Abstract

Despite researchers having averred that big data analytics (BDA) transforms firms' ways of doing business, knowledge about operationalizing these technologies in organizations to achieve strategic objectives is lacking. Moreover, organizations' great appetite for big data and limited empirical proof of whether BDA impacts organizations' transformational capacity poses a need for further empirical investigation. Therefore, this study explores the association between big data analytics management capabilities (BDAMC) and innovation performance via dynamic capabilities (DC), by applying the PLS-SEM technique to analyzing the feedback of 149 firms. Consequently, we ground our arguments on dynamic capability and social capital theory rather than a resource-based view that does not provide suitable explanations for the deployment of resources to adapt to change. Accordingly, we advance this research stream by finding that BDAMC significantly enhances innovation performance through DC. We also extend the literature by disclosing how BDAMC strengthens DC via strategic alignment and social capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The emergence of big data technologies transforms traditional business processes and fosters organizational capabilities. These technologies enable organizations to collect, store, analyze, and visualize data on an unprecedented scale. Big data analytics (BDA) help organizations convert huge amounts of raw data into information in no time, enhancing firms’ decision-making capacity and quality [1, 2]. Data-driven quick decision-making is crucial to achieving desired objectives. For instance, in the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and, particularly, in a “race against time” situation, China managed to contain the virus due to quick data-driven decision-making, while some countries have suffered because they were slow in their approaches [3]. A comprehensive approach to processing, analyzing, and managing the “5Vs” (volume, variety, velocity, veracity, and value) enhances performance, productivity, competitiveness, and innovativeness [4,5,6], and revolutionizes living, thinking, and working styles [7]. A significant number of firms believe that big data possesses the potential to revolutionize the competitive landscape and serves as a critical resource for fostering business value [8]. Moreover, BDA enables firms to generate unique information from raw data, revamp their production processes, and enhance revenue levels [9, 10]. For instance, “Nedbank” of South Africa uses BDA to provide customers with value-added services by developing new insights into their credit- and debit-card information, along with their demographic data. This enables the bank to pull the market edge for itself and its customers (i.e., McDonald's and Burger King). This novel insight significantly enhances the bank's profitability in the debit- and credit-card line, along with the retail banking business [11]. Despite their obvious significance, research claims that seventy-five percent of firms failed to achieve the intended organizational outcomes of implementing BDA tools [12]. The primary reason for failure was firms’ limited understanding of BDA in the organizational context [13, 14]. Likewise, Wamba et al. [15] report that the limited understanding and lack of essential conditions and capabilities to generate value from BDA are the main reasons for such failures. In this regard, the current study argues that fortifying big data analytics management capabilities (BDAMC) elevates organizations’ abilities to transform existing processes and generate business value (innovation performance). Thus, exploring whether and how BDAMC influences innovation performance can expand the current understanding of how BDA generates value.

Recently, organizations have increasingly invested in big data technologies to improve decision-making quality [16], which ultimately hoists firms’ competitive edge and outcomes [17]. Investments in the latest information technology and diversification are crucial to generating business value [18]. Yet, the literature reports mixed results regarding the association between these investments and firm outcomes. Some scholars report a positive association between them [19,20,21]; at the same time, others report no association [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Ghasemaghaei and Calic [12] also claim that these investments do not necessarily lead to intended outcomes, as only 25 percent of firms report significant improvement in outcomes from these investments [31]. Despite big data bringing unprecedented opportunities to the table, it also brings complexities and challenges for management [2]. Big data is a set of data characterized by the “3Vs” (volume, variety, and velocity) that enable firms to generate business value [32]. But to harness the value and exploit big data to its full potential, firms must establish relevant management capabilities [33, 34]. Similarly, McAfee et al. [35] also highlight the requisite management and leadership skills to avail the firm of opportunities that big data affords. A recent study reported that lack of management capability is one of the main barriers to operationalizing BDA [36]. Thus, we argue that firms must establish BDAMC to potentially influence their dynamic capabilities (DC), which subsequently may yield outcomes in terms of innovation performance. To date, this proposed indirect relationship of BDAMC and innovation performance via DC is under-researched. The empirical investigation of this association expands the research stream [33, 37] that reports the indirect association between BDA capabilities and outcomes. Ravichandran [38] and Yunis et al. [39] also support this stream and argue that information and communication technology-based capabilities yield outcomes through other capabilities. Thus, the current study expands the literature by exploring whether DC indirectly influences the association between BDAMC and innovation performance.

DC is firms’ ability to create, renew, and transform their organizational capabilities to remain competitive in the rapidly changing business environment [40, 41]. In the modern super-competitive business world, organizations must proactively alter their business strategies and actions to cope with that environment [42]. In this regard, protecting the firm’s DC is essential to fostering competitiveness and performance [43, 44], the firm’s primary objective. Rapid changes in market demand, shorter product life cycles, complex product and service development processes, and a continuously changing business environment make DC a prominent research field in strategic-management research. Thus, it has evolved into one of the main streams of current strategy research. This encourages recent research (e.g., [45,46,47,48]) to explore DC from different perspectives and calls for future research to describe the pathways and mechanics through which organizations establish DC. In this regard, we argue that social capital has great potential to facilitate DC because it enables organizations’ access to valuable information and resources [49, 50]. It encompasses management connections with managers of other organizations, political leaders, institutions, and customers [51]. Forming social capital enhances firms' capacity to innovate [52]. Further, it supports organizations' efforts to identify potential opportunities, threats, and market needs [53], which may enhance their DC. Thus, organizations that establish extensive social capital by leveraging BDAMC should be able to build DC. The current study extends the literature by investigating the mediating role of social capital on BDAMC and DC as the mediating role of BDA in outcomes is confined. Accordingly, another crucial prospect with the potential to leverage BDAMC and yield DC is strategic alignment, finding the best fit between the organization's information systems and its business strategies [54]. This strategic fit is essential to leveraging information-system investments and fostering firm performance [55]. Recent research highlights this as top management’s primary concern [55, 56] because the operationalization and productive use of information systems heavily depend on their strategic alignment. Building strategic alignment is a continuous process of aligning a business’s vision, mission, goals, and objectives with its information-system strategies [57], which may influence the association between BDAMC and DC. Hence, our study also extends the limited understanding of strategic alignment by assessing its mediating role between BDAMC and DC, which needs further exploration.

To achieve the core objectives and fill the gaps in the literature we describe above, the study illuminates the association between BDAMC and innovation performance. It takes inspiration from recent research that argues organizations’ need for management skills and capabilities, to orchestrate value from big data [2, 33, 35]. Grounding its assumptions on dynamic capability and social capital theory, the study aims to achieve its research objectives by answering questions relating to whether and how BDAMC is associated with innovation performance. Does BDAMC influence the organization’s DC? Do social capital and strategic alignment mediate such an association between BDAMC and DC? Thus, we collected data from 149 manufacturing and logistics firms and employed the PLS-SEM approach to test our hypotheses. Results unveil BDAMC’s significant influence on DC, which consequently fosters innovation performance. Moreover, results show that social capital and strategic alignment substantially influence the association between BDAMC and DC.

The outcomes of the study substantially extend the current understanding of BDA [15, 58,59,60] and DC [41, 44, 61, 62], by exploring how BDAMC fosters firms’ innovation performance through DC. This study is among the preliminary ones that conceptualize a relationship between BDAMC, social capital, strategic alignment, DC, and innovation performance. The study adopts an integrative approach to dynamic capability, and social capital theory is its primary contribution, as many studies limit themselves to a single perspective—namely, a resource-based view—to discuss BDA. Furthermore, BDA facilitates data acquisition from heterogeneous resources and enables management to look into the huge amount of data from unique perspectives. This significantly enhances the organization’s abilities to sense and seize external market opportunities, stick to best practices (learning), and transform the existing processes (DC), consequently elevating its innovation performance. (Establishing and exploring this association is also a novel contribution by this study.) Moreover, BDAMC identifies the need to develop social capital and enable management’s access to valuable information and resources, subsequently enhancing DC. Accordingly, BDAMC also improves DC, by providing information that facilitates management’s devising strategies that strengthen its strategic alignment. We inferred this from the outcomes that show social capital and strategic alignment partially mediating the association between BDAMC and DC. Investigating these associations reinforces the significant contributions of this study.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1 Theoretical development

In a modern, complex, and hypercompetitive market environment, organizations must be dynamic with their resources and capabilities to explore and exploit the opportunities [63]. In the process, the DC view is crucial, stressing the organization’s ability to integrate, build, and transform organizational capabilities to adopt a rapidly changing business environment, ultimately yielding a competitive edge [41]. This extended form of the resource-based view argues that along with the acquisition of resources to achieve competitiveness, organizations should build capacities to create and transform their competencies, so these resources yield value [64]. Shamim et al. [63] report that DC depends on a firm’s ability to collect, produce, and combine knowledge resources. One effective way to acquire knowledge resources from various sources is through the social capital view [65], which values social interaction and makes individuals valuable in the organization [66]. As the organization’s capability and networking resource, social capital fosters its innovation capability [52]. Recent literature prominently discusses its role in creating value from big data [67] and facilitating decision-making quality in that context. Social capital enables firms’ access to big data and supports personnel in minimizing the hurdles associated with big data [68]. Keeping in mind the criticality of the DC and social capital view in fortifying organizational capabilities and knowledge resources essential to fostering innovation performance [69], we synergize them to provide a suitable theoretical foundation for the study. Prior research [33, 70] also uses the integrated approach, to study BDA from different perspectives. BDA is an emerging research area attracting researchers’ and practitioners’ attention, as a crucial prospect that fosters performance [37, 71, 72], decision-making quality [33], service innovation [70], and ambidexterity [63]. However, it is still unclear whether and how BDAMC influences firm innovation performance. Moreover, whether BDAMC enables firms to yield value (DC) by forming a strategic fit between information systems and business strategies is an under-researched question. Drawing on DC and the social capital perspective, we fill the gap in the literature by exploring the association of BDAMC with innovation performance through DC. The study also extends current understandings by examining the mediating role of strategic alignment and social capital between BDAMC and DC.

2.2 Big data analytics management capabilities (BDAMC)

Recently, research has paid great attention to big data management to address its management-related challenges and ecological problems [73, 74]. Big data is a considerable amount of data available from a variety of databases [75]. Efficient big data management is critical for organization survival and success because it offers a competitive advantage [76], providing quick insights into the “3Vs” (volume, velocity, and variety) on an unprecedented scale. According to Laney [77], accessing high volume, velocity, and variety of information requires quick, effective, and efficient processes, to ensure timely decision-making and enhance firms’ decision-making performance [33]. Managing and acquiring a large volume of data from various databases at a rapid pace is critical and requires large-scale and brisk data-mining. Data-mining management mainly includes identifying, visualizing, storing, and analyzing the data [78, 79]. Obtaining and processing such massive data with time limitations is an organizational challenge. In this context, big data management becomes even more challenging with the addition of two more “Vs” (i.e., veracity and value) [80, 81]. But it brings authenticity and value to the table that were missing from its early definition. The inclusion of these two assets in the phenomenon of big data enables management to retrieve and analyze authentic data promptly. With information technological advancement, the BDA process has become the paradigm for knowledge management [32], competitiveness [59], decision-making quality [2], and performance [59]. In the BDA context, this topology enhances organization capabilities, leading management to perform its functions effectively and efficiently, especially BDA planning, investing, coordinating, and controlling functions, or BDAMC [15, 82].

The impact of BDA on business is multifarious and cross-industrial [83,84,85]. In an intensively competitive environment, employing BDA processes helps organizations outperform their competition and enhance their performance [71, 76]. It also serves as a core source of authentic and valuable information to support decision-making and strategic-management processes [86]. According to Liu [84], it is the sole difference between high- and low-performing firms. Liu [84] finds a forty-seven percent drop in cost and an eight percent rise in revenue from employing BDA. Amazon.com also reports that sales increased by thirty-five percent, due to online purchase suggestions based on BDA [87]. Similarly, Ward [88] suggests that employing BDA processes enabled general engineering to save 66 billion dollars over 15 years. Deployment of BDA processes depends on firms’ IT capabilities, which Bharadwaj [89] defines as a "firm’s ability to mobilize and deploy IT-based resources with other resources and capabilities." The researchers argue that firms’ investments in information systems can support measuring their IT capacities [89,90,91]. Although these investments are essential, and the strategic-management literature views them as a source of competitive advantage, they do not necessarily lead organizations toward the intended outcomes [8]. Organizations must devise dynamic strategies and establish relevant management capabilities to exploit such investments’ full potential [2]. McAfee et al. [35] also support this research stream and stress developing management-related skills and capacities to leverage BDA. Barton and Court [92] argue that management capabilities (planning, investment, coordination, and control) are essential for quick and timely decision-making. In this regard, we argue that BDAMC enables firms to sense and seize the available market opportunities and facilitate transforming existing processes that may lead them toward enhanced innovation performance. According to Shamim et al. [70], the current understanding of big-data-related management capabilities is limited, and exploring the association between BDAMC, DC, and innovation performance will extend that understanding.

2.3 Dynamic capabilities (DC)

Organizational success largely depends on the competitive edge that results from strengthening built-in responses for adapting to change in the external environment. Researchers highlight the importance of built-in responses to embrace those environmental changes [59], and they hinge upon organization capabilities, i.e., DC that stresses competitive advantage by proactively engaging with the external market-environment changes [2]. Drnevich and Kriauciunas [93] also recommend building DC in a highly competitive, uncertain, and changing business environment. Teece et al. [41] originated DC from the resource-based view of strategic management that refers to the firms’ capacity to integrate, build, and configure internal and external competencies to adapt to rapidly changing business environment. Moreover, DC enables the organization to use resources to their full potential, yielding desired outputs and competitiveness [94]. Building DC can be part of the strategic-management process that serves organizations in the longer run, a function of sensing, seizing, reconfiguring, and learning [62]. Sensing enables the firm to collect information about customers, competitors, and potential opportunities. Seizing stimulates the introduction of new products by exploiting sensed opportunities. Reconfiguring refers to maintaining a competitive advantage by transforming the existing process. Learning means sticking with best practices to achieve competitiveness [41, 44, 62, 95,96,97].

In a systematic review of big data and DC, Shams and Solima [98] highlighted the significant progress that DC had made, especially with two important and interrelated management philosophies [99, 100]. The first is identifying market drivers that assess the business and socioeconomic environment in which firms operate, enabling firms to envisage future opportunities and devise proactive strategies. The second philosophy is the resource-acquisition view, which refers to acquiring and allocating resources to achieve competitive advantage. Research identifies the significance of big data for acquiring knowledge of opportunities and threats in the external environment and facilitating firms’ engaging in value-creation processes [63]. BDA also fosters the decision-making quality and capacity of a firm by providing valuable information during strategic-management processes [1], which potentially may foster DC. Prior research associates DC with transforming the firms’ resources, enhancing operational efficiency and core competencies, and subsequently boosting economic performance [101]. Weerawardena et al. [102] argue that compared to the resource-based and industrial-organization views, the DC view plays a crucial role in supporting decision-making processes and devising and implementing competitive strategies [33]. Accordingly, Teece [43] argues that DC-view sensing, seizing, transforming, and learning facilitate performance and develop competitive strategies. Moreover, greater environmental uncertainty, market instability, and continuous change raise the need to fortify DC to achieve a competitive edge [103]. Correspondingly, DC supports developing organizational capabilities and resources, to produce desired outputs that may foster innovation performance.

2.4 Strategic alignment

Practitioners and researchers are paying great attention to realizing strategic alignment, operationalized as a suitable strategic fit among business and information-system strategies [104]. The strategic-alignment concept arises from the “strategic alignment model,” which comprises information-technology strategies, business strategies, information-technology infrastructure and processes, and organizational infrastructure and processes [105]. Grounded on the attributes of strategic management, its conceptualization as a strategic fit among business strategies, information-technology infrastructure, and processes [106] is essential to fostering firms’ performance, innovativeness, and competitiveness [107]. These days, achieving strategic alignment is top management's priority because its role is not limited to technology or software. It categorically fills the gap between information systems and business strategies [108], playing a crucial role at strategic and operational levels, to create value for organizations [109]. Yet, relying only on investments in information systems is insufficient to obtain value [58]. Organizations must establish management capabilities to find a strategic fit between information systems and business strategies that subsequently may enhance firms' DC. Previous research extensively relates strategic alignment with performance [106, 110, 111]. Researchers also explore strategic alignment as both an outcome [112, 113] and an antecedent [106]. However, the mediating role of strategic alignment is an under-researched phenomenon needing further investigation. Thus, we extend the existing literature by examining the mediating role of strategic alignment between BDAMC and DC.

2.5 Research model and hypotheses development

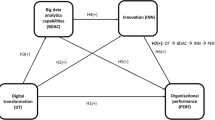

Drawing on DC and social capital views, we propose the model that appears in Fig. 1. We argue that firms must establish BDAMC to accomplish DC and innovation performance. BDAMC is a higher-order construct comprising BDA planning, investment, coordination, and control. We affirm that the nexus of BDAMC, social capital, and strategic alignment may enhance the firms’ DC. We assume that this nexus of capabilities fortifies firms’ sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming capabilities, ultimately improving innovation performance.

2.5.1 Big data analytics management capabilities and dynamic capabilities

To achieve a competitive edge in complex and continuously changing business environments, firms strive for different prospects that update and transform their processes. Their capacity to adapt to change heavily depends on their ability to sense upcoming opportunities and threats, seize the sensed opportunities to transform existing processes according to market needs, and learn from past experiences (DC). In this respect, the management literature prefers BDA for facilitating DC [114] as it provides better insight into identifying upcoming opportunities and threats [15]. Operationalizing BDA in the organizational context enhances management capabilities that foster firms’ decision-making quality [1]. This novel perspective on BDA fosters decision-making performance [33] by converting a huge amount of raw data into information. Recent studies acknowledge the importance of big data and associate it with performance [115], competitive performance [59], innovation [8], and circular-economy performance [37]. Moreover, BDA technologies process a massive amount of raw data into information in no time, serving with speed, efficiency, and effectiveness to adapt to changes in the external environment and seize opportunities [116]. However, firms' transformation capacity depends not solely on technology but also on the extent of firms’ developing BDA capabilities [68], especially BDAMC. Transformation capacity heavily depends on management capabilities, i.e., planning, investment, coordination, and control. BDAMC helps firms to develop a data-driven culture [117, 118].

The implementation of BDA in real-time organizational scenarios offers novel ways of identifying opportunities available in the external market environment, by acquiring and analyzing heterogeneous data [119]. Converting a huge amount of diverse data into information generates previously unachievable benefits. For example, Southwest Airlines used BDA to better understand customer needs not sensed otherwise, developing a novel insight into customer needs regarding interrupted flights, reservation details, and beverage and food priorities, to serve them better. On social media, airlines also find peoples’ views about the airline itself, its competitors, and the whole industry. This helps airlines transform processes to enhance customer satisfaction [120]. Effective management of big data fosters organizations’ decision-making capacity, enhancing their decision-making quality [2]. Accordingly, big data management capabilities enable firms to create value from big data [63], enhancing business performance [71]. In this regard, we argue that BDAMC enables firms to better develop insight into market needs and demands, to enhance sensing, seizing, transforming, and learning capabilities. Fortifying BDAMC facilitates developing organizational strategies that accept radical changes in existing processes [121]. In fact, BDAMC boosts quality decision-making by proactively availing the company of opportunities and preparing it to tackle threats. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H1

Big data analytics management capabilities will have a positive effect on dynamic capabilities.

2.5.2 The mediating role of social capital

A wide range of research explores the emerging field of networks and ties from different perspectives, in the context of acquiring scarce external resources [122, 123] crucial to boosting organizational capabilities. The literature regards these networks and ties as social capital, referring to the links and connections that organizations establish via personal relationships [124]. These critical organizational relationships, networks, and connections with stakeholders enable and support knowledge and resource acquisition [52]. The literature reports two dimensions of social capital, i.e., business ties and political ties [125]. Business ties are management social connections and relationships with the management of other organizations, such as suppliers, customers, and competitors [51]. Political ties refer to the organizations, relationships, and links with political leaders and government agencies [51]. Social capital includes management boundary-spanning activities that enable organizations to access valuable resources and information not easily available to others, which may serve as a competitive edge [126]. These activities enhance firm capacity to acquire and deploy knowledge resources and, thus, achieve competitive advantage [127]. Developing strong social connections is essential; they enable organizations’ access to valuable information, upcoming or favorable government policies, and financial resources in the form of subsidies and tax deductions [128]. Organizations' strong social relationships and networks that provide knowledge and resources during the strategic-management process make them more innovative than competitors [52]. Bhatti et al. [122] find a positive and significant association between knowledge-sharing and social capital. BDA fosters knowledge acquisition and sharing, at an unprecedented scale and from diverse sources [115, 129]. We assume a strong possibility that BDAMC elevates organizational social capital by facilitating knowledge-management processes. Moreover, BDA shares information between stakeholders on a large scale and at a rapid pace [60], developing strong connections and trust between firms and their stakeholders, i.e., suppliers, competitors, customers, and government agencies (social capital). Furthermore, BDA enables firms to identify opportunities available in the external market [130]. During these opportunity-identification processes, firms realize the need to establish relationships with different stakeholders to achieve specific organizational goals. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H2

Big data analytics management capabilities will have a positive effect on social capital.

In the BDA context, developing strong BDAMC is critical because it triggers organizational capabilities to identify unexplored gaps and opportunities [116]. Building strong BDAMC enhances organizations’ capacity to identify emergent market opportunities and threats [59, 131]. BDA acquires data from heterogeneous sources and converts it into information to support decision-making processes [58, 68, 79]. Furthermore, BDA strengthens relationships between stakeholders, via a quick flow of information, and identifies the need to formulate strategies to build substantial social capital. For instance, the firm hires individuals with a political background, important agents of knowledge management, as top management. [132]. Building social capital enables firms to access tangible and intangible resources vital to fostering performance [133]. By fortifying the BDAMC and social capital, firms develop network capabilities [53], enhancing the organization's sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming potential (DC). Moreover, BDA establishes a data-driven culture by facilitating the rapid acquisition and sharing of information [117]. We assert that the translation of BDAMC into a firm’s DC may depend on the degree to which the firm establishes social capital. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3

Social capital will mediate the association between big data analytics management capabilities and dynamic capabilities.

2.5.3 The mediating role of strategic alignment

Developing strong BDAMC not only enhances firms’ DC but may also foster strategic alignment, the harmony between the firms’ information-system strategies and business strategies [113]. Researchers refer to strategic alignment as the extent to which an organization's business strategy articulates its vision, objectives, and plans, and its information-system strategy facilitates them [57], constituting an appropriate strategic fit between business and information-system strategies [104]. Prior research associates strategic alignment with organizational success and competitiveness [55, 107]. However, research also reports many projects that failed to implement an information-system structure in the organization [134, 135] and consequent huge financial and human-resource losses [136]. We argue that this failure is due to the firm’s information-system strategies and business strategies not complementing each other. Strategic alignment is an emerging field of research. In today’s complex and continuously changing environment, achieving strategic alignment is top management’s primary concern [56]. We assert that BDAMC may work as a critical antecedent of strategic alignment because it provides quick and authentic information and facilitates the strategic-management process. Moreover, timely access to information also helps top management in devising complementary information-system and business strategies. Accordingly, BDA builds a data-driven culture that helps organizations to transform existing processes, to adopt change. BDA enables rapid organization access to authentic and valuable information. This facilitates the organization’s formulating and altering its strategies to establish a strategic fit between information-system and business strategies [106]. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H4

Big data analytics management capabilities will have a positive effect on strategic alignment.

Strategic alignment is the harmony among firm processes, systems, and capabilities [137], to achieve a strategic fit between the firm’s information-system strategy and its business strategy [54]. BDAMC supports firm efforts to find the strategic fit by acquiring and sharing information; thus, BDAMC facilitates strategic-management processes [138] and enhances decision-making quality [33]. Moreover, developing BDA capabilities increases firms’ ability to transform processes and enable them to reshape products and services, to adapt to changing market needs [59]. However, to fully sense and seize the potential opportunities along with enhancing learning and transforming capacities, firms require not only data and technology but also strategy-making skills to interpret the data and devise appropriately aligned strategies also formulated to promote alignment [68]. Thus, BDAMC facilitates decision-making processes and diffuses the firm's data-driven culture [117]. According to Shao [113], a change in business strategy requires a change in the information-system strategy, making strategic alignment a challenge. In this respect, strategic alignment is a continuous process of aligning the firm’s business and information-system strategies to adopt change from the external market environment [139]. This enhances the firm’s strategic agility, which subsequently may foster its DC. Hence, we assert that the association between BDAMC and DC depends on the extent to which a firm develops strategic alignment; thus, we hypothesize:

H5

Strategic alignment will mediate the association between big data analytics management capabilities and dynamic capabilities.

2.5.4 Dynamic capabilities and innovation performance

For decades, organizations have searched for different prospects for acquiring innovation because it is essential to achieving superior firm performance [140] and success [141]. A Google search on “innovation” returns "a new method, idea, or product" [142]. According to Dodgson et al. [143], it is successful implementation of a new idea resulting from organizational processes of combining various resources. In general, understanding the term means thinking out of the box and, thus, serving organizations’ competitive advantage [140]. Moreover, innovation is a collective process between external and internal partners, leading the organization toward new and improved products and services [144, 145]. Prior research linked innovation performance with value creation, profit, share price, growth, and customer satisfaction [146,147,148]. However, this approach receives criticism for its negative impact on society and the environment. Hence, it has become more challenging to develop products and services that are not only unique but also environmentally friendly and socially acceptable [149, 150]. Thus, despite being a widely studied phenomenon, the antecedents of innovation performance always attract the attention of researchers and practitioners. For instance, Ghasemaghaei and Calic [8] find that big data characteristics are antecedents of a firm’s innovation performance. In this regard, we argue the strong possibility that DC may enhance the firm’s innovation performance because DC is the precursor of strategic and organizational routine, which helps top management to transform organizational resources by devising unique strategies for value creation [151, 152]. Helfat and Winter [153] illuminate the significance of DC for producing outcomes, in terms of innovation and business transformation. Moreover, DC creates, fosters evolution, and recombines firm resources to achieve competitiveness. For instance, Toyota implemented superior product-development skills to achieve competitive advantage [154]. More importantly, sensing enables firms to identify potential opportunities and threats; seizing allows firms to avail themselves of sensed opportunities; learning helps firms to follow best practices; transforming supports firms' efforts to reconfigure their existing processes to develop unique products and services. These are essential factors that make firms’ processes more innovative. Hence, we hypothesize:

H6

Dynamic capabilities will have a positive effect on innovation performance.

3 Methodology

This study used a matched-pair survey instrument (two questionnaires) to collect data about constructs. Straub et al. [155] recommend survey-based research because it serves generalizability, is easily replicable, and explores several variables concurrently [156]. Moreover, it is an accurate and systematic way of capturing the association among variables [59]. In this regard, we formulated two questionnaires to capture respondent feedback. Questionnaire One comprised twenty-one item-statements about BDAMC and firm-attribute-related statements, whereas Questionnaire Two comprised thirty-two item-statements about social capital, strategic alignment, DC, and innovation performance. A seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree (7)” to “strongly disagree (1),” was used to record the respondents’ feedback. In a pilot study, we contacted ten respondents by phone to ensure the questionnaire content was valid, clear, and understandable. We incorporated suggested changes in the final versions.

3.1 Variables measurement

3.1.1 Big data analytics management capabilities

BDAMC is a higher-order construct comprising four subdimensions, i.e., BDA planning, investment, coordination, and control. These subconstructs included four, five, four, and eight item-statements, respectively. We adapted BDAMC items from the study of Wamba et al. [15]. Examples of item-statements were, "we enforce adequate plans for the utilization of business analytics”; “when we make business analytics investment decisions, we project how much these options will help end-users make quicker decisions”; “in our organization, business analysts and line employees from various departments regularly attend cross-functional meetings”, and “we constantly monitor the performance of the analytics function.”

3.1.2 Social capital

Social capital consists of two subdimensions, i.e., political ties and business ties. Each had three questionnaire item-statements adapted from the study of Zhang et al. [125]. Examples of the statements were, "management of our organization has utilized personal ties, networks, and connections with the political leaders at various levels of the government," and "management of our organization has built good relationships with the management of the customer’s organizations."

3.1.3 Strategic alignment

The construct of strategic alignment comprised three item-statements adapted from the study of Shao [113]. An example of the item-statements was, "our business strategy and IS strategy are closely aligned."

3.1.4 Dynamic capabilities

According to Teece [44, 62], DC is the function of sensing, seizing, and transforming/reconfiguring. Later researchers add organizational learning. Nevertheless, DC is a higher-order construct comprising sensing, seizing, leaning, and transforming. We adapted DC from a previous study of Pavlou and Sawy [157]; Wilden et al. [158]. Sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming had four, four, five, and four item-statements, respectively. An example of the item-statements is, “in my organization, we have introduced new or substantially changed marketing methods or strategies.”

3.1.5 Innovation performance

Innovation performance comprised six item-statements. We adapted innovation performance from the study of Gunday et al. [159]. An example of the item-statement is, "different types of innovations are introduced for work processes and methods in our firm."

3.2 Sample design and data collection

The population frame of the study included manufacturing and logistics sectors located in Pakistan. We chose these sectors because, first, each industry (logistics and manufacturing) contributes approximately 14 percent to Pakistan's GDP [160,161,162,163]. Second, logistics are service providers and manufacturing industries producing tangible products. Both services and products are crucial components of innovation performance. Additionally, both sectors play a pivotal role in creating employment. The manufacturing sector contributes 13.8 percent [164], while the logistics sector produced three million jobs in 2018 [160]. Appropriate sample selection is crucial for the applicability of any study. Thus, the criteria for company inclusion in the sample comprised four points. First, the company had to be recognized by the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSE), Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCCI), Database of Industry Association of Pakistan, Pakistan International Freight Forwarders Association (PIFFA), and All Pakistan Shipping Association (APSA). Second, it must have had a formal organizational structure. Third, it had to utilize big data practices. Fourth, it had available contact details. The above criteria qualified 597 companies located in Pakistan's industrial hubs (Sialkot, Lahore, Faisalabad, and Karachi).

We sent two questionnaires to each company, either electronically (using email and WhatsApp) or by physically visiting the company, to collect feedback from the sample. The targeted respondents to Questionnaire One were chief information and technical officers, while Questionnaire Two collected feedback from chief executive and operations officers. We attached a cover letter to each version of the questionnaire, explaining the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, and response confidentiality. Podsakoff et al. [165] recommended these methods as remedies for common method variance (CMV). After three rounds of follow-up via phone calls and personal visits to companies to eliminate the outliers and incomplete responses, we received 149 matched-pair responses. The responses from 149 firms well surpassed the ten-times rule of Barclay et al. [166] and Kline's [167] twenty-times rule for minimum sample for partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Hair et al. [168] also recommended the ten-times rule for analysis using PLS-SEM. Thus, the study concluded that the responses of 149 firms were appropriate and produced highly applicable results.

4 Analyses tools and results

The study used Smart-PLS v3.3.2 and IBM SPSS 25 software for data assessment. We adopted the variance-based PLS-SEM approach because, first, it can handle both measurement and structural model assessment concurrently [168]. Second, this approach is more suitable for higher-order constructs [168]. Third, the literature supports PLS-SEM use in a model that has both direct and indirect relationships [169]. Fourth, the responses in our study exceeded the suggested minimum requirements for the structural model [168]. Fifth, PLS-SEM offers more advanced tools to assess reliability and validity analysis [170]. Last, prior studies prefer the PLS-SEM approach [171, 172]. Hence, PLS-SEM is a more suitable approach to test the proposed model that appears in Fig. 1. The research presents the outcomes of the reflective measurement model and reflective structural model, as directed by Hair et al. [173]. Furthermore, to ensure the quality of the data, the researchers conducted a common method bias test, a non-response bias test, and data careening before other reliability and validity assessments, as under:

4.1 Common method variance (CMV) remedies

The study used procedural remedies (i.e., obtaining data about predictor and criterion constructs from different sources, ensuring response anonymity, and eliminating item-statements ambiguity) to mitigate the possible occurrence of CMV. Podsakoff et al. [165] recommend these remedies to remove CMV at the research-design stage. Additionally, the study used recommended statistical tools to ensure CMV did not contaminate the collected data, the major concern associated with survey-based research [174]. In this regard, Kock [175] referred to the collinearity assessment as the most reliable technique for assessing CMV. Smart-PLS’s variance inflation factor (VIF) results fall under the threshold of 3.3, suggesting that CMV is not a problem with our study, using the threshold that previous research suggested [173, 175]. The VIF values of item-statements appear in Table 2. Furthermore, we employed Harman's [176] single factor test, using IBM SPSS 25 to assess common method bias. Results (29.79%) fall below the threshold of fifty percent, showing that common method bias is not a concern in our study.

The further analyses start with the firms’ attributes, i.e., types of manufacturing and logistics industry, age and size of the company, and firm experience with big data, which Table 1 presents. In the manufacturing industry, the largest response came from textile companies (14.1%), followed by food and beverages (12.6%), pharmaceuticals (10.7%), electronics (9.4%), automobiles and cement (6.7%), chemicals (5.4%) and fertilizer (4.7%), while in the logistics industry, the study received the largest responses from freight forwarding (18.8%), followed by food and IT-networking (5.4%). Complete details of firm attributes appear in Table 1.

4.2 Measurement model assessment

We followed previously established guidelines to conduct the measurement model assessment [173]. We assessed the reliability and validity of constructs via content validity, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity assessment. The details of reliability and validity analysis appear in Table 2, and we discuss them below:

4.2.1 Content validity assessment

We used indicators’ factor loadings to ensure the content validity of the constructs. As a general rule of thumb, loadings above 0.708 are recommended [173], which means that a construct explains 50 percent of the variance in respective indicators. Results show that all indicators’ loadings are above the lower-bound limit of 0.708, except CON8 (0.69), LRN4 (0.60), TRF1 (0.65), and IP1 (0.64), as Table 2 shows. However, Hair et al. [168] suggest that loadings between 0.4 and 0.7 are also acceptable.

4.2.2 Internal consistency assessment

The research ascertains the latent constructs' internal consistency via Cronbach's alpha (α) and Jöreskog's [177] composite reliability (CR), referring to the mutual consistency among indicators of the same construct. According to Hair et al. [173], α and CR values ranging from 0.7 to 0.95 are acceptable and fall in the “satisfactory to good” category. The study constructs’ α and CR values ranged from 0.749 to 0.879 and 0.842 to 0.904, respectively, in the “satisfactory to good” category. This means that the constructs indicators have adequate mutual consistency. Detailed results of α and CR appear in Table 2.

4.2.3 Convergent validity assessment

The average variance extracted (AVE) was used to assess the convergent validity for latent constructs. AVE is the extent to which the constructs’ values converge to explain the respective construct indicators' variance. The suggested acceptable lower-bound limit for AVE is 0.5 [178, 179]. The AVE values above 0.5 mean that constructs explain 50 percent of the variance among respective indicators. The constructs’ AVE values depicted satisfactory results, ranging from 0.503 to 0.758, as Table 2 shows.

4.2.4 Discriminant validity assessment

Discriminant validity (DV) is the extent to which a construct differs from the other model constructs. The study safeguards the DV by comparing the square root of constructs’ AVEs with their correlations. The square root of a construct’s AVE higher than the correlations of the remaining constructs means that the construct is different from the other constructs [180,181,182]. The literature regarded this comparison as the Fornell and Larcker criterion. Results of this criterion appear in Table 3, where bold values are the square roots of constructs’ AVEs higher than the correlations of the constructs. This shows adequate DV among constructs. The study also used the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio to assess the DV among constructs. According to Henseler et al. [183], it is a modern tool to evaluate the constructs’ DV. The HTMT results of constructs fall under the upper-bound limit of 0.85, as directed [168, 184]. Thus, this study established sufficient DV. The HTMT results appear in Table 4.

This research followed the four-step instructions of Hair et al. [173], to ascertain the reliability and validity of the data. These steps include assessing (1) content validity, (2) internal consistency, (3) convergent validity, and (4) discriminant validity. After validating the measurement model, the study moved to the structural model assessment.

4.3 Structural model assessment

Structural model assessment includes assessing constructs’ explanatory power (R2), predictive relevance (Q2), and path coefficients significance. The Smart-PLS's bootstrapping at a subsample of 5,000 was initiated to evaluate the proposed model significance and hypotheses assessment [173, 185,186,187,188]. The detailed PLS-SEM analysis results in terms of R2, P-values, and path-coefficient (β) values that appear in Fig. 2. The hypotheses assessment details, including latent constructs’ t-statistics, β-values, and p-values, appear in Table 5. At the same time, R2, Q2, and GoF assess the proposed model fitness, discussed under the “Model fit assessment” heading.

The results of PLS-SEM reveal that all six study hypotheses are empirically supported. More precisely, the study found that BDAMC has positive and significant relationships with DC, social capital, and strategic alignment (β = 0.544; t-val = 7.629; p-val = 0.000), (β = 0.647; t-val = 11.103; p-val = 0.000) and (β = 0.505; t-val = 6.973; p-val = 0.000, respectively), providing support to H1, H2, and H4. Results also revealed that DC has a positive and significant impact on innovation performance (β = 0.579; t-val = 8.272; p-val = 0.000), providing support to H6.

4.4 Mediation assessment

The study assumes that social capital and strategic alignment positively mediate the relationship between BDAMC and DC. Analyzing the mediating effect between endogenous and exogenous constructs in the PLS-SEM starts by analyzing the direct effect [168, 189]. After analyzing the direct association, the results of mediating analyses revealed that both social capital and strategic alignment partially mediate the association between BDAMC and DC, with (β = 0.127; t-Val = 2.299; p-val = 0.024) and (β = 0.088; t-Val = 2.259; p-val = 0.024), respectively, thus, providing support to H3 and H5. The outcomes of the mediation analysis appear in Table 5.

4.5 Model fit assessment

The study ensures the proposed model fitness via the coefficient of determination (R2) [190], predictive relevance (Q2) [191, 192], and goodness of fit (GoF) [193], as Hair et al. [194] suggest that assessing the model based only on R2 is not a good approach. The R2 values depict the exogenous variable explaining 63 percent variance for DC, 41 percent for social capital, 25 percent for strategic alignment, and 33 percent variance for innovation performance. According to the criteria (0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 are substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively) [194], these values of R2 represent substantial-to-moderate explanatory power for endogenous variables. Furthermore, the study uses Q2 to assess model fitness. As a general rule of thumb, Q2 greater than zero indicates that the model has predictive relevance for latent endogenous variables [186]. In this respect, Smart-PLS’s blindfolding function at an omission distance of 7 was routed. Results show that the Q2 values of endogenous variables DC, social capital, strategic alignment, and innovation performance are 0.214, 0.241, 0.171, and 0.154, respectively. According to set criteria [186], the endogenous variables have moderate predictive relevance; thus, the model has adequate predictive relevance. Additionally, the study calculated GoF to ensure model fitness, the square root of the mean of AVE*R2. The GoF value of the model is 0.506, which falls in the large category, as directed [195]. R2, Q2, and GoF details appear in Table 6.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The scholarship on BDA is continuously growing, as it is a significant source of valuable data to facilitate strategic-management and decision-making processes [37]. It plays a prominent role in fostering firms' abilities to foresee coming opportunities and threats. This enables firms to proactively adapt to changes in the external and internal environment, building a competitive edge [15]. Researchers Hargreaves et al. [73] and Vassakis et al. [74] also acknowledged its salient role in addressing several socioeconomic, managerial, and ecological problems. Researchers studied BDA association with firm-level and team-level capabilities [59, 71] and established its association with performance and decision-making quality [12, 115]. Still, the hype around big data is continuously growing because, first, understanding is limited [59, 78, 196]; second, the literature on big data is mainly drafted by consultants who lack a theoretical base and contextual understanding [58]; third, it is a complex phenomenon [197]; fourth, a small number of organizations explore big data to its full potential [197, 198]. In this context, Henke et al. [31] report that only twenty-five percent of firms successfully operationalize big data and realize its intended outcomes. During BDA management, firms face different challenges that negatively influence contemporary decision-making processes and essential management functions, i.e., BDA Planning, investment, coordination, and control. Consistent with Shamim et al. [63], we backed the scholars who argue that organizations must develop related management capabilities to create value from big data. Accordingly, we affirm that big data is an indispensable resource, but to leverage big data to create value (innovation performance), firms must develop related management capabilities. Thus, we stress BDAMC and attempt to fill research gaps by empirically exploring the indirect association of BDAMC and innovation performance. Findings reveal a positive association between them, consistent with previous studies [34, 63].

Furthermore, studies report that despite companies' eagerness to invest in big data, results notably differ in terms of performance [12, 199]. In this context, the question of pathways and mechanisms through which big data yields intended outcomes is crucial but under-researched. Mikalef et al. [59] also identify the mechanisms through which BDA produces outcomes as needing further investigation. Consistent with the argument of Wamba et al. [15], this study argues for an indirect association between BDA and outcomes. Thus, we explore the association between BDAMC and innovation performance via DC. Over the past few years, DC has attracted researchers' and practitioners' attention. Establishing DC is pivotal to achieving superior performance [200] and adapting to a rapidly changing business environment [44]. Teece [64] highlights the importance of DC at the organizational level and suggests that these capabilities facilitate firms’ establishing inimitable resources, enhancing firm outcomes. The foundations of DC are inimitable processes, skills, mechanisms, and procedures [64]. DC research is one of the main streams in current strategy research [201], and organizations are seeking different prospects for building DC. Hence, the antecedent that serves DC is an unfading research topic. Our study advances this stream of research by exploring the direct and indirect (social capital and strategic alignment) effects of BDAMC on DC.

The enormous attention researchers and practitioners have paid to the phenomenon of BDA and DC largely inspires our study. Consistent with the argument of Shamim et al. [33] and Awan et al. [37], we state that BDA indirectly produces outcomes. Drawing on the integrative approach of DC and social capital views, we establish and explore the associations among constructs of BDAMC, strategic alignment, social capital, DC, and innovation performance. Our study enriches the current understanding by establishing the associations among the constructs appearing in Fig. 1. The proposed model has three higher-order constructs, namely, BDAMC, social capital, and DC. Empirical results show that BDA control with (β = 0.796) contributes more to the BDAMC, followed by coordination (β = 0.784), planning (β = 0.772), and investment (β = 0.719). Both political and business ties contribute almost equally to social capital with (β = 0.890) and (β = 0.899), respectively. Accordingly, second-order construct transforming contributes more to DC with (β = 0.805), followed by learning (β = 0.786), seizing (β = 0.778), and sensing (β = 0.713). Results also depict social capital with a stronger indirect relationship between BDAMC and DC (β = 0.127), compared to strategic alignment (β = 0.088). We next discuss theoretical and practical implications of the study.

5.1 Theoretical implications

The study's main objective is to empirically explore big data and DC phenomena, as the literature reports the lack of current understanding [202], especially regarding pathways and mechanisms through which big data creates quantifiable business value (innovation performance). In this regard, based on DC and social capital views, this study proposed a model explaining the pathways through which BDAMC benefits the organization. Accordingly, we argue that BDAMC is the essential knack that enables the organization to use other capabilities to their full potential, to yield desired outputs of enhanced innovation performance. The study argues that the understanding of BDA capabilities is anecdotal. To fully realize the benefits from big data investments, organizations must develop BDAMC. We filled these gaps in the literature by testing the BDAMC model in the organizational context. This study significantly expands the understanding of big data by explaining how BDAMC enhances DC, which subsequently fosters innovation performance. Following are the four significant theoretical contributions of the study.

The study makes a theoretical contribution by building a BDA model based on DC and social capital views rather than a resource-based view (RBV). Previous research studies the phenomenon of BDA through the lenses of RBV [15, 59] and a knowledge-based view [37, 70]. However, we build our arguments based on DC and social capital views. RBV only focuses on heterogeneous resource advantage and provides no suitable explanation to adapt to the continuously changing business environment. Accordingly, RBV provides insufficient information about the utilization of the resources. In comparison, DC and social capital views not only stress the acquisition of resources but also focus on building competitive advantage, dynamism, and networking capabilities, facilitating organization resources utilization and transformation capability to cope with the rapidly changing business environment. Teece et al. [41] also support this by arguing that resource acquisition is not the main point. Efficient utilization of these resources to achieve desired results is most important. Similarly, Gutierrez-Gutierrez et al. [203] suggest that in a continuously changing business environment, the transformation of an organization's existing processes and capabilities relies heavily on management, which is the primary argument of the DC view. Therefore, we expand the research stream of the DC view [41, 44] and the social capital view [51, 125, 204], finding that BDAMC directly and indirectly fosters the organizations’ sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming capabilities (DC), consequently enhancing its innovation performance.

The study expands knowledge by affirming that having resources and technology is not enough unless organizations develop management capabilities to deploy them. In the modern era of the technological paradigm, organizations have access to enormous data. However, organizations cannot achieve intended outcomes with just their access to big data. Organizations must build BDAMC to create value from it. Bello-Orgaz et al. [78] also report that BDA has great potential to address diverse contemporary management problems. In this respect, our study advances understanding by establishing the link between BDAMC and DC, unlike previous researchers who linked BDA with performance [15], competitive performance [59], decision-making capability [2], circular-economy performance [37], and employee ambidexterity [63]. Hence, this study extends the literature on BDA by finding that BDAMC significantly enhances the organization's DC. We affirm that BDAMC, in terms of BDA planning, investment, coordination, and control, facilitates data-driven decision-making and adapting to changes proactively. It also enables the organization to foresee the upcoming opportunities and threats, which ultimately lead organizations toward the transformation of existing processes and operations.

Our study advances understanding by asserting that BDAMC enables organizations to build DC by achieving strategic alignment and social capital, unlike previous studies that investigate the association between big data and outcomes through data-driven strategies [71], decision-making quality [37], BDA capability [33], and knowledge creation [70]. Organizations generate benefits from BDA because it enables them to look into the data from unique perspectives that serve the competitive edge. However, the operationalization of BDA in the organizational context is a complex process that requires huge investment and organizational commitment. Ross and Beath [198] report that a limited number of companies have managed to exploit big data investments to their full potential [12]. We argue that the reason is that organizations’ business and information-system strategies are not aligned and complementary. Accordingly, Ravichandran [38] argues that ICT-based capabilities require other capabilities to generate benefits. In this research stream, we argue that organizations may exploit big data investments up to their full potential via strategic alignment and social capital. Organizations developing strong BDAMC facilitate devising and altering strategies that top management formulates. More precisely, BDAMC enables the organization to formulate complementary information-systems and business strategies. It also helps the organization identify the need to build social links to gain valuable and scarce resources. Notably, BDA enhances strategic alignment and social capital through unique perspectives. This ultimately elevates the sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming capabilities of an organization. This study's findings are consistent with the above argument, which shows that strategic alignment and social capital partially mediate the relationship between BDAMC and DC. Last, organizations have long strived to be more innovative than others, to achieve a competitive edge and superior performance. Thus, prior research, such as that of Tian et al. [205], paid great attention to innovation enhancement. In this regard, prior research by Bereiter [206] and Gassmann and Zeschky [207] thoroughly studied product and process innovation performance. However, they ignore overall innovation performance. Moreover, the different prospects through which organizations can elevate innovation performance is an evergreen area of research. In this research stream, this study asserts that organizations can foster their innovation performance in terms of fortifying sensing, seizing, learning, and transforming capabilities. The study's findings expand this stream of research and provide empirical support to the above argument by depicting DC as significantly enhancing organizations’ innovation performance.

5.2 Managerial implications

Along with theoretical implications, our study presents significant practical implications. The study's findings clearly indicate the BDA is not just IT investments but much more. It is essential for developing organizational capabilities and establishing a data-driven decision-making culture, which subsequently enhances organizational performance, especially innovation performance. For the organization to create business value from big data, acquiring human resources with sound technical and managerial skills is critical. The impact of resources and their efficient utilization enables the organization to develop BDAMC, which requires commitment from top-level management.

The implementation of big data in the organizational context is a complex process, and the financial risk associated with it is huge. The BDAMC model of the study clearly states that organizations must develop management capabilities, to minimize the risk associated with investments in big data. More importantly, this will help the organization utilize its investment, resources, and capabilities to full potential. Notably, the study has great importance for consultants as well. Consultants and top management involved in BDA implementation can gain a clearer view of mechanisms and pathways through which they can implement BDA in the organizational context. Furthermore, our study’s assessment shows that the association between BDAMC and business value, in terms of innovation performance, is indirect. Results clarify that organizations must develop related BDAMC that substantially influences their DC, subsequently enhancing innovation performance. Finally, the organization’s top management must continuously strive for harmony between business strategies and information-system strategies and establishing social capital to access valuable resources. We infer this from the results depicting strategic alignment and social capital significantly impacting the association between BDAMC and DC.

6 Study limitations and future research directions

Along with its contributions, our research has some limitations that open up future research prospects. We researched a specific area of BDA; future research could look into other BDA domains. Second, this study empirically tests the proposed model on the data collected from the manufacturing and logistics sectors. Future research could take place in other sectors. We conducted this research in the Pakistani context; a cross-country comparative study could inspire future research. Last, to assess endogenous and exogenous variables' association, our study reviews only English literature about them. However, only twenty percent of people speak and understand English [163]. Future research could consider other languages' literature to test the BDA impact on different factors.

Abbreviations

- BDA:

-

Big data analytics

- BDAMC:

-

Big data analytics management capabilities

- DC:

-

Dynamic capabilities

References

Li L et al (2022) Evaluating the impact of big data analytics usage on the decision-making quality of organizations. Technol Forecast Soc Change 175:121355

Shamim S et al (2019) Role of big data management in enhancing big data decision-making capability and quality among Chinese firms: a dynamic capabilities view. Inform Manag 56(6):103135

Sarwar Z, Khan MA, Sarwar A (2021) The strategic management model for covid 19" a race against time": evidence from People’s Republic of China. Gomal Univ J Res 37(3):278–286

Manyika J et al (2011) Big data: the next frontier for innovation, competition 2011, and productivity. Technical report. McKinsey Global Institute

Vial G (2021) Understanding digital transformation: a review and a research agenda. Manag Digit Transform 13–66

Wamba SF et al (2015) How ‘big data’can make big impact: findings from a systematic review and a longitudinal case study. Int J Prod Econ 165:234–246

Parise S (2014) Big data: a revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think. In: Mayer-Schonberger V, Cukier K (eds) Eamon Dolan/Mariner. Taylor & Francis, London, p 272

Ghasemaghaei M, Calic G (2020) Assessing the impact of big data on firm innovation performance: big data is not always better data. J Bus Res 108:147–162

Wahab SN et al (2021) Big data analytics adoption: an empirical study in the Malaysian warehousing sector. Int J Logist Syst Manag 40(1):121–144

Wolfert S et al (2017) Big data in smart farming—a review. Agric Syst 153:69–80

Winig L (2017) A data-driven approach to customer relationships: a case study of Nedbank’s data practices in South Africa. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 58:2

Ghasemaghaei M, Calic G (2019) Can big data improve firm decision quality? The role of data quality and data diagnosticity. Decis Support Syst 120:38–49

Günther WA et al (2017) Debating big data: a literature review on realizing value from big data. J Strateg Inf Syst 26(3):191–209

Marr B (2016) Big data in practice: how 45 successful companies used big data analytics to deliver extraordinary results. Wiley

Wamba SF et al (2017) Big data analytics and firm performance: effects of dynamic capabilities. J Bus Res 70:356–365

Ghasemaghaei M (2019) Are firms ready to use big data analytics to create value? The role of structural and psychological readiness. Enterprise Inform Syst 13(5):650–674

Pham X, Stack M (2018) How data analytics is transforming agriculture. Bus Horiz 61(1):125–133

Sun W, Ding Z, Xu X (2021) A new look at returns of information technology: firms’ diversification to IT service market and firm value. Inf Technol Manag 22(1):13–31

Barua A et al (2004) An empirical investigation of net-enabled business value. MIS Q 28(4):585–620

Barua A, Kriebel CH, Mukhopadhyay T (1995) Information technologies and business value: an analytic and empirical investigation. Inf Syst Res 6(1):3–23

Brynjolfsson E, Hitt LM (2000) Beyond computation: Information technology, organizational transformation and business performance. J Econ Perspect 14(4):23–48

Anand A, Fosso Wamba S, Sharma R (2013) The effects of firm IT capabilities on firm performance: the mediating effects of process improvement

Devaraj S, Kohli R (2003) Performance impacts of information technology: is actual usage the missing link? Manag Sci 49(3):273–289

Irani Z (2002) Information systems evaluation: navigating through the problem domain. Inform Manag 40(1):11–24

Irani Z (2010) Investment evaluation within project management: an information systems perspective. J Oper Res Soc 61(6):917–928

Irani Z, Ghoneim A, Love PE (2006) Evaluating cost taxonomies for information systems management. Eur J Oper Res 173(3):1103–1122

Sharif AM, Irani Z (2006) Exploring fuzzy cognitive mapping for IS evaluation. Eur J Oper Res 173(3):1175–1187

Roach SS (1987) America’s technology dilemma: a profile of the information economy. Morgan Stanley

Solow RM (1987) We’d better watch out. New York Times Book Review, p 36

Strassmann PA (1990) The business value of computers: an executive’s guide. Information Economics Press

Henke N, Libarikian A, Wiseman B (2016) Straight talk about big data. McKinsey Quart 10(1):1–7

Khan Z, Vorley T (2017) Big data text analytics: an enabler of knowledge management. J Knowl Manag

Shamim S et al (2020) Big data analytics capability and decision making performance in emerging market firms: the role of contractual and relational governance mechanisms. Technol Forecast Soc Change 161:120315

Zeng J, Glaister KW (2018) Value creation from big data: looking inside the black box. Strateg Organ 16(2):105–140

McAfee A et al (2012) Big data: the management revolution. Harv Bus Rev 90(10):60–68

Gupta AK, Goyal H (2021) Framework for implementing big data analytics in Indian manufacturing: ISM-MICMAC and fuzzy-AHP approach. Inf Technol Manag 22(3):207–229

Awan U et al (2021) Big data analytics capability and decision-making: the role of data-driven insight on circular economy performance. Technol Forecast Soc Change 168:120766

Ravichandran T (2018) Exploring the relationships between IT competence, innovation capacity and organizational agility. J Strateg Inf Syst 27(1):22–42

Yunis M, Tarhini A, Kassar A (2018) The role of ICT and innovation in enhancing organizational performance: the catalysing effect of corporate entrepreneurship. J Bus Res 88:344–356

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2000) Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg Manag J 21(10–11):1105–1121

Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 18(7):509–533

Zhen J et al (2021) Impact of organizational inertia on organizational agility: the role of IT ambidexterity. Inf Technol Manag 22(1):53–65

Teece DJ (2014) The foundations of enterprise performance: dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Acad Manag Perspect 28(4):328–352

Teece DJ (2018) Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res Policy 47(8):1367–1387

Buzzao G, Rizzi F (2021) On the conceptualization and measurement of dynamic capabilities for sustainability: building theory through a systematic literature review. Bus Strateg Environ 30(1):135–175

Matarazzo M et al (2021) Digital transformation and customer value creation in made in Italy SMEs: a dynamic capabilities perspective. J Bus Res 123:642–656

Siems E, Land A, Seuring S (2021) Dynamic capabilities in sustainable supply chain management: an inter-temporal comparison of the food and automotive industries. Int J Prod Econ 236:108128

Weaven S et al (2021) Surviving an economic downturn: dynamic capabilities of SMEs. J Bus Res 128:109–123

Sheng S, Zhou KZ, Li JJ (2011) The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: evidence from China. J Mark 75(1):1–15

Shu C et al (2012) Managerial ties and firm innovation: is knowledge creation a missing link? J Prod Innov Manag 29(1):125–143

Peng MW, Luo Y (2000) Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: the nature of a micro-macro link. Acad Manag J 43(3):486–501

Sarwar Z et al (2021) An investigation of entrepreneurial SMEs’ network capability and social capital to accomplish innovativeness: a dynamic capability perspective. SAGE Open 11(3):21582440211036090

Hemmert M et al (2016) Building the supplier’s trust: role of institutional forces and buyer firm practices. Int J Prod Econ 180:25–37

Reich BH, Benbasat I (1996) Measuring the linkage between business and information technology objectives. MIS Quart 55–81

Sabherwal R et al (2019) How does strategic alignment affect firm performance? The roles of information technology investment and environmental uncertainty. MIS Q 43(2):453–474

Luftman J, Lyytinen K, Zvi TB (2017) Enhancing the measurement of information technology (IT) business alignment and its influence on company performance. J Inform Technol 32(1):26–46

Pearlson KE, Saunders CS, Galletta DF (2019) Managing and using information systems: a strategic approach. Wiley

Gupta M, George JF (2016) Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Inform Manag 53(8):1049–1064

Mikalef P et al (2020) Exploring the relationship between big data analytics capability and competitive performance: the mediating roles of dynamic and operational capabilities. Inform Manag 57(2):103169

Mikalef P et al (2018) Big data analytics capabilities: a systematic literature review and research agenda. IseB 16(3):547–578

Eisenhardt K, Martin J (2000) Dynamic capability: what are they. Strateg Manag J 21

Teece DJ (2017) Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: standards, complementary assets, and business models in the wireless world. Res Policy (forthcoming)

Shamim S et al (2020) Connecting big data management capabilities with employee ambidexterity in Chinese multinational enterprises through the mediation of big data value creation at the employee level. Int Bus Rev 29(6):101604

Teece DJ (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manag J 28(13):1319–1350

Schuller T, Theisens H (2010) Networks and communities of knowledge

Young J (2012) Personal knowledge capital: the inner and outer path of knowledge creation in a web world. Elsevier

Hazen BT et al (2016) Big data and predictive analytics for supply chain sustainability: a theory-driven research agenda. Comput Ind Eng 101:592–598

Janssen M, van der Voort H, Wahyudi A (2017) Factors influencing big data decision-making quality. J Bus Res 70:338–345

Johnson JS, Friend SB, Lee HS (2017) Big data facilitation, utilization, and monetization: exploring the 3Vs in a new product development process. J Prod Innov Manag 34(5):640–658

Shamim S et al (2021) Big data management capabilities in the hospitality sector: service innovation and customer generated online quality ratings. Comput Hum Behav 121:106777

Akhtar P et al (2019) Big data-savvy teams’ skills, big data-driven actions and business performance. Br J Manag 30(2):252–271

Awan U et al (2021) The role of big data analytics in manufacturing agility and performance: moderation–mediation analysis of organizational creativity and of the involvement of customers as data analysts. Br J Manag

Hargreaves I et al (2018) Effective customer relationship management at atb financial: a case study on industry-academia collaboration in data analytics. Highlighting the importance of big data management and analysis for various applications. Springer, pp 45–59

Vassakis K, Petrakis E, Kopanakis I (2018) Big data analytics: applications, prospects and challenges. Mobile big data. Springer, pp 3–20

Bikakis N, Papastefanatos G, Papaemmanouil O (2019) Big data exploration, visualization and analytics. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Akter S et al (2020) Reshaping competitive advantages with analytics capabilities in service systems. Technol Forecast Soc Change 159:120180