Abstract

The Student Career Construction Inventory measures students’ adapting behaviors. The present study validates this inventory in a sample of 314 Portuguese college students. Measurement confirmatory factorial analysis indicates better fit for the 18-items measurement model, comparing to the 25-items model. Reliability and criterion-related analyses evidence the inventory validity and use. Structural model path analysis shows significant relations between measures of adaptability, adapting behaviors, and vocational identity results. This indicates that self-regulatory resources may drive career decidedness. While further longitudinal studies are needed to test the inventory and model’s predictive validity, our results provide developments to the literature on career measurements.

Résumé

L'Inventaire de la Construction de la Carrière de l'Etudiant·e (SCCI) : validation auprès d'étudiantès universitaires portugaisès Le Student Career Construction Inventory mesure les comportements d'adaptation des étudiants. La présente étude valide cet inventaire auprès d'un échantillon de 314 étudiantès universitaires portugaisès. L'analyse factorielle confirmatoire de la mesure indique une meilleure adéquation pour le modèle de mesure à 18 items, par rapport au modèle à 25 items. Les analyses de fiabilité et de critères démontrent la validité et l'utilisation de l'inventaire. L'analyse en modélisation des équations structurelles montre des relations significatives entre les mesures de l'adaptabilité, les comportements d'adaptation et les résultats de l'identité professionnelle. Ceci indique que les ressources d'autorégulation peuvent conduire à la décision de carrière. Bien que d'autres études longitudinales soient nécessaires pour tester la validité prédictive de l'inventaire et du modèle, nos résultats apportent des développements à la littérature sur les mesures de la carrière.

Zusammenfasung

Das Student Career Construction Inventory: Validierung mit portugiesischen Universitätsstudierenden Das Student Career Construction Inventory misst das Anpassungsverhalten von Studierenden. In der vorliegenden Studie wird dieses Inventar an einer Stichprobe von 314 portugiesischen Studierenden validiert. Die konfirmatorische Faktorenanalyse zeigt, dass das Messmodell mit 18 Items besser geeignet ist als das Modell mit 25 Items. Reliabilitäts- und kriteriumsbezogene Analysen belegen die Validität und Verwendung des Inventars. Die strukturelle Pfadanalyse zeigt signifikante Beziehungen zwischen den Maßen der Anpassungsfähigkeit, dem Anpassungsverhalten und den Ergebnissen der beruflichen Identität. Dies deutet darauf hin, dass selbstregulierende Ressourcen die Laufbahn-Entscheidungssicherheit beeinflussen können. Obwohl weitere Längsschnittstudien erforderlich sind, um die prädiktive Validität des Inventars und des Modells zu testen, liefern unsere Ergebnisse neue Erkenntnisse bezüglich der Literatur über Laufbahnkonzepte

Resumen

El Inventario de Construcción de Carreras Estudiantiles: validación con estudiantes universitarios portugueses El Inventario de Construcción de Carreras Estudiantiles mide los comportamientos de adaptación de los estudiantes. El presente estudio valida este inventario en una muestra de 314 estudiantes universitarios portugueses. El análisis factorial confirmatorio de medición indica un mejor ajuste para el modelo de medición de 18 elementos, en comparación con el modelo de 25 elementos. La fiabilidad y los análisis relacionados con los criterios evidencian la validez y el uso del inventario. El análisis de la trayectoria del modelo estructural muestra relaciones significativas entre las medidas de adaptabilidad, los comportamientos de adaptación y los resultados de la identidad vocacional. Esto indica que los recursos de autorregulación pueden impulsar la decisión de carrera. Si bien se necesitan más estudios longitudinales para probar la validez predictiva del inventario y del modelo, nuestros resultados proporcionan información para el desarrollo de la literatura sobre mediciones de la carrera

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global markets and accelerated technological developments affect employment structure worldwide (e.g., Duarte et al., 2019; Hirschi, 2018; World Economic Forum, WEF, 2018). Hierarchical and long-term careers are now more competitive and flexible, increased by part-time and temporary jobs (e.g., Pabollet et al., 2019; Savickas, 2011; WEF, 2018). Job transitions are not only more frequent across the life span, but they are also harder (Hirschi, 2018; Hood & Creed, 2019). Furthermore, softer skills and competencies as creativity, problem-solving or communication are expected from individuals (e.g., Pabollet et al., 2019; Hood & Creed, 2019; WEF, 2018). The age of information requires lifelong learners, who can create their career opportunities and manage different life roles without losing their self-identity (e.g., Hirschi, 2018; Hood & Creed, 2019; Savickas, 2021; WEF, 2018). Efforts to help people manage their careers in a globalized and multicultural environment led to theoretical and practical advances in vocational psychology (Brown & Lent, 2013, 2021; Savickas, 2011). Currently, some of the most cited career frameworks include the social cognitive theory (SCCT; Lent & Brown, 2013; Lent et al., 1994), the psychology of working theory (PWT; Blustein, 2006; Blustein & Duffy, 2021), the career construction model (CCM; Savickas, 2013, 2021), and the protean and boundaryless career theory (Arthur, 2014; Hall, 2004).

CCM presents a dynamic and developmental perspective (Rudolph et al., 2019) addressing the current socio-economic scenario, which is useful to understand self-career management among university students. Specifically, this model considers interpersonal and interpretative processes, through which individuals make meaning of their careers and direct vocational behaviors to face career transitions (e.g., school-school, school-work, work-work, work-retirement) and/or traumas (e.g., involuntary unemployment) (Savickas, 2013, 2021). During higher education entry and adaptation phases, university students may face numerous challenges (e.g., heterogeneity, emotional, vocational, academic), as well as retention and exit (e.g., Carreira & Lopes, 2019; Mestan, 2016; Ricks & Warren, 2021). CCM posits that a better adaptation to academic challenges may be achieved by students’ career adaptivity, adaptability, adapting, and adaptation (Savickas, 2013, 2021; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Career adaptivity, the first component, refers to individuals’ personality traits of willingness to cope with career transitions and/or traumas. Career adaptability, the second component, refers to individuals’ career self-regulation competencies. Specifically, this component includes four psychosocial resources: concern (i.e., anticipating one’s future role as a worker); control (i.e., influencing the environment for personal goals achievement); curiosity (i.e., exploring future work scenarios and possible selves); and confidence (i.e., believe in one’s capabilities to pursue career and life aspirations). Career adapting, the third component, refers to individuals’ adaptative behaviors performed in response to environmental career challenges. These include behaviors like planning, exploring, deciding, skilling, transitions managing, among others (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2015; Lent & Brown, 2013). Career adaptation, the fourth component, defined as individuals' harmony between inner and outer needs, emerges as a result of career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting. In other words, students with flexibility and willingness to change (adaptivity), equipped with resources to cope with career transitions or traumas (adaptability), will adopt more career behaviors (adapting), which foster career adaptive results of success, satisfaction, and development (Savickas, 2013, 2021; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Indeed, studies among university students evaluating the relation between model components confirm this sequence of adaptivity, adaptability, adapting, and adaptation (e.g., Nilforooshan, 2020; Soares et al., 2021; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). For example, Yıldız-Akyol and Öztemel (2021), concluded that prior academic success increases university students’ adaptability, motivating adaptative behaviors which resulted in greater feelings of academic satisfaction. Moreover, studies indicate direct and positive relations between adaptability and adaptation (e.g., Holliman et al., 2018; Merino-Tejedor et al., 2016; Soares et al., 2021; Wilkins-Yel et al., 2018), as well as the mediation role of adaptability and adapting between adaptivity and adaptation (e.g., Nilforooshan, 2020; Soares et al., 2021; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). Recalling Yıldız-Akyol and Öztemel’s (2021) studies, this means that prior academic success may increase students’ academic satisfaction depending on their adaptability and adaptive behaviors.

Across literature, each dimension of CCM has been evaluated by different measures (e.g., Johnston, 2018; Rudolph et al., 2017a, b). For example, adaptivity includes measures of personality, core-self evaluations or cognitive abilities (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2015; Šverko & Babarović, 2019; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). The same happens with career behaviors, usually measured by career planning, career decision-making self-efficacy or difficulties (e.g., Babarović & Šverko, 2016; Hirschi et al., 2015; Johnston, 2018; Karacan-Ozdemir, 2019; Šverko & Babarović, 2019). To address this topic in more detail, we recommend reading Rudolph and collaborators' metanalysis (Rudolph et al., 2017a, b). Despite the reliability between these measures and CCM-dimensions’ definition, heterogeneity makes studies’ comparison difficult. Therefore, the career adaptability research team developed two measures. First, they designed a measure to evaluate career adaptability, comprising 24 items distributed by four psychosocial resources (i.e., concern, curiosity, confidence and control). This measure was initially validated and published in an international study with 13 countries, proving the measure’s composite structure (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Second, the team developed a measure to evaluate career adaptive behaviors and thoughts, the student career construction inventory (SCCI). However, only recently the authors published the inventory validation research among high school and university students (Savickas et al., 2018).

The SCCI was designed as a specific measure to access career-adaptative behaviors of students’ exploratory phase (Savickas et al., 2018). This phase includes behaviors as self and occupations exploration, transition managing, career decision-making, skilling, or the formulation of specific goals and plans grounded on a clearer self-concept (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2015; Lent & Brown, 2013; Nilforooshan, 2020). As a result, the initial form of SCCI included 25 items distributed by five factors (i.e., crystallizing vocational self-concept, exploring occupations, deciding on an occupational choice, skilling or instrumentation to get relevant training, and transitioning from school to work), representing these typical behaviors of career exploratory phase. Nevertheless, exploratory factor analysis conducted by Savickas et al. (2018), on high school and college students, indicated the need to exclude items and reduce factors number to four. Specifically, the authors excluded one item from crystallizing, four from exploring, one from skilling, and another from transitioning. Regarding these last two factors, exploratory factor analysis also indicated items saturation on a single factor. In other words, the items referring to skilling and transitioning merged to form a single factor representing prior qualification work for entry into the desired job. Hence, SCCI final form included 18 items distributed by four factors (i.e., crystallizing vocational self-concept, exploring occupations, deciding on an occupational choice, and preparing to implement that choice), presenting good fit indices (CFI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.065, SRMR = 0.045) and reliability (0.84 < \(\alpha\) < 0.94) among high school, undergraduate and graduate students (Savickas et al., 2018).

To our knowledge, this 18-item form is only validated for Turkish high school (Öztemel & Akyol, 2020) and university students (Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021), also presenting good psychometric properties. For example, Yıldız-Akyol and Öztemel (2021) indicated good fit indices for first (CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.064, SRMR = 0.054) and second (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.066, SRMR = 0.058) order models, as well as, good reliability (0.68 < \(\alpha\) < 0.89). Nevertheless, other countries still seem to use the 25-item form. Possibly due to the newness of Savickas and collaborators’ validation study. This can be seen, for example, in studies among Croatian teenagers (Babarović & Šverko, 2016; Šverko & Babarović, 2019) and Portuguese university students (Rocha & Guimarães, 2012). Overall, this longer form also presents good fit indexes (e.g., second order model with CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, Rocha & Guimarães, 2012) and reliability (e.g., 0.73 < \(\alpha\) < 0.89, Rocha & Guimarães, 2012). As a result of the new evidence presented by Savickas et al. (2018), and the inconsistency of SCCI-form used among different countries, more studies are needed. First, to compare, in the same context, the fit of 25 and 18-items forms. Considering the advantages of the latter in long protocols. Secondly, to provide an alternative for cross-cultural studies. Specifically, when one of the contexts shows good psychometric qualities for only one of the SCCI-forms or has only one of them validated.

Therefore, our study aims to reanalyze SCCI psychometric properties, comparing the 25-item model with the 18-item model in a sample of Portuguese university students. We expect to obtain (H1) good fit and (H2) good reliability indices for both models. Moreover, in line with the original study (Savickas et al., 2018), we will evaluate concurrent validity with a measure of adaptability (i.e., career adapt-ability scale) and another of adaptation (i.e., vocational identity scale). The latter focused on assessing the degree of vocational certainty. Specifically, it focuses on the extent to which participants have clear and stable picture of their goals, interests, personality, and strengths, to make career decisions (e.g., Holland et al., 1980; Santos, 2010). These are highly required tasks across university years (e.g., “Which course to choose?”, “What I need to do to achieve my aspirations?”) (e.g., Álvarez-Pérez & López-Aguilar, 2020), and therefore a reason to include vocational identity as main adaptation result in our study. The CCM model will also be partially tested with the SCCI as a measure of adapting responses. We considered the adaptation dimensions of adaptability, adaptative behaviors, and adapting results. Actually, the literature has shown that adaptability is a stronger predictor than adaptivity, in predicting adapting results (e.g., Merino-Tejedor et al., 2016; Öztemel & Akyol, 2020; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). Furthermore, in some cases, it appears that the adaptivity-adapting relation is either not found or only occurs through adaptability (e.g., Merino-Tejedor et al., 2016; Nilforooshan, 2020; Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015). These are congruent with theoretical assumptions stating “the psychological trait of adaptiveness by itself is insufficient to support adaptive behaviors” (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012, p. 662). This empirical evidence, tandem with the need to be parsimonious in the protocol and model for analysis, supported our choice to perform a first SCCI evaluation, on the CCM model, without adaptivity. We expect (H3) positive and significant relations between SCCI-adaptability and SCCI-adaptation, supporting both SCCI and (H4) CCM validity (Savickas et al., 2018).

Method

Participants and procedure

A consent for the Portuguese adaptation of SCCI was obtained from the original authors (Savickas et al., 2018). One psychology researcher, a Portuguese native speaker familiarized with the inventory, did the translation. This was followed by a review of an independent researcher. After consensus, a back translation was performed by a Portuguese-English bilingual, external to the study and trained in English language. Afterwards, the research protocol was elaborated on SPSS Data Collection. At the beginning of the research protocol, we presented the study’s aim and guaranteed data confidentially and anonymity. The participants’ recruitment took place from November 2020 to February 2021. A two-step data collection was performed. Firstly, we emailed Portuguese students’ associations and personal contacts to fill in the protocol. Second, we emailed the same Portuguese students’ associations offering a free webinar on self-career management. This webinar began with an invitation to fill in the protocol and, only afterwards, the self-career management presentation took place. At the end of this webinar, the participants received a certificate. Across the data-collection procedure, the participants responded to all items.

Three hundred and fourteen Portuguese university students, whose estimated response time was 10 min, voluntarily responded to the entire protocol. The sample included 260 (82.8%) women and 53 (16.9%) men, aged 17 to 47 (M = 21.5, SD = 4.32), 301 (95.9%) identified as Caucasians, three (1%) as Black, and 10 (3.2%) as another ethnicity. The majority (n = 234, 74.5%) attended university educational institutions. Only 80 (25.5%) attended polytechnic institutions. Together, these polytechnic and university educational institutions represent regions from the North to South of Portugal, including Azores. The students were enrolled in the following courses: 97 (30.9%) in Health and Welfare, 96 (30.6%) in Social Sciences, Journalism and Information, 50 (15.9%) in Natural Sciences, Mathematics and Statistics, 26 (8.3%) in Engineering, Manufacturing and Construction, 16 (5.1%) in Arts and Humanities, 11 (3.5%) in Education, 8 (2.5%) in Business, Administration and Law, 8 (2.5%) in Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Veterinary, and 1 (0.3%) in Information and Communication Technologies (educational field categories defined by UNESCO, 2015). At the time of the data collection, 44 (14%) students were studying and working, of which only 21 (6.7%) had student worker status.

Measures

Adaptability

Adaptability resources were accessed with the Career Adapt-Ability Scale (CAAS, Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), adapted for Portugal by Monteiro and Almeida (2015). This measure comprises 24 items divided by four dimensions, six items each. Concern about future options (e.g., “Preparing for the future”), control over one’s possible future (e.g., “Keeping upbeat”), curiosity about possible selves and future scenarios (e.g., “Exploring my surroundings”), and confidence on one’s career path (e.g., “Solving problems”). The participants responded in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not strong) to 5 (very strong). Monteiro anfd Almeida (2015) found good reliability indices (0.78 < \(\alpha\) < 0.92). The same applies for the present sample (0.81 < \(\alpha\) < 0.93).

Adapting

Adaptive behaviors were accessed with the SCCI (Savickas et al., 2018) 25-items’ version (see Appendix A in Table 4). Some sample items include “Knowing how other people view me” and “Reading about occupations”. From a 25-model structure, Savickas et al. (2018) eliminated items seven, eight, nine, 13, 14, 20 and 24, resulting in an 18-item version. The response is given in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (I have not yet thought much about it) to 5 (I have already done this). Savickas et al. (2018) found good reliability indices both among graduate (0.76 < \(\alpha\) < 0.89) and undergraduate (0.79 < \(\alpha\) < 0.91) students.

Adaptation

Adaptation results were accessed with the Vocational Identity Scale (VIS, Holland et al., 1980) adapted for Portugal by Santos (2010). It includes 18 items (e.g., “I feel uncertain about what professions I could do well”) answered in a true or false scale. The participants evaluated if they have a clear and stable picture of their talents, interests and goals. In a sample of university students, Santos (2010) found a good reliability index (\(\alpha\) = 0.79). The same applies for the present sample (\(\alpha\) = 0.85).

Results

Part I: psychometric analyses of the SCCI

Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis for the SCCI measurement model evaluation was run in AMOS 27 for Windows. In line with theoretical framework (e.g., Babarović & Šverko, 2016; Rocha & Guimarães, 2012; Savickas et al., 2018), we first evaluated the 25-items’ structure. Two measurement models were specified. Model 1 followed a five-factor structure, assuming 25 observable variables and five correlated latent variables. Model 2 considered a hierarchical structure, assuming 25 observable variables, five first-order, and one second-order latent variable which represents career adaptive responses. Later, we evaluated the 18-items structure, also specifying two measurement models. Model 1 followed a four-factor structure with 18 observable variables and four correlated latent variables. Model 2 considered a hierarchical structure with 18 observable variables, four first-order and one second-order latent variables.

Assumptions of linearity, normality, absence of multicollinearity, and outliers were verified (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). As evidence of Multivariate non-normality evaluated through Mardia’s coefficient, we performed a bootstrap analysis with 500 samples (Gilson et al., 2013). Given the existence of 13 outliers identified through Mahalanobis’ Distance, we ran analyses with (N = 314) and without (N = 301) these extreme observations to control possible biases (Pinto et al., 2013). Due to goodness-of-fit variability between results with and without outliers, we used the results without outliers.

Results for the specified measurement models are presented in Table 1. Overall, indices indicated an acceptable measurement-fit for the 18-items models (\(\chi\)2/df lower than three, CFI above 0.90, RMSEA below 0.08, and SRMR below 0.10) (Hair et al., 2010; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Both 18-items correlational model (\(\chi\)2/df = 2.653; CFI = 0.927; SRMR = 0.062; RMSEA = 0.074) and 18-items hierarchical model (\(\chi\)2/df = 2.899; CFI = 0.917; SRMR = 0.065; RMSEA = 0.080) showed acceptable fit. Regarding the 25-items’ models CFI indices indicated a close to acceptable fit. Moreover, AIC values from 25-items and 18-items models support a better fit for the latter (i.e., lower AIC values indicate a better fit, Oliveira et al., 2018). Therefore, we used the 18-items form for further analysis.

SCCI internal consistency and scale inter-correlations

Table 2 presents SCCI reliability, descriptive analysis and inter-correlations. Coefficient alphas were greater than 0.70, both for the total score and for dimension, indicating good reliability of SCCI (Nunnally, 1970). The correlation magnitudes between each dimension and the total score were strong (r > 0.50, Cohen, 1988). Moreover, the inter-correlations magnitudes among SCCI four dimensions ranged from moderate (0.30 < r < 0.50) to strong (Cohen, 1988), being the correlation between deciding and preparing the highest (r = 0.75).

SCCI criterion-related validity

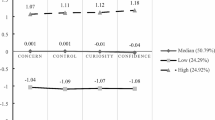

Correlations between adaptability (CAAS), adapting (SCCI), and adaptation (VIS) total scores (Table 3) were both positive and significant, ranging from moderate [r (adaptation-adapting) = 0.37] to strong [r (adaptability-adapting) = 0.65]. The same happened between adaptability total score and adapting dimensions (0.46 < r < 0.58).

Correlations between crystallizing-adaptation total score and exploring-adaptation total score, presented weak Pearson values (r < 0.30, Cohen, 1988). Meanwhile, adaptation total score highest correlation was with deciding dimension (r = 0.41), which represents a moderate correlation (0.30 < r < 0.50, Cohen, 1998). These results give us confidence to evaluate SCCI in the context of the structural career adaptation model, according to what Savickas et al. (2018) performed.

Part II: test for the career adaptation model using SCCI

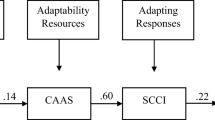

Figure 1 portrays a CCM test among the initial 314 Portuguese university students, as non-evidence of outliers through Mahalanobis’ Distance (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). After the accomplishment of structural-equation-modeling assumptions (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), direct relations were evaluated between adaptability resources, adapting responses and adaptation results. One regression weight was fixed to 1 (Lent et al., 2008).

Path analysis indicated adequate fit values for CFI = 0.914 and SRMR = 0.061, which is sufficient to assume a structural model adequate fit (CFI above 0.90 and SRMR below 0.10, Hu & Bentler, 1999). However, when analyzing modification indices, AMOS suggested an additional direct path between adaptability resources and adaptation results. The final model is presented in Fig. 1. Fit indices indicated an improvement of model-data adjustment (CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.019). Indices indicate a good structural model fit (CFI above 0.95 and SRMR below 0.05, Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate SCCI psychometric properties among Portuguese university students. A model of 25 observable variables and another with 18 observable variables were considered and compared, following Savickas et al. (2018) methodology.

Confirmatory factor analysis indicates an adequate fit, both for first- and second-order measurement models of 18-items form. Previous studies in Turkish and American contexts also support this evidence (Savickas et al., 2018; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). Concerning the 25-items’ model, we found adequate fit indices except for the CFI. This contrasts with the previous study from Rocha and Guimarães (2012) in a sample of Portuguese university students. These authors found general good fit indices, both for first and second-order SCCI measurement models. Our results partially support H1. Therefore, although the general criteria have been met, both for the 18-item and 25-item forms, we recommend using the former. Its reduced size will be an advantage for studies with long protocols and counseling contexts when clients are less motivated for the process. If the aim is to access adapting specific behaviors, we recommend the use of correlational model where these behaviors are detailed. In contrast, if the aim is to assess the general level of adapting behaviors development, the hierarchical model should be chosen.

Although SCCI measures a single general factor corresponding to students’ career exploration stage (Savickas et al., 2018), we highlight the adequate fit indices found in our heterogeneous sample ranging from 17 to 47 years old. Rocha and Guimarães (2012) also found good fit indices for the 25-item structure analyzed, as well as no differences between young (17–22 years) and mature (above 23 years) students, regarding their career-adaptive behaviors. Therefore, we may conclude that the SCCI may be applied to a broader age range. This is advantageous and may be justified by today's information era, as even people at later developmental stages (e.g., establishment) need to continue to explore and learn (e.g., Hirschi, 2018; Savickas, 2011, 2021; WEF, 2018). Future studies on SCCI psychometric properties, considering both 25-items and 18-items’ models among individuals from different life stages, (e.g., high school students, employed adults, unemployed) are needed to evaluate the inventory’s applicability and invariance.

Results of internal consistency indicate a good reliability index, as expected (H2). Previous research among American and Turkish university students also supports this evidence (Savickas et al., 2018; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021), which gives us the confidence to use SCCI as a measure to evaluate adaptive career behaviors. Moreover, inter-correlations’ result among SCCI dimensions and between SCCI total score indicate that each inventory dimension accesses a single-specific career task.

As for criterion-related validity, our results agree with Savickas et al. (2018) supporting H3. Correlations’ magnitudes between adaptability, adapting, and adaptation total scores, indicate that the SCCI assesses behaviors instead of psychosocial resources or vocational identity. In addition, correlation results between adaptability-deciding and adaptation-deciding support Savickas et al.’s (2018) statement regarding CAAS as a measure of decision-making resources, and VIS as a measure of decidedness.

Turning to the tenability of CCM, results of confirmatory factor analysis indicate structural models’ good fit. Path analysis indicates positive and significant relations between the specified variables, as expected (H4). In other words, our findings indicate that Portuguese university students with self-regulatory resources (i.e., concern, curiosity, control, confidence) will more easily engage in adaptive career behavior and thoughts (i.e., exploring, planning, deciding, crystallizing). As a result, they will present a clearer and stable picture of their talents, interests and goals, which relates with greater decidedness concerning their future career path. This finding supports CCM prepositions about self-construction. According to this theory, it is expected that during university years, youngers can function in an integrated way, constructing autobiographical stories (Savickas, 2021). Therefore, these direct relations may indicate that self-regulatory processes, developed during childhood and adolescence, now contribute to career self-management in tandem with life narrative construction. In other words, youngers behaving as motivated agents (i.e., people who explore, plan and make decisions, managing their careers) begin to establish a clear and stable image about their career aspirations and goals, which allows them to be more intentional when giving meaning to their actions, hence, constructing a congruent life story.

In addition to this finding, students’ self-regulatory resources seem directly contributing to career decidedness. Across the literature, other studies also found this relation between adaptability and adaptation. For example, adaptability seems to explain more academic engagement (Holliman et al., 2018; Merino-Tejedor et al., 2016), academic satisfaction (Wilkins-Yel et al., 2018), and perceived employability (Soares et al., 2021). As a result, we may argue that career adaptability is a prerequisite to achieve adaptation results of career success, satisfaction, and development. This occurs probably because adaptability encourages the adoption of adaptive behaviors, indirectly contributing to career adaptation results. Indeed, two recent studies with university students presented evidence that support this explanation (Nilforooshan, 2020; Yıldız-Akyol & Öztemel, 2021). Nilforooshan (2020) concluded that adaptability explained students’ academic satisfaction through engagement behaviors and career decision-making self-efficacy. Yıldız-Akyol and Öztemel (2021) concluded that adaptability explains students’ academic satisfaction through exploration, planning, deciding, and preparation behaviors. In agreement with our findings regarding CCM, we outstand the need for developing career adaptive resources and behaviors among university students. These will provide students with the flexibility to face the volatility of the current social and work environments. As an evaluation of career intervention’s outcomes, besides CAAS as a measure of self-regulatory resources (Monteiro & Almeida, 2015; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), Portuguese counselors may now use SCCI to evaluate the individuals’ level of engagement in general and specific adaptive responses (Savickas et al., 2018).

Aware of present study limitations, we recommend caution when interpreting the results. In particular, we performed a cross-sectional study to test a causal model, the CCM. In line with our study aim, structural model fit evidence provides preliminary data supporting SCCI validity in accessing CCM adaptive responses. However, future research with a longitudinal design will be relevant. This will allow a holistic perspective on the career adaptation process. In particular, cross-sectional data provides information about individual response to a limited-period career trauma or task (e.g., entrance to higher education) attending CCM differential perspective (Rudolph et al., 2019). Longitudinal data incorporates career progression and dynamic processes that may change personal life narratives (e.g., Savickas, 2013, 2021). To motivate this research design, we recommend further psychometric scrutiny regarding SCCI predictive validity. Moreover, given the goal of our study to evaluate SCCI psychometric properties, we do not include the adaptivity dimension for economic reasons. Future studies concerned with CCM validation should consider a complete view, including this internal willingness to change.

Conclusion

In sum, our findings support SCCI use among Portuguese university students. Considering the adjustment indices found, we recommend the use of 18-items forms. Moreover, this briefer measure is advantageous in long protocols. While further studies are needed, our results also provide additional evidence that supports the career construction model.

In short, we hope to encourage further worldwide studies and practices with the measure, namely among Portuguese-speaking countries (e.g., Brazil, Angola, Guinea-Bissau). As stated by Savickas et al. (2018) SCCI is useful both for research and counseling purposes. Therefore, it is already possible to foster adaptive career behaviors among university students, evaluating this intervention’s effectiveness.

References

Álvarez-Pérez, P.-R., & López-Aguilar, D. (2020). Competencias de adaptabilidad y factores de éxito académico del alumnado universitario [Adaptability competencies and academic success factors of university students]. Revista Iberoamericana De Educación Superior, 11(32), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2020.32.815

Arthur, M. B. (2014). The boundaryless career at 20: Where do we stand, and where can we go? Career Development International, 19(6), 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-05-2014-0068

Babarović, T., & Šverko, I. (2016). Vocational development in adolescence: Career construction career decision-making difficulties and career adaptability of criatian high school students. Primenjena Psihologija, 9(4), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.19090/pp.2016.4.429-448

Blustein, D. L. (2006). The psychology of working: A new perspective for career development, counseling, and public policy. Erlbaum.

Blustein, D. L., & Duffy, R. D. (2021). Psychology of working theory. In S. Brown & R. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Brown, S., & Lent, R. (2013). Career development and counseling putting theory and research to work (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Brown, S., & Lent, R. (2021). Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (7th ed.). Wiley.

Carreira, P., & Lopes, A. S. (2019). Drivers of academic pathways in higher education: traditional vs. non-traditional students. Studies in Higher Education, 4, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1675621

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Duarte, J. B., Brinca, P., Gouveia-de-Oliveira, J., & Ferreira, A. M. (2019). O Futuro do Trabalho em Portugal: O Imperativo da Requalificacao [The Future of Work in Portugal: The Requalification Imperative]. https://doi.org/10.12660/gvexec.v7n5.2008.34249

Gilson, K., Bryant, C., Bei, B., Komiti, A., Jackson, H., & Judd, F. (2013). Validation ofthe Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) in older adults. Addictive Behaviors, 38, 2196–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.021

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. A global perspective (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006

Hirschi, A. (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Issues and implications for career research and practice. Career Development Quarterly, 66(3), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12142

Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., & Keller, A. C. (2015). Career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual and empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.008

Holland, J. J., Gottfredson, D. C., & Power, P. G. (1980). Some diagnostic scales for research in decision making and personality: Identity, information, and barriers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077731

Holliman, A. J., Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2018). Adaptability, engagement, and degree completion: A longitudinal investigation of university students. Educational Psychology, 38(6), 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1426835

Hood, M., & Creed, P. (2019). Globalisation: Implications for careers and career guidance. In J. Athanasou & H. Perera (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (2nd ed., pp. 477–497). Springer Nature.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Johnston, C. S. (2018). A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716679921

Karacan-Ozdemir, N. (2019). Associations between career adaptability and career decision-making difficulties among Turkish high school students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19(3), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09389-0

Lent, R., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying scct and academic interest, choice and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79–122.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033446

Lent, R. W., Lopez, A. M., Lopez, F. G., & Sheu, H. B. (2008). Social cognitive career theory and the prediction of interests and choice goals in the computing disciplines. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.002

Merino-Tejedor, E., Hontangas, P. M., & Boada-Grau, J. (2016). Career adaptability and its relation to self-regulation, career construction, and academic engagement among Spanish university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.01.005

Mestan, K. (2016). Why students drop out of the Bachelor of Arts. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(5), 983–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1139548

Monteiro, S., & Almeida, L. S. (2015). The relation of career adaptability to work experience, extracurricular activities, and work transition in Portuguese graduate students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.006

Nilforooshan, P. (2020). From adaptivity to adaptation: examining the career construction model of adaptation. Career Development Quarterly, 68(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12216

Nunnally, J. C. (1970). Introduction to psychological measurement. McGraw-Hill.

Oliveira, I. M., Taveira, M. C., Porfeli, E. J., & Grace, R. C. (2018). Confirmatory study of the multidimensional scales of perceived self-efficacy with children. Universitas Psychologica, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy17-4.csms

Öztemel, K., & Akyol, E. (2020). From adaptive readiness to adaptation results: Implementation of student career construction inventory and testing the career construction model of adaptation. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720930664

Pabollet, E. A., Bacigalupo, M., Biagi, F., Giraldez, M. C., Caena, F., Munoz, J. C., Mediavilla, C. C., Edwards, J., Macias, E. F., Gutierrez, E. G., Herrera, E. G., Santos, A. I., Kampylis, P., Klenert, D., Cobo, L., Marschinski, R., Pesole, A., Punie, Y., Tolan, S., … Vuorikari, R. (2019). The changing nature of work and skills in the digital age. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/679150

Pinto, J. C., do Taveira, M. C., Candeias, A., & Araújo, A. (2013). Análise fatorial confirmatória da prova de avaliação de competência social face à carreira [Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Perceived Social Competence Scale]. Psicologia, 26(3), 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-79722013000300006

Ricks, J. R., & Warren, J. M. (2021). Transitioning to college: Experiences of successful first-generation college students. Journal of Educational Research & Practice, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2021.11.1.01

Rocha, M., & Guimarães, M. I. (2012). Adaptation and psychometric properties of the student career construction inventory for a Portuguese sample: Formative and reflective constructs. Psychological Reports, 111, 845–869. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.10.11.PR0.111.6.845-869

Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., Katz, I. M., & Zacher, H. (2017a). Linking dimensions of career adaptability to adaptation results: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102(June), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.06.003

Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017b). Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.09.002

Rudolph, C. W., Zacher, H., & Hirschi, A. (2019). Empirical developments in career construction theory. [Editorial]. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 111, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.003

Santos, P. J. (2010). Adaptação e validação de uma versão portuguesa da Vocational Identity Scale [Adaptation, and validation of a portuguese version of the vocational]. Revista Galego-Portuguesa De Psicoloxía e Educación, 18(1), 147–162.

Savickas, M. L. (2011). New questions for vocational psychology: Premises, paradigms, and practices. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710395532

Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 147–183).Wiley.

Savickas, M. L. (2021). Career construction theory and counseling model. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (3rd ed., pp. 486–565). Wiley.

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

Savickas, M. L., Porfeli, E. J., Hilton, T. L., & Savickas, S. (2018). The student career construction inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106(2), 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.009

Soares, J., Taveira, M. C., Oliveira, M. C., Oliveira, I. M., & Melo-Silva, L. L. (2021). Factors influencing adaptation from university to employment in Portugal and Brazil. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-020-09450-3

Sverko, I., & Babarović, T. (2019). Applying career construction model of adaptation to career transition in adolescence: A two-study paper. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 111, 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.011

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson Education Inc.

Taber, B., & Blankemeyer, M. (2015). Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.005

UNESCO. (2015). International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): Fields of Education and Training 2013. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Wilkins-Yel, K. G., Roach, C. M. L., Tracey, T. J. G., & Yel, N. (2018). The effects of career adaptability on intended academic persistence: The mediating role of academic satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.006

World Economic Forum. (2018). The Future of Jobs Report 2018. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf

Yıldız-Akyol, E., & Öztemel, K. (2021). Implementation of career construction model of adaptation with Turkish University students: A two-study paper. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01482-4

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Mark L. Savickas permission to use the Student Career Construction Inventory

Funding

This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi/UM) School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (UIDB/01662/2020). This study was funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education, under the doctoral scholarship program (scholarship reference: 2020.06006.BD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 4

.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soares, J., Céu Taveira, M., Cardoso, P. et al. The student career construction inventory: validation with Portuguese university students. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 24, 223–239 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09553-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09553-z