Abstract

Despite the fact that the increasing involvement of the private sector in pension provision has brought more flexibility to the pay-out phase of retirement, little is known about the characteristics of those who choose to annuitize their pension wealth and those who do not. I combine unique micro-data from a large Swedish occupational pension plan with rich national administrative data to study the choice between life annuities and fixed-term payouts with a minimum payout length of 5 years for 183,000 retiring white-collar workers. I find that low accumulation of assets is strongly associated with the choice of the 5-year payout. Consistent with individuals selecting payout length based on private information about their mortality prospects, individuals who choose the 5-year payout are in worse health, exhibit higher ex-post mortality rates and have shorter-lived parents than annuitants. Individuals also seem to respond to large, tax-induced changes in annuity prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ongoing shift in pension provision from defined benefit (DB) to defined contribution (DC) has brought more flexibility not only to the accumulation phase of retirement, but also to the decumulation phase. Flexibility during the decumulation phase manifests itself primarily through the introduction of more liquid payout options, such as lump sums and phased withdrawals, alongside the traditional life annuity.Footnote 1 Payout phase design involves a trade-off between flexibility and protection from longevity risk. Liquid payout options allow individuals to invest, buy an annuity, leave bequests or increase consumption during the early years of retirement, but raise concerns that they may trigger individuals to spend the money too rapidly for their own good (Barr and Diamond 2008). Despite the fact that many countries and private pension plan sponsors have referred to this trade-off to motivate their specific payout phase design, little is known about the characteristics of those who choose to annuitize and those who do not.

The main reason for the limited amount of empirical research on the demand for different payout options is the lack of reliable and comprehensive data. Private pension sponsors and life insurance companies are often reluctant to disclose individual choices, and most public pension systems impose mandatory annuitization. Survey-based data contain rich background information on the retirees, but usually lack actual payout decisions. Studies that use data provided by private annuity companies do contain rich information on annuity choices and prices, but are limited with respect to individual background information.

This paper uses unique micro-data from a large Swedish occupational pension plan to study the payout decision at retirement. The data are supplied by the second largest occupational pension sponsor in Sweden and include real payout decisions of about 183,000 white-collar workers. The payout decision involves substantial amounts of retirement savings, as workers are required to contribute a fraction of the wage to whatever occupational pension plan the employer is affiliated to. The company data are merged with national administrative data from Statistics Sweden to get rich individual background information, such as labor market history, education level, health status and parent longevity. To my knowledge, this is the first paper to combine data from a private life insurance company with administrative data to study the determinants of annuitization.

Previous empirical studies on the determinants of annuitization have tried to explain the so-called annuity market participation puzzle. The precise nature of the annuity puzzle is not well defined, but traditionally refers to the contradictory nature of low annuitization rates in the private market for annuities in the USA and the theoretical predictions of standard standard neoclassical life-cycle model (Benartzi et al. 2011). A seminal paper by Yaari (1965) shows that risk averse individuals without bequest motives will always prefer to hold their assets in actuarial notes (buy an annuity) rather than ordinary notes. A number of explanations have been proposed to explain the low demand for life annuities; the presence of load factors arising from administrative costs, incomplete markets and adverse selection (Mitchell et al. 1999; Finkelstein and Poterba 2002, 2004); bequest motives (Friedman and Warshawsky 1990; Brown 2001; Inkmann et al. 2011; Ameriks et al. 2011; Lockwood 2012); annuity prices (Warner and Pleeter 2001; Fitzpatrick 2012; Chalmers and Reuter 2012); means-tested government benefits (Bütler et al. 2011; Pashchenko 2013); and pre-annuitized first-pillar pension income (Bernheim 1992; Dushi et al. 2004; Beshears et al. 2011). More behaviorally oriented phenomena, such as loss aversion, default provision and framing, have also been put forward as potential explanations for the annuity puzzle (Brown 2007; Brown et al. 2008; Agnew et al. 2008; Benartzi et al. 2011; Beshears et al. 2014).

The payout decision I study in this paper concerns whether individuals withdraw their occupational pension as a life annuity or during a fixed number of years. Under the life annuity, the individual’s pension capital is converted into a monthly payment stream that is paid out as long as the individual is alive. In the fixed-term payout options, the individual specifies the time period during which the pension capital should be withdrawn. Payments cease after the preferred time period has expired. Payments also cease if the individual dies before the specified payout period has elapsed.Footnote 2 The fastest rate at which the pension capital can be withdrawn is over 5 years.

The average annuitization rate over the whole period is 76 %. This number is comparable to the annuitization rates in papers that study similar pension settings (Chalmers and Reuter 2012; Bütler and Teppa 2007). Thus, studies on payout decisions in mandatory second pillar pension plans, including this one, raise less concerns about the existence of an annuity puzzle than what the size of private annuity markets does.Footnote 3 Under the period of study, 2008–2013, the fraction of retirees choosing fixed-term payout options rose from 20 to 31 %. The 5-year payout is by far the most popular fixed-term payout option, chosen by more than two-thirds of the individuals who did not choose the life annuity.

I carefully analyze some of the determinants of annuitization that have been discussed in the literature. I pay particular attention to the role of health and life expectancy (adverse selection), retirement wealth and the tax consequences of choosing different payout options. As for adverse selection, I analyze whether there are systematic relationships between the length of the payout on the one hand and ex-post mortality on the other. I also investigate whether individuals in bad health self-select into fixed-term payouts. Health is proxied by the number of days an individual has been absent from work due to illness during a pre-specified age interval prior to retirement. Finally, I use information on parent mortality to create proxies for an individual’s life expectancy.

The results show that individuals in bad health are more likely to choose the 5-year payout. Ex-post mortality rates also signal the presence of adverse selection. Individuals who choose the 5-year payout are 59 % more likely to die within two years after claiming than annuitants. I also find that the parents of annuitants live longer than the parents of those who choose the 5-year payout. This suggests that individuals form expectations about how long they are likely to live based on the life-span patterns of their parents and take this into account when they decide whether to annuitize or not.

Small stocks of pension capital are more likely to be withdrawn during a fixed number of years. Although small capital stocks often signal low pre-retirement income, this effect seems to be mainly driven by channels associated with the size of the capital stock rather than by the income level of the individual. Payout preferences are fairly constant across the income distribution, except among individuals at the very top. High-income individuals, particularly those with large capital stocks, are much less likely to choose the 5-year payout. One potential explanation for this is that they want to avoid a higher effective marginal tax rate. I develop a tax-adjusted measure of the money’s worth ratio (MWR) of the life annuity to study the effect of tax-induced changes in annuity prices on the decision to annuitize.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief description of the Swedish pension system, with emphasis on the structure of the occupational pension plan for white-collar workers. The potential determinants of the demand for different payout options are discussed in Sect. 3. Section 4 describes the data, and Sect. 5 reports the results from several empirical specifications. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background information

In this section, I describe the main components of the Swedish pension system. I pay particular attention to the structure of the occupational pension system, in which individuals face different payout options.Footnote 4

2.1 The structure of the Swedish pension system

Sweden’s pension system has two main pillars, a universal public pension system and an occupational pension system for workers whose employer is tied to some occupational pension plan. Participation in the second pillar is mandatory for these employees. The public pension is the most important source of pension income, amounting to 50–80 % of an individual’s total pension income. Mandatory annuitization applies to all pension wealth in the public pension system. The public pension system has in itself three tiers, of which two are earnings-related and DC. They insure income up to a certain threshold level called the “income ceiling”.Footnote 5 The third tier is a means-tested pension supplement that ensures individuals with no or low pension income from the earnings-related component a minimum standard of living in retirement.

The second pillar consists of a number of different occupational, employer-provided pension plans. Occupational pension plans are constructed and thought of as supplements to the public pension system, as they provide pension benefits above the income ceiling in the public pension system. The occupational pension therefore plays a more important role for total retirement income for individuals with earnings above the ceiling than for those below. Contributions to the second pillar are essentially proportional to insured income up to the income ceiling. The employer is mandated to contribute between 4 and 6 % of the wage portion of the insured that does not exceed the income ceiling. For wage portions above this threshold, contribution rates are much higher, typically around 30 %. There is also a third pillar for voluntary savings available to anyone who cares to supplement the retirement income provided by the first two pillars.

2.2 Occupational pension for white-collar workers

Most occupational pension plans are designed and implemented at the union level. There are four large agreement-based occupational pension plans that cover around 90 % of the total work force. Two of these plans cover workers employed in the public sector. The other two pension plans cover white-collar workers and blue-collar workers in the private sector, respectively. This study focuses on payout patterns in the pension plan for white-collar workers.

In the last two decades, all major occupational pension plans have undergone significant changes. Most importantly, all plans have been changed from DB to DC or a mixture of the two. In the old DB-dominated regime, individuals had relatively little control over their occupational pension assets. Transferability of accumulated assets was limited, and benefits after retirement were typically received in the form of life annuities. The transition to DC has had important implications for the control individuals have over their assets. In particular, all pension plans have introduced fixed-term payouts as an alternative to lifelong annuities. Since the transition to DC is still ongoing, the majority of today’s retirees still have some part of their occupational pension wealth in old DB plans where annuitization is mandatory. White-collar workers, however, face no restriction on the fraction of wealth that can be withdrawn during a fixed number of years.Footnote 6 More on this below.

The pension plan for white-collar workers is called ITP. The transition of the ITP plan to DC began as late as in 2006, which implies that all cohorts in my sample belong to the old pension plan.Footnote 7 The most important source of occupational pension income for white-collar workers in this pension plan is DB. This component is referred to as ITP2.Footnote 8 Mandatory annuitization applied to all ITP2 benefits up until 2008 when fixed-term payouts were introduced. In fact, ITP2 is the only DB plan in Sweden that allows for fixed-term payouts. Because the payout decision accrues to all ITP2 pension wealth, substantial amounts are at stake in the payout decision among this group of workers.

Employer-sponsored contributions to the second pillar are managed by some occupational pension company. Each pension plan has its own “default” managing company, meaning that if the individual takes no action, her pension assets will be managed by that pension plan’s default company. Importantly, the ITP plan does not allow individuals to transfer DB assets between pension companies. Self-selection out of the default managing company, Alecta, which provides the data used in this paper, is therefore not an issue. Neither is adverse selection in the sense that only individuals who expect to live long insure themselves an issue because the ITP plan covers around 90 % of the population of Swedish white-collar workers.Footnote 9

The normal retirement age for white-collar workers is 65. A few months before plan participants reach this age, they receive information about the available payout options from the managing pension company. The information letter clearly states the size of the monthly benefit under each payout option. If the participant takes no action, the ITP2 pension is paid out as a life annuity from age 65. However, opting out is easy and requires no time-consuming paperwork. The individual simply ticks the box that corresponds to the preferred payout option in the information letter.

The life annuity guarantees the retiree a stream of money right up until the point of death, whereas payments cease after a certain date under the fixed-term payout options. Fixed-term payments also cease if the individual dies before the end of the term. There are different conversion factors for each payout option, i.e., the factor at which the accumulated pension capital is converted into a monthly payment. The conversion factors depend on assumptions about average life expectancy at each claiming age and the rate of return on the pension capital, but is independent of gender and marital status. The resulting monthly benefit is increased with the inflation rate. The occupational pension plan I study in this paper offers five payout options: a life annuity, or fixed-term payouts over 5, 10, 15 or 20 years.Footnote 10

2.3 Tax treatment of occupational pension income

Retirement income from public and private pension plans is subject to the same tax rules as income from labor.Footnote 11 A proportional local tax rate applies to all earned income and taxable transfers which includes pension income. The mean local income tax in 2013 was 31.73 % with a minimum rate of 28.89 and a maximum rate of 34.52. For pension incomes above a certain threshold (SEK 450,300 in 2013; 1 USD = 6.5 SEK), the taxpayer also has to pay a central government (state) income tax. The state income tax schedule consists of two brackets; the marginal tax rates in each bracket are 20 % (for incomes between 450,200 and 620,600 in 2013) and 25 % (for incomes above 620,600), respectively. Before computing the individual’s tax liability, a basic deduction is made against the individual’s total income. The basic deduction is phased in at lower income levels and phased out at higher income levels with consequences for the marginal tax rate in these income intervals.Footnote 12

The progressivity of the tax schedule will have implications for individuals’ valuation of different payout alternatives in the occupationalpension, especially for high-income earners with incomes above the state tax threshold.

3 Empirical predictions

This section summarizes the potential determinants of annuitization that have been discussed in the literature and that can be tested empirically with the data at hand.

The choice between the life annuity and any of the fixed-term payout options should depend on the expected present discounted value (EPDV) of each payout option. The EPDV of a particular payout depends in turn on the price of that payout option, the discount rate and on the characteristics of the individual. Asymmetric information about retiree life expectancy is the most natural source of variation in the EPDV of a given payout option across individuals.

In a standard life-cycle model, life annuities provide higher rates of return than other risk-free investments, because they transfer assets from those who die to those who survive. The additional rate of return on life annuities is referred to as the “mortality premium”.Footnote 13 However, because fixed-term payouts also transfer assets from those who die before the preferred time period has elapsed to those who survive it is not clear that the life annuity should provide a higher rate of return. As shown below, the EPDV of the ITP life annuity is close to the EPDV of the fixed-term payouts. Moreover, if there is an option value associated with holding liquid assets, fixed-term payouts should become even more attractive.

3.1 Health, mortality and life expectancy

An individual’s health condition and life expectancy should influence the annuitization decision because annuities hedge longevity risk. If individuals recognize and respond to variation in the relative value of different payout options that is due to differences in longevity, individuals who expect to live long should prefer life annuities to fixed-term payouts with short payment horizons and vice versa.

The most compelling evidence of the presence of adverse selection in life annuity markets is when ex-post mortality rates are lower among those who buy life annuities than among those who do not. Finkelstein and Poterba (2004) report evidence of adverse selection of long-lived individuals into private annuity markets in the UK. Because fixed-term payouts were introduced in 2008, I can track mortality only within a few years after the claim was made. If there is adverse selection, ex-post mortality rates should be higher among individuals who choose fixed-term payouts.

I get information about an individual’s health status from social insurance register data. The most straightforward health measure is based on the number of days an individual has been absent from work due to sickness. The medical literature has shown that sickness absence can be used as an integrated measure of physical, psychological and social functioning in studies of working populations (Marmot et al. 1995; Kivimäki et al. 2003).

However, health is a non-perfect measure of subjective life expectancy. Two individuals with similar health status can have very different beliefs about how long they are likely to live relative to the cohort average. Such differences in beliefs might reflect family-specific rather than individual-specific characteristics. A very intuitive and simple way for an individual to get information about how long she is likely to live is to look at life-span patterns of family members. It has been shown that individuals take (same-sex) parent longevity into account when assessing their own life horizons (Van Solinge and Henkens 2009). I use information about the age at death of individual i’s parents to proxy individual i’s life expectancy.

3.2 Retirement wealth

Wealth has been shown to be an important determinant of the payout decision.Footnote 14 Ideally, wealth should be measured before annuitization takes place and include both pension and non-pension financial wealth. However, because the data do not contain information on non-pension financial wealth, the analysis is restricted to (occupational) pension wealth. Non-pension wealth is proxied by a measure of permanent income.

Pension income from other occupational pension plans and the public pension system should be thought of as pre-annuitized wealth.Footnote 15 These may act as substitutes for a life annuity in the ITP plan. Because the marginal value of insurance declines with the level of insurance, the value that a retiree attaches to the incremental life annuity should fall with the level of pre-annuitized income.

I predict that retirees who are more reliant on ITP benefits because they spent most of their career working for ITP employers should be more likely to choose the life annuity. The marginal effect of income from other occupational pension plans on the probability of choosing the life annuity should therefore be negative. However, the relationship between retirement wealth and payout preferences is potentially more complex than this. First, it has been shown that small outcomes are discounted at higher rates than greater ones are (Frederick et al. 2002). Individuals with low levels of occupational pension wealth might find life annuities unattractive since their wealth would be translated into a very small payment stream. Low levels of retirement wealth would then be associated with a higher propensity to cash out the money at the fastest possible rate, i.e., over 5 years. At the same time, low levels of capital might be the result of high discount rates due to low investment in education. Second, if individuals prefer to cash out small amounts of retirement wealth and if the researcher has an incomplete picture of individuals’ payout decisions in different pension plans, low annuitization rates might reflect the distribution of account balances rather than the distribution of preferences (Benartzi et al. 2011).

Another reason why we would expect individuals to withdraw their pension during a fixed number of years is to become eligible for different kinds of means-tested benefits after the pension payments have ceased. Indeed, Bütler et al. (2011) show that the availability of means-tested benefits can reduce the desired annuitization levels substantially. This “moral hazard” issue is, however, difficult to investigate empirically in the context of this paper. Not enough time has passed since the introduction of fixed-term payouts to see whether individuals who choose the 5-year payout are more likely to receive means-tested benefits 5 years after claiming.

3.3 Annuity pricing and tax treatment

Variation in the value of life annuities arise not only from differences in retiree characteristics, but also from differences in annuity pricing. An individual should prefer the annuity if the price of the annuity is lower than the expected benefit from smoother lifetime consumption. Chalmers and Reuter (2012) show that retirees respond very little or nothing at all to changes in the price of the life annuity option. They argue that low price elasticities of demand are due to the complexity of evaluating the EPDV of different payout options. However, based on the relatively high demand for the better than actuarially fair-priced life annuity that they observe, they suggest that retirees may still respond strongly to large, salient changes in annuity prices. This notion is supported by Bütler et al. (2013) who find that a large 20 % reduction in the rate at which capital is translated into an annuity reduced the propensity to annuitize by about 8 percentage points.

Large changes in the value of life annuities can arise from the tax treatment of retirement income. The progressivity of the tax schedule implies that the effective marginal tax rates under the fixed-term payouts are higher than under the life annuity. In this section, I extend the traditional measure of an annuity’s value, the “money’s worth ratio” (MWR), to account for the tax treatment of pension income.Footnote 16

The MWR of a life annuity is the ratio of the EPDV of the flow of payments made by an annuity to the money paid for an annuity, where the money paid for an annuity typically refers to the foregone lump sum payment. In my setting, the value of the money paid cannot be determined since there is no lump sum option, nor information in the data on the exact amount of contributions paid to the ITP plan. This implies that the EPDV of the life annuity must be related to the EPDV of each fixed-term payout option in order to find the MWR of the life annuity. The EPDV of payout option \(p\) purchased by an individual of gender \(g\) and age \(a\) in year \(t\) is given by:

where \(\pi _{a,a+i}\) is the probability of someone living \(i\) more years, believed at age \(a\), \(B^{p}\) is the annual gross benefit received by an individual under payout option \(p\), \(r_{t}\) is the appropriate discount rate for payments received in year \(t\), expressed at an annual rate, and \(T\) is the last period of payment.Footnote 17 For life annuities, \(T\) is chosen so that \(\pi _{t,T} \approx 0 \), which happens when \(T=45\) (i.e., no one lives beyond age 110 years, assuming \(a=65\)). For the 5-year payout option, \(T=5\), for the 10-year payout option \(T=10\) and so on.

The MWR of the life annuity is then the ratio of the EPDV of the life annuity to the EPDV of any of the fixed-term payout options. For example, the MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout option is expressed as:

If this expression is equal to one, the life annuity and the 5-year payout have equal EPDVs.

The net-of-tax MWR is defined as the ratio between the EPDV of the net benefit under the life annuity and the EPDV of the net benefit under any of the fixed-term payout options. I replace the gross benefit \(B^{p}\) in Eq. 1 with the net benefit \(B^{p,net}\). The net benefit is given by

where \(T(B^{p},I,t)\) is total taxes paid under payout option \(p\), \(T(0, I, t)\) is total taxes paid when the individual has no pension income from the ITP plan, \(I\) is other pension income and \(t\) is the claim year.Footnote 18 The average tax rate is then given by:

Table 1 reports average tax rates and MWRs for three representative individuals. The first row reports the gross benefit, \(B^{p}\), under the life annuity. The second row reports the corresponding net benefit. Due to the progressivity of the tax schedule, the average tax rate decreases with the length of the payout for a given level of income. Short payout horizons result in higher monthly income and higher marginal taxes. Note that the average tax rate for the low- and middle-income individuals is only two percentage points higher under the 5-year option than under the life annuity compared to more than 13 percentage points for the high-income individual. For the high-income individual, this corresponds to an increase in the average tax rate of 38 %. The reason for this is that the high-income individual reaches the state income tax threshold under the 5- and 10-year payout options.

The table also reveals that the gross MWR of the life annuity with respect to each fixed-term payout is somewhat below one. In fact, the EPDV of the life annuity is larger than the EPDV of the 5-year payout only for discount rates below 1.1 %. Because fixed term payouts yield similar, or even higher, expected returns than the life annuity, it is hard to motivate why low annuity demand in this setting would reflect an “annuity puzzle”.

The picture changes when taxes are taken into account. The net-of-tax MWR calculations show that the fixed-term payouts become less attractive relative to the life annuity. This is particularly true for the 5-year payout. For example, the MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout for the middle-income individual increases from 0.96 to 0.98 when taxes are accounted for. The corresponding net MWR for the high-income individual amounts to as much as 1.20. These changes reflect average tax rate differences across income levels and payout options.

The variation in net MWR across individuals will be used in the empirical analysis. First, I calculate the net MWR of the life annuity with respect to each fixed-term payout option for each individual.Footnote 19 Following the literature, the net MWR is then added as a regressor to predict payout choice.Footnote 20

Another way to investigate the importance of the tax effect is to look at individuals who are exposed to different marginal tax rates depending on their payout choice. For this reason, I identify individuals who are subject to state income tax only under the 5-year option. Because the net EPDV of the 5-year payout is substantially lower than the corresponding gross EPDV due to a higher marginal tax rate, these individuals should be less likely to choose the fixed-term payouts.

3.4 Bequest motives, socioeconomic background and demographic characteristics

Differences in retiree characteristics that relate to socioeconomic background and demographics can also generate cross-sectional differences in the expected utility associated with life annuity payments.

Bequest motives have been put forward as one of the most important explanations for the annuity puzzle. In the absence of bequest motives, any wealth that an individual is holding at death does not contribute to utility, so there is no reason to forego the higher rate of return on annuities that arises from the mortality premium (Brown 2001). However, the preference for leaving bequests may counteract the insurance benefits of annuities and make more liquid payout options relatively more attractive.

Empirical findings on the effects of bequest motives on payout decisions are mixed. To test for the effect of bequest motives, researchers typically proxy intentional bequest motives with the presence of children. Brown (2001) and Inkmann et al. (2011) find insignificant effects of the number of children on the payout decision. Bütler and Teppa (2007) lack data on the presence of children, but find that divorced/widowed men cash out more than single men, which is indicative for the presence of a bequest motive. I follow the literature and proxy bequest motives with the presence of children.Footnote 21

As mentioned, the conversion factors do not depend on gender. Because women live longer than men on average, there is an actuarial bias that makes annuitization more attractive for women. The gross MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout for women is 0.99 compared to 0.92 for men, which means that the EPDV of the life annuity is almost 9 % higher for women. The results in the literature with respect to gender are mixed. Inkmann et al. (2011) and Bütler and Teppa (2007) report higher cash-out rates for women, probably reflecting availability of alternative sources of income, whereas Chalmers and Reuter (2012) find the opposite.

Labor market participation at the time of withdrawal might also impact the decision to annuitize. The tax consequences of positive labor income after retirement, particularly in combination with large pension capital stocks, might drive down the demand for fixed-term payouts.

4 The data

4.1 The data sets

I use data from a pension company called Alecta. Alecta manages occupational pensions for approximately two million private customers, making it the second largest occupational pension company in Sweden and one of the largest owners on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. Alecta is the default managing company of the ITP plan which means that they administrate pension contributions and pension payouts for private-sector white-collar workers whose employer is part of the ITP plan.

The data consist of information on all Alecta’s customers that retired over a six-year period ending in 2013. The sample includes 182,808 individuals born between 1943 and 1951. Most importantly, it contains information on the year and month each retiree claimed the occupational pension and under which payout option it is withdrawn. It also contains the relevant conversion factors for claims at age 65. The payout decision concerns pension wealth in the DB component, ITP2, which is tied to Alecta.

The company data are merged with register data from Statistics Sweden to obtain rich individual background information. The data are derived from the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA). LISA covers the period 1990–2011, which implies that I can create panels of past income streams for each individual in the sample. From the panel structure of the register data, I construct one observation per retiree with variables that are likely to be determinants of the payout decision. The data also contain birth and mortality information for the biological parents of these individuals.

Since the register data end in 2011, there is no contemporaneous income information for individuals who retire in 2012 and 2013. In order to get a full picture of the post-retirement financial situation of these individuals, I restrict the sample to payout choices made in or before year 2010 when the analysis includes current income streams, such as labor market earnings, public pension benefits and pension income from other occupational pension plans. Losing three years of data reduces the sample size from 182,808 to 82,066.

Information on parents’ date of birth and mortality is available for 89 % of the sample. The remaining 11 % have parents who never lived in Sweden and do not show up in the registers for this reason. These individuals are excluded from the sample in the analysis of parent mortality and payout choice, which reduces the sample size to 162, 537.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for all key variables. All numerical variables are expressed in constant 2013 Swedish Crowns (SEK).

The average monthly benefit from the DB component, ITP2, amounts to SEK 4074. The large variation in the size of the benefit across individuals (standard deviation of SEK 6272) is a direct result of large differences in pre-retirement income and the construction of the ITP plan, which replaces more income above the income ceiling.

Pre-retirement income is defined as the average income from labor during the 5 years preceding retirement. The average monthly pre-retirement income is SEK 22,437. Permanent income is defined as the average monthly income between age 51 up to retirement. Permanent income should reflect lifetime earnings better than pre-retirement income, and is also more strongly correlated with retirement wealth. Active participation in the labor market after retirement (“Working” in Table 2) is defined as having labor earnings greater than two income base amounts in the year succeeding the claiming year.Footnote 22 In fact, more than 20 % are classified as working based on this definition.

We also see from the table that some white-collar workers receive pension income from other occupational pension plans. Other occupational pension income is defined as non-ITP occupational pension income that the individual receives in the last year that he or she is observed in the data. Because most people claim at age 65, this implies that other pension income is typically measured between ages 66–68 for those who claimed before 2011. On average, retirement benefits from the ITP plan make up 55.4 % of the total occupational pension income. 93 % receive income from some other occupational pension plan.Footnote 23 For 20 % of the sample, this income is three times larger than what they get from the ITP plan. Public pension benefits are on average 33 % larger than total occupational pension income.

For those who claim at age 65, the mean gross MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout is 0.94. The corresponding tax-adjusted MWR is equal to 0.96. As expected, the tax treatment of occupational pension income increases the EPDV of the life annuity relative to the fixed-term payouts. The average tax rate, as given by Eq. 4, is 33 % and around 10 % pay the additional state marginal tax rate of 20 %. State tax status is contingent on choosing the 5-year payout for 12.2 % of the sample.

The average claiming age is 64.8. ITP2 benefits can be withdrawn from age 55 with an early retirement penalty of 7 % per year. Almost 90 % claim the occupational pension when they turn 65. A number of factors contribute to this pattern: Pension rights are not earned after the age of 65, benefits are automatically paid out at this age, and 65 is usually referred to as the “normal retirement age”. Thus, there is a strong norm that retirement should happen at this age. As seen in Table 2, the average age at which public pension benefits are claimed (64.2) is somewhat lower than the average age at which ITP benefits are claimed (64.8).Footnote 24

39.3 % of the sample are women. An individual’s marital status is based on what is observed at the time of retirement. 67.7 and 32.3 % of the sample are marriedFootnote 25 and singles, respectively, and 4.4 % are widowed. A high school degree (12 years of schooling) is the highest education level for the majority (56 %). 23.6 % has a college degree (at least two years in college or university), and 20.4 % finished only elementary school (9 years or less).

Information on health and mortality is also collected from LISA. I use individual-specific information on sickness absence as a proxy for health.Footnote 26 I look at sickness absence incidence between age 51 up to retirement. The mean number of days per year of sickness absence in the sample is 15.7. About 43 % of the sample never received sickness benefits during this period.

Mortality data are available up to year 2012. For this reason, the sample is restricted to claims made before 2011 and 2009 when I look at mortality within two and four years after the claim date, respectively. 2.2 % of the sample die within two years after claiming and 4.3 % within 4 years. These mortality rates are sufficiently high to allow meaningful study of retiree mortality and adverse selection.

The ideal measure of life expectancy based on parent mortality would be to relate the age at death of the individual’s same-sex parent to the average age at death of that parent’s cohort. However, not enough time has passed to determine cohort mortality for all parent cohorts in the sample.Footnote 27 Instead, I create two dummy variables that take on the value of one if the individual’s same-sex parent is deceased/alive at age 65/90. An individual whose same-sex parent died before age 65 is likely to expect to live shorter than an individual whose same-sex parent was alive at age 90.Footnote 28

4.3 Payout choices (the dependent variable)

The payout choice variable is the outcome variable and takes on five different values as explained in Sect. 2: Individuals can withdraw their pension wealth over 5, 10, 15 or 20 years (fixed-term payouts) or as a life annuity.

Relative frequencies of the choice variable by year are reported in Table 3. Between 2008, the year in which the ITP plan introduced fixed-term payouts, and 2013, the fraction of people that chooses the life annuity decreased from 80.9 to 70.5 %. This averages to 75.9 % over the whole period. The 5-year payout option is the most popular alternative among the fixed-term payouts. As seen in column (7), 16.1 % of all retirees choose this option. However, the 10- and 15-year payout options have grown more in relative terms. The 10-year payout option, for example, was preferred by only 3.9 % in 2008, but by 7.8 % in 2013. Very few people (0.2 %) choose the 20-year payout.

There are two potentially important explanations for the decreasing demand of the life annuity. First, life annuities have become less attractive as a result of declining interest rates. When interest rates fall, annuity payouts are reduced for the same amount of pension capital. However, while the mean yield on ten-year Treasure notes fell from 3.90 to 2.12 % between 2008 and 2013, Alecta’s underlying assumption about the interest rate was changed only once during this period. In December 2012, the interest rate assumption was reduced from 3 % to 2 %, which generated a substantial drop in the gross MWR of about 7 percentage points. This relative price change possibly contributed to the falling demand for the life annuity in 2013, but given that the trend towards shorter payout horizons seem to have started more than two years before this, there might be other important forces at play.

The second explanation is that the trend toward shorter payout horizons is driven by an information or learning effect. Even though there is no direct empirical evidence of such an effect, knowledge about the existence of alternative payout options in second pillar pension plans has probably become more widespread in the most recent years as a result of more media attention. This implies that more people make active decisions and are less likely to be defaulted into the life annuity. Both from the viewpoint of the individual and the policy maker, the payout decision becomes an increasingly more important matter as the share of occupational pension wealth that is not subject to mandatory annuitization grows over time in all major occupational pension plans.

Table 4 reports relative frequencies of the choice variable by a number of individual characteristics. We see that the distribution of preferences varies substantially across some characteristics and less across others.

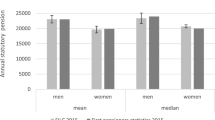

There are large differences in payout preferences between income groups. 76 % of the individuals in the bottom permanent income quartile choose the life annuity compared to 79.5 % in the top quartile. Only 9.7 % in the top quartile choose the 5-year payout, whereas 19 % do so in the bottom quartile. Differences are even more pronounced across the account balance distribution.Footnote 29 Only 68.3 % in the bottom account balance quartile annuitize (28.6 % choose the 5-year payout) compared to 82.9 % in the top quartile (6.2 % choose the 5-year payout). Individuals that continue to work after collecting the ITP benefit are more likely to annuitize than those who retire completely from the work force. Given the actuarial bias in favor of the life annuity for women, it is somewhat surprising that women choose the 5-year payout option more than men (18.7 vs. 14.4 %). There is also preliminary evidence that individuals compare the net-of-tax value of different payout options. Only 5.3 % of those who are subject to state income tax only under the 5-year payout choose this payout length. Individuals who die within 2 years of claiming are much more likely to choose the 5-year option, providing preliminary evidence of the presence of adverse selection.

5 Empirical results

This section investigates the individual-level determinants of annuitization. Table 5 reports marginal effects from a multinomial logit analysis applied to the pooled sample of individuals who claimed their ITP benefit between years 2008–2013. The reference category is the life annuity. The marginal effect associated with each coefficient can be interpreted as the variable’ incremental effect on the probability of choosing a fixed-term payout option.Footnote 30

Two sets of results are reported for each fixed-term payout. The model underlying the estimates in columns (1), (3) and (5) is estimated for the complete sample, whereas columns (2), (4) and (6) restrict the sample to individuals who claimed their ITP pension no later than in year 2010.Footnote 31 All specifications include a separate fixed effect for each year of claiming to control for variation in payout choices that is related to specific year effects. I also include a dummy for claiming before age 65 to control for variation in payout choices that is related to early retirement. All specifications also control for gender, marital status, the presence of children, education level, early retirement, log permanent income, sick leave absence and two dummies for parent longevity. In addition, columns (2), (4) and (6) add dummy variables to indicate whether the individual is working or not after retirement, whether the individual’s total pension income exceeds the state income tax threshold under the 5-year payout option only, and whether more than 75 % of the individual’s total occupational pension income comes from some other pension plan than the ITP plan. I also test for adverse selection by estimating logit models of the probability of dying within two and four years of claiming.Footnote 32 Table 6 reports the results from these estimations.

To evaluate the role of annuity pricing, I exploit tax-induced variation in the net MWR of the life annuity with respect to the fixed-term payouts. Adding the net MWR as a right-hand side variable would be straightforward in case the decision involved only two payout options. For example, studies that look at the choice between a lump sum and a life annuity use some appropriate measure of the relative value of the life annuity with respect to the lump sum to predict the probability to annuitize (Brown 2001; Bütler et al. 2011; Chalmers and Reuter 2012). However, with four payout alternatives to the life annuity, there are four potential individual-level regressors of the net MWR. Because of the popularity of the 5-year payout, I use the net MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout.Footnote 33 If individuals recognize and respond to tax-induced variation in life annuity pricing, then the demand for the fixed-term payout should be lower when the value of the life annuity is higher. The marginal effects from these estimations are reported in Table 7. Because the net MWR is a function of the level of ITP capital, other pension income, \(I\), and permanent income, I estimate the model both with and without controlling for these variables. I also estimate the model with and without controlling for gender because gender is the second source of variation in the net MWR alongside taxes. I report results for the 5- and 10-year payouts.Footnote 34

5.1 Health, mortality and life expectancy

The results with respect to health and life expectancy are broadly consistent with our predictions. Column (1) of Table 5 shows that individuals with more than 15 sick leave days per year on average are 2.9 percentage points more likely to choose the 5-year payout option. The estimate is somewhat lower but still significant when the sample is restricted to payout decisions made in 2010 or earlier. The corresponding effect on the demand for the 10-year payout option is very close to zero, and even negative for the last specification, as seen in columns (3) and (4).

The estimated coefficients on same-sex parent mortality are significant and have the predicted signs. The marginal effect of same-sex parent mortality at age 65 on the probability of choosing the 5-year payout option is 1 percentage point. Retirees whose same-sex parent was alive at age 90 decrease the demand for the 5-year payout by 0.9 percentage points. The corresponding effects for the 10-year payout are again smaller and amount to 0.3 and \(-\)0.3 percentage points, respectively. Thus, the parents of annuitants live longer than the parents of those who choose a fixed-term payout, which can be interpreted as evidence of adverse selection. A caveat of this interpretation could be that parent longevity picks up some of the variation in non-pension wealth that is not captured by any of the other variables.Footnote 35 We know that wealthier individuals tend to live longer (see, e.g., Smith 1999) and that wealth is an important determinant of annuitization. Thus, the possibility that some of the effect of parent longevity operates through non-pension wealth cannot be ruled out.

Table 6 reports marginal effects from a logit model on ex-post mortality and payout choice. Again, the estimated coefficients provide evidence pointing in the direction of adverse selection. Specifically, individuals who choose the 5-year payout are 1.7 and 1.3 percentage points more likely to die within four and two years after claiming, respectively. This corresponds to percentage effects of 40 and 59 %. In contrast, there is no self-selection of individuals who die shortly after retirement into any of the other fixed-term payout options. If anything, mortality rates among retirees who choose 10- or 15-year payouts are lower than among annuitants. These results support the general finding that individuals who enter retirement with low life expectancy or bad health tend to minimize the time period over which they withdraw their pension wealth.Footnote 36

5.2 Retirement wealth and annuity pricing

The coefficients on log permanent income in columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 show that higher permanent income is associated with a marginally positive effect on the probability of choosing the 5-year payout, given a certain level of retirement wealth. Because income is highly correlated with retirement wealth, it is difficult to evaluate the role of income when the model controls simultaneously for ITP retirement wealth. In fact, the sign of the log permanent income coefficient changes when the retirement wealth variables are excluded from the regression model (not reported here).

Based on the descriptive analysis in Sect. 4.3 and the regression estimates in Table 5, it is nevertheless clear that the size of the ITP benefit is an important predictor of payout choice. Columns (1) and (2) reveal that retirees in the bottom quartile of the account balance distribution are 11 percentage points more likely to choose the 5-year payout than those in the second and third quartile. Retirees in the top quartile, on the other hand, are 14.1 percentage points less likely to choose the 5-year payout on the margin. The demand for 10-year payouts is less related to the size of the ITP benefit. The coefficients on the dummies for being in the bottom and top quartile reflect marginal effects of \(-\)1.3 and \(-\)0.1 percentage points, respectively.

An alternative way to measure the impact of the size of the ITP benefit on the demand for fixed-term payouts is to replace the existing account balance dummies with the monetary value of the ITP benefit under the life annuity. Again, the larger the annuity payment, the lower the demand for the 5-year payout. The estimated coefficients (not reported here) are statistically significant and also economically meaningful with a one-standard deviation increase in the monthly life annuity payments (SEK 4860) decreasing the demand for the 5-payout by 17 percentage points. Bütler and Teppa (2007) also find that the marginal effect of pension wealth on the demand for life annuities is positive, but smaller than in this study. Chalmers and Reuter (2012), however, report that a one-standard-deviation increase in the life annuity payments increase the demand for the lump sum between 3.0 and 5.2 percentage points.

Columns (2), (4) and (6) of Table 5 show that the demand for fixed-term payouts decreases when retirees receive income from some other occupational pension plan next to the ITP plan. More specifically, if at least 75 % of the total occupational pension income is paid out from a non-ITP pension plan, the demand for the 5- and 10-year payout decreases by 6.0 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively. This result contradicts the prediction that retirees that are less reliant on ITP benefits should be less likely to annuitize. A possible explanation to this result is that individuals with multiple sources of occupational pension devote more attention and effort to the payout decisions of other, more important pension plans. The default option becomes particularly important for retirees who have contributed to different plans during their career. Note also that the magnitude of the coefficient on the bottom pension quartile becomes larger when we control for other occupational pension income. This suggests that retirees that are located in the bottom quartile of the account balance distribution because of low lifetime earnings are more likely to choose short payout periods than retirees who have small account balances because they spent large part of their careers working for employers outside the ITP plan.

As seen in column (1), retirees whose total retirement income exceeds the state income tax threshold only under the 5-year payout are more than 5 percentage points less likely to choose the 5-year payout. This suggests that individuals evaluate the benefit’s net-of-tax value for different payout lengths, rather than its gross value, at least when the tax effect is large and salient.

Turning to Table 7, which presents the marginal effects from a multinomial logit model of the net MWR on the demand for each fixed-term payout, we find further evidence that individuals respond to variation in the relative price of the life annuity. The marginal effect of the logit in specification (1) is \(-\)0.40 and is highly significant. This means that a one percentage point increase in the net MWR of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout leads to a 0.40 percentage point decrease in the probability of choosing the 5-year payout.

Controlling for gender (specification (2)) alters the impact of the net MWR substantially. The estimated marginal effect of \(-\)0.96 is both statistically and economically significant with a one-standard deviation increase in the net MWR of the life annuity being associated with a 7.0 percentage point reduction in the demand for the 5-year payout option. Because gender and taxes are the sole sources of variation in the net MWR, conditioning on gender implies that the estimate of the net MWR reflects tax-induced changes in the relative value of the life annuity only.Footnote 37 Adding income and retirement wealth controls (specification 3) reduces the estimated marginal effect of the net MWR to \(-\)0.39. The difference is due to the fact that there is not much variation left in the net MWR when we condition linearly on retirement wealth and permanent income. Ultimately, identification hinges on functional form. There is no variation left in the net MWR if one controls for retirement wealth and income in a very flexible way.

The demand for the 10-year payout also falls when the net-of-tax value of the life annuity increases relative to the 5-year payout. Specifically, column (5) reveals that a one percentage point increase in the net MWR of the life annuity leads to 0.03 percentage point decrease in the probability of choosing the 10-year payout.

The results can be compared to the findings of previous papers that study the relationship between annuity demand and the relative value of the annuity. Contrary to the findings of this paper and what economic theory would predict, Chalmers and Reuter (2012) find that an increase in the money’s worth of the life annuity leads to an increase in the demand for the lump sum. One reason for these opposite findings might be that tax-induced variation in the relative value of the life annuity is more salient and more easily understood than variation that stems from the use of multiple benefit formulas as in Chalmers and Reuter (2012).

The results of this paper are more in line with the findings of the group of papers that uses a related (utility-based) measure of the annuity’s value, namely the annuity equivalent wealth (AEW). Brown (2001) and Bütler et al. (2013) report that a one percentage point increase in the AEW leads to a one and 0.88 percentage point increase in the annuitization rate, respectively. Bütler and Teppa (2007) reports a somewhat lower marginal effect of 0.44 %. The column (2) estimate in Table 7 of \(-\)0.96 is thus close to previous studies, although the interpretation of these estimates is different to the extent that the MWR and the AEW capture different aspects of the value of a life annuity.

5.3 Bequest motives, socioeconomic background and demographic characteristics

I find no evidence of bequest motives having an effect on the payout decision. All coefficients on the presence of children in Table 5 for the 5- and 10-year payouts are close to zero and insignificant. Marital status also turns out to be an unimportant predictor of the payout decision. Columns (1) and (2) in Table 5 show that married retirees are 0.7 percentage points less likely to choose the 5-year option. Previous studies on the demand for life annuities have found significant and important effects of marital status on the demand for life annuities (Bütler and Teppa 2007; Inkmann et al. 2011; Chalmers and Reuter 2012). One potential reason why I find zero or very small effects is that the rich set of control variables pick up variation in the demand for life annuities that are correlated with marital status but not due to it.

From the results in Table 5, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the effect of being female per se. The estimates reveal almost zero marginal effects of being female on the demand for the 5-year option and a small negative effect on the demand for the 10-year payout. Thus, the raw gender difference of 4 percentage points in the demand for the 5-year payout that we saw in Sect. 4.3 can be explained by other variables, such as income and retirement wealth.Footnote 38 The high demand for fixed-term payouts among women is surprising given that the money’s worth of the life annuity is considerably higher for women than for men.

Labor market participation at the time of withdrawal has a negative impact on the probability of choosing any of the fixed-term payouts. The marginal effect on the demand for 5- and 10-year payouts of being classified as working after claiming amounts to \(-\)1.7 and \(-\)1.1 percentage points, respectively. Individuals who simultaneously receive labor and pension income may find fixed-term payouts unattractive for tax reasons.

Education also affects the payout decision. Retirees with low education (elementary school) are 1.0–1.4 percentage points more likely to choose the 5-year payout. Retirees with a college degree are less likely to choose the 5-year payout with an impact at the margin of about 1.3 percentage points. The positive correlation between education level and annuitization rates might reflect higher life expectancy among college graduates. Education is less important in explaining the demand for 10- and 15-year payouts.

Finally, individuals who retire before the normal retirement age are much less likely to annuitize. The estimated coefficient reveals that “early claimers” are 17 percentage points more likely to choose the 5-year payout and about 4.3 percentage points more likely to choose the 10-year payout than the life annuity. Chalmers and Reuter (2012), who find similar results for public servants in Oregon, suggest that such behavior might be explained by younger retirees using the lump sum to acquire new skills and re-renter the labor force. Among white-collar workers in Sweden, however, the combination of short payout horizons and early retirement is more likely driven by individuals who want to maximize their consumption possibilities during the years of early retirement. Compared to those who claim at age 65, early retirees receive larger benefits from the ITP plan, have significantly higher permanent income and are in better health.Footnote 39

6 Conclusion

This paper provides empirical evidence on the determinants of annuitization. The study is based on a unique data set which includes real payout decisions of about 183,000 white-collar workers in Sweden who started to withdraw their second pillar retirement wealth between 2008 and 2013. The data are supplied by the default managing company for the occupational pension plan for white-collar workers, ITP. The data are merged with national administrative data to obtain rich individual background information. The main analysis focuses on salient and easily understood variation in the value of life annuities and fixed-term payouts due to differences in retiree characteristics.

Participation in the second pillar is mandatory. The payout decision involves large amounts of money, focusing on retirement wealth in the defined benefit component, ITP2. Retirees face five payout options, including a life annuity and four fixed-term payouts withdrawn over 5, 10, 15 or 20 years, respectively. Fixed-term payouts should be an attractive alternative to the life annuity for individuals who prefer to invest the money on their own or enhance consumption possibilities during the early years of retirement. Approximately 76 % of the individuals in the sample choose to annuitize their pension wealth. This is a surprisingly high annuitization rate given that the EPDV of the fixed-term payouts is at least as high as that of the life annuity. Two-thirds of all fixed-term payouts are accounted for by the 5-year payout option.

I find clear evidence of adverse selection of shorter-lived individuals and individuals in bad health into the most liquid payout option. All else equal, expos mortality is higher among retirees who choose the 5-year payout than among annuitants. In fact, individuals who choose the 5-year payout are 59 % more likely to die within two years after claiming than annuitants. These individuals also have higher sickness absence rates prior to retirement. I find a negative relationship between same-sex parent longevity and the probability of choosing the 5-year payout. This suggests that individuals form expectations about how long they are likely to live based on the life-span patterns of their parents and take this into account when they decide whether to annuitize or not.

Compared to other similar settings that have been studied in the literature, annuitization rates vary more by account balance, but less by individual characteristics such as marital status, gender and income. Individuals in the top account balance quartile are 14–15 percentage points more likely to choose the life annuity than the 5-year payout, whereas low accumulation of retirement assets is strongly associated with choosing the 5- or 10-year payouts. One potential explanation for this pattern, also found in Bütler and Teppa (2007) and Hurd and Panis (2006), is differences in the rate of time preferences across individuals. Another one is that small outcomes are discounted at a higher rate than greater ones are.

Taxes are also likely to play an important role here. Due to the progressivity of the tax schedule, the effective marginal tax rates decreases with the length of the payout. I use tax-induced variation in the money’s worth ratio (MWR) of the life annuity with respect to the 5-year payout to study the impact of the annuity price on the decision to annuitize. In the preferred specification, a one percentage point increase in the net MWR of the life annuity is associated with a 0.96 percentage point decrease in the demand for the 5-year payout. The negative tax effect on the expected present discounted value of the fixed-term payouts is particularly large for high-income individuals with large capital stocks. This could explain why demand for the 5-year payout is so low among this group. Demand for the 5-year payout is also low among retirees whose total retirement income exceeds the state income tax threshold only under the 5-year payout. This suggests that individuals evaluate the benefit’s net-of-tax value for different payout lengths, rather than it’s gross value, at least when the tax effect is large and salient.

High demand for the life annuity may also be driven by the fact that individuals are defaulted into annuitization if they take no action before age 65. Someone who sticks with the default may do so because he or she interprets the default provision as implicit advice from the plan sponsor, or simply because he or she is too uninformed about or even unaware of the imminent payout decision. Future research should try to identify the causal effect of defaults on payout decisions. Existing evidence of the role of defaults is only suggestive and inconclusive.Footnote 40

Notes

With lump sums, individuals receive the entire value of the accumulated retirement as a single payment, whereas phased withdrawals allow individuals to agree on a schedule of period fixed or variable payments (Antolin 2008).

In DC schemes, an individual can buy survivor insurance, which means that the remaining pension capital will be paid out to his or her partner or children. The combination between a fixed-term payout and survivor insurance is sometimes referred to as a fixed-term annuity.

Annuitization rates in US DB pension plans that offer a lump sum are typically lower than this, ranging from 25 to 50 % (Mottola and Utkus 2007; Benartzi et al. 2011; Previtero 2014; Banerjee 2013). Similar results are found in Brown et al. (2015) who study an irrevocable choice between a more immediate and a more deferred payment stream in Croatia, where 30 % choose the deferred payment.

A detailed description of the Swedish pension system can be found in Hagen (2013).

The ceiling is currently at 7.5 income base amounts (IBA). This means that no pension rights are earned for the monthly wage portion that exceeds SEK 35 375 (1 USD = 6.5 SEK in 2013).

For example, the pension plan for blue-collar workers, SAF-LO, only allows for fixed-term withdrawals of pension wealth accumulated after 1996.

The first cohort to be affected by the new DC pension plan, called ITP1, is those born in 1979.

Benefits from ITP2 are calculated based on the pensionable wage \(w\), which, in effect, is the final wage. Pensionable wage also incorporates benefits in kind, compensation for regular shift work, time on call and standby time at the time of retirement. The replacement rate is higher for pre-retirement income that exceeds the income ceiling in the public pension system. The ITP2 benefit is calculated according to the following equation, where \(w_{i}\) denotes the wage portion related to IBA \(i\):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathrm{ITP2}=0.1w_{<7.5 \; \mathrm{IBA}}+0,65w_{7.5-20 \; \mathrm{IBA}}+0.325w_{20-30 \; \mathrm{IBA}} \end{aligned}$$For full ITP2, 30 whole entitlement years are required. An entitlement year can be earned from age 28 and is earned if the individual worked at least 20 % of full time. Earned ITP2 entitlement years are transferred to the new employer if the individual changes job.

There is also a DC component within the ITP plan called ITPK. Similar to ITP2, ITPK assets can be paid out during a fixed number of years or as a life annuity. This study focus on payout choices in the DB component for two reasons. First, ITPK is less important and normally amounts to 10 % of the final wage if t is paid out over five years. Second, the data only contains information on ITPK assets that were accumulated prior to 2008 (Ursprunglig ITPK).

In practice, retirees are allowed to withdraw their pension during any number of years with a minimum of 5 years. However, only 1 % choose some other payout length than the pre-specified fixed-term payout lengths (5, 10, 15 and 20 years) and the life annuity.

See Edmark et al. (2012) for a detailed description of the Swedish income tax system.

From 2009, the basic deduction for individuals aged 65 and above is higher than for those below this age. This implies that the thresholds in the state income tax schedule are somewhat lower for individuals below age 65. In 2013, the basic deduction for individuals aged 65 and above was phased in between SEK 45,000 and SEK 166,900 and phased out between SEK 212,300 and 538,700.

Davidoff et al. (2005) extend Yaari (1965) and show that individuals benefit from converting a significant fraction of their assets into life annuities even in the presence of incomplete markets for life annuities. Feigenbaum et al. (2013), on the other hand, show that the welfare effect of annuitization is ambiguous in general equilibrium on account of pecuniary externalities.

Pension wealth in occupational pension plans other than the ITP plan can be viewed as pre-annuitized wealth since these plans only allow limited amounts of DC capital to be withdrawn as fixed-term payouts for the cohorts studied in this paper.

When estimating the expected present discounted value of each payout option, I use gender-specific mortality tables published by Statistics Sweden for years 2009–2013. To account for the fact that payments of different payout length might be discounted at different rates, I use the mean yield on 5-year Treasury notes in year t-1 for the 5-year payout option and the mean yield on 10-year notes for the remaining payout options. The mean yield on 10-year Treasury notes in 2012 was 1.59 % compared to 1.12 % for 5-year notes.

As mentioned in Sect. 2.3, from 2009 and onwards, the basic deduction is higher for individuals aged 65 or above than for those below. The tax paid, \(T\), should therefore be a function of both \(t\) and \(a\). However, because almost 90 % claim at age 65, I simplify by making the tax function independent of age.

When calculating individual MWRs, I take into account the tax system of the relevant year, pension income from other occupational pension plans and private pension accounts, public pension benefits, gender and the age at retirement. To simplify, I assume zero labor earnings after claiming.

Kopczuk and Lupton (2007) show that children are an imperfect proxy of bequest motives. An alternative proxy of bequest motives is the purchase of life or survivor insurance (Bernheim 1992). Survivor insurance in the ITP plan is optional. Unfortunately, the data do not include information on whether the individual has purchased this insurance or not.

This corresponds to a monthly income of SEK 7 400 or 30 % of the average permanent income. This measure also includes self-employment income.

12, 18 and 38 % receive income from the occupational pension plan for central government workers, local government workers and blue-collar workers in the private sector, respectively. As many as 82 % receive pension income that is not classified by LISA as coming from any of the four major occupational pension plans (variable “OvrTjp”).

Remember that the sample is restricted to retirees who claimed ITP benefits before 2011 when we look at non-ITP income sources (N \(=\) 82,066). The public pension claiming age is not observed for about 5 % which means that the true average claiming age might be somewhat higher than 64.2.

Includes co-habiting partners.

An employee that calls in sick receives sick pay from the employer the first 14 days of absence. After 14 days, the employer reports the case to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan), who pays out a sickness benefit that amounts to about 80 % of the individual’s salary. The data in this study contain information on the number of days individuals receive sickness benefits from Försäkringskassan.

Complete cohort-specific mortality tables are available for cohorts born in 1910 or earlier (SCB 2010).

Various definitions of parent longevity are possible. I also create dummies for whether both (and any) of the parents are deceased/alive at age 65/90. The results turn out to be robust to these definitions.

Specifically, the account balance distribution refers to the monetary value of the pension payment under the life annuity. For each individual, I observe the monthly benefit under the preferred payout option. The monetary value of the life annuity is calculated as the product of the given benefit and the relevant conversion factor. For example, if the monthly benefit under the 5-year payout is SEK 2000 and the (hypothetical) conversion factor is 3.5, the value of the life annuity is equal to SEK 714.3 (\(2500\div 3.5=714.3 \)).

The demand for fixed-term payout options can also be estimated in an OLS framework. I estimate a logit model where the dependent variable equals one if individual \(i\) chooses fixed-term payout option \(k\) and zero otherwise. The OLS estimates turn out to be very similar in magnitude to the marginal effects from the multinomial logit regressions and the inferences are unchanged. I do not report the estimation results for the 20-year payout. The estimates are not informative because only 0.2 % choose this payout option.

All regression models restrict the sample to individuals for whom we know the date of birth of both biological parents. The results are similar when all individuals are included (excluding the variables of parent longevity from the model).

Finkelstein and Poterba (2004) apply a similar LPM model framework as well as a hazard model framework to study annuitant mortality in the UK annuity market.

Using the relative value of the 5-year payout to predict the demand for the 10- and 15-year payout is not ideal since there might be within-individual variation in the net MWR across payout options. The within-individual variation is too small to motivate the use of conditional logit or mixed logit models. Such models allow for the explanatory variables to include attributes of the choice alternatives, which in our case would be the payout-specific net MWRs.

As seen in Table 1, there is very limited variation in the net MWR across the income distribution. The relative value of the 5-year payout is therefore not a good proxy for the relative value of the 15-year payout.

Non-pension wealth is imperfectly proxied by permanent income if wealth is inherited, and ITP wealth might underestimate the overall wealth level of the individual if she is a member of multiple occupational pension plans.

OLS estimates from a linear probability model of ex-post mortality yield similar results.

Another way to isolate tax-induced variation in the net MWR is to use gender-independent mortality tables when calculating EPDVs according to Eq. 1. This yields similar marginal effects of \(-\)0.96.

Excluding the two retirement wealth variables from specification (1) yields a significant estimate of female of 0.035.

Summary statistics for these two groups are provided in the Online Appendix (Table A1). The online appendix also provides results from several predictions that are made to illustrate the findings in Table 5. Specifically, I use the coefficient estimates that underlie the marginal probability effects to predict probabilities of choosing each payout option for individuals with different attributes.

References

Agnew, J. R., Anderson, L. R., Gerlach, J. R., & Szykman L. R. (2008). Who chooses annuities? An experimental investigation of the role of gender, framing, and defaults. The American Economic Review, 98(2), 418–422.

Ameriks, J., Caplin, A., Laufer, S., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2011). The joy of giving or assisted living? Using strategic surveys to separate public care aversion from bequest motives. The Journal of Finance, 66(2), 519–561.

Antolin, P. (2008). Policy options for the payout phase. In OECD Working Papers on Insurance and Private Pensions No.25.

Banerjee, S. (2013). Annuity and lump-sum decisions in defined benefit plans: The role of plan rules. EBRI Issue Brief, p. 381.

Barr, N., & Diamond, P. (2008). Reforming pensions: Principles and policy choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benartzi, S., Previtero, A., & Thaler, R. H. (2011). Annuitization puzzles. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), 143–164.

Bernheim, B. D. (1992). How strong are bequest motives? Evidence based on estimates of the demand for life insurance and annuities. Journal of Political Economy, 99, 899–927.

Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. C. (2011). Behavioral economics perspectives on public sector pension plans. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10(02), 315–336.

Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Zeldes, S. P. (2014). What makes annuitization more appealing? Journal of Public Economics, 116, 2–16.

Brown, J. R. (2001). Private pensions, mortality risk, and the decision to annuitize. Journal of Public Economics, 82(1), 29–62.

Brown, J. R. (2007). Rational and behavioral perspectives on the role of annuities in retirement planning. NBER Working Paper 13537.

Brown, J. R., Ivković, Z., & Weisbenner, S. (2015). Empirical determinants of intertemporal choice. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(3), 473–486.

Brown, J. R., Kling, J. R., Mullainathan, S., & Wrobel, M. V. (2008). Why don’t people insure late-life consumption? A framing explanation of the under-annuitization puzzle. American Economic Review, 98(2), 304–309.

Brown, J. R., & Poterba, J. M. (2000). Joint life annuities and annuity demand by married couples. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 67(4), 527–553.

Bütler, M., K. Peijnenburg, & Staubli, S. (2011). How much do means-tested benefits reduce the demand for annuities? In CESifo working paper: Empirical and Theoretical Methods, No. 3493.

Bütler, M., Staubli, S., & Zito, M. G. (2013). How much does annuity demand react to a large price change? The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(3), 808–824.

Bütler, M., & Teppa, F. (2007). The choice between an annuity and a lump sum: Results from swiss pension funds. Journal of Public Economics, 91(10), 1944–1966.

Chalmers, J., & Reuter, J. (2012). How do retirees value life annuities? Evidence from public employees. Review of Financial Studies, 25(8), 2601–2634.

Davidoff, T., Brown, J. R., & Diamond, A. P. (2005). Annuities and individual welfare. American Economic Review, 95(5), 1573–1590.

Dushi, I., et al. (2004). Household annuitization decisions: Simulations and empirical analyses. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 3(2), 109–143.

Edmark, K., Liang, C.-Y., Mörk, E., & Selin, H. (2012). Evaluation of the swedish earned income tax credit. IFAU Working Paper 2012, p. 1.

Feigenbaum, J., Gahramanov, E., & Tang, X. (2013). Is it really good to annuitize? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 93, 116–140.

Finkelstein, A., & Poterba, J. (2002). Selection effects in the United Kingdom individual annuities market. The Economic Journal, 112(476), 28–50.