Abstract

Expert advice is gaining importance in advanced-knowledge societies. The demand for scientific knowledge increases as political decision-makers look for answers to cope with the ever more complex challenges of a globalised world. At the same time, scientific evidence has become a strategic resource capable of justifying world-views and political positions. Against this background, the ‘global spread’ of think tanks seems to respond to this growing demand for scientific expertise. Defining what a think tank is, let alone what they do and if they are able to effectively shape political ideas, is still a controversial issue. This contribution outlines a conceptual framework for analysing the strategies of different types of think tanks in distinct institutional environments. Starting with classical typologies to distinguish between organisations, those which adhere to standards of scientific inquiry at one end of a continuum and ideologically biased institutes at the other, the analytical model takes into account distinct ‘points of intervention’ and systematically considers the respective institutional and ideological environment. The first dimension allows for distinguishing between distinct effects of political ideas: They can influence decision-making as concepts in the foreground or as underlying assumptions in the background of policy debates. At the cognitive level, they can function either as programmes (foreground), serving as policy prescriptions for the political elite necessary to formulate actual agendas, or as paradigms (background). Considering different ‘knowledge regimes’ permits to test the influence of respective institutional and normative settings and simultaneously assess the assumptions and convictions underlying these models and typologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

‘Think tanks are important because the media believes they are important and the media believes in this importance because think tanks tell them they are.’

(Hames 1994, p. 233)

Think tanks have attracted the interest of a growing number of political scientists and sociologists. Or maybe it is more precise to say ‘so-called’ think tanks have become the centre of academic curiosity, thus ‘generating vast quantities of policy research’ (Hird 2005, p. 1). How can there be a vast quantity of research on think tanks despite the apparent lack of consensus of what a (so-called) think tank actually is? To complicate things further, the numbers of these obscure organisations seem to grow. And, they do so on an international level as they seemingly become ever more influential in policymaking. According to Donald Abelson, the global spread of think tanks is regarded as ‘indicative of their growing importance in the policy-making process, a perception reinforced by directors of think tanks, who often credit their institutions with influencing major policy debates and government legislation’ (2009, p. 3). Do scholars believe in the importance of think tanks because they are told so, by think tanks?

It would be unfair to blame researchers and scholars for falling short of a full understanding of the outlook, behaviour, strategies and eventually the impact of think tanks on policymaking processes. For researchers of these particular organisations face enormous obstacles. For instance, since some of the various roles think tanks can play in policymaking are remarkably similar to those of more classical special interest groups (McGann and Weaver 2000, p. 7), it could be in their interest to maintain secrecy about some of their activities (e.g. sources of income, spending or recruiting practices). Moreover, the term ‘think tank’ itself somehow falsely implies a uniformity of structure and properties that organisations labelled think tanks tend to lack. In consequence, even agreeing on a working definition of ‘think tank’ is a difficult undertaking.

In the relevant literature, the term is used to refer to a diverse set of research institutions, public policy institutes and consultancies. It has been described as more or less an ‘umbrella term that means many different things to many different people’ (Stone 1996, p. 9). Apart from the ‘lack of consensus […] in defining think tanks’ (McGann and Johnson 2005, p. 11), a working definition could describe them as ‘independent, non-profit research facilities, engaged in applied research provided to political decision makers’ (Ruser 2013, p. 331) Policy research by think tanks includes ‘analysis, advocacy, education and formulation’ (McGann, and Johnson 2005, pp. 11–12).

Abelson (2009) formulates one of the most elaborate definitions. He begins with a list of basic organisational characteristics that most think tanks have in common: ‘they are generally nonprofit, nonpartisan organizations engaged in the study of public policy’ (Abelson 2009, p. 9). Additionally, he considers the relatively broad spectrum of think tank behaviour:

Think Tanks can embrace whatever ideological orientation they desire and provide their expertise to any political candidate or office-holder willing to take advantage of their advice. […] Not all think tanks share the same commitment to scholarly research or devote comparable resources to performing this function, yet it remains, for many, their raison d’être (Abelson 2009, p. 10).

However, defining a set of activities or listing organisational features is barely enough to fully understand what think tanks do, to single out their idiosyncrasies and, most importantly, to determine if and how they can influence policymaking in their respective political environments. Nevertheless, Abelson’s detailed definition offers a suitable starting point for developing a more comprehensive, conceptual framework, which combines variation at the organisational level (typologies), distinct points of intervention in public discourses (role and types of ideas) and the particularities of different institutional environments (knowledge regimes). However, the resulting model can serve only as an analytical framework, since typologies are never able to fully capture the ambiguity of public policy institutes: Boundaries between research institutes, advocacy organisations or lobby groups are notoriously fuzzy. As will be discussed in more detail below, the term ‘think tank’ itself may have a strategic value that may be used by organisations that want to distance themselves from lobby or special interest groups. Moreover, organisations do not need to commit themselves to a set of techniques, strategies or other organisational features once and for all, but can behave more or less ‘think-tankish’ and switch between different roles if this serves their respective goals.

A Snapshot of a Frustrating Venture: the State of Think Tank Research

Given the ambiguity of the object of study, it is not surprising that scholarly work on think tanks, despite growing awareness of the phenomenon itself, is still in an infant state and ‘few definitive answers been offered’ (Abelson 2009, p. 3). More surprising is the widespread view (McGann 2000, p. 5ff, Stone 2004, p. 1f) that think tanks are influential no matter how mysterious these organisations still seem to be.

Murray Weidenbaum, for instance, acknowledges that think tanks might become more important players on the political arena. At the same time, he concedes that ‘[a]ctually trying to measure their impact on specific public policy changes, however, has frustrated scholars for years’ (2010, p. 135). David Ricci points in a similar direction, remarking that ‘[p]ower in Washington cannot be measured precisely, yet think tanks surely have a good deal of it’ (1993, p. 2). Weidenbaum, himself intimately acquainted with political Washington, gave up any hope for the precise measurement of think tank influence, describing such an undertaking as parallel to the difficult task of identifying pornography: Instead of defining it, one has to limit oneself to acknowledging: ‘I know it when I see it’ (Weidenbaum 2010, p. 135).

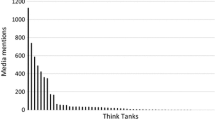

This is not to say the role and impact of think tanks cannot be analysed whatsoever. Cockett (1994) and Dixon (1998) conclusively demonstrated the influence of right-wing think tanks in the making of an ‘economic counter revolution’ and the rise of Thatcherism. For Mirowski (2013), think tanks belonged to the inner circles of the neoliberal ‘thought collective’ (2013, p. 44), heavily contributing to successfully defending the economic and political programme in spite of the massive financial crises since 2007. Even more telling is the case of anthropogenic climate change and responding climate politics. In a series of empirical studies, McCright and Dunlap (2003, 2010, 2011, 2015) were able to show how conservative think tanks contributed to fostering ‘climate denial’ in the USA. Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway’s seminal monograph Merchants of Doubt (2011) traces the impact of think tanks on a variety of public policy issues such as global warming, acid rain and the carcinogenic effects of smoking. Attempts to quantify think tank influence like James McGann’s Global Go-To Think Tank Index Reports (2010, 2016; McGann and Sabatini 2011) focus predominantly on basic quantitative data (e.g. number of think tanks in a given country or the growth in numbers over time) or expert estimation (subjective ranking of a respective think tank’s impact in a particular country and/or issue area).

Yet, the very existence of a ‘global’ think tank survey indicates a major transition in research on think tanks. For a long time, think tanks had been described as a specific phenomenon of the political systems of Anglo-Saxon countries, in particular the USA. This view was prominently formulated in David Ricci’s ‘habitat hypothesis’:

What needs explaining […] is not how to build and run a think tank but why so many of them became prominent in Washington during the 1970s and 1980s, more than was the case in, say, Rome, Ankara, Riyadh, Bonn or Djakarta. Here, what mattered was especially democratic context rather than vocational substance. We need to know, for example, why Washington’s political people became responsive to think-tank products even though those were, after all, standard research items other countries or eras might have ignored (Ricci 1993, p. 3).

From this perspective, the assessment made by McGann two decades later that ‘think tanks now operate in a variety of political systems, engage in a range of policy-related activities and comprise a diverse set of institutions that have varied organizational forms’ (McGann 2010) demands further explanation. Does it suggest a catching-up development with the USA on the global scale? At first glance, this seems to be a plausible explanation since, discounting national differences, ‘most think tanks share a common goal of producing high quality research and analysis that is combined with some form of public engagement’ (Braml 2006, p. 223). Maybe modern societies become more responsive to applicable research and analysis, rendering the global spread of think tanks a demand-driven adjustment in the market for political consulting?

To answer this question, one has to investigate what think tanks are actually doing. Can think tanks really be described consistently regardless of the social and political particularities of their surroundings or the institutional environment they operate in? For instance, what exactly is meant by ‘high-quality research’ and who defines the quality of the outcomes and the output of research conducted by think tanks? This question is highly relevant, yet difficult to answer. A suitable strategy could be focusing on the respective relation of think tanks and classical academic organisations such as universities or state-run research laboratories. ‘Established’ players in this field (e.g. ‘venerable’ universities) could limit the access to political decision-makers think tanks can gain. Likewise, think tank activities could be channelled towards subject areas where competition is lower.Footnote 1

Another important dimension is the public engagement of think tanks. While it is true that all think tanks are involved in some form of public engagement, this must not necessarily mean this is a general characteristic. In order to understand country-specific think tank behaviour, it is necessary to analyse the distribution of specific techniques at hand for think tanks to approach the public. Comparative studies look for specific patterns or ‘tradition’ of think tank activities (cf. Stone and Denham 2004) or investigate the impact of specific institutional settings on the strategies pursued by think tanks (Ruser 2013; Sheingate 2016). Comparative studies fuel doubt as to whether the global spread of think tanks can be explained by a ‘catch-up development’. It seems increasingly more plausible to assume parallel developments indicate that think tanks may fill different roles in different societal and political environments.

Furthermore, global trends towards ‘knowledge societies’ cannot explain directly the increasing number of think tanks worldwide. It is unlikely that institutional differences between societies will vanish in the process of transformation (Böhme and Stehr 1986, pp. 13–14) as is the convergence of the ways knowledge is fed in processes of public deliberation and decision-making.

Think Tanks in the Knowledge Society

Apparently, one promising explanation is to link the growing importance or, at least, the enhanced visibility of think tanks and public policy institutes to the emergence of ‘knowledge societies’ (Nowotny et al. 2001, p. 15). Is it not plausible to assume that organisations, which produce and disperse ‘knowledge’, would thrive in a world increasingly ‘made of knowledge’ (Stehr 2004, p. ix)? In fact it is, and hence why debates on knowledge societies tend to emphasise the growing influence of scientific expertise and knowledge on political decision-making (Osborne 2004, p. 431). The starting point for these discussions is a rather broad definition of knowledge societies: ‘The significance of knowledge is growing in all spheres of life and in all social institutions of modern society’ (Stehr and Meja 2005, p. 15).

Accordingly, not only is knowledge in high demand but also the providers of such knowledge should find plenty of new ‘customers’ beyond their classical audience: policymakers (Thunert 1999, p. 10). The increase in the number and global spread of think tanks is frequently referred to as an indicator of the growing importance of scientific advice in general (McGann and Johnson 2005, p. 12; Falk et al. 2006, pp. 2–14; Misztal 2012, p. 129). Think tanks could provide an invaluable service in modern knowledge societies, namely ‘to bridge the gap between science and politics’ (McGann and Johnson 2005, p. 12). However, one first has to ask what the increased importance of (scientific) knowledge actually means for the process of political decision-making. The relevant literature offers three distinct interpretations:

-

An optimistic approach expecting the rationalisation of political decision-making (Grundmann and Stehr 2012, p. 7)

-

A more pragmatic viewpoint, which argues that political decisions will be based on ‘incremental, negotiated solutions that work’ (ibid)

-

A pessimistic perspective, stating that scientific knowledge will be exploited to legitimate (still) normative, political positions

All three interpretations refer to the complicated relation between knowledge and decision-making, that is, knowledge and power. The optimistic interpretation is close to the straightforward conception of ‘speaking truth to power’ (for a discussion of the concept, see Wildavski [1979] 2007; Jasanoff 1990). Such a linear understanding of the knowledge relation presupposes that ‘truth’ can be fed into the political system and translated into political decisions. A relation of this type would render think tanks and public policy institutes almost irrelevant, since scientific knowledge would be of immediate instrumental use (Stehr 2017). However, more complex approaches, notably sociological system theory, reject such a simple conception. In their view, ‘science’ and ‘politics’ represent distinct subsystems of society. Societal subsystems are not only an expression of a distinct division or remit of society but they represent specific zones, each following a distinct internal logic. System theorists speak of different ruling codes. The internal logic of the political subsystem is ‘power’ while the subsystem of science is governed by the ruling code of ‘truth’ (Grundmann and Stehr 2012, p. 2, Luhmann 1992, p. 284). Accordingly, the act of speaking truth to power is to conduct a conversation in a foreign language.

Even if system theory can be criticised for over-simplifying the complex social context, the importance of translating knowledge into something that can be used in the political arena persists. In consequence, two questions have to be answered. First, one has to ask how the translation process is conceptualised in the three perspectives on the knowledge-power relation outlined above. Second, one needs to analyse whether think tanks can be depicted as translators or ‘switchboards’ (Stone 1996, p. 95). The combination of these models of the translation process and the actual strategies of the translators eventually allows for locating think tanks in the knowledge-politics relation.

Translating Truth to Power?

The respective conception of these translation processes provides a criterion for the three interpretations found in the literature. Essentially, proponents of linear-rational models simply neglect the necessity of a translation process at all: ‘A science-based solution will be agreeable to warring parties, since it transcends the ideological […] differences’ (Grundmann and Stehr 2012, p. 6). To take the metaphor further, proponents of the rational model assume the political realm will eventually learn the language of science. From this perspective, ‘knowledge-based’ decision-making leads to a rationalisation of politics. Politicians turn into receivers of the best scientific knowledge available on which they base their decisions. Any increase in scientific consulting can only stem from a growing demand for expert advice to formulate adequate reactions to the complex challenges of modern societies. All that experts can (or have to) do is to feed their knowledge into the policymaking process. However, such simple conceptions are of limited practical use. Even if the (fundamental) philosophical and epistemological problems associated with ‘scientific truth’ (cf. Ruser 2015) are neglected for the moment and if situations in which rivalling knowledge claims are competing for acceptance in the political arena are ruled out, the idea that policymakers willingly subordinate their decision-making power to scientific truth is unrealistic and (with regard to the legitimacy of the decisions actually made) alarming at the same time.

The rationalist concept is contested by what Grundmann and Stehr (2005, pp. 7–8) call a pragmatic approach. In this view, politicians will not happily surrender normative positions to the superiority of scientific knowledge but may consider it (among others) in their business of ‘muddling through’ (ibid.). From this perspective, the translation of scientific knowledge must enable politicians to identify ‘useful knowledge’ and help include it into working political solutions

The linear-rational and the pragmatic models share a common view on the functionality of the knowledge provided by experts. From both perspectives, knowledge seems to be the opposite of ‘ignorance’ understood as the ‘absence or void where knowledge has not yet spread’ (Proctor 2008, p. 2). While in the rationalist model scientific knowledge ‘rushes in’ (ibid.:5) and dictates political action and in the pragmatic model decision-makers pick and choose advice in order to overcome the problems posed by ignorance, the third perspective mentioned above paints a much darker picture. In this view, ‘knowledge’ can be exploited in order to back long-held (normative) views. In particular, in democracies, where political decision-making needs to consider public sentiments, ‘deliberately engineered’ ignorance (ibid.:3) can serve as a ‘strategic ploy’ to preserve the status quo and legitimate political non-decision. Inaccurate or outright false translation not only may happen but can be in the interest of the receivers of the translation: The manufacturing of doubt, the fostering of ‘impressions of implacable controversy where actual disputes are marginal’ (Mirowski 2013, p. 227), can develop into a valuable service provided by a certain type of think tank. The service could be labelled ‘applied agnotology’ owing to the term ‘agnotology’ introduced by Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger (2008).

Agnotology, as used here, was coined by linguist Iain Boal and refers to three different states of ignorance: (1) the native state understood as something inferior ‘knowledge grows out of ignorance’ (Proctor, op.cit.:4), (2) ignorance as the result of selective choice—one opts to look for answers ‘here rather than there’ (ibid.: 7) and, most important for our purposes, (3) ignorance as an active construct or, as mentioned above, as a strategic ploy (ibid.:8–9). The term ‘agnotology’ points towards the fact that ignorance must not necessarily be the precursor of knowledge. Consequentially ‘science’ may not be portrayed as the natural enemy of ignorance.

Perhaps the most prominent example for such ‘agnotological’ practices is the US American climate politics. Philip Mirowski (op.cit.) provides empirical evidence that conservative policymakers and pressure groups align with suitable researchers and ‘experts’ not so much to defeat climate science but to preserve the political status quo by prolonging public dispute. Mirowski speaks of a joint effort to ‘muddy up the public mind and consequently foil and postpone most political action and (…) to preserve the status quo ante’ (ibid.:226). As proof, he recalls a memo of Frank Luntz to the Republican Party in the USA:

The scientific debate remains open. Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of certainty a primary issue in the debates (Luntz, cited in Mirowski, op.cit:227)

Aaron McCright and Riley Dunlap have come to similar conclusions. In a series of studies, they were able to demonstrate how conservative think tanks and special interest groups managed to prevent pro-environmental decision-making in the USA by challenging knowledge-based advice through the mobilisation (or manufacturing) of scientific dissent (McCright and Dunlap 2010, pp. 105–106; also McCright and Dunlap 2011; Dunlap and Jacques 2013; McCright and Dunlap 2015). These examples show that scientific expertise must lead neither to a rationalisation of the decision-making process nor to the reduction of ignorance. Since scientific knowledge is by definition preliminary (Popper [1935]1992) or ‘contested’, political non-decision can be promoted by manufacturing scientific dissent: The actual making of an informed decision is postponed until scientific consent is reached, turning actual or alleged scientific controversy into a political weapon. In a sense, this can be treated as a specific case of transforming scientific knowledge into political ‘usable knowledge’ (Grundmann and Stehr 2012, p. 12) by focusing on the process of scientific knowledge production.

Think Tanks as Translators

One possible explanation for the prominence of Washington-based think tanks since the 1970s and their more recent global spread is the increased demand for one of the aforementioned ‘translation service’. The US American system could then not only be thought of as a frontrunner for offering a market for political expertise; it could also be described as an institutional environment that is particularly well suited for all kinds of knowledge translators. This hints at the importance of environmental factors to explain think tank behaviour.

It is important to locate the respective position of think tanks in existing policy networks and analyse their ability to find a niche in the knowledge production system to explain the success or survival of think tanks. The ability to find a place in a specific system is closely related to the question on which model of exerting influence works best for a particular type of think tank. Thomas Osborne distinguishes between two ideal types of political influence. First, an advisory or leverage model in which personal or professional reputation is directly translated into public credibility and subsequently into political authority (Osborne 2004, pp. 433–434). Second, a ‘brokerage model’ in which influence is exercised if ‘vehicular ideas [are] brokered between parties, designed to enhance particular kinds of outcome’ (ibid.:434).

The initial step to develop a conceptual framework of strategic think tank behaviour is to distinguish between types of think tanks. The second step is then to consider their respective institutional environments (cf. Braml 2006; Thunert 2004). For developing a think tank typology, one can rely on established models (Weaver 1989) and, additionally, raise the question on how ‘ideal-type’ organisations correspond with the aforementioned models of exerting influence. Subsequently, the framework can be refined in two respects. First, following Campbell’s theoretical considerations (1998), distinct discursive levels and discursive zones can be distinguished to improve our understanding of how think tanks influence public deliberation and policymaking. Second, taking into account distinct (but idealised) institutional environments or ‘knowledge regimes’ (Campbell and Pedersen 2011, 2014) allows evaluating which organisational strategies prove to be successful under specific circumstances.

Types of Think Tanks

Defining what a think tank actually is proves to be difficult because of the organisational diversity, range of objectives or attitude towards practices and standards of scientific research. A practical solution to this problem is to distinguish between different types of think tanks. A prominent attempt to formulate such a typology, which takes into account different patterns of recruitment, funding, output and audience, can be found in Weaver (1989). He differentiates between ‘Universities without Students’ (UWS) and advocacy think tanks. UWS ‘tend to be characterised by heavy reliance on academics as researchers, by funding primarily from private sector […], and by book-length studies as the primary research product’ (Weaver 1989, p. 564). The purpose of this type of think tank is to provide scientific advice to their clients and contribute to the shaping of the ‘climate of elite opinion’ (Weaver 1989, p. 564). UWS as well as ‘contract research organizations’ (ibid.: 566)—which compile scientific reports for government agencies/contractors—maintain the high standards of academic inquiry and can be labelled ‘academic think tanks’. Accordingly, researchers working in ‘academic think tanks’ should come close to what Roger Pielke, Jr. describes as ‘science arbiters’ (Pielke 2007, p. 16). Outlining a model that comprises four idealised roles of science and the corresponding roles scientists can play in democracies, Pielke distinguishes between ‘pure scientists’ (who refuse to consider any practical consequences of their research) and science arbiters, who ‘recognise that decision-makers may have specific questions that require the judgment of experts’ (ibid.). The strategy of choice for academic think tanks should resemble the abovementioned ‘leverage model’ (Osborne 2004, pp. 433–434): The individual prestige of its researchers, derived from the authority of science, allows these organizations to formulate policy blueprints and ‘objective’ assessments and speak with the ‘authority of science’.

In contrast, advocacy think tanks ‘combine a strong policy, partisan or ideological bent with aggressive salesmanship and an effort to influence current policy debates’ (Weaver 1989, p. 567). Weaver’s depiction suggests that advocacy think tanks, in contrast to academic think tanks, should employ a brokerage model. According to Weaver (op.cit.:568–569), think tanks can be a ‘source of policy ideas’, function as evaluators of policy proposals and programmes, provide skilled personnel and be a source of ‘punditry’ for the media. Therefore, one should expect think tankers of this kind to differ considerably from the rather passive ‘science arbiter’. In the terminology of Pielke, advocacy think tanks attract ‘issue advocates’, that is, scholars who focus ‘on the implications of research for a particular political agenda […]’ and align themselves ‘with a group (or a faction) seeking to advance its interests through policy and politics’ (Pielke 2007, p. 15). In sum, advocacy think tanks differ from their more academic counterparts with regard to the self-conception of its staff and the principal model to exert political influence.

However, is must be stressed that the scientific character (or at least a semblance of it) takes centre stage for all types of think tanks. While all claim to speak with scientific authority, the attitude towards the standards of academic research varies considerably between academic and advocacy think tanks (cf. Weaver 1989; Stone 2004; Kern and Ruser 2010). Taken to the extreme, ‘advocacy’ could be defined as readings to balance the adherence to the standards of good scientific practice against the principles of pre-existing normative ideas.

Towards a Framework for Analysing Think Tanks

Distinguishing between different types of think tanks is a necessary first step to analyse the impact of knowledge and knowledge provision on public deliberation. The ‘significance of knowledge is indeed growing’ (Stehr and Meja 2005, p. 15); hence, think tank typologies are crucial to differentiate between different roles of knowledge in general and scientific knowledge. To assess the impact of think tanks more precisely, hence, it is essential to take into account the context in which they operate. This in turn requires a more sophisticated model of political discourses and the role knowledge can play. Moreover, a comprehensive framework should focus on the respective institutional setting which channels access to decision-makers or the media and, more generally speaking, ‘sets the tone’ for the provision of knowledge and consulting.

John Campbell’s conceptualisation of different types of ideas (1998) and their possible effects on policymaking can meet the first requirement. John Campbell’s and Ove Pedersen’s model of ‘knowledge regimes’ (2011, 2014) provides a suitable starting point for the second, a systematic investigation of respective institutional context think tanks have to operate in.

Diane Stone describes think tanks as ‘switchboards through which connections are made’ (Stone 1996, p. 95). This depiction fits in the understanding of think tanks as translators but simultaneously begs the question of which connections are established. The notion of ‘bridging the gap’ between knowledge and politics can refer to the process of political consulting in the literal sense. Knowledge is provided for policymakers to shape political action. This connection can either be straightforward, that is policies are directly shaped along experts’ advice, or represent a more general understanding of how things should be done shared by policymakers and the members of the scientific community. Alternatively, the bridging of the knowledge gap may involve a form of public engagement. The provision of expertise can aim at helping people to ‘make sense’ of complex situations and to sort out what not so much what is ‘thinkable’ or ‘appropriate’ or ‘acceptable’.

John Campbell’s ‘typology of ideas’ (1998) allows distinguishing between these different forms of linking knowledge and politics. Table 1 below presents four distinct effects of political ideas. Such ideas, understood as the content of a translation of knowledge for politics, can influence decision-making as concepts in the foreground or as underlying assumptions in the background of policy debates. Moreover, they can be located at the cognitive or normative level. At the cognitive level, they can function either as programmes (foreground), that is they serve as policy prescriptions for the political elite necessary to formulate actual agendas, or as paradigms (background). In the latter case, they define the boundaries of ‘thinkable solutions’ for political decision-makers. Likewise, at the normative level, they can provide frames suitable for legitimising policy solutions or public sentiments constraining the range of legitimate solutions.

Campbell’s model can be applied to derive some first hypothesis of think tank behaviour. With regard to the think tank typology outlined above, it can be assumed that academic think tanks will most likely try to provide assistance in the formulation of programmes and frames. This hypothesis can be further refined when it comes to contracted (demand-driven) research. Existing paradigms and public sentiments influence what clients consider either useful or legitimate and constrain the scope and the aim of an offered contract accordingly. A contracted academic think tank should serve its clients’ needs best by providing evidence in support of favoured political paradigms. The comprehensiveness of their research makes it less suitable for charting specific political action but may affect the range of solutions considered useful by politicians. In contrast, advocacy think tanks will primarily attempt to exert influence on the normative level. By providing expertise to legitimise policy solutions, these organisations can create or alter frames available to policymakers and influence public sentiments in a way that the solutions offered by advocacy think tanks are considered legitimate.

The ‘typology of ideas’ is instrumental in distinguishing between different goals, targets and subsequently distinct strategies of academic and advocacy think tanks respectively. However, the ‘interaction between ideas and institutions’ (Campbell and Pedersen 2011, p. 167), that is, an exploration of the ‘environmental conditions’ which influence the prospects of these think tank strategies, has thus far been left out of the picture.

The above can be complemented by including the Campbell and Pedersen model of ‘knowledge regimes’. The initial aim of their theoretical work is to ‘better understand how policy-relevant knowledge is created’ (ibid.:168) by combining insights from research on policymaking and comparative studies on production regimes. They draw in particular on the ‘varieties of capitalism’ approach by Hall and Soskice (2001) to distinguish two types of production regimes: ‘liberal market economies’, structured by markets and corporate hierarchies, on the one hand and ‘coordinated market economies’ on the other. In the latter case, economic activities are not dominated by the rules of free markets but are embedded in elaborate systems of corporatist bargaining and regulation (including state intervention) (ibid.:170). With regard to policymaking regimes, they follow Katzenstein’s (1978) distinction between ‘centralised, closed states’ (CCS) and ‘decentralised, open states’ (DOS). Policymaking in CCS is located in few arenas, largely insulated from external influences. In contrast, policymaking in DOS is more exposed to external influence, as authority is likely to be shared or delegated. By combining these two strands of theoretical thought, Campbell and Pedersen get four ideal-type knowledge regimes [Table 2]. These knowledge regimes differ with regard to the overall impact of ideas (competitive vs. consensus-oriented systems) and in terms of which types of research units and think tanks are influential (cf. Campbell and Pedersen 2011, pp. 171–172).

Market-oriented and politically tempered knowledge regimes can be labelled as ‘marketplaces for ideas’ (where it literally pays off to pay for think tank advice). Competition dominates the process of knowledge production and distribution, enabling consultancies to engage in agenda setting and the provision of support for political positions. Selling one’s ideas is important and creates advantages for advocacy organisations engaged (and staffed with the necessary ‘issue advocates’) in ‘aggressive salesmanship’ (Weaver 1989, p. 567). In contrast, consensus-oriented and statist-technocratic knowledge regimes are rather hostile environments for scientific advocacy. Here, the provision of expertise is guided by the principle of impartiality and is moderated by an overall orientation towards political consensus. Instead of asking whether ‘Germany’s market-place of ideas [will] ever resemble America’s’ (The Economist, cited in Braml 2006, p. 223), one has to analyse the impact of a specific ‘knowledge regime’ on the production and distribution of scientific knowledge on the process of political decision-making and public discourses alike. Accordingly, the spread of think tanks has to be studied with regard to the specific rules and institutions that shape their organisational structures and strategies for exerting influence.

Conclusion

Think tanks have attracted the attention of scholars and policymakers alike. The global spread of think tanks, which has been described as an indicator for the increased importance of (scientific) knowledge, is not necessarily signalling a general trend towards more ‘rational’ knowledge-based decision-making.

In this contribution, it has been argued that for a proper understanding of think tank strategies and their impact on public deliberation and policymaking, it is necessary to distinguish between different types of think tanks and modes of exerting influence. Furthermore, political discourses have to be dissected to determine whether think tanks aim at influencing decision-makers or the public and are best suited to infuse knowledge to find a suitable solution or whether they are content with influencing public sentiment. Finally, the specific institutional setting, the respective knowledge regime think tanks have to work in, has to be considered. Think tanks not only shape the world around them, but are in turn themselves shaped and constrained.

But what is this model good for? What to think about think tanks? Fundamentally, the model serves two purposes. First, it allows comparing think tank strategies at the international level. Rather than accepting the exceptional ambiguity of think tanks with a shrug, comparative studies can employ this model to gauge what it means to operate as a think tank in different contexts. Instead of stating a global spread of organisations conveniently subsumed under a vague umbrella term, the theoretical model can help describe what kind of creature think tanks actually are and how they are shaped by their habitats.

Second, and perhaps even more importantly, the model can be applied to analyse the different outcomes of think tank activities. For instance, advocacy think tanks in the USA are seemingly successful in spreading and supporting climate sceptic positions. Why is there no similar development in, say, European or Asian countries? Is it because American think tanks are better paid?

The proposed model does not promise to provide simple answers to such important questions. However, it promises to help end a theoretical stalemate, which had been the source of frustration in think tank research.

Notes

A good example is the field of international politics and security policy. Not least because of the significant successes of ‘big science’ projects and ‘operations research’ units during World War II (cf. Fortun and Schweber 1993), scientific knowledge was and is in high demand in security politics. However, the production of applicable knowledge and the giving of expert advice have not been a priority of universities in many Western European and North American countries. This opened a niche for some of the most renowned think tanks, like the RAND Corporation or the Brooking Institution in the USA, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) in Sweden, Chatham House in the UK or the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

References

Abelson, D. E. (2009). Do think tanks matter? Assessing the impact of public policy institutes. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Böhme, G., & Stehr, N. (1986). The knowledge society: the growing impact of scientific knowledge on social relations. Dordrecht: D.Reidel.

Braml, J. (2006). U.S. and German think tanks in comparative perspective. German Policy Studies, 3(2), 222–267.

Campbell, J. (1998). Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society, 27, 377–409.

Campbell, J. L., & Pedersen, O. K. (2011). Knowledge regimes and comparative political economy. In D. Béland & R. Cox (Eds.), Ideas and politics in social science research (pp. 167–190). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, J. L., & Pedersen, O. K. (2014). The national origins of policy ideas: knowledge regimes in the United States, France, Germany, and Denmark. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cockett, R. (1994). Thinking the unthinkable: think tanks and the economic counter-revolution, 1931–1983. London: HarperCollins.

Dixon, K. (1998). Les évangélistes du marché: Les intellectuelles britannique et le néo-libéralisme. Paris: Raison d’agir.

Dunlap, R. E., & Jaques, P. J. (2013). Climate change denial books and conservative think tanks: exploring the connection. Am Behav Sci, 57(6), 699–731.

Falk, S., Reheld, D., Römmele, A., & Thunert, M. (2006). Handbuch Politikberatung. VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden.

Fortun, M. A., & Schweber, S. (1993). Scientists and the legacy of World War II: the case of operations research (OR). Soc Stud Sci, 23, 595–642.

Gosling, F. G. (1999). The Manhattan Project. Making the atomic bomb. Washington D.C.: United States Department of Energy.

Grundmann, R., & Stehr, N. (2005) Knowledge. Critical Concepts. London, New York: Routledge.

Grundmann, R., & Stehr, N. (2012) The Power of Scientfic Knowldge. From Research to Public Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundation of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hames, T., & Feasey, R. (1994). Anglo-American think tanks under Reagan and Thatcher. In A. Adonis & T. Hames (Eds.), A conservative revolution? The Thatcher-Reagan decade in perspective. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hird, J. A. (2005). Power, knowledge and politics. Washington D.C: Georgetown University Press.

Jasanoff, S. (1990). The fifth branch. Science advisers as policymakers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Katzenstein, P. J. (1978). Between power and plenty: foreign economic policies of advanced industrial states. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Kern, T., & Ruser, A. (2010). The role of think tanks in the South Korean discourse on East Asia. In R. Frank, J. E. Hoare, P. Köllner, & S. Pares (Eds.), Korea 2010. Politics, economy and society (pp. 113–134). Leiden: Brill.

Luhmann, N. (1992). Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2003). Defeating Kyoto: the conservative movement’s impact on U.S. climate change policy. Soc Probl, 5(3), 348–373.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2010). Anti-reflexivity: the American conservative movement’s success in undermining climate science and policy. Theory, Culture, and Society, 27(2–3), 100–133.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob Environ Chang, 21, 1163–1172.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2015). Challenging climate change: the denial countermovement. In R. E. Dunlap & R. Brulle (Eds.), Climate change and society: sociological perspectives (pp. 300–332). New York: Oxford University Press.

McGann, J. G. (2010). The global go-to think tanks. Pennsylvania University: The Think Tans & Civil Society Program.

McGann, J.G. (2016). 2015 global go-to think tanks report. TTSCP Global Go To Think Tanks Index Reports, 10.

McGann, J. G., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Comparative think tanks, politics and public policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

McGann, J. G., & Sabatini, R. (2011). Global think tanks: policy networks and governance. London: Routledge.

McGann, J. G., & Weaver, R. K. (2000). Think tanks and civil societies. Catalysts for ideas and action. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Mirowski, P. (2013). Never let a serious crisis go to waste: how neoliberalism survived the financial meltdown. London: Verso.

Misztal, B. A. (2012). Public intellectuals and think tanks: a free market of ideas? International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 25, 127–141.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2001) Re-Thinking Science. Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty. Polity Press, Oxford.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of doubt: how a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York: Bloomsbury.

Osborne, T. (2004). On mediators: intellectuals and the ideas trade in the knowledge society. Econ Soc, 33(4), 430–447.

Pielke, R. (2007). The honest broker. Making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Popper, K. ([1935] 1992). The logic of scientific discovery. London and New York: Routledge.

Proctor, R. N. (2008). Agnotology: a missing term to describe the cultural production of ignorance (and its study). In R. N. Proctor & L. Schiebinger (Eds.), Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Proctor, R. N., & Schiebinger, L. (2008) Agnotology. The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ricci, D. (1993). The transformation of American politics: the new Washington and the rise of think tanks. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ruser, A. (2013) Environmental Think Tanks in Japan and South Korea. Trailblazers of Vicarious Agents? In M. Carmen (Eds.) Nature, Environment and Culture in East Asia. The Challenge of Climate Change. Climate and Culture Series. (pp. 319–351). Leiden: Brill.

Ruser, A. (2015) Perspectives of and Challenges for a social philosophy of Science. Epistemologyand Philosophy of Science, 45(3), 54–64.

Sheingate, A. (2016). Building a business of politics: the rise of political consultancies and the transformation of American democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stehr, N. (2004). Introduction: a world made of knowledge. In N. Stehr (Ed.), The governance of knowledge (pp. ix–xxvi). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Stehr, N., & Meja, V. (2005). Society and knowledge: contemporary perspectives in the sociology of knowledge and science. London: Transaction Publishers.

Stehr, N., Ruser, A. (2017)‚ Social scientists as technicians, advisors and meaning producers. Innovation: the European Journal of Social Science Research, 30(1), 24–35.

Stone, D. (1996). Capturing the political imagination. Think tanks and public policy. London: Frank Cass.

Stone, D. (2004). Introduction. In D. Stone & A. Denham (Eds.), Think tank traditions: policy research and the politics of ideas. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Stone, D., & Denham, A. (2004) Think Tank Traditions: Policy Analysis across Nations. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Thunert, M. (1999). Think Tanks als Ressourcen der Politikberatung: Bundesdeutsche Rahmenbedingungen und Perspektiven. Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen, 12(3), 10–19.

Thunert, M. (2004). Think tanks in Germany. In D. Stone & A. Denham (Eds.), Think tank traditions: policy research and the politics of ideas. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Weaver, K. (1989). The changing world of think tanks. Political Science and Politics, 22(3), 563–578.

Weidenbaum, M. (2010). Measuring the influence of think tanks. Social Science And Public Policy, 47, 134–137.

Wildavsky, A. ([1979] 2007) Speaking truth to power. The art and craft of policy analysis. London: Transaction Publishers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruser, A. What to Think About Think Tanks: Towards a Conceptual Framework of Strategic Think Tank Behaviour. Int J Polit Cult Soc 31, 179–192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9278-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9278-x