Abstract

In the light of Bandura’s (Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive perspective, Princeton-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1986) social cognitive theory (SCT), we investigated the roles of four different entrepreneurial factors: entrepreneurial qualities (EQ), entrepreneurial knowledge (EK), perceived entrepreneurialism (PE) and entrepreneurial inspiration (EIN), in entrepreneurial intention (EI) formation. Alongside, this paper explored the unique role played by entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator among the list of determinants and EI. The study approached with a sample of 1062 final year engineering student from 15 premier technical institutes in India. The findings show that the effects of EQ, PE, and EIN on EI are partially mediated by entrepreneurial self-efficacy whereas a full mediation between EK and EI, which is consistent with the SCT framework. The implications suggest for improving the EK delivery system, which in turn will make students feel self-efficacious toward being entrepreneurial. The article argued on various pedagogical as well as the policy-related context of business venturing at Indian technical institutes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economists have always advocated for the promotion of entrepreneurship as an all-in-one solution to cure many complex economic problems, which a nation-state could be facing at any time frame, including low rate of growth, high inefficiency, poor innovation, high inflation and massive unemployment. So, the list of top priorities for the policymakers to develop a resilient economy includes invigorating an entrepreneurial culture in the society, where entrepreneurs are admiringly valued. Echoing this vision, scholars abstracted entrepreneurs as role models who synthesize the complexity and uncertainty in any economy to bring about social and economic development through the promotion of growth and sustainability. Thus, historically, entrepreneurship scholars are found to envisage innovative models to capture the young mind’s psyche behind entrepreneurial motivation. Moreover, the process of fostering entrepreneurial behavior is found to be directly linked with EI (Ajzen 1987; Krueger et al. 2000), thus, before interpreting behavior, scholars must take into cognizance the influences of various predictors of EI and how they map into the design.

Through a rigorous literature survey of EI scholarship, one can argue that the previous research in this field often lacks a comprehensive all-in-one approach, where personal and environmental factors are not just considered in isolation, but through an across-the-board measure reflecting a clear theoretical rationale. To conceptualize this research framework, we grouped the list of antecedents into four factors: entrepreneurial qualities (individual characteristics which appeal to pursue an entrepreneurial career), entrepreneurial knowledge (human capital which changes a person’s perception of his or her aptitude about different entrepreneurial aspects), perceived entrepreneurialism (degree to which an individual feels pro or anti-entrepreneurial vibe about his or her surroundings) and entrepreneurial inspiration (internally embedded causes that allure an individual throughout his or her business life). Following by this predisposition, we attempted with an extensive list of feasible antecedents to embrace a 360-degree approach towards EI. Hence, addressing some concerns over entrepreneurship as a fragmented field of study, comprised of numerous sub-categories, resulting in encouraging scholars to compete against one another and making little use of each other’s work (Fiet 2001; Ucbasaran et al. 2001).

Through the first contribution of this study, we will offer a meaningful step forward in understanding the theoretical explanation clarifying the role played by individual-level antecedents as well as situational-level, from a social-cognitive perspective grounded by Bandura (1986). From the social-cognitive theory (SCT) perspective, one can argue that like any other human learnings, the entrepreneurial process leading to EI-behavior development occurs through dynamic and interactive settings between a person, environment, and behavior. Further, SCT summarizes how some psychological attributes help him or her to synthesize pro or anti-entrepreneurial inputs from the surroundings and develop a mental snapshot to ascribe relevant meaning to it. Thus, through a multiple basket approach, we effort to design a fusion-model based on personal-psychological, socio-psychological, and perceived ecological factors related to entrepreneurship. The next contribution will assess the influence of several stable and individual-specific entrepreneurial qualities (proactiveness, risk tolerant, passionate, optimism, achievement-oriented, creativity, and narcissism) together with other relatively flexible factors like entrepreneurial knowledge, perceived entrepreneurialism and entrepreneurial inspiration in a single theoretical model. While extending the SCT framework, this study selects entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator between the list of antecedents and EI. The third and functional level contribution of this study will provide a better understanding of entrepreneurial ethos at the premier technology institutes in India. This will contribute firstly, through the understanding of young engineering students’ entrepreneurial psyche and secondly, by sufficing the existing lacks in designing appropriate entrepreneurial education program. Although, there has been policy level promotion for entrepreneurship programs in Indian universities, primarily through the top end technology and management institutes over the last few decades, doubts about the outcomes of these programs are not incontestable. Additionally, while, the significant number of erstwhile empirical research on entrepreneurship education indicates its effectiveness (Gorman et al. 1997), challenges for the complete academic legitimacy of entrepreneurship as a field of study continues to arise (Kuratko 2005). Therefore, this study will bring some new insights on the topic itself.

On the contextual design, it has been historically documented that engineering graduates are always inclined towards building dynamic and innovative companies compared to graduates from other disciplines, thus, promoting significant economic growth and increase in employment (Roberts 1991). Accordingly, to validated this research, we took the Indian case (a country with more than one billion people, 41% of the population account for less than 20 years of age, the fastest growing large economy, 1.5 million engineering pass-out every year, and one of the dominant players in current world affair), which perfectly suits the investigation set-up. Although the culture of dormitory-venturing (students who decide to spin-out on his or her own start-up ideas while staying in university dormitory) is not much familiar in India, like the USA, however, institutions such as Indian Institute of Technology is taking leads slowly but firmly. Therefore, from the perspective of an emerging nation (India), to sustain its newly gained economic growth deserves carving for creating a pro-entrepreneurial ecosystem to inspire its young engineering graduates towards entrepreneurship. Correspondingly, this study sampled 1062 engineering graduate students pursuing Bachelor of Technology (B. Tech) at esteemed technology institutes like Indian Institute of Technology (IITs are a group of premier technology institutes set up by the Govt. for the first time in 1951), National Institute of Technology (NITs are the second-tier engineering institutes in comparison to IITs, also set up by the Govt. across the country) and private engineering institutes.

Next, the article is organized into five different sections, namely, theoretical background and hypotheses development, research methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. To develop a theoretically sound conceptual model and research hypotheses, we reviewed previous contributions by scholars in the relevant field through “Theoretical background and hypotheses development” section. In the third section, we elaborated details about questionnaire development, its validation, sampling procedures, and statistical methods used in the analysis. Results section comprised of outcomes from structural equations modeling and multi-step regression for mediation to validate the research hypotheses. In the fifth section, we made a thorough discussion of the findings from the results. And finally, we completed the article with a brief conclusion, which contains both theoretical and practical implications along with the limitations and directions for future research.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Social cognition

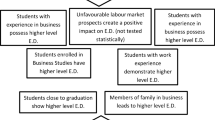

The concepts guiding the theory of social cognition is built on the study of activities like, information processing and human cognition, which motivate individuals to gather information from the surroundings, synthesize and interpret it using his or her emotions and other attributes; and finally, informing the decision-making outcomes for the social world (Bandura 1986; Fiske and Taylor 1991; Robinson and Marino 2015). Applying social cognitive lens on entrepreneurship within the Bandura’s (1986) SCT postulations, one can derive that the whole learning, motivational, and behavioral processes occur through the bidirectional interactions among surrounding environment, individual characteristics, and behavioral outcomes. Also, SCT as a theoretical framework found to be bringing new insights into entrepreneurship research and practice while appreciating both personal and environmental phenomena related to entrepreneurship (Biraglia and Kadile 2017; Camerer and Lovallo 1999; Gartner 1985; Hayward et al. 2006; Linan et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2005). Accordingly, the understanding of entrepreneurial cognitive perspective rests on one’s explanation of individual cognitive processes and its outcomes while determining the individual’s entrepreneurial goals, emotions, and motivations within the existing social context of the situation (Arora et al. 2013). Next, the hypotheses are built on the multi-dimensional relational aspects, and presented through the conceptual research framework (Fig. 1).

Entrepreneurial qualities and entrepreneurial intention

Among the three pillars of SCT, the personal dimension has its major contribution. When one focuses on EI-research through the lens of SCT, various entrepreneurial qualities are found to assert their influence. Several entrepreneurial traits and their impacts on EI have been noted throughout the generations of EI scholar (Biraglia and Kadile 2017; Chen et al. 1998; Crant 1996; Douglas 2013; Espíritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo 2015; Sánchez 2011, 2013; Van Gelderen et al. 2008; Volery et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2005). Although, the list of such entrepreneurial qualities is quite extensive, only few among them received standardized literature support over time. Here, the stated list of entrepreneurial qualities is comprised of proactiveness, risk tolerance, passion, optimism, achievement orientation, creativity, and narcissism.

Proactiveness (Haase and Lautenschläger 2011; Marques et al. 2011; Padilla-Meléndez et al. 2014; Sánchez 2011, 2013) as an entrepreneurial characteristic outlines individual entrepreneur’s anticipation of forthcoming events, changes to be adopted and needs assessment. Therefore, proactiveness finds its close association with innovativeness; as its forward-looking perspective represents the opportunity-seeking attitude of an entrepreneur. Whereas, the risk tolerance (Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Hartog et al. 2010; Kanbur 1982; Rauch and Frese 2007; Sexton and Bowman 1985) as one of the most frequently used entrepreneurial personality traits (Fairlie and Holleran 2012), predispose individuals towards entrepreneurship. Moreover, having a higher level of individual risk tolerance ability results in a more positive attitude towards the precarious nature of venturing. Our third entrepreneurial quality factor i.e., entrepreneurial passion (Baum and Locke 2004; Cardon et al. 2009, 2013; Ma and Tan 2006; McGrath and MacMillan 2000; Smilor 1997) is a very distinct type of intense feelings that creates a whole world of love for a particular task. Passion for venturing can directly be linked with the enthusiasm and strong inclination towards creating something insanely amazing that brings great joy to the entrepreneur himself or herself. While optimism (Owens 2004; Peterson 2000; Scheier and Carver 1985; Solymossy and Hisrich 2000) as a goal-directed mechanism leads individual entrepreneur to persevere continuous efforts in attaining the desirable outcomes. Individuals with a positive and realistic optimism found to be engaged in psychological well-being, higher levels of adaptability, and personal accomplishments hence, are more entrepreneurially intended. The concept of achievement orientation (Hansemark 2003; McClelland 1985, 1987; Miron and McClelland 1979; Phillips and Gully 1997; Smith and Miner 1984; Tajeddini and Mueller 2009), finds its close association with the conventional entrepreneurial wisdom that entrepreneurs must perform and thrive under challenging and competitive environment. Also, they need to consistently improve their performance to overcome obstacles, and not shy away from taking responsibility either for their own success or failure. Thus, having a higher level of achievement orientation could influence both the venture formation intention and performance. The next entrepreneurial quality factor i.e., creativity as an antecedent of EI emerges from the man and nature interaction that leads to opportunity search and new firm formation. Here, creativity (Amabile 1996; Ko and Butler 2007; Lee et al. 2004; McMullan and Kenworthy 2008; Ward 2004; Zampetakis et al. 2011) refers to the human cognitive capability for both expansion and combination of disconnected pieces of information from the surrounding environment to generate novel ideas. The last entrepreneurial quality factor, narcissism (DeNisi 2015; Grijalva et al. 2015; Mathieu and St-Jean 2013; Miller 2015) exerts its influence on self-esteem by taking an inflated view of other entrepreneurial characteristics such as risk-taking, locus of control and self-efficacy etc. While healthy narcissism may assist individuals to stay focused on the success and accomplishment without the fear of failure, the destructive narcissism turns the intense desire to acquire power and the positions of prestige through wealth accumulation into hubris (Kernberg 1979; Lubit 2002). In summary, we hypothesize that

H1

Entrepreneurial qualities will be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurial knowledge (Corbett 2007; Dohse and Walter 2012; Haase and Lautenschläger 2011; Liñán et al. 2011; Miralles et al. 2016) influences EI through the individual level cognitive abilities that allow an entrepreneur to value and exploit the information necessary for entrepreneurial opportunity search. In this study, we considered the existence of entrepreneurial knowledge in two shapes: (1) tacit knowledge, (2) explicit knowledge. The tacit entrepreneurial knowledge is the unique kind of human capital that can only be sourced from role models exist within the family, relatives and the close friends or to some extent individuals’ region of residence. The tacit form of entrepreneurial knowledge gets accumulated over a longer period of time and hardly has its real-time appearance in a codified form. Previous researchers (Brüderl and Preisendörfer 1998; Busenitz and Lau 1996; Mueller 2006; Shane 2003) further confirmed, individual entrepreneur’s access to the superior source of tacit knowledge makes an ocean of difference in formulating the right decision while selecting the business strategy. Other than personal contacts as a source of tacit entrepreneurial knowledge, students’ campus-life plays an important role in sourcing both the tacit as well as well as explicit sort of knowledge. Observing venture formation, its growth, success as well as the failure of the seniors in the campus, teaches a lot about the required entrepreneurial skills, traits essential for venturing. Thus, the existence of an entrepreneurial culture inside the campus creates pro-entrepreneurial dynamics, which could stimulate students either to consider entrepreneurship as a substitute career option or sometimes in direct venturing. The explicit form of entrepreneurial knowledge is codified, and it is directly deliverable by teachers and experts. This type of knowledge primarily helps the beginners with new customs and peripheries about entrepreneurship. It also can excite a novice with the glory and magnificence of successful entrepreneurship. Additionally, when academic knowledge is accompanied by real-time project-oriented entrepreneurship programs, it helps students with new technology, new markets (Shane 2000), understanding competitive analysis, strategy for growth and financing (Hindle 2007) and knowledge for being creative (Fiet 2001; McMullan and Long 1987). In turn, the existence of typical entrepreneurial knowledge among engineering students should have a positive impact on their EI. Thus, our second hypothesis follows

H2

Entrepreneurial knowledge will be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Perceived entrepreneurialism and entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurialism (Charney and Libecap 2003; Hannon 2005; Lumpkin 2007; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005) as a planned and intentional behavior describes the degrees of human perception created by the interaction between existing regulatory, normative, and cognitive framework (Kostova 1997), towards his or her culture, region or at large nation’s adaptability for entrepreneurship. These three dimensions (regulatory, normative, and cognitive) exert their influence on defining pro or anti-entrepreneurial culture in a society through the formal and informal institutions. Like any other intentions, EI is immensely impacted by the axiomatic beliefs about the social, political, legal and economic structure of a country. So, the existence of pro-entrepreneurial regulatory norms, which are mostly codified source of laws, regulations, and government policies designed to support novice entrepreneurs by reducing the personal risk of failure, may facilitate young students towards entrepreneurship (Busenitz et al. 2000). Flowing Baumol’s (1990) comment on this, we can rephrase that the existence of a pro or anti-entrepreneurial ecosystem in a society may breed a sense of productive, unproductive, or even destructive entrepreneurial ethos that undeniably impacts EI. The normative dimension could exert influence on society’s approach towards entrepreneurship through the value system, which shapes individual’s perception about his or her country men’s degree of appreciation towards fostering innovation by entrepreneurship. Likewise, cognitive dimension measures its influence over a society through the level of institutionalized skill-set and knowledge owned by the people of the society to establish new ventures. Hence, the existence of a widely dispersed shared-knowledge about cheap labor, new technology, and venture partner bring cognitive legitimacy of venturing into the minds of novice entrepreneur. This rationale is echoed through our third hypothesis

H3

Perceived entrepreneurialism will be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial inspiration and entrepreneurial intention

Following Edison’s quote, “invention is all about 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration”, at the first sight, we might look little eager to denounce the importance of the inspirational content of entrepreneurship. Perhaps what most people’s derivations from this line miss-out are that individuals get emotionally motivated for 99% perspiration, only when they are inspired by heart and soul. Inspiration (Moriano et al. 2014; Souitaris et al. 2007) through articulating a compelling vision of the future for the prospective entrepreneurs demonstrates optimism and enthusiasm. Whilst recognition (Carter et al. 2003; Lee and Wong 2004; Shane 1992; Suzuki et al. 2002), clearly has an emotional and inspirational component, which any entrepreneur will aspire to achieve throughout his or her lifetime. The social recognition refers to individual’s aspiration to attain prestige, titles, family and community name, acknowledgment by the peer group. The other intrinsic goal that would entice any prospective entrepreneurs is the fascination for self-regulation or independence (BarNir et al. 2011; Carter et al. 2003; Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Hessels et al. 2008; Kautonen et al. 2013), which only a career in entrepreneurship can offer him or her. Additionally, self-regulation as a career anchor provokes craftsmanship orientation (Katz 1994) in entrepreneurship, which works as a vehicle for individualism, self-style work pace or even need for escape, from organizational rules. Our third inspirational factor self-realization (Kolvereid 1996; Korunka et al. 2003; Renko et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2014), settles down at the top of the Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs triangle. And it may look promiscuous initially, considering the observation would be derived from young students’ opinions about such a higher-level human goal of emancipation (self-realization) to have any influence on EI. But the debate might source new insights when we see it through Steve’s portrayal of self (Isaacson 2011):

I hope that throughout my life I’ll sort of have the thread of my life and the thread of Apple weave in and out of each other, like a tapestry……If you want to live your life in a creative way, as an artist, you have to not look back too much (Isaacson, 2011, p. 257).

Throughout Stave’s biography by Isaacson (2011), one can balance, it’s not only the materialistic aspiration but a strong self-defining spiritual desire has driven his entrepreneurial ambition. But it’s not only intrinsic goals that inspire prospective entrepreneurs, extrinsic outcomes like financial success (Carter et al. 2003; Renko et al. 2012; Saeed et al. 2015; Schumpeter 2013; Shepherd and DeTienne 2005) lured generations of entrepreneurs in the world of creative destruction. We can further explain this phenomenon with the help of expectancy theory (Vroom 1964), where individual’s intention to perform an entrepreneurial task is highly motivated by the promise of potential economic gain. Hence, the authors hypothesize

H4

Entrepreneurial Inspiration will be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial intention, and the mediation

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Barnir and Watson 2011; Biraglia and Kadile 2017; Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Carr and Sequeira 2007; Prabhu et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2005) as a distinct class of motivational construct often exerts its influence on EI by playing a dual role. Erstwhile scholars have expended the importance of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship research both by examining its role as a direct independent variable as well as a mediator against EI. In SCT, Bandura (1986) specifies four discrete processes through which individual’s sense of self-efficacy can be influenced. They are namely, enactive mastery, role modeling and vicarious experience, social persuasion, and judgments of one’s own physiological states.

Enactive mastery in a field like entrepreneurship can only be fostered when individual student’s personal entrepreneurial qualities are effectively responding to the stimulus. Whereas, a student’s learnings from role modeling and vicarious experience happen through both of his personal as well as institutional environment. On the other hand, social persuasion factor of self-efficacy can be enacted through perceived entrepreneurialism. Accordingly, a pro or anti-entrepreneurial sense in the surroundings impacts one’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Moreover, individual’s physiological states like arousal and anxiety may find its intrinsic associations with inspirational factors reflected in our study. As a whole, self-efficacy consistently demonstrated its explanatory power for individuals’ pursuance at a given task and their persistence with the continuous effort until they succeed in the pre-determined goals (Bandura 1997). In general, we define a person as entrepreneurial or non-entrepreneurial by various tasks he or she executes throughout the career. For example, search for business opportunity, obtaining required resources to exploit the opportunity, presenting a creative solution, offer that solution often below market price and continuous innovation to avoid competition thus, having satisfied customers. All these tasks require specific mastery of various entrepreneurial skills and abilities. Moreover, the SCT framework suggests that the context-specific nature of self-efficacy made it exceptionally functional for entrepreneurship, as the instructor can customize it as per particular needs, resulting in the additional predictive level of outcomes. Likewise, this conventional relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and EI has been examined by generations of entrepreneurship scholars (Biraglia and Kadile 2017; Chen et al. 1998; Kickul and D’Intino 2005; Liñán et al. 2011; Segal et al. 2002). Thus, our proposition here

H6

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy will be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Through the conceptual model, we proposed the dual role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, where along with the direct effect we also contemplated entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator between the list of independent variables and EI. We hypothesized that, even though all the independent variables as discussed above have their own individual impact on EI, but these direct relationships may also be influenced (positively or negatively) by the intervening role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Through the SCT framework, we argued that when self-efficacy belief factors (enactive mastery, role modeling and vicarious experience, social persuasion, and judgments of one’s own physiological states) are influenced by the listed independent variables, then at different levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, the direct effect on EI may or may not exist. Thus, to get a better insight into the equations, we endorsed the third variable (entrepreneurial self-efficacy) as our mediator in the model. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses

H5a

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the effects of entrepreneurial qualities on entrepreneurial intention.

H5b

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the effect of entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intention.

H5c

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the effect of perceived entrepreneurialism on entrepreneurial intention.

H5d

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the effect of entrepreneurial inspiration on entrepreneurial intention.

Research methodology

Sample, scale and data description

To conduct this research, we approached five old IITs (selected from a list of 23 institutions functioning under the brand-IIT), five NITs (randomly selected from a list of 31 institutions functioning under the brand-NIT) and for private engineering colleges, we randomly selected five top-ranked private engineering colleges from a list made by MHRD (Ministry of Human Resource Development), India (Data Source: National Institutional Ranking Framework). It took 6 months to complete the whole process of data collection starting from June-2016 to November-2016. The stratified purposive sampling method was used, where stratification is done on the basis of preordained wisdom, resulting in the true representation of the population. The first phase of data collection was stretched from the month of June to September when we reached IITs and NITs. In the second phase (October to November), we approached private engineering colleges. All of these selected IITs had full-fledged incubation center established in the campus: Indian Institutes of Technology in New Delhi, Mumbai, Madras, Kharagpur, and Kanpur. Also, our selected list of NITs and private engineering colleges had their self-styled entrepreneurship promotion center to accommodate new innovation.

The presence of various types of biases throughout the whole process of data collection often affect the outcomes of the research. Thus, to reduce the first of its kind i.e., geographical bias, we selected engineering and technology institutes located in global cities like Mumbai, Bangalore, and Delhi, while others are selected from the provincial capitals like Madras and Kolkata. To reduce the second type of bias i.e., selection bias, we randomly choose engineering students who were in their final year of the four-year B. Tech. Further, we approached only to those students who enrolled themselves in entrepreneurship-subject as a full-fledged minor B. Tech. This approach helped us to reach those students who find little more attraction towards entrepreneurship while pursuing engineering compared to their batch-mates. The other sort of bias is non-response bias (which results from the denial of response or significant difference between the respondents and non-respondents among target population; Forza 2002). We eliminated such concern by increased response-rate and the level of response (Lindell and Whitney 2001). The final in the list comes as common method variance, we used Harmon’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986), where we ran an exploratory factor analysis to check whether a single-factor accounts for major covariance. Here, our results showed multiple factors exist with eigenvalues greater than one. Furthermore, loadings were consistent and the single factor structure was unable to explain a significant covariance. Hence, the common method bias was found to be trivial.

We divided the entire questionnaire into two parts. The first part was demography related, whereas the second part covered items representing both psychology and environment-related items. Except for demographic questions, in all other cases, we attempted with a multi-item Likert scale which was ranged from 1 (“lowest measure”) to 5 (“highest measure”). As we used, already developed set of questionnaires hence, validity and reliability of the scale was not a concern. For additional finesse, a small pilot testing among 42 engineering graduate students was completed to recheck the validity and reliability, and the scale came out clean. The process of reverse coding among items was implemented to increase the validity of the questionnaire (Nunnally 1978; Schriesheim and Eisenbach 1995). Finally, a total of 2000 questionnaires was administered, among which 1215 responses were returned after repeated follow-up. In general, the response rate was relatively on the higher-side (approximately 60%), compared to other studies.

Consecutively, to ensure the absence of any outliers and missing values, we followed up with techniques like Cook’s Distance and regression imputation. Successively, our clean and ready to use for further analysis sample was reduced to 1062 (approximately 53%). Among those 1062 individuals, we found 817 (76.9%) as male students whereas, the rest 245 (23.1%) as female. All of our respondents were unmarried, 41.05% respondents were below 21 years of age whereas, 58.95% ranged between 21 and 25. The social-class distribution was: 58.66% general, 24.38% OBC, 12.43% SC and 04.52% ST. Within the sample, we found 63.94% students’ parents were employed either in government sector or in national/international public/private firms, whereas 36.06% students’ parents were self-employed. As the data were obtained from three different types of institutions, so finding consistency through equal representation was utmost critical. Henceforth, we acknowledged 38.99% valid response from IITs, 27.97% from NITs and 33.05% form private engineering colleges.

Study measures

Table 1 lists all the questionnaire items. The detail description of each item is mentioned and respective source of adoption is cited below.

Entrepreneurial qualities

We considered seven human qualities related to entrepreneurship. They are namely, proactiveness, risk tolerance, passion, optimism, achievement orientation, creativity, and narcissism. An extensive literature survey was done to obtain standard questionnaire for the above-mentioned sub-constructs. The adopted items are as follows: (1) proactiveness, 3-item scale—Seibert et al. (1999), (2) risk tolerance, 2-item scale—Fairlie and Holleran (2012), (3) passion, 3-item scale—Cardon et al. (2013), (4) optimism, 4-item scale—Scheier and Carver (1985), (5) achievement orientation, 3-item scale—Lee and Tsang (2001), (6) creativity, 4-item scale—Zhou and George (2001) and (7) narcissism, 4-item scale—Ames et al. (2006). Here, entrepreneurial qualities as a full-construct, registered Cronbach’s α value of 0.82, which is above the satisfactory level of 0.70 (Nunally 1978).

Entrepreneurial knowledge

To measure entrepreneurial knowledge, we adopted a 5-item scale. The scale is composed of 3-items from Dohse and Walter (2012) and 2-items from Liñán et al. (2011). The items taken from Dohse and Walter (2012) represent a set of individual-level queries, comprised of his/her understanding of the entrepreneurial knowledge context existing in the surroundings and its usability. The two items from Liñán et al. (2011), insisted to know about the individual level knowledge context, which can be obtained by attending planned entrepreneurship education. Although, the five questions had two different origins, while implementing PCA with varimax rotation, we witnessed that a single factor featuring all the items. We also documented Cronbach’s α value of 0.79.

Perceived entrepreneurialism

Adopting a 5-item scale from Busenitz et al. (2000), we measured perceived entrepreneurialism. Items listed under this heading include: “Indian-government organizations assist individuals with starting their own businesses” and “Entrepreneurs are admired in India”. While pursuing factor analysis we detected that all the five items (eigenvalues greater than 1) loaded were in a single factor. Moreover, reliability was not a concern for this scale, as we obtained relatively high α value of 0.84, well above the minimum acceptable earmark.

Entrepreneurial inspiration

Four well-studied entrepreneurial spirit aspects (recognition, self-regulation, financial success and self-realization) were considered in this research. For each of the four sub-constructs, sources of adaptation are as follows: (1) recognition, 3-item scale—Carter et al. (2003), (2) self-regulation, 3-item scale—Kolvereid, (1996), (3) financial success, 4-item scale—Carter et al. (2003) and (4) self-realization, 3-item scale—Kolvereid, (1996). The reliability concern of the scale was nonexistent at Cronbach’s α value of 0.71.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy

While designing self-efficacy scale, we approached Wilson et al. (2007), who created an entrepreneurial task-specific measurement. Respondents were requested to answer with their level of adeptness while performing an itemized task like, “Managing money”, “Being a leader” and “Making decisions”. Although, the scale was previously validated by the authors themselves, for further assurance, we let it pass through all statistical yardsticks and successively attained reasonable measures.

Entrepreneurial intention

For entrepreneurial intention, we adopted 5-item scale from the author, Liñán and Chen (2009). The scale has been one of the highly regarded and frequently used EI measures. Examples of items listed are, “I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur”, “My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur” and “I am determined to create a firm in the future” and so on. The scale achieved all the pre-determined benchmarks to consider it a reliable and valid measure. The Cronbach’s α value was recorded at 0.87.

Control variables

We considered four variables of interest as controls, they are namely, age, caste, institution type and parent occupation. For age, we operationalized two ordinal categories and used binary 0 and 1. Age below 21, was coded as “0” whereas, for 21–25, we used “1”. The second control variable is caste (in India, the caste system is the historical division in the society on the basis of permitted profession predominantly among Hindus) plays a major role in the selection of preferred profession. Currently, in India, there are four different tiers of the society (unlike earlier class system: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras) according to the social status, and they are: General—people in the higher echelon of the society, OBC—people in the middle band, SC—people in the lower order and ST—people in the extremely lower stratum of the society. To include this control variable in the research, we coded them as: “0” for general, “1” for OBC, “2” for SC and “3” for ST. The third control variable is the type of institutions. Students from IITs were coded as “0”, from NITs as “1” and from private engineering colleges as “2”. Next, individual’s family background leaves a strong impact on future career preferences, while remaining the most effective source of tacit knowledge. Hence, reflecting upon the importance of the kind of family a student belongs to, we coded parent’s occupation: salaried employee as “0” and self-employed as “1”.

Data analysis

This study used AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structure) version 22 while implementing SEM, which applies a covariance-based structure modeling technique. SEM application is mainly based on few progressive appeals, which follows: (1) the rigor of analysis comprises a number of foremost statistical procedures into it, through an integrative approach; (2) it runs a measurement model that takes reliability concern into account thus, remains precise and unambiguous on the supposition of hypotheses; (3) the multi-measure approach can easily take care the veracity of both cross-sectional or longitudinal data set. While implementing SEM, the normality check of the data is highly recommended to increase statistical inference (Baumgartner and Homburg 1996; Shook et al. 2004). Here, Mardia’s test is considered as a recommended one to check the normality concern. With the test statistic of 14.36, the critical ratio was measured at 1.76 (lower than the limit recommendation of 1.96). This deduction further confirmed that the data-set is normally distributed. Next, for SEM application, we followed Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988), two-step approaches: (1) validity and reliability of the conceptual model was tested, (2) the model fitness, validation of the proposed hypotheses was done by constructing an appropriate structural model. Additionally, to corroborate the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator, this study followed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommendations.

Henceforward, a series of regression was run to test the mediation hypothesis (H5). We included all four control variables (i.e. age, caste, institution type and parent’s occupation) in each of the 15 models. Up to Model 5, we regressed the dependent variable i.e., entrepreneurial self-efficacy against both independent and control variables. From Model 6 onwards, EI was operated as the dependent variable. We regressed it sequentially, against controls, independent variables and finally taking all three together: controls, independent variables and the mediator (entrepreneurial self-efficacy).

Results

Measurement and structural model

Before proceeding with confirmatory factor analysis any research should address the validity of construct-level assessment i.e., how perfectly both the operational and conceptual definitions complement each other. In this study, we considered to take notice of different types of validity and they are namely, construct and content validity, convergent validity, and divergent validity. Here, either we fully adopted significant part of the scale from the existing literature or slightly re-specified according to the topic of interest. Henceforth, for most cases, the scale’s construct validity was previously ascertained by the source researchers. On the context of content validity, especially the re-specified items need proper scale validation because any particular construct should represent its underlying theories. Thus, to minimize concerns regarding content validity of the scale, we consulted professionals with domain level expertise in psychology and entrepreneurship. The correlations, means, standard deviations and SQRT of AVE are illustrated synchronously through Table 2. Multicollinearity as a major issue often impacts research findings and could significantly change the outcomes. Here, none of the correlations among the factors of interest was reported above 0.70 (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Hair et al. 2010; Spicer 2005; Vogt 2007), thus no such apparent issues. SQRT of the AVEs (diagonal, bold and italicized) were found to be greater than the respective inter-construct correlations hence, less concern about discriminant validity. Table 3 presents Cronbach’s α measure, variance inflation factor (VIF), composite reliabilities (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). AVE is also a good measure of convergent validity when it scores above 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Here, it ranges between 0.52 and 0.61, thus, no such concern for convergent validity. Additionally, construct reliability measures were scored lowest at 0.85 for entrepreneurial knowledge and highest at 0.95 for entrepreneurial qualities, thus, suffice the minimum score of 0.80 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Also, the Cronbach’s α measures were at acceptable level. Hence, no reliability issues with the constructs and their dimensions. Adding to the Table 2 deductions, VIF as a pointer, often is considered to be an intuitive and reasonable yardstick for measuring multicollinearity. An ideal measure should be scored less than 3.3 (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw 2006; Roldán and Sánchez-Franco 2012). In this research, we detected VIF measures were oscillating in-between 1.78 and 2.41.

The measurement model estimations from the initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), indicate an adequate model fit with the following indices: χ2 = 384.231, χ2/df = 1.670, GFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.931, CFI = 0.938, IFI = 0.952, RMSEA = 0.047. Two relatively low factor loadings (< 0.6) for the individual items (CR3 and OP4), advocated for their removal from further analysis. A second CFA on the newly modified data set solved this particular issue. Moreover, this time we attained a better model fit with the following indices: χ2 = 271.472, χ2/df = 1.516, GFI = 0.932, TLI = 0.957, CFI = 0.961, IFI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.041. With this positivity from CFA, regarding reliability and validity of the proposed model, we go for the structural model to evaluate the hypothesized relationships. The initial statistics for the fit indices were least satisfactory, thus re-specification of the proposed framework was anticipated. After a thorough inspection of modification indices, post re-specification we accomplished a better model fit. The latest and superior goodness-of-fit indices are as follows: χ2 = 331.715, χ2/df = 1.692, GFI = 0.928, TLI = 0.934, CFI = 0.940, IFI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.048. Furthermore, the fit indices for mediated structural model are reported at: χ2 = 261.421, χ2/df = 1.546, GFI = 0.936, TLI = 0.940, CFI = 0.942, IFI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.039.

Hypothesis testing

Table 4 represents the results of hypothesis testing. The structural model confirmed that only institution type and parent occupation were significantly impacting the dependent variable (EI) and the mediator (ESE). The effects of institution type on both ESE and EI are as follows: β (Institution Type→ESE) = 0.196, t = 3.08, p = <0.05; β (Institution Type→EI) = 0.211, t = 2.98, p = <0.05. This interprets that students differ in their level of ESE and EI when we change the type of institution. Similarly, parent occupation was found to be significantly impacting individual’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy as well as career preference. The relationship statistics (β (Parent Occupation→ESE) = 0.242, t = 3.54, p = < 0.01; β (Parent Occupation→EI) = 0.193, t = 3.80, p = < 0.05) connotes that the kind of family a student belongs to, deeply shapes his or her business efficacy and also the intention to pursue entrepreneurial vocation. With these inferences drawn from the control variables, this research approached with further insightful investigations of other study variables (Rubin 2012).

For other direct relationships: the influence of entrepreneurial qualities on EI was found to be very strong and positively significant (β (Entrepreneurial Qualities→EI) = 0.421, t = 7.24, p = <0.01); the impact of entrepreneurial knowledge on EI was positive and significant too (β (Entrepreneurial Knowledge→EI) = 0.359, t = 6.65, p = < 0.001). The direct association between perceived entrepreneurialism and EI although was comparatively moderate, it reports positive and significant (β (Perceived Entrepreneurialism→EI) = 0.211, t = 3.42, p = < 0.05). Whereas, entrepreneurial inspiration’s influence on EI (β (Entrepreneurial Inspiration→EI) = 0.347, t = 3.68, p = <0.01) was reported positively significant. Lastly, the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and EI follows as: β (Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy→EI) = 0.378, t = 3.95, p = <0.01. Through summarizing the above-mentioned statistical outcomes, we found supports for the hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4, and H6.

Mediation analysis

To validate the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator between the list of independent variables and the dependent variable, we endeavored with the Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach. While adhering to this procedure, one needs to follow four basic assumptions: (1) independent variable must exert influence on the dependent variable, (2) independent variable must exert influence on mediator variable, (3) mediator variable must exert influence on the dependent variable, and finally (4) mediator must reduce the effect of independent variable on the dependent variable. Here, two derivations can be obtained from the 4th postulation: (1) full mediation and (2) partial mediation. A full mediation occurs only if the inclusion of mediator in the analysis decreases the effect of independent variable on dependent variable to non-significance, otherwise it’s a partial mediation.

Table 5 illustrates the series of regression analysis that were executed to draw conclusions about ESE’s role. Model 1 and Model 6 are the base models, where we regressed ESE and EI against control variables. From Model 2 to Model 5, we presented the list of antecedents’ effects on ESE. Model 2 exhibits the effects of each of the seven entrepreneurial quality factors on ESE. All the entrepreneurial quality factors were found to be significant except optimism and creativity. Risk tolerance was significant at p < 0.01 whereas, the rest four were at p < 0.05. The effects of entrepreneurial knowledge and perceived entrepreneurialism on ESE were β = 0.288, p = < 0.01 and β = 0.183, p = <0.05 respectively. Model 5 confirms that three of the four entrepreneurial inspiration factors were significant. The explanatory power of Model 2 to Model 5, were reported at 0.342, 0.294, 0.328 and 0.380% respectively, against the Model 1 (R2 = 0.146). Model 6 to Model 10, captures the effects of control variables as well as four predictors on EI. Three of the entrepreneurial quality factors were found significant at p < 0.01, another three at p < 0.05, and creativity was the only item found non-significant. Entrepreneurial knowledge and perceived entrepreneurialism had positive and significant effects on EI. In Model 10, we regressed entrepreneurial inspiration against EI and the results are significant at: recognition (p < 0.05), self-regulation (p < 0.001) financial success (p > 0.05) and self-realization (p < 0.01). Model 11 shows that the effect of ESE on EI was significantly positive at p < 0.01. The R2 value was registered at 0.151, 0.372, 0.238, 0.341 and 0.369 for Model 6 to 10 respectively. Thus, in summary, we could argue that the first three conditions proposed by Baron and Kenny are supposedly met.

Model 12 to Model 15, we included ESE along with other predictors to assess the mediating effect. Model 12 shows that ESE as a mediator diminished the effects of entrepreneurial qualities as a construct. Further investigation reveals that the effects of three entrepreneurial quality factors namely, proactiveness, risk tolerance, and optimism were reduced to non-significance. Whereas, the effects of rest three factors were contracted but still found significant. Thus, a moderate support for H5a. Here, ESE fully mediated the effects of proactiveness, risk tolerance, and optimism, but partially mediated the effects of passion, achievement orientation, and narcissism. For H5b, the decision is obvious, the intervention of ESE in Model 13 reduced the effect of entrepreneurial knowledge to non-significance, thus, the full mediation. Next, Model 14 shows that although the effect of perceived entrepreneurialism was decreased by the intervention of ESE, continues to be significant. Hence, confirmed a moderate support for H5c. Finally, Model 15 exhibits the β values of four entrepreneurial inspiration factors: recognition, self-regulation, financial success and self-realization. We witnessed that mediating variable ESE, diminished the effect of self-realization to non-significance, whereas the effects of recognition and self-regulation, although reduced, stays significant. Accordingly, mixed support for H5d.

Discussion

Followed by the steady rise in the number of scholarly publications in the field of entrepreneurship to enquire into the chemistry behind entrepreneurial persuasion among youths, generations of EI scientists are religiously exploring new dimensions. In line with Bandura’s theory of SCT (1986), this study explores the interrelated and reciprocal relationships that exist between the three grounded constructs: environmental, personal and behavioral elements. Throughout this section, our discussion is focused to extrapolate the combined effects of potential list of predictors of entrepreneurial intention under the Bandura’s SCT framework (Fig. 2).

With positive main-effect relationships, findings from the study support the idea that various entrepreneurial qualities are most likely going to ignite an individual to aspire towards owning his or her own future business. Through a comprehensive analysis, this study reveals much complex explanation about the nature of the associations that exist between a list of entrepreneurial qualities and entrepreneurial intention (Table 5). Findings also show that entrepreneurial knowledge has a positive relationship with EI. Accordingly, it illustrates that higher an individual student is equipped with proper entrepreneurial knowledge, greater the chances for him or her to be entrepreneurially intended. Although this study has not considered the multi-level entrepreneurial knowledge context, here, composing individual-level tacit knowledge with institution-level explicit knowledge, we added significant new insights. The next antecedent, perceived entrepreneurialism measures an individual student’s perception of surrounding entrepreneurial environment. Applying symbolic interactionist lens, the finding from the study further agrees that being from a pro-entrepreneurial stimuli-rich environment (i.e., presence of active venture communities, effectualization of great business ideas), when gets complemented by individual student’s personal appreciation for entrepreneurship, we may see a rise in the intention level for participating in various entrepreneurial activities. Moreover, the findings suggest that any individual pursues entrepreneurial career or at least intend to do so in the face of insurmountable obstacles, not only due to the predictable personal characteristics or environmental concerns but also, he or she is found to be highly inspired by entrepreneurship purposefully.

A well-surveyed entrepreneurial intention literature validates the critical role entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a cognitive factor plays in predicting EI (Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Byabashaija and Katono 2011; Carr and Sequeira 2007; Krueger et al. 2000; Linan 2008; Zhao et al. 2005). Through multi-context research settings erstwhile scholars established the veracity of entrepreneurial self-efficacy’s role in EI-research by using it as direct antecedent of EI as well as mediator between varied list of predictor variables and EI. Here, this study introduces ESE as a mediator between four entrepreneurial factors (entrepreneurial qualities, entrepreneurial knowledge, perceived entrepreneurialism, entrepreneurial inspiration) and EI. The insertion of ESE at the research model’s center stage follows intrinsic mechanism of SCT framework, where ESE through one’s self-belief takes part not just in influencing the efficacy for a task, but helps in setting means to understand the behavioral aspect of the very task. The regression analysis results through Table 5 illustrates that the direct association between three sub-constructs: passion, achievement orientation, narcissism; and the dependent variable (EI) remain significant even after considering the mediational aspect of ESE. This further can be extended, as for some personality traits, the intensity in impacting EI remain unchanged in the presence of ESE. For, hypothesis 5b, which measures the mediating effect of ESE in the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and EI, obtained full support. The direct effect of entrepreneurial knowledge on EI was reduced to non-significance when we introduced ESE in the analysis. This full mediational role of ESE validates the assumption that it’s not just the entrepreneurial knowledge itself, but the self-belief in being capable of implementing that knowledge, outlines EI formation mechanism.

For perceived entrepreneurialism, result (Model 14) shows positive as well as statistically significant direct impact when we insert ESE into the analysis, but the value got reduced from 0.216 (p < 0.05) to 0.107 (p < 0.05). Therefore, indicates that the existing strong direct relationship between perceived entrepreneurialism and EI is more impactful when compared to mediational treatment. Table 4 SEM results quite emphatically exhibits a strong and positively significant relationship between entrepreneurial inspiration and EI. It further infers that more an engineering student feels inspired by the outcomes of a successful venturing, higher the chances he or she nurtures intention to begin with a startup firm in the near future. Next, when we mediated this relationship through ESE, support for partial mediation was found. Model 15 in Table 5, shows that even after introducing ESE into analysis, the impacts of recognition, and self-regulation remain positive and significant. Moreover, accommodating several personal and environmental concerns as controls into the model: age, caste, institution type and parent occupation, stability and robustness aspect of the model is founded without much sensitivity in model dynamics. Additionally, when the proposed theoretical model was tested with the study-sample, it demonstrates validity by attaining required norms and subsequently, comes up with a predictive power of 36% (Adjusted R2 = .367). Whereas, the mediated model shows a better model fit as well as superior explanatory power (Adjusted R2 = .427) in comparison to the proposed theoretical model. With this 6% increase of predictive power (adjusted R2), the mediated model is supposed to be critical for theory-driven post hoc explanations regarding venture creation.

In a nutshell, the findings from this study suggest several new paths to track EI formation among engineering students. Unlike most of the erstwhile research on EI, where run-of-the-mill graduates from all sorts of disciplines are bundled-up together to explore the impacts of various predictors of EI, this study remains focused and subtle about the selection of sample and research goals to achieve. Succeeding with Robert’s (1991) remark on engineering graduates about their ability to build more dynamic and innovative companies compared to general graduates, this study takes an exclusive view for this specific segment of graduates from the perspective of the world’s fastest-growing large economy. Finally, this article through a comprehensive approach, efforts to instrumentalize a multi-window system where we not only mirrored the person-specific views of EI but also echoed the role of context in entrepreneurship.

Conclusion

Implications of the study

Through the analysis of the dataset, this study offers few significant contributions. They can be categorized as (a) theoretical implications and (b) practical implications. The first theoretical contribution for the broader entrepreneurship research will be in integrating the impacts of such an elaborated list of entrepreneurial antecedents in one single framework. With the motivation to explain the roles of seven entrepreneurial personality aspects in predicting EI, this study considers the first individual-level factor i.e., entrepreneurial qualities. Except for few insignificances, most of the sub-constructs representing entrepreneurial qualities remain robust throughout the analysis. Next, the finding also confirms that individual-level entrepreneurial knowledge is active in exerting its influences on EI. Moreover, this influence can be dispensed more purposefully when we implement the entrepreneurial self-efficacy as boundary condition. Whereas, the presence of direct association between entrepreneurialism and EI validates the importance of pro-entrepreneurial ecosystem’s existence. To complete the integrated research framework of EI, this study includes entrepreneurial inspiration as the fourth factor in the analysis. Because only when a student becomes aware of the promising outcomes of his or her entrepreneurial effort, he or she may feel inspired to become an entrepreneur and subsequently, develops EI. Although, entrepreneurial self-efficacy’s role as a mediator in the equation is partially attained, the research findings advance our understanding of both intrinsic and catalytic characteristics of self-efficacy in EI development. Accepting the need for further qualification in addition to those mentioned above, in general, this paper offers clues to get new leeways in designing EI formation mechanism through the SCT framework.

In the context of practical implications, the outcomes of this study present some exciting new insights. The findings can be linked through key mechanism while planning for major public policy strategies to overhaul the existing academically oriented campus culture. Such efforts will bring vibrant pro-entrepreneurial ethos across the campuses of premier technology institutes in India. Through orchestrating such policy framework, the government and other public policymakers at large will be able to make themselves aware of students’ psychology and state of mind towards entrepreneurship as well as required adjustments for entrepreneurial ecosystem per se. Further, by designing course-specific academic or semi-academic assignments, various stakeholders in higher education will be able to meet diverse participants’ needs. Also, taking insights from the analysis, institutes can develop self-assessment tools for its graduate students that will help them to assess the inherent entrepreneurial qualities. Considering the Indian economy’s transition phase, this study may have far-reaching implications, for a country where 80% of its youth population (16–17 y) wants to pursue engineering in comparison with UK (20%) and USA (30%) respectively (Data Source: Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering Report). Accordingly, even if a reasonable portion of those youths can be mainstreamed towards entrepreneurship, we can see a magnificent growth across diverse activities in India’s entrepreneurial sphere. All these suggestions will materialize only when a sizeable number of premier technology institutes (e.g., IITs) in India take entrepreneurship promotion as an institution-level initiative, and implement various training programs, start-up building mechanisms and other forms of vocational learnings. Finally, this study could be an article of interest among several stakeholders like students, EI researchers, educationists, public policymakers and government at large.

Limitations and future research

Like any other previous studies, this study also contains some limitations. The first cautionary note would be regarding the sample. This research applies particulars of SCT framework to one faculty setting i.e., engineering graduates from the top-tier engineering institutes in India. Thus, before deducing a right-away inference, future scholars should test the model in different faculty contexts, which will contribute to the generalizability of results. Secondly, this research is not above the conventional limitations, primarily drawn from erstwhile scholars’ preference to predict intention only, not the actual behavior, although extensive empirical research across various social science domains quite categorically established the link between behavioral intention and actual behavior (Ajzen 1991). Thus, if future studies effort to extend this model up to behavior i.e., these graduates’ actual career selection, it would bring more detailed understanding of intention-behavior link. Lastly, this study only examines EI dynamics from the perspectives of 15 top-most engineering-college students, thus the empirical findings would be suitable for generalization in similar educational and social context.

In future, researchers may extend insights from this study to apply in longitudinal measures of student engagement in entrepreneurship. That will verify whether those students who show a higher level EI at their graduation days, does really act on their early-adult love for entrepreneurship? Or they just settle down with well-compensated jobs and rewarding careers, considering the bouncy path of entrepreneurship. It will further help future researchers to understand how does a novice engineer react in a real entrepreneurial environment? While conducting such research, one should include campus start-up intensity, per capita seed-fund, institution-level unemployment rate and the existence of venture partners. A multi-country approach will help future researchers to address the generalizability concern. Finally, although several limitations, this investigation will extend EI scholarship by developing a meaningful understanding of the topic, while applying this research-framework in diverse contexts to bring new insights.

References

Ajzen, I. (1987). Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 1–63.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Boulder: Westview Press.

Ames, D. R., Rose, P., & Anderson, C. P. (2006). The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(4), 440–450.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Arora, P., Haynie, J. M., & Laurence, G. A. (2013). Counterfactual thinking and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The moderating role of self-esteem and dispositional affect. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(2), 359–385.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Princeton-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

BarNir, A., Watson, W. E., & Hutchins, H. M. (2011). Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(2), 270–297.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587.

Baumgartner, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(2), 139–161.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. The Journal of Political Economy, 98(5 Part 1), 893–921.

Biraglia, A., & Kadile, V. (2017). The role of entrepreneurial passion and creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions: Insights from American homebrewers. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 170–188.

Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18, 63–63.

Brüderl, J., & Preisendörfer, P. (1998). Network support and the success of newly founded business. Small Business Economics, 10(3), 213–225.

Busenitz, L. W., Gomez, C., & Spencer, J. W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003.

Busenitz, L. W., & Lau, C. M. (1996). A cross-cultural cognitive model of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 20(4), 25–40.

Byabashaija, W., & Katono, I. (2011). The impact of college entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention to start a business in Uganda. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 16(01), 127–144.

Camerer, C., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. The American Economic Review, 89(1), 306–318.

Cardon, M. S., Gregoire, D. A., Stevens, C. E., & Patel, P. C. (2013). Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 373–396.

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532.

Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1090–1098.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

Charney, A. H., & Libecap, G. D. (2003). The contribution of entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the Berger program. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 1(3), 385–418.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

Corbett, A. C. (2007). Learning asymmetries and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 97–118.

Crant, J. M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(3), 42.

DeNisi, A. S. (2015). Some further thoughts on the entrepreneurial personality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 997–1003.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2006). Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management, 17(4), 263–282.

Dohse, D., & Walter, S. G. (2012). Knowledge context and entrepreneurial intentions among students. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 877–895.

Douglas, E. J. (2013). Reconstructing entrepreneurial intentions to identify predisposition for growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 633–651.

Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 81–90.

Espíritu-Olmos, R., & Sastre-Castillo, M. A. (2015). Personality traits versus work values: Comparing psychological theories on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1595–1598.

Fairlie, R. W., & Holleran, W. (2012). Entrepreneurship training, risk aversion and other personality traits: Evidence from a random experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 366–378.

Fiet, J. O. (2001). The theoretical side of teaching entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 1–24.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). McGraw-Hill series in social psychology. Social cognition (2nd ed.). New York: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Forza, C. (2002). Survey research in operations management: A process-based perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), 152–194.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 696–706.

Gorman, G., Hanlon, D., & King, W. (1997). Some research perspectives on entrepreneurship education, enterprise education and education for small business management: A ten-year literature review. International Small Business Journal, 15(3), 56–77.

Grijalva, E., Harms, P. D., Newman, D. A., Gaddis, B. H., & Fraley, R. C. (2015). Narcissism and leadership: A meta-analytic review of linear and nonlinear relationships. Personnel Psychology, 68(1), 1–47.

Haase, H., & Lautenschläger, A. (2011). The ‘teachability dilemma’of entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 145–162.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (Vol. 7). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hannon, P. D. (2005). The journey from student to entrepreneur: A review of the existing research into graduate entrepreneurship. In IntEnt2005 conference. London: University of Surrey.

Hansemark, O. C. (2003). Need for achievement, locus of control and the prediction of business start-ups: A longitudinal study. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24(3), 301–319.

Hartog, J., Van Praag, M., & Van Der Sluis, J. (2010). If you are so smart, why aren’t you an entrepreneur? Returns to cognitive and social ability: Entrepreneurs versus employees. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 19(4), 947–989.

Hayward, M. L., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science, 52(2), 160–172.

Hessels, J., van Gelderen, M., & Thurik, R. (2008). Drivers of entrepreneurial aspirations at the country level: The role of start-up motivations and social security. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(4), 401–417.

Hindle, K. (2007). Teaching entrepreneurship at university: From the wrong building to the right philosophy. Handbook of Research in Entrepreneurship Education, 1, 104–126.

Isaacson, W. (2011). Steve jobs. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Kanbur, S. R. (1982). Entrepreneurial risk taking, inequality, and public policy: An application of inequality decomposition analysis to the general equilibrium effects of progressive taxation. Journal of Political Economy, 90(1), 1–21.

Katz, J. A. (1994). Modelling entrepreneurial career progressions: Concepts and considerations. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 19(2), 23–40.

Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697–707.

Kernberg, O. F. (1979). Regression in organizational leadership. Psychiatry, 42(1), 24–39.

Kickul, J., & D’Intino, R. S. (2005). Measure for measure: Modeling entrepreneurial self-efficacy onto instrumental tasks within the new venture creation process. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 39–47.

Ko, S., & Butler, J. E. (2007). Creativity: A key link to entrepreneurial behavior. Business Horizons, 50(5), 365–372.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58.

Korunka, C., Frank, H., Lueger, M., & Mugler, J. (2003). The entrepreneurial personality in the context of resources, environment, and the startup process—A configurational approach. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 28(1), 23–42.

Kostova, T. (1997). Country institutional profiles: Concept and measurement. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 1997, No. 1, pp. 180–184). Academy of Management.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–432.

Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 577–598.

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Acs, Z. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38(8), 879–891.

Lee, D. Y., & Tsang, E. W. (2001). The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4), 583–602.

Lee, S. H., & Wong, P. K. (2004). An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 7–28.

Linan, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257–272.

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617.

Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195–218.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114.

Lubit, R. (2002). The long-term organizational impact of destructively narcissistic managers. The Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 127–138.

Lumpkin, G. T. (2007). In J. R. Baum, M. Frese, & R. A. Baron (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship., SIOP organizational frontiers series Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

Ma, H., & Tan, J. (2006). Key components and implications of entrepreneurship: A 4-P framework. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(5), 704–725.

Marques, C. S., Ferreira, J., Rodrigues, R. G., & Ferreira, M. (2011). The contribution of yoga to the entrepreneurial potential of university students: A SEM approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 255–278.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Mathieu, C., & St-Jean, É. (2013). Entrepreneurial personality: The role of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 527–531.

McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

McClelland, D. C. (1987). Characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 21(3), 219–233.

McGrath, R. G., & MacMillan, I. C. (2000). The entrepreneurial mindset: Strategies for continuously creating opportunity in an age of uncertainty (Vol. 284). Cambridge: Harvard Business Press.

McMullan, W. E., & Kenworthy, T. P. (2008). Creativity and entrepreneurial performance. Cham: Springer.

McMullan, W. E., & Long, W. A. (1987). Entrepreneurship education in the nineties. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(3), 261–275.

Miller, D. (2015). A downside to the entrepreneurial personality? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 1–8.

Miralles, F., Giones, F., & Riverola, C. (2016). Evaluating the impact of prior experience in entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 791–813.

Miron, D., & McClelland, D. C. (1979). The impact of achievement motivation training on small businesses. California Management Review, 21(4), 13–28.

Moriano, J. A., Molero, F., Topa, G., & Mangin, J. P. L. (2014). The influence of transformational leadership and organizational identification on intrapreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(1), 103–119.

Mueller, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship in the region: Breeding ground for nascent entrepreneurs? Small Business Economics, 27(1), 41–58.

National Institutional Ranking Framework (Rep.). (2017). Retrieved June 18, 2017, from MHRD, Govt. of India website: https://www.nirfindia.org/EngineeringRanking.html.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Owens, K. (2004). An investigation of the personality correlates of small business success. Dissertation Abstracts International, 65, 470B.

Padilla-Meléndez, A., Fernández-Gámez, M. A., & Molina-Gómez, J. (2014). Feeling the risks: Effects of the development of emotional competences with outdoor training on the entrepreneurial intent of university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 861–884.

Peterson, C. (2000). The future of optimism. American Psychologist, 55, 44–55.

Phillips, J. M., & Gully, S. M. (1997). Role of goal orientation, ability, need for achievement, and locus of control in the self-efficacy and goal-setting process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 792–802.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.