (MLR) (Enders and Bandalos 2001; Muthén and Muthén 2012). The MLR constitutes a full-information method used for non-ignorable missing data modeling where categorical outcomes are indicators of missingness and where missingness can be predicted by continuous and categorical latent variables, and it gives robust standard errors and the T2* chi-square statistic test of Yuan and Bentler (2000) for all the parameters. Two GMMs were obtained for the developmental course of the irritability symptoms during the preschool period (3 to 5 years old): a) among the whole sample of n = 622 children (this model was adjusted for the presence of ODD during the follow-up) and b) among the subsample of n = 103 children who presented a diagnosis of ODD in the DICA-PPC at any of the three assessments of the preschool period -ages 3/4/5 years-old- (this model was adjusted for the number of headstrong symptoms). The selection of the number of trajectories for each model was based on: a) the lowest Bayesian information criterion (BIC); b) entropy > 0.80; c) high on-diagonal average values (around 0.80) in the matrix containing the probabilities of membership; d) the best clinical interpretability; and e) trajectory classes with enough sample sizes to allow statistical comparison (at least 5 % of participants).

The other analyses were carried out with Complex Samples (due to the multi-stage sampling) in SPSS20, weighting each subject by the inverse proportion to the probability of selection in the second phase of the sampling. The capacity of trajectories to discriminate psychopathology and functioning at age 6 was measured with logistic regression (binary outcomes) and General Linear Models (GLM, quantitative criteria), adjusted for the presence of comorbidities different from those included in the models and the number of ODD-headstrong symptoms at baseline (age 3). Pairwise comparisons (odds ratio -OR- in logistics and mean differences -MD- in GLM) estimated differences between trajectories. Longitudinal discriminative models were obtained for the n = 511 children who remained in the follow-up at age 6 years-old. Due to the low sample size for some trajectories (with the consequent low statistical power), and since it is more relevant to measure and interpret the effect sizes than to make conclusions based on statistical significance tests, Cohen’s-d coefficients measured the effect size for each pairwise comparison (results did not include Bonferroni’s corrections), considering moderate effect size as |d| > 0.5 and a large effect size as |d| > 0.8.

Results

Irritability Trajectories in the Whole Sample

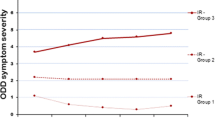

GMM (adjusted for the presence of ODD during the follow-up) yielded five trajectories for the number of irritability symptoms in the whole sample (Fig. 1, left). Adequate fit was achieved (Table S2 online shows goodness-of-fit indexes, estimated/observed means, intercepts and slopes). Trajectories 1 (N1 = 237, 46.0 %) and 2 (N2 = 301, 44.1 %) represented those children with no symptoms from ages 3 to 5 or with low persistent irritability symptoms. Trajectory 3 (N3 = 35, 3.8 %) represented high-decreasing irritability symptoms. Trajectory 4 (N4 = 17, 2.61 %) represented increasers, children who started with low mean symptoms at age 3 and showed an increase at age 5. And Trajectory 5 (N5 = 32, 3.51 %) represented those children with high-persistent symptoms. No statistical differences for trajectories emerged for children’s sex (χ 2 = 3.01; p = 0.56), socioeconomic status (χ 2 = 11.1; p = 0.20) or ethnic group (χ 2 = 6.16; p = 0.19).

The first rows of Table S3 online contain means for the number of ODD irritability, headstrong, and total symptoms for each trajectory, as well as the percentage of subjects who presented the hurtful symptom.

The first columns of Table 2 contains the distribution of the outcomes at age 6 (prevalences for binary responses and means for quantitative) for the five irritability trajectories obtained in the whole sample (N = 511 children who remained in the follow-up at age 6). The next columns contain the global predictive capacity of the trajectories (R2 coefficient) and the pair-wise comparisons selecting as the reference group the Trajectory 1 null irritability trajectory (that is, each trajectory was individually compared to the Trajectory 1 class). Low-persistent irritability course during preschool age (Trajectory 2) was very similar in its discriminative capacity for the outcomes at age 6 to that of null irritability course (Trajectory 1), and the only mean differences with moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s-d around 0.50) were for the number of ODD symptoms (irritability and total) and the level of functional impairment (poorer results for low-persistent children compared to null irritability children). The decreasing irritability course (Trajectory 3) also yielded similar outcomes at age 6 to those for null course (Trajectory 1), and relevant differences (|d| > _0.50) were only for the number of ODD-irritability-symptoms, functional impairment level, SDQ-internalizing scores and anger externalization and control levels (clinically poorer outcomes for children with the decreasing trajectory). Increasing and high-persistent irritability trajectories (Trajectories 4 and 5) achieved clearly the poorest outcomes at age 6, with moderate to high effect sizes for many differences compared to the null course trajectory (Trajectory 1). Specifically, increasing irritability course (Trajectory 4) was clinically worse than children in the null course for the presence of disruptive disorders (ODD), depression, comorbidity and use of services, as well as for the number of ODD-symptoms, functional impairment level, anxiety, aggressive behaviors, externalizing and total problems on the CBCL, and teachers’ perceived higher levels of problems for relations with peers and for internalizing problems. Similarly, the high-persistent irritability course (Trajectory 5) also yielded a poorer psychopathological outcome than the null course in disruptive disorders (ODD), presence of comorbid disorders, impairment, number of ODD symptoms, the CBCL scales (except for somatic complaints and thought problems), anger externalization and control scores, and teachers’ perceived higher levels of problems with peers, internalizing, global difficulties and interference with peers and at school.

Irritability Trajectories Among Children with ODD

The GMM (adjusted for the number of headstrong symptoms during the follow-up) among the children with ODD at any time between ages 3 and 5 (N = 103) identified three irritability trajectories (Fig. 1, right) with adequate fit (see goodness-of-fit in Table S2 online). Trajectory 1 (N1 = 29, 34.9 %) represented decreasing irritability symptomatology from ages 3 to 5 (children started with a moderate-high mean number of symptoms at age 3 and achieved considerably lower means at ages 4–5). Trajectory 2 (N2 = 23, 33.2 %) represented increasing irritability symptoms (children who started with a low mean number of symptoms at age 3 and had higher means at ages 4–5). Trajectory 3 (N3 = 31, 31.9 %) represented high-persistent (high mean number of symptoms at ages 3 to 5). The decline in the mean irritability scores between ages 3–5 for the high-persistent trajectory (means decreased from 1.85 to 1.70 and 1.54) was weak: the slope for this developmental course was not statistically significant (b = −0.16, t = −1.28, p = 0.20). No statistical differences for trajectories emerged for children’s sex (χ 2 = 4.30; p = 0.12), socioeconomic status (χ 2 = 8.41; p = 0.078), or ethnic group (χ 2 = 0.38; p = 0.83).

The last rows of Table S3 online contain means for the number of ODD irritability, headstrong, and total symptoms for each trajectory. The means for the headstrong dimension and the ODD-total symptoms showed similar evolution to the ODD-irritability used to define the empirical trajectories, as well as the percentage of participants who presented the hurtful symptom.

Outcomes of the Irritability Trajectories in Children with ODD at Age 6

Table 3 summarizes outcomes at age 6 for the three irritability trajectories obtained for children with ODD during the preschool period (N = 103) and the comparisons carried out with the N = 83 children remaining at age 6. The first column on the left side shows the distribution of the outcomes (proportions or means), and the other columns contain the pairwise comparison for trajectories (OR in logistics and MD in GLM).

Considering significant differences and moderate-to-good effect sizes for pairwise comparisons, in comparison to both the increasing and high-persistent trajectories (2 and 3), Trajectory 1 (decreasing) showed lower prevalence for disruptive behavior disorders, ADHD (this comparison was relevant only for Trajectory 2 = increasing vs Trajectory 1 = decreasing), ODD, number of irritability symptoms, headstrong symptoms (relevant comparison for Trajectory 3 = high-persistent vs Trajectory 1 = decreasing), total ODD symptoms, comorbidity, use of services (relevant comparison for Trajectory 2 = increasing vs Trajectory 1 = decreasing) and functional impairment levels. Considering the CBCL mean scores, Trajectory 3 (high-persistent) yielded higher mean psychopathology levels than Trajectory 1 (increasing) on withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior, internalizing, externalizing and total scales. Trajectory 3 (high-persistent) also yielded lower self-reported control of anger than children in the decreasing trajectory (Trajectory 1). Teachers reported higher mean scores on the SDQ-conduct problems scale for children in the increasing (Trajectory 2) versus decreasing (Trajectory 1) groups.

High-persistent and increasing irritability trajectories only differed in the prevalence of depression and comorbidity (higher percentages for the increasing irritability class), and the mean scores in the CBCL withdrawn/depressed and rule-breaking scales (higher means for high-persistent irritability).

The last two columns of Table 3 show the comparison of Trajectories 2 and 3 clustered into the same group (increasing plus high-persistent irritability) with Trajectory 1 (decreasing irritability). Clustered Trajectories 2 + 3 showed the scores or proportions in the more dysfunctional direction for many outcomes: higher prevalences of DSM-IV disruptive behavior disorders, ODD and comorbidity, and higher mean scores for number of irritability and ODD-total symptoms, higher impairment and higher mean scores on the CBCL withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior, internalizing, externalizing and total scales.

Discussion

This study identified several developmental trajectories of irritability symptoms included in DSM-IV ODD definition at preschool ages. A majority of the children in the sample representing the general population did not present irritability, or they presented it at very low levels, but 3.5 % presented sustained irritability throughout this early developmental period. On the contrary, only a minority of preschoolers with ODD between ages 3 to 5 showed a decrease in their level of irritability (34.9 %). Approximately 33 % of children with ADHD showed increases in irritability with age, and about 32 % of children with ODD showed persistent irritability. The persistence or increasing of irritability throughout the period studied was associated with poorer outcomes in both the general population sample and among the children with ODD. We did not find sex differences in irritability.

In the whole sample representing the general population, irritability was not a marked characteristic of most children (90 %) from ages 3 to 5. However, 3.5 % of the preschoolers from the general population did show persistent irritability. This value indicates sustained irritability problems for a significant proportion of preschoolers. Children in the high-persistent trajectory experience chronic states of arousal (lose temper, touchy-annoyed, angry-resentful) when most of their peers do not. Therefore, children in the early persisten and increasing trajectories of irritability show early difficulties in managing irritability, which put them at risk for later socioemotional development problems (Razza et al. 2012). In our sample, as reported by different informants in different contexts, these children continued to present with ODD, and had more comorbidity (internalizing and externalizing), poorer functioning, and more difficulties with peers. Developmentally, ODD is a risk factor for conduct disorder and other internalizing and externalizing comorbidity, and conduct disorder is followed in a portion of cases by antisocial personality disorder (Burke et al. 2010b; Maughan et al. 2004; Rowe et al. 2002). In this line, there is a body of literature that has reported consistently that about 5 % of the population from childhood to adulthood are involved in serious antisocial behavior and show an elevated prevalence of violence, delinquency and substance use (Vaughn et al. 2011, 2014). The high persistent trajectory in this study might be identifying children with these developmental risks, which highlights the need for indicated prevention. Future research should test the differential efficacy of preventive programs across the different developmental trajectories in order to improve their efficacy.

Considering children with ODD, two groups were characterized by high irritability in their development: the high-persistent and the increasing trajectory groups. Among the children with ODD, approximately 32 % presented with a high level of lasting irritability symptoms, while in 33 % the levels of irritability were increasing during the course of development. Children in the high-persistent trajectory had high severity of ODD symptoms (rule-breaking) and withdrawn/depressed behavior at age 6. For the children in these two trajectories emotional dysregulation worsened or stayed at a dysfunctional level as they aged. Their increased difficulties in controlling irritability are associated with highly negative outcomes, and they present the poorest outcomes in terms of continuity and severity of ODD, internalizing and externalizing comorbidity, functional impairment, and self-assessment of difficulties in anger control. The importance of the outcomes with which these trajectories are associated, the effect sizes of the associations, and the cross-informant agreement on identifying the difficulties all support the empirically validity of these trajectories. High irritability (persistent or increasing) distinguishes a subtype of ODD children with marked difficulties in emotion regulation and poorer prognosis. Therefore, early identification of this subtype and early intervention must be a priority when an ODD diagnosis is given. Children in this subtype might benefit from a strengthening of the emotional components of existing intervention programs, such as emotional literacy, anger management, empathy or perspective-taking, social and communication skills, and interpersonal problem-solving (Webster-Stratton and Reid 2004).

Previous studies have used variable-centered analyses to validate the structure of ODD symptoms (Burke et al. 2010a; Ezpeleta et al. 2012; Krieger et al. 2013; Rowe et al. 2010; Stringaris and Goodman 2009b). Our contribution to previous studies is the validation of the ODD irritability subtype using a person-centered analysis. These results are in line with the ICD-11 (WHO, 2014) proposal to include a specifier to indicate whether the presentation of ODD includes chronic irritability and anger or not (Lochman et al. in press). Other studies have proposed another subtyping of ODD. In preschoolers, Willoughby et al. (2011) reported that Callous-Unemotional traits distinguished a group of children with ODD who were less fearful, recovered more easily after an upset, and showed less negative reactivity, lower heart period reactivity, and higher levels of general arousal than those with ODD only. The different ODD subgroups identified in the literature indicate that ODD is a heterogeneous disorder and the distinct subgroups may require different treatment components.

Some limitations should be taken into account in interpreting the results of this study. Since we studied a very young sample of the general population, and psychopathology is not very frequent in such community samples, we found few cases of most disorders, particularly major depression and conduct disorders. Therefore, some associations could be affected by the low prevalence. As expected, few children from the general population presented ODD and, therefore, among the children with ODD, the distribution of the differently affected children into three different trajectories might have reduced the statistical power of the analyses, and therefore effect size measures were estimated and interpreted in this study. Related to sample sizes, it is usually considered that statistical procedures underlying structural equation modeling and GMM require large samples. However, it must be noted that there is not a general rule regarding how large a sample is necessary for GMM and many recent publications state that identification of unobserved groups with these procedures depends on many factors (Ram and Grimm 2009) (extent of between-group differences, homogeneity of the change process, group sizes or reliability of measurement), and that small samples are sufficient under certain circumstances (Berlin et al. 2014). The theoretical framework of the present study, the goodness-of-fit of the trajectories and the proven longitudinal discriminative capacity of the emerged latent-classes provide empirical validity to the use of GMM in this data.

On the other hand, the strengths of the study are the use of a person-centered approach, the inclusion of preschool children, and the use of information from several reporters (parent, teacher, children) using several techniques (diagnostic interviews and questionnaires).

The identification of several irritability trajectories has important implications for early diagnosis, treatment, and recommended preventive interventions. In the general population, by age 5 it is normative for children to present few symptoms of irritability, but we found that about 6 % of the children (persistent plus increasing) continued to show difficulties in emotional regulation of irritability. These children had dysfunctional outcomes at age 6. These results highlight the importance of observing and detecting levels of irritability early in development, as this is a risk factor for psychopathological outcomes in children from the general population. Among the children with ODD, high irritability (persistent and increasing) identifies a subtype of ODD with the most severe outcomes, and these children should be identified and treated. Longitudinal studies with longer follow-ups throughout childhood and adolescence are needed to further test the predictive validity of this subtype.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families.

Althoff, R. R., Kuny-Slock, A. V., Verhulst, F. C., Hudziak, J. J., & van der Ende, J. (2014). Classes of oppositional-defiant behavior: concurrent and predictive validity. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 55, 1162–1171. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12233.

American Psychiatric Association (2000). DSM-IV Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Text Revised ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Berlin, K. S., Parra, G. R., & Williams, N. A. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 188–203. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jst085.

Burke, J. D. (2012). An affective dimension within oppositional defiant disorder symptoms among boys: personality and psychopathology outcomes into early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1176–1183. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02598.x.

Burke, J. D., Loeber, R., Lahey, B. B., & Rathouz, P. J. (2005). Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1200–1210.

Burke, J. D., Hipwell, A. E., & Loeber, R. (2010a). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 484–492. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.016.

Burke, J. D., Waldman, I., & Lahey, B. B. (2010b). Predictive validity of childhood oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: implications for the DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 739–751. doi:10.1037/a0019708.

Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772.

Copeland, W. E., Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Egger, H. (2013). Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 173–179. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132.

DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2014). Foundation for a temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior and criminal justice system involvement. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 10–25. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.11.0.

Dougherty, L. R., Smith, V. C., Bufferd, S. J., Stringaris, A., Leibenluft, E., Carlson, G. A., & Klein, D. N. (2013). Preschool irritability: longitudinal associations with psychiatric disorders at age 6 and parental psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 1304–1313. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.007.

Dougherty, L. R., Smith, V. C., Bufferd, S. J., Carlson, G. A., Stringaris, A., Leibenluft, E., & Klein, D. N. (2014). DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: correlates and predictors in young children. Psychological Medicine, 44, 2339–2350. doi:10.1017/s0033291713003115.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337.

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5.

Ezpeleta, L., & Penelo, E. (2015). Measurement invariance of oppositional defiant disorder dimensions in 3-year-old preschoolers. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000205.

Ezpeleta, L., Osa, N. l., Granero, R., Doménech, J. M., & Reich, W. (2011). The diagnostic interview for children and adolescents for parents of preschool children. Psychiatry Research, 190, 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.034.

Ezpeleta, L., Granero, R., Osa, N. l., Penelo, E., & Doménech, J. M. (2012). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1128–1138. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02545.x.

Ezpeleta, L., Osa, N. l., & Doménech, J. M. (2014). Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders, comorbidity and impairment in 3-year-old Spanish preschoolers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 145–155. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0683-1.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337–1345. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015.

Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1179–1191. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x.

Halligan, S. L., Cooper, P. J., Fearon, P., Wheeler, S. L., Crosby, M., & Murray, L. (2013). The longitudinal development of emotion regulation capacities in children at risk for externalizing disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 391–406. doi:10.1017/s0954579412001137.

Krieger, F. V., Polanczyk, V. G., Robert, G., Rohde, L. A., Graeff-Martins, A. S., Salum, G., …, & Stringaris, A. (2013). Dimensions of oppositionality in a Brazilian community sample: testing the DSM-5 proposal and etiological links. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 389–400.e381.

Kuny, A. V., Althoff, R. R., Copeland, W., Bartels, M., Van Beijsterveldt, C. E. M., Baer, J. C., & Hudziak, J. J. (2013). Separating the domains of oppositional behavior: comparing latent models of the Conners’ Oppositional Subscale. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 172–183. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.005.

Lavigne, J. V., Gouze, K. R., Bryant, F. B., & Hopkins, J. (2014). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in young children: heterotypic continuity with anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 937–951. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9853-1.

Lavigne, J. V., Bryant, F. B., Hopkins, J., & Gouze, K. R. (2015). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in young children: model comparisons, gender and longitudinal invariance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9919-0.

Leibenluft, E., & Stoddard, J. (2013). The developmental psychopathology of irritability. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1473–1487. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000722.

Lochman, J. E., Evans, S. C., Burke, J. D., Roberts, M. C., Fite, P. J., Reed, G. M., …, & Garralda, E. (in press). An empirically based alternative to DSM-5’s disruptive mood dysregulation disorder for ICD-11. World Psychiatry.

Maughan, B., Rowe, R., Messer, J., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2004). Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 609–621. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nock, M. K., Kazdin, A. E., Hiripi, E., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 48, 703713. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x.

Ram, N., & Grimm, K. J. (2009). Growth mixture modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 565–576.

Razza, R. A., Martin, A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). Anger and children’s socioemotional development: can parenting elicit a positive side to a negative emotion? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 845–856. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9545-1.

Rowe, R., Maughan, B., Pickles, A., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2002). The relationship between DSM-IV oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: findings from the Great Smoky Mountain Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 365–373. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00027.

Rowe, R., Costello, E. J., Angold, A., Copeland, W. E., & Maughan, B. (2010). Developmental pathways in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 726–738. doi:10.1037/a0020798.

Shaffer, D., Gould, M. S., Brasic, J., Ambrosini, P., Fisher, P., Bird, H., & Aluwahlia, S. (1983). A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 1228–1231. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010.

Stringaris, A., & Goodman, R. (2009a). Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 404–412. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30.

Stringaris, A., & Goodman, R. (2009b). Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 216–223. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01989.x.

Stringaris, A., Zavos, H., Leibenluft, E., Maughan, B., & Eley, T. C. (2012). Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 47–54. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549.

Vaughn, M. G., DeLisi, M., Gunter, T., Fu, Q., Beaver, K. M., Perron, B. E., & Howard, M. O. (2011). The severe 5 %: a latent class analysis of the externalizing behavior spectrum in the United States. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39, 75–80. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.12.001.

Vaughn, M. G., Salas-Wright, C. P., DeLisi, M., & Maynard, B. R. (2014). Violence and externalizing behavior among youth in the United States: is there a severe 5 %? Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 12, 3--21. doi:10.1177/1541204013478973.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2004). Strengthening social and emotional competence in young children. The foundation for early school readiness and success - incredible years classroom social skills and problem-solving curriculum. Infants and Young Children, 17, 96–113.

Whelan, Y. M., Stringaris, A., Maughan, B., & Barker, E. D. (2013). Developmental continuity of oppositional defiant disorder subdimensions at ages 8, 10, and 13 years and their distinct psychiatric outcomes at age 16 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 961–969. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.06.013.

Willoughby, M. T., Waschbusch, D. A., Moore, G. A., & Propper, C. B. (2011). Using the ASEBA to screen for callous unemotional traits in early childhood: factor structure, temporal stability, and utility. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 19–30. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9195-4.

World Health Organization (2014). The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision is due by 2017. Retrieved December 28th, 2014, from http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/en/

Yuan, K. H., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. In M. E. Sobel & M. P. Becker (Eds.), Sociological methodology (pp. 165–200). Washington, D.C.: ASA.

Acknowledgments

Funding was from Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness grant PSI2012-32695. We would like to thank the participating schools and families. Thanks to the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca, Departament d’Economia I Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2014 SGR 312).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ezpeleta, L., Granero, R., de la Osa, N. et al. Trajectories of Oppositional Defiant Disorder Irritability Symptoms in Preschool Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44, 115–128 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9972-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9972-3