Abstract

Using the Psychology of Working Theory as a guide, the goal of this study was to examine the longitudinal relations of economic deprivation to work volition and work volition to academic satisfaction among college students. We sampled 1508 students and surveyed them at three time points over a 6-month period. We found that economic deprivation partially predicted work volition over time, and work volition consistently predicted academic satisfaction over time. These results have theoretical implications as well as relevance to personnel working with economically marginalized college students.

Résumé

Relations longitudinales entre la précarité économique, la volition professionnelle et la satisfaction académique sous la perspective de la psychologie de l’activité de travail En utilisant la psychologie de l’activité de travail comme guide, l’objectif de cette étude était d’examiner les relations longitudinales entre la précarité économique et la volition professionnelle, et entre cette dernière et la satisfaction académique dans une population d’étudiant.e.s universitaires. Nous avons échantillonné 1508 étudiant.e.s et les avons interrogés à trois reprises sur une période de six mois. Nous avons constaté que la précarité économique prédisait partiellement la volition professionnelle au fil du temps, et que cette dernière prédit systématiquement la satisfaction académique des étudiant.e.s au fil du temps. Ces résultats ont des implications théoriques ainsi que de la pertinence pour la pratique des personnes travaillant avec des étudiant.e.s économiquement marginalisé.e.s.

Zusammenfassung

Beziehungen zwischen wirtschaftlicher Deprivation, Arbeitsvolition und akademischer Zufriedenheit: Eine Psychologie der Arbeitsperspektive Ziel dieser Studie war es, mit Bezug zur Arbeitspsychologie das Verhältnis von wirtschaftlichen Schwierigkeiten zur Arbeitsvolition und zur akademischen Zufriedenheit der Studenten zu untersuchen. Wir haben 1508 Studierende einbezogen und über einen Zeitraum von sechs Monaten zu drei Zeitpunkten befragt. Wir stellten fest, dass die wirtschaftliche Deprivation die Arbeitsbereitschaft über die Zeit teilweise beeinflusst und dass diese die Arbeitszufriedenheit über die Zeit konsistent prognostiziert. Diese Ergebnisse haben theoretische Implikationen sowie Relevanz für das Personal, das mit wirtschaftlich marginalisierten Studenten zusammenarbeitet.

Resumen

Relaciones longitudinales entre deprivación económica, iniciativa laboral y satisfación académica. Una perspectiva de trabajo psicológica Utilizando la teoria de la psicología del trabajo como guia, el objetivo de este estudio fué examinar las relaciones longitudinales entre deprivación económica, iniciativa laboral y satisfación académica entre estudiantes de College. Con una muestra de 1508 estudiantes se encuestaron en tres momentos en un periodo de seis meses. Se halló que la deprivación económica predijo parcialmente la voluntad laboral a lo largo del tiempo y dicha voluntad predijo consistentemente la satisfacción a lo largo del tiempo. Estos resultados tienen implicaciones teóricas además de relevancia para el personal que trabaja con estudiantes de college económicamente marginalizados.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholars within vocational and educational psychology have long been interested in understanding the predictors and outcomes of academic satisfaction in college students. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that feeling satisfied in college is a robust predictor of retention (Roberts & Styron, 2010), making satisfaction a key variable of interest for university leadership (Schertzer & Schertzer, 2004), especially as it relates to the retention of underrepresented students (e.g. first-generation college students, students with low socioeconomic status; Garriot, Hudyma, Keene, & Santiago, 2015). Dozens of studies have documented how social cognitive (e.g. self-efficacy, outcome expectations), personality (e.g. affect, conscientiousness), and goal-related variables predict feeling satisfied with one’s academic life, major, and coursework (e.g., Garriot et al., 2015; Lent, Singley, Sheu, Schmidt, & Schmidt, 2007; Lent, do Céu Taveira, Sheu, & Singley, 2009). However, to date, research on the relations of structural variables and students’ experiences of economic deprivation is much more limited. In particular, no studies have examined how these types of structural variables relate to academic satisfaction over time. This is a concerning gap in the literature considering the high percentage of low-income and first-generation students seeking college degrees, who continue to have less access to economic resources (e.g., Kochhar & Fry, 2014).

In the current study, we sought to address these limitations by examining the relations from economic deprivation to work volition and, in turn, to the academic satisfaction of a large group of college students, assessed at three time points over a six-month period. Economic deprivation refers to the lack of access to economic resources (Brief, Konovsky, Goodwin, & Link, 1995), and work volition is the perception of choice in one’s future career decision-making (Duffy, Diemer, & Jadidian, 2012). The PWT (Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, 2016) suggests that students’ ability to secure economic resources affects the ability to actively choose one’s work after graduation, which subsequently leads to poorer satisfaction in college. Overall, this study aimed to advance research on academic satisfaction by examining these theoretical hypotheses—namely that economic deprivation would negatively predict work volition over time, which in turn would negatively predict academic satisfaction over time. This has implications for how practitioners and school personnel can effectively support economically marginalized college students.

Theoretical background

The Psychology of Working Theory (PWT; Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016) is a vocational perspective that integrates an understanding of how individual-psychological variables and structural variables intersect to predict work-related and well-being outcomes. As it applies to adults, the PWT places the attainment of decent work as its central construct. Decent work is employment that provides sufficient compensation and healthcare, safe working conditions, fair working hours, and organizational values consistent with one’s family and community values (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016). The theory proposes that economic constraints and experiences of marginalization—are direct predictors of securing decent work over time, with those with higher economic resources and lower experiences of discrimination more likely to secure decent work. Additionally, the PWT proposed two mediator variables—or reasons why—these structural variables relate to the attainment of decent work. One is career adaptability, or one’s ability to navigate vocational obstacles (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), and the other is work volition. Specifically, people with greater economic resources and less experiences of marginalization are better able to attain decent work in part because they are more adaptable in the world of work and feel greater choice in their careers. Obtaining decent work, in turn, allows people to meet their needs and experience greater well-being, including greater academic life satisfaction and less depression, anxiety, and stress.

Recent studies have found general support for the predictor portion of the PWT among working adult populations (Douglass, Velez, Conlin, Duffy, & England, 2017; Duffy et al., 2018). Duffy et al. (2017) examined core propositions from the PWT in a sample of working adults who identified as racial or ethnic minorities, and Douglass et al. (2017) examined these same propositions in a sample of working adults who identified as sexual minorities. Both of these studies found strong support for the pathways surrounding work volition, which was indeed a significant predictor of decent work and a variable that mediated the relation of social status to decent work (Douglass et al., 2017). Additionally, Tokar and Kaut tested the predictor model with a sample of working adults with Chiari malformation, finding that economic deprivation predicted work volition and decent work. In summary, cross-sectional research has largely supported the relation between economic constraints and work volition among adult populations. However, few longitudinal studies have evaluated these findings further in a college student population.

Research on PWT principles with college students

The PWT’s principles readily apply to college students, and a number of studies have used it with this population. For example, Duffy et al. (2012) developed a work volition scale for college students, and scores on this scale correlated with structural, vocational, academic, and well-being variables. Students who feel greater choice in their careers tend to come from majority racial/ethnic backgrounds, endorse higher social status, and report lower career related barriers (Duffy, Douglass, Autin, & Allan, 2016; Jadidian & Duffy, 2012). Students who feel volitional also endorse greater levels of career decision self-efficacy, career adaptability, occupational engagement, major satisfaction, intentions to persist with one’s degree program, sense of general control, and life satisfaction (Bouchard & Nauta, 2018; Buyukgoze-Kavas, Duffy, & Douglass, 2015; Duffy, Douglass, & Autin, 2015; Kim, Kim, & Lee, 2016; Jadidian & Duffy, 2012). In other words, students with greater privilege (e.g., continuing generation college students) are more likely to have choice in their career, which in turn predicts positive career, academic, and well-being outcomes. In contrast, marginalized students, such as first generation college students, tend to report less academic choice and more barriers to life and academic satisfaction (e.g., Allan, Garriott, & Keene, 2016). Scholars have suggested that this occurs because students with choice in their future careers experience academic satisfaction in the present due to having confidence that they will be able to pursue the career of their choice post-graduation and obtain decent work. This confidence allows students to actively pursue satisfying courses and majors while in college.

The first study to examine work volition among college students, specifically framed from a PWT perspective, surveyed students at three time points over a six month period and explored the longitudinal relations of social status to work volition and career adaptability over time (Autin, Douglass, Duffy, England, & Allan, 2017). The authors found that, as hypothesized by the PWT, higher social status predicted higher levels of work volition over time, which in turn predicted greater career adaptability. In other words, college students from higher social status backgrounds developed a greater sense of choice in their careers over time, which may have boosted their adaptability. The results of this study inform the current study by underscoring the temporal effects of social status on work volition and work volition on vocational and academic outcomes. However, higher social status is primarily a proxy variable, encapsulating aspects of social class like access to resources and social capital. Therefore, exploring what specific aspects of social status, like economic deprivation, predict work volition is an important next step of research. Moreover, Autin et al. (2017) did not measure work volition’s longitudinal relation to well-being outcomes. As indicated in the PWT, this is an important outcome of work volition that may have the greatest relevance for students’ lives. Therefore, in the current study, we sought to extend this research to examine economic deprivation as a predictor of work volition and academic satisfaction as an outcome of work volition.

Socioeconomic variables and academic satisfaction

Outside the context of the PWT, numerous other studies have examined how socioeconomic variables relate to students’ academic satisfaction and adjustment, but few have looked at these relations over time. Furthermore, most of these studies have sampled from school-age populations (Felner et al., 1995; Gilbert, Brown, & Mistry, 2017), which are notably different from college-aged populations. Nevertheless, school-aged children and adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds perform less well academically and have poorer academic adjustment (Bolger, Patterson, Thompson, & Kupersmidt, 1995; Felner et al., 1995). Similarly, first-generation college students report lower levels of academic satisfaction and lower grade-point averages (GPA), potentially due to their experiences of institutional and interpersonal classism (Allan et al., 2016). Social support appears to be a protective factor between socioeconomic status and academic satisfaction such that students whose parents are more involved and who have multiple sources of social support seem to have higher levels of academic satisfaction than their less-supported counterparts (DeGarmo & Martinez, 2006; Fang, Sun, & Yuen, 2016; Gilbertet al., 2017). This may be in part due to parents protecting their children from the negative consequences of economic hardship (Mistry, Tan, Benner, & Kim, 2009).

Moreover, adolescent students who are aware of and experience familial financial hardship and related stressors may be more likely to exhibit emotional distress as well as symptoms of depression (Mistry et al., 2009; Morales & Guerra, 2006). Students who experience economic hardship may be less engaged at school and have decreased positive attitudes about the role that education will play in their future, although in some populations (e.g., Chinese migrant children), economic hardship appeared to provide motivation for students to strive for success academically (Fang et al., 2016; Mistry et al., 2009). Therefore, researchers have found that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds largely face poorer academic performance, adjustment, and satisfaction as well as increased emotional distress and depressive symptoms. However, these previous studies were cross-sectional, and no known studies have examined these relations longitudinally in college students. Without such studies, the evidence for economic deprivation on academic outcomes, potentially via work volition, remains weak. Specifically, longitudinal studies can establish that changes in economic deprivation and work volition precede changes in academic satisfaction. This provides much stronger evidence for causation in naturalistic settings, when exploring variables experimentally is not possible.

The present study

Using a PWT perspective, the goal of the current study was to examine the temporal relations from economic deprivation to academic satisfaction of college students via work volition. Our study used a three-wave panel design to examine how economic deprivation, work volition, and academic satisfaction relate from Time 1 (baseline) to Time 2 (3 months) and Time 2 to Time 3 (6 months). This type of methodology has a number of strengths. First, this design allows for the detection of significant relations among the constructs (e.g., Time 1 economic deprivation to Time 2 work volition) while controlling for autoregressions between particular outcomes (e.g., Time 1 work volition to Time 2 work volition). Second, this design allows for the detection of the direction of these relations, specifically whether certain variables operate best as predictors, outcomes, or both. We chose a three-month interval because this gave sufficient time for students’ contexts to change. For example, students started a new semester during this time, which likely affected their academic satisfaction.

Finally, building off previous research (e.g., Autin et al., 2017), we extended research on social class’s relation to work volition to specifically examine economic deprivation’s longitudinal relation to work volition. We argue that economic deprivation better captures the PWT’s variable of economic constraints. Rather than social class generally, economic deprivation may specifically restrict students’ ability to engage in career building activities in college, such as unpaid internships and extracurricular activities, that may allow students to have greater work choice in their work. Therefore, economic deprivation is a more targeted variable that may represent the core reason why social status related to work volition. In addition, although the PWT specified variables like job satisfaction and meaningful work as well-being outcomes, we chose academic satisfaction as the outcome because it is a viable domain-specific well-being variable for college students (Lent et al., 2005) that has specific implications for students’ success and retention in college (Roberts & Styron, 2010). Moreover, academic satisfaction represents a key well-being variable linked to work volition (Jadidian & Duffy, 2012).

Drawing from the PWT (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016) and evidence from previous research on work volition in student populations (Autin et al., 2017; Duffy, Douglass et al., 2016; Jadidian & Duffy, 2012), we examined a number of hypotheses. We hypothesized that, over time, economic deprivation would negatively predict work volition from Time 1 to Time 2 and Time 2 to Time 3 (Hypothesis 1), work volition would positively predict academic satisfaction Time 1 to Time 2 and Time 2 to Time 3 (Hypothesis 2), and that Time 2 work volition would mediate the relation between Time 1 economic deprivation and Time 3 academic satisfaction (Hypothesis 3). Specifically, we proposed that the reason why students with economic deprivation experience lower academic satisfaction in college is due to less perceived choice in their careers.

We also tested this theoretically-derived model against two alternative models. First, we examined a reverse model, with academic satisfaction predicting work volition and work volition predicting economic constraints. This test can rule out the alternative hypothesis that being satisfied with one’s academic pursuits bolsters students’ work volition, which drives students to acquire more academic resources. Finally, we tested the full reciprocal model where economic deprivation, work volition, and academic satisfaction predict each other over time. This can rule out the alternative model that these variables operate in a dynamic system where they mutually affect each other over time.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1508 undergraduate students who completed at least one valid wave. Age ranged from 18 to 60 (M = 19.92, SD = 1.79). Of the people who reported gender, 61.80% (n = 932) identified as female, 37.79% (n = 570) identified as male, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as agender, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as androgyne, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as demiflux, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as gender fluid, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as gendered, 0.07% (n = 1) identified as non-binary. Most people identified as White/European American (n = 1147, 76.06%) followed by Asian/Asian American (n = 161, 10.68%), Asian Indian (n = 62, 4.11%), Multiracial (n = 49, 3.25%), Hispanic/Latin/o American (n = 48, 3.18%), African/African-American/Black (n = 27, 1.79%), Arab American/Middle Eastern (n = 5, 0.33%), other (n = 5, 0.33%), American Indian/Native American/First Nation (n = 3, 0.20%), and Pacific Islander (N = 1, 0.07%). Around 14.00% of the sample identified as a first-generation college student (n = 211). Regarding parents’ yearly income, people reported belonging to the brackets less than $25,000 per year (n = 73, 4.8%), $25,000–$50,000 (n = 132, 8.8%), $51,000–$75,000 (n = 171, 11.3%), followed by $76,000–$100,000 (n = 205, 13.60%), $101,000–$125,000 per year (n = 211, 14.00%), $126,000–$150,000 (n = 118, 7.80%), $151,000–$175,000 (n = 82, 5.40%), $176,000–$200,000 (n = 76, 5.00%), $200,000 + (n = 179, 11.9%), and “I don’t know” (n = 135, 9.00%).

Instruments

Economic constraints

We used the 7-item Economic Deprivation Scale to assess peoples’ perception of their lack of economic resources (EcDS; Brief et al., 1995). Sample items include, “I have a difficult time making ends meet.” and “Right now, even if I needed one, I cannot afford to see a doctor or dentist.” Students indicated their agreement with each item on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. In the original study, researchers reported an internal consistency reliability coefficient of α = 0.89, and scores from the measure correlation in the expected direction with financial resources and subjective well-being (Brief et al., 1995). In the present study, the estimated internal consistency reliability coefficient for each time point was α = 0.91 for time 1, α = 0.90 for time 2, and α = 0.90 for time 3.

Work volition

We used the 16-item Work Volition Scale—Student Version to assess people’s perceptions of their ability to make occupational choices among college students, where higher scores indicate greater perception of choice (Duffy et al., 2012). Example items include, “I feel that my family situation limits the types of jobs I might pursue” and “I will be able to change jobs if I want to.” Participants indicated their agreement with each item on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Work volition correlated in the expected directions with related constructs, such as core self-evaluations and career decision self-efficacy (Duffy et al., 2012). The two-week test–retest correlation was r = .73, and estimated internal consistency was α = 0.92 for the total scale in the original study. In the present study, the estimated internal consistency coefficients for each time point were α = 0.89, α = 0.91, and α = 0.90 respectively.

Academic satisfaction

We used a 7-item measure to assess peoples’ satisfaction with their current academic life and major (Lent et al., 2005). Example items include, “I enjoy the level of intellectual stimulation in my courses,” and “I feel enthusiastic about the subject matter in my intended major.” People were asked to indicate their agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The scale had good internal consistency in the original study (α = 0.94) and correlated with other measures of well-being, such as life satisfaction (Lent et al., 2005). In the present study, the estimated internal consistency reliability coefficient for each time point was α = 0.89 for time 1, α = 0.89 for time 2, and α = 0.90 for time 3.

Procedure

After we obtained Institutional Review Board approval, participants were recruited from a large research university in the Midwest. We requested the university’s registrar to send out an announcement to all undergraduate students with study information, and those interested could click a link to the survey. We collected the first wave in the middle of the fall semester. Students received the second survey three months after baseline and the third survey six months after baseline. Participants were invited to participate in the third wave, regardless of whether or not they completed the second wave. At the end of each survey, participants clicked a link to a separate survey where they provided their e-mail for a chance to win one of ten $15 Amazon gift cards for each of the three waves. In preparation for data analysis, we removed 3 cases for disagreeing to the informed consent agreement, 3 for not responding to the informed consent agreement, 213 for providing no data past the informed consent agreement, and 128 for only providing demographic information. This brought our total sample size to 1508 participants who completed at least one wave. Of these participants, 1382 completed the first wave, 679 completed the second wave, and 499 completed the third wave.

Analysis plan

To analyze the longitudinal data, we used latent variable, autoregressive models in AMOS 24.0 with maximum likelihood estimation. This analysis uses full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle missing data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Before testing the structural models, we tested a measurement model and the measurement invariance across time. The measurement model included each indicator loading onto its respective factor and allowed for correlations among each latent factor. We allowed from the same indicators across waves to correlate with one another (e.g., academic satisfaction parcel one wave one and academic satisfaction parcel one wave two). This model evaluated how well indicators loaded on their respective factors.

Longitudinal measurement invariance involves restricting certain parameters across time and observing whether fits declines (Kline, 2016). Although differences in fit can be evaluated by a Chi square difference test, changes in Chi square are highly sensitive to sample size. Therefore, Cheung and Rensvold (2002) recommend observing changes in CFI to evaluate practical significance in invariance models (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Specifically, a change in CFI greater than 0.01 is substantial (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). We also included changes in RMSEA, with changes greater than .015 indicating a substantial change in fit (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). We tested measurement invariance by restricting only the factor structure to be the same across time (configural invariance). Second, we restricted factors loadings to be equivalent for each construct across time (weak invariance). Third, restricted both factor loadings and corresponding indicator means to be the same across time (strong invariance).

We selected fit indices that minimized the likelihood of Type I and Type II errors (Hu & Bentler, 1999). These included the Chi square test (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A significant χ2 can indicate a poor fitting model, but this test is not reliable in larger samples. Criteria for the CFI and RMSEA have ranged from less conservative (CFI ≥ 0.900; RMSEA ≤ 0.100) to more conservative (CFI ≥ 0.950; RMSEA ≤ 0.080; Hu & Bentler, 1999), but researchers should consider evidence from all sources when accepting or rejecting models. For each model, we allowed errors for each indicator to correlate with their respective errors at different waves and study variables to correlate with each other at each wave. We evaluated the difference between nested models with the Chi square difference test.

After testing the measurement model and establishing temporal invariance, we tested four structural models. Model 1 included only paths between the same variables; in other words, the model included no paths among different study variables over time. Model 2 included the theoretically-derived paths—from economic deprivation to work volition and from work volition to academic satisfaction. Model 3 was the reversed alternative model—in this model, academic satisfaction predicted work volition, and work volition predicted economic deprivation. This model tested the alternative hypothesis that academic satisfaction leads to greater work volition, which then leads to less economic deprivation. Finally, Model 4 tested a reciprocal model, which added paths from academic satisfaction to work volition and paths from work volition to economic deprivation. In essence, this model combined Models 2 and 3.

For the latent constructs, we created parcels to use as indicators. When conducting structural equation models with latent variables, the creation of item parcels has several advantages over item level indicators, such as more precise parameter estimates, better model fit, less bias in estimates, increased reliability, and reduced levels of skewness and kurtosis (e.g., Bandalos, 2002; Dow, Jackson, Wong, & Leitch, 2008; Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002; MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang, & Hong, 1999). To create parcels for economic constraints and academic satisfaction, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis and assigned items to parcels in countervailing order according to the size of the factor loading so that the parcels would have approximately equivalent factor loadings (Weston & Gore, 2006). Given that work volition has two subscales and using two indicators for a factor is problematic (Kline, 2016), we created two parcels for each work volition subscale, resulting in four parcels in total.

Results

To conduct analyses, we used maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS 24.0. All variables had absolute values of skewness and kurtosis within acceptable ranges (> |3| for skewness and > |10| for kurtosis; Weston & Gore, 2006), so we did not transform the data. To assess for patterns of missing data, we created a dummy code variable representing those with and without missing data. This variable was not related to any study variables, except for Time 1 (r = − .06, p = .03) and Time 2 (r = − .08, p = .03) academic satisfaction. This indicated that people higher in academic satisfaction were slightly less likely to have missing data. However, these effect sizes were small and only significant given the power of the sample. The missing variable also had a relation to gender (r = .06, p = .02), indicating that that men were slightly more likely to have missing data than women. However, this effect size was also small, and the missing dummy variable was not related to any other demographic variable.

Finally, we conducted a series of analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi square tests to examine if the participants in each wave of the study differed on any demographic variable. The Chi squares for gender, χ2(22) = 10.15, p = .574, and race, χ2(18) = 26.93, p = .080, were not significant indicating that the waves did not differ on either of these variables. The ANOVA for parental income, F(2, 2555) = 0.68, p = .507, was not significant, but the ANOVA for age was significant, F(2, 2556) = 10.85, p < .001. However, we expected this result because the study was over a 6 month period, and many of the participants had birthdays over the course of the study. The means for Wave 1 (M = 19.90), Wave 2 (M = 20.06), and Wave 3 (M = 20.42) were consistent with this interpretation, and according to the correlation between the drop out variable and age (r = .003, p = .912), those who were older at Wave 1 were not more likely to drop out of the study. Therefore, for practical purposes, we considered the data missing completely at random and used FIML to handle missing data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Measurement model and invariance

The measurement model had acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (339) = 1727.27, p < .001, TLI = .909, CFI = .934, RMSEA = .052, and 90% CI [.050, .055], and all indicators loaded on their factors at values of .67 or above. The acceptable fit of the model indicated configural invariance. Table 1 displays the factor correlations and descriptive statistics for each study wave. For weak invariance, the model restricting all respective factor loadings to be the same across waves, χ2 (353) = 1738.38, p < .001, TLI = .913, CFI = .934, RMSEA = .051, and 90% CI [.049, .053], was not significantly different from the measurement model, Δχ2 (14) = 11.12, p = .68, ΔCFI = < .001, and ΔRMSEA = .001. For strong invariance, although the change in Chi square was significant, χ2 (373) = 1790.92, p < .001, TLI = .915, CFI = .932, RMSEA = .050, and 90% CI [.048, .053], Δχ2 (34) = 63.65, the change in CFI (ΔCFI = .002) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA = .002) were not. Therefore, we assumed strong factorial invariance across time.

Structural models

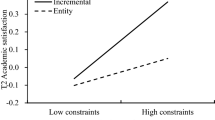

Table 2 displays the fit statistics for the tests of the structural models. Model 1 was a baseline model that only included paths to and from the same variables across time (e.g., work volition wave 1 to work volition wave 2). This model had acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (360) = 1831.49, p < .001, TLI = .909, CFI = .930, RMSEA = .052, and 90% CI [.050, .054]. Model 2 was the theoretically-derived model with paths from economic deprivation to work volition and work volition to academic satisfaction. This model, χ2 (356) = 1810.49, p < .001, TLI = .909, CFI = .930, RMSEA = .052, and 90% CI [.050, .054], had significantly better indices of fit than Model 1, Δχ2 (4) = 21.00, p < .001. Model 3 reversed the paths from Model 2. While this model, χ2 (356) = 1821.72, p < .001, TLI = .908, CFI = .930, RMSEA = .052, and 90% CI [.05, .06], also significantly improved on Model 1, Δχ2 (4) = 9.77, p < .05, this result was borderline significant, and the model had a larger Chi square than Model 2, Δχ2 = 11.23. A Chi square difference test between Models 2 and 3 was not possible, given their equal degrees of freedom, but Model 3 did not improve upon the fit of Model 2. Model 4 included the full reciprocal paths between economic deprivation and work volition and work volition and academic satisfaction. This model, χ2 (352) = 1802.18, p < .001, TLI = .908, CFI = .931, RMSEA = .052, and 90% CI [.050, 0.055], was also not significantly better fit than Model 2, Δχ2 (4) = 8.31, p = .08. Therefore, Model 2 emerged as the best fitting structural model. Figure 1 displays the standardized regression coefficients from this final model.

Indirect effect

To calculate the indirect effect, we used RMediation, which uses the distribution of the product of coefficients method to create confidence intervals (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). Indirect effects are significant if their 95% confidence interval does not include zero. The indirect effect of time 1 economic deprivation to time 3 academic satisfaction via work volition was not significant (95% CI = − 0.01, 0.00).

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine the temporal relations from economic deprivation to academic satisfaction via work volition. With a large sample of college students surveyed at three time points over a six-month period, we found partial support for our hypotheses, which were concordant with the Psychology of Working Theory’s propositions (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016). Specifically, economic deprivation negatively predicted work volition from Time 1 to Time 2, and work volition positively predicted academic satisfaction from Time 1 to Time 2 and Time 2 to Time 3. These findings add to the academic satisfaction literature and inform PWT research applied to student populations.

The Psychology of Working Theory attempts to explain how structural factors, such as economic deprivation, interact with individual-psychological factors, such as work volition, to affect academic and work-related experiences and, subsequently, well-being (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016). Although the PWT initially described the way these structural factors may affect the experiences of working adults, the principles of structural factors influencing work volition and, in turn, satisfaction within a particular domain apply to college students as well. Indeed, numerous studies have found that structural conditions perpetuate in college to disadvantage marginalized students and maintain inequality (e.g., Allan et al., 2016; Haveman & Smeeding, 2006). Moreover, studies based on the PWT have found that aspects of privilege predict greater work volition over time (Autin et al., 2017) and that work volition is correlated with a host of outcomes, such as greater levels of career decision self-efficacy, career adaptability, major satisfaction, sense of control, and life satisfaction (Bouchard & Nauta, 2018; Buyukgoze-Kavas et al., 2015; Duffy et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2016; Jadidian & Duffy, 2012).

In the current study, we extended this previous research to longitudinally examine economic deprivation as one salient form of marginalization and academic satisfaction as an important potential outcome of work volition. Our first finding indicated that students who experienced a rise in their work volition were more likely to experience a rise in their academic satisfaction three months later. This result corroborates previous research finding links between these variables cross-sectionally (e.g., Bouchard & Nauta, 2018; Jadidian & Duffy, 2012), fits with PWT explanations of well-being, and extends existing cross-sectional research to identify work volition as a longitudinal predictor of academic satisfaction. Students who believe that they will be able to choose their work post-graduation may view their courses, majors, and other academic activities as more valuable because they can take advantage of these experiences to obtain decent work. This may lead them to be more satisfied in their academics. In contrast, students who believe that they will have to take poorer quality work due to structural factors may view their academics as less meaningful and be less satisfied as a result. Finding that this link exists longitudinally is novel and suggests that work volition is an important antecedent of academic satisfaction.

Our results suggest that experiences of economic deprivation may affect the degree to which student develop this sense of choice. Specifically, the Time 1 to Time 2 links between these variables show that students with greater economic deprivation were less likely to feel volitional in their career decision-making. Corroborating numerous prior cross-sectional (Allan et al., 2016; Douglass et al., 2017; Duffy, Douglass et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2018) and longitudinal studies (Autin et al., 2017), as well as core propositions of the PWT, these findings showcase the role of structural factors on feelings of choice. The current study also extends this research to include economic deprivation, a variable not previously studied longitudinally in relation to work volition and academic satisfaction. Students from marginalized groups with less access to financial resources may be less likely to feel like they will be able choose the career they want post-graduation. Importantly, this core sense of volition may then lead to a lowered sense of academic satisfaction. Therefore, these findings highlight the role that work volition has on explaining why marginalized and under-resourced students may be less satisfied in college.

However, although statistically significant, the effect size from economic deprivation to work volition was small, there were only significant paths between the first and second wave, and the indirect effect from economic deprivation to academic satisfaction to academic satisfaction via work volition was not significant. There may be several explanations for these findings. First, these may be due to when students completed the surveys. The first wave occurred during the middle of the fall semester, the second wave occurred a month and a half into the spring semester, and the third wave occurred at the end of the spring semester. As we mentioned above, we chose a six-month timeframe to allow enough time for variables to change and affect one another, and this included a semester change between Times 1 and 2. Semester changes are major shifts for undergraduate students, which lead to changes in environments and academic satisfaction as they change courses, professors, classmates, or even majors. Experiences in previous semesters may lead to changes in latter semesters as students make decisions about which opportunities to pursue—the change in semester makes these decisions a reality. Therefore, semester changes may be a time when economic deprivation leads to changes in work volition. In contrast, periods within semesters may be less subject to change, which is corroborated by the smaller autoregressions between Times 1 and 2 as compared to between Times 2 and 3.

Second, in regards to small effect sizes, the PWT articulates that being economically disadvantaged is a lifelong process that starts early in people’s lives (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016). Students who have economic constraints in college have likely experienced economic deprivation for some time, which they have likely already incorporated into their perceptions of work volition. In other words, this is a slow process where disadvantage accumulates over time (Dannefer, 2003). Therefore, studies like this may observe small effect sizes over a three month period, but the lack of access to economic resources may effect work volition accumulatively over longer periods of time.

Practical implications

These results have implications for counselors and institutions working with economically marginalized college students. Previous research indicates that institutional policies can marginalize students with economic constraints by excluding them from school-related activities that cost money (Allan et al., 2016). This could impact students’ work volition by hindering them from obtaining internships and volunteer opportunities that provide valuable work experience or job offers (Diemer & Rasheed Ali, 2009), and the low academic satisfaction that may result could cause students to leave college (Roberts & Styron, 2010). Therefore, institutions should appropriately waive fees for student activities and enact programs to support low-income students. Career centers, in particular, might incorporate an understanding of how economic constraints may affect some students’ ability to choose their preferred career versus only focusing on students’ passions or interests.

Counselors working with students who are economically marginalized should consider issues of oppression and privilege related to a number of different social statuses and identities, including race, social class, gender, and sexual orientation (Smith, 2008; Vera & Speight, 2003), and how economic constraints affect students’ ability to select their future work. Broadly, counselors and other college personnel should not disregard the economic burdens placed on some students, and they should examine their own worldviews and consider how their social class biases may affect their work with students (Liu, Soleck, Hopps, Dunston, & Pickett, 2004; Smith, 2008). Career counselors in colleges should especially be aware of economic and social privileges when providing guidance to students—not all students will have the same access to opportunities or the same ability to choose their future work. For example, low-income students often have to work part- or full-time jobs during college, leaving little free time for extracurricular activities that might help build their resumes. Assuming students can and should choose careers that align with their interests may impose the counselor’s values on the client and ignore the realities of how economic burdens affect people’s career trajectories.

Limitations and future directions

The current study has several limitations that can inform future research. Although the present study provided longitudinal support for our hypotheses, the study was not experimental. Therefore, we cannot conclude with certainty that the variables in the current study are causally related. However, the temporal relations established in this study provide the strongest evidence of causality to date. Continued intervention and other experimental efforts would continue to support the causal relations within the PWT. Another limitation of the present study was the relatively privileged sample from which data was collected—participants were recruited from a large, public research university in the Midwestern United States with over 76% of the participants identifying as White (n = 1147), less than 15% of the participants as first-generation college students (n = 211), and most participants a high level of parental income. Although inequities still perpetuate in universities (e.g., Allan et al., 2016), the current study’s sample creates issues. First, it may affect generalizability to other colleges and other geographic locations. Second, there may be stronger links between economic deprivation, work volition, and academic satisfaction present in students from less privileged backgrounds. In other words, third variables, such as parental income and years spent in school, may moderate these relations. Therefore, future research should continue to test the PWT’s propositions in diverse samples and evaluate potential moderators of economic deprivation, work volition, and academic satisfaction.

As suggested by the authors of the PWT (Duffy, Blustein et al., 2016), we tested a limited amounted of variables that might account for well-being in college students. To aid intervention studies, future research should investigate potential protective factors, such as proactive personality, critical consciousness, and social support. Accordingly, the present study did not offer evidence on how to intervene with students’ work volition and academic satisfaction when they feel economically constrained. While our study offers a place to start, future research should examine interventions to increase work volition among college students.

Conclusion

The present study provides support for economic deprivation predicting work volition over time and work volition predicting academic satisfaction over time. These results provide support for several hypotheses with the PWT and have implications for practitioners and institutions working with economically disadvantaged and marginalized students. Namely, targeting economic constraints and work volition may be critical for helping students increase their academic satisfaction. Although the present study has limitations, it informs current and future research by highlighting the primary role of work volition for low-income students.

References

Allan, B. A., Garriott, P. O., & Keene, C. N. (2016). Outcomes of social class and classism in first- and continuing-generation college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology,63(4), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000160.

Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., Duffy, R. D., England, J. W., & Allan, B. A. (2017). Subjective social status, work volition, and career adaptability: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior,99, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.11.007.

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,9(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5.

Bolger, K. E., Patterson, C. J., Thompson, W. W., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1995). Psychosocial adjustment among children experiencing persistent and intermittent family economic hardship. Child Development,66(4), 1107–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00926.x.

Bouchard, L. M., & Nauta, M. M. (2018). College students’ health and short-term career outcomes: Examining work volition as a mediator. Journal of Career Development, 45(4), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317699517.

Brief, A. P., Konovsky, M. A., Goodwin, R., & Link, K. (1995). Inferring the meaning of work from the effects of unemployment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,25(8), 693–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01769.x.

Buyukgoze-Kavas, A., Duffy, R. D., & Douglass, R. P. (2015). Exploring links between career adaptability, work volition, and well-being among Turkish students. Journal of Vocational Behavior,90, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.08.006.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling,9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,58(6), S327–S337.

DeGarmo, D. S., & Martinez, C. R., Jr. (2006). A culturally informed model of academic well-being for Latino youth: The importance of discriminatory experiences and social support. Family Relations,55(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00401.x.

Diemer, M. A., & Rasheed Ali, S. (2009). Integrating social class into vocational psychology: Scholarly and practice implications. Journal of Career Assessment,17(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072708330462.

Douglass, R. P., Velez, B. L., Conlin, S. E., Duffy, R. D., & England, J. W. (2017). Examining the psychology of working theory: Decent work among sexual minorities. Journal of Counseling Psychology,64(5), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000212.

Dow, K. E., Jackson, C., Wong, J., & Leitch, R. A. (2008). A comparison of structural equation modeling approaches: The case of user acceptance of information systems. Journal of Computer Information Systems,48(4), 106–114.

Duffy, R. D., Blustein, D. L., Diemer, M. A., & Autin, K. L. (2016). The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology,63(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000140.

Duffy, R. D., Diemer, M. A., & Jadidian, A. (2012). The development and initial validation of the Work Volition Scale-Student Version. The Counseling Psychologist,40(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011417147.

Duffy, R. D., Douglass, R. P., & Autin, K. L. (2015). Career adaptability and academic satisfaction: Examining work volition and self efficacy as mediators. Journal of Vocational Behavior,90, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.07.007.

Duffy, R. D., Douglass, R. P., Autin, K. L., & Allan, B. A. (2016). Examining predictors of work volition among undergraduate students. Journal of Career Assessment,24(3), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072715599377.

Duffy, R. D., Velez, B. L., England, J. W., Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., Allan, B. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2018). An examination of the Psychology of Working Theory with racially and ethnically diverse employed adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology,65(3), 280.

Fang, L., Sun, R. C., & Yuen, M. (2016). Acculturation, economic stress, social relationships and school satisfaction among migrant children in urban China. Journal of Happiness Studies,17(2), 507–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9604-6.

Felner, R. D., Brand, S., DuBois, D. L., Adan, A. M., Mulhall, P. F., & Evans, E. G. (1995). Socioeconomic disadvantage, proximal environmental experiences, and socioemotional and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of a mediated effects model. Child Development,66(3), 774–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00905.x.

Garriott, P. O., Hudyma, A., Keene, C., & Santiago, D. (2015). Social cognitive predictors of first- and non-first generation college students’ academic and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology,62(2), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000066.

Gilbert, L. R., Spears Brown, C., & Mistry, R. S. (2017). Latino immigrant parents’ financial stress, depression, and academic involvement predicting child academic success. Psychology in the Schools,54(9), 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22067.

Haveman, R. H., & Smeeding, T. M. (2006). The role of higher education in social mobility. The Future of Children,16, 125–150.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jadidian, A., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Work volition, career decision self-efficacy, and academic satisfaction: An examination of mediators and moderators. Journal of Career Assessment,20(2), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711420851.

Kim, N. R., Kim, H. J., & Lee, K. H. (2016). Social support and occupational engagement among Korean undergraduates: The moderating and mediating effect of work Volition. Journal of Career Development,42(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316682319.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Kochhar, R., & Fry, R. (2014). Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession. Pew Research Center,12, 1–15.

Lent, R. W., do Céu Taveira, M., Sheu, H., & Singley, D. (2009). Social cognitive predictors of academic adjustment and life satisfaction in Portuguese college students: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior,74, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.006.

Lent, R. W., Singley, D., Sheu, H. B., Gainor, K. A., Brenner, B. R., Treistman, D., & Ades, L. (2005). Social cognitive predictors of domain and life satisfaction: Exploring the theoretical precursors of subjective well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology,52(3), 429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.429.

Lent, R. W., Singley, D., Sheu, H.-B., Schmidt, J. A., & Schmidt, L. C. (2007). Relation of social-cognitive factors to academic satisfaction in engineering students. Journal of Career Assessment,15(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072706294518.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question and weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling,9, 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Liu, W. M., Soleck, G., Hopps, J., Dunston, K., & Pickett, T. (2004). A new framework to understand social class in counseling: The social class worldview model and modern classism theory. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development,32(2), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2004.tb00364.x.

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods,4, 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84.

Mistry, R. S., Benner, A. D., Tan, C. S., & Kim, S. Y. (2009). Family economic stress and academic well-being among Chinese-American youth: The influence of adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain. Journal of Family Psychology,23(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015403.

Morales, J. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2006). Effects of multiple context and cumulative stress on urban children’s adjustment in elementary school. Child Development,77(4), 907–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00910.x.

Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review,41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004.

Roberts, J., & Styron, R. (2010). Student satisfaction and persistence: Factors vital to student retention. Research in Higher Education Journal,6, 1–18.

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior,80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011.

Schertzer, C. B., & Schertzer, S. M. B. (2004). Student satisfaction and retention: A conceptual model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education,14(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v14n01_05.

Smith, L. (2008). Positioning classism within counseling psychology’s social justice agenda. The Counseling Psychologist,36, 895–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007309861.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Tofighi, D., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods,43(3), 692–700. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x.

Vera, E. M., & Speight, S. L. (2003). Multicultural competence, social justice, and counseling psychology: Expanding our roles. The Counseling Psychologist,31(3), 253–272.

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A., Jr. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist,34(5), 719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allan, B.A., Sterling, H.M. & Duffy, R.D. Longitudinal relations among economic deprivation, work volition, and academic satisfaction: a psychology of working perspective. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 20, 311–329 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09405-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09405-3