Abstract

The objective of this paper is to critically review the methods used to study service use by homeless persons with mental illness, and discuss gaps in the evidence base and research implications. Searches were conducted of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and PubMed to identify service use studies published between 2000 and 2014. Data were extracted on the types of services studied, quantification of service use, assessment tools, period of service use assessment, and analytic design. The review identified 27 studies described in 46 publications. The majority of the studies had observational designs that measured service use quantitatively as an outcome variable. Receipt or non-receipt and volume of use were the most common methods of quantifying service use. The types of services that have been examined primarily consist of formal mental health, primary health care, substance use, homelessness, and housing services. There is a considerable gap in the understanding of personal outcomes associated with use of services, as well as people’s experiences of using services. Specific to the homeless mentally ill population, there is an urgent need to better understand the role of service use in the attainment of stable housing and recovery from mental illness. In addition, less formal health and related services, such as peer support, have been largely excluded in service use research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Homelessness among persons with mental illness is a widespread problem that has considerable social and economic consequences. Despite tremendous variation in the prevalence rates of mental illness in this population, mental illness has consistently been found to be many times higher in homeless populations than in community samples (for a review, see Fazel et al. 2008). Further, high rates of psychiatric comorbidities, chronic medical conditions, and past abuse and victimization (Hwang et al. 2005, 2011) make for an extremely heterogeneous population with diverse needs. Yet, as service use by homeless persons with mental illness tends to be low, the unmet needs of this population remain high (Stergiopoulos et al. 2010).

Despite low use of services, some types of services are accessed more often than are others. These tend to be health and social services that offer short-term assistance or immediate help, rather than services that contribute to improvements in the material conditions of people’s lives. For example, homeless persons with mental illness use emergency departments as a source of mental health care more frequently than ambulatory care clinics and their rate of use is many times higher than among non-homeless persons (Folsom et al. 2005). The reliance on intensive crisis services has implications for the individuals using them, as well as mental health systems. Past research by McNiel and Binder (2005) found that many homeless people cycle through acute psychiatric care services, worsening the burden on hospital systems and not necessarily receiving services that meet their needs.

The overreliance on emergency services, as well as the overall low levels of use of other services, are the products of both individual level and systemic factors. At the individual level, past negative experiences, such as inadequacy of care, can be a critical barrier to seeking services (Bhui et al. 2006). Specific to health services, Gelberg et al. (2000) contended that the competing needs of homeless persons not only limit their ability to obtain services but also exacerbate their healthcare needs. For example, people who are homeless may frequently feel they have to choose between finding food or shelter for the night, and seeking care for a health problem. In a study of unmet needs among the homeless population, findings supported the hypothesis that competing priorities serve as a key barrier to care (Baggett et al. 2010). Further, when people lack insight into their mental illness, they are at greater risk of falling through the cracks and not receiving needed treatment until a crisis occurs or there is police intervention (Markowitz 2006).

As for systemic factors that affect service use, fragmentation and a lack of coordination between services is a critical impediment. Given that homeless mentally ill people represent an intersection between two serious problems (mental illness and homelessness), different service systems have traditionally been involved in the treatment and care of this population. Following the outset of deinstitutionalization, services were primarily situated within either the mental health or housing-homelessness sectors, which led to fragmentation problems in delivery (Lamb and Bachrach 2001). More recently, programs and interventions have been developed, such as Housing First and Assertive Community Treatment, which attempt to bridge the gap between the two sectors in order to provide more integrated services. However, difficulties accessing community services and navigating service systems are still frequently reported by this population (Rowe et al. 2016), suggesting there is still much work to be done.

Although problems with fragmentation in systems serving homeless people with mental illness are widespread (Geller 2015), it is necessary to recognize that systems, as well as the services within them, differ by location and approach. As Salize et al. (2013) found, a disproportionate amount of research on service use with this population has been conducted in the United States, with considerably less being carried out in the rest of the world. Because of this, researched services are more likely to reflect ones found in U.S. systems, though even those will differ between regions (e.g., urban and rural areas). Moreover, in places where similar services exist, there may be differences in how a given service is provided. For example, treatment services for substance use problems may utilize a harm reduction model or an abstinence-based approach, or models of care may be adapted within difference cultures, as has been done with Housing First in Canadian and European contexts (Goering et al. 2011; Greenwood et al. 2013). Given the differences between service systems and approaches, the array of services that exist for homeless people with mental illness may be considerably more diverse than it sometimes thought to be (Kerman et al. 2013; Rowe et al. 2016).

Beyond a consideration for how barriers and location may affect use of services, thought must also be given to how people use these services. Though the term “service use” is common, there has not been much attention placed on what it means to “use” services. In a most basic sense, service use implies some contact with a service or service provider. The notion of use, however, may also suggest a more complex set of interactions with a service or service provider, which may or may not lead to some gain or benefit for the service user. Whereas these interactions can be helpful or even empowering, they can also be inappropriate, irrelevant, disappointing, or dehumanizing. Thus, though on the face of it, “service use” may appear to be a simple notion, it quickly becomes a thorny and complex issue upon closer scrutiny. Yet, despite considerable research on service use by homeless persons with mental illness, no study has critically examined how service use has been studied.

Given the array of services that exist for this population, as well as the wide variety of potential meanings that “service use” can have, we contend that it is critically important to understand the definitions, methods, and assumptions that comprise research on this topic. Accordingly, the objectives of this review are to describe the recent research on service use among homeless persons with mental illness, identify methodological gaps in the evidence base, and discuss research implications. This review will address two questions: (1) How is service use being measured? and (2) What types of services are being studied? Additionally, this review will discuss some of the studies’ theories and assumptions, and how these inform the research. To our knowledge, this paper is the first review to examine how service use among homeless persons with mental illness has been studied as a means to comprehend this large body of work and identify future directions for research in this area.

2 Method

2.1 Search strategy

This review examines the methods that have been used to study service use among homeless adults with mental illness. Studies focusing on service use among homeless mentally ill youth, older adults, and veterans were excluded from this review because of the unique support needs and specialized services that are available for these populations (for a review, see Levinson and Ross 2007). Further, research that focused on homeless adults with substance abuse problems was excluded if participants did not have co-occurring mental illnesses. Inclusion criteria for journal articles were: peer-reviewed; published between 2000 and 2014; in English; and having either an entire sample of homeless adults with mental illness, or a discrete proportion of the sample that was analyzed on its own or in comparison to other participants.

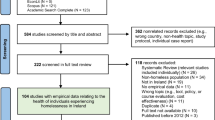

Searches were conducted in three databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and PubMed), using the following search terms: mental disorder*, mental health, mental illness*, psychiatr*, mentally ill, or mentally disordered; service*, support*, or program* followed by each combination of use, usage, utilization, utilisation, uptake, and provision; and homeless*, no fixed address, sleeping rough, rough sleeper*, rough sleeping, or street*. All searches were restricted to the abstract level. The results of these searches are shown in Fig. 1.

A considerable amount of the literature included in this review drew from larger research studies. The Access to Community Care and Effectiveness Services and Supports (ACCESS) demonstration project had the greatest representation, with a total of 12 publications emerging from that particular study (Gonzalez and Rosenheck 2002; Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2009, 2011; Lam and Rosenheck 2000; Lemming and Calsyn 2004, 2006; Min et al. 2004; Ortega and Rosenheck 2002; Rosenheck and Dennis 2001; Rosenheck et al. 2001, 2003; Rothbard et al. 2004). Similarly, Canadian research from the At Home/Chez Soi initiative (Currie et al. 2014; Patterson et al. 2012a, b; Stergiopoulos et al. 2014; Voronka et al. 2014) and a health survey of homelessness resources led by Bonin and colleagues (Bonin et al. 2007, 2009, 2010) were each the subjects of five and three publications, respectively. Finally, there was one case in which studies used different subsamples drawn from the same dataset (Gilmer et al. 2009, 2010; Lindamer et al. 2012). Other studies included in this review are: Acosta and Toro (2000), Forchuk et al. (2008), Gelberg et al. (2000), Herrman et al. (2004), Kuno et al. (2000), Lee et al. (2010), Linton and Shafer (2014), McLaughlin (2011), McNiel and Binder (2005), Nakonezny and Ojeda (2005), Odell and Commander (2000), Padgett et al. (2008), Pollio et al. (2000, 2003, 2006), Poulin et al. (2010), Rhoades et al. (2014), Stein et al. (2000), Tam et al. (2008), Unick et al. (2011), Wong et al. (2007, 2008), and Young et al. (2005).

In keeping with the review’s intent to identify the various definitions and methods used to study service use, publications from larger single studies or datasets were first analyzed together to determine whether single or multiple definitions, or measures of service use were used. This review included all unique definitions or methods, but omitted instances of duplication across publications (e.g., each of the unique definitions and methods of measuring service use from the 12 ACCESS publications are included in the review but duplications have been omitted). In this way, this review examines 27 studies described in 46 publications.

2.2 Data extraction and coding

Elements of service use that were extracted from each publication included: service domains (types of services studied), components of service use (quantification of service use; e.g., volume), assessment tools (measures and data sources used to assess service use), and period of service use assessment (length of time over which service use was assessed). In addition, to better understand how service use has been conceptualized and studied in the research, we adopted a formulation developed by Newman (2001) in her review of housing research wherein we examined whether service use was assessed as an input (i.e., predictor variable in the analytic design of the study), as an outcome (i.e., dependent variable), or as both an input and outcome. Finally, the assumptions and themes that underlie the service use research were also reviewed. Explicit assertions made by the authors about the current state of knowledge in the field and the significance of the topic, or the authors’ justifications for their study were extracted and thematically coded.

An initial coding scheme was developed by the lead author. Using the framework, two reviewers independently extracted and coded the data from the 46 publications. Inter-rater reliability was assessed through consensus estimates using percent-agreement and Cohen’s kappa coefficients. All percent-agreement statistics exceeded 80 % and kappas ranged from 0.65 to 1.00, indicating substantial to almost perfect agreement (Landis and Koch 1977). The two reviewers then discussed all discrepancies in their data extractions and revisions to the coding framework until a consensus was reached.

3 Results

3.1 Description of studies

Of the 27 studies included in this review, 21 (77.8 %) were conducted in the United States, three (11.1 %) in Canada, two (7.4 %) in Australia, and one (3.7 %) in the United Kingdom. Observational studies were the most common type of research, with 15 studies (55.6 %) employing a cross-sectional design and over one-third (n = 11; 40.7 %) a longitudinal one. Further, one study (3.7 %) had a case–control observational design. Experimental research was less prominent but still present: four studies (14.8 %) were quasi-experimental and one (3.7 %) was a randomized controlled trial. Percentages exceed 100 % as some studies involved multiple manuscripts with different study designs. Almost all studies used quantitative methods (n = 25; 92.6 %), whereas qualitative (n = 1; 3.7 %) and mixed methods approaches (n = 1; 3.7 %) were rare.

3.2 How service use is studied and measured

The vast majority of studies (85.2 %) investigated service use as an outcome variable, whereas four used it as an input (i.e., predictor variable; 14.8 %), and five as both inputs and outcomes (18.5 %). Table 1 details how service use has been measured and the periods of time over which it is assessed.

Two operationalizations of service use were most common: (1) receipt/non-receipt and (2) volume of service use. Receipt/non-receipt, examined in 23 of the studies (85.2 %), is a dichotomous measurement of service use that looks at whether or not participants have used a service or set of services over a certain period of time. Volume measurements, used in 12 studies (44.4 %), elaborate on dichotomous ones by measuring how much of a service is used based on a specific unit of measurement (e.g., visits to outpatient clinics, days spent in hospital). Because these two measurements can be used in a complementary manner, many of the reviewed studies used them concurrently. Costs of service use were a method of measurement in five studies (18.5 %).

Less common were more complex assessments of service use (see Table 1). Of these, timing of service use involved different types of measurements, such as the amount of time prior to service use (Min et al. 2004); day of the week that a service were used (Unick et al. 2011); and receipt of new services following discharge from other services to gauge continuity of care (Rothbard et al. 2004). Experience of service use involved a qualitative approach that sought to understand how specific positive and negative experiences with services affected satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Padgett et al. 2008), and perceived helpfulness or unhelpfulness (Voronka et al. 2014).

Probability and diversity of use were two methods of measurement used as part of the ACCESS project (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2009, 2011; Lemming and Calsyn 2004; Rosenheck and Dennis 2001; Rosenheck et al. 2001, 2003; Lam and Rosenheck 2000; Ortega and Rosenheck 2002). Probability refers to the likelihood of at least one visit being made to any service, whereas diversity focused on the number of different types of services that are used. Finally, volition was examined in one study by Unick et al. (2011) and refers to a dichotomous classification of voluntary or involuntary service use.

3.3 Types of services studied

The most common services examined were mental health services (n = 20; 74.1 %). Inpatient mental health services (n = 12; 44.4 %) were the most frequently studied, though ambulatory services, such as outpatient clinics (n = 6; 22.2 %) and case management (n = 5; 18.5 %) were are also common. A number of studies also examined mental health services that were general or unspecified (n = 7; 25.9 %), as well as composites of multiple services (n = 5; 18.5 %). Composite operationalizations are classifications of two or more services of a specific type that are collapsed into a single category (e.g., inpatient and outpatient mental health services being analyzed together as mental health services).

A trio of service domains, including general health services (mixed mental-medical health services and unspecified health services); treatment for substance use problems; and housing, homelessness, and basic needs services, were each investigated in twelve studies (44.4 %). Of the general health services that were examined, seven studies (25.9 %) focused specifically on use of emergency department and crisis services. With regard to services for housing, homelessness, and basic needs, slightly more studies looked at use of homeless shelter and related services (n = 8; 29.6 %) than assistance from housing agencies, including provision of housing (n = 6; 22.2 %). For the full listing of services studied, see Table 2.

3.4 Assumptions and theories of service use research

The assumptions and theories related to service use from each publication were identified and categorized. The most common assumption underlying the service use research was around the service needs of homeless people with mental illness. Assumptions of this type included: a range of housing and health services is needed to meet the needs of the population (Currie et al. 2014; Forchuk et al. 2008; Herrman et al. 2004; Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2009; Min et al. 2004; Tam et al. 2008), community-based services must be improved to successfully meet needs (Kuno et al. 2000), and people are not receiving the services that they need (Nakonezny and Ojeda 2005).

Service effectiveness was another domain in which assumptions were common. This consisted of general assertions that services were effective in helping people to live successfully and participate in the community (Acosta and Toro 2000; Herrman et al. 2004; Min et al. 2004; Wong et al. 2007), and greater use of services is associated with more positive outcomes (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2011; Pollio et al. 2000). Other assumptions that were made included: service system changes and failures have precipitated the current patterns of service use (Lemming and Calsyn 2006; Odell and Commander 2000; Stein et al. 2000), there is infrequent inclusion of service users and their perspectives in the research (Acosta and Toro 2000; Padgett et al. 2008; Voronka et al. 2014), use of services can facilitate access to other services (Herrman et al. 2004; Unick et al. 2011), and findings from service use research are valuable for service system improvement (McNiel and Binder 2005).

As for theories, the Gelberg-Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al. 2000) and variations of its predecessor, the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (Aday and Andersen 1974; Andersen 1968, 1995), were almost exclusively referenced in the literature. The behavioral models contend that service use can be predicted from predisposing, enabling, and need factors. One other theoretical model used by Bonin et al. (2007, 2009) was the Network-Episode Model (Pescosolido et al. 1998), which is concerned with social influences that affect if, when, and how individuals enter the health care service system in order to understand the dynamic processes of service use. In both theories, the objective is to successfully predict service use, with little or no emphasis on outcomes of service use.

4 Discussion

Service use among homeless people with mental illness has been primarily studied as an outcome variable using quantitative approaches that evaluate whether or not a particular service or set of services have been used within a certain period of time. The dichotomous assessment of service use limits what can be gleaned from findings as it is a crude measurement that provides the least information of the methodological approaches. However, this type of measurement was frequently used in combination with another approach, volume of service use—the second most employed method. Units of volume tended to concentrate on lengths of stay (e.g., at a hospital or homeless shelter), number of visits (e.g., to an outpatient clinic, emergency room, or food bank), and amount of time in receipt of services (e.g., seeing a case manager). As Goldman et al. (2000) noted, research with this approach views the service as a treatment and the volume as the dose. Such an approach, when the service use outcomes are positive, is able to make inferences about the level of service dosage that is sufficient for meeting people’s needs.

Costs of service use were the only other type of measurement that was found in more than one-in-ten studies. A focus of increasing attention in recent years due to the impact that the research can have with policymakers and funders, it was unexpected to see that only five studies examined service use with this lens. However, this may be partially explained by the siloed nature of mental health and homelessness services, and because most services serve additional populations beyond the scope of this review (i.e., homeless persons without mental illness or non-homeless persons with mental illness). As it may be important for costing research to include all clientele of a service in order to accurately conduct the cost-analysis, these studies would have been excluded as a result of the population that they focused on.

The methodological designs of reviewed studies were an area where there was some variability. Although randomized trials and quasi-experiments were rare, there were a number of studies that had longitudinal designs. This may be reflective of a growing trend in the field to use longitudinal research to understand how homelessness affects health behaviors over time (Biederman and Lindsey 2014). The feasibility of longitudinal research with this population may be greater now given that many studies are using administrative databases or organizational records to retrospectively assess service use. However, because the majority of the studies included in this review were from North America, it is unclear whether homelessness research in other parts of the world has also moved toward use of more longitudinal designs. As Busch-Geertsema et al. (2010) noted, in Europe, very few studies of homelessness were longitudinal at that time, which was due to differences in methodological approaches from those used in the United States. Nonetheless, longitudinal approaches to studying service use among homeless people with mental illness are a strength of the evidence base and one that future research should consider in order to produce a fuller and more accurate understanding of the complex subject.

There is a notable dearth of studies that have investigated service use as an input (i.e., predictor variable). Although much can be learned from studying service use as an outcome, the outcomes of service use, which are critically important to all stakeholder groups, are being less frequently examined. Specific to homeless populations with mental illness, there is an urgent need to understand the role of service use in the attainment of stable housing. Some of the reviewed studies that used service use variables as predictors did examine outcomes related to housing and homelessness (Gilmer et al. 2010; Gonzalez and Rosenheck 2002; Lemming and Caslyn 2006; Ortega and Rosenheck 2002; Patterson et al. 2012b; Rosenheck and Dennis 2001; Rosenheck et al. 2001, 2003; Wong et al. 2008) but a greater focus should be put on this relationship in future research. Further, personal outcomes of service use, such as recovery from mental illness, are not commonly studied. Broadly, recovery refers to overcoming the consequences and effects associated with mental illness, which may include having renewed hope, a redefined self, control over one’s life, a sense of empowerment, and opportunities for the exercise of citizenship (Anthony 1993; Davidson et al. 2005). With many mental health systems in high-income countries undergoing reforms to provide more recovery-oriented services (Kidd et al. 2014), the integration of recovery outcomes into service use research would represent a timely and valuable addition. Lastly, service use research would benefit from the employment of a critical view of services that examines the degree to which services are appropriate, are accommodating, and make a difference in the lives of the people who are using them.

Explicit assumptions and theories for guiding service use research were uncommon. Assumptions generally centered on services being needed by or effective for the population. Given that service use has been predominantly used as an outcome variable in the research, these positions contextualize why this may be the case. With the perspective that the services being researched are valuable and effective to the population using them, there is less necessity to examine outcomes of service users. However, because these services are not always identical to each other (e.g., due to differences by location and approach) and the population that accesses them is heterogeneous, the assumptions may be overstretching in studies that are not examining outcomes related to needs or effectiveness in some capacity.

As for theoretical models that were applied in the reviewed literature, the behavioral model of health service use, including the adapted framework for vulnerable populations, was almost exclusively used. The model, which posits that predisposing, enabling, and need factors predict service use, had historically treated service use as the end point. However, later iterations of the behavioral model recognize that service use is not the end of the process as outcomes of health behaviors, such as perceived health status, evaluated health status, and satisfaction, have been added (Andersen 1995). Integrating these outcomes more frequently into future research that employ the behavioral model would be advantageous to the field, as well as for further validating the health status and satisfaction elements that comprise the outcomes of the model.

Mental health services have been the most frequently examined type of service, with almost three-quarters of reviewed studies looking at this in some way. Within this domain, the majority focused on inpatient services. This is not unexpected as there are service planning and delivery implications to homeless persons using costly institutional services. However, the representation of psychiatric emergency and crisis services in the reviewed literature was one-third that of inpatient services. This may be explained by a number of studies that examined emergency and crisis services generally (i.e., not specific to mental illness) and, as a result, were categorized as general health services. Other commonly investigated mental health services were outpatient and consultation services and case management. Additionally, as was done across many service categories, in particularly the different domains of healthcare services, service composites were commonly used analytic variables. This approach yields information about total service use but obscures what can be ascertained from the use of individual services that comprise the composite category.

Other commonly studied services were housing, homelessness, and basic needs services, the primary foci of which were on temporary shelter services or housing support. The services that assisted with basic needs (e.g., soup kitchens, activities of daily living) were slightly less common. Further, only a handful of studies examined services related to employment, income support, transportation, and general social services, indicating that research has primarily been conducted with a narrow focus on services that attend to the most immediate needs of the population. This approach attends to services that may help get people off the streets and into homes but not to services that are beneficial for helping people to stay stably housed, or promote citizenship or recovery (e.g., income supports, vocational assistance, food security services; Kerman et al. 2013; Rowe 2015). Broadening the scope of services in future research to include services that are secondary yet essential to helping people with mental illness live successfully in the community would be valuable addition.

4.1 Present gaps and future research

Few studies have strayed from the study of service use with quantitative methods that focus on mental health, primary care, substance use treatment, homelessness, and housing services. As a result, there are gaps in the evidence base. First, even the research that has expanded beyond the core services has almost exclusively focused on formal services. Although access to formal health and social services are essential and warrant considerable research attention, they do not comprehensively cover the support services that persons with mental illness themselves have identified as important to their living in the community (Kerman et al. 2013). The most noticeable service omission is informal self-help and consumer-run groups and organizations, which have been researched at length with people who have serious mental illnesses but not the homeless population (Pistrang et al. 2010). Self-help groups offer mutual support through shared experience, and people’s own strengths and capacities for helping others (Trainor et al. 2004). The support from self-help groups along with assistance from formal health and social services, as well as social support from family and friends, helps people take charge of their lives and make progress toward recovery from mental illness. In addition to the absence of informal mental health consumer-run services, formal peer support (i.e., service provision that involves the inclusion of one or more persons with a history of mental illness; Davidson et al. 2006) was only examined in one of the reviewed studies (Voronka et al. 2014). Although peer support was offered within services in other studies (e.g., Min et al. 2004), it was rarely the focus on its own. Its omission in the reviewed literature may be reflective of a broader issue in the peer support research, which has shown that the service has positive impacts on empowerment, hope, and engagement in care for people with serious mental illnesses but is seldom studied with a homeless population (Chinman et al. 2014). Nevertheless, given that the role of peer specialists within mental health services for homeless people continues to grow (Hamilton et al. 2015), there is an opportunity for future research to address the omission of peer support in the service use literature. Lastly, future studies should consider looking at the extent to which these services are used, the outcomes from use of these services, and the use of these services in combination with other health and homelessness services.

The second gap in the evidence base is centered on people’s personal experiences of using services. This is largely the result of qualitative research on service use being underrepresented in the literature along with a fair amount of studies soliciting no input from service users whatsoever. There is a critical need to integrate the perspectives of service users into the research. Although this may not be feasible for some studies (e.g., retrospective research using administrative databases), others should consider opportunities for giving individuals who use services a voice. For quantitative studies, the inclusion of a short measure on satisfaction with services would be one option. Alternatively, devising an opportunity for participants to provide comments about their service use on a questionnaire or survey might help contextualize findings to better understand participants’ frames of reference with regard to their service use. A more intricate approach could involve qualitative interviews about participants’ use of services, which would yield a rich narrative to accompany any quantitative data being collected. However, it should also be noted that service use research represents one element of a larger body of literature on health and social services. In other support service research areas, qualitative research may be more common. For example, a recent review by Bright et al. (2015) of healthcare and rehabilitation engagement identified approximately a dozen qualitative studies, the majority of which were focused on populations with mental illness. Greater integration between this subfield of research and the one of service use would be another method of addressing the knowledge gaps that exist with regard to people’s experiences of using services. With stronger evidence being produced from longitudinal, quantitative studies, in-depth investigations into people’s experiences using services can act as a rich, complementary source of data that will provide researchers and other stakeholders with a more thorough understanding of service use among homeless people with mentally illness.

Lastly, few studies have been conducted outside of the United States—a finding consistent with previous observations by Salize et al. (2013). Given that service systems differ within and between countries, the evidence must be interpreted with caution, as findings may not generalize to other regions. For example, Canavan et al. (2012) detailed the high degree of variability that exists in services for the homeless mentally ill population in 14 capital cities across Europe. Future service use research would strongly benefit from the inclusion of descriptions of the service systems within which the research is being completed. Moreover, the disparity in where studies are being conducted also underscores the need for more service use research from countries outside of the United States.

There are several limitations to this review that must be noted. First, the search terms only captured research that explicitly examined service use. As a result, studies in which use was a secondary focus (e.g., as might be the case in studies of intervention efficacy and effectiveness) were not widely identified. However, the search parameters were necessary in order to keep the review manageable, as the literature that exists on services for homeless persons with mental illness is extensive. A second limitation is the scope of this review. Only three databases were searched and no hand searching of key journals was conducted. Although 46 manuscripts were identified, deemed appropriate, and included in this review, it is unlikely that the reviewed literature comprehensively covers the research on this topic. Nonetheless, we believe that the findings provide a clear representation of the approaches used to study service use, gaps in the evidence base, and avenues for future research.

5 Conclusion

The majority of the studies in this review had observational designs that measured service use quantitatively as an outcome using self-report methods, or administrative and organizational records. Receipt or non-receipt and volume of use were the most common methods of quantifying service use. The methods leave large gaps in the knowledge base related to understanding people’s experiences of using services, as well as the personal outcomes associated with the use. Mental health, primary care, substance use, homelessness, and housing services have been widely examined, whereas other less formal services, such as peer support, have been largely excluded in the service use research. As a result, there has been inequitable inattention paid to key services that are essential to people with mental illness’ recovery.

References

*denotes an article included in the review

*Acosta, O., Toro, P.A.: Let’s ask the homeless people themselves: a needs assessment based on a probability sample of adults. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 28, 343–366 (2000)

Aday, L.A., Andersen, R.: A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv. Res. 9, 208–220 (1974)

Andersen, R.M.: Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services (Research Series No. 25). Centre for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago, Chicago (1968)

Andersen, R.M.: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 36, 1–10 (1995)

Anthony, W.A.: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 16, 11–23 (1993)

Baggett, T.P., O’Connell, J.J., Singer, D.E., Rigotti, N.A.: The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am. J. Public Health (2010). doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.180109

Biederman, D.J., Lindsey, E.W.: Promising research and methodological approaches for health behavior research with homeless persons. J. Soc. Distress Homel. (2014). doi:10.1179/1573658x14y.0000000008

Bhui, K., Shanahan, L., Harding, G.: Homelessness and mental illness: A literature review and a qualitative study of perceptions of the adequacy of care. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. (2006). doi:10.1177/0020764006062096

*Bonin, J.-P., Fournier, L., Blais, R.: Predictors of mental health service utilization by people using resources for homeless people in Canada. Psychiatr. Serv. 58, 936–941 (2007)

*Bonin, J.-P., Fournier, L., Blais, R.: A typology of mentally disordered users of resources for homeless people: towards better planning of mental health services. Adm. Policy Ment. Health (2009). doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0206-2

*Bonin, J.-P., Fournier, L., Blais, R., Perreault, M., White, N.D.: Health and mental health care utilization by clients of resources for homeless persons in Quebec City and Montreal, Canada: a 5-year follow-up study. J. Behav. Health Ser. R. 37, 95–110 (2010)

Bright, F.A.S., Kayes, N.M., Worrall, L., McPherson, K.M.: A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. (2015). doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.933899

Busch-Geertsema, V., Edgar, W., O’Sullivan, E., Pleace, N.: Homelessness and homeless policies in Europe: lessons from research. Paper presented at the European Consensus Conference on Homelessness, Brussels, Belgium (2010, December)

Canavan, R., Barry, M.M., Matanov, A., Barros, H., Gabor, E., Greacen, T., Holcnerová, P., Kluge, U., Nicaise, P., Moskalewicz, J., Díaz-Olalla, J.M., Straßmayr, C., Schene, A.H., Soares, J.J.F., Gaddini, A., Priebe, S.: Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2012). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-222

Chinman, M., George, P., Dougherty, R.H., Daniels, A.S., Ghosa, S.S., Swift, A., Delphin-Rittmon, M.E.: Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr. Serv. 65, 429–441 (2014)

*Currie, L.B., Patterson, M.L., Moniruzzaman, A., McCandless, L.C., Somers, J.M.: Examining the relationship between health-related need and the receipt of care by participants experiencing homelessness and mental illness. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2014). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-404

Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Sells, D., Rowe, M.: Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophr. Bull. (2006). doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj043

Davidson, L., O’Connell, M.J., Tondora, J., Lawless, M., Evans, A.C.: Recovery in serious mental illness: a new wine or just a new bottle? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. (2005). doi:10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.480

Fazel, S., Khosla, V., Doll, H., Geddes, J.: The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. (2008). doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225

Folsom, D.P., Hawthorne, W., Lindamer, L., Gilmer, T., Bailey, A., Golshan, S., Garcia, P., Unützer, J., Hough, R., Jeste, D.V.: Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am. J. Psychiatry (2005). doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370

*Forchuk, C., Brown, S.A., Schofield, R., Jensen, E.: Perceptions of health and health service utilization among homeless and housed psychiatric consumer/survivors. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 15, 399–407 (2008)

*Gelberg, L., Andersen, R.M., Leake, B.D.: The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv. Res. 34, 1273–1302 (2000)

Geller, J.L.: The first step in health reform for those with serious mental illness: integrating the dis-integrated mental health system. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. (2015). doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000396

*Gilmer, T.P., Manning, W.G., Ettner, S.L.: A cost analysis of San Diego county’s REACH program for homeless persons. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 445–450 (2009)

*Gilmer, T.P., Stefancic, A., Ettner, S.L., Manning, W.G., Tsemberis, S.: Effect of full-service partnerships on homelessness, use and costs of mental health services, and quality of life among adults with serious mental illness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 645–652 (2010)

Goering, P.N., Streiner, D.L., Adair, C., Aubry, T., Barker, J., Distasio, J., Hwang, S.W., Komaroff, J., Latimer, E., Somers, J., Zabkiewicz, D.M.: The at home/chez soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a housing first intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open (2011). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323

Goldman, H.H., Thelander, S., Westrin, C.-G.: Organizing mental health services: an evidence-based approach. J. Ment. Health Policy 3, 69–75 (2000)

*Gonzalez, G., Rosenheck, R.A.: Outcomes and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatr. Serv. 53, 437–446 (2002)

Greenwood, R.M., Stefancic, A., Tsemberis, A., Busch-Geertsema, V.: Implementation of housing first in Europe: successes and challenges in maintaining model fidelity. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. (2013). doi:10.1080/15487768.2013.847764

Hamilton, A.B., Chinman, M., Cohen, A.N., Oberman, R.S., Young, A.S.: Implementation of consumer providers into mental health intensive case management teams. J. Behav. Health Ser. Res. (2015). doi:10.1007/s11414-013-9365-8

*Herrman, H., Evert, H., Harvey, C., Gureje, O., Pinzone, T., Gordon, I.: Disability and service use among homeless people living with psychotic disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 38, 965–974 (2004)

*Horvitz-Lennon, M., Frank, R.G., Thompson, W., Baik, S.H., Alegría, M., Rosenheck, R.A., Normand, S.-L.T.: Investigation of racial and ethnic disparities in service utilization among homeless adults with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 1032–1038 (2009)

*Horvitz-Lennon, M., Zhou, D., Normand, S.-L.T., Alegría, M., Thompson, W.K.: Racial and ethnic service use disparities among homeless adults with severe mental illnesses receiving ACT. Psychiatr. Serv. 62, 598–604 (2011)

Hwang, S.W., Aubry, T., Palepi, A., Farrell, S., Nisenbaum, R., Hubley, A.M., Klodawsky, F., Gogosis, E., Hay, E., Pidlubny, S., Dowbor, T., Chambers, C.: The health and housing in transition study: a longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. Int. J. Public Health. (2011). doi:10.1007/s00038-011-0283-3

Hwang, S.W., Tolomiczenko, G., Kouyoumdjian, F.G., Garner, R.E.: Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. (2005). doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.017

Kerman, N., Curwood, S.E., Sirohi, R., Trainor, J.: What’s in the basket of services? Support preferences of mental health consumers and family members. Can. J. Commun. Ment. Health (2013). doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2013-018

Kidd, S.A., McKenzie, K.J., Virdee, G.: Mental health reform at a systems level: widening the lens on recovery-oriented care. Can. J. Psychiatry 59, 243–249 (2014)

*Kuno, E., Rothbard, A.B., Averyt, J., Culhane, D.: Homelessness among persons with serious mental illness in an enhanced community-based mental health system. Psychiatr. Serv. 51, 1012–1016 (2000)

*Lam, J.A., Rosenheck, R.A.: Correlates of improvement in quality of life among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 51, 116–118 (2000)

Lamb, H.R., Bachrach, L.L.: Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr. Serv. 52, 1039–1045 (2001)

Landis, J.R., Koch, G.G.: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics (1977). doi:10.2307/2529310

*Lee, S., de Castella, A., Freidin, J., Kennedy, A., Kroschel, J., Humphrey, C., Kerr, R., Hollows, A., Wilkins, S., Kulkarni, J.: Mental health care on the streets: an integrated approach. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 44, 505–512 (2010)

*Lemming, M.R., Calsyn, R.J.: Utility of the behavioral model in predicting service utilization by individuals suffering from severe mental illness and homelessness. Community Ment. Health J. 40, 347–364 (2004)

*Lemming, M.R., Calsyn, R.J.: Ability of the behavioral model to predict utilization of five services by individuals suffering from severe mental illness and homelessness. J. Soc. Serv. Res. (2006). doi:10.1300/j079v32n03_09

Levinson, D., Ross, M.: Homelessness Handbook. Berkshire Publishing Group, Great Barrington (2007)

*Lindamer, L.A., Liu, L., Sommerfeld, D.H., Folsom, D.P., Hawthorne, W., Garcia, P., Aarons, G.A., Jeste, D.V.: Predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with high service use in a public mental health system. Adm. Policy Ment. Health (2012). doi:10.1007/s10488-011-0350-3

*Linton, K.F., Shafer, M.S.: Factors associated with the health service utilization of unsheltered, chronically homeless adults. Soc. Work Publ. Health (2014). doi:10.1080/19371918.2011.619934

Markowitz, F.E.: Psychiatric hospital capacity, homelessness, and crime and arrest rates. Criminology (2006). doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00042.x

*McLaughlin, T.C.: Using common themes: cost-effectiveness of permanent supported housing for people with mental illness. Res. Soc. Work Pract. (2011). doi:10.1177/1049731510387307

*McNiel, D.E., Binder, R.L.: Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatr. Serv. 56, 699–704 (2005)

*Min, S.-Y., Wong, Y.L.I., Rothbard, A.B.: Outcomes of shelter use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 55, 284–289 (2004)

*Nakonezny, P.A., Ojeda, M.: Health services utilization between older and younger homeless adults. Gerontologist 45, 249–254 (2005)

Newman, S.J.: Housing attributes and serious mental illness: implications for research and practice. Psychiatr. Serv. 52, 1309–1317 (2001)

*Odell, S.M., Commander, M.J.: Risk factors for homelessness among people with psychotic disorders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 35, 396–401 (2000)

*Ortega, A.N., Rosenheck, R.: Hispanic client-case manager matching: differences in outcomes and service use in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. (2002). doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000016257.61846.de

*Padgett, D.K., Henwood, B., Abrams, C., Davis, A.: Engagement and retention in services among formerly homeless adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse: voices from the margins. Psychiatr. Rehab. J. (2008). doi:10.2975/31.3.2008.226.233

*Patterson, M.L., Moniruzzaman, A., Frankish, C.J., Somers, J.M.: Missed opportunities: childhood learning disabilities as early indicators of risk among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. BMJ Open (2012a). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001586

*Patterson, M.L., Somers, J.M., Moniruzzaman, A.: Prolonged and persistent homelessness: multivariable analyses in a cohort experiencing current homelessness and mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. Ment. Health Subst. Use (2012b). doi:10.1080/17523281.2011.618143

Pescosolido, B.A., Gardner, C.B., Lubell, K.M.: How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and “muddling through” from “first-timers”. Soc. Sci. Med. 46, 275–286 (1998)

Pistrang, N., Barker, C., Humphreys, K.: The contributions of mutual help groups for mental health problems to psychological well-being: a systematic review. In: Brown, L.D., Wituk, S. (eds.) Mental Health Self-Help, pp. 61–85. Springer, New York (2010)

*Pollio, D.E., Spitznagel, E.L., North, C.S., Thompson, S., Foster, D.A.: Service use over time and achievement of stable housing in a mentally ill homeless population. Psychiatr. Serv. 51, 1536–1543 (2000)

*Pollio, D.E., North, C.S., Eyrich, K.M., Foster, D.A., Spitznagel, E.: Modeling service access in a homeless population. J. Psychoact. Drugs 35, 487–495 (2003)

*Pollio, D.E., North, C.S., Eyrich, K.M., Foster, D.A., Spitznagel, E.L.: A comparison of agency-based and self-report methods of measuring services across an urban environment by a drug-abusing homeless population. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. (2006). doi:10.1002/mpr.28

*Poulin, S.R., Maguire, M., Metraux, S., Culhane, D.P.: Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: population-based study. Psychiatr. Serv. 61, 1093–1098 (2010)

*Rhoades, H., Wenzel, S.L., Golinelli, D., Tucker, J.S., Kennedy, D.P., Ewing, B.: Predisposing, enabling and need correlates of mental health treatment utilization among homeless men. Community Ment. Health J. (2014). doi:10.1007/s10597-014-9718-7

*Rosenheck, R.A., Dennis, D.: Time-limited assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 1073–1080 (2001)

Rosenheck, R., Morrissey, J., Lam, J., Calloway, M., Stolar, M., Johnsen, M., Randolph, F., Blasinsky, M., Goldman, H.: Service delivery and community: social capital, service systems integration, and outcomes among homeless persons with severe mental illness. Health Serv. Res. 36, 691–710 (2001)

*Rosenheck, R.A., Resnick, S.G., Morrissey, J.P.: Closing service system gaps for homeless clients with a dual diagnosis: integrated teams and interagency cooperation. J. Ment. Health Policy 6, 77–87 (2003)

*Rothbard, A.B., Min, S.-Y., Kuno, E., Wong, Y.-L.I.: Long-term effectiveness of the ACCESS program in linking community mental health services to homeless persons with serious mental illness. J. Behav. Health Ser. Res. 31, 441–449 (2004)

Rowe, M.: Citizenship and Mental Health. Oxford University Press, New York (2015)

Rowe, M., Styron, T., David, D.H.: Mental health outreach to persons who are homeless: implications for practice from a statewide study. Community Mental Health J. (2016). doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9963-4

Salize, H.J., Werner, A., Jacke, C.O.: Service provision for mentally disordered homeless people. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. (2013). doi:10.1097/yco.0b013e328361e596

*Stein, J.A., Andersen, R.M., Koegel, P., Gelberg, L.: Predicting health services utilization among homeless adults: a prospective analysis. J. Health Care Poor U. 11, 212–230 (2000)

Stergiopoulos, V., Dewa, C., Durbin, J., Chau, N., Svoboda, T.: Assessing the mental health service needs of the homeless: a level-of-care approach. J. Health Care Poor Underserved (2010). doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0334

*Stergiopoulos, V., Gozdzik, A., O’Campo, P., Holtby, A.R., Jeyaratnam, J., Tsemberis, S.: Housing first: exploring participants’ early support needs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 167–182 (2014)

*Tam, T.W., Zlotnick, C., Bradley, K.: The link between homeless women’s mental health and service system use. Psychiatr. Serv. 59, 1004–1010 (2008)

Trainor, J., Pomeroy, E., Pape, B.: A Framework for Support, 3rd edn. Canadian Mental Health Association, Toronto (2004)

*Unick, G.J., Kessell, E., Woodard, E.K., Leary, M., Dilley, J.W., Shumway, M.: Factors affecting psychiatric inpatient hospitalization from a psychiatric emergency service. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry (2011). doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.06.004

*Voronka, J., Harris, D.W., Grant, J., Komaroff, J., Boyle, D., Kennedy, A.: Un/helpful help and its discontents: peer researchers paying attention to street life narratives to inform social work policy and practice. Soc. Work Ment. Health (2014). doi:10.1080/15332985.2013.875504

*Wong, Y.-L.I., Nath, S.B., Solomon, P.L.: Group and organizational involvement among persons with psychiatric disabilities in supported housing. J. Behav. Health Ser. Res. 34, 151–167 (2007)

*Wong, Y.-L.I., Poulin, S.R., Lee, S., Davis, M.R., Hadley, T.R.: Tracking residential outcomes of supported independent living programs for persons with serious mental illness. Eval. Program Plan. (2008). doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.07.001

*Young, A.S., Chinman, M.J., Cradock-O’Leary, J.A., Sullivan, G., Murata, D., Mintz, J., Koegel, P.: Characteristics of individuals with severe mental illness who use emergency services. Community Ment. Health J. (2005). doi:10.1007/s10597-005-2650-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kerman, N., Sylvestre, J. & Polillo, A. The study of service use among homeless persons with mental illness: a methodological review. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 16, 41–57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-016-0147-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-016-0147-7