Abstract

When seeking to understand past social dynamics, archaeologists often turn to architecture. This paper presents a diachronic study of the architecture of the central Mexican Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla to illuminate how the built environment may be used to control people and transform individual and community identity. Data derived from archaeological, ethnographic, and historical research together provide a rare longitudinal and detailed dataset spanning the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Using an analysis that combines space syntax and phenomenology, I find that a mid-nineteenth century renovation of hacienda architecture reflected a contemporary national program of modernization directed at redefining rural labor and community structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How do you control the productive energy of a group of people? This question transcends time and place, and all complex civilizations have had to grapple with it. The way a society chooses to answer this question has a profound impact on its social organization and the everyday lives of its citizenry. Methods of controlling labor affect more than just economics; they shape the ways people relate to each other and structure their belief systems.

Archaeologists working on historic period sites throughout the world have identified architectural designs that were driven by the need to control a subservient population (Baxter 2012; Beaudry 1989; Casella 2001; Chapman 1991; Delle 1999, 2009, 2014; Epperson 1990; Fellows and Delle 2015; Funari and Zarankin 2003; Jamieson 2000; Johnson 1996; Joseph 1993; Leone 1984, 1995; Meyers 2012; Meyers and Carlson 2002; Miller 1988; Mrozowski 1991; Mrozowski et al. 1996; Nashli and Young 2013; Pogue 2002; Potter 1994; Potter and Leone 1992; Shackel and Palus 2006; Singleton 2001; Upton 1983; Whelan and O’Keeffe 2014). They have demonstrated that architecture, whether domestic or industrial, is embedded with social meanings that shape the behavior of its occupants and communicate with the outside world (Blanton 1994; Bourdieu 1973; Glassie 1975; Hillier and Hanson 1984; Rapoport 1969). Further, archaeologists have shown how designs of both public and private spaces were often intended to exhibit, maintain, and perpetuate discipline. During the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries especially, this intention was derived from Baroque theories of power which, in the words of Mark Leone, “attempted to establish stratified social hierarchies by creating environments that proclaimed a natural law dependent on divinely ordained, natural hierarchies” (Leone 1995: 255).

While many have discussed the ways in which architecture has been used to control people, the example of a Mexican hacienda allows us to explore how architecture may be used not only to control labor but to redefine the very identity of the laborers. Throughout its history, Mexico’s upper classes explicitly sought to transform the ways that the indigenous people of Mexico understood themselves and their relationship to community and society. This examination of the diachronic changes in the architecture of a rural Mexican hacienda sheds light on just how Mexico’s elite went about implementing plans to create a unified citizenry.

The study of Mexican haciendas has become a subfield in the burgeoning field of Mexican historical archaeology, with emphasis often being placed on the ways the dominant labor/power structure impacted indigenous communities during the colonial (1519–1810) and national (1810–1910) periods (Alexander 2003, 2004, 2012; Benavides Castillo 1985; Fournier-Garcia and Mondragon 2003; Hernández Álvarez 2014; Jones 1981; Meyers and Carlson 2002; Meyers 2005, 2012; Meyers et al. 2008; Newman 2013, 2014a, b; Sweitz 2012). Though the hacienda has been well studied, few details are known about the architecture of early haciendas; the bulk of our information comes from the standing ruins constructed during the latter half of the nineteenth century (Charlton 1986; see also Jones 1978, 1981).

This paper primarily seeks to address the role of hacienda architecture in shaping the behavior of hacienda workers during the latter half of the nineteenth century but, because this is a diachronic study, also draws on rare data sets from the earlier, less-studied colonial period to provide a baseline of comparison. The data discussed here were derived from work done between 2003 and 2008 in Western Puebla’s Valley of Atlixco at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla and in its associated descendant communities. In the following pages, I apply a space syntax analysis (following Hillier and Hanson 1984) in conjunction with a phenomenological exploration of San Miguel Acocotla’s contemporary architectural ruins to illuminate the social processes shaping the landscape during the latter half of the nineteenth century. I situate this moment in a longer history by using two rare archival descriptions of the hacienda’s colonial and early-national period architecture in conjunction with archaeological research. I describe how a late-nineteenth century architectural renovation was implemented to increase worker productivity, reform social organization and worker experience, and contribute towards the project to remake Mexico into a modern, industrialized, capitalist nation.

History of Research

The Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla is located in the valley of Atlixco in the western portion of Mexico’s state of Puebla (Fig. 1). The ruins of the hacienda’s casco (architectural core of the hacienda property) sit at the edge of the valley floor approximately 1800 m above sea level and just east of a line of hills that run south from the summit of the volcano Popocatépetl. The region has a temperate climate with a rainy season that lasts from late May through late September.

Dr. Harold Juli began the research discussed here in 2001 with an informal survey of a dozen haciendas in the state of Puebla. He ultimately chose Acocotla for a multi-year, interdisciplinary project because, in addition to its ruined but identifiable architecture (Fig. 2), it is situated only 2 km north of a small community inhabited today by descendants of the hacienda’s workers. In 2003, Dr. Juli began an ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological study exploring patterns of daily life and memories of hacienda labor with members of that village (Juli 2003). The study continued for the next 4 years with help from me and students from the University of the Americas, Puebla (Juli et al. 2006; Newman 2010, 2013, 2014a, b; Newman and Castillo Cardenas 2013; Newman and Juli 2008).

Historical research conducted in national, state, and local archives demonstrated the importance of archaeological research. In the hundreds of pages of transcriptions we collected, we found that the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla’s 25 owners were well-documented, and the hacienda’s workers, ranging in number from 10 to 121 at any given time, were fleetingly visible (Newman 2014a, b; Romano Soriano 2005). Our best information came from irregular censuses of the hacienda’s workers taken during the latter half of the nineteenth century, but the information presented in these documents offered only the barest demographic sketch of life in the worker’s quarters (Newman 2013, 2014a, b). Quite quickly, it became clear that archaeological research would offer new avenues into developing an understanding of the day-to-day experiences of Acocotla’s indigenous workers.Footnote 1 As a result, we developed a parallel archaeological and architectural study at the Hacienda Acocotla’s now-ruined casco to explore the quotidian living and working conditions of the hacienda’s indigenous workers.

During the summer of 2005 and the winter of 2007, we carried out two seasons of archaeological excavations over the course of a total of 12 weeks, as well as an intensive study of Acocotla’s standing architecture (Juli et al. 2006; Newman and Juli 2008). Excavations were centered on the worker’s quarters, or calpanería, and the field fronting that structure. The initial 2005 4-week season focused on the calpanería and included detailed architectural recording, surface survey, and test excavations; we also conducted an architectural study of the entire casco. The results led us to embark on 8 weeks of excavations, again concentrated in the area of the calpanería, in 2007. During this second period, we excavated five randomly chosen rooms in the calpanería and an extensive midden, and we completed the excavations of a large, randomly chosen unit begun during the final week of our 2005 field season (Fig. 3). We conducted all of the excavations using 6.35 mm (1/4 in.) mesh to screen soil. Units were excavated in 10 cm arbitrary levels constrained by natural and cultural stratigraphic breaks (where identifiable). The surface survey and excavations resulted in the recovery of 87,142 artifacts and ecofacts. Dates derived from the artifacts place the majority of contexts in the second half of the nineteenth century, though a few contexts may date to as early as the end of the eighteenth century. We also recovered a handful of prehistoric artifacts that we interpreted as either intrusive or secondary deposits (Juli et al. 2006; Newman 2010, 2014b; Newman and Juli 2008).

The Colonial Hacienda

Haciendas were established throughout Mexico soon after the arrival of the Spaniards ostensibly for economic purposes, but they were also prime loci for the control and assimilation of indigenous populations (Chevalier 1963; Gibson 1964; Knight 2002; Newman 2013, 2014a, b, 2016; Van Young 1983; Wolf 1969; Wolf and Mintz 1957). By 1532, Spanish settlers were colonizing the Valley of Atlixco, enmeshing it in New Spain’s economy (Gerhard 1993: 56; Paredes Martínez 1991: 40). Atlixco’s pre-conquest populations were relatively low thanks to regional political disputes (Plunket 1990; Dyckerhoff 1988; Gerhard 1993; Paredes Martínez 1991). What population there was dropped precipitously under Spanish rule from an estimated 35,000 families when Cortes first visited in 1519 to approximately 5000 by 1570, and, another 75 years later, to a nadir of approximately 2500 (Gerhard 1993: 57). Unlike many other areas of Mexico, Atlixco’s populations did not rebound significantly; in 1803, Indian tributaries numbered only 6153 (Gerhard 1993: 57), a figure that represented less than 20 % of the estimated pre-conquest population.

The combination of low population levels, geographic location, and climate made the valley of Atlixco an attractive place for early Spanish investment. Following a severe plague and drought in 1576, the price of grains skyrocketed in Mexico City while meat prices plummeted (Knight 2002: 77). As the financial incentive to farm cattle disappeared, the Spanish viceroyalty offered inducements to Spaniards willing to establish wheat haciendas (Chevalier 1963: 64). These Spaniards found the valley of Atlixco ideal for the production of wheat. Land was readily available, the climate was kind for the production of grains, and the location, between Mexico City and Puebla, was ideal for getting goods to market. By 1610, approximately 393 haciendas had been established in the Valley (Paredes Martínez 1991). Ultimately, Atlixco became so important to New Spain’s economy that it has been called, “the granary of New Spain’s Viceroyalty” (Morales 2006). The popularity of the valley meant, however, that getting, keeping, and controlling a workforce was a perpetual challenge (Newman 2013, 2014a). Thus, in the first 100 years of Spanish settlement, the social, economic, and physical landscape was significantly remade.

The early settlers used the physical space of the hacienda to accomplish two intertwined goals (though as often as not, these goals were aspirational rather than realized). First, haciendas became a space to assimilate the local population to Spanish ways of life. Central to the program of assimilation was the conversion of New Spain’s indigenous population to Catholicism, and the casco of New Spain’s haciendas allowed for a physical structure within which this project could be implemented. Elsewhere in New Spain, the transformation of physical space was understood to be a method for transforming social behavior, for generating a new habitus, and the hacienda must not have been exempt from this project (Hanks 2010: 1–7). But, of course, most Spaniards came to New Spain seeking more than souls for the Church. Many sought wealth and social advancement, as well. Thus, haciendas also acted as a structure, both physical and social, for the exploitation of labor and the extraction of surplus.

A study of the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla demonstrates how these two intertwined goals of proselytization and economic development were made physically manifest in the architecture of the colonial hacienda. We don’t know what Acocotla looked like when it was first established, but a rare assessment written just a century later in 1686 describes the hacienda and its holdings:

The residential houses include a living room and a bedroom with roof beams and three doors with locks, and on top of it, a granary made of zacate [dried cornstalks or grass; hereafter thatch], another low granary made of adobe and covered with thatch, with its door and lock. An adobe kitchen covered with thatch. Another big bedroom next and to the north of the aforementioned kitchen made of adobe with its door and without key. Plus another new bedroom covered with thatch and with a door. A hen house made of earth and covered with thatch, with its door. Plus a bedroom made of brick and dirt upstairs with its door and key that goes inside the yard at the foot of the stairs of the upper granary. An oven made of bricks and covered with lime. A chapel dedicated to St. Michael covered with new beams and bricks on top, with its foundation of lime and stone and the walls made of adobe with the following adornments: an altarpiece of red and white satin with its woolen fringes, a chasuble made of white satin, an alb of Juan [a type of fabric], an amice of the same, stole, manipule and cincture, altar tablecloths of Juan, a silver chalice and a golden paten, a mass book with its support, two wooden candleholders painted in gold, a metal wafer box, a small bell, a box where all the things mentioned are kept, an ara [consecrated stone used during mass], and a bag with its corporals, an altar cloth with white ends, a wooden cross painted gold and its cruets, a wooden sculpture of St. Michael, a wooden table, two chairs with black backs and one with a white back, the key to the doors of the chapel, fifty-five tamed ox for the plough, thirteen of which are old, two cows with seven calves of age, twelve yokes with twelve pairs of hemp ropes, two ear yokes, an old cart with three cuartas [a measurement of length equal to ¼ of a vara or approximately 8 inches], two iron holders for the cart, one arroba [measure of weight equal to 25 pounds] and sixteen pounds of iron in eighteen blocks, eight old hoes, two dozen old sickles, two axes, one long-handled, the other a smaller hatchet, a large chisel and an adz and an extra auger head, and a barrena [metal stick], twelve new helms and seven old, twelve new heads, a half forged fanega [stick for measuring dry products], and another one not yet forged, six shovels, sixteen stakes to make a corral, all with their metal tips, three lengths of agave rope, a reservoir lined with lime and stone.” (translation by author)Footnote 2

The greatest emphasis in this document—textual, architectural, and monetary—is placed on Acocotla’s chapel, something that highlights the role of the hacienda in assimilating local, indigenous populations and ensuring their active Catholicism (Fig. 4). Where description of the living areas is almost cursory, we are given extensive details about the chapel including what it is constructed out of—materials such as brick and stone that are significantly more expensive and substantial than the adobe and thatch living areas—along with details about the decoration and objects necessary to hold a Mass. These items were costly, and they included an altarpiece of satin, a silver chalice, and wooden candleholders and a cross, both painted in gold. Secondary importance is accorded the tools and livestock necessary for farming. From the number of oxen, to lengths of rope, to a reservoir, the assessment makes clear that the hacienda is an active agricultural business. In the seventeenth century, Acocotla’s importance is not in grand architecture, but in its ability to operate jointly as church and farm.

The Nineteenth Century Hacienda

Nearly 200 years after the seventeenth century account reported above, little had changed at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla. So many generations after the conquest, the historical moment of the casco’s utility as a tool of subjugation and social transformation had perhaps passed and the buildings fell into disuse. As the people of Mexico headed into the second half of the nineteenth century, however, new needs for social control and transformation would drive a redesign of Acocotla’s architecture.

In preparation for San Miguel Acocotla’s 1859 sale to one doña Ana Cristina Treviño de Ruelas, a surveyor recorded a detailed description of Acocotla’s architecture and filed it in the notarial archives in Puebla’s state capital. At this time, we see significant shifts in the valuation of the hacienda in terms of the social/monetary value placed on types of structures, but little architectural elaboration:

“The house is of two floors, the front faces east and it measures fifty six varas [46.93 meters] of latitude and fifty [49.01 meters] of longitude, and in this space there are the following things: roofed entrance with an arch, double-doors with windows, a yard with an outside manger, then a roofed stable over two arches, on the other side, a stairway to the roof. And doors to a big granary covered with bricks. Then follows a portal with five arches supported by brick columns that have deteriorated, in the two spaces mentioned, the covered stairwell, on the first landing, a door between floors, the second flight of stairs leads to a corridor with a brick window, a roof supported by five arches, a door leading to a living room, one of the doors leads to another, separate room with a window, and a door to another room with a door leading to the roof; back to the living room, another door leads to a small look-out and a door to the dining room; [the dining room has] two cupboards and two doors, one door leads to the corridor and the other leads to the kitchen with a high brazier, coal storage-space, a window and a cupboard, and another door that leads to a staircase that goes down to the hen house; back on the corridor, the other door leads to another room and a door to an granary that goes around the side of the yard; there is also a small room that serves as the carpenter’s shop; going out to the field in the same direction as faces the door to the hen house with a new flat roof, the threshing floor covered with bricks in bad shape; besides the house are two doors, one that goes to the straw room and the other to the granary; then follow the ruined earthen fences and five ruined rooms; the chapel and its burial ground with a tall fence, the belfry with a bell that weighs two arrobas [25 kilograms]. In the place where all the habitable rooms and offices that are part of the house end, the construction is all made of adobe with little lime and rock, all the construction is deteriorated because several walls have been burrowed by rats, most of the wood of the roofs, doors and windows are in the same shape and taking account of everything related, material costs and salaries of the workers, I value it at 5329 pesos.” (translation by author)Footnote 3

With this assessment in hand, doña Ana Cristina Treviño de Ruelas purchased the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla’s lands and buildings for 31,010 gold pesos. At the time of doña Ana’s purchase, the Hacienda Acocotla was in foreclosure, not an uncommon state for a Mexican hacienda, an institution commonly plagued by money troubles and general instability (Patch 1985: 22). When Teviño de Ruelas took possession of the property, the casco would have measured only about fifty meters by fifty meters square. As the assessment tells us, in those twenty-five hundred m2, the structure had two stories, spaces for living and working, a kitchen, a granary, stables, a threshing floor, a carpenter’s shop, and a chapel with a burial ground. In 1859, emphasis was on domestic rather than religious structures, but it seems that, architecturally, very little had changed since the earlier 1686 records were made; however, following doña Ana’s purchase, the Hacienda Acocotla entered a new era.

The sale price of the hacienda increased substantially between 1860 and 1885 from 31,010 to 42,851.95 gold pesos, and land holdings did not increase during this same period (Romano Soriano 2005). While some of the increase in price may be attributed to general inflation, some of the increase in sale price is probably due to improvements in the hacienda’s casco, which today measures more than 14,500 m2—an increase of 12,000 m2 over the space described in 1860. The 1860 description indicates that Acocotla’s casco had been uninhabited for some time. Though we don’t know with any certainty who was responsible for the architectural redesign, archaeological evidence recovered during our excavations in the calpanería indicate that the remodeling would have taken place during Doña Ana’s tenure; if nothing else, one imagines she would have wanted to evict the rats (Newman 2014a, b; Romano Soriano 2005).

The contrast between the archival accounts of Acocotla’s architecture, made fewer than 200 years ago, and what one sees on the ground now is impossible to ignore. Prior to 1860, the hacienda’s buildings seem to have centered on what is now the Patio del Limon (see Fig. 3). After 1860, however, Acocotla underwent drastic remodeling that made the structure more complex, a remodeling that would have created a highly controlled, hierarchical space.

Acocotla’s 5-m-high walls enclose a total of 14,632 m2 of living, administrative, and workspace in five patios and an 8122 m2 protected garden. Outside these walls, the hacienda’s architectural core also includes the calpanería, composed of thirty-four small rooms that would have each housed a family of workers, an open field in which these families would have conducted their domestic activities, a threshing floor, a chapel, a brick kiln, and a reservoir. Archaeological evidence from excavations in the calpanería indicated that the contemporary ruins of the hacienda were largely the result of a program of construction and expansion dating to after 1860 (Newman 2014a, b). Once again, the needs of the wealthy to redefine the identity and control the productivity of the poor were encoded in the architecture of the Hacienda Acocotla.

Nineteenth Century Pressures

Mexico’s century between the War of Independence and the Revolution (1810–1910) was dangerous and unstable. Elites struggled to maintain control over the economy and government. The poor felt their long-held control over basic subsistence and village independence slip from an ever-increasingly tenuous grasp as a result of political and economic struggles taking place on the national stage (Kanter 2008; Meyer 1973; Reina 1980; Tutino 1986, 2008; Van Young 1988). In 1814, owners of haciendas in the Valley of Atlixco wrote to the government to request forbearance in their fiscal responsibilities, citing attacks by “insurgents,” the payments they were required to make in support of the army, and lack of labor due to frequent epidemics resulting in the death of the Indians responsible for the haciendas’ agricultural activities as reasons for their request (Newman 2014a). Conditions in the region did not improve.

By 1859, when the hacienda was assessed in the document described above, evidence from the municipal archives shows that tensions ran high in the Valley of Atlixco. Many of Acocotla’s nineteenth century records deal with the responsibility of the hacienda owner to send men and horses to local authorities to assist in policing the area (e.g., AHMA 1842b, c, 1857b, 1860, 1863, 1867, 1871b, 1876c, d). Other documents speak frequently of robberies, kidnappings, and murders by and of the local populace (e.g., AHMA 1841 Footnote 4, 1855, 1857c, 1868a, 1869, 1876a, b, e, f). Fluctuations in the number of resident workers housed in the calpanería (housed as part of an agreement that they would be employed full time and year round) speak to either economic instability or the difficulty of maintaining a consistent worker population throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century (e.g., AHMA 1842a, 1844, 1853, 1854, 1857a, 1868b, 1870, 1871a, 1872a, b, 1884, 1889, 1893), a not uncommon issue in central Mexico during this period (Kanter 2008; Newman 2014a; Tutino 1986, 2008).

In 1876, Porfirio Diaz took control of Mexico through armed rebellion. One way or another, he would rule the nation for the next 30 years. His seizure of power ushered in a period of political stability, the “Porfiriato” (1876–1910), like none Mexico had experienced in its previous half-century of independence. However, this stability came at a price. Diaz instituted and accelerated processes of modernization that prioritized the ideals of industrial capitalism. The elite of Mexico, and the foreign investors they courted, believed they faced a profound challenge to quell instability and form Mexico into a modern “First World” nation.

Mexico’s indigenous laboring classes were neither good producers nor consumers. Visitors claimed that Mexico’s indigenous peoples were “too easily satisfied by just the basic necessities” (Ruiz 2014: 176). The poor worked just enough to live rather than to acquire and accumulate goods. If Mexico were to solve her problems, she had to create supply and demand. As “Gilded Age” investors from the United States and Europe flooded the country, Mexico’s rural landscape, and the indigenous communities that filled it, was forever altered.

Individuals like Ana Cristina Treviño de Ruelas and her hacienda manager, or mayordomo, would have had to contend with all of these challenges after she purchased the Hacienda Acocotla, and she would have been aware of the frequent financial failings of Acocotla’s prior owners. Faced with these problems and the crumbling, rat-infested ruins of Acocotla’s casco, doña Ana (or her mayordomo) restructured her business in the most concrete way possible. The redesign of the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla’s casco is the physical manifestation of the social tensions faced by rural landowners and workers alike.

And Acocotla was not a unique case. Though we don’t have details about the architectural renovations of other haciendas, we do know that the cascos at rural haciendas throughout central Mexico were becoming larger and more architecturally elaborate during this same period (Charlton 1986; Jones 1978). In reconfiguring cascos like Acocotla’s, owners like Doña Ana may have been attempting to bring order to a world in chaos while simultaneously increasing worker efficiency. Perhaps the mid-nineteenth century remodel of the hacienda’s buildings signified a reorganization of the hacienda’s workforce, as well as a shift in management paradigms.

The Syntax of Acocotla’s Casco

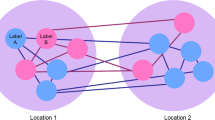

Doña Ana may have attempted to control her workers by manipulating architecture. Using the methods of space syntax, we can explore that possibility. Originally developed by architects as a quantitative tool to understand how the design of buildings and cities impact human interaction (Hillier and Hanson 1984), space syntax has been applied by numerous archaeologists working throughout the world to explore the ways social organization is reflected in architecture (e.g., Blanton 1994; Cutting 2003; Dawson 2002; Edwards 2013; Funari and Zarankin 2003; Jamieson 2000; Morton et al. 2012; Robb 2007; Smith 2007; Wernke 2012). Space syntax is essentially structuralist; the methodology assumes that the ways people move through space impacts their behavior, consciously and unconsciously (Cutting 2003: 3). Thus, space syntax is especially useful for understanding the ways that architecture can be used to control a population (Steadman 1996: 67). To highlight this social process, architecture is distilled to a simplified “justified access diagram” (or J-Diagram) composed of nodes on a tree.

Figure 5 presents just such a diagram of Acocotla’s post-1860 architectural space. Each circle, or node, represents a space, like a room or patio, and the connections between the nodes represent access paths (or barriers/points of control) such as doorways and hallways. This diagram ignores the length of hallways, the size of patios, or the number of locks on a door, and, in doing so, it highlights the difficulty of getting from one space to another in a way that might not necessarily be obvious on a more complex architectural plan.

Justified access diagram of the Hacienda Acocotla’s Casco. Numbers and letters correspond to the numbers and letters on the map of the casco (see Fig. 3). Green circles denote residential areas and red circles denote work areas

For example, it becomes clear that it is very easy to move from the outside of the hacienda into any of the calpanería rooms; only one doorway separates the outside world from the private family space inhabited by Acocotla’s workers. But at each successive “level,” it is just a bit harder to access the space than it was at the preceding level (Fig. 6; top). The most difficult access is the tower room (21), with the rooms surrounding the Patio del Limón coming in second. These spaces would have been the most private, safest, and most easily controlled.

The manager’s office was placed in the space between the “work” areas of the hacienda and the living areas of the hacienda owner. Administratively, the manager was the gatekeeper, controlling access to the interior living space of the hacienda owner and his family, and the architectural placement of the manager’s office reflects this role. The living space of the hacienda owner, the Patio del Limon, is the most restricted space in the hacienda and simultaneously the most self-sufficient. Once they had passed through the working areas of the hacienda upon arrival, the hacienda owner and his family could lock themselves in the Patio and live in uninterrupted luxury if they so chose.

Domestic spaces in Fig. 5 are shown in green, workspaces are highlighted in red. Domestic spaces of the hacienda’s inhabitants were separated, with the workers occupying homes at the first level of access, and the hacienda owner occupying a domestic space at the sixth and seventh level of access (Figs. 5 and 6; bottom). The working areas of the hacienda created a barrier, both conceptual and physical, between the workers and the owners. This design facilitated control and supervision of the workforce with the hacienda owners needing to pass through the working areas to enter and leave their home.

Oral historical descriptions of the Patio del Limon were hard to come by, which supports the idea that this space was highly restricted. The few workers allowed into the Patio del Limon would have found themselves in a world wholly different from that occupied by the rest of the inhabitants of the Hacienda Acocotla. The handful of informants who were able to describe the Patio before its ruin did so with emotion approaching reverence. They described a quiet space filled with lime trees and flowering plants, dominated by an elaborate fountain in the center. The walls surrounding this patio today show the remnants of what must have once been impressive decoration, adding to the experience of those allowed into the space. While we were able to collect only two recollections of the patio space, not a single former worker was found who could describe the interiors of the rooms surrounding the Patio, supporting the suggestion that these spaces were even more restricted. In creating an area so sumptuously distinct and inaccessible to the majority of the hacienda’s inhabitants, Acocotla’s owners confirmed their right to the position of power they held over the lives of their workers.

But what of the calpanería where the hacienda’s workers spent the majority of their time? It too seems to be part of the program of modernization and control seen in the reorganization of the hacienda’s architecture. The calpanaría is a distinctly nineteenth century and central Mexican architectural form (Charlton 1986; Jones 1978; Konrad 1980; Terán Bonilla 1996; Trautmann 1981). Prior to independence, resident workers were housed on hacienda land, but separate from the hacienda’s administrative and residential buildings (Newman 2014a). Though these residences would have been under the control of the hacienda owner, workers inhabiting these spaces would have had a reasonable measure of autonomy in arranging their family lives and community organization. This pattern of residence changed throughout central Mexico as the calpanería as it is recognized today was introduced during the nineteenth century.

The Phenomenological Experience of the Hacienda

An analysis of Acocotla’s architecture based on space syntax emphasizes the ways both space and the hacienda’s population were segmented to facilitate elite control, but what of transforming identity? The varied access and points of control would have impacted how people perceived the space they were moving through, and by extension their place in it. This understanding of the place in which they “belonged” would have been a foundational component of their understanding of their individual and community identity in relation to their mode of production.

Though these aspects of identity generation are difficult to access archaeologically, a phenomenological exploration of the Hacienda Acocotla allows us to understand the emotional impact of spaces that were either accessible or not as we follow the same paths that Acocotla’s workers, managers, and owners once walked. Phenomenology argues that the human experience can’t be understood in purely analytic terms, and that the visceral experience of moving through a space is fundamental to understanding both it and the people who inhabited it (Johnson 2012: 273). By walking through the Hacienda Acocotla’s casco, we can explore the ways in which the points of access and restriction illuminated by the J-diagram impacted the human experience.

Today, we approach the Hacienda Acocotla from the east, as visitors approached during most of its history. Our first glimpse of Acocotla’s casco is a lookout tower looming above the treetops. Small slits in the face of the tower allowed Acocotla’s residents to observe not only the road but all of the surrounding fields and the approach to the casco without being seen. This tower, the most difficult area of the casco to access, intimidates the viewer. As we near the building, we cannot know if our approach is monitored. Workers in the nearby fields would have had the same experience when the hacienda was in operation.

As we get closer, the two-story rear walls of the casco come into view. They face, across the road, the small chapel that served the entire hacienda community throughout its history. Following the road as it curves past what was probably once the hacienda’s façade (but is now the remains of a series of wheat storage sheds), we encounter the plain, imposing entrance flanked by thirty-seven small rooms (Fig. 7).

These rooms are the hacienda’s calpanería. Designed and built by the hacienda owner or manager during the larger program of modernization, the space housed Acocotla’s resident worker population during the second half of the nineteenth century. The calpanería, and the entire façade of the casco, would have been finished in white plaster, and the rooms of the calpanería would have been roofed in red pan tile (Newman 2014a). As many as 121 men, women, and children lived in these 3.5 m by 3.5 m rooms—one room to each family—though the population fluctuated, dropping as low as 34 in 1857. The tiny rooms would have been used for little more than sleeping and shelter from the rain, and the field fronting the calpanería would have been the site of most daily household activities (Newman 2013, 2014a, b). The entire area, open to the fields and the road, would have left Acocotla’s workers exposed to the prying eyes of passersby and the dangers of the Mexican countryside.

Today, when we return to the main entrance, we can easily pass through the arched entryway, but during its occupation, this doorway would have been barred by a heavy wooden door. The door would have kept visitors, bandits, and the hacienda’s lowest status workers from entering the casco without permission of the hacienda’s guards. As we pass through this arch, we are greeted by the remains of a two-room guardhouse on the left-hand side of the passageway before access paths branch in three directions.

Walking past the guardhouse and glancing to the left, we see a large patio area. During the nineteenth century, rooms bounding the edges of this patio stored farm implements and other tools necessary to hacienda life and work. The north side of the patio is dominated by an ornate arch that leads to the animal patio, an area that would have housed both cows and horses, as well as provided storage for animal fodder. On the west side of the patio, a small doorway offers the only access to the walled kitchen garden. Some of the hacienda’s workers would have been allowed into this space during the day to tend the herds and gather tools. Likely they noticed that while their living area was exposed and unprotected, the livestock were accorded safer quarters, had free and easy access to water (something which the inhabitants of the calpanería lacked), and even enjoyed homes with significantly greater architectural elaboration.

Continuing our exploration, we return to the central corridor and guardhouse and then follow the right-hand access path into the Patio de Los Chivos (Patio of the Goats). At the end of the nineteenth century, this area housed the caporales, mid-level and more trusted workers, in four rooms on the northern side of the patio. The caporales were responsible for the hacienda’s animals and seem to have had special control over the goat herds, with whom they shared this living space (Newman 2014a). A trough on the south side of the patio provided water for the herds and the caporales both, and it is to this trough that the workers living in the calpanería would have had to come when they needed water. Here, the difference in status between lower and upper classes of worker would have been impossible to ignore. Though still monitored by the guards across the hallway, the caporales had larger, safer homes, a greater degree of privacy, and possibly a certain amount of personal wealth represented by management or ownership of the goats.

Back again at the central access path, the main corridor leads north through another arched entryway to the Patio Abierto (the Open Patio). This patio provided storage for tools, especially those associated with the animals, as well as more stable space for both horses and cows. This area was normally accessible only to the manager, the caporales in their business with the herds, and the workers who were employed to cook and clean in the hacienda owner’s living quarters; however, on Saturdays everybody entered this area to collect their week’s wages. This space also housed the manager’s office and the hacienda owner’s kitchen. Both of these last were located in the Southeast corner of the patio adjacent to the arch leading to the final area of the hacienda.

The hacienda manager’s office provided the final barrier between workers and hacienda owner. Just past this administrative space, a set of double arches leads us into the Patio del Limon, named for the lime trees that once filled it. This highly restricted patio would have been the hacienda owner’s living quarters when he and his family were in residence. Other than the hacienda owner, his family, and guests, the only people allowed into this space would have been the manager and the few workers paid to cook and clean for the family.

Though it now stands in ruins, numerous decorative elements are still visible in the Patio del Limon including ornamental and functional arches and pillars, designs painted in red on white plaster, the remains of an ornate fountain, and a mosaic of glass around a window (Fig. 8). These remnants hint at the grandeur of a bygone era. The few workers allowed into the space might have taken pride at their access to such a beautiful and restricted space, or perhaps they resented the material differences between their homes and the rarely-occupied owner’s quarters.

For most of the workers, though, the Patio del Limon would have been understood only through imaginings built on whispered rumors, something that would have increased the space’s power to intimidate and reaffirm the established social order. The three-story tower located at the northeast corner of the Patio was one of the few architectural spaces to prompt evocative memories, remnants of those whispers.

The first of two commonly circulated stories was that the purpose of the tower was for surveillance of the workers—we were told, “Someone stood up there to make sure the peones never sat down in the fields.” The second, more ominous, was that an evil spirit called the “tlilgual” (literally a “black soul” in Nahuatl) inhabited the tower. The tlilgual was a giant, two-headed, black serpent with a red chest sent by the hacienda owner to interfere with the lives of his peones. No matter which story you prefer, the tower was a source of malevolent and anonymous surveillance.

Discussion

The Mexican hacienda provides an ideal case study for exploring the uses of architecture in not just controlling but creating a proletariat. Established during the early years of Spanish conquest, haciendas were a home and a business, a working farm, but they were also an institution that structured the relationship between the European conqueror (the hacienda owners) and the indigenous conquered (the hacienda workers) (Charlton 1986; Knight 2002; Israel 1975; Van Young 2006; Wolf and Mintz 1957). Because architecture shapes and is shaped by behavior, the physical organization of the hacienda reflected the priorities of the owners and the ruling class to which they belonged. As priorities shifted over time, the architecture of the hacienda also shifted—most significantly during the Porfiriato when haciendas throughout Mexico became the elaborate, stately homes we recognize today (Charlton 1986; Jones 1978). Late nineteenth century, upper-class Mexican concerns about transforming rural indigenous populations into modern, Western capitalist workers and consumers may be read in the now-ruined remains of rural haciendas.

Architectural compartmentalization and specialization like that seen at Acocotla has been shown time and again to be part of processes of modernization and embedded in the development of capitalism (Deetz 1977; Giddens 1984; Glassie 1987; Jamieson 2000; Johnson 1996). Acocotla’s mid-nineteenth century remodeling created a complex architectural structure with separate, controlled, and defined spaces dedicated to particular tasks—something that would have increased control over the hacienda’s workers and reinforced their understand of their place in society. By creating spaces with highly specific and clearly defined uses, Acocotla’s owner created an environment in which the ways individuals moved through the space, used time, and completed tasks were carefully controlled.

Further, the connection between status and architecture is clear. Individuals with the lowest status, namely the workers, were largely restricted to level one access points, though they may have occasionally been allowed into levels two and three to assist with animal care. Mid-level workers, the caporales, occupied rooms at the third level of access and, thanks to their duties with the animals, would have had access to areas in levels 1–4. These were people who were described in oral histories as being both “higher status” and “more trusted” by our informants (Newman 2014a). All the workers were allowed into the Patio, at the fourth level, on the very edge of the hacienda owner’s living quarters just once a week in order to accept their payment for the week’s work, an event that would have seemed ceremonious as they were handed their weekly salary and maize rations while the manager made notes of the exchange in his account books.

Control was based on more than just exclusion. Archaeological evidence indicates that Acocotla’s calpanería was constructed during the 1860s and then expanded again later in the century (Newman 2014b). During the initial construction period, the hacienda’s workers would have been taken out of semi-independent villages and moved into what we might call “company housing.” The calpanería was designed by and for the hacienda owner, not by or for the individuals who would be housed in the space. The new worker housing would have facilitated control, naturalized the social structure, and allowed the hacienda owner to commodify labor across gender lines in ways it never before had been (Newman 2013). First, by designing a structure that was open, linear, fronting the road, and flanking to entrance to the hacienda, the hacienda owner created a space that would encourage the workers to engage in a self-reflexive monitoring of their actions (Giddens 1984). Because anybody could pass by the calpanería at any time and because the hacienda owner or his manager could approach or emerge from the hacienda at any moment, the workers would have been required to behave always as if they were being watched.

Further, by creating multiple “levels” of housing for different “classes” of worker, the hacienda owner was reinforcing and naturalizing the social order (Foucault 1979; Giddens 1984). The “higher status” and “more trusted” caporales occupied a space that was private and enclosed. Though the area was adjacent to the guardhouse, the caporales would have enjoyed much more privacy and a greater level of security. While the workers living in the calpanería had to ask permission to enter the hacienda to collect water from the animal troughs for cooking and other household needs, the caporales had free and easy access to such necessities. The casco’s complexity allowed the hacienda owner to determine the movement of people through the space to control how workspace and home are defined and used—because, above all else, the casco was not a home but a business.

Conclusion

But was the nineteenth century program of modernization a success? Did the upper classes transform the identities of Mexico’s rural indigenous workers and increase their productivity? In the short term, perhaps. By 1896, the purchase price of the Hacienda Acocotla had risen to 80,000 pesos, an increase in value of more than two hundred and fifty percent since Ana Cristina Treviño de Ruelas’ 1860 purchase (Romano Soriano 2005, 43–44). This may have been due to the elaboration of the casco’s architecture, an increase in productivity of the property as a farm, or a combination of the two. Regardless, the redesign of Acocotla’s casco acted to increase the property value and stabilize the business.

As the nineteenth century progressed, changes at Acocotla impacted more than just the lives of the owners. The lives of the workers, too, were transformed. By 1910 on the eve of the Mexican Revolution, the Hacienda Acocotla’s workers were on the path to becoming “good consumers.” Ninety percent of Acocotla’s employees were in debt to the hacienda owner, some for more money than an adult male worker could earn in a year (Newman 2013, 678). They had borrowed this money to make purchases, for either luxury goods or daily necessities, from the hacienda’s store. From common cooking pots to costume jewelry to perfume bottles, the more than eighty-seven thousand artifacts recovered from excavations in the calpanería speak to both of these sorts of purchases.

The program of modernization we read in Acocotla’s architecture was, however, ultimately a failure. Acocotla’s owners won a measure of short-term success, but it seems that their program of modernization, and the attacks on individual and family identity that came with it, pushed hacienda workers to rebellion during the Mexican Revolution (Newman 2013, 2014a). Though many in the descendant community today believe that life had been materially better under the hacienda regime, none would choose to return to it.

Today, the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla is a patchwork of fields farmed by the descendants of Acocotla’s workers. Acocotla’s casco stands in ruins, but the impact of its architecture on the identity of the surrounding communities and their relationship to Mexico’s power structure is no less than it was a century ago. Following the early twentieth century Mexican Revolution, the new Mexican government expropriated Acocotla’s lands and buildings. Acocotla’s workers returned to the community-based, subsistence-level mode of production that had been the foundation of their individual, family, and community identity for hundreds of years.

In 1935, the Mexican government concluded the slow process of dismantling the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla. While parcels of land were sold off or given to Acocotla’s former workers, Acocotla’s casco was given to two communities to be held in common. In so doing, the government ensured that the casco would remain untouched. Now, those who pass by its crumbling walls often acknowledge a debt owed to the Mexican government. The ruins are a reminder of their history, of their oppression by hacienda owners and their “liberation” at the hands of Mexico’s post-Revolutionary government. Just as it has for centuries, Acocotla’s casco continues to mold social identity and reinforce the existing power structure.

Notes

At Acocotla, we chose to use the label “indigenous” for the hacienda’s workers and the neighboring villagers because numerous government documents, ranging from censuses to police reports, label the people of the calpanería and the nearby villages as, without exception indigenous speakers of Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs). Though it may not have been how people labeled themselves in the past, and assuming ethnic labels based on language can be dangerous, it seems the most reasonable and accurate term to use based on the available information.

ACEHM-CARSO 1686, Mercedes, fondo DCCLXV, f. 623 “las casas de vivienda que se componen de una sala y un aposento techado de vigas con tres puertas con sus llaves y encima una troxe de sacate otra troxe baja de adobe cubierta de zacate con su puerta y llave de iova. Una cocina de adobes cubierta de zacate. Otro aposento grande pegado a la dicha cocina a la parte norte de adobes con su puerta sin llave. Mas otro aposento nuevo de adobes cubierto de zacate con puerta. Un gallinero de tapias pequeño cubierto de zacate, con su puerta. Mas un aposento de terrado y enladrillado arriba con su puerta y llave que cole dentro del patio al pie de la escalera de la troxe de arriba. Un horno de ladrillo enladrillado y revocado de cal. Una capilla del Señor San Miguel cubierta de vigas nuevas y arriba en ladrillada con sus rafos de cal y canto y las paredes de adobes con los hornamentos siguientes: un frontal de razo encarnado y blanco con sus cardas de lama y cazulla de razo blanco, un alua de Juan, un amito de lo mismo, estola manipulo y singulo, manteles de altar de Juan, un calix de plata y patena sobre dorado, un misal con su atril, dos candeleros de madera dorados, un hostirario de oja de lata, una campanilla pequeña, un cajón en que se guarda todo lo referido, una ara y una bolsa con sus corporales, una palia con sus puntas blancas, una cruz de madera dorada y sus vinagreras, una hechura del Señor San Miguel de talla, una mesa de madera, dos sillas de espaldar de baqueta negra, una blanca, la llave de las puertas de dicha capilla, cincuenta y cinco bueyes mansos de arada, los trece viejos, dos vacas de vientre nuevas con siete becerros y becerras de año, doce yugos con doce pares de coyundas crudias, dos yugos de oreja, una carreta vieja con tres cuartas, doce cinchos de hierro de carretas, una arroba y dieciseis libras de hierro en dieciocho marquetas, ocho azadones viejos, dos docenas de hoces viejas, dos hachas la una viscaína y la otra de ojo redondo, un escoplo grande una azuela de martillo y una barrena para cabezar, doce timones nuevos y siete viejos, doce cabezas nuevas, una media fanega herrada y otra sin herrar, seis palas, dieciseis abujas de madera para corral todas con sus latas, tres cobras de mecate, un xaguei con su chilton de cal y canto.”

ANP 1860, Atlixco, f. 218v-220v.)“Su casa es de edificio alto y bajo, tiene su frente mirando al oriente, y se le miden cincuenta y seis varas de latitud, con cincuenta dichas de longitud, en cuyas mesuras se halla fabricado lo siguiente: zahuan techado sobre un arco en él, puertas a dos piezas con ventanas bobas; patio en él una pesebrera al descubierto; sigue un machero techado sobre dos arcos, en el otro lateral una escalera a las azoteas y puertas a una atrox de mucha amplitud solada de ladrillos: sigue un portal con cinco arcos, sobre pilares de ladrillo padeciendo deterioro, en dichas dos piezas, la escalera bajo de cubierta, de dos tramos, en el primero puerta a una pieza entre suelo, el segundo desembarca al corredor, con antepecho de ladrillo, techado con cinco arcos en dicho, puerta a una sala, por una de sus cabeceras puerta y mampara a otra con ventana y puerta a otra pieza con puerta a las azoteas; volviendo a la sala puerta a un miradorcillo y puerta al comedor; con dos alacenas y dos puertas, una al corredor, y otra a la cocina con bracero alto, carbonera, ventana y alacena, puerta a los lugares, una escalera que desciende al corral de gallinas, con su gallinero; volviendo al corredor, puerta a otra pieza y puerta a una atrox que abraza el lateral del patio; bajando al patio se encuentra un cuarto pequeño que sirve de carpintería: saliendo al campo en el mismo frente la puerta del gallinero, un techo nuevo de terrado; la era solada de ladrillo maltratado: en un costado de la casa dos puertas bobas, una al pajar, y la otra a la tlapixquera: siguen unas cercas de tapia en estado de ruina y cinco cuartos también en ruina; la capilla, su cementerio cercado a buen alto, su campanil con campana de dos arrobas de peso. En donde terminan todas las piezas viviendas y oficinas de que se compone esta casa, su fábrica es toda de tierra con poco calicanto, toda la fábrica padeciendo deterioro, en razón de que varias paredes las han trasminado las ratas, las maderas de los techos puertas y ventanas en el mismo estado la mayor parte y haciéndome cargo de lo relacionado, costos de materiales y jornales de operarios, la aprecio en cinco mil trescientos, veintinueve pesos.”

During our research period, Atlixco’s municipal archives were re-catalogued and documents were re-numbered. Except where noted, the records here follow the older system and, for the sake of future research, correspond with the published index (Guadalupe Curi et al. 1984). Bibliographic records followed by an asterisk [*] were not catalogued in the original index and so follow the new system. Interested researchers will find that the two systems of notation are cross-indexed in the archives.

References

Alexander, R. T. (2003). Architecture, haciendas, and economic change in Yaxcabá, Yucatán, Mexico. Ethnohistory 50(1): 191–220.

Alexander, R. T. (2004). Yaxcabá and the Caste War of Yucatán: an Archaeological Perspective, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Alexander, R. T. (2012). Prohibido Tocar Este Cenote: the archaeological basis for the Titles of Ebtun. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 16(1): 1–24.

Archivo Histórico Municipal de Atlixco [AHMA] (1841). Petition from the workers in the Valley of Atlixco to be freed from paying the Chicontepec because they cannot send their children to school because they need them to work and because the roads are unsafe. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 34, Exp. 5 (1714).

AHMA (1842a). Register Showing the Number of Inhabitants at Acocotla, Including Their Ages, Marriage Status, and Positions. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 42, Exp. 4 (1924).

AHMA (1842b). An invitation to the owners of the haciendas in the Valley of Atlixco to discuss public security and the safety of the roads prompted by recent problems. Cristobal Pedraza. Gobierno, Caja 43, Exp. 4 (1926).

AHMA (1842c). Hacienda owners establish a rural security force of 43 men to hunt down the highwaymen giving the inhabitants of the Valley trouble. Cristobal Pedraza. Gobierno, Caja 43, Exp. 4 (1940).

AHMA (1844). Men between the ages of 16 and 60 living at the Hacienda Acocotla including names, ages, and occupations. Mariano Ramírez. Gobierno, Caja 56, Exp. 5 (2245).

AHMA (1853). Census of the people at the Hacienda Acocotla who are categorized as “gente de rázon.” Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 74, Exp. 1 (3068).

AHMA (1854). Register of Individuals at the Hacienda Acocotla. Antonio Ranjel. Presidencia, Caja 76, Exp. 1 (3121).

AHMA (1855). Notice regarding an attack on a hacienda in the Valley of Atlixco and expressions of concern about the lack of security because of others. José M. Rofríguez. Gobernación, Caja 98, Exp. 1, f.1-2.*

AHMA (1857a). Register of the Inhabitants of the Hacienda Acocotla in 1857. Antonio Rangel. Gobierno, Caja 82, Exp. 2 (3540).

AHMA (1857b). Allocation of horses from the haciendas and ranchos in the Valley of Atlixco. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 85, Exp. 1 (3754).

AHMA (1857c). Flier calling workers in the Valley of Atlixco to present themselves in the city to request the government secure the safety of the roads and end problems with the bandits. Mariano G. Castaño. Gobierno, Caja 85, Exp. 2 (3799).

AHMA (1860). Organization of a local, private system to guard the roads and increase safety because of the continuing problem with robberies. Francisco Enciso. Gobierno, Caja 87, Exp. 4 (3916).

AHMA (1863). Order from the prefect to the haciendas in the Valley of Atlixco to enroll their workers, servants and dependents over the age of eighteen in the militia to be under the command of the Civil Guard. Manuel Amador. Gobierno, Caja 94, Exp. 3 (4234).

AHMA (1867). List of the haciendas and ranchos in the Valley of Atlixco and the contribution each must make towards the purchase of fifty horses and weapons for the militia. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 106, Exp. 2 (4644).

AHMA (1868a). A report regarding the project to establish a public security force to do away with the bandits that are troubling the haciendas and ranchos in the Valley of Atlixco. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 110, Exp. 1 (4809).

AHMA (1868b). Census of workers at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla including ages, marriage status, occupations, family organization, and literacy levels. José María Motolinía. Gobierno, Caja 110, Exp. 3 (4857).

AHMA (1869). A security report from the haciendas in the Valley of Atlixco regarding robberies. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 113, Exp. 1 (4927).

AHMA (1870). Census of workers at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla including family information, ages, occupations, and whether or not the children are schooled. José María Motolinía. Gobierno, Caja 115, Exp. 2 (4971).

AHMA (1871a). Census of workers at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla including ages, marriage status, occupations, and literacy levels. José María Motolinía. Gobierno, Caja 118, Exp. 2 (5001).

AHMA (1871b). A report regarding the establishment of a rural force by the haciendas and ranchos of the Valley of Atlixco. L. Flores. Gobierno, Caja 119, Exp. 1 (5034).

AHMA (1872a). Register of Men Housed at the Hacienda Acocotla. José María Motolinía. Gobierno, Caja 123, Exp. 3 (5174).

AHMA (1872b). List of workers at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla and payments for their reduced service with the National Guard, as well as occupations, ages, marriage status, and wages. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 123, Exp. 4 (5206).

AHMA (1876a). Abduction and ransom of a Hacienda Owner in the area of Huaquechula. F. Cerezo. Gobierno, Caja 152, Exp. 1 (5874).

AHMA (1876b). An announcement from Acocotla regarding the presence of a force of rebels. Miguel Rangel. Gobierno, Caja 152, Exp. 2 (5896).

AHMA (1876c). An order establishing the rural forces in the state of Puebla with a list of haciendas and ranchos in the Valley of Atlixco and the number of horses they would provide. Lic. Antonio C. de Hayes. Gobierno, Caja 152, Exp. 3 (5912).

AHMA (1876d). An announcement regarding the formation of a second public security force. Unsigned. Gobierno, Caja 153, Exp. 3 (5941).

AHMA (1876e). A collection of reports of robberies made in the Valley of Atlixco at the hacienda Acocotla and La Mojonera between April 30th and June 16th. Miguel Rangel and Manuel Cruz Domínguez. Gobierno, Caja 155, Exp. 1 (5975).

AHMA (1876f). A letter from La Mojonera announcing the presence of a group of thieves robbing people on the road to Atlixco. Manuel Cruz Domínguez. Gobierno, Caja 155, Exp. 1 (5978).

AHMA (1884). List of Individuals at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla who are paying the Chicontepec. Unsigned. Hacienda, Caja 221, Exp. 5 (15318).

AHMA (1889). Census of workers at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla including ages, marriage status, occupations, family organization, and literacy levels. Nazario Molina. Gobierno, Caja 263, Exp. 2 (11532).

AHMA (1893). Register of Residents at the Hacienda Acocotla. Nazario Motolinía. Gobierno, Caja 309, Exp. 5 (12890).

Baxter, J. E. (2012). The paradox of a Capitalist Utopia: visionary ideals and lived experience in the Pullman community 1880–1900. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 16(4): 651–665.

Beaudry, M. C. (1989). The Lowell Boott Mills complex and its housing: material expressions of corporate ideology. Historical Archaeology 23(1): 19–32.

Benavides Castillo, A. (1985). Notas Sobre la Arquelología Histórica de la Hacienda Tabi, Yucatán. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Antropológicos 31: 45–58.

Blanton, R. E. (1994). Houses and Households: a Comparative Study, Plenum Press, New York.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). The Berber house. In Douglas, M. (ed.), Rules and Meanings; the Anthropology of Everyday Knowledge, Penguin Education, Harmondsworth, pp. 98–110.

Casella, E. C. (2001). To watch or restrain: female convict prisons in nineteenth-century Tasmania. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 5(1): 45–72.

Chapman, W. (1991). Slave villages in the Danish West Indies: changes of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 4: 108–120.

Charlton, T. H. (1986). Socioeconomic dimensions of urban–rural relations in the colonial period basin of Mexico. In Spores, R. (ed.), Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 4, Ethnohistory, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 122–133.

Chevalier, F. (1963). Land and Society in Colonial Mexico: the Great Hacienda, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Cutting, M. (2003). The Use of spatial analysis to study prehistoric settlement architecture. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22(1): 1–21.

Dawson, P. C. (2002). Space syntax analysis of central Inuit snow houses. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 21(4): 464–480.

Deetz, J. (1977). In Small Things Forgotten: the Archaeology of Early American Life, Doubleday, Garden City.

Delle, J. A. (1999). Landscapes of class negotiation on coffee plantations in the blue mountains of Jamaica: 1790–1850. Historical Archaeology 33(1): 135–158.

Delle, J. A. (2009). The governor and the enslaved: an archaeology of colonial modernity at Marshall’s Pen, Jamaica. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13(4): 488–512.

Delle, J. A. (2014). The Colonial Caribbean: Landscapes of Power in Jamaica’s Plantation System, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Dyckerhoff, U. (1988). La Región del Alto Atoyac en la Historia: La Época Prehispánica. In Prem, H. J. (ed.), Milpa y Hacienda: Tenencia de la Tierra Indígena y Española en la Cuenca del Alto Atoyac, Puebla, México (1520–1650), Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Puebla, pp. 18–34.

Edwards, M. J. (2013). The configuration of built space at Pataraya and Wari provincial administration in Nasca. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32(4): 565–576.

Epperson, T. (1990). Race and the disciplines of the plantation. Historical Archaeology 24(4): 29–36.

Fellows KR and Delle JA. (2015) Marronage and the dialectics of spatial sovereignty in colonial Jamaica. In Current Perspectives on the Archaeology of African Slavery in Latin America, Springer, New York, pp. 117–132.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York.

Fournier-Garcia, P., and Mondragon, L. (2003). Haciendas, Ranchos, and the Otomi Way of Life in the Mezquital Valley, Hidalgo, Mexico. Ethnohistory 50(1): 47–68.

Funari, P. P. A., and Zarankin, A. (2003). Social archaeology of housing from a Latin American perspective. Journal of Social Archaeology 3(1): 23–45.

Gerhard, P. (1993). A Guide to the Historical Geography of New Spain, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Gibson, C. (1964). The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: a History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico 1519–1810, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Glassie, H. H. (1975). Folk Housing in Middle Virginia: a Structural Analysis of Historic Artifacts, University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Glassie, H. H. (1987). Vernacular architecture and society. In Ingersoll, D. W., and Bronitsky, G. (eds.), Mirror and Metaphor: Material and Social Constructions of Reality, University Press of America, Lanham, pp. 229–245.

Guadalupe Curi, S, P Paleta, C Delgado, J de Gante, E Maceda, R Cruz Valdes, CE Benitez, and F Tellez Guerrero. (1984) Catálogo del Archivo Histórico Municipal de Atlixco. Vols. 1–3. Puebla, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Instituto de Ciencias, Centro de Investigaciones Históricas y Sociales.

Hanks, W. F. (2010). Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hernández Álvarez, Á. H. (2014). Corrales, chozas y solares: estructura de sitio residencial. Temas antropológicos: Revista científica de investigaciones regionales 36(2): 129–152.

Hillier, B., and Hanson, J. (1984). The Social Logic of Space, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Israel, J. I. (1975). Race, Class, and Politics in Colonial Mexico, 1610–1670, Oxford University Press, London.

Jamieson, R. W. (2000). Domestic Architecture and Power: the Historical Archaeology of Colonial Ecuador, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York.

Johnson, M. (1996). An Archaeology of Capitalism, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Johnson, M. H. (2012). Phenomenological approaches in landscape archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 269–284.

Jones D. (1978). Nineteenth Century Haciendas and Ranchos of Otumba and Apan. Institute of Archaeology. University of London, London.

Jones, D. (1981). The importance of the hacienda in nineteenth century Otumba and Apan, basin of Mexico. Historical Archaeology 15(2): 87–116.

Joseph, J. W. (1993). White columns and black hands: class and classification in the plantation ideology of the Georgia and South Carolina low country. Historical Archaeology 27(3): 57–73.

Juli, H. (2003). Perspectives on Mexican hacienda archaeology. The SAA Archaeological Record 3(4): 23–24.

Juli, H., Newman, E. T., and Sáenz Serdio, M. A. (2006). Arqueología Histórica en la Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla, Atlixco Puebla: Informe de la Primera Temporada de Excavaciones, 2005 y Propuesta para la Segunda Temporada, 2006. Mexico City: Unpublished Report to the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Kanter, D. E. (2008). Hijos Del Pueblo: Gender, Family, and Community in Rural Mexico, 1730–1850, University of Texas Press, Austin.

Knight, A. (2002). Mexico: the Colonial Era, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Konrad, H. W. (1980). A Jesuit Hacienda in Colonial Mexico: Santa Lucía, 1576–1767, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Leone, M. P. (1984). Interpreting ideology in historical archaeology: using the rules of perspective in the William Paca garden in Annapolis, Maryland. In Miller, D., and Tilley, C. (eds.), Ideology, Power, and Prehistory, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 25–35.

Leone, M. P. (1995). A historical archaeology of capitalism. American Anthropologist 97(2): 251–268.

Meyer, J. A. (1973). Problemas Campesinos y Revueltas Agrarias (1821–1910), Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City.

Meyers, A. D. (2005). Material expressions of social inequality on a Porfirian Sugar Hacienda in Yucatán, Mexico. Historical Archaeology 39(4): 112–137.

Meyers, A. D. (2012). Outside the Hacienda Walls: the Archaeology of Plantation Peonage in Nineteenth-Century Yucatán, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Meyers, A. D., and Carlson, D. L. (2002). Peonage, power relations and the built environment at Hacienda Tabi, Yucatán, Mexico. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6(4): 225–252.

Meyers, A. D., Harvey, A. S., and Levithol, S. A. (2008). Houselot refuse disposal and geochemistry at a late nineteenth century hacienda village in Yucatán, Mexico. Journal of Field Archaeology 33(4): 371–388.

Miller, H. (1988). Baroque cities in the wilderness: archaeology and urban development in the colonial Cheasapeake. Historical Archaeology 22(2): 57–73.

Morales, L. M. (2006). Trigo, trojes, molinos y pan, el dorado de la oligarquía poblana. Theomai: estudios sobre sociedad, naturaleza y desarrollo (13): 3.

Morton, S. G., Peuramaki-Brown, M. M., Dawson, P. C., et al. (2012). Civic and household community relationships at Teotihuacan, Mexico: a space syntax approach. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 22(03): 387–400.

Mrozowski, S. A. (1991). Landscapes of inequality. In McGuire, R. H., and Paynter, R. (eds.), The Archaeology of Inequality, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 79–101.

Mrozowski, S. A., Ziesing, G. H., and Beaudry, M. C. (1996). Living on the Boott: Historical Archaeology at the Boott Mills Boardinghouses, University of Massachusetts Press, Lowell, Massachusetts, Amherst.

Nashli, H. F., and Young, R. (2013). Landlord villages of Iran as landscapes of hierarchy and control. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17(1): 143–158.

Newman, E. T. (2010). Butchers and Shamans: zooarchaeology at a central Mexican hacienda. Historical Archaeology 44(2): 35–50.

Newman, E. T. (2013). From prison to home: coercion and cooption in nineteenth century Mexico. Ethnohistory 60(4): 663–692.

Newman, E. T. (2014a). Biography of a Hacienda: Work and Revolution in Rural Mexico, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Newman, E. T. (2014b). Historical archaeology at the Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla. Latin American Antiquity 25(1): 27–45.

Newman, E. T., and Castillo Cardenas, C. K. (2013). San Miguel Acocotla: arqueologia de una hacienda del siglo XIX, Segundo Coloquio de Argueologia Historica, Mexico City.

Newman, E. T., and Juli, H. D. (2008). Historical Archaeology and Indigenous Identity at the Ex-Hacienda San Miguel Acocotla, Atlixco, Puebla, Mexico. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc (FAMSI).

Paredes Martínez, C. S. (1991). La Región de Atlixco, Huaquechula y Tochimilco. La Sociedad y la Agricultura en el siglo XVI, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Gobierno del Estado de Puebla, Mexico City.

Patch, R. W. (1985). Agrarian change in eighteenth-century Yucatán. Hispanic American Historical Review 65(1): 21–49.

Plunket, P. (1990). Arqueología y Etnohistoria en el Valle de Atlixco. Notas Mesoamericanas 12: 3–18.

Pogue, D. J. (2002). The domestic architecture of slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Winterthur Portfolio 37(1): 3–22.

Potter, P. B. (1994). Public Archaeology in Annapolis: a Critical Approach to History in Maryland’s Ancient City, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Potter, P. B., and Leone, M. P. (1992). Establishing the roots of historical consciousness in modern Annapolis, Maryland. In Karp, I., Mullen Kreamer, C., and Lavine, S. D. (eds.), Museums and Communities: the Politics of Public Culture, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp. 476–505.

Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Reina, L. (1980). Las Rebeliones Campesinas en México, 1819–1906, Siglo Veintiuno, Mexico City.

Robb, M. H. (2007). The construction of civic identity at Teotihuacan, Mexico. History of Art. Yale University, New Haven, 425.

Romano Soriano, M.del C. (2005). San Miguel Acocotla, Atlixco: Las Voces y la Historia de una Hacienda Triguera. Departamento de Antropología. Universidad de las Américas, Puebla, Cholula.

Ruiz, J. (2014). Americans in the Treasure House: Travel to Porfirian Mexico and the Cultural Politics of Empire, University of Texas Press, Austin.

Shackel, P. A., and Palus, M. M. (2006). The gilded age and working‐class industrial communities. American Anthropologist 108(4): 828–841.

Singleton, T. A. (2001). Slavery and spatial dialectics on Cuban coffee plantations. World Archaeology 33(1): 98–114.

Smith, M. E. (2007). Form and meaning in the earliest cities: a new approach to ancient urban planning. Journal of Planning History 6(1): 3–47.

Steadman, S. R. (1996). Recent research in the archaeology of architecture: beyond the foundations. Journal of Archaeological Research 4(1): 51–93.

Sweitz, S. R. (2012). On the Periphery of the Periphery, Springer.

Terán Bonilla, J. A. (1996). La Construcción de las Haciendas de Tlaxcala, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México, D.F.

Trautmann, W. (1981). Las Transformaciones en el Paisaje Cultural de Tlaxcala Durante la Época Colonial: Una Contribución a la Historia de México Bajo Especial Consideración de Aspectos Geográfico-Económicos y Sociales, F. Steiner, Wiesbaden.

Tutino, J. (1986). From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750–1940, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Tutino, J. (2008). From Involution to revolution in Mexico: liberal development, patriarchy, and social violence in the Central Highlands, 1870–1915. History Compass 6(3): 796–842.

Upton, D. (1983). The power of things: recent studies in American vernacular architecture. American Quarterly 35(3): 262–279.

Van Young, E. (1983). Mexican rural history since chevalier: the historiography of the colonial hacienda. Latin American Research Review 18(3): 5–61.

Van Young, E. (1988). Islands in the storm: quiet cities and violent countrysides in the Mexican independence era. Past & Present 118: 130–155.

Van Young, E. (2006). Hacienda and Market in Eighteenth-Century Mexico: the Rural Economy of the Guadalajara Region, 1675–1820, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham.

Wernke, S. A. (2012). Spatial network analysis of a terminal prehispanic and early colonial settlement in Highland Peru. Journal of Archaeological Science 39(4): 1111–1122.

Whelan, D. A., and O’Keeffe, T. (2014). The House of Ussher: histories and heritages of improvement, conspicuous consumption, and eviction on an early nineteenth-century Irish Estate. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 18(4): 700–725.

Wolf, E. R. (1969). Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, New York.

Wolf, E. R., and Mintz, S. (1957). Haciendas and plantations in Middle America and the Antilles. Social and Economic Studies 6: 380–411.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the support and permission of the people of La Soledad Morelos and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), Mexico. In writing the preceding, I benefited greatly from the comments of Katheryn Twiss and Sharon Pochron at Stony Brook University, as well as two anonymous reviewers. Timothy Knab provided the etymology of “Tlilgual.” Archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnoarchaeological investigations were made possible through the financial support of The Reed Foundation, New York; the Fine Arts, Humanities, and lettered Social Sciences (FAHSS) Fund, Stony Brook University; the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI); the Agrarian Studies Program, Yale University; the John F. Enders Fund, Yale University; the Josef Albers Traveling Fellowship, Department of Anthropology, Yale University; and two anonymous donors. Research at Acocotla was originally begun by Dr. Harold Juli in 2001. Following his untimely death from cancer, I continued this project. Though some data discussed above were collected by Dr. Juli, the interpretations of the data are mine alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newman, E.T. Landscapes of Labor: Architecture and Identity at a Mexican Hacienda. Int J Histor Archaeol 21, 198–222 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0329-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0329-6